Abstract

DNA ligase 1 (LIG1, Cdc9 in yeast) finalizes eukaryotic nuclear DNA replication by sealing Okazaki fragments using DNA end-joining reactions that strongly discriminate against incorrectly paired DNA substrates. Whether intrinsic ligation fidelity contributes to the accuracy of replication of the nuclear genome is unknown. Here, we show that an engineered low-fidelity LIG1Cdc9 variant confers a novel mutator phenotype in yeast typified by the accumulation of single base insertion mutations in homonucleotide runs. The rate at which these additions are generated increases upon concomitant inactivation of DNA mismatch repair, or by inactivation of the Fen1Rad27 Okazaki fragment maturation (OFM) nuclease. Biochemical and structural data establish that LIG1Cdc9 normally avoids erroneous ligation of DNA polymerase slippage products, and this protection is compromised by mutation of a LIG1Cdc9 high-fidelity metal binding site. Collectively, our data indicate that high-fidelity DNA ligation is required to prevent insertion mutations, and that this may be particularly critical following strand displacement synthesis during the completion of OFM.

Subject terms: DNA replication, X-ray crystallography

DNA ligase 1 (LIG1) finalizes eukaryotic nuclear DNA synthesis by sealing Okazaki fragments using DNA end-joining reactions. Here the authors, by studying an engineered low-fidelity LIG1, reveal that LIG1 is a highly accurate DNA ligase in vivo.

Introduction

The most abundant DNA transaction in eukaryotic cells that affects the fidelity of nuclear DNA replication is the nucleotide selectivity of DNA polymerases (Pols) α, δ, and ε during incorporation into a growing DNA chain during leading and lagging strand synthesis1. Second only to this selectivity is proper Okazaki fragment maturation (OFM) of lagging strand DNA fragments, an event that occurs thousands to millions of times during each DNA replication cycle in eukaryotic cells2–4. Okazaki fragment processing involves replacement of RNA–DNA primers made by Pol α-primase. This occurs by nick-translation/strand displacement DNA synthesis catalyzed by Pol δ to create DNA substrates that are cleaved by Fen1 and/or by DNA2 nucleases5–10. The resulting nick is then sealed by DNA ligase 1 (LIG1) to finalize synthesis of the DNA strand. Successful OFM produces undamaged DNA ends that are sealed by LIG1 to ensure faithful DNA replication and avoid genome instability in the form of DNA breaks, deletions, and duplications.

Among four known eukaryotic DNA ligases11–13, LIG1 is the enzyme involved in OFM. A recently published high-resolution structure of LIG1 bound to a nicked DNA duplex reveals that it employs a Mg2+-reinforced DNA-binding mode to promote high-fidelity DNA ligation in vitro14. The interface formed between LIG1, Mg2+, and the DNA substrate is critical for ensuring that DNA nicks containing damaged or mutagenic ends are not sealed, thereby promoting high-fidelity DNA ligation. Mutation of two highly conserved Mg2+-binding glutamic acid residues in LIG1 that form this interface to alanines reduces enzyme accuracy but does not impact enzymatic turnover, thereby facilitating mutagenic ligation14. However, despite the importance of DNA ligation reactions for life, whether high-fidelity DNA ligation is required for faithful DNA replication in vivo remains unknown.

Here we demonstrate that LIG1 is a highly accurate DNA ligase in vivo. Expression of a Cdc9EE/AA variant in yeast that compromises ligation fidelity results in a high rate of +1 base insertion events in short homonucleotide runs. These mutagenic events are exacerbated upon loss of DNA mismatch repair (MMR) or loss of Fen1-dependent nuclease activity, demonstrating that highly accurate DNA ligation is a previously underappreciated critical determinant of faithful replication of the nuclear genome. Biochemical and structural dissection of the mutagenic ligation reaction performed by the low-fidelity mutant DNA ligase provides a molecular framework for this insertion mutagenesis and solidifies the importance of accurate DNA ligation during DNA synthesis.

Results

The in vivo mutagenic consequences of low-fidelity DNA ligation

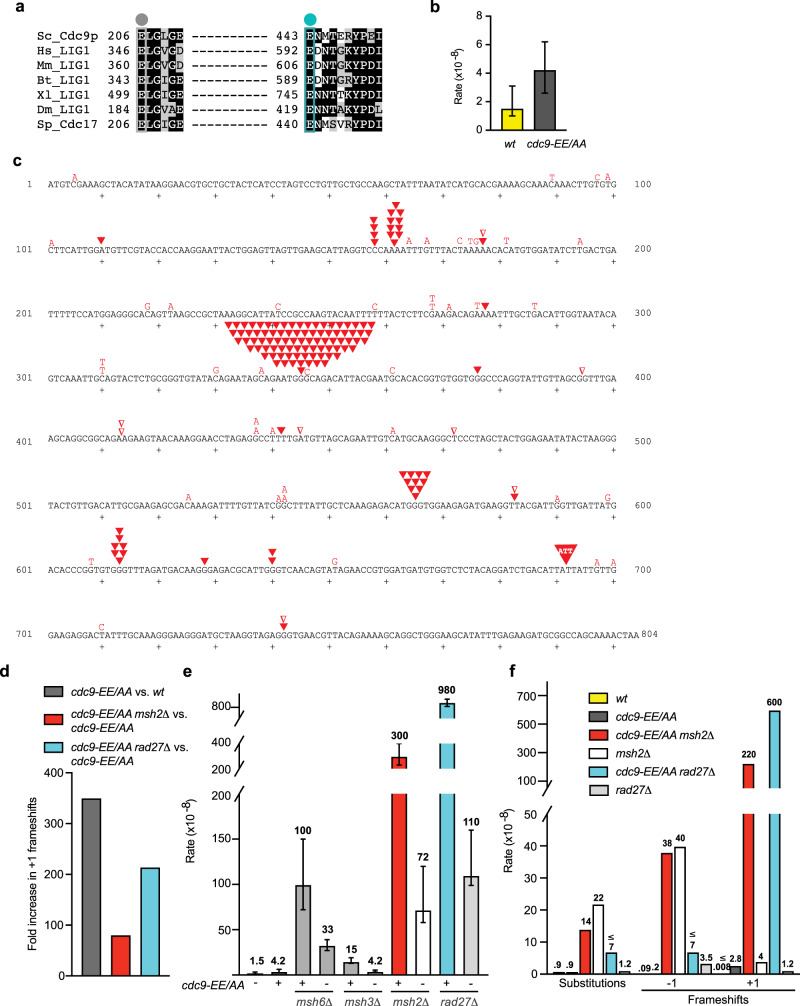

To test whether high-fidelity ligation is critical for genome maintenance in vivo, we constructed a low-fidelity ligation yeast strain containing alanine substitutions of the conserved Glu206 and Glu443 residues in the CDC9 gene that encodes Saccharomyces cerevisiae DNA ligase 1 (cdc9-EE/AA) (Fig. 1a). Tetrad dissection reveals that spore colonies harboring the mutant cdc9-EE/AA ligase germinated and grew to a colony size similar to a wild-type control (Supplementary Fig. 1). Using the URA3 forward mutation reporter assay, we measured spontaneous mutation rates and specificity in the cdc9-EE/AA mutant. An overall increase (2.8-fold) in mutation rate compared to a wild-type (wt) yeast strain (Fig. 1b) was driven almost entirely by a significant number of single base addition mutations that were observed (Fig. 1c). These single base insertions are within short homonucleotide runs, predominantly in runs of G–C base pairs but occasionally in runs of A–T base pairs (Fig. 1c), suggesting that formation of the +1 additions likely involves DNA strand slippage. The specificity is also intriguing in that the single base additions observed here, whose production requires an extra base in the newly synthesized strand, are much more prevalent than are the single base deletions that predominate in many other studies15–21, and require an extra base in the template strand to generate a misaligned intermediate with an unpaired nucleotide22,23. Moreover, the observed insertions are spaced intermittently, but non-randomly, throughout the URA3 reporter gene. Thus, despite the presence of homonucleotide runs at many locations in URA3, the addition mutations are primarily observed at locations separated by approximately 200 base pairs (Fig. 1c, positions 157, 344, 564, for example). Interestingly, high-resolution mapping of Okazaki fragments from S. cerevisiae showed that their size is roughly consistent with the nucleosome repeat, which averages 165 bp in size24,25, and DNA ligase 1 is able to efficiently seal a nick on a nucleosomal substrate26. The mutation rates for +1 insertions are >300-fold increased relative to wt for cdc9-EE/AA (Fig. 1d). In marked contrast, single base substitutions and deletion mutations are infrequent in cdc9-EE/AA (Fig. 1c, f), as are mutation events involving multiple bases (Supplementary Table 2).

