Abstract

Objectives

To report frontline healthcare workers’ (HCWs) experiences with personal protective equipment (PPE) during the COVID-19 pandemic in the UK. To understand HCWs’ fears and concerns surrounding PPE, their experiences following its guidance and how these affected their perceived ability to deliver care during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Design

A rapid qualitative appraisal study combining three sources of data: semistructured in-depth telephone interviews with frontline HCWs (n=46), media reports (n=39 newspaper articles and 145 000 social media posts) and government PPE policies (n=25).

Participants

Interview participants were HCWs purposively sampled from critical care, emergency and respiratory departments as well as redeployed HCWs from primary, secondary and tertiary care centres across the UK.

Results

A major concern was running out of PPE, putting HCWs and patients at risk of infection. Following national level guidance was often not feasible when there were shortages, leading to reuse and improvisation of PPE. Frequently changing guidelines generated confusion and distrust. PPE was reserved for high-risk secondary care settings and this translated into HCWs outside these settings feeling inadequately protected. Participants were concerned about differential access to adequate PPE, particularly for women and Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic HCWs. Participants continued delivering care despite the physical discomfort, practical problems and communication barriers associated with PPE use.

Conclusion

This study found that frontline HCWs persisted in caring for their patients despite multiple challenges including inappropriate provision of PPE, inadequate training and inconsistent guidance. In order to effectively care for patients during the COVID-19 pandemic, frontline HCWs need appropriate provision of PPE, training in its use as well as comprehensive and consistent guidance. These needs must be addressed in order to protect the health and well-being of the most valuable healthcare resource in the COVID-19 pandemic: our HCWs.

Keywords: public health, qualitative research, COVID-19, health services administration & management

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first study to qualitatively explore healthcare workers’ (HCWs) experiences with personal protective equipment (PPE) in the UK during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The study combined three sources of data (interviews, policies and media) collected at different stages of the pandemic (prepeak, during the first peak and postpeak).

The interview study sample was limited in its representation of the experiences of Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic and community HCWs.

Due to restrictions accessing hospital sites during the pandemic, the study was not able to directly capture practices associated with PPE use.

Introduction

The provision of personal protective equipment (PPE) for frontline healthcare workers (HCWs) has become a defining problem of the COVID-19 pandemic.1 The demand for PPE has put global supply chains under unprecedented strain.2 In March 2020, the WHO called for rational PPE use and for global PPE manufacturing to be scaled up by 40%.3 This has led to concerns regarding inadequate provision of PPE and its impact on the protection of frontline HCWs. There have been widespread reports of HCWs across the world having to deliver care without adequate PPE.4 5 In an international survey in April 2020, over half of HCWs responded had experienced PPE shortages, nearly a third were reusing PPE and less than half had adequate fit-testing.6 In the UK, a third of respondents from a Royal College of Nurses (RCN) survey7 and over half from a British Medical Association (BMA) survey8 said they felt pressure to work without adequate PPE. Both surveys also raised concerns that HCWs identifying as Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic (BAME) and female may be disproportionately affected by PPE shortages. Additional concerns over impaired communication, physical discomfort, overheating and dehydration associated with PPE have also been raised.9 As of 20 July 2020, 313 HCWs had died from COVID-19 in the UK.10

Knowledge from previous epidemics highlights the importance of PPE for frontline HCWs to reduce the spread of disease, safeguard HCWs’ health and well-being, and maintain a sustainable health workforce to curb the outbreak.11 Adequate provision of PPE as well as clear guidance and training in its use help HCWs feel confident and prepared to deliver care.12 Previous epidemic research also highlights the value of understanding HCWs’ fears and concerns in order to support them on the frontline of an outbreak.13 Qualitative research methodologies are increasingly being used to inform response efforts. In the 2014 Ebola and 2015–2016 Zika outbreaks, qualitative research helped generate context-specific, real-time recommendations to improve the planning and implementation of response efforts.14

Research on the appropriate level of PPE for COVID-19 is still ongoing.15 SARS-CoV-2 is thought to be transmitted via respiratory, contact and airborne transmission.16 Respiratory and contact precautions recommended by Public Health England (PHE) when caring for suspected cases include a Fluid-Resistant (Type IIR) Surgical Face Mask (FRSM), apron, gloves and eye protection on risk assessment.17 Airborne precautions recommended when caring for patients requiring aerosol generating procedures (AGPs) are higher and include a filtering facepiece 3 (FFP3) respirator, long-sleeved disposable fluid-repellent gown, gloves and eye protection.17

PPE has become a critical issue for frontline HCWs in the COVID-19 pandemic but studies capturing HCWs’ experiences with PPE are lacking.18 The aims of this study were to determine (a) frontline HCWs’ experiences following local level (ie, trust) and national level (ie, government) PPE guidance, (b) concerns and fears among HCWs regarding PPE in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic and (c) how these experiences and concerns affected HCWs’ perceived ability to deliver care during the pandemic.

Methods

Design

This study was part of a larger ongoing study on frontline HCWs’ perceptions and experiences of care delivery during the UK COVID-19 pandemic.19 We used a rapid appraisal methodology with three sources of data, including telephone interviews with frontline staff, a policy review and media analysis (see table 1). A rapid qualitative appraisal is an iterative approach to data collection and analysis, which triangulates findings between multiple sources of data to develop an understanding of a situation.20 It was chosen for its ability to generate targeted research in a timely manner in order to help inform response efforts to complex health emergencies.14 The use of an intensive, team-based approach with multiple sources of data helped to increase insight and validity of results.21

Table 1.

Methods of data collection and analysis

| Type of data | Method of collection | Included sample | Method of analysis |

| Interviews | In-depth, semistructured telephone interviews were carried out with frontline staff. | 46 interviews conducted between 19 March 2020 and 7 July 2020. | Emerging findings summarised as RAP sheets. Verbatim transcripts were coded and data analysed using framework analysis. The coding framework was cross-checked by two researchers and we underwent a process of member checking. |

| Policies | PPE policies were selected from legislation.gov.uk, https://www.england.nhs.uk (NHS England) and https://www.gov.uk/ (Public Health England, Department of Health and Social Care) using search terms such as ‘COVID-19’ OR ‘coronavirus’ OR ‘corona.’ | 25 policies published between 1 December 2019 and 5 June 2020. | Data were extracted into Excel by hand, cross-checked by another researcher and analysed using the same analytical framework. |

| Media | Mass media data were collected through the LexisNexis database (using search terms such as ‘COVID-19’ OR ‘coronavirus’ OR ‘corona’) and hand searching. | 39 newspaper articles published between 15 March 2020 and 5 June 2020. | Data were extracted into Excel using the software Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap), cross-checked by a reviewer and analysed using the same analytical framework. |

| Social media data were collected through the software Meltwater25 and Talkwalker.28 | 145 000 English language social media posts made between 1 December 2019 and 31 May 2020. | Data were selected, coded and analysed, then integrated into the same analytical framework. |

NHS, National Health Service; PPE, personal protective equipment; RAP, Rapid Assessment Process.

