Abstract

Objective

To describe clinical, biological, radiological presentation and W4 status in COVID-19 elderly patients.

Patients and methods

All patients ≥ 70 years with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection and hospitalized in the Infectious Diseases department of the Pitié-Salpêtrière hospital, Paris, France, from March 1st to April 15th 2020 were included. The primary outcome was death four weeks after hospital admission. Data on demographics, clinical features, laboratory tests, CT-scan findings, therapeutic management and complications were collected.

Results

All in all, 100 patients were analyzed, including 49 patients ≥ 80 years. Seventy percent had ≥2 comorbidities. Respiratory features were often severe as 48% needed oxygen support upon admission. Twenty-eight out of 43 patients (65%) with a CT-scan had mild to severe parenchymal impairment, and 38/43 (88%) had bilateral impairment. Thirty-two patients presented respiratory distress requiring oxygen support ≥ 6 liters/minute. Twenty-four deaths occurred, including 21 during hospitalization in our unit, 2 among the 8 patients transferred to ICU, and one at home after discharge from hospital, leading to a global mortality rate of 24% at W4. Age, acute renal failure and respiratory distress were associated with mortality at W4.

Conclusion

A substantial proportion of elderly COVID-19 patients with several comorbidities and severe clinical features survived, a finding that could provide arguments against transferring the most fragile patients to ICU.

Keywords: Covid-19, Elderly patients, Sars-CoV-2, Prognostic factors, Computed tomography

1. Introduction

COVID-19 is an infection having to do with the novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 [1]. It started spreading from Wuhan, China in December 2019, leading to a major pandemic. By early September 2020, nearly 27 million COVID-19 cases were reported worldwide, associated with 900,000 deaths [2]. In France, almost 300,500 cases and 30,500 deaths have been documented since February 2020 [3]. Elderly population bear a heavy burden, with fatality rates reaching 26% and 58% in patients aged over 70 and 80 years, respectively. Most cohort studies have found age to be the main risk factor for mortality [4], [5], [6].

On May 12th in France, persons over 75 years of age represented 56% of inpatients, 71% of deaths having occurred during hospital stay, and only 19% of patients admitted in ICU [3]. Elderly COVID-19 patients consequently represent a high proportion of inpatients in medical wards. Despite frequent severe respiratory forms and accumulation of risk factors, a substantial number of these patients survive the infection. However, data in this population are very limited, especially among survivors after discharge from hospital.

Herein, we aimed to describe clinical, biological and radiological presentation of COVID-19 in patients over 70 years of age, in the Infectious and Tropical Diseases department of the Pitié-Salpêtrière University hospital (Paris, France), as well as clinical outcome 4 weeks (W4) after admission and the factors associated with mortality.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Study design and participants

We performed a retrospective, single-center study in the Infectious and Tropical Diseases department at the Pitié-Salpêtrière University Hospital, Paris, France. We included all confirmed cases of COVID-19 in patients over 70 years old admitted from March 1st to April 15th 2020. Patients were considered to have a confirmed infection if RT-PCR testing by nasopharyngeal swab and/or sputum came back positive.

2.2. Outcomes

The primary outcome was vital status (survival or death) 4 weeks after hospital admission. The secondary outcomes were length of hospital stay, occurrence of acute respiratory distress and/or other complications during clinical course, transfer to ICU, “do not resuscitate” order, use of hypnotic and opioid drugs, place of residence (at home or retirement home, subacute care ward, ICU) 4 weeks after hospital admission for survivors, and factors associated with vital status at week 4 (W4).

2.3. Procedures

We obtained data retrospectively from electronic medical records, which were carefully reviewed by three trained physicians. Patient data included demographics, home medications, comorbidities, initial signs and symptoms, onset of signs and symptoms, triage vital signs, initial laboratory tests, value of cycle threshold (Ct) for SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR, chest computed tomographic scan results, treatments received during hospitalization (antivirals, antibiotics, corticosteroids and oxygen support), maximum body temperature, and length of hospital stay. The Charlson index was used to evaluate patients’ medical state before admission [7]. The NEWS-2 score was used to standardize assessment of acute-illness severity at admission [8]. The occurrence of acute respiratory distress during clinical course was defined as the recourse to oxygen support ≥ 6 liters/minute to maintain blood oxygen saturation (SpO2) ≥ 94%. We also collected other significant complications (acute renal injury, acute hepatitis, bacterial infection) and maximum C-reactive protein (CRP) during hospital stay.

