Abstract

Introduction

We aimed to identify the possible chain of events leading to fatal scuba diving incidents in Australia from 2001–2013 to inform appropriate countermeasures.

Methods

The National Coronial Information System was searched to identify scuba diving-related deaths from 2001–2013, inclusive. Coronial findings, witness and police reports, medical histories and autopsies, toxicology and equipment reports were scrutinised. These were analysed for predisposing factors, triggers, disabling agents, disabling injuries and causes of death using a validated template.

Results

There were 126 known scuba diving fatalities and 189 predisposing factors were identified, the major being health conditions (59; 47%), organisational/training/experience/skills issues (46; 37%), planning shortcomings (29; 23%) and equipment inadequacies (24; 19%). The 138 suspected triggers included environmental (68; 54%), exertion (23; 18%) and gas supply problems (15; 12%) among others. The 121 identified disabling agents included medical-related (48; 38%), ascent-related (21; 17%), poor buoyancy control (18; 14%), gas supply (17; 13%), environmental (13; 10%) and equipment (4; 3%). The main disabling injuries were asphyxia (37%), cardiac (25%) and cerebral arterial gas embolism/pulmonary barotrauma (15%).

Conclusions

Chronic medical conditions, predominantly cardiac-related, are a major contributor to diving incidents. Divers with such conditions and/or older divers should undergo thorough fitness-to-dive assessments. Appropriate local knowledge, planning and monitoring are important to minimise the potential for incidents triggered by adverse environmental conditions, most of which involve inexperienced divers. Chain of events analysis should increase understanding of diving incidents and has the potential to reduce morbidity and mortality in divers.

Keywords: Coroners findings, Diving incidents, Deaths, Drowning, Fitness to dive, Medical conditions and problems, Root cause analysis

Introduction

Scuba diving safety can be influenced by a broad range of factors that present before, during and sometimes after the dive. Such factors include: health and fitness; organisation; planning; communication and supervision; equipment problems; decisional factors; and various environmental factors.[ 1 , 2] A diving incident usually involves a trigger which may lead to a cascade of related events, some precipitated by the diver and some circumstantial, which may lead to morbidity or mortality. Several studies of diver fatalities have utilised a sequential or ‘chain of events’ analysis (CEA) to describe the suspected sequence of events within the incident. This began with a landmark report on US fatalities which divided the CEA into four categories.[ 1] These were defined as the trigger, disabling agent (DA, an action or circumstance following the trigger which caused injury or illness), disabling injury (DI, directly responsible for death or incapacitation leading to drowning), and cause of death (specified by a medical examiner). The methodology described was adapted and subsequently applied to a large series of Australian fatalities.[ 2]

However, preceding the trigger may be factors which predispose to such an event. Some reports have highlighted the role that human factors may play in diving incidents.[ 3 , 4] Such factors, among others, have been included in a revised CEA template as an additional category called ‘predisposing factors’.[ 5] This revised template was validated and subsequently used to analyse this current series of scuba diving fatalities. Such an analysis helps to identify common features in the incidents and can be used to devise appropriate countermeasures.

Methods

This was a case series of scuba diving-related fatalities that occurred in Australian waters from 2001 to 2013, inclusive. Approval for the study was received from the Human Research Ethics Committees of the Victorian Department of Justice, the Royal Prince Alfred Hospital, the Coroner’s Court of Western Australia, the Queensland Office of the State Coroner and Deakin University, Melbourne.

SEARCH AND REVIEW

The methodology for identifying relevant cases is described in detail elsewhere.[ 6] In brief, it comprised a comprehensive key word search of the National Coronial Information System (NCIS)[ 7] to identify scuba diving-related deaths reported to various state coronial services for the years 2001 to 2013, inclusive. Cases identified were matched with those collected by the Divers Alert Network Asia-Pacific (DAN AP) via the media or the diving community in order to minimise the risk of over- or under-reporting. Relevant coronial findings, witness statements, police, autopsy and equipment reports and medical histories were reviewed, and annual case series were prepared and published.[ 8 - 19]

