Abstract

Background

The SARS-CoV-2 pandemic has caused mental stress in a number of ways: overstrain of the health care system, lockdown of the economy, restricted opportunities for interpersonal contact and excursions outside the home and workplace, and quarantine measures where necessary. In this article, we provide an overview of psychological distress in the current pandemic, identifying protective factors and risk factors.

Methods

The PubMed, PsycINFO, and Web of Science databases were systematically searched for relevant publications (1 January 2019 – 16 April 2020). This study was registered in OSF Registries (osf.io/34j8g). Data on mental stress and resilience in Germany were obtained from three surveys carried out on more than 1000 participants each in the framework of the COSMO study (24 March, 31 March, and 21 April 2020).

Results

18 studies from China and India, with a total of 79 664 participants, revealed increased stress in the general population, with manifestations of depression and anxiety, post-traumatic stress, and sleep disturbances. Stress was more marked among persons working in the health care sector. Risk factors for stress included patient contact, female sex, impaired health status, worry about family members and significant others, and poor sleep quality. Protective factors included being informed about the increasing number of persons who have recovered from COVID, social support, and a lower perceived infectious risk. The COSMO study, though based on an insufficiently representative population sample because of a low questionnaire return rate (<20%), revealed increased rates of despondency, loneliness, and hopelessness in the German population as compared to norm data, with no change in estimated resilience.

Conclusion

Stress factors associated with the current pandemic probably increase stress by causing anxiety and depression. Once the protective factors and risk factors have been identified, these can be used to develop psychosocial interventions. The informativeness of the results reported here is limited by the wide variety of instruments used to acquire data and by the insufficiently representative nature of the population samples.

The SARS-CoV-2 (severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2) pandemic has led to over 11.5 million confirmed cases and more than 540 000 deaths worldwide since the end of 2019/beginning of 2020) (as of 10.07.2020) (1, 2). A pandemic on this scale causes stress and mental health burdens in the population (3, 4). These include:

The fear that one/others might fall ill or die due to the virus

-

Psychological distress as a result of:

Isolation or quarantine measures

Financial difficulties (for example, due to job loss)

Responses to the pandemic on a state level (for example, school closures) (5).

In addition, healthcare workers are exposed to further stressors, such as increased risk of infection, the distress caused by triage decision-making, or stigmatization (5, 6).

The aim of this article is to provide an overview of studies from China and other countries on stress and mental burden in the general population as well as in healthcare workers. The results of three cross-sectional surveys conducted in the German population on psychological distress and resilience are also presented. By describing identified risk and protective factors, it is our intention to inform scientists and decision-makers in the healthcare system as to where psychosocial interventions to cope with the pandemic could be deployed.

Methods

Systematic literature analysis

The approach to the systematic literature analysis is described in detail in the eMethods and eBox. Parallel to this, a protocol was developed according to PRISMA guidelines (7) and registered in OSF Registries (osf.io/34j8g). The present analysis included studies that met the criteria listed in Table 1. A systematic literature search was conducted in the electronic databases PubMed, PsycINFO, and Web of Science (Core Collection) for publications in the period 01.01.2019 to 16.04.2020. Study selection and data extraction of included studies, as well as quality assessments using a modified version of the NIH-NHLBI instrument for cross-sectional studies and cohort studies (8), were carried out by two pairs of independent reviewers (NR, MB and NR, JSW). Any disagreement was resolved through discussion or by involving a third assessor (KL) at each stage of the literature analysis. There was high inter-rater reliability (κ1= 0.875; κ2= 1) on the title/abstract and full-text screening levels. The data extracted for each study included are presented in the eMethods. For five areas of psychological distress (anxiety and worry, depression, posttraumatic stress, sleep disorders, stress), the respective proportion of a sample showing elevated values (>cut-off) on an appropriate scale was extracted, if indicated. Comparisons with norm data were also taken into consideration for the data extraction. Due to the heterogeneity of the studies included, no quantitative synthesis of study results was carried out.

eBOX. Search strategies.

PubMed

| #1 | “Mental health”[mh] |

| #2 | “mental health”[tw] |

| #3 | psychological[tw] |

| #4 | Resilience, psychological[mh] |

| #5 | resilien*[tiab] or hardiness*[tiab] |

| #6 | “post-traumatic growth”[tiab] or “posttraumatic growth”[tiab] or “stress-related growth”[tiab] |

| #7 | “resilience factor*”[tiab] or “protective factor*”[tiab] or resource*[tiab] |

| #8 | burden[tiab] |

| #9 | #1 or #2 or #3 or #4 or #5 or #6 or #7 or #8 |

| #10 | SARS [tiab] OR influenza[tiab] or flu[tiab] or MERS[tiab] or ebola[tiab] |

| #11 | Pandemic[mh] or pandem*[tw] |

| #12 | coronavirus[tw] or COVID-19[tw] or 2019-nCoV[tw] or SARS-CoV-2[tw] |

| #13 | Quarantine[mh] or quarantine[tw] |

| #14 | #10 or #11 or #12 or #13 |

| #15 | #9 and #14 |

| #16 | “health personnel”[mh] |

| #17 | “health* personnel”[tiab] or “health* profession*”[tiab] or “health* worker*”[tiab] or “health* practitioner*”[tiab] or “health* provider*”[tiab] or “health* staff”[tiab] |

| #18 | “care personnel”[tiab] or “care profession*”[tiab] or “care worker*”[tiab] or “care practitioner*”[tiab] or “care provider*”[tiab] or “care staff”[tiab] |

| #19 | “intensive care”[tiab] or ICU[tiab] |

| #20 | emergency[tiab] |

| #21 | ambulance[tiab] or paramedic*[tiab] |

| #22 | “hospital personnel” [tiab] or “hospital staff” [tiab] |

| #23 | physician*[tiab] or doctor*[tiab] |

| #24 | nurse*[tiab] or “nursing staff”[tiab] |

| #25 | #16 or #17 or #18 or #19 or #20 or #21 or #22 or #23 or #24 |

| #26 | Patients[mh] or patients[tiab] |

| #27 | older[tiab] or geriatric[tiab] |

| #28 | #26 or #27 |

| #29 | “population health”[mh] |

| #30 | public[tiab] |

| #31 | society[tiab] or social[tiab] |

| #32 | community[tiab] |

| #33 | “general population”[tiab] |

| #34 | nationwide[tiab] |

| #35 | #29 or #30 or #31 or #32 or #33 or #34 |

| #36 | #25 or #28 or #35 |

| #37 | #15 and #36 |

PsycINFO

| S1 | MA Mental health |

| S2 | TX Mental Health |

| S3 | TX psychological |

| S4 | MA Resilience, psychological |

| S5 | TI resilien* OR AB resilien* OR TI hardiness* OR AB hardiness* |

| S6 | TI posttraumatic growth OR AB posttraumatic growth OR TI post-traumatic growth OR AB post-traumatic growth OR TI stress-related growth OR AB stress-related growth |

| S7 | TI resilience factor* OR AB resilience factor* OR TI protective factor* OR AB protective factor* OR TI resource* OR AB resource* |

| S8 | TI burden OR AB burden |

| S9 | S1 OR S2 OR S3 OR S4 OR S5 OR S6 OR S7 OR S8 |

| S10 | TI SARS OR AB SARS OR TI Influenza OR AB Influenza OR TI Flu OR AB Flu OR TI MERS OR AB MERS OR TI Ebola OR AB Ebola |

| S11 | MA pandemic OR TX pandem* |

| S12 | TX coronavirus OR TX COVID-19 OR TX 2019-nCoV OR TX SARS-CoV-2 |

| S13 | MA quarantine OR TX quarantine |

| S14 | S10 OR S11 OR S12 OR S13 |

| S15 | S9 AND S14 |

| S16 | MA health personnel |

| S17 | TI health* personnel OR AB health* personnel OR TI health* profession* OR AB health* profession* OR TI health* worker* OR AB health* worker* OR TI health* practitioner OR AB health* practitioner OR TI health* provider* OR AB health* provider* OR TI health* staff OR AB health* staff |

| S18 | TI care personnel OR AB care personnel OR TI care profession* OR AB care profession* OR TI care worker* OR AB care worker* OR TI care practitioner* OR AB care practitioner* OR TI care provider* OR AB care provider* OR TI care staff OR AB care staff |

| S19 | TI intensive care OR AB intensive care OR TI ICU OR AB ICU |

| S20 | TI emergency OR AB emergency |

| S21 | TI ambulance OR AB ambulance OR TI paramedic* OR AB paramedic* |

| S22 | TI hospital personnel OR AB hospital personnel OR TI hospital staff OR AB hospital staff |

| S23 | TI physician* OR AB physician* OR TI doctor* OR AB doctor* |

| S24 | TI nurse* OR AB nurse* OR TI nursing staff OR AB nursing staff |

| S25 | S16 OR S17 OR S18 OR S19 OR S20 OR S21 OR S22 OR S23 OR S24 |

| S26 | MA patients OR TI patients OR AB patients |

| S27 | TI older OR AB older OR TI geriatric OR AB geriatric |

| S28 | S26 OR S27 |

| S29 | MA population health |

| S30 | TI public OR AB public |

| S31 | TI society OR AB society OR TI social OR AB social |

| S32 | TI community OR AB community |

| S33 | TI general population OR AB general population |

| S34 | TI nationwide OR AB nationwide |

| S35 | S29 OR S30 OR S31 OR S32 OR S33 OR S34 |

| S36 | S25 OR S28 OR S35 |

| S37 | S15 AND S36 |

-

Web of Science (Core Collection)

