Abstract

Aim

This study described the development, and pilot evaluation, of the Implementing Pediatric Advance Care Planning Toolkit (IMPACT).

Methods

Key elements of paediatric advance care planning (ACP) were defined using a systematic review, a survey of 168 paediatricians and qualitative studies of 13 children with life‐limiting conditions, 20 parents and 18 paediatricians. Participants were purposively recruited from six Dutch university hospitals during September 2016 and November 2018. Key elements were translated into intervention components guided by theory. The acceptability of the content was evaluated by a qualitative pilot study during February and September 2019. This focused on 27 children with life‐limiting conditions from hospitals, a hospice and home care, together with 41 parents, 11 physicians and seven nurses who cared for them.

Results

IMPACT provided a holistic, caring approach to ACP, gave children a voice and cared for their parents. It provided information on ACP for families and clinicians, manuals to structure ACP conversations and training for clinicians in communication skills and supportive attitudes. The 53 pilot study participants felt that IMPACT was appropriate for paediatric ACP.

Conclusion

IMPACT was an appropriate intervention that supported a holistic approach towards paediatric ACP, focused on the child's perspective and provided care for their parents.

Keywords: advance care planning, care goals, communication, decision‐making, life‐limiting conditions

Abbreviations

- ACP

advance care planning

Key notes.

This multi‐centre Dutch study described the development, and pilot evaluation, of the Implementing Pediatric Advance Care Planning Toolkit (IMPACT).

The methods included a systematic review, a survey of paediatricians and qualitative studies of children with life‐limiting conditions, their parents and the clinicians who treated them.

IMPACT was valued as an appropriate intervention that supported a holistic approach that focused on the child's perspective and provided care for their parents.

1. INTRODUCTION

The number of children and adolescents living with life‐limiting conditions has increased due to medical and technological advances. 1 These are conditions where there are no curative treatment options left or where a cure might be possible, but could still lead to a premature death. 1 The importance of communicating with children and their parents about care options is widely acknowledged. Advance care planning (ACP) is a valuable communication strategy that aligns future medical care with individual values and preferences, in a timely manner, before the end of life. 2

Although medical associations have emphasised the importance of ACP for children with life‐limiting conditions, standard ACP approaches in paediatrics have been scarce. 3 , 4 Evidence suggests that families and clinicians value the concept of ACP, even earlier in disease trajectories than is normal practice. 5 , 6 However, more than 70% of paediatric clinicians reported ACP discussions happened infrequently and too late. 6 , 7 Barriers to ACP in paediatrics have included the fear of causing emotional distress in families and difficulties identifying the right time to start. 6 , 7 , 8

A growing number of programmes that support the implementation of ACP have been reported in palliative care. 4 These interventions have mainly focused on adults and might need adjustment for use in paediatrics. This is because of: the stage of the child's development, the involvement of the parents, the diverse disease trajectories and the specific needs of paediatric end‐of‐life care. In addition, existing ACP programmes often consist of complex interventions with multiple, interacting, components. This makes adapting for a paediatric setting difficult. Furthermore, detailed descriptions of these complex interventions are lacking in the literature, hindering their use in other contexts. 9

The few ACP interventions that have been adapted for use in paediatrics focus mainly on specific patient populations. These include adolescents and young adults with cancer and patients living with acquired immune deficiency syndrome. 10 , 11 , 12 The focus of these studies, on adolescents and their end‐of‐life preferences, might hinder both their earlier use in disease trajectories and their use with younger children and their parents. In addition to evidence‐based approaches, there are also practice‐based initiatives funded by governments or healthcare institutions. 13 However, the evidence and rationale for these programmes are often unclear, limiting their use in the research and development of ACP. A comprehensive, evidence‐based intervention to facilitate ACP for children with life‐limiting conditions in general, and their families, both early and later in disease trajectories, has been lacking. Therefore, the Implementing Pediatric Advance Care Planning Toolkit (IMPACT) research project was initiated to facilitate ACP for children with life‐limiting conditions and their families, starting shortly after diagnosis and continuing until the end of life. The aims of this study were to describe the developmental process and content of IMPACT so that users could understand the rationale of the intervention and report first impressions of stakeholders using IMPACT.

