Abstract

Bereaved families that collectively make meaning of their grief experiences often function better than those that do not, yet most social work bereavement interventions target individuals rather than family units. In this article, authors describe an innovative social work intervention that employs Digital Storytelling. This is a narrative technique that combines photography, music, and spoken word to help families bereaved by child death make meaning of their loss and envision a future without their deceased child.

Keywords: Digital Storytelling, Meaning-making, Child Death, Bereavement, Family

The death of a child is widely accepted as one of the most profoundly devastating experiences a family will endure (Endo, Yonemoto, & Yamada, 2015). Going against the grain of biology, child death violates the order of natural living. Society generally accepts that parents are not supposed to outlive their children and that siblings ought to be able to grow old with one another (Keesee, Currier, & Neimeyer, 2008; Wendy G Lichtenthal, Currier, Neimeyer, & Keesee, 2010).

When a child dies, family members’ grief responses are inextricably linked to those of their surviving relatives (Nadeau, 2001). When bereaved families come together to make sense of their loss and plan for a future together, individual family members are often better able to cope and live productive and satisfying lives (Nadeau, 2001). Conversely, when families refrain from communication about grief, family members may struggle to understand themselves and one another and may feel a heightened sense of distress facing an uncertain, sad, or frightening future (Steffen & Coyle, 2017).

This article describes the potential of Digital Storytelling as a bereavement intervention for social workers serving families who have experienced the death of a child. Authors underscore the importance of bereaved families’ search for meaning in child death and the therapeutic potential of Digital Storytelling in this regard. General instruction for how to implement Digital Storytelling is provided.

Meaning-making and Family Bereavement after Child Loss: Healing through Story

In his book, Man’s Search for Meaning, Frankl (1962) powerfully articulates this quest in saying, “In some ways suffering ceases to be suffering at the moment it finds a meaning…”. This search for meaning, particularly after death, has been implicated as an integral component of the grieving process (Gillies & Neimeyer, 2006; Wendy G. Lichtenthal, Neimeyer, Currier, Roberts, & Jordan, 2013; Neimeyer, Baldwin, & Gillies, 2006). Over time, families develop a shared system of beliefs (i.e., global meanings) for understanding their world (Reiss, 1981). These shared global meanings represent a family’s assumptions, traditions, and rituals and are intrinsically part of the existence of the family unit. When a family experiences the death of a child, these core beliefs are often shattered not only for individual family members but also for the family unit as a whole. When families are able to come together to discuss and make sense of their loss and develop new assumptions, traditions, and rituals, family members may experience less distress (e.g., depression and anxiety) and may be better able to support and care for one another (Nadeau, 2001; Neimeyer et al., 2006)

Family storytelling and the search for meaning.

Storytelling has long been used as a supportive tool for people who have experienced adverse life events. It encourages them to process their feelings and emotions about an event through narratives (Bosticco & Thompson, 2005; Nadeau, 2001; Robinson & Hawpe, 1986; Sedney, Baker, & Gross, 1994). The narrative, re-authoring process of therapeutic storytelling (i.e., the reframing of adverse life experiences as a way to find new meaning) is especially important for bereaved families. When bereaved families engage in therapeutic storytelling as a way to re-author their family story in the wake of a loss, they work collaboratively in establishing new global meanings (Koenig Kellas & Trees, 2006; Nadeau, 2001). Discussing stories together contributes to the family’s ability to make sense of difficult experiences (e.g., child death) and enhances their ability to heal (Koenig Kellas & Trees, 2006).

Digital Storytelling.

Digital Storytelling is a multi-media storytelling process that combines photography, music, and spoken word as a way to capture one’s lived experiences and increase understanding of these experiences (De Vecchi, Kenny, Dickson-Swift, & Kidd, 2016; Lambert et al., 2003). Though Digital Storytelling has strong roots in education (Robin, 2008; Sadik, 2008; Wang & Zhan, 2010), community engagement (Briant, Halter, Marchello, Escareño, & Thompson, 2016; Rose, 2016; Wexler, Gubrium, Griffin, & DiFulvio, 2013), and participatory research (Gubrium, 2009; Jernigan, Salvatore, Styne, & Winkleby, 2011; Wexler et al., 2013), it has become increasingly popular among healthcare professionals, especially in pediatric palliative care settings (Akard et al., 2015; Akard et al., 2013; Foster, Dietrich, Friedman, Gordon, & Gilmer, 2012) and offers social workers an innovative approach to helping families heal after the death of a child. Documented benefits of Digital Storytelling include an improved sense of self, enhanced self-efficacy, and improved quality of life (Akard et al., 2015; Akard et al., 2013; Barnato et al., 2017; Foster et al., 2012).

