Abstract

Cull dairy cows contribute almost 10% of national beef production in the United States. However, different factors throughout the life of dairy cows affect their weight and overall body condition as well as carcass traits, and consequently affect their market price. Therefore, the objectives of this study were: (1) to assess relationships between price ratio and carcass merit of cull dairy cows sold through several sites of an auction market and (2) to investigate the effect of animal life history events and live weight on sale barn price (BP) and price ratio (as a measure of relative price), as an indicator of carcass merit. Data from 4 dairy operations included 3,602 cull dairy cow records during the period of 2015 to 2019. Life history events data were collected from each dairy operation through Dairy Comp software; live weight and price were obtained periodically from the auction market, and the carcass data were provided by a local packing plant. Cow price in dollars per unit of live weight ($/cwt) and price ratio were the 2 outcome variables used in the analyses. Price ratio was created aiming to remove seasonality effects from BP (BP divided by the national average price for its respective month and year of sale). The association between price ratio and carcass merit traits was investigated using canonical correlation analysis, and the effect of life history events on both BP and price ratio was inferred using a multiple linear regression technique. More than 70% of the cows were culled in the first 3 lactations, with an average live weight of 701.5 kg, carcass weight of 325 kg, and dressing percentage of 46.3%. On average, cull cows were sold at $57.0/cwt during the period considered. The canonical correlation between price ratio and carcass merit traits was 0.76, indicating that price ratio reflected carcass merit of cull cows. Later lactations led to lower BP compared with cows culled during the first 2 lactations. Injury, and leg and feet problems negatively affected BP. Productive variables demonstrated that the greater milk production might lead to lower cow prices. A large variation between farms was also noted. In conclusion, price ratio was a good indicator of carcass merit of cull cows, and life history events significantly affected sale BP and carcass merit of cull cows sold through auction markets.

Keywords: carcass merit, cow carcass, cow price, cull dairy cows, dairy beef

Introduction

In the United States, around 27% to 37% of dairy cows are removed from dairy herds every year (USDA, 2018; Stojkov et al., 2020). The most common culling reasons are reproductive failure, low milk production, and udder disease (Hadley et al., 2002; Weigel et al., 2003). A number of studies (Beaudeau et al., 1996; Bascom and Young, 1998; De Vries et al., 2010) have reported reproductive failure as the primary reason for culling. According to the last report of Health and Management Practices on U.S. Dairy Operations (USDA, 2018), 21.2% of dairy cows were removed due to infertility. However, often a dairy cow is culled for more than 1 reason (Pinedo et al., 2010) and, consequently, the cull cow category includes a large variation in live animal characteristics, such as lactation stage, maturity, body condition score, health status, and parity (Vestergaard et al., 2007; Gallo et al., 2017). Thus, dairy cows are a category with large variability in carcass technological characteristics and, potentially, in the final meat quality attributes (Vestergaard et al., 2007).

Once a dairy cow is no longer biologically or economically able to produce milk, it becomes a beef cow. In 2018, a total of 3.2 million dairy cows entered the food chain, accounting for almost 10% of domestically produced beef in the United States at federally inspected plants; thus, making the dairy sector an essential contributor to the beef industry (USDA, 2019). In some European countries, meat originating from cull dairy cows can represent more than 50% of the beef consumed (Bazzoli et al., 2014). The sale of cull dairy cows accounts for a significant share of the total monetary returns of dairy herds (between 5% and 10%); therefore, dairy farmers should also consider their role as beef producers and aim to market their dairy cows in ways that maximize cow value (Gallo et al., 2017).

However, research considering the importance of dairy cows as a beef source is scarce. Also, the majority of studies on cull dairy cows were undertaken to evaluate feeding strategies (Vestergaard et al., 2007; Lee et al., 2009; Therkildsen et al., 2011; Lowe et al., 2012). As such, very little is known about the associations between animal life events, price and carcass traits of cull dairy cows, especially in the United States (Bazzoli et al., 2014; Adamczyk et al., 2017; Gallo et al., 2017).

Some previous studies have focused on preharvest factors such as live animal characteristics, age, farm and seasonality (Bazzoli et al., 2014; Gallo et al., 2017), and their effect on price and carcass quality traits of dairy cows. Seegers et al. (1998) quantified the effect of parity, stage of lactation, and culling reason on the commercial carcass weight of French Holstein cows, but information on this topic remains really limited. Moreover, the current dairy production system often overlooks the importance of strategically marketing cull dairy cows for beef production (Vestergaard et al., 2007). Thereby, management, culling, and marketing of dairy cows should consider life event factors in an effort to optimize body condition, price, and carcass quality. Therefore, this study aimed to: (1) assess the relationships between carcass merit and sale barn price (BP) and (2) investigate the effect of animal life history events and live weight on price, as an indicator of carcass merit of cull dairy cows sold through an auction market.

Materials and Methods

Animal care and use committee approval was not obtained for the present study as all data were acquired from a preexisting database without our involvement in animal management or marketing.

Data description

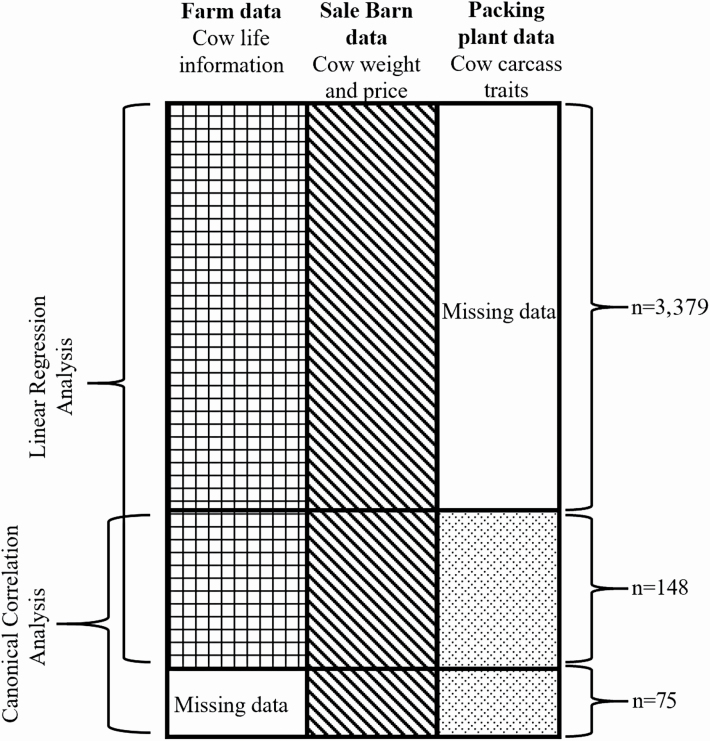

Data of Holstein cull dairy cows from 2015 to 2019 were provided by 4 dairy farms, 1 market agency with 4 auction barn locations through which cows were sold, and 1 meat packing plant, all located in Wisconsin. The initial data included 3,833 observations of cull dairy cows with individual data for life history events, live weight, and sale BP. Information on carcass traits was also available only for 223 cows obtained from 2018 to 2019. The overall structure of the data from these 3 different sources of information—dairy farms, sale barn, and packing plant—is depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Overall structure of the dataset, including information from farm, sale barn and packing plant. As indicated in this figure, the CCA was applied to a section of the data set with 223 observations containing the sale barn and packing plant components. Then, later, a multiple linear regression analysis was applied to the section of the data set containing 3,379 observations from farm and sale barn.

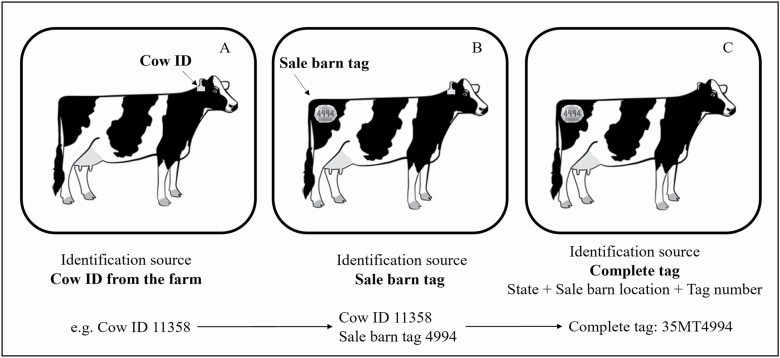

The tracking method used to trace each animal from the farm to the packing plant was the farm animal identification number followed by the sale barn back tag, and later by the complete tag from the packing plant (Figure 2). When the cow left the farm, the producer recorded the animal ID and the respective back tag that the cow received (a 4-digit sticker adhered to the back of each cow), which was provided by the sale barn. The back tag was then the animal identification used to identify and track the cows as they entered the sale barn, went through auction, and departed the sale barn for the packing plant.

