Abstract

Background

We examined Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) seroconversion incidence and risk factors 21 days after baseline screening among healthcare workers (HCWs) in a resource-limited setting.

Methods

A prospective cohort study of 4040 HCWs took place at 12 university healthcare facilities in Cairo, Egypt; April-June 2020. Follow-up exposure and clinical data were collected through online survey. SARS-CoV-2 testing was done using rapid IgM and IgG serological tests and reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) for those with positive serology. Cox proportional hazards modelling was used to estimate adjusted hazard ratios (HR) of seroconversion.

Results

3870/4040 (95.8%) HCWs tested negative for IgM, IgG and PCR at baseline; 2282 (59.0%) returned for 21-day follow-up. Seroconversion incidence (positive IgM and/or IgG) was 100/2282 (4.4%, 95% CI:3.6-5.3), majority asymptomatic (64.0%); daily hazard of 0.21% (95% CI:0.17-0.25)/48 746 person-days of follow-up. Seroconversion was: 4.0% (64/1596; 95% CI:3.1-5.1) among asymptomatic; 5.3% (36/686; 95% CI:3.7-7.2) among symptomatic HCWs. Seroconversion was independently associated with older age; lower education; contact with a confirmed case >15 min; chronic kidney disease; pregnancy; change/loss of smell; and negatively associated with workplace contact.

Conclusions

Most seroconversions were asymptomatic, emphasizing need for regular universal testing. Seropositivity was three-fold that observed at baseline. Cumulative infections increased nationally by a similar rate, suggesting HCW infections reflect community not nosocomial transmission.

Keywords: COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, seroconversion, cohort, healthcare workers, asymptomatic

Introduction

As of 15 November 2020, more than 54.5 million cases of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and 1.3 million deaths have been documented globally (Johns Hopkins University of Medicine, 2020). Reports of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection in healthcare workers (HCWs), mainly in high-income settings, vary widely (0.4-57.1%) with a pooled prevalence of 11% and 7% by reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) and serology testing, respectively (Gómez-Ochoa et al., 2020).

Studies examining seroconversion in HCW cohorts, particularly in resource-limited settings, are scarce. One UK study reported 20% seroconversion among HCWs within 1 month of follow-up (Houlihan et al., 2020). Silent (subclinical or asymptomatic) seroconversion was reported in a limited number of non-HCW (6/9, 67.0%) (Hung et al., 2020) and HCW cohorts (11/25, 44.0%) (Hains et al., 2020). Asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 carriage among HCWs has been reported at 68.2% (Mostafa et al., 2020) and 86% (Mandić-Rajčević et al., 2020). Serological testing can help in diagnosis of suspected cases with negative RT–PCR test results and in early identification of asymptomatic infections (Long et al., 2020). Antibodies specific to SARS-CoV-2 appear within 2 weeks and peak 3-4 four weeks after infection (Seow et al., 2020) and can therefore help to detect cases not detectable during the acute phase. Universal regular screening of HCWs enables prompt detection, isolation, and management of cases, including asymptomatic infections, protecting HCWs and patients.

In Egypt, as of 15 November 2020, 110 767 COVID-19 cases have been detected through the national symptom-based testing using PCR and 6453 deaths have occurred (Ministry of Health and Population, 2020). By mid-October 2020, it was estimated that 3576 COVID-19 cases (1.6%) and 188 deaths (5.3%) have occurred among 220 000 Egyptian physicians (Alarabiya News, 2020).

To understand the extent of SARS-CoV-2 infection among a cohort of HCWs in a resource-limited setting, we conducted a prospective investigation including baseline and follow-up screening and risk assessment of HCWs (SARAH: NCT04348214). The baseline screening phase of 4040 HCWs in Ain Shams University (ASU) medical campus, including 12 university healthcare facilities in Cairo, Egypt has been described previously (Mostafa et al., 2020). The infection proportion among HCWs at baseline (positive IgM, or IgG, or PCR) was 4.2% (170/4040, 95% CI 3.6-4.9). The baseline seroprevalence (positive IgM and/or IgG) was 1.3% (n = 53/4040, 95% CI 1.0-1.7). In this paper, we describe the follow-up screening phase. We present the incidence of seroconversion after 21 days of follow-up using rapid serological tests and the associated risk factors among HCWs who tested negative for SARS-CoV-2 by IgM, IgG, and PCR at baseline. We also report the follow-up test results of the 170 HCWs who were infected at baseline.

Methods

Study design and participants

We conducted a prospective cohort study in 12 ASU healthcare facilities, where follow-up procedures took place between 14 May and 10 June 2020, after 21 days from the baseline screening (World Health Organization, 2020a). The baseline study design, setting, participants, tools, procedures, and findings have been previously described (Mostafa et al., 2020). Baseline screening was conducted between 22 April and 14 May 2020 and included an online survey plus laboratory testing to assess SARS-CoV-2 seroprevalence. Follow-up screening also included an online survey to assess the occurrence of symptoms and exposure to a confirmed case during the follow-up period, plus laboratory testing to assess the incidence of SARS-CoV-2 seroconversion.

All HCWs who participated at baseline were informed about the follow-up screening procedures and schedule, for which they had provided written informed consent during the baseline recruitment process. They were all invited to participate at the follow-up phase with no exclusion criteria, i.e. follow-up screening targeted all hospital staff regardless of their baseline test results, the type of care they provided (clinical or non-clinical), presence of symptoms (asymptomatic HCWs were included), or place of work within the healthcare facility (no units/wards were prioritized for follow-up screening). This study was approved by the Ethics Review Committee, Faculty of Medicine, ASU (FMASUP18b/2020).

Data collection

Participation was voluntary and all HCWs on-the-job were informed and scheduled for follow-up screening through formal announcements by their healthcare facility administration. Also, all participants received phone call reminders to attend their scheduled follow-up appointments and were rescheduled within a period of 3 days to provide flexibility according to their workload if needed. At each of the 12 healthcare facilities, HCWs visited the 2 workstations dedicated for follow-up screening procedures. Teams consisting of the hospital management, infection control focal points, nurses, technicians, and administrative staff coordinated the screening activities.

