Abstract

Hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy is a type of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) that involves the left ventricular outflow tract obstruction. Most important parameters are preload, afterload, and ventricular contractility that are prone to fluctuations in HOCM patients in the perioperative period due to the surgical procedure, anesthetic agents and changes in intravascular volume. These lead to increased chances of arrhythmias and myocardial ischemia and can pose significant morbidity and mortality in HCM patients perioperatively. Here, we report three challenging cases of HCM with comorbidities who underwent successful operative management of lower limb fractures using regional nerve blocks. Although general anaesthesia is usually preferred in cases of HCM, this was not the preferred choice in these cases due to the asthmatic status, extremes of age, and also associated comorbidities such as chronic kidney disease Stage IV on maintenance hemodialysis. We selected Ultrasonography and peripheral nerve stimulator (PNS) guided regional nerve blocks including lumbar plexus and parasacral approach of sciatic nerve block in the first two patients and fascia iliaca compartment block with parasacral sciatic nerve block in the third case to successfully manage the patients perioperatively. Postoperative pain management was satisfactory. All the patients were discharged in a hemodynamically stable condition with advice for follow-up.

Keywords: Bifascicular block, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, orthopedic surgery, regional nerve blockade

INTRODUCTION

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) is defined as abnormal thickening of the myocardium manifested by hypertrophy of left ventricle (LV), or right ventricle (RV) without any apparent cardiac or systemic cause. HCM is also characterized by asymmetric hypertrophy of the interventricular septum. Hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy is a type of HCM that involves LV outflow tract (LVOT) obstruction.[1,2]

The increased pressure gradient across the LVOT in patients with HOCM can lead to circulatory collapse due to systolic anterior motion of the mitral valve and mitral regurgitation (MR).[3] Most important parameters are preload, afterload and ventricular contractility that are prone to fluctuations in HOCM patients in the perioperative period due to the surgical procedure, anesthetic agents and changes in intravascular volume.[4] These circulatory changes may increase the pressure gradient across LVOT.[3,5] These lead to increased chances of arrhythmias and myocardial ischemia and can pose significant morbidity and mortality in HCM patients perioperatively.[6]

With an incidence of 0.2%, HCM is not only the most common genetic disease of the heart but also is a frequent cause of sudden cardiac death in young adults and athletes.[7] The inheritance pattern of HCM is autosomal dominant. HCM is characterized by a mutation in one of the genes encoding for myocardial sarcomere proteins, which leads to an abnormal growth pattern of the myocyte.[8,9]

The first report of HCM is by Brock and Teare in 1957 and 1958 who described the condition respectively as subaortic stenosis and asymmetrical septal hypertrophy (ASH).[10,11] Although there has been change in nomenclature down the years, the term HCM is now used to signify LV hypertrophy without a dilated ventricular chamber irrespective of a cardiac or systemic disease causing the hypertrophy.[10,11]

HCM cases are considered anesthetically challenging owing to the chances of worsening of the outflow tract obstruction due to decrease in the preload or afterload or increase in myocardial contractility due to the sympathetic stimulation which is a common occurrence during anesthesia and surgery. In addition, the risk of anesthesia and surgery gets manifold due to the higher incidence of ischemic heart disease in patients with HCM.[12]

Here, we report three challenging cases of HCM with comorbidities who underwent successful operative management of lower limb fractures using peripheral nerve blocks.

CASE SUMMARY 1

Our first patient, a 49-year-old male patient, presented to the Emergency Department of a 600 bed Multi-specialty Teaching Hospital in Bihar, India, with a 1 day old fracture right patella and plateau fracture right tibia following a bike accident. He was refused from a Government Medical College and two very reputed private hospitals.

He was being planned for Open Reduction and Internal Fixation of right Tibia and tension band wiring of right patella. He was referred for pre-anesthetic assessment. He was a known patient of Asthma and was on regular medications with Inhalers and Steroids and also gave history of dyspnea at rest.

