Abstract

While heterogeneous enzyme reactions play an essential role in both nature and green industries, computational predictions of their catalytic properties remain scarce. Recent experimental work demonstrated the applicability of the Sabatier principle for heterogeneous biocatalysis. This provides a simple relationship between binding strength and the catalytic rate and potentially opens a new way for inexpensive computational determination of kinetic parameters. However, broader implementation of this approach will require fast and reliable prediction of binding free energies of complex two-phase systems, and computational procedures for this are still elusive. Here, we propose a new framework for the assessment of the binding strengths of multidomain proteins, in general, and interfacial enzymes, in particular, based on an extended linear interaction energy (LIE) method. This two-domain LIE (2D-LIE) approach was successfully applied to predict binding and activation free energies of a diverse set of cellulases and resulted in robust models with high accuracy. Overall, our method provides a fast computational screening tool for cellulases that have not been experimentally characterized, and we posit that it may also be applicable to other heterogeneously acting biocatalysts.

1. Introduction

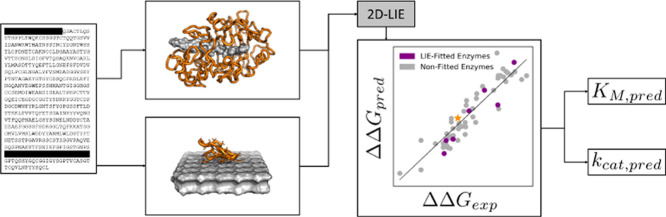

Most enzymatic reactions, both in vivo1 and in industrial applications,2 occur at an interface and hence represent heterogeneous (bio)catalysis. One important industrial example is so-called saccharification, where plant biomass is enzymatically deconstructed into small sugars for subsequent fermentation to biofuels and green alternatives to petrochemicals.3 Several other technical enzyme applications also entail modification of an insoluble substrate by soluble enzymes.2,4 Nevertheless, general kinetic descriptions of heterogeneous biocatalysis remain scarce and incomplete, and this restricts both mechanistic understanding and rational design of industrial enzymes.5 Recent work has suggested that the efficacy of heterogeneous enzymes may be rationalized along the lines of the Sabatier principle.6 This concept7 states that efficient catalysis occurs at an intermediate strength of substrate–catalyst interactions, and it is well established within (nonbiochemical) heterogeneous catalysis.8 In this field, it makes up a valuable framework for analysis of microkinetic models and it provides guidance for the computer-assisted design of inorganic catalysts.9 In the current work, we explore related applications for heterogeneous biocatalysts using cellulases as an example. Our starting point is the experimental observation10 of a linear free-energy relationship (LFER) between binding energy and the activation barrier for a wide range of cellulases (see Figure 1). This scaling has the important corollary that it links the two customary enzyme kinetic parameters KM (which is related to substrate binding strength,10,11 see eq 3) and kcat = Vmax/E0 (which is related to the activation energy of the rate-limiting step at a steady state). In practice, this means that if the linkage of KM and kcat can be specified from a workable number of experiments, one could obtain detailed insights into the function of uncharacterized enzymes if just one of the kinetic parameters can be determined in silico. Then, the other could subsequently be estimated from the LFER. The computed kinetic parameters will pertain specifically to the conditions (temperature, pH, type of substrate, etc.) of the empirical LFER. Nevertheless, the approach could open up for in silico comparative biochemistry and hence contribute to the elucidation of the sequence–function relationship for heterogeneous enzyme reactions. One application of such a tool would be to predict and rationalize catalytic properties of isoenzymes from different organisms. Another would be computer-aided enzyme design, which strives to find variants with desired properties for technical applications.

Figure 1.

Simplified energy diagram of the processive cycle of cellulases and the schematic representation of the LFER for different cellulases acting on the same substrate.12 Desorption has been found to be the rate-limiting step of the processive cycle.13−16 The experimental LFER provides a simple correlation between the strength of the enzyme–substrate interaction and the maximal turnover. This, in turn, opens for fast computational assessment of enzyme kinetics because the turnover can be predicted from the LFER if accurate estimates of binding strength can be determined in silico.

In silico determination of binding free energies is, in general, much easier than computational assessment of activation free energies as the former can be done within the framework of molecular dynamics (MD)/molecular mechanics (MM) and the latter needs, at least partly, expensive quantum mechanical (QM) calculations. While QM/MM simulations became common for mechanistic studies in enzymology, they still remain computationally expensive.17−24 It follows that implementation of the approach discussed above should rely on computed binding free energies and subsequent estimate of the activation energy based on an experimental LFER. However, the computational description of complex formation for an interfacial enzyme reaction is not trivial. In the case of cellulases, there are still many open questions regarding their interplay with the surface of the solid substrate.25 Computational methods have previously been used to probe these interfacial interactions on a molecular level.26−41 This type of work has provided important mechanistic insights, but the setup of large enzyme–substrate systems with multiple domains and phases remains cumbersome and their study computationally expensive. While binding and QM/MM calculation have been reported for single domain cellulases on a shorter substrate,26,30,33,35,37,38 the same has not yet, to the best of our knowledge, been feasible for multidomain cellulases in complex with their native, insoluble substrate.

The exploitation of experimental LFERs in computational analysis of enzymes will require robust methods to estimate binding energies of multidomain, interfacial enzymes with low computational cost. One established method is the so-called linear interaction energy (LIE) approach.42−51 LIE approximates the free energy of binding from the end states via linear-response approximations. It utilizes the average electrostatic and van der Waals (vdW) interaction energies from MD simulations. A common form of the classical LIE equation is

| 1 |

where α is the scaling factor for the van der Waals interactions (vdW), β is the scaling factor for the electrostatic interaction (Coul), γ is an offset parameter, and ΔUi is the change in internal energy for the energy term i compared to a reference.49 LIE parameters are obtained empirically—either from the literature or through fitting to experimental data.52 LIE has successfully predicted binding free energies of small molecules to proteins,42,44,45,47−49 but we are unaware of earlier applications to multidomain proteins and surface binding.

Many cellulases have a modular structure (see Figure 2) consisting of a catalytic domain (CD) and a noncatalytic carbohydrate-binding module (CBM) connected by a flexible linker.55−59 CBMs adsorbs to the cellulose surface and hence promotes the proximity of the enzyme and the substrate. Once adsorbed, the CD abstracts a single cellulose chain from the cellulose crystal and binds it in an extended cleft before it hydrolyzes a glycosidic bond. Depending on the type of cellulase, the catalytic cleft has a different degree of openness60 and a varying number of glucopyranose subsites to accommodate multiple monomers of the polymeric substrate.25

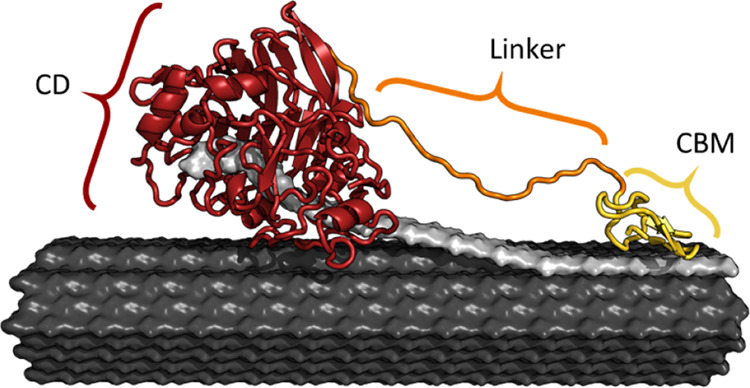

Figure 2.

