Abstract

PURPOSE:

To evaluate the relationships between aging-related domains captured by geriatric assessment (GA) for older patients with advanced cancer and caregivers’ emotional health and quality of life (QoL).

METHODS:

In this analysis of baseline data from a nationwide investigation of older patients and their caregivers, patients completed a GA that included validated tests to evaluate eight domains of health (e.g., function, cognition). Enrolled patients were aged 70+, had ≥1 GA domain impaired, and had an incurable solid tumor malignancy or lymphoma; each could choose one caregiver to enroll. Caregivers completed the Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7, Distress Thermometer, Patient Health Questionnaire-2 (depression), and Short Form Health Survey-12 (SF-12 for QoL). Separate multivariate linear or logistic regression models were used to examine the association of the number and type of patient GA impairments with caregiver outcomes, controlling for patient and caregiver covariates.

RESULTS:

In total, 541 patients were enrolled, 414 with a caregiver. Almost half (43.5%) of caregivers screened positive for distress, 24.4% for anxiety, and 18.9% for depression. Higher numbers of patient GA domain impairments were associated with caregiver depression [Adjusted Odds Ratio (AOR)=1.29, p<0.001], caregiver physical health on SF-12 (regression coefficient (β)=−1.24, p<0.001), and overall caregiver QoL (β=−1.14, p<0.01). Impaired patient function was associated with lower caregiver QoL (β=−4.11, p<0.001). Impaired patient nutrition was associated with caregiver depression (AOR=2.08, p<0.01). Lower caregiver age, caregiver comorbidity, and patient distress were also associated with worse caregiver outcomes.

CONCLUSION:

Patient GA impairments were associated with poorer emotional health and lower QoL of caregivers.

Keywords: caregivers, geriatric assessment, emotional health, quality of life

INTRODUCTION

The number of caregivers of older adults with cancer is on the rise.1 An informal caregiver has been defined as a relative, partner, or friend who provides assistance across multiple areas of functioning and living.2,3 Most older patients with cancer live at home and are dependent on informal caregivers for support with cancer treatment, symptom management, and activities of daily living.4,5 Clinicians often focus on the health of the patients, while informal caregivers are subjected to a significant amount of stress that can adversely affect their own physical and emotional health.6–8

As the cancer progresses, the level of care burden increases for the caregiver and can profoundly worsen caregivers’ quality of life (QoL).9,10 The role of caregiving itself impacts the emotional health of the caregivers; many studies demonstrate that caregivers experience even more emotional health challenges (e.g., anxiety, depression, distress) than the patients they are caring for.11–14 Furthermore, caregiver distress increases as the patient with cancer declines functionally.15

The geriatric assessment (GA) provides a framework that can be incorporated into clinical care to improve decision-making and guide interventions for vulnerable older adults with cancer.16 The GA assesses, with patient-reported and objective validated measures, aging-related domains known to influence morbidity and mortality in older patients with cancer—function, physical performance, comorbidities, polypharmacy, cognition, nutrition, psychological health, and social support.17 A 2015 Delphi consensus statement from geriatric oncology experts18 concluded that all of these GA domains are useful for guiding non-oncologic interventions and cancer treatment decisions. Eliciting support from caregivers is often a GA-guided recommendation for older patients with cancer.18

While previous studies have demonstrated that caregiving for patients with cancer is burdensome,3,7,19–21 no large study has evaluated if impaired GA domains in older patients with advanced cancer are associated with caregivers’ emotional health and QoL in a national cohort. In this analysis of baseline data from a large multicenter study that enrolled patients aged 70+ with advanced cancer who had at least one impaired GA domain, we describe the characteristics of study patients with a caregiver, and evaluate the relationships between impaired GA domains of the patients with the emotional health and QoL of their caregivers. Our primary hypothesis was that a higher number of impaired GA domains would be associated with poorer caregiver emotional health and QoL. These results will inform clinical practice and the development of interventions designed to improve the QoL of both frail older patients with advanced cancer and their caregivers.

METHODS

Study Design

This cross-sectional study used baseline data from older patients with advanced cancer and their caregivers from 31 community oncology practice clusters enrolled onto the Improving Communication in Older Cancer Patients and Their Caregivers (COACH) study (clinicaltrials.gov #NCT02107443; URCC13070) conducted through the University of Rochester (UR) National Cancer Institute (NCI) Community Oncology Research Program (NCORP) Research Base between October 2014 and April 2017. COACH is a cluster randomized trial to evaluate if a GA summary plus GA-guided recommendations improve communication between older patients with cancer, their oncologists, and their caregivers about age-related concerns.22

Study Participants

Patients were eligible if they were diagnosed with an advanced solid tumor or lymphoma, were considering or currently receiving any type of cancer treatment, and had an adequate understanding of the English language. Patients had at least one GA domain impairment excluding polypharmacy (due to the known high prevalence of polypharmacy in functionally fit patients); this eligibility criterion was designed to capture patients who are more frail than the fit older patients traditionally enrolled onto clinical trials.23 If patients did not have decision-making capacity, a healthcare proxy was required to sign the consent. One caregiver was chosen by the patient to enroll using the question: “Is there a family member, partner, friend, or caregiver (age 21 or older) with whom you discuss or who can be helpful in health-related matters?” It was not required for a patient to have a caregiver to participate. Caregivers had to be 21 years of age or older, have an adequate understanding of English, and be able to provide informed consent. This study was approved by the University of Rochester Research Subjects Review Board and Review Boards of each NCORP affiliate.