Figure 2.

Tracking system used for traceability of a cull dairy cow from the farm to the packing plant. (A) At the farm, the identification source was the cow ID. When the cow was culled and ready to leave the farm, the cow received (B) a sale barn back tag that was matched with the cow ID. During marketing, the identification source was the back tag. When the cow was sent to the packing plant, the back tag was incorporated to (C) a complete tag ID, which was a combination of state, code for sale barn location where the animal was marketed, and the individual tag number of the cow.

At the packing plant, a complete tag was generated using the back tag number and identifiers for the sale barn location and the state, as described in Figure 2. The back tag of each cows was used to link all the data sources, then used to trace each cow individually and to build the whole database, combining information from farms, sale barn, and meat packing plant. This method was used from 2018 to 2019 with only 1 meat packing plant participating in the present study. Since the auction markets have multiple buyers, we restricted our study to those animals ultimately sold to the participating meat packing plant, and for which we were able to obtain complete information (from farm to the carcass).

The data provided by the farms were collected from the Dairy Comp software, which contained information on production, reproduction, health, and culling reasons (Table 1) for each individual animal, as well as their unique identification (ID) number. The Dairy Comp 305 database also provided variables that were calculated internally by the software, such as projected 305-d mature equivalent milk production (305ME), projected 305-d milk production (305M), and fat corrected milk (FCM). In addition, the 305-d mature equivalent milk production (ME305) is calculated externally, usually by the processing center.

Table 1.

Description of observed variables of dairy cows from 4 dairy operations in Wisconsin

| Variables | Description | Unit | Levels |

|---|---|---|---|

| DIM | Days in milk | d | — |

| DOPN | Days open | d | — |

| DDRY | Days dry | d | — |

| CINT | Calving interval | d | — |

| TOTM | Total milk production for current lactation | kg | — |

| TOTP | Total protein production for current lactation | kg | — |

| TOTF | Total fat production for current lactation | kg | — |

| PTOTM | Total milk production for previous lactation | kg | — |

| PTOTP | Total protein production for previous lactation | kg | — |

| PTOTF | Total fat production for previous lactation | kg | — |

| 305M | Dairy Comp internal projected 305-d milk production | kg | — |

| 305ME | Dairy Comp projected 305ME | kg | — |

| ME305 | 305ME | kg | — |

| PDIM | Days in milk for previous lactation | d | — |

| PDOPN | Days open for previous lactation | d | — |

| FCM1 | Fat corrected milk for lactation 1 | kg | — |

| 305ME1 | 305 d mature herd equivalent for lactation 1 | kg | — |

| FCM2 | Fat corrected milk for lactation 2 | kg | — |

| 305ME2 | 305 d mature herd equivalent for lactation 2 | kg | — |

| LACT | Lactation number | — | 7 |

| EASE | Calving ease score | — | 2 |

| MAST | Lifetime Mastitis | — | 3 |

| Culling | Culling reason | — | 7 |

| Month | Month of sale | — | 12 |

| Year | Year of sale | — | 4 |

| Farm | Farm of origin | — | 4 |

| Weight | Live weight | kg | — |

| BP | Price paid per 100 lb (45.34 kg) of live weight | $ | — |

| price ratio | BP divided by the national average cow price ($/cwt) for the respective month and year of sale | $ | — |

| Carcasswt | Carcass weight | kg | — |

| Dressing | Dressing percentage | % | — |

| Grade | Paid grade for carcass | — | 9 |

| Maturity | Animal maturity | — | 2 |

| Trim | Score of carcass trimming loss weight | — | 2 |

The data provided by the sale barn were obtained from reports prepared every 6 mo, which contained back tag number, live animal weight (kg), sale BP ($/cwt dollars paid per 100 lb of live weight, where 100 lb is equal to 45.34 kg), total value ($/head), and date of sale. An additional variable was created, price ratio, which was calculated by dividing the cow sale BP ($/cwt) by the national cow price average ($/cwt) for the respective month and year of sale. The national cow price average provided by the National Agricultural Statistics Service does not distinguish beef and dairy cow prices, and was obtained from NASS (2020). Price ratio was created aiming to normalize seasonal cow price fluctuations and to assess whether the cows were sold above or below the national average.

The data provided by the meat packing plant contained animal complete ID tag (Figure 2), hot carcass weight (kg), grade (internal grading system, from 9: highest grade, to 1: lowest grade), score of carcass trimming weight losses (0 for no trimming, 1 for trimmed carcass), dressing percentage, and carcass maturity score (under or over 30 mo); these variables were jointly used as an indicator of carcass merit.

Data editing and descriptive analysis

First, data visualization and descriptive analyses were performed to assess the distribution and inconsistencies in the data set using the R package “DataExplorer” (Cui, 2020). Health (lameness, ketosis, and displaced abomasum) and milk production (projected 305-d milk mature herd and FCM for lactations 3 or greater, both of which are commonly considered to indicate milk production and quality) variables with 55% or more missing information were removed from the data set because of insufficient data for predictions. Additionally, cows with missing information for live weight and sale BP were removed from the data set.

The distributions of the variables were examined using histograms and box plots. For categorical variables, neighboring categories with low counts were combined into single categories. Descriptive statistics were used to assist in the category development and were implemented as follows. Lactation number was categorized as 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6+ lactations. Calving ease was edited into 2 categories, 1 (none or little assistance) and 2 (requiring further assistance such as mechanical or surgical). Lifetime mastitis was categorized as 0 (no mastitis events), 1 (1 to 3 events), and 2 (4 or more mastitis events). The events of interest for culling were categorized into 7 reasons: “low productivity,” “breeding failure,” “injury,” “mastitis and udder,” “abort,” “feet and leg problems,” and “others” (DRMS, 2014). Maturity was categorized as under or over 30 mo of age. Trimming loss was categorized as 0 (for carcasses with no trimming) and 1 (for trimmed carcass).

Data editing and graphical visualization were conducted in R (R Core Team, 2020) with the dplyr (Wickham et al., 2020), tidyr (Wickham and Henry, 2020), and the ggplot2 (Wickham, 2016) packages. After the cleaning and editing procedure, the final data set contained a total of 3,379 cows with farm and sale barn information; 148 cows with farm, sale barn, and packing plant complete information; and 75 cows with only sale barn and packing plant information. Altogether, the data set comprised 3,602 cows with 29 variables. A detailed descriptive analysis was performed for each continuous variable in the data set.

Canonical correlation analysis

Canonical correlation analysis (CCA) is a useful technique to investigate and quantify the associations between two sets of variables, usually called variates. CCA aims to maximize the association between low-dimensional projections of the 2 sets of variables based on linear combinations (Härdle and Simar, 2019). CCA was used to examine the relationship between price ratio and carcass merit traits aiming to determine whether price ratio could be used as an indicator of carcass merit for further regression analysis to investigate the effect of life history events on carcass merit of cull dairy cows. Particularly, loadings and cross-loadings from the CCA were used to identify carcass traits that have high correlation with the canonical variate associated with the sale parameters, in this case, price ratio.

Prior to the CCA, a Pearson correlation analysis was performed for each pair of variables. Then, CCA was performed using the R package “Yacca” (Butts, 2018), with the first variate represented by one single variable, i.e., price ratio, while the second variate included the carcass merit traits. Initial assessment and data visualization demonstrated some difference between farms, so the data set was centered within each farm before performing CCA. Additionally, the ordinal variables grade, trim, and maturity entered the CCA as quantitative variables, as an approximation to enable the use of this information. The CCA was conducted as follows: Let θT = (live weight, carcass weight, dressing percentage, carcass grade, maturity, trim) be the 6 × 1 vector of variables associated with carcass merit, and η = (price ratio) be the 1 × 1 vector of price ratio. The variance–covariance matrix of θ and η can be expressed as

where , , and , with and of full rank. CCA searched for vectors a and b , such that the correlation between the linear combinations and was maximized. Such correlation, given by the expression

can be maximized with generalized eigenvalues (Moraes et al., 2015).