Illustration of cellobiohydrolase (CBH) I from glycoside hydrolase (GH) family 7 from Trichoderma reesei (Tr), abbreviated as TrCel7A, bound to a cellulose fibril53 (black). The enzyme consists of a catalytic domain (CD, red, PDB 4C4C 29), a linker (orange), and a carbohydrate-binding module (CBM, yellow, PDB 2MWK 54). The ligand is a single cellulose strand, abstracted from the fibril surface and threaded into the CD and is highlighted in gray.

In this study, we propose a two-domain LIE method (2D-LIE), which accounts for substrate interactions of both CD and CBM. This method may be used as a flexible and computationally inexpensive approach to assess cellulase binding strength. We demonstrate that the combination of 2D-LIE and an experimental LFER can be effective for in silico prediction of enzyme kinetic parameters. We envision that the approach can be more widely applicable both in attempts to assess the kinetics of uncharacterized isoenzymes identified, for example, through metagenomics and in computer-aided design of enzyme variants with improved kinetic properties.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. 2D-LIE Model

The classical LIE equation (eq 1) was expanded to include one electrostatic and one van der Waals term per protein domain. In the case of cellulases with two domains, this leads to a 2D-LIE model with

| 2 |

where αi (i = CD, CBM) is the van der Waals interaction scaling parameter of the domain i, βi is the electrostatic interaction scaling parameter, and Δ⟨Uij ⟩ is the change of the average internal energy of term j (j = Coul, vdW) of the domain i compared to the reference. In this work, a common reference within the data set was used, resulting in ΔΔG values relative to the reference (see the Supporting Information for further detail). LIE is usually applied for the assessment of the binding of a series of small molecules toward a common receptor. For cellulases, the substrate (cellulose) remains the same, while different enzymes are evaluated. The use of a common ligand alleviates possible systematic errors in the modeling of the still challenging carbohydrate–protein binding.61−63 Additionally, both simulations—CD in complex with polymeric cellononaose and CBM bound to a cellulose crystal—differ from typical small-molecule binding studies. Therefore, no empirical parameters from the literature could be used for the 2D-LIE model. Instead, the LIE parameters were obtained through fitting to experimental values. In the development of the 2D-LIE model, we made several assumptions. First, the 2D-LIE model does not include the linker (see Figure 2). The role of the linker has been found to be more complex than simple spacing between the CBM and CD, and its function is still not fully understood.64−66 Therefore, the linker is disregarded for simplicity. Second, the assumption is made that the unspecific binding of the CD toward the crystal surface is negligible compared to the productive binding of the threaded cellulose chain in the binding tunnel. Third, we do not include any glycosylation in our setup. Most of the glycosylation lies on the neglected linker and the glycosylation sites on the CD are located away from the binding tunnel.25

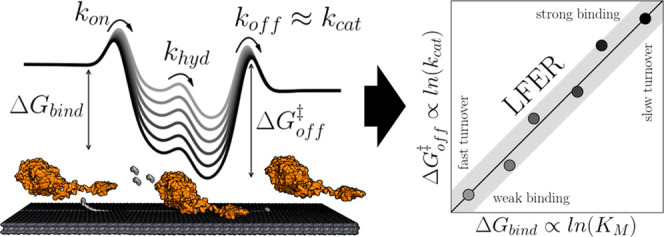

2.2. Data Set Preparation

For the development of the method, we used the recent kinetic data set from Kari et al.10 for cellulases. As the method does not account for any linker interaction, all variants with modifications in the linker from this set were disregarded. GH family 12 was disregarded due to the high outlier ratio in the experimental data set. This resulted in a data set of 65 cellulases (see Table S1 in the Supporting Information for a comprehensive list), which contained a diverse range of cellulases with different folds, catalytic mechanism (inverting/retaining), substrate preferences (reducing/nonreducing end), mode of attack (exo/endo acting), domain composition (with/without CBM), and organisms of origin (see Figure 3). All enzymes were of fungal origin and about half were wildtypes. The remainder were different types of variants made with the overall purpose of adjusting the substrate binding strength. The reported Michaelis constant KM and maximal turnover number kcat = Vmax/E0 were converted to the corresponding binding or activation free energies using the standard approach10,11,67

| 3 |

where κ is either KM or kcat. As a reference (κref), we used the parameters KM,ref and kcat,ref from Cel6A of T. reesei. TrCel6A is a well-characterized cellulase and its binding strength lies in the middle of the investigated affinity range, making its experimental measurement easier and propagated errors smaller. It follows that all ΔΔG values reported below specify the difference with respect to TrCel6A.

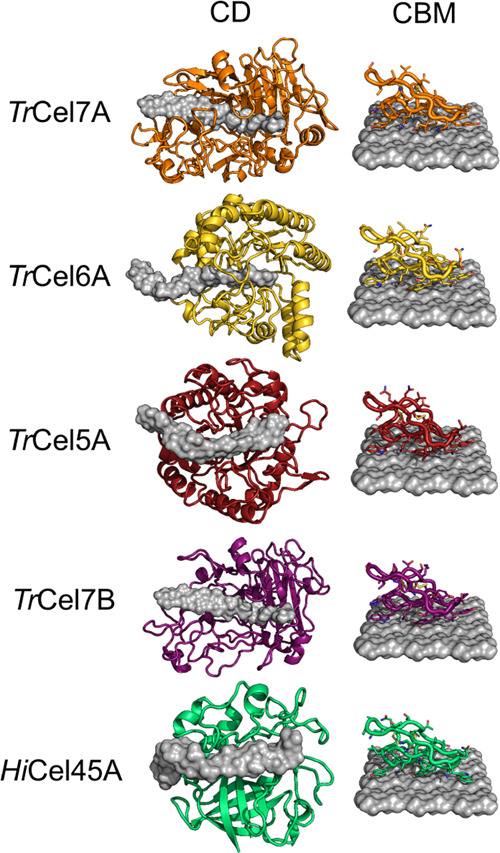

Figure 3.

Illustration of representatives from all GH families studied in this work. CDs bound to cellononaose are shown on the left, CBMs bound to a cellulose crystal on the right (all from CBM family 125). TrCel7A and TrCel6A are processive cellobiohydrolases (CBHs) with a closed binding tunnel, while TrCel7B, HiCel45A, and TrCel5A are endoglucanases (EGs) with a more open cleft.

