Abstract

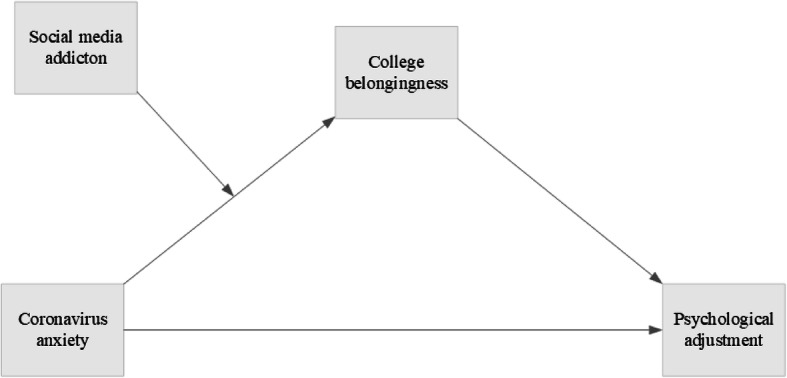

The psychological health of people all around the world is severely affected due to the COVID-19 outbreak. This study examined a moderated mediation model in which college belongingness mediated the relationship between coronavirus anxiety and psychological adjustment, and this mediation effect was moderated by social media addiction. A total of 315 undergraduate students (M = 21.65±3.68 years and 67% females) participated in this study. The results demonstrated that college belongingness partially mediated the association between coronavirus anxiety and psychological adjustment. The mediating part from coronavirus anxiety to college belongingness was moderated by social media addiction. In comparison with the high level of social media addiction, coronavirus anxiety had a stronger predictive effect on college belongingness under the low and moderate levels of social media addiction condition. Our findings highlight that college belongingness is a potential mechanism explaining how coronavirus anxiety is related to psychological adjustment and that this relation may depend on the levels of social media addiction.

Keywords: COVID-19, Coronavirus anxiety, College belongingness, Psychological adjustment, Social media addiction, Turkish undergraduate students

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has adversely affected the Turkish population which was subjected to unprecedented physical and social distancing measures since the emergence of pandemic in Turkey. To prevent the spread of COVID-19, the Turkish government on April 20, 2020 implemented a partial lockdown covering the largest 30 cities alongside some small cities with high rates of confirmed cases of COVID-19 (Yıldırım and Arslan 2020). The lockdown includes restriction of movements within and across the cities, and all Turkish were encouraged and even required to stay home and withdrawn from social interactions with friends and relatives outside their household for different reasons except for necessities and urgencies. In addition, the travel restriction in and out of these cities was forbidden (Yıldırım and Arslan 2020). All schools and universities had to remain closed until April 30, 2020, continuing with online education (Republic of Turkey Ministry of National Education 2020). As of December 2, 2020, Turkey registered over 513,656 confirmed cases of COVID-19 and 14,129 deaths (Republic of Turkey Ministry of Health 2020).

Coronavirus Pandemic and Psychological Adjustment

The COVID-19 pandemic is not only an epidemiologic crisis but also a health crisis by creating a wide range of psychological problems such as stress, anxiety, depression, trauma, panic, insomnia, death distress, anger, psychosis, boredom, and suicide (Ahorsu et al. 2020; American Psychological Association 2020; Burke and Arslan 2020; Liu et al. 2020; Yıldırım and Güler 2020). Examination of the impacts of COVID-19 pandemic on psychological health and well-being has been highly emphasized (Holmes et al. 2020). Anxiety related to the COVID-19 is one of the most commonly experienced distress during pandemic. Research suggest that people with high levels of coronavirus anxiety reported more coronavirus fear, functional impairment, worry about coronavirus, maladaptive religious coping, hopelessness, and suicidal ideation (Lee et al. 2020; Yıldırım et al. 2020).

A recent poll conducted in Germany asked people for symptoms of depression, anxiety, panic disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and lockdown-related behavior (Munk et al. 2020). The results showed that in this novel coronavirus pandemic, more than half of the participants (50.6%) are facing at least one mental disorder, which is much higher than the usual prevalence of mental disorders. Investigation of psychological responses during the early stage of the COVID-19 outbreak on the general population in China demonstrated that 53.8% of participants reported the psychological impact of the outbreak as moderate to severe, while 16.5% rated moderate to severe depressive symptoms, and 28.8% rated moderate to severe anxiety symptoms (Wang et al. 2020). Another large-scale study with over 50,000 people in China during the pandemic found that nearly 35% of the participants suffer from psychological distress (Qiu et al. 2020).

Psychological adjustment refers to one’s subjective sense of distress and the degree to which they function in daily life (Cruz et al. 2020; Peterson 2015). People with high levels of psychological adjustment tend to have a better ability to positively function in their daily lives (Yıldırım and Solmaz 2020). Research has shown that a higher positive psychological adjustment is associated with increased satisfaction with life and quality of life and decreased depression, anxiety, stress, and burnout (Bantjes and Kagee 2018; Chambers et al. 2017; Samios 2018; Yıldırım and Solmaz 2020). Given the profoundly high COVID-19 infection rate and relatively high mortality, people with higher coronavirus anxiety and stress may be at elevated risk for heightened psychological adjustment problems (Arslan et al. 2020b). Although limited, studies on previous pandemic have shown that coronavirus and SARS-related stressors have significant negative impacts on psychological adjustment (Arslan and Yıldırım 2021; August and Dapkewicz 2020; Main et al. 2011). In that study, active coping and seeking social support were significantly positively associated with fewer psychological symptoms, higher perceived general health, and greater satisfaction with life, while avoidant coping was significantly positively associated with negative adjustment. While there is evidence of a relationship between higher anxiety and lower psychological adjustment within wider psychology (Carver et al. 2020; Luo et al. 2012), there has been relatively little investigation on the impact of coronavirus anxiety on psychological adjustment in Turkish context throughout the current pandemic. As such, the purpose of this study was to examine the impact of coronavirus anxiety on psychological adjustment and to explore the mediating and moderating role of college belongingness and social media addiction during COVID-19 outbreak.

