Abstract

Secreted protein acidic and rich in cysteines-like 1 (SPARCL1) is implicated in tumor progression and considered as a tumor suppressor. Aim of the study is to investigate the role of SPARCL1 in the regulation of tumor biology. SPARCL1 expression in human cervical cells was determined through western blot and RT-PCR. The effects of SPARCL1 overexpression on cell proliferation, migration and invasion were evaluated through CCK8 assay, colony formation assay, Wound healing assay and Transwell assay, respectively. The gain function of Secreted phosphor protein 1 (SPP1) was also evaluated in these cell functions. We observed that SPARCL1 expression at protein levels and transcription levels was lower in HeLa cells than that in Ect1/E6E7 cells. When SPARCL1 was overexpressed in HeLa cells, cell proliferation, migration and invasion were greatly repressed. Additionally, SPARCL1 overexpression markedly downregulated SPP1 expression at transcription levels. Mechanistical study revealed that SPP1 overexpression could greatly counteract the effects of SPARCL1 overexpression on the aforementioned cell processes and inhibit the phosphorylation of focal adhesion kinase (FAK) and extracellular regulated protein kinases (ERK). Our findings indicated that HeLa cells overexpressing SPARCL1 showed weaker abilities of proliferation, migration and invasion, and its effects could be neutralized by SPP1 overexpression possibly via FAK/ERK pathway. The relationship of SPARCL1 and SPP1 could help us to further understand the pathogenesis of cervical cancer and SPARCL1/SPP1 could be beneficial therapeutic targets in cervical cancer.

Keywords: SPARCL1, SPP1, Cervical cancer, FAK/ERK

Introduction

Cervical cancer is one of the common malignant tumors in the female reproductive system, characterized by high degree of malignancy, strong invasion, poor prognosis, etc. Recently, the incidence of cervical cancer has been increasing and trending younger with years (Braz et al. 2017). At present, the pathogenesis of cervical cancer is completely under-explored.

SPARCL1 is a member of the SPARC family, also known as Hevin Sparc-like 1, SC1, MAST9, RAGS-1, QR1 or ECM. All members of the SPARC family are secreted into the extracellular matrix and play different roles in growth and disease development (Bradshaw 2012). SPARCL1 gene was found to be closely related to tumorigenesis and considered as a potential tumor suppressor gene. SPARCL1 expression level in cervical cancer tissue and serum is lower than normal tissue, and it involves in the progression of cervical cancer (Wu et al. 2018).

SPP1, also known as osteopontin (OPN), is encoded by the SPPl gene on human chromosome 4q22.1, the inhibition of which could enhance the sensitivity of cervical cancer cells to cisplatin (Chen et al. (2019)). As a non-receptor tyrosine protein kinase in the cytoplasm, FAK participates in multiple signal transduction pathways and exerts a vital role in regulating cell proliferation, adhesion, migration and movement (Shanthi et al. 2014). A study showed that the strong proliferation, invasion and metastasis potentials of cervical cancer cells are the main factors leading to poor prognosis of patients with this disease (Liang et al. 2019; Zeng et al. 2019). Based on reviewed literature data, the study was designed to analyze the mechanism action of SPARCL1 in cervical cancer cells.

Method

Cell culture

Human papillomavirus-related endocervical adenocarcinoma (HeLa), Human papillomavirus-related cervical squamous cell carcinoma (SiHa, Ca-Ski), Cervical squamous cell carcinoma (c-33A) and Human immortalized squamous cells of human cervix (Ect1/E6E7), were purchased from Shanghai Institute of Cell Biology, Chinese Academy of Sciences. HeLa cells were cultured in DMEM/F12 medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum, as well as 100 × 103 U/L streptomycin and penicillin at 37 °C with CO2. Cells at logarithmic growth were taken and seeded into 6-well plates with 2 × 105 cells per well, and then cultured for 24 h. SPARCL1 overexpressing plasmids (OE-SPARCL1), SPP1 overexpressing plasmids (Ov-SPP1) or empty plasmids (Ov-NC) were transfected into HeLa cells using LipofectamineTM2000 for continuous culture of 24 h.