Workstation 1. Online survey

HCWs completed the follow-up survey through available PCs with an internet connection or their cellphones to reduce the screening time and unnecessary contact with shared surfaces. Staff were available to interview HCWs who needed assistance in filling the survey. Data were entered using the assigned study ID to facilitate anonymous linkage with laboratory results.

Workstation 2. Laboratory sampling

At follow-up, a 5 ml venous blood sample was collected by venipuncture into a plain vacutainer for the qualitative detection of SARS-CoV-2 IgM and IgG antibodies. For those who tested positive for serology, an appointment was scheduled for RT-PCR, where combined nasal and oropharyngeal swabs were collected in a single tube containing viral transport medium for detecting viral RNA by RT-PCR (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2020a). Swabs were transported to the laboratory in iceboxes at 4 °C.

Study tools and measures

Online survey

Questions were adapted from relevant World Health Organization protocols and interim guidance (World Health Organization, 2020b, World Health Organization, 2020c). Details of the questionnaire development and data on background characteristics were previously described (Mostafa et al., 2020). The follow-up survey consisted of 2 sections including questions on exposures and symptoms that had occurred in the period since baseline screening:

Section 1: HCWs were provided with an exhaustive list of symptoms suggestive of COVID-19 and were asked to report the occurrence, type, and severity of symptoms since baseline screening: fever <38 °C, fever ≥38 °C, chills, fatigue, muscle pain, joint pain, sore throat, dry cough, cough with sputum, runny nose/nasal congestion, sneezing, shortness of breath, wheezing, chest pain, other respiratory symptoms, nausea, vomiting, abdominal discomfort/pain, diarrhea, headache, confusion, loss of appetite, change/loss of taste or smell, skin rash, and conjunctivitis.

Section 2: HCWs reported community and nosocomial exposure through close contact with a confirmed COVID-19 case and when and where the contact had occurred. In the nosocomial exposure section, we asked about direct care provision for a confirmed case, face-to-face contact within 2 m, and the duration of contact.

Laboratory tests

Detection of SARS-CoV-2 IgM and IgG antibodies was done using the lateral flow immunochromatographic assay Artron® One Step COVID-19 IgM/IgG Antibody Test, the same method used at baseline (Artron Laboratories Inc., Canada). The assay has sensitivity and specificity of 83.3% and 100%, respectively, as estimated by Lassaunière et al. (Lassaunière et al., 2020) and 94.4% and 98.2%, respectively, as estimated by Zhang and Zheng (Zhang and Zheng, 2020). RT-PCR testing was done only for seropositive cases at follow-up, using the same baseline technique previously described (Mostafa et al., 2020, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2020a).

Case definition

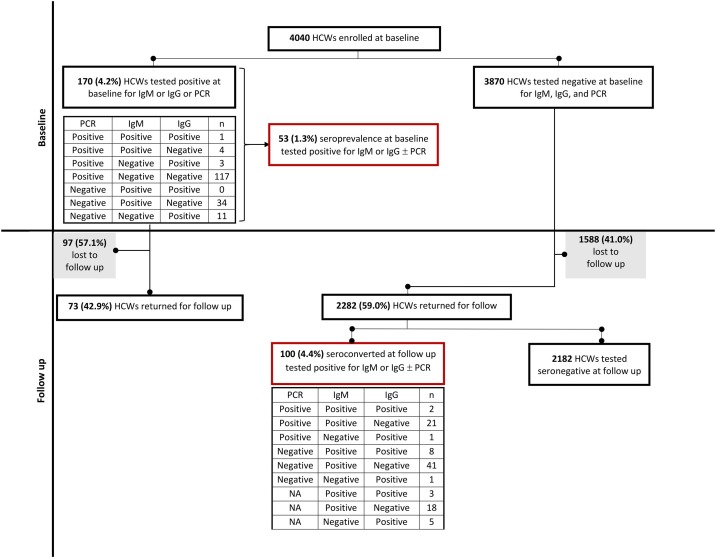

Seroconversion was defined as having a positive test result at the follow-up phase for IgM and/or IgG among HCWs who tested negative for all 3 tests (IgM, IgG and PCR) at baseline (n = 3870) ( Figure 1 ).

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the cohort study and test results

Statistical analysis

For describing the study sample, we calculated median and interquartile ranges (IQR) for continuous variables or counts and proportions for categorical variables. To calculate the incidence proportion and the hazard of seroconversion, the number of IgM and/or IgG positive HCWs was divided by the number of participants and person-days of follow-up, respectively. Multivariable Cox proportional hazard regression modelling was used to determine the independent determinants of seroconversion and to estimate the adjusted hazard ratios and 95% CIs. Effect estimates with CIs and exact P values are provided. All analyses were done using SPSS version 25.

Results

Between 14 May and 10 June 2020, 2282 (59.0%) HCWs returned for testing at follow-up out of the 3870 HCWs who tested negative at baseline for IgM, IgG and PCR ( Figure 1 ). The median follow-up period was 25 days (IQR 21-27). The incidence of SARS-CoV-2 seroconversion (positive IgM and/or IgG) was 100/2282 (4.4%, 95% CI 3.6-5.3) and the daily hazard was 0.21% (95% CI 0.17-0.25) over 48746 person-days of follow-up. Of the 100 seroconverted HCWs, 59 (59.0%) tested positive only for IgM, 6 (6.0%) tested positive only for IgG, and 11 (11.0%) tested positive for both IgM and IgG. Twenty-one (21.0%) tested positive for both PCR and IgM, 1 (1.0%) tested positive for both PCR and IgG, and 2 (2.0%) tested positive for all 3 tests ( Figure 1 ).