Multiple linear regression analysis

Multiple linear regression analysis was used to investigate the effect of life history events on sale BP ($/cwt) and price ratio of cull dairy cows. Price ratio was used as an indicator of carcass merit, thus aiming to identify which life events were associated with carcass merit. Second, BP was used to explore seasonality and life events associated with the price paid per unit of body weight of cull dairy cows. All statistical analyses were performed with the statistical software R (R Core Team, 2020).

Model selection

Multiple linear regression models were fitted separately for BP and price ratio, using the R package stats (R Core Team, 2020). The remaining variables (Table 1) were included in the model as potential explanatory variables (). The model containing all explanatory variables was considered the full model. Subsequently, the full model was submitted to a variable selection approach using a genetic algorithm search via the R package glmulti (Calcagno, 2019). The 3 model selection criteria considered were Akaike information criteria, Bayesian information criterion, and adjusted R2.

The final model fitted for BP was

where is the overall intercept of the model, and e is a residual term, assumed independent and normally distributed with mean zero and variance , i.e., . The model included also categorical and continuous covariables. In the group of categorical variables, lactation is the effect of lactation number (LACT), culling is the effect of each culling reason, farm is the effect of farm, month is the effect of month of the year, and year is the effect of years. For the continuous variables, DDRY is the effect of days dry, TOTM is the effect of total milk production for the current lactation, PTOTP is the effect of total milk solids production for the previous lactation, 305M is the effect of 305 d milk production, FCM 1 and 2 are the effects of FCM for the first and second lactation, 305M 1 and 2 are the effects of 305 d mature herd equivalent for the first and second lactation, and weight is the effect of live body weight. The parameters b1, …, b9 are regression slopes for each of the continuous variables.

For price ratio, the final model fitted was

where is the overall intercept of the model; lactation, culling, farm, month, and year are the effects of categorical variables, as described before; DOPN is the effect of days open; ME305 is the effect of projected 305ME; weight is the effect of body weight, all included as continuous covariables in the model, with their respective regression slopes b1, …, b3; and e is a residual term, assumed , i.e., .

Measures of influence, Pearson’s correlation, and variance inflation factor

Influential observations were assessed using Cook’s distance, Studentized residuals and leverage measurements with the R package Olsrr (Hebbali, 2020). Pearson’s correlation and the variance inflation factor (VIF) were used to investigate issues of collinearity among explanatory variables. The VIF values for BP final model ranged from 1.12 to 4.23, and for price ratio the VIF values ranged from 1.51 to 2.89. There were no values above 5, thus further investigation was not needed.

Predictive ability

The data set was split into training and testing (75% and 25% of the data, respectively), with the training set used to build the model (including variable selection and parameter estimation) and the testing set used to evaluate model performance. The predictive ability of each model was assessed in terms of prediction root mean square error, coefficient of determination (R2), and mean absolute error (MAE) on the testing set. The data splitting, model tuning, and assessment of model predictive ability were performed using the “caret” package (Kuhn, 2020).

Results and Discussion

Descriptive analysis

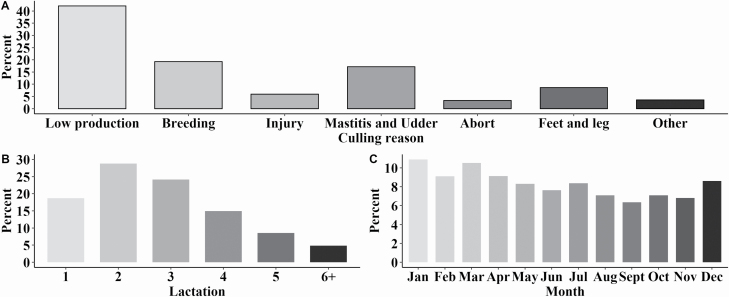

The 3 most frequent culling reasons were low production, breeding problems, and mastitis and udder problems (Figure 3). Our findings align with the literature. Some previous studies have investigated reasons for culling. For example, Pinedo et al. (2010) reported the primary disposal codes were death, followed by reproduction, injury/other, low production, and mastitis for replacement of cows. Similarly, Bascom and Young (1998) reported reproduction, mastitis, and low production. Hadley et al. (2006) described injury/other, reproduction, and low production as the most common reasons for culling across all 10 states evaluated. According to the National Animal Health Monitoring System (NAHMS; USDA, 2018) the most common culling reasons are infertility, low production, and mastitis.

Figure 3.

Percentage of dairy cows culled by (A) culling reason, (B) lactation number, and (C) month of sale.

In our study, more than 70% of the cows were culled during their first lactations, with 18.7% culled in the first lactation, 28.8% in the second and 24.1% in the third lactation (Figure 3). Similarly, the NAHMS (USDA, 2018) report, which represents 80.5% of U.S. dairy operations, found that 22.2% of the cows were removed from the herd during the first lactation and 51.9% were removed between the second and fourth lactations.

The month of January had the highest culling percentage, followed by March and February. In contrast, September was the month with the lowest percentage of cows culled, followed by November and August (Figure 3). Bazzoli et al. (2014) reported that in northern Italy the months with highest culling percentage were October, November, and December, which also coincide with low carcass price (€/kg) and lowest carcass value (€/head).

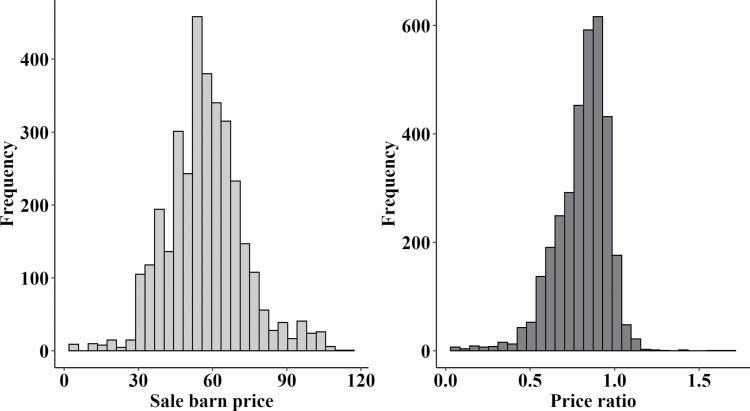

The frequency distribution of BP and price ratio is shown in Figure 4. The price ratio for most of the cows was <1.0 (Figure 4). Cull cows were sold, on average, at $57/cwt from 2015 to 2019 (Table 2). The mean of price ratio indicated that cull cows considered in this study were sold at a price which was less than the national average (Table 2). The data collected from 2018 to 2019 also indicated the BP paid for cull dairy cows was $51.6/cwt (Table 3). Overall, the average live weight was 732.4 kg (Table 2). Specifically, for the 223 cows with carcass information, the average live weight was 701.5 kg (Table 3). In addition, their average dressing percent was 46.3%, and carcass weight was 325 kg (Table 3).

Figure 4.

Frequency distribution for sale BP ($/cwt) and price ratio.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics of life history events and marketing of 3,397 dairy cows culled from 4 dairy operations in Wisconsin from 2015 to 2019

| Variables | n | Mean | SD | CV |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Current lactation 1 | ||||

| DIM, d | 3,379 | 253.4 | 141.2 | 55.7 |

| DOPN, d | 3,379 | 205.1 | 151.7 | 74.0 |

| DDRY, d | 2,742 | 53.8 | 12.0 | 22.3 |

| CINT, d | 2,746 | 386.6 | 50.1 | 13.0 |

| TOTM, kg | 3,237 | 10,238.4 | 5,991.6 | 58.5 |

| TOTP, kg | 3,205 | 327.3 | 190.6 | 58.2 |

| TOTF, kg | 3,205 | 409.8 | 2,34.8 | 57.3 |

| 305M, kg | 3,195 | 11,573.8 | 2,748.8 | 23.8 |

| 305ME, kg | 3,195 | 13,004.3 | 2,839.3 | 21.8 |

| ME305, kg | 3,245 | 12,711.1 | 3,046.3 | 24.0 |

| Previous lactation 1 | ||||

| PTOTM, kg | 2,746 | 13,519.9 | 3,303.8 | 24.4 |

| PTOTP, kg | 2,746 | 430 | 98.5 | 22.9 |

| PTOTF, kg | 2,746 | 530.8 | 127.0 | 23.9 |

| PDIM, d | 2,744 | 332.8 | 48.8 | 14.7 |

| PDOPN, d | 2,746 | 110.3 | 49.2 | 44.7 |

| First and second lactation 1 | ||||

| FCM1, kg | 2,995 | 33.0 | 9.9 | 29.9 |

| 305ME1, kg | 2,894 | 11,979.0 | 1,676.6 | 14.0 |

| FCM2, kg | 2,442 | 47.8 | 12.8 | 26.8 |

| 305ME2, kg | 2,382 | 12,585.8 | 1,616.6 | 12.8 |

| Marketing 2 | ||||

| weight, kg | 3,379 | 732.4 | 118.0 | 16.1 |

| BP, $/cwt | 3,379 | 57 | 15.6 | 27.3 |

| Price ratio | 3,379 | 0.81 | 0.16 | 19.3 |

n: number of observations, CV: coefficient of variation (%).