2.3. Structure Preparation

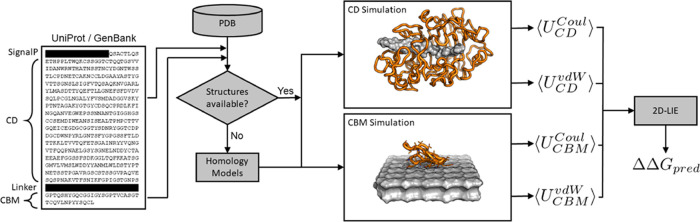

For all enzymes, UniProt68 or GenBank69 entries were gathered and simulations for the CDs were set up. All sequences were run through InterProScan (5.39–77.0)70,71 and searched against the Superfamily database.72 If a CBM was found, an additional simulation was set up for this domain. If available, a crystal structure (CS) was taken from the Protein Data Base (PDB).73 For the majority of enzymes, no crystal structure was available (47 out of 65 CDs, 25 out of 42 CBMs), and the partial sequences annotated to contain the domains were used for homology modeling (HM) with MODELLER (2.2.00).74−77 All CD systems were simulated bound to a cellononaose ligand. CBM systems were initialized unbound above the cellulose surface. Figure 4 provides a processing scheme, and further details concerning the structure preparation can be found in the Supporting Information.

Figure 4.

Schematic illustration of the preparation process for a two-domain protein (here TrCel7A) for the 2D-LIE approach.

2.4. General MD Settings

The CHARMM36 force field was used to describe all systems.78−81 The topologies for the nonaose ligand and the cellodecaose fibers of the crystal were prepared with the CHARMM GUI.82 All simulations were run in GROMACS (2018.6).83−89 Boxes with minimal edge distances of 1.4 nm were constructed and solvated with TIP3P water (see the Supporting Information for structure preparation).90 To neutralize the net charge of the system, random water molecules were exchanged with ions. All minimization steps were done in a steepest-descent over 10 000 iterations. A time step of 2 fs was used. The long-range electrostatics were treated with the particle-mesh Ewald method with a cubic interpolation and a cutoff of 12 Å.91 Van der Waals interactions were treated in a Verlet scheme with a cutoff distance of 12 Å and a switching function for the forces starting at 10 Å.92 Hydrogen bonds were restrained using the LINCS algorithm.93 The solutes and the solvent were coupled to individual heat baths with a Berendsen thermostat.94 Pressure coupling was done with a Parrinello–Rahman barostat.95 Analysis of the trajectories was performed with GROMACS. The trajectories were visualized in PyMOL (2.3.3).96

2.5. Simulations of the CD Systems

Minimization was conducted in three steps: First, keeping all solutes restrained. Second, keeping only the protein restrained. Lastly, allowing the complete system to move freely. Afterward, NVT simulations with incremental temperature (100–300 K in 50 K steps) were performed in succession for 20 ps each with restrains on the solute. Thereafter, NPT simulations with and without restraints on the solute were performed for 100 ps in series. The production was run in the NPT ensemble at 300 K for 10 ns without any restrains applied and energies were recorded every 10 ps. This simulation length was chosen, as the increase of performance of the method levels out at this time scale (see the Supporting Information).

2.6. Simulations of the CBM Systems

The CBM systems were treated in a similar fashion than the CD systems but with a few differences. During the second minimization, only the crystal was restrained. During all simulations, restrains were applied to the crystal. After the NPT equilibration with restrains on the solute, a soft-docking step was inserted by performing a steered MD (SMD) simulation. The pull rate was set to −0.01 nm/ps along the direct connection of the center of masses of the crystal and the CBM in all dimensions. The SMD was performed over 200 ps. Afterward, the same workflow as for the CD was resumed.

2.7. Analysis

The 2D-LIE fit and subsequent analysis were performed with Python (3.7.3).97 The first 100 ps were disregarded and the average energy terms over the rest of the production simulation were extracted from the GROMACS output files. For the CD, the electrostatic and van der Waals interaction energy terms between the ligand and its surroundings as well as the ligand with itself were extracted. For the CBM simulation, the energy terms between the protein and its surroundings were taken. The usage of different LIE terms per domain has several advantages. It equalizes the different energy terms taken per domain and allows individual weighing of the binding contribution for each domain. The sign for UCBMvdW changes as compared to the corresponding CD term, which is captured by the scaling parameter. The CD simulations and CBM simulations were normalized by subtracting the energy values obtained from the TrCel6A CD simulation and TrCel6A CBM simulation, respectively. The multidimensional fit was performed with SciPy (1.5.2).98

3. Results and Discussion

The energies obtained from the simulations were used to fit 2D-LIE models to the binding free energies derived from KM and to the activation free energies derived from kcat according to eq 3. For fitting, three different approaches were employed—first, a global fit to all investigated cellulases; second, a 5-fold cross-validation (CV) over the data set; and lastly, a fit toward a small representative subset of well-known enzymes from model organisms.25 The subset consisted of seven enzymes from the industrially relevant fungi T. reesei and Humicola insolens (Hi), specifically TrCel6A (WT and a CBM-less variant), TrCel7A (WT and a CBM-less variant), TrCel7B, TrCel5A, and HiCel45A.25 The three types of approaches (subset/CV/global) were applied using two different sets of experimental values (KM and kcat). This resulted in six sets of 2D-LIE parameters (see Table 1). The parameters obtained by the fittings were used to predict the binding of the remaining cellulases.

Table 1. 2D-LIE Parameters (Equation 2), Root-Mean-Square Errors (RMSEs), and Pearson’s Correlation Coefficients (r2) Obtained through Fits to the Complete Data Set (Global), 5-Fold Cross-Validation (CV), or a Small Representative Subseta.

| exp. | fit | αCD | βCD | αCBM | βCBM | γ | RMSE [kJ/mol] | r2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KM | subset | 0.286 ± 0.042 | 0.094 ± 0.063 | 0.054 ± 0.015 | –0.008 ± 0.003 | –0.119 ± 0.946 | 1.914 | 0.76 |

| global | 0.298 ± 0.031 | 0.131 ± 0.018 | 0.047 ± 0.011 | –0.006 ± 0.002 | –0.686 ± 0.339 | 1.827 | 0.78 | |

| CV | 0.30(11) | 0.131(11) | 0.047(3) | –0.006(4) | –0.68(12) | 1.85(11) | 0.776(24) | |

| kcat | subset | 0.226 ± 0.054 | 0.078 ± 0.082 | 0.034 ± 0.019 | –0.006 ± 0.004 | –0.016 ± 1.229 | 1.582 | 0.75 |

| global | 0.233 ± 0.024 | 0.105 ± 0.014 | 0.032 ± 0.009 | –0.004 ± 0.002 | –0.891 ± 0.266 | 1.433 | 0.77 | |

| CV | 0.23(1) | 0.11(1) | 0.032(3) | –0.004(8) | –0.89(11) | 1.45(1) | 0.767(3) |

For the global and subset cases, error estimation of the fitting parameters are provided. For the 5-fold cross-validation, the standard deviation is reported. For the subset fitting and cross-validation, RMSEs and correlation coefficients were derived from nonfitted entries.

