Significance

A thrombin-fibrin pathway drives rapid and robust bacterial killing of Staphylococcus aureus following peritoneal infection. Elimination of coagulase activity results in S. aureus protection from antimicrobial activity and a corresponding reduction in host survival. These findings provide a molecular basis for the prevalence of coagulase negative staphylococci in peritonitis and highlight a caution when considering anticoagulant use in patients susceptible to peritoneal infection.

Keywords: fibrinogen, prothrombin, coagulase, host defense

Abstract

The blood-clotting protein fibrinogen has been implicated in host defense following Staphylococcus aureus infection, but precise mechanisms of host protection and pathogen clearance remain undefined. Peritonitis caused by staphylococci species is a complication for patients with cirrhosis, indwelling catheters, or undergoing peritoneal dialysis. Here, we sought to characterize possible mechanisms of fibrin(ogen)-mediated antimicrobial responses. Wild-type (WT) (Fib+) mice rapidly cleared S. aureus following intraperitoneal infection with elimination of ∼99% of an initial inoculum within 15 min. In contrast, fibrinogen-deficient (Fib–) mice failed to clear the microbe. The genotype-dependent disparity in early clearance resulted in a significant difference in host mortality whereby Fib+ mice uniformly survived whereas Fib– mice exhibited high mortality rates within 24 h. Fibrin(ogen)-mediated bacterial clearance was dependent on (pro)thrombin procoagulant function, supporting a suspected role for fibrin polymerization in this mechanism. Unexpectedly, the primary host initiator of coagulation, tissue factor, was found to be dispensable for this antimicrobial activity. Rather, the bacteria-derived prothrombin activator vWbp was identified as the source of the thrombin-generating potential underlying fibrin(ogen)-dependent bacterial clearance. Mice failed to eliminate S. aureus deficient in vWbp, but clearance of these same microbes in WT mice was restored if active thrombin was administered to the peritoneal cavity. These studies establish that the thrombin/fibrinogen axis is fundamental to host antimicrobial defense, offer a possible explanation for the clinical observation that coagulase-negative staphylococci are a highly prominent infectious agent in peritonitis, and suggest caution against anticoagulants in individuals susceptible to peritoneal infections.

In addition to serving as a centerpiece of hemostasis and thrombosis, fibrin(ogen) directs local inflammation in areas of tissue damage. Fibrin(ogen) can engage an array of integrin and nonintegrin cell-surface receptors to mediate downstream effector functions of innate immune cells. Whereas fibrin(ogen)-driven inflammation is detrimental in the context of inflammatory diseases like arthritis, colitis, and musculoskeletal disease (1–4), it is an important component of host defense in the context of infection (5–8). To help counter host defense mechanisms, bacteria have evolved virulence factors that engage host hemostatic system components to manipulate the activity of coagulation and fibrinolytic factors. This is particularly true for staphylococcal species, including the common, highly virulent human pathogen Staphylococcus aureus.

S. aureus is a Gram-positive pathogen that expresses numerous virulence factors that engage the hemostatic system within vertebrate hosts, including an array of products that directly bind fibrin(ogen) and control fibrin deposition (9–13). S. aureus produces two nonproteolytic prothrombin activators, collectively termed “coagulases,” that bind host prothrombin and mediate fibrin formation (14, 15). Pathogen-mediated fibrin(ogen) binding and fibrin formation have been linked to S. aureus functioning as a causative agent underlying a spectrum of diseases ranging from skin infections to life-threatening pneumonia, bacteremia/sepsis, and endocarditis. A possible exception may be peritonitis. Peritoneal infection is particularly problematic for cirrhotic patients, and in hospital-acquired infections is associated with sutures, catheters, and medical implants. Intriguingly, it is coagulase-negative staphylococci (CoNS) that account for the overwhelming majority of these infections (16–20). The basis for the high prevalence of CoNS rather than the more pathogenic coagulase-positive S. aureus, and whether there is a functional link to bacterial-driven prothrombin activation, remains undefined. Here, we explored the hypothesis that host fibrinogen and prothrombin drive a bacterial killing mechanism and defined the contribution of bacterial coagulases to infection in a murine model of acute S. aureus peritonitis.

Results

Host Fibrinogen Is Critical for the Rapid Clearance of S. aureus in the Peritoneal and Pleural Cavities.

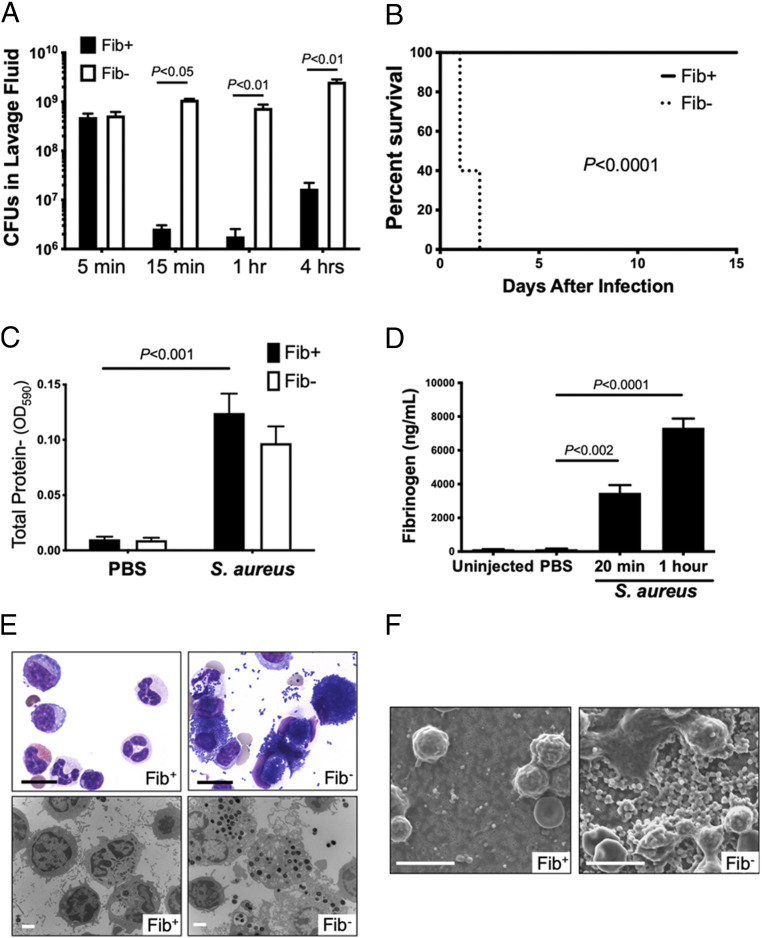

To define the importance of fibrinogen in the host antimicrobial response, control (Fib+) and fibrinogen-deficient (Fib–) mice were challenged with an intraperitoneal (i.p.) infection of 109 colony-forming units (CFUs) of S. aureus, strain Newman. Fib+ mice exhibited extremely rapid and efficient bacterial clearance, with less than 1% of the input bacterial CFUs observed in the peritoneal lavage fluid within 15 min and with CFU values remaining very low thereafter (Fig. 1A). In contrast, CFUs in the peritoneal lavage fluid from Fib– mice remained similar to that of the initial inoculum over the 4-h observation period. The early failure in bacterial clearance in Fib– mice translated to a significant difference in survival profile relative to Fib+ mice in which all Fib– mice died within 24 h of S. aureus infection whereas none of the challenged Fib+ mice succumbed to the infection even after 2 wk (Fig. 1B). Necropsy of Fib– mice did not reveal any appreciable hemorrhage in the peritoneal cavity or other organs, implying that the cause of death was not a consequence of bleeding due to lack of the clotting function. Rather, microscopic analyses of the major organ systems 18 h after i.p. infection revealed massive dilation of both the right and left heart ventricles and microbes within the microvasculature of the liver, kidney, spleen, lung, and other tissues in Fib– mice, but not in Fib+ mice. Collectively, these observations suggest cardiovascular failure from septic shock as the cause of death for Fib– mice. In contrast, none of these pathologies were observed in Fib+ mice challenged in parallel.