Nasopharyngeal swab and sputum samples were collected and tested by RT-PCR with the Cobas® SARS-CoV-2 kit (Roche), as recommended by the manufacturer, after neutralization with an equal amount of Cobas lysis buffer for SARS-CoV-2 (400/400 μL). Three categories of Ct were retained: Ct < 20 (high SARS-CoV-2 viral load), 20 < Ct ≤ 30 (mild viral load) and Ct > 30 (low viral load).

All scans were performed on a dedicated scanner (Siemens Somaton Edge) either without iodine injection or after IV of 60 mL iodinated contrast agent (Iomeprol 400 Mg I/mL, Bracco Imaging, Milan, IT) in cases of suspected pulmonary embolism. A radiologist (SB), who was blinded to clinical and biological features including RT-PCR results, reviewed all chest CT images on a PACS workstation (Carestream Health, Rochester, NY) and classified the chest CT as positive or negative for COVID-19 according to previously described CT features [9], [10], [11]. The radiologist also described the main CT features (ground-glass opacity, consolidation, reticulation/thickened interlobular septa, nodules, emphysema, pleural effusion), and lesion distribution (left, right or bilateral lungs). A semi-quantitative score was assigned (0% involvement; less than 25%; 25% to less than 50%; 50% to less than 75%; 75% or greater). All images were viewed on both lung and mediastinal settings.

For each patient we reported whether a transfer to ICU had been considered during clinical course, whether a “do not resuscitate” order had been collectively decided, and whether hypnotic or opioid drugs were used.

Patients or family were contacted by a physician four weeks after admission to collect vital status and place of residence at W4.

2.4. Statistics

We analyzed vital status 4 weeks after hospital admission using a logistic regression model. Factors investigated were: gender, age, place of residence before hospital admission, number of comorbidities, Charlson score, time from onset of symptoms and hospital admission, NEW-2 score, oxygen support need at admission, lymphocyte count at admission, SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR Ct, total lesion extension, presence of bilateral lesion, duration of hospital stay and respiratory distress (requiring oxygen support ≥ 6 liters/minute). For all these factors, missing values were defined as “unknown”. Descriptive analysis of the dependent and independent variables was performed. Univariate analysis was conducted, and all factors associated with death 4 weeks after hospital admission were entered into the multivariate model. We decided to exclude from the analysis the patients lost to follow-up. Vital status 4 weeks after hospital admission was compared between patients aged 70 to 79, 80 to 89 and > 90-year-old using a chi-square test. Survival curve was displayed using Kaplan-Meier estimates. All analyses were performed using R studio Version 1.2.5033 (© 2009-2019 RStudio, Inc.) and a P value < 0.05 was considered as significant.

2.5. Ethics

All discharged inpatients were included in the prospective COVID-PSL cohort, for the purposes of the 4-week telephone follow-up. They provided written informed consent. This cohort was approved by the Ile-De-France X Ethics Committee (n°47-2020, NCT04402905).

3. Results

3.1. Demographics and medical background

All in all, 100 patients were included for analysis, including 59 men (Table 1 ). Median age was 79 years (IQR 74-85). Fifty-one patients were between 70 and 79 years, 37 between 80 and 89 years, and 12 over 90 years old. Eighty-nine lived independently at home and 11 in retirement home before being admitted to hospital.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics at study entry (n = 100).

| Demographics | |

|---|---|

| Gender, n (%) | |

| Male | 59/100 (59) |

| Female | 41/100 (41) |

| Age, years, median (IQR) | 79 (74-85) |

| Age range, n (%) | |

| 70-79 years | 51/100 (51) |

| 80-89 years | 37/100 (37) |

| ≥ 90 years | 12/100 (12) |

| Place of residence before hospital admission, n (%) | |

| Home | 87/100 (87) |

| Retirement home | 13/100 (13) |

| Comorbidities | |

|---|---|

| Diabetes, n (%) | 24/100 (24) |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 56/100 (56) |