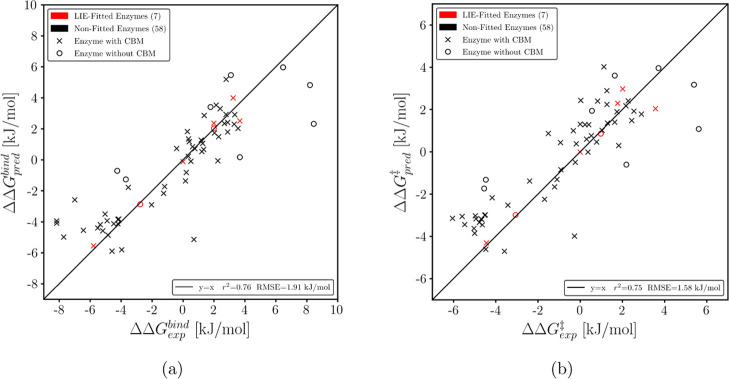

3.1. Binding Energy Prediction

Binding strengths were derived from the subset scaled with experimental values (eq 3) with the Pearson’s correlation coefficient of r2 = 0.76 and a root-mean-square error (RMSE) of 1.91 kJ/mol for the binding energy (see Figure 5a). The 5-fold CV resulted in r2 = 0.78 and RMSE of 1.85 kJ/mol. A global fit over all 65 cellulases resulted in r2 = 0.78 and RMSE of 1.85 kJ/mol. For all three cases, the RMSE was around the typical accuracy of LIE models.52 The obtained 2D-LIE parameters and performance indicators can be found in Table 1 and the corresponding binding energy results in Table S2 (Supporting Information).

Figure 5.

(a) Predicted binding free energies and (b) predicted free activation energies from the 2D-LIE models versus the experimental values. A small representative subset was used to derive the fitting parameters.

3.2. Activation Energy Prediction

The prediction of activation free energies derived from the subset resulted in r2 = 0.75 and RMSE of 1.58 kJ/mol (see Figure 5b). The 5-fold CV resulted in r2 = 0.77 and RMSE of 1.45 kJ/mol. The model derived from the global fit yielded r2 = 0.77 and RMSE of 1.43 kJ/mol. As shown previously, the RMSE is around the typical accuracy of LIE models for all three cases.52 Overall, the parameters and the results show the same trend as for the prediction of the binding energy. The performances of the models are comparable to the ones of the previous models for the binding free energies, even though the underlying experimental measure is more error prone.

3.3. Parameters and Performance

All three approaches (subset/CV/global) yielded very similar fitting parameters and performances for both target values (KM/kcat). Especially, the low standard deviation of the parameters and performance indicators for the CV indicate that the fit is very robust. The performance of the subset fitting cases was quite similar to the global/CV approach, indicating that it is possible to build a rather robust 2D-LIE model from an experimental data set of a manageable size.

The van der Waals scaling factors (αCD) seem reasonable as similar values have been reported for other systems.49,99 For the β electrostatic scaling factor, Hansson et al.42 observed that hydroxyl groups lower the parameter. They found β = 0.43 for apolar compounds, β = 0.37 for compounds bearing a single hydroxyl group, and β = 0.33 for compounds bearing multiple hydroxyl groups. Therefore, low βCD values for cellononaose with a multitude of hydroxyl groups seem reasonable. The CBM simulations (small proteins bound to a crystalline surface) are a further stretch from the known application of LIE for small-molecule drugs and cannot be readily compared to literature values. The CBM scaling factors αCBM and βCBM are smaller than the CD values, which is in line with the experimental observation that CBM contributes less to the binding free energy compared to the CD.12,15,100 The magnitude of βCBM is smaller compared to αCBM, which is in line with results in the literature38,101,102 and reflects that the crystal face pointing toward the CBM is hydrophobic and, therefore, the van der Waals terms of binding are more important than the electrostatic interactions in contrast to the CD.

3.4. Robustness and Transferability

To test the workflow, domains with available crystal structures (CS) were remodeled using the same approach and the obtained values were compared to those obtained from simulations with their crystal structures (see the Supporting Information). On average, a mean-absolute error MAECS↔HMbind,pred = 0.13 kJ/mol and an MAECS↔HM = 0.08 kJ/mol was observed between the prediction using the crystal structure and remodeling of the same. These changes are well below the general precision of the method and illustrate the robustness of the workflow as well as the ease of modeling of these well-studied enzyme families.

The built 2D-LIE models with their parameters and their predictive capability should work for all enzymes for which the underlying experimental LFER holds. As Kari et al.10 state, this should be the case for all cellulases. Predictions for values at different experimental conditions would require a new fitting to experimental values at these conditions or even new simulations (e.g., different temperature). While this is admittedly a narrow use case, our intention within this work is to present a broader, more general applicable approach to computationally predict kinetic parameters of heterogeneous enzymes as a whole, rather than the direct usage of the specific obtained parameters. Still, the prediction of kinetic properties of cellulases, in particular, is interesting for the industry. Furthermore, Kari et al.10 claim a general occurrence of LFERs for heterogeneous enzyme–substrate systems and, therefore, a similar approach to in silico to predict their kinetics should be applicable. Beyond the prediction of catalytic rates by assessment of binding strength, the 2D-LIE approach itself can potentially be used to model the binding of multidomain proteins, which constitute 65% of all eukaryotic proteins.103 Naturally, the basic split approach of the method is more sensible for proteins with loosely connected domains acting on different parts of the substrate.

3.5. In Silico Prediction of Kinetic Parameters

To illustrate the application of this model, the two major cellulases from GH family 7 of the industrial workhorse Aspergillus niger 104 were investigated, as detailed in the Supporting Information. The 2D-LIE parameters obtained from the global fit were used to predict KM and kcat for both enzymes. Even though they differ in modularity (±CBM), we found quite similar values for the kinetic parameters (see Figure 6). No experimental kinetic parameters are available for these enzymes and we await such data for further assessment of the approach. Prediction of parameters at experimental conditions different from those used in the underlying experiments10 would require new experiments to establish the relevant scaling relation.

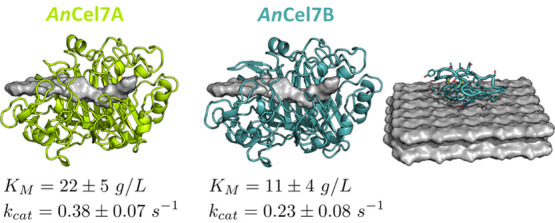

Figure 6.

Homology models of the investigated CBHs from A. niger with the predicted catalytic rates and Michaelis–Menten constants.

