Abstract

Fourteen (N = 14) bereaved family members participated in an exploratory study of Digital Storytelling as a bereavement intervention. The primary purpose of this study was to examine the feasibility of this approach, and to qualitatively assess potential impacts. Qualitative data revealed that for some, participation in Digital Storytelling facilitated growth and meaning-making. Themes from the data also revealed that participation in Digital Storytelling affected participants in these ways: a) the writing and verbalization of the script helped participants organize their thoughts and emotions about the loss; b) having the space to share with a collective group encouraged confidence in their ability to discuss their feelings with others; and c) the final product served as a source of closure for participants. Though this was a small exploratory study, results were promising and suggest the clinical applicability of Digital Storytelling as a tool for facilitating meaning-making among bereaved family members.

Introduction

The death of a family member is regarded as one of the most penetrating and emotionally complex losses an individual will endure (Cohen & Samp, 2017; Malkinson & Bar, 2016; Nadeau, 2001). It is not uncommon for bereaved individuals to avoid actively grieving as a way to protect themselves from the pain of losing a loved one. In fact, talking about the emotions associated with grief can be viewed as taboo (Cohen & Samp, 2017). Lack of communication about feelings of grief and loss after death often negatively affect one’s grieving trajectory and post-loss psychological functioning (Anderson, Arnold, Angus, & Bryce, 2008; Cohen & Samp, 2017; Herberman Mash, Fullerton, & Ursano, 2013; Shear et al., 2011). Confronting and communicating one’s grief, however, is said to increase meaning-making, which is argued to be essential for productive grieving and healing after the death of a loved one (Greenstein & Breitbart, 2000).

For many, creating a story about their experience of loss is a way to acknowledge pain, speak freely about grief, and make meaning of their experience (Gillies & Neimeyer, 2006; Lichtenthal, Neimeyer, Currier, Roberts, & Jordan, 2013; Lichtenthal et al., 2015; Nadeau, 2001; Neimeyer, 2000; Neimeyer, Baldwin, & Gillies, 2006). Interventions providing the bereaved with an opportunity to tell and retell the story of their loss can be highly effective in terms of reducing symptoms of complicated grieving, which is an intense form of grief that impacts one’s ability to function in their normal day-to-day life (Barnato et al., 2017; Bosticco & Thompson, 2005; Rosner, 2015). Moreover, grief experts advise that individuals who can communicate feelings of grief and talk openly about the death, as one does when telling a story, fare better than those who do not have the opportunity to process their loss (Alderfer et al., 2010).

Storytelling has long been used as a supportive tool for people who have experienced adverse life events, allowing them to process their emotions through narratives (Bosticco & Thompson, 2005; Nadeau, 2001). Research has shown that having a physical artifact (e.g., a photo, a script, etc.) can facilitate storytelling and sharing of emotional experiences, breaking the verbal barrier and promoting open communication (Rolbiecki, Anderson, Teti, & Albright, 2016; Rolbiecki, Washington, & Bitsicas, 2017; Teti, Rolbiecki, Zhang, Hampton, & Binson, 2016). Participants in Digital Storytelling, a multi-media narrative intervention, utilize artifacts such as photos and audio recordings of music and spoken word as building blocks for developing a story, typically about a significant event, place, or person (De Vecchi, Kenny, Dickson-Swift, & Kidd, 2016; Lambert, 2010). Documented benefits of Digital Storytelling for individuals processing an adverse life event such as the death of a family member include an improved sense of self, enhanced self-efficacy, and improved quality of life (Akard et al., 2015; Akard et al., 2013; Barnato et al., 2017; Foster, Dietrich, Friedman, Gordon, & Gilmer, 2012).