2. METHODS

2.1. Study design

The Framework for the Development and Evaluation of Complex Interventions, which was designed by the Medical Research Council, was used to structure the study design in five steps (Table 1). 14 These steps integrated evidence from literature, consultation with 28 international experts in paediatric palliative care and the findings from sub‐studies performed by the research team within this project. The sub‐studies included a systematic review of interventions which guided ACP conversations 15 and a cross‐sectional survey of paediatricians’ experiences with ACP. 6 They also carried out qualitative interviews with parents, 16 children and clinicians about their perspectives of ACP. The findings from these sub‐studies were considered in relation to existing theoretical concepts. This resulted in a tentative model for paediatric ACP and a logic model for the intervention. 17 This showed how the components of the intervention linked to underlying theories and anticipated outcomes. Subsequently, these insights were translated into the specific content of IMPACT. A prototype consisting of all the intervention materials was discussed with a multidisciplinary team of 12 experts, comprising clinicians, researchers and representatives from patients’ associations. The intervention was adjusted by linguistic experts and read by the family of a seriously ill child to make sure it was clear. Lastly, the acceptability of the content of the intervention was evaluated with stakeholders as part of a larger qualitative study about the early experiences with IMPACT.

Table 1.

Overview of the steps in the developmental and pilot phase

| Developmental phase |

| Step 1. Identifying the evidence base |

| Step 2. Exploring stakeholders’ perspectives |

| Step 3. Creating a theoretical framework |

|

| Step 4. Modelling the intervention |

|

| Pilot phase |

| Step 5. Fine‐tuning the intervention materials based on a pilot study |

|

2.2. Study population

This study focused on Dutch‐speaking children with life‐limiting conditions under the age of 18, their parents and clinicians. Participants in the sub‐studies of the developmental phase were purposefully recruited from six paediatric university hospitals during September 2016 and November 2018. The survey comprised 168 paediatricians, caring for children with life‐limiting conditions. 6 Individual interviews were conducted with 18 paediatricians caring for children with life‐limiting conditions in order to gain a deeper insight into their perspectives of ACP. A qualitative interview study analysed the perspectives on ACP of 20 parents of children with life‐limiting conditions, including 10 bereaved parents. 16 The perspectives that IMPACT provided on children living with a life‐limiting condition were explored at the start of the pilot study. Of the 13 children, 11 participated in focus group interviews and two children participated in individual interviews. The children had diverse medical backgrounds and were aged 11 to 18 years. Two children were siblings of a child with a life‐limiting condition. Table S1 provides an overview of the participants’ characteristics.

The pilot study participants were purposefully recruited from paediatric university hospitals, a hospice and a home care, during February and September 2019. The IMPACT training was attended by 11 physicians and seven nurses, experienced in the care for children with life‐limiting conditions. Subsequently, these clinicians invited the parents of children with life‐limiting conditions to participate in the study. Some of the children were invited to participate, depending on their age and mental state. The study comprised 25 children with life‐limiting conditions, aged six months to 18 years and two patients who reached adulthood, but were still receiving paediatric care due to severe cognitive impairment and grow retardation. The pilot study comprised 26 mothers, 15 fathers and five children. Table S2 provides an overview of the participants’ characteristics.

The research ethics committee of the University Medical Center Utrecht decided that the qualitative studies in the developmental phase and pilot phase were exempt from review under the Medical Research Involving Humans Act (27 September 2017, reference number 17‐662/C, and 14 November 2018, reference number 18‐770/C). All participants provided written informed consent.

