Abstract

Background:

Disparities encountered by men and women physicians are well documented. However, evidence is lacking concerning the effects of gender on daily practice in the specialty of anesthesiology.

Aims:

To evaluate gender disparities perceived by female anesthesiologists.

Setting and Design:

Anonymous, voluntary 30-question, electronic secure REDcap survey.

Materials and Methods:

Survey link was sent via email, Twitter and the Facebook page, Physician Mom's Group. Instructions dictated that only female attending anesthesiologists participate and to partake in the survey one time.

Statistical Analysis:

Categorical variables were summarized using frequencies and percentages. Associations between categorical variables were tested using Chi-square test. Likert scale items were treated as continuous variables. T-tests were utilized to examine differences between those who reported burnout and those who did not.

Results:

502 survey responses were received and analyzed. Female leadership was valued by 78%, yet only 47% had leadership roles. Being female was identified by 51% as negatively affecting career advancement and 90% perceived that women in medicine need to work harder than men to achieve the same career goals. Sexual harassment was experienced by 55%. Nearly 35% of institutions did not offer paid maternity leave. Burnout was identified in 43% of respondents and was significantly associated with work-life balance not being ideal (P < 0.0001), gender negatively affecting career advancement (P < 0.0001), experiencing sexual harassment at work (P = 0.002), feeling the need to work harder than men (P = 0.0033), being responsible for majority of household duties (P = 0.0074), lack of weekly exercise (P = 0.0135) and lack of lactation needs at work (P = 0.0007).

Conclusions:

Understanding perceptions of female anesthesiologists may lead to actionable plans aimed at improving workplace equity or conditions.

Keywords: Burnout, child bearing, gender, lactation, sexual harassment

INTRODUCTION

Differences in workforce experiences are an inherent aspect of men and women working alongside each other. Physicians are not immune to these gender differences as 70%–77% of women physicians report gender discrimination during their careers.[1] The recent launching of TIME'S UP Healthcare has put gender equality issues from a medical perspective in the media and on social networking platforms.[2]

To date, there is a paucity of literature concerning gender-related perceptions and environmental factors associated with female staff in the specialty of anesthesiology. In order to continue advancing equality for women in anesthesiology and maintaining talented female anesthesiologists in the workforce, data are necessary to decipher the current roles and perceptions of female anesthesiologists.

We sought to determine characteristics and perceptions concerning gender-related issues in the field of anesthesiology through an anonymous, electronic survey. Specific elements of interest included leadership, burnout, work-life balance, and maternal and lactation logistics.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The university institutional review board approved this electronic survey study and adherence to the TREND guideline was followed. Secure REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture) tool (Vanderbilt University, TN, USA 2004) survey software was utilized to administer the survey [Table 1] and to prospectively collect data concerning gender issues in anesthesiology. The 30-question survey was anonymous, voluntary, targeted to only attending staff anesthesiologists identifying as female and was active for approximately 6 weeks.

Table 1.

Survey questions and answer data (n=502)*

| Binary questions | True, n (%) | False, n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| I received further subspecialty training following anesthesiology residency (ACGME or non-ACGME) | 317 (66) | 165 (34) | |

| Do you have children? | 397 (83) | 82 (17) | |

| I am a full-time employee of an anesthesiology department | 390 (82) | 85 (18) | |

| My role as a physician involves home/pager call | 351 (74) | 123 (26) | |

| I have departmental or hospital leadership responsibilities such as schedule making or as a division or department chief | 222 (47) | 251 (53) | |

| I have taken steps such as limiting my roles at work or working part-time due to the high level of emotional or physical stress placed on me by my work | 181 (38) | 293 (62) | |

| I have taken steps such as limiting my roles at work or working part-time not due to work-related stress, but due to demands of my home life | 197 (42) | 277 (59) | |

| Likert scale (5-point) questions | Agree or strongly agree, n (%) | Neutral, n (%) | Disagree or strongly disagree, n (%) |

| I am satisfied with my job choice and could not see myself in another area of medicine or another career | 298 (66) | 90 (20) | 65 (14) |

| I feel women in medicine need to work harder than men medicine to achieve similar goals | 409 (90) | 29 (6) | 17 (4) |

| I believe my gender has negatively affected my career advancement | 239 (52) | 107 (23) | 115 (25) |

| Overall, I feel that my work-life balance is ideal for me | 151 (33) | 105 (23) | 206 (45) |

| I feel my male colleagues appreciate having a female anesthesiologist in leadership positions | 120 (26) | 157 (34) | 167 (36) |

| I feel my female colleagues appreciate having a female anesthesiologist in leadership positions | 362 (78) | 59 (13) | 32 (0.07) |