Fig. 1. Mutational analysis of the low-fidelity Cdc9-EE/AA variant demonstrates the importance of Ligase 1 in preventing +1 insertion mutations during replication.

a Sequence alignment of the strictly conserved LIG1 HiFi glutamate residues in eukaryotic homologs. Sc Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Hs Homo sapiens, Mm Mus musculus, Bt Bacillus thuringiensis, Xl Xenopus laevis, Dm Drosophila melanogaster, Sp Schizosaccharomyces pombe. b Overall spontaneous mutation rates for yeast strains expressing either wild-type Cdc9 or the Cdc9-EE/AA variant were determined by fluctuation analysis using a URA3 reporter assay (biological replicates: n = 34 for wt; n = 52 for cdc9-EE/AA). The rate of mutation conferring resistance to 5-FOA was determined as ura3 mutants are resistant to 5-FOA. The median rate ± the 95% confidence interval is displayed. c The coding strand of the 804-bp URA3 gene is shown. Small sequence changes (≤3 bp) observed in independent ura3 mutants are depicted in red for the cdc9-EE/AA strain (n = 189). Letters indicate single base substitutions, inverted closed triangles indicate +1 frameshifts, and inverted open triangles indicate −1 frameshifts. Larger sequence changes observed are listed in Supplementary Table 2. d The fold increases in the +1 frameshift mutation rate for the indicated comparisons were calculated using the specific mutation rates displayed in f. e Overall spontaneous mutation rates for the wt or cdc9-EE/AA strains +/− MMR or RAD27 are displayed as in b (biological replicates: n = 39 for msh6Δ; n = 33 for cdc9-EE/AA msh6Δ; n = 22 for msh3Δ; n = 48 for cdc9-EE/AA msh3Δ; n = 47 for msh2Δ; n = 81 for cdc9-EE/AA msh2Δ; n = 97 for rad27Δ; n = 261 for cdc9-EE/AAA rad27Δ). f The specific mutation rates of single base substitutions, −1 frameshifts, and +1 frameshifts were calculated as the proportion of each type of event among the total mutants sequenced (Supplementary Table 3), multiplied by the overall mutation rate (e). Specific mutation rate values are indicated above each bar, and a ≤ symbol indicates that there were 0 events observed. The sequencing data for wt and msh2Δ is from ref. 52. Source data for panels are provided as a Source data file.

We next examined the role of DNA MMR in correcting these +1 insertion mutations observed in the cdc9-EE/AA mutant by deleting each of the three MSH genes (MSH2, MSH3, or MSH6). Loss of these genes in the low-fidelity ligase mutant had a modest effect on overall mutation rate, with the largest effect observed in the cdc9-EE/AA msh2Δ strain (Fig. 1e). Msh2 is the common component of the MutSα (Msh2-Msh6) and the MutSβ (Msh2-Msh3) heterodimers that initiate MMR, and therefore loss of MSH2 eliminates MMR-dependent repair of single base substitutions, as well as small and large deletion and insertion mutations20,27. Here we observe a fourfold increase in overall mutation rate when comparing the cdc9-EE/AA msh2Δ double mutant to the msh2Δ strain (Fig. 1e). These mutator effects encouraged us to sequence ura3 mutants to determine whether specific classes of mutations are affected in the absence of MMR.

The +1 insertion rates are further elevated in cdc9-EE/AA MMR-deficient strains, despite cdc9-EE/AA having very little effect on the rate of single base substitutions or deletions when compared to the msh6Δ, msh3Δ, or msh2Δ single mutant strains expressing wild-type CDC9 (Fig. 1f and Supplementary Tables 3 and 4). The relative increase in the +1 insertion rate is greatest in the cdc9-EE/AA msh2∆ mutant strain (Fig. 1d and Supplementary Fig. 2, ~80-fold higher compared to cdc9-EE/AA). The slightly smaller sizes of the cdc9-EE/AA msh2Δ haploid strain colonies, as well as the decreased growth rate and enlarged cells (Supplementary Fig. 1), may be related to the observed high rate of the addition mutations, suggesting that these cdc9-EE/AA msh2∆ mutant cells may have accumulated +1 mutations in genes that are important for promoting normal cell growth and morphology. The +1 mutation rate is also strongly elevated (by 20-fold) in the cdc9-EE/AA msh6∆ mutant and is modestly elevated (by 1.5-fold) in the cdc9-EE/AA msh3∆ mutant when compared to the MMR-proficient cdc9-EE/AA strain (Supplementary Figs. 3 and 4 and Supplementary Tables 3 and 4). Quantitatively, these results are consistent with the interpretation that the Cdc9-dependent +1 mutations result from DNA replication errors, where loss of MSH2 and MSH6 have a much greater effect on formation of single base insertion/deletion (indel) errors than does a mutation in MSH320,28. These facts, and the observation that the insertions occur at widely spaced locations in URA3, despite the presence of homonucleotide runs throughout the gene, are consistent with the role of MMR in reducing the rate of +1 insertions that are ligated during OFM in the low-fidelity cdc9-EE/AA mutant strain.

To further test the hypothesis that DNA ligase 1 performs high-fidelity ligation during replication, we deleted RAD27 in the cdc9-EE/AA strain. RAD27 is the gene encoding the Fen1 endonuclease involved in cleaving the displaced DNA flap generated by Pol δ displacement synthesis during OFM. Like the cdc9-EE/AA msh2∆ double mutant, the cdc9-EE/AA rad27∆ haploid has a reduced spore colony size, a defect in cell growth, and enlarged cell morphology (Supplementary Fig. 1), again suggesting a modest growth disadvantage. The cdc9-EE/AA rad27∆ mutant also has a stronger overall mutator effect than either the cdc9-EE/AA or the rad27∆ single mutants (Fig. 1e). More importantly, sequence analysis of independent ura3 mutants demonstrates that, in addition to the well-known duplications of multiple base pairs seen here (Supplementary Tables 5 and 6) and previously observed in RAD27-deficient strains (Supplementary Table 7)29,30, the cdc9-EE/AA rad27∆ double mutant generates +1 insertions (Supplementary Fig. 5) at a very high rate (Fig. 1f). The rate is elevated 200-fold when compared to the cdc9-EE/AA strain (Fig. 1d) and is synergistic with loss of Fen1-dependent OFM. These +1 mutations are again observed in homonucleotide runs that are non-uniformly distributed throughout the URA3 reporter gene (Supplementary Fig. 5), with some of the +1 insertions occurring in the same homonucleotide runs observed in the MMR-defective strains (Supplementary Figs. 2–4). Others are in different locations, e.g., in runs of T–A base pairs at positions 90–93 and 440–443 (Supplementary Fig. 5). The differences in the specificity of +1 addition mutagenesis in the cdc9-EE/AA mutant lacking either MSH2 or RAD27 may be anticipated by the fact that +1 additions can result from defects in MMR or during OFM when DNA flaps are removed by Rad27, the Dna2 helicase-nuclease, or by both nucleases8,10,31,32.