CHAIN OF EVENTS ANALYSIS

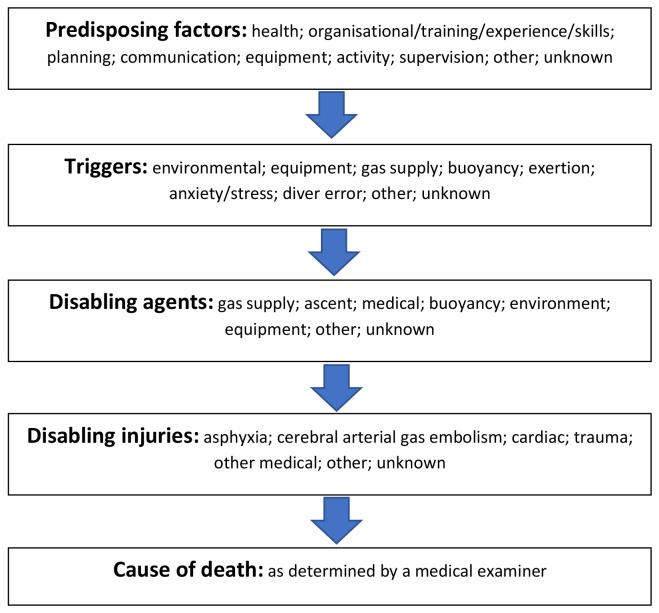

This chain of events analysis for the scuba fatalities was based on the criteria and templates previously published.[ 5] Event categories and sub-categories are shown in Figure 1, and categories are defined as follows:

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the chain of events analysis of a scuba diving accident

Predisposing factor: A relevant factor(s) present prior to the dive, and/or prior to the trigger occurring, and which was believed to have predisposed to the incident and/or to key components in the accident chain (e.g., the trigger or disabling agent).

Trigger: The earliest identifiable event that appeared to transform an unremarkable dive into an emergency.

Disabling agent: An action or circumstance (associated with the Trigger) that caused injury or illness. It may be an action of the diver or other persons, function of the equipment, effect of a medical condition or a force of nature.

Disabling injury: Injury or condition directly responsible for death or incapacitation followed by death from drowning.

Cause of death: As specified by a medical examiner, which could be the same as the disabling injury or could be drowning secondary to injury.

After planning, one author (JL) applied the published templates to the data and obtained the reported results. Both authors were involved in writing the report. A hypothetical example of the application of such a template is: a diver with a faulty tank pressure gauge (predisposing factor) runs out of air (trigger), makes an emergency ascent (disabling agent), suffers a cerebral arterial gas embolism (disabling injury), becomes unconscious and subsequently drowns (cause of death).

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Descriptive analyses based on means (standard deviation) or medians (range) as appropriate were conducted using SPSS Version 25 (IBM, Armonk, New York). Comparisons of proportions employed odds ratios (OR) accompanied by 95% confidence intervals (95% CI). The level of significance was considered as P ≤ 0.05.

Results

There were 126 scuba diving fatalities during the study period. The mean (SD) age was 44 (13) years and 99 (79%) of the victims were male. Autopsy reports were available to the researchers for 123 (98%) of the cases.

PREDISPOSING FACTORS

One hundred and eighty-nine predisposing factors were identified as possible or likely contributors to the 126 deaths (Table 1). No predisposing factors were identified in seven deaths. The main factors were related to the victims’ health and/or organisational/training/experience/skills-related factors prior to diving.

Table 1. Predisposing factors (n = 189) associated with 126 scuba fatalities; some deaths involved multiple predisposing factors, hence the number of predisposing factors exceeds the number of cases; * = absence of items such as wetsuit, knife, fins, snorkel when needed .