The overall description for the follow-up group is presented in Table 1 . The median age was 32 years (IQR 27-42) for the follow-up group and 40 years (IQR 33.0-47.0) for seroconverters. Most seroconverters were female HCWs 78/100 (78.0%) and nurses 54 (54.0%). Three of the seroconverters were pregnant and all were symptomatic. Background characteristics of the study cohort at baseline and follow-up are presented in Supplementary Table 1.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics and the risk of seroconversion among the cohort of health care workers in the follow-up screening, May-June 2020, Cairo, Egypt (N = 2282).

| Total | Event/Person-days | Hazard (daily) | Unadjusted hazard ratio (95% CI)a | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | N = 2282 no. (%) | 100/48746 | 0.21% | ||

| Age | |||||

| 18 to 29 | 960 (42.1) | 15/19554 | 0.08% | Ref | |

| 30 to 39 | 587 (25.7) | 33/12452 | 0.27% | 3.42 (1.86–6.30) | <0.001 |

| 40 to 49 | 465 (20.4) | 29/10232 | 0.28% | 3.58 (1.91–6.70) | <0.001 |

| ≥ 50 | 270 (11.8) | 23/6508 | 0.35% | 4.19 (2.18–8.08) | <0.001 |

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 792 (34.7) | 22/16320 | 0.13% | Ref | |

| Female | 1490 (65.3) | 78/32426 | 0.24% | 1.63 (1.01–2.61) | 0.044 |

| Governorate of residence | |||||

| Outside Cairo | 525 (23.0) | 18/10937 | 0.16% | Ref | |

| Cairo | 1757 (77.0) | 82/37809 | 0.22% | 1.24 (0.75–2.07) | 0.407 |

| Urban/rural residence | |||||

| Urban | 2004 (87.8) | 89/42999 | 0.21% | Ref | |

| Rural | 278 (12.2) | 11/5747 | 0.19% | 0.96 (0.51–1.80) | 0.895 |

| Marital status | |||||

| Not married | 971 (42.6) | 21/20226 | 0.10% | Ref | |

| Married | 1311 (57.4) | 79/28520 | 0.28% | 2.43 (1.50–3.94) | <0.001 |

| Education | |||||

| University or higher | 1125 (49.3) | 24/23857 | 0.10% | Ref | |

| Secondary | 928 (40.7) | 55/19783 | 0.28% | 2.56 (1.58–4.14) | <0.001 |

| Primary or preparatory | 153 (6.7) | 13/3337 | 0.39% | 4.42 (2.24–8.70) | <0.001 |

| Less than primary | 76 (3.3) | 8/1769 | 0.45% | 4.68 (2.09–10.47) | <0.001 |

| Occupation | |||||

| Physician | 777 (34.0) | 13/15968 | 0.08% | Ref | |

| Nurse | 946 (41.5) | 54/20139 | 0.27% | 3.01 (1.64–5.53) | <0.001 |

| Non-clinical care | 559 (24.5) | 33/12639 | 0.26% | 3.26 (1.70–6.22) | <0.001 |

| Tobacco use | |||||

| No | 1983 (86.9) | 91/42592 | 0.21% | Ref | |

| Current | 257 (11.3) | 8/5358 | 0.15% | 0.74 (0.36–1.53) | 0.417 |

| Past | 42 (1.8) | 1/796 | 0.13% | 0.73 (0.10–5.26) | 0.757 |

| Self-reported pre-existing medical condition | |||||

| No | 1852 (81.2) | 70/39167 | 0.18% | Ref | |

| Yes | 430 (18.8) | 30/9579 | 0.31% | 1.6 (1.04–2.45) | 0.031 |

Hazard ratio (95% CI) were calculated using Cox regression

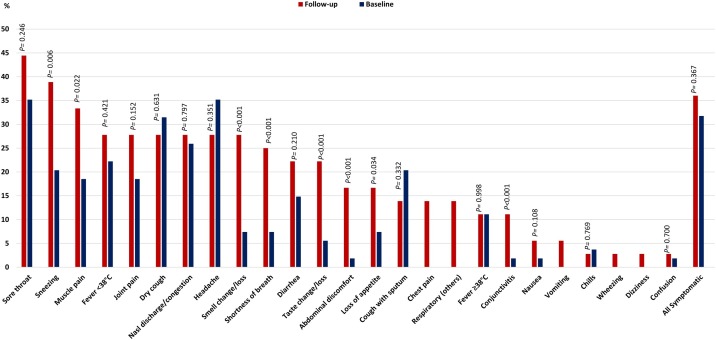

Only 36/100 (36.0%) seroconverters reported being symptomatic during the follow-up period; 3/36 (8.3%) reported severe symptoms ( Table 2 ). Experiencing symptoms suggestive of SARS-CoV-2 infection were more frequently reported during follow-up than at baseline ( Figure 2 ), such as sneezing, muscle pain, change/loss of smell, shortness of breath, change/loss of taste, abdominal discomfort, loss of appetite, and conjunctivitis. Symptoms that were not reported at baseline, but only at the follow-up stage among seroconverters were chest pain, other respiratory symptoms, vomiting, wheezing, and dizziness ( Figure 2 ). The incidence of seroconversion was 4.0% (64/1596, 95% CI 3.1-5.1) among asymptomatic and 5.3% among symptomatic HCWs (36/686, 95% CI 3.7-7.2).

Table 2.

Exposures, presence of symptoms, and the risk of seroconversion among the cohort of health care workers in the follow-up screening, May-June 2020, Cairo, Egypt (N = 2282).

| Total | Event/Person-days | Hazard (daily) | Unadjusted hazard ratio (95% CI)a | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | N = 2282 no. (%) | 100/48746 | 0.21% | ||

| Contact with a confirmed case | |||||

| No | 1151 (50.4) | 61/27664 | 0.22% | Ref | |

| Yes | 1131 (49.6) | 39/21082 | 0.18% | 0.75 (0.49–1.13) | 0.162 |

| Location of contact with a confirmed case | n = 1131 | n = 39 | |||

| Home/Residential area | 45 (4.0) | 5/860 | 0.58% | Ref | |

| Workplace | 1086 (96.0) | 34/20222 | 0.17% | 0.29 (0.11–0.73) | 0.009 |

| Direct care for a confirmed case in ASU hospital/clinic | |||||

| No | 1486 (65.1) | 71/37011 | 0.19% | Ref | |

| Yes | 796 (34.9) | 29/11735 | 0.25% | 1.06 (0.66–1.72) | 0.805 |

| Face-to-face interaction within 2 meters with a confirmed case in ASU hospital/clinic | |||||