# 36 #33 AND #13

Refined by: WEB OF SCIENCE CATEGORIES: (PUBLIC ENVIRONMENTAL OCCUPATIONAL HEALTH OR PSYCHOLOGY OR PSYCHOLOGY CLINICAL OR PRIMARY HEALTH CARE OR PSYCHIATRY OR NURSING OR PSYCHOLOGY MULTIDISCIPLINARY)

Indexes=SCI-EXPANDED, SSCI, A&HCI, CPCI-S, CPCI-SSH, BKCI-S, BKCI-SSH, ESCI, CCR-EXPANDED, IC Timespan=1990–2020

# 35 #33 AND #13

Refined by: WEB OF SCIENCE CATEGORIES: (INFECTIOUS DISEASES OR PUBLIC ENVIRONMENTAL OCCUPATIONAL HEALTH OR IMMUNOLOGY OR PSYCHOLOGY OR VIROLOGY OR PSYCHOLOGY CLINICAL OR PRIMARY HEALTH CARE OR PSYCHIATRY OR NURSING OR SOCIAL SCIENCES INTERDISCIPLINARY OR PSYCHOLOGY MULTIDISCIPLINARY OR SOCIAL WORK)

Indexes=SCI-EXPANDED, SSCI, A&HCI, CPCI-S, CPCI-SSH, BKCI-S, BKCI-SSH, ESCI, CCR-EXPANDED, IC Timespan=1990–2020

# 34 #33 AND #13

Indexes=SCI-EXPANDED, SSCI, A&HCI, CPCI-S, CPCI-SSH, BKCI-S, BKCI-SSH, ESCI, CCR-EXPANDED, IC Timespan=1990–2020

# 33 #32 OR #25 OR #22

Indexes=SCI-EXPANDED, SSCI, A&HCI, CPCI-S, CPCI-SSH, BKCI-S, BKCI-SSH, ESCI, CCR-EXPANDED, IC Timespan=1990–2020

# 32 #31 OR #30 OR #29 OR #28 OR #27 OR #26

Indexes=SCI-EXPANDED, SSCI, A&HCI, CPCI-S, CPCI-SSH, BKCI-S, BKCI-SSH, ESCI, CCR-EXPANDED, IC Timespan=1990–2020

# 31 TS=nationwide

Indexes=SCI-EXPANDED, SSCI, A&HCI, CPCI-S, CPCI-SSH, BKCI-S, BKCI-SSH, ESCI, CCR-EXPANDED, IC Timespan=1990–2020

# 30 TS=“general population”

Indexes=SCI-EXPANDED, SSCI, A&HCI, CPCI-S, CPCI-SSH, BKCI-S, BKCI-SSH, ESCI, CCR-EXPANDED, IC Timespan=1990–2020

# 29 TS=community

Indexes=SCI-EXPANDED, SSCI, A&HCI, CPCI-S, CPCI-SSH, BKCI-S, BKCI-SSH, ESCI, CCR-EXPANDED, IC Timespan=1990–2020

# 28 TS=(society or social)

Indexes=SCI-EXPANDED, SSCI, A&HCI, CPCI-S, CPCI-SSH, BKCI-S, BKCI-SSH, ESCI, CCR-EXPANDED, IC Timespan=1990–2020

# 27 TS=public

Indexes=SCI-EXPANDED, SSCI, A&HCI, CPCI-S, CPCI-SSH, BKCI-S, BKCI-SSH, ESCI, CCR-EXPANDED, IC Timespan=1990–2020

# 26 TS=“population health”

Indexes=SCI-EXPANDED, SSCI, A&HCI, CPCI-S, CPCI-SSH, BKCI-S, BKCI-SSH, ESCI, CCR-EXPANDED, IC Timespan=1990–2020

# 25 #24 OR #23

Indexes=SCI-EXPANDED, SSCI, A&HCI, CPCI-S, CPCI-SSH, BKCI-S, BKCI-SSH, ESCI, CCR-EXPANDED, IC Timespan=1990–2020

# 24 TS=(older or geriatric)

Indexes=SCI-EXPANDED, SSCI, A&HCI, CPCI-S, CPCI-SSH, BKCI-S, BKCI-SSH, ESCI, CCR-EXPANDED, IC Timespan=1990–2020

# 23 TS=patients

Indexes=SCI-EXPANDED, SSCI, A&HCI, CPCI-S, CPCI-SSH, BKCI-S, BKCI-SSH, ESCI, CCR-EXPANDED, IC Timespan=1990–2020

# 22 #21 OR #20 OR #19 OR #18 OR #17 OR #16 OR #15 OR #14

Indexes=SCI-EXPANDED, SSCI, A&HCI, CPCI-S, CPCI-SSH, BKCI-S, BKCI-SSH, ESCI, CCR-EXPANDED, IC Timespan=1990–2020

# 21 TS=(nurse* or “nursing staff”)

Indexes=SCI-EXPANDED, SSCI, A&HCI, CPCI-S, CPCI-SSH, BKCI-S, BKCI-SSH, ESCI, CCR-EXPANDED, IC Timespan=1990–2020

# 20 TS=(physician* or doctor*)

Indexes=SCI-EXPANDED, SSCI, A&HCI, CPCI-S, CPCI-SSH, BKCI-S, BKCI-SSH, ESCI, CCR-EXPANDED, IC Timespan=1990–2020

# 19 TS=(“hospital personnel” or “hospital staff”)

Indexes=SCI-EXPANDED, SSCI, A&HCI, CPCI-S, CPCI-SSH, BKCI-S, BKCI-SSH, ESCI, CCR-EXPANDED, IC Timespan=1990–2020

# 18 TS=(ambulance or paramedic*)

Indexes=SCI-EXPANDED, SSCI, A&HCI, CPCI-S, CPCI-SSH, BKCI-S, BKCI-SSH, ESCI, CCR-EXPANDED, IC Timespan=1990–2020

# 17 TS=emergency

Indexes=SCI-EXPANDED, SSCI, A&HCI, CPCI-S, CPCI-SSH, BKCI-S, BKCI-SSH, ESCI, CCR-EXPANDED, IC Timespan=1990–2020

# 16 TS=(“intensive care” or ICU)

Indexes=SCI-EXPANDED, SSCI, A&HCI, CPCI-S, CPCI-SSH, BKCI-S, BKCI-SSH, ESCI, CCR-EXPANDED, IC Timespan=1990–2020

# 15 TS=(“care personnel” or “care profession*” or “care worker*” or “care practitioner*” or “care provider*” or “care staff”)

Indexes=SCI-EXPANDED, SSCI, A&HCI, CPCI-S, CPCI-SSH, BKCI-S, BKCI-SSH, ESCI, CCR-EXPANDED, IC Timespan=1990–2020

# 14 TS=(“health* personnel” or “health* profession*” or “health* worker*” or “health* practitioner*” or “health* provider*” or “health* staff”)

