Abstract

Resistant starch (RS) is fermentable by gut microbiota and effectively modulates fecal short-chain fatty acid concentrations in pigs, mice, and humans. RS may have similar beneficial effects on the canine gut but has not been well studied. The objective of this study was to evaluate the effects of 0%, 1%, 2%, 3%, and 4% dietary RS (Hi-maize 260) on apparent total tract macronutrient digestibility, fecal characteristics, fermentative end-product concentrations, and microbiota of healthy adult dogs. An incomplete 5 × 5 Latin square design with seven dogs and five experimental periods was used, with each treatment period lasting 21 d (days 0 to 17 adaptation; days 18 to 21 fresh and total fecal collection) and each dog serving as its own control. Seven dogs (mean age = 5.3 yr; mean body weight = 20 kg) were randomly allotted to one of five treatments formulated to be iso-energetic and consisting of graded amounts of 100% amylopectin cornstarch, RS, and cellulose and fed as a top dressing on the food each day. All dogs were fed the same amount of a basal diet throughout the study, and fresh water was offered ad libitum. The basal diet contained 6.25% RS (dry matter [DM] basis), contributing approximately 18.3 g of RS/d based on their daily food intake (292.5 g DM/d). Data were evaluated for linear and quadratic effects using SAS. The treatments included 0%, 1%, 2%, 3%, and 4% of an additional RS source. Because Hi-maize 260 is approximately 40% digestible and 60% indigestible starch, the dogs received the following amounts of RS daily: 0% = 18.3 g (18.3 + 0 g), 1% = 20.1 g (18.3 + 1.8 g), 2% = 21.9 g (18.3 + 3.6 g), 3% = 23.7 g (18.3 + 5.4 g), and 4% = 25.5 g (18.3 + 7.2 g). Apparent total tract DM, organic matter, crude protein, fat, and gross energy digestibilities and fecal pH were linearly decreased (P < 0.05) with increased RS consumption. Fecal output was linearly increased (P < 0.05) with increased RS consumption. Fecal scores and fecal fermentative end-product concentrations were not affected by RS consumption. Although most of the fecal microbial taxa were not altered, Faecalibacterium were increased (P < 0.05) with increased RS consumption. The decrease in fecal pH and increase in fecal Faecalibacterium would be viewed as being beneficial to gastrointestinal health. Although our results seem to indicate that RS is poorly and/or slowly fermentable in dogs, the lack of observed change may have been due to the rather high level of RS contained in the basal diet.

Keywords: canine, gut health, gut microbiota

Introduction

Many of today’s dry extruded diets contain 20% to 50% carbohydrates (Bradshaw, 2006), with the majority in the form of digestible starch. Starch molecules are polysaccharides composed of glucose units linked by α-1,4 and α-1,6 glycosidic bonds. Amylose, a linear polymer of α-1,4 glycosidic linkages, and amylopectin, a much larger polymer composed of α-1,4 and α-1,6 glycosidic linkages, are the two primary forms of starch. Starches may be classified into rapidly digestible starch, slowly digestible starch, or resistant starch (RS). Rapidly and slowly digestible starches are completely digested in the small intestine but at varying rates (Englyst et al., 1992; Sajilata et al., 2006; Zhang and Hamaker, 2009). By definition, RS is starch that escapes digestion in the small intestine and ends up in the large bowel, part of which may be fermented in the colon (Sajilata et al., 2006). Four RS forms exist, including those made up of physically entrapped starches (RS1), raw starch granules having a crystal structure resistant to digestive enzymes (RS2), retrograded starches formed from repeated cooking and cooling (RS3), and chemically modified starches (RS4) (Englyst et al., 1992).

Dietary components that escape small intestinal digestion may serve as a substrate for microbial fermentation in the large intestine, potentially impacting gastrointestinal (GI) health. Dietary inclusion of RS, fibers, and prebiotics has been a consistent area of interest in the pet food industry. Dietary fibers and prebiotics have been studied most frequently, with previous research in dogs being focused on a few key indices of GI health. These dietary components often lead to reduced fecal pH and concentrations of putrefactive compounds, increased concentrations of fecal short-chain fatty acids (SCFA; acetate, propionate, and butyrate), and alterations in gut bacterial populations. Dietary fibers and prebiotics often increase the concentrations of beneficial or commensal bacteria and decrease the concentrations of potentially pathogenic bacteria, leading to improved GI health (Vickers et al., 2001; Swanson et al., 2002; Flickinger et al., 2003; Propst et al., 2003; Zentek et al., 2003; Grieshop et al., 2004; Middelbos et al., 2007a, 2007b; Beloshapka et al., 2012, 2013). RS may provide similar beneficial effects on the canine gut, but a specific dose of RS that is effective in manipulating fecal microbial populations and fermentative end products, but does not negatively affect stool quality, has yet to be determined.

Hi-maize 260 (Ingredion; Bridgewater, NJ, USA) is a source of RS isolated from high-amylose corn hybrids and processed to be approximately 60% RS and 40% digestible starch. It is a low-calorie (~2.8 kcal/g), low-glycemic index product that may be substituted in place of flour into a variety of foods, including baked goods, pasta, snack foods, cereals, and nutrition bars. Because it is a relatively pure source of digestible starch and RS, it allows for accurate doses to be tested. Therefore, the objective of this study was to evaluate the effects of 0%, 1%, 2%, 3%, and 4% Hi-maize 260 on apparent total tract macronutrient digestibility, fecal characteristics, microbial populations, and fermentative end-product concentrations in healthy adult dogs. We hypothesized that increased RS consumption would increase fecal SCFA concentrations and reduce protein fermentation products. We also hypothesized that increased RS would beneficially alter fecal microbiota populations, including increases in Ruminococcus, Parabacteroides, and Faecalibacterium, taxa that have been shown to degrade RS or be altered by RS consumption in humans previously (Martínez et al., 2010; Walker et al., 2011; Ze et al., 2012).

Materials and Methods

Animals and diets

All animal care and study procedures were approved by the University of Illinois Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee prior to experimentation. A total of seven healthy intact adult female hound-cross dogs (average age: 5.3 yr; average body weight: 20 to 25 kg) were studied. Dogs were housed individually in runs (2.4 × 1.2 m), which allowed for the nose–nose contact between dogs in adjacent runs and visual contact with all dogs in the room, in two temperature-controlled rooms (22 °C; 23% relative humidity) with 12:12 (L:D) h cycles. Although animals were housed and fed individually, they were allowed to exercise and play outside of their cages together (and with people and toy enrichment) within the animal room for several hours at least three times a week. The exception was during the total fecal collection phase of each period when dogs remained in their runs so that all samples from each dog could be collected without the risk of cross contamination. Dogs were weighed and assessed for body condition score (9-point scale) prior to the morning feeding on every Thursday of the study.

One experimental diet was formulated with low-ash poultry byproduct meal, brewer’s rice, and poultry fat constituting the main ingredients of the dry, extruded kibble diet (Table 1). All dogs were fed the same experimental diet formulated to meet their nutritional requirements as provided by the Association of American Feed Control Officials (AAFCO, 2012) but to contain little residual fiber to ensure that the effects of RS were not masked or biased by fiber in the diet. Diets were formulated by Lortscher Animal Nutrition, Inc. (Bern, KS, USA) and extruded by AFB International (St. Charles, MO, USA). All dogs were fed the same amount of diet (300 g total) once daily (0800 hours). To ensure the dogs consumed all of their dietary treatment, the starch blend was mixed with 50 mL of water and 30 g of their daily ration and offered prior to their daily meal. No refusal or regurgitation of treatments was observed. To keep treatments iso-energetic, graded amounts of the following were fed: 1) 100% amylopectin cornstarch (Amioca; Ingredion, Bridgewater, NJ, USA), 2) high-amylose maize cornstarch (Hi-maize 260; Ingredion), and 3) cellulose (Sigma-Aldrich α-cellulose; Table 2). Fresh water was offered ad libitum.