Study Procedures and Measures

Surveys were employed to obtain socio-demographic characteristics of each participant and caregiver and to assess their health. Clinical information was collected by research staff. At baseline, patients completed a GA consisting of validated measures to evaluate the health of older adults in eight domains: physical performance, functional status, comorbidity, cognition, nutrition, social support, polypharmacy, and psychological status.18 If a patient met a cut-off score for a measure, they were considered impaired in that domain (Supplemental Table 1, Table 1). At baseline, caregivers completed multiple validated measures of emotional health and QoL, including the 2-Item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-2), Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-Item Scale (GAD-7), Distress Thermometer, and Short Form Health Survey-12 (SF-12). A score of 2 on the PHQ-2 suggested depression and a score of ≥ 5 on the GAD-7 suggested anxiety.24–27 Distress was measured for both patients and caregivers using a distress thermometer with a score of ≥4 (0–10) suggesting at least moderate distress.28 QoL was captured with total SF-12 score and SF-12 subscales which capture mental and physical health; SF-12 scores and subscales range from 0–100, with higher scores indicating better QoL, mental health, and physical health.29

Table 1.

Demographics, clinical characteristics, and Geriatric Assessment impairments of patients with caregivers

| Patients with caregivers (n=414) |

|

|---|---|

| Variables | N (%) |

| Age (Mean(SD)) | 76.8 (5.4) |

| 70–79 | 299 (72.4%) |

| 80–89 | 103 (24.9%) |

| ≥90 | 11 (2.7%) |

| Gender | |

| Female | 176 (42.6%) |

| Male | 237 (57.4%) |

| Race/Ethnicity | |

| Non-Hispanic white | 371 (89.8%) |

| African American | 30 (7.3%) |

| Others | 12 (2.9%) |

| Education | |

| <High school | 57 (13.8%) |

| High school graduate | 142 (34.4%) |

| Some college or above | 214 (51.8%) |

| Income | |

| ≤$50,000 | 193 (46.8%) |

| >$50,000 | 219 (53.2%) |

| Living arrangements | |

| Independent living (more than 1 story) | 172 (41.7%) |

| Independent living (1 story) | 223 (54.1%) |

| Others | 17 (4.1%) |

| Cancer type | |

| Gastrointestinal | 103 (24.9%) |

| Lung | 109 (26.4%) |

| Other | 201 (48.7%) |

| Cancer stage | |

| Stage III | 35 (8.5%) |

| Stage IV | 365 (88.4%) |

| Others | 13 (3.1%) |

| Cancer treatment | |

| Any treatment (≥1) | 404 (97.8%) |

| Multiple treatments (≥2) | 136 (32.9%) |

| Chemotherapy | 282 (68.3%) |

| Monoclonal antibodies | 102 (24.7%) |

| Hormonal treatment | 66 (16.0%) |

| Orally administered cancer treatment | 73 (17.7%) |

| Radiation therapy | 40 (9.8%) |

| Geriatric Assessment impairments | |

| Physical Performance | 389 (94.0%) |

| TUG >13.5 seconds or | 161 (39.0%) |

| SPPB ≤9 points or | 325 (78.5%) |

| Falls History ≥1 in previous 6 months | 107 (25.8%) |

| OARS Physical Health ≥ 1 “a lot” of difficulty | 316 (76.3%) |

| Functional Status | 254 (61.4%) |

| ADL ≥1 for “yes” responses (for deficit) | 115 (27.8%) |

| IADLs ≥1 for “able to do with some help” or “completely unable to do” responses | 243 (58.7%) |

| Comorbidity | |

| OARS Comorbidity ≥3 or ≥1 that interfered with quality of life “a great deal” responses (included eyesight and hearing) | 263 (63.5%) |

| Cognition | 144 (34.8%) |

| BOMC ≥11 or | 12 (2.9%) |

| Mini-Cog 0 words recalled or 1–2 words recalled and abnormal clock | 144 (34.8%) |

| Nutrition | 259 (62.6%) |

| BMI <21.0 kg/m2 or | 45 (10.9%) |

| Weight loss >10% in the past 6 months or | 62 (15.0%) |

| MNA ≤11 points | 248 (59.9%) |

| Social Support | |

| OARS Medical Social Support ≥1 for “none,” “a little,” or “some of the time” support with tangible needs (e.g., someone to help go to doctor) | 91 (22.0%) |

| Polypharmacy | 350 (84.5%) |

| Polypharmacy Log ≥5 regularly scheduled prescription or medications or | |

| Polypharmacy High Risk Drug Review ≥1 high risk medication or | |

| Labs Creatinine Clearance or GFR <60 mL/min | |

| Psychological Status | 112 (27.1%) |

| GAD-7 ≥10 points | 39 (9.4%) |

| GDS ≥5 points | 100 (24.2%) |

Abbreviations: GFR, glomerular filtration rate; BOMC, Blessed Orientation Memory Concentration Test; BMI, body mass index; MNA, Mini Nutritional Assessment; TUG: Timed Up-and-Go; SPPB, Short Physical Performance Battery; OARS, Older Americans Resources and Services; ADL, activities of daily living; IADL: instrumental activities of daily living; GAD-7, General Anxiety Disorder 7-item scale; GDS, Geriatric Depression Scale;

count of domains impaired;

There were some missing data (no more than six missing data points for any question); percentages and statistics are calculated from available data.

Our primary independent variables were number of impaired patient GA domains and specific GA domain impairments. The number of GA domain impairments was the sum of all GA domains that were impaired (range 1–8).23

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to examined demographics, GA impairments, and clinical information. Bivariate analyses compared characteristics of patients enrolled with a caregiver to those without one. Bivariate analyses were also used to select significant caregiver and patient covariates, based on p<0.1, to enter a stepwise regression model. The final multivariate models included information from patient and caregiver dyads. These models included covariates with p<0.1 from stepwise procedures in addition to caregiver age, gender, race, and patient cancer type. Multivariate logistic regressions and linear regressions were performed for binary outcomes (depression, anxiety, and distress) and continuous outcomes (physical health, mental health, and total score on SF-12), respectively. In the models evaluating the number of patient GA domain impairments as primary variable of interest, the number was included as a continuous variable. For the models evaluating specific GA domains, each domain was included if associated with the outcome at p<0.1. Likelihood Ratio tests from linear or generalized mixed models with practice oncology site as random effects were not statistically significant (all p>0.1), suggesting a weak clustering effect of practice site; therefore the results from the original multivariate models were presented. Two-sided p-values of <0.05 were considered statistically significant. All analyses were conducted with SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC) and Stata 13.0 (StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX).