| Predisposing factor | Subgroup | n | Mean (SD) age | Male/Female |

| Health | 59 (47%) | 50 (12) | 47/12 | |

| Significant medical history | 46 | |||

| Fatigue | 7 | |||

| Drug / medication intake | 4 | |||

| Obesity | 2 | |||

| Organisational/training/experience/skills | 46 (37%) | 39 (13) | 32/14 | |

| Inexperienced overall | 30 | |||

| Poor organisation | 6 | |||

| Lack of training / skills for dive | 5 | |||

| Lack of recent experience | 5 | |||

| Planning Poor pre-dive choice of: | 29 (23%) | 40 (12) | 24/5 | |

| Conditions | 15 | |||

| Solo diving in poor conditions | 6 | |||

| Location | 4 | |||

| Other | 4 | |||

| Absence of appropriate equipment or use of faulty equipment | 24 (19%) | 41 (12) | 19/5 | |

| Faults | 9 | |||

| Absence* | 9 | |||

| Over-weighting | 4 | |||

| Other | 2 | |||

| Activity | 14 (11%) | 41 (12) | 13/1 | |

| Penetration | 6 | |||

| Deep diving with CCR | 3 | |||

| Seafood collection | 3 | |||

| Other | 2 | |||

| Supervision Poor supervision by: | 14 (11%) | 37 (12) | 7/7 | |

| Buddy | 8 | |||

| Instructor | 5 | |||

| Divemaster / guide | 1 | |||

| Communication Poor communication or co-ordination between: | 3 (2%) | 37 (8) | 2/1 | |

| Instructor and student | 1 | |||

| Diver and others | 1 | |||

| Dive shop and instructor | 1 |

Pre-existing medical conditions: Forty-six divers (37%) were identified as having chronic medical conditions which likely contributed to their incident. These were predominantly cardiac conditions such as ischaemic heart disease (IHD), but also included respiratory conditions, hypertension, diabetes and epilepsy, among others. They are the subject of a separate report.[ 20]

Organisational/Training/Experience/Skills: Inexperience and the associated relatively poor diving skills were implicated in 30 of the 46 deaths in this category. However, the victims included five experienced divers who had not dived for extended periods. Among five divers with little relevant experience were three very experienced divers who died due to a lack of familiarity with new equipment which included a drysuit, technical diving equipment and a rebreather. The six cases associated with organisational issues included a poor internal process by a dive shop for the oversight of the progress and needs of trainees, poor systems for the organising of introductory scuba dives, unqualified staff giving inappropriate medical advice and an inadequate system for ensuring the appropriate screening and oversight of inexperienced divers.

Planning: These factors involved poor planning decisions, generally immediately prior to the dive. The majority involved a decision to dive in obviously unsuitable conditions which included rough water and/or surge, very poor visibility and/or strong currents. Six divers set out to dive solo in conditions that were obviously unsuitable, especially when alone, and another three intentionally separated in such circumstances. One diver failed to correctly plan his decompression requirements, and another his breathing gas requirements while diving in a cave. Other issues involved poor choice of instructor/student ratios and poor gas supply planning.

Absence of appropriate equipment or use of faulty equipment: Predisposing factors related to equipment were contributory to 24 incidents, some with multiple issues. Relevant faults were found in a variety of equipment which included the buoyancy compensation device (BCD), pressure gauge, regulator, alternative air source, oxygen sensors and tank valve. Incorrect gear configuration or assembly at the site contributed to four deaths, poor-fitting wetsuits to two and weights in BCD pockets and unable to be ditched was contributory to one death. Substantial oil in cylinder air likely contributed to another.

Activity: Fourteen victims were undertaking activities that can potentially carry an increased risk of an incident. These included six penetration dives, three in freshwater caves and two in deep wrecks. In four of these, the victims became separated and ran out of breathing gas. Three incidents occurred during deep dives using a closed circuit rebreather (CCR). Another three incidents involved attacks by large sharks whilst the victims were either harvesting seafood, spearfishing or diving near where fishing was being conducted.

Poor supervision: In 13 of the 14 such incidents, poor decisions by the supervisor were made prior to the dive. Five of these involved a formal instructional situation and four involved divers who had very little or no experience. Another involved a diver (a non-instructor) teaching his girlfriend to dive. Most other incidents involved more experienced divers making poor pre-dive decisions, often about sites or conditions, which affected their inexperienced buddies.

Poor communication or co-ordination: Three incidents specifically involved poor pre-dive communication between divers and/or those overseeing them, although several cases in the preceding categories were also associated with communication or co-ordination issues.

TRIGGERS

One-hundred and thirty-nine possible or likely triggers were identified (Table 2).