| Chronic heart failure, n (%) | 31/100 (31) |

| Cancer, n (%) | 21/100 (21) |

| Dementia, n (%) | 25/100 (25) |

| Auto-immune disorder, n (%) | 10/100 (10) |

| Immunosuppression (HIV or transplant), n (%) | 4/100 (4) |

| COPD or asthma, n (%) | 16/100 (16) |

| Chronic kidney disease, n (%) | 13/100 (13) |

| Obesity (BMI ≥30 kg/m2) | 6/100 (6) |

| Current smoking, n (%) | 6/100 (6) |

| Number of comorbidities, n (%) | |

| 0-1 | 29/100 (29) |

| 2-3 | 47/100 (47) |

| ≥ 4 | 24/100 (24) |

| Charlson score, n (%) | |

| 0-4 | 34/100 (34) |

| ≥5 | 66/100 (66) |

| Treatments | |

|---|---|

| ACE inhibitor, n (%) | 14/100 (14) |

| ARB treatment, n (%) | 9/100 (9) |

| Other antihypertensive treatment, n (%) | 57/100 (57) |

| Oral antidiabetic agent, n (%) | 13/100 (13) |

| Insulin, n (%) | 12/100 (12) |

| Corticosteroid, n (%) | 7/100 (7) |

| Immunosuppressive therapy, n (%) | 5/100 (5) |

| Statin, n (%) | 28/100 (28) |

| Anticoagulant, n (%) | 23/100 (23) |

| Antiplatelet agent, n (%) | 21/100 (21) |

| Proton pump inhibitor, n (%) | 29/100 (29) |

| Psychotropic treatment, n (%) | 36/100 (36) |

| Bronchodilator, n (%) | 12/100 (12) |

| Symptoms | |

|---|---|

| Fever, n (%) | 69/100 (69) |

| Cough and sputum, n (%) | 50/100 (50) |

| Chest tightness, difficulty breathing, n (%) | 36/100 (36) |

| Headache, n (%) | 8/100 (8) |

| Diarrhea, n (%) | 16/100 (16) |

| Loss of smell and/or taste, n (%) | 5/100 (5) |

| Confusion, n (%) | 14/100 (14) |

| Hospital admission | |

|---|---|

| Time from onset of symptoms, days, median (IQR) | 4 (2-7) |

| NEW-2 score, n (%) | |

| 0-2 | 45/100 (45) |

| ≥3 | 55/100 (55) |

| Oxygen support need, n (%) | |

| No | 52/100 (52) |

| 1-2 L/min | 26/100 (26) |

| ≥ 3 L/min | 22/100 (22) |

| Biological parameters | |

|---|---|

| Hemoglobin (g/L), median (IQR) | 12.5 (11.75-13) |

| Anemia, n (%) | 12/95 (13) |

| Platelets (x109/L), median (IQR) | 188 (151.5-245) |

| Thrombopenia, n (%) | 22/95 (23) |

| Total white blood cell count (x109/L), median (IQR) | 4.81 (2.63-6.50) |

| Lymphocyte count (x109/L), median (IQR) | 86 (60–122) |

| Lymphopenia, n (%) | 72/90 (80) |

| Neutrophil count (× 109/L), median (IQR) | 349 (205–496) |

| Serum ALAT (U/L), median (IQR) | 26 (20 -35) |

| Hepatic cytolysis, n (%) | 25/72 (35) |

| Serum creatinine (μmol/L), median (IQR) | 85 (71-106) |

| Acute renal failure, n (%) | 30/93 (32) |

| SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR | |

| Ct < 20 | 15/72 (21) |

| 20 <Ct ≤ 30 | 37/72 (51) |

| Ct > 30 | 20/72 (28) |

Fifty-six of them had a Charlson index ≥ 5 and 71 had at least 2 comorbidities (Table 1). The most prevalent comorbidities were high blood pressure (56%), chronic heart failure (31%), dementia (25%), diabetes (24%) and/or active cancer (21%). Eleven patients were undergoing long-term immunosuppressive and/or corticosteroid therapy.

3.2. Clinical and biological features at hospital admission

Median time between the onset of symptoms and hospital admission was 4 days (IQR 2-7). Seventy percent of patients were admitted to hospital before the 7th day.

All SARS-CoV-2 infections were confirmed by RT-PCR from nasopharyngeal swab and/or sputum, with low Ct (≤ 20) in 21% of cases and mild Ct (21-35) in 28% of cases.