Sampling and recruitment

We used purposive and snowball sampling to recruit HCWs from critical care, emergency and respiratory departments as well as redeployed staff from primary, secondary and tertiary care settings (see online supplemental appendix 1). They had a variety of experience, ranging from newly qualified to over 40 years working in the National Health Service (NHS). Participants were approached by clinical leads in their trusts to gather verbal consent for the research team to contact them via email. Participants were provided with a participant information sheet and, after filling out a consent form, had a telephone interview arranged.

bmjopen-2020-046199supp001.pdf (7.7KB, pdf)

Patient and public involvement

The study protocol and study materials were reviewed by the team’s internal patient and public involvement panel. The panel’s feedback was used to make changes in the research questions and study materials.

Data collection

Interviews

Forty-six in-depth, semistructured telephone interviews with frontline HCWs were carried out using a broad topic guide focusing on HCWs’ perceptions and experiences of the COVID-19 response effort with questions relating to PPE throughout (see online supplemental appendix 2). The use of interviews facilitated in-depth discussions and the broad topic guide allowed participants to focus on aspects that were important to them. It allowed participants to discuss their experiences with PPE on their own accord and in a variety of contexts. Interviews were carried out before, during and after the first peak of the pandemic, which allowed for experiences to be captured in real time. Demographic data were also collected through interviews. A multidisciplinary research team (including CV-P, KH, LM and SL-J) conducted the interviews. Informed, written consent was obtained from all participants. Interviews were audio recorded, transcribed verbatim and all data were anonymised. Emerging findings were summarised in the form of Rapid Assessment Process (RAP) sheets20 to increase familiarisation and engagement with the data.22 Interviews were included until data reached saturation, determined by no new themes emerging from RAP sheets.23

bmjopen-2020-046199supp002.pdf (61.1KB, pdf)

Policies

A review of 25 UK government policies and guidelines relating to PPE was carried out to contextualise HCWs’ experiences following PPE guidance using Tricco et al’s framework.24 SL-J, LM and KH selected policies that met the inclusion criteria (see online supplemental appendix 3), cross-checked and extracted data into Excel.

bmjopen-2020-046199supp003.pdf (39.8KB, pdf)

Media

A rapid evidence synthesis of 39 newspaper articles and 145 000 English language Twitter posts meeting the inclusion criteria (see online supplemental appendix 3) was carried out using the same methodology as the policy review.24 LA screened titles and full texts of mass media data with exclusions cross-checked by another researcher. SM and SV used the media monitoring software Meltwater25 to collect social media data using keyword searches on Twitter.

Data analysis

The study was informed by a theoretical framework derived from anthropological perspectives on the material politics of epidemic responses.26 All streams of data were analysed using the Framework Method,27 as this type of analysis has been effective for rapid qualitative appraisals in previous epidemics.14 Social media data underwent additional demographic, discourse and sentiment analysis using the software TalkWalker.28 The interview data were initially coded by KH and codes were cross-checked by CV-P and ND. We also underwent a process of member checking, whereby researchers shared emerging findings to cross-check interpretations. All sources of data were coded with the same analytical framework to triangulate findings between the different streams of data.

Results

This section presents the participant demographics (see table 2) and the main themes of the study summarised using examples from all streams of data (see table 3).

Table 2.

Participant demographics

| Sample (n=46) | Percentage total (%) | |

| Role | ||

| Doctor | 28 | 60.87 |

| Nurse | 8 | 17.39 |

| Medical associate professional* | 4 | 8.70 |

| Pharmacist | 2 | 4.35 |

| Dietician | 1 | 2.17 |

| Speech and language therapist | 1 | 2.17 |

| Clinical support staff | 1 | 2.17 |

| Management | 1 | 2.17 |

| Sector | ||

| Secondary and tertiary care (general and specialist hospitals) | 40 | 86.96 |

| Primary care† | 4 | 8.70 |

| Specialist community services† | 2 | 4.35 |

| Secondary and tertiary care specialities | ||

| Critical care and anaesthesia‡ | 27 | 67.50 |

| Respiratory and COVID-19 wards | 6 | 15.00 |

| Emergency medicine | 4 | 10.00 |

| Cancer specialist services | 1 | 2.50 |

| Palliative care | 1 | 2.50 |

| Infection prevention and control services | 1 | 2.50 |

| Redeployment status | ||

| Redeployed | 23 | 50.00 |

| Not redeployed | 23 | 50.00 |

| Ethnicity§ | ||

| White | 40 | 86.96 |

| Mixed or multiple ethnic groups | 3 | 6.52 |

| Asian or Asian British | 2 | 4.35 |

| Black, African, Caribbean or Black British | 1 | 2.17 |

| Total | 46 | 100 |

*Including physician associates, anaesthesia associates and advanced critical care practitioners.

†Redeployed or awaiting redeployment to secondary or tertiary care centres.

‡Including intensive care unit, intensive therapy unit, high-dependency unit.

§BAME is a term used in the UK to refer to individuals who identify as Black, Asian and from Minority Ethnic groups.

Table 3.

Summary of themes from all streams of data

| Main themes | Subthemes | Policy review | Media analysis | Illustrative interview quotes |

| Theme 1: PPE guidance and training — ‘We weren’t prepared enough’ |

Inconsistent guidance | PHE guidance changed on March 6 2020 to advise FRSM masks be used instead of FFP3 respirators when assessing or caring for suspected patientswith COVID-19.29 | Newspaper reports of HCWs expressing concerns about caring for suspected cases with FRSMs instead of FFP3 respirators. |

What is really difficult for staff is that they’re being told to use a certain level of PPE for suspected patients but they might be watching the television and seeing, either from our country or other countries, people looking after patients wearing complete gear—total hazmat suits—covered from top to toe. Then they’re saying, ‘I’m being given much less than that to go see patients’.’ (Doctor, Consultant) Some staff felt messages of what PPE is required, in what situations, that there was a little bit of distrust…If the advice keeps changing, are we getting the right message? And is this message safe? Which caused a bit of worry and anxiety for some of the staff because at the same time they were hearing on the press that colleagues in other hospitals were getting sick. (Senior nurse) The guidelines are created within an emergency context…but I think that at local level, there should be an interest into tailoring those guidelines to needs. (General practitioner) |

| The training gap | On 2 March 2020, all NHS organisations advised to provide HCWs with fit-testing and PPE training.34 | Newspaper reports of HCWs working in PPE without having received training. |