Fig. 1.

Fibrinogen promotes S. aureus clearance in a model of acute peritonitis. (A) Total live bacteria in the peritoneal lavage fluid of Fib+ and Fib− mice (n = 4 to 5 per group) at various time points following i.p. inoculation of 109 CFUs of WT S. aureus. Values are mean +/− SEM by Mann–Whitney U test analysis. (B) Kaplan–Meier analysis of Fib+ or Fib– mice (n = 10 mice per group) after i.p. infection of 6 × 108 CFUs of WT S. aureus reveals a significant survival benefit for Fib+ mice compared to Fib– mice. (C) Mice (n = 4 mice per group) were given an intravenous injection of Evans Blue dye prior to peritoneal challenge with PBS or 1 × 109 CFUs of S. aureus. Lavage fluid was collected 1 h after infection and assayed spectrophotometrically for Evans Blue accumulation. (D) Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay analysis for fibrinogen in lavage fluid of mice either uninjected (n = 3) or challenged i.p. with PBS (n = 3) or 1 × 109 CFUs of S. aureus (n = 4 per time point). (E) Lavage fluid harvested 1 h after infection of Fib+ and Fib− mice with 1 × 109 CFUs of WT S. aureus. (Upper) Representative microscopic views of stained cytospin preparations from lavage fluid of Fib+ and Fib− mice 1 h after infection. Note the relatively clear fields in control mice compared to extensive bacteria both free and cell-associated in the Fib− mice. (Scale bar, 10 μm.) (Lower) Representative transmission electron microscopic views of peritoneal lavage fluid components. (Scale bar, 2 μm.) (F) Representative scanning electron microscopic views of 0.22-μm filters following passage of total peritoneal lavage fluid from Fib+ and Fib− mice 1 h following infection with 109 CFUs of WT S. aureus. (Scale bar, 10 μm.) CFU data are presented as mean ± SEM and analyzed by Mann−Whitney U test.

An Evans Blue dye assay readily detected similar levels of plasma components in lavage fluid of Fib+ and Fib– mice challenged with S. aureus but not phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (Fig. 1C). This finding suggested S. aureus-driven inflammation induces significant vascular leak into the peritoneal cavity. Notably, fibrinogen was also specifically identified in peritoneal lavage fluid of wild-type (WT) mice challenged with S. aureus, but not unchallenged animals or animals challenged with PBS (Fig. 1D).

Examination of cytospin preparations of lavage fluid from infected Fib+ mice revealed resident leukocytes with few, if any, free bacteria, whereas lavage fluid from Fib– mice was predominantly characterized by phagocytes engorged with bacteria and substantial free bacteria in the fluid (Fig. 1E). Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) confirmed that peritoneal cavity cells from Fib– animals contained phagocytosed, intact bacteria whereas peritoneal cavity cells from Fib+ animals were largely free of intact bacteria (Fig. 1E). To confirm that the fraction of lavage fluid analyzed on cytospin was representative of the whole, lavage fluids retrieved from infected Fib+ and Fib– mice were passed through 0.2-μm filters (a pore size five times smaller than the diameter of S. aureus), and retained components were visualized by scanning electron microscopy (SEM) (Fig. 1F). Consistent with other results, few free particles the size of intact bacteria were observed in any form, single or aggregated, in lavage fluids from Fib+ mice, but large numbers of bacteria were apparent in Fib– mice.

The fibrinogen-dependent clearance of S. aureus was not unique to the peritoneal cavity. At both 20 min and 1 h following pleural cavity infection, CFUs in pleural lavage fluid were ∼100- to 200-fold less than the original inoculum in Fib+ mice, whereas CFUs remained close to input values in Fib– animals challenged in parallel (SI Appendix, Fig. S1A). Microscopic evaluation of pleural lavage fluid cytospin preparations from infected Fib+ animals was largely free of bacteria, whereas cytospins from pleural lavage of infected Fib– mice exhibited extensive free- and phagocyte-internalized microbes (SI Appendix, Fig. S1B). Notably, as observed with peritoneal infection, phagocytes in pleural lavage fluids from Fib– mice were often heavily engorged with bacteria, indicating that the failure of bacterial clearance was not associated with any fundamental failure of phagocytosis; rather, leukocyte phagocytosis appeared to be a default mechanism of bacterial control in the absence of a more expeditious fibrin(ogen)-dependent bacterial elimination.

Fibrin(ogen)-Dependent Clearance of S. aureus in the Peritoneal Cavity Is Associated with a Reduction in Viable Microbes.