Theoretical Foundation/Conceptual Underpinning

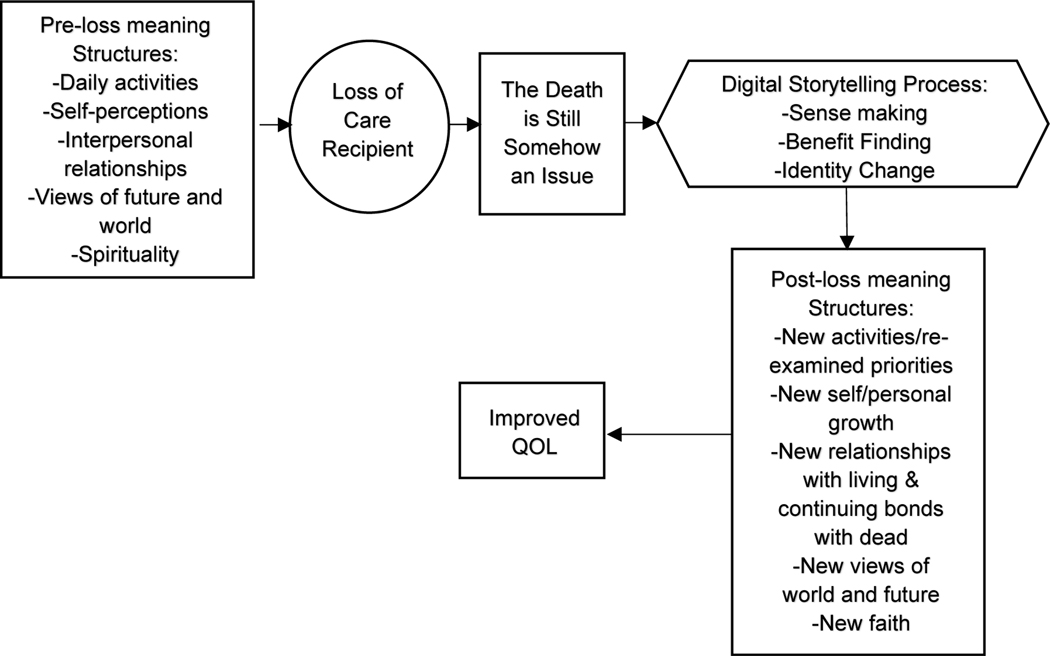

In the context of a bereavement intervention, we utilized a constructivist, meaning-making model to describe the potential impact of Digital Storytelling (Figure 1) for individuals who have experienced the death of a family member. This adapted model (Gillies & Neimeyer, 2006) suggests that bereaved family members will engage in meaning-making as a way to make sense of their loss (sense making), potentially find purpose in the experience (benefit finding), and incorporate this narrative into the larger context of their lives (identity change). By these processes, the bereaved can reconstruct their beliefs about the loss and its purpose in their life, and possibly decrease distress and the intensity of their grief (Gillies & Neimeyer, 2006).

Figure 1. Adapted Constructivist Meaning-Making Model.

Source: Gillies, J. & Neimeyer, R.A. (2006) Loss, grief, and the search for significance: Toward a model of meaning reconstruction in bereavement. Journal of Constructivist Psychology, 19, 31–65.

Study Aim

The overarching purpose of the study described herein was to better understand the experiences of individuals participating in a group Digital Storytelling intervention. Specifically, we sought to determine the feasibility of the intervention, to learn if and how the intervention affected participants’ ability to make meaning of their loss and communicate about it with others. Finally, we wanted to elicit participants’ suggestions for strengthening the intervention in the future.

Methods

Research Design, Recruitment, and Informed Consent

To achieve the aforementioned aims, we conducted a small, qualitative exploration of a Digital Storytelling intervention with bereaved family members (Tariq & Woodman, 2013). Following receipt of approval from the Principal Investigator’s Institutional Review Board (IRB), we recruited participants who met the following inclusion criteria: a) were at least 11 years old (to ensure cognitive ability to think abstractly (Harwood, Miller, & Vasta, 2008), b) had experienced the death of a family member, c) were able to communicate in spoken and written English, and d) knew or were willing to learn how to operate the smart technology required to complete the intervention (i.e., iMovie application on the Apple iPad Air 2). We partnered with local bereavement counselors, staff from a local palliative care program, churches, and a hospice agency to identify potential participants via flyering, word-of-mouth, and mass email messaging.

Because this was a minimal risk study, participants were asked to provide verbal consent to take part in the research. In addition, a process of re-consent was conducted throughout the study (i.e., facilitators continued to have conversations with participants about what it means to tell one’s story and share it with others and asked whether they wanted to continue). For minor participants, legal guardians were required to provide verbal consent for their child to participate; child assent was also obtained.

Data Collection and Analysis

Participants were asked to complete an in-depth group interview to qualitatively explore the feasibility of the intervention and its influence on meaning-making, growth, and communication (see Table 1 for the group interview guide). All interviews were digitally recorded and transcribed verbatim. To supplement interview transcripts, researchers kept notes about group interview sessions, noting participants’ non-verbal reactions to interview questions and other observations. Researchers also kept individual journals throughout all phases of the study, discussing their entries with one another with a goal of acknowledging and addressing biases, values, and judgements that could influence data analysis. Participants were compensated $100 total for their contributions ($50 after completing the Digital Storytelling workshop and $50 after completing the 30-day follow-up measures).

Table 1.

Digital Storytelling Group Interview Guide

| 1. If you all are comfortable, I’d like to begin by going around the room and having everyone share the most meaningful, and challenging part of participating in the Digital Storytelling workshop? |

| a. For adolescents use: Best and worst…or easiest/hardest |

| 2. What part of the Digital Storytelling process did you find most beneficial (e.g., story development, recording, filming, and sharing)? |

| 3. Would anyone like to share how they plan to use their digital stories in the future? |

| a. Probes: |

| i. To share with others as a way to remain connected with the deceased |

| ii. To share as a tool for communicating feelings of grief and loss |

| iii. To remember/”feel” |

| b. For adolescents – ask them to specifically state what they plan to do with their digital stories beyond the workshop. |