I haven’t had any training…some other nurses have been trained to use ventilators but there hasn’t been any PPE training or anything else at all. (Nurse) PPE training happened because of local engagement of clinicians rather than coming from the management…it is clinicians who have been coming knocking on the door saying we need to prepare and perform these trainings—that was strange, why didn’t that change come from the top? (Doctor, Consultant) |

|

| Theme 2: PPE supply— ‘If we’re not protected, we can’t protect the public’ |

Shortages | On 17 April 2020, PHE guidance changed to approve the reuse of PPE where there were acute shortages and it was safe to do so.33 | Newspaper reports of inadequate access to PPE, especially for BAME, woman and community HCWs. |

So, there were times, for instance, where you needed to go to the loo, but you didn’t want to waste PPE. (Doctor, Registrar) What I don't think was good was the PPE situation, begging for personal protective equipment, feeling guilty for asking for it, feeling guilty for raising our voices. (Medical associate professional) Some of the scrubs, there weren't enough small ones…and well, you wouldn't expect a six-foot man to wear something that would fit me.((Female) Doctor) We didn’t have family members coming in wearing PPE and seeing their relatives to say goodbye before they die, and we should have been able to facilitate that. (Doctor, Consultant) |

| Procurement | In a letter to Trust chief executives on 17 March 2020, NHS England stated that there are local distribution issues despite an adequate national supply of PPE.37 | HCWs using the ‘panorama’ hashtag on Twitter (n=2000 tweets), which referred to the BBC investigation on whether the government failed to purchase PPE for the national stockpile in 2009. |

I think the one thing that’s probably been the biggest challenge has been sourcing PPE…That was probably the single biggest anxiety-inducing thing for staff on the ground. We never got to the point where we ran out but there was always this sense that we don’t know where next week’s is coming from. And the Trust always did manage to find it, but it was complex. (Doctor, Consultant) So there has been provision of PPE but not necessarily always PPE that is as secure as it could be. (Senior nurse) |

|

| Risk of exposure | PHE guidance from 14 March 2020 advised HCWs who came into contact with a patientwith COVID-19 while not wearing PPE could remain at work unless they developed symptoms.39 | News reports attributing a lack of PPE to frontline HCWs falling ill and dying. |

They were saying that we were the ones that really should be using (PPE) and anyone who was in the room but is further away doesn't need it, because they're not at the mouth of the patient…you were begging to have more…you'd have to really make a stand and say well, ‘everybody in my team is wearing it.’ (Medical associate professional) The first thing to do is making sure the healthcare professional feels that they are not jeopardizing the life of their own families…don’t make them feel like a pawn in a bigger game, because sometimes we feel like we are obliged to do stuff to save the rest, but we are part of the rest too. (Doctor, Consultant) It was really scary because, it’s not just the patients…it’s the attitude towards the staff as well. They were treating anybody like you had it. I had an anaesthetist in the early days, when we weren't being given PPE, it was just like ‘don't come in, keep away from me’, and it was really difficult to work keeping apart from someone. It was like the way they treated you as well, as though you're infected so don't come near me. (Medical associate professional) |

|

| Theme 3: Challenges of delivering care in PPE—‘It’s necessary but it makes everything more difficult’ |

Physical effects | PHE guidance stated that HCWs should remain hydrated and be trained to recognise dehydration, fatigue and exhaustion while wearing PPE.33 | Staff nurse in a news report describes taking minimal breaks during their 12-hour shift to avoid changing out of PPE to access water or toilets. |

It’s hot, it’s sweaty, it’s inconvenient (Doctor, Consultant) The effort staff made for the patients, even though they were uncomfortable, overall was remarkable really. (Senior nurse) |

| Practical problems | On 12 March 2020, PHE guidance stated that FFP3 respirator, long-sleeved disposable fluid-repellent gown, gloves and eye protection must be worn for AGPs.65 | Consultant in a news report describes how PPE made treating patients significantly more difficult, obscuring their vision. | It makes it more difficult to go between patients. So, for example if there is an emergency in the non-coronavirus bay you can’t just leave. You have to take off all the PPE in a particular way to make sure you don’t contaminate yourself and then go to see what the emergency is. It causes a small delay that probably doesn’t make a difference, but psychologically it feels more stressful because you feel like it’s taking a lot longer. (Doctor, Registrar) | |

| Communication and connection | On 24 April 2020, PHE IPC guidance advised trusts that ‘visiting should be restricted to those assessed as able to wear PPE’.17 | Positive news reports of HCWs using PPE portraits (disposable photos of their faces on top of PPE) to overcome rapport problems with patients. |

I think it does make you feel very …dehumanized because you can’t recognize any of your colleagues. (Senior pharmacist) When you've got patients on the ward and they are stuck in a room on their own and everyone in the room is dressed in PPE and they can’t have their relatives visiting them that’s actually really frightening and stressful and will create problems for people. (Doctor, Consultant) |

AGPs, aerosol generating procedures; BAME, Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic; FFP3, filtering facepiece 3; FRSM, Fluid-Resistant (Type IIR) Surgical Face Mask; HCW, healthcare worker; IPC, infection prevention and control; NHS, National Health Service; PHE, Public Health England; PPE, personal protective equipment.

Participants

Participants represented a range of HCWs. A majority were doctors and nurses working in hospital settings and one HCW not working on the frontline (management role) was included for their expertise in infection prevention and control (IPC) services.

Theme 1: PPE guidance and training—‘We weren’t prepared enough’

Inconsistent guidance

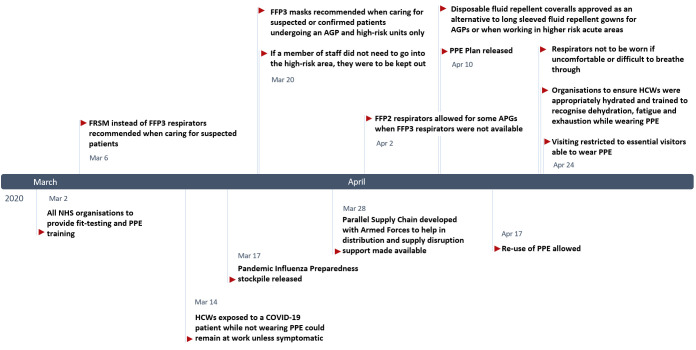

Towards the start of the outbreak, interviewed HCWs reported limited PPE guidance leading them to care for suspected patients with COVID-19 without appropriate PPE. All streams of data analysis found that national PHE and trust-level PPE guidance changed frequently (see figure 1), with daily changes reported in early April 2020. Inconsistent guidance led to confusion, distrust and a lack of confidence in the messaging.