Theoretical Foundation for Digital Storytelling as a Family Meaning-making Intervention

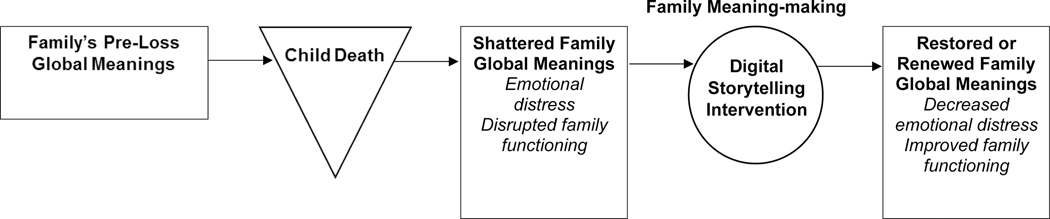

To inform the use of Digital Storytelling as a bereavement intervention for families that have experienced child death, authors adapted Gillies and Niemeyer’s (2006) constructivist, meaning-making model (Figure 1). This adapted model is consistent with the family systems understanding of meaning-making (Nadeau, 2001) in that it asserts that families establish a set of global beliefs that affects the way they exist and function in the world. When a family experiences a traumatic event, like child death, these global family beliefs are shattered, causing emotional distress and disrupting their ability to function as a family.

Figure 1.

Adapted Constructivist Meaning-making Model

This adapted model suggests that, when bereaved families engage in Digital Storytelling, they increase their ability to communicate their feelings about the death and their grief, which allows them to work collectively in establishing new global family meanings. When families are able to make meaning of the death experience, they are better able to function individually and as a family unit, and they experience less post-loss distress.

Implementing Digital Storytelling as a Social Work Intervention for Bereaved Families

Digital Storytelling is a highly flexible intervention approach that social workers can design in many different ways to best meet the needs of their clients; however, there are a few general elements. It is recommended that a trained Digital Storytelling facilitator (e.g., someone who has experience in the reflective Digital Storytelling process) implement Digital Storytelling sessions, workshops, or groups (Lambert, 2010; Stenhouse, Tait, Hardy, & Sumner, 2013). There are many online resources (e.g., StoryCenter, 2017) with additional information on training opportunities. Digital Storytelling participants are not generally required to have in-depth knowledge of storytelling processes or any previous experience using movie-making applications or software; however, participants should be willing to engage in the sessions, develop their stories in a movie-making software, and potentially share them with others.

Digital Storytelling is commonly facilitated in groups (e.g., Digital Storytelling workshops) that span a period of several days. When delivering Digital Storytelling as a family intervention, social workers may choose to work with one family at a time or may hold larger group sessions made up of multiple family units. Social workers should specify whether participants should work together to create one story as a family or whether each individual participant should tell a separate story. There are advantages and disadvantages to both approaches.

If families work together to create a single story, participants may be more easily able to focus on the family’s collective experience, and they may better understand how their individual experience is part of a larger whole. However, it may be challenging to ensure that all family members have a voice in the creation of the story, and family members may need support in reconciling conflicting versions of the same events. If family members create individual stories, it is much easier to ensure that everyone participates and is heard, but they may require more redirection to focus on how the loss affects the family as a distinct social system.

The core elements of a Digital Storytelling workshop (Lambert et al., 2003), adapted for inclusion in a clinical social work bereavement intervention, are provided below:

Introduction, ice breakers, and rapport building: This process allows the storytellers (i.e., the intervention participants) to become familiar with Digital Storytelling, the facilitator(s), as well as other members of the group (if delivering Digital Storytelling as a group intervention). To promote engagement, the social worker can facilitate ice breakers and other rapport-building activities before beginning the process of Digital Storytelling.