1Data were obtained from Dairy Comp.

2Data were obtained from the marketing agency.

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics of sale BP, price ratio, and carcass merit traits of 223 dairy cows sold through livestock sale barn from 2018 to 2019 in Wisconsin

| Variables1 | Mean | SD | CV |

|---|---|---|---|

| BP, $/cwt | 51.6 | 10.7 | 20.8 |

| Price ratio | 0.82 | 0.16 | 19.0 |

| Weight, kg | 701.5 | 123.2 | 17.6 |

| Carcasswt, kg | 325.0 | 68.9 | 21.2 |

| Dressing, % | 46.3 | 4.9 | 10.6 |

CV, coefficient of variation (%).

1BP: sale BP paid in dollars per 100 lb. (or 45.34 kg) of live weight ($/cwt); price ratio: cow sale BP ($/cwt) divided by the national cow price average ($/cwt) for the respective month and year of sale; weight: live weight measured at sale barn; carcasswt: carcass weight in kilograms; dressing: carcass dressing percentage.

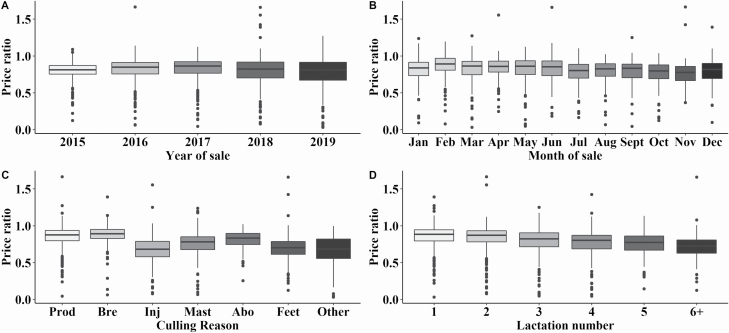

The distributions of price ratio by culling reasons, month, year, and LACT are presented in Figure 5. The lowest price ratios were observed for cows culled due to injury or leg and feet problems. On the other hand, the highest price ratios were observed for cows culled due to breeding and low production reasons. As expected, price ratio was similar across months, since the seasonality effect was removed once the BP ($/cwt) was divided by the national average price by month and year. Nonetheless, there were differences as cows sold in November had lower prices. This pattern might be explained by the fact that late Fall includes the peak months for beef cow harvest, so supply of harvestable cows is at the annual high point. Cull cows removed from the herd in later lactations had lower price ratio compared with cows culled in the first 2 lactations. This pattern was expected as the dairy cow is transitioning to a mature animal, thus receiving lower prices for beef since the meat quality of mature animals is expected to be inferior to that of younger animals.

Figure 5.

Distribution of price ratio sorted by (A) year of sale, (B) month of sale, (C) culling reason (Prod: low production, Bre: breeding problem, Inj: injury, Mast: Mastitis and udder problem, Abo: abort, Feet: Leg and feet problem, Other: Other reasons), (D) lactation number.

Prior to the CCA, the Pearson correlation coefficients were calculated for each pair of the respective variables (Table 4). The Pearson correlation indicated a strong positive correlation between BP and price ratio (0.91, P < 0.001) and grade (0.6, P < 0.001). There was a moderate positive correlation between BP and body weight (0.37, P < 0.001), carcass weight (0.53, P < 0.001), dressing (0.44, P < 0.001), and maturity (0.31, P < 0.001). Price ratio showed stronger correlations with body weight (0.41, P < 0.001) and carcass traits (from 0.40 to 0.66, P < 0.001) compared with BP. Trimming losses indicate the amount of tissue the carcass lost due to bruising, wounds or injury, which can also be used as an indicator of the animal condition (body and health). Trimming losses showed weak negative correlations with all variables, but especially with dressing percent (−0.31, P < 0.001) and price ratio (−0.28, P < 0.001), which indicate that the carcasses with high trimming losses were marketed for less. These findings may indicate that during marketing these cows could have low body condition score or some visual defect that helped the buyer to identify the poor carcass yield from these animals, thus paying lower prices. Interestingly, there was no correlation between dressing percentage and cow live weight.

Table 4.

Pearson correlation coefficients between sale BP, price ratio, and carcass characteristics variables1

| Price ratio | Weight | Carcasswt | Dressing | Maturity | Grade | Trim | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BP | 0.91*** | 0.377*** | 0.536*** | 0.445*** | −0.313*** | 0.608*** | −0.258*** |

| Price ratio | 0.407*** | 0.571*** | 0.472*** | −0.397*** | 0.662*** | −0.275*** | |

| Weight | 0.876*** | 0.068 | 0.224*** | 0.186** | −0.121* | ||

| Carcasswt | 0.534*** | 0.069 | 0.465*** | −0.254*** | |||

| Dressing | −0.277*** | 0.661*** | −0.306*** | ||||

| Maturity | −0.453*** | 0.141* | |||||

| Grade | −0.24*** |

1BP: sale barn cow price in dollars paid per 100 lb. (or 45.34 kg) of live weight ($/cwt); price ratio: cow sale BP ($/cwt) divided by the national cow price average ($/cwt) for the respective month and year of sale; weight: cow live weight measured at sale barn; carcasswt: carcass weight in kilograms; dressing: carcass dressing percentage; maturity: carcass maturity; grade: carcass grade assigned by meat packing plant; trim: carcass trimmed weight loss. Significance codes: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

The live cow categories reported by the USDA Agricultural Marketing Service are Premium White, Breaker, Boner, and Cutter. However, each packing plant has its own internal classification system, which may be the breakdown of the categories mentioned above. At sale barn auctions, visual estimations of dressing percent and red meat percentage in the carcass are the 2 main criteria used to determine the market category of cull cows and, consequently, the final price (Moreira et al., 2020). Consistent with this visual estimation strategy, packing plant carcass grade showed a small positive correlation with carcass weight (0.19, P < 0.01) and much stronger positive correlations with BP (0.61, P < 0.001), price ratio (0.66, P < 0.001), and dressing percent (0.66, P < 0.001).

Canonical correlation analysis

The data set of cull dairy cows with carcass traits contained only 223 observations, thus providing limited information for prediction. Thus, a CCA was used to investigate the degree of association between price ratio and carcass merit traits. More specifically, the CCA aimed to assess whether price ratio could be used as an indicator of carcass merit. In addition, the loadings and cross-loadings from the CCA were used to identify carcass merit traits that have higher correlation with the canonical variate associated with the sale parameters, in this case, price ratio.

The number of canonical correlations extracted from the analysis is always equal to the number of variables in the smaller set, in this case price ratio. Then, the canonical correlation between the 2 variates (carcass traits and price ratio) was 0.76 (Table 5). This correlation suggests that price ratio is highly correlated with carcass merit traits and, therefore, indicates that price ratio could be used as a satisfactory indicator of carcass merit for further analysis.

Table 5.