Indexes=SCI-EXPANDED, SSCI, A&HCI, CPCI-S, CPCI-SSH, BKCI-S, BKCI-SSH, ESCI, CCR-EXPANDED, IC Timespan=1990–2020

# 13 #12 AND #7

Indexes=SCI-EXPANDED, SSCI, A&HCI, CPCI-S, CPCI-SSH, BKCI-S, BKCI-SSH, ESCI, CCR-EXPANDED, IC Timespan=1990–2020

# 12 #11 OR #10 OR #9 OR #8

Indexes=SCI-EXPANDED, SSCI, A&HCI, CPCI-S, CPCI-SSH, BKCI-S, BKCI-SSH, ESCI, CCR-EXPANDED, IC Timespan=1990–2020

# 11 TS=quarantine

Indexes=SCI-EXPANDED, SSCI, A&HCI, CPCI-S, CPCI-SSH, BKCI-S, BKCI-SSH, ESCI, CCR-EXPANDED, IC Timespan=1990–2020

# 10 TS=(coronavirus or COVID-19 or 2019-nCoV or SARS-CoV-2)

Indexes=SCI-EXPANDED, SSCI, A&HCI, CPCI-S, CPCI-SSH, BKCI-S, BKCI-SSH, ESCI, CCR-EXPANDED, IC Timespan=1990–2020

# 9 TS=pandem*

Indexes=SCI-EXPANDED, SSCI, A&HCI, CPCI-S, CPCI-SSH, BKCI-S, BKCI-SSH, ESCI, CCR-EXPANDED, IC Timespan=1990–2020

# 8 TS=(SARS or influenza or flu or MERS or ebola)

Indexes=SCI-EXPANDED, SSCI, A&HCI, CPCI-S, CPCI-SSH, BKCI-S, BKCI-SSH, ESCI, CCR-EXPANDED, IC Timespan=1990–2020

# 7 #6 OR #5 OR #4 OR #3 OR #2 OR #1

Indexes=SCI-EXPANDED, SSCI, A&HCI, CPCI-S, CPCI-SSH, BKCI-S, BKCI-SSH, ESCI, CCR-EXPANDED, IC Timespan=1990–2020

# 6 TS=burden

Indexes=SCI-EXPANDED, SSCI, A&HCI, CPCI-S, CPCI-SSH, BKCI-S, BKCI-SSH, ESCI, CCR-EXPANDED, IC Timespan=1990–2020

# 5 TS=(“resilience factor*” or “protective factor*” or resource*)

Indexes=SCI-EXPANDED, SSCI, A&HCI, CPCI-S, CPCI-SSH, BKCI-S, BKCI-SSH, ESCI, CCR-EXPANDED, IC Timespan=1990–2020

# 4 TS=(“post traumatic growth” or “posttraumatic growth” or “stress related growth”)

Indexes=SCI-EXPANDED, SSCI, A&HCI, CPCI-S, CPCI-SSH, BKCI-S, BKCI-SSH, ESCI, CCR-EXPANDED, IC Timespan=1990–2020

# 3 TS=(resilien* or hardiness*)

Indexes=SCI-EXPANDED, SSCI, A&HCI, CPCI-S, CPCI-SSH, BKCI-S, BKCI-SSH, ESCI, CCR-EXPANDED, IC Timespan=1990–2020

# 2 TS=psychological

Indexes=SCI-EXPANDED, SSCI, A&HCI, CPCI-S, CPCI-SSH, BKCI-S, BKCI-SSH, ESCI, CCR-EXPANDED, IC Timespan=1990–2020

# 1 TS=“mental health”

Indexes=SCI-EXPANDED, SSCI, A&HCI, CPCI-S, CPCI-SSH, BKCI-S, BKCI-SSH, ESCI, CCR-EXPANDED, IC Timespan=1990–2020

191916.04.202085716.04.202012616.04.2020190

Table 1. Selection criteria for the systematic literature analysis.

| Criterion | Description |

| Population | Inclucion: General population. healthcare workers (e.g.. physicians. nurses). irrespective of age and health status; exposure to SARS-CoV-2 pandemic; all countries Exclusion: COVID-19 patients or other patient groups; other infections (e.g.. MERS. SARS. Ebola. HIV. influenza) |

| Endpoints | Inclusion: Assessment of psychological distress (e.g.. anxiety and worry. depression. posttraumatic stress. sleep. stress) and/or assessment of protective factors. including resilience or risk factors Exclusion: no exclusion criteria |

| Study design | Inclusion: Questionnaire-based cross-sectional and longitudinal studies (survey-based studies) Exclusion: Interventional studies |

| Publication language | All |

| Publication formats | Inclusion: Original articles Exclusion: Other publication formats (e.g.. reviews. letters to the editor. comments) |

| Publication status | Inclusion: Peer-reviewed publications |

COVID-19. coronavirus disease 2019; HIV. human immunodeficiency virus infection; MERS. Middle East respiratory syndrome; SARS. severe acute respiratory syndrome

Data collection on psychomorbidity and resilience in Germany

The COVID-19 Snapshot Monitoring (COSMO) study (9, 10) monitored perception of the current SARS-CoV-2 outbreak in quota samples of an online panel at three measurement points:

24./25.03.2020, wave 4

31.03./01.04.2020, wave 5

21./22.04.2020, wave 8.

The quotas match the German population in terms of age, sex (crossed), and German federal state (uncrossed). Due to the response rates of 19% (wave 4), 14% (wave 5), and 15% (wave 8), the results are representative of the German population to only a limited extent. Psychological distress was assessed on the basis of five items for the period of the previous 7 days:

“I felt nervous, anxious, or on edge” (item 1, GAD-7, [11])

“I felt depressed” (item 6, ADS [12])

“I felt lonely” (item 14, ADS [12])

“I felt hopeful about the future” (item 8, ADS [12])

“Thoughts about my experiences during the Coronavirus pandemic caused me to have physical reactions, such as sweating, trouble breathing, nausea or a pounding heart” (item 19, IES-R [13]).

To estimate the reported overall psychological burden, the mean value of the five items was determined. Suicidal tendency was not assessed. In order to estimate fear of SARS-CoV-2, the mean value of nine items tailored to the situation were recorded. The subjective assessment of resilience was surveyed with the Brief Resilience Scale (BRS [14, 15]). The results of the COSMO study were compared with the norm data of the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Screener (GAD-7) (11), the German General Depression Scale (Allgemeine Depressionsskala, ADS) (12), and the Brief Resilience Scale (BRS) (14, 15) for the German population before the outbreak of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic.

Results

Systematic literature analysis

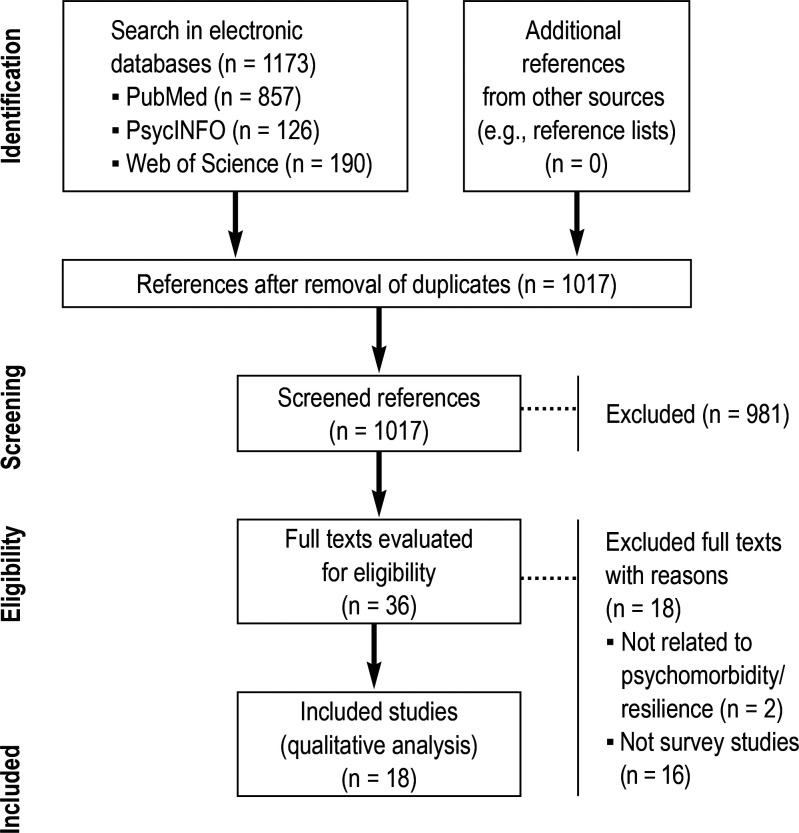

The literature search initially identified 1173 studies, of which n = 18 studies with i = 18 reported samples were included in the analysis according to the inclusion criteria (efigure).

eFigure.

Flow diagram on study selection (search period 01. 01. 2019 to 16. 04. 2020)

Table 2, etable 1, and etable 2 provide an overview of the included studies, their study populations, as well as the survey instruments and cut-off values used.

Table 2. Survey-based studies from China and India on the psychological effects of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic (as of 16.04.2020).

| Country | Participants; female (%); age (M ± SD) [alternative data] |

Subgroups | Anxiety and worry | Depression | Posttraumatic stress | Sleep | Stress/other outcomes | |

