Abstract

In the era of the targeted therapy identification of EGFR mutation detection in lung cancer is extremely helpful to predict the treatment efficacy of EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs). Unfortunately, the inadequacy and quality of the biopsy samples are the major obstacles in molecular testing of EGFR mutation in lung cancer. To address this issue, the present study intended to use liquid biopsy as the non-invasive method for EGFR mutation detection. A total of 31 patients with an advanced stage of lung cancer were enrolled in the study from which cell-free DNA (cfDNA) and FFPE tissue DNA was extracted. Extracted DNA samples were analyzed for further EGFR exon specific mutation analysis by ARMS-PCR. Data were analyzed statistically using SPSS software. In cfDNA samples, the prevalence of wild type EGFR was 48% while the prevalence of TKI resistant and TKI sensitive mutations were 3%. Conversely, in tissue DNA samples, the prevalence of wild type, TKI sensitive and TKI resistant mutations were 48%, 19%, and 3%, respectively. The overall concordance of EGFR mutation between cfDNA and tissue DNA was 83%. McNemar’s test revealed that there was no significant difference between EGFR expression of cfDNA and tissue DNA samples. Additionally, the significant-high incidence of TKI resistant mutations was observed in tobacco habituates, indicating the role of carcinogens present in the tobacco in developing resistant mutations. In conclusion, our data suggest that evaluation of EGFR mutation from cfDNA samples is practicable as a non-invasive tool in patients with advanced-stage of lung cancer.

Keywords: ARMS real-time PCR, Cell-free DNA, EGFR mutation, Non-small cell lung cancer

Introduction

Lung cancer is one of the most commonly diagnosed carcinomas and the top cause of cancer-related death [1]. It accounts for 13% of all new cancer cases and 19% of cancer-related deaths worldwide [2]. In India, lung cancer constitutes 6.9% of all new cancer cases and 9.3% of all cancer-related deaths in both sexes [3]. Among them, Non-small cell lung cancers (NSCLC) account for about 85% of all lung cancers which can be either adenocarcinoma or other including squamous cell carcinoma [4]. Most of NSCLC is a locally advanced or metastatic stage which is affiliated with constrained therapy option and poor prognosis at appearance. Recent advances in the understanding of cell signaling pathways that control cell survival have identified genetic and regulatory aberrations that suppress cell death, promote cell division, and induce tumorigenesis [5]. One of the key molecules in these pathways is the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR). EGFR; also known as HER1, first described in 1962, is a 170-kDa transmembrane receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) with an extracellular ligand-binding domain, a lipophilic transmembrane region and an intracellular regulatory domain with tyrosine kinase activity. On the tyrosine kinase domain of the EGFR gene, definite types of activating mutations are found to be present which further confirms the sensitivity and resistance for EGFR TKIs such as gefitinib and erlotinib which are reversible competitive inhibitors of the TKIs [6]. EGFR mutations are usually heterozygous, with the mutant allele also showing gene amplification [4]. Overexpression of EGFR has been reported and implicated in the pathogenesis of many human malignancies, including NSCLC [7, 8]. The EGFR gene is located in the short arm of chromosome 7 consisting of 28 exons. If mutations are present in exons 18 to 21, it gives resistance to EGFR TKIs which are a first-line targeted treatment for lung cancer [9]. Therefore, the identification of change in the EGFR gene expression of any tumor facilitates a more targeted approach towards treatment [10]. Thus, EGFR has become a key focus for the development of personalized therapy in lung cancer.

In the recent past with the expansion of new sensitive molecular techniques, we tried to isolate DNA using different methods: formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded FFPE and cfDNA (cell-free DNA). Because of tumor heterogeneity, increased rate of complications associated with the availability of tumor tissue, high level of C > T/G > A transitions in the 1–25% allele frequency range because of the preservation method such as formalin fixation may lead to the false-positive results for the further molecular assays, therefore we tried liquid biopsies that have the potential to help clinicians to screen patients for disease, stratify patients to the best treatment and monitor treatment response and resistance mechanisms in the tumor. Although, liquid biopsy cannot replace the gold standard tissue biopsy for the molecular and morphological diagnosis of NSCLC but it can be recommended in situations like; (1) when tissue biopsy cannot be obtained or when it is unable to provide a sufficient amount of tumor DNA for molecular analysis and (2) when clinicians looking for the development of TKI resistance mutation in patients on TKI treatment whose disease gets progressed or relapse [11, 12]. It can be adopted for the molecular characterization of the tumor and its non-invasive nature allows repeat sampling to monitor genetic changes over time without the need for a tissue biopsy. So, with the use of a liquid biopsy advantage, we can clarify EGFR mutation status in patients with advanced NSCLC. Based on this information the present study aimed to explore the advantageous use of liquid biopsy as a non-invasive method for EGFR mutation detection.