Canonical coefficients, loadings, correlation, and aggregate redundancy coefficient for the first canonical variates of the price ratio and carcass merit characteristics of 223 cull dairy cows1

| Variables2 | Loadings | Cross-loadings | Correlation | ARC |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ƞ | ||||

| Price ratio | 0.761 | 0.216 | ||

| θ | ||||

| Livewt | 0.393 | 0.299 | 0.579 | |

| Carcasswt | 0.680 | 0.517 | ||

| Dressing | 0.662 | 0.503 | ||

| Grade | 0.851 | 0.647 | ||

| Maturity | 0.580 | 0.441 | ||

| Trim | −0.355 | −0.270 |

1 Ƞ = vector of price ratio; θ = vector of carcass merit characteristics. Canonical loadings and cross-loadings represent the correlation between each individual variable with its own canonical variate. Aggregate redundancy coefficient (ARC) describes the amount of variance in the vector Ƞ explained by the vector θ, and the amount of variance in the vector θ explained by the vector Ƞ.

2Price ratio: cow sale BP ($/cwt) divided by the national cow price average ($/cwt) for the respective month and year of sale; livewt: cow live weight (kg); carcasswt: carcass weight (kg); dressing: carcass dressing percentage (%); grade: carcass grade assigned by meat packing plant; maturity: carcass maturity; trim: carcass trimmed weight loss.

Canonical loadings of the carcass merit traits were higher for grade, carcass weight, and dressing percent (Table 5), suggesting that these carcass variables were the most important components of the canonical variate associated with carcass merit. Similarly, the examination of the cross-loadings of the first canonical function suggested that grade, carcass weight, and dressing percent were, likewise, highly correlated with the canonical variate associated with sale parameters, i.e., price ratio. The coefficients for carcass trimming losses were negative, reflecting the perceived loss of carcass weight by buyers and their incorporation of this perception in live cow price. Similarly, live weight accounts for only a small proportion of the variation in price ratio.

The redundancy coefficient describes the amount of variance explained by the other canonical variate, these coefficients were 0.22 and 0.58 for the first and second canonical variate, respectively (Table 5). These findings indicated that the carcass merit traits were able to explain about 58% of the variance for price ratio. Therefore, the results from the CCA indicate that carcass merit traits and price ratio traits are highly correlated, meaning that price ratio could be used as an indicator of carcass merit for this data set.

Multiple linear regression analysis

BP and price ratio were the 2 outcome variables used for the multiple linear regression analysis. Estimates of the regression coefficients and least squares means for BP and price ratio are presented in Tables 6, 7, and 8.

Table 6.

Coefficient estimates, standard error (SE), F-statistics, and P-value of the regression of sale BP ($/cwt) and price ratio on the continuous explanatory variables for 3,379 cull dairy cows

| Variables1 | Estimates | SE | F-statistics | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sale BP ($/cwt)2 | ||||

| DDRY | −0.0425 | 0.0157 | 7.31 | 0.0069 |

| TOTM | 0.0002 | 0.0001 | 10.07 | 0.0015 |

| PTOTP | −0.0078 | 0.0023 | 11.99 | 0.0005 |

| 305M | −0.0003 | 0.0001 | 5.36 | 0.0207 |

| FCM1 | −0.0302 | 0.0399 | 0.57 | 0.4490 |

| FCM2 | −0.0045 | 0.0258 | 0.03 | 0.8624 |

| 305ME1 | −0.0001 | 0.0002 | 0.42 | 0.5159 |

| 305ME2 | −0.0003 | 0.0002 | 1.59 | 0.2074 |

| Weight | 0.0364 | 0.0021 | 298.70 | < 2e−16 |

| Price ratio3 | ||||

| DOPN | 0.0001 | 2.11e−05 | 15.06 | 0.0001 |

| ME305 | −0.000003 | 8.51e−07 | 14.31 | 0.0002 |

| weight | 0.0005 | 2.14e−05 | 517.74 | < 2e−16 |

1Refer to Table 1 for variable definitions.

2Sale BP ($/cwt): price paid in dollars per 100 lb. (or 45.34 kg) of live weight.

3Price ratio: cow sale BP ($/cwt) divided by the national cow price average ($/cwt) for the respective month and year of sale.

Table 7.

Least squares mean (LSM), standard error (SE), F-value, and P-value of the regression of sale BP ($/cwt) on the categorical variables for 3,379 cull dairy cows

| Variables | Class | LSM | SE | Variables | Class | LSM | SE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 55 | 0.851 | 2 | 59.8 | 0.513 | ||

| Farm | 2 | 59 | 0.435 | Lactation | 3 | 57.4 | 0.478 |

| (F = 244.5; P < 2.2e−16) | 3 | 56.5 | 0.952 | (F = 46.5; P < 2.2e−16) | 4 | 56.8 | 0.543 |

| 4 | 54.8 | 0.377 | 5 | 54.8 | 0.648 | ||

| Jan | 54.2 | 0.705 | 6+ | 52.8 | 0.812 | ||

| Feb | 59.5 | 0.75 | PRO | 57.6 | 0.421 | ||

| Mar | 61.3 | 0.73 | BRE | 58.8 | 0.581 | ||

| Apr | 62.3 | 0.699 | Culling1 | INJ | 51.9 | 0.904 | |

| Month | May | 62.5 | 0.753 | (F = 53.8; P < 2.2e−16) | MAST | 56.8 | 0.527 |

| (F = 133.9; P < 2.2e−16) | Jun | 60.8 | 0.771 | ABO | 58.2 | 1.162 | |

| Jul | 62.8 | 0.729 | FEET | 55.4 | 0.67 | ||

| Aug | 60.7 | 0.763 | OTHER | 55.4 | 1.018 | ||

| Sept | 55.5 | 0.807 | 2015 | 80.3 | 0.773 | ||

| Oct | 50.2 | 0.718 | Year | 2016 | 58.5 | 0.569 | |

| Nov | 43.9 | 0.747 | (F = 643.5; P < 2.2e−16) | 2017 | 53.4 | 0.569 | |

| Dec | 42.1 | 0.681 | 2018 | 47.5 | 0.48 | ||

| 2019 | 47.8 | 0.561 |

1PRO: low production, BRE: breeding, INJ: injury, MAST: mastitis and udder problems, ABO: abort, FEET: feet and leg problems, OTHER: other reasons.

Table 8.

Least squares mean (LSM), SE, F-value, and P-value of the regression of price ratio on the categorical variables for 3,379 cull dairy cows

| Variables | Class | LSM | SE | Variables | Class | LSM | SE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.764 | 0.00873 | 1 | 0.842 | 0.00631 | ||

| Farm | 2 | 0.805 | 0.00446 | Lactation | 2 | 0.804 | 0.00536 |

| (F = 308.7; P < 2.2e−16) | 3 | 0.716 | 0.01021 | (F = 82.8; P < 2.2e−16) | 3 | 0.762 | 0.00529 |

| 4 | 0.736 | 0.00411 | 4 | 0.739 | 0.00601 | ||

| 5 | 0.716 | 0.00743 | |||||

| Jan | 0.754 | 0.00741 | 6+ | 0.669 | 0.00945 | ||

| Feb | 0.769 | 0.00785 | PRO | 0.792 | 0.00441 | ||

| Mar | 0.755 | 0.00735 | Culling1 | BRE | 0.793 | 0.00648 | |

| Apr | 0.776 | 0.00734 | (F = 122.5; P < 2.2e−16) | INJ | 0.676 | 0.00933 | |

| Month | May | 0.779 | 0.00759 | MAST | 0.772 | 0.00566 | |

| (F = 21; P < 2.2e−16) | Jun | 0.758 | 0.00783 | ABO | 0.785 | 0.01205 | |

| Jul | 0.755 | 0.00747 | FEET | 0.729 | 0.00725 | ||

| Aug | 0.757 | 0.00811 | OTHER | 0.74 | 0.0113 | ||

| Sept | 0.742 | 0.00838 | Year | 2015 | 0.767 | 0.00826 | |

| Oct | 0.751 | 0.00794 | (F = 9.4; P < 2.2e−16) | 2016 | 0.763 | 0.00593 | |

| Nov | 0.704 | 0.00799 | 2017 | 0.755 | 0.00582 | ||

| Dec | 0.736 | 0.00739 | 2018 | 0.751 | 0.00506 | ||

| 2019 | 0.741 | 0.00579 |

1PRO, low production; BRE, breeding; INJ, injury; MAST, mastitis and udder problems; ABO, abort; FEET, feet and leg problems; OTHER, other reasons.

Sale BP ($/cwt)

BP paid in dollars per hundred pounds ($/cwt) of live weight was used as one of the outcome variables for multiple linear regression, aiming to explore the potential effects of life history events and seasonality traits (month and year of culling) on BP. The identification of such productive traits as well as seasonality could help dairy farmers make better culling and marketing decision. In addition, such knowledge could aid farmers by improving their management practices to enhance the quality of cull cows and consequently increasing their revenue from cull dairy cows.