Western blot

The cells of each group were collected 24 h after transfection. Total protein was extracted from cells with total protein extraction kit, and its concentration was detected using Bradford method. Protein of 50 µg in each group was taken and underwent electrophoresis though sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE). The proteins were electrotransferred to PVDF membrane and sealed with skimmed milk powder for 60 min. Then, PVDF membrane was incubated the primary antibodies (SPARCL1, ab255597; MMP2, ab92536; MMP9, ab76003; FAK, ab40794; ERK, ab184699; GADPH, ab8245; England. And SSP1, CSB-MA069021A0m, Flarebio, Wuhan, China; and p-FAK, #8556; p-ERK, #4370. Cell Signaling Technology, USA) at 4 °Covernight. Subsequently, the incubation with secondary antibodies (ab7090, ab97040, Abcam, England) was performed at 37 °C for 2 h. ECL luminescent solution (Millipore) was added for color development, and images were collected by automatic electrophoresis gel imaging analyzer. Gray level analysis was performed by Image J software, and the absorbance ratio of the target protein to the internal reference was used to represent the relative protein content.

Real-time quantitative PCR

Cells were cultured for 48 h after transfection (5 × 103 cells). The total RNA in the cells was extracted using TRIzol (Invitrogen), and reverse transcribed into cDNA as template strand using first strand cDNA synthesis kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The relative expression of SPARCL1 mRNA was calculated using 2−ΔΔCt method.

CCK8 assay

Cells were digested by trypsin and seeded into 96-well plates with 2 × 104 cells in each well at 37 °C. CCK8 solution (10 µL, APExBIO, USA) was added to each hole. The absorbance at 450 nm was detected using a microplate reader (Bio TEX).

Colony formation assay

HeLa cells at logarithmic growth stage were seeded into 6-well plates with a concentration of 500 cells per well. Culture was terminated when cell colonies appeared. Cells were then fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 20 min and stained with 0.1% crystal violet. Then, cells were photographed in a light microscope.

Wound healing

HeLa cells at logarithmic growth stage were seeded into a 6-well culture dish (1 × 105 cells). After 24 h of transfection, cell scratches were made with 10 μL spear head perpendicular to the bottom of the hole. After washing with PBS for 3 times, the suspended cells were removed, and the same amount of serum-free medium was added. Photographs were taken and recorded under an inverted phase contrast microscope at 0 h and 24 h, respectively.

Transwell assay

After transfection, the cells of each group were cultured for 24 h. After digestion by trypsin, the cells were resuspended by serum-free medium, and the cell concentration was adjusted to 2 × 108/L. The 50 mg/L Matrigel was diluted at 1:8 ratio and spread on the upper chamber of Transwell chamber (Corning, USA). 200 µL cell suspension was added to upper chamber of Transwell while DMEM/F12 culture medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum was placed in the lower chamber. After 12 h of incubation, the scattered cells in the upper chamber were removed, washed with phosphate buffer saline (PBS) for 3 times, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 20 min, and then stained with crystal violet for 15 min. The cells were observed under an inverted microscope (Olympus).

Statistical analysis

The comparison of experimental data among different groups was performed by one-way analysis of variance, followed by comparison between two groups through Tukey’s test. Each experiment was repeated at least three times. P < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant. The experimental data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD).