| No | 1429 (62.6) | 70/34508 | 0.20% | Ref | |

| Yes | 853 (37.4) | 30/14238 | 0.21% | 0.88 (0.55–1.38) | 0.569 |

| Duration of contact with a confirmed case in ASU hospital/clinic | |||||

| n = 853 | n = 30 | ||||

| Less than 5 min | 166 (19.5) | 2/2928 | 0.07% | Ref | |

| 5–15 min | 290 (34.0) | 6/4866 | 0.12% | 1.80 (0.36–8.92) | 0.472 |

| More than 15 min | 397 (46.5) | 22/6444 | 0.34% | 4.98 (1.17–21.20) | 0.030 |

| Self-reported symptoms since baseline screening | |||||

| No | 1596 (69.9) | 64/35020 | 0.18% | Ref | |

| Yes | 686 (30.1) | 36/13726 | 0.26% | 1.35 (0.90–2.04) | 0.149 |

| Self-reported symptoms severity | n = 686 | n = 36 | |||

| Mild | 375 (54.7) | 17/7535 | 0.23% | Ref | |

| Moderate | 255 (37.2) | 16/5055 | 0.32% | 1.51 (0.76–3.00) | 0.236 |

| Severe | 56 (8.2) | 3/1136 | 0.26% | 1.51 (0.44–5.18) | 0.516 |

Hazard ratio (95% CI) were calculated using Cox regression

Figure 2.

Symptoms at baseline and follow-up among symptomatic health care workers

Overall, HCWs reported contact with a confirmed case more frequently at follow-up (1131/2282, 49.6%) than at baseline (1098/4040, 27.2%) A higher proportion of exposures at home/residential area (5/39, 12.8% vs 2/68, 2.9%) and providing direct care to a confirmed case (29/100, 29.0% vs 22/170, 12.9%) were observed among seroconverters at follow-up than among infected HCWs at baseline (Supplementary Table 2).

In the bivariate analysis, a higher risk of seroconversion was associated with the following factors: older age, female gender, marriage, lower level of education, working as a nurse or non-clinical care, presence of a pre-existing medical condition, exposure to a confirmed case at home/residential area (rather than the history of exposure per se), and a duration of contact >15 min with a confirmed case during health care provision ( Tables 1, 2 ). The pre-existing medical conditions that were associated with a higher risk of seroconversion were diabetes, chronic kidney disease, and pregnancy (Supplementary Table 3). Seroconversion risk was not associated with the history of contact with a confirmed case, provision of direct health care to a confirmed case, interaction with a confirmed case within 2 m, being symptomatic, or severity of symptoms ( Tables 1,2 ). When analyzed separately, the following symptoms were associated with a higher risk of seroconversion: fever <38 °C, muscle pain, joint pain, sneezing, shortness of breath, other respiratory symptoms, loss of appetite, change/loss of taste, change/loss of smell, and conjunctivitis (Supplementary Table 4).

In the multivariable Cox proportional hazards model, the risk of seroconversion among HCWs of older age was double to triple the risk of those aged 18-29 years. HCWs with lower educational levels were also at about double or triple the risk of seroconversion compared with HCWs with university or higher education. HCWs who reported contact with a confirmed case within the workplace were at a lower risk of seroconversion compared with those who reported contact at home/residential area (adjusted HR 0.48, 95% CI 0.28-0.82). During health care provision, it is the longer time of exposure rather than the close contact within 2 m that increased the risk of seroconversion. Exposure to a confirmed case for >15 min doubled the risk of seroconversion as compared to exposure for <5 min (adjusted HR 2.20, 95% CI 1.18-4.10). Having chronic kidney disease and being pregnant were independently associated with seroconversion (adjusted HR were 4.42, 95% CI 1.03-18.96 and 3.52, 95% CI 1.05-11.85, respectively). Out of an exhaustive list of symptoms, change/loss of smell was the only symptom that predicted seroconversion (adjusted HR 3.17, 95% CI 1.48-6.78) (Table 3 ).

Table 3.

Multivariable Cox proportional regression analysis of independent determinants of seroconversion in this cohort of health care workers, May-June 2020, Cairo, Egypt (N = 2282).

| β | SE | Adjusted hazard ratio (95% CI)a | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | ||||

| 18–29 | Ref | |||

| 30–39 | 0.945 | 0.333 | 2.57 (1.34–4.94) | 0.005 |

| 40–49 | 0.854 | 0.348 | 2.35 (1.19–4.65) | 0.014 |

| ≥50 | 0.995 | 0.369 | 2.71 (1.31–5.58) | 0.007 |

| Education | ||||

| University or higher | Ref | |||

| Secondary | 0.678 | 0.263 | 1.97 (1.18–3.30) | 0.010 |

| Primary or preparatory | 1.358 | 0.368 | 3.89 (1.89–8.00) | <0.001 |

| Less than primary | 1.187 | 0.443 | 3.28 (1.38–7.81) | 0.007 |

| Location of contact with a confirmed case | ||||

| Home/Residential area | Ref | |||

| Workplace | −0.743 | 0.277 | 0.48 (0.28–0.82) | 0.007 |

| Duration of contact with a confirmed case in ASU hospital/clinic | ||||

| Less than 5 min | Ref | |||

| 5–15 min | 0.092 | 0.474 | 1.10 (0.43–2.77) | 0.846 |

| More than 15 min | 0.786 | 0.319 | 2.20 (1.18–4.10) | 0.014 |

| Pre-existing medical condition | ||||

| Pregnancy | 1.258 | 0.619 | 3.52 (1.05-11.85) | 0.042 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 1.486 | 0.743 | 4.42 (1.03-18.96) | 0.046 |

| Reported symptoms | ||||

| Change/loss of smell | 1.154 | 0.388 | 3.17 (1.48–6.78) | 0.003 |

Variables in the model are: age groups, gender, marital status, job categories, education, place of contact with a confirmed case, duration of contact within the hospital, presence of diabetes, chronic kidney disease, pregnancy, fever <38, muscle pain, joint pain, sneezing, shortness of breathing, other respiratory symptoms, loss of appetite, change/loss of taste, change/loss of smell, and conjunctivitis.

