Abstract

Background

The risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD) and its mechanisms in children living with perinatally acquired HIV (PHIV) in sub-Saharan Africa has been understudied.

Methods

Mean common carotid artery intima-media thickness (IMT) and pulse-wave velocity (PWV) were evaluated in 101 PHIV and 96 HIV-negative (HIV−) children. PHIV were on ART, with HIV-1 RNA levels ≤400 copies/mL. We measured plasma and cellular markers of monocyte activation, T-cell activation, oxidized lipids, and gut integrity.

Results

Overall median (interquartile range, Q1–Q3) age was 13 (11–15) years and 52% were females. Groups were similar by age, sex, and BMI. Median ART duration was 10 (8–11) years. PHIV had higher waist–hip ratio, triglycerides, and insulin resistance (P ≤ .03). Median IMT was slightly thicker in PHIVs than HIV− children (1.05 vs 1.02 mm for mean IMT and 1.25 vs 1.21 mm for max IMT; P < .05), while PWV did not differ between groups (P = .06). In univariate analyses, lower BMI and oxidized LDL, and higher waist–hip ratio, hsCRP, and zonulin correlated with thicker IMT in PHIV (P ≤ .05). After adjustment for age, BMI, sex, CD4 cell count, triglycerides, and separately adding sCD163, sCD14, and hsCRP, higher levels of intestinal permeability as measured by zonulin remained associated with IMT (β = 0.03 and 0.02, respectively; P ≤ .03).

Conclusions

Our study shows that African PHIV have evidence of CVD risk and structural vascular changes despite viral suppression. Intestinal intestinal barrier dysfunction may be involved in the pathogenesis of subclinical vascular disease in this population.

Keywords: children with HIV, cardiovascular disease, gut integrity, immune activation, microbial translocation

Children with perinatally acquired HIV (PHIV) in Uganda have evidence of cardiovascular disease risk and structural vascular changes despite viral suppression with antiretroviral therapy. Intestinal barrier dysfunction may be involved in the pathogenesis of subclinical vascular disease in this population.

There are new challenges in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) care in sub-Saharan Africa, including management of noncommunicable diseases (NCDs) [1] and non–acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (non-AIDS) events, as well as understanding HIV treatment options in an expanding youth population due to the decline in child mortality [2]. The rates of NCDs rise faster in lower-income countries and often result in higher mortality compared with high-income countries [3].

In 2018, worldwide, over half of the children living with HIV under the age of 15 years needing antiretroviral therapy (ART) were receiving it [4]. The limited data in children living with HIV suggest that they have metabolic derangements [5, 6] and increased inflammation [7], suggesting that, similarly to adults, they may be at increased risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD). Therefore, as more children are surviving into adolescence and adulthood, it is imperative to evaluate their CVD risk and understand its pathogenesis to inform future prevention strategies. The available limited research evaluating non-AIDS comorbidities in children living with perinatally acquired HIV (PHIV) has been focused in high-income settings and it remains unclear how this relates to pediatric patients in lower-income countries where the majority of children living with HIV live.

Increasingly, data in non-HIV adult and pediatric populations have shown that surrogate markers of subclinical vascular diseases, such as carotid intima-medial thickness (IMT) and pulse-wave velocity (PWV), are predictive of important clinical outcomes, such as myocardial infarction and strokes [8–10]. In adults living with HIV, higher levels of systemic inflammation and immune activation markers have been linked to myocardial infarctions and all-cause mortality [11]. Development of pediatric studies has been hampered by lack of agreement on clinically significant and relevant outcomes. Although small cross-sectional studies in PHIV have already shown that inflammation markers correlate with carotid IMT [12] and hyperlipidemia [6], no sufficiently powered studies have been performed to assess the clinical significance of inflammation and immune activation on vascular disease in PHIV.

To our knowledge, no study has examined surrogate markers of CVD and its association with inflammation and immune activation in African PHIV on stable ART. In this study, we selected intestinal biomarkers based on prior data in PHIV in Uganda as well as in adults living with HIV suggesting their role in CVD and inflammation. Zonulin is a human protein that regulates intestinal permeability by modulating intercellular tight junctions [13]. Zonulin is increased in autoimmune diseases and has been used as a biomarker of impaired gut barrier function [13]. Zonulin and β-d-glucan (BDG), a polysaccharide cell-wall component of most fungal species, were found to be elevated in Ugandan PHIV and correlated with inflammation [14]. Intestinal fatty acid binding protein (I-FABP) is considered a marker of enterocyte damage [15]. Soluble CD14 (sCD14) is a soluble marker of monocyte activation, and is associated with mortality and progression of atherosclerosis [16]. The remaining biomarkers (high sensitivity C-reactive protein [hsCRP], soluble CD163 [sCD163], interleukin-6 [IL-6], oxidized lipids [oxidized LDL], and soluble tumor necrosis ɑ receptor I [sTNFR-I]) correlate with cardiometabolic complications, or drive other hallmarks of immune dysregulation in HIV.

The primary objective of this study was to determine whether surrogate markers of CVD were different between PHIV and uninfected Ugandan children (HIV-negative group); the second objective was to investigate the relationship between inflammation and immune activation and vascular disease, and the third was to assess the relationship between markers of gut integrity and CVD markers in this population.