Table 1.

Ingredient and analyzed chemical composition of the extruded experimental diet

| Ingredients | Basal extruded diet, % |

|---|---|

| Brewer’s rice | 45.22 |

| Poultry byproduct meal | 37.00 |

| Poultry fat | 14.00 |

| Dried egg | 2.40 |

| Salt | 0.45 |

| Potassium chloride | 0.56 |

| Choline chloride1 | 0.13 |

| Vitamin mix2 | 0.12 |

| Mineral mix3 | 0.12 |

| Chemical composition | |

| DM, % | 93.76 |

| ----% DM basis--- | |

| OM | 93.87 |

| CP | 37.73 |

| Acid-hydrolyzed fat | 13.21 |

| Total dietary fiber | 3.89 |

| Insoluble | 2.68 |

| Soluble | 1.21 |

| Gross energy, kcal/g | 5.12 |

| MEAAFCO4, kcal/g | 3.81 |

| Free glucose | 0.07 |

| Total starch | 40.86 |

| Total starch (without free glucose) | 40.8 |

| Digestible starch | 34.61 |

| Digestible starch (without free glucose) | 34.55 |

| RS | 6.25 |

1Provided the following per kilogram of diet: choline, 2,284.2 mg.

2Provided the following per kilogram of diet: vitamin A, 11,000 IU; vitamin D3, 900 IU; vitamin E, 57.5 IU; vitamin K, 0.6 mg; thiamin, 7.6 mg; riboflavin, 11.9 mg; pantothenic acid, 18.5 mg; niacin, 93.2 mg; pyridoxine, 6.6 mg; biotin, 12.4 mg; folic acid, 1,142.1 μg; and vitamin B12, 164.9 μg.

3Provided the following per kilogram of diet: manganese (MnSO4), 17.4 mg; iron (FeSO4), 284.3 mg; copper (CuSO4), 17.2 mg; cobalt (CoSO4), 2.2 mg; zinc (ZnSO4), 166.3 mg; iodine (KI), 7.5 mg; and selenium (Na2SeO3), 0.2 mg.

4MEAAFCO (metabolizable energy by the Association of American Feed Control Officials), ME estimated by calculating ME = 8.5 kcal ME/g fat + 3.5 kcal ME/g CP + 3.5 kcal ME/g nitrogen-free extract.

Table 2.

Five dietary starch blends used to determine the dose of RS that is well tolerated when fed to healthy adult dogs

| Control (0% RS) | 1% RS | 2% RS | 3% RS | 4% RS | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| g | kcal/g | g | kcal/g | g | kcal/g | g | kcal/g | g | kcal/g | |

| Cornstarch1 | 8.4 | 33.6 | 6.3 | 25.2 | 4.2 | 16.8 | 2.1 | 8.4 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| RS2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 3.0 | 8.4 | 6.0 | 16.8 | 9.0 | 25.2 | 12.0 | 33.6 |

| Cellulose3 | 3.6 | 0.0 | 2.7 | 0.0 | 1.8 | 0.0 | 0.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Total | 12.0 | 33.6 | 12.0 | 33.6 | 12.0 | 33.6 | 12.0 | 33.6 | 12.0 | 33.6 |

1100% amylopectin cornstarch (Amioca; Ingredion, Bridgewater, N.J., USA): 4 kcal/g.

2High-amylose maize cornstarch (Hi-maize 260; Ingredion): 2.8 kcal/g.

3Sigma-Aldrich α-cellulose: 0 kcal/g.

Experimental design and sample collection

An incomplete 5 × 5 Latin square design with seven dogs, five dietary treatments (Tables 1 and 2), and five 21-d trial periods was conducted so that each animal served as its own control. Each period consisted of a diet adaptation phase (days 0 to 17) and a total and fresh fecal collection phase (days 18 to 21). Total feces excreted during the collection phase of each period were collected from the pen floor, weighed, and frozen at −20 °C until further analyses. All fecal samples during the collection phase were subjected to a consistency score according to the following scale: 1 = hard, dry pellets, and small hard mass; 2 = hard formed, dry stool, and remains firm and soft; 3 = soft, formed and moist stool, and retains shape; 4 = soft, unformed stool, and assumes shape of container; and 5 = watery, liquid that can be poured.

One fresh fecal sample per period was collected within 15 min of defecation on day 1 of the 4-d collection phase. Fresh fecal samples were prepared immediately to minimize loss of volatile components. Samples were weighed and pH determined using a Denver Instrument AP10 pH meter (Denver Instrument, Bohemia, NY, USA) equipped with a Beckman electrode (Beckman Instruments, Inc., Fullerton, CA, USA). Fresh fecal dry matter (DM) was determined at 105 °C. Aliquots for the analysis of phenols and indoles were frozen at −20 °C immediately after collection. An aliquot (5 g) of feces was mixed with 5 mL 2N HCl for ammonia, SCFA, and branched-chain fatty acid (BCFA) determination and stored at −20 °C until analyzed. Aliquots of fresh feces were transferred to sterile cryogenic vials (Nalgene, Rochester, NY, USA) and frozen at −80 °C until DNA extraction for microbial analysis.

Chemical analyses

The diet was subsampled and ground through a 2-mm screen in a Wiley mill (model 4, Thomas Scientific, Swedesboro, NJ, USA). Composited fecal samples (one per dog per period) were dried at 55 °C for 1 wk and ground through a 2-mm screen in a Wiley Mill. Samples were analyzed according to procedures by the Association of Official Analytical Chemists for DM, organic matter (OM), and ash (AOAC, 2006; methods 934.01 and 942.05). Crude protein (CP) content was calculated from Leco total N values (TruMac N, Leco Corporation, St. Joseph, MI, USA; AOAC, 2006). Total lipid content (acid-hydrolyzed fat) of the samples was determined according to the methods of the American Association of Cereal Chemists (AACC, 1983) and Budde (1952). The gross energy of the samples was measured using an oxygen bomb calorimeter (model 1261, Parr Instruments, Moline, IL). Dietary fiber concentrations (total dietary fiber, soluble dietary fiber, and insoluble dietary fiber) were determined according to Prosky et al. (1992). The diet and all fecal samples were analyzed in duplicate, with a 5% error allowed between duplicates; otherwise, the analyses were repeated. The methods of Muir and O′Dea (1992, 1993) were used to determine the amount of digestible starch and free glucose present in the diet. Total starch content was determined using the methods of Thivend et al. (1972). RS was calculated by subtracting the digestible starch and free glucose values from the total starch content.

SCFA and BCFA concentrations were determined by gas chromatography according to Erwin et al. (1961) using Hewlett-Packard 5890A series II gas chromatograph (Palo Alto, CA, USA) and a glass column (180 cm × 4 mm i.d.) packed with 10% SP-1200/1% H3PO4 on 80/100+ mesh Chromosorb WAW (Supelco Inc., Bellefonte, PA, USA). Phenol and indole concentrations were determined using gas chromatography according to the methods of Flickinger et al. (2003). Ammonia concentrations were determined according to the method of Chaney and Marbach (1962).

Microbial analyses

Fecal DNA was extracted from freshly collected samples that had been stored at −80 °C until analysis, using the PowerLyzer PowerSoil DNA Isolation Kit (MO BIO Laboratories, Inc., Carlsbad, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Extracted DNA was quantified using a Qubit 2.0 Fluorometer (Life Technologies, Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY, USA). Polymerase chain reaction amplicons from the V4 region of the 16S rRNA gene were prepared for sequencing following a similar procedure as Cephas et al. (2011) and primers according to Kozich et al. (2013). Polymerase chain reaction amplicons of all samples were further purified using AMPure XP beads (Beckman-Coulter, Inc.). Further DNA concentration and quality was measured using a Qubit 2.0 Fluorometer. Finally, the amplicons were combined in equimolar ratios to create a DNA pool that was used for Illumina sequencing. DNA quality was assessed before sequencing using a 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent). Dual-indexing Illumina sequencing was performed at the W. M. Keck Center for Biotechnology at the University of Illinois using a MiSeq 2 × 300 nt v3 technology. After sequencing was completed, all reads were scored for quality, and any poor quality reads and primer dimers were removed.