Story Circle or Storyboarding: This is the process during which storytellers map out and decide the overall purpose of the story they would like to share. Storyboards provide a visual blueprint of all the aspects of the story the storytellers wish to highlight. During this phase, storytellers consider various images and sounds they might want to include and identify what resources are needed to complete the final digital story. Paper or electronic storyboarding templates are useful in this phase of the digital storytelling process. This step provides storytellers with an opportunity to recall and discuss events surrounding their family member’s illness or accident and death. Storytellers reflect upon numerous narratives as ways to communicate what occurred. In doing so, they must organize and make sense of these events, a process some have cited as the most valuable aspect of Digital Storytelling. At this time, family members often learn from one another about events they had not previously had knowledge of, had forgotten, or had misunderstood or viewed differently. They may look over old photographs or toys together and reminisce, thinking about how things used to be. They may also begin to think about their future as a family, reaffirming or revising family values, goals, priorities, or plans. A sample storyboard template is provided in Figure 2.

Writing the script: Digital Storytelling scripts are first-person narratives that allow storytellers to capture their (or their family’s) own voice and style. The expectation is that participants’ stories represent their own personal meaning or insights regarding their experiences. If family members are working together to create one story, these meanings and insights reflect the experiences of all family members and the family as a whole. While these scripts are later audio-recorded, at this stage participants focus on getting their stories down on paper, optionally reading them aloud to other participants.

Organizing the project: Using the storyboard and video-editing software (e.g., iMovie and Windows Movie Maker are free and easy to use video-editing software packages), storytellers organize their project to prepare it for voiceovers and final editing. While this is a mostly technical step and can be done at home if storytellers have the necessary tools and skills, facilitators are encouraged to provide dedicated space and technical support for this process.

Voiceovers: This is the heart and soul of the digital story, as this process allows the story to be told in a way that no one other than the storytellers can. Voiceovers are digitally created files of the storyteller reading their final script. Storytellers can directly record themselves reading their script onto the computer, electronic tablet, or smartphone they will later use to make their digital story or they can record it onto a digital recorder and transfer the file later. It is not uncommon for participants to be reluctant to read their story aloud and, as such, social workers are obligated to meet participants where they are in their grieving process. However, many participants have commented on the power of this step. It is also not uncommon for participants to rehearse their story several times before recording it, gaining a sense of control over events that may have previously felt overwhelming. Some participants choose to include moments of crying, accepting feelings of sadness as a normal or even special part of the grieving process. Others express pride or satisfaction in being able to get through their story without becoming overpowered by their emotions, sometimes after numerous repeated attempts.

Final stages of video-editing: In this phase, storytellers are putting together the final pieces of their digital stories. They are using their storyboards as a guide and are putting together their images, music, and voiceovers in one final digital story. Completion of this phase requires access to a computer, electronic tablet, or smartphone with movie-making software installed (smartphones are discouraged for use with older adults or others who may struggle to read and interact with small screens); however, storytellers need not have an in-depth understanding of the technology. Storytellers can be trained to use basic features of most movie-making applications in 45–60 minutes, assuming the availability of ongoing technical support from facilitators. While this step was not designed with a therapeutic intent, several storytellers have commented on the value of learning something new and gaining an enhanced sense of self-efficacy in the midst of grief.

Story sharing and closing celebration: Storytellers share their finalized digital stories with one another and discuss their reactions and experiences as storytellers and as individuals hearing others’ stories. Typically this phase involves a celebration or a ritual that closes the storytelling experience.

Figure 2.

Sample Storyboard Template

In addition to these elements, social workers may design interventions with specific therapeutic processes in mind. Drawing strongly from the theoretical framework outlined in Figure 1, the authors structure Digital Storytelling as a meaning-making intervention. Rather than focusing primarily on memorializing the deceased child and his or her legacy, families examine their global beliefs prior to the child’s death and are invited to document and share the story of how those beliefs have changed over time and how their family has developed restored or renewed global beliefs following their loss and into the future.