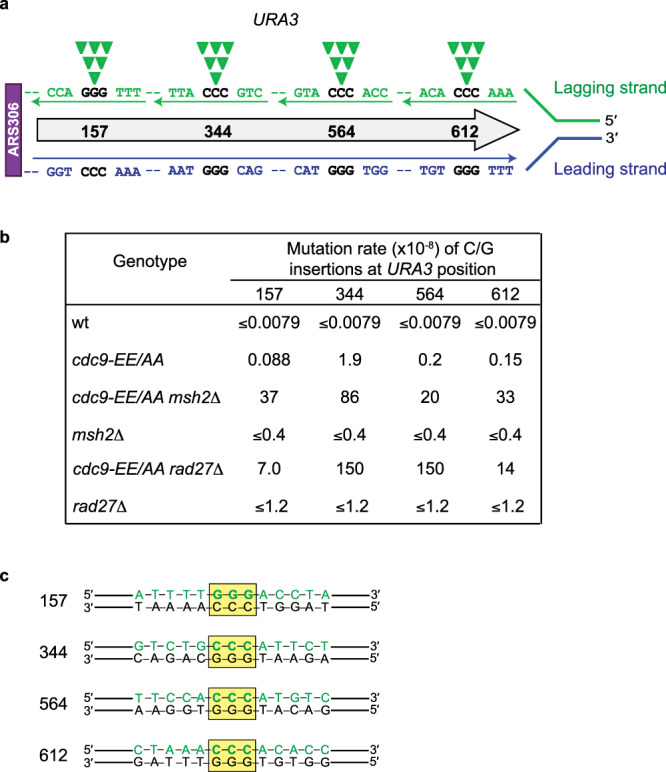

Based on error signatures33,34 and ribonucleotide incorporation35–38, it can be inferred which DNA strand is being synthesized as the lagging strand (in green in Fig. 2a) by Pol δ or the leading strand (in blue) by Pol ε during synthesis of the URA3 reporter in its genomic location adjacent to the closest replication origin, ARS306. These studies were performed using mutator variants of DNA Pols δ and ε that had been biochemically characterized as having specific mutation signatures and ribonucleotide incorporation propensities. The contributions and the sequence contexts for four of the +1 C/G insertion hotspots in URA3 observed in the cdc9-EE/AA mutant are displayed in Fig. 2a. Because of the discontinuous nature of lagging strand synthesis and the fact that DNA ligase 1 completes OFM by joining the DNA fragments, we can infer that it is an extra base incorporated by Pol δ during synthesis of the lagging strand that leads to error-prone ligation and a +1 insertion mutation signature in the cdc9-EE/AA strain. As a result, this would suggest that it is incorporation of an extra G at hotspot 157 or incorporation of an extra C at hotspots 344, 564, and 612 by Pol δ that generates the DNA substrate ligated by the low-fidelity mutant Cdc9 ligase (Fig. 2a). For two of the hotspots, the +1 insertion mutation rates are elevated by 240-fold (position 344) and 25-fold (position 564) when comparing the cdc9-EE/AA mutant to wt (Fig. 2b and Supplementary Table 8). These rates are further elevated in the absence of either MSH2 (45-fold and 100-fold) or RAD27 (79-fold and 750-fold), suggesting that MMR, Fen1, and high-fidelity DNA ligation are critical for preventing +1 insertions at defined genomic positions to maintain genome stability. The DNA sequence surrounding these URA3 hotspots varies (Fig. 2c).

Fig. 2. Analysis of mutational hotspots for +1 insertions in the low-fidelity cdc9-EE/AA strain +/− MSH2 or RAD27.

a A schematic of the URA3 reporter gene located adjacent to the ARS306 replication origin. Displayed is the leading strand DNA sequence synthesized by Pol ε in blue and the lagging strand synthesized by Pol δ in green. The additional C that would be incorporated by Pol δ at three of the mutation hotspots to generate a +1 insertion is indicated by the closed green inverted triangles. b Site-specific rates for +1 G/C insertions at 4 hotspots in the URA3 reporter gene for the wt and cdc9-EE/AA strains +/− MSH2 or RAD27. Rates were calculated as the proportion of each site-specific event among the total mutants sequenced (Supplementary Table 3) multiplied by the overall mutation rate (Fig. 1c). c A depiction of the DNA sequences surrounding four of the sites in URA3 at which the mutation rate of +1 insertions of G/C is the highest. The Pol δ-synthesized lagging strand is shown in green and the location of the homopolymer run in which an extra base would be inserted is highlighted by the yellow box.

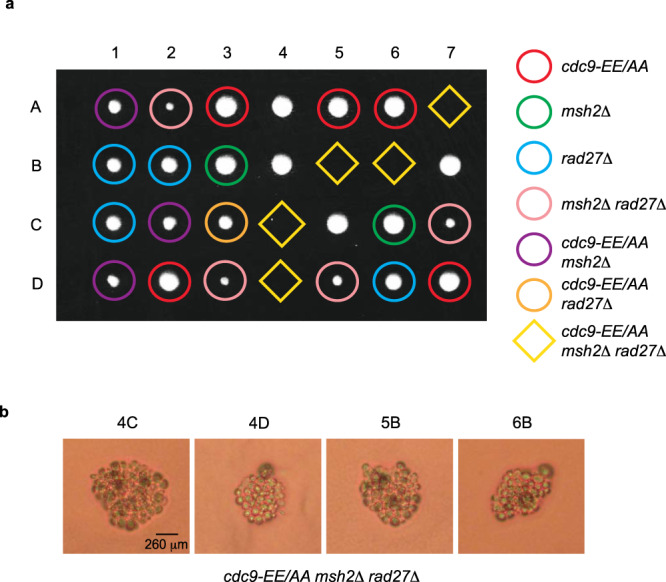

MMR was recently shown to act in an overlapping pathway with Rad27 to correct mutations that arise during OFM39. Therefore, we next tested the importance of high-fidelity ligation in the absence of both RAD27 and MSH2. Tetrad dissection of a heterozygous CDC9/cdc9-EE/AA, MSH2/msh2Δ, and RAD27/rad27Δ diploid strain shows that the cdc9-EE/AA msh2Δ rad27Δ triple mutant haploid strain is inviable (Fig. 3a, yellow diamonds). Microscopic images of the spore colonies reveal that, following germination, the cells go through only a finite number of divisions before arrest (Fig. 3b) and never form colonies large enough to be macroscopically visualized (Fig. 3a). This demonstrates that high-fidelity DNA ligation by Cdc9 is critical for cell viability in the absence of both MMR and Fen1-dependent OFM.

Fig. 3. High-fidelity DNA ligation is required in the absence of both MSH2 and RAD27.

a A diploid yeast strain heterozygous for cdc9-EE/AA, msh2Δ, and rad27Δ was sporulated, dissected, and the haploid spore colonies were genotyped by appropriate marker selection. 1–7 are tetrad dissections and A–D are haploid spore colonies. Plates were imaged after 3 days growth on YPDA at 30 °C. b Microscopic images of the indicated microcolonies taken after 5 days of growth reveals that the cdc9-EE/AA msh2Δ rad27Δ haploid derivatives sporulated but only divided a finite number of times. Thirteen dissections were performed using three independently derived diploid strains and similar results were obtained each time.

