Summary

Surgeons and their patients recognise that one of the major advances in surgical technique over the last 20 years has been the growth of minimal access surgery by means of laparoscopic and robotic approaches. Partnerships with industry have facilitated the development of advanced technical instruments, light sources, recording devices and optics which are almost out of date by the time they are introduced to surgical practice. However, lest we think that technological innovation is entirely a modern concept, we should remember that our predecessors were masters of their craft and able to apply new technologies to surgical practice. The history of minimal access surgery can be traced back to approximately 5000 years ago and this review aims to remind us of the achievements of historical doctors and engineers, as well as bring more modern developments to wider attention.

This review will comprise a three-part series:

Part I 3000BC to 1850 Early instruments for viewing body cavities

Part II 1850 to 1990 Technological developments

Part III 1990 to present Organisational issues and the rise of the robots

Keywords: Surgery, general surgery, history of medicine

This article is in our series on the history of minimal access surgery

Part I – 3000BC to 1850

Early instruments for viewing body cavities

Many ancient civilisations such as those in Egypt, Mesopotamia, Greece and Rome had well-developed medical practices and there are many references to surgery. The Sumerians, who were the antecedents of both the Babylonians and the Egyptians, developed small copper knives which are thought to have been used to perform surgery around 3000 BC. There is some evidence that they also used gold to make soft malleable catheters.1 Excavations in Egypt in 2001 unearthed a variety of bronze medical tools such as scalpels and needles from the tomb of Skar, a physician during Egypt’s Fifth Dynasty around 2400 BC.2

The Mesopotamian Empire, which existed from around 3100 BC to the fall of Babylon in 539 BC, has left us with numerous documents and artefacts that indicate that medicine and science were relatively advanced disciplines.3 Numerous medical instruments were described and remains have been discovered. The Hammurabi Code of Law (Figure 1) and the ancient Babylonian and Assyrian Medical (BAM) texts refer to hollow instruments used for inspection and treatment of bodily orifices.4,5 These tubes may be the first instances of ‘minimally invasive’ instruments. They were made of hollow reeds, lead, bronze or copper and used for instillation of eye drops and powders into the nose, ear or the urethra. The British Museum houses the Assyrian Medical Texts (AMT)6 which describe similar instruments and their medical uses. The Assyrian Dictionary of the University of Chicago Oriental Institute contains a wealth of information in this field.7

Figure 1.

Hammurabi Code of the Law. Inscribed on large black pillars, this ancient text contains one of the earliest law codes in the then-civilised world, along with documentation of art, history, science and literature.

Quotations from the descriptions of the procedures undertaken are included in the Assyrian Medical Texts,5 Babylonian and Assyrian Medical texts4 and the Assyrian Dictionary of the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago (CAD)6 texts and are given below–

mint and styrax through a copper tube into his eyes you will blow. BAM 510 col. II, 1. 25

you pour (the medication) into his left nostril by a zirlqu. CAD, 1961, vol. 21, p. 134 quotes the single, isolated text RA 15.76 rev. 1. 7

(by means of) a tube of copper, into his penis you shall blow (the medication) with your mouth AMT 58.6.6:

in pressed oil you will bray it, in a copper tube you will apply it into his penis BAM 111 col. II, 1. 25-26:

Another early reference to any form of minimal access instrument is in the Babylonian Talmud from 1300 BC. The use of a speculum is described.8,9 The Middle East was the cradle of civilisation and the most advanced in scientific and medical fields. In contrast, for religious and philosophical reasons, the ancient Japanese and Chinese societies, which also had well-established medical traditions around this time, did not hold with cutting into the human body and therefore there is a paucity of surgical or procedural references in their historical literature.