Table 2. Triggers (n = 139) associated with 126 scuba fatalities; some deaths involved multiple triggers; * = Various faults in regulators, tank valves, oxygen sensors, wet and dry suits .

| Trigger | Subgroup | n | Mean (SD) age | Male/Female |

| Environment | 68 (54%) | 45 (13) | 52/16 | |

| Conditions | 37 | |||

| Immersion effects | 19 | |||

| Entrapment | 5 | |||

| Marine animal | 3 | |||

| Other | 4 | |||

| Exertion | 23 (18%) | 52 (9) | 21/2 | |

| Pre-dive | 4 | |||

| During dive | 13 | |||

| Post-dive | 6 | |||

| Gas supply | 15 (12%) | 42 (9) | 13/2 | |

| Out of gas | 8 | |||

| Low gas | 3 | |||

| Incorrect mix | 2 | |||

| Contamination | 1 | |||

| Other | 1 | |||

| Equipment* | N/A | 10 (8%) | 32 (12) | 9/1 |

| Anxiety | N/A | 10 (8%) | 39 (15) | 6/4 |

| Primary diver error | N/A | 4 (3%) | 37 (7) | 2/2 |

| Buoyancy | N/A | 3 (2%) | 51 (10) | 1/2 |

| Other | N/A | 6 (5%) | 43 (15) | 5/1 |

| Unknown | N/A | 14 (11%) |

Environmental: The main triggers were environment-related and were implicated in more than half of the fatalities. These were predominantly associated with adverse conditions which included current, rough seas, poor visibility, surge and depth. Twenty-three of the 37 divers with a conditions-related trigger were inexperienced, compared with 34 of 78 divers with other triggers. This indicates a higher association of conditions-related triggers among ‘inexperienced’ divers than with ‘experienced’ divers (OR 2.22, 95% CI 1.00–4.94; P = 0.05).

Nineteen fatalities were believed to have been associated with the cardiac-related effects of immersion; seven of these due to immersion per se, and twelve with the combination of immersion and exertion due to conditions. Five incidents involved entrapment due to environmental circumstances. Three deaths were associated with the presence of and subsequent attack by a shark.

Exertion: Exertion-related triggers were associated with exertion before, during or after a dive. This exertion was unrelated to adverse sea conditions and was what would normally be expected with swimming or walking whilst wearing scuba equipment. Seventeen of these 23 incidents resulted in a cardiac-related DI. Some causes included exertion before the dive (e.g., walking to the site wearing diving equipment), exertion during a dive (e.g., carrying heavy catch bags) and exertion post dive (e.g., long surface swims or boarding a boat).

Gas supply: Eleven of these 15 incidents involved low or exhaustion of breathing gas situations which occurred while hunting seafood, salvaging an anchor from a wreck at depth and during a cave penetration dive. Three incidents resulted from inappropriate breathing gas: one from contamination by oil; and two from incorrect breathing mixtures. One novice entered the water without his regulator in his mouth.

Equipment: The 10 equipment-related triggers included: one incident each of a faulty mouthpiece causing aspiration; faulty tank ‘J-valve’ causing loss of reserve air; tight wetsuit causing breathing restriction and subsequent panic; tank slippage causing loss of air supply; faulty mask causing leak and panic; alternate air source detachment causing loss of mask and panic; loss of fin causing mobility problems and panic; faulty oxygen sensors causing hyperoxia; faulty drysuit inflator causing problems at depth and during ascent; and faulty BCD inflator causing rapid ascent.

Anxiety: Anxiety is a likely trigger in a substantial number of diving-related deaths. However, it was only included as a factor in the CEA when there were specific witness accounts reporting that the victim displayed signs of anxiety, and this appeared to have led to panic and the subsequent fatality. There were 10 such accounts, all but one involving novice divers.

Buoyancy: Only three of the incidents appeared to have been triggered by a buoyancy-related problem. One involved a diver who had logged 55 dives but still had not mastered buoyancy control and who sank after venting too much air from her BCD during ascent. The other two involved experienced divers who were using relatively unfamiliar equipment; one a CCR and the other a drysuit.