Result

SPARCL1 suppressed proliferation of HeLa cells

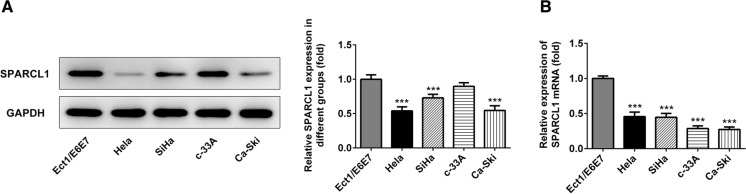

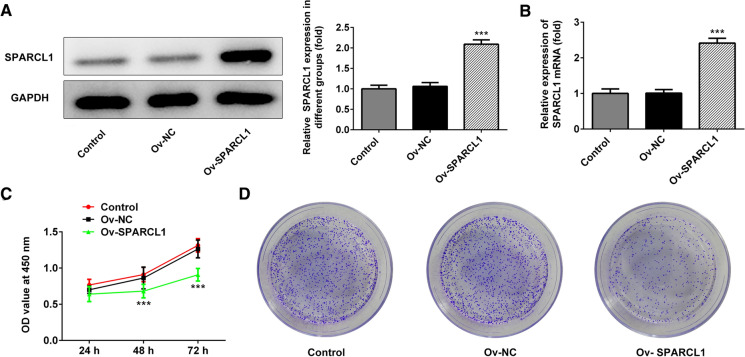

The expression of SPARCL1 in Ect1/E6E7, HeLa, SiHa, c-33A and Ca-Ski cells was detected by western blot and qRT-PCR (Fig. 1a, b). Compared with Ect1/E6E7 cells, SPARCL1 showed different degrees of down-regulation in HeLa, SiHa and Ca-Ski cell lines. To further test the role of SPARCL1 in cervical cancer, the induction of exogenous SPARCL1 into HeLa cells was conducted to analyze gain function of SPARCL1. Ov-SPARCL1 group exhibited significantly increased expression of SPARCL1 (Fig. 2a, b). In the CCK8 assay, we disclosed that the proliferation of HeLa cells overexpressing SPARCL1 was significantly slower than that of HeLa cells transfected with the empty plasmids (Fig. 2c), suggesting that the induction of exogenous SPARCL1 could reduce the proliferation ability. As shown in Fig. 2d, colony formation assay indicated that overexpression of SPARCL1 markedly decreased colony formation capability in HeLa cells.

Fig. 1.

a Expression of SPARCL1 in cervical carcinoma cell lines and normal cervical cell line. ***p < 0.001. The experimental data were presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). b The mRNA expression of SPARCL1 in cervical carcinoma cell line cells and normal cervical cell line

Fig. 2.

a and b Expression of SPARCL1 after transfection with SPARCL1 overexpressing plasmids into HeLa cells. c Effect of SPARCL1 overexpression on proliferation of HeLa cells. d The analysis of colony formation ability of HeLa cells overexpressing SPARCL1. ***p < 0.001. Bar chart was drawn using mean ± SD of data. Ov-SPARCL1 group mean that HeLa cells were treated with SPARCL1 overexpressing plasmids for 24 h. Ov-NC group indicated that HeLa cells underwent the transfection of empty plasmids for 24 h