In the pre-anesthetic assessment clinic, he was found to have dyspnea at rest and on examination, blood pressure was 150/80 mm Hg, pulse 62 b.min− 1 (regular); chest examination revealed bilaterally equal vesicular breath sounds without any creps or rhonchi; CVS examination revealed S1, S2 normal, no murmurs. He did not have anemia, cyanosis, jaundice, clubbing and edema. Neck veins were not engorged. The examination of other systems did not reveal any abnormality.

His height was 168 cm, weight was 100 kg and his body mass index (BMI) was calculated as 35.1.

He was advised the routinely recommended preoperative investigations such as electrocardiogram (ECG), echocardiography, chest X-ray (PA view), routine blood tests like Complete hemogram, Bleeding Time, Clotting Time, Prothrombin Time, international normalized ration as a part of coagulation profile, serum sodium, serum potassium, and serology. The blood reports were all within normal limits. He furnished a pulmonary function test report (PFT) dated a month back showing moderate obstructive airway disease. The PFT was done following acute exacerbation of his asthmatic attack for which he was hospitalized in a private hospital for 2 days and treated with Intravenous (i.v.) antibiotics and nebulizers and discharged with Oral steroids and Inhalers.

Chest X-ray revealed prominent bronchovascular markings and enlarged cardio-thoracic (CT) ratio.

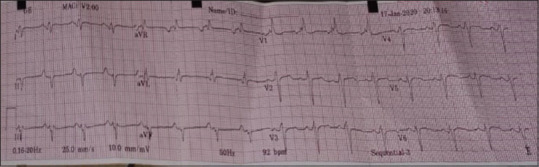

ECG revealed bifascicular block and he gave a history of one episode of syncope [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Electrocardiography strip showing bifascicular heart block

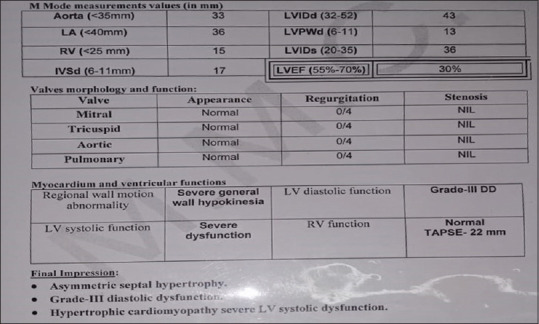

Echocardiography showed asymmetric septal hypertrophy, Grade III diastolic dysfunction, HCM with severe LV systolic dysfunction (EF 30%) [Figures 2 and 3].

Figure 2.

Echocardiography windows in the hypertrophic cardiomyopathy patient (case summary 1)

Figure 3.

Echocardiography report in the hypertrophic cardiomyopathy patient (case summary 1)

He was referred to the cardiologist and pulmonologist for clearance before surgery. Cardiology and Pulmonology Clearance was given as a high risk for surgery. He was put on tablet S-Amlodipine 2.5 mg and tablet epleronone 25 mg by the cardiologist and nebulization with Ipratropium bromide thrice daily and budesonide twice daily by the Pulmonologist. Following discussions with the surgical team, the cardiologist and the pulmonologist, he was planned for the operation under regional anesthesia (peripheral nerve block) and high risk consent obtained.

As a part of preoperative management along with the advice as given by the cardiologist and the pulmonologist, he was kept nil by mouth for 6 h and given tablet pantoprazole 40 mg and tablet alprazolam 1 mg the previous night. In the morning of the operation he was given a single shot of Injection cefuroxime axetil 1.5 g i.v. after proper skin test as a part of the routine surgical antibiotic prophylaxis as recommended in the hospital antibiotic policy, injection ondansetron 4 mg i.v. and injection pantoprazole 40 mg intravenously.

Provision for temporary pace maker was kept ready as standby in view of the ECG findings of bifascicular heart block and history of syncope.

Regional nerve blockade was achieved with 20 mL of 0.75% ropivacaine mixed with 40 mL Normal saline administered by USG-guided lumbar plexus block and parasacral approach sciatic nerve block (Mansoor approach) and administering 30 mL each in the two blocks after visualization with USG and confirming with peripheral nerve stimulation at twitch confirmed between 0.50 and 0.75 mAmp.