4. Conclusions and Outlook

Heterogeneous enzyme reactions are widespread in the nature and industry, but compared to bulk processes, they are generally poorly understood on the molecular level. This deficiency is linked to the complexity of interfacial reaction mechanisms29,105 but also reflects a shortage of rigorous and comparative kinetic data. This shortage results from limitations of both assays technologies and kinetic theory, and there is currently no generally accepted rate equation for enzyme reactions at interfaces. As a result, structure–function relationships remain poorly developed compared to bulk enzymology. Here, we addressed this by proposing an in silico method for the assessment of kinetic parameters of cellulases acting on their insoluble substrate. The approach relies on the recent experimental observation of an LFER10 for a wide group of cellulases with different structures and mechanisms. When this type of scaling indeed occurs, the computationally challenging task of determining the activation free energies for different enzymes can be replaced by more tractable assessments of binding energy. Subsequently, calculated binding free energies are readily linked to activation free energies through the LFER (see Figure 1), and estimated values of KM and kcat can be derived. However, the practical importance of this strategy relies on the availability of robust and computationally cheap methods to quantify binding strength in silico. Such (fast) methods have the potential to cover reasonable sequence spaces and hence assess the function of many wildtypes or potential enzyme variants. Here, we investigated the potential of an LIE-based approach in this regard. We found that LIE principles could be expanded to compute binding strengths of two-domain cellulases on the surface of their natural, insoluble substrate (2D-LIE). The proposed method is computationally relatively inexpensive,52 and in combination with homology modeling and the experimental LFER, it allows rapid in silico prediction of KM and kcat for cellulases belonging to different structural and mechanistic classes. Computational convenience was obtained through a number of simplifying assumptions including negligible nonspecific adsorption to the solid surface of both linker and CD. Extensive testing against a large data set suggested that the 2D-LIE method was able to reproduce experimental binding strengths, and this supported the validity of the underlying assumptions. Henceforth, the method could be used for exploratory screening of interfacial enzymes with known substrate specificity and with unknown kinetic parameters, provided an LFER can be established. We demonstrated this aspect by computationally predicting the kinetic parameters of the GH family 7 enzymes of the industrially relevant fungus A. niger. The principle of using LFER as a means to simplify computational methods for catalyst design came from the field of inorganic heterogeneous catalysis.9 While many differences between this field and heterogeneous biocatalysis may be identified, we propose that the common occurrence of LFER reflects general properties and limitations of interfacial catalysis. This generality may call for optimism regarding the implementation of principles from heterogeneous catalysis within interfacial enzymology. Moreover, it may infer that linear scaling relations are common and hence exist for other interfacial enzymes than cellulases. If indeed so, the approach sketched out here could have broader importance in virtual screening of isoenzymes acting on insoluble substrates and as a tool for the design of efficient industrial enzymes. This approach is particularly attractive, if a rapid computational method for enzyme–substrate binding free energies can be developed, as this would open up for phenotypical assessments of larger sequence spaces and benefit both engineering and discovery of interfacial enzymes. The ability to assess biochemical parameters in silico also appears timely in light of the rapidly expanding gap between the wealth of protein sequence data on the one hand and limited records of biochemical characterization on the other.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Independent Research Fund Denmark (Grant number: 8022-00165B) and the Novo Nordisk Foundation (Grant number: NNF15OC0016606). The authors thank Benjamin Clausen and Josefine H. Andersen for their initial investigation of the applicability of the LIE method for cellulases. The simulations were carried out at the High-Performance Cluster at the Technical University of Denmark.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.0c05361.

The list of studied cellulases with general information and identifiers; additional information regarding the structure preparation; the table with detailed MD and LIE results for all studied cellulases; the derivation of the relative 2D-LIE equation; the influence of the simulation length; the testing of remodeled crystal structures; and further information about the prediction of enzymes from A. niger (PDF)

The authors declare the following competing financial interest(s): KB and KDT work for Novozymes, a major enzyme producing company.

Supplementary Material

References

- McLaren A. D.; Packer L.. Advances in Enzymology and Related Areas of Molecular Biology; Nord F., Ed.; Wiley, 2006; Vol. 33, pp 245–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirk O.; Borchert T. V.; Fuglsang C. C. Industrial enzyme applications. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2002, 13, 345–351. 10.1016/S0958-1669(02)00328-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ragauskas A. J.; et al. The Path Forward for Biofuels and Biomaterials. Science 2006, 311, 484–489. 10.1126/science.1114736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh R. S.; Singhania R. R.; Pandey A.. Advances in Enzyme Technology; Larroche C., Ed.; Elsevier, 2019; pp 1–40. [Google Scholar]

- Jeoh T.; Cardona M. J.; Karuna N.; Mudinoor A. R.; Nill J. Mechanistic Kinetic Models of Enzymatic Cellulose Hydrolysis—A Review. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2017, 114, 1369–1385. 10.1002/bit.26277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kari J.; Olsen J. P.; Jensen K.; Badino S. F.; Krogh K. B.; Borch K.; Westh P. Sabatier Principle for Interfacial (Heterogeneous) Enzyme Catalysis. ACS Catal. 2018, 8, 11966–11972. 10.1021/acscatal.8b03547. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sabatier P. Hydrogénations et déshydrogénations par catalyse. Ber. Dtsch. Chem. Ges. 1911, 44, 1984–2001. 10.1002/cber.19110440303. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nørskov J. K.; Studt F.; Abild-Pedersen F.; Bligaard T. Fundamental Concepts in Heterogeneous Catalysis. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 10404–10405. [Google Scholar]

- Nørskov J. K.; Bligaard T.; Rossmeisl J.; Christensen C. H. Towards the Computational Design of Solid Catalysts. Nat. Chem. 2009, 1, 37–46. 10.1038/nchem.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kari J.; et al. Physical constrains and functional plasticity of cellulases: Linear scaling relationships for a heterogeneous enzyme reaction. bioRxiv 2020, 105569 10.1101/2020.05.20.105569. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sousa S. F.; Ramos M. J.; Lim C.; Fernandes P. A. Relationship between Enzyme/Substrate Properties and Enzyme Efficiency in Hydrolases. ACS Catal. 2015, 5, 5877–5887. 10.1021/acscatal.5b00923. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sørensen T. H.; Cruys-Bagger N.; Borch K.; Westh P. Free Energy Diagram for the Heterogeneous Enzymatic Hydrolysis of Glycosidic Bonds in Cellulose. J. Biol. Chem. 2015, 290, 22203–22211. 10.1074/jbc.M115.659656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruys-Bagger N.; Tatsumi H.; Ren G. R.; Borch K.; Westh P. Transient Kinetics and Rate-Limiting Steps for the Processive Cellobiohydrolase Cel7A: Effects of Substrate Structure and Carbohydrate Binding Domain. Biochemistry 2013, 52, 8938–8948. 10.1021/bi401210n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruys-Bagger N.; Elmerdahl J.; Praestgaard E.; Tatsumi H.; Spodsberg N.; Borch K.; Westh P. Pre-steady-state Kinetics for Hydrolysis of Insoluble Cellulose by Cellobiohydrolase Cel7A. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 18451–18458. 10.1074/jbc.M111.334946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kari J.; Olsen J.; Borch K.; Cruys-Bagger N.; Jensen K.; Westh P. Kinetics of Cellobiohydrolase (Cel7A) Variants with Lowered Substrate Affinity. J. Biol. Chem. 2014, 289, 32459–32468. 10.1074/jbc.M114.604264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurašin M.; Väljamäe P. Processivity of Cellobiohydrolases Is Limited by the Substrate. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 169–177. 10.1074/jbc.M110.161059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu T.; Guo H.. Understanding Enzyme Catalysis Mechanism Using QM/MM Simulation Methods. In Mechanistic Enzymology: Bridging Structure and Function; American Chemical Society, 2020; Vol. 1357, pp 121–137. [Google Scholar]