After temporary school closure for the pandemic, 1.4 billion students worldwide have been impacted (UNESCO 2020). That closure physically disconnected students from their friends and their wider social network and appears to have a severe impact on their psychological health. This could have affected the sense of belongingness of students. School belongingness is defined as “the extent to which students feel personally accepted, respected, included, and supported by others in the school social environment” (Goodenow and Grady 1993, p. 61). It includes how youth feels about themselves as being important, valuable, and meaningful parts of their schools (Arslan and Duru 2017). The need-to-belong theory describes belongingness as a basic motivational need that is extremely important for developing and maintaining intimate, positive, and long-lasting relations with others (Baumeister 2012; Baumeister and Leary 1995). Sense of belongingness within school context is related to a wide range of critical adolescent school-based and quality of life outcomes (Arslan 2018a; Arslan, Allen, & Traci; 2020; Osterman 2000). For example, research showed that belongingness was related to better academic functioning, self-regulatory performance, greater well-being, and lower mental health symptoms (Arslan 2018b; DeWall et al. 2008; King et al. 1996). There is some initial data in a new study with college students linking low belongingness with lower levels of adaptability to the pandemic (Besser et al. 2020).

College Belongingness and Social Media during the Pandemic

School is a productive environment where students can build a sense of belongingness. A fresh longitudinal cohort study in China indicated that the prevalence rates of mental health problems during the pandemic among students increased substantially when compared with those before the pandemic: depressive symptoms (24.9 vs 18.5%), non-suicidal self-injury (42.0 vs 31.8%), suicide ideation (29.7 vs 22.5%), suicide plan (14.6 vs 8.7%), and suicide attempt (6.4 vs 3.0%) (Zhang et al. 2020). This suggests that school is an important resource that supports youth mental health and well-being by giving the opportunities to improve a sense of belongingness. Therefore, separating students from school could have adverse effects on their sense of belongingness in school, which in turn leads to psychological adjustment problems. A sense of belongingness is also central to the school experience of college and university students, and deficits in belongingness are associated with poorer psychological adjustment (e.g., Ploskonka and Servaty-Seib 2015). There is some initial evidence linking a greater sense of belongingness on college students with better adaptability to the pandemic (see Besser et al. 2020). The current focus on levels of belongingness during the pandemic is in keeping with the potential usefulness of examining protective factors in specific situational contexts or circumstances and the heightened interpersonal sensitivities that are derived from the greater social isolation experienced during the pandemic (for related discussions, see Casale and Fle 2020; Flett and Zangeneh 2020).

Social media usage is more common among young people who use social media for various reasons such as expressing identity and connecting with others (Mahmood et al. 2018). Handy, cheaper, and convenient Internet facilities and smartphone ownership are among the other factors enabling youth population to use social networking sites (Poushter 2016). It is hard to estimate the rates of social media usage because of the use of different measurement tools and the scarcity of a consensual conceptualization of problematic social media use (Bányai et al. 2017). While some research indicated a prevalence rate of 2.8% of social media use among university students (Olowu and Seri 2012), others presented a prevalence rate of 47% social media use among young people (Al Mamun and Griffiths 2019).

The usage of social media in times of health crisis like the current pandemic can be profoundly high. The easiness to access information and sharing this information to others and senses of social cohesion and social connectedness attract people to stay connected in social media. A handful of studies can be found in the literature on the use of social media in the context of pandemic. In a study conducted with 4624 Turkish public during the early stages of the COVID-19, people reported high levels of usage of social media (M = 2.73, SD = .54) and internet journalism (M = 2.74, SD = .52) on a scale of 1 to 3, with higher scores indicating higher levels of engagement in respective sources of information (Geçer et al. 2020).

In the extant literature, there are many studies investigating the association between social media usage and mental health problems. Studies have largely indicated that the prolonged social media usage is positively related with negative mental health outcomes such as anxiety, depression, and stress and negatively related with well-being over time (Bányai et al. 2017; Błachnio et al. 2016; Shakya and Christakis 2017). In a study with Turkish college students, Facebook addiction was significantly positively associated with severe depression, anxiety, and insomnia (Koc and Gulyagci 2013). In another study, social media use was found to be associated with sense of belongingness, online self-representation, and social support. Moreover, online self-presentation had a mediation effect on the influence of social media use on sense of belongingness and social support (Pang 2020). Similarly, social media usage was found to moderate the associations between skills of distinguish emotional facial expressions and social anxiety of college students (Ermiş and Kantarcı 2016). Given that people tend to excessively use social media as a source of information which can be both positive and negative, it is plausible to assume that high and low social media usages have different effects on college belongingness which can in turn influence psychological adjustment.