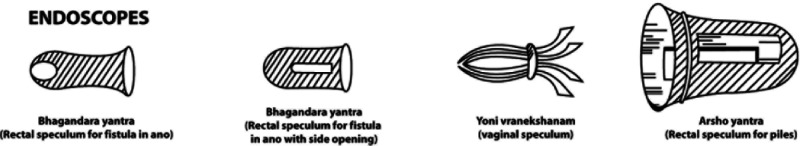

The Indian sage, surgeon and teacher Susruta, who lived somewhere between 800 and 600 BC wrote a compendium on surgery – Susruta Samhita.10 The term Samhita means ‘a collection of systematically arranged verses’. In this era before printing was available, the works of science, art or religion were composed in verse for easy memory. Susruta Samhita comprises six sections including military medicine, medical ethics, anatomical dissection and surgery. Two chapters of Susruta’s treatise describe 121 surgical instruments, many of which, although ancient, resemble those in modern-day surgical practice. He classified instruments as blunt (yantras) or sharp (sastras), the former including tubular instruments (Nadi yantras). Several types of early endoscopes are part of this group, including specula for inspecting the nose, mouth, ear, vagina and anus (Figure 2). These specula had a hole at one or both ends, or on the side. A throat speculum was described through which a foreign body could be removed. Susrata described a technique where a heated iron rod was inserted and placed on the foreign body which would melt and adhere to the tip of the probe and hence allow removal.

Figure 2.

‘Endoscopes’ taken from Susruta Smhita – Section I, chapters VII and VIII (diagram taken in part from Natarajan, 2008).10

Susruta also described various types of rectal specula, for the treatment of fistula in ano (Bhagandara yantra) or piles (Arsho yantra). The latter was described in great detail and could be made from iron, wood, horn or ivory. Different sizes were available for male and female patients. The two apertures allowed for not only inspection but also cautery or other treatment of the haemorrhoids.10–13

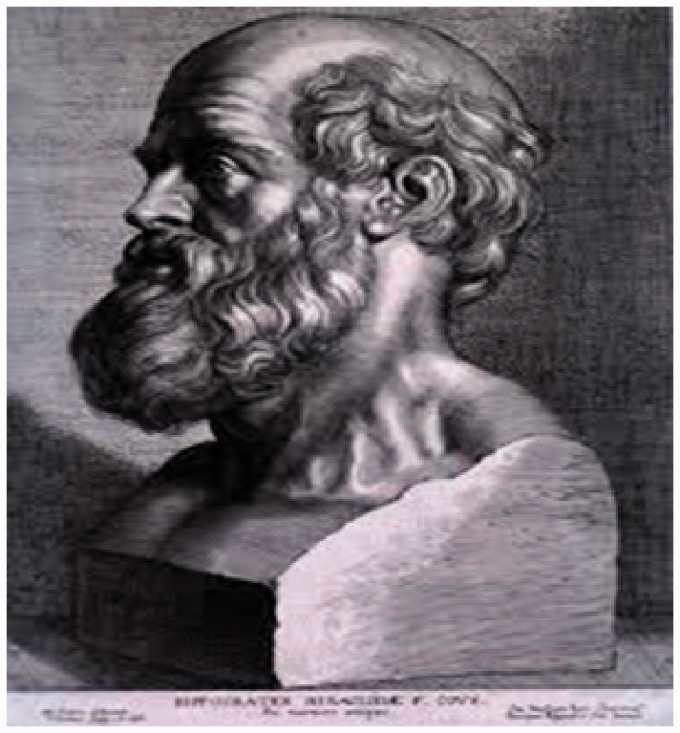

The name Hippocrates (Figure 3) is well known in relation to the Hippocratic Oath, which members of the public assume that all doctors swear upon graduation. Hippocrates and his colleagues may be regarded as some of the first surgeons as he stated – ‘οκόσα φάρμακα ου'κ ι'ται, ‘σίδηρος ι'ται….,’ meaning ‘What medicines do not heal, the lance will….’.14 However, the Hippocratic corpus, a group of physicians based in Kos around 460 BC, also recorded the use of minimally invasive technology. They used a variety of instruments such as a rectal speculum, various catheters and a hollow calabash (a type of gourd) to insert a vaginal ‘tampon’.15

Figure 3.