- Magalhães R. P.; Fernandes F. S.; Sousa S. F. Modelling Enzymatic Mechanisms with QM/MM Approaches: Current Status and Future Challenges. Isr. J. Chem. 2020, 60, 655–666. 10.1002/ijch.202000014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ranaghan K. E.; Mulholland A. J.. Simulating Enzyme Reactivity: Computational Methods in Enzyme Catalysis; Tunon I.; Moliner V., Eds.; Royal Society of Chemistry, 2017; Vol. 9, pp 377–401. [Google Scholar]

- Romero-Rivera A.; Garcia-Borràs M.; Osuna S. Computational tools for the evaluation of laboratory-engineered biocatalysts. Chem. Commun. 2017, 53, 284–297. 10.1039/C6CC06055B. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kearns F. L.; Hudson P. S.; Boresch S.; Woodcock H. L. Methods for Efficiently and Accurately Computing Quantum Mechanical Free Energies for Enzyme Catalysis. Methods Enzymol. 2016, 577, 75–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Guevara F.; Avelar M.; Ayala M.; Segovia L. Computational Tools Applied to Enzyme Design—a review. Biocatalysis 2016, 1, 109–117. 10.1515/boca-2015-0009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Van Der Kamp M. W.; Mulholland A. J. Combined quantum mechanics/molecular mechanics (QM/MM) methods in computational enzymology. Biochemistry 2013, 52, 2708–2728. 10.1021/bi400215w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senn H. M.; Thiel W. QM/MM studies of enzymes. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2007, 11, 182–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payne C. M.; Knott B. C.; Mayes H. B.; Hansson H.; Himmel M. E.; Sandgren M.; Stahlberg J.; Beckham G. T. Fungal Cellulases. Chem. Rev. 2015, 1308–1448. 10.1021/cr500351c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J.; Wang X.; Xu D. QM/MM Study on the Catalytic Mechanism of Cellulose Hydrolysis Catalyzed by Cellulase Cel5A from Acidothermus cellulolyticus. J. Phys. Chem. B 2010, 114, 1462–1470. 10.1021/jp909177e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamre A. G.; Kaupang A.; Payne C. M.; Väljamäe P.; Sørlie M. Thermodynamic Signatures of Substrate Binding for Three Thermobifida fusca Cellulases with Different Modes of Action. Biochemistry 2019, 58, 1648–1659. 10.1021/acs.biochem.9b00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borisova A. S.; et al. Correlation of structure, function and protein dynamics in GH7 cellobiohydrolases from Trichoderma atroviride, T. reesei and T. harzianum. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2018, 11, 5. 10.1186/s13068-017-1006-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knott B.; Haddad Momeni M.; Crowley M.; Mackenzie L.; Gotz A.; Sandgren M.; Withers S.; Stahlberg J.; Beckham G. The Mechanism of Cellulose Hydrolysis by a Two-Step, Retaining Cellobiohydrolase Elucidated by Structural and Transition Path Sampling Studies. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 321. 10.1021/ja410291u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knott B. C.; Crowley M. F.; Himmel M. E.; Ståhlberg J.; Beckham G. T. Carbohydrate-protein interactions that drive processive polysaccharide translocation in enzymes revealed from a computational study of cellobiohydrolase processivity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 8810–8819. 10.1021/ja504074g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Momeni M. H.; et al. Structural, Biochemical, and Computational Characterization of the Glycoside Hydrolase Family 7 Cellobiohydrolase of the Tree-killing Fungus Heterobasidion irregulare. J. Biol. Chem. 2013, 288, 5861–5872. 10.1074/jbc.M112.440891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bu L.; Crowley M. F.; Himmel M. E.; Beckham G. T. Computational Investigation of the pH Dependence of Loop Flexibility and Catalytic Function in Glycoside Hydrolases. J. Biol. Chem. 2013, 288, 12175–12186. 10.1074/jbc.M113.462465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y.; Yan S.; Yao L. A Mechanistic Study of Trichoderma reesei Cel7B Catalyzed Glycosidic Bond Cleavage. J. Phys. Chem. B 2013, 117, 8714–8722. 10.1021/jp403999s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Y.; Beckham G. T.; Himmel M. E.; Crowley M. F.; Chu J.-W. Endoglucanase Peripheral Loops Facilitate Complexation of Glucan Chains on Cellulose via Adaptive Coupling to the Emergent Substrate Structures. J. Phys. Chem. B 2013, 117, 10750–10758. 10.1021/jp405897q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payne C. M.; Jiang W.; Shirts M. R.; Himmel M. E.; Crowley M. F.; Beckham G. T. Glycoside Hydrolase Processivity Is Directly Related to Oligosaccharide Binding Free Energy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 18831–18839. 10.1021/ja407287f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghatty Venkata Krishna P. K.; Alekozai E. M.; Beckham G. T.; Schulz R.; Crowley M. F.; Uberbacher E. C.; Cheng X. Initial Recognition of a Cellodextrin Chain in the Cellulose-Binding Tunnel May Affect Cellobiohydrolase Directional Specificity. Biophys. J. 2013, 104, 904–912. 10.1016/j.bpj.2012.12.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bu L.; Nimlos M. R.; Shirts M. R.; Ståhlberg J.; Himmel M. E.; Crowley M. F.; Beckham G. T. Product Binding Varies Dramatically between Processive and Nonprocessive Cellulase Enzymes. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 24807–24813. 10.1074/jbc.M112.365510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nimlos M. R.; Beckham G. T.; Matthews J. F.; Bu L.; Himmel M. E.; Crowley M. F. Binding Preferences, Surface Attachment, Diffusivity, and Orientation of a Family 1 Carbohydrate-binding Module on Cellulose. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 20603–20612. 10.1074/jbc.M112.358184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckham G. T.; Matthews J. F.; Peters B.; Bomble Y. J.; Himmel M. E.; Crowley M. F. Molecular-Level Origins of Biomass Recalcitrance: Decrystallization Free Energies for Four Common Cellulose Polymorphs. J. Phys. Chem. B 2011, 115, 4118–4127. 10.1021/jp1106394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckham G. T.; Matthews J. F.; Bomble Y. J.; Bu L.; Adney W. S.; Himmel M. E.; Nimlos M. R.; Crowley M. F. Identification of Amino Acids Responsible for Processivity in a Family 1 Carbohydrate-Binding Module from a Fungal Cellulase. J. Phys. Chem. B 2010, 114, 1447–1453. 10.1021/jp908810a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckham G. T.; et al. The O-Glycosylated Linker from the Trichoderma reesei Family 7 Cellulase Is a Flexible, Disordered Protein. Biophys. J. 2010, 99, 3773–3781. 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.10.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansson T.; Marelius J.; Åqvist J. Ligand binding affinity prediction by linear interaction energy methods. J. Comput.-Aided Mol. Des. 1998, 12, 27–35. 10.1023/A:1007930623000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutiérrez O. A.; Chavez M.; Lissi E. A Theoretical Approach to Some Analytical Properties of Heterogeneous Enzymatic Assays. Anal. Chem. 2004, 76, 2664–2668. 10.1021/ac049885d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su Y.; Gallicchio E.; Das K.; Arnold E.; Levy R. M. Linear interaction energy (LIE) models for ligand binding in implicit solvent: Theory and application to the binding of NNRTIs to HIV-1 reverse transcriptase. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2007, 3, 256–277. 10.1021/ct600258e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genheden S.; Ryde U. Comparison of the Efficiency of the LIE and MM/GBSA Methods to Calculate Ligand-Binding Energies. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2011, 7, 3768–3778. 10.1021/ct200163c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genheden S.; Ryde U. The MM/PBSA and MM/GBSA Methods to Estimate Ligand-Binding Affinities. Expert Opin. Drug Discovery 2015, 10, 449–461. 10.1517/17460441.2015.1032936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vosmeer C. R.; Pool R.; van Stee M.; Perić-Hassler L.; Vermeulen N.; Geerke D. Towards Automated Binding Affinity Prediction Using an Iterative Linear Interaction Energy Approach. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2014, 15, 798–816. 10.3390/ijms15010798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vosmeer C. R.; Kooi D. P.; Capoferri L.; Terpstra M. M.; Vermeulen N. P.; Geerke D. P. Improving the iterative Linear Interaction Energy approach using automated recognition of configurational transitions. J. Mol. Model. 2016, 22, 1–8. 10.1007/s00894-015-2883-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miranda W. E.; Noskov S. Y.; Valiente P. A. Improving the LIE Method for Binding Free Energy Calculations of Protein–Ligand Complexes. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2015, 55, 1867–1877. 10.1021/acs.jcim.5b00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rifai E. A.; Van Dijk M.; Vermeulen N. P.; Yanuar A.; Geerke D. P. A Comparative Linear Interaction Energy and MM/PBSA Study on SIRT1-Ligand Binding Free Energy Calculation. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2019, 59, 4018–4033. 