The Present Study

Within the literature and theoretical framework sketched above, the present study proposed a moderated mediation model indicating that college belongingness mediated the relationship between coronavirus anxiety and psychological adjustment, and this mediation effect was moderated by social media addiction. Thus, we tested the following hypotheses (H1) to examine whether college belongingness mediated the associations between coronavirus anxiety and psychological adjustment and (H2) whether social media addiction moderated the mediating effect of college belongingness on the association between coronavirus anxiety and psychological adjustment, as shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

The proposed model indicating the association between the variables of the study

Method

Participants

The sample of the present study is composed of 315 undergraduate students attending a state university in an urban city of Turkey. Participants were primarily females (67%) and ranged in age between 18 and 39 years (Mean = 21.65, SD = 3.68 years). The sample included 37.8% first-year students, 26% second-year students, 16% third-year students, and 20% fourth-year students. Concerning the coronavirus characteristics, the majority of participants identified themselves as non-infected (87.9%). The administration of the study was done online. All participants were informed of their rights to opt out of the study at any time. Participation was voluntary and anonymous, and participants could withdrawal from the study at any time.

Measures

Coronavirus Anxiety

Coronavirus anxiety was assessed using the Coronavirus Anxiety Scale (CAS; Lee 2020), which is a 5-item self-report measure (e.g., “I felt dizzy, lightheaded, or faint, when I read or listened to news about the coronavirus”). The scale’s items are scored based on 5-point Likert-type scale, ranging from 0 = “not at all” to 4 = “nearly every day over the last 2 weeks” (Lee 2020). Arslan et al. (2020a) examined the psychometric properties of the CAS, indicating that the scale had a strong internal reliability estimate with Turkish university students. The internal reliability estimate of CAS with the present sample was strong, as seen in Table 1.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics and correlation results

| Variables | Mean | SD | Skewness | Kurtosis | α | 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Coronavirus anxiety | 2.51 | 3.85 | 1.82 | 2.81 | .91 | — | −.21** | .09 | .24** |

| 2. College belongingness | 51.93 | 10.45 | −.64 | .23 | .82 | — | −.05 | −.22** | |

| 3. Social media addiction | 16.35 | 6.21 | .19 | −.73 | .83 | — | −.29** | ||

| 4. Psychological adjustment | 21.54 | 10.28 | .26 | −.99 | .93 | — | |||

Note. **p < .001

College Belongingness

College belongingness was measured using the College Belongingness Questionnaire (CBQ; Arslan 2020a, b), which is a 10-item self-report measure (e.g., “I feel like I belong at this university”) developed to assess the feelings of belongingness of Turkish university students. All items of the measure are scored using a 7-point Likert-type scale, ranging between 1= “strongly disagree” and 7 = “strongly agree.” After reversing five social exclusion items, total sense of belongingness scores are provided by summing item responses. Results from the previous research indicated that the scale provided a strong internal reliability estimate with Turkish university students. The internal reliability estimate of CBQ in the present study was strong, as seen in Table 1.

Social Media Addiction

Social media addiction was measured using the Bergen Social Media Addiction Scale (BSMAS; Andreassen et al. 2016). The scale includes six items rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1= “very rarely” to 5 = “very often.” A sample item is “How often during the last year have you tried to cut down on the use of social media without success?” A higher score on the BSMAS refers to stronger addiction to social media. Psychometric analyses of the BSMAS in Turkish were performed by Demirci (2019) who demonstrated good evidence of reliability and validity. The internal reliability estimate of BSMAS in this study was strong, as presented in Table 1.

Psychological Adjustment

Students’ psychological adjustment was measured using the Brief Adjustment Scale-6 (BASE; Cruz et al. 2020), which is a 6-item self-report scale (e.g., “To what extent have you felt irritable, angry, and/or resentful this week?”) developed to assess psychological adjustment challenges of people. All items of the scale are scored based on a 7-point scale ranging from 1 = “not at all” to 7 = “extremely.” Higher scores are evaluated as a greater level of psychological maladjustment (Cruz et al. 2020). Yıldırım and Solmaz (2020) investigated the psychometric properties of the BASE for Turkish sample, revealing that the scale had strong internal reliability estimates. The internal reliability estimate of BASE with the present sample was strong, as shown in Table 1.

Statistical Analyses

We performed a two-step analytic approach to examine the proposed model. Observed scale characteristics and correlation analysis were first conducted to explore descriptive statistics, the assumptions of analysis, and the associations between the study variables. Normality was interpreted using skewness and kurtosis scores and their cutoff points (D’Agostino et al. 1990; Kline 2015). Following the review of the observed scale characteristics and correlations, we then carried out a moderated mediation model using the PROCESS macro version 3.5 (Model 7; see Fig. 1) for SPSS (Hayes 2018). Moderated mediation is a statistical approach conducted to test conditional indirect effects, and moderation and mediation analyses are employed together in a single model (Preacher et al. 2007). Moreover, the bootstrap approach with 10,000 resamples to estimate the 95% confidence intervals was conducted for interpreting the significance of indirect effects (Hayes 2018; Preacher and Hayes 2008). All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 25.