METHODS

Study Design

This is a cross-sectional analysis of baseline data from an observational cohort study of PHIV and HIV-negative children prospectively enrolled at the Joint Clinical Research Center in Kampala, Uganda. The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee in Uganda, the Ugandan National Council of Science and Technology, as well as the Institutional Review Board of the University Hospitals Cleveland Medical Center, Cleveland, Ohio. Caregivers gave written informed consent; older children aware of their HIV status also gave informed assent following national guidelines. All participants were 10–18 years of age. PHIV participants were receiving ART for at least 2 years with a stable regimen for at least the last 6 months with an HIV-1 RNA of less than 400 copies/mL. Children who were HIV negative were tested during the clinic visit to confirm HIV seronegative status. Those with evidence of self-reported or documented acute infection (malaria, tuberculosis, helminthiasis, pneumonia, meningitis) in the last 3 months, as well as moderate or severe malnutrition and diarrhea in the last 3 months, were excluded. Those with known diabetes and heart disease were also excluded. Adolescents with pregnancy or intent to become pregnant were excluded.

Study Evaluations

Blood was drawn after an 8-hour fast. Blood was processed and plasma, serum, and peripheral blood mononuclear cells were cryopreserved for shipment to University Hospitals Cleveland Medical Center, Cleveland, Ohio. A Material Transfer Agreement, approval from the Uganda National Council of Science and Technology, as well as a permit from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention were obtained.

Cellular Markers of Monocyte and T-cell Activation

Monocytes and T cells were phenotyped by flow cytometry as previously described by Funderburg et al [17]. CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell activation was defined as co-expression of CD38 and human leukocyte antigen-DR isotype (HLA-DR). Monocyte subset proportions were determined by the relative expression of CD14 and CD16.

Inflammation, Soluble Immune Activation, and Gut Markers

Zonulin (PromoCell), BDG (Mybiosource, Inc), I-FABP, sCD14, sCD163, sTNFR-I, hsCRP, IL-6 (R&D Systems), and oxidized LDL (ALPCO and Mercodia) were measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). The intra-assay variability ranged between 4% and 8% and interassay variability was less than 10% for all markers. All assays were done at Dr Funderburg’s laboratory at Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio. Laboratory personnel were blinded to group assignments.

Subclinical Vascular Disease

To minimize differences of measurement, an experienced ultrasonographer performed all IMT and PWV at the Joint Clinical Research Centre, Kampala, Uganda, following published guidelines [18].

B-mode ultrasound scan of the carotid arteries was performed using a Philips iU22 ultrasound system with 12–3 MHz broadband linear array probe (Philips). Five-second cine loops of the distal common carotid artery (CCA) were obtained in longitudinal views at 3 angles (anterior, lateral, posterior) bilaterally. An experienced reader (D. L.), blinded to HIV status, measured the IMT offline using semiautomated edge-detection software (Medical Imaging Applications LLC). R-wave gated mean and maximum (max) far-wall IMT was measured in the distal 1-cm segment of the CCA. Measurements from all visualized segments obtained from the right and left sides were then averaged and reported as a single mean-mean IMT (subsequently referred to as mean IMT) and mean-max IMT (referred to as max IMT).

Pulse-wave velocity was measured by applanation tonometry (Vicorder; SMT Medical). The tonometer was applied to the carotid artery and femoral artery in sequence to obtain waveforms in relationship to the electrocardiogram tracing. Pulse-wave velocity was calculated as the distance (d) between the 2 recording sites minus that from the suprasternal notch to the carotid artery recording site, divided by the time delay (t) between the feet of the flow waves at these 2 sites (PWV = d/t). An average of 3 measurements was used for analyses. Higher-velocity measurements correspond to greater arterial stiffness.

Statistical Analysis

Medians and interquartile ranges (IQRs) are reported for continuous variables, and numbers and percentages are reported for categorical variables. All variables were compared between groups using Wilcoxon rank sum tests or chi-square test, as appropriate. Body mass index (BMI)-for-age z scores were determined using World Health Organization (WHO) 2007 reference values, which are a reconstruction of the 1977 National Center for Health Statistics/WHO reference. For visualization of the differences in cardiovascular measures between 2 groups, we presented mean-mean IMT and mean-max IMT using box plots. The relationships between CVD variables, demographic variables, HIV-related variables, and biomarkers were assessed using Spearman correlation analyses.

In subgroup analysis, t tests and Wilcoxon rank sum tests were used to compare IMT and PWV by sex and ART status. Multivariable quantile (median) regression models were used to explore the relationship between IMT and biomarkers in PHIV. Intima-media thickness was the outcome, and all variables with P < .1 in the correlation analysis were considered for inclusion. Separate models were constructed. The final model kept only those variables with P < .05, as well as clinically relevant variables. To this model, each marker of inflammation/immune activation with P < .05 or markers known to be associated with vascular disease in adults or with subclinical atherosclerosis in adults living with HIV [19] were added in turn to assess the variables that remained independently associated with the outcome or if the parameter estimate changed or was no longer significant. All statistical analyses were performed using the software Stata 15.0 and R 3.5.2.