Bioinformatics analysis of microbiota data

Forward reads were trimmed using the FASTX-Toolkit (version 0.0.13), and QIIME 1.9.1 (Caporaso et al., 2010) was used to process the resulting sequence data. Briefly, high-quality (quality value ≥ 20) sequence data derived from the sequencing process were demultiplexed according to the barcodes. Sequences were then clustered into operational taxonomic units (OTU) using UCLUST (Edgar, 2010) through a closed-reference OTU picking strategy against the Greengenes 13_8 reference database (DeSantis et al., 2006) with a 97% similarity threshold. Singletons (OTU that were observed fewer than two times) and OTU that had less than 0.01% of the total observation were discarded. A total of 3,508,029 16S rRNA-based amplicon sequences were obtained, with an average of 100,229 reads (range = 56,746 to 145,240) per sample. An even sampling depth (sequences per sample) of 56,746 sequences was used for assessing alpha- and beta-diversity measures. Beta diversity was calculated using weighted and unweighted UniFrac (Lozupone and Knight, 2005) distance measures. Bacterial taxonomy data were analyzed using ANOVA with Tukey–Kramer post hoc tests being used for pairwise comparisons. Benjamini–Hochberg false discovery rate was used to correct for multiple comparisons. All tests were done using Statistical Analyses of Metagenomic Profiles software 2.1.3 (Parks et al., 2014). All sequence data are available at the National Center for Biotechnology Information sequence read archive (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Traces/sra/) under accession number SRP286675.

Calculations and statistical analysis

All seven replications were used in all calculations and statistical analysis. Apparent total tract apparent macronutrient digestibility values were calculated using the following equation: nutrient intake (g DM/d) − nutrient output (g DM/d)/nutrient intake (g DM/d) × 100. Data were analyzed using the MIXED procedure of SAS (version 9.2, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). Fecal score data were compared using the GLIMMIX procedure of SAS. The statistical model included period and dog as random effects, whereas treatment was a fixed effect. Data were analyzed using the type 3 test of the MIXED procedure. All treatment least squares means were compared using preplanned contrasts that tested for linear and quadratic effects of RS supplementation. Means were separated using a protected least squares difference with a Tukey adjustment. Data were analyzed using the UNIVARIATE procedure to produce a normal probability plot based on residual data and visual inspection of the raw data. A probability of P < 0.05 was accepted as being statistically significant and P ≤ 0.10 accepted as trends.

Results

The basal diet contained 6.25% RS (DM basis), contributing approximately 18.3 g of RS/d based on their daily food intake (292.5 g DM/d). The treatments included 0%, 1%, 2%, 3%, and 4% of an additional RS source. Because Hi-maize 260 is approximately 40% digestible and 60% indigestible starch, the dogs received the following amounts of RS daily: 0% = 18.3 g (18.3 + 0 g), 1% = 20.1 g (18.3 + 1.8 g), 2% = 21.9 g (18.3 + 3.6 g), 3% = 23.7 g (18.3 + 5.4 g), and 4% = 25.5 g (18.3 + 7.2 g). DM, OM, CP, fat, and energy digestibilities and fecal pH were linearly decreased (P < 0.05) with increased RS consumption (Table 3). Fecal output was linearly increased (P < 0.05) with increased RS consumption. Fecal scores and fecal fermentative end-product concentrations, including ammonia, SCFA, BCFA, phenols, and indoles, were not affected by RS consumption (Table 4).

Table 3.

Mean food intake, fecal characteristics, and apparent total tract macronutrient digestibility of adult dogs fed graded levels of RS

| Diet, % Hi-maize 260 | P-value | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | Pooled SEM | Treatment | Linear | Quadratic |

| Food intake | |||||||||

| g DM/d | 292.5 | 292.5 | 292.5 | 292.5 | 292.5 | n/a2 | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| g OM/d | 275.3 | 275.3 | 275.2 | 275.2 | 275.2 | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| g CP/d | 110.4 | 110.4 | 110.4 | 110.4 | 110.4 | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| g AHF1/d | 38.6 | 38.6 | 38.6 | 38.6 | 38.6 | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Gross energy, kcal/d | 1,496.7 | 1,496.6 | 1,496.5 | 1,496.4 | 1,496.3 | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| MEC3, kcal/g | 4.08 | 4.03 | 4.00 | 4.04 | 4.02 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.06 |

| Fecal output (g/d, as-is) | 138.6 | 149.3 | 156.3 | 156.0 | 155.0 | 7.01 | 0.06 | 0.01 | 0.10 |

| Fecal output (g/d, DM basis) | 45.9 | 49.3 | 52.5 | 49.6 | 51.2 | 1.66 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.06 |

| Fecal output (as-is)/food intake (DM basis) | 0.47 | 0.51 | 0.54 | 0.53 | 0.53 | 0.024 | 0.06 | 0.01 | 0.08 |

| Digestibility | |||||||||

| DM, % | 84.3 | 83.1 | 82.0 | 83.1 | 82.5 | 0.57 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.06 |

| OM, % | 87.8 | 86.8 | 85.9 | 86.7 | 86.2 | 0.49 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.06 |

| CP, % | 82.4 | 81.0 | 79.5 | 80.2 | 79.9 | 0.93 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.06 |

| AHF, % | 92.2 | 91.5 | 91.2 | 91.7 | 91.3 | 0.25 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.11 |

| Energy, % | 87.4 | 86.3 | 85.5 | 86.3 | 85.9 | 0.50 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.06 |

| Fecal pH | 6.7 | 6.4 | 6.5 | 6.4 | 6.4 | 0.12 | 0.10 | 0.03 | 0.20 |

| Fecal scores4 | 3.1 | 3.2 | 3.0 | 3.4 | 3.1 | 0.14 | 0.01 | 0.36 | 0.34 |

| Fecal DM, % | 33.5 | 31.8 | 33.5 | 33.6 | 32.3 | 1.27 | 0.69 | 0.73 | 0.86 |

1AHF, acid-hydrolyzed fat.

2All dogs were fed the same amount of experimental diet throughout the duration of the study. All food was consumed each day.

3Calculated metabolizable energy (MEC) = gross energy intake (kcal/d) − fecal gross energy (kcal/d) − urinary gross energy (kcal/d)/DM intake (g/d).

4Fecal score scale: 1 = hard, dry pellets; 2 = dry, well-formed stool; 3 = soft, moist, formed stool; 4 = soft, unformed stool; and 5 = watery, liquid that can be poured.

Table 4.