Results

Observed Scale Characteristics

Findings from observed scale characteristics indicated that kurtosis scores were between −.99 and 2.81, and skewness values ranged from −.64 to 1.82, indicating that all measures had relatively normal distribution (D’Agostino et al. 1990; Kline 2015), as shown in Table 1. Further, correlation results revealed that coronavirus anxiety had significant correlations with college belongingness, and psychological adjustment had a non-significant association with social media addiction. College belongingness was also significantly correlated with psychological adjustment. The correlation between college belongingness and social media addiction was not significant. Social media addiction had a significant correlation with psychological adjustment, as seen in Table 1.

Conditional Process Analysis

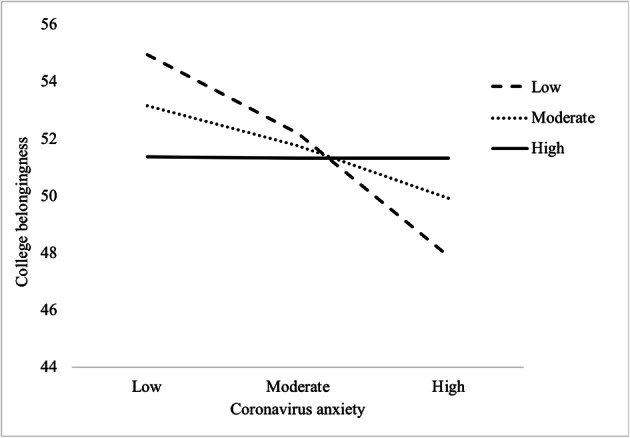

We next examined the mediating role of college belongingness on the relationship between coronavirus anxiety and psychological adjustment challenges and tested the moderating effect of social media addiction on the mediating role of college belongingness in this association using conditional process analysis (Model 7; see Fig. 1). Findings from this analysis showed that coronavirus anxiety was a significant predictor of college belongingness and psychological adjustment challenges. Social media addiction did not significantly predict college belongingness. Further, the interaction between coronavirus anxiety and social media addition was significant, accounting for 5% variance in the association between coronavirus anxiety and college belongingness, as seen in Table 2. Social media addiction moderated this association, and the indirect effect of coronavirus anxiety on psychological adjustment challenges through college belongingness was observed when social media addiction was low (−1 SD) and moderate when social media addiction was not high (+1 SD), as shown in Fig. 2. Lastly, college belongingness had a significant predictive effect on college students’ psychological adjustment and mediated the effect of coronavirus anxiety on psychological adjustment of college students.

Table 2.

Unstandardized coefficients for the conditional process model

| Antecedent | Consequent | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M (college belongingness) | ||||

| Coeff. | SE | t | p | |

| X (coronavirus anxiety) | −.55 | .15 | −3.67 | <.001 |

| W (social media addiction) | −.07 | .09 | −.72 | .471 |

| X×W | .09 | .02 | 3.81 | <.001 |

| Constant | 51.74 | .58 | 90.22 | <.001 |

| R2 = .09; R2 change = .05; F = 9.51; p < .001 | ||||

| Y (psychological adjustment) | ||||

| X (coronavirus anxiety) | .53 | .15 | 3.52 | <.001 |

| M (college belongingness) | −.17 | .06 | −3.14 | <.001 |

| Constant | 30.71 | 2.93 | 10.50 | <.001 |

| R2 = .09; F = 13.99; p < .001 | ||||

| Conditional indirect effects of coronavirus anxiety on psychological adjustment challenge | ||||

| College belongingness | Coeff. | BootSE | BootLLCI | BootULCI |

| M − 1SD (−.6.23) | .19 | .08 | .05 | .37 |

| M (.00) | .10 | .04 | .02 | .19 |

| M + 1SD (6.23) | .00 | .04 | .09 | .07 |

| Index of moderated mediation | ||||

| College belongingness | −.02 | .01 | −.03 | −.01 |

SE standard error, Coeff unstandardized coefficient, X independent variable, M mediator variable, W moderator variable, Y outcomes or dependent variable

Fig. 2.

Moderating effect of social media addiction

Discussion

The present study developed a moderated mediation model to investigate the mediation effect of college belongingness in the relationship between coronavirus anxiety and psychological adjustment and the moderating role of social media addiction in the association between coronavirus anxiety and college belongingness. The results mainly supported our research hypotheses. Findings from this study suggest that coronavirus anxiety significantly predicts college belongingness and psychological adjustment. Higher experience of coronavirus anxiety was associated with lower college belongingness and higher psychological adjustment problems. This suggests that college students who experience coronavirus anxiety are more likely to have poor school belongingness and difficulties with psychological adjustment compared with those who are not occupied with coronavirus anxiety. The results of this study are consistent with previous research demonstrating links between anxiety, college belongingness, and mental health outcomes. In a study conducted with college students, higher perceived stress was associated with lower satisfaction with life under the condition of low college belongingness (Çivitci 2015). Sense of belongingness was also associated with depression, interpersonal conflicts, and loneliness (Hagerty and Williams 1999) and social and academic adjustment (Arslan and Coşkun 2020; Ostrove and Long 2007) among college students. Previous studies also indicated elevated levels of mental health problems during the COVID-19 outbreak. For example, a study conducted in China with nearly 18,000 participants before and after the COVID-19 found that during the pandemic, negative emotions such as anxiety, depression, and anger increased, whereas positive emotions and life satisfaction decreased (Li et al. 2020).