RESULTS

Patient demographics

In total, 414 eligible older patients with advanced cancer who were enrolled with a caregiver were included in this analysis . On average, the patients were 76.8 years old (standard deviation [SD]=5.4; range 70–96). The majority of the cohort was non-Hispanic white (89.8%) and had stage IV cancer (88.4%). The mean number of GA domain impairments for the sample was 4.48 (SD 1.53); 89.6% had 3 or more domains impaired (Supplementary Figure 1). More than 80% of the patients had polypharmacy, and nearly all the patients had physical performance problems (94.0%) (Table 1). Just over one-third (34.8%) of patients had an abnormal screen for cognitive impairment, 63.5% had significant comorbidities, and 27.1% had a positive screen for depression or anxiety.

Caregiver demographics

The average caregiver age was 66 years (range 26–92 years); 48.9% of caregivers were aged 70 and over (Table 2). The majority of caregivers were female (75.4%), non-Hispanic white (89.8%), and the patient’s spouse or cohabiting partner (67.2%). Close to 40% of caregivers had significant comorbidities of their own, 43.5% reported moderate to high distress, 18.9% reported depressive symptoms, and 24.4% were anxious. Mean SF-12 scores were 98.0 (SD 14.2); 46.9 (SD 10.5) for the physical health subscale and 51.1 (SD 9.8) for the mental health subscale.

Table 2.

Caregiver demographics and clinical characteristics†

| N=414 | |

|---|---|

| Variables | N (%) |

| Age (Mean(SD)) | 66.5 (12.5) |

| <70 | 210 (51.1%) |

| 70–79 | 151 (36.7%) |

| ≥80 | 50 (12.2%) |

| Gender | |

| Female | 310 (75.4%) |

| Male | 101 (24.6%) |

| Education | |

| <High school | 30 (7.3%) |

| High school graduate | 118 (28.7%) |

| Some college or above | 263 (64.0%) |

| Race | |

| Non-Hispanic white | 369 (89.8%) |

| African American | 27 (6.6%) |

| Other | 15 (3.6%) |

| Relationship | |

| Spouse/cohabiting partner | 276 (67.2%) |

| Son/daughter | 94 (22.9%) |

| Other | 41 (10.0%) |

| Income, annual | |

| <$50,000 | 151 (36.8%) |

| >$50,000 | 259 (63.2%) |

| Living arrangements | |

| Independent living (more than 1 story) | 188 (45.9%) |

| Independent living (1 story) | 215 (52.4%) |

| Other | 7 (1.7%) |

| Comorbidity* | |

| Yes | 162 (39.4%) |

| No | 249 (60.6%) |

| Anxiety (GAD-7) (≥5) | |

| Yes | 97 (24.4%) |

| No | 300 (75.6%) |

| Distress (≥4) | |

| Yes | 177 (43.5%) |

| No | 230 (56.5%) |

| Depression (PHQ-2) (≥2) | |

| Yes | 75 (18.9%) |

| No | 322 (81.1%) |

Abbreviations: GAD-7, generalized anxiety disorder 7-item scale; PHQ, patient health questionnaire

Missing data ≤3% for any variable; percentages are calculated from available data.

Defined using the Older American Resources and Services Comorbidity Form which assesses the presence of 13 illnesses, and how much each problem interferes with his/her function; caregiver was noted to have the domain impaired if s/he answered “yes” to 3 illnesses or answered that 1 illness interferes “a great deal”

Multivariable Analyses

Several caregiver characteristics were associated with caregiver outcomes (Table 3, Table 4). Increasing caregiver age was associated with less anxiety and depression, as well as better SF-12 mental health, but poorer SF-12 physical health. Being female was associated with less distress [AOR (95% CI)=0.43 (0.25–0.74), p<0.01]. An income >$50,000/year was associated with higher SF-12 physical subscale and total scores. In the models evaluating the number of GA domains, caregiver comorbidities were associated with caregiver anxiety [AOR (95% CI)=2.94 (1.70–5.09), p<0.001], depression [AOR (95% CI)=3.13 (1.74–5.60), p<0.001], poorer SF-12 physical health [β (95% CI)=−8.11 (−10.09–−6.13), p<0.001), poorer SF-12 mental health [β (95% CI)=−3.99 (−6.00–−1.97), p<0.001), and poor overall QoL [β (95% CI)=−11.86 (−14.57–−9.16), p<0.001).

Table 3.

The association of caregiver/patient predictors with caregiver emotional health and quality of life outcomes in models with number of GA domains impaired

| Independent variables | Anxiety (GAD-7) |

Distress | Depression (PHQ-2) |

SF-12 Physical Health |

SF-12 Mental Health |

SF-12 Total Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | Coef. (95% CI) | Coef. (95% CI) | Coef. (95% CI) | |

| Caregiver Predictors | ||||||

| Age | 0.96 (0.94–0.99)* | 0.98 (0.96–1.00)^ | 0.97 (0.94–0.99)* | −0.13 (−0.21– −0.05)* | 0.23 (0.14–0.31)** | 0.08 (−0.04–0.19) |

| Female (vs male) | 0.93 (0.50–1.73) | 0.43 (0.25–0.74)* | 0.72 (0.37–1.42) | 2.14 (0.06–4.34) | 0.30 (−1.95–2.54) | 2.15 (−0.84–5.14) |