2.3. Data collection and analysis

The data collection and analysis yielded several strategies due to the study design, including different sub‐studies. The survey study was based on an online questionnaire, and descriptive statistics were reported. 6 The qualitative studies of the development, and the pilot phase, were based on individual or focus group interviews. These interviews were audio‐recorded and transcribed verbatim. A thematic analysis was performed. The results of the sub‐studies were presented as narrative summaries that followed the five steps of the study design (Table 1). 18

3. RESULTS

3.1. Step one: the evidence on key paediatric ACP elements

Since a specific definition of ACP in paediatrics was lacking, the European Association for Palliative Care definition was used to formulate the basic key elements. 2 It was seen as a communication process to enable patients to define their preferences and goals for care. It also enabled them to discuss these preferences with their families and the healthcare professionals caring for them and to document, and review these, if appropriate. Although this international definition focused on competent adults, the key elements of ACP that was proposed by this definition were applicable in paediatrics as well. The systematic review of interventions to support ACP conversations revealed four phases: preparation, initiation, exploration and action. 15 A list of the topics to be addressed in each phase was extracted. These included living with illness, living a good life, preferences for care and treatment, perspectives on the end of life and attitudes to decision‐making. 15 Topics specific to paediatric ACP were added after consulting experts. These included the child's identity, parenting and family life. 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 Both the findings from the systematic review 15 and expert consultation emphasised the need for clinician training in communication strategies in order to use any ACP conversation guide adequately. Table 2 illustrates the potential for intervention using elements of paediatric ACP derived from the current evidence.

Table 2.

The key elements identified and the potential intervention building blocks of advance care planning (ACP) derived from current evidence and stakeholders’ perspectives

| Identified key elements | Potential intervention building blocks |

|---|---|

| Step 1. Identifying the evidence base | |

| ACP is defined as a process to discover, discuss and document preferences and goals for future care 2 |

|

| A framework for ACP conversations consists of preparation, initiation, exploration and action 15 |

|

| In ACP, exploring the perspectives of the child and family on living with illness and living a good life is essential 14 |

|

| Communication training is needed to implement ACP adequately 15 |

|

| Step 2. Exploring stakeholders’ perspectives | |

| Education on the holistic approach of ACP is needed 2 , 6 , 16 |

|

| Attention to the voice of the child is needed in ACP 6 , 16 |

|

| An attitude of caring is needed in ACP 16 |

|

3.2. Step two: key paediatric ACP elements from the stakeholders’ perspectives

The survey study evaluated the stakeholders’ views of ACP from the perspective of paediatricians. 6 These, together with the qualitative research of the parents of children with life‐limiting conditions, 16 the children themselves and the clinicians who cared for children with life‐limiting conditions, revealed three additional key elements for paediatric ACP (Table 2).

Firstly, education is required about the holistic nature of ACP. The sub‐studies showed that paediatricians talk about medical themes relating to ACP rather than exploring individual family values. 6 Parents wanted paediatricians to explore what their lives were like from a psychological, social and spiritual point of view. 16

Secondly, the paediatricians, parents and children all emphasised the importance of the child's perspective. 16 However, the paediatricians who took part in the qualitative interviews reported challenging experiences when trying to approach children and communicate adequately with them. Parents saw themselves as the best advocates for their child, yet they struggled to define their child's best interests. 16 Strategies to elicit the voice of the child are needed, either through direct communication with the child or by trying to understand the child's perspective.Thirdly, during the qualitative studies, both the paediatricians and parents expressed the need for a caring attitude when sharing future perspectives. Paediatricians needed to feel confident asking families about sensitive themes. Parents needed genuine attention for their challenging situation. They also stated that their paediatrician's acknowledgement of their child as an individual, and their tasks and expertise as parents, would be a precondition for sharing their deepest thoughts regarding their child's future. 16

3.3. Step three: a theoretical framework

A few of the ACP interventions evaluated by our systematic review relied on a clear theoretical background. 15 Behavioural theories were most commonly used as underlying concepts. 15 The representational approach of patient education explains how exploring patients’ perspectives, and tailoring information to them, leads to highly patient‐specific processes. 24 Therefore, we concluded that IMPACT should explore the child's and family's experiences and perspectives. It should also guide professionals on when, and how, to provide the family with tailored information during a conversation. Behavioural change theory helps us to understand that the attitudes of both families and clinicians regarding ACP can entail different stages of change, which may influence their level of engagement. 25