Hazard ratio (95% CI) were calculated using Cox proportional hazard regression model.

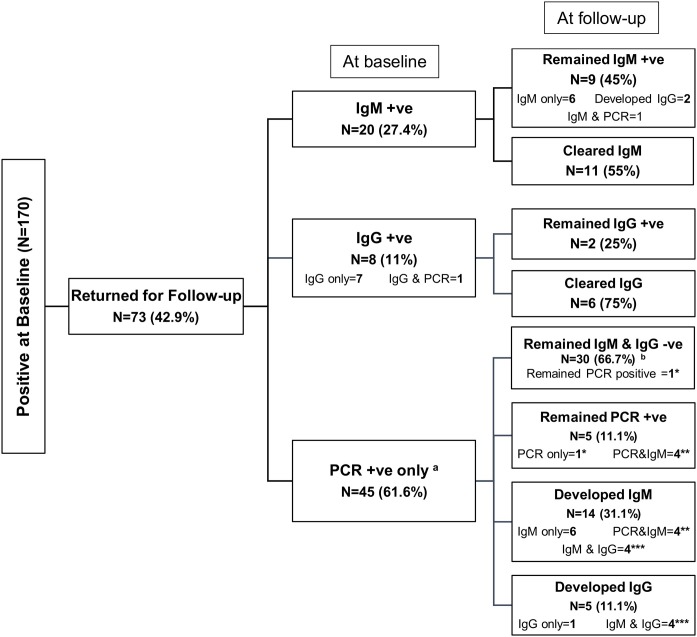

Apart from this follow-up group of HCWs (n = 2282) who tested negative for all 3 tests (IgM, IgG, and PCR) at baseline, 73/170 (42.9%) participants who tested positive for 1 or more of these 3 tests at baseline returned for follow-up. Details of their baseline and follow-up test results are described in Figure 3 and Supplementary Fig. 1. Notably, 30/45 (66.7%) who were PCR-positive only at baseline did not develop antibodies ( Figure 3, Supplementary Fig. 1). The median follow-up period for this group was 26 days (IQR 25-29).

Figure 3.

Follow-up test results of the 170 health care workers who were infected at baseline

Note: a Numbers do not add to 100% at follow-up because of the overlap between groups. Groups with equal number of asterisks are the same cases. b PCR test was not done for 29/30 in this group.

Discussion

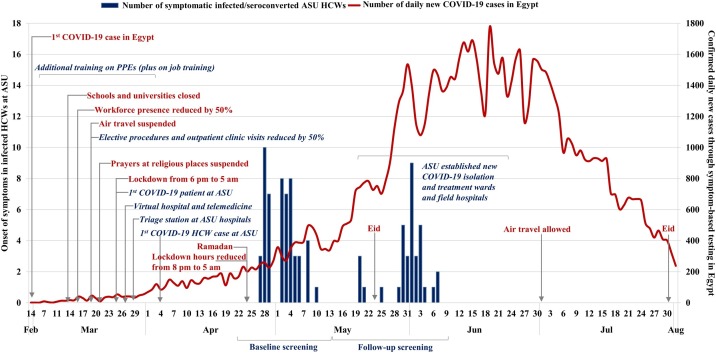

The incidence of seroconversion for SARS-Co-V2 in this HCW cohort was 4.4% (5.3% in symptomatic and 4.0% in asymptomatic HCWs) using rapid serological IgM and IgG tests among those who tested negative (IgM, IgG, and PCR) for SARS-Co-V2 at baseline and returned after 3 weeks for follow-up screening. Seropositivity at follow-up (100/2282, 4.4%) was three-fold the seroprevalence observed at baseline (53/4040, 1.3%). During the follow-up phase, cumulative infections in Egypt have also increased by a similar rate, approximately tripling from 10 829 to 38 284 cases (Ministry of Health and Population, 2020). This follow-up phase took place from 14 May to 10 June 2020 and ended just 10 days before the peak of the first wave. The highest number of daily cases (1774) detected through the national symptom-based PCR testing was recorded on 20 June. After that point, the daily number of cases in Egypt started to decline reaching the rate detected at the launch of baseline screening about 6 weeks later ( Figure 4 ). The same mitigation measures adopted at ASU Hospitals and nationally continued during the follow-up phase. This suggests that infections among HCWs might continue to reflect community rather than nosocomial transmission during the first wave of the COVID-19 epidemic in Egypt.

Figure 4.

Number of infected/seroconverted healthcare workers (HCWs) at baseline and follow up screening in Ain Shams University (ASU) hospitals or medical centers by date of onset of symptoms (bar chart, left y-axis) and daily confirmed COVID-19 cases detected through symptomatic-based testing in Egypt (line graph, right y-axis). The mitigation measures and remarkable events are shown at the national level (red color, non-italic) and at ASU level (blue color, italic).

Approximately two-thirds of the seroconversions in the current study were silent. Asymptomatic infections were also high (68.2%) in this HCW cohort at baseline (Mostafa et al., 2020). Similarly, 6/9 (67%) of the quarantined diamond cruise ship infected passengers remained asymptomatic for 14 days, although they seroconverted and had a high viral load (Hung et al., 2020). Subclinical seroconversion has been reported after 3 weeks among 11/25 (44.0%) asymptomatic HCWs in a pediatric dialysis unit in Indiana, USA; 1 HCW seroconverted on day 21 despite 3 negative PCR test results (Hains et al., 2020). In Norway, serology testing of household members 6 weeks after the index case had a positive PCR test revealed that detecting seroconversion might more accurately identify spread in households than intermittent PCR testing (Cox et al., 2020). These findings reinforce the need for expanding regular universal testing using a combination of PCR and serology in finding cases and tracing contacts, particularly in settings with high rates of asymptomatic infections, to enable prompt isolation and management.