| Non-Hispanic white (vs other) | 1.17 (0.51–2.67) | 0.90 (0.45–1.84) | 0.80 (0.36–1.79) | 0.12 (−2.93–3.16) | −1.78 (−4.90–1.34) | −1.59 (−5.74–2.56) |

| Income > $50,000 + ‘Decline to answer’ (vs < $50,000) | 0.62 (0.37–1.03) | - | - | 2.40 (0.48–4.32)^ | - | 4.03 (1.39–6.66)* |

| Comorbidity | 2.94 (1.69–5.09)** | - | 3.13 (1.74–5.60)** | −8.11 (−10.09– −6.13)** | −3.99 (−6.00– −1.97)** | −11.86 (−14.57– −9.16)** |

| Patient Predictors | ||||||

| Cancer type (vs GI) | ||||||

| Lung | 1.22 (0.62–2.39) | 1.04 (0.58–1.88) | 0.84 (0.41–1.71) | −1.16 (−3.72–1.41) | 0.13 (−2.51–2.77) | −1.03 (−4.54–2.47) |

| Others | 0.84 (0.45–1.56) | 0.57 (0.34–0.97)^ | 0.68 (0.36–1.27) | −2.48 (−4.73– −0.24)^ | 0.64 (−1.66–2.94) | −1.85 (−4.91–1.21) |

| Distress (≥4) | 2.07 (1.22–3.52)* | 2.79 (1.76–4.44)** | - | - | −2.62 (−4.70 – −0.54)^ | −3.51 (−6.28 – −0.74)^ |

| Number of GA domains impaired | 0.98 (0.82–1.16) | 1.11 (0.96–1.29) | 1.29 (1.07–1.55)** | −1.24 (−1.85– −0.63)** | 0.00 (−0.66–0.65) | −1.14 (−2.01– −0.27)* |

Note: Lower scores for the GAD-7, distress thermometer, and PHQ-2 indicate lower anxiety, distress, and depression, respectively; while higher scores on the SF-12 indicate greater quality of life.

p-value<0.05,

p-value<0.01;

p-value<0.001

Predictors with empty cells were excluded in the stepwise procedure.

Abbreviations: GAD-7, generalized anxiety disorder 7-item scale; PHQ, patient health questionnaire; SF-12, 12-item short form health survey; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; Coef, coefficient; GI, gastrointestinal; GA, geriatric assessment

Table 4:

The association of caregiver/patient predictors with caregiver emotional health and quality of life outcomes in models with individual GA domains

| Independent variables | Anxiety (GAD-7) |

Distress | Depression (PHQ-2) |

SF-12 Physical Health |

SF-12 Mental Health |

SF-12 Total Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | Coef. (95% CI) | Coef. (95% CI) | Coef. (95% CI) | |

| Caregiver Predictors | ||||||

| Age | 0.96 (0.94 – 0.99)* | 0.98 (0.96–1.00)* | 0.96 (0.94–0.98)** | −0.13(−0.21– −0.05)* | 0.23 (0.14 – 0.31)** | 0.07 (−0.04–0.18) |

| Female (vs male) | 0.92 (0.50 – 1.71) | 0.44 (0.26–0.75)* | 0.74 (0.38–1.46) | 2.43 (0.23–4.64)^ | 0.30 (−1.93 – 2.52) | 2.35 (−0.64–5.34) |

| Non-Hispanic white (vs other) | 1.17 (0.51 – 2.67) | 0.86 (0.42–1.75) | 0.72 (0.32–1.60) | 0.15 (−2.88–3.19) | −1.78 (−4.89 – 1.33) | −1.50 (−5.62–2.63) |

| Income > $50,000 + ‘Decline to answer’ (vs < $50,000) | 0.61 (0.37 – 1.03) | - | - | 2.41 (0.50–4.33)^ | - | 4.27 (1.65–6.89)* |

| Comorbidity | 2.91 (1.69 – 5.04)** | - | 3.46 (1.94–6.18)** | −7.86 (−9.85– −5.87)** | −3.99 (−5.99– −1.98)** | −11.56 (−14.28– −8.85)** |

| Patient Predictors | ||||||

| Cancer type (vs GI) | ||||||

| Lung | 1.22 (0.62 – 2.39) | 1.06 (0.59–1.92) | 0.86 (0.42–1.74) | −1.30 (−3.85–1.26)* | 0.13 (−2.50 – 2.76) | −1.02 (−4.51–2.47) |

| Others | 0.84 (0.45 – 1.56) | 0.60 (0.35–1.01)^ | 0.71 (0.38–1.35) | −2.47 (−4.71– −0.24)^ | 0.64 (−1.66 – 2.94) | −1.85 (−4.90–1.19) |

| Distress (≥4) | 2.03 (1.22 – 3.38)* | 2.95 (1.89–4.61)** | - | - | −2.62 (−4.61 – −0.64)* | −3.97 (−6.64– −1.31)* |

| Impaired function | - | - | - | −2.50 (−4.45– −0.56)^ | - | −4.11 (−6.73– −1.48)** |

| Impaired nutrition | - | 1.45 (0.92–2.26) | 2.08 (1.15–3.77)* | - | - | - |

Note: Lower scores for the distress thermometer and PHQ-2 indicate distress and depression, respectively; while higher scores on the SF-12 indicate greater quality of life.

p-value<0.05,

p-value<0.01;

p-value<0.001

Predictors with empty cells were excluded in the stepwise procedure.

Abbreviations: GAD-7, generalized anxiety disorder 7-item scale; PHQ, patient health questionnaire; SF-12, 12-item short form health survey; OR, odds ratio; Coef, coefficient; GI, gastrointestinal; GA, geriatric assessment

In the models evaluating the number of GA domains, patient distress was associated with caregiver anxiety [AOR (95% CI)=2.07 (1.22–3.52), p<0.01], caregiver distress [AOR (95% CI)=2.79 (1.76–4.44), p<0.01], caregiver mental health on SF-12 [AOR (95% CI)=−2.62 (−4.70–−0.54), p<0.05], and overall QoL on SF-12 [β (95% CI)=−3.51(−6.28–−0.74), p<0.05].