Materials and Methods

Patient Characteristics

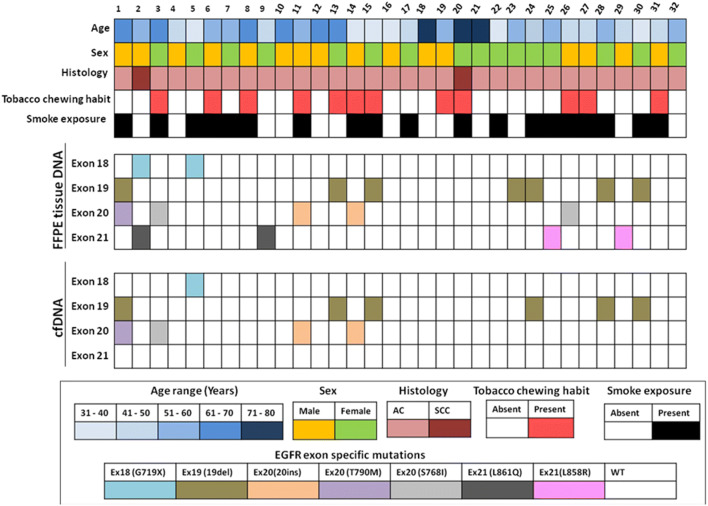

A total of 31 patients diagnosed with an advanced stage of NSCLC were enrolled in this study at the Gujarat Cancer & Research Institute (GCRI) for the relative study. Informed consent was obtained from all the patients before their inclusion in the study. Various clinicopathological parameters such as age, gender, habit and histopathology of the tumor were recorded from the patients’ case files maintained at GCRI (Table 1). Out of 31 patients with lung carcinoma, 87% (27/31) had adenocarcinoma while 13% (04/31) had another histopathological subtype. For EGFR mutation detection archived diagnostic biopsy samples were retrieved for tissue DNA samples while for cell-free DNA (cfDNA) samples; peripheral blood was collected. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study. The study was approved by the institutional review board committee (IRB) and the institutional ethics committee (IEC) of GCRI.

Table 1.

Clinicopathological parameters for 31 patients with lung cancer

| Variables | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| Median: 53 years | |

| < 53 | 16 (52) |

| ≥ 53 | 15 (48) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 16 (52) |

| Female | 15 (48) |

| Habit | |

| Absent | 19 (61) |

| Present | 12 (39) |

| Smoke exposure | |

| Absent | 12 (39) |

| Present | 19 (61) |

| Histopathology | |

| Adenocarcinoma | 17 (55) |

| Metastatic adenocarcinoma | 10 (32) |

| Other subtypes | 04 (13) |

Extraction of DNA from Tumor Tissues

Four to five tumor tissue sections with 5–10 μM thickness were cut from the FFPE biopsy block if the tumor cellularity found was more than 20% on the respective HE slides. In the case of FFPE biopsy block having a tumor load of less than 20% was excluded from DNA extraction. Sections were then deparaffinized and rehydrated in xylene and ethanol, respectively, followed by, DNA extraction using the QIAamp® DNA FFPE Tissue Kit (Qiagen) as per manufacturer’s protocol.

Extraction of cfDNA

For each patient total of 8 mL peripheral blood was collected in EDTA vacutainers and centrifuged at 2000 g for 10 min for the separation of plasma. The separated high-speed plasma was stored at − 80 °C until further use. Before cfDNA extraction, high-speed plasma was thawed and centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 5 min at 4 °C. Circulating cfDNA was isolated using CE IVD approved Helix circulating nucleic acid extraction kit (Diatech pharmacogenetics, Italy). DNA was eluted in 200 μL of elution buffer.