The most prevalent symptoms reported at admission were fever (69%), cough (50%), dyspnea (36%), diarrhea (16%) and confusion (14%) (Table 1). Fifty-five patients had a NEWS-2 score ≥ 3 and 22% needed oxygen therapy ≥ 3 liters/minute upon admission.

Regarding biological parameters, 80% of patients had lymphopenia, 23% had thrombopenia, 32% had acute renal failure and 35% had hepatic cytolysis.

3.3. Thoracic CT-scan outcomes

Forty-six CT-scans were analyzed from 43 patients (3 patients had 2 CT-scans). Thirty-nine (91%) patients showed abnormal lung changes: 91% had ground class opacities (GGO), 63% had crazy paving (GGO associated with superimposed intralobular reticulations), and 30% had condensations. Twenty-nine patients (65%) had mild to severe parenchymal impairment, 38 (88%) had bilateral impairment, and the lesions were distributed mainly in the lower lungs in 35 patients (81%) (Table 2 ). Six patients had pleural effusion, and 11 patients suffered from common accompanying diseases including emphysema (n = 9), bronchiectasis (n = 1), and pleural sequelae (n = 1). Associated pulmonary oedema was detected in one patient. CT scan injections were administered in 42% of cases, with no pulmonary embolism detected.

Table 2.

Pulmonary CT-scan outcomes (n = 43).

| Normal CT | 4/43 (9) |

| Ground glass lesion extension, n (%) | |

| 0% | 4/43 (9) |

| 1-25% | 19/43 (45) |

| 26-50% | 16/43 (37) |

| 51-75% | 4/43 (9) |

| Crazy paving | 27/43 (63) |

| Condensation lesion extension, n (%) | |

| 0% | 30/43 (70) |

| 1-25% | 11/43 (25) |

| 26-50% | 2/43 (5) |

| 51-75% | 0/43 (0) |

| Total lesion extension, n (%) | |

| 0% | 4/43 (9) |

| 1-25% | 11/43 (26) |

| 26-50% | 21/43 (49) |

| 51-75% | 7/43 (16) |

| Bilateral lesion, n (%) | 38/43 (88) |

| Inferior lung involvement | 35/43 (81) |

| Pulmonary embolism, n (%) | 0/43 (0) |

3.4. Therapeutic management and clinical course during hospitalization

Sixty-five patients received antibiotics, including a beta-lactam in 97% of cases and/or a macrolide in 98% of cases (Table 3 ). Thirty percent of patients received hydroxychloroquine for a median duration of 9 days (IQR 2-10). No cardiac side effects were observed in patients treated by hydroxychloroquine. Seven percent of patients received short-term corticosteroid therapy (2-5 days).

Table 3.

Therapeutic management during hospitalization (n = 100).

| Antibiotics, n (%) | |

| Beta-lactam | 64/100 (64) |

| Macrolide | 12/100 (12) |

| Other | 1/100 (1) |

| Antiviral and/or immunomodulator treatments, n (%) | |

| Hydroxychloroquine | 29/100 (29) |

| Corticosteroid | 7/100 (7) |

| Azithromycin | 1/100 (1) |

| Tocilizumab | 1/100 (1) |

| Lopinavir/ritonavir | 1/100 (1) |

| Respiratory distress requiring oxygen support ≥ 6 liters/minute, n (%) | 32/100 (32) |

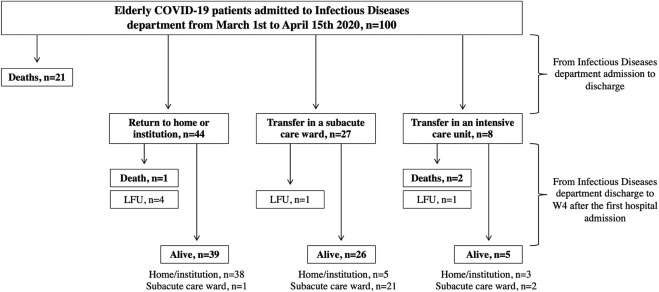

Thirty-two patients presented clinical deterioration with respiratory distress requiring oxygen support ≥ 6 liters/minute. Respiratory distress occurred after a median time of 10 days (IQR 4-13) after the onset of symptoms. Among these 32 patients, 8 (25%) were transferred to ICU (Fig. 1 ). All were <80 years. For the 24 others, a “do not resuscitate” order was decided on. Hypnotic and opioid drugs were used in 17 cases.