Hippocrates.

There are multiple other reports of early catheters used to inspect the urogenital tract. Many of these were rigid wooden or metal tubes but Erasistos (310–250 BC), who also practised in Kos, was the first to describe a curved S-shaped catheter for use in the urethra. It was known as the Kαθητɛρ – literally ‘to lower into’.1

At around the same time, Oreibasis (b. 325 BC), practising in Pergamon, was also developing various urethral catheters and undertook urethral dilatation using goose quill swathed in parchment.15

Instruments for inspection of and access to the lower bowel and the urogenital tract have been found in a number of ancient civilisations during the centuries around the dawn of the Christian era. The Syrian gynaecologist Archigenes practised in Rome in the first century BC and he described a cervical mirror for internal inspection.15 The city of Pompeii (Figure 4) was destroyed in 79 AD due to the eruption of Mount Vesuvius and excavations have yielded evidence of both rectal specula and vaginal mirrors made from wood or metal.

Figure 4.

Ruins of Pompeii.

In the Arab world, medicine and surgery also made progress during the first millennium AD. The most prominent surgeon of the Middle Ages, Abdul al-Qasim Khalaf ibn al-Abbas Al Zahrawi (936–1009), developed a glass mirror speculum that opened with screws16 – a feature which is still used in modern-day gynaecological specula. In the first millennium after the birth of Christ, minimally invasive surgery was limited to inspection close to bodily orifices such as the nostrils, vagina and rectum, due to the necessity for natural light to enter the cavity.

It was in the second millennium AD that an artificial light source was first used to enable examination of body cavities. The famous surgeon and anatomist, Guilio Cesare Aranzi (1530–1589), who described the foramen ovale, the ductus arteriosus and the hippocampus, developed an early endoscopic light source in 1587. In order to inspect the nasal cavity and remove polyps, a water-filled spherical bottle was used, along with a hole in a shutter to concentrate the light source.17 However, the procedure could only be performed in a darkened room and the original reports indicate that it was ‘to be used on rainy days’.

George Arnaud de Ronsil (1698–1774) was a French gynaecologist who was the first to use a covered lantern placed inside a silver painted box to focus light through a convex lens so that the vagina could be inspected with a speculum.18

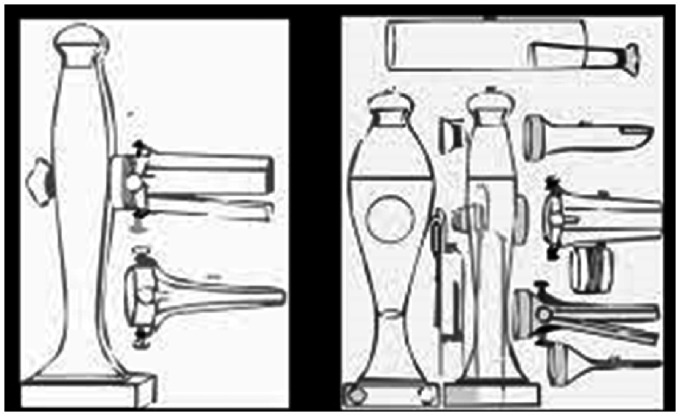

Phillipp Bozzini (1773–1809) made the most strategic step forward in lighting of endoscopes with his invention of Der Lichtleiter (the light conductor). This vase-shaped device was about 35 cm high and made from lead covered in leather. The chamber of the Lichtleiter was divided into two parts – a tube for light and a tube for image transport. On the light side, a candle was placed with concave mirrors behind it to reflect the light into the relevant body cavity – both human and animals. He also devised a series of different specula with screw fittings to enable the opening and inspection of different orifices such as the nose, throat or rectum. Initially, he published the description of these instruments in a local Frankfurt newspaper and subsequently published detailed reports of his lighting device in 1806 and 1807 (Figure 5).19,20 Further details about the mechanics of this instrument are given on the website of the European Museum of Urology (part of the European Association of Urology).21 Suffice it to say that the reflective lighting principles employed by Bozzini were the foundation for all developments in endoscopic urology for the next 70 years. Bozzini himself summarised the important features of his invention (Table 1). Although reflective light sources have been superseded by fibre-optic technology in recent decades, almost all of the other features in Bozzini’s monograph can be applied to modern-day endoscopy requirements. Unfortunately, professional jealousies and disputes were as common in Bozzini’s time as they are today, leading to his censure by the Medical Faculty of Vienna for ‘undue curiosity’. It was thought that the instrument would be dangerous to use and uncomfortable to introduce, and there is no record of its being used in clinical practice; however it formed the basis of urological endoscopy for the rest of the 19th century.