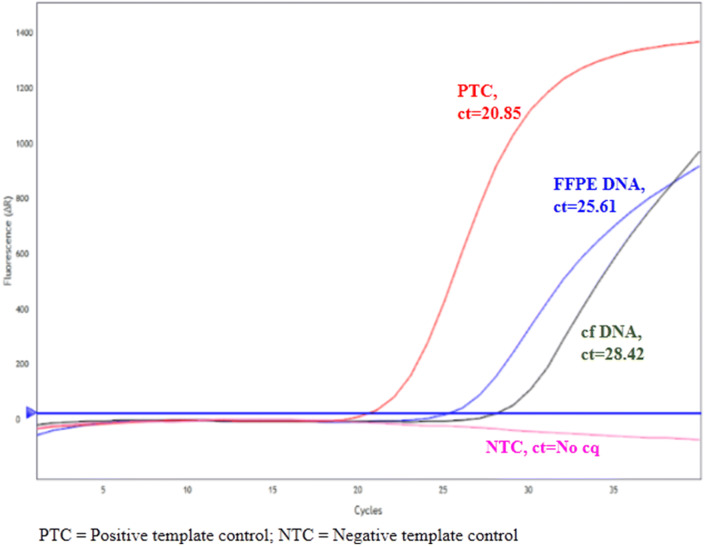

EGFR Mutation Analysis by ARMS PCR

Before EGFR mutation analysis, extracted DNA samples were assessed by real-time PCR using an easy EGFR DNA assessment kit (Diatech Pharmacogenetics, Italy). DNA samples with the defined range of ct values as per the manufacturer’s instructions were preceded further for the mutation analysis (Fig. 1). Following DNA assessment, 5 μL of extracted cfDNA sample was subjected to 40 cycles of PCR reactions to determine the exon specific mutation of EGFR. Each DNA sample was analyzed for the 7 different mutations present on exon 18 (G719X), exon 19 (ex19del), exon 20 (T790M, S768I, ex20ins) and exon 21 (L858R, L861Q). Positive control for each mutation was run with each sample provided along with the kit. While for negative control template was omitted from the reaction mixture.

Fig. 1.

Summary of patient characteristics and EGFR exon specific mutations in matched FFPE tissue DNA and cfDNA samples. Patients were categorized based on age, sex, and tumor histology (top); presence of EGFR exon specific mutation in FFPE tissue DNA (middle); and presence of EGFR exon specific mutation in cfDNA samples (bottom)

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed statistically using SPSS version 20.0. Two-tailed Chi square test was used to examine the association between clinicopathological parameters and the presence of EGFR mutations. Spearman’s correlation coefficient (r) was used to calculate the correlation between clinicopathological parameters and the presence of the mutation. McNemar’s test was used to check the difference between the frequency of samples with EGFR mutations detected in cfDNA and tissue DNA samples. A p value < 0.05 was taken into consideration to show statistical significance.

Results

Clinicopathological Details of the Patients

The median age of the patients enrolled in the study was 53 years with the age range from 35 to 80 years. The majority of the patients (61%; 19/31) had either active or passive smoke exposure. Out of 31 patients, 55% of the patients had histology of adenocarcinoma, 32% of patients had a metastatic adenocarcinoma whereas, 13% of the patients had another histological subtype (Table 1).