| I feel my male colleagues react to my vocalized thoughts concerning medical practice similarly as they would react to a male vocalizing identical thoughts | 105 (23) | 86 (19) | 255 (56) |

| Concerning caring for patients and enacting plans, I feel the best operating room team composition includes more women than men | 107 (23) | 237 (52) | 105 (23) |

| I have experienced sexual harassment by a work colleague, e.g., unwanted touches or sexual comments/texts at some point in my career | 250 (55) | 32 (7) | 172 (38) |

| Outside of work, I am responsible for the majority of my household duties | 273 (60) | 67 (15) | 112 (25) |

| During a 7 days period, I participate in daily physical exercise | 160 (35) | 39 (9) | 254 (56) |

| Overall, my department is excited when a female staff announces a pregnancy | 145 (32) | 121 (27) | 163 (36) |

| The call schedule penalizes women for taking maternity leave, e.g., pay it forward with calls, etc. | 126 (28) | 71 (16) | 178 (39) |

| I feel the number of children I have or don’t have is related, in part, to my career choice | 230 (51) | 41 (9) | 164 (36) |

| My department strives to ensure antepartum safety by making reasonable accommodations in clinical assignments, e.g., avoidance of fluoroscopy anesthetic locations for pregnant staff, etc. | 264 (63) | 58 (14) | 97 (23) |

| My department strives to ensure ease with postpartum lactation needs, such as operating room relief when breast pumping is necessary and lactation room | 143 (32) | 82 (18) | 167 (37) |

| I did not breastfeed or pump breast milk for my baby due to concerns of workplace harm to my baby, e.g., anesthetic gases | 9 (0.02) | 18 (5) | 312 (80) |

| I did not breast feed due to inconveniences of pumping at work, e.g., time, space, equipment | 100 (26) | 36 (9) | 209 (54) |

| My hospital provides a lactation space that is suitable for my needs | 127 (33) | 48 (12) | 137 (35) |

*Totals don’t add up to 502 as not every question was answered by all participants

The survey link was disseminated by three mechanisms:

Personal email to anesthesiologists who identified themselves as champions at numerous academic institutions who then disseminated an email with an explanation and survey link to female anesthesiologists within their department on various dates initiating on April 1, 2019

Posting on the University of Kansas Anesthesia Critical Care Twitter feed @KU_CCM on April 2, 2019 (8073 impressions, 367 engagements, 152 clicks on link) and May 13, 2019 (182 impressions, 8 engagements, 3 clicks on link)

Posting on the Facebook group: Physicians Moms Group, which has more than 70,000 members, on April 7, 2019, and again on May 12, 2019. Each method explicitly explained the intention for only staff anesthesiologists identifying as female to take one time.

The survey was closed on May 20, 2019.

Data collected included demographics based on the United States (US) census questions when able, workplace policies and practices, perceived workplace gender disparities, and burnout assessment with validated questions as able. Multiple choice, true/false, and a 5-point Likert scale, where 0 = strongly disagree and 5 = strongly agree, were utilized for the questions.

The assessment of burnout was based on the question, “Overall, based on your definition of burnout, how would you rate your level of burnout?”[3] Responses were scored on a five-category ordinal scale where 1 = “I enjoy my work. I have no symptoms of burnout;” 2 = “Occasionally I am under stress and I don't always have as much energy as I once did, but don't feel burned out;” 3 = “I am definitely burning out and have one or more symptoms of burnout, such as physical and emotional exhaustion;” 4 = “The symptoms of burnout that I'm experiencing won't go away. I think about frustration at work a lot;” 5 = “I feel completely burned out and often wonder if I can go on. I am at the point where I may need some changes or may need to seek some sort of help.” This item was dichotomized as ≤2 (no symptoms of burnout) versus ≥3 (burnout).

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables were summarized using frequencies and percentages. Associations between categorical variables were tested using Chi-square test. Likert scale items were treated as continuous variables. T-tests were utilized to examine differences between those who reported burnout and those who did not. The level of significance was set at 0.05. All statistical analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4 (Copyright (c) 2002–2012 by SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

RESULTS

A total of 502 survey responses were received: 224 from email invitation, 80 from Twitter feed, and 177 from Physicians Moms Group [Table 2]. The majority of participants had been staff anesthesiologists for ≤10 years (67%). All areas of the US were represented with 3% representation from outside the US.

Table 2.