The associations between college belongingness and psychological adjustment was also found in this study. Students with higher levels of college belongingness tend to have better adaptive psychological adjustment within school settings. Previous studies have demonstrated that college belongingness was positively associated with happiness and subjective well-being (McAdams and Bryant 1987) and negatively correlated with social exclusion and anxiety (Baumeister and Tice 1990) as well as depression, loneliness, and social anxiety (Leary 1990; Stebleton et al. 2014; Raymond and Sheppard 2018). This study employed college belongingness as an important mediator variable in the relationship between coronavirus stress and psychological adjustment. Consistent with our assumptions, the results of simple mediation model revealed that college belongingness partially mediated the relationship between coronavirus anxiety and psychological adjustment. This suggests that individuals who have low levels of coronavirus anxiety experience a greater sense of college belongingness, which in turn enhances psychological adjustment. Support for this explanation can be found in previous studies which showed that belongingness was an important mediator in explaining the relationship between school-related factors or other psychological variables (e.g., attachment insecurity) and mental health outcomes like depression and life satisfaction (Ahmadi and Ahmadi 2020; Venta et al. 2014). COVID-19-related stressors and associated lockdowns have significant adverse impacts on mental health outcomes. As presented in this study, college belongingness may be particularly salient in the process underlying psychological adjustment of students with coronavirus anxiety. The implications of these findings are important, highlighting the role of college belongingness involved in students with coronavirus anxiety and pointing to potentially modifiable mechanisms.

Moreover, the current study provided evidence regarding the moderating role of social media addiction within the mediated path. Results from this study showed that the indirect effect of coronavirus anxiety on psychological adjustment via college belongingness only occurred when social media addiction was low and moderate. Unsurprisingly, the moderating effect of social media addiction did not occur when it was high. When they are highly engaged in social media, they may find an opportunity to meet their sense of belongingness with their peers in the virtual environment. These findings partially appear to contradict with previous examinations that students who highly engage in social media sites have poor academic performance in schools (Paul et al. 2012). This variation may be due to the notion that the college student may be aware of the negative impact of coronavirus anxiety on their senses of college belongingness when the intensity of using social media is limited.

Implications and Limitations

The findings are important in terms of providing evidence that focus on prevention and intervention programs aimed at increasing students’ sense of belongingness and psychological adjustment. Examination of key mediating and moderating mechanisms offer infights into potential intervention opportunities, which may be most beneficial in dealing with young adults at high risk of coronavirus. This study suggests that college belongingness may be a fundamental modifiable mechanism in order to prevent and to mitigate psychological adjustment problems in college students. For example, recent research suggests that school-based effective prevention and intervention programs in reducing social media addiction can promote positive mental health (including both emotional well-being and social functioning) in school context (Throuvala et al. 2019). Our findings suggest that working with young adults with high coronavirus anxiety may include the need for prudent assessment of college belongingness and levels of social media addiction to support the development of psychological adjustment. Therefore, considering the adverse mental health impacts of COVID-19 and associated lockdowns on psychosocial adjustment, it is indispensable that effectual public health interventions in school context are designed to support college belongingness and promote psychological adjustment during and after the COVID-19 health crisis. Next, the results indicate that social media addiction moderates the association between coronavirus anxiety and college belongingness, which in turn influences student psychological adjustment. Decreasing social media addictive behavior could facilitate college students to deal with coronavirus anxiety and promote their feelings of belongingness, which in turn would improve their adaptive psychological adjustment. Given this effect, intervention strategies for social media addiction can be more effective if they focus on both the behavior and the risk factors (Arslan 2017), such as coronavirus anxiety. Cognitive-behavioral techniques could be useful for decreasing addictive behavior to social media. These strategies may contribute to modifying student thoughts, beliefs, and perceptions that can cause social media addiction (Arslan 2020a, b). Collectively, the findings from the present research demonstrate the complex interlink between risk and protective factors in college students’ psychological adjustment and underscore the need for complex research design and methodology to better understand and promote optimal psychological health.

Limitations of the current study should be acknowledged. First, we did not collect any information about when the participants started to use the social media, and this might affect the associations between the coronavirus anxiety, college belongingness, and psychological adjustment. Second, only Turkish undergraduate students were included, in a relatively small sample size, which could influence sample generalizability of the findings. A large sample of individuals from different countries, cultural backgrounds, and in different ages would be more useful to address the sample representativeness. Third, this study used the self-report method. Utilizing peer, parent, or teacher reports to evaluate the associations between the study variables would be useful to enhance the reliability, validity, and effectiveness of the findings of this study. Finally, we only adopted college belongingness as a mediator and social media addiction as a moderator. However, there might be other possible mediators, moderators, and relation models.

In conclusion, the results from the current study demonstrated that college belongingness mediated decreases in the negative impacts of coronavirus anxiety on psychological adjustment, while social media addiction moderated the association between the coronavirus anxiety and college belongingness. Generally speaking, the combinations of these two main findings mitigated the detrimental impacts of coronavirus anxiety on psychological adjustment during the emergence of COVID-19 among college students in Turkey.