The surgery planned was done in tourniquet with only 50 mL of blood loss and completed within 2 h from skin to skin. Intraoperative monitoring of vitals was done every 5 min and systolic blood pressure/diastolic blood pressure was maintained at 120/80–140/80 mm of Hg; Heart rate maintained between 55 and 65 b.min−1, SO299% with 2 L.min−1O2. 250 mL of balanced salt solution was infused over 2 h and central venous pressure was maintained at 7–8 mm Hg. The patient was also administered injection midazolam 1 mg slow i.v. intraoperatively to alleviate anxiety.

After the operation, the patient was shifted to the critical care unit for a night of observation as was planned. The fluid was omitted to avoid volume overload and patient started on normal diet after half an hour. Oral anticoagulant, tablet apixaban 10 mg once a day was started after 12 h of surgery. He was shifted out of the critical care the next morning. The postoperative period was uneventful.

Postoperatively, pain was managed with oral tablet paracetamol 1 g four times daily and oral tapentadol 100 mg thrice daily after food for 3 days which was started 12 h after the surgery when the effect of the regional nerve block waned off. The patient was completely pain free (pain score was “0” in the Wong-Baker visual analog pain scale of 0–10) all throughout the postoperative period. He was discharged on POD 4 with advise for follow-up with the cardiologist, pulmonologist, and orthopedic surgeon after 1 week.

CASE SUMMARY 2

Our second case was an 80-year-old male patient who presented with a 2 days old fracture neck left femur to the orthopaedics out-patient department of a 600 bed Multi-Specialty Teaching Hospital in Bihar, India following a domestic fall. He was a known case of HOCM for the last 20 years.

He was being planned for hemiarthroplasty left hip and referred for preanaesthetic Assessment to the clinic.

Echocardiography as a part of preoperative management revealed Asymmetric septal hypertrophy, Grade II diastolic dysfunction, Grade 3 MR, HCM with LVOT pressure gradient of 80 mm Hg and LV systolic dysfunction (EF 42%). He was a known hypertensive and diabetic. General examination was within normal limits except mild pallor. Blood pressure was 160/90 mm Hg on oral Diltiazem 60 mg once daily. Pulse rate of 68 b.min−1 (regular). Preoperative investigations were all normal except Hb% of 9.2 gm%, Fasting Blood Glucose of 140 mg.dL−1 and Post Prandial Blood Glucose of 200 mg.dL−1. He was on oral citagliptine 100 mg once daily regularly as per the history given by him and his HbA1c was 8.1.

He was an average built individual with BMI of 25.2.

Preoperatively, he was referred to the cardiologist and endocrinologist and operative clearance obtained.

Modular bi-polar hemiarthroplasty left hip was planned with high risk consent. He was optimised preoperatively as advised by the cardiologist and endocrinologist as per usual protocol for a diabetic patient.

In-view of his low Hb%, 1 unit of cross-matched packed red blood cell (PRBC) was kept reserved. To alleviate anxiety, oral alprazolam 0.25 mg was given the night before the operation.

Peripheral nerve blockade was achieved with 30 mL of 0.25% ropivacaine in lumbar plexus block with peripheral nerve stimulation and 30 mL 0.2% ropivacaine at parasacral sciatic nerve block (Mansoor approach).

Intraoperatively the patient remained hemodynamically stable. Total estimated blood loss was 600 mL. Considering the age and the clinical profile of the patient, he was kept under planned observation in the Critical care unit for a day. He was shifted to the general bed on POD 1. Hb% on POD 1 was 8.5 gm% and he received 1 unit B Positive PRBC on POD 1 following which his Hb% became 9.4 gm%. He was given oral apixaban 10 mg once daily from POD 1. After the effect of the peripheral nerve block reduced after 12 h, his postoperative pain management was done with i.v. injection Tramadol hydrochloride 75 mg thrice daily for 1 day followed by oral Tapentadol 50 mg thrice daily for 2 more days. Pain score was between 0 and 1 in visual analogue scale of 0–10 all throughout the postoperative period. He was discharged in a hemodynamically stable condition on POD 5 with advice for follow up.