Demographics of survey participants (n=502)*

| Question | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Receipt of survey | |

| Email invitation | 224 (47) |

| 80 (16) | |

| Physician Moms Group on Facebook | 177 (37) |

| Number of years as staff anesthesiologist | |

| <5 | 167 (34) |

| 5-10 | 160 (33) |

| 11-20 | 87 (18) |

| >20 | 75 (15) |

| Relationship status | |

| Married/living with partner | 421 (88) |

| Single/never married | 27 (6) |

| Divorced/separated/widowed | 31 (6) |

| My place of work is | |

| Northeastern US | 138 (28) |

| Midwest US | 112 (23) |

| Western US | 102 (21) |

| Southeastern US | 76 (16) |

| Southwest US | 46 (9) |

| Outside of US | 16 (3) |

| During a typical week, I am physically in the hospital (h) | |

| <40 | 88 (18) |

| 40-60 | 354 (72) |

| 61-80 | 42 (9) |

| >80 | 5 (1) |

| Maternity leave at my hospital entails | |

| No paid time off; must use sick leave/vacation days | 167 (35%) |

| Paid time off <4 weeks | 26 (5) |

| Paid time off 4-8 weeks | 125 (26) |

| Paid time off >8 weeks | 56 (12) |

| Case-by-case basis; no formal policy | 9 (2) |

| Don’t know | 95 (20) |

*Totals don’t add up to 502 as not every question was answered by all participants

Overall, 66% of women cited that they were satisfied with their job choice and could not see themselves in another area of area of medicine or another career. The majority of respondents had completed further training following anesthesiology residency (68%) with pediatrics being the most common subspecialty training. Most participants were married or living with a partner (88%), had children (83%), were full time employees (82%), and had duties that involved home or pager call (74%). Most women were physically in the hospital between 40 and 60 h/week (90%).

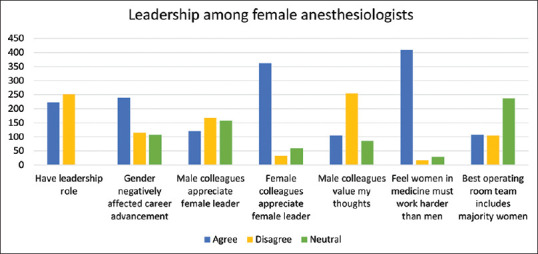

Nearly half of the respondents identified as having leadership responsibilities at the departmental or hospital level, such as schedule making or division or department chief (47%) [Figure 1]. However, 52% felt that being female negatively affected career advancement. Seventy-eight percent of respondents endorsed that they appreciate having females in leadership positions. In contrast, only 26% felt that men appreciated female leaders. Overwhelmingly, participants felt that women in medicine need to work harder than men in medicine to achieve similar goals (90%).

Figure 1.

Leadership characteristics and outcome variables of survey participants (n = 502)

Many respondents reported being responsible for the majority of the household duties (60%). Limitations of practice due to work-induced stress and home-induced stress were realized among 38% and 42%, respectively. Work-life balance was less than ideal for 45%, ideal for 33% and 23% were neutral as to their work-life balance [Figure 2]. Exercising weekly was attained by 36%. More than half (55%) of the participants had experienced sexual harassment by a work colleague in the form of unwanted touches or sexual comments/texts at some point in their medical training or career.

Figure 2.

Work-life characteristics and outcome variables of survey participants (n = 502)

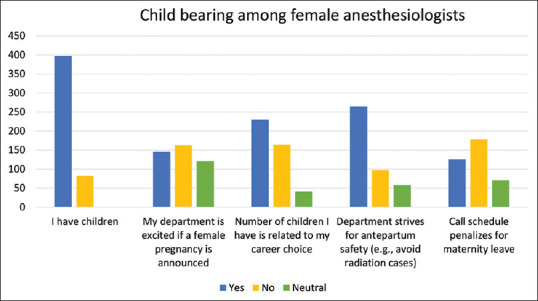

Half of the respondents (51%) felt that the number of children they had, or did not have, was due in part to career choice [Figure 3]. While pregnant, most departments strived to ensure antepartum safety such as avoidance of radiation exposure (58%). Over a third of respondents work in institutions that do not provide any form of maternity leave beyond the use of sick and/or vacation days to receive paid time off following the birth of a child (35%). Lactation spaces were suitable to 33%, unsuitable to 35%, and neutral or unknown to 32%. Many women identified that breastfeeding options were limited by lack of time, space, and other inconveniences (26% agreed, while 36% were neutral).

Figure 3.

Child bearing characteristics and outcome variables of survey participants (n = 502)

Some degree of burnout was experienced by 43% of respondents and was associated with work-life balance not being ideal (P < 0.0001), gender negatively affecting career advancement (P < 0.0001), experiencing sexual harassment at work (P = 0.002), feeling the need to work harder than men (P = 0.0033), responsible for majority of household duties (P = 0.0074), lack of weekly exercise (P = 0.0135), and unsuitable lactation provisions at work (P = 0.0007) [Table 3].