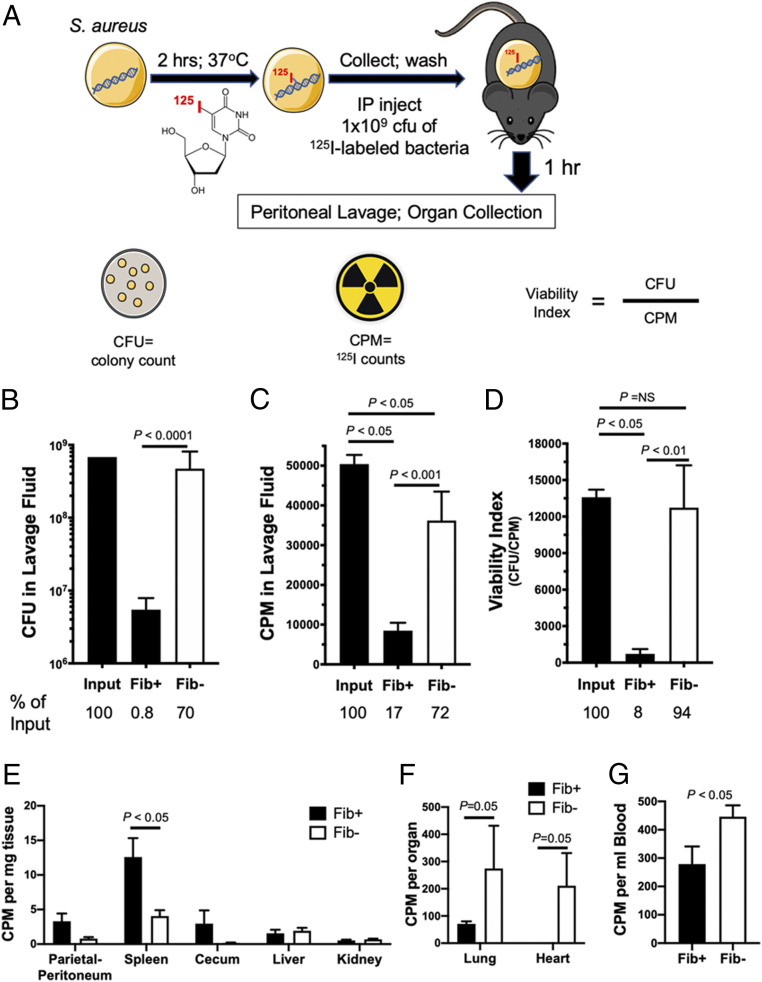

To determine whether the loss of detectable CFUs in Fib+ mice following i.p. S. aureus infection was due to a requirement of fibrinogen for bacterial killing, S. aureus fate studies were performed. Here, S. aureus was cultured with [125I]-iododeoxyuridine under conditions where >99% of the bacteria-associated radioisotope was incorporated into the bacterial genome (Fig. 2A). CFUs in lavage fluid retrieved from Fib– mice 1 h following i.p. infection with [125I]-labeled S. aureus were close to the CFUs originally injected, whereas CFUs retrieved from Fib+ mice were significantly reduced by approximately two-orders-of-magnitude (Fig. 2B; P < 0.0001). The radiolabel, measured in counts per minute (CPM), provided a means to assess the retrieval efficiency of the inoculum material. Unlike CFUs where only 0.8% of initial inoculum was recovered, ∼17% of the initial radiolabel was retrievable from Fib+ mice (Fig. 2 B and C). In contrast, in Fib– mice, 70% of the original inoculum was retrievable as CFUs and was comparable to a 72% recovery of the radiolabel (Fig. 2 B and C). Consistent with the exceptionally high residual CFUs observed in Fib– hosts, the viability index (expressed as CFU/CPM) of bacteria retrieved from Fib– mice 1 h after injection was 94% of the value of the initial inoculum (Fig. 2D), a difference that was not statistically significant. In contrast, the viability index of bacteria retrieved from Fib+ mice at 1 h was reduced to just 8% of the initial inoculum (Fig. 2D; P < 0.05). Thus, the reduction in CFUs in Fib+ mice, but not in Fib– mice, is linked to a rapid reduction in bacterial viability in the peritoneal cavity of fibrin(ogen)-sufficient hosts.

Fig. 2.

Fibrinogen promotes rapid bacterial killing of S. aureus in the peritoneal cavity. (A) Model of experimental approach using S. aureus radiolabeled with 125I-iododeoxyuridine. A cohort of Fib+ (n = 6) and Fib− (n = 5) mice were administered an i.p. injection with 1 × 109 CFUs 125I-labeled of S. aureus. Determination of (B) viable bacteria and (C) total radiolabeled material (i.e., CPM) within peritoneal lavage fluid harvested from Fib+ and Fib− 1 h after infection. (D) A viability index was determined for the challenge inoculum as well as for lavage fluid from Fib+ and Fib− mice harvested 1 h after infection. The number of live bacteria relative to the total radiolabel within the samples was expressed as CFU/CPM. (E) Determination of 125I activity associated with the parietal peritoneum and whole organs of the peritoneal cavity from Fib+ and Fib− mice 1 h after infection with 1 × 109 CFUs of 125I-radiolabeled S. aureus. Determination of 125I activity associated with (F) whole lungs and hearts and (G) whole blood of mice infected with 1 × 109 CFUs of 125I-labeled S. aureus 1 h after infection. CFU and CPM data are presented as mean ± SEM and analyzed by Mann−Whitney U test.

The radioisotope tag was also a means of determining the fate of material that was not retrievable in the peritoneal lavage. Measurement of residual radiolabel of abdominal organs indicated a trend in higher CPM for the parietal peritoneum and cecum and significantly higher CPM in the spleen of Fib+ relative to Fib– mice. This finding is consistent with the hypothesis that in Fib+, but not in Fib–, mice microbes were preferentially eliminated and bacterial remnants (i.e., S. aureus genomic DNA fragments) were associated with peritoneal surfaces or transported to the spleen via phagocytes for antigen processing. Analysis of heart, lung, and blood revealed significantly higher CPM values in Fib– relative to Fib+ mice (Fig. 2 F and G). These findings are consistent with the concept that viable microbes are able to avoid elimination in the peritoneal cavity of Fib–mice and disseminate to distant organs.

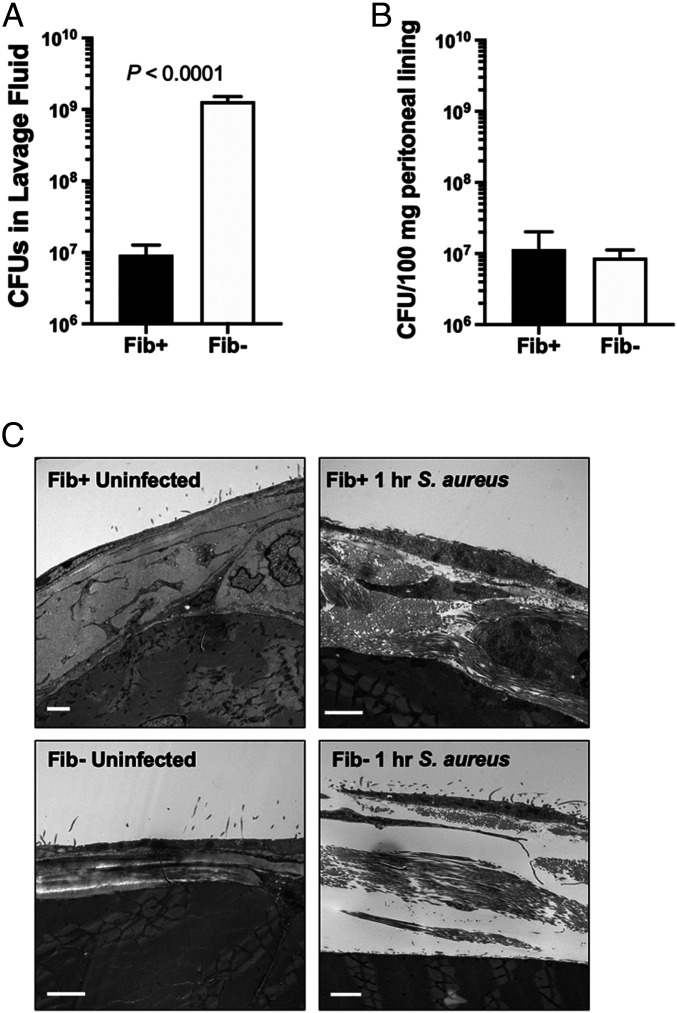

To determine whether the genotype-dependent increase in radiolabel associated with peritoneal structures was a function of fibrin(ogen)-dependent immobilization of viable bacteria, we evaluated the number of CFUs associated with the parietal peritoneum following infection. In contrast to the significant genotype-dependent difference in CFUs retrievable by lavage (Fig. 3A), CFUs associated with parietal peritoneum were similar and low in both genotypes, relative to the initial inoculum (Fig. 3B). Furthermore, TEM studies revealed edema and leukocyte infiltrates within the parietal peritoneum tissue from both Fib+ or Fib– mice, but no qualitative evidence of widespread association or entrapment of intact bacteria with mesothelial surfaces (Fig. 3C).