Prevalence of EGFR Mutation in FFPE and cfDNA

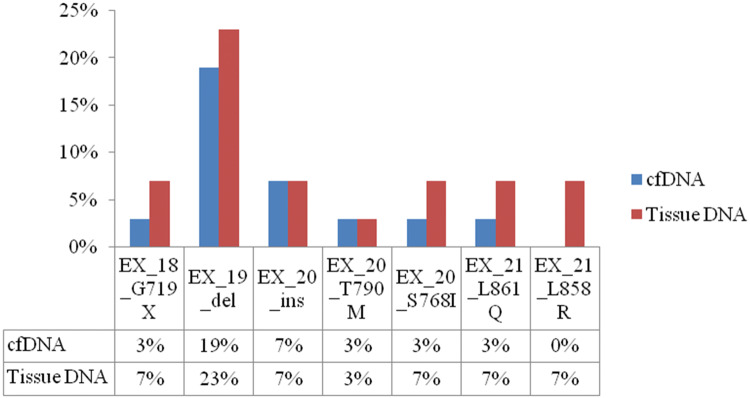

The EGFR mutation status was accessible in all paired samples of plasma and biopsy tissue specimens in patients with lung cancer. A total of 7 mutations from exon 18 to 21 were analyzed in each paired sample. Out of 7 mutations G719X (exon 18), 19deletion (exon 19), L861Q and L858R (exon 21) were TKI sensitive mutations while; 20insertion, T790 M, and S768I (exon 20) were TKI resistant. The prevalence of wild type mutation in plasma DNA samples of the patients included in the current study was 48% (15/31), while that of TKI sensitive and TKI resistant mutations was 3% (01/31) for each. On the other hand, the prevalence of wild type mutation in tissue DNA samples was 48% (15/31) while that of TKI sensitive and TKI resistant mutations were present in 19% (06/31) and 3% (01/31) patients, respectively. A comparison between plasma and tumor DNA samples has table has been depicted in Table 2. A representative real time image showing comparison between FFPE DNA and cfDNA with exone 19deletion mutation is depicted in Fig. 2. The overall concordance of EGFR mutation status was 83% (26/31) in respective plasma and tissue DNA samples. In total, 15 patients had wild type EGFR transcripts in both plasma and tumor tissue samples. On the other hand, 07 patients had TKI sensitive mutation and 04 patients had TKI resistant EGFR mutation in both plasma and tumor tissue DNA samples. A McNemar’s test showed that there was no statistically significant difference between wild type and mutant EGFR of both cfDNA and tissue DNA (p = 0.219; Table 3). Apart from that, when we further bifurcate the EGFR mutations into wild type and resistant mutations, McNemar’s test failed to show statistically significant differences in EGFR mutations in cfDNA and tissue DNA samples (p = 0.284; Table 4). The most common TKI sensitive mutation found was deletion in exon 19 in 23% (07/31) and 19% (06/31) of all mutations present in tumor tissue and cfDNA, respectively (Fig. 3).

Table 2.

EGFR mutation analysis in paired cfDNA and tissue DNA samples

| Tissue DNA | cfDNA | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild type | TKI resistant | TKI sensitive | ||

| Wild type | 15 | 01 | 01 | 17 |

| TKI resistant | 01 | 04 | 00 | 05 |

| TKI sensitive | 06 | 00 | 07 | 13 |

Fig. 2.

A representative real-time image showing comparison of exon 19 deletion mutation between FFPE DNA and cfDNA samples

Table 3.

Comparison of wild type EGFR and mutant EGFR in tissue versus cfDNA samples using McNemar’s test

| Tissue DNA | cfDNA | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wild type EGFR | Mutated EGFR | ||

| N (%) | N (%) | ||

| Wild type EGFR | 14 (93%) | 01 (7%) | 0.219 |

| Mutated EGFR | 05 (31%) | 11 (69%) | |

Table 4.

Comparison of wild type, resistant and sensitive EGFR mutations in tissue versus cfDNA samples using McNemar’s test

| Tissue DNA | cfDNA | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild type EGFR | Sensitive EGFR | Resistant EGFR | ||

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | ||

| Wild type EGFR | 14 (93) | 01 (07) | 00 (00) | 0.284 |

| Sensitive EGFR | 04 (33) | 07 (59) | 01 (08) | |

| Resistant EGFR | 01 (25) | 00 (00) | 03 (75) | |

Fig. 3.

Incidence of EGFR mutations in patients with lung cancer at GCRI

Correlation of EGFR Mutation Status with Clinicopathological Parameters

Based on the prevalence of EGFR mutation, patients were then subgrouped in TKI sensitive and TKI resistant groups and were further correlated with various clinicopathological parameters such as age, gender, the habit of tobacco, smoke exposure and histological type. Amongst them, a significant high incidence of TKI resistant mutations was observed in tumor tissue DNA samples of tobacco habituates (p = 0.0001) while, cfDNA was not significantly correlated with any other clinicopathological parameter (Table 5).

Table 5.