| General population | ||||||||

| Cao et al. (2020) (e16) |

China | 7143; 4975 (69.65%); n. a. |

n. a. | GAD-7 | n. a. | n. a. | n. a. | n. a. |

| Liu et al. (2020) (e7) |

China | 285; 155 (54.4%); n. a. [47.7% <35 years] |

n. a. | n. a. | n. a. | PCL-5 (higher than norm*1) | n. a. | n. a. |

| Qiu et al. (2020) (e4) |

China. Hong Kong. Macao. Taiwan | 52 730; 34 131 (64.73%); n. a. |

n. a. | n. a. | n. a. | n. a. | n. a. | CPDI |

| Roy et al. (2020) (e17) |

India | 662; 339 (51.2%); 29.09 ± 8.83 |

n. a. | SD | n. a. | n. a. | SD | n. a. |

| Wang C et al. (2020) (16) |

China | 1210; 814 (67.3%); n. a. [53.1% 21.4–30.8 years] |

n. a. | DASS-21 subscale on anxiety |

DASS-21 subscale on depression |

IES-R | n. a. | DASS-21 subscale on stress |

| Wang Y et al. (2020) (e18) |

China | 600; 333 (55.5%); 34 ± 12 |

n. a. | SAS | SDS | n. a. | n. a. | n. a. |

| Zhang Y et al. (2020) (e19) |

China | 263; 157 (60%); 37.7± 14.0 |

n. a. | n. a. | n. a. | IES | n. a. | n. a. |

| Healthcare workers | ||||||||

| Cai et al. (2020) (e1) |

China | 534; 367 (68.7%); 36.4 ± 16.18 years |

P (n = 233). NS (n = 248) |

SD | n. a. | n. a. | n. a. | n. a. |

| Huang JZ et. al. (2020) (e9) |

China | 230; 187 (81.30%); n. a. [53% 30–39 years] |

P (n = 70). NS (n = 160) |

SAS | n. a. | PTSD-SS | n. a. | n. a. |

| Kang et al. (2020) (e20) |

China | 994; 850 (85.5%); n. a. [63.4% ca. 30–40 years] |

P (n = 183). NS (n = 811) |

GAD-7 | PHQ-9 | IES-R | ISI | n. a. |

| Lai et al. (2020) (6) |

China | 1257; 964 (76.7%); n. a. [64.7% 26–40 years] |

P (n = 493). NS (n = 764) |

GAD-7 | PHQ-9 | IES-R | ISI | n. a. |

| Mo et al. (2020) (e2) |

China | 180; 162 (90%); 129 (71.7%); 32.71 ± 6.52 |

n. a. | SAS (higher than norm*2) |

n. a. | n. a. | n. a. | SOS |

| Xiao et al. (2020) (e3) |

China | 180; 129 (71.7%); 32.31±4.88 |

P (n = 82). NS (n = 98) |

SAS (higher than norm*3) |

n. a. | n. a. | PSQI | SASR; GSES; SSRS |

| Mixed groups | ||||||||

| Huang Y et al. (2020) (e6) |

China | 7236; 3952 (54.6%); 35.3 ± 5.6 |

HW (n = 2250) | GAD-7 (higher than norm*4) |

CES-D (higher than norm*5) |

n. a. | PSQI | n. a. |

| Li et al. (2020) (e8) |

China | 740; 128 (59.81%); 25 [IQR: 22–38.3] |

GP (n = 214). NS (n = 526) |

n. a. | n. a. | VTQ | n. a. | n. a. |

| Lu et al. (2020) (e21) |

China | 2299; 1785 (77.6%); n. a. [78% <40 years] |

HW (n = 2042). AS (n = 257) |

HAMA. NRS on fear |

HAMD | n. a. | n. a. | n. a. |

| Yuan et al. (2020) (e22) |

China | 939; 582 (61.98%); n. a. [71.5% 18–39 years] |

HW (n = 249). S (n = 312) |

n. a. | n. a. | n. a. | n. a. | n. a. |

| Zhang W et al. (2020) (e23) |

China | 2182; 1401 (64.2%); n. a. [96.3% 18–60 years] |

HW (n = 927). GP (n = 1255) |

GAD-2 | PHQ-2 | n. a. | ISI | SCL-90-R |

*1 Prevalence: 7 versus 3.7%

*2 M ± SD: 32.19 ± 7.56 versus 29.78 ± 0.46; t = 4.27; p <0.001

*3 M ± SD: 8.583 ± 4.567 versus 7 (SD n. a.)

*4 Prevalence: 35.1 versus 5.0%; *5 prevalence: 20.3 versus 3.6%

IQR. interquartile range. M. mean value; n. a.. not available; t. value of the t-test for independent samples; SD. standard deviation

Subgroups: GP. general population; P. physicians; HW. healthcare workers; NS. nursing staff; S. students; AS. administrative staff

Measurement tools: CES-D. Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale to measure depressive symptoms; CPDI. COVID-19 Peritraumatic Distress Index; DASS-21. Depression. Anxiety and Stress Scale; GAD-2. Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale-2 to measure symptoms of anxiety; GAD-7. Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale-7 to measure symptoms of anxiety; GSES. General Self-Efficacy Scale to measure self-efficacy; HAMA. Hamilton Anxiety Scale to measure symptoms of anxiety; HAMD. Hamilton Depression Scale to measure depressive symptoms; IES. Impact of Event Scale to measure posttraumatic stress symptoms; IES-R. Impact of Event Scale—Revised to measure posttraumatic stress symptoms; ISI. Insomnia Severity Index to measure sleep disorders; NRS. Numeric Rating Scale; PCL-5. Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist for DSM-5 for posttraumatic stress symptoms; PHQ-2. Personal Health Questionnaire-2 to measure depressive symptoms; PHQ-9. Personal Health Questionnaire-9 to measure depressive symptoms; PSQI. Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index to measure sleep quality; PTSD-SS. PTSD Self-rating Scale to measure posttraumatic stress symptoms; SAS. Self-Rating Anxiety Scale to measure anxiety symptoms; SASR. Stanford Acute Stress Reaction questionnaire to measure stress reactions; SCL-90-R. symptom checklist 90—Revised to measure psychological distress; SDS. Self-Rating Depression Scale; SD. self-developed questionnaire; SOS. Stress Overload Scale to measure stress; SSRS. Social Support Rate Scale to assess social support; VTQ:. Vicarious Traumatization Questionnaire to assess secondary traumatization. based. e.g.. on the TSIB (Traumatic Stress Institute Belief Scale). VTS (Vicarious Trauma Scale). and IES

eTable 1. Extraction table for survey studies on psychological effects of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic (as of April 16, 2020).

| Country; participants; female (%); age (M ± SD) [alternative information] | Subgroup; assessment; survey period | Assessment tools or questions asked | Psychological distress | Stress/ other outcomes | Moderating factors | ||||

| Anxiety, fear, worries | Depressive symptoms | Posttraumatic stress | Sleep-related symptoms | ||||||

| General Population | |||||||||

| Cao et al. (2020) (e16) | China; 7,143; 4,975 (69.65%); NR | Medical students from Changzhi Medical College; Internet, no details on recruitment, cross-sectional; NR | GAD-7 | 24.9% affected; 0.9% severe, 2.7% moderate, 21.3% mild symptoms | NR | NR | NR | NR | for anxiety: infection of loved ones (+); worries about economic impact of the epidemic (+); concerns about study related disadvantages (+); influence of the epidemic on daily life (+); stability of family income (–); living in a urban area (–); living with parents (–); social support (–) |

| Liu et al. (2020) (e7) | China; 285; 155 (54.4%); NR [47.7%<35] | Current (n=124) or previous (n=188) stay in Wuhan; internet, no details on recruitment; January 30 - February 08, 2020 | PCL-5, PSQI | NR | NR | 7% according to PCL-5 (higher than norm data1) | NR | NR | For PTSD: Female sex (+); Risk groups (+); no current / previous stay in Wuhan (–); poor subjective sleep quality (+); sleep latency (+) |

| Qiu et al. (2020) (e4) | China, Hong Kong, Taiwan, Macao; 52,730; 34,131 (64.73%), NR | GP; internet, recruitment with QR code via Siuvo Intelligent Psychological Assessment Platform, cross-sectional; January 31 – February 10, 2020 | CPDI | NR | NR | NR | NR | 35% CPDI>27 | for psychological distress: female (+); age < 18 (–); migrant workers (+); being from hubei (+) |

| Roy et al. (2020) (e17) | India; 662; 339 (51.2%); 29.09±8.83 | GP; internet, snowball sampling method via e-mail, WhatsApp, other social media, cross-sectional; March 22 – 24, 2020 | multiple-choice-questions on awareness, attitudes, fear | 82.2% preoccupations about COVID-19; 37.8 % hypochondriac fear | NR | NR | 12.5% sleep disorders due to worries | NR | NR |

| Wang, C. et al. (2020) (16) | China; 1,210; 814 (67.3%); NR [53.1% age 21.4-30.8] | GP; internet, via snowball sampling to students, cross-sectional; January 31 - February 2, 2020 | IES-R, DASS-21 | 28.8% >9 in DASS-21 anxiety subscale | 16.5% >12 in DASS-21 depression subscale | 53.8% > 33 im IES-R; M±SD: 32.98± 15.42 | NR | Stress: 8.1%>18 in DASS-21stress subscale | For PTSD: male sex (–); students (+); respiratory symptoms (+); chronic diseases (+); discontent with information about COVID-19 (+); concerns about children (+); hygiene behavior (–); For stress: students (+); reduced perceived health (+); chronic diseases (+); discontent with information on COVID-19 (+); information about increase in cured (–); no trust in the doctor (+); low perceived risk of infection (–); perceived risk of death from infection (+); concerns about family (+); hygiene behavior (–) For fear: students (+); doctor's visits (+); hospital stays (+); reduced perceived health (+); chronic diseases (+); contact to person with COVID-19 (+); no confidence in the doctor (+); low perceived risk (–) of infection; concerns about children (+); hygiene behavior (–) for depressive symptoms: low educational level (+); reduced perceived health (+); chronic diseases (+); discontent with information on COVID-19 (+); information about increase in the number of people cured (–); no trust in the doctor (+); hygiene behavior (–) |

| Wang, Y et al. (2020) (e18) | China; 600; 333 (55.5%); 34 ± 12 | GP; internet, no details on recruitment, cross-sectional; February 6 - 9, 2020; | SAS, SDS | 0.67% SAS> 59 (36.92 ± 7.33) | 2.83% SDS>62 (40.50 ± 11.31) | NR | NR | NR | for anxiety: female sex (+); age > 40 (+) |

| Zhang, Y. et al. (2020) (e19) | China; 263; 157 (60%); 37.7± 14.0 | GP from Liaoning; internet, recruitment via WeChat, cross-sectional; January 28 – 5, 2020 | i. a. IES | NR | NR | 7.6% IES > 25 (13.6±7.7) | NR | NR | for PTSS: (–) rest |

| Healthcare Workers | |||||||||

| Cai et al. (2020) (e1) | China; 534; 367 (68.7%); 36.4 (16.18) | physicians (n=233), nurses (n=248) in Hunan; no details on recruitment, cross-sectional; January –March, 2020 | Custom-built: emotions during COVID-19 outbreak, stressors, protective factors, coping and others | 40.6% > 1 (anxious+ nervous) | NR | NR | NR | NR | for stress: concerns about infecting family |

| Huang, JZ. et. al. (2020) (e9) | China; 230; 187 (81.30%); NR [53% age 30-39] | physicians (n=70), nurses (n=160) (all in frontline position); institutional survey, no details on recruitment, cross-sectional; February 7- 14, 2020 | SAS, PTSD-SS | 11.63% of the 43 men, 25.67% of the 187 women SAS>49; (together 23.04 %) |