Fig. 3.

S. aureus associates with the peritoneal lining at low levels and equivalently in both Fib+ and Fib− mice following peritoneal infection. Fib+ and Fib− mice (n = 4 per group) were infected with 1 × 109 CFUs of S. aureus, and peritoneal lavage fluid was collected 1 h after infection. The number of CFUs present in lavage fluid (A) and associated with the peritoneal lining following homogenization (B) is shown. (C) Representative transmission electron microscopic views of parietal peritoneum sections from Fib+ (Upper) and Fib− (Lower) mice, uninfected (Left) and 1 h following infection with 1 × 109 CFUs of S. aureus (Right). Sections from Fib+- and Fib−-infected mice revealed an intact mesothelial cell layer but appeared inflamed and disrupted within the parietal peritoneum. Note that widespread association or entrapment of intact bacteria with mesothelial surfaces was not observed in material from infected mice of either genotype. (Scale bar, 2 μm.) CFU data are presented as mean ± SEM and analyzed by Mann−Whitney U test.

The identification of bacterial kill as the mechanism of clearance in the peritoneal cavity suggested a possible role for host immune cells. The speed of bacterial elimination further suggested that resident innate immune cells may be involved. We performed studies targeting neutrophils or macrophages to assess whether either of these cell types could be linked to elimination of S. aureus in the peritoneal cavity. Neutrophil depletion (SI Appendix, Fig. S2 A and B) had no impact on the rapid clearance of S. aureus from the peritoneal cavity. In addition, elevating neutrophil numbers in the peritoneal cavity (SI Appendix, Fig. S2 C and D) did not alter the S. aureus clearance pattern in Fib+ and Fib– mice (SI Appendix, Fig. S2E) despite evidence of neutrophil activation (i.e., detection of neutrophil elastase activity) in the peritoneal lavage fluid (SI Appendix, Fig. S2F). In contrast, clodronate liposome depletion of macrophages (SI Appendix, Fig. S3A) resulted in reduced S. aureus clearance from the peritoneal cavity in WT mice following infection (SI Appendix, Fig. S3B).

Prothrombin Procoagulant Activity, but Not Host Tissue Factor, Drives S. aureus Clearance in the Peritoneal Cavity.

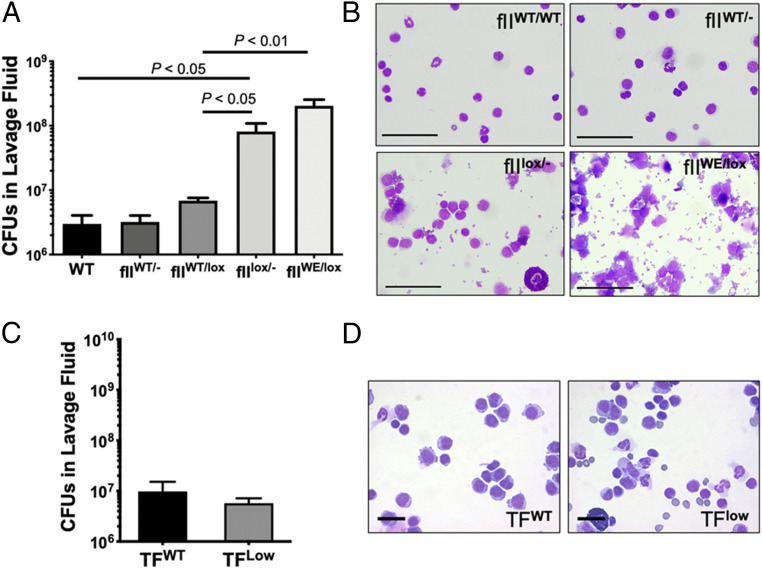

To explore the importance of prothrombin-derived protease function in the resolution of S. aureus peritonitis, infection analyses were performed in prothrombin mutant mice. Mice carrying 50 to 60% of normal (i.e., fIIWT/lox and fIIWT/-) and 10% of normal (i.e., fIIflox/-), or mice carrying one floxed allele and one allele encoding a serine protease domain active-site mutant with severely diminished procoagulant function (prothrombinWE; fIIWE) were analyzed. Note that the catalytic efficiency of murine thrombinWE with fibrinogen is ∼1,200-fold less than wild-type thrombin (21). A 40 to 50% reduction in circulating prothrombin (i.e., fIIWT/lox and fIIWT/-) resulted in the same bacterial clearance pattern as WT mice (Fig. 4A). In contrast, fIIflox/- mice expressing 10% of normal prothrombin displayed a significant failure in bacterial clearance. FIIWE-expressing mice (i.e., fIIWE/lox) also exhibited significantly reduced S. aureus clearance approaching that observed in Fib– mice (compare Fig. 4A to Fig. 1A). Since fIIWT/lox and fIIWE/lox mice carry the same overall level of prothrombin, this finding indicates that the protease function of (pro)thrombin underlies effective S. aureus clearance in the peritoneal cavity. Cytospin analyses of lavage fluid confirmed the patterns of microbial clearance from the peritoneal cavity (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

Bacterial clearance in the peritoneal cavity requires prothrombin procoagulant function but not host tissue factor. WT mice (fIIWT/WT), mice expressing 50 to 60% of normal prothrombin (fIIWT/- and fIIWT/lox), mice expressing 10% of normal prothrombin (fIIlox/-), and mice expressing 10% or normal prothrombin and 50% of normal levels of mutant prothrombin W215A/E217A (fIIlox/WE) were infected i.p. with 1 × 109 CFUs of S. aureus (n = 6 mice per group). (A) Lavage fluid was collected 1 h after infection and assayed for total CFUs. (B) Representative stained cytospin preparations of peritoneal lavage fluid harvested from mice. Note the relatively clear fields from control mice with no visible bacteria while fields from fIIWT/lox and fIIWE/lox mice show extensive free and cell-associated bacteria, reminiscent of cytospins from Fib− mice. (Scale bar, 50 μm.) WT mice (TFWT) and mice expressing ∼1% or normal tissue factor (TFlow) were challenged with 1 × 109 CFUs of S. aureus. (C) Total viable bacteria recovered from peritoneal lavage fluid collected 1 h after infection. (D) Representative stained cytospin preparations from TFWT and TFLow mice. Note that the lavage fluid from mice of each genotype are clear of free bacteria. (Scale bar, 20 μm.) CFU data are presented as mean ± SEM and analyzed by Mann−Whitney U test.

We next tested the concept that the source of thrombin-generating activity following S. aureus i.p. infection was host tissue factor. Remarkably, analysis of TFLow mice expressing ∼1% of normal tissue factor levels revealed that this host-derived initiator of thrombin generation was not required for antimicrobial function (Fig. 4 C and D). S. aureus CFUs observed in the lavage fluid from both TFWT and TFLow mice 1 h following i.p. infection were similar and both approximately two-orders-of-magnitude less than the original inoculum.