Correlation of plasma EGFR mutation with clinicopathological parameters

| Variables | cfDNA EGFR mutation | Tissue EGFR mutation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TKI sensitive | TKI resistant | TKI sensitive | TKI resistant | |

| Age | ||||

| < 53 | 06 (67) | 03 (33) | 07 (78) | 02 (22) |

| ≥ 53 | 05 (83) | 01 (17) | 04 (67) | 02 (33) |

| χ2 = 0.511, r = − 0.185, p = 0.510 | χ2 = 0.227, r = + 0.123, p = 0.662 | |||

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 04 (67) | 02 (33) | 03 (50) | 03 (50) |

| Female | 07 (78) | 02 (22) | 08 (89) | 01 (11) |

| χ2 = 0.227, r = − 0.123, p = 0.662 | χ2 = 2.784, r = + 0.123, p = 0.662 | |||

| Habit | ||||

| Absent | 07 (70) | 03 (10) | 10 (100) | 00 (00) |

| Present | 04 (80) | 01 (20) | 01 (20) | 04 (80) |

| χ2 = 0.170, r = − 0.107, p = 0.705 | χ2 = 10.909, r = + 0.853, p = 0.0001 | |||

| Smoke exposure | ||||

| Absent | 03 (60) | 02 (40) | 05 (100) | 00 (00) |

| Present | 08 (80) | 02 (20) | 06 (60) | 04 (40) |

| χ2 = 0.682, r = − 0.213, p = 0.446 | χ2 = 2.727, r = + 0.426, p = 0.113 | |||

| Histopathology | ||||

| Adenocarcinoma | 11 (79) | 03 (21) | 10 (71) | 04 (29) |

| other | 00 (00) | 01 (100) | 01 (100) | 00 (00) |

| χ2 = 2.946, r = + 0.443, p = 0.098 | χ2 = 0.390, r = − 0.161, p = 0.566 | |||

| Metastasis | ||||

| Absent | 04 (80) | 01 (20) | 04 (80) | 01 (20) |

| Present | 07 (70) | 03 (30) | 07 (70) | 03 (30) |

| χ2 = 0.170, r = + 0.107, p = 0.705 | χ2 = 0.170, r = + 0.107, p = 0.705 | |||

Discussion

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer-related deaths all over the world. Despite providing good response to chemotherapy, radiation therapy, and adjuvant therapy, these therapies demonstrated unfavorable side effects and hence novel drugs targeting lung cancer emerged essentially. In recent years, various new genes have been identified in hematological and solid malignancies owing to advances in molecular biology and gene sequencing techniques. As a result of that, the identification of any mutation indefinite gene has been promising in the progression of a disease. The presence of such specific genetic mutations in cancer has the potential to treat the disease via personalized medicine or molecular targeted therapy such as gefitinib which is a TKI in treating lung cancer which leads to remarkable response and improved overall survival [13].

In various international studies, EGFR mutation status in plasma has been broadly reported for the prediction of response to EGFR-TKIs [14–16]. The key goal of the present study was to identify the EGFR mutations in plasma samples as surrogates to tissues in our set of patients with lung cancer using newly developed technique so-called liquid biopsy. Along with that, the mutation status was also compared with their respective tumor tissue samples. To best of our knowledge, this is the first report from India reporting the overall concordance of EGFR mutations in circulating cf DNA and tissue DNA samples in patients with lung cancer. Plasma samples were collected after the biopsy was performed. Further, from the analyzed samples 83% of the samples found the identical exon specific mutations both in plasma and tumor tissue specimen which is comparable to other studies, which have varied from 80.0 to 94.19% concordance [17–20]. Although, how cfDNA gets released to the peripheral blood from the tumor tissue is poorly known, it is believed that cfDNA might derive as an offshoot of apoptosis and necrosis of primary tumors, circulating tumor cells or metastatic lesions [21]. Apart from that, the detection of EGFR mutations in cfDNA has remained a challenge due to its low abundance in the circulation, which is attenuated in the overall complex genetic background. Further, several high-sensitivity methods such as scorpion-ARMS, next-generation sequencing, denaturing high-performance liquid chromatography detection and peptide nucleic acid-mediated polymerase chain reaction clamping with the detection sensitivities ranging from 20.7 to 65.79% have been achieved from NSCLC patients with different tumor tissue examination methods [11, 22–24]. Hence, in the present study, concomitant positive EGFR mutations in both tissues and cfDNA by quantitative real-time PCR could be an indication of the presence of a large number of mutated cells in tumor tissues and fragments of dead cells which may drop into the peripheral bloodstream, allowing detection of EGFR mutations easily in cfDNA. Thus, the co-existence of EGFR mutations in tumor tissues and cfDNA is indicative of a high profusion of EGFR mutations, resulting in a good clinical outcome. Studies show that the EGFR mutations present both in plasma and tumor tissues had better predicting and prognostic value to get benefits with first-line TKI treatment in patients with advanced-stage lung cancer [25]. Furthermore, McNemar’s test failed to show the significant statistical difference between EGFR mutation of circulating and tissue DNA sample which is indicative of the presence of significant similarity in EGFR mutation between both the mentioned samples. With clinicopathological parameters and exon mutations present in tissue DNA, a significant positive correlation between TKI resistant mutations was observed in patients with the habit of tobacco which may indicate the major role of carcinogens present in tobacco for developing TKI resistant mutations in patients with lung cancer. However; the mechanism for raising such mutations in lung cancer patients needs to be elucidated.