RESULTS

Baseline

A total of 197 participants were enrolled, 101 PHIV and 96 HIV-negative children (Table 1). The overall median age was 13 years, and 52% of participants were females. There was no difference between age, gender, and BMI between the groups. Children living with perinatally acquired HIV had higher waist-to-hip ratio, homeostatic assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA) and worse lipid profiles (P ≤ .03). Only 9 participants had a known family history of hypertension, but none had a family history of atherosclerotic CVD or heart failure. Seven PHIV participants were orphans. None of the participants had any smoking history.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Participants

| PHIV (n = 101) | HIV Negative (n = 96) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 12.93 [11.53, 14.71] | 12.67 [11.08, 14.33] | .24 |

| Female sex, n (%) | 54 (53) | 50 (52) | .96 |

| HIV variables | |||

| Viral load <20 copies/mL, n (%) | 84 (86) | … | |

| CD4 nadir, cells/µL | 619.50 [333, 1097] | … | |

| CD4 cell count, cells/µL | 988 [638, 1307] | … | |

| CD4, % | 34.50 [27, 41] | … | |

| ART duration, years | 9.88 [7.61, 11.08] | ||

| Nucleotide reverse transcriptase inhibitors, n (%) | |||

| Abacavir | 42 (47) | … | |

| Lamivudine | 1 (1) | … | |

| Tenofovir | 12 (14) | … | |

| Zidovudine | 33 (37) | … | |

| Nevirapine, n (%) | 18 (27) | … | |

| Efavirenz, n (%) | 46 (44) | … | |

| Lopinavir/ritonavir, n (%) | 27 (28) | … | |

| CVD and metabolic parameters | |||

| Waist-to-hip ratio | 0.87 [0.83, 0.90] | 0.85 [0.82, 0.89] | .02* |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 17.69 [15.82, 19.10] | 18.02 [16.09, 19.46] | .34 |

| BMI-for-age z score | −0.57 [−1.29, −0.01] | −0.33 [−1.04, 0.36] | .066 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 107 [101, 114] | 115 [106, 121] | <.01* |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 65 [60, 71] | 67 [62, 73] | .07 |

| Creatinine, mg/dL | 0.48 [0.44, 0.55] | 0.49 [0.44, 0.56] | .30 |

| Albumin, g/dL | 4.30 [4.20, 4.50] | 4.40 [4.20, 4.55] | .11 |

| HOMA | 1.25 [0.80, 2.05] | 1.00 [0.74, 1.58] | .02* |

| Total cholesterol, mg/dL | 152 [134, 172] | 148 [131, 170] | .49 |

| LDL, mg/dL | 84 [68, 104] | 83 [70, 105] | .61 |

| VLDL, mg/dL | 19 [13, 23] | 16 [12, 20] | .03* |

| Triglycerides, mg/dL | 93 [66, 115] | 82 [61, 102] | .03* |

| Soluble markers of systemic inflammation and monocyte activation | |||

| hsCRP, ng/mL | 515.92 [185.69, 1619.31] | 398.60 [126.77, 1145.82] | .16 |

| IL-6, pg/mL | 1.13 [0.77, 2.12] | 1.23 [0.84, 1.86] | .93 |

| sTNFR-I, pg/mL | 905.46 [736.92, 1034.54] | 959.90 [811.10, 1107.97] | .02* |

| sCD14, pg/mL | 2110.70 [1759.38, 2568.92] | 1675.39 [1445.09, 1956.71] | <.01* |

| sCD163, pg/mL | 589.60 [404.24, 735.95] | 684.97 [495.51, 854.47] | .01* |

| Gut integrity markers | |||

| I-FABP, pg/mL | 2151.44 [1701.91, 3245.97] | 2241.48 [1687.72, 2966.32] | .49 |

| Zonulin, ng/mL | 6.16 [4.86, 7.79] | 6.79 [5.45, 8.40] | .065 |

| BDG, pg/mL | 283.66 [230.07, 488.86] | 448.65 [294.19, 613.45] | <.001* |

Data are presented as median [interquartile range] unless otherwise indicated. *P < .05.

Abbreviations: ART, antiretroviral therapy; BDG, β-d-glucan; BMI, body mass index; CVD, cardiovascular disease; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; HOMA, homeostatic assessment of insulin resistance; hsCRP, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein; I-FABP, intestinal fatty acid binding protein; IL-6, interleukin-6; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; PHIV, children with perinatally acquired human immunodeficiency virus; sCD14, soluble CD14; sCD163, soluble CD163; sTNFR-I, soluble tumor necrosis ɑ receptor I; VLDL, very-low-density lipoprotein.

Among PHIV, 86% had an undetectable viral load (<20 copies/mL), median CD4 cell count was 988 cells/µL, 72% were on a nonnucleotide reverse transcriptase inhibitor regimen, 28% were on lopinavir/ritonavir (LPV/r), and 2 participants were on dolutegravir. Median ART duration was 10 years, with 8 participants initiating ART under the age of 1 year and the rest between the ages of 2 and 10 years. All PHIV were on cotrimoxazole. None of the participants were receiving tuberculosis medications.