Compliance with ethical standards

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Consent was obtained from all participants included in the study.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Ahmadi F, Ahmadi S. School-related predictors of students’ life satisfaction: The mediating role of school belongingness. Contemporary School Psychology. 2020;24(2):196–205. doi: 10.1007/s40688-019-00262-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ahorsu, D. K., Lin, C. Y., Imani, V., Saffari, M., Griffiths, M. D., & Pakpour, A. H. (2020). The fear of COVID-19 scale: Development and initial validation. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction.10.1007/s11469-020-00270-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Al Mamun MA, Griffiths MD. The association between Facebook addiction and depression: A pilot survey study among Bangladeshi students. Psychiatry Research. 2019;271:628–633. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2018.12.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychological Association. (2020). Psychological impact of COVID-19. https://www.apa.org/topics/covid-19/psychological-impact

- Andreassen CS, Billieux J, Griffiths MD, Kuss DJ, Demetrovics Z, Mazzoni E, Pallesen S. The relationship between addictive use of social media and videogames and symptoms of psychiatric disorder: A large-scale cross-sectional study. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2016;30(2):252–262. doi: 10.1037/adb0000160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arslan G. Psychological maltreatment, forgiveness, mindfulness, and internet addiction among young adults: A study of mediation effect. Computers in Human Behavior. 2017;72:57–66. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2017.02.037. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arslan G. Exploring the association between school belonging and emotional health among adolescents. International Journal of Educational Psychology. 2018;7(1):21–41. doi: 10.17583/ijep.2018.3117. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arslan, G. (2018b). Psychological maltreatment, social acceptance, social connectedness, and subjective well-being in adolescents. Journal of Happiness Studies, 19(4), 983–1001. 10.1007/s10902-017-9856-z

- Arslan, G. (2020a). School belongingness, well-being, and mental health among adolescents: Exploring the role of loneliness. Australian Journal of Psychology.10.1111/ajpy.12274.

- Arslan G. Journal of Positive School Psychology. 2020. Loneliness, college belongingness, subjective vitality, and psychological adjustment during coronavirus pandemic: Development of the College Belongingness Questionnaire. [Google Scholar]

- Arslan G, Coşkun M. Student subjective wellbeing, school functioning, and psychological adjustment in high school adolescents: A latent variable analysis. Journal of Positive School Psychology. 2020;4(2):153–164. doi: 10.47602/jpsp.v4i2.231. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arslan G, Duru E. Initial development and validation of the School Belongingness Scale. Child Indicators Research. 2017;10(4):1043–1058. doi: 10.1007/s12187-016-9414-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arslan, G., & Yıldırım, M. (2021). Coronavirus stress, meaningful living, optimism, and depressive symptoms: A study of moderated mediation model. Australian Journal of Psychology (in press).

- Arslan, G., Yıldırım, M., & Aytaç, M. (2020a). Subjective vitality and loneliness explain how coronavirus anxiety increases rumination among college students. Death Studies., 1–10. 10.1080/07481187.2020.1824204. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Arslan, G., Yıldırım, M., Tanhan, A., Bulus, M., & Allen, K. (2020b). Coronavirus stress, optimism-pessimism, psychological inflexibility, and psychological health: Psychometric properties of the Coronavirus Stress Measure. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction.10.1007/s11469-020-00337-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- August, R., & Dapkewicz, A. (2020). Benefit finding in the COVID-19 pandemic: College students’ positive coping strategies. Journal of Positive School Psychology, 1–14 Retrieved from https://journalppw.com/index.php/JPPW/article/view/245.

- Bantjes J, Kagee A. Common mental disorders and psychological adjustment among individuals seeking HIV testing: A study protocol to explore implications for mental health care systems. International Journal of Mental Health Systems. 2018;12(1):16. doi: 10.1186/s13033-018-0196-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bányai F, Zsila Á, Király O, Maraz A, Elekes Z, Griffiths MD, Andreassen CS, Demetrovics Z. Problematic social media use: Results from a large-scale nationally representative adolescent sample. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0169839. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0169839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister, R. F. (2012). Need-to-belong theory. In P. A. M., van Lange, A. W. Kruglanski, & E. T. Higgins (Eds.), Handbook of theories of social psychology (Vol. 2, pp. 121–140). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications Ltd.

- Baumeister RF, Leary MR. The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin. 1995;117(3):497–529. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.117.3.497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister RF, Tice DM. Point-counterpoints: Anxiety and social exclusion. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 1990;9(2):165–195. doi: 10.1521/jscp.1990.9.2.165. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Besser, A., Flett, G. L., & Zeigler-Hill, V. (2020). Adaptability to a sudden transition to online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic: Understanding the challenges for students. Scholarship of Teaching and Learning in Psychology.10.1037/stl0000198.

- Błachnio A, Przepiorka A, Pantic I. Association between Facebook addiction, self-esteem and life satisfaction: A cross-sectional study. Computers in Human Behavior. 2016;55:701–705. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2015.10.026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Burke J, Arslan G. Positive education and school psychology during COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Positive School Psychology. 2020;4(2):137–139. doi: 10.47602/jpsp.v4i2.243. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carver, K., Ismail, H., Reed, C., Hayes, J., Alsaif, H., Villanueva, M., & Sass, S. (2020). High levels of anxiety and psychological well-being in college students: A dual factor model of mental health approach. Journal of Positive School Psychology. Retrieved from https://journalppw.com/index.php/JPPW/article/view/242