The variables in the final model for BP were LACT, culling reason (Culling), farm, month, year, DDRY, TOTM, PTOTP, 305M, fat corrected milk for the first (FCM1) and second lactation (FCM2), and 305-d mature equivalent milk production for the first (305ME1) and second lactation (305ME2), and body weight (Tables 6 and 7).

The variables DDRY and PTOTP had a small negative but statistically significant effect on BP (Table 6). The DDRY having a negative effect on BP could be explained by the fact that this phase is dedicated to support fetal calf growth, mammary gland development, minimize metabolic disorders, and optimize milk production for the next lactation; therefore, this suggests the dry period as a phase of high metabolic activity (Jaurena and Moorby, 2017). However, it is important to emphasize that cull cows are removed from the herd at different stages of lactation, which may help to explain the small effect of days dry. The variables for the current lactation may not be representative of the normal lactation cycle, when these values might be lower or higher than normal. These findings indicate that cull cows that had higher PTOTP received a lower BP at the auction market, which can be explained by the fact that these 2 production variables, DDRY and PTOTP, could also be related to tissue mobilization to supply the mammary gland during lactation and fetal growth (Schäff et al., 2013; Ruda et al., 2019), which have higher demand during early and mid-lactation (Andrew et al., 1994). Additionally, these variables can be associated with low value appearance of the cow, or some other biological trait recognizable as carcass or meat yield.

Body weight had a positive significant (P < 0.0001; Table 6) effect on BP. Heavier dairy cows received a slightly higher BP (per unit of weight) than lighter cows. Another reason for heavier cows having higher BP is that these animals could be marketed in better health, and not only higher body weight. As the Pearson’s correlation data have shown (Table 4), body weight is highly correlated with carcass weight, moderately correlated with BP and price ratio, but had lower correlation with variables that determine the final value of the carcass, grade and dressing percent.

Dairy cows that were culled in later lactations received a lower BP compared with cows culled at first lactations (Table 7). LACT is also an indicator of age, which is known to have a large effect on BP of animals for beef production (Bazzoli et al. 2014; Gallo et al. 2017). In this study, most of the cows (71.6%) were culled in the first 3 lactations, which coincides with 5 yr old or less (data not shown), thus indicating that these animals were culled relatively early in their productive life. Bazzoli et al. (2014) reported an average of 73 mo (6 yr) of age for Holstein–Friesian cull dairy cows from the northern region in Italy. However, Gallo et al. (2017) reported a slightly lower age than that reported by Bazzoli et al. (2014) for cows culled in the same province between 2003 and 2011. These findings agreed with the results from the present study, i.e., lower prices for older animals.

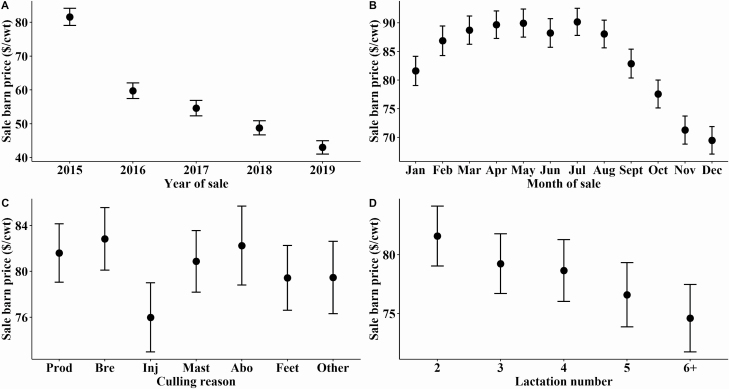

The culling reasons had a large effect on BP ($/cwt; Figure 6) and the 3 most detrimental culling reasons were injury, feet and leg problems, and Others ($51.9/cwt, $55.4/cwt, and $55.4/cwt, respectively). These culling reasons represent a difference of −$6.9/cwt to −$3.4/cwt compared with cows culled due to breeding problems ($58.8/cwt; Table 7), thus indicating a large discount on cows with visual defects. Health and visual defects are the 2 very important factors evaluated at live auctions, and often responsible for large discounts on market cows (Harris et al., 2017). Often, injury might be related with other problems such as low body condition score and lameness or leg problems; thin cows have higher incidence of lameness and are more susceptible to bruising, injury, and becoming downers during or after transportation (Ahola et al., 2011; Harris et al., 2018). Therefore, these cows receive large discounts, and they are marketed at lower prices due to their higher likelihood of loss before or after harvest.

Figure 6.

Least squares means and confidence intervals of sale BP for (A) year of sale, (B) month of sale, (C) culling reason (Prod: low production, Bre: breeding problem, Inj: injury, Mast: Mastitis and udder problem, Abo: abort, Feet: Leg and feet problem, Other: Other reasons), and (D) lactation number.

The farm of origin was another relevant variable affecting BP (Table 7). The farm effect could be capturing a combination of management, animal handling, housing, and milking facility differences among operations. These differences are also associated with the culling dynamic of each farm (Weigel et al., 2003), which can also influence the final cow BP.

The month of sale was also important to explain the BP ($/cwt) paid for cull cows (Figure 6). The months with the lowest BP paid for cull cows were December and November ($42.1/cwt and $43.9/cwt, respectively; Table 7). In fact, after July the BP declined drastically indicating that during the months of Fall cull cows were marketed at lower BP. On the other hand, the months with higher BP were July and May ($62.8/cwt and $62.5/cwt, respectively). Year has shown to also affect BP, which demonstrates that the BP paid for cull cows is following the price trends of the U.S. beef market throughout the years (Table 7). In 2015, the BP paid for market cows was higher, and since then the BP paid for these animals is declining even though the demand of these animals from the beef industry remains the same, or higher. Cattle prices were higher in 2015, indicating that the cow prices did follow the market trends (NASS, 2020).

The predictive performance for the multiple linear regression model of BP had an R2 of 0.75, an RSME of $7.6/cwt, and MAE of $5.8/cwt. These findings indicate that the final model was able to predict BP reasonably well although RSME and MAE are relatively high considering the differences previously mentioned. As far as we are aware, this is the first time that farm data of life history events has been used to predict BP of cull dairy cows sold through auction market. The prediction of BP can help dairy producers to forecast the best time to market their cull cows and which productive variables they should manage to improve cow condition and, consequently, cow value.

Price ratio

The variable price ratio was initially created aiming to remove the seasonality effect from BP ($/cwt) and to compare whether the prices paid for these animals were above (values higher than 1) or below (values lower than 1) national average. The notable finding of CCA indicated that price ratio was a good indicator of carcass merit and that this variable could be used to then investigate the productive traits associated with carcass merit of cull dairy cows. Thus, price ratio was used as one of the outcome variables for multiple linear regression aiming to explore the associations between life history events and carcass merit. More specifically, this analysis could identify the productive traits that the dairy producer could use to guide their decision on management and marketing of their cull cows.

The variables in the final model for price ratio were LACT, culling reasons (Culling), farm, month, year, DOPN, projected 305ME based on daily milk (ME305), and body weight (Tables 6 and 8). Days open (DOPN), which is the number of days a cow is not pregnant while lactating, varying from 90 to 120 d, had a small but statistically significant effect on price ratio (Table 6). Although during this period, the animals can experience negative energy balance, after peak of milk, the dairy cow starts to recover body reserves in addition to not being pregnant, and consequently not having the energy demand for fetal growth. Seegers et al. (1998) found that Holstein cows culled during early lactation did not lead to very low carcass weights because after 100 d, the dairy cow started to recover body weight.

Body weight had a small but statistically significant effect on price ratio, with heavier cows marketed at higher prices, closer to the national average, and with better carcass merit (Table 6). The small effect of body weight on price ratio was expected given its moderate Pearson correlation (Table 4) of 0.40 and lower correlations with carcass merit variables. Dressing percentage and grades are 2 indicators of carcass merit, thus suggesting that body weight alone explains a small portion of price ratio due to its lower association with carcass merit. Furthermore, heavier cows could also be associated with well-conditioned cows and, as a consequence, receiving higher prices. Gallo et al. (2017) reported that the increase observed in calving to culling interval improved all of the carcass traits, as well as the price per kilogram of carcass and the total value of carcasses.