Steps one and two demonstrated the need for a holistic approach and for attention to be paid to the challenges facing families. Therefore, theories about parental coping when caring for a child with a life‐limiting condition were used to give insight into the needs of this specific population. The dual process of coping with bereavement theory shows that elements that focus on both loss and restoration are needed to cope with loss. 26 , 27 This theory can be helpful in designing interventions that support a caring attitude and include conversation topics that focus on joy and hopes, as well as on fears, worries and worst‐case scenarios.

Research into the role of prognostic disclosure indicates that providing such information with sensitivity and realism makes the parent‐clinician relationship a source of hope and can help parents endure difficult medical scenarios. 28 Therefore, intervention components need to encourage parents and clinicians to address expectations for the future and explore perspectives on worst‐case scenarios.

Concepts about parenting roles provided a theoretical foundation for understanding that parents need to feel acknowledged in their challenging role regarding their seriously ill child. 20 , 23 Parents aim to control symptoms and disease, create a life worth living for their child and maintain family balance. These aims may, in turn, inform parents’ values and preferences for care and treatment and should therefore be explored in conversations about future care. 20

The aforementioned theories all relate to the overarching conceptual model of person‐centred care. Here, the patient has an active, central role in decision‐making and organising their health care with clinicians, and ultimately, this helps the patient lead a meaningful life. 29 ACP can support this person‐centred care.

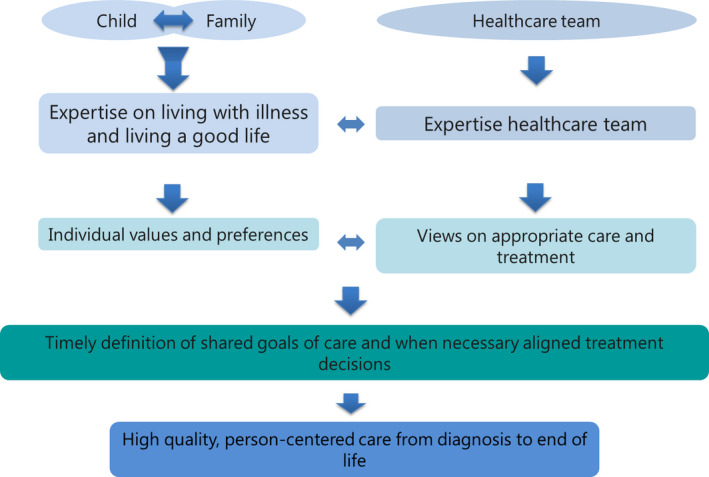

These concepts are reflected in a model for paediatric ACP, which aims to combine the lived experiences and expertise of children and their families with the expertise of the healthcare team (Figure 1). Through mutual identification and sharing perspectives, shared care goals can be achieved and, when appropriate, treatment decisions aligned to provide high‐quality, person‐centred care from diagnosis to the end of life.

Figure 1.

Model of paediatric advance care planning

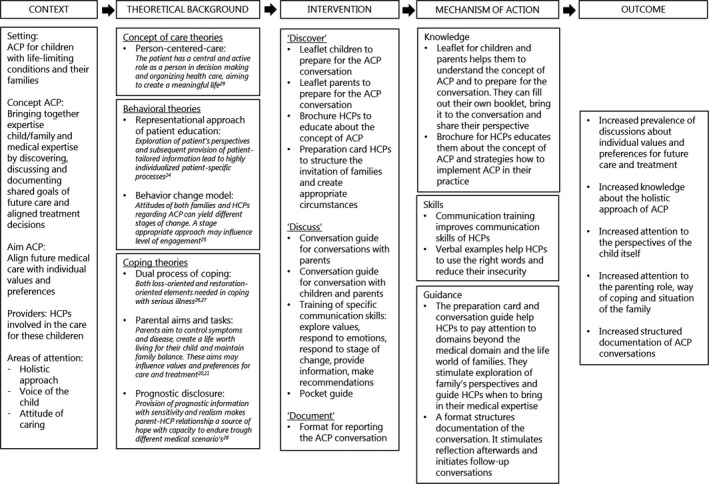

The logic model illustrates how the key elements identified in steps one and two are linked to the underlying theories described in step three (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Logic model of IMPACT