- Casale S, Fle GL. Interpersonally based fears during the COVID-19 pandemic: Reflections on the fear of missing out and the fear of not mattering constructs. Clinical Neuropsychiatry. 2020;17(2):88–93. doi: 10.36131/CN20200211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambers SK, Ng SK, Baade P, Aitken JF, Hyde MK, Wittert G, Frydenberg M, Dunn J. Trajectories of quality of life, life satisfaction, and psychological adjustment after prostate cancer. Psycho-Oncology. 2017;26(10):1576–1585. doi: 10.1002/pon.4342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Çivitci A. Perceived stress and life satisfaction in college students: Belonging and extracurricular participation as moderators. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences. 2015;205:271–281. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.09.077. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cruz RA, Peterson AP, Fagan C, Black W, Cooper L. Evaluation of the Brief Adjustment Scale–6 (BASE-6): A measure of general psychological adjustment for measurement-based care. Psychological Services. 2020;17(3):332–342. doi: 10.1037/ser0000366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Agostino RB, Belanger A, D’Agostino RB. A Suggestion for using powerful and informative tests of Normality. The American Statistician. 1990;44(4):316. doi: 10.2307/2684359. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Demirci İ. Bergen Sosyal Medya Bağımlılığı Ölçeğinin Türkçeye uyarlanması, depresyon ve anksiyete belirtileriyle ilişkisinin değerlendirilmesi. Anatolian Journal of Psychiatry/Anadolu Psikiyatri Dergisi. 2019;20:15–22. [Google Scholar]

- DeWall CN, Baumeister RF, Vohs KD. Satiated with belongingness? Effects of acceptance, rejection, and task framing on self-regulatory performance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2008;95(6):1367–1382. doi: 10.1037/a0012632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ermiş EN, Kantarcı S. Investigation effect of moderator role of using social media and social communication between skills of recognition and distinguish emotional facial expressions and social anxiety in relationship. International Journal of Social Sciences and Education Research. 2016;2(2):583–591. doi: 10.24289/ijsser.279069. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Flett GL, Zangeneh M. Mattering as a vital support for people during the COVID-19 pandemic: The benefits of feeling and knowing that someone cares during times of crisis. Journal of Concurrent Disorders. 2020;2(1):106–123. [Google Scholar]

- Geçer, E., Yıldırım, M., & Akgül, Ö. (2020). Sources of information in times of health crisis: Evidence from Turkey during COVID-19. Journal of Public Health. 10-7 10.1007/s10389-020-01393-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Goodenow C, Grady KE. The relationship of school belonging and friends’ values to academic motivation among urban adolescent students. The Journal of Experimental Education. 1993;62(1):60–71. doi: 10.1080/00220973.1993.9943831. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hagerty BM, Williams A. The effects of sense of belonging, social support, conflict, and loneliness on depression. Nursing Research. 1999;48(4):215–219. doi: 10.1097/00006199-199907000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A. F. (2018). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. Guilford Press.

- Holmes EA, O’Connor RC, Perry VH, Tracey I, Wessely S, Arseneault L, et al. Multidisciplinary research priorities for the COVID-19 pandemic: A call for action for mental health science. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7:547–560. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30168-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King CA, Akiyama MM, Elling KA. Self-perceived competencies and depression among middle school students in Japan and the United States. The Journal of Early Adolescence. 1996;16(2):192–210. doi: 10.1177/0272431696016002004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kline RB. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Koc M, Gulyagci S. Facebook addiction among Turkish college students: The role of psychological health, demographic, and usage characteristics. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking. 2013;16:279–284. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2012.0249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leary MR. Responses to social exclusion: Social anxiety, jealousy, loneliness, depression, and low self-esteem. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 1990;9(2):221–229. doi: 10.1521/jscp.1990.9.2.221. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SA. Coronavirus Anxiety Scale: A brief mental health screener for COVID-19 related anxiety. Death Studies. 2020;44:393–401. doi: 10.1080/07481187.2020.1748481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S. A., Mathis, A. A., Jobe, M. C., & Pappalardo, E. A. (2020). Clinically significant fear and anxiety of COVID-19: A psychometric examination of the Coronavirus Anxiety Scale. Psychiatry Research, 113112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Li S, Wang Y, Xue J, Zhao N, Zhu T. The impact of COVID-19 epidemic declaration on psychological consequences: A study on active Weibo users. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020;17(6):2032. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17062032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, N., Zhang, F., Wei, C., Jia, Y., Shang, Z., Sun, L., et al. (2020). Prevalence and predictors of PTSS during COVID-19 outbreak in China hardest-hit areas: Gender differences matter. Psychiatry Research, 112921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Luo QY, Lv RY, Zhu FY. The anxiety and psychological adjustment of female assistant nurses under modern medical situation. China Practical Medicine. 2012;2012(28):204. [Google Scholar]

- Mahmood QK, Zakar R, Zakar MZ. Role of Facebook use in predicting bridging and bonding social capital of Pakistani university students. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment. 2018;28(7):856–873. doi: 10.1080/10911359.2018.1466750. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Main A, Zhou Q, Ma Y, Luecken LJ, Liu X. Relations of SARS-related stressors and coping to Chinese college students’ psychological adjustment during the 2003 Beijing SARS epidemic. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2011;58(3):410–423. doi: 10.1037/a0023632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAdams DP, Bryant FB. Intimacy motivation and subjective mental health in a nationwide sample. Journal of Personality. 1987;55(3):395–413. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.1987.tb00444.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munk AJ, Schmidt NM, Alexander N, Henkel K, Hennig J. Covid-19—Beyond virology: Potentials for maintaining mental health during lockdown. Plos One. 2020;15(8):e0236688. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0236688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olowu AO, Seri FO. A study of social network addiction among youths in Nigeria. Journal of Social Science and Policy Review. 2012;4(1):63–71. [Google Scholar]