Figure 1.

Timeline of changes to national PPE guidance during the first peak of the COVID-19 pandemic in the UK. AGPs, aerosol generating procedures; FFP3, filtering facepiece 3; FRSM, Fluid-Resistant (Type IIR) Surgical Face Mask; HCW, healthcare worker; NHS, National Health Service; PPE, personal protective equipment. High-risk areas: intensive care unit, intensive therapy unit, high-dependency unit.

On 6 March 2020, PHE recommended that FRSMs were to be used instead of FFP3 respirators when caring for suspected patients.29 On 20 March 2020, guidance stated that FFP3 respirators were only needed when managing suspected or confirmed patients, requiring one of their listed ‘potentially infectious AGPs’ and in high-risk units such as the intensive care unit, intensive treatment unit and high-dependency unit.30 On 2 April 2020, guidance changed to advise that if FFP3 respirators were not available, FFP2 respirators could be used instead for some AGPs.31 HCWs were concerned that this level of PPE was inadequate. Media analysis showed reports of HCWs being advised to wear single-layer paper surgical masks, instead of FRSMs or FFP3 masks while caring for suspected patients. HCWs felt PHE’s list of potentially infectious AGPs17 was not comprehensive enough, missing important potential AGPs, such as administering medication via nebulisation and performing chest compressions. HCWs were concerned about the change in PHE guidance on 10 April 2020,32 which allowed the use of coveralls with a disposable plastic apron for AGPs instead of full-length fluid-repellent gowns. Reports of PPE shortages in interviews and media analyses coincided with the 17 April 2020 PHE guidance, which changed to approve the reuse of PPE when there were acute shortages and it was deemed safe to do so.33 Having to reuse PPE was distressing, especially when sharing with colleagues. HCWs were concerned that the downgrading and frequent changes to guidance were grounded in supply problems.

As the pandemic progressed, some HCWs felt overwhelmed by increasing amounts of guidance from multiple sources. They felt that having a dedicated team to sort through the information would have increased its clarity. HCWs from community health services found interpreting PPE guidance catered towards hospital-based setting challenging. Senior HCWs were often involved in interpreting national guidance in the context of their local trust, liaising between staff and management. Some nurses felt as though their voices were not heard in the decision-making processes surrounding PPE guidance and supply on the ward. This was difficult for them as they spent most of their shifts in PPE. HCWs in interviews and the media were concerned about the UK guidance in comparison to other countries, where they felt higher levels of PPE were being provided to HCWs.

The training gap

Most interviewed HCWs in emergency medicine, critical care and anaesthesia reported adequate PPE training on how to safely don and doff PPE. However, some HCWs felt there was a ‘training gap’ and expressed the need for earlier, more accessible training available for a wider range of HCWs. Some HCWs reported having had PPE training during past epidemics, but most were unfamiliar with the PPE required for patients with COVID-19. On 2 March 2020, NHS England advised all organisations to provide HCWs with PPE training.34 Interviewed HCWs felt that PPE training was less accessible to HCWs working outside of high-risk units, such as general wards, surgery and primary care. Media analysis found that training was lacking for HCWs working in the community and in care homes. HCWs took initiative in teaching themselves to safely use PPE when training was neither available nor provided early enough. Having training available during both day and night shifts as well as online materials helped to make PPE training more accessible.

Theme 2: PPE supply—‘If we’re not protected, we can’t protect the public’

Shortages

HCWs in the media expressed concerns about PPE stockpiles running low from the beginning of March 2020. All streams of data analysis found reports of PPE shortages from across the UK, most notably in care homes, community health facilities and general practice. Visors, full-length fluid-repellent gowns and fluid-repellent facemasks were especially in short supply. One interviewed HCW described PPE being locked in an office with someone monitoring its use. In comparison to critical care staff, interviewed HCWs from general wards and those from smaller, less prominent hospitals reported greater barriers in access to PPE. Negative sentiment social media posts were mainly related to PPE shortages and towards a member of parliament who reported that care homes had adequate PPE. The positive social media posts were related to deliveries and donations. Informal help and resources advising on appropriate PPE use and how to adapt to limited supplies was shared on social media.

PHE guidance stated that respirators needed to be the correct size, fit-tested before use and that HCWs were not to proceed if a ‘good fit’ could not be achieved.35 Many HCWs reported failing their respirator fit-test and a lack of alternatives meant that they proceeded caring for patients with COVID-19 with these masks or used a lower level of protection. This was especially the case for female HCWs who experienced a lack of small sized masks and scrubs. Media analysis found reports of greater PPE supply problems for BAME HCWs. Powered air purifying respirator hoods (an alternative for HCWs with beards unable to shave for religious reasons) were especially lacking. Concerns were raised that nurses, healthcare assistants and physician associates faced greater barriers accessing PPE than doctors. HCWs were also concerned about the quality of PPE. Media analysis found that trusts, particularly in primary care, received shipments of out-of-date PPE. The policy review found that NHS England stated these shipments of outdated PPE had ‘passed stringent tests that demonstrate they are safe’.36

HCWs reported several adaptions to delivering care in order to preserve PPE, such as the use of open bays with multiple patients with COVID-19, and fewer HCWs seeing patients on ward rounds. Verbal prescriptions were used more frequently to avoid entering the COVID-19 bay and wasting PPE to write a prescription. The policy review found guidance on 20 March 2020 in response to concerns about mask shortages that stated, ‘if a member of staff does not need to go into the risk area, they should be kept out’.30 On 24 April 2020, PHE guidance advised that visiting should be restricted to essential visitors able to wear PPE.17 Some HCWs were concerned that PPE supply was a contributing factor limiting families visiting critically ill patients.