NR | 18.60% of the 43 men, 29.41% der 187 women PTSD-SS>49; (together 27.39%) | NR | NR | for anxiety: male sex (–); medical profession (–); low professional position (+) for post-traumatic stress: male sex (–) |

| Kang et al. (2020) (e20) | China; 994; 850 (85.5%); NR [63.4% age 30-40] | physicians (n=183), nurses (n=811); interent, recruitment via Wenjuanxing, cross-sectional; January 29 - February 04, 2020 | PHQ-9, GAD-7, ISI, IES-R; K-means-clustering-method for all of the measuring tools > mental health | 22.4% with GAD-7 mean value 8.2; 6.2% with GAD-7-M 15.1 | 22.4% with PHQ-9 mean value 9; 6.2% PHQ-9-M 15.1 | 22.4% with IES-R-mean value 39.9; 6.2% with IES-R mean value 60.0 | 22.4% with ISI mean value 10.4; 6.2% with ISI mean value 15.6 | NR | For mental health: exposure to COVID-19 (+); use of psychoeducational materials (–) |

| Lai et al. (2020) (6) | China; 1,257; 964(76.7%); NR[64.7% age 26 - 40] | subgroups: nurses (n= 764), physicians (n=493), from Wuhan (n=760), direct contact with COVID-19 patients (n=522); no details on recruitment, cross-sectional; January 29 – March 1, 2020 | PHQ-9, GAD-7, ISI, IES | 44.6% GAD-7 > 6 | 50.4% PHQ-9 > 8 | 71.5% IES-R > 25 | 34% ISI > 14 | NR | for depressive symptoms: Nursing staff(+); female sex (+); work at secondary hospital(+); middle professional position(+); direct patient contact(+) for fear: female sex (+); middle professional position (+); work at secondary hospital (+); direct patient contact (+) for sleep-related symptoms: direct patient contact (+) for stress: female sex (+); middle professional position(+); direct patient contact (+); work outside Hubei (–) |

| Mo et al. (2020) (e2) | China; 180; 162 (90%); 129 (71.7%); 32.71 ± 6.52 | nurses from Guangxi in Wuhan; internet, via computer/ smartphone, QR-Code, cross-sectional; end of February, 2020 | SOS, SAS | SAS: M±SD 32.19±7.56 | NR | NR | NR | SOS: stress: 22.22%> 50; (M±SD 39.91±12.92) |

for stress: siblings (–); workload(+) anxiety (+); high professional qualification(+); poor sleep quality (+); severity of the patient's condition (+); lack of adaptation to daily diet (+) |

| Xiao et al. (2020) (e3) | China; 180; 129 (71.7%); 32.31±4.88 | physicians (n=82), nurses (n=98) from Wuhan; no details on recruitment, cross-sectional; January –February, 2020 | SAS, GSES, SASR, PSQI, SSRS | SAS: M±SD 55.256± 14.183 (SAS) |

NR | NR | PSQI: M±SD 8.583±4.567 (higher than norm data2) | stress: M±SD 77.589± 29.525 (SASR) self-efficacy: GSES: M±SD 2.267±0.767 social support: SSRS: M±SD 34.172 ± 10.263 |

for sleep-related symptoms: anxiety (+); stress (+); self-efficacy (–); for anxiety: social support (–); for stress: social support (–); anxiety (+) |

| Mixed Groups | |||||||||

| Huang, Y. et al. (2020) (e6) | China; 7,236; 3,952 (54.6%); 35.3 ± 5.6 | GP, subgroup HCW (n = 2,250); internet, recruitment via WeChat, cross-sectional; February 3 - 17, 2020 | GAD-7, CES-D, PSQI, knowledge about COVID-19 and time spent thinking about COVID-19 | 35.1% GAD-7 > 9 (higher than norm data3); healthcare workers 35.6% (34.9% = mean of the remaining) | 20.1% CES-D > 28 (higher than norm data); HCW 19.8% (GP 20.2% =mean of the remaining) | NR | 18.2% PSQI > 7; HCW 23.8% (GP 15.67% = mean of the remaining) |

NR | for depressive symptoms: age <35 (+); health profession+ >3h/d thinking about COVID-19(+) for sleep related symptoms: health profession(+); health profession+>3h/d thinking about COVID-19(+) |

| Li et al. (2020) (e8) | China; 740; 128 (59.81%); 25 [IQR: 22–38.3] | GP (n=214) + nurses (n= 526), contact with COVID-19 (n=234); App-based, recruitment via WeChat, cross-sectional; February 17 - 21, 2020 | Vicarious Traumatization Questionnaire | NR | NR | Vicarious Traumatization Questionnaire: Median (IQR) GP 75.5 (62–88.3), nurses with contact 64 (52–75), without contact 75.5 (63–92) | NR | NR | for vicarious traumatization: general population or nursing staff without direct contact with COVID-19 (+) |

| Lu et al. (2020) (e21) | China; 2,299; 1,785 (77.6%); NR [78% age <40] | HCW (n=2,042), administrative staff (n=257); internet, no details on recruitment, cross-sectional; February 25 – 26, 2020 | NRS on fear, HAMA, HAMD | HCW: 70.6%>3 in NRS on fear, 25.5% >6 in HAMA; administrative staff: 58.4%> 3 in NRS on fear; 18.7% >6 in HAMA | HCW: 12.1% >6 in HAMD; administrative staff: 8.2% >6 in HAMD |

NR | NR | NR | for fear: health professional (+); high risk contact (+); for depressive symptoms: high-risk contact (+) |

| Yuan et al. (2020) (e22) | China; 939; 582 (61.98%); NR [71.5% age 18-39] | HCW (n=249); students (n=312); internet, no details on recruitment, longitudinal; 2 assessments in February, 2020 | SRQ, PSQI | NR | NR | NR | NR (change in M of the PSQI-items: –0.148) | NR (SRQ: change in M of the emotional state: 0.392; M-change in somatic responses: 0.014) | NR |

| Zhang, W. et al. (2020) (e23) | China; 2,182; 1,401 (64.2%); NR [96.3% age 18-60] | HCW (n=927), GP (n=1,255); internet, recruitment via Wenjuanxing, cross-sectional; February 19 – March 6, 2020 | ISI, SCL-90-R, PHQ-4(GAD-2+PHQ-2) | 10.4% GAD-2>2; HCW 13%; GP 8.5% | 10.6% PHQ-2>2; HCW 12.2%; GP 9.5% | NR | 33.9% ISI>7 (9.5%>14); HCW: 38.4% (10.5%); GP 30.5% (8.8%) | somatization: 0.9% SCL-90-R subscore>2; HCW 1.6%, GP 0.4% Zwang: 3.5% SCL-90-R subscore>2; HCW 5.3%; GP 2.2% phobic anxiety: 2.9% SCL-90-R subscore>2; HCW 3.6%; GP 2.4% |

for anxiety: health profession (+); female sex (+); being married (+); risk of contact with COVID-19 patients in the hospital (+); organic diseases (+); for depressive symptoms: health profession (+); living in rural areas (+); living with family (+); organic diseases (+) for sleep related symptoms: health profession (+); living in rural areas (+); living with family (+); risk of contact with COVID-19 patients in the hospital (+); organic diseases (+) |

Abbreviations:

GP: general population; HCW: healthcare workers; M: mean value; NR: not reported; SD: standard deviation