10.1021/acs.jcim.9b00609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rifai E. A.; Ferrario V.; Pleiss J.; Geerke D. P. Combined Linear Interaction Energy and Alchemical Solvation Free-Energy Approach for Protein-Binding Affinity Computation. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2020, 16, 1300–1310. 10.1021/acs.jctc.9b00890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutiérrez-de-Terán H.; Åqvist J. Linear Interaction Energy: Method and Application in Drug Design. Comp. Drug Discovery Des. 2012, 819, 305–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomes T. C. F.; Skaf M. S. Cellulose-builder: a toolkit for building crystalline structures of cellulose. J. Comput. Chem. 2012, 33, 1338–46. 10.1002/jcc.22959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Happs R. M.; Guan X.; Resch M. G.; Davis M. F.; Beckham G. T.; Tan Z.; Crowley M. F. O-glycosylation effects on family 1 carbohydrate-binding module solution structures. FEBS J. 2015, 282, 4341–4356. 10.1111/febs.13500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henrissat B. A classification of glycosyl hydrolases based on amino acid sequence similarities.. Biochem. J. 1991, 280, 309–316. 10.1042/bj2800309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henrissat B.; Bairoch A. New families in the classification of glycosyl hydrolases based on amino acid sequence similarities. Biochem. J. 1993, 293, 781–788. 10.1042/bj2930781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henrissat B.; Bairoch A. Updating the sequence-based classification of glycosyl hydrolases. Biochem. J. 1996, 316, 695–696. 10.1042/bj3160695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies G.; Henrissat B. Structures and Mechanisms of Glycosyl Hydrolases. Structure 1995, 3, 853–859. 10.1016/S0969-2126(01)00220-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henrissat B.; Davies G. Structural and sequence-based classification of glycoside hydrolases. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 1997, 7, 637–644. 10.1016/S0959-440X(97)80072-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiano-Di-Cola C.; Røjel N.; Jensen K.; Kari J.; Sørensen T. H.; Borch K.; Westh P. Systematic Deletions in the Cellobiohydrolase (CBH) Cel7A from the Fungus Trichoderma reesei Reveal Flexible Loops Critical for CBH Activity. J. Biol. Chem. 2018, 294, 1807–1815. 10.1074/jbc.RA118.006699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fadda E.; Woods R. J. Molecular simulations of carbohydrates and protein–carbohydrate interactions: motivation, issues and prospects. Drug Discovery Today 2010, 15, 596–609. 10.1016/j.drudis.2010.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryce R.; Hillier I.; Naismith J. Carbohydrate-Protein Recognition: Molecular Dynamics Simulations and Free Energy Analysis of Oligosaccharide Binding to Concanavalin A. Biophys. J. 2001, 81, 1373–1388. 10.1016/S0006-3495(01)75793-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez S.; Tvaroška I.. Advances in Carbohydrate Chemistry and Biochemistry; Academic Press Inc., 2014; Vol. 71, pp 9–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badino S. F.; Bathke J. K.; Sørensen T. H.; Windahl M. S.; Jensen K.; Peters G. H.; Borch K.; Westh P. The Influence of Different Linker Modifications on the Catalytic Activity and Cellulose Affinity of Cellobiohydrolase Cel7A from Hypocrea Jecorina. Protein Eng., Des. Sel. 2017, 30, 495–501. 10.1093/protein/gzx036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payne C. M.; Resch M. G.; Chen L.; Crowley M. F.; Himmel M. E.; Taylor L. E. II; Ståhlberg J.; Stals I.; Tan Z.; Beckham G. T. Glycosylated Linkers in Multimodular Lignocellulose-Degrading Enzymes Dynamically Bind to Cellulose. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2013, 110, 14646–14651. 10.1073/pnas.1309106110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strobel K. L.; Pfeiffer K. A.; Blanch H. W.; Clark D. S. Engineering Cel7a Carbohydrate Binding Module and Linker for Reduced Lignin Inhibition. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2016, 113, 1369–1374. 10.1002/bit.25889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warshel A. Electrostatic origin of the catalytic power of enzymes and the role of preorganized active sites. J. Biol. Chem. 1998, 273, 27035–27038. 10.1074/jbc.273.42.27035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UniProt Consortium UniProt: a worldwide hub of protein knowledge. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, D506–D515. 10.1093/nar/gky1049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark K.; Karsch-Mizrachi I.; Lipman D. J.; Ostell J.; Sayers E. W. GenBank. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016, 44, D67–D72. 10.1093/nar/gkv1276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell A. L.; et al. InterPro in 2019: improving coverage, classification and access to protein sequence annotations. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, D351–D360. 10.1093/nar/gky1100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones P.; et al. InterProScan 5: genome-scale protein function classification. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 1236–1240. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson D.; Pethica R.; Zhou Y.; Talbot C.; Vogel C.; Madera M.; Chothia C.; Gough J. SUPERFAMILY—sophisticated comparative genomics, data mining, visualization and phylogeny. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009, 37, D380–D386. 10.1093/nar/gkn762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berman H. M. The Protein Data Bank. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000, 28, 235–242. 10.1093/nar/28.1.235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webb B.; Sali A. Comparative Protein Structure Modeling Using MODELLER. Curr. Protoc. Bioinf. 2016, 54, 1–5. 10.1002/cpbi.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiser A.; Do R. K. G.; Sali A. Modeling of loops in protein structures. Protein Sci. 2000, 9, 1753–1773. 10.1110/ps.9.9.1753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Šali A.; Blundell T. L. Comparative Protein Modelling by Satisfaction of Spatial Restraints. J. Mol. Biol. 1993, 234, 779–815. 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martí-Renom M. A.; Stuart A. C.; Fiser A.; Sánchez R.; Melo F.; Šali A. Comparative protein structure modeling of genes and genomes. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 2000, 29, 291–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackerell A. D.; et al. All-Atom Empirical Potential for Molecular Modeling and Dynamics Studies of Proteins. J. Phys. Chem. B 1998, 102, 3586–3616. 10.1021/jp973084f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guvench O.; Mallajosyula S. S.; Raman E. P.; Hatcher E.; Vanommeslaeghe K.; Foster T. J.; Jamison F. W.; MacKerell A. D. CHARMM Additive All-Atom Force Field for Carbohydrate Derivatives and Its Utility in Polysaccharide and Carbohydrate–Protein Modeling. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2011, 7, 3162–3180. 10.1021/ct200328p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raman E. P.; Guvench O.; MacKerell A. D. CHARMM Additive All-Atom Force Field for Glycosidic Linkages in Carbohydrates Involving Furanoses. J. Phys. Chem. B 2010, 114, 12981–12994. 10.1021/jp105758h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanommeslaeghe K.; et al. CHARMM general force field: A force field for drug-like molecules compatible with the CHARMM all-atom additive biological force fields. J. Comput. Chem. 2009, 31, 671–690. 10.1002/jcc.21367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jo S. K.; Taehoon K.; Vidyashankara I. G.; Wonpil I. CHARMM-GUI: A web-based graphical user interface for CHARMM. J. Comput. Chem. 2008, 29, 1859–1865. 10.1002/jcc.20945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berendsen H.; van der Spoel D.; Drunen R. GROMACS: A message-passing parallel molecular dynamics implementation. Comput. Phys. Commun. 1995, 91, 43–56. 10.1016/0010-4655(95)00042-E. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lindahl E.; Hess B.; van der Spoel D. GROMACS 3.0: a package for molecular simulation and trajectory analysis. Mol. Mod. Annu. 2001, 7, 306–317. 10.1007/s008940100045. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- van der Spoel D.; Lindahl E.; Hess B.; Groenhof G.; Mark A. E.; Berendsen H. J. C. GROMACS: Fast, flexible, and free. J. Comput. Chem. 2005, 26, 1701–1718. 10.1002/jcc.20291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hess B.; Kutzner C.; van der Spoel D.; Lindahl E. GROMACS 4: Algorithms for Highly Efficient, Load-Balanced, and Scalable Molecular Simulation. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2008, 4, 435–447. 10.1021/ct700301q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pronk S.; et al. GROMACS 4.5: a high-throughput and highly parallel open source molecular simulation toolkit. Bioinformatics 2013, 29, 845–854. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Páll S.; Abraham M. J.; Kutzner C.; Hess B.; Lindahl E. In Tackling Exascale Software Challenges in Molecular Dynamics Simulations with GROMACS, International Conference on Exascale Applications and Software; Springer: Cham, 2015; pp 3–27.