Fig. 1.

Study flow chart and W4 outcomes.

3.5. Mortality rate and place of residence at W4

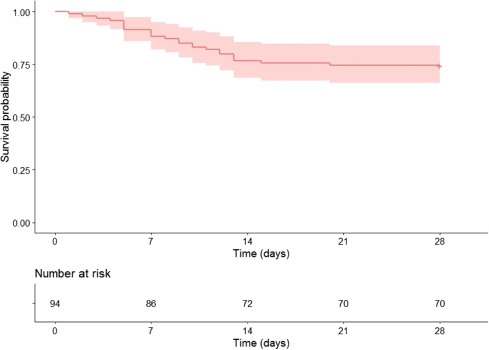

All in all, 24 deaths occurred from hospital admission to W4, including 21 deaths during hospitalization in our unit, 2 deaths in ICU and one death at home after discharge from hospital, leading to a global mortality rate of 24% at W4 (Fig. 2a). The mortality rate in 70-79, 80-89 and > 90 year-old patients was 10/47 (21%), 10/36 (28%) and 4/11 (36%), respectively. Duration of hospital stay was significantly shorter in deceased patients than in discharged patients (7.1 vs. 11.1 days, OR 0.70, 95%CI 0.47-0.88, P = 0.017). Among deceased patients, death occurred 9 days (IQR 13-16) in median after the onset of symptoms.

Fig. 2.

Survival curve of study patients.

All in all, among surviving patients, 46/67 (69%) had returned home or to their institution and 21/67 (31%) were still hospitalized in a subacute care ward.

3.6. Factors associated with death at W4

The older the patient's age, the greater the risk of dying (OR 1.15, 95%CI 1.05-1.27, P = 0.005); in other words, 10 more years equated to 15% more risk of dying due to COVID-19.

The occurrence of respiratory distress was also associated with death (OR 6.53, 95%CI 1.20-45.6, P = 0.038). Interestingly, 13 patients survived despite acute respiratory distress, without mechanical ventilation and after having received sustained oxygen support (6, 9 and 15 liters/minute for 4, 3 and 6 patients, respectively).

Aside from age and respiratory distress, only acute renal failure at admission was strongly associated with mortality at W4 (OR 73.8, 95%CI 5.7-3721.2, P = 0.006).

4. Discussion

In our study, patients aged ≥ 65 years with COVID-19 presented severe clinical course and frequently required respiratory support. The high mortality rate (24%) is consistent with similar findings in other countries such as China, Korea or the USA [12], [13], [14]. In a recent cohort study conducted in French acute care geriatric wards, the mortality rate was higher (31%), probably due to higher median age (86 vs. 79 years in our population) and poorer general health conditions (29% lived in an institution vs. 11% in our population) [15].

Although our population was characterized by a high frequency of severe comorbidities and included several very old patients (half of them were ≥ 80 years), 76% of patients survived during their hospital stay. Moreover, 70% of our patients received hospital admission prior to D7, i.e. before theorical deterioration of their clinical condition. This survival rate is all the more interesting insofar as some patients were temporarily in critical condition (n = 13), and a few were transferred to ICU (n = 8).

Viral pneumonia is one of the most frequent complications of COVID-19, requiring oxygen therapy and endotracheal intubation for the most severe forms [16]. Intensive care unit (ICU) stays are often extended for several weeks and burdened with high mortality rates, especially among older patients [17], [18] In many centers, access to ICU for patients over 70 years old is highly restricted, due to the poor prognosis [19]. In our study, no ICU transfer was decided for patients ≥ 80 years. More generally, up until now reported mortality rates in ICU in this population have ranged from 40 to 80%, although more robust data on short-and long-term outcomes are needed [17], [20]. In our establishment, oxygen support is performed by nasal canula, simple mask, or non-rebreathing mask. We were unable to use very high flow oxygen therapy (Optiflow system) or non-invasive ventilation, which could have represented alternatives to endo-tracheal intubation while enhancing survival.