3.4. Step four: the intervention design

Specific intervention components and their intended outcomes were defined according to the logic model (Figure 2). The intervention components are described inTable 3. 30 These consist of a toolkit for clinicians and families and training for clinicians. The toolkit includes information leaflets about the concept of ACP in order to prepare clinicians and families for an ACP conversation. Conversation guides support the exploration of the perspectives of the child and family members related to psychological, social and spiritual domains, rather than just the physical one. The topics stimulate a conversation about the perspectives of the child, and parents, on living with illness, living a good life and care and treatment preferences. The preparatory materials and the conversation guide include specific questions for children as a means of involving them in the discussion. Besides the exploration of the inner perspectives of family members, an information booklet for clinicians also provides guidance on how to integrate their expertise into a conversation without undermining the family's perspectives. The conversation guide integrates individual perspectives on the care goals by a process of shared decision‐making. The structure of this guide is presented as a single conversation, yet multiple conversations might be needed to discuss all the steps, especially when there are distinctive perspectives within a family or between the family and clinician.

Table 3.

Description of the characteristics of IMPACT a

| Dimension | Description |

|---|---|

| Mode | Face‐to‐face advance care planning (ACP) conversations |

| Materials |

|

| Location | At home, inpatient or outpatient department |

| Schedule | The conversation guide is designed so that it can be used for a one‐off conversation or split up into multiple conversations, depending on the needs of the child and family |

| Scripting | The conversation guide structures the conversation and provides verbal examples for every part of the conversation. Verbal examples need to be adapted to the child's age and the family's circumstances |

| Participants’ characteristics | Children living with life‐limiting conditions, their parents and families |

| Sensitivity to participants’ characteristics | Information leaflets are tailored to children with life‐limiting conditions aged 10 y and above and parents of children with life‐limiting conditions of all ages |

| Interventionist characteristics |

|

| Adaptability |

|

| Treatment implementation |

|

Table based on taxonomy of Schulz. 30

An ACP training session was developed as part of IMPACT in collaboration with communication experts (Wilde Kastanje Training and Education, the Netherlands) (Table 4). The training focused on developing an attitude of open communication. It also taught specific ACP communication skills, such as exploring values, responding to emotions and strategies to achieve a shared point of view on care goals. 31

Table 4.

Description of IMPACT training

| Dimension | Description |

|---|---|

| Schedule | Two‐day training, four to eight weeks apart |

| Trainers | Clinicians with expertise in the field of advance care planning (ACP) and professional communication trainers/actors |

| Participants | Paediatricians, nurses, social workers, general practitioners and children's life therapists |

| Preparation | Reading the materials of IMPACT |

| Content day 1 |

|

| Content day 2 |

|

The I‐You‐We model (Wilde Kastanje Training and Education, the Netherlands) is a conversation metaphor that supports clinicians in exploring a family's perspective (You‐position), shares the clinician's own expertise (I‐position) and works towards a shared goal of care (We‐position). By explicitly, both verbally and non‐verbally, distinguishing the family's perspectives from the clinician's perspectives, and accepting any differences in insights, it is more likely a shared care goal will be reached in an ongoing conversation (WE‐position).