Procurement

On 17 March 2020, the Department of Health and Social Care announced that there were local PPE distribution problems despite a ‘currently adequate national supply’.37 On 10 April 2020, PHE released their PPE plan that explained that ‘there is enough PPE to go around, but it’s a precious resource and must be used only where there is a clinical need to do so’.38 They emphasised the importance of following national PPE guidance to reduce the significant pressure the supply chain was under. HCWs in interviews and media reported their facilities sourcing PPE at higher costs than usual. Some HCWs resorted to privately purchasing PPE and some trusts received PPE donations, including three-dimensional printed masks and visors. Extreme examples from the media included HCWs improvising PPE using children’s safety goggles, cooking aprons and bin liners. On social media, these concerns were expressed by HCWs using the ‘panorama’ hashtag on Twitter (n=2000 tweets), which referred to the BBC investigation on whether the government failed to purchase PPE for the pandemic influenza preparedness (PIP) stockpile in 2009. Even for interviewed HCWs that did not experience PPE shortages, the incremental basis of procurement was concerning for them. HCWs highlighted that facilities should have had prepared larger stockpiles and argued in favour of international collaboration on global PPE supply chains. Clear communication about PPE procurement and reassurance that stocks were adequate helped alleviate fears.

Risk of exposure

Interviewed HCWs feared that a lack of PPE increased their risk of exposure to COVID-19, especially for HCWs who had underlying conditions or were men, BAME, pregnant or been redeployed from retirement. Concerns were compounded by media reports of HCWs in other facilities catching COVID-19 due to insufficient PPE and subsequent exposure to high viral loads. This uncertainty was in the context of a lack of testing for HCWs, causing worries that they were spreading the virus between colleagues, patients and the public. Some HCWs described concerns regarding nosocomial transmission and a change in attitude between colleagues when there was a lack of PPE. A lack of cleaning and changing facilities meant that HCWs would wear potentially contaminated clothes home. HCWs expressed concerns about exposing vulnerable household or family members. The policy review found that on 14 March 2020, PHE advised that HCWs who came into contact with patients with COVID-19 while not wearing PPE could remain at work unless they developed symptoms.39 This policy was subsequently withdrawn on 29 March 2020. HCWs with infectious disease experience, working with adequate provision of PPE and those who had already been ill with COVID-19 reported less fear of exposure. As data collection progressed, HCWs became increasingly used to their new working environments, more familiar with using PPE and less afraid of catching COVID-19.

Theme 3: Challenges of delivering care in PPE—‘It’s necessary but it makes everything more difficult’

Physical effects

Interviewed HCWs described PPE to be tiring and uncomfortable to wear, making it more difficult to deliver care. The effects were pronounced for nurses who spent most of their shifts in PPE, and older HCWs with underlying conditions. Tight masks caused facial pain, marks and bruises, rashes, dry skin as well as difficulty in breathing, headaches and irritability. HCWs persisted in delivering care despite these effects, often against the PHE advice from 24 April 2020 that respirators ‘should be discarded and replaced, and not be subject to continued use’ when uncomfortable or difficult to breathe through.17 For some HCWs, the effects were so severe that they asked to be reassigned to non-COVID wards. Full-length gowns were hot and sweaty, causing overheating and dehydration. Conditions were exacerbated by HCWs fasting during Ramadan and warm weather. HCWs expressed the importance of breaks but often found it difficult to take them, especially on busy wards with shortages of staff and PPE. Wasting PPE on breaks generated feelings of guilt. Drinking less water to avoid having to take breaks made it difficult to follow guidance to remain ‘appropriately hydrated during prolonged use’.17

Practical procedures

HCWs found delivering care in PPE to be cumbersome. Donning and doffing PPE contributed to a slower delivery of care, and palpation during physical examinations was less effective with multiple layers of gloves. Goggles fogging up while performing procedures, such as intubation and administration of anaesthesia, was frustrating and stressful. Being in PPE-restricted HCWs' movements between patients and wards, junior HCWs, for example, found that, when in full PPE, they were less able to ask for help from seniors outside the COVID-19 bay not in PPE. HCWs needed to be more prepared than usual when going to see a patient requiring PPE, as they would be unable to leave without doffing and redonning PPE.

Communication and connection

HCWs found it more difficult to build rapport with patients as PPE limited facial expressions, physical touch and time spent with patients. Being in full PPE could be intimidating, especially for delirious patients. Some HCWs found it difficult to recognise colleagues and often had to shout to be heard through face masks. Communication problems arose with patients who were elderly and hard of hearing as they relied heavily on lipreading. HCWs in PPE found alternative forms of communication with colleagues outside of COVID-19 bays, such as portable radios. Some HCWs reported removing their masks when speaking about important topics such as gaining consent or breaking bad news. HCWs in interviews and media described overcoming rapport problems through use of disposable photos of themselves on their PPE (ie, disposable photos of their faces attached to gowns).

Discussion

This study found that HCWs faced multiple challenges delivering care including inadequate provision of PPE, inconsistent guidance and lack of training on its use. HCWs persisted delivering care despite the negative physical effects, practical problems, lack of protected time for breaks and communication barriers associated with wearing PPE. In the face of training, guidance and procurement gaps, HCWs improvised by developing their own informal communication channels to share information, trained each other and bought their own PPE.

To our knowledge, this is the first qualitative study reporting frontline HCWs’ experiences with PPE during the COVID-19 pandemic in the UK. It offers first-hand experiences from the perspective of HCWs and contributes to the ongoing research on PPE for frontline HCWs during the COVID-19 pandemic. Although our sampling framework aimed to seek the representation of participants across multiple professional backgrounds, our sample included a higher proportion of doctors. It was also limited in its representation of BAME and community HCWs’ experiences. The term BAME, although widely used in the UK, is limited in its specificity and representation of wider ethnic groups.

Participants in this study expressed the value of taking breaks to combat the physical effects of PPE but often found it difficult to do so as a result of staff shortages, heavy workloads and guilt over wasting PPE. HCWs reported similar effects of PPE being hot, tiring, time-consuming and restrictive in previous epidemics.40 41 In their sample of HCWs suffering from PPE-related skin problems, Singh et al42 found that 21% reported taking leave from work as a result of this. In addition to the implications for the workforce, they also raised concerns that skin breaches, irritation and increased touching of the face could act as a source of SARS-CoV-2 exposure.