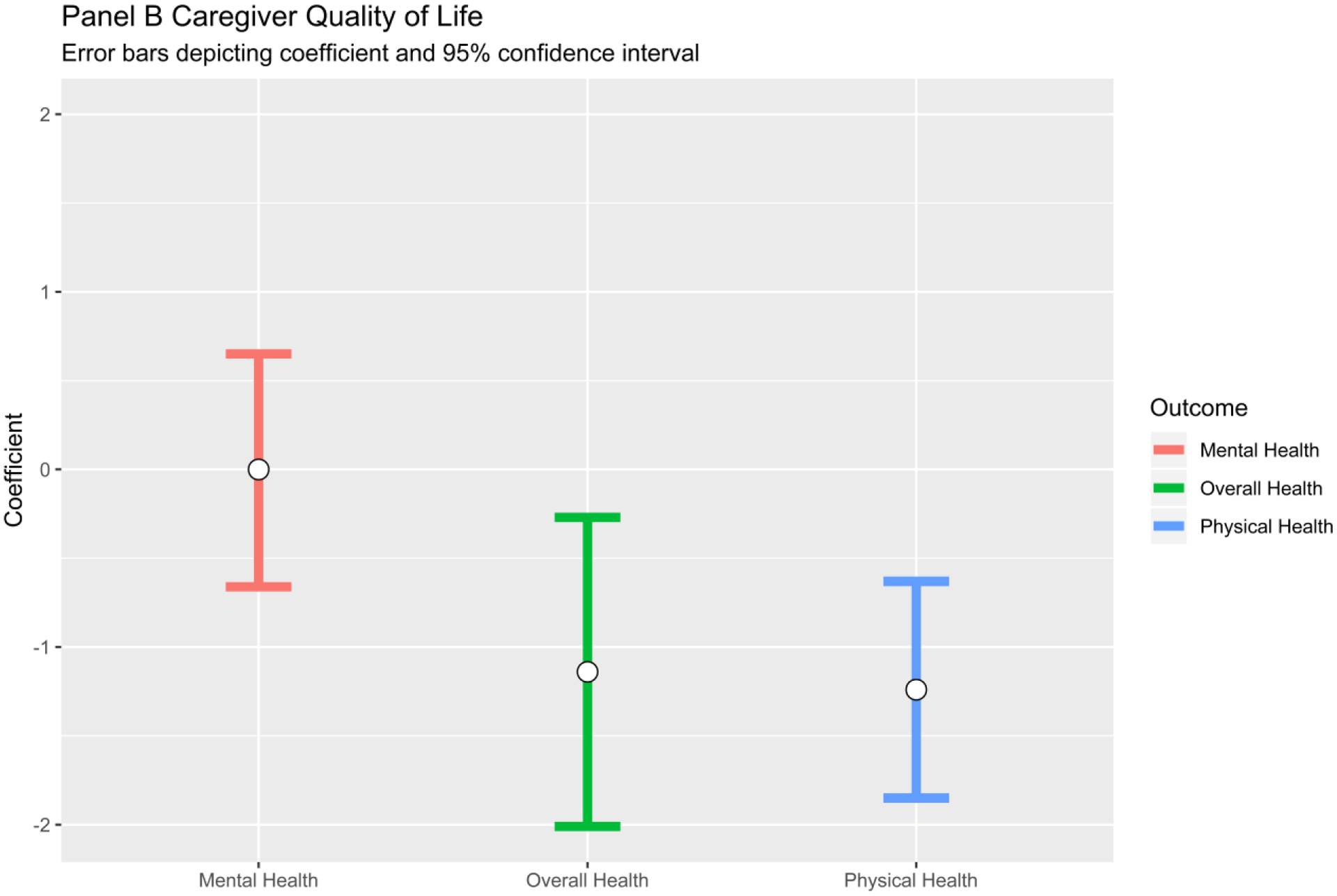

Our primary independent variables of interest were the number of GA domain impairments for the patient and individual domain impairments (Table 3, Table 4, and Figure 1. ). In the multivariate analysis, the number of patient GA domain impairments was associated with caregiver depression [AOR (95% CI)=1.29 (1.07–1.55), p<0.001], lower caregiver physical health [β (95% CI)=−1.24 (−1.85– −0.63), p<0.001], and lower caregiver QoL [β (95% CI)=−1.14 (−2.01– −0.27), p<0.01]. In separate models for individual GA domains, impaired patient functional status was associated with significantly worse caregiver physical health [β (95% CI)=−2.55 (−4.45– −0.56), p<0.05] and overall QoL [β (95% CI)=−4.11 (−6.73– −1.48), p<0.001]. Impaired patient nutrition was significantly associated with caregiver depression [AOR (95% CI)=2.08 (1.15–3.77), p<0.01].

Figure 1.

Association between Number of Impaired Patient Geriatric Assessment Domains and Caregiver Outcomes. Note: Besides caregiver age, sex, race, and patient cancer type, the following covariates were also included in the multivariate models if they had a P value <.1 in the stepwise models: caregiver education, family income, living arrangement, comorbidity, distress; patient cancer treatments.

DISCUSSION

In this large cohort of older patients with advanced cancer and their caregivers, patient GA measures were associated with emotional health and QoL of informal caregivers. Specifically, a higher number of patient GA impairments was associated with caregiver depression and lower caregiver QoL.