Subclinical Vascular Disease

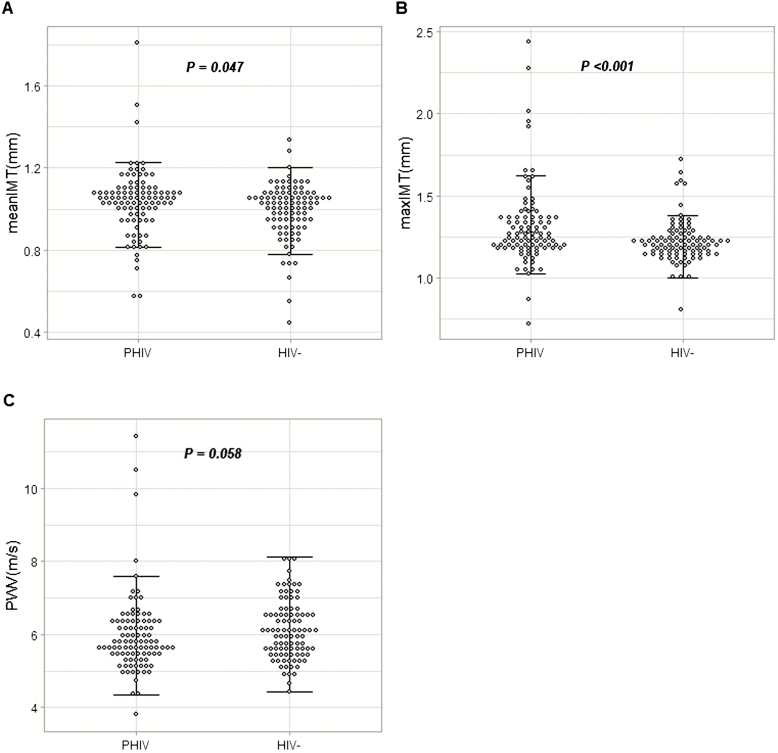

Children living with perinatally acquired HIV had worse IMT (1.05 vs 1.02 mm for mean IMT and 1.25 vs 1.21 mm for max IMT; P ≤ .05) (Figure 1A, B); however, there was no difference in arterial stiffness as measured by PWV between the groups (P = .06) (Figure 1C).

Figure 1.

Vascular measures. Dot plots showing the mean-mean IMT (mm) (A), mean-max IMT (mm) (B), and PWV (m/s) (C) in PHIV and HIV− children. Horizontal lines denote the interquartile range. Abbreviations: HIV−, human immunodeficiency virus negative; IMT, intima-media thickness; max, maximum; PHIV, children with perinatally acquired human immunodeficiency virus; PWV, pulse-wave velocity.

In unadjusted analyses, there was no difference in IMT or PWV between sexes (both P ≥ .08). Among PHIV, there were no differences in IMT or PWV when current users of abacavir or LPV/r were compared with nonusers (P ≥ .08).

Variables Associated With Cardiovascular Disease Measures

In univariate analyses, lower BMI and lower oxidized LDL, as well as higher waist-to- hip ratio, hsCRP, and zonulin, correlated with thicker mean or max IMT in PHIV (Table 2). None of the lymphocyte or monocyte activation markers correlated with IMT.

Table 2.

Correlations With Mean-Mean and Mean-Max Common Carotid Artery Intima-media Thickness in Children Living With Perinatally Acquired Human Immunodeficiency Virus

| Mean-Mean IMT | Mean-Max IMT | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ρ | P | ρ | P | |

| Traditional risk factors | ||||

| Age, years | −0.04 | .70 | −0.05 | .80 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | −0.30* | <.01* | −0.21* | .04* |

| Waist-to-hip ratio | 0.07 | .50 | 0.16* | .05* |

| HOMA | −0.10 | .32 | 0.04 | .71 |

| LDL, mg/dL | −0.07 | .44 | −0.11 | .23 |

| Triglycerides, mg/dL | 0.05 | .56 | 0.18 | .07 |

| HIV-related factors | ||||

| CD4 cell count, cells/µL | −0.11 | .24 | 0.06 | .53 |

| CD4 nadir, cells/µL | −0.11 | .28 | 0.10 | .33 |

| ART duration, years | 0.06 | .52 | 0.04 | .64 |

| Inflammatory markers | ||||

| hsCRP, ng/mL | −0.05 | .59 | 0.24* | .02* |

| IL-6, pg/mL | 0.07 | .47 | 0.15 | .15 |

| sTNFR-I, pg/mL | −0.12 | .23 | 0.03 | .78 |

| Cellular and soluble monocyte markers | ||||

| sCD14, pg/mL | 0.07 | .49 | 0.01 | .90 |

| sCD163, pg/mL | 0.06 | .54 | 0.05 | .62 |

| CD14+CD16−, % | −0.11 | .34 | −0.09 | .45 |

| CD14dimCD16+, % | 0.15 | .21 | 0.09 | .45 |

| CD14+CD16+, % | 0.07 | .52 | 0.07 | .54 |

| Lymphocyte activation | ||||

| CD4+CD38+,% | 0.17 | .12 | 0.04 | .71 |

| CD4+ HLA-DR+ % | 0.01 | .91 | 0.01 | .89 |

| CD4+CD38+ HLA-DR+, % | < −0.01 | .99 | 0.09 | .35 |

| CD8+CD38+, % | 0.02 | .88 | −0.05 | .62 |

| CD8+ HLA-DR+, % | −0.08 | .45 | −0.07 | .50 |

| CD8+CD38+ HLA-DR+, % | 0.03 | .77 | 0.03 | .80 |

| Gut integrity markers | ||||

| I-FABP, pg/mL | < −0.01 | .99 | 0.08 | .44 |

| Zonulin, ng/mL | 0.30* | <.01* | 0.07 | .52 |

| BDG, pg/mL | −0.04 | .68 | −0.04 | .68 |

| Oxidized lipids | ||||

| Ox LDL, mU/L | −0.16 | .08 | −0.26* | <.01* |

*P < .05.