CASE SUMMARY 3

Our third case was a 72-year-old female patient who presented to the Emergency Department of a 600 bed Multi-Specialty Teaching Hospital in Bihar, India with history of a 4 days old bimalleolar fracture right lower limb following a road traffic accident. She was a known case of chronic kidney disease (CKD) Stage IV on thrice weekly maintenance hemodialysis (MHD) regime. She was a diagnosed case of HOCM.

She underwent pre-anaesthetic assessment. Her creatinine report done 2 days back was 5.4 mg.dL−1. She was having respiratory distress and features of volume overload. She complained of palpitations. Her blood pressure was 160/90 mmHg and pulse rate of 100 b.min−1 (irregular) and she was advised heparin free MHD as per protocol urgently. Routine preoperative investigations were within normal limits except a low Hb% of 7.5 gm%. She was a known diabetic with HbA1c 9.5 and FBS of 220 mg.dL−1 and PPBS of 340 mg.dL−1.

ECG revealed Atrial fibrillation with heart rate of 90–100/min. Echocardiography revealed apical and septal hypokinesia, assymetric septal hypertrophy, LVOT 45 mm Hg, LV Ejection Fraction of 48%. There was no vegetation of clot in the chambers.

Preoperatively, she was referred to the cardiologist and endocrinologist. She was put on oral bisoprolol 5 mg once daily. She received 2 units of cross-matched O positive PRBC preoperatively following which her Hb% on the morning of OT was 9.0 gm%. To alleviate anxiety, Oral Alprazolam 0.25 mg was given the night before the operation.

Other preoperative preparations were as per usual protocol.

She underwent ORIF with fixation of right bimalleolar ankle fracture with tourniquet application with fascia iliaca compartment block with parasacral sciatic nerve block (Mansoor approach). 15 mL 0.25% ropivacaine was used in USG guided adductor canal saphenous nerve block and 35 mL 0.2% ropivacaine in administering the sciatic nerve block. USG guidance and peripheral nerve stimulation was used in both the procedures. The total duration of surgery from skin to skin was 1½ h. The total blood loss was approximately 80 mL. Hemodynamic parameters were all maintained during the operation.

The patient was kept under planned observation in the Critical care unit owing to her comorbidities. She was started on oral Apixaban 5 mg from POD 1. She was shifted to general bed and put on MHD from POD 2. Postoperatively her pain was well controlled with only oral paracetamol 1 g thrice daily on POD 1. She required supplementation with i.v. injection tramadol 50 mg once on POD 1. Pain score subsequently was between 0 and 1 in visual analogue scale of 0–10 with Oral Paracetamol on SOS basis which was required once on POD 2 only and none thereafter. She was discharged with advise for follow up on the POD 4.

DISCUSSION

HCM not only affects all ages but has a unique and complicated pathophysiology which includes dynamic obstruction to LV outflow, diastolic dysfunction, impaired coronary vasodilator reserve, myocardial ischemia, and supraventricular or ventricular tachyarrhythmias.[13]

HCM can be classified as hypertrophic nonobstructive cardiomyopathy, apical HCM and mid-ventricular obstructive HCM. Additionally, patients who satisfy any of the following criteria are diagnosed as having a severe disease: Moderate to severe restriction of physical activity (NYHA Class III/IV), a history of sustained ventricular tachycardia or ventricular fibrillation and a history of hospitalisation for heart failure or arrhythmia treatment.[14,15]

Our patient in Case Summary 1 was NYHA Class IV having LVOT HCM, ASH and therefore, he was diagnosed as severe HOCM. The other two patients were also diagnosed cases of HOCM as mentioned above and were high risk patients due to extremes of age and the comorbidities. Thus, the challenges in all the three cases discussed were multiple.

Beta blockers and calcium channel blockers are the preferred drugs to treat HCM. Beta blockers are beneficial due to the decrease in heart rate and prolongation of diastole as a consequence, increase in passive ventricular filling and decrease in myocardial oxygen requirement.[16] Ca2+ channel blockers like Verapamil and Diltiazem are also beneficial due to their ventricular relaxation and filling.[17] But in our first patient, we could not administer beta blockers due to the Bifascicular heart block.