Reducing the number of staff on COVID-19 wards to reduce PPE demand raised concerns about increased workloads and quality of care. PPE reduced HCWs’ ability to develop rapport with patients by masking facial expressions and impairing non-verbal and verbal communication. ‘PPE portraits’ have re-emerged in the COVID-19 pandemic after first being used in the 2014 Ebola outbreak to rehumanise care delivery and have positive anecdotal evidence from HCWs and patients.43

Some participants felt that PPE training was neither easily accessible nor implemented early enough. A third of HCWs who responded to a survey by the RCN reported on the eighth of May 2020 that they had not received PPE training.7 Studies on HCWs’ perceptions of working during previous infectious disease outbreaks highlight the importance of PPE training for HCWs to feel confident and prepared.44 45 Incorrect use of PPE exacerbates shortages and puts HCWs at higher risk of infection.46 Participants in this study described difficulties accessing training sessions between long shifts and raised concerns that HCWs outside of high-risk settings may experience less training. Previous research has also highlighted that during outbreaks, community HCWs tend to receive less PPE training and face greater difficulties following national guidance often directed towards hospital settings.47 48

Actual and perceived shortages were a major source of anxiety for participants in this study. They advocated for adequate PPE provision to protect their own health and safety. Similar fears of self-infection and transmission of SARS-CoV-2 to colleagues, patients and household members due to a lack of PPE have been reported among HCWs in China,9 the 49USA and Italy.50 Evidence on the safety of PPE reuse and extended use is limited but suggests that it can increase the risk of HCW self-infection and hospital transmission.46 This is particularly the case in the absence of clear guidance, protocols and a limited evidence base on best practice.51

Participants in this study were concerned by the downgrade in guidance from recommending FFP3 respirators to FRSMs29 as well as fluid-resistant full-length gowns to coveralls.32 They felt these changes were grounded in supply issues rather than safety measures. Current national guidance may be underestimating the risk of HCWs’ exposure to COVID-19 outside of high-risk settings, potentially resulting in inadequate protection for those HCWs.51 Prioritising higher levels of PPE for HCWs in high-risk areas is thought to have contributed to lower death rates among anaesthetists and intensivists.52 However, such an approach may be jeopardising the health and safety of HCWs working in lower risk areas.53 PHE guidance recommending FRSMs is lower compared with countries recommending higher level respirator masks (N95, FFP2 or FFP3), such as Australia, USA, China, Italy, Spain, France and Germany.51 UK HCWs working on COVID-19 wards following current PHE PPE guidance had nearly three times higher rates of asymptomatic infection compared with HCWs not in COVID-19 areas.54 While there are many possible explanations for these findings, an inadequate level of PPE was considered a contributing factor. A key challenge is that research on the transmission of SARS-CoV-2 and the lowest effective level of PPE is ongoing.55 Overuse of PPE uses up supplies and may increase risk of transmission through frequent changing, instilling a false sense of safety and potentially reducing the use of other important IPC measures.56 57 However, a recent systematic review and meta-analysis suggest that FFP3 respirators provide a higher level of protection against infection than FRSMs, even in the absence of AGPs.58 HCWs in a study in China experienced no infections with SARS-CoV-2 when provided with appropriate PPE training and supply, including ‘protective suits, masks, gloves, goggles, face shields and gowns’.15

Participants in this study raised concerns that women and BAME HCWs may face greater barriers accessing adequate PPE than other colleagues. During the 2015 Middle East Respiratory Syndrome outbreak in Korea, female HCWs faced similar challenges with oversized masks and coveralls.59 Despite only making up 21% of the NHS workforce, BAME HCWs have been overrepresented in the proportion of HCW deaths from COVID-19 in the UK, accounting for 63% of nurses and 95% medical staff deaths as of April 2020.60 Official inquiries into the underlying causes of these trends are ongoing.61 However, a recent study found that lack of access to PPE was perceived by BAME HCWs in the UK as a major factor contributing to the higher death rates.62 Recent studies suggest that in addition to being at greater risk of catching COVID-19, BAME HCWs are more likely to experience inadequate provision and reuse of PPE.46 A BMA survey in April 2020 found that only 40% of UK BAME HCWs working in primary care felt that they had adequate PPE compared with 70% of white HCWs.8 The same survey found that 64% of BAME HCWs felt pressure to work in AGP areas without adequate PPE compared with 33% of white HCWs.8

PPE provision for frontline HCWs has become a priority for response efforts across the world. The need for international collaboration to create sustainable and equitable global PPE supply chains is evident. In the UK, PPE procurement issues existed before the COVID-19 pandemic. The national stockpile was missing critical equipment, such as gowns, which have been short in supply during the pandemic.63 A delayed national response, limited domestic PPE manufacturing and exclusion from the EU commission procurement initiatives to secure PPE for its member states left the UK especially vulnerable to shortages.63 Knowledge from past epidemics highlights the importance of centralised procurement systems, monitoring PPE use and distributing according to the need.64

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was conducted by the Rapid Research Evaluation and Appraisal Lab (RREAL) at UCL. We would like to thank the support provided by Anna Dowrick, Anna Badley, Caroline Buck, Norha Vera, Nina Regenold, Kirsi Sumray, Georgina Singleton, Aron Syversen, Elysse Bautista Gonzalez, Lucy Mitchinson and Harrison Fillmore.

Footnotes

Twitter: @digitalcoeliac, @CeciliaVindrola

Contributors: CV-P designed the study, contributed to data collection, supervised data collection, analysis and reviewed different iterations of the manuscript. KH, LM, ND and SL-J contributed to the interviews. KH, LM and SL-J conducted the policy review. LA contributed to mass media data collection. SM and SV contributed to social media monitoring, data collection and analyses. KH conducted data analysis of all data and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. ND supervised data analysis and reviewed different iterations of the manuscript. All authors edited the manuscript and approved the final version.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: This study was approved by the Health Research Authority (HRA) and Health and Care Research Wales (HCRW) and the R&D offices of the hospitals where the study took place. IRAS project ID: 282069.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

References

- 1.World Health Organization Rational use of personal protective equipment for coronavirus disease (COVID-19) and considerations during severe shortages: interim guidance, 2020. Available: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/331695 [Accessed 10 Jun 2020].

- 2.Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development Africa’s Response to COVID-19: What roles for trade, manufacturing and intellectual property? Available: https://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/africa-s-response-to-covid-19-what-roles-for-trade-manufacturing-and-intellectual-property-73d0dfaf/ [Accessed 23 Jul 2020].

- 3.World Health Organization Shortage of personal protective equipment endangering health workers worldwide. Available: https://www.who.int/news-room/detail/03-03-2020-shortage-of-personal-protective-equipment-endangering-health-workers-worldwide [Accessed 28 Jul 2020].

- 4.Garber K, Ajiko MM, Gualtero-Trujillo SM, et al. . Structural inequities in the global supply of personal protective equipment. BMJ 2020;370:m2727. 10.1136/bmj.m2727 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ranney ML, Griffeth V, Jha AK. Critical supply shortages — the need for ventilators and personal protective equipment during the Covid-19 pandemic. N Engl J Med 2020;382:e41 10.1056/NEJMp2006141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tabah A, Ramanan M, Laupland KB, et al. . Personal protective equipment and intensive care unit healthcare worker safety in the COVID-19 era (PPE-SAFE): an international survey. J Crit Care 2020;59:70–5. 10.1016/j.jcrc.2020.06.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Royal College of Nurses Second personal protective equipment survey of UK nursing staff report: use and availability of PPE during the COVID-19 pandemic,. Available: https://www.rcn.org.uk/professional-development/publications/rcn-second-ppe-survey-covid-19-pub009269 [Accessed 10 Jun 2020].