3.5. Step five: pilot evaluation

During the interviews with clinicians, parents and children, to evaluate their experiences with IMPACT, all groups reported appreciation of the materials and found them applicable to paediatrics as illustrated by direct quotes (Table S3). Participants perceived that all of the themes mentioned in the IMPACT materials were appropriate for discussions with children and their families. Families valued the attention for their experiences and life views beyond the medical domain. Parents reported that they would recommend the information leaflet to other parents. One mother suggested that a question could be added to the information leaflet for parents about the meaning of the serious illness to the family. Clinicians confirmed that the materials were useful in their daily practice, during their conversations with families and when educating their peers. Some clinicians mentioned that the exploratory phase of the conversation guide could be more succinct and these suggestions were adopted in the final version.

During the focus group interviews at the end of the developmental phase, children suggested changing the order of themes in their version of the information leaflet. They felt it inappropriate for them to talk about hopes and dreams after discussing death and dying, and the order was changed as a result of their comments. Children stated that they valued questions about their hopes and dreams, even if they knew, based on their prognosis, that those wishes might never become true based on the prognosis of the disease. Therefore, the conversation guide includes questions about wishes for their later life, although clinicians need to adapt these questions to the specific context of the child. Children varied in their perspectives on the relevance of questions about death and dying. Some considered these questions relevant, while others felt that death and dying did not need to be mentioned explicitly in the leaflet. However, the questions were not removed from the leaflet. It turned out that, in the pilot phase, children were able to share their perspectives on death and dying if they wanted to. Reading the topic in the leaflet stimulated children to share their preferences about whether or not they wanted to talk about death and dying during the ACP conversation itself.

All of the final IMPACT materials are available online in Dutch and English at: www.kinderpalliatief.nl/impact

4. DISCUSSION

This study describes the development and evaluation of IMPACT. This paediatric ACP intervention consists of materials to prepare clinicians, children with life‐limiting conditions and their parents for ACP conversations. It also helps to guide and document them. The materials incorporate a holistic person‐centred approach, stimulate the exploration of the voice of the child and support a caring attitude during the ACP process. Clinicians and families using IMPACT found the materials helpful, applicable to their lives and practice and successful in addressing appropriate themes. Some adjustments in language and layout were made, based on the pilot study.

Our intervention differs from other paediatric ACP approaches in some aspects. Whereas most interventions are tailored to specific diseases or population age, 4 our intervention is intended to be used in paediatrics in general. Existing approaches have focused on preferences for end of life, yet the intention of ACP, according to current definitions, is to initiate ACP early in a disease trajectory. 2 IMPACT is not primarily focused on the end of life and can be used at earlier phases of the disease trajectory. A strong focus on the end of life might function as a barrier to clinicians initiating ACP due the fear of distressing families and taking away hope. 8 Therefore, in line with the philosophy of palliative care, IMPACT invites clinicians and families to address both views on living well in the context of a life‐limiting condition, as well as views on what is important to them if death is imminent. This gradual approach leaves space for hope as well as a consideration of the future, with a realistic and appropriate understanding of the disease trajectory.

During the developmental process, we noticed that the clinician‐patient relationship plays an important role in ACP, both in creating a caring attitude and guaranteeing that the preferences and care goals identified are taken into account. This might be easier when both a primary responsible clinician and the family are involved in ACP. Therefore, our clinician‐based intervention differs from facilitator‐based ACP approaches.

The strength of the study was the thorough developmental process. Clinicians, children with life‐limiting conditions and parents, were all involved during the entire process. This encouraged researchers to stay close to clinical practice and facilitated further implementation of the intervention. By exploring the perspectives of stakeholders, needs in the field could be addressed, increasing the relevance of the intervention for current daily practice. The intervention components were supported by a rationale for acting in a certain way, based on underlying theoretical concepts. This was meant to help identify essential components of the interventions and to help explain the rationale of the intervention to potential users.