Interestingly, 5 tumor tissue samples were found to have EGFR mutations not present in plasma; while 1 plasma sample showed to have EGFR mutation not present in biopsy samples may reflect the limitation of cfDNA samples for analyzing the EGFR mutations when patients progressed from first-line to second-line TKI treatment. In addition to this, there could be two possible fundamental mechanisms for the limited sensitivity of cfDNA samples for EGFR mutation analysis. First is if the DNA has been derived from the inflamed cells or non-cancerous cells [22] and the second is if tumor cells carrying mutant DNA has not been entered the circulation [26] which may hinder the mutation detection in cfDNA samples.

Conclusion

The present study confirmed the possibility of evaluating EGFR mutations in plasma samples from patients with an advanced stage of lung cancer is practicable when tumor tissues are not available for NSCLC patients. Our results substantiate to explore liquid biopsy as a non-invasive technique for the detection of EGFR mutation which might help clinicians to select optimal therapy in patients with an advanced stage of lung cancer.

Acknowledgements

The study has been financially supported by The Gujarat Cancer & Research Institute/The Gujarat Cancer Society.

Funding

The Gujarat Cancer Society/The Gujarat Cancer & Research Institute (RE/74/MO/14).

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional review committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Ferlay J, Shin HR, Bray F, Forman D, Mathers C, Parkin DM. Estimates of worldwide burden of cancer in 2008: GLOBOCAN 2008. Int J Cancer. 2010;127:2893–2917. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Ervik M, Eser S, Mathers C, Rebelo M, et al. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int J Cancer. 2015;1(136):E359–E386. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Malik PS, Raina V. Lung cancer: prevalent trends and emerging concepts. Indian J Med Res. 2015;141:5–7. doi: 10.4103/0971-5916.154479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chung C. Tyrosine kinase inhibitors for epidermal growth factor receptor gene mutation–positive non-small cell lung cancers: an update for recent advances in therapeutics. J Oncol Pharm Pract. 2016;22:461–476. doi: 10.1177/1078155215577810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bethune G, Bethune D, Ridgway N, Xu Z. Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) in lung cancer: an overview and update. J Thorac Dis. 2010;2:48–51. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gazdar AF. Activating and resistance mutations of EGFR in non-small-cell lung cancer: role in clinical response to EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Oncogene. 2009;28:S24–S31. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Inamura K, Ninomiya H, Ishikawa Y, Matsubara O. Is the epidermal growth factor receptor status in lung cancers reflected in clinicopathologic features? Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2010;134:66–72. doi: 10.5858/2008-0586-RAR1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ohsaki Y, Tanno S, Fujita Y, Toyoshima E, Fujiuchi S, Nishigaki Y, et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor expression correlates with poor prognosis in non-small cell lung cancer patients with p53 overexpression. Oncol Rep. 2000;7:603–607. doi: 10.3892/or.7.3.603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marchetti A, Martella C, Felicioni L, Barassi F, Salvatore S, Chella A, et al. EGFR mutations in non–small-cell lung cancer: analysis of a large series of cases and development of a rapid and sensitive method for diagnostic screening with potential implications on pharmacologic treatment. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:857–865. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.08.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bartholomew C, Eastlake L, Dunn P, Yiannakis D. EGFR targeted therapy in lung cancer; an evolving story. Respir Med Case Rep. 2017;20:137–140. doi: 10.1016/j.rmcr.2017.01.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Douillard JY, Ostoros G, Cobo M, Ciuleanu T, Cole R, McWalter G, et al. Gefitinib treatment in EGFR mutated caucasian NSCLC: circulating-free tumor DNA as a surrogate for determination of EGFR status. J Thorac Oncol. 2014;9:1345–1353. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0000000000000263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oxnard GR, Thress KS, Alden RS, Lawrance R, Paweletz CP, Cantarini M, et al. Association between plasma genotyping and outcomes of treatment with Osimertinib (AZD9291) in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:3375–3382. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.66.7162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.O’Neill AC, Jagannathan JP, Ramaiya NH. Evolving cancer classification in the era of personalized medicine: a primer for radiologists. Korean J Radiol. 2017;18:6–17. doi: 10.3348/kjr.2017.18.1.6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tsao MS, Sakurada A, Cutz JC, Zhu CQ, Kamel-Reid S, Squire J, et al. Erlotinib in lung cancer-molecular and clinical predictors of outcome. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:133–144. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kimura H, Suminoe M, Kasahara K, Sone T, Araya T, Tamori S, et al. Evaluation of epidermal growth factor receptor mutation status in serum DNA as a predictor of response to gefitinib (IRESSA) Br J Cancer. 2007;97:778–784. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vallee A, Marcq M, Bizieux A, Kouri CE, Lacroix H, Bennouna J, et al. Plasma is a better source of tumor-derived circulating cell-free DNA than serum for the detection of EGFR alterations in lung tumor patients. Lung Cancer. 2013;82:373–374. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2013.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nishino M, Jackman DM, Hatabu H, Jänne PA, Johnson BE, Van den Abbeele AD. Imaging of lung cancer in the era of molecular medicine. Acad Radiol. 2011;18:424–436. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2010.10.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ishii H, Azuma K, Sakai K, Kawahara A, Yamada K, Tokito T, et al. Digital PCR analysis of plasma cell-free DNA for non-invasive detection of drug resistance mechanisms in EGFR mutant NSCLC: correlation with paired tumor samples. Oncotarget. 2015;6:30850–30858. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.5068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Seki Y, Fujiwara Y, Kohno T, Takai E, Sunami K, Goto Y, et al. Picoliter-droplet digital polymerase chain reaction-based analysis of cell-free plasma DNA to assess EGFR mutations in lung adenocarcinoma that confer resistance to tyrosine-kinase inhibitors. Oncologist. 2016;21:156–164. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2015-0288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee JY, Qing X, Xiumin W, Yali B, Chi S, Bak SH, et al. Longitudinal monitoring of EGFR mutations in plasma predicts outcomes of NSCLC patients treated with EGFR TKIs: Korean lung cancer consortium (KLCC-12-02) Oncotarget. 2016;7:6984–6993. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.6874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jahr S, Hentze H, Englisch S, Hardt D, Fackelmayer FO, Hesch RD, et al. DNA fragments in the blood plasma of cancer patients: quantitations and evidence for their origin from apoptotic and necrotic cells. Cancer Res. 2001;61:1659–1665. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bai H, Mao L, Wang HS, Zhao J, Yang L, An TT, et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor mutations in plasma DNA samples predict tumor response in Chinese patients with stages IIIB to IV non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:2653–2659. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.17.3930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim HR, Lee SY, Hyun DS, Lee MK, Lee HK, Choi CM, et al. Detection of EGFR mutations in circulating free DNA by PNA-mediated PCR clamping. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2013;32:50. doi: 10.1186/1756-9966-32-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Couraud S, Vaca-Paniagua F, Villar S, Oliver J, Schuster T, Blanché H, et al. Noninvasive diagnosis of actionable mutations by deep sequencing of circulating free DNA in lung cancer from never-smokers: a proof-of-concept study from BioCAST/IFCT-1002. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20:4613–4624. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-3063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang Y, Duan J, Chen H, Bai H, An T, Zhao J, et al. Analysis of EGFR mutation status in tissue and plasma for predicting response to EGFR-TKIs in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. Oncol Lett. 2017;13:2425–2431. doi: 10.3892/ol.2017.5740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mack PC, Holland WS, Burich RA, Sangha R, Solis LJ, Li Y, et al. EGFR mutations detected in plasma are associated with patient outcomes in erlotinib plus docetaxel-treated non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2009;4:1466–1472. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181bbf239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]