Primary diver error: Many incidents involved diver error in the accident chain, some prior to the dive and others arising from poor decisions or arising subsequent to a problem. Four incidents are likely to have been triggered by primary diver error, in conjunction with other triggers. In one case, the diver failed to heed a repeated warning on his CCR. In another, a substantially over-weighted drysuit diver, relatively inexperienced in the use of her drysuit (although highly experienced otherwise), redescended alone with relatively little remaining air and inadvertently inverted while adjusting buoyancy. In the third incident, an experienced cave diver inadequately accounted for her ability to relocate and reach an alternative, and necessary, air supply on the other side of a narrow constriction. The final incident involved the diver entering the water without his regulator in place.

Other triggers: included three medical-related conditions, trauma, loss of dentures and inadequate decompression.

DISABLING AGENTS

There were 121 likely disabling agents identified in the 126 scuba fatalities (Table 3).

Table 3. Disabling agents (n = 121) associated with 126 scuba fatalities; * = Unwitnessed but evidence of an ascent complication.

| Disabling agent | Subgroup | n | Mean (SD) age | Male/Female |

| Medical | 48 (38%) | 50 (12) | 42/6 | |

| Cardiac disease/dysfunction | 38 | |||

| Oxygen seizure | 3 | |||

| Immersion pulmonary oedema | ≥ 3 | |||

| Other | 4 | |||

| Ascent | 21 (17%) | 39 (13) | 18/3 | |

| Rapid ascent | 9 | |||

| Gas trapping | 3 | |||

| Inadequate decompression | 1 | |||

| Unwitnessed* | 8 | |||

| Buoyancy | 18 (14%) | 42 (11) | 9/9 | |

| Negative at surface | 8 | |||

| Poor control underwater | 7 | |||

| Grossly overweighted | 3 | |||

| Gas supply | 17 (13%) | 44 (13) | 13/4 | |

| Out of gas | 11 | |||

| Loss of regulator access | 4 | |||

| Inappropriate mix | 2 | |||

| Environmental | 13 (10%) | 38 (11) | 12/1 | |

| Conditions | 7 | |||

| Shark attacks | 3 | |||

| Entrapment | 3 | |||

| Equipment | 4 (3%) | 38 (12) | 4/0 | |

| Unknown | 11 (9%) |

Medical: More than three-quarters of the medical-related disabling agents were likely due to cardiac conditions, predominantly ischaemic heart disease. The ‘Other’ category included two subdural haematomas, and one each from asthma and a pulmonary cyst.

Ascent: In at least 21 incidents, the disabling agents were clearly ascent-related, borne out by evidence of pulmonary barotrauma (PBT) or cerebral arterial gas embolism (CAGE). The actual ascent was unwitnessed in eight cases, including three where the diver had run out of breathing gas. There were other incidents in which the disabling agent may have been the ascent although this was unclear and, therefore, not included. Nine incidents were characterised by a witnessed rapid ascent, three of these involving exhaustion of the breathing gas. The incidents in which gas trapping occurred during ascent were likely associated with a pre-existing medical condition including asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and pleural effusion. These ascents were witnessed, and none were described as rapid.

Buoyancy: Eight victims became incapacitated by insufficient buoyancy on the surface as a direct consequence of failing to inflate their BCD and/or dump weights. Seven others were disabled while at depth and subsequently drowned due to poor buoyancy control. Two of these were drysuit divers who became inverted while trying to adjust buoyancy.

Gas supply: The identified events where the disabling agent was related to the lack of, or inappropriate supply of, breathing gas involved: direct exhaustion of breathing gas in eight; out of gas post-entrapment in three; loss of access to demand valve in four; and beginning the dive with inappropriate breathing gas in two (one involving suicide using pure helium and the other a hypoxic mix breathed at the surface).

Environmental: Seven deaths involved adverse sea conditions with six of the victims being disabled after heavy contact with rocks, and one drowning after being swept off the rocks. Three were disabled by shark attacks and another three were trapped and subsequently ran out of breathing gas as a direct result of entrapment.