SPARCL1 inhibited invasion and migration of HeLa cells

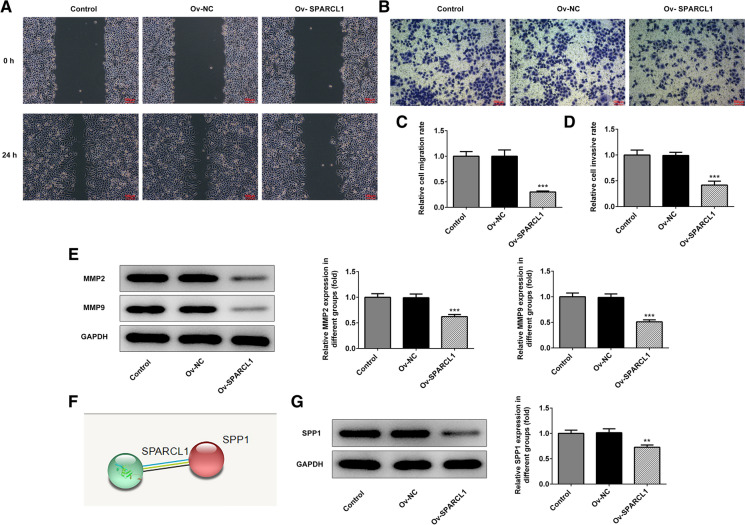

Next, we further detected the invasion and migration of HeLa cells through Wound healing and Transwell assays, respectively. The experimental results demonstrated that the relative migration rate and invasion rate of HeLa cells were overtly reduced after upregulation of SPARCL1 (Fig. 3a–d). In addition, total MMP2 and MMP9 proteins were detected to be reduced in HeLa cells with high SPARCL1 expression versus those with empty plasmids, indicating that the SPARCL1 promotion could reduce the invasion and migration of HeLa cells (Fig. 3e).

Fig. 3.

a SPARCL1 overexpression markedly decreased HeLa cells migration as detected by Wound healing assay. b SPARCL1 overexpression significantly reduced cell invasion as detected by Transwell assay. c and d The relative migration and invasion ratios of HeLa cells. e The protein levels of MMP2 and MMP9 were measured by western blot. f String database predicted an interaction between SPARCL1 and SPP1. g SPARCL1 overexpression significantly reduced SPP1 expression. **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. The data were indicated as mean ± SD. Ov-SPARCL1 group mean that HeLa cells were treated with SPARCL1 overexpressing plasmids for 24 h. Ov-NC group indicated that HeLa cells underwent the transfection of empty plasmids for 24 h

To further explore the regulatory role of SPARCL1 in cervical cancer, we searched on String database (https://string-db.org/), a database that stores data for interactions between proteins. It was viewed that SPARCL1 could interact with SPP1 (osteopontin) which is closely correlated with invasion and migration of cervical cancer (Chen et al. 2019; Song et al. 2009) (Fig. 3f). Then, the western blot assay validated that SPARCL1 overexpression significantly reduced the protein level of SPP1.

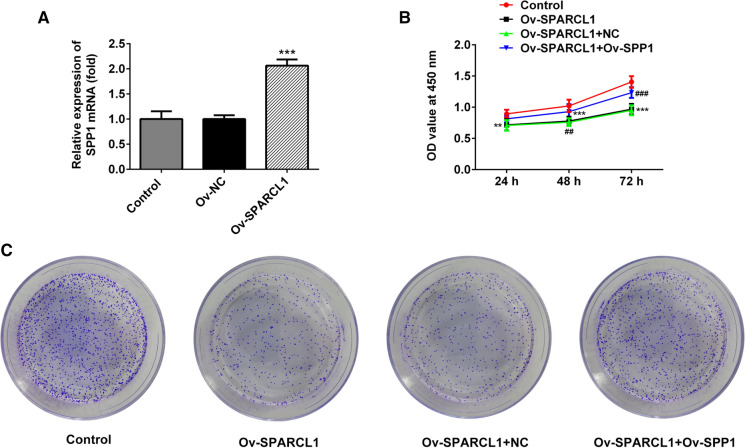

SPP1 blocked the inhibitory effect of SPARCL1 on proliferation

Next, we further explored the relationship of SPARCL1 and SPP1. SPARCL1 overexpressing plasmids were constructed and transfected into HeLa cells. After 24 h, SPP1 mRNA levels were significantly increased by about two times compared with empty plasmids group (Fig. 4a). To further confirm whether SPARCL1 regulated proliferation possibility by regulating SPP1, SPP1 overexpressing plasmids was also co-transfected into HeLa cells. After the co-transfection of SPARCL1 overexpressing plasmids and SPP1 overexpressing plasmids, cell proliferation and colonies were markedly increased than those under the single induction of SPARCL1 in HeLa cells.