Mean fecal ammonia, SCFA, BCFA, phenol, and indole concentrations of adult dogs fed graded levels of dietary RS

| Diet, % Hi-maize 260 | P-value | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | Pooled SEM | Treatment | Linear | Quadratic |

| ---------------------μmol/g DM--------------------- | |||||||||

| Ammonia | 155.6 | 151.1 | 140.4 | 136.2 | 149.6 | 8.07 | 0.33 | 0.32 | 0.13 |

| SCFA | |||||||||

| Acetate | 267.0 | 256.7 | 261.2 | 252.5 | 275.2 | 20.91 | 0.85 | 0.77 | 0.37 |

| Propionate | 105.1 | 112.1 | 107.5 | 96.0 | 102.9 | 6.02 | 0.21 | 0.28 | 0.69 |

| Butyrate | 69.1 | 63.9 | 62.5 | 63.7 | 67.5 | 5.05 | 0.75 | 0.79 | 0.19 |

| Total SCFA1 | 441.4 | 432.7 | 430.9 | 412.2 | 445.5 | 29.04 | 0.85 | 0.93 | 0.43 |

| BCFA | |||||||||

| Isobutryate | 17.0 | 16.6 | 16.4 | 14.5 | 16.4 | 1.17 | 0.31 | 0.34 | 0.38 |

| Isovalerate | 23.3 | 22.7 | 21.9 | 20.8 | 22.4 | 1.57 | 0.75 | 0.44 | 0.44 |

| Valerate | 0.9 | 1.0 | 1.1 | 0.8 | 2.2 | 0.53 | 0.39 | 0.13 | 0.32 |

| Total BCFA2 | 41.2 | 40.2 | 39.3 | 36.3 | 40.9 | 2.71 | 0.53 | 0.64 | 0.28 |

| Phenols and indoles | |||||||||

| Phenol | 3.2 | 3.3 | 2.8 | 2.9 | 2.8 | 0.75 | 0.79 | 0.35 | 0.91 |

| Indole | 4.2 | 4.2 | 3.7 | 3.9 | 4.4 | 0.33 | 0.57 | 0.83 | 0.19 |

| Total phenols/indoles | 7.3 | 7.5 | 6.6 | 6.8 | 7.1 | 0.84 | 0.78 | 0.62 | 0.56 |

1Total SCFA = acetate + propionate + butyrate.

2Total BCFA = isobutyrate + isovalerate + valerate.

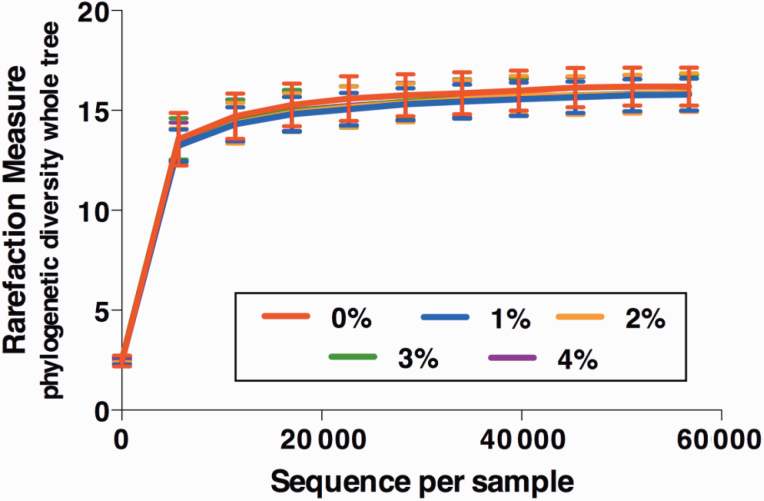

Alpha diversity, which measured species richness within a sample, was not affected by RS consumption (Figure 1). Beta diversity, which measured similarity and dissimilarity among samples, is represented by principal coordinates analysis plots (Figure 2). Unweighted UniFrac distances, which measured the presence or absence of microbial taxa, indicated that fecal microbial communities were not affected by RS consumption (Figure 2A). Weighted UniFrac distances, which measured the presence and abundance of microbial taxa, indicated that fecal microbial communities were not affected by RS consumption (Figure 2B).

Figure 1.

Species richness of the fecal microbial communities of adult dogs fed graded levels of RS. Alpha diversity measurements using the phylogenetic diversity whole tree suggested that the inclusion of RS does not impact species richness of the fecal microbial communities of adult dogs.

Figure 2.

Fecal microbial communities of adult dogs fed graded levels of RS. Principal coordinates analysis plots of unweighted (A) and weighted (B) UniFrac distances of fecal microbial communities performed on the 97% OTU abundance matrix revealed that the inclusion of RS does not affect (P > 0.05) fecal microbial communities of adult dogs.

Predominant bacterial phyla present in all dogs included Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, Fusobacteria, Proteobacteria, Actinobacteria, and Tenericutes (Table 5). The phyla, Deferribacteres and Synergistetes, were also detected but at a much lesser degree than the other phyla (<0.01% of sequences; data not shown). Together, Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes made up about 80% of all bacterial sequences, with Fusobacteria representing about 15%, Proteobacteria representing about 4%, and Actinobacteria and Tenericutes each representing <1% of all bacterial sequences. Predominant bacterial genera included Prevotella (Bacteroidetes), Clostridium (Firmicutes), Fusobacterium (Firmicutes), Bacteroides (Bacteroidetes), and Lactobacillus (Firmicutes), which were present at an average of 25%, 18%, 15%, 10%, and 6% of bacterial sequences, respectively. Faecalibacterium, which belong to the phylum Firmicutes, were increased (P ≤ 0.05) with increased RS consumption. Roseburia, which belongs to the phylum Firmicutes, tended to increase (P < 0.10) with increased RS consumption. Anaerotruncus, which belongs to the phylum Firmicutes, tended to decrease (P < 0.10) with increased RS consumption.

Table 5.

Prominent bacterial phyla and genera (expressed as percentage of total sequences) in feces of dogs fed graded levels of dietary RS

| Diet, % Hi-maize 260 | P-value | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | Pooled SEM | Treatment | Linear | Quadratic |

| Actinobacteria | 0.91 | 1.04 | 0.91 | 0.94 | 0.78 | 0.21 | 0.87 | 0.52 | 0.52 |

| Collinsella | 0.70 | 0.78 | 0.72 | 0.63 | 0.61 | 0.16 | 0.85 | 0.39 | 0.64 |

| Slackia | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.02 | 0.92 | 0.43 | 0.83 |

| Coriobacterium | 0.06 | 0.13 | 0.09 | 0.12 | 0.07 | 0.04 | 0.64 | 0.89 | 0.24 |

| Adlercreutzia | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.36 | 0.15 | 0.47 |

| Bifidobacterium | 0.02 | <0.01 | 0.01 | 0.11 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.49 | 0.60 | 0.68 |

| Bacteroidetes | 36.38 | 36.39 | 36.65 | 34.96 | 41.14 | 4.78 | 0.70 | 0.44 | 0.38 |

| Prevotella | 25.48 | 24.88 | 24.79 | 23.58 | 28.55 | 3.64 | 0.72 | 0.59 | 0.29 |

| Bacteroides | 9.89 | 9.29 | 9.42 | 9.67 | 11.22 | 2.19 | 0.90 | 0.54 | 0.45 |

| CF231 | 1.29 | 1.45 | 0.49 | 1.09 | 0.68 | 0.61 | 0.29 | 0.17 | 0.76 |

| Parabacteroides | 0.40 | 0.29 | 0.36 | 0.47 | 0.38 | 0.18 | 0.29 | 0.59 | 0.83 |

| Unclassified | 0.32 | 0.27 | 0.32 | 0.29 | 0.20 | 0.11 | 0.65 | 0.28 | 0.46 |

| Parapedobacter | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.07 | 0.12 | 0.08 | 0.06 | 0.66 | 0.58 | 1.00 |

| Firmicutes | 44.65 | 42.06 | 44.58 | 45.80 | 37.51 | 5.11 | 0.38 | 0.43 | 0.29 |

| Clostridium | 16.28 | 18.67 | 17.16 | 19.31 | 16.91 | 2.72 | 0.89 | 0.81 | 0.51 |

| Lactobacillus | 10.23 | 5.32 | 4.12 | 7.41 | 3.76 | 2.90 | 0.35 | 0.21 | 0.46 |

| Blautia | 3.47 | 4.29 | 4.75 | 4.29 | 4.66 | 0.69 | 0.66 | 0.28 | 0.46 |

| Phascolarctobacterium | 3.13 | 3.75 | 4.20 | 3.58 | 3.73 | 0.74 | 0.73 | 0.56 | 0.33 |