Abbreviations: ART, antiretroviral therapy; BDG, β-d-glucan; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; HLA-Dr, human leukocyte antigen-DR isotype; HOMA, homeostatic assessment of insulin resistance; hsCRP, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein; I-FABP, intestinal fatty acid binding protein; IL-6, interleukin-6; IMT, intima-media thickness; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; max, maximum; Ox, oxidized; sCD14, soluble CD14; sCD163, soluble CD163; sTNFR-I, soluble tumor necrosis ɑ receptor I.

In HIV-negative participants, lower hsCRP, sCD14, and oxidized LDL and higher HDL correlated with thicker IMT (P < .05).

In separate quantile regression models in PHIV, after adjusting for CVD and HIV-related variables and, separately, markers of monocyte activation sCD163, sCD14, and systemic inflammation hsCRP, higher intestinal permeability (zonulin) remained associated with IMT (Table 3). Older age, higher triglycerides and CD4 cell count, and lower BMI were also independently associated with thicker IMT in all models.

Table 3.

Quantile Regression Models of the Associations With Mean Intima-media Thickness in Children Living With Perinatally Acquired Human Immunodeficiency Virus

| 95% CI | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictors | Coef. | SE | P | LL | UL |

| Model 1 | |||||

| Zonulin, ng/mL | 0.0176 | 0.0085 | .041* | .0008 | .0345 |

| Age, years | 0.0288 | 0.0099 | .005* | .0091 | .0485 |

| Sex (male) | −0.0026 | 0.0174 | .882 | −.0372 | .0320 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | −0.0327 | 0.0098 | .001* | −.0522 | −.0131 |

| Triglycerides, mg/dL | 0.0241 | 0.0091 | .009* | .0061 | .0421 |

| HOMA | −0.0006 | 0.0093 | .952 | −.0190 | .0178 |

| CD4 cell count, cells/μL | 0.0322 | 0.0096 | .001* | .0131 | .0514 |

| Model 2 | |||||

| Zonulin, ng/mL | 0.0229 | 0.0079 | .005* | .0069 | .0387 |

| Age, years | 0.014 | 0.004 | <.001* | .0068 | .0217 |

| Sex (male) | −0.0182 | 0.147 | .219 | −.0475 | .0110 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | −0.0377 | 0.0081 | <.001* | −.0538 | −.0216 |

| Triglycerides, mg/dL | 0.0175 | 0.0077 | .026* | .0021 | .0328 |

| CD4 cell count, cells/μL | 0.0230 | 0.0083 | .007* | .0065 | .3965 |

| sCD163, pg/mL | −0.0108 | 0.0077 | .163 | −.0261 | .0044 |

| Model 3 | |||||

| Zonulin, ng/mL | 0.0176 | 0.0082 | .034* | .0014 | .0339 |

| Age, years | 0.0283 | 0.0096 | .004* | .0093 | .0473 |

| Sex (male) | −0.0027 | 0.0173 | .878 | −.0371 | .0317 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | −0.0325 | 0.0096 | .001* | −.0515 | −.0135 |

| Triglycerides, mg/dL | 0.0242 | 0.0087 | .007* | .0068 | .0415 |

| HOMA | −0.0008 | 0.0089 | .932 | −.0186 | .0170 |

| CD4 cell count, cells/μL | 0.0323 | 0.0093 | .001* | .0138 | .0508 |

| hsCRP, ng/mL | 0.0096 | 0.0080 | .233 | −.0063 | .0254 |

| Model 4 | |||||

| Zonulin, ng/mL | 0.0173 | 0.0077 | .027* | .0021 | .0327 |

| Age, years | 0.0111 | 0.0040 | .006* | .0032 | .0190 |

| Sex (male) | 0.0039 | 0.0157 | .802 | −.0272 | .0351 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | −0.0302 | 0.0086 | .001* | −.0472 | −.0132 |

| Triglycerides, mg/dL | 0.0248 | 0.0082 | .003* | .0086 | .0411 |

| CD4 cell count, cells/μL | 0.0343 | 0.0088 | <.001* | .0168 | .0518 |

| sCD14, pg/mL | 0.0037 | 0.0074 | .621 | .0168 | .0183 |

Quantile (median) regression equation for biomarkers: Qτ(y) = β 0(τ) + β 1(τ)X + β 2(τ) age + β 3(τ) Male + β 4(τ) BMI + β 5(τ) Triglyceride + β 6(τ) HOMA + β 7(τ) Absolute CD4 + β8(τ) X8, where y is either mean IMT, X8 is either sCD163, sCD14, or hsCRP; τ = 0.5 for median regression, X is intestinal integrity variable (Zonulin), and β is the associated regression coefficient. We defined sex as female or male. *P < .05.

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; CI, confidence interval; Coef., regression coefficients; HOMA, homeostatic assessment of insulin resistance; hsCRP, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein; LL, lower limit of the regression coefficients; sCD14, soluble CD14; sCD163, soluble CD163; SE, standard error of the estimates; UL, upper limit of the regression coefficients.

DISCUSSION

We found that African children with perinatally acquired HIV have evidence of elevated CVD risk despite viral suppression. We also describe a moderate association with intestinal barrier dysfunction that appears to be independent of the traditional risk factors frequently seen in studies of adults living with HIV.