Fig. 4.

a SPP1 mRNA levels were dramatically increased upon introduction of SPARCL1 overexpression plasmids, ***p < 0.001. b OD value was detected after 24, 48 and 72 h, respectively. c Colony numbers of HeLa cells were assessed through colony formation assay. **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 vs Control. ##p < 0.01 and ###p < 0.001 vs Ov-SPARCL1 + NC. Mean ± SD of data of each data was used to draw bar chart. Ov-SPARCL1 group mean that HeLa cells were treated with SPARCL1 overexpressing plasmids for 24 h. Ov-NC group indicated that HeLa cells underwent the transfection of empty plasmids for 24 h. Ov-SPARCL1 + Ov-SPP1 group mean that HeLa cells were co-transfected with both SPARCL1 overexpressing plasmids and SPP1 overexpressing plasmids

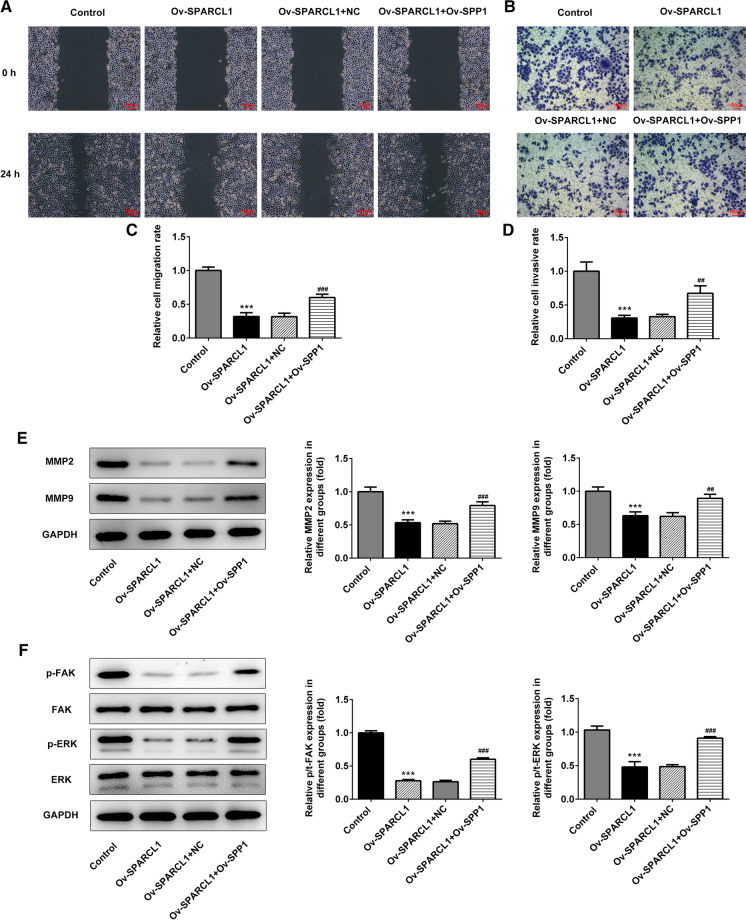

SPP1 blocked the inhibitory effects of SPARCL1 in cell migration and invasion

Further, the role of SPP1 in the regulation process of SPARCL1 overexpression in cell migration and invasion was investigate through inducting exogenous SPP1 expression in HeLa cells. SPP1 overexpression was found to markedly counteract the suppressive effects of SPARCL1 overexpression on HeLa cells migration and invasion (Fig. 5a–d). The protein expression levels of MMP-2 and MMP-9 in the HeLa cells under both overexpression of SPP1 and SPARCL1 were higher than those of SPARCL1 overexpression group, with statistically significant differences (Fig. 5e). Additionally, studies have shown that FAK signaling pathway can promote the secretion of MMP, especially MMP-2 and MMP-9, thus inducing angiogenesis and cell infiltration. We observed by western blot that there was no significant change in total FAK and ERK protein levels in HeLa cells overexpressing SPARCL1 relative to control HeLa cells, but the levels of phosphorylated FAK (pFAK) and phosphorylated ERK (pERK) was significantly decreased (Fig. 5f). However, SPP1 overexpression abolished the effects of SPARCL1 overexpression in suppressing FAK/ERK signal.