| Dorea | 2.91 | 3.34 | 3.40 | 3.17 | 3.00 | 0.58 | 0.85 | 0.99 | 0.28 |

| Ruminococcus | 1.63 | 1.73 | 1.27 | 1.49 | 1.47 | 0.22 | 0.51 | 0.36 | 0.54 |

| Megamonas | 1.61 | 1.99 | 1.85 | 0.87 | 1.37 | 0.60 | 0.40 | 0.26 | 0.72 |

| Faecalibacterium | 1.23 | 0.96 | 1.49 | 1.46 | 1.80 | 0.30 | 0.20 | 0.05 | 0.46 |

| unclassified | 1.03 | 1.01 | 1.37 | 1.09 | 1.14 | 0.31 | 0.66 | 0.59 | 0.47 |

| SMB53 | 0.72 | 0.54 | 0.41 | 0.47 | 0.27 | 0.21 | 0.26 | 0.04 | 0.77 |

| Turicibacter | 0.52 | 0.42 | 0.52 | 0.40 | 0.27 | 0.19 | 0.54 | 0.18 | 0.51 |

| Peptococcus | 0.37 | 0.43 | 0.55 | 0.26 | 0.47 | 0.23 | 0.68 | 0.94 | 0.84 |

| Allobaculum | 0.21 | 0.23 | 0.29 | 0.39 | 0.32 | 0.08 | 0.41 | 0.11 | 0.55 |

| Coprococcus | 0.19 | 0.05 | 0.08 | 0.20 | 0.14 | 0.05 | 0.19 | 0.78 | 0.24 |

| Anaerofilum | 0.16 | 0.16 | 0.16 | 0.14 | 0.13 | 0.04 | 0.93 | 0.42 | 0.73 |

| Oscillospira | 0.11 | 0.09 | 0.11 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.03 | 0.95 | 0.77 | 0.80 |

| Eubacterium | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.33 | 0.65 | 0.35 |

| Catenibacterium | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.09 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.63 | 0.74 | 0.51 |

| Lachnospira | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.58 | 0.73 | 0.17 |

| Anaerostipes | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.01 | 0.60 | 0.28 | 0.77 |

| Anaerotruncus | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.36 | 0.07 | 0.32 |

| Roseburia | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.28 | 0.10 | 0.69 |

| Coprobacillus | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.34 | 0.58 | 0.22 |

| Pectinatus | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.26 | 0.84 | 0.16 |

| Bulleidia | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.01 | <0.01 | 0.83 | 0.39 | 0.54 |

| Butyrivibrio | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.46 | 0.15 | 0.36 |

| Epulopiscium | 0.01 | 0.03 | <0.01 | 0.05 | <0.01 | 0.02 | 0.24 | 0.98 | 0.47 |

| Fusobacteria | 15.08 | 15.97 | 15.54 | 15.38 | 14.23 | 2.05 | 0.91 | 0.59 | 0.45 |

| Fusobacterium | 14.96 | 15.85 | 15.35 | 15.26 | 14.14 | 2.03 | 0.92 | 0.60 | 0.47 |

| u114 | 0.10 | 0.13 | 0.21 | 0.12 | 0.09 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.65 | 0.01 |

| Proteobacteria | 3.32 | 3.53 | 5.07 | 3.61 | 3.50 | 1.06 | 0.71 | 0.90 | 0.35 |

| Sutterella | 2.51 | 3.24 | 2.33 | 2.42 | 2.22 | 0.55 | 0.38 | 0.25 | 0.56 |

| Serratia | 0.66 | 0.23 | 2.47 | 0.92 | 1.36 | 1.09 | 0.64 | 0.55 | 0.61 |

| Anaerobiospirillum | 0.09 | 0.17 | 0.08 | 0.10 | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.64 | 0.53 | 0.68 |

| Succinivibrio | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.35 | 0.15 | 0.92 |

| Tenericutes | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.01 | <0.01 | 0.51 | 0.65 | 0.97 |

| Anaeroplasma | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | <0.01 | 0.33 | 0.83 | 0.93 |

Discussion

By definition, RS is starch that escapes digestion in the small intestine and ends up in the large bowel, part of which may be fermented in the colon (Sajilata et al., 2006). Increased RS consumption may lead to decreased nutrient digestibility, increased fecal output, altered fecal scores, increased fecal concentrations of SCFA, reduced fecal pH, and altered GI microbiota populations, depending on the particle size, source of RS, and size of dog (Goudez et al., 2011; Bazolli et al., 2015; Peixoto et al., 2018). In the current study, increasing RS intake linearly increased fecal output and reduced apparent macronutrient and energy digestibility without altering food intake or fecal scores to any great extent. The greater fecal output (~12%) may aid in promoting laxation. The changes in apparent total tract macronutrient digestibilities with greater RS consumption in the current study were moderate (1 to 2.5 percentage units) and in line with previous studies (Bazolli et al., 2015; Peixoto et al., 2018). Reduced protein digestibility may have been the result of higher microbial activity and nitrogen excretion in the feces, which has been reported with greater nondigestible carbohydrate intake previously (Verlinden et al., 2006; Peixoto et al., 2018). Reduced fat digestibility may be the result of amylose–lipid complex formation or physical interference with digestive enzymes (Gajda et al., 2005; Bazolli et al., 2015).

Nondigestible carbohydrates, including dietary fibers, RS, and prebiotics, are of interest because they may influence GI and host health in many ways. Many of the health benefits are related to their utilization by the microbiota and the production of SCFA. These organic acids provide energy to GI epithelial cells, reduce colonic pH that maintains low pathogen levels, maintain barrier function, and more (Koh et al., 2016). Although the fermentation of protein produces some SCFA, they also lead to the production of putrefactive compounds such as phenols, indoles, and ammonia that may be detrimental to colon health (Cummings and Macfarlane, 1991). Dietary fibers and prebiotics have been used to beneficially modify the GI microbiota and health of dogs over the past couple of decades (Swanson et al., 2002; Flickinger et al., 2003; Propst et al., 2003; Grieshop et al., 2004; Middelbos et al., 2007a; Beloshapka et al., 2013).

In humans and pigs, RS has been shown to be highly fermentable and effective in modulating the gut microbial composition, reducing pH and protein-derived metabolites, and increasing fecal SCFA when compared with digestible starch (Bird et al., 2007; Rideout et al., 2008; Haenen et al., 2013). Bird et al. (2007) compared the effects of experimental diets containing digestible or RS on the pH and metabolites in the large bowel of 4-wk-old pigs. Those researchers reported reduced fecal pH and higher concentrations of total SCFA, acetate, propionate, and butyrate in the colon of pigs fed RS-containing diets compared with control pigs. Rideout et al. (2008) conducted a similar study, investigating the nutrient utilization and intestinal fermentation of various RS varieties and conventional fiber sources, including granular high-amylose corn starch, granular potato starch, retrograded high-amylose corn starch, guar gum, or cellulose, when fed to Yorkshire pigs. Those authors reported higher cecal butyrate concentrations and lower cecal indole, isobutyrate, and isovalerate concentrations in pigs fed RS compared with controls.

RS would be expected to be fermented by the intestinal microbiota of dogs, leading to alterations in metabolite profiles, but this has only been studied in dogs a couple of times (Bazolli et al., 2015; Peixoto et al., 2018). Bazolli et al. (2015) tested dietary starch sources (rice, maize, and sorghum) and particle sizes (300, 450, or 600 μm) in a 3 × 3 factorial design. Although rice-based diets had little influence, the maize- and sorghum-based diets linearly reduced nutrient digestibility and increased fecal butyrate concentrations with increasing particle size. Unfortunately, protein-based metabolites were not measured in that study. In Peixoto et al. (2018), low- vs. high-RS diets were compared. In addition to having reduced nutrient digestibilities, dogs fed the high-RS diet had a lower fecal pH, higher butyrate, propionate, lactate, and total SCFA concentrations than controls. Fecal ammonia concentrations were reduced with high-RS consumption, but fecal BCFA were not affected by diet. In the current study, fecal ammonia, SCFA, BCFA, phenols, and indoles were unchanged by RS, suggesting a poor or slow rate of fermentation. Alternatively, fecal metabolites were not altered by RS consumption in the current study because of the high absorption rates that are known to occur in the colon (von Englehardt et al., 1989).