The Bacterial Coagulase vWbp Is Coupled to Fibrin(ogen)-Dependent Clearance in the Peritoneal Cavity.

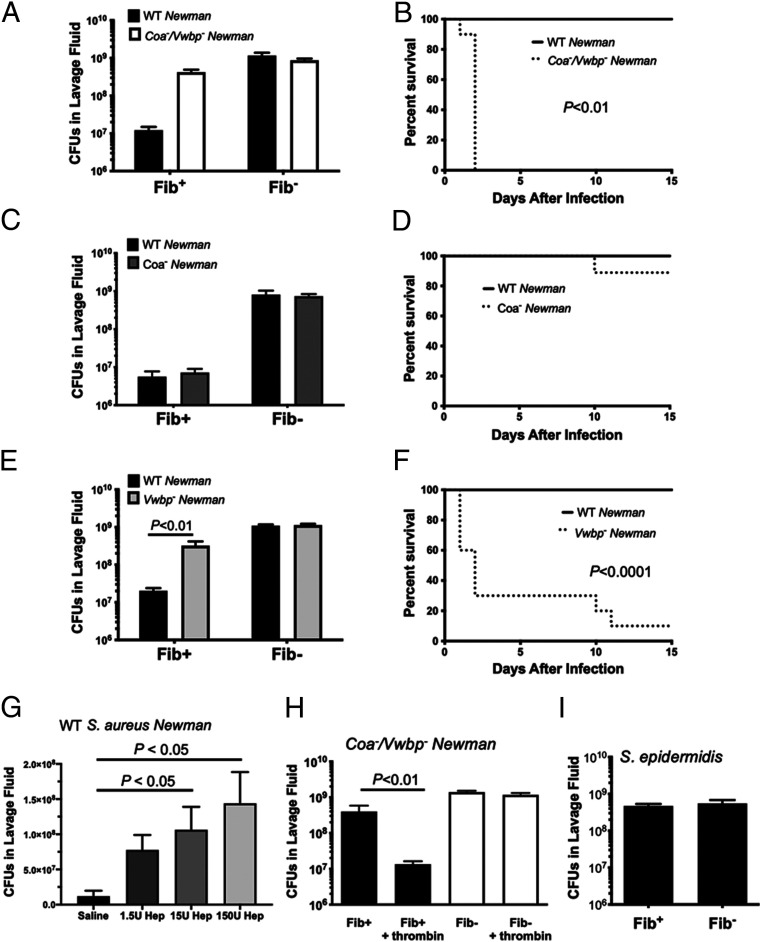

One hypothesis compatible with the unexpected finding that both prothrombin proteolytic function and fibrinogen, but not Tissue Factor (TF), are coupled to elimination of S. aureus in the peritoneal cavity, is that the expression of the S. aureus prothrombin activators Coa and/or Vwbp is actually counterproductive to microbial success in the abdominal space. We performed comparative analyses in mice challenged with isogenic strains of S. aureus Newman with single and combined deficits in Coa and Vwbp. In contrast to the WT S. aureus, Fib+ mice infected with Coa−/Vwbp− S. aureus exhibited a major impediment in bacterial clearance (Fig. 5A), similar to that observed with Fib– animals (Fig. 1A). This significant difference in S. aureus Newman Coa−/Vwbp− bacterial clearance in Fib+ mice translated to a significant and rapid reduction in host survival relative to that observed with Fib+ mice infected with WT S. aureus (Fig. 5B). To define the individual contributions of Coa and Vwbp, S. aureus with single deficits in Coa or Vwbp was examined. Analyses of Coa− S. aureus infection in Fib+ mice resulted in a pattern of bacterial clearance and host survival profile similar to that observed with WT S. aureus (Fig. 5 C and D). In contrast, mice challenged with Vwbp− S. aureus demonstrated ineffective clearance following infection with CFUs in the peritoneal lavage fluids similar to that initially injected (Fig. 5E). Fib+ mice also rapidly succumbed to infection by Vwbp- Newman S. aureus relative to WT Newman S. aureus (Fig. 5F). Thus, Vwbp, but not the closely related Coa, appears to be the coagulase primarily coupled to effective host clearance in fibrin(ogen)-sufficient mice. Consistent with a mechanistic linkage between bacterial prothrombin activators and fibrinogen, no S. aureus strain tested was efficiently eliminated from the peritoneal cavity of fibrin(ogen)-deficient mice regardless of the presence or absence of Vwbp and/or Coa (Fig. 5 A, C, and E).

Fig. 5.

S. aureus Vwbp-driven thrombin activity is required for host-mediated, fibrinogen-dependent bacterial killing mechanisms following peritonitis infection. Total viable bacteria in the lavage fluid 1 h after infection with 1 × 109 CFU bacteria (n = 5 mice per group) and host survival following infection with 5 × 108 CFU bacteria (n = 10 mice per group) of Fib+ and Fib− mice. Infections were performed with WT Newman strain bacteria along with Newman strain coa−/Vwbp− S. aureus (A and B), Newman strain Coa− S. aureus (C and D), or Newman strain Vwbp− S. aureus (E and F). Note the failure of bacterial clearance and rapid lethality of control mice infected with Newman strains of S. aureus lacking Vwbp, but not coa S. aureus. (G) Total CFU in peritoneal lavage fluid 1 h after infection with 1 × 109 CFU of WT Newman S. aureus in which WT mice were simultaneously treated with vehicle (n = 3), 1.5 U heparin (n = 5), 15 U heparin (n = 4), or 150 U heparin (n = 5). (H) CFU in lavage fluid collected from Fib+ and Fib− mice (n = 5–6 mice per group) treated with active thrombin (fIIa) or vehicle and simultaneously challenged with 1 × 109 CFU Vwbp− S. aureus. (I) Total viable bacteria in the lavage fluid of Fib+ and Fib- (n = 6 mice per group) following intraperitoneal infection with 1 × 109 CFU of S. epidermidis. CFU data presented as mean ± SEM and analyzed by Mann–Whitney U test. Survival data analyzed by Kaplan–Meier log-rank test.

Thrombin Activity, but Not Host vWF, Is Fundamental to the Clearance of vWbp+ S. aureus in the Peritoneal Cavity.

A function of Vwbp not shared by Coa is the capacity to bind host von Willebrand factor (vWF). To test whether host vWF was mechanistically tied to the Vwbp-associated clearance of S. aureus in the peritoneal cavity, cohorts of control and vWF-deficient mice were challenged in parallel with Vwbp+ (i.e., WT) bacteria. Quantitative analysis of CFUs within lavage fluids collected at 1 h revealed that bacterial clearance was comparably efficient in both control and vWF-deficient mice, implying little impact of the Vwbp:vWF interaction in this setting (SI Appendix, Fig. S4A). Mice challenged with Vwbp-deficient bacteria consistently exhibited high CFU values in the lavage fluid that resembled the input CFUs, regardless of whether the host animals carried or lacked vWF (SI Appendix, Fig. S4A). Analyses of Coa−/Vwbp−-deficient S. aureus in TFWT and TFlow mice revealed a failure to clear the microbes in mice of either genotype (SI Appendix, Fig. S4B), further supporting the notion that the bacteria are the source of thrombin-generating activity in S. aureus peritonitis required for clearance of the microbe.