Figure 5.

Bozzini’s Der Lichtleiter (1806).

Table 1.

Bozzini’s criteria for Der Lichtleiter.

| The light conductor – Der Lichtleiter 19 | The light sheath | The light-conducting tubes 20 |

|---|---|---|

| The main requirements for looking into the internal cavities of the living body are therefore: I. To introduce a sufficient amount of light into these cavities. II. To bring the reflecting light-rays back to the eye of the examiner. To fulfil the first requirement you need a) a physiological or pathological orifice b) a light container c) light conducting tubes To fulfil the second requirement you need an additional tube for reflecting the light rays – which I call for the sake of distinction – reflecting tube. | One of the main requirements of the light is that the flame is kept with constant intensity at the same position. A wax candle which is stuck in a sheath made of iron or sheetbrass seems perfect to me … | Since these tubes bring the light into the cavities of the living body they should have the following properties: 1) They must be light enough to introduce them without any discomfort into the physiological or pathological orifices. 2) Since the cavities are mostly pressed together one would only see a small spot, if the shape of the tube should not be variable … 3) The different cavities of the living body require different tubes. The shape and size of the tube are subject to the individual cavity to be examined. 4) The tubes must give passage to the light and must permit excellent reflection of the light as well. 5) After being introduced into the cavities, the tubes must be fixed on the middle part of the light containers. In order to reach all these requirements. I have classified the tubes into three categories: 1) tubes for big cavities (e.g. vagina, uterus after delivery etc …) 2) tubes for small orifices, 3) tubes which permit the view to not straight (oblique) directions. |

A similar cystoscope, presented by Pierre Ségalas (1792–1874) to the Academy of Medical Sciences in 1826, was also ignored by the medical community. It was thought that his lighting system, using two candles, a conical mirror and a funnel of polished silver to reflect the light would not produce adequate illumination of the bladder.22 He called his invention the ‘speculum urethra-cystique’ and also included an eyeshield for the operator – very prescient in recognising endoscopy as an aerosol-generating procedure (AGP) in those pre-COVID-19 days.

The following year (1827), the American doctor John Fisher described a Z-shaped instrument made from hollow tubing in order to examine the vagina, bladder and urethra.23 He used the same lighting principle as Ségalas, but this instrument also failed to gain widespread acceptance.24 This was the first time that there was a record of an American contribution to the development of endoscopy. It appears that the prevailing moral climate in America at the time mitigated against intimate examinations of the urogenital tract. Fisher stated that he developed his instrument with the use of elongated tubing and Z-shaped hinges ‘In response to the need to examine the cervix of an unusually shy young woman who could not countenance him coming so close to her pudenda as was required by the standard vaginal speculum’. He wrote that he had a ‘strong and chivalrous desire to protect the feelings of delicacy of this maiden’.25

During this early part of the 19th century, there were several French urologists who were establishing this growing field of endo-urology. These included Paré, Frère Côme, Dionis, Mercier, Leroy D’Etiolles, Masionneuve, Cornay de Rochefort and Jean Civiale.26 D’Etiolles won a prize from the Parisian Medical Academy for his introduction of endoscopic transurethral lithotripsy in 1822, while de Rochefort introduced an early version of an aspirator to his endoscope, which prefigured the use of irrigation and aspiration systems in use today.