Preloading with atleast 500 mL i.v. fluid is recommended in cases of HOCM. This helps to maintain the stroke volume and at the same time minimize adverse events of positive pressure ventilation. But, it could not be done in the first and second case in view of the very low ejection fraction and in the third case due to the challenge of volume overload in a CKD Stage IV patient on MHD.

Though general anesthesia is usually preferred in cases of HCM, this was not the preferred choice in these cases due to the asthmatic status, extremes of age and also associated comorbidities like CKD Stage IV on MHD in the patients.

In a patient of HCM posted for noncardiac surgery, the goal of anesthetic management is to prevent occurrence of LVOT obstruction, arrhythmias and diastolic dysfunction through the following strategies:[18,19]

Maintenance of sinus rhythm

Reduction of sympathetic activity

Maintenance of LV filling

Maintenance of systemic vascular resistance.

The concerns for our patients were the presence of HCM with LVOT, Bifascicular Heart Block with history of Syncope and Asthma; extremes of age, comorbidities like CKD Stage IV on MHD and atrial fibrillation.

Use of anxiolytics as premedication and intraoperatively has an important role in reducing sympathetic activity and therefore reducing cardiac workload. Invasive monitoring for BP and Central Venous Pressure (CVP) need to be done in HCM patients undergoing noncardiac surgery.

Attempts to prevent tachycardia, hypotension, sympathetic stimulation, increased myocardial contractility and decrease in preload and afterload are of paramount importance in such patients.[19]

Although general or spinal anaesthesia is commonly used for all the three surgical procedures, both the methods may cause severe fluctuation of blood pressure mainly hypotension. Moreover, as the patients had cardiac conduction and rhythm abnormalities there were chances of sever bradyarrhythmia as well as tachyarrhythmia. As the patients had COPD, were at extremes of age and other comorbidities general anesthesia was not the preferred option.

In our first case, due to severely decreased ejection fraction (30%), bifascicular heart block and bronchial asthma, betablocker and Ca2+ channel blockers were contraindicated. Even, we could not nebulise the patient with beta-agonists as those can cause tachycardia.

Considering the clinical profile of our cases, we selected combined lumbar plexus block and parasacral sciatic nerve block in the first two cases and fascia iliaca compartment block with parasacral sciatic nerve block in the third case as discussed above to reduce the effect of anaesthesia on systemic vascular resistance and heart rate. However, even partially successful regional anaesthesia can stimulate sympathetic nervous system activity and lead to increased heart rate which would elevate the risk of increased cardiac contractility which in turn would increase the pressure gradient across LVOT and cause hemodynamic decompensation in HCM patients.[20,21] So, precision was achieved with the use of ultrasonography and Peripheral nerve stimulator (PNS) towards a successful peripheral nerve block.

There are very few case reports on the use of lumbar plexus and parasacral approach of sciatic nerve block and fascia iliaca compartment block with parasacral sciatic nerve block in patients with HOCM which makes these cases unique. We measured continuous arterial pressure and CVP through right internal jugular vein (RIJV) cannulation done aseptically in all the three cases.

Post-operative pain in HCM patients can increase sympathetic nervous system (SNS) activation which could increase pressure gradient across the LVOT. Using Ropivacaine in nerve blocks, provided long lasting analgesia which was supplemented after 12 h (when the effect of nerve block waned) by i.v. and oral pain killers as mentioned above.