Mutagenic ligation of bulged DNA substrates

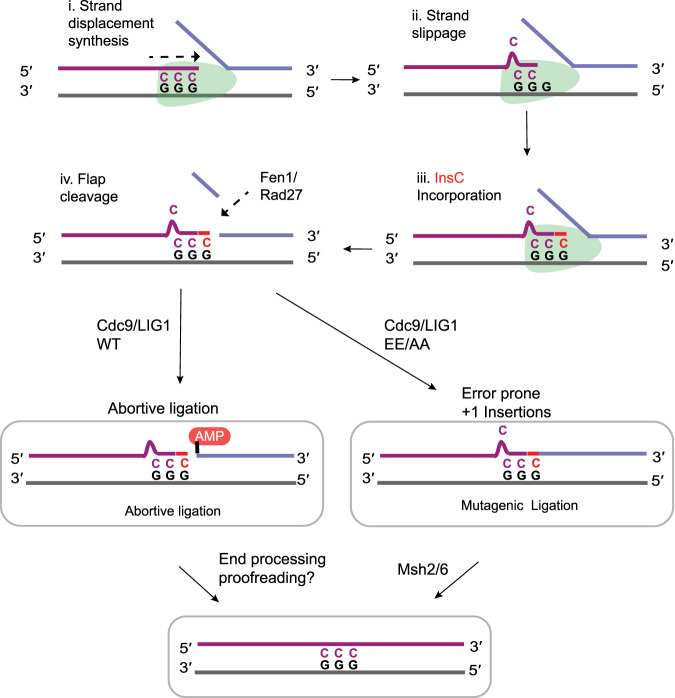

We next probed the biochemical context under which Cdc9 can perform mutagenic ligation on substrates with single-nucleotide insertions. The lagging strand context of the cdc9-EE/AA mutator phenotype suggests that, following strand displacement DNA synthesis templated by triplet homonucleotide repeats (Fig. 4, step i), DNA strand slippage stabilizes a single bulged base (Fig. 4, step ii). DNA Pol extension of a bulged substrate (Fig. 4, step iii) precedes DNA flap maturation (Fig. 4, step iv). Cdc9 engagement of bulged substrates could occur in a variety of registers relative to the Pol misinsertion event, and therefore Cdc9 ligation activity was tested on an array of substrates where the DNA nick was placed at various positions relative to a bulged cytosine base (insC) within the URA3 mutation hotspot sequence context observed in the cdc9-EE/AA strain (Fig. 5a).

Fig. 4. Cdc9 regulates the fidelity of Okazaki fragment maturation.

A model depicts a +1 base insertion mutation during OFM: (i) A DNA polymerase (green) performs strand displacement DNA synthesis templated by a triplet mononucleotide repeat. (ii) DNA strand slippage stabilizes a single bulged base. (iii) Polymerase extension of the bulged base results in a +1 base insertion in the new strand, (iv) Rad27/Fen1 cleaves the DNA flap. High-fidelity Cdc9WT/LIG1WT aborts ligation on the bulged DNA to circumvent mutagenic ligation. Low-fidelity Cdc9EE/AA/LIGEE/AA proceeds to mutagenic ligation.

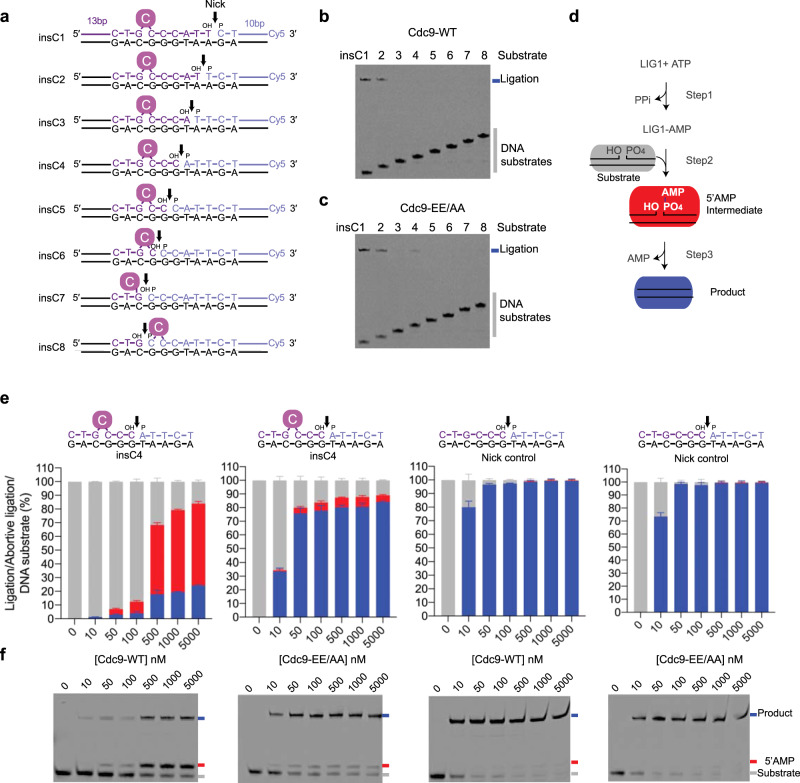

Fig. 5. Cdc9 DNA ligation activity on bulged single-nucleotide insertion substrates.

a Schematic of the 3′-Cy5-labeled bulged insertion substrates (insC1–insC8). The DNA nicks (black arrows) of the bulged insertion substrates are placed at various positions relative to the bulged cytosine base (solid purple circle C) within the cdc9EE/AA URA3 reporter gene mutation hotspot sequence context. b, c Cdc9 ligation activity on insC substrates. A denaturing gel image of ligation reactions in the presence of 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM ATP, 15 mM NaCl, and 50 nM DNA substrate (insC1–insC8). Reactions contained 2 nM of Cdc9WT (b) or Cdc9EE/AA (c). Each of these experiments was repeated independently three times with similar results. d The three step ATP-dependent DNA ligation reaction. In Step 1, DNA ligase adenylates its active site lysine. The enzyme-AMP intermediate engages the nicked DNA substrate (gray) and the AMP group is then transferred to the 5′-phosphate of the nicked DNA to form the 5′AMP-DNA intermediate (red) in Step 2. A phosphodiester bond is formed in Step 3 to yield the ligated product (blue) and AMP is released. e Quantification of total catalytic events on insC4 (left 2 graphs) and control nicked DNA (right 2 graphs) producing ligated product (blue bars) and abortive DNA adenylation (red bars) by Cdc9WT or Cdc9EE/AA analyzed with the ImageQuant TL software (GE). Mean ± SD (n = 3 replicates) is displayed for 20 min ligation reactions. f Representative denaturing gel image of Cdc9 ligation reactions on insC4 (left 2 gels) or control nicked DNA (right 2 gels) in the presence of 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM ATP, 115 mM NaCl, and 50 nM DNA substrate. Reactions contained 0–5000 nM of Cdc9WT or Cdc9EE/AA at 25 °C for 20 min. Each of these experiments was repeated independently three times with similar results. Source data for panels are provided as a Source data file.

Cdc9WT-catalyzed DNA ligation is markedly influenced by the positioning of a 1 nucleotide insC bulge (Fig. 5a, b, substrates insC1–insC8). Whereas Cdc9WT was active on all non-bulged substrate controls (Supplementary Fig. 6, substrates 1c–8c), it only ligated insC substrates with a bulge positioned 6–7 nucleotides 5′-terminal to a nick containing the ligatable 3′-hydroxyl (OH) and 5′-phosphate (P) ends (Fig. 5a, b, substrates insC1 and insC2). This result was expected, as the bulged cytosine nucleotide of insC1 and insC2 substrates falls outside the enzymatic footprint of eukaryotic DNA ligases on the upstream strand of a nick14 and should therefore not impede catalysis (Supplementary Fig. 6). Strikingly, the low-fidelity Cdc9EE/AA enzyme could also ligate the insC4 substrate with a bulged nucleotide proximal to the nick (Fig. 5a, c, substrate insC4). Cdc9WT enzyme titrations (Fig. 5e, f and Supplementary Fig. 6d) show that Cdc9WT ligation activity is substantially impaired on insC4 compared to a non-bulged control, with >50% of catalytic events yielding abortive DNA ligation products (5′-AMP-modified DNA ends). In contrast, Cdc9EE/AA displays robust activity on insC4, with >70% catalytic events yielding mutagenic insertion ligation products (Fig. 5e, f) and modest accumulation (<5%) of abortive products.