To further confirm a role of proteolytically active thrombin, two complementary strategies were employed. First, treatment of Fib+ mice with heparin prior to WT S. aureus infection impaired bacterial clearance from the peritoneal cavity in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 5G). In a second analysis, Fib+ mice were challenged with Vwbp− S. aureus together with introduction of enzymatically active bovine α-thrombin or buffer vehicle. Predictably, mice challenged with Vwbp− S. aureus but no thrombin exhibited little bacterial elimination within 1 h. In contrast, mice injected with Vwbp− S. aureus together with exogenous thrombin exhibited a significant reduction in the residual CFUs observed (∼107 CFUs), approaching that observed with Vwbp+ S. aureus in Fib+ mice (Fig. 5H). Addition of exogenous thrombin could not induce bacterial clearance in Fib– mice, consistent with fibrin(ogen) as the primary downstream thrombin target required for bacterial clearance in the peritoneal cavity (Fig. 5H).

To verify that a naturally occurring CoNS staphylococcal strain would be insensitive to fibrinogen-dependent clearance, we challenged Fib+ and Fib– mice with Staphylococcus epidermidis. Unlike WT S. aureus, S. epidermidis was not cleared from the peritoneal cavity of Fib+ following i.p. infection. Rather, the number of CFUs of S. epidermidis retrieved from Fib+ and Fib– was roughly equivalent to that of the initial inoculum (Fig. 5I).

Discussion

Our results build on studies indicating that fibrinogen supports host inflammatory events following acute bacterial infection. Previous data examining S. aureus peritonitis in FibAEK mice, which express normal levels of fibrinogen with a mutation in the fibrinogen Aα chain rendering the molecule insensitive to thrombin cleavage, showed significantly reduced S. aureus clearance from the peritoneal cavity equivalent to Fib– mice (22). Logically, soluble fibrinogen would make a poor immune modulator since it is present in circulation in high concentrations. In contrast, fibrin matrices are absent from normal tissues, but are localized to sites of tissue damage where pathogens may be present. Thus, fibrin matrices make an ideal nondiffusible cue for inflammatory cell target recognition signaling local damage or local danger. Consistent with this notion, Fibγ390-396A mice expressing a mutant form of fibrinogen that lacks the leukocyte integrin αMβ2-binding motif exhibit an impairment in S. aureus clearance in the context of acute peritonitis, although less severe than that observed in Fib− mice (5). Notably, soluble fibrinogen monomer is a poor αMβ2 ligand (23). Collectively, these data match our present finding that thrombin procoagulant function is required for fibrin(ogen)-dependent killing of S. aureus in the peritoneal cavity.

Given the speed of bacterial elimination (i.e., as short as 15 min), the contribution of the fibrinogen αMβ2-binding motif, and polymer formation in this process, it seemed likely that resident peritoneal leukocytes would be part of the mechanism. Macrophages and neutrophils express high levels of αMβ2 that could contribute to fibrinogen-dependent clearance. We found that neither the elimination of neutrophils nor the elevation of neutrophil numbers in the peritoneal cavity altered the rapid clearance of microbes following infection. These findings suggest that the rapid S. aureus clearance observed here is not mediated by neutrophil aggregates or neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) as has been indicated for other types of inflammatory peritoneal insults (24).

Previous studies indicated that macrophage depletion results in reduced bacterial clearance for S. aureus and other pathogens (25, 26). Here, we also document a reduction in S. aureus clearance following macrophage depletion. Our identification of fibrin formation as being intimately tied to bacterial clearance in the peritoneal cavity is consistent with a previous report highlighting a role for peritoneal macrophage-driven fibrin formation in host defense (26). That study suggested that tissue factor and factor V expression by large peritoneal macrophages was required for the clearance of Escherichia coli. Given that we find that the elimination of S. aureus coagulase activity is sufficient to prevent bacterial clearance of this microbe, it may be that fibrin formation is a point of commonality for host defense in the peritoneal cavity, but the mechanism of fibrin formation could be pathogen specific. Intriguingly, macrophages have also been shown to serve as a protective “haven” for phagocytosed bacteria preventing elimination by other host defense mechanisms (27). Such data are consistent with our observations of cytospin preparations from lavage fluid of fibrinogen-deficient mice showing evidence of robust phagocytosis following infection, suggesting that fibrinogen-dependent kill relies on extracellular antimicrobial mechanisms (Fig. 1E). A role for nontraditional immune cells is possible. Mesothelial cells cover all peritoneal surfaces and are an abundant cell type in the peritoneal cavity. Mesothelial cells could be extremely efficient in bacterial clearance as they have been linked to immune responses and can engage fibrinogen through the adhesion molecule ICAM-1 (28–31). Future studies will more directly elucidate downstream mechanisms and cell types required for fibrinogen-dependent bacterial kill in acute peritonitis.

The data presented here indicate that S. aureus drives thrombin generation in the peritoneal cavity rather than host TF following infection. Indeed, the clearance of WT bacteria was unaffected by significant reduction of host TF, but, when S. aureus lacked both Coa and Vwbp, clearance was compromised in both WT mice and TFlow mice. Although studies of S. aureus peritonitis remain to be performed in WT and TFlow mice with single deficient bacteria (i.e., Coa- only or Vwbp- only), the data suggest that Vwbp was required for thrombin generation. The finding that S. aureus elimination from the peritoneal cavity depends on Vwbp-induced prothrombin protease zymogen activation is counter to the assumption that bacteria produce virulence factors necessary for their survival in hosts. One possible explanation is that Vwbp is beneficial for the bacteria in certain infection settings, and this powerful benefit outweighs the detrimental impact in the context of peritonitis. Previous findings suggest that Vwbp and Coa increase bacterial virulence in a mouse model of S. aureus bacteremia/sepsis with Vwbp and Coa expression increasing kidney abscesses and decreasing survival in mice (15, 32). Another disease context where Vwbp appears to provide benefit to the bacteria is in endocarditis (33). It is not clear why Vwbp, but not Coa, would play a role in peritoneal infection when both demonstrate similar prothrombin activation properties (i.e., prothrombin complex formation and fibrinogen cleavage), both are secreted proteins, and both are generally expressed at similar times during S. aureus growth (34). One possibility is that, although both are secreted, Vwbp binds back to the S. aureus cell wall and activates prothrombin via a hysteretic mechanism (35, 36), which requires binding of fibrinogen in order for formation of an active complex. The colocalization at the bacteria surface would thus concentrate all of the key molecular components presumably resulting in a rapid and efficient antimicrobial mechanism.

The identification of a prothrombin/fibrin-coupled antimicrobial pathway triggered by a bacteria-derived prothrombin activator provides possible insight into why staphylococcal peritonitis, an infection particularly prevalent in cirrhotic patients and those requiring peritoneal dialysis, is mediated predominantly by CoNS as opposed to coagulase-positive staphylococci like S. aureus (9–13). Analyses here were conducted with strain Newman S. aureus specifically due to the availability of genetic mutants lacking Coa, Vwbp, or both. Whether or not other strains of S. aureus are susceptible to the same antimicrobial pathways remains a significant open question. Since different strains of S. aureus can express Coa and vWbp at varying levels and express other unique virulence factors, it is possible that sensitivity to this prothrombin/fibrin-coupled host response is variable (37). We previously demonstrated that USA300, a community strain of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, was also highly sensitive to fibrin-dependent clearance from the peritoneal cavity, supporting a potential broad applicability of the identified pathway to S. aureus strains (22).