(+): positive correlation; (-): negative correlation; CES-D: Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale to assess depressive symptoms; CPDI: COVID-19 Peritraumatic Distress Index; DASS-21: Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale; GAD-7: Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale-7 to assess generalized anxiety disorders; GSES: General Self-Efficacy Scale to assess self-efficacy; HAMA: Hamilton Anxiety Scale to assess anxiety symptoms; HAMD: Hamilton Depression Scale to assess depressive symptoms; IES-R: Impact of Event Scale - Revised to assess post-traumatic symptoms; ISI: Insomnia Severity Index to assess sleep disorders; NRS: Numeric Rating Scale; PCL-5: Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist for DSM-5 for post-traumatic stress symptoms; PCL-C: Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist- Civialians for posttraumatic stress symptoms; PHQ-4: Personal Health Questionnaire-4 to assess anxiety and depressive symptoms; PHQ-9: Personal Health Questionnaire 9 to assess depressive symptoms; PSQI: Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index to assess sleep quality; PTSD: PTSD-SS: PTSD Self-rating Scale to assess post-traumatic stress symptoms; SAS: Self-Rating Anxiety Scale for recording anxiety symptoms; SASR: Stanford Acute Stress Reaction Questionnaire to assess stress reactions; SCL-90-R: Symptom Checklist 90-Revised to assess mental stress; SDS: Self-Rating Depression Scale; SE: Self-developed questionnaire; SOS: Stress Overload Scale to assess stress; SRQ: Stress Response Questionnaire to assess emotional situation, somatic reactions and behavior; SSRS: Social Support Rate Scale to assess social support; Vicarious Traumatization Questionnaire to assess secondary traumatization, based on TSIB (Traumatic Stress Institute Belief Scale), VTS (Vicarious Trauma Scale) and IES

1 prevalence: 7% vs 3.7%

2 M ± SD: 32.19±7.56 vs 29.78±0.46; t=4.27; p<0.001

3 prevalence: 35.1% vs 5.0%

4 prevalence: 20.3% vs 3.6%

eTable 2. Cut-off values or measurement data on the studies included.

| Cut-off values for “abnormal”/reported measurements. scale span | |

| CES-D | Huang et al. (e6): >28 (norm population 3.6%). 0–60 |

| CPDI | Qiu et al. (e4): >27. 0–100 |

| DASS-21: subscale on depression | Wang et al. (16): >12. 0–42 |

| DASS-21: subscale on anxiety | Wang et al. (16): >9. 0–42 |

| DASS-21: Subscale on stress | Wang et al. (16): >18. 0–42 |

| GAD-2 | Zhang et al. (e23): >2; n. a. |

| GAD-7 | Huang et al. (e6): >9 (norm population 5.0%). 0–21; Lai et al. (6): >6. 0–21; Cao et al. (e16): n. a.. 0–21; Kang et al. (e20): M for clusters 0–21 |

| GSES | Xiao et al. (e3): M ± SD 10–40 |

| HAMA | Lu et al. (e21): >6. 0–56* (14 items with scaling 0–4) |

| HAMD | Lu et al. (e21): >6. 0–68* (17 items with scaling 0–4) |

| IES | Zhang et al. (e19): >25 (M ± SD). 0–75* (15 items with scaling 0–5) |

| IES-R | Lai et al. (6): >25. 0–88; Kang et al. (e20): M for clusters. 0–88; Wang. C. (16): >33. 0–23 (normal). 24–32 (mild). 33–36 (moderate). >37 (severe) |

| ISI | Lai et al. (6): >14. 0–28; Kang et al. (e20): M for clusters. 0–28; Zhang et al. (e23): >7. n. a. |

| NRS on fear | Lu et al. (e21): >3. 0–10; |

| PCL-5 | Liu et al. (e7): >1 in 1 criterion-B item each + 1 + criterion-C item + 2 criterion D items + 2 criterion-E items. as well as for single items: >1. 20 items in total with scaling 0–4 |

| PHQ-2 | Zhang et al. (e23): >2. n. a. |

| PHQ-9 | Lai et al. (6): >9. 0–27; Kang et al. (e20): M for clusters. 0–21 |

| PSQI | Huang et al. (e6): >7. 0–21; Liu et al. (e7): only four of the 19 items. each item assessed individually: poor or very poor subjective sleep quality. sleep latency >30 min. sleep disorders: yes. sleep duration >7 h; Xiao et al. (e3): M ± SD (norm data: 7). 0–21; Yuan et al. (e22): three modified items in the test. given as mean change. scaling –3 to 2 |

| PTSD-SS | Huang et al. (e9): >49 (norm data: 25.8%). n. a. |

| SAS | Mo et al. (e2): M ± SD (norm data 29.78 ± 0.46; t = 4.27. p <0.001). n. a..; xiao et al. (e3): m ± sd; wang et al. (e18): >59 (M ± SD). <50 = no symptoms; 50–59 = mild. 60–69 = moderate. >70 = severe; Huang et al. (e9): <50 = normal. 50–60 mild; 61–70 moderate >70 severe |

| SASR | Mo et al. (e2): M ± SD. 0–150 |

| SCL-90-R | Zhang et al. (e23): per subscore >2. scaling 0–4 |

| SDS | Wang et al. (e18): >62 (M ± SD). <53 = no symptoms. 53–62 = mild. 63–72 = moderate. >73 = severe |

| SD | Generally: ≥ moderate; Cai et al. (e1): >1 |

| SOS | Mo et al. (e2): >50 (M ± SD). 22–110 |

| SRQ | Yuan et al. (e22): given as mean change. scaling –3 to 2 |

| SSRS | Xiao et al. (e3): M ± SD. 7–56 |

| VTQ | Li et al. (e8): median (IQR). n. a. |

* Given only indirectly; IQR: interquartile range; M: mean value; n. a.: not available

Measurement tools: CES-D. Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale to measure depressive symptoms; CPDI. COVID-19 Peritraumatic Distress Index; DASS-21. Depression. Anxiety and Stress Scale; GAD-2. Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale-2 to measure symptoms of anxiety; GAD-7. Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale-7 to measure symptoms of anxiety; GSES. General Self-Efficacy Scale to measure self-efficacy; HAMA. Hamilton Anxiety Scale to measure symptoms of anxiety; HAMD. Hamilton Depression Scale to measure depressive symptoms; IES. Impact of Event Scale to measure posttraumatic stress symptoms; IES-R. Impact of Event Scale–Revised to measure posttraumatic stress symptoms; ISI. Insomnia Severity Index to measure sleep disorders; NRS. Numeric Rating Scale; PCL-5. Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist for DSM-5 for posttraumatic stress symptoms; PHQ-2. Personal Health Questionnaire-2 to measure depressive symptoms; PHQ-9. Personal Health Questionnaire 9 to measure depressive symptoms; PSQI. Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index to measure sleep quality; PTSD-SS. PTSD Self-rating Scale to measure posttraumatic stress symptoms; SAS. Self-Rating Anxiety Scale to measure anxiety symptoms; SASR. Stanford Acute Stress Reaction questionnaire to measure stress reactions; SCL-90-R. symptom checklist 90-Revised to measure psychological distress; SDS. Self-Rating Depression Scale; SD. self-developed questionnaire; SOS. Stress Overload Scale to measure stress; SRQ. Stress Response Questionnaire; SSRS. Social Support Rate Scale to assess social support; VTQ. Vicarious Traumatization Questionnaire to assess secondary traumatization. based. e.g.. on the TSIB (Traumatic Stress Institute Belief Scale). VTS (Vicarious Trauma Scale). and IES

In total, the following publications with 79 664 participants were taken into consideration:

16 nonrepresentative studies from China on psychological burden (data on diagnoses were not available) published between 06.03.2020 (first study: [16]) and 15.04.2020 (e1)

One study from India

A multinational study from China, Hong Kong, Taiwan, and Macao.

No European studies were available at the time of the literature search. Sample sizes ranged from 180 (e2, e3) to 52 730 (e4) participants (table 2). It was not possible to calculate average age or sex distribution due to lacking data in some studies (etable 1). The quality assessment rated nine of the 18 studies as poor, six as fair, and three as good (etable 3).

eTable 3. Quality assessment of the included studies.

| Study | 1. Clear research question | 2. Clearly defined sample? | 3. Participation rate >50%? | 4. Participants from the same or similar population? Prespecified inclusion criteria? | 5. Rationale for sample size. description of the power or variance/effect estimators? | 8. Clear definition of exposure (independent variable)? | 9. Consistency of exposure across all participants? | 11. Clearly defined. valid. reliable. and consistently used outcome measure across all participants? | Quality assessment | Comments |

| General population | ||||||||||

| Cao et al. (e16) |

Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | n. r. | Y | ++ | (b). (c) |

| Liu et al. (e7) |

Y | N | n. a. | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | + | (a). (e) |

| Qiu et al. (e4) |

Y | Y | n. a. | n. r. | N | Y | Y | N | + | (a). (d) |

| Roy et al. (e17) |

Y | N | n. a. | Y | N | Y | Y | N | + | (a). (d) |

| Wang C et al. (16) |

Y | Y | n. a. | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | ++ | (a) |

| Wang. Y et al. (e18) |

Y | Y | n. a. | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | ++ | (a). (e) |

| Zhang Y et al. (e19) |

Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | ++ | (a) |

| Healthcare workers | ||||||||||

| Cai et al. (e1) |

Y | Y | n. r. | n. r. | N | Y | n. r. | N | + | (a). (b). (d) |

| Huang JZ et al. (e9) |

Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | +++ | |

| Kang et al. (e20) |

Y | Y | n. r. | n. r. | N | Y | Y | Y | + | (a). (f) |

| Lai et al. (6) |

Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | +++ | |

| Mo et al. (e2) |

Y | Y | Y | n. r. | N | Y | n. r. | Y | + | (a). (b) |

| Xiao et al. (e3) |

Y | Y | Y | n. r. | N | Y | n. r. | Y | + | (b). (c) |

| Mixed groups | ||||||||||

| Huang Y et al. (e6) |

Y | Y | n. a. | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | ++ | (a) |

| Li et al. (e8) |

Y | N | n .a. | Y | N | Y | Y | N | + | (c). (e) |

| Lu et al. (e21) |

Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | +++ | |

| Yuan et al. (e22) |

Y | N | n. r. | n. r. | N | Y | Y | N | + | (b). (c). (e) |

| Zhang W et al. (e23) |

Y | Y | n. a. | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | ++ | (a). (c) |