Consistent with our baseline screening findings, (Mostafa et al., 2020) most seroconverted HCWs were nurses (54/100, 54.0%), however, being a nurse was not an independent determinant of seroconversion. Also, more infected HCWs providing non-clinical care tested positive at follow-up (33.0%) than at baseline (16.5%); HCWs’ exposure to COVID-19 patients through community transmission during the follow-up phase when cases were soaring in Egypt may be a plausible explanation for the increased proportion of positive tests among these HCW groups. A meta-analysis of COVID-19 in HCWs reported that those working in hospital non-emergency wards and nurses were the most commonly infected personnel (Gómez-Ochoa et al., 2020). Among this Egyptian HCW cohort, reporting exposure to a confirmed case doubled from a quarter at baseline to half of the overall participants at follow-up. However, among the infected HCWs, the proportion reporting contact with a confirmed case remained the same (about two-fifths).

Nosocomial exposure does not seem to be associated with seroconversion in this Egyptian HCW cohort because two-thirds of those who seroconverted did not report any obvious epidemiological link with a confirmed case. The incidence of seroconversion among HCWs reporting household exposure was five-fold that reported from exposure at the workplace. However, among a cohort of patient-facing HCWs in London, UK, a much higher seroprevalence (25%) at enrolment and seroconversion rate (20%) within 1 month of follow-up were reported with a peak of HCW cases between 30 March and 5 April — a rate at least twice that of the general population, (Houlihan et al., 2020) indicating the possibility of nosocomial rather than community transmission at that stage of the epidemic in London. Nguyen et al also reported that the highest infection rates among their UK HCW cohort study were around London and the Midlands (Nguyen et al., 2020). The difference in the magnitude of infections among the UK and the Egyptian HCW cohorts may depend on the coincidence of study timeframes and the epidemic curves in the 2 countries.

A weak or even lack of seroconversion after initial PCR positivity was reported among some COVID-19 patients during variable periods of follow-up, leaving these individuals susceptible to infection or relapse (Papachristodoulou et al. 2020). For example, 22% of 27 patients did not develop a serologic response after 60 days of follow-up in Germany (Fill Malfertheiner et al., 2020); 20% of 173 Chinese patients did not develop IgG after 2 weeks of onset (Zhao et al., 2020); 6% did not show any antibody response 2 weeks after hospital discharge and 30% of 175 patients showed very low neutralizing antibody titers in Shanghai, China (Wu et al., 2020); and 1 of 14 (7%) HCWs had not seroconverted after 17 days of follow-up in the UK (Houlihan et al., 2020). Among this Egyptian HCW cohort, 66.7% of 45 seronegative HCWs who tested PCR-positive only at baseline did not seroconvert after 3 weeks of follow-up. Furthermore, there was weak IgG seroconversion among the seropositive group at baseline after 3 weeks of follow-up: only 2/20 (10.0%) developed IgG, 11/20 (55.0%) cleared IgM without developing IgG, and 6/8 (75.0%) cleared IgG antibodies. However, the sensitivity of the rapid serological test used in this study was low (83.3%), thus high false negatives rate may have been encountered. The identification of false-negative results among HCWs and the current variation in performance of point-of-care serological assays necessitates caution in interpreting IgG results (Pallett et al., 2020). Per 1000 tested, Deeks et al. assumed that if the sensitivity of IgG/IgM was 91.4% at 15 to 21 days, at a prevalence of 5%, 4 cases (3 to 7) would be missed (Deeks et al., 2020). Despite this concern, our findings have important implications for the level of long-term immunity and vaccine development in settings with predominantly asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infections.

HCWs ≥50 years old had approximately a three-fold risk of seroconversion compared with HCWs of younger age groups. Older HCWs were reported to have higher IgG titers in an Italian HCW cohort (Calcagno et al., 2020) and a higher seroprevalence in a study in Idaho, USA (Bryan et al., 2020). Having chronic kidney disease was associated with a four-fold risk of seroconversion among HCWs in the current study. Being older than 40 years and having chronic kidney disease were independent determinants of having a positive SARS-CoV-2 test among 587 primary care patients in the UK (de Lusignan et al., 2020). Pregnant HCWs were at a four-fold risk of seroconversion in the current study compared to non-pregnant HCWs. Pregnant women in the USA were reported to be at risk for severe COVID-19 illness and its complications (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2020b). Change/loss of smell independently predicted seroconversion among HCWs in this study at follow-up and seropositivity at baseline. Similarly, recent loss of smell was associated with a three-fold increase in the risk of seropositivity for SARS-CoV-2 in a community-based cohort in the UK (Makaronidis et al., 2020). A meta-analysis reported that olfactory dysfunctions were found in 41% of 8438 COVID-19 patients from 13 countries (Agyeman et al., 2020); being a highly specific symptom of COVID-19, it could guide early testing and case isolation.

Limitations and challenges

Approximately two-fifths of the HCWs in this longitudinal study were lost to follow-up and some did not return for their PCR appointments. HCWs were redistributed among newly established isolation wards/hospitals during the follow-up phase that preceded the peak of the epidemic in Egypt, therefore, many were not able to return for follow-up. Also, some HCWs were quarantined or self-isolating. Second, in contrast to the baseline phase, PCR testing was not conducted universally for HCWs at follow-up; instead, it was restricted to those with positive serology. This decision was taken as a precautionary measure to preserve the PCR stock and meet the expected increase in testing needs, given the foreseen rise in hospital admissions at that stage of the epidemic in Egypt. As a result, some infected HCWs who were in the early stage of infection may have been missed using serological tests alone. PCR is costly and requires skill in sample collection. These challenges may affect the quality and sustainability for universal regular testing of HCWs. To avoid critical delays in diagnosis, management and quarantine, using serological tests (in isolation or combined with PCR when possible) — especially rapid point-of-care tests that are continuously being developed with higher accuracy to meet the parallel development in vaccines (Pallett et al., 2020, Pickering et al., 2020, Amanat et al., 2020)— may be a more reasonable assay choice for high-throughput use, less workload and a faster turnaround time in resource-limited settings. Third, despite the published study reports addressing the performance of the used serological assay testing kits (Zhang and Zheng, May 21, 2020; Artron Laboratories, Inc. Oct. 28, 2020), the commercial manufacturer voluntarily withdraw the test from the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) notification list of commercial manufacturers distributing serology test kits under the Policy for Coronavirus Disease-2019 Tests and was included in the FDA removal list on 25 May 2020. This action may be due to not providing the necessary documentation in a timely manner, as could be concluded from the dates of report publishing. The two reports documented sensitivity of 94.4% and 93.3%; and specificity of 98.2% and 100% (Zhang and Zheng, May 21, 2020; Artron Laboratories, Inc. Oct. 28, 2020). Based on the evidence we have; the testing kits used have an acceptable level of validity that most probably did not jeopardize the validity of our study results.