The most strategic contribution of this era was from Jean Civiale (1792–1867) who practised surgery and urology in Paris. In 1823, he reported a series of endoscopic transurethral lithotripsies building on D’Etiolles’ early developments. He also developed multiple innovations including a double-channelled irrigation system, a device for crushing bladder stones, modification of a wire basket and cutter, and a retractable scalpel for the treatment of urethral structures. His extensive clinical practice and influential position in Paris allowed him to disseminate these developments such that endoscopic urology began to be established (despite objections from parts of the surgical establishment) in France and further afield at this time.22

Although most of the running was made by urologists in the early part of the 19th century, the French otolaryngologist Jean Pierre Bonnafont presented his otoscope to the Parisian Medical Academy in 1834. Bonnafont’s ‘speculum autostatique’ was a bi-leaved otoscope to which he added a lens system based on that of a microscope, along with a conical mirror as described by Ségalas.25

The next big step forward was in November 1843 when Antonin Jean Desormeaux (1815–1894) made a presentation to the Académie Impériale de Médicine describing his invention of the first portable cystoscope incorporating Bozzini’s light source, for which he received the Argenteuil prize. He was the first to successfully perform diagnostic and simple therapeutic endoscopies (cauterisation of urethral strictures) of the urinary tract on living patients and it is thought that he coined the term ‘l’endoscopie’ in a presentation in Paris. He did a great deal of work modifying Bozzini’s lighting system of a lamp and mirrors and reflectors. The spirit lamp he used was fuelled by gasogene (a mixture of alcohol and turpentine) which unfortunately resulted in burns to the patients’ legs or the operators’ hands in early patients. He used the instrument in the urinary tract only, since urine was able to cool the heat from the lamp. His instrument was subsequently made on a commercial scale by the Parisian company Charrière and Luer. He wrote in meticulous detail about both the technical issues and his clinical cases, which helped to pave the way for the development of minimally invasive urology for the next 50 years.26,27

Around this time, John Avery in London was developing his form of cystoscope. He used a large headlight, known as a Palmer’s lamp (similar to a miner’s lamp) which was intended to direct and augment the candlelight (as per Segalas) into the instrument.28 He described its use in both the urethra and the larynx. However, his colleagues were not supportive and criticised the device as being ‘impractical and too thick in diameter’ and stated that ‘very little could be seen in the bladder’.

Conclusion

History shows us how doctors in ancient civilisations, both East and West, used the technology of their day to devise ways of examining numerous body cavities and undertaking simple therapeutic interventions. Over the last 500 years, European medical practitioners advanced the development of endoscopic instruments and light sources. Improvements in the quality of glass and mirrors allowed ingenious devices to be invented in order to view deeper recesses of the body. By 1850, many of the basic principles of minimal access surgery had been established and the scene was set for the rapid advancement of surgical technology which was to take place toward the end of the 19th and early 20th century. In Part II, we shall see how there was an exponential increase in the uses of minimal access surgery by the application of electric currents to provide better lighting, cautery and therapeutic procedures, in the following century.

Footnotes

Acknowledgement: The author would like to thank Dr Jane Lane for proof reading the manuscript.

Provenance: Not commissioned; peer-reviewed by David Webster.

ORCID iD: Rachel Hargest https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9830-3832

Declarations

Competing interests: None declared.

Funding: None declared.

Ethical approval: No ethical approval required.

Guarantor: RH.

Contributorship: Sole authorship.

References

- 1.Mattelaer JJ, Billiet I. Catheters and sounds: the history of bladder catheterisation. Paraplegia 1995; 33: 429–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sakkara Doctor Tomb Unearthed, www.jayepurplewolf.com/LEGENDS/sakkaradoctortomb.html, 2001.