+: Poor; ++: fair; +++: good; Y. yes; N. no; n. a.. not applicable; n. r.. not reported

(a) Selection bias/possible selection bias due to insufficient description of data collection

(b) No/insufficient details on the survey period

(c) No data on cut-off values and/or scale span to measure outcome(s)

(d) No validated method of measuring outcome(s)

(e) Insufficient description of the sample

(f) Insufficient reasoning given for the summary of outcomes

General population

Of the seven general population-based studies and the five conducted in mixed-population groups, seven studies (n = 16 113) reported data on the point prevalence of anxiety symptoms (1–82% of respondents), while five studies (n = 8308) recorded the prevalence of depressive symptoms (3–20%). Three studies (n = 1758) reported data on the presence of posttraumatic stress symptoms among study participants as percentages (7–54%), while three studies (n = 6903) reported on sleep disorders (13–31% of participants). One study (n = 1210) reported increased symptoms of stress in 8% of respondents. None of the studies recorded suicidal tendency. Prevalence figures were determined using the reported cut-off value for each study and instrument (etable 2).

Only two studies performed comparisons of the frequency of psychopathological symptoms with norm values in the general Chinese population before the outbreak of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic (i.e., prior to 20.01.2020, since this is the date on which human-to-human transmission became known [e5]) and in the absence of effects from other epidemic events. One of these studies showed increased levels of anxiety (an approximately seven-fold higher prevalence: 35.1 versus 5% [e6]) and increased levels of depression (a more than five-fold higher prevalence: 20.3 versus 3.6% [e6]), while another study showed increased posttraumatic stress symptoms (an almost two-fold higher prevalence: 7% versus 3.7% [e7]).

Healthcare workers

Of the six studies that investigated only healthcare workers and the five that studied the subgroup of healthcare workers as well as mixed population groups, seven studies (n = 8234) reported on the point prevalence of anxiety symptoms (13–70% of healthcare workers) and five studies (n = 7470) on the prevalence of depressive symptoms (12–50%). Three studies (n = 2481) reported data on the presence of posttraumatic stress symptoms among study participants as percentages (27–72 %), while four studies (n = 5428) reported on sleep disorders (24–38% of participants). One study (n = 927) reported symptoms of stress in 22% of respondents. Prevalence figures were determined using the reported cut-off value for each study and instrument (etable 2).

Only two studies compared the frequency of psychopathological symptoms (anxiety and sleep disorders, respectively) with norm values in the general population (comparisons with healthcare workers before the current SARS-CoV-2 pandemic were not available). One study revealed statistically but not clinically relevant levels of anxiety (mean value of the Self-Rating Anxiety Scale (SAS, scale span not given) 32.19 ± 7.56 versus 29.78 ± 0.46; t = 4.27; p ≪0.001 [e2]), while the other showed only a slight increase in sleep-related symptoms (mean value in the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI, scale span 0–21) 8.583 ± 4.567 versus 7 (standard deviation not reported, [e3]).

Table 3 and eTable 4 provide a summary of the protective factors and risk factors for psychomorbidity due to the COVID-19 pandemic from the 19 studies. Most studies identified the following parameters as risk factors:

Table 3. Risk factors and protective factors for psychomorbidity in the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic.

| Demographic variables | Occupational and workplace-related variables |

Personal variables |

Pandemic-specific variables | Information-/ communicationrelated variables | Disease-related variables | |

| Risk factors | ||||||

| Anxiety | Students (16); female sex (6, 18, e23); age >40 (e18); healthcare profession (e21, e23); married (e23) | Concern about academic disadvantages (e16); working in a secondary care hospital* (6); intermediate professional status (6); direct patient contact (6); high-risk contact (e21) | No confidence in their doctor's ability to diagnose/recognize COVID-19 (16) | Infection of loved ones (e16); concerns about economic effects (e16); concerns about children (16); risk of contact with COVID-19 patients (e23) | n. a. | Physician visits (16); hospital stays (16); poor self-rated health status (16); chronic diseases (16); organic diseases (e23) |

| Depression | Low educational level (16); age <35 (e6); nursing profession (6); female sex (6); healthcare profession (e23); rural areas (e23) | Working in a secondary care hospital* (6); intermediate professional status (6); direct patient contact (6); high-risk contact (e21) | No confidence in their doctor's ability to diagnose/recognize COVID-19 (16); living with family (e23) | Healthcare profession. >3 h/day thinking about COVID-19 (e6) | Dissatisfaction with amount of health information (16) | Poor self-rated health status (16); chronic diseases (16); organic diseases (e23) |

| PTSS | Female sex (e7) | n. a. | Poor sleep quality (e7); sleep latency (e7) | Concerns about children (16); contact with people with suspected COVID-19 (16); general population/nursing staff not in direct contact with COVID-19 (e8) | Dissatisfaction with amount of health information (16) | High-risk population for COVID-19 (e7); respiratory symptoms (16); chronic diseases (16) |

| Sleep disorders | Healthcare profession (e6, e23); rural areas (e23) | Direct patient contact (6) | Living with family (e23) | Healthcare profession + >3 h/day thinking about COVID-19 (e23) | n. a. | Organic diseases (e23) |

| Psychological distress in general | Female sex (e4); participants from Hubei (e4) | Migrant workers (e4) | n. a. | Exposure to COVID-19 (e20) | n. a. | n. a. |

| Stress | Students (16); female sex (6) | Intermediate professional status (6); direct patient contact (6); workload (e9); high professional qualification (e9); severity of patient condition (e9) | No confidence in their doctor's ability to diagnose/recognize COVID-19 (16); poor sleep quality (e2) | Concerns about the family (16, e1) | Dissatisfaction with amount of health information (16) | Poor self-rated health status (16); chronic diseases (16) |

| Protective factors | ||||||

| Factors for fear | Large city (e16); male sex (e9); medical profession (e9) | Social support (e3, e16) | Low professional status (e9) | Stable income (e16); living with parents (e16); precautionary/hygiene measures (16) | Low perceived risk of infection (16) | n. a. |

| Depression | n. a. | n. a. | n. a. | Precautionary/hygiene measures (16) | n. a. | Information on rise in recovery numbers (16) |

| PTSS | Not currently/previously in Wuhan (e7); male sex (16, e9) | n. a. | n. a. | Precautionary/hygiene measures (16); resting (e19) | n. a. | n. a. |

| Sleep disorders | n. a. | Self-efficacy (e3) | n. a. | n. a. | n. a. | n. a. |

| Psychological distress in general | Age <18 (e4) | n. a. | n. a. | n. a. | Use of psychoeducational materials (e20) | n. a. |

| Stress | Working outside Hubei (6); siblings (e2) | Social support (e3) | n. a. | Precautionary/hygiene measures (16) | Low perceived risk of infection (16) | Information on rise in recovery numbers (16) |

*Medium-sized hospital providing interregional care; n. a.: not available; PTSS. posttraumatic stress symptoms

eTable 4. Statistical information on risk factors and protective factors.

| Moderating factors | ||

| Significant | Non-significant | |

| General Population | ||

| Cao et al. (2020) (e16) |

For anxiety: (+) infection in loved ones (logistic regression; OR = 3.007; 95%-CI = 2.377 - 3.804; p<0.001) (+) concerns about economic impact of the epidemic (correlation analysis; r= 0.327; p < 0.001); (+) concerns about academic delays (correlation analysis; r = 0.315; p < 0.001); (+) influence of the epidemic on daily life (correlation analysis; r = 0.316; p < 0.001); (–) stability of family income (logistic regression; OR = 0.726; 95% CI = 0.645 - 0.817; p < 0.001); (–) living in a large city (logistic regression; OR = 0.810; 95% CI = 0.709 - 0.925; p=0.002); (–) living with parents (logistic regression; OR = 0.752; 95% CI = 0.596 - 0.950; p=0.017); (–) social support (correlation analysis; r = –0.151; p < 0.001) |