- 8.British Medical Association BMA Covid Tracker survey – repeated questions. Available: https://www.bma.org.uk/news-and-opinion/bame-doctors-hit-worse-by-lack-of-ppe [Accessed 17 Aug 2020].

- 9.Liu Q, Luo D, Haase JE, et al. . The experiences of health-care providers during the COVID-19 crisis in China: a qualitative study. Lancet Glob Health 2020;8:e790–8. 10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30204-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Office for National Statistics Deaths involving the coronavirus (COVID-19) among health and social care workers in England and Wales, deaths registered between 9 March and 20 July 2020. Available: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/healthandsocialcare/causesofdeath/adhocs/12112deathsinvolvingthecoronaviruscovid19amonghealthandsocialcareworkersinenglandandwalesdeathsregisteredbetween9marchand20july2020 [Accessed 10 August 2020].

- 11.Fischer WA, Weber D, Wohl DA. Personal protective equipment: protecting health care providers in an Ebola outbreak. Clin Ther 2015;37:2402–10. 10.1016/j.clinthera.2015.07.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Houghton C, Meskell P, Delaney H, et al. . Barriers and facilitators to healthcare workers' adherence with infection prevention and control (IPC) guidelines for respiratory infectious diseases: a rapid qualitative evidence synthesis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2020;4:CD013582. 10.1002/14651858.CD013582 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Koh Y, Hegney DG, Drury V. Comprehensive systematic review of healthcare workers' perceptions of risk and use of coping strategies towards emerging respiratory infectious diseases. Int J Evid Based Healthc 2011;9:403–19. 10.1111/j.1744-1609.2011.00242.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Johnson GA, Vindrola-Padros C. Rapid qualitative research methods during complex health emergencies: a systematic review of the literature. Soc Sci Med 2017;189:63–75. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.07.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu M, Cheng S-Z, Xu K-W, et al. . Use of personal protective equipment against coronavirus disease 2019 by healthcare professionals in Wuhan, China: cross sectional study. BMJ 2020;369:m2195. 10.1136/bmj.m2195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.World Health Organization Transmission of SARS-CoV-2: implications for infection prevention precautions. Available: https://www.who.int/news-room/commentaries/detail/transmission-of-sars-cov-2-implications-for-infection-prevention-precautions [Accessed 8 Sep 2020].

- 17.Public Health England COVID-19: infection prevention and control guidance. Version 3, 2020. Available: https://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20200623134104/https://madeinheene.hee.nhs.uk/Portals/0/COVID-19%20Infection%20prevention%20and%20control%20guidance%20v3%20%2819_05_2020%29.pdf

- 18.Cook TM. Personal protective equipment during the COVID-19 pandemic - a narrative review. Anaesthesia 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vindrola-Padros C, Andrews L, Dowrick A, et al. . Perceptions and experiences of healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic in the UK. BMJ Open 2020;10:e040503. 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-040503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Beebe J. Rapid qualitative inquiry: a field guide to team-based assessment. Rowman & Littlefield, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Beebe J. Basic concepts and techniques of rapid appraisal. Hum Organ 1995;54:42–51. 10.17730/humo.54.1.k84tv883mr2756l3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vindrola-Padros C, Chisnall G, Cooper S, et al. . Carrying out rapid qualitative research during a pandemic: emerging lessons from COVID-19. Qual Health Res 2020;30:2192–204. 10.1177/1049732320951526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Saunders B, Sim J, Kingstone T, et al. . Saturation in qualitative research: exploring its conceptualization and operationalization. Qual Quant 2018;52:1893–907. 10.1007/s11135-017-0574-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tricco AC, Langlois E, Straus SE. Rapid reviews to strengthen health policy and systems: a practical guide. World Health Organization, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Meltwater Official website. Available: https://www.meltwater.com/en/products/social-media-monitoring [Accessed 17 Sep 2020].

- 26.Lynteris C, Poleykett B. The anthropology of epidemic control: technologies and materialities. Taylor & Francis,, 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gale NK, Heath G, Cameron E, et al. . Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. BMC Med Res Methodol 2013;13:117. 10.1186/1471-2288-13-117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Talkwalker Official website. Available: https://www.talkwalker.com/social-media-listening [Accessed 17 Sep 2020].

- 29.Public Health England COVID-19: infection prevention and control guidance, 2020. Available: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/wuhan-novel-coronavirus-infection-prevention-and-control

- 30.Public Health England FAQs on using FFP3 respiratory protective equipment (RPE), 2020. Available: https://www.england.nhs.uk/coronavirus/wp-content/uploads/sites/52/2020/03/faq-ffp3-24-march-2020.pdf

- 31.Public Health England New personal protective equipment (PPE) guidance for NHS teams, 2020. Available: https://www.gov.uk/government/news/new-personal-protective-equipment-ppe-guidance-for-nhs-teams

- 32.Public Health England Letter to the NHS trust CEOs, NHS trust medical directors, NHS directors of nursing and NHS trust procurement leads – re: agreement by health and safety executive for use of coveralls as an alternative option for non-surgical gowns, 2020. Available: https://www.england.nhs.uk/coronavirus/wp-content/uploads/sites/52/2020/04/C0284-ppe-gowns-letter-qa-sa.pdf

- 33.Public Health England Considerations for acute personal protective equipment (PPE) shortages, 2020. Available: https://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20200708170906/https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/wuhan-novel-coronavirus-infection-prevention-and-control/managing-shortages-in-personal-protective-equipment-ppe

- 34.NHS England and NHS Improvement Letter to chief executives of NHS trusts: COVID-19 NHS preparedness and response, 2020. Available: https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/20200302-COVID-19-letter-to-the-NHS-Final.pdf

- 35.Public Health England Putting on (donning) personal protective equipment (PPE) for aerosol generating procedures (AGPs) – gown version, 2020. Available: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/911333/PHE_COVID-19_Donning_Airborne_Precautions_gown_version__003_.pdf

- 36.NHS England and NHS Improvement Guidance on supply and use of PPE, 2020. Available: https://nhsprocurement.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/PPE-Letter-FINAL-20-March-2020.pdf