| i. Do you plan to show friends? Parents? Other families? |

| ii. How do you think it will feel to share with others, if you choose to do so? |

| 4. Please share your perceptions (i.e., thoughts and feelings) about digital storytelling as a bereavement intervention |

| a. Did you think it was helpful? |

| b. Not helpful? |

| c. For adolescents – How do you think other kids who have had a sibling die would benefit from participating in a digital storytelling workshop? |

| i. Is there anything you would share with them about your experience to prepare for their workshop? |

| 5. Please describe any challenges you had to participating in digital storytelling. |

| a. Probes: |

| i. Technical |

| ii. Emotional |

| iii. Starting digital storytelling |

| iv. Continuing digital storytelling |

| 6. Please describe how participating in digital storytelling impacted your ability to (or will impact your ability to)… |

| a. Make sense of your loss (e.g., it helped me piece together the timeline of the death) |

| b. Find benefit in the experience (if it did) |

| c. Incorporate the loss experience into the larger context of your life (e.g., I am who I am today because of my experience). |

| d. Continue your bond with the deceased. |

| e. For adolescents – tell me how your digital storytelling process helped you better understand the death, or make sense of it. |

| 7. How did your participation in the digital storytelling workshop impact your (if it did): |

| a. Depression |

| b. Anxiety |

| c. Grief |

| d. Relief |

| e. Hope |

| f. Coping |

| 8. What recommendations do you have to improve digital storytelling as a bereavement intervention? |

To analyze the qualitative data, the first two authors uploaded the transcribed interviews and researchers’ notes to Dedoose, a qualitative analysis software. They then analyzed them via thematic analysis, performed in the following steps:

The researchers familiarized themselves with the data by reading and re-reading the transcripts and notes, taking additional notes as they proceeded.

During this process, they developed a list of preliminary codes, which were reduced over time as the researchers attempted to make meaning of the codes.

The researchers then condensed their code lists into overarching themes, striving to develop themes that were robustly described and that told an accurate story about the data.

Digital Storytelling Workshop Procedures

All potential participants met in person with the study Principal Investigator prior to enrolling in the research project. In this initial meeting, they discussed requirements for study participation and began considering which artifacts they would include in their digital story. If interested in taking part in the project, participants were asked to provide verbal consent or assent, depending on their age. All (14 of 14) individuals who met with the Principal Investigator ultimately chose to participate in one of the two Digital Storytelling workshops (none withdrew before completion of the study). The Digital Storytelling workshops spanned five days and included two required full days, two optional evening sessions for technology support and check-ins, and one final required half-day session for group sharing of digital stories. A licensed clinical social worker was made available to participants for emotional support throughout the workshop and in the month afterward; however, participants generally opted to seek and provide emotional support to one another in the context of the larger group. A summary of participant involvement is provided in Table 2.

Table 2.

Summary of Participation

| Time | Study/Digital Storytelling Workshop Procedures |

|---|---|

| Pre-Workshop (face-to-face) visit | Explanation of study, investigator answered questions, gained consent, provided instruction for workshop (i.e., instructions to bring photos, and other memorable items to feature in the digital story). |

| 2 weeks prior to workshop | Participants were sent a REDCap link to complete their demographics form + baseline data collection. |

| Day 1: Saturday (full day) | Order of events: 1) Opening ceremony/rapport building, 2) overview of workshop activities, 3) discussion of respectful practices/Digital Storytelling examples 4) story development, 5) lunch break, 6) script building/script software 7) closing activity. |

| Day 2: Sunday (full day) | Order of events: 1) Rapport building, 2) individual script sharing and development, 3) audio recording training/participants recorded their audio 4) technical training with iMovie and image preparation was provided, 5) lunch break, 6) participants prepared images and continued to refine script, and 7) closing discussion. |

| Day 3: Monday (1/2 day) Optional | Order of events: 1) Brief welcome activity, 2) technical support in iMovie was provided to those who attended. |

| Day 4: Tuesday (1/2 day)Optional | Order of events: 1) Brief welcome activity, 2) technical support in iMovie was provided to those who attended. |

| Day 5: Wednesday (1/2 day) | Order of events: 1) Brief group rapport activity, 2) group sharing of stories, and 3) group interview. |

Workshop Content

Throughout the workshop, participants were asked to not only create their own digital stories but also to verbally share their thoughts in a series of story circles held on each mandatory day of the workshop. Active participation in each story circle was not required but strongly encouraged. During each story circle, participants were asked to pause the activity they were working on and form a circle with their chairs, which also left space for the facilitators.

During Story Circle 1, the main focus was on identifying the story the participant wanted to tell. Many discussions revolved around pinpointing each participant’s narrative after sharing lengthy stories with the group. Participants sometimes voiced reluctance to omit parts of the story in an effort to narrow it, equating that with omitting memories of their deceased family member. The facilitators aided participants in understanding how their stories could be divided into multiple parts and levels, not making any one section more important than the other. They reassured participants that there were many stories they could tell and that even the story they selected to tell in the workshop would continue to evolve over time.