In order to assess delayed mortality in elderly patients with COVID-19, we systematically contacted discharged patients or their families 4 weeks after their admission in our department. Prior to analysis, we expected non-negligible mortality at discharge due to sequalae of the disease and loss of autonomy, but in only one patient were we able to authenticate death after discharge, a finding seeming to suggest satisfactory recovery after the disease. However, and in spite of full pre-admission autonomy, a significant proportion of our patients were still hospitalized in subacute care wards, suggesting a slow return to health baseline. Moreover, we could not positively exclude the death of the 8 lost to follow-up patients.

As in previous cohorts, the most frequent symptoms associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection were fever, cough and dyspnea [17], [21]. However, isolated symptoms such as digestive disorders and confusion were not rare (16% and 14%, respectively, in our population), a finding highlighting the extent to which elderly patients are likely to require special attention [22].

Radiological presentations were consistent with clinical presentations, showing frequent signs of severe parenchymal impairment. Previous works have shown that pulmonary lesions are more extensive and more often bilateral in elderly patients than in younger patients [23], [24]. Surprisingly, no pulmonary embolism was detected, while venous thromboembolic disease may reach 20% during COVID-19 course in hospitalized patients [25]. The number of patients receiving an anticoagulant treatment before the infection (23%) could partially explain this result.

Antibiotics were widely used, and certainly over-used, due to inadequate knowledge at the onset of the pandemic outbreak. We treated patients using MERS-CoV-2 management as a model [26]. That said, no antibiotic side effects were reported (no allergic reactions, Clostridioides difficile colitis or catheter infections). On the other hand, almost half of the patients received hydroxychloroquine. While data (including ours) have recently shown a lack of positive impact of this antiparasitic on the SARS-CoV-2 infection [27], [28], they were not yet available at the time of our study. In any event, there was no significant difference in mortality in our population of elderly patients between those having received or not received hydroxychloroquine. Some patients were administered corticosteroids, according to the clinician's judgment, in case of aggravation and/or arguments suggesting inflammatory evolution of the disease. While the impact of corticosteroids on the COVID-19 course is currently under debate, recent data tend to corroborate their positive effect in COVID-19 management [29].

Several comorbidities (cardiovascular and lung diseases, diabetes, dementia or cancer), all of which increase with age, may have been present [30]. We investigated whether clinical and biological characteristics were associated with death. In our population, age and respiratory distress were significantly associated with mortality at W4, results that matched the prognostic factors found in other studies [6], [15], [31], [32]. Acute renal failure at hospital admission was likewise associated with mortality. Other works have observed renal impairment in some severe forms of COVID-19, and it may represent an independent factor associated with mortality [33], [34]. While several other factors such as severe initial clinical presentation (reflected by the NEWS-2 score) or biological abnormalities have been reported to be poor prognostic factors [6], [15], [31], [32], this was not the case in our population. We assume that the characteristics of our patient sample were too homogeneous to detect significant differences according to final outcome. Indeed, all patients were hospitalized in the same medical unit, almost all had a significant number of comorbidities as medical background, and almost all were suffering from severe SARS-CoV-2 infection.

This study has several limitations. First, it was a retrospective study with a relatively small number of patients and some unavailable biological data, limiting the field of our analysis with possible confounding factors. Second, our study subjects consisted of hospitalized patients; those deemed sufficiently fit for home isolation were not included, which could explain the high mortality and severity observed. Therefore, our results are not generalizable to mild cases. Finally, we did not use standardized geriatric scales (i.e. ADL, IALD) to accurately assess the overall progress of our elderly patients.

In conclusion, although they constitute the most vulnerable COVID-19 population, a high proportion of elderly patients with several comorbidities and severe respiratory feature survived the infection without mechanical ventilation. Given the extremely poor prognosis of elderly patients in ICU, our findings underline the need for medical departments to provide maximum and optimized care for this population.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human partic-pants were in accordance with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments.

Funding

This study was supported by internal funding.

Authors’ contributions

Conceptualization: RP, OI, NG, AB.

Formal analysis: NG, RP.

Investigation: RP, YW, OI, OP, SB, MLS, CS, NG, AB.

Methodology: RP, OI, NG, AB.

Supervision: RP, AB.

Validation: RP, OI, NG, AB.

Writing, original draft: RP.