Table 3.

Work and personal characteristics associated with burnout

| Associations with burnout | No burnout | Burnout | P | DF | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Work-life balance ideal | 3.32 (1) | 2.22 (0.9) | <0.0001 | 449 | 0.93-1.27 |

| Believe gender has negatively affected career advancement | 3.21 (1.1) | 3.63 (1.1) | <0.0001 | 436 | −0.62-0.22 |

| Experienced sexual harassment at work | 3.05 (1.4) | 3.48 (1.4) | 0.002 | 422 | −0.69-0.16 |

| Feel women in medicine need to work harder than men | 4.2 (0.8) | 4.41 (0.8) | 0.0033 | 428 | −0.36-0.07 |

| Responsible for majority of household duties | 3.46 (1.2) | 3.76 (1.2) | 0.0074 | 428 | −0.52-0.08 |

| Participate in weekly physical exercise | 2.86 (1.4) | 2.43 (1.4) | 0.0012 | 427 | 0.17-0.69 |

| Call schedule penalizes women for maternity leave | 2.68 (1.2) | 3.05 (1.3) | 0.004 | 351 | −0.63-0.12 |

| Department ensures ease with lactation needs | 3.03 (1.2) | 2.61 (1.25) | 0.0007 | 361 | 0.18-0.67 |

Likert scale options ranged from 0=Strongly disagree to 5=Strongly agree. All data are reported as mean (SD). DF=Degrees of freedom, SD=Standard deviation, CI=Confidence interval

The only variable associated with women who had children was the number of children they had or did not have was related to career choice (P = 0.0006). Notably, having children was not associated with burnout (P = 0.75).

DISCUSSION

This survey study brings to light many fundamental issues encountered by women in anesthesiology. The question that prompted by far the most agreement among participants found that an overwhelming 90% felt that women in medicine need to work harder than men in medicine to achieve similar goals. This was exemplified by the finding that more than half of the respondents identified that male colleagues do not react to their vocalized thoughts concerning medical practice similarly as they would react to a male vocalizing identical thoughts. Despite the perceived need to work harder to achieve their goals, most female staff anesthesiologists were satisfied with their job choice and could not see themselves in another area of medicine or career.

Leadership

Our study identified that 47% of the women anesthesiologists surveyed in this study had leadership roles within their department or hospital [Figure 1]. This is in context with 51% of survey respondents perceiving that being female negatively affected career advancement. This sentiment is supported by observations found in this study. For example, 68% of respondents in this study completed postanesthesiology residency subspecialty training, 82% worked full time, 66% had more than 5 years of staff anesthesiology experience, and 78% cited that they value female leadership. Such characteristics would seem favorable for success in leadership roles. However, less than half of the respondents had leadership positions.

The current findings resonate with the “pipeline theory” referring to the fact that 34% of anesthesia residents are women, 37% of full time anesthesia faculty, 18% of full professors, and 11.5% of anesthesiology department chairs are women.[4,5] Surprisingly, in 114 years since inception of the American Society of Anesthesiologists began, only four women have risen to president.

Burnout

Understanding factors associated with burnout may lead to prevention and early treatment allowing skilled anesthesiologists to remain in the workforce longer. In this study, a total of 43% of the female anesthesiologists surveyed were experiencing burnout with most citing symptoms of emotional and physical exhaustion.[3] Years as staff correlated with symptoms of burnout. Overall, only 9% of all respondents reported no symptoms of burnout.

Not surprisingly, burnout was associated with work-life balance not being ideal [Table 3] and with responsibility for the majority of household duties. Burnout was also associated with feelings that being a woman has negatively affected career advancement and that woman need to work harder than men to achieve the same career goals. Burnout was also associated to lack of weekly exercise and lack of lactation needs at work. In addition, women who had experienced sexual harassment at work had a higher rate of burnout.

Work-life balance

The majority of participants in this study were married or living with a partner, had children and worked full time [Figure 2]. Our study demonstrated that 82% of participants work ≥40 h/week in-hospital and 74% take additional home pager call. Despite this, 60% of respondents report being responsible for the majority of household duties. This is an important finding due to the relationship of household duties and resultant burnout found in the present study. Not surprisingly, the need to limit roles at work or to go part-time solely due to demands of home life was realized by 42% of respondents.

Child bearing

In our study, half of the respondents felt that the number of children they had, or did not have, was due in part to career choice [Figure 3]. While pregnant, our study demonstrated that many, but not all, departments strive to ensure antepartum safety with avoidance of assignments with radiation exposure (58%).