- 3.Adamson P. Surgery in Ancient Mesopotamia. Med Hist 1991; 35: 428–435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Driver GR, Miles JC. Codex Hammurabi. Babylonian Laws 1955; Vol. 2Oxford: Clarendon Press. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kocher F. Die Babylonisch-Assyrische Medizin. Texten und Untersuchungen 1963–1980; Vol. 6Berlin: De Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thompson RC. Assyrian medical texts, London: Trustees of the British Museum, 1923. [Google Scholar]

- 7.CAD. The Assyrian dictionary of the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago, Chicago: Oriental Institute, 1956. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Babylonian Talmud. 1300 BC.

- 9.Bible and Talmud: sources of medical knowledge, www.jewishencyclopedia.com/articles/10544-medicine.

- 10.Natarajan K. Surgical instruments and endoscopes of Susruta, the sage surgeon of ancient India. Ind J Surg 2008; 70: 219–223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Singhal G, Singh L. Ancient Indian surgery based on Susrata Samhita 1981; Vols. I–XVaranasi (Banaras), India: Singhal Publications. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bhishagratna K. An english translation of Susruta-Samhita 1996; Vols. I–III5th ed Varanasi, India: Chowkhamba Sanskrit Series. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sharma PV. Susruta-Samhita 1999; Vols. I–III1st ed Varanasi, India: Chaukhambha Visvabharati. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hippocrates. Aphorisms. Section 7 No. 87, 400BC.

- 15.Schollmeyer T, Mettler L, Ruther D, Alkatout I. Practical manual for laparoscopic & hysteroscopic gynecological surgery, 2nd ed Delhi, India: Jaypee Brothers Medical Publishers Ltd, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Amr SS, Tbakhi A. Abu Al Qasim Al Zahrawi (Albucasis): pioneer of Modern Surgery. Ann Saudi Med 2007; 27: 220–221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guruluoglu R, Shafighi M, Gurunluoglu A, Cavdar S. Giulio Cesare Aranzio (Arantius) (1530-89) in the pageant of anatomy and surgery. J Med Biogr 2011; 19: 63–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.De Ronsil G. Memoires de chirurgie, avec quelques remarques historiques sur l’etat de la médicine et de la chirurgies en France et an Angleterre, Paris: Londres chez de Nourse, 1768. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bozzini P. Lichtleiter, eine Erfuindung zur Anshauung innerer Theile und Krankheiten nebst der Abbildung. J Pract Arzney Wunder 1806; 24: 107–124. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bozzini P. Der Lichtleiter oder die Beschreibungeiner einfachen Vorrichtung und Ihre Anwendung zur Erleuchtung innerer Höhlen und Zwuschenräume des lebenden animalischen Körpers. (The light guide or the account of a simple device to illuminate internal cavities and passages of living animals). Weimar: Verlag des Landes Industrie Comptoirs, 1807.

- 21.http://history.uroweb.org/instruments/early-endoscopes/lichtleiter/?no_cache=1.

- 22.Nezhat C. Neshat’s history of endoscopy. An analysis of endoscopy’s ascension since antiquity, Tuttingen, Germany: EndoPress, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fisher J. Instruments for illuminating dark cavities. Phil J Med Phys Sci 1827; i: 157–158. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Picatoste Y, Patino J, Martin GB, Hernández RR. Portillo Martín. Cystoscopy (1879–1979): centennial of a transcendental invention. Arch Esp Urol 1980; 33: 1–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sircus W. Milestones in the evolution of endoscopy: a short history. J R Col Phys Edin 2003; 33: 124–134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Desomeaux AJ. De l’endoscope et ses applications au diagnostic et au traitement des affections de l’urèthre et de la vessi. (Endoscopy and its applications in diagnosis and treatment of diseases of the urethra and bladder), Paris: JB Baillière, 1865. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Desomeaux AJ. The endoscope and its application to the diagnosis and treatment of affections of the genito-urinary passages. (Trans. RP Hunt) Chicago Med J 1867; 24: 177–194. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Noël JP, Goddard JC. The Introduction of the Cystoscope to the British Isles. J Urol 2014; 191: e625–626. [Google Scholar]