The literature suggests that creating a sequenced timeline can sometimes be the most difficult part of storytelling for individuals who are attempting to unscramble traumatic events for the first time (Saltzman et al., 2017). This was true for many of our group participants, including several individuals whose reported loss experience would not be considered traumatic according to published psychological definitions (May & Wisco, 2016). In order to aid participants in their ability to coherently recall their experiences, facilitators helped them craft a timeline, encouraging them to place each event in the narrative in sequential order from beginning to end. This timeline was then used to develop a storyboard on which they could sketch out the story by drawing or using photographs they brought with them for the workshop. In this way, they transformed their written text into visual material. Beneath each box in their storyboards, participants placed text that corresponded to their images, helping them understand how to match the visual images with the scripted audio.

After the participants worked on their narratives and storyboards in the evening, they started the next day with Story Circle 2. This story circle focused on sharing their narratives aloud. The participants were reminded that the length of their narrative was important, since they would be matching visuals to each part of the story, as they did on their storyboards. The group offered supportive feedback on each narrative and offered suggestions on how to strengthen the work. Most participants shared their stories at this point; however, two individuals chose not to share their stories aloud during Story Circle 2. One of the two later felt ready to read their story aloud at the end of Day 2. The participants were then given time to adjust their narratives based on the feedback from the group before they recorded them as audio for their digital projects.

Story Circle 3, which was held on the last day of the workshop, served as the final story circle. At this time, participants shared their final digital stories, which contained both images and recorded audio. Each video was projected to the entire group with the lights in the room off. One facilitator handled the technology of playing each video, while the participants watched. There was no formal presentation on the part of the participant. After each story was shared, the group discussed their reactions, and the person sharing their video had an opportunity to further discuss how this process affected them. This process was symbolic of the participants re-entering their world with a narrative solely authored by themselves.

Results

Participant Characteristics

Fourteen (N = 14) total participants took part in the Digital Storytelling workshops (seven in each workshop). Most identified as female (n = 11) and White (n = 12), while three participants identified as male. Two of the male participants identified as African American. The sample consisted of a highly educated group, with about 50% reporting a graduate degree as their highest level of educational attainment, and approximately 21% reporting a bachelor’s degree. The mean age of the adult participants was 46 years (range = 24–64 years), and there were two adolescent participants (between the ages of 12 and 15) in the first workshop. Half of the participants (n = 7) took part in the intervention with family members. Three different families were represented among these individuals: two adolescent girls and their mother, one pair of sisters, and one pair of spouses participated together. One participant identified as a bereaved parent, while nine identified as bereaved children (i.e., son or daughter of the deceased), one identified as a widow, one identified as a bereaved sibling and a bereaved child, and two identified as “other” in terms of their relationship to the deceased (e.g., chosen family).

Qualitative Findings

Qualitative data from the in-depth interviews revealed that participation in the Digital Storytelling intervention affected participants in the following ways: 1) the writing, re-writing, and verbalization of the script helped participants organize their thoughts and emotions about the loss; 2) having the space to share openly and freely with a collective group encouraged confidence in their ability to discuss their feelings of loss and grief with others; and 3) the final product served as a source of closure for participants and helped some better understand the finality of the loss. Qualitative data also revealed that participation in Digital Storytelling contributed to personal growth for participants. Specifically, participants cited they felt a sense of pride their newly-acquired Digital Storytelling skills as well as a sense of mastery over their own self-narrative. These themes are further emphasized below with illustrative quotes from participants along with their suggestions for future Digital Storytelling workshops. (Note that the term “participants” is used below to refer to two or more study participants and cannot be assumed to be representative of all individuals taking part in the workshops.)

Digital Storytelling Facilitates Meaning-Making

Writing, reading, and verbalizing the script.

The process of writing, reading, and verbalizing the narrative piece of the digital story allowed participants to organize their thoughts about their grief and loss and their memories of their deceased family member. Some participants described how this organization allowed them to make sense of the loss, which led to a better understanding of its purpose in their life (e.g., “I now understand the purpose for our family going through this.”). For example, one participant described how this organization of memories and thoughts led to an increased sense of control: “Finally, I started to feel like my thoughts were getting more organized, and while they were still there, I felt more in control of them…the process of writing the script made it more concrete…[and I thought] ‘I have a handle on this’…my thoughts started to fall into place, and they began to belong.”

Participants also indicated that reading their stories aloud helped them make sense of their experiences. For example, one participant said, “Just putting it down and hearing your own voice encapsulating the story helps you realize this is what you think about [the death ]…. It does help you realize, ‘Okay, this is the story. This is how I see my story.’” Similarly, another participant expressed, “I guess it’s that connection with me and the words…if it’s just written down, I’m kind of removed from it…So I just recorded it. So I guess that’s what I should do in the future, is write down all my thoughts and then read them.”

Space for collective sharing.