Even though Carnivora such as dogs and cats did not evolve consuming high concentrations of fiber and other nondigestible carbohydrates, their GI tracts possess dense populations of active microbiota important to health (Samal et al., 2011; Barko et al., 2018). The primary bacterial phyla include Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, Proteobacteria, Fusobacteria, and Actinobacteria, but the abundance depends on the region of the GI tract and sample type (digesta vs. mucosa vs. feces; Suchodolski et al., 2008; Swanson et al., 2011). Even though the effects of RS on GI microbiota have not been well tested in dogs, previous research in other species led us to hypothesize that fecal microbial populations would be altered by RS consumption in the current study.

In the current study, few statistical changes were observed in the fecal microbiota. Fecal Faecalibacterium was linearly increased with RS in this study. Because this taxon is a butyrate producer (Duncan et al., 2002), this change is deemed to be a positive response and is in line with studies in humans (Walker et al., 2011). The change in this taxon was relatively small, however (0.6% relative abundance difference between control and 4% treatment). Much larger numerical changes were observed for Lactobacillus (from 10.2% [controls] to 3.8% [4% treatment]), Prevotella (from 25.5% [controls] to 28.6% [4% treatment]), and Blautia (from 3.5% [controls] to 4.7% [4% treatment]), but they were not different statistically due to high variability. These microbiota shifts suggest future testing of RS in dogs but with larger sample sizes that may provide more statistical power.

Ruminococcus bromii, in particular, is known to be an important bacterial taxon involved in its fermentation (Ze et al., 2012). In addition to Ruminococcus, other bacterial taxa, including Oscillibacter, Eubacterium, and Faecalibacterium, have been shown to be elevated with RS feeding in humans (Walker et al., 2011). Additionally, mice fed approximately 10.8% pure RS (Hi-maize 260) had higher proportions of cecal Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium spp. (Tachon et al., 2013). The substrate used in that study was the same as in the current study but fed at higher dosages (18% and 36%). Furthermore, the fermentation site varies between the host species (i.e., cecum vs. colon), which may explain some of these differences. Because there are differences among fecal, digesta, and mucosal samples, the sampling of intestinal digesta or mucosa may be preferred from a scientific perspective but requires invasive techniques. Although noninvasive collection devices may be available in the future (Hällgren, 2003; Sinaiko, 2004), feces are the most commonly collected samples currently. Such samples may not be indicative of the small intestine but should serve as a good proxy for the large intestinal environment.

The predominant fecal bacterial phyla detected in the current study were similar to previous studies but different in distribution (Suchodolski et al., 2008, 2009; Middelbos et al., 2010; Handl et al., 2011; Suchodolski, 2011; Swanson et al., 2011; Beloshapka et al., 2013). Based on the utilization of new primers, a more even distribution of bacterial groups was noted herein. Previous studies that used primers targeting V4-V6 regions and 454 pyrosequencing to evaluate fecal bacterial populations produced a composition that was low in Bacteroidetes, Lactobacillus, and Bifidobacterium spp. (Hooda et al., 2012; Beloshapka et al., 2013).

In this study, the most effective dose of a highly pure, single-source RS was not as easily determined as hypothesized. Many dietary fibers and prebiotics are rapidly fermented by gut microbiota of dogs, demonstrated by a reduced fecal pH, increased fecal SCFA, and altered microbiota populations (Vickers et al., 2001; Swanson et al., 2002; Flickinger et al., 2003; Propst et al., 2003; Zentek et al., 2003; Middelbos et al., 2007a, 2007b; Beloshapka et al., 2012, 2013). Given data from humans, pigs, and rodents, a similar response was anticipated for RS. Whether it was due to the relatively short transit time or the simplistic large bowel anatomy (i.e., unsacculated colon; colonic fermenter vs. cecal as is in rodent models) of the dog, the microbiota present in the canine gut, or some other factor, the fermentation capacity of RS was not as extensive as expected in the dog. The source of RS may also be in question. The source of RS used in the current study was Hi-maize 260, which is projected to be 60% RS and 40% digestible starch, is resistant to cooking, and may be less fermentable than other sources. Because data from Beloshapka et al. (2014) seem to agree with the results presented here, however, it may just be that RS is too poorly and/or slowly fermented to elicit any measurable effects of GI health indices in dogs. Although it may be useful in reducing caloric content and promoting laxation, our research suggests that RS does not appear to possess prebiotic-like properties in dogs.

This study had some strengths and limitations. One strength was the use of the Latin square design, which allows each animal to serve as its own control, reducing variation and increasing statistical power. Another strength was the testing of several doses of RS, which allowed for the testing of linear or quadratic treatment effects. One limitation was the low number of animals (n = 7/treatment). While this number of animals is often used for digestibility studies and should be sufficient for most of the outcomes measured in this study (food intake, fecal output, nutrient digestibility, fecal characteristics, and metabolites), it may not have provided sufficient statistical power for microbiota data that have a higher level of variability. A replicated Latin square using 10 dogs would have provided more statistical power and two complete squares. Also, a healthy animal population was used in this study, increasing the difficulty in observing differences in GI health indices in relation to a clinical population. Lastly, the high level of RS present in the basal diet, which translated to approximately 18.3 g of RS/d, may have masked some of the effects of the treatments tested.

In conclusion, the doses of Hi-maize 260 used in the current study were chosen based on the purity of the substrate and expected amount at which GI tolerance was maintained, but greater concentrations of fecal SCFA and beneficial bacteria were achieved. Minor changes in these indices of GI health were observed, however. It is possible that a larger amount of this particular substrate is needed to manipulate typical indices of gut health in the dog. The results of the current study may indicate that canine GI transit time or anatomy (i.e., lack of sacculations, colonic fermentor) or microbiota populations do not support the use of pure sources of RS as a fermentable dietary fiber source in dogs. Even though RS may not provide great benefits to dogs through fermentation, the reduced nutrient and energy digestibility with increasing dietary RS suggest that it may be used to reduce caloric density and have application in obesity diets.

Acknowledgments

The funding for this study was provided by United States Department of Agriculture Hatch (ILLU-538-384). We would like to thank Christopher Fields and Ravikiran Donthu for their assistance with the microbiota analyses conducted in this study.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- AHF

acid-hydrolyzed fat

- BCFA

branched-chain fatty acids

- CP

crude protein

- DM

dry matter

- GI

gastrointestinal

- ME

metabolizable energy

- MEAAFCO

metabolizable energy by the Association of American Feed Control Officials

- OM

organic matter

- OTU

operational taxonomic units

- RS

resistant starch

- SCFA

short-chain fatty acids

Conflict of interest statement

All authors have no conflicts of interest.