Like for Cdc9WT, under low-salt conditions (15 mM NaCl) human LIG1WT activity on bulged DNA is decreased overall and prone to production of abortive 5′-AMP intermediates (Supplementary Fig. 7). In higher salt (115 mM NaCl), LIG1WT displays no detectable catalytic activity on insC4, (Supplementary Fig. 7). Similar to the yeast enzyme, the marked discrimination of LIG1 against catalysis on insC4 is significantly suppressed for the low-fidelity LIGEE/AA mutant, even in the higher stringency reaction conditions (Supplementary Fig. 7). We note that the bulged nucleotide could be accommodated in any of the 4 registers, including a 3′-flap conformation that is presumably non-ligatable. As a significant (~20%) fraction of the insC4 substrate remains unligated by the Cdc9EE/AA protein, even at our highest enzyme concentrations, variable conformations in annealing of the 3′ bulge may also impact ligation efficiency. Together, these results reveal that single-nucleotide bulges positioned 4 nt upstream of a DNA nick normally confound ligation by yeast and human LIG1 homologs, but low-fidelity Cdc9 and LIG1 variants efficiently circumvent this guard against abortive and mutagenic ligation.

Molecular basis for mutagenic ligation by low-fidelity LIG1

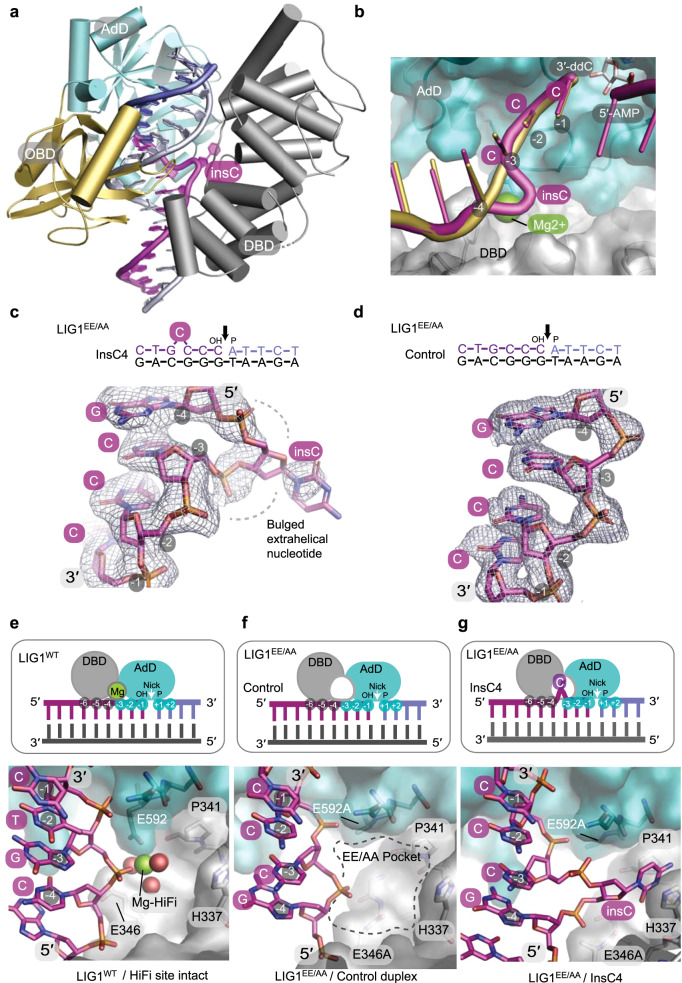

To define the basis for mutagenic ligation, we crystallized and determined X-ray crystal structures (Supplementary Table 9) of low-fidelity LIG1EE/AA bound to insC4 (2.8 Å resolution), a non-bulged 4c control (2.2 Å resolution), and compared them to the previously determined HiFi-Mg2+-bound LIG1WT DNA complex14. Overall, the DNA ligase structure adopts a closed, catalytically competent conformation poised for DNA nick sealing (step 3) and is characterized by DNA ligase DBD–AdD–OBD domain encirclement of the DNA substrate (Fig. 6a). The inserted bulged nucleotide is accommodated at the interface between the LIG1 DBD and AdD domains (Fig. 6b).

Fig. 6. Molecular basis of mutagenic ligation by LIG1EE/AA.

a LIG1EE/AA X-ray structure in complex with +1 nucleotide insertion DNA (insC4). The DBD (gray), AdD (teal), and OBD (gold) domains encircle a bulged nicked DNA substrate (bulged 3′-OH strand, magenta; 5′-P strand, blue; continuous strand, gray). b Structural overlay of LIG1WT-DNA (PDB 6P09)14 and LIG1EE/AA-bulged DNA complexes shows that the backbone path of the bulged DNA (magenta) is distorted at the HiFi Mg2+-binding pocket. LIG1WT binds the HiFi Mg2+ (green) at the juncture between the 3′-OH of the upstream DNA (gold), AdD (teal), and DBD (gray). c Omit Fo–Fc electron density contoured at 2σ displayed for the bulged 3′-OH strand bound in the LIG1EE/AA-bulged DNA complexes. d, Omit Fo–Fc electron density contoured at 2σ and displayed for the unbulged upstream 3′-OH strand bound in the LIG1EE/AA-unbulged DNA complex. e–g Cartoon representations (top panels) and surface-filled representation of X-ray structures (bottom panels) depict protein–DNA contacts at the HiFi metal-binding sites of the LIG1WT-DNA (e, PDB 6P09), LIG1EE/AA-unbulged DNA (f), and LIG1EE/AA-bulged insC4 DNA (g) complexes. The HiFi Mg2+ bridging the nt −3 and nt −4 nucleotides of the 3′-OH strand relative to the nick site. The AdD binds across the broken DNA strands with the nick positioned over the active site and makes contacts with nt +2 to nt −3 while the DBD contacts nt −4 to nt −6. f, Removal of the HiFi Mg2+ ligands (E592A/E346A) results in a cavity (EE/AA pocket). g The bulged extrahelical nucleotide (the fourth cytosine upstream of the DNA nick) in the LIG1EE/AA-bulged DNA complex occupies the EE/AA pocket created by removal of the HiFi Mg2+-binding site. Source data for panels are provided as a Source data file.

In principle, as insC4 has 4 C nucleotides that could be paired in variable registers with the 3 G nucleotides of the opposite strand, the bulge could be accommodated in any of three registers within the ligase active site. However, comparison of difference omit Fo–Fc electron density for the upstream 3′-OH DNA strand reveals that a significant distortion in the DNA backbone path is observed for the insC4 sequence between the −3 and −4 positions relative to the DNA nick, indicating that the bulge is accommodated in a specific register (Fig. 6c). By comparison, fully paired duplex substrate is not bulged, as anticipated (Fig. 6d, “Methods”, and Supplementary Movie 1).

Binding of the upstream 3′-OH strand by LIG1WT is normally reinforced by a protein–Mg2+–DNA interface, with Mg2+–HiFi metal coordination mediated by the stringently conserved Glu346 and Glu592 ligands (Fig. 6e). In a control mutant LIG1EE/AA unbulged DNA complex structure (Fig. 6f), a prominent pocket created by the engineered EE/AA mutant is found at the DBD–AdD interface. It is this cavity which houses the bulged nucleotide in the insC4 complex (Fig. 6g). Notably, electron density for the budged nucleobase is less well defined than the backbone phosphates (Fig. 6c), indicating flexibility of the flipped nucleobase which is positioned near Pro341 and His337 in the EE/AA pocket. We conclude that structural plasticity imparted by the cavity created by deleting the HiFi metal and its ligands likely facilitates dynamic binding and flipping of the first C of the four cytosines (Fig. 6g).

Discussion

Overall, our genetic and biochemical data demonstrate that high-fidelity in vivo ligation by the yeast replicative Cdc9 requires an intact high-fidelity protein–metal–DNA interface. High-fidelity ligation prevents sealing of DNA Pol-incorporated slippage mutations occurring at homopolymeric repeats, and expression of an engineered low-fidelity cdc9-EE/AA allele is a potent mutator in yeast. Biochemical studies of Cdc9 and a LIG1 X-ray structure with insC4 show how the mutant enzyme accommodates a bulged insC substrate by exploiting the engineered cavity created by deleting the high-fidelity metal-binding site in the enzyme.