A limitation of the study was that system factors were not integrated into the developmental process or the intervention. The intervention is aimed at individual clinicians and families, instead of healthcare institutions. This means that well‐known barriers to ACP, such as lack of time and finances, systematic identification of eligible patients and standardised approaches for filing ACP documents in electronic medical records, were not addressed by the intervention. This might limit the implementation of the intervention in daily practice as it relies on the intrinsic motivation of individual clinicians to use it. However, the toolkit might be a good starting point for healthcare institutions to develop a standardised ACP approach. Other limitations of the study were that the stakeholders involved in the developmental process and the participants of the pilot study were mainly highly educated people with an open attitude towards ACP. This might have positively skewed their perspectives. The children included had varying diseases, prognoses and were in different stages of disease, which might result in different needs. A limitation of the study is that we could not specify the child's disease progression. That means we could not specify whether the perspectives, as presented by families, corresponded to a position early or later in a disease trajectory. We collected data about the time since diagnosis, but this did not reflect the stage of disease, its burden or length of time until end of life. We translated the perspectives of parents and children into a general approach, but it would be valuable to evaluate whether the individual needs of specific groups were sufficiently addressed by this approach or whether specific groups need a more tailored approach. Currently, the intervention does not include items for children adjusted for age and development, nor does it include items that are tailored to populations with language barriers or cultural differences. Developing components to serve these populations might positively influence the broader application of the intervention. Another limitation of this study is that the qualitative pilot study, as described above, only evaluated experiences with the intervention materials. Ongoing research is needed to identify whether the intervention contributes to the intended outcomes in daily practice and whether the key elements exert their effect, as was hypothesised in the underlying theoretical concept. 14

5. CONCLUSION

A theory and evidence‐based paediatric ACP intervention were developed and tailored to key elements of practice. It provided support materials and clinician training about the concept of ACP, providing strategies on how to address the voice of the child and how to convey to a caring attitude to families throughout their child's illness. A detailed description of the developmental process and open access to all the intervention's materials will support further research and implementation in daily practice.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Supporting information

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank all the families and clinicians who took part, the staff who recruited them, Wilde Kastanje for their collaboration and Tony Sheldon for his language editing services.

Fahner J, Rietjens J, van der Heide A, Milota M, van Delden J, Kars M. Evaluation showed that stakeholders valued the support provided by the Implementing Pediatric Advance Care Planning Toolkit. Acta Paediatr. 2021;110:237–246. 10.1111/apa.15370

REFERENCES

- 1. Fraser ALK, Miller M, Hain R, et al. Rising national prevalence of life‐limiting conditions in children in England. Pediatrics. 2012;129(4):e923‐e929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Rietjens JAC, Sudore PRL, Connolly M, et al. Review definition and recommendations for advance care planning: an international consensus supported by the european association for palliative care. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18(9):e543‐e551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lotz JD, Jox RJ, Borasio GD, Führer M. Pediatric advance care planning: a systematic review. Pediatrics. 2013;131(3):e873‐e880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Myers J, Cosby R, Gzik D, et al. Provider tools for advance care planning and goals of care discussion : a systematic review. Am J Hosp Palliat Med. 2018;35(8):1123‐1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. DeCourcey DD, Silverman M, Oladunjoye A, Wolfe J. Advance care planning and parent‐reported end‐of‐life outcomes in children, adolescents, and young adults with complex chronic conditions. Crit Care Med. 2019;47(1):101‐108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Fahner JC, Rietjens JAC, van der Heide A, van Delden JJM, Kars MC. Survey of paediatricians caring for children with life‐limiting conditions found that they were involved in advance care planning. Acta Paediatr. 2019;00:1‐8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Durall A, Zurakowski D, Wolfe J. Barriers to conducting advance care discussions for children with life‐threatening conditions. Pediatrics. 2012;129(4):e975‐e982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lotz JD, Jox RJ, Borasio GD, Fuhrer M. Pediatric advance care planning from the perspective of health care professionals: A qualitative interview study. Palliat Med. 2015;29(3):212‐222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hoffmann TC, Oxman AD, Ioannidis JPA, et al. Enhancing the usability of systematic reviews by improving the consideration and description of interventions. BMJ. 2017;357:j2998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Zadeh S, Pao M, Wiener L. Opening end‐of‐life discussions: how to introduce Voicing My CHOiCES™, an advance care planning guide for adolescents and young adults. Palliat Support Care. 2015;13(3):591‐599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lyon ME, Jacobs S, Briggs L, Cheng YI, Wang J. Family‐centered advance care planning for teens with cancer. JAMA Pediatr. 2013;167(5):460‐467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lyon ME, D’Angelo LJ, Dallas RH, et al. A randomized clinical trial of adolescents with HIV/AIDS: pediatric advance care planning. AIDS Care. 2017;29(10):1287‐1296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. CYPACP Collaboration N . Child and Young Person’s Advance Care Plan. 2017; http://cypacp.uk/document-downloads/. Accessed on 6 December 2019.