Conclusions

The incidence of seroconversion in this cohort of HCWs was 4.4%. More than two-thirds of the seroconverted HCWs were asymptomatic. Seropositivity at follow-up was triple that observed at baseline, however, HCWs’ exposures outside the workplace were associated with a higher risk of seroconversion. Cumulative infections in Egypt increased by a similar rate during the follow-up phase, suggesting infections among HCWs continue to reflect community rather than nosocomial transmission during the first wave of the COVID-19 epidemic in Egypt. The high rate of asymptomatic infections among this cohort of HCWs reinforces the need for expanding universal regular testing, which is particularly important as countries are witnessing the second wave of SARS-CoV-2 infection. However, evaluating the feasibility for sustained implementation of such programs and their effectiveness in various resource-limited settings is necessary.

Declaration of Interest

None

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author contributions

Aya Mostafa conceptualized and visualized the study, planned and designed the study, performed literature search, developed the study tools, planned the study workflow, supervised the study, coordinated and monitored implementation, lead data management and statistical data analysis, jointly prepared the figures, interpreted the data, wrote the first draft of the manuscript, and critically reviewed the manuscript.

Sahar Kandil participated in the study design, performed literature search, advised on the study tools, conducted the statistical analysis, prepared the tables and jointly prepared the figures, participated in writing the second draft of the manuscript, and critically reviewed the manuscript.

Manal H El-Sayed supervised the study planning and conduction, and critically reviewed the manuscript.

Supervision and logistics (Mahmoud El-Meteini, Ayman Saleh and Ali Elanwar).

Supervision (Ashraf Omar).

Coordination of implementation (Ossama Mansour and Samia Girgis).

Laboratory analysis (Hala Hafez, Saly Saber, Hoda Ezzelarab, Marwa Ramadan, Eman Algohary).

Fatma SE Ebeid participated in monitoring implementation.

Mostafa Yosef adapted the study tool for online data collection and participated in data management. Implementation of screening (Gehan Fahmy, Iman Afifi, Fatmaelzahra Hassan, Shaimaa Elsayed, Amira Reda, Doaa Fattuh, Asmaa Mahmoud, Amany Mansour, Moshira Sabry, Petra Habeb).

Footnotes

Supplementary material related to this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2021.01.037.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is Supplementary data to this article:

References

- Agyeman A.A., Chin K.L., Landersdorfer C.B., Liew D., Ofori-Asenso R. Smell and Taste Dysfunction in Patients With COVID-19: a Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Mayo Clin Proc. 2020;95(8):1621–1631. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2020.05.030. Aug. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alarabiya News . Syndicate: 3576 cases and 188 deaths of Corona among Egyptian physicians. Alarabiya News; 2020. Alarabiya News, 19 October.https://www.alarabiya.net/ar/arab-and-world/egypt/2020/10/19/ (accessed 07 November 2020) [Google Scholar]

- Amanat F., Stadlbauer D., Strohmeier S., Nguyen T.H.O., Chromikova V., McMahon M. A serological assay to detect SARS-CoV-2 seroconversion in humans. Nat Med. 2020;26(7):1033–1036. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0913-5. Jul. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryan A., Pepper G., Wener M.H., Fink S.L., Morishima C., Chaudhary A. Performance Characteristics of the Abbott Architect SARS-CoV-2 IgG Assay and Seroprevalence in Boise, Idaho. J Clin Microbiol. 2020;58(8) doi: 10.1128/JCM.00941-20. Jul 23e00941-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calcagno A., Ghisetti V., Emanuele T., Trunifo M., Faraoni S., Boglione L. Risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection in healthcare workers, Turin, Italy. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020;27(1) doi: 10.3201/eid2701.203027. Jan. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . 2020. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). Laboratories. Resources for Labs. Interim Guidelines for Collecting, Handling, and Testing Clinical Specimens for COVID-19. https://www.cdc.gov/corona virus/2019-ncov/lab/guidelines-clinical-specimens.html (accessed 9 April 2020) [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . 2020. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). Cases, data & surveillance. Data on COVID-19 during Pregnancy: Severity of Maternal Illness. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/cases-updates/special-populations/pregnancy-data-on-covid-19.html (accessed 14 November 2020) [Google Scholar]