Bacterial infection can lead to a procoagulant condition, and anticoagulation therapy is often employed to mitigate thrombotic complications (38–40), but present results provide a word of caution for treating patients with bacterial infections with anticoagulants. Indeed, our findings revealed that treatment of mice with heparin resulted in compromised bacterial elimination from the peritoneal cavity. These results support testing to determine etiology, pathogen species, and peritoneal involvement to mitigate potential deleterious consequences of a worsening infection secondary to anticoagulation. Finally, inflammatory diseases (e.g., multiple sclerosis, arthritis, colitis) are often linked to infection as an etiological initiator, disease driver, or secondary consequence (1, 2, 41). Our previous (5, 22) and present findings highlight a significant risk that must be considered when employing treatment strategies aimed at targeting the fibrin(ogen) αMβ2-binding motif (42).

Materials and Methods

Mice.

All mice used in these studies were backcrossed onto a C57BL/6J background for at least seven generations. Fibrinogen Aα chain-deficient (Fib−) mice were previously described (43). In addition, fIIflox, fIIW215A/E217A (fIIWE), and TFLow were each previously described (44–46). Von Willebrand Factor-deficient mice (vWF−/−) were previously characterized (47). All mouse experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at either the Children’s Hospital Research Foundation, Cincinnati, Ohio, or the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC.

Bacteria Strains, Growth, and Acute Infections Using Unlabeled S. aureus.

S. aureus Newman and S. epidermidis were provided by T. J. Foster (Trinity College, Dublin). Mutant S. aureus Newman strains, including Coa-deficient, vWbp-deficient, and Coa/vWbp-deficient strains, were provided by O. Schneewind (University of Chicago, Chicago) (32). Bacteria were grown in Tryptic Soy Broth (TSB) (BD Biosciences) at 37 °C overnight to confluence. For peritonitis, bacteria were washed twice in sterile PBS, resuspended to a concentration of 5 × 108 to 1 × 109 CFUs, and 1 mL of suspension was injected intraperitoneally into 8- to 12-wk-old sex-matched mice. For host survival analysis, mice were euthanized and categorized as dead upon reaching a moribund state. For bacterial clearance, peritoneal lavage fluid was collected in sterile PBS, and serial dilutions were plated on tryptic soy agar to determine the number of CFUs. For pharmacological thrombin inhibition, heparin (porcine) sodium at 1,000 U/mL was diluted, and 1 mL of stock solutions was injected i.p. immediately before peritonitis challenge. For thrombin addition experiments, bovine thrombin (Enzyme Research Laboratories) was diluted in sterile PBS and injected immediately prior to bacteria. Methods of pleural cavity infection are described in SI Appendix.

Fate-Tracking Experiments Using Radiolabeled Bacteria.

For bacteria fate, S. aureus was grown in TSB to an OD600 of 0.6 and then collected by centrifugation. The bacterial cell pellet was suspended in saline with 25 μCi of [125I]-iododeoxyuridine and incubated with shaking at 37 °C for 2 h followed by addition of TSB and incubation at 37 °C for 3 h. Bacteria were collected, suspended in fresh TSB, and incubated overnight at 37 °C. The radiolabeled culture was collected, washed in PBS, and suspended in PBS to a concentration of 1 × 109 CFUs/mL. Trichloroacetic acid precipitation was performed to document the percentage CPM incorporated into macromolecules. Intraperitoneal infections were performed as described for collection of peritoneal lavage fluid and organ systems. Radioisotope levels were measured with a Cobra gamma counter (Packard). CFUs were quantified as described. Tissue samples were weighed and rinsed thoroughly with PBS prior to measurement of radioisotope CPM.

Immune Cell Depletion and Neutrophil Increase.

Methods of immune cell changes are described in SI Appendix.

Electron Microscopy of Tissue Sections and Lavage Fluid Filtrates.

For TEM, tissues were fixed in 3% glutaraldehyde, postfixed in 1% osmic acid, and processed into LX 112 plastic embedding media. Thin sections were stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate and evaluated on a Zeiss 110 electron microscope. For SEM, lavage fluid was fixed with 3% glutaraldehyde and passed through a 0.2-μM polycarbonate membrane filter (Sterlitech). Filters were dehydrated in ethanol washes and then processed in an EM CPD300 critical endpoint dryer (Leica Microsystems) and sputter-coated with gold/palladium using a Desk IV Vacuum Sputter System (Denton Vacuum), and images were collected using a SU8010 Scanning Electron Microscope (Hitachi Science Systems).

Statistics.

The N number for each analyzed group is indicated in the figure legends. All experiments were performed at least twice with similar results with the exception of survival studies which were performed once due to ethical considerations. Statistical analysis was performed using Graphpad Prism 8.3.1. Data were analyzed for normality and subsequently analyzed using two-way ANOVA, Student’s t test, or Mann–Whitney U test as appropriate. Survival curves were analyzed using the Kaplan–Meier log-rank test.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Carolina Cruz, Maureen Shaw, and Sara Abrahams for their technical assistance in conducting these studies. This work was supported by NIH Grants including R01HL085357 (to J.L.D.), R01DK112778 (to M.J.F.), U01HL143403 (to M.J.F.), R01CA211098 (to M.J.F.), and R01AI020624 (to M.H.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission. G.J.R. is a guest editor invited by the Editorial Board.

This article contains supporting information online at https://www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.2009837118/-/DCSupplemental.

Data Availability.

All study data are included in the article and SI Appendix.