It is also important to note that the authors conceptualize Digital Storytelling, delivered in this format, as a clinical social work intervention. Our work with each family is based on a thorough biopsychosocial and spiritual assessment in which there is a screening for indicators that an individual or family might be more appropriate for an alternate treatment (e.g., individuals who meet the criteria for clinical depression, families in which violence occurs). In addition to this screening, social workers use this assessment as an opportunity to explore the ways in which each family is coping well with the loss (however they define that) as well as ways they would like to change or grow. This assessment is ongoing throughout the intervention and informs how social workers can support each family in redefining new family global meanings (e.g., new values, traditions, and ways of interacting). To date, the authors’ primary method of evaluation of Digital Storytelling interventions has been qualitative. Participants of Digital Storytelling are asked if and how the intervention shaped their post-loss global meanings (e.g., “How, if at all, has this changed the way you think about your family?” and “How, if at all, has this affected your ability to make sense of or find benefit in your loss?”) and how they envision drawing on this experience in the future. Termination typically coincides with a sharing of the final version of participants’ stories and a ceremony acknowledging the strength required to create and share the stories in addition to honoring the final product. In the authors’ experience using Digital Storytelling as a bereavement intervention, a two week follow-up occurred, in which participants were asked if they shared their video with others (and, if so, how it went) and how these new meaning structures have affected their ability to function and cope with the loss. This follow-up also occurred at one-month post-sharing of their digital story.

An illustration.

The following example of a multi-family Digital Storytelling group (pseudonyms are used and potentially identifying details have been changed to ensure confidentiality) is provided as a springboard from which social workers can design Digital Storytelling interventions for their specific client population:

Gloria is a social worker affiliated with a healthcare system in a small Midwestern city. As part of a larger bereavement support program, she develops a Digital Storytelling group for families who have experienced the death of a child. She partners with the pediatric social workers in her healthcare system to identify potential participants, sending them information about the group via U.S. mail. Three families (5 adults, 6 children) respond, indicating an interest in learning more.

Gloria meets separately with each of the families before inviting them to take part in the group. During those meetings, conducts a comprehensive biopsychosocial and spiritual assessment, provides additional information about Digital Storytelling, and screens for any psychosocial issues that may affect the family’s ability to cope with the death and function cohesively as a family afterward (e.g., posttraumatic stress, interpersonal violence, etc.). After learning that all interested parents work dayshift hours, Gloria schedules the five group sessions for an upcoming weekend and the following Monday, Tuesday, and Wednesday evenings. Table 1 provides a detailed description of each session.

Table 1.

Digital Storytelling At-a-Glance

| Session Number | Digital Storytelling Session (2 hour sessions) |

|---|---|

| Individual Family Meetings (Prior to the First Group Session) | In this session, the social worker provides the storytellers (i.e., intervention participants) with basic psychoeducation about grief and loss and Digital Storytelling. The social worker facilitates rapport building and asks the storytellers to spend some time outlining their stories and discussing, together as a family, what they would like to focus their digital story on. The social worker ends the meeting with a closing activity. |

| Session 1 (Introducing the Narrative): Introduction to Digital Storytelling and Writing the Story Script | This session begins with an opening activity (continued rapport building). The social worker then guides the families through a process of writing their scripts. Each family shares their script, inviting members of other families and the social worker to respond. Prior to the end of the session, families are asked to digitally record their finalized scripts. The social worker ends the session with a closing activity. |

| Session 2 (Exploring thoughts and feelings about death and grief): Storyboarding Session | The session begins with an opening activity, followed by the storyboarding session. The social worker distributes storyboard templates to all the families and teaches the storytellers how to complete them, allowing sufficient time for families to finalize their storyboards before the end of the session. The social worker instructs families to collect images and memorable items to include in their digital stories and to bring them to the next group session. The social worker ends the session with a closing activity. |

| Session 3 (Continued exploration): Video-editing Session | This session begins with a brief opening activity. The social worker spends the remaining time working with families on building their digital stories in the video-editing software. The session ends with a closing activity. |

| Session 4 (Re-claiming control): Sharing the Digital Story | This session begins with a brief opening activity. The social worker invites families to share their digital stories. The social worker allows time for interaction and reflection. The social worker encourages families to share their digital story with someone outside of their group and to discuss that experience as a family. The session ends with a closing activity. |

| Session 5: De-briefing session | This session begins with a brief opening activity. The social worker guides the families in a discussion about their experiences with digital storytelling. The social worker asks families to discuss how participating in digital storytelling has affected their family. The social worker asks the family to discuss how they will use their digital story moving forward. The social worker ends the session with a closing ceremony, during which they provide each family with a DVD of their story. |