The results presented here have several implications regarding OFM, the second most abundant DNA transaction occurring in eukaryotic cells. Overall, the data strongly imply that, under normal circumstances, wild-type LIG1 accurately seals nicks in newly replicated lagging strand DNA and that the fidelity of this ligation reaction is strongly reduced by the Cdc9EE/AA mutation. In this study, the mutagenic effects of expressing the low-fidelity Cdc9EE/AA are largely devoted to +1 additions, but we cannot yet exclude that other mutations such as large multibase additions, duplications, or genomic rearrangements could result from suppressed ligation fidelity. A whole-genome approach using the low-fidelity cdc9-EE/AA mutant may also be useful for studying the role of DNA Pol α in replicating telomeric DNA40 and/or the potential importance of high-fidelity ligation during OFM in preventing tumorigenesis. Strikingly, one of the mutational signatures identified in certain tumors is the addition of single base pairs in homonucleotide runs41,42 that arose due to DNA Pol slippage during replication23. Could the +1 mutations in these tumors be caused by a defect in DNA ligation or other OFM-associated proteins?

The selective +1 error signature seen here has not been observed in studies of the fidelity of normal chain elongation by Family B DNA Pols α, δ, and ε43. Those DNA synthesis reactions by these Pols involve bulk chain elongation of open templates that lack an upstream duplex and, as such, do not require nick translation or strand displacement DNA synthesis9,44. The absence of a +1 error signature suggests that there may be fidelity protection mechanisms acting during nick translation/strand displacement synthesis characteristic of OFM. For example, is strand displacement synthesis energetically more costly than simple chain elongation, thereby resulting in DNA strand slippage that leads to single base additions when ligation is defective? These results suggest that Pol δ makes +1 slippage mutations frequently during strand displacement synthesis, and we are currently testing whether the 3′-exonuclease activity of Pol δ is capable of proofreading such replication errors. DNA ligase prevents these mutations by acting as a molecular iron, suggesting that ligase fidelity is critical for preventing errors generated during strand displacement synthesis by Pol δ. While the current data suggest that the mutagenesis observed may be due to perturbation of OFM, they do not exclude other possibilities. For instance, an increased rate of +1 additions could occur in any transaction involving DNA strand displacement synthesis, including recombination and DNA repair.

Methods

Yeast strain construction and growth analysis

S. cerevisiae strains are isogenic derivatives of strain ∆|(−2)|−7B-YUNI300 (MATa CAN1 his7-2 leu2Δ::kanMX ura3Δ trp1-289 ade2-1 lys2∆GG2899-2900 agp1::URA3-OR1)45, and relevant genotypes are listed in Supplementary Table 1. The cdc9-E206A-E443A-5FLAG:HphMX6 (cdc9-EE/AA) mutant strain was generated using a plasmid containing Cdc9 C-terminally tagged with 5×-FLAG and flanked by 600 bp of upstream and downstream sequences. Mutagenesis was performed using the QuikChange II Site-directed Mutagenesis Kit (Agilent). Construction of diploids heterozygous for MSH2/msh2::LEU2, MSH6/msh6::LEU2, MSH3/msh3::LEU2, or RAD27/rad27::LEU2 was performed by deletion replacement of one copy of each of the respective genes using the pUG73 plasmid46. Transformants were verified by marker selection and PCR analysis, as were the haploids derived from tetrad dissections. Yeast dissection plates were photographed after 3-day growth on rich (YPDA) medium at 30 °C.

Strains were grown in YPDA medium (1% yeast extract, 2% bacto-peptone, 250 mg l−1 adenine, 2% dextrose, 2% agar for plates) at 30 °C. Doubling time (Dt) was measured for logarithmically growing cultures using between 4 and 12 replicates for each experiment. Data are displayed as the mean Dt +/− standard deviation (SD). Microscopy was performed using cultures grown in rich medium at 30 °C to mid-logarithmic phase. Live cells were imaged with a Leitz Diaplan microscope combined with a Zeiss AxioCam MRm Rev.3 camera.

Spontaneous mutation rate and sequencing analysis

Mutation rate analysis was performed in strains containing the URA3 reporter gene placed in orientation 1 adjacent to an efficient, early-firing replication origin, ARS306. In orientation 1, the leading and lagging strand of URA3 have been defined in studies using mutator variants of DNA Pols δ and ε33–38. The coding sequence of the URA3 reporter gene is displayed. Mutation rates and 95% confidence intervals were determined by measuring fluctuation analysis as described47. Because the cdc9-EE/AA msh2Δ and cdc9-EE/AA rad27Δ haploid strains were highly mutable, we sporulated diploid strains that were heterozygous for msh2Δ or rad27Δ and used freshly dissected independent spore colonies to measure the spontaneous mutation rate, thereby minimizing the number of generations during which mutations could rapidly accumulate and modulate mutation rates. The ura3 gene from single, independent 5-FOA-resistant (5-FOAR) colonies was PCR-amplified and sequenced. Specific mutation rates were calculated by multiplying the fraction of that mutation type by the total mutation rate for each strain.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 8. P value determination for doubling time measurements was performed using the unpaired Student’s t test, two tailed. Statistical analysis of overall mutation rate comparisons was performed using the one-sided nonparametric Mann–Whitney test.

Mutagenesis, protein expression, and purification

LIG1EE/AA was generated using QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis (Stratagene). LIG1WT and LIG1EE/AA proteins (aa262–904) were expressed in Escherichia coli Rosetta 2 (DE3) cells as previously described14. Genes encoding the Cdc9WT and Cdc9EE/AA proteins (aa112–754) were cloned into pET28M expression vector using NotI and BamHI restriction sites. The Cdc9 protein was expressed as an N-terminal His-tagged protein in E. coli Rosetta 2 (DE3) cells (Novagen). Cell cultures were grown at 37 °C in Terrific Broth supplemented with kanamycin (50 μg ml−1) and chloramphenicol (34 ng ml−1) until A600 reached 1, at which time 50 μM IPTG was added. Protein expression was carried out at 16 °C overnight. Cells were harvested by centrifugation (6240 rcf, 20 min). Cell pellet was suspended and lysed in 30 ml lysis buffer (50 mM Tris, pH 8.5, 500 mM NaCl, 10 mM imidazole, 0.1 g lysozyme/1 l pellet, 1 tablet Roche mini EDTA-free protease inhibitor cocktail) at 4 °C for 30 min, followed by sonication. The cell lysate was fractionated by centrifugation (30,220 rcf, 20 min, 4 °C). The soluble fraction was applied to Ni-NTA resins (5 ml packed volume), which has been equilibrated with 15 ml (50 mM Tris, pH 8.5, 500 mM NaCl, 10 mM imidazole). The column was washed with 100 ml (50 mM Tris, pH 8.5, 500 mM NaCl, 10 mM imidazole), 15 ml (50 mM Tris, pH 8.5, 500 mM NaCl, 30 mM imidazole), and the His-tagged protein was eluted in 15 ml (50 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 500 mM NaCl, 300 mM imidazole). The His-tag was removed by TEV protease at 4 °C overnight. The untagged protein was purified on HiLoad 16/600 Superdex 200 gel filtration column in buffer (25 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM TCEP, 0.1 mM EDTA), followed by HiTrap SP HP 5 ml cation exchange column (low salt buffer: 20 mM Tris 7.5, 0.2 mM EDTA, 1 mM TCEP; high salt buffer: 20 mM Tris 7.5, 1 M NaCl, 0.2 mM EDTA, 1 mM TCEP). The quality of the purified proteins was analyzed by sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Freshly purified proteins were concentrated and used immediately in crystallization experiments. Proteins used in activity assays were stored in (25 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 20% glycerol) at −80 °C until use.