Globally, the African population is more likely to be affected by CVD at a younger age [20], and although data are sparse, HIV is an important risk factor in young Africans [21]. Since the majority of the 2 million children with HIV reside on the African continent, it is imperative to fill the knowledge discrepancies on the risk factors and potential mechanisms of CVD in this population. There are few data on both functional (PWV) and structural (IMT) markers of CVD in PHIV on ART in this region. There are conflicting reports on differences in IMT between PHIV and HIV-negative children in higher-income settings [22–26]. To date, only 3 other cross-sectional studies have measured arterial stiffness with PWV in pediatric HIV [16, 27, 28]. In these reports, the sample size was generally small; the participants and HIV-negative children varied widely in age, ART use, and viremia; and varying anatomic sites were used to measure IMT and PWV. Among these studies, only one has assessed IMT and PWV in African children [27]. This study found increased PWV and IMT in efavirenz- and LPV/r-treated children compared with those treated with nevirapine; however, there was no control group for comparison. In our study, we report no difference in arterial stiffness between the groups, although IMT was slightly higher in PHIV. Similarly to our findings, reported differences in IMT in children with HIV included in prior studies have ranged from 0.02 to 0.15 mm. Although small, this difference may be clinically meaningful considering that, in uninfected adults, each 0.03-mm increase per year in carotid IMT has been associated with a 2-fold increase in coronary death and a 3-fold increase in coronary events [26]. A recent pooled analysis of over 2000 individuals with and without HIV in the United States found that children and youth living with HIV had greater IMT thickness even after controlling for demographic characteristics and CVD risk factors [29], and HIV infection itself appeared to be the main risk factor for increased carotid artery thickening in this population compared with adults.

The underlying mechanisms of increased CVD risk in HIV are multifactorial and complex. The pathophysiology may differ in African PHIV because of the following factors: (1) most have had a lifelong exposure to HIV and ART (including potentially in utero); (2) they lack other risk factors such as hypertension, smoking, and substance use that contribute to CVD in adults with HIV; and (3) there may be differences in ethnicity, genetics, nutritional factors, and coinfections that could impact cardiometabolic outcomes. As such, we aimed to explore potential contributors to increased IMT in this population. Children living with perinatally acquired HIV in our study have metabolic complications compared with uninfected children, including dyslipidemia, insulin resistance, and higher waist-to-hip ratio, all of which can contribute to CVD. We found that higher triglycerides and lower BMI were associated with IMT. Lower weight in this population is likely associated with detrimental outcomes, although there might be a tipping point at which weight gain begins to have negative consequences.

Certain ART has also been associated with CVD events, specifically protease inhibitors [30] and abacavir [31] have been associated with an elevated risk of myocardial infarctions. We did not find increased IMT in participants on protease inhibitors (specifically lopinavir-boosted ritonavir) or abacavir; however, we may not have been sufficiently powered to detect a difference by treatment group. Higher current CD4 cell count was associated with thicker IMT. This study is a cross-sectional analysis and CD4 cell counts are no longer routinely performed in resource-limited settings; therefore, this finding may reflect a recent CD4 recovery and health improvement.

In adults living with HIV, chronic inflammation and immune activation are predictive of mortality and have been associated with atherosclerosis [32–34]. Similarly to adults, children with HIV have ongoing inflammation and immune activation compared with uninfected children [6, 12, 24]. Sustained immune activation also persists in PHIV despite ART and viral suppression [5–7]; however, there is a paucity of data on the relationship between inflammation and cardiometabolic complications in this population, especially in lower-income settings.

We have previously shown that monocyte activation is associated with insulin resistance in Ugandan PHIV [5]. Two prior studies, both in higher-income settings, have evaluated the relationship between inflammation and IMT in PHIV [12, 24] and showed conflicting findings. In a study conducted at our US site (Cleveland), McComsey et al [22] showed higher IMT in children with HIV, with a subsequent follow-up showing that increased hsCRP was independently associated with thicker IMT [12]. On the other hand, Sainz et al [24] (Spain) reported that PHIV had thicker IMT but found no relation between IMT and inflammation or immune activation. Blood monocytes, tissue macrophages, and T cells are known mediators of atherosclerosis. In addition, the markers of monocyte activation sCD14 and sCD163 have been associated with atherosclerosis in adults with HIV [32]. Interestingly, unlike what has been described in adults, we found no correlation between IMT and the markers of systemic inflammation monocyte and T-cell activation. Our findings add to the limited evidence that, in PHIV, T-cell activation may not necessarily be linked to complications [35, 36].

Alteration in intestinal integrity and subsequent microbial translocation appears to be a central factor in HIV-associated chronic immune activation [37]. We have previously shown that Ugandan PHIV have evidence of alteration in intestinal permeability as measured by zonulin and that, similarly to adults, intestinal damage and microbial translocation may play a role in heightened inflammation [15]. Recent findings also suggest that gut dysbiosis in treated PHIV is associated with cardiac biomarkers [38]. In both type I diabetes and celiac disease, zonulin upregulation seems to precede the onset of disease [13, 39], suggesting a link similar to HIV between increased permeability, environmental exposure, and ongoing inflammation. There are no data on the role of intestinal integrity damage and its potential link to CVD in PHIV. We found that intestinal barrier dysfunction as measured by zonulin was independently associated with thicker IMT, even after adjusting for potential confounders. Our findings may suggest that HIV-induced enteropathy characterized by increased intestinal permeability and damage may be associated with CVD independently of chronic inflammation.