Literature Cited

- AACC. 1983. Approved methods. In: AACC, editor. 8th ed. St Paul (MN): American Association of Cereal Chemists. [Google Scholar]

- AAFCO . 2012. Official publication. Oxford (IN): Association of American Feed Control Officials, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- AOAC . 2006. Official methods of analysis of AOAC international. 17th ed. Arlington (VA): Association of Official Analysis Chemists International. [Google Scholar]

- Barko, P. C., M. A. McMichael, K. S. Swanson, and D. A. Williams. . 2018. The gastrointestinal microbiome: a review. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 32:9–25. doi: 10.1111/jvim.14875 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bazolli, R. S., R. S. Vasconcellos, L. D. de-Oliveira, F. C. Sá, G. T. Pereira, and A. C. Carciofi. . 2015. Effect of the particle size of maize, rice, and sorghum in the extruded diets for dogs on starch gelatinization, digestibility, and the fecal concentrations of fermentation products. J. Anim. Sci. 93:2956–2966. doi: 10.2527/jas2014-8409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beloshapka, A. N., L. G. Alexander, P. R. Buff, and K. S. Swanson. . 2014. The effects of feeding resistant starch on apparent total tract macronutrient digestibility, faecal characteristics, and faecal fermentative end-products in healthy adult dogs. J. Nutr. Sci. 3:e38. doi: 10.1017/jns.2014.28 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beloshapka, A. N., S. E. Dowd, J. S. Suchodolski, J. M. Steiner, L. Duclos, and K. S. Swanson. . 2013. Fecal microbial communities of healthy adult dogs fed raw meat-based diets with or without inulin or yeast cell wall extracts as assessed by 454 pyrosequencing. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 84:532–541. doi: 10.1111/1574-6941.12081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beloshapka, A. N., L. M. Duclos, B. M. Vester Boler, and K. S. Swanson. . 2012. Effects of inulin or yeast cell-wall extract on nutrient digestibility, fecal fermentative end-product concentrations, and blood metabolite concentrations in adult dogs fed raw meat-based diets. Am. J. Vet. Res. 73:1016–1023. doi: 10.2460/ajvr.73.7.1016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bird, A. R., M. Vuaran, I. Brown, and D. L. Topping. . 2007. Two high-amylose maize starches with different amounts of resistant starch vary in their effects on fermentation, tissue and digesta mass accretion, and bacterial populations in the large bowel of pigs. Br. J. Nutr. 97:134–144. doi: 10.1017/S0007114507250433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradshaw, J. W. S. 2006. The evolutionary basis for the feeding behavior of domestic dogs (Canis familiaris) and cats (Felis catus). J. Nutr. 136:1927S–1931S. doi: 10.1093/jn/136.7.1927S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budde, E. F. 1952. The determination of fat in baked biscuit type of dog foods. J. Assoc. Off. Agric. Chem. 35:799–805. doi: 10.1093/jaoac/35.3.799 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Caporaso, J. G., J. Kuczynski, J. Stombaugh, K. Bittinger, F. D. Bushman, E. K. Costello, N. Fierer, A. G. Peña, J. K. Goodrich, J. I. Gordon, . et al. 2010. QIIME allows analysis of high-throughput community sequencing data. Nat. Methods 7:335–336. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.f.303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cephas, K. D., J. Kim, R. A. Mathai, K. A. Barry, S. E. Dowd, B. S. Meline, and K. S. Swanson. . 2011. Comparative analysis of salivary bacterial microbiome diversity in edentulous infants and their mothers or primary care givers using pyrosequencing. PLoS One 6:e23503. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaney, A. L., and E. P. Marbach. . 1962. Modified reagents for determination of urea and ammonia. Clin. Chem. 8:130–132. doi: 10.1093/clinchem/8.2.130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings, J. H., and G. T. Macfarlane. . 1991. The control and consequences of bacterial fermentation in the human colon. J. Appl. Bacteriol. 70:443–459. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1991.tb02739.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeSantis, T. Z., P. Hugenholtz, N. Larsen, M. Rojas, E. L. Brodie, K. Keller, T. Huber, D. Dalevi, P. Hu, and G. L. Andersen. . 2006. Greengenes, a chimera-checked 16S rRNA gene database and workbench compatible with ARB. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72:5069–5072. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03006-05 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan, S. H., G. L. Hold, H. J. M. Harmsen, C. S. Stewart, and H. J. Flint. . 2002. Growth requirements and fermentation products of Fusobacterium prausnitzii, and a proposal to reclassify it as Faecalibacterium prausnitzii gen. nov., comb. nov. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 52(Pt 6):2141–2146. doi: 10.1099/00207713-52-6-2141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar, R. C. 2010. Search and clustering orders of magnitude faster than BLAST. Bioinformatics 26:2460–2461. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Englyst, H. N., S. M. Kingman, and J. H. Cummings. . 1992. Classification and measurement of nutritionally important starch fractions. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 46:S33–S50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erwin, E. S., G. J. March, and E. M. Emery. . 1961. Volatile fatty acid analyses of blood and rumen fluid by gas chromatography. J. Dairy Sci. 44:1768–1771. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(61)89956-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Flickinger, E. A., E. M. Schreijen, A. R. Patil, H. S. Hussein, C. M. Grieshop, N. R. Merchen, and G. C. Fahey Jr. 2003. Nutrient digestibilities, microbial populations, and protein catabolites as affected by fructan supplementation of dog diets. J. Anim. Sci. 81:2008–2018. doi: 10.2527/2003.8182008x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gajda, M., E. A. Flickinger, C. M. Grieshop, L. L. Bauer, N. R. Merchen, and G. C. Fahey Jr. 2005. Corn hybrid affects in vitro and in vivo measures of nutrient digestibility in dogs. J. Anim. Sci. 83:160–171. doi: 10.2527/2005.831160x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goudez, R., M. Weber, V. Biourge, and P. Nguyen. . 2011. Influence of different levels and sources of resistant starch on faecal quality of dogs of various body sizes. Br. J. Nutr. 106:S211–S215. doi: 10.1017/S0007114511003345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grieshop, C. M., E. A. Flickinger, K. J. Bruce, A. R. Patil, G. L. Czarnecki-Maulden, and G. C. Fahey Jr. 2004. Gastrointestinal and immunological responses of senior dogs to chicory and mannan-oligosaccharides. Arch. Anim. Nutr. 58:483–493. doi: 10.1080/00039420400019977 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haenen, D., J. Zhang, C. Souza da Silva, G. Bosch, I. M. van der Meer, J. van Arkel, J. J. van den Borne, O. Pérez Gutiérrez, H. Smidt, B. Kemp, . et al. 2013. A diet high in resistant starch modulates microbiota composition, SCFA concentrations, and gene expression in pig intestine. J. Nutr. 143:274–283. doi: 10.3945/jn.112.169672 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hällgren, R. 2003. Apparatus for intestinal sampling and use thereof. United States patent No. US 6576429B1. U.S. Patent and Trademark Office. https://patents.google.com/patent/US6576429B1/en. Accessed September 29, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Handl, S., S. E. Dowd, J. F. Garcia-Mazcorro, J. M. Steiner, and J. S. Suchodolski. . 2011. Massive parallel 16S rRNA gene pyrosequencing reveals highly diverse fecal bacterial and fungal communities in healthy dogs and cats. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 76:301–310. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2011.01058.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooda, S., B. M. Boler, M. C. Serao, J. M. Brulc, M. A. Staeger, T. W. Boileau, S. E. Dowd, G. C. Fahey Jr, and K. S. Swanson. . 2012. 454 Pyrosequencing reveals a shift in fecal microbiota of healthy adult men consuming polydextrose or soluble corn fiber. J. Nutr. 142:1259–1265. doi: 10.3945/jn.112.158766 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koh, A., F. De Vadder, P. Kovatcheva-Datchary, and F. Bäckhed. . 2016. From dietary fiber to host physiology: short-chain fatty acids as key bacterial metabolites. Cell 165:1332–1345. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.05.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozich, J. J., S. L. Westcott, N. T. Baxter, S. K. Highlander, and P. D. Schloss. . 2013. Development of a dual-index sequencing strategy and curation pipeline for analyzing amplicon sequence data on the MiSeq Illumina sequencing platform. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 79:5112–5120. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01043-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lozupone, C., and R. Knight. . 2005. UniFrac: a new phylogenetic method for comparing microbial communities. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:8228–8235. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.12.8228-8235.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez, I., J. Kim, P. R. Duffy, V. L. Schlegel, and J. Walter. . 2010. Resistant starches types 2 and 4 have differential effects on the composition of the fecal microbiota in human subjects. PLoS One. 5:e15046. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Middelbos, I. S., N. D. Fastinger, and G. C. Fahey Jr. 2007a. Evaluation of fermentable oligosaccharides in diets fed to dogs in comparison to fiber standards. J. Anim. Sci. 85:3033–3044. doi: 10.2527/jas.2007-0080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Middelbos, I. S., M. R. Godoy, N. D. Fastinger, and G. C. Fahey, Jr. 2007b. A dose-response evaluation of spray-dried yeast cell wall supplementation of diets fed to adult dogs: effects on nutrient digestibility, immune indices, and fecal microbial populations. J. Anim. Sci. 85:3022–3032. doi: 10.2527/jas.2007-0079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Middelbos, I. S., B. M. Vester Boler, A. Qu, B. A. White, K. S. Swanson, and G. C. Fahey, Jr. 2010. Phylogenetic characterization of fecal microbial communities of dogs fed diets with or without supplemental dietary fiber using 454 pyrosequencing. PLoS One. 5:e9768. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009768 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muir, J. G., and K. O′Dea. . 1992. Measurement of resistant starch: factors affecting the amount of starch escaping digestion in vitro. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 56:123–127. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/56.1.123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muir, J. G., and K. O′Dea. . 1993. Validation of an in vitro assay for predicting the amount of starch that escapes digestion in the small intestine of humans. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 57:540–546. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/57.4.540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parks, D. H., G. W. Tyson, P. Hugenholtz, and R. G. Beiko. . 2014. STAMP: statistical analysis of taxonomic and functional profiles. Bioinformatics 30:3123–3124. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peixoto, M. C., É. M. Ribeiro, A. P. J. Maria, B. A. Loureiro, L. G. di Santo, T. C. Putarov, F. N. Yoshitoshi, G. T. Pereira, L. R. M. Sá, and A. C. Carciofi. . 2018. Effect of resistant starch on the intestinal health of old dogs: fermentation products and histological features of the intestinal mucosa. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. (Berl). 102:e111–e121. doi: 10.1111/jpn.12711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Propst, E. L., E. A. Flickinger, L. L. Bauer, N. R. Merchen, and G. C. Fahey, Jr. 2003. A dose-response experiment evaluating the effects of oligofructose and inulin on nutrient digestibility, stool quality, and fecal protein catabolites in healthy adult dogs. J. Anim. Sci. 81:3057–3066. doi: 10.2527/2003.81123057x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prosky, L., N. G. Asp, T. F. Schweizer, J. W. De Vries, and I. Furda. . 1992. Determination of insoluble and soluble dietary fiber in foods and food products: collaborative study. J. AOAC 75:360–367. doi: 10.1093/jaoac/75.2.360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rideout, T. C., Q. Liu, P. Wood, and M. Z. Fan. . 2008. Nutrient utilisation and intestinal fermentation are differentially affected by the consumption of resistant starch varieties and conventional fibres in pigs. Br. J. Nutr. 99:984–992. doi: 10.1017/S0007114507853396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sajilata, M. G., R. S. Singhal, and P. R. Kulkarni. . 2006. Resistant starch: a review. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 5:1–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-4337.2006.tb00076.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samal, L., A. Pattanaik, and C. Mishra. . 2011. Application of molecular tools for gut health of pet animals: a review. J. Adv. Vet. Res. 1:38–46. [Google Scholar]