In the present study, 35% of respondents' institutions did not offer any form of paid maternity leave. Other institutions offered paid time off for maternity leave with the most common time allotment being 4–8 weeks (26%). Less than a third (28%) of respondents identified that the call schedule penalized females for taking maternity leave with “pay-it-forward” calls or call retribution.

Lactation

One-third of participants identified that lactation spaces were suitable, while 35% found lactation spaces to be unsuitable and 32% of respondents were neutral or uncertain of lactation accommodations. Only 26% of anesthesiologists identified that the reason that they chose to not breastfeed was due to lack of time, space, and other inconveniences associated with pumping at work. Finally, very few women chose to not breastfeed due to health concerns resulting from exposure to anesthetic gas or other work environment (2%).

Sexual harassment

Unfortunately, 55% of participants in the present study experienced sexual harassment by a work colleague in the form of unwanted touches or sexual comments or texts at some point in their medical training or career. These findings compare with a 2018 report from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM) estimating that 58% of women faculty and staff in all disciplines of academia experience sexual harassment.[6,7] Furthermore, most analyses find that women in medicine experience the highest rates of sexual harassment of the science, technology, engineering, mathematics fields.[8,9] NASEM recommends scientific disciplines attend to sexual harassment with at least the same level of attention and resources as devoted to research misconduct.

Limitations

Limitations of this study include innate flaws associated with survey studies. The social media aspect of survey implementation also provided limitations. While it was explicitly advised to only complete the survey once, repeat submissions were possible. With certainty, the response rate of returned surveys was less than the survey interactions potentially creating a bias for participants who feel strongly concerning gender issues in medicine.

CONCLUSIONS

Like most complex problems, the causes of gender inequality are multifactorial and the solutions will require complex, integrated strategies. In order to create a conducive culture for gender equity in anesthesiology, along with all fields of medicine, departments should strive for equal access to resources and opportunities, minimization of unconscious gender bias and enhancing work-life balance. Indeed, the promotion of gender equity will benefit anesthesiology departments by retaining high quality anesthesiologists whom feel dedicated to their workplace.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

We would to thank you to the physician champions at each institution: Anoushka Afonso, Mabel Chung, Carlee Clark, Kate M. Cohen, Germaine Cuff, Dawn Dillman, Julie Huffmeyer, Joanna Miller, Ed Nemergut, Mark Nunnally, Daryl Oakes, Meg Rosenblatt, Marion Sherman, Sasha Shillcutt, Vesna Todorovic, Emily Vail, Lisa Weavind, Chris Webb.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adesoye T, Mangurian C, Choo EK, Girgis C, Sabry-Elnaggar H, Linos E, et al. Perceived discrimination experienced by physician mothers and desired workplace changes: A cross-sectional survey. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177:1033–6. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.1394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Choo EK, Byington CL, Johnson NL, Jagsi R. From #MeToo to #TimesUp in health care: Can a culture of accountability end inequity and harassment? Lancet. 2019;393:499–502. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30251-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dolan ED, Mohr D, Lempa M, Joos S, Fihn SD, Nelson KM, et al. Using a single item to measure burnout in primary care staff: A psychometric evaluation. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30:582–7. doi: 10.1007/s11606-014-3112-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.American Medical Association. Physician Characteristics and Distribution in the U.S. [Last accessed on 2019 Jul 07]. Available from: http://www.aamc/org/members/gwims/statistics .

- 5.Miller J, Chuba E, Deiner S, DeMaria S, Jr, Katz D. Trends in authorship in anesthesiology journals. Anesth Analg. 2019;129:306–10. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000003949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Sexual Harassment of Women: Climate, Culture, and Consequences in Academic Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. [Last accessed on 2019 Jun 04]. Available from: https://www.nap.edu/catalog/24994/sexual-harassment-of-women-climate-culture-and-consequences-inacademic . [PubMed]

- 7.Fairchild AL, Holyfield LJ, Byington CL. National academies of sciences, engineering, and medicine report on sexual harassment: Making the case for fundamental institutional change. JAMA. 2018;320:873–4. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.10840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Swartout KM, Flack WF, Cook SL, Olson LN, Smith PH, White JW. Measuring campus sexual misconduct and its context: The Administrator-Researcher Campus Climate Consortium (ARC3) survey. Psychol Trauma. 2019;11:495–504. doi: 10.1037/tra0000395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Westring A, McDonald JM, Carr P, Grisso JA. An integrated framework for gender equity in academic medicine. Acad Med. 2016;91:1041–4. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]