Previous studies have attested that the admission of a relative to an intensive care unit (ICU) is associated with increased stress for the patient's family [1]. Indeed, 70% of family members have been found to present with symptoms of anxiety, 35% with depressive symptoms and 33% with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) [2]. Consequently, specific guidance has been produced concerning family-centered care, which is a partnership approach to decision-making involving families and health-care providers [3].

In the context of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, France adopted a strict strategy of containment in the period 17th March to 11th May 2020. This aimed to limit the movement of people and social contact, leading to the ending of family visits in health-care settings, including ICUs. This approach was in conflict with the open visiting encouraged in the family-centered guidance referred to above. Contact between family members and ICU teams was also reduced significantly, limited to phone calls with just one relative nominated for this purpose.

In this context, the psychiatric and ICU teams at Toulouse University Hospital proposed a temporary approach known as OLAF (Opération de Liaison et d'Aide aux Familles). This approach was approved by an ethical board (CPP 2020–54). The goal was to offer family members: i) a psychiatric evaluation, ii) psychological support and, if required, iii) a referral for psychiatric care. The ICU team discussed this approach with relatives and advised that they would be contacted by the psychiatric team, which comprised eight psychiatry residents who volunteered their time. These members of the team were supervised by three senior psychiatrists in an on-call system and undertook two debriefing sessions per week. The psychiatric evaluation consisted in a psychiatric clinical assessment, the psychiatric diagnoses were established by referring on the DSM 5 criteria. The OLAF scheme was operational every day, from 10 am to 6.30 pm, between the end of March and the end of the containment period on 11th May.

During this time, 125 family members were referred to OLAF by the ICU team. A further 10 relatives who were told about the scheme by the other participants asked for psychological support without first being approached. During the initial contact with the psychiatric team, 68 families (50.4%) agreed to be evaluated. Of those that did not, their main motivation was a view that they did not need psychological support. The characteristics of the participants were as follows: 61 (90%) were female; the mean age was 54 (± 14.8); and 37 (54.4%) were married to or were the partner of the patient in the ICU, 18 (26.5%) were children, five (7.4%) were parents, five (7.4%) were siblings, and five (7.4%) had other family connections (e.g., cousin, ex-wife or ex-husband). The reasons for the ICU admissions were: SARS-CoV-2 for 40 (58.8%) patients; other pulmonary issues for six (8.8%); cardiac problems (endocarditis, heart attack) for four (5.9%); neurological causes for seven (10.3%); trauma for five (7.4%); and other issues for six (8.8%). Seventeen patients (25%) died in the ICU during the research period.

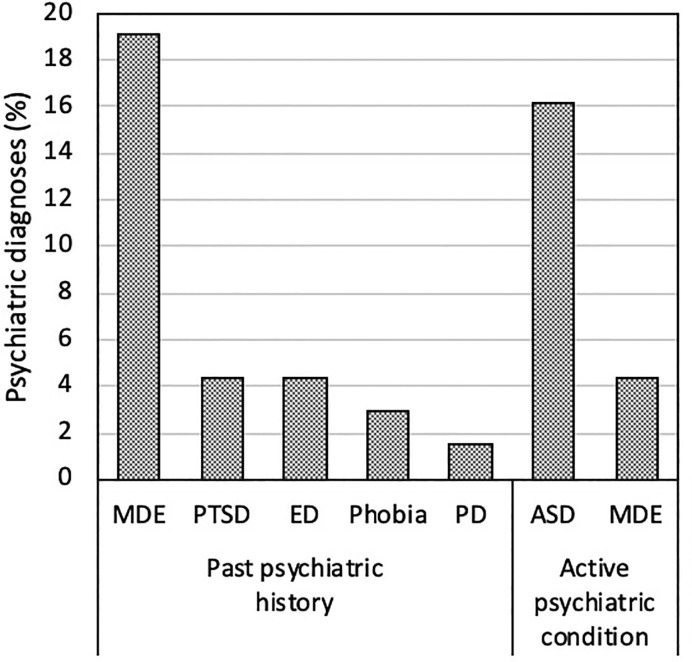

In relation to the participating family members, 13 (19.1%) had a medical history of depressive episodes, three (4.4%) of PTSD, three (4.4%) of an eating disorder, two (2.9%) of a phobia and one (1.5%) of a personality disorder. At the time of the evaluations, 14 (20.6%) family members presented with a psychiatric disorder, 11 (16.2%) with acute stress disorder and three (4.4%) with depression (Fig. 1 ). Of these 14 relatives, psychiatric follow up was organized for 12 of them: 11 (16.2 %) were referred for outpatient care and one for inpatient care due to a high level of suicide ideation. Nine (13.2%) family members were prescribed at least one psychotropic drug: Hydroxyzine (n=9), Oxazepam (n=1), Bromazepam (n=1) and Sertraline (n=1).

Fig. 1.

Repartition of the psychiatric disorders (past psychiatric history and current diagnoses) in the followed population. MDE: Major Depressive Episode, PTSD: Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder, ED: Eating Disorder, PD: Personality Disorder, ASD: Acute Stress Disorder.

In conclusion, the impact of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic on the family members of patients admitted to the ICU during the containment period under study is a matter of real concern. We found that 20.6% had an active psychiatric condition, and 16.2% had psychiatric symptoms requiring referral for ongoing care. Moreover 16.2% presenting with an acute stress disorder, this figure is both similar to those observed in a previous study of an ICU [4] and comparable with the prevalence of acute stress disorder observed following a road traffic accident or a physical assault [5]. Moreover, acute stress disorder is associated with a risk of PTSD. In conclusion, a lasting collaboration between psychiatric and ICU teams seems to be essential if psychiatric complications arising from ICU admissions due to the Covid-19 pandemic are to be avoided in the future.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Ali Alaoui, Alice Belloc, Charlotte Burdel, Lea Ferrer, Emmanuel Rau and Adeline Clenet for their contributions to this work.

References

- 1.Pochard F., Azoulay E., Chevret S., Lemaire F., Hubert P., Canoui P., et al. Symptoms of anxiety and depression in family members of intensive care unit patients: ethical hypothesis regarding decision-making capacity. Crit Care Med. 2001;29:1893–1897. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200110000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amass T.H., Villa G., OMahony S., Badger J.M., McFadden R., Walsh T., et al. Family care rituals in the ICU to reduce symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder in family members-a multicenter, multinational. Before After Interven Trial Crit Care Med. 2020;48:176–184. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000004113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Davidson J.E., Powers K., Hedayat K.M., Tieszen M., Kon A.A., Shepard E., et al. Clinical practice guidelines for support of the family in the patient-centered intensive care unit: American College of Critical Care Medicine Task Force 2004-2005. Crit Care Med. 2007;35:605–622. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000254067.14607.EB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beesley S.J., Hopkins R.O., Holt-Lunstad J., Wilson E.L., Butler J., Kuttler K.G., et al. Acute physiologic stress and subsequent anxiety among family members of ICU patients. Crit Care Med. 2018;46:229–235. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000002835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harvey A.G., Bryant R.A. Acute stress disorder across trauma populations. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1999;187:443–446. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199907000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]