CONCLUSION

We selected ultrasonography and PNS guided peripheral nerve blocks including lumbar plexus and parasacral sciatic nerve block in the first two patients and fascia iliaca compartment block with parasacral sciatic nerve block in the third case to successfully manage all the patients of HCM peri-operatively. The patient's hemodynamic parameters were stable. The postoperative pain management with Paracetamol, Tramadol hydrochloride and Tapentadol in optimum doses was also excellent. None of the three patients experienced any complication in the perioperative and postoperative period. The patients recovered and were discharged with advice for follow up as usual.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patients have given their consent for their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Maron BJ, Ommen SR, Semsarian C, Spirito P, Olivotto I, Maron MS. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: Present and future, with translation into contemporary cardiovascular medicine. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64:83–99. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maron BJ, Maron MS. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Lancet. 2013;381:242–55. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60397-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maron BJ, Maron MS, Semsarian C. Genetics of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy after 20 years: Clinical perspectives. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60:705–15. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.02.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Karuppiah S, Syed A, Naguib A, Tobias J. Perioperative management of two pediatric patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy undergoing minimally invasive surgical procedures. J Med Cas. 2016;7:115–9. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gajewski M, Hillel Z. Anesthesia management of patients with hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2012;54:503–11. doi: 10.1016/j.pcad.2012.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sahoo RK, Dash SK, Raut PS, Badole UR, Upasani CB. Perioperative anesthetic management of patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy for noncardiac surgery: A case series. Ann Card Anaesth. 2010;13:253–6. doi: 10.4103/0971-9784.69049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maron BJ, Gardin JM, Flack JM, Gidding SS, Kurosaki TT, Bild DE. Prevalence of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in a general population of young adults. Echocardiographic analysis of 4111 subjects in the CARDIA Study. Coronary Artery Risk Development in (Young) Adults. Circulation. 1995;92:785–9. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.92.4.785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ho CY. Genetics and clinical destiny: Improving care in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2010;122:2430–40. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.978924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Richard P, Charron P, Carrier L, Ledeuil C, Cheav T, Pichereau C, Benaiche A, et al. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: Distribution of disease genes, spectrum of mutations, and implications for a molecular diagnosis strategy. Circulation. 2003;107:2227–32. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000066323.15244.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Teare D. Asymmetrical hypertrophy of the heart in young adults. Br Heart J. 1958;20:1–8. doi: 10.1136/hrt.20.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brock R. Functional obstruction of the left ventricle; acquired aortic subvalvar stenosis. Guys Hosp Rep. 1957;106:221–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Poliac LC, Barron ME, Maron BJ. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Anesthesiology. 2006;104:183–92. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200601000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sivanandam A, Ananthasubramaniam K. Midventricular hypertrophic cardiomyopathy with apical aneurysm: Potential for underdiagnosis and value of multimodality imaging. case rep Cardiol. 2016;2016:9717948. doi: 10.1155/2016/9717948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Paluszkiewicz J, Krasinska B, Milting H, Gummert J, Pyda M. Apical hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: Diagnosis, medical and surgical treatment. Kardiochir Torakochirurgia Pol. 2018;15:246–53. doi: 10.5114/kitp.2018.80922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maron BJ, Seidman CE, Ackerman MJ, Towbin JA, Maron MS, Ommen SR, Nishimura RA, et al. How should hypertrophic cardiomyopathy be classified? What's in a name? Dilemmas in nomenclature characterizing hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and left ventricular hypertrophy. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2009;2:81–5. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.108.788703. discussion 86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cherian G, Brocking IF, Shah PM, Oakley CM, Goodwin JF. Beta adrenergic blockade in hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy. Am J Cardiol. 1966;18:481–8. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.5492.895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Spoladore R, Maron MS, D'Amato R, Camici PG, Olivotto I. Pharmacological treatment options for hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: High time for evidence. Eur Heart J. 2012;33:1724–33. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Davies MR, Cousins J. Cardiomyopathy and anaesthesia. Continuing Educ Anaesth Critical Care Pain. 2009;9:189–93. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jennifer K. Carroll, Eithne Cullinan, Linda Clarke, Niall F. Davis. The role of anxiolytic premedication in reducing preoperative anxiety. Br J Nurs. 2012;21:479–83. doi: 10.12968/bjon.2012.21.8.479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nama RK, Parikh GP, Patel HR. Anesthetic management of a patient with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy with atrial flutter posted for percutaneous nephrolithotomy. Anesth Essays Res. 2015;9:284–6. doi: 10.4103/0259-1162.156372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sinclair HC, Russhard P, Critoph CH, Steadman CD. Routine orthostatic LVOT gradient assessment in patients with basal septal hypertrophy and LVOT flow acceleration at rest: Please stand up. Echo Res Pract. 2019;6:K1–K6. doi: 10.1530/ERP-18-0072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]