- Cox R.J., Brokstad K.A., Krammer F., Langeland N. Bergen COVID-19 Research Group. Seroconversion in household members of COVID-19 outpatients. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30466-7. Jun 15:S1473-3099(20)30466-7Epub ahead of print. Erratum in: Lancet Infect Dis 2020 Sep;20(9):e215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Lusignan S., Dorward J., Correa A., Jones N., Akinyemi O., Amirthalingam G. Risk factors for SARSCoV-2 among patients in the Oxford Royal College of General Practitioners Research and Surveillance Centre primary care network: a cross-sectional study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20(9):1034–1042. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30371-6. Sep. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deeks J.J., Dinnes J., Takwoingi Y., Davenport C., Spijker R., Taylor-Phillips S. Antibody tests for identification of current and past infection with SARS-CoV-2. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;6(6) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD013652. Jun 25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fill Malfertheiner S., Brandstetter S., Roth S., Harner S., Buntrock-Döpke H., Toncheva A.A. Immune response to SARS-CoV-2 in health care workers following a COVID-19 outbreak: A prospective longitudinal study. J Clin Virol. 2020;130 doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2020.104575. Sep. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gómez-Ochoa S.A., Franco O.H., Rojas L.Z., Raguindin P.F., Roa-Siaz Z.M., Wyssman B.M. COVID-19 in Healthcare Workers: A Living Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Prevalence, Risk Factors, Clinical Characteristics, and Outcomes. Am J Epidemiol. 2020 doi: 10.1093/aje/kwaa191. Sep 1:kwaa191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hains D.S., Schwaderer A.L., Carroll A.E., Starr M.C., Wilson A.C., Amanat F. Asymptomatic Seroconversion of Immunoglobulins to SARS-CoV-2 in a Pediatric Dialysis Unit. JAMA. 2020;323(23):2424–2425. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.8438. Jun 16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houlihan C.F., Vora N., Byrne T., Lewer D., Kelly G., Heaney J. Pandemic peak SARS-CoV-2 infection and seroconversion rates in London frontline health-care workers. Lancet. 2020;396(10246):e6–e7. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31484-7. Jul 25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hung I.F., Cheng V.C., Li X., Tam A.M., Hung D.L., Chiu K.H.Y. SARS-CoV-2 shedding and seroconversion among passengers quarantined after disembarking a cruise ship: a case series. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20(9):1051–1060. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30364-9. Sep. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johns Hopkins University of Medicine . World map; 2020. Coronavirus Resource Center.https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html [Google Scholar]

- Lassaunière R., Frische A., Harboe Z.B., Nielsen A.C.Y., Fomsgaard A., Krogfelt K.A. Evaluation of Nine Commercial SARS-CoV-2 Immunoassays. medRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.04.09.20056325. Posted April 10. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Long Q.X., Liu B.Z., Deng H.J., Wu G.C., Deng K., Chen Y.K. Antibody responses to SARS-CoV-2 in patients with COVID-19. Nat Med. 2020;26(6):845–848. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0897-1. Jun. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makaronidis J., Mok J., Balogun N., Magee C.G., Omar R.Z., Carnemolla A. Seroprevalence of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in people with an acute loss in their sense of smell and/or taste in a community-based population in London, UK: An observational cohort study. PLoS Med. 2020;17(10) doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003358. Oct 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandić-Rajčević S., Masci F., Crespi E., Franchetti S., Longo A., Bollina I. Contact tracing and isolation of asymptomatic spreaders to successfully control the COVID-19 epidemic among healthcare workers in Milan (Italy) medRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.05.03.20082818. Preprint May 08. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health and Population, Egypt . 2020. COVID-19 report.https://www.care.gov.eg/EgyptCare/index.aspx [Google Scholar]

- Mostafa A., Kandil S., El-Sayed M.H., Girgis S., Hafez H., Yosef M. Universal COVID-19 screening of 4040 health care workers in a resource-limited setting: an Egyptian pilot model in a university with 12 public hospitals and medical centers. Int J Epidemiol. 2020 doi: 10.1093/ije/dyaa173. Oct 23:dyaa173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen L.H., Drew D.A., Graham M.S., Joshi A.D., Guo C., Ma W. Risk of COVID-19 among front-line health-care workers and the general community: a prospective cohort study. Lancet Public Health. 2020;5(9):e475–e483. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30164-X. Sep. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pallett S.J.C., Rayment M., Patel A., Fitzgerald-Smith S.A.M., Denny S.J., Charani E. Point-of-care serological assays for delayed SARS-CoV-2 case identification among health-care workers in the UK: a prospective multicentre cohort study. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8(9):885–894. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30315-5. Sep Erratum in: Lancet Respir Med. 2020 Jul 30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papachristodoulou E., Kakoullis L., Parperis K., Panos G. Long-term and herd immunity against SARS-CoV-2: implications from current and past knowledge. Pathog Dis. 2020;78(3) doi: 10.1093/femspd/ftaa025. Apr 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pickering S., Betancor G., Galão R.P., Merrick B., Signell A.W., Wilson H.D. Comparative assessment of multiple COVID-19 serological technologies supports continued evaluation of point-of-care lateral flow assays in hospital and community healthcare settings. PLoS Pathog. 2020;16(9) doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1008817. Sep 24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seow J., Graham C., Merrick B., Acros S., Pickering S., Steel K.J.A. Longitudinal observation and decline of neutralizing antibody responses in the three months following SARS-CoV-2 infection in humans. Nat Microbiol. 2020;5(12):1598–1607. doi: 10.1038/s41564-020-00813-8. Dec. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . World Health Organization; 2020. Population-based age-stratified seroepidemiological investigation protocol for COVID-19 virus infection, 17 March 2020.https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/331656 [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . 2020. Risk Assessment and Management of Exposure of Health Care Workers in the Context of COVID-19. Interim guidance 2020b.https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/331496/WHO-2019-nCov-HCW_risk_assessment-2020.2-eng.pdf (accessed 09 April 2020) [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . 2020. Protocol for Assessment of Potential Risk Factors for 2019-novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV) Infection among Health Care Workers in a Health Care Setting 2020c.https://www.who.int/publications-detail/protocol-for-assessment-of-potential-risk-factors-for-2019-novel-coronavirus-(2019-ncov)-infection-among-health-care-workers-in-a-healthcare-setting [Google Scholar]

- Wu F., Liu M., Wang A., Lu L., Wang Q., Gu C. Evaluating the Association of Clinical Characteristics With Neutralizing Antibody Levels in Patients Who Have Recovered From Mild COVID-19 in Shanghai, China. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(10):1356–1362. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.4616. Oct 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang and Zheng Artron Laboratories Inc . 2020. R & D Department Quality control department. IgM/IgG Antibody Test Diagnostic Sensitivity and Specificity Study Report May 21. COVID-19. http://www.cemagcare.com/wp content/uploads/2020/07/Rapport_de_performances_test_de_detection_covid19_IgM_IgG_Artr n.pdf. (accessed 31 December 2020) [Google Scholar]

- Zhao J., Yuan Q., Wang H., Liu W., Liao X., Su Y. Antibody responses to SARS-CoV-2 in patients of novel coronavirus disease 2019. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71(16):2027–2034. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa344. Nov 19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.