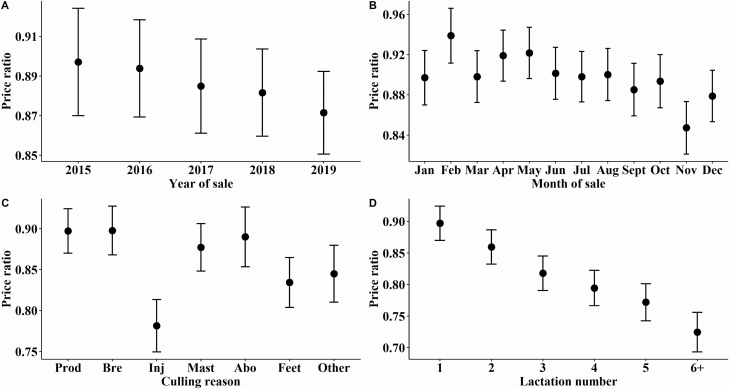

As similarly mentioned for BP, LACT also had a significant effect on price ratio (Table 8); price ratio decreased as LACT increased (Figure 7). While age was not quantified in the present study, LACT can be used as an indicator of age. Evaluating carcass data from northern Italy, Bazzoli et al. (2014) and Gallo et al. (2017) reported that age at culling had a significant effect on carcass weight, carcass price, and carcass value of culled cows. The maturity of animals sent to harvest is an important factor determining the final meat quality, and studies have reported the effects of animal aging or physiological maturity on meat traits attributes, especially tenderness (Duarte et al., 2011; Shorthose and Harris, 1990). A notable finding by Gallo et al. (2017) was that the farm type affected the age at slaughter of cull cows, and that these differences were due to housing systems and feeding.

Figure 7.

Least squares means and confidence intervals of price ratio for (A) year of sale, (B) month of sale, (C) culling reason (Prod: low production, Bre: breeding problem, Inj: injury, Mast: Mastitis and udder problem, Abo: abort, Feet: Leg and feet problem, Other: Other reasons), and (D) lactation number.

Farm also had an effect (P < 0.001; Table 8) on price ratio, thus indicating that the differences in production, feeding, management or other factors from each farm are affecting price of cull cows and, indirectly, the carcass merit of these animals. Ahlman et al. (2011) reported differences between organic and conventional dairy operations; the authors also found that longevity, culling dynamic, and predominant reasons for culling were different between the 2 types of farm. Therefore, the type of farm has a large effect on animal overall characteristics, and consequently, on culling, price and final carcass quality. While price or carcass quality was not measured, Weigel et al. (2003) reported the differences in voluntary and involuntary culling in expanded dairy herd. The authors showed unfavorable trends of culling when farms changed from small–to-large scale. Specifically, these culling differences affect cow condition and, consequently, cow price and the final carcass quality of these animals.

Culling reason is another crucial factor associated with cow condition and cull cow price, but it is also related with carcass and meat quality of cows. In fact, this variable had a significant (P < 0.001; Table 8) effect on price ratio. The reasons of injury and leg and feet problems were the 2 culling reasons leading to the lowest prices received for cull cows during marketing (0.676 and 0.729, respectively; Figure 7). Seegers et al. (1998) also reported that locomotor disorders, accidents and health disorders were associated with lower carcass weights of Holstein cows. As previously mentioned, these culling reasons are associated with quality defects which increase discounts during marketing. Culling reasons of breeding and low milk production had the highest price ratios, 0.793 and 0.792, respectively; similar findings were reported by Seegers et al. (1998).

The months with lower price ratios were November and December (0.704 and 0.736, respectively; Table 8), but with November having considerably lower price compared with December. The month with the highest least squares means of price ratios were May and April (0.779 and 0.776, respectively; Figure 7). The effect of year of culling on price ratio was the same as previously mentioned for BP ($/cwt), which decreased from 2015 to 2019. Although price ratio was created aiming to remove the seasonality effect, there was still a strong effect of month and year for price ratio. These findings clearly suggest that the national average prices did not fully represent the Wisconsin cow prices fluctuations (Figures 6 and 7). While the national average cow price is lowest in the Fall, the price ratio results reported here indicate that the Wisconsin cull Holstein cow price decreases even more during November and December.

There is a paucity of studies that have attempted to quantify the factors associated with price and carcass traits of cull dairy cows (Bazzoli et al. 2014; Gallo et al. 2017), and no research has been done aiming to quantify the effect of life history events on price of cull dairy cows. The predictive performance of the multiple linear regression model for price ratio had an R2 of 0.4706, an RSME of 0.1045, and an MAE of 0.076. The adjustment of price was performed aiming to remove seasonality effects in order to find productive and health event predictors related to carcass merit. As previously shown, price ratio had a high canonical correlation with carcass merit characteristics, thus indicating that predictors associated with price ratio are also associated with carcass merit of cull dairy cows. Although the predictor variables available in this study were, mostly, for milk production and reproductive performance, the addition of health events could definitely improve the predictive ability of the model; most importantly, the model becomes more representative by accounting for more events in the cow’s life.

Conclusion

To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to report life history events affecting sale BP and carcass merit of cull dairy cows sold through auction markets. Price ratio was highly correlated with carcass traits, therefore, being a good indicator of carcass merit. The life history events affecting sale BP and price ratio were LACT, days open, days dry, ME305, total milk production and total milk solids production. Such life history events, and their association with cow body condition and health (e.g., injury and feet and leg problems) were decisive factors determining cow price. As such, cow price was highly associated with carcass merit of cull dairy cows. In terms of seasonality, marketing cows during the Fall months resulted in lower prices while marketing in months of Spring and early Summer resulted in higher prices. Overall, these results indicate that life history events affect carcass merit of cull dairy cows and, together with the effect of seasonality, contribute to their final price.

In this study, milk production and milk composition variables had small effect on BP, which could be a consequence of cows being culled at different stages of lactation. Nonetheless, additional research should be carried out to further investigate differences in stage of lactation, and to identify other factors involved with price and carcass traits of cull dairy cows, such as health events. In the future, this proposed approach could combine the investigation of farm-level effects, additional life events, carcass, and meat quality variables to deeply understand the role of each of these factors. Such knowledge could improve management decisions, maximize cow value, and improve the final meat quality of dairy cows. This would be beneficial for both the producer, beef processors and consumers alike.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the Baldwin Wisconsin Idea Endowment and the University of Wisconsin-Madison for proving the funding, and the Professional Dairy Producers of Wisconsin (PDPW), auction market agency, and meat packing plant participants for providing the data. The first author acknowledges also a fellowship provided by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES, Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel), Brazil.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- ARC

aggregate redundancy coefficients

- CCA

canonical correlation analysis

- MAE

mean absolute error

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare no real or perceived conflicts of interest.

Literature Cited

- Adamczyk, K., J. Makulska, W. Jagusiak, and A. Węglarz. . 2017. Associations between strain, herd size, age at first calving, culling reason and lifetime performance characteristics in Holstein-Friesian cows. Animal 11:327–334. doi: 10.1017/S1751731116001348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahlman, T., B. Berglund, L. Rydhmer, and E. Strandberg. . 2011. Culling reasons in organic and conventional dairy herds and genotype by environment interaction for longevity. J. Dairy Sci. 94:1568–1575. doi: 10.3168/jds.2010-3483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahola, J. K., H. A. Foster, D. L. Vanoverbeke, K. S. Jensen, R. L. Wilson, J. B. Glaze, Jr, T. E. Fife, C. W. Gray, S. A. Nash, R. R. Panting, . et al. 2011. Quality defects in market beef and dairy cows and bulls sold through livestock auction markets in the Western United States: II. Relative effects on selling price. J. Anim. Sci. 89:1484–1495. doi: 10.2527/jas.2010-3171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrew, S. M., D. R. Waldo, and R. A. Erdman. . 1994. Direct analysis of body composition of dairy cows at three physiological stages. J. Dairy Sci. 77:3022–3033. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(94)77244-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bascom, S. S., and A. J. Young. . 1998. A summary of the reasons why farmers cull cows. J. Dairy Sci. 81:2299–2305. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(98)75810-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bazzoli, I., M. De Marchi, A. Cecchinato, D. P. Berry, and G. Bittante. . 2014. Factors associated with age at slaughter and carcass weight, price, and value of dairy cull cows. J. Dairy Sci. 97:1082–1091. doi: 10.3168/jds.2013-6578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butts, C. T 2018. yacca: yet another canonical correlation analysis package. Available from https://cran.r-project.org/package=yacca