Informal caregivers provide essential support for older patients with advanced cancer receiving treatment, including assisting with activities of daily living, performing medical and nursing related tasks, and providing direct physical and emotional assistance.30 Our descriptive results are similar to previous studies.7,31,32 Hsu et al.33 found that in 100 patients aged 65+ (70% with advanced cancer) and their caregivers, caregivers were mostly female (73%) and spouses (68%); 79% lived with the patient. Jones et al32 found that in 76 caregivers of older patients with cancer, 19.1% and 23.6% reported moderate or greater anxiety and depression, respectively. In this study, lower caregiver age was associated with higher prevalence of emotional health issues (i.e., anxiety, depression), and caregiver comorbidities were adversely associated with all caregiver outcomes except for distress. Clinicians should consider caregiver comorbid conditions when evaluating the caregiver’s emotional health and QoL.

Our study adds to evidence supporting an interdependent relationship between patient and caregiver health. Patient distress is associated with caregiver distress.34 In a study of 43 caregiver/patient dyads, caregivers of patients with depression experienced greater emotional distress.35 In this study, we also showed that patient function is associated with caregiver outcomes. In the study by Hsu et al.,32 caregivers reported that patients had poorer physical function and mental health than the patients reported for themselves. In multivariate analysis, those caring for patients who required more help with instrumental activities of daily living were more likely to experience high caregiver burden. Germain et al.7 showed that in close to 100 older patients with cancer and their caregivers, older patient age, perceived burden by caregiver, and patient functional status were associated with lower caregiver QoL. On the other hand, Rajasekaran et al.36 did not find an association between patient GA measures and caregiver burden using the Zarit Burden Interview, a measure that captures physical and mental health constructs in the context of caregiving. SF-12, used in this study, captures physical and mental health more globally and does not ask about these constructs in the context of caregiving. Caregivers may self-report global QoL deficits, without communicating caregiver burden. Other potential reasons for differences in outcomes between studies could be related to patient sample; our sample included only patients with advanced cancer who had at least one GA domain impairment, which is more frail than studies that also included patients undergoing curative intent therapy.

This study is the first to show the association between the number of GA impairments and caregiver health (specifically caregiver depression, poorer physical health, and poorer QoL) in older patients with advanced cancer. In this nationwide study, 89.6% had three or more GA domains impaired. This number is likely high due to our eligibility criteria, although comparable to some studies enrolling “real-world” patients.17 The number of GA domain impairments was independently associated with caregiver outcomes beyond other patient and caregiver clinical and demographic factors. In addition to the number of GA domains, two specific GA domains had strong independent associations: nutrition with caregiver depression, and impaired functional status with poorer caregiver physical health and QoL. Previous studies have shown that patient function is associated with caregiver burden and QoL, and that caregivers have expressed that nutritional concerns (e.g., anorexia, cachexia) can affect their emotional health.13,37–39,54 These findings suggest that the clinical team should address caregiver needs especially when the patient’s GA shows a high number of domain impairments and/or when patients have significant nutritional, functional, or mental health concerns. Audio-recordings of clinical encounters between older patients, caregivers, and oncologists have shown that while caregivers are unlikely to bring up their own emotional and physical health needs, they do provide clues when they bring up patients’ age-related concerns such as medication, functional, and nutritional issues that increase their own distress.40,41 These conversations are opportunities for oncology teams to offer support for caregivers.

A symposium of experts convened by the National Cancer Institute and National Institute of Nursing Research in 2016 highlighted the need for developing and testing interventions for caregivers.1 Other research reports have discussed the need to develop interventions to improve psychosocial care for older patients and their caregivers.42,43 In one large study, lack of formal training in medical/nursing skills was associated with greater levels of caregiver burden.30 Skills training is a potential area for interventions, but research on how best to provide training for caregivers (i.e., the content, mode of delivery, and timing) is needed.30 In another study, unhealthy behaviors (i.e., low physical activity, binge drinking) were associated with worse emotion-focused coping of caregivers; interventions that provide support for promoting healthier behaviors for caregivers may improve their emotional health.44 Early and integrated palliative care and psychosocial interventions for both patients and caregivers have been shown to improve outcomes, although more work on dissemination and implementation is needed.45

While the American Society of Clinical Oncology17 and other guidelines46,47 have recommended GA for older patients with cancer receiving chemotherapy, there is limited data on how GA can help guide interventions to improve QoL and emotional health in caregivers of older adults with cancer. Given the aging of both patients with cancers and their caregivers, a GA-guided dyadic approach to interventions should be studied.48 Engaging both older patients and their caregivers in the research process from design to dissemination of interventions may improve the successful implementation and integration of interventions for vulnerable caregivers at high risk for poor emotional health and QoL. In a series of focus groups with older adults and caregivers, Puts et al45,46 found that the stakeholders were motivated to work with a research team, but that there are logistical considerations (such as accessibility of technology and transportation) that need to be addressed to support engagement. Trevino held a one-day conference with older patient and caregiver stakeholders and found that tailoring interventions for older adults and modifying institutional-level factors to allow for ease of implementation was important to them.43

Strengths of this study include its large sample size of older frail patients with advanced cancer and their caregivers. Limitations of this study involve the use of a cross-sectional design, which prevents determination of causation. Furthermore, cross-sectional designs present limitations by using only one time point to assess outcomes. Patients and caregivers were enrolled on a clinical trial from community oncology clinics, which may not be as representative as a population-based sample. There is also a potential sample bias, as all participants were required to have a GA impairment, which could lend to more frail older adults being included in the analysis. Additionally, to minimize the burden of this study on participants, only broad screening tools, as opposed to more refined diagnostic tools, were used to assess caregiver burden, anxiety, depression, and QoL, which may lead to some error in the measurement of these constructs. While the relationships between patient GA factors and caregiver outcomes are reasonably strong, we did not adjust for multiple comparisons;51 the study’s results should be considered hypothesis generating and require validation in other cohorts.