Fig. 5.

a The analysis of migration in HeLa cells through Wound healing assay. b The analysis of HeLa cell invasion through Transwell assay. c The relative migration ratio of HeLa cells. d The relative invasion ratio of HeLa cells. e The expression of MMP2 and MMP9 through western blot analysis. f The detection of FAK/ERK signals by western blot analysis. **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 vs Control. ##p < 0.01 and ###p < 0.001 vs Ov-SPARCL1 + NC. The data were shown as ± SD. Ov-SPARCL1 group mean that HeLa cells were treated with SPARCL1 overexpressing plasmids for 24 h. Ov-NC group indicated that HeLa cells underwent the transfection of empty plasmids for 24 h. Ov-SPARCL1 + Ov-SPP1 group mean that HeLa cells were co-transfected with both SPARCL1 overexpressing plasmids and SPP1 overexpressing plasmids

Discussion

In the present study, SPARCL1 was found to restrict HeLa cells proliferation, invasion and migration, and it negatively regulated SPP1 function and then affected FAK/ERK signaling. In regard to SPARCL1 function in cancer, it has been investigated to be a tumor suppressor and in close relation with tumor progression (Gagliardi et al. 2020,2017; Ma et al. 2018). By detecting SPARCL1 levels in cervical cancer cells, it was observed that SPARCL1 levels were markedly reduced in cancerous cells, especially in HeLa cells, as compared to Ect1/E6E7 cells. A review demonstrated that the expression of SPARCL1 presented downregulation in a wide range of cancers, such as non-small cell lung cancer, colon carcinomas and pancreatic cancer (Gagliardi et al. 2017), the reason of which may be related to the transacting factors binding to its exon 1 (Isler et al. 2001).

Further mechanistical study proved that SPARCL1 overexpression reduced SPP1 expression at transcription levels and its function could be mediated by SPP1 via FAK/ERK signaling. SPP1 in HeLa cells was found to regulate proliferation and apoptosis possibly through PI3K/Akt signal pathway (Chen et al. 2019). In this study, SPP1 overexpression blocked SPARCL1’s effects on HeLa cells proliferation, migration and invasion. These effects could be mediated by FAK/ERK pathway since the phosphorylation levels of FAK and ERK suppressed by SPARCL1 elevation were greatly increased after SPP1 overexpression. Additionally, FAK/ERK pathway is implicated in regulating the proliferation and invasion of cancer cells including nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells and ovarian cancer cells (Qiang et al. 2018; Zhang and Zhao 2017). Furthermore, we also observed that SPARCL1’s inhibition on MMP2 and MMP9 was blocked through the induction of exogenous SPP1 into HeLa cells. SPP1 has been reported to regulate MMP9 expression and then affect TGFβ processing (Kramerova et al. 2019). It was also previously reported that FAK/ERK/PI3K pathway could contribute to increased expression of pro-MMP-9 and MMP-2 activation in human cervical cancer cells SiHa, with fibronectin addition (Mitra et al. 2006). Based on these observations, we draw a conclusion that SPARCL1 suppressed proliferation and invasion of HeLa cells through SPP1 possibly via FAK/ERK pathway.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

All authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Shengpeng Zhang, Email: zshengpeng@yeah.net.

Fengge Zhang, Email: zshengpeng@yeah.net.

Limin Feng, Email: zshengpeng@yeah.net.