- 37.NHS England and NHS Improvement Letter to the Chief executives of the NHS trusts and foundation trusts, CCG Accountable officers, GP practices and Primary Care Networks and Providers of community health services - Next steps on nhs response to covid-19, 2020. Available: https://www.england.nhs.uk/coronavirus/wp-content/uploads/sites/52/2020/03/urgent-next-steps-on-nhs-response-to-covid-19-letter-simon-stevens.pdf

- 38.Department of Health and Social Care Covid-19: personal protective equipment (PPE) plan, 2020. Available: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/879221/Coronavirus__COVID-19__-_personal_protective_equipment__PPE__plan.pdf

- 39.Public Health England COVID-19: actions required when a case was not diagnosed on admission, 2020. Available: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/covid-19-guidance-for-healthcare-providers-who-have-diagnosed-a-case-within-their-facility/covid-19-actions-required-when-a-case-was-not-diagnosed-on-admission

- 40.Kim Y. Nurses' experiences of care for patients with middle East respiratory syndrome-coronavirus in South Korea. Am J Infect Control 2018;46:781–7. 10.1016/j.ajic.2018.01.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lam KK, Hung SYM. Perceptions of emergency nurses during the human swine influenza outbreak: a qualitative study. Int Emerg Nurs 2013;21:240–6. 10.1016/j.ienj.2012.08.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Singh M, Pawar M, Bothra A, et al. . Personal protective equipment induced facial dermatoses in healthcare workers managing coronavirus disease 2019. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2020;34:e378–80. 10.1111/jdv.16628 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Brown-Johnson C, Vilendrer S, Heffernan MB, et al. . PPE Portraits-a way to humanize personal protective equipment. J Gen Intern Med 2020;35:2240–2. 10.1007/s11606-020-05875-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wong TY, Koh GCH, Cheong SK, et al. . A cross-sectional study of primary-care physicians in Singapore on their concerns and preparedness for an avian influenza outbreak. Ann Acad Med Singap 2008;37:458–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wong JEL, Leo YS, Tan CC. COVID-19 in Singapore-Current experience: critical global issues that require attention and action. JAMA 2020;323:1243–4. 10.1001/jama.2020.2467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nguyen LH, Drew DA, Graham MS, et al. . Risk of COVID-19 among front-line health-care workers and the general community: a prospective cohort study. Lancet Public Health 2020;5:e475–83. 10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30164-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cheong SK, Wong TY, Lee HY, et al. . Concerns and preparedness for an avian influenza pandemic: a comparison between community hospital and tertiary hospital healthcare workers. Ind Health 2007;45:653–61. 10.2486/indhealth.45.653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zinatsa F, Engelbrecht M, van Rensburg AJ, et al. . Voices from the frontline: barriers and strategies to improve tuberculosis infection control in primary health care facilities in South Africa. BMC Health Serv Res 2018;18:269. 10.1186/s12913-018-3083-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shanafelt T, Ripp J, Trockel M. Understanding and addressing sources of anxiety among health care professionals during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA 2020;323:2133. 10.1001/jama.2020.5893 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Catania G, Zanini M, Hayter M. Lessons from Italian front‐line nurses’ experiences during the COVID‐19 pandemic: A qualitative descriptive study. J Nurs Manag 2020;27 10.1111/jonm.13194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Thomas JP, Srinivasan A, Wickramarachchi CS, et al. . Evaluating the National PPE guidance for NHS healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Clin Med 2020;20:242–7. 10.7861/clinmed.2020-0143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cook T, Kursumovic E, Lennane S. Exclusive: deaths of NHS staff from covid-19 analysed. Health Service J 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cao Y, Li Q, Chen J, et al. . Hospital emergency management plan during the COVID-19 epidemic. Acad Emerg Med 2020;27:309–11. 10.1111/acem.13951 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rivett L, Sridhar S, Sparkes D, et al. . Screening of healthcare workers for SARS-CoV-2 highlights the role of asymptomatic carriage in COVID-19 transmission. Elife 2020;9. 10.7554/eLife.58728. [Epub ahead of print: 11 May 2020]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Verbeek JH, Rajamaki B, Ijaz S, et al. . Personal protective equipment for preventing highly infectious diseases due to exposure to contaminated body fluids in healthcare staff. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2020;4:CD011621. 10.1002/14651858.CD011621.pub4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Steuart R, Huang FS, Schaffzin JK, et al. . Finding the value in personal protective equipment for hospitalized patients during a pandemic and beyond. J Hosp Med 2020;15:295–8. 10.12788/jhm.3429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nicolle L. SARS safety and science. Can J Anaesth 2003;50:983–8. 10.1007/BF03018360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chu DK, Akl EA, Duda S, et al. . Physical distancing, face masks, and eye protection to prevent person-to-person transmission of SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 2020;395:1973–87. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31142-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kang J, Kim EJ, Choi JH, et al. . Difficulties in using personal protective equipment: training experiences with the 2015 outbreak of middle East respiratory syndrome in Korea. Am J Infect Control 2018;46:235–7. 10.1016/j.ajic.2017.08.041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Illman J, Discombe M. Exclusive: deaths of NHS staff from covid-19 analysed. Available: https://www.hsj.co.uk/exclusive-deaths-of-nhs-staff-from-covid-19-analysed/7027471.article [Accessed 20 Jul 2020].

- 61.Iacobucci G. Covid-19: PHE review has failed ethnic minorities, leaders tell BMJ. BMJ 2020;369:m2264. 10.1136/bmj.m2264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Moorthy A, Sankar TK. Emerging public health challenge in UK: perception and belief on increased COVID19 death among BAME healthcare workers. J Public Health 2020;42:486–92. 10.1093/pubmed/fdaa096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Oehmen J, Locatelli G, Wied M, et al. . Risk, uncertainty, ignorance and myopia: their managerial implications for B2B firms. Industrial Marketing Management 2020;88:330–8. 10.1016/j.indmarman.2020.05.018 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Patel A, D'Alessandro MM, Ireland KJ, et al. . Personal protective equipment supply chain: lessons learned from recent public health emergency responses. Health Secur 2017;15:244–52. 10.1089/hs.2016.0129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Public Health England COVID-19: investigation and initial clinical management of possible cases, 2020. Available: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/wuhan-novel-coronavirus-initial-investigation-of-possible-cases/investigation-and-initial-clinical-management-of-possible-cases-of-wuhan-novel-coronavirus-wn-cov-infection

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2020-046199supp001.pdf (7.7KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2020-046199supp002.pdf (61.1KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2020-046199supp003.pdf (39.8KB, pdf)