For anxiety: (0) region (Hubei/ north/south; univariate analysis; Kruskal-Wallis test: H=0.292; p= 0.864) (0) sex (univariate analysis; M comparison (Mann-Whitney U test): U=–0.805; p=0.421); (0) rural-urban residence (logistic regression: OR = 0.928; 95%-CI 0.803- 1.073; p= 0.310) |

| Liu et al. (2020) (e7) |

For posttraumatic stress symptoms: (+) female sex (f vs. m; hierarchical regression, step 2: β = 0.192; p< 0.001); (–) male sex (f. criterion B symptoms; m vs. w; Mann-Whitney U-test: U= –4.209; p<0.001); (–) male sex (f. Criterion D symptoms; m vs. w; Mann-Whitney U-test: U=–1.994; p<0.05); (–) male sex (f. Criterion E symptoms; m vs. w; Mann-Whitney U-test: U=–2.273; p<0.05) (–) no current stay in Wuhan (t-test: t= –2.210 p=0.028); (–) no previous stay in Wuhan (t-test: t= –2.077 p=0.039); (+) risk groups (general population/ HCW/near contact/ confirmed or suspected COVID-19 cases; hierarchical regression: β =0.153; P < 0.01); (+) poor subjective sleep quality (hierarchical regression; β= 0.312; p < 0.001); (+) sleep latency (hierarchical regression: β = 0.172; p < 0,01); |

For posttraumatic stress symptoms: (0) age (t-test: F/t =–0,924; p=0,356); (0) education level (t-test: F/t= 1.553; p=0.213) (0) sex (f. Criterion C symptoms; m vs. w; Mann-Whitney U test: U= –1.488; =0.112) |

| Qiu et al. (2020) (e4) |

For PCDI: (+) female sex (vs. male; Whitney-Mann test (M ±SD comparison): 24.87± 15.03 vs. 21.41±15.97; p<0.001); (–) age < 18 (m ±sd: 14.83±13.41 vs. 18-30 years 27.76±15.69 vs. >60 years 27.49±24.22); (0) education (n/a); (+) Migrant workers (PCDI-M±SD=31.89±23.51; F=1602.501; p<0.001); (+) participants from Hubei (PCDI-M ±SD: 30.94 (19.22), F=929.306; p<0.001); (0) Availability of local medical resources(NR); (0) Efficiency of the regional public health system (NR); (0) Prevention and control measures (NR) |

NR |

| Roy et al. (2020) (e17) | NR | NR |

| Wang, C. et al. (2020) (16) |

For posttraumatic stress symptoms: -regarding IES-R: (–) male sex (logistic regression: β =–0.20; 95%-CI –0.35 - –0.05; p<0.05); (+) students (logistic regression: β =0.20; 95%-CI 0.05-0.35; p<0.05); (–) highest education level: primary school (vs. doctorate; logistic; logistic regression: β =–1.07; 95%-CI –2.09- –0.06; p<0.05) (+) respiratory symptoms (e.g. rhinitis; logistic regression: β = 0.39; 0.20-0.58; p<0.001) (+) chronic diseases (logistic regression: β =0.29; 95%-CI 0.01-0.58; p<0.05); (+) discontent with the information available on COVID-19 (logistic regression: β =0.63; 95%-CI: 0.11-1.14; p<0.05); (+) concerns about children (logistic regression: β =0.25; 95%-CI 0.05-0.44; p<0.05); (–) hygiene behavior (e.g. washing hands after coughing; β = –0.47; 95%-CI: –0.77- –0.17; p<0.05); (–) feeling that too many unnecessary worries about COVID-19 are being worried about (always vs. never; logistic regression: β =–0.47; 95%-CI –0.69-0.25; p>0.05); (+) need for information on COVID-19 (e.g. recommendations for prevention; β =0.52; 95%-CI 0.23-0.81; p<0.001); for stress: -regarding DASS-21 stress subscale: (+) male sex (logistic regression: β = 0.10; 95%-CI: 0.02-0.19); (+) students (logistic regression: β = 0.11; 95%-CI: 0.02-0.19); (+) respiratory symptoms; (+) reduced perceived health (logistic regression: β = 0.45; 95%-CI: 0.02-0.88; p<0.05); (+) chronic diseases (logistic regression: β = 0.24; 95%-CI 0.07-0.41; p<0.01); (+) discontent with information on COVID-19 (logistic regression: β = 0.32; 95%-CI: 0.02-0.62; p<0.05) (-) Information on the increase in the number of people cured (logistic regression: β=–0.24; 95%-CI: –0.40-0.07; p<0.01) (+) no confidence in the doctor (logistic regression: β =1.18; 95%-CI 0.61-1.75; p<0.001); (–) low perceived risk of infection (logistic regression: β = –0.18; 95%-CI: –0.35- –0.01; p<0.05) (+) high perceived risk of death in case of infection (probable/very probable; logistic regression: β (95%-CI) =0.18 (0.02-0.34)/0.34 (0.01-0.68); p<0.05); (+) worries about family (logistic regression: β =0.50; 95%-CI 0.04- 0.96); (–) hygiene behavior (e.g. washing hands after coughing; logistic regression: β =–0.31; 95%-CI –0.49 - –0.13; p<0.05), for anxiety: (+) male sex (logistic regression: β = 0.19; 95%-CI: 0.05-0.33); (+) students (logistic regression: β = 0.16; 95%-CI: 0.02-0.30) (+) respiratory symptoms (e.g. rhinitis symptoms; logistic regression: β =0.46; 95%-CI 0.28-0.63; p<0.001); (+) visits to a doctor (in a hospital in the last 14d; logistic regression: β =0.38; 95%-CI: 0.02- 0.73); (+) hospital stays (in a hospital in the last 14d; logistic regression: β = 1.23; 95%-CI: 0.09-2.36) (+) reduced perceived health (logistic regression: β =0.90; 95%-CI:0.2-1.58) (+) chronic diseases (logistic regression: β =0.48; 95%-CI 0.22-0.75; p<0.001) (+) contact to person with mainly COVID-19 or infected materials (logistic regression: β=0.98; 95%-CI: 0.32-1.64; p<0.01); (+) Information source radio (logistic regression: β =2.67; 95%-CI 0.22-5.11; p<0.05); (+) no confidence in the doctor (logistic regression: β=1.86; 95%-CI 0.96-2.76; p<0.001); (–) low perceived risk of infection (logistic regression: β=–0.36; 95%-CI –0.63-–0.09; p<0.05) (+) worries about children (logistic regression: β=0.24; 95%-CI 0.07- 0.42; p<0.01); (–) hygiene behaviour (e.g. washing hands after coughing; logistic regression: β =–0.63; 95%-CI –0.91- –0.35; p<0.001); (–) need for regular updates on the current situation regarding COVID-19 (logistic regression: β =–0.62; 95%-CI –1.00-–0.24; p<0.01); (–) need for information on the availability and effectiveness of drugs and vaccinations against COVID-19 (logistic regression: β =–0.63; 95%-CI –0.99-–0.26; p<0.01); (–) need for up-to-date information on the number of infected persons and their stay (logistic regression: β =–0.30; 95%-CI –0.57-–0.02; p<0.01); (–) need for updates on transmission routes of COVID-19 (logistic regression: β =–0.39; 95%-CI –0.77-–0.02); p<0.05) for depressive symptoms: (+) male sex (logistic regression: β = 0.12; 95%-CI 0.01-0.23); (+) low education level (no degree vs. doctorate; logistic regression: β = 1.81; 95%-CI: 0.46-3.16; p<0.001); (+) respiratory symptoms (e.g. persistent fever: β = 0.98; 95%-CI 0.23-1.72; p<0.05) (+) reduced perceived health (poor or very poor/ average vs. good or very good; logistic regression: β (95%-CI)=0.65 (0.10-1.20); p<0.05/ 0.26 (0.15-0.38); p<0.001); (+) chronic diseases (logistic regression: β =0.38; 0.17-0.59; p<0.001) (+) close contact with confirmed COVID-19 patient (logistic regression: β =0.97; 95%-CI 0.06-1.88; p>0.05); (+) close contact with person with mainly COVID-19 or infected materials (logistic regression: β =0.81; 95%-CI 0.29-1.34; p<0.01) (+) discontent with information about COVID-19 (logistic regression: β = 0.43; 95%-CI 0.04-0.81; p<0.05); (-) information about increase in number of cured patients (logistic regression: β =-0.24; 95%-CI -0.45 --0.03; p<0.05); (+) information source radio (logistic regression: β = 2.67; 95%-CI 0.70-4.63; p<0.01); (+) no confidence in the doctor (logistic regression: β = 1.66; 95%-CI 0.94-2.38; p<0.001); (+) high perceived risk of death (vs. I don't know; logistic regression: β = 0.49; 95%-CI 0.07-0.92; p>0.05); (-) hygiene behavior (e.g. avoidance of sharing chopsticks; logistic regression: β =-0.31; 95%-CI -0.46--0.15; p<0.001); (+) feeling that too many unnecessary worries are being made about COVID-19 (mostly vs. never; logistic regression: β =0.20; 95%-CI 0.003-0.39; p<0.05); (-) need for information on availability and effectiveness of drugs and vaccinations against COVID-19 (logistic regression: β =-0.35; 95%-CI -0.65--0.06; p>0.05); |