The inclusion of a well-matched control group from the same area in Uganda is a strength of our study as participants did not differ in demographic characteristics and important risk factors. The comprehensive evaluation of inflammation, immune activation, and gut markers is an additional strength. As in all cross-sectional studies, we cannot prove causal relationships or exclude the possibility of residual confounding. Additionally, we did not assess the gastrointestinal microbiome composition to further evaluate gut dysbiosis. We did not measure zonulin using a monoclonal antibody assay and caution should be used when interpreting zonulin ELISA assays [40]. Although we excluded participants with malaria, tuberculosis, and diarrhea, we did not evaluate other viral etiologies such as cytomegalovirus or Epstein Barr virus, which could contribute to immune activation in this population.

In conclusion, African PHIV show evidence of subclinical vascular disease that is associated with intestinal barrier dysfunction. Longitudinal follow-up of this cohort is ongoing and may yield further insights into CVD risk and its pathophysiology in PHIV.

Notes

Author contributions. S. D.-F. and G. A. M. designed the study. S. D.-F. obtained funding. R. N., C. K., and V. M. oversaw study evaluations and monitoring. A. S. and Z. A. provided statistical support. E. B. and N. F. performed the biomarker assays and flow cytometry. C. T. L. provided technical assistance with the vascular measures. D. L. performed all intima-media thickness measurements. S. D.-F. wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors contributed to data analysis and reviewed the manuscript for intellectual content.

Acknowledgments. The authors thank the patients who participated in this research.

Financial support. This work was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (grant number K23HD088295-01A1; to S. D.-F.).