Participants also expressed that, despite the fact that everyone’s bereavement experiences are different (though some were similar), the Digital Storytelling process led to a shared collective experience and was thus meaningful in terms of their healing. Along these lines, participants found that having a safe space to grieve as well as share stories about grief and loss with others was important and fostered a sense of confidence in their ability to talk openly about the loss. One participant described the Digital Storytelling intervention as a “laid-back version of therapy,” citing that “it’s a bunch of people I kind of feel comfortable with, rather than just one single person … It’s like a bonding experience, figuring out how to talk [about it] with other people.” Another participant shared their perceptions about the group dynamic and how it encouraged their ability to talk openly about the loss and their grief: “[This process] gave me permission to talk about grief…to talk about not-happy endings and to be honest about it because it’s icky. It’s not good. It’s not always happy, and [Digital Storytelling] makes it easier to be honest with yourself and with other people.” Another participant expressed, “Having this opportunity to share things…this safe place where you can share with each other … [allowed me to] share about my mother with people who don’t know her. It makes me feel like … I’m sharing her with other people, and it feels good to be able to do that.”

Completing the Digital Story.

Some participants described the impact of completing their digital story. One participant stated, “It felt like there was a certain finality about [it all].” Another participant described their process of finishing their digital story as “refreshing.” They said, “[Being done] felt good. It was a certain feeling of closure I got at the end…I’m not generally a big displayer of emotion, but [finishing and sharing it] was actually kind of refreshing. It was good to air it.” Though one participant acknowledged that their involvement in Digital Storytelling was challenging, she described her overall experience as meaningful. She said:

It was really challenging to look back on some of those pictures and stuff…some of them I hadn’t seen. It was hard to go back because I feel differently than I did when [my son] died, and so it’s a lot of the same, but new feelings…you relive it again….I don’t know if it’s just getting it all out, or what. But when I finished my [digital story] last night, I was really happy.

Finally, one participant spoke about how even though their digital story was a small piece of the overall narrative of the loss, it was satisfying and meaningful to have a final product. They said, “It’s satisfying to have a final product, even though it’s such a teeny-tiny piece of what I have to say…I still feel a lot of satisfaction in that.”

Digital Storytelling Facilitates Personal Growth

Many participants felt a feeling of accomplishment and pride related to mastering both the technology and their own narrative. For example, one participant described how they enjoyed learning the skills of Digital Storytelling, especially during a time of hopelessness. They said, “When you lose someone you love it can feel hopeless …. I like the idea of having a project and learning something new.” Another participant described how the Digital Storytelling process provided them the skills to “dig deeper into themselves and [their] story and why the [death] touched [them] so much.” In terms of mastering the technology, one participant said this about their experience:

When I first found out about this project … I didn’t know if I could do it. Then I thought, “I’m in a place where I can talk about this now.” I found out about the technology and thought there is just no way … we were taking something very emotional and trying to put it into something digital .… I thought this would be embarrassing because I wouldn’t be able to do anything …. But, as I finished it up I thought about everybody’s stories [including mine], and none of that was true … it didn’t matter.

Several participants discussed how even though the actual process of developing their story was emotionally difficult and challenging in terms of the technological aspects, they grew through their experience and re-claimed ownership of their story and narrative. For example, one participant said:

I think there are some revelatory moments in some of the imagery that you thought you understood [previously] … [I appreciate having the] opportunity to put one thing next to another in the context of whatever story you’re struggling to tell … It’s kind of symbolic of one’s battle with grief, too. It’s frustrating and annoying and can’t be controlled.… I think there is both the emotional experience [associated with grief] and the emotional experience of fearing technology and the desire for control and wrestling with imperfection.

Suggestions for Future Digital Storytelling Interventions

Though the Digital Storytelling workshop was feasibly executed over a 5-day period with bereaved individuals, participants offered many suggestions for improving the actual delivery of the intervention. For example, many participants expressed that they would have preferred comfortable, soft seating be available during the workshop as well as food and beverages (e.g., “Coffee and comfy couches. I mean, you’re not going to go wrong with that…. This is such stirring stuff, having some nurturing comfort while you are going through this [would be nice]”). Participants also agreed that, while it can be emotionally challenging to immerse yourself in the memories of the loss, the actual length of the workshop (5 days) was helpful in terms of facilitating meaning and healing (e.g., “I feel like I needed this intense crunch time to do it, or I just [wouldn’t]. I kind of dreaded it [at first], and I really didn’t want to jump back into it, but I am glad I did it, for sure”).