In conclusion, this study indicates that caregivers for older patients with advanced cancer are a vulnerable group. Caregivers are often older themselves, and their own comorbidities are associated with poor emotional health and QoL. Future studies should explore GA-guided interventions that include not only the older patient with cancer but also their caregivers, as a dyadic or triadic (with the oncologist)52 approach to interventions. Given that poor caregiver emotional and self-rated health is associated with patient perceived quality of care, interventions may not only improve clinical outcomes, but also patient and caregiver satisfaction with care delivery.53

Supplementary Material

IMPACT STATEMENT.

This novel study reports on the relationships between patient and caregiver health in a national sample of older patients with advanced cancer and their caregivers. The results show that a higher number of impairments detected on the patient’s geriatric assessment (GA) is associated with poorer caregiver emotional health and quality of life. This information lends supports to using GA as a means for improving caregiver health through clinical care and dyadic interventions.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank the patients and caregivers who participated in the study as well as the research staff in the University of Rochester NCI Community Oncology Research Base network. In addition, we want to acknowledge the patient and caregiver stakeholders in SCOREboard. This work would not have been possible without them.

Funding: The work was funded through a Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) Program contract (4634), UG1 CA189961, R01 CA177592, and K24 AG056589. All statements in this report, including its findings and conclusions, are solely those of the authors, do not necessarily represent the official views of the funding agencies, and do not necessarily represent the views of the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI), its Board of Governors, or Methodology Committee.

Sponsor’s Role: The sponsor soley provided funding and has no other role in collecting data or its analysis and interpretation.

Footnotes

Previous Presentation: Presented as an oral presentation at the Society of International Geriatric Oncology in Warsaw, Poland in November, 2017

Conflicts of interest: Dr. Hurria received research funding from Celgene, Novartis, GSK, and is a consultant to Behringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals, Carevive, Sanofi, GTX, Pierian Biosciences, and MJH Healthcare Holdings, LLC. No other disclosures reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kent EE, Rowland JH, Northouse L, et al. Caring for caregivers and patients: Research and clinical priorities for informal cancer caregiving. Cancer. 2016;122(13):1987–1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roth DL, Fredman L, Haley WE. Informal caregiving and its impact on health: a reappraisal from population-based studies. Gerontologist. 2015;55(2):309–319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hsu T, Loscalzo M, Ramani R, et al. Factors associated with high burden in caregivers of older adults with cancer. Cancer. 2014;120(18):2927–2935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rha SY, Park Y, Song SK, Lee CE, Lee J. Caregiving burden and health-promoting behaviors among the family caregivers of cancer patients. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2015;19(2):174–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wadhwa D, Burman D, Swami N, Rodin G, Lo C, Zimmermann C. Quality of life and mental health in caregivers of outpatients with advanced cancer. Psychooncology. 2013;22(2):403–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grande G, Rowland C, van den Berg B, Hanratty B. Psychological morbidity and general health among family caregivers during end-of-life cancer care: A retrospective census survey. Palliat Med. 2018:269216318793286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Germain V, Dabakuyo-Yonli TS, Marilier S, et al. Management of elderly patients suffering from cancer: Assessment of perceived burden and of quality of life of primary caregivers. J Geriatr Oncol. 2017;8(3):220–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haley WE. Family caregivers of elderly patients with cancer: understanding and minimizing the burden of care. J Support Oncol. 2003;1(4 Suppl 2):25–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Given BA. Caregiver Burden In: Holland JC, Weisel TW, Nelson CJ, Roth AJ, Alici Y, eds. Geriatric Psycho-Oncology: A Quick Reference on the Psychological Dimensions of Cancer Symptom Management. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim MH, Dunkle RE, Lehning AJ, Shen H-W, Feld S, Perone AK. Caregiver stressors and depressive symptoms among older husbands and wives in the United States. Journal of Women and Aging. 2017;29(6):494–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Braun M, Mikulincer M, Rydall A, Walsh A, Rodin G. Hidden morbidity in cancer: spouse caregivers. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(30):4829–4834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Revenson TA, Griva K, Luszczynska A, et al. Caregiving Outcomes In: Caregiving in the Illness Context. London: Palgrave Pivot; 2016:15–24. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mellon S, Northouse LL, Weiss LK. A Population-Based Study of the Quality of Life of Cancer Survivors and Their Family Caregivers. Cancer Nursing. 2006;29(2):120–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Siefert ML, Williams A-L, Dowd MF, Chappel-Aiken L, McCorkle R. The Caregiving Experience in a Racially Diverse Sample of Cancer Family Caregivers. Cancer Nursing. 2008;31(5):399–407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Northouse L, Williams AL, Given B, McCorkle R. Psychosocial care for family caregivers of patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(11):1227–1234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Magnuson A, Allore H, Cohen HJ, et al. Geriatric assessment with management in cancer care: Current evidence and potential mechanisms for future research. Journal of geriatric oncology. 2016;7(4):242–248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mohile SG, Dale W, Somerfield MR, et al. Practical Assessment and Management of Vulnerabilities in Older Patients Receiving Chemotherapy: ASCO Guideline for Geriatric Oncology. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(22):2326–2347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mohile SG, Verlarde C, Hurria A, et al. Geriatric Assessment-Guided Care Processes for Older Adults: A Delphi Consensus of Geriatric Oncology Experts. Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network. 2015;13(9):1120–1130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Given BA, Given CW, Sherwood PR. Family and caregiver needs over the course of the cancer trajectory. J Support Oncol. 2012;10(2):57–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kurtz ME, Kurtz JC, Given CW, Given B. Relationship of caregiver reactions and depression to cancer patients’ symptoms, functional states and depression--a longitudinal view. Soc Sci Med. 1995;40(6):837–846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sherwood PR, Given CW, Given BA, von Eye A. Caregiver burden and depressive symptoms: analysis of common outcomes in caregivers of elderly patients. J Aging Health. 2005;17(2):125–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mohile SG, Epstein RM, Hurria A, et al. Improving communication with older patients with cancer using geriatric assessment (GA): A University of Rochester NCI Community Oncology Research Program (NCORP) cluster randomized controlled trial (CRCT). Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2018;36(18_suppl):LBA10003–LBA10003. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cohen HJ, Smith D, Sun CL, et al. Frailty as determined by a comprehensive geriatric assessment-derived deficit-accumulation index in older patients with cancer who receive chemotherapy. Cancer. 2016;122(24):3865–3872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jakobsson U Using the 12-item Short Form health survey (SF-12) to measure quality of life among older people. Aging Clinical and Experimental Research. 2007;19(6):457–464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW. The Patient Health Questionnaire-2: Validity of a Two-Item Depression Screener. Medical Care. 2003;41(11):1284–1292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JBW, Löwe B. A Brief Measure for Assessing Generalized Anxiety Disorder: The GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(10):1092–1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ransom S, Jacobsen PB, Booth-Jones M. Validation of the Distress Thermometer with bone marrow transplant patients. Psychooncology. 2006;15(7):604–612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Network NCC. NCCN Distress Thermometer and Problem List for Patients. In:2016.