Potential conflicts of interest. G. A. M. served as a consultant for Gilead, GlaxoSmithKline (GSK)/Viiv, and Merck and has received research funding from Gilead, Merck, GSK/Viiv, Roche, Astellas, Tetraphase, and Bristol Meyer Squibb. C. T. L. has received research funding from Gilead and serves on the advisory board for Esperion. N. F. serves as a consultant for Gilead and has received grants from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. All other authors report no potential conflicts. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1. Global Burden of Disease 2015 Mortality and Causes of Death Collaborators. Global, regi onal, and national life expectancy, all-cause mortality, and cause-specific mortality for 249 causes of death, 1980–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet 2016; 388:1459–544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. UNAIDS. The youth bulge and HIV. UN Joint Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDs), 2018. Available at: https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/the-youth-bulge-and-hiv_en.pdf. Accessed 2 December 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Alwan A, Maclean DR. A review of non-communicable disease in low- and middle-income countries. Int Health 2009; 1:3–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. UNAIDS. AIDS info. UN Joint Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDs), 2019. Available at: http://aidsinfo.unaids.org/. Accessed 2 December 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Dirajlal-Fargo S, Musiime V, Cook A, et al. Insulin resistance and markers of inflammation in HIV-infected Ugandan children in the CHAPAS-3 trial. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2017; 36:761–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Miller TI, Borkowsky W, DiMeglio LA, et al. ; Pediatric HIV/AIDS Cohort Study (PHACS) Metabolic abnormalities and viral replication are associated with biomarkers of vascular dysfunction in HIV-infected children. HIV Med 2012; 13:264–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Eckard AR, Rosebush JC, Lee ST, et al. Increased immune activation and exhaustion in HIV-infected youth. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2016; 35:e370–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Terai M, Ohishi M, Ito N, et al. Comparison of arterial functional evaluations as a predictor of cardiovascular events in hypertensive patients: the Non-Invasive Atherosclerotic Evaluation in Hypertension (NOAH) study. Hypertens Res 2008; 31:1135–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mattace-Raso FU, van der Cammen TJ, Hofman A, et al. Arterial stiffness and risk of coronary heart disease and stroke: the Rotterdam Study. Circulation 2006; 113:657–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Shokawa T, Imazu M, Yamamoto H, et al. Pulse wave velocity predicts cardiovascular mortality: findings from the Hawaii-Los Angeles-Hiroshima study. Circ J 2005; 69:259–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Tien PC, Choi AI, Zolopa AR, et al. Inflammation and mortality in HIV-infected adults: analysis of the FRAM study cohort. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2010; 55:316–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ross AC, O’Riordan MA, Storer N, Dogra V, McComsey GA. Heightened inflammation is linked to carotid intima-media thickness and endothelial activation in HIV-infected children. Atherosclerosis 2010; 211:492–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sapone A, de Magistris L, Pietzak M, et al. Zonulin upregulation is associated with increased gut permeability in subjects with type 1 diabetes and their relatives. Diabetes 2006; 55:1443–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Dirajlal-Fargo S, El-Kamari V, Weiner L, et al. Altered intestinal permeability and fungal translocation in Ugandan children with HIV. Clin Infect Dis 2019. doi:10.1093/cid/ciz561 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Pelsers MM, Namiot Z, Kisielewski W, et al. Intestinal-type and liver-type fatty acid-binding protein in the intestine: tissue distribution and clinical utility. Clin Biochem 2003; 36:529–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Charakida M, Loukogeorgakis SP, Okorie MI, et al. Increased arterial stiffness in HIV-infected children: risk factors and antiretroviral therapy. Antivir Ther 2009; 14:1075–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Funderburg NT, Jiang Y, Debanne SM, et al. Rosuvastatin treatment reduces markers of monocyte activation in HIV-infected subjects on antiretroviral therapy. Clin Infect Dis 2014; 58:588–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Dalla Pozza R, Ehringer-Schetitska D, Fritsch P, Jokinen E, Petropoulos A, Oberhoffer R; Association for European Paediatric Cardiology Working Group Cardiovascular Prevention Intima media thickness measurement in children: a statement from the Association for European Paediatric Cardiology (AEPC) Working Group on Cardiovascular Prevention endorsed by the Association for European Paediatric Cardiology. Atherosclerosis 2015; 238:380–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Subramanya V, McKay HS, Brusca RM, et al. Inflammatory biomarkers and subclinical carotid atherosclerosis in HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected men in the Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study. PLoS One 2019; 14:e0214735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Keates AK, Mocumbi AO, Ntsekhe M, Sliwa K, Stewart S. Cardiovascular disease in Africa: epidemiological profile and challenges. Nat Rev Cardiol 2017; 14:273–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Benjamin LA, Corbett EL, Connor MD, et al. HIV, antiretroviral treatment, hypertension, and stroke in Malawian adults: a case-control study. Neurology 2016; 86:324–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. McComsey GA, O’Riordan M, Hazen SL, et al. Increased carotid intima media thickness and cardiac biomarkers in HIV infected children. AIDS 2007; 21:921–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Charakida M, Donald AE, Green H, et al. Early structural and functional changes of the vasculature in HIV-infected children: impact of disease and antiretroviral therapy. Circulation 2005; 112:103–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sainz T, Álvarez-Fuente M, Navarro ML, et al. ; Madrid Cohort of HIV-infected children and adolescents integrated in the Pediatric branch of the Spanish National AIDS Network (CoRISPE) Subclinical atherosclerosis and markers of immune activation in HIV-infected children and adolescents: the CaroVIH Study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2014; 65:42–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bonnet D, Aggoun Y, Szezepanski I, Bellal N, Blanche S. Arterial stiffness and endothelial dysfunction in HIV-infected children. AIDS 2004; 18:1037–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Chanthong P, Lapphra K, Saihongthong S, et al. Echocardiography and carotid intima-media thickness among asymptomatic HIV-infected adolescents in Thailand. AIDS 2014; 28:2071–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Eckard AR, Raggi P, Ruff JH, et al. Arterial stiffness in HIV-infected youth and associations with HIV-related variables. Virulence 2017; 8:1265–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Gleason RL Jr, Caulk AW, Seifu D, et al. Efavirenz and ritonavir-boosted lopinavir use exhibited elevated markers of atherosclerosis across age groups in people living with HIV in Ethiopia. J Biomech 2016; 49:2584–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hanna DB, Guo M, Bůžková P, et al. HIV infection and carotid artery intima-media thickness: pooled analyses across 5 cohorts of the NHLBI HIV-CVD collaborative. Clin Infect Dis 2016; 63:249–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ryom L, Lundgren JD, El-Sadr W, et al. ; D:A:D Study Group Cardiovascular disease and use of contemporary protease inhibitors: the D:A:D international prospective multicohort study. Lancet HIV 2018; 5:e291–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Elion RA, Althoff KN, Zhang J, et al. ; North American AIDS Cohort Collaboration on Research and Design of IeDEA Recent abacavir use increases risk of type 1 and type 2 myocardial infarctions among adults with HIV. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2018; 78:62–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Longenecker CT, Jiang Y, Orringer CE, et al. Soluble CD14 is independently associated with coronary calcification and extent of subclinical vascular disease in treated HIV infection. AIDS 2014; 28:969–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hileman CO, Longenecker CT, Carman TL, McComsey GA. C-reactive protein predicts 96-week carotid intima media thickness progression in HIV-infected adults naive to antiretroviral therapy. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2014; 65:340–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hsu DC, Ma YF, Hur S, et al. Plasma IL-6 levels are independently associated with atherosclerosis and mortality in HIV-infected individuals on suppressive antiretroviral therapy. AIDS 2016; 30:2065–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kapetanovic S, Aaron L, Montepiedra G, Burchett SK, Kovacs A. T-cell activation and neurodevelopmental outcomes in perinatally HIV-infected children. AIDS 2012; 26:959–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Romeiro JR, Pinto JA, Silva ML, Eloi-Santos SM. Further evidence that the expression of CD38 and HLA-DR(+) in CD8(+) lymphocytes does not correlate to disease progression in HIV-1 vertically infected children. J Int Assoc Physicians AIDS Care (Chic) 2012; 11:164–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Alzahrani J, Hussain T, Simar D, et al. Inflammatory and immunometabolic consequences of gut dysfunction in HIV: parallels with IBD and implications for reservoir persistence and non-AIDS comorbidities. EBioMedicine 2019; 46:522–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Sessa L, Reddel S, Manno E, et al. Distinct gut microbiota profile in antiretroviral therapy-treated perinatally HIV-infected patients associated with cardiac and inflammatory biomarkers. AIDS 2019; 33:1001–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Fasano A. Zonulin, regulation of tight junctions, and autoimmune diseases. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2012; 1258:25–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Ajamian M, Steer D, Rosella G, Gibson PR. Serum zonulin as a marker of intestinal mucosal barrier function: may not be what it seems. PLoS One 2019; 14:e0210728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]