Equipment: These incidents included one each of: incorrect fitting of an alternative air supply leading to detachment during the dive; equipment weight and bulk causing incapacitation in rough surface conditions; a ditched weight belt becoming entangled with the tank pressure gauge andthe loss of a fin and mask subsequent to impact with a boat hull.

DISABLING INJURIES

The predominant disabling injuries identified were asphyxia, cardiac causes and CAGE with or without evidence of PBT (Table 4). Others were immersion pulmonary oedema (IPE), trauma, and decompression sickness (DCS). In 21 cases, no clear disabling injury could be identified. In nine of these, there were indicators of a possible cardiac-related incident, although other factors, such as signs of drowning or CAGE, hampered a clear determination.

Table 4. Relative occurrence of disabling injuries in 126 scuba fatalities. Ages are in years. Data are mean (SD) unless otherwise specified. N/A – not applicable; PBT/CAGE – pulmonary barotrauma/cerebral arterial gas embolism; IPE – immersion pulmonary oedema; DCS – decompression sickness .

| Disabling agent | n | Male/Female | Age (all) | Age (males) | Age (females) |

| Asphyxia | 47 (37) | 33/14 | 42 (12) | 42 (10) | 40 (15) |

| Cardiac | 32 (25) | 31/1 | 52 (11) | 52 (11) | 46 (0) |

| CAGE/PBT | 19 (15) | 16/3 | 40 (14) | 42 (14) | 28 (12) |

| IPE | 3 (2) | 0/3 | 50 (1) | N/A | 50 (1) |

| Trauma | 3 (2) | 3/0 | 29 (6) | 29 (6) | N/A |

| DCS | 1 (1) | 1/0 | 45 (0) | 45 (0) | N/A |

| Unclear | 21 (17) | 16/5 | 47 (12) | 49 (12) | 41 (11) |

The numbers of victims in each of the Australian states identified with a cardiac-related disabling injury were: Queensland (10/29); Western Australia (5/19); South Australia (5/17); New South Wales (7/32); Victoria (4/20) and Tasmania (1/9). Among victims aged 45 years or more, 26 of 66 had a cardiac-related disabling injury, compared with six of 60 victims younger than 45 years. This indicates a strong association between being at least 45 years old and having a cardiac-related disabling injury (OR 5.85, 95% CI 2.20–15.55; P = 0.0004). Twenty-five of the 32 deaths attributed to a cardiac disabling injury were associated with exertion, compared with 18 of 94 non-cardiac deaths (78% vs. 19%). This indicates a strong association between a disabling cardiac injury and preceding exertion (OR 6.31, 95% CI 2.52–15.80; P = 0.001).

Rough conditions were a trigger in 15 of 47 deaths attributed to asphyxia as the DI, and 6 of 79 of the deaths attributed to other disabling injuries (32% vs. 8%). This indicates a strong association between the trigger of rough conditions and asphyxia as the disabling injury (OR 5.70, 95% CI 2.03–16.04; P = 0.001). There were no other significant associations.

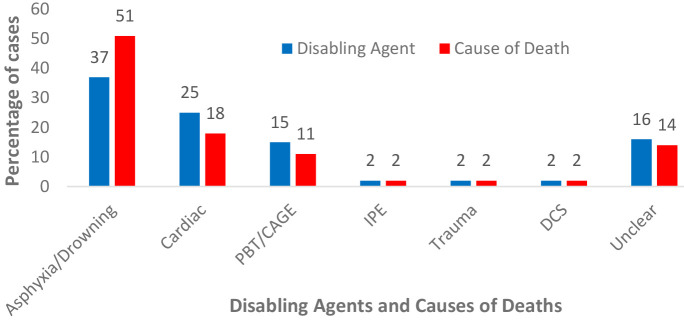

CAUSES OF DEATH

The predominant causes of death identified were drowning, which was reported in 64 (51%) of the incidents, cardiac causes (23, 18%) and PBT/CAGE (14, 11%). Others included trauma (three, 2%), IPE (two, 2%) and DCS (two, 2%). In 18 (14%) cases, no clear cause of death was identified by the pathologists.