In this illustration, the Smith family experienced the death of Evan (age 6) who died after living with Leukemia for two years. Six months after their loss, the Smith family joined Gloria’s Digital Storytelling group. Both parents (Aimee and Jonathan) and their two children (Joanna, age 12 and Oliver, age 9) participated. The Smiths focused a portion of their digital story on their family traditions which, before Evan’s death, had included a yearly tradition of playing Monopoly on Christmas Eve. The Smiths took a picture of a game piece (the car) to include in their digital story. They discussed how they planned to continue their Christmas Eve Monopoly tradition in the future and agreed that no one would play the car game piece, which had been Evan’s favorite. By including the image of the car piece in their digital story, the Smiths illustrated how they had broadened their idea of togetherness to include Evan even after his death. During the final session, Gloria presented the Smiths with a DVD of their final digital story. The Smiths discussed their plan to share the DVD with Jonathan’s mom, who also participated in their Christmas Eve tradition, as a way to remain connected to Evan’s spirit and as an opportunity to discuss their feelings of grief and loss.

Ethical Considerations

It is important to gain the consent of all family members participating in Digital Storytelling and ensure that participation in this process is voluntary. A discussion about obtaining consent from individuals featured in the digital story itself and a plan for how storytellers will obtain this consent should be defined. Furthermore, the stories themselves are often so distinct that confidentiality cannot be guaranteed. Facilitators of Digital Storytelling should discuss with participants their plan for how they wish to use their stories beyond their final session and what it means to share their story in a public format, if this is what they indicated they would like to do. Finally, honoring and remembering someone who has died is an important component of the grieving process. However, it may be difficult to write about and share stories that capture intimate details of a family’s loss experience. Social workers facilitating Digital Storytelling interventions should allow sufficient time for debriefing both during and after the intervention and should make available information on additional or continued psychosocial support services for participants.

Conclusion

Digital Storytelling interventions provide families with an opportunity to communicate openly about their loss and grief and how it has affected the family unit. By focusing on making meaning of the loss, Digital Storytelling helps families reconstruct global beliefs and move forward as a family. While future research is needed to determine the efficacy of Digital Storytelling interventions in improving outcomes for grieving families, such approaches are highly consistent with social work’s perspective of the interconnectedness of human experience and its focus on enhancing family functioning.

Acknowledgments

Funding:

The authors received no financial support for the research and/or authorship of this article.

Author Bios:

Abigail J. Rolbiecki, PhD, MPH, MSW is a postdoctoral fellow in the Department of Family and Community Medicine at the University of Missouri, Columbia, Missouri, USA.

Karla Washington, PhD, LCSW is an assistant professor in the Department of Family and Community Medicine at the University of Missouri, Columbia, Missouri, USA.

Katina Bitsicas, MFA is an assistant teaching professor in the Reynolds School of Journalism at the University of Missouri, Columbia, Missouri, USA.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests:

The authors have no conflicts of interest with respect to the authorship and/or publication of this article.

References

- Akard TF, Dietrich MS, Friedman DL, Hinds PS, Given B, Wray S, & Gilmer MJ (2015). Digital storytelling: An innovative legacy‐making intervention for children with cancer. Pediatric Blood & Cancer, 62(4), 658–665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akard TF, Gilmer MJ, Friedman DL, Given B, Hendricks-Ferguson VL, & Hinds PS (2013). From qualitative work to intervention development in pediatric oncology palliative care research. Journal of Pediatric Oncology Nursing, 30(3), 153–160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnato AE, Schenker Y, Tiver G, Dew MA, Arnold RM, Nunez ER, & Reynolds CF (2017). Storytelling in the Early Bereavement Period to Reduce Emotional Distress Among Surrogates Involved in a Decision to Limit Life Support in the ICU: A Pilot Feasibility Trial. Critical Care Medicine, 45(1), 35–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosticco C, & Thompson TL (2005). Narratives and story telling in coping with grief and bereavement. OMEGA-Journal of Death and Dying, 51(1), 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Briant KJ, Halter A, Marchello N, Escareño M, & Thompson B. (2016). The Power of Digital Storytelling as a Culturally Relevant Health Promotion Tool. Health Promotion Practice, 1524839916658023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Vecchi N, Kenny A, Dickson-Swift V, & Kidd S. (2016). How digital storytelling is used in mental health: A scoping review. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 25(3), 183–193. doi: 10.1111/inm.12206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endo K, Yonemoto N, & Yamada M. (2015). Interventions for bereaved parents following a child’s death: A systematic review. Palliative Medicine, 29(7), 590–604. doi: 10.1177/0269216315576674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster TL, Dietrich MS, Friedman DL, Gordon JE, & Gilmer MJ (2012). National survey of children’s hospitals on legacy-making activities. Journal of palliative medicine, 15(5), 573–578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frankl VE (1962). Man’s Search for Meaning: An Introduction to Logotherapy: a Newly Revised and Enlarged Edition of from Death-camp to Existentialisme: Beacon press. [Google Scholar]