- Osterman KF. Students’ need for belonging in the school community. Review of Educational Research. 2000;70(3):323–367. doi: 10.3102/00346543070003323. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ostrove JM, Long SM. Social class and belonging: Implications for college adjustment. Review of Higher Education. 2007;30(4):363–389. doi: 10.1353/rhe.2007.0028. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pang H. Examining associations between university students’ mobile social media use, online self-presentation, social support and sense of belonging. Aslib Journal of Information Management. 2020;72(3):321–338. doi: 10.1108/AJIM-08-2019-0202. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Paul JA, Baker HM, Cochran JD. Effect of online social networking on student academic performance. Computers in Human Behavior. 2012;28(6):2117–2127. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2012.06.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson AP. Psychometric Evaluation of the Brief Adjustment Scale-6 (BASE-6): A New Measure of General Psychological Adjustment (Master dissertation) Washington, USA: University of Washington; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ploskonka RA, Servaty-Seib HL. Belongingness and suicidal ideation in college students. Journal of American College Health. 2015;63(2):81–87. doi: 10.1080/07448481.2014.983928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poushter J. Smartphone ownership and Internet usage continues to climb in emerging economies. Pew Research Center. 2016;22(1):1–44. [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods. 2008;40(3):879–891. doi: 10.3758/BRM.40.3.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Rucker DD, Hayes AF. Addressing moderated mediation hypotheses: Theory, methods, and prescriptions. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 2007;42:185–227. doi: 10.1080/00273170701341316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu J, Shen B, Zhao M, Wang Z, Xie B, Xu Y. A nationwide survey of psychological distress among Chinese people in the COVID-19 epidemic: implications and policy recommendations. General Psychiatry. 2020;33(2):e100213. doi: 10.1136/gpsych-2020-100213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raymond JM, Sheppard K. Effects of peer mentoring on nursing students’ perceived stress, sense of belonging, self-efficacy and loneliness. Journal of Nursing Education and Practice. 2018;8(1):16–23. doi: 10.5430/jnep.v8n1p16. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Republic of Turkey Ministry of Health. (2020). Daily coronavirus table of Turkey. Retrieved from https://covid19.saglik.gov.tr/

- Republic of Turkey Ministry of National Education. (2020). Uzaktan Eğitim 30 Nisan’a Kadar Devam Edecek. Available online at: http://www.meb.gov.tr/uzaktan-egitim-30-nisana-kadar-devam-edecek/haber/20585/tr

- Samios C. Burnout and psychological adjustment in mental health workers in rural Australia: The roles of mindfulness and compassion satisfaction. Mindfulness. 2018;9(4):1088–1099. doi: 10.1007/s12671-017-0844-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shakya HB, Christakis NA. Association of Facebook use with compromised well-being: A longitudinal study. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2017;185:203–211. doi: 10.1093/aje/kww189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stebleton MJ, Soria KM, Huesman RL., Jr First-generation students’ sense of belonging, mental health, and use of counseling services at public research universities. Journal of College Counseling. 2014;17(1):6–20. doi: 10.1002/j.2161-1882.2014.00044.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Throuvala MA, Griffiths MD, Rennoldson M, Kuss DJ. School-based prevention for adolescent Internet addiction: Prevention is the key. A systematic literature review. Current Neuropharmacology. 2019;17(6):507–525. doi: 10.2174/1570159X16666180813153806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. (2020). COVID-19 educational disruption and response. Available at https://en.unesco.org/news/covid-19-educational-disruption-and-response

- Venta A, Mellick W, Schatte D, Sharp C. Preliminary evidence that thoughts of thwarted belongingness mediate the relations between level of attachment insecurity and depression and suicide-related thoughts in inpatient adolescents. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 2014;33(5):428–447. doi: 10.1521/jscp.2014.33.5.428. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C, Pan R, Wan X, Tan Y, Xu L, Ho CS, Ho RC. Immediate psychological responses and associated factors during the initial stage of the 2019 coronavirus disease (COVID-19) epidemic among the general population in China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020;17(5):1729. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17051729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yıldırım, M., & Arslan, G. (2020). Exploring the associations between resilience, dispositional hope, subjective well-being, and psychological health among adults during the early stage of COVID-19. Current Psychology. 10.1007/s12144-020-01177-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Yıldırım M, Güler A. Positivity explains how COVID-19 perceived risk increases death distress and reduces happiness. Personality and Individual Differences. 2020;168:110347. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2020.110347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yıldırım, M. & Solmaz, F. (2020). Testing a Turkish adaption of the Brief Psychological Adjustment Scale and assessing the relation to mental health. Psikoloji Çalışmaları, 10.13140/RG.2.2.18574.59205.

- Yıldırım, M., Arslan, G., & Özaslan, A. (2020). Perceived risk and mental health problems among healthcare professionals during COVID-19 pandemic: Exploring the mediating effects of resilience and coronavirus fear. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction.10.1007/s11469-020-00424-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Zhang L, Zhang D, Fang J, Wan Y, Tao F, Sun Y. Assessment of mental health of Chinese primary school students before and after school closing and opening during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Network Open. 2020;3(9):e2021482–e2021482. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.21482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]