Figure 2 compares the likely disabling injuries as identified by the COE analysis with the causes of death reported by the pathologists. Drowning has traditionally been (and still is in many places) recorded as the default cause of death when a lifeless diver was recovered from the water and no other obvious cause of death was apparent on autopsy. The difference between the 51% drowning as the cause of death Figure 2 compares the likely disabling injuries as identified by the COE analysis with the causes of death reported by the pathologists. Drowning has traditionally been (and still is in many places) recorded as the default cause of death when a lifeless diver was recovered from the water and no other obvious cause of death was apparent on autopsy. The difference between the 51% drowning as the cause of death and 37% asphyxia as disabling injury may reflect cases where drowning was secondary to a cardiac arrhythmia or an injury such as CAGE.

Figure 2.

Comparison of disabling injuries and causes of death in 126 scuba fatalities; PBT/CAGE – pulmonary barotrauma/cerebral arterial gas embolism; IPE – immersion pulmonary oedema; DCS – decompression sickness

Discussion

Various factors played an important part throughout many of these fatal events. These included pre-existing health conditions, poor fitness, lack of experience, organisational shortfalls, poor planning or supervision and inadequate equipment maintenance. In addition, inattention, carelessness, inappropriate attitude, poor decision-making and inappropriate actions, whether prior to or during an incident, can all influence the outcome. The results of this CEA highlight the value of the addition of the link for ‘predisposing factors’ which identified almost 200 factors that were present prior to the dives and which likely, or possibly, contributed to these fatalities. Almost one half of the predisposing factors identified were health-related and these are discussed in a separate report.[ 20] More than one third were associated with organisational factors, training, experience and skills; whilst one quarter were planning-related. Many diving incidents involve more than one factor within and between the various categories in the CEA template, as clearly demonstrated here.

ORGANISATIONAL/TRAINING/EXPERIENCE/SKILLS FACTORS

An important organisational-level consideration is the need for improved education of the diving and medical communities in fitness-to-dive considerations, and how certain health conditions can impact diving safety. Another organisational issue that was apparent in several incidents was the need for dive operations to have clear guidelines on staff responsibilities as well as hand-over to ensure appropriate communication between staff about a customer in their care. The fact that almost three quarters of the victims in this series were found wearing their weight belts[ 6] suggests that more needs to be done during and after basic scuba training to highlight the need to attain positive buoyancy in an emergency and to consolidate the required skills.

However, the predominant factor in this category was inexperience, which is discussed in detail in a previous paper.[ 6] Although more than 90% of the victims were certified or undergoing training at the time of their fatal incident, approximately one half had done fewer than 30 lifetime dives and were, therefore, relative novices. As such, it is unsurprising that lack of skills and inexperience contributed to many deaths. In addition, lack of recent diving is likely to affect current competency and appears to have been contributory to some accidents in both experienced divers and novices.

The template on which this CEA was based[ 5] is dynamic and should to be adjusted when necessary to improve its utility. In future studies, rather than utilising the combined category of organisational/training/experience/skills as defined in the template, it may be simpler and more effective to separate this into two separate categories; ‘organisational’ and ‘individual diving capacity’ with the latter incorporating an individual’s training status, experience and skill level.

PLANNING RELATED FACTORS

One quarter of the incidents involved poor planning decisions such as diving in patently adverse conditions, and/or diving solo or with an obviously ineffective buddy system. The latter is discussed in more detail in a previous paper.[ 6] Poor planning was a factor in at least four of the seventeen deaths which occurred during diver training. Dive planning should always allow for adverse events (‘Murphy’s Law’); a history of trouble-free practice of a procedure is no guarantee of lack of future problems. Past poor practice where there have been no obvious repercussions can lead to ‘normalisation of deviance’ whereby it becomes acceptable not to follow best practice and so narrows the margin of safety.[ 4]

ENVIRONMENTAL FACTORS

Various environmental factors appear to have been the triggers in almost one half of the incidents. The majority of these were associated with adverse sea conditions including, singularly or in combination, strong currents, poor visibility, rough surface conditions and underwater surge. Inexperienced divers, especially those with poor aquatic skills and lack of comfort in the aquatic environment, can more easily underestimate and be overcome by what might be mild to moderate sea conditions for those with more experience and skill. Even diving veterans can become