- Calcagno, V 2019. glmulti: model selection and multimodel inference made easy. Available from https://cran.r-project.org/package=glmulti

- Cui, B 2020. DataExplorer: automate data exploration and treatment. R package version 0.8.1. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=DataExplorer

- De Vries, A., J. D. Olson, and P. J. Pinedo. . 2010. Reproductive risk factors for culling and productive life in large dairy herds in the eastern United States between 2001 and 2006. J. Dairy Sci. 93:613–623. doi: 10.3168/jds.2009-2573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DRMS 2014. DHI glossary. Available from http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.686.2482&rep=rep1&type=pdf

- Duarte, M. S., P. V. Paulino, M. A. Fonseca, L. L. Diniz, J. Cavali, N. V. Serão, L. A. Gomide, S. F. Reis, and R. B. Cox. . 2011. Influence of dental carcass maturity on carcass traits and meat quality of Nellore bulls. Meat Sci. 88:441–446. doi: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2011.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallo, L., E. Sturaro, and G. Bittante. . 2017. Body traits, carcass characteristics and price of cull cows as affected by farm type, breed, age and calving to culling interval. Animal 11:696–704. doi: 10.1017/S1751731116001592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadley, G. L., S. B. Harsh, and C. A. Wolf. . 2002. Managerial and financial implications of major dairy farm expansions in Michigan and Wisconsin. J. Dairy Sci. 85:2053–2064. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(02)74283-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadley, G. L., C. A. Wolf, and S. B. Harsh. . 2006. Dairy cattle culling patterns, explanations, and implications. J. Dairy Sci. 89:2286–2296. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(06)72300-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Härdle, W. K., and L. Simar. . 2019. Canonical correlation analysis. In: Applied multivariate statistical analysis. Cham: Springer. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-26006-4_16. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Harris, M. K., L. C. Eastwood, C. A. Boykin, A. N. Arnold, K. B. Gehring, D. S. Hale, C. R. Kerth, D. B. Griffin, J. W. Savell, K. E. Belk, . et al. 2017. National Beef Quality Audit–2016: transportation, mobility, live cattle, and carcass assessments of targeted producer-related characteristics that affect value of market cows and bulls, their carcasses, and associated by-products. Transl. Anim. Sci. 1(4):570–584. doi: 10.2527/tas2017.0063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris, M. K., L. C. Eastwood, C. A. Boykin, A. N. Arnold, K. B. Gehring, D. S. Hale, C. R. Kerth, D. B. Griffin, J. W. Savell, K. E. Belk, . et al. 2018. National Beef Quality Audit-2016: assessment of cattle hide characteristics, offal condemnations, and carcass traits to determine the quality status of the market cow and bull beef industry. Transl. Anim. Sci. 2:37–49. doi: 10.1093/tas/txx002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hebbali, A 2020. olsrr: tools for building OLS regression models. Available from https://cran.r-project.org/package=olsrr

- Jaurena, G., and J. M. Moorby. . 2017. Lactation and body composition responses to fat and protein supplies during the dry period in under-conditioned dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 100:1107–1121. doi: 10.3168/jds.2016-11012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn, M 2020. caret: classification and regression training. Available from https://cran.r-project.org/package=caret

- Lee, M. R., P. R. Evans, G. R. Nute, R. I. Richardson, and N. D. Scollan. . 2009. A comparison between red clover silage and grass silage feeding on fatty acid composition, meat stability and sensory quality of the M. Longissimus muscle of dairy cull cows. Meat Sci. 81:738–744. doi: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2008.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowe, B. K., R. O. McKeith, J. R. Segers, J. A. Safko, M. A. Froetschel, R. L. Stewart, A. M. Stelzleni, M. N. Streeter, J. M. Hodgen, and T. D. Pringle. . 2012. The effects of zilpaterol hydrochloride supplementation on market dairy cow performance, carcass characteristics, and cutability. Prof. Anim. Sci. 28:150–157. doi: 10.15232/S1080-7446(15)30335-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moraes, L. E., E. Kebreab, A. B. Strathe, J. Dijkstra, J. France, D. P. Casper, and J. G. Fadel. . 2015. Multivariate and univariate analysis of energy balance data from lactating dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 98:4012–4029. doi: 10.3168/jds.2014-8995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreira, L. C., G. J. M. Rosa, and D. Schaefer. . 2020. Get more value from cull cows. Hoard’s Dairyman Magazine. April 10, 220–221. Available from https://www.hoards.com/

- National Agricultural Statistics Service (NASS) 2020. Prices received: cattle prices received by month, US. Available from https://www.nass.usda.gov/Charts_and_Maps/Agricultural_Prices/priceca.php

- Pinedo, P. J., A. De Vries, and D. W. Webb. . 2010. Dynamics of culling risk with disposal codes reported by Dairy Herd Improvement dairy herds. J. Dairy Sci. 93:2250–2261. doi: 10.3168/jds.2009-2572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team 2020. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Available from https://www.r-project.org/

- Ruda, L., C. Raschka, K. Huber, R. Tienken, U. Meyer, S. Dänicke, and J. Rehage. . 2019. Gain and loss of subcutaneous and abdominal fat depot mass from late pregnancy to 100 days in milk in German Holsteins. J. Dairy Res. 86:296–302. doi: 10.1017/S0022029919000542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schäff, C., S. Börner, S. Hacke, U. Kautzsch, H. Sauerwein, S. K. Spachmann, M. Schweigel-Röntgen, H. M. Hammon, and B. Kuhla. . 2013. Increased muscle fatty acid oxidation in dairy cows with intensive body fat mobilization during early lactation. J. Dairy Sci. 96:6449–6460. doi: 10.3168/jds.2013-6812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seegers, H., N. Bareille, and F. Beaudeau. . 1998. Effects of parity, stage of lactation and culling reason on the commercial carcass weight of French Holstein cows. Livest. Prod. Sci. 56:79–88. doi: 10.1016/S0301-6226(98)00124-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shorthose, W. R., and P. V. Harris. . 1990. Effect of animal age on the tenderness of selected beef muscles. J. Food Sci. 55:1–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2621.1990.tb06004.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stojkov, J., M. A. G. von Keyserlingk, T. Duffield, and D. Fraser. . 2020. Fitness for transport of cull dairy cows at livestock markets. J. Dairy Sci. 103:2650–2661. doi: 10.3168/jds.2019-17454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Therkildsen, M., S. Stolzenbach, and D. V. Byrne. . 2011. Sensory profiling of textural properties of meat from dairy cows exposed to a compensatory finishing strategy. Meat Sci. 87:73–80. doi: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2010.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- USDA 2018. Health and management practices on U.S. dairy operations, 2014. National Animal Health Monitoring System Available from https://www.aphis.usda.gov/animal_health/nahms/dairy/downloads/dairy14/Dairy14_dr_PartIII.pdf

- USDA 2019. Livestock slaughter 2015 summary. 68. Available from https://usda.mannlib.cornell.edu/usda/nass/LiveSlauSu/2010s/2016/LiveSlauSu-04-20-2016.pdf

- Vestergaard, M., N. T. Madsen, H. B. Bligaard, L. Bredahl, P. T. Rasmussen, and H. R. Andersen. . 2007. Consequences of two or four months of finishing feeding of culled dry dairy cows on carcass characteristics and technological and sensory meat quality. Meat Sci. 76:635–643. doi: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2007.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weigel, K. A., R. W. Palmer, and D. Z. Caraviello. . 2003. Investigation of factors affecting voluntary and involuntary culling in expanding dairy herds in Wisconsin using survival analysis. J. Dairy Sci. 86:1482–1486. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(03)73733-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wickham, H 2016. ggplot2: elegant graphics for data analysis. Available from https://ggplot2.tidyverse.org/

- Wickham, H., R. François, L. Henry, and K. Müller. . 2020. dplyr: a grammar of data manipulation. Available from https://cran.r-project.org/package=dplyr

- Wickham, H., and L. Henry. . 2020. tidyr: tidy messy data. Available from https://cran.r-project.org/package=tidyr