- 14. Craig P, Dieppe P, Macintyre S, Mitchie S, Nazareth I, Petticrew M. Developing and evaluating complex interventions: The new Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ. 2008;337(7676):979‐983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Fahner JC, Beunders AJM, Van Der HA, et al. Interventions Guiding Advance Care Planning Conversations : A Systematic Review. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2019;20:227e248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Fahner JC, Thölking TW, Rietjens JAC, van der Heide A, van Delden JJM, Kars MC. Towards advance care planning in pediatrics: a qualitative study on envisioning the future as parents of a seriously ill child. Eur J Pediatr. 2020. 10.1007/s00431-020-03627-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lin CP, Evans CJ, Koffman J, Armes J, Murtagh FEM, Harding R. The conceptual models and mechanisms of action that underpin advance care planning for cancer patients: A systematic review of randomised controlled trials. Palliat Med. 2019;33(1):5‐23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Popay J, Roberts H, Sowden A, et al. Guidance on the Conduct of Narrative Synthesis in Systematic Reviews A Product from the ESRC Methods Programme. London, United Kingdom: Institute for Health Research; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Waldman E, Wolfe J. Palliative care for children with cancer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2013;10(2):86‐93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Verberne LM, Kars MC, Meeteren AYNS, et al. Aims and tasks in parental caregiving for children receiving palliative care at home : a qualitative study. Eur J Pediatr. 2017;176(3):343‐354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Verberne LM, Kars MC, Meeteren AYNS, et al. Parental experiences and coping strategies when caring for a child receiving paediatric palliative care : a qualitative study. Eur J Pediatr. 2019;178:1075‐1085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kars MC, Duijnstee MS, Pool A, Van Delden JJ, Grypdonck MH. Being there: Parenting the child with acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. J Clin Nurs. 2008;17(12):1553‐1562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kars M, Grypdocnk M, Van Delden J. Being a parent of a child with cancer throughout the end‐of‐life course. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2011;38(4):2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Donovan HS, Ward S. A representational approach to patient education. J Nursing Scholarship. 2001;33(3):211‐216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Fried TR, Bullock K, Iannone L, O’Leary JR. Understanding advance care planning as a process of health behavior change. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57(9):1547‐1555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Stroebe M, Schut H. The dual process model of coping with bereavement: Rationale and description. Death Stud. 1999;23(3):197‐224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kars M, Grypdocnk M, De Korte‐Verhoef M, et al. Parental experience at the end‐of‐life in children with cancer : ‘ preservation ’ and ‘ letting go ’ in relation to loss. Support Care Cancer. 2011;19:27‐35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Mack JW, Wolfe J, Cook EF, Grier HE, Cleary PD, Weeks JC. Hope and prognostic disclosure. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(35):5636‐5642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Håkansson Eklund J, Holmström IK, Kumlin T, et al. “Same same or different?” A review of reviews of person‐centered and patient‐centered care. Patient Educ Couns. 2019;102(1):3‐11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Schulz R, Czaja SJ, McKay JR, Ory MGBS. Intervention Taxonomy (ITAX): Describing Essential Features of Interventions. Am J Heal Behav. 2010;34(6):811‐821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Back AL, Fromme EK, Meier DE. Training clinicians with communication skills needed to match medical treatments to patient values. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;67(S2):S435‐S441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Material