References

- 1.Flick M. J., et al. , Fibrin(ogen) exacerbates inflammatory joint disease through a mechanism linked to the integrin alphaMbeta2 binding motif. J. Clin. Invest. 117, 3224–3235 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Steinbrecher K. A., et al. , Colitis-associated cancer is dependent on the interplay between the hemostatic and inflammatory systems and supported by integrin alpha(M)beta(2) engagement of fibrinogen. Cancer Res. 70, 2634–2643 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cole H. A., et al. , Fibrin accumulation secondary to loss of plasmin-mediated fibrinolysis drives inflammatory osteoporosis in mice. Arthritis Rheumatol. 66, 2222–2233 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vidal B., et al. , Amelioration of Duchenne muscular dystrophy in mdx mice by elimination of matrix-associated fibrin-driven inflammation coupled to the αMβ2 leukocyte integrin receptor. Hum. Mol. Genet. 21, 1989–2004 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Flick M. J., et al. , Leukocyte engagement of fibrin(ogen) via the integrin receptor alphaMbeta2/Mac-1 is critical for host inflammatory response in vivo. J. Clin. Invest. 113, 1596–1606 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Luo D., et al. , Protective roles for fibrin, tissue factor, plasminogen activator inhibitor-1, and thrombin activatable fibrinolysis inhibitor, but not factor XI, during defense against the gram-negative bacterium Yersinia enterocolitica. J. Immunol. 187, 1866–1876 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smiley S. T., King J. A., Hancock W. W., Fibrinogen stimulates macrophage chemokine secretion through toll-like receptor 4. J. Immunol. 167, 2887–2894 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Szaba F. M., Smiley S. T., Roles for thrombin and fibrin(ogen) in cytokine/chemokine production and macrophage adhesion in vivo. Blood 99, 1053–1059 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Geoghegan J. A., et al. , Molecular characterization of the interaction of staphylococcal microbial surface components recognizing adhesive matrix molecules (MSCRAMM) ClfA and Fbl with fibrinogen. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 6208–6216 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hartford O. M., Wann E. R., Höök M., Foster T. J., Identification of residues in the Staphylococcus aureus fibrinogen-binding MSCRAMM clumping factor A (ClfA) that are important for ligand binding. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 2466–2473 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McDevitt D., et al. , Characterization of the interaction between the Staphylococcus aureus clumping factor (ClfA) and fibrinogen. Eur. J. Biochem. 247, 416–424 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ko Y. P., et al. , Coagulase and Efb of Staphylococcus aureus have a common fibrinogen binding motif. mBio 7, e01885-15 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Friedrich R., et al. , Staphylocoagulase is a prototype for the mechanism of cofactor-induced zymogen activation. Nature 425, 535–539 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thomas S., et al. , The complex fibrinogen interactions of the Staphylococcus aureus coagulases. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 9, 106 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McAdow M., Missiakas D. M., Schneewind O., Staphylococcus aureus secretes coagulase and von Willebrand factor binding protein to modify the coagulation cascade and establish host infections. J. Innate Immun. 4, 141–148 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lloyd A., et al. , The risk of peritonitis after an exit site infection: A time-matched, case-control study. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 28, 1915–1921 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barretti P., et al. , Peritoneal dialysis-related peritonitis due to Staphylococcus aureus: A single-center experience over 15 years. PLoS One 7, e31780 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alexopoulou A., et al. , Increasing frequency of gram-positive cocci and gram-negative multidrug-resistant bacteria in spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Liver Int. 33, 975–981 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Govindarajulu S., et al. , Staphylococcus aureus peritonitis in Australian peritoneal dialysis patients: Predictors, treatment, and outcomes in 503 cases. Perit. Dial. Int. 30, 311–319 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ribeiro T. C., et al. , Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis: How to deal with this life-threatening cirrhosis complication? Ther. Clin. Risk Manag. 4, 919–925 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cantwell A. M., Di Cera E., Rational design of a potent anticoagulant thrombin. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 39827–39830 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Prasad J. M., et al. , Mice expressing a mutant form of fibrinogen that cannot support fibrin formation exhibit compromised antimicrobial host defense. Blood 126, 2047–2058 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lishko V. K., Kudryk B., Yakubenko V. P., Yee V. C., Ugarova T. P., Regulated unmasking of the cryptic binding site for integrin alpha M beta 2 in the gamma C-domain of fibrinogen. Biochemistry 41, 12942–12951 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jackson-Jones L. H., et al. , Stromal cells covering omental fat-associated lymphoid clusters trigger formation of neutrophil aggregates to capture peritoneal contaminants. Immunity 52, 700–715.e6 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brown A. F., et al. , Memory Th1 cells are protective in invasive Staphylococcus aureus infection. PLoS Pathog. 11, e1005226 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang N., et al. , Expression of factor V by resident macrophages boosts host defense in the peritoneal cavity. J. Exp. Med. 216, 1291–1300 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jorch S. K., et al. , Peritoneal GATA6+ macrophages function as a portal for Staphylococcus aureus dissemination. J. Clin. Invest. 129, 4643–4656 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shaw T. J., et al. , Human peritoneal mesothelial cells display phagocytic and antigen-presenting functions to contribute to intraperitoneal immunity. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 26, 833–838 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hwang E. H., et al. , Toll/IL-1 domain-containing adaptor inducing IFN-β (TRIF) mediates innate immune responses in murine peritoneal mesothelial cells through TLR3 and TLR4 stimulation. Cytokine 77, 127–134 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Colmont C. S., et al. , Human peritoneal mesothelial cells respond to bacterial ligands through a specific subset of Toll-like receptors. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 26, 4079–4090 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yang X., et al. , CD40 is expressed on rat peritoneal mesothelial cells and upregulates ICAM-1 production. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 19, 1378–1384 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cheng A. G., et al. , Contribution of coagulases towards Staphylococcus aureus disease and protective immunity. PLoS Pathog. 6, e1001036 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Panizzi P., et al. , In vivo detection of Staphylococcus aureus endocarditis by targeting pathogen-specific prothrombin activation. Nat. Med. 17, 1142–1146 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McAdow M., et al. , Coagulases as determinants of protective immune responses against Staphylococcus aureus. Infect. Immun. 80, 3389–3398 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kroh H. K., Bock P. E., Effect of zymogen domains and active site occupation on activation of prothrombin by von Willebrand factor-binding protein. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 39149–39157 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kroh H. K., Panizzi P., Bock P. E., Von Willebrand factor-binding protein is a hysteretic conformational activator of prothrombin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 7786–7791 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McCarthy A. J., Lindsay J. A., Genetic variation in Staphylococcus aureus surface and immune evasion genes is lineage associated: Implications for vaccine design and host-pathogen interactions. BMC Microbiol. 10, 173 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gardiner E. E., Andrews R. K., Neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) and infection-related vascular dysfunction. Blood Rev. 26, 255–259 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chopra V., Anand S., Krein S. L., Chenoweth C., Saint S., Bloodstream infection, venous thrombosis, and peripherally inserted central catheters: Reappraising the evidence. Am. J. Med. 125, 733–741 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Martin E., Cevik C., Nugent K., The role of hypervirulent Staphylococcus aureus infections in the development of deep vein thrombosis. Thromb. Res. 130, 302–308 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Adams R. A., et al. , The fibrin-derived gamma377-395 peptide inhibits microglia activation and suppresses relapsing paralysis in central nervous system autoimmune disease. J. Exp. Med. 204, 571–582 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ryu J. K., et al. , Fibrin-targeting immunotherapy protects against neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration. Nat. Immunol. 19, 1212–1223 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Suh T. T., et al. , Resolution of spontaneous bleeding events but failure of pregnancy in fibrinogen-deficient mice. Genes Dev. 9, 2020–2033 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mullins E. S., et al. , Genetic elimination of prothrombin in adult mice is not compatible with survival and results in spontaneous hemorrhagic events in both heart and brain. Blood 113, 696–704 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Flick M. J., et al. , The development of inflammatory joint disease is attenuated in mice expressing the anticoagulant prothrombin mutant W215A/E217A. Blood 117, 6326–6337 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Parry G. C., Erlich J. H., Carmeliet P., Luther T., Mackman N., Low levels of tissue factor are compatible with development and hemostasis in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 101, 560–569 (1998).9449688 [Google Scholar]

- 47.Denis C., et al. , A mouse model of severe von Willebrand disease: Defects in hemostasis and thrombosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 9524–9529 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All study data are included in the article and SI Appendix.