- Gillies J, & Neimeyer RA (2006). Loss, grief, and the search for significance: Toward a model of meaning reconstruction in bereavement. Journal of Constructivist Psychology, 19(1), 31–65. [Google Scholar]

- Gubrium A. (2009). Digital storytelling: An emergent method for health promotion research and practice. Health Promotion Practice, 10(2), 186–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jernigan VBB, Salvatore AL, Styne DM, & Winkleby M. (2011). Addressing food insecurity in a Native American reservation using community-based participatory research. Health education research, cyr089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keesee NJ, Currier JM, & Neimeyer RA (2008). Predictors of grief following the death of one’s child: The contribution of finding meaning. Journal of clinical psychology, 64(10), 1145–1163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenig Kellas J, & Trees AR (2006). Finding Meaning in Difficult Family Experiences: Sense-Making and Interaction Processes During Joint Family Storytelling. Journal of Family Communication, 6(1), 49–76. doi: 10.1207/s15327698jfc0601_4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert J. (2010). Digital Storytelling Cookbook. Berkeley, CA: Digital Diner Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lambert J, Hill A, Mullen N, Paull C, Paulos E, Soundararajan T, & Weinshenker D. (2003). Digital storytelling cookbook and travelling companion Center for Digital Storytelling at the University of CA Berkeley. Digital Diner Press; Retrieved October, 17, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Lichtenthal WG, Currier JM, Neimeyer RA, & Keesee NJ (2010). Sense and significance: a mixed methods examination of meaning making after the loss of one’s child. Journal of clinical psychology, 66(7), 791–812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichtenthal WG, Neimeyer RA, Currier JM, Roberts K, & Jordan N. (2013). Cause of Death and the Quest for Meaning After the Loss of a Child. Death Studies, 37(4), 311–342. doi: 10.1080/07481187.2012.673533 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadeau JW (2001). Meaning making in family bereavement: A family systems approach. [Google Scholar]

- Neimeyer RA, Baldwin SA, & Gillies J. (2006). Continuing bonds and reconstructing meaning: Mitigating complications in bereavement. Death studies, 30(8), 715–738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiss D. (1981). The family’s construction of reality: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Robin BR (2008). Digital storytelling: A powerful technology tool for the 21st century classroom. Theory into practice, 47(3), 220–228. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson JA, & Hawpe L. (1986). Narrative thinking as a heuristic process. [Google Scholar]

- Rose CB (2016). The subjective spaces of social engagement: Cultivating creative living through community-based digital storytelling. Psychoanalysis, Culture & Society, 21(4), 386–402. [Google Scholar]

- Sadik A. (2008). Digital storytelling: A meaningful technology-integrated approach for engaged student learning. Educational technology research and development, 56(4), 487–506. [Google Scholar]

- Sedney MA, Baker JE, & Gross E. (1994). “The story” of a death: Therapeutic considerations with bereaved families. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 20(3), 287–296. [Google Scholar]

- Steffen E, & Coyle A. (2017). “I thought they should know… that daddy is not completely gone”: A Case Study of Sense-of-Presence Experiences in Bereavement and Family Meaning-Making. Omega: Journal of Death & Dying, 74(4), 363–385. doi: 10.1177/0030222816686609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stenhouse R, Tait J, Hardy P, & Sumner T. (2013). Dangling conversations: reflections on the process of creating digital stories during a workshop with people with early-stage dementia. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 20(2), 134–141. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2850.2012.01900.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- StoryCenter. (2017). StoryCenter: Listen deeply, tell stories. Retrieved from https://www.storycenter.org/

- Wang S, & Zhan H. (2010). Enhancing teaching and learning with digital storytelling. International Journal of Information and Communication Technology Education (IJICTE), 6(2), 76–87. [Google Scholar]

- Wexler L, Gubrium A, Griffin M, & DiFulvio G. (2013). Promoting positive youth development and highlighting reasons for living in Northwest Alaska through digital storytelling. Health Promotion Practice, 14(4), 617–623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]