Many participants felt that having an additional day for orientation would be helpful (e.g., “I felt like it needed one day in front of the weekend…two to three hours of orientation, [discussing] expectations…[also] having one or two more days so there’s a breather…having a day off, or something like that, [would be good]”). Along these lines, one participant emphasized the importance of reiterating the emotional expectations and involvement associated with this type of intervention. They said, “I needed a little more instruction about how you may feel really raw and, you know, [need to] go find some quiet space and reenergize or something…I kept trying to figure out why I was feeling so crabby [during the workshop].” Participants agreed, however, that having too much time to work on the digital stories would not necessarily be beneficial (e.g., “I wouldn’t give it more than a week, like from Friday to finishing that next Sunday…If you do months, I’m not going to work on it until month 11”). Participants also particularly valued the optional technology support days and, while not everyone utilized them for their intended purpose (i.e., to have technical support in iMovie or with the iPad), many came to these sessions because they found that they needed a dedicated time and space to sort through their memories and emotions.

Participants found that the time since loss (i.e., the duration of bereavement) minimally shaped their experience participating in the Digital Storytelling intervention. That is, participants had varying degrees of time bereaved (i.e., 3 months up to 2.5 years), and these differences did not improve or hinder their ability to participate in or derive benefit from the intervention. One participant experienced the death of her mother 3.5 months before joining the study and said that the timing did not hinder her ability to participate. She said, “I didn’t think it was [too soon]…. It’s so different for everybody. There will be some people who, even after a few months, they can talk about it and then people after years who, you know, melt.” Interestingly, the different types of loss did not negatively affect participation in the Digital Storytelling intervention. In fact, some participants cited these differences as helpful in terms of showing them that they are not alone in their healing (e.g., “It was so nice for me to have different perspectives and for me to not be caught up in my story [only] but to hear other stories as well. I really appreciated how supportive everyone was, and I don’t know if another group would have been this good”).

Participants also discussed the importance of having facilitators that encouraged open discussion about their stories and feelings of grief and loss (e.g., “I think you guys did a great job nurturing the stories and getting us to talk a little bit. I don’t think that is an easy thing to do, and we all just kind of sat around [in the beginning]”). In general, participants agreed that facilitators should be skilled in the Digital Storytelling aspects of delivering the intervention and skilled in creating an open conversation about these stories and feelings (e.g., “someone who knows how to listen to the emotional part and, you know, how you are feeling and expressing it … [and someone] who can translate this into technology”). When asked specifically if they meant this could be the same person or should be different people, participants generally agreed that it could be one person with both skills or two different people; however, they emphasized that the two skillsets were fundamentally different and both important.

Discussion

Digital Storytelling is a feasible intervention that holds promise as a tool to support healing among individuals who have experienced the death of a family member. The workshop format provides ample support for participants with varying levels of experience to learn to use Digital Storytelling technologies. Physical space, dedicated time, emotional support, and technological support are all elements of the Digital Storytelling experience that contribute to its benefit.

Practice Implications

This study builds on an extensive body of literature demonstrating the clinical benefit of narrative interventions for individuals who have experienced death, grief, and loss (Akard et al., 2013; Akard et al., 2015; Barnato et al., 2017; De Vecchi, Kenny, Dickson-Swift, & Kidd, 2016; Foster, Dietrich, Friedman, Gordon, & Gilmer, 2012; Meichsner, Schinkothe, & Wilz, 2016). In addition, it enriches our understanding of how group interventions can be useful in processing serious adverse events. While larger studies are needed to conclusively determine the efficacy of Digital Storytelling in reducing psychological distress and promoting growth among individuals who have experienced the death of a family member, the qualitative data generated during this study highlight the promise of this therapeutic tool.

Deciding when and if to intervene after a person has experienced the death of a family member continues to be a challenge for bereavement professionals, and this was a key decision point in planning our Digital Storytelling intervention. Operating within this uncertainty, we opted to allow participants to self-select into the intervention, intentionally establishing broad inclusion criteria and specifically querying participants regarding their appropriateness. Participants in this study ranged anywhere between 3 months since death up to 2.5 years. Those who had experienced a recent death (i.e., those participating within 3–6 months of the death) expressed that engaging in Digital Storytelling during that time was helpful in terms of their healing, similar to others who had been bereaved longer. Others indicated that using time since death to determine when a person should join a Digital Storytelling intervention was unnecessary. Rather, there was broad support for allowing participants to self-select into the intervention, as we opted to do in this study.

Finally, while most participants indicated that they valued the concentrated timeframe in which the Digital Storytelling workshops were offered, the time required to participate in the intervention may serve as a barrier for some who would otherwise choose to take part. Offering Digital Storytelling in alternative formats, such as web-based group formats, may increase the accessibility of the intervention and give participants more control over their physical environment, which many cited as important. In addition, the reality that some participants experienced mood changes (e.g. increased irritability) is important to note. Researchers interested in studying Digital Storytelling as an intervention for bereaved individuals should work carefully with their IRB (or equivalent) to determine the appropriate level of risk presented by such studies; written rather than verbal consent may be deemed appropriate. In addition, individuals delivering Digital Storytelling interventions outside of the context of an ongoing clinical relationship should ensure that all participants have information on additional bereavement support options and other potentially useful resources. As the evidence base for Digital Storytelling grows, clinical considerations such as these should be central concerns.