Ligation of Insertion DNA (insC1–insC8) and Controls (1c–8c)

Synthetic oligos were used to generate Insertion DNA (insC1–insC8) and Control DNA (1c–8c) (IDT) (Supplementary Table 10). Each ligation reaction (10 μl) containing DNA ligase protein (2 nM), Insertion DNA, or Control DNA (50 nM) (Fig. 5a and Supplementary Fig. 6) in 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 10 mM MgCl2, 10 mM DTT, 1 mM ATP, and 15 mM NaCl was carried out at 25 °C for 20 min, followed by a 10-min heat inactivation in 20 μl formamide loading buffer (98% formamide, 2% EDTA). Ligation reactions were resolved on 20% TBE-Urea gels and the Cy5-labeled reaction products were visualized on a Typhoon scanner (GE Healthcare) and analyzed using ImageQuant TL.

Ligation of Insertion DNA 4 (insC4) and Control DNA 4 (4c)

LIG1 and Cdc9 ligation activity on insC4 and 4c was evaluated. Ligation reactions (10 μl) containing insC4 or 4c (50 nM) (Fig. 5a and Supplementary Table 10) and DNA ligase protein (0–5000 nM) in 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 10 mM MgCl2, 10 mM DTT, 1 mM ATP, and 115 mM NaCl were carried out at 25 °C for 20 min, followed by a 10-min heat inactivation in 20 μl formamide loading buffer (98% formamide, 2% EDTA). Ligation reactions were resolved on 20% TBE-Urea gels and Cy5-labeled reaction products were visualized on a Typhoon scanner (GE Healthcare). The percentages of DNA substrates, reaction intermediates, and products were generated by ImageQuant TL.

Crystallization and structure determination

Crystals of LIG1EE/AA-unbulged DNA complex were grown by hanging drop method. 1 µL of protein–DNA complex solution (17 mg ml−1 LIG1EE/AA (aa262–904), nicked 18mer from annealing oligos 1, 3, and 4 (Supplementary Table 11) (1.5:1 DNA:protein molar ratio), 1 mM ATP, 1 mM MgCl2, in 150 mM NaCl, 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, and 1 mM TCEP) with an equal volume of precipitant solution (100 mM MES, pH 6, 100 mM lithium acetate, 12% (w/v) polyethylene glycol 3350) at 20 °C. Crystals grew within 24 h and were washed in cryoprotectant (20% PEG3350 and 20% glycerol in precipitant solution supplemented with 100 mM MgCl2) and flash frozen in liquid nitrogen for data collection.

Crystals of LIG1EE/AA-bulged DNA complex were grown by hanging drop method. 1 µL of protein-DNA complex solution (20 mg ml−1 LIG1EE/AA (aa262–904), nicked 18mer from annealing oligos 1, 2, and 4 (Supplementary Table 10) (1.5:1 DNA:protein molar ratio), 1 mM ATP, 1 mM MgCl2, in 150 mM NaCl, 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, and 1 mM TCEP) with an equal volume of precipitant solution (100 mM MES, pH 6, 150 mM lithium acetate, 10% (w/v) polyethylene glycol 3350) at 20 °C. The crystallization drops were allowed to equilibrate overnight. Microcrystal seeds prepared from crystals of LIG1EE/AA-unbulged DNA complex was streaked into the drops. Crystals appeared after ~60 days and were washed in cryoprotectant (20% PEG3350 and 20% glycerol in precipitant solution supplemented with 100 mM MgCl2) and flash frozen in liquid nitrogen for data collection.

X-ray diffraction data was collected on Beamline 22-ID of the Advanced Photon Source at a wavelength of 1.000 Å. X-ray diffraction data were processed and scaled using the HKL2000 suite48. All structures were solved by molecular replacement using PDB entry 6P09 as a search model with PHASER49. Iterative rounds of model building in COOT50 and refinement with PHENIX51 were used to produce the final models.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Supplementary information

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Acknowledgements

X-ray diffraction data were collected at the Southeast Regional Collaborative Access Team (SER-CAT) 22-ID beamline at the Advanced Photon Source, Argonne National Laboratory. Use of the Advanced Photon Source was supported by the U. S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences under Contract No. W-31-109-Eng-38. We thank Lars Pedersen of the NIEHS collaborative crystallography group and the Advanced Photon Source (APS) Southeast Regional Collaborative Access Team (SER-CAT) staff for assistance with crystallographic data collection. The pET28M vector was a kind gift from L. Pedersen. We thank Bill Copeland for microscope access and Dmitry Gordenin, Andrea Kaminski, and Lars Pedersen for critical reading of the manuscript. This work was supported by the intramural research program of the US National Institutes of Health (NIH), National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS) grants 1Z01ES102765 to R.S.W. and Z01ES065070 to T.A.K.

Source data

Author contributions

Conceptualization: J.S.W., P.P.T., R.S.W., T.A.K.; methodology: J.S.W., P.P.T., M.E.A., R.S.W.; investigation: J.S.W., P.P.T., M.E.A., J.A.R., R.S.W.; data analysis: J.S.W., P.P.T., M.E.A., J.A.R., R.S.W.; writing—original draft: J.S.W., P.P.T., R.S.W., T.A.K.; writing—review and editing: J.S.W., P.P.T., M.E.A., R.S.W., T.A.K.; supervision: R.S.W., T.A.K.

Data availability

A reporting summary for this article is available as a Supplementary Information file. Atomic coordinates and structure factors for the reported crystal structures have been deposited with the RCSB Protein Data Bank under accession numbers 7KR3 and 7KR4. The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon request. Source data are provided with this paper.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Peer review information Nature Communications thanks Lata Balakrishnan, Bennett Van Houten, and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Jessica S. Williams, Percy P. Tumbale, Mercedes E. Arana.

Contributor Information

R. Scott Williams, Email: williamsrs@niehs.nih.gov.

Thomas A. Kunkel, Email: kunkel@niehs.nih.gov

Supplementary information

Supplementary information is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41467-020-20800-1.