- Sinaiko, R. J. 2004. Externally controlled intestinal content sampler. United States patent no. US5316015A. U.S. Patent and Trademark Office. https://patents.google.com/patent/US5316015A/en. Accessed September 29, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Suchodolski, J. S. 2011. Companion Animal Symposium: Microbes and gastrointestinal health of dogs and cats. J. Anim. Sci. 89:1520–1530. doi: 10.2527/jas.2010-3377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suchodolski, J. S., J. Camacho, and J. M. Steiner. . 2008. Analysis of bacterial diversity in the canine duodenum, jejunum, ileum, and colon by comparative 16S rRNA gene analysis. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 66:567–578. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2008.00521.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suchodolski, J. S., S. E. Dowd, E. Westermarck, J. M. Steiner, R. D. Wolcott, T. Spillmann, and J. A. Harmoinen. . 2009. The effect of the macrolide antibiotic tylosin on microbial diversity in the canine small intestine as demonstrated by massive parallel 16S rRNA gene sequencing. BMC Microbiol. 9:210. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-9-210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson, K. S., S. E. Dowd, J. S. Suchodolski, I. S. Middelbos, B. M. Vester, K. A. Barry, K. E. Nelson, M. Torralba, B. Henrissat, P. M. Coutinho, . et al. 2011. Phylogenetic and gene-centric metagenomics of the canine intestinal microbiome reveals similarities with humans and mice. ISME J. 5:639–649. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2010.162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson, K. S., C. M. Grieshop, E. A. Flickinger, L. L. Bauer, J. Chow, B. W. Wolf, K. A. Garleb, and G. C. Fahey Jr. 2002. Fructooligosaccharides and Lactobacillus acidophilus modify gut microbial populations, total tract nutrient digestibilities and fecal protein catabolite concentrations in healthy adult dogs. J. Nutr. 132:3721–3731. doi: 10.1093/jn/132.12.3721 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tachon, S., J. Zhou, M. Keenan, R. Martin, and M. L. Marco. . 2013. The intestinal microbiota in aged mice is modulated by dietary resistant starch and correlated with improvements in host responses. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 83:299–309. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2012.01475.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thivend, P., M. Christiane, and A. Guilbot. . 1972. Determination of starch with glucoamylase. Methods Carbohydr. Chem. 6:100–105. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-746206-6.50021-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Verlinden, A., M. Hesta, J. M. Hermans, and G. P. Janssens. . 2006. The effects of inulin supplementation of diets with or without hydrolysed protein sources on digestibility, faecal characteristics, haematology and immunoglobulins in dogs. Br. J. Nutr. 96:936–944. doi: 10.1017/bjn20061912 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vickers, R. J., G. D. Sunvold, R. L. Kelley, and G. A. Reinhart. . 2001. Comparison of fermentation of selected fructooligosaccharides and other fiber substrates by canine colonic microflora. Am. J. Vet. Res. 62:609–615. doi: 10.2460/ajvr.2001.62.609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Von Englehardt, W., K. Rönnau, G. Rechkemmer, and T. Sakata. . 1989. Absorption of short-chain fatty acids and their role in the hindgut of monogastric animals. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 23:43–53. doi: 10.1016/0377-8401(89)90088-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Walker, A. W., J. Ince, S. H. Duncan, L. M. Webster, G. Holtrop, X. Ze, D. Brown, M. D. Stares, P. Scott, A. Bergerat, . et al. 2011. Dominant and diet-responsive groups of bacteria within the human colonic microbiota. ISME J. 5:220–230. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2010.118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ze, X., S. H. Duncan, P. Louis, and H. J. Flint. . 2012. Ruminococcus bromii is a keystone species for the degradation of resistant starch in the human colon. ISME J. 6:1535–1543. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2012.4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zentek, J., B. Marquart, T. Pietrzak, O. Ballèvre, and F. Rochat. . 2003. Dietary effects on bifidobacteria and Clostridium perfringens in the canine intestinal tract. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. (Berl). 87:397–407. doi: 10.1046/j.0931-2439.2003.00451.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, G., and B. R. Hamaker. . 2009. Slowly digestible starch: concept, mechanism, and proposed extended glycemic index. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 49:852–867. doi: 10.1080/10408390903372466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]