Study Limitations

This study was largely qualitative and consisted of a small sample (N = 14) with no comparison group. Therefore, results are highly preliminary and reveal non-generalizable trends that should be explored in larger studies. In addition, the Digital Storytelling facilitators were present for group interviews, and their presence may have shaped participants’ responses. For example, participants might have been disinclined to provide critical feedback about the group processes or outcomes. Further, the Digital Storytelling workshops included multiple intervention components (e.g., sharing one’s story, hearing others’ stories, provision and receipt of support from group members and facilitators, dedicated time and space to reflect, opportunity to learn a new skill). It cannot be assumed that any one component was necessary or sufficient for bereaved participants to feel that they had made progress in dealing with their loss. Future research in this area would benefit from study designs that randomize participants to different study arms, with each of the arms receiving specified components of this complex, multicomponent intervention. In addition, collecting qualitative data via individual interviews rather than group interviews in the future would strengthen researchers’ ability to determine the representativeness of various perspectives among study participants. While the goal of qualitative inquiry is not typically to precisely quantify responses, it would nonetheless be helpful to know if, for example, ten participants mentioned the physical setting of the workshop as important or if it was only identified as important by two. In the context of group interviews, as were conducted in the present study, it is unlikely that participants would make the same point that had already been made multiple times even if they were in strong agreement, limiting researchers’ ability to understand the prevalence of different participant perspectives. Relatedly, member checking (Guba and Lincoln, 1989; i.e., sharing data, findings, and/or conclusions with participants to ensure that their experiences and perspectives are accurately reflected) would provide an opportunity for participants to voice support for specific assertions or challenge interpretations with which they disagree. Conducting individual versus group interviews would also decrease others’ influence on the data participants choose to provide, which may be particularly important for individuals taking part in Digital Storytelling with family members or other individuals with whom they share an ongoing relationship. Finally, this sample consisted of individuals with disproportionately high educational attainment for the geographic region, and was limited in terms of gender, racial, and ethnic diversity. Individuals with less formal education as well as individuals from different races and ethnicities may have very different experiences participating in Digital Storytelling as a bereavement intervention. These limitations should be considered in future studies of this intervention approach.

Acknowledgments

Funding Source: This project was supported by Grant R24HS022140 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors’ and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

Footnotes

Authors have no conflicts to disclose.