References

- 1.Burgers PMJ, Kunkel TA. Eukaryotic DNA replication fork. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2017;86:417–438. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-061516-044709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zheng L, Shen B. Okazaki fragment maturation: nucleases take centre stage. J. Mol. Cell Biol. 2011;3:23–30. doi: 10.1093/jmcb/mjq048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kao HI, Bambara RA. The protein components and mechanism of eukaryotic Okazaki fragment maturation. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2003;38:433–452. doi: 10.1080/10409230390259382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stodola JL, Burgers PM. Mechanism of lagging-strand DNA replication in eukaryotes. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2017;1042:117–133. doi: 10.1007/978-981-10-6955-0_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Balakrishnan, L. & Bambara, R. A. Okazaki fragment metabolism. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 5, a010173 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Bambara RA, Murante RS, Henricksen LA. Enzymes and reactions at the eukaryotic DNA replication fork. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:4647–4650. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.8.4647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Giannattasio, M. & Branzei, D. DNA replication through strand displacement during lagging strand DNA synthesis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genes10, 167 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Ayyagari R, Gomes XV, Gordenin DA, Burgers PM. Okazaki fragment maturation in yeast. I. Distribution of functions between FEN1 AND DNA2. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:1618–1625. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209801200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jin YH, Ayyagari R, Resnick MA, Gordenin DA, Burgers PM. Okazaki fragment maturation in yeast. II. Cooperation between the polymerase and 3′-5′-exonuclease activities of Pol delta in the creation of a ligatable nick. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:1626–1633. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209803200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gloor JW, Balakrishnan L, Campbell JL, Bambara RA. Biochemical analyses indicate that binding and cleavage specificities define the ordered processing of human Okazaki fragments by Dna2 and FEN1. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:6774–6786. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Andres SN, Schellenberg MJ, Wallace BD, Tumbale P, Williams RS. Recognition and repair of chemically heterogeneous structures at DNA ends. Environ. Mol. Mutagen. 2015;56:1–21. doi: 10.1002/em.21892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Showalter AK, et al. Mechanistic comparison of high-fidelity and error-prone DNA polymerases and ligases involved in DNA repair. Chem. Rev. 2006;106:340–360. doi: 10.1021/cr040487k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Williamson, A. & Leiros, H. S. Structural insight into DNA joining: from conserved mechanisms to diverse scaffolds. Nucleic Acids Res.48, 8225–8242 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Tumbale PP, et al. Two-tiered enforcement of high-fidelity DNA ligation. Nat. Commun. 2019;10:5431. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-13478-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fortune JM, et al. Saccharomyces cerevisiae DNA polymerase delta: high fidelity for base substitutions but lower fidelity for single- and multi-base deletions. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:29980–29987. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M505236200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shcherbakova PV, et al. Unique error signature of the four-subunit yeast DNA polymerase epsilon. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:43770–43780. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306893200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Strand M, Earley MC, Crouse GF, Petes TD. Mutations in the MSH3 gene preferentially lead to deletions within tracts of simple repetitive DNA in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1995;92:10418–10421. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.22.10418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tran HT, Gordenin DA, Resnick MA. The 3′–>5′ exonucleases of DNA polymerases delta and epsilon and the 5′–>3′ exonuclease Exo1 have major roles in postreplication mutation avoidance in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1999;19:2000–2007. doi: 10.1128/MCB.19.3.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sia EA, Kokoska RJ, Dominska M, Greenwell P, Petes TD. Microsatellite instability in yeast: dependence on repeat unit size and DNA mismatch repair genes. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1997;17:2851–2858. doi: 10.1128/MCB.17.5.2851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kunkel TA, Erie DA. Eukaryotic mismatch repair in relation to DNA replication. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2015;49:291–313. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-112414-054722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Romanova NV, Crouse GF. Different roles of eukaryotic MutS and MutL complexes in repair of small insertion and deletion loops in yeast. PLoS Genet. 2013;9:e1003920. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Garcia-Diaz M, Kunkel TA. Mechanism of a genetic glissando: structural biology of indel mutations. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2006;31:206–214. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2006.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Streisinger G, et al. Frameshift mutations and the genetic code. This paper is dedicated to Professor Theodosius Dobzhansky on the occasion of his 66th birthday. Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol. 1966;31:77–84. doi: 10.1101/SQB.1966.031.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smith DJ, Whitehouse I. Intrinsic coupling of lagging-strand synthesis to chromatin assembly. Nature. 2012;483:434–438. doi: 10.1038/nature10895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sriramachandran, A. M. et al. Genome-wide nucleotide-resolution mapping of DNA replication patterns, single-strand breaks, and lesions by GLOE-seq. Mol. Cell78, 975.e7–985.e7 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Chafin DR, Vitolo JM, Henricksen LA, Bambara RA, Hayes JJ. Human DNA ligase I efficiently seals nicks in nucleosomes. EMBO J. 2000;19:5492–5501. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.20.5492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jiricny J. Postreplicative mismatch repair. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2013;5:a012633. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a012633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Harrington JM, Kolodner RD. Saccharomyces cerevisiae Msh2-Msh3 acts in repair of base-base mispairs. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2007;27:6546–6554. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00855-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tishkoff DX, Filosi N, Gaida GM, Kolodner RD. A novel mutation avoidance mechanism dependent on S. cerevisiae RAD27 is distinct from DNA mismatch repair. Cell. 1997;88:253–263. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81846-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xie Y, et al. Identification of rad27 mutations that confer differential defects in mutation avoidance, repeat tract instability, and flap cleavage. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2001;21:4889–4899. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.15.4889-4899.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kao HI, Veeraraghavan J, Polaczek P, Campbell JL, Bambara RA. On the roles of Saccharomyces cerevisiae Dna2p and Flap endonuclease 1 in Okazaki fragment processing. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:15014–15024. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313216200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rossi ML, Bambara RA. Reconstituted Okazaki fragment processing indicates two pathways of primer removal. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:26051–26061. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M604805200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pursell ZF, Isoz I, Lundstrom EB, Johansson E, Kunkel TA. Yeast DNA polymerase epsilon participates in leading-strand DNA replication. Science. 2007;317:127–130. doi: 10.1126/science.1144067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nick McElhinny SA, Gordenin DA, Stith CM, Burgers PM, Kunkel TA. Division of labor at the eukaryotic replication fork. Mol. Cell. 2008;30:137–144. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.02.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lujan SA, et al. Mismatch repair balances leading and lagging strand DNA replication fidelity. PLoS Genet. 2012;8:e1003016. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Williams JS, et al. Topoisomerase 1-mediated removal of ribonucleotides from nascent leading-strand DNA. Mol. Cell. 2013;49:1010–1015. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.12.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lujan SA, Williams JS, Clausen AR, Clark AB, Kunkel TA. Ribonucleotides are signals for mismatch repair of leading-strand replication errors. Mol. Cell. 2013;50:437–443. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Williams JS, et al. Evidence that processing of ribonucleotides in DNA by topoisomerase 1 is leading-strand specific. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2015;22:291–297. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kadyrova LY, Dahal BK, Kadyrov FA. Evidence that the DNA mismatch repair system removes 1-nucleotide Okazaki fragment flaps. J. Biol. Chem. 2015;290:24051–24065. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.660357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mirman Z, et al. 53BP1-RIF1-shieldin counteracts DSB resection through CST- and Polalpha-dependent fill-in. Nature. 2018;560:112–116. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0324-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Alexandrov LB, et al. Signatures of mutational processes in human cancer. Nature. 2013;500:415–421. doi: 10.1038/nature12477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Alexandrov LB, et al. The repertoire of mutational signatures in human cancer. Nature. 2020;578:94–101. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-1943-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lujan SA, Williams JS, Kunkel TA. Eukaryotic genome instability in light of asymmetric DNA replication. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2016;51:43–52. doi: 10.3109/10409238.2015.1117055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Garg P, Stith CM, Sabouri N, Johansson E, Burgers PM. Idling by DNA polymerase delta maintains a ligatable nick during lagging-strand DNA replication. Genes Dev. 2004;18:2764–2773. doi: 10.1101/gad.1252304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pavlov YI, Shcherbakova PV, Kunkel TA. In vivo consequences of putative active site mutations in yeast DNA polymerases alpha, epsilon, delta, and zeta. Genetics. 2001;159:47–64. doi: 10.1093/genetics/159.1.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gueldener U, Heinisch J, Koehler GJ, Voss D, Hegemann JH. A second set of loxP marker cassettes for Cre-mediated multiple gene knockouts in budding yeast. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:e23. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.6.e23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shcherbakova PV, Kunkel TA. Mutator phenotypes conferred by MLH1 overexpression and by heterozygosity for mlh1 mutations. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1999;19:3177–3183. doi: 10.1128/MCB.19.4.3177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Otwinowski Z, Minor W. Processing of X-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Methods Enzymol. 1997;276:307–326. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(97)76066-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.McCoy AJ, et al. Phaser crystallographic software. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2007;40:658–674. doi: 10.1107/S0021889807021206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Emsley P, Lohkamp B, Scott WG, Cowtan K. Features and development of Coot. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2010;66:486–501. doi: 10.1107/S0907444910007493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Adams PD, et al. The Phenix software for automated determination of macromolecular structures. Methods. 2011;55:94–106. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2011.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nick McElhinny SA, Kissling GE, Kunkel TA. Differential correction of lagging-strand replication errors made by DNA polymerases {alpha} and {delta} Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:21070–21075. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1013048107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Data Availability Statement

A reporting summary for this article is available as a Supplementary Information file. Atomic coordinates and structure factors for the reported crystal structures have been deposited with the RCSB Protein Data Bank under accession numbers 7KR3 and 7KR4. The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon request. Source data are provided with this paper.