Writing, review & editing: RP, OI, NG, AB, SB, CS.

Disclosure of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

Acknowledgments

PSL-Covid working group: Eric Caumes, Valérie Pourcher, Christine Katlama, Gentiane Monsel, Gianpierro Tebano, Alexandre Bleibtreu, Elise Klément, Roland Tubiana, Marc-Antoine Valantin, Luminita Schneider, Romain Palich, Antoine Fayçal, Baptiste Sellem, Olivier Paccoud, Sophie Seang, Oula Itani, Nagisa Godefroy, Agathe Nouchi, Basma Abdi, Cathia Soulie, Anne-Geneviève Marcelin, Vincent Calvez.

References

- 1.Li Q., Guan X., Wu P., Wang X., Zhou L., Tong Y., et al. Early Transmission Dynamics in Wuhan, China, of Novel Coronavirus-Infected Pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1199–1207. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization (WHO) 2020. COVID-19 weekly surveillance report, data for the week of 27 April-3 May 2020 [Internet] [cited 2020 May 18]. Available from: http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0008/442808/week18-covid19-surveillance-report-eng-.PDF?ua=1. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Santé Publique France . 2020. COVID-19 French national and regional weekly review [French] [Internet] [cited 2020 May 18]. Available from: https://www.santepubliquefrance.fr/content/download/252588/2603686. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dudley J.P., Lee N.T. Disparities in Age-Specific Morbidity and Mortality from SARS-CoV-2 in China and the Republic of Korea. Clin Infect Dis Off Publ Infect Dis Soc Am. 2020 doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leung C. Risk factors for predicting mortality in elderly patients with COVID-19: A review of clinical data in China. Mech Ageing Dev. 2020;188:111255. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2020.111255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zheng Z., Peng F., Xu B., Zhao J., Liu H., Peng J., et al. Risk factors of critical & mortal COVID-19 cases: A systematic literature review and meta-analysis. J Infect. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.04.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Charlson M.E., Pompei P., Ales K.L., MacKenzie C.R. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373–383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Royal College of Physicians . 2017. National Early Warning Score (NEWS) 2: Standardising the assessment of acute-illness severity in the NHS. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dai H., Zhang X., Xia J., Zhang T., Shang Y., Huang R., et al. High-resolution Chest CT Features and Clinical Characteristics of Patients Infected with COVID-19 in Jiangsu, China. Int J Infect Dis IJID Off Publ Int Soc Infect Dis. 2020;95:106–112. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sverzellati N., Milanese G., Milone F., Balbi M., Ledda R.E., Silva M. Integrated Radiologic Algorithm for COVID-19 Pandemic. J Thorac Imaging. 2020;35:228–233. doi: 10.1097/RTI.0000000000000516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pan F., Ye T., Sun P., Gui S., Liang B., Li L., et al. Time Course of Lung Changes at Chest CT during Recovery from Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Radiology. 2020;295:715–721. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020200370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang L., He W., Yu X., Hu D., Bao M., Liu H., et al. Coronavirus disease 2019 in elderly patients: Characteristics and prognostic factors based on 4-week follow-up. J Infect. 2020;80:639–645. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.03.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee J.Y., Kim H.A., Huh K., Hyun M., Rhee J.Y., Jang S., et al. Risk Factors for Mortality and Respiratory Support in Elderly Patients Hospitalized with COVID-19 in Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2020;35:e223. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2020.35.e223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.COVID-19 Response CDC Team Severe Outcomes Among Patients with Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) - United States, February 12-March 16, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:343–346. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6912e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zerah L., Baudouin É., Pépin M., Mary M., Krypciak S., Bianco C., et al. Clinical Characteristics and Outcomes of 821 Older Patients with SARS-Cov-2 Infection Admitted to Acute Care Geriatric Wards. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2020 doi: 10.1093/gerona/glaa210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen T., Wu D., Chen H., Yan W., Yang D., Chen G., et al. Clinical characteristics of 113 deceased patients with coronavirus disease 2019: retrospective study. BMJ. 2020;368 doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1091. [m1091] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grasselli G., Zangrillo A., Zanella A., Antonelli M., Cabrini L., Castelli A., et al. Baseline Characteristics and Outcomes of 1591 Patients Infected With SARS-CoV-2 Admitted to ICUs of the Lombardy Region, Italy. JAMA. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.5394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bhatraju P.K., Ghassemieh B.J., Nichols M., Kim R., Jerome K.R., Nalla A.K., et al. Covid-19 in Critically Ill Patients in the Seattle Region - Case Series. N Engl J Med. 2020 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2004500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Haas L.E.M., de Lange D.W., van Dijk D., van Delden J.J.M. Should we deny ICU admission to the elderly? Ethical considerations in times of COVID-19. Crit Care Lond Engl. 2020;24:321. doi: 10.1186/s13054-020-03050-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yang X., Yu Y., Xu J., Shu H., Xia J., Liu H., et al. Clinical course and outcomes of critically ill patients with SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a single-centered, retrospective, observational study. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8:475–481. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30079-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhou F., Yu T., Du R., Fan G., Liu Y., Liu Z., et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet Lond Engl. 2020;395:1054–1062. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lauretani F., Ravazzoni G., Roberti M.F., Longobucco Y., Adorni E., Grossi M., et al. Assessment and treatment of older individuals with COVID 19 multi-system disease: Clinical and ethical implications. Acta Bio-Medica Atenei Parm. 2020;91:150–168. doi: 10.23750/abm.v91i2.9629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang J., Zhu X., Xu Z., Yang G., Mao G., Jia Y., et al. Clinical and CT findings of COVID-19: differences among three age groups. BMC Infect Dis. 2020;20:434. doi: 10.1186/s12879-020-05154-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu K., Chen Y., Lin R., Han K. Clinical features of COVID-19 in elderly patients: A comparison with young and middle-aged patients. J Infect. 2020;80:e14–e18. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bompard F., Monnier H., Saab I., Tordjman M., Abdoul H., Fournier L., et al. Pulmonary embolism in patients with COVID-19 pneumonia. Eur Respir J. 2020:56. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01365-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bleibtreu A., Jaureguiberry S., Houhou N., Boutolleau D., Guillot H., Vallois D., et al. Clinical management of respiratory syndrome in patients hospitalized for suspected Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection in the Paris area from 2013 to 2016. BMC Infect Dis. 2018;18:331. doi: 10.1186/s12879-018-3223-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Geleris J., Sun Y., Platt J., Zucker J., Baldwin M., Hripcsak G., et al. Observational Study of Hydroxychloroquine in Hospitalized Patients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:2411–2418. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2012410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Paccoud O., Tubach F., Baptiste A., Bleibtreu A., Hajage D., Monsel G., et al. Compassionate use of hydroxychloroquine in clinical practice for patients with mild to severe Covid-19 in a French university hospital. Clin Infect Dis Off Publ Infect Dis Soc Am. 2020 doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rapid Evidence Appraisal for COVID-19 Therapies (REACT) Working Group WHO, Sterne J.A.C., Murthy S., Diaz J.V., Slutsky A.S., Villar J., et al. Association Between Administration of Systemic Corticosteroids and Mortality Among Critically Ill Patients With COVID-19: A Meta-analysis. JAMA. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.17023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guan W.-J., Liang W.-H., Zhao Y., Liang H.-R., Chen Z.-S., Li Y.-M., et al. Comorbidity and its impact on 1590 patients with COVID-19 in China: a nationwide analysis. Eur Respir J. 2020:55. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00547-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang J., Wang X., Jia X., Li J., Hu K., Chen G., et al. Risk factors for disease severity, unimprovement, and mortality in COVID-19 patients in Wuhan, China. Clin Microbiol Infect Off Publ Eur Soc Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2020;26:767–772. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2020.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Du R.-H., Liang L.-R., Yang C.-Q., Wang W., Cao T.-Z., Li M., et al. Predictors of mortality for patients with COVID-19 pneumonia caused by SARS-CoV-2: a prospective cohort study. Eur Respir J. 2020:55. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00524-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cheng Y., Luo R., Wang K., Zhang M., Wang Z., Dong L., et al. Kidney disease is associated with in-hospital death of patients with COVID-19. Kidney Int. 2020;97:829–838. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2020.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Martinez-Rojas M.A., Vega-Vega O., Bobadilla N.A. Is the kidney a target of SARS-CoV-2? Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2020;318:F1454–F1462. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00160.2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]