References

- Akard TF, Dietrich MS, Friedman DL, Hinds PS, Given B, Wray S, & Gilmer MJ (2015). Digital storytelling: An innovative legacy-making intervention for children with cancer. Pediatric Blood & Cancer, 62(4), 658–665. doi: 10.1002/pbc.25337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akard TF, Gilmer MJ, Friedman DL, Given B, Hendricks-Ferguson VL, & Hinds PS (2013). From qualitative work to intervention development in pediatric oncology palliative care research. Journal of Pediatric Oncology Nursing, 30(3), 153–160. doi: 10.1177/1043454213487434 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alderfer MA, Long KA, Lown EA, Marsland AL, Ostrowski NL, Hock JM, & Ewing LJ (2010). Psychosocial adjustment of siblings of children with cancer: A systematic review. Psycho‐Oncology, 19(8), 789–805. doi: 10.1002/pon.1638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson WG, Arnold RM, Angus DC, & Bryce CL (2008). Posttraumatic stress and complicated grief in family members of patients in the intensive care unit. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 23(11), 1871–1876. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0770-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnato AE, Schenker Y, Tiver G, Dew MA, Arnold RM, Nunez ER, & Reynolds CF (2017). Storytelling in the early bereavement period to reduce emotional distress among surrogates involved in a decision to limit life support in the ICU: A pilot feasibility trial. Critical Care Medicine, 45(1), 35–46. 10.1097/ccm.0000000000002009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosticco C, & Thompson TL (2005). Narratives and story telling in coping with grief and bereavement. OMEGA - Journal of Death and Dying, 51(1), 1–16. doi: 10.2190/8tnx-leby-5ejy-b0h6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen H, & Samp JA (2017). Grief communication: Exploring disclosure and avoidance across the developmental spectrum. Western Journal of Communication, 238–257. doi: 10.1080/10570314.2017.1326622 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- De Vecchi N, Kenny A, Dickson-Swift V, & Kidd S. (2016). How digital storytelling is used in mental health: A scoping review. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 25(3), 183–193. doi: 10.1111/inm.12206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster TL, Dietrich MS, Friedman DL, Gordon JE, & Gilmer MJ (2012). National survey of children’s hospitals on legacy-making activities. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 15(5), 573–578. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2011.0447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillies J, & Neimeyer RA (2006). Loss, grief, and the search for significance: Toward a model of meaning reconstruction in bereavement. Journal of Constructivist Psychology, 19(1), 31–65. doi: 10.1080/10720530500311182 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Greenstein M, & Breitbart W. (2000). Cancer and the experience of meaning: A group psychotherapy program for people with cancer. American Journal of Psychotherapy, 54(4), 486–500. doi: 10.1176/appi.psychotherapy.2000.54.4.486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guba EG, & Lincoln YS (1989). Fourth generation evaluation. Newbury Park, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, & Conde JG (2009). Research electronic data capture (REDCap): A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. Journal of Biomedical Informatics, 42(2), 377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harwood R, Miller SA, & Vasta R. Child psychology: Development in a changing society (5th ed). Hoboken, MJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Herberman Mash HB, Fullerton CS, & Ursano RJ (2013). Complicated grief and bereavement in young adults following close friend and sibling loss. Depression and Anxiety, 30(12), 1202–1210. doi: 10.1002/da.22068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JG, Harris ES, Spitzer RL, & Williams JB (2002). The patient health questionnaire for adolescents: validation of an instrument for the assessment of mental disorders among adolescent primary care patients. Journal of Adolescent Health, 30(3), 196–204. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(01)00333-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K, & Spitzer RL (2002). The PHQ-9: A new depression diagnostic and severity measure. Psychiatric Annals, 32(9), 509–515. doi: 10.3928/0048-5713-20020901-06 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, & Williams JB (2001). The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 16(9), 606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert J. (2010). Digital storytelling cookbook. Berkeley, CA: Digital Diner Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lichtenthal WG, Neimeyer RA, Currier JM, Roberts K, & Jordan N. (2013). Cause of death and the quest for meaning after the loss of a child. Death Studies, 37(4), 311–342. doi: 10.1080/07481187.2012.673533 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichtenthal WG, Sweeney CR, Roberts KE, Corner GW, Donovan LA, Prigerson HG, & Wiener L. (2015). Bereavement follow-up after the death of a child as a standard of care in pediatric oncology. Pediatric Blood & Cancer, 62(Suppl. 5), S834–S869. doi: 10.1002/pbc.25700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malkinson R, & Bar-Tur L. (2005). Long term bereavement processes of older parents: The three phases of grief. OMEGA - Journal of Death and Dying, 50(2), 103–129. doi: 10.2190/w346-up8t-rer6-bbd1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- May CL, & Wisco BE (2016). Defining trauma: How level of exposure and proximity affect risk for posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychological Trauma, 8(2), 233–240. doi: 10.1037/tra0000077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meichsner F, Schinkothe D, & Wilz G. (2016). Managing loss and change: Grief interventions for dementia caregivers in a CBT-based trial. American Journal of Alzheimers Disease and Other Dementias, 31(3), 231–240. doi: 10.1177/1533317515602085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadeau JW (2001). Meaning making in family bereavement: A family systems approach In Stroebe MS, Hansson RO, Stroebe W, & Schut H. (Eds.), Handbook of bereavement research: Consequences, coping, and care (pp. 329–347). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Neimeyer RA (2000). Searching for the meaning of meaning: Grief therapy and the process of reconstruction. Death Studies, 24(6), 541–558. doi: 10.1080/07481180050121480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neimeyer RA, Baldwin SA, & Gillies J. (2006). Continuing bonds and reconstructing meaning: Mitigating complications in bereavement. Death Studies, 30(8), 715–738. doi: 10.1080/07481180600848322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rolbiecki A, Anderson K, Teti M, & Albright DL (2016). “Waiting for the cold to end”: Using photovoice as a narrative intervention for survivors of sexual assault. Traumatology, 22(4), 242–248. doi: 10.1037/trm0000087 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rolbiecki AJ, Washington K, & Bitsicas K. (2017). Digital storytelling: Families’ search for meaning after child death. Journal of Social Work in End-of-Life and Palliative Care, 13(4), 239–250. doi: 10.1080/15524256.2017.1387216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosner R. (2015). Prolonged grief: Setting the research agenda. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 6, 27303. doi: 10.3402/ejpt.v6.27303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saltzman W, Layne C, Pynoos R, Olafson E, Kaplow J, & Boat B. (2017). Guide for conducting individual narrative and pull-out sessions In Trauma and grief component therapy for adolescents: A modular approach to treating traumatized and bereaved youth (pp. 154–161). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Shear MK, Simon N, Wall M, Zisook S, Neimeyer R, Duan N, … Ghesquiere A. (2011). Complicated grief and related bereavement issues for DSM‐5. Depression and Anxiety, 28(2), 103–117. doi: 10.1002/da.20780 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, & Lowe B. (2006). A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: The GAD-7. Archives of Internal Medicine, 166(10), 1092–1097. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tariq S, & Woodman J. (2013). Using mixed methods in health research. JRSM Short Reports, 4(6), 2042533313479197. doi: 10.1177/2042533313479197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teti M, Rolbiecki A, Zhang N, Hampton D, & Binson D. (2016). Photo-stories of stigma among gay-identified men with HIV in small-town America: A qualitative exploration of voiced and visual accounts and intervention implications. Arts & Health, 8(1), 50–64. doi: 10.1080/17533015.2014.971830 [DOI] [Google Scholar]