- Abraham M. J.; Murtola T.; Schulz R.; Páll S.; Smith J. C.; Hess B.; Lindahl E. GROMACS: High performance molecular simulations through multi-level parallelism from laptops to supercomputers. SoftwareX 2015, 1–2, 19–25. 10.1016/j.softx.2015.06.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jorgensen W. L.; Chandrasekhar J.; Madura J. D.; Impey R. W.; Klein M. L. Comparison of simple potential functions for simulating liquid water. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 1983, 79, 926–935. 10.1063/1.445869. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Darden T.; York D.; Pedersen L. Particle Mesh Ewald: An N log(N ) Method for Ewald Sums in Large Systems. J. Chem. Phys. 1993, 98, 10089–10092. 10.1063/1.464397. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Verlet L. Computer “Experiments” on Classical Fluids. I. Thermodynamical Properties of Lennard-Jones Molecules. Phys. Rev. 1967, 159, 98–103. 10.1103/PhysRev.159.98. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hess B.; Bekker H.; Berendsen H. J. C.; Fraaije J. G. E. M. LINCS: A linear constraint solver for molecular simulations. J. Comput. Chem. 1997, 18, 1463–1472. . [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Berendsen H. J. C.; Postma J. P. M.; van Gunsteren W. F.; DiNola A.; Haak J. R. Molecular dynamics with coupling to an external bath. J. Chem. Phys. 1984, 81, 3684–3690. 10.1063/1.448118. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bussi G.; Zykova-Timan T.; Parrinello M. Isothermal-isobaric molecular dynamics using stochastic velocity rescaling. J. Chem. Phys. 2009, 130, 074101 10.1063/1.3073889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schrödinger L. L.The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System; Schrödinger LLC, 2015.

- The Python Language Reference; Python Software Foundation: Amsterdam, Netherlands, 2010. http://www.python.org.

- Virtanen P.; et al. SciPy 1.0—Fundamental Algorithms for Scientific Computing in Python. Nat. Methods 2019, 17, 261–272. 10.1038/s41592-019-0686-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasanthanathan P.; Olsen L.; Jørgensen F. S.; Vermeulen N. P.; Oostenbrink C. Computational prediction of binding affinity for CYP1A2-ligand complexes using empirical free energy calculations. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2010, 38, 1347–1354. 10.1124/dmd.110.032946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ståhlberg J.; Johansson G.; Pettersson G.; New A. Model For Enzymatic Hydrolysis of Cellulose Based on the Two-Domain Structure of Cellobiohydrolase I. Nat. Biotechnol. 1991, 9, 286–290. 10.1038/nbt0391-286. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lehtio J.; Sugiyama J.; Gustavsson M.; Fransson L.; Linder M.; Teeri T. T. The binding specificity and affinity determinants of family 1 and family 3 cellulose binding modules. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2003, 100, 484–489. 10.1073/pnas.212651999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh N.; Warshel A. Absolute binding free energy calculations: on the accuracy of computational scoring of protein-ligand interactions. Proteins 2010, 78, 1705–1723. 10.1002/prot.22687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekman D.; Björklund A. K.; Frey-Skött J.; Elofsson A. Multi-domain proteins in the three kingdoms of life: Orphan domains and other unassigned regions. J. Mol. Biol. 2005, 348, 231–243. 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cullen D. The genome of an industrial workhorse. Nat. Biotechnol. 2007, 25, 189–190. 10.1038/nbt0207-189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg O. G.; Jain M. K.. Interfacial Enzyme Kinetics; Wiley, 2002; p 301. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.