- 29.Ware J Jr., Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care. 1996;34(3):220–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mollica MA, Litzelman K, Rowland JH, Kent EE. The role of medical/nursing skills training in caregiver confidence and burden: A CanCORS study. Cancer. 2017;123(22):4481–4487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jayani R, Hurria A. Caregivers of older adults with cancer. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2012;28(4):221–225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jones SB, Whitford HS, Bond MJ. Burden on informal caregivers of elderly cancer survivors: risk versus resilience. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2015;33(2):178–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hsu T, Loscalzo M, Ramani R, et al. Are Disagreements in Caregiver and Patient Assessment of Patient Health Associated with Increased Caregiver Burden in Caregivers of Older Adults with Cancer? The oncologist. 2017;22(11):1383–1391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hodges LJ, Humphris GM, Macfarlane G. A meta-analytic investigation of the relationship between the psychological distress of cancer patients and their carers. Soc Sci Med. 2005;60(1):1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tan JY, Molassiotis A, Lloyd-Williams M, Yorke J. Burden, emotional distress and quality of life among informal caregivers of lung cancer patients: An exploratory study. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2018;27(1). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rajasekaran T, Tan T, Ong WS, et al. Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment (CGA) based risk factors for increased caregiver burden among elderly Asian patients with cancer. Journal of geriatric oncology. 2016;7(3):211–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rhondali W, Chisholm GB, Daneshmand M, et al. Association between body image dissatisfaction and weight loss among patients with advanced cancer and their caregivers: a preliminary report. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2013;45(6):1039–1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Paek MS, Nightingale CL, Tooze JA, Milliron BJ, Weaver KE, Sterba KR. Contextual and stress process factors associated with head and neck cancer caregivers’ physical and psychological well-being. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2018;27(2):e12833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mislang AR, Di Donato S, Hubbard J, et al. Nutritional management of older adults with gastrointestinal cancers: An International Society of Geriatric Oncology (SIOG) review paper. J Geriatr Oncol. 2018;9(4):382–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lowenstein L, Mohile SG. Missed Opportunities to Discuss Patient and Caregiver Aging Concerns in Oncology Clinical Encounters. . 2015.

- 41.Ramsdale E, Lemelman T, Loh KP, et al. Geriatric assessment-driven polypharmacy discussions between oncologists, older patients, and their caregivers. Journal of geriatric oncology. 2018;9(5):534–539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Given B, Given CW. Cancer treatment in older adults: implications for psychosocial research. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57 Suppl 2:S283–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Trevino KM, Healy C, Martin P, et al. Improving implementation of psychological interventions to older adult patients with cancer: Convening older adults, caregivers, providers, researchers. J Geriatr Oncol. 2018;9(5):423–429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Litzelman K, Kent EE, Rowland JH. Interrelationships Between Health Behaviors and Coping Strategies Among Informal Caregivers of Cancer Survivors. Health Educ Behav. 2018;45(1):90–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hoerger M, Cullen BD. Early Integrated Palliative Care and Reduced Emotional Distress in Cancer Caregivers: Reaching the “Hidden Patients”. Oncologist. 2017;22(12):1419–1420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hurria A, Wildes T, Blair SL, et al. Senior adult oncology, version 2.2014: clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2014;12(1):82–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wildiers H, Heeren P, Puts M, et al. International Society of Geriatric Oncology consensus on geriatric assessment in older patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(24):2595–2603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mohile SG, Hurria A, Cohen HJ, et al. Improving the quality of survivorship for older adults with cancer. Cancer. 2016;122(16):2459–2568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Puts MTE, Sattar S, Fossat T, et al. The Senior Toronto Oncology Panel (STOP) Study: Research Participation for Older Adults With Cancer and Caregivers. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2017;15(10):1208–1215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Puts MTE, Sattar S, Ghodraty-Jabloo V, et al. Patient engagement in research with older adults with cancer. J Geriatr Oncol. 2017;8(6):391–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Feise RJ. Do multiple outcome measures require p-value adjustment? BMC Med Res Methodol. 2002;2:8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Laidsaar-Powell R, Butow P, Charles C, et al. The TRIO Framework: Conceptual insights into family caregiver involvement and influence throughout cancer treatment decision-making. Patient Educ Couns. 2017;100(11):2035–2046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Litzelman K, Kent EE, Mollica M, Rowland JH. How does caregiver well-being relate to perceived quality of care in patients with cancer? Exploring associations and pathways. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(29):3554–3561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Monin J, Doyle M, Levy B, Schulz R, Fried T, Kershaw T. Spousal associations between frailty and depressive symptoms: Longitudinal findings from the Cardiovascular Health Study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64(4):824–830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.