References

- Braz NS, Lorenzi NP, Sorpreso IC, Aguiar LM, Baracat EC, Soares-Júnior JM. The acceptability of vaginal smear self-collection for screening for cervical cancer: a systematic review. Clinics (Sao Paulo) 2017;72:183–187. doi: 10.6061/clinics/2017(03)09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradshaw AD. Diverse biological functions of the SPARC family of proteins. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2012;44:480–488. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2011.12.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu DM, Shi J, Liu T, Deng SH, Han R, Xu Y. Integrated analysis reveals down-regulation of SPARCL1 is correlated with cervical cancer development and progression. Cancer Biomark. 2018;21:355–365. doi: 10.3233/CBM-170501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Xiong D, Ye L, Yang H, Mei S, Wu J, Chen S, Mi R. SPP1 inhibition improves the cisplatin chemo-sensitivity of cervical cancer cell lines. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2019;83(4):603–613. doi: 10.1007/s00280-018-3759-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shanthi E, Krishna MH, Arunesh GM, Venkateswara Reddy K, Sooriya Kumar J, Viswanadhan VN. Focal adhesion kinase inhibitors in the treatment of metastatic cancer: a patent review. Expert Opin Ther Pat. 2014;24:1077–1100. doi: 10.1517/13543776.2014.948845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang Y, Zhang T, Shi M, Zhang S, Guo Y, Gao J, Yang X. Low expression of NCOA5 predicts poor prognosis in human cervical cancer and promotes proliferation, migration, and invasion of cervical cancer cell lines by regulating notch3 signaling pathway. J Cell Biochem. 2019;120:6237–6249. doi: 10.1002/jcb.27911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng J, Ma YX, Liu ZH, Zeng YL. LncRNA SNHG7 contributes to cell proliferation, invasion and prognosis of cervical cancer. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2019;23:9277–9285. doi: 10.26355/eurrev_201911_19420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song JY, Lee JK, Lee NW, Yeom BW, Kim SH, Lee KW. Osteopontin expression correlates with invasiveness in cervical cancer. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2009;49:434–438. doi: 10.1111/j.1479-828X.2009.01027.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gagliardi F, Narayanan A, Gallotti AL, Pieri V, Mazzoleni S, Cominelli M, Rezzola S, Corsini M, Brugnara G, Altabella L, Politi LS, Bacigaluppi M, Falini A, Castellano A, Ronca R, Poliani PL, Mortini P, Galli R. Enhanced SPARCL1 expression in cancer stem cells improves preclinical modeling of glioblastoma by promoting both tumor infiltration and angiogenesis. Neurobiol Dis. 2020;134:104705. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2019.104705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Y, Xu Y, Li L. SPARCL1 suppresses the proliferation and migration of human ovarian cancer cells via the MEK/ERK signaling. Exp Ther Med. 2018;16:3195–3201. doi: 10.3892/etm.2018.6575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gagliardi F, Narayanan A, Mortini P. SPARCL1 a novel player in cancer biology. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2017;109:63–68. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2016.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isler SG, Schenk S, Bendik I, Schraml P, Novotna H, Moch H, Sauter G, Ludwig CU. Genomic organization and chromosomal mapping of SPARC-like 1, a gene down regulated in cancers. Int J Oncol. 2001;18:521–526. doi: 10.3892/ijo.18.3.521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiang YY, Li CZ, Sun R, Zheng LS, Peng LX, Yang JP, Meng DF, Lang YH, Mei Y, Xie P, Xu L, Cao Y, Wei WW, Cao L, Hu H, Yang Q, Luo DH, Liang YY, Huang BJ, Qian CN. Along with its favorable prognostic role, CLCA2 inhibits growth and metastasis of nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells via inhibition of FAK/ERK signaling. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2018;37:34. doi: 10.1186/s13046-018-0692-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang M, Zhao L. CKAP2 promotes ovarian cancer proliferation and tumorigenesis through the FAK-ERK pathway. DNA Cell Biol. 2017;36:983–990. doi: 10.1089/dna.2017.3876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramerova I, Kumagai-Cresse C, Ermolova N, Mokhonova E, Marinov M, Capote J, Becerra D, Quattrocelli M, Crosbie RH, Welch E, McNally EM, Spencer MJ. Spp1 (osteopontin) promotes TGFβ processing in fibroblasts of dystrophin-deficient muscles through matrix metalloproteinases. Hum Mol Genet. 2019;28:3431–3442. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddz181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitra A, Chakrabarti J, Banerji A, Das S, Chatterjee A. Culture of human cervical cancer cells, SiHa, in the presence of fibronectin activates MMP-2. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2006;132:505–513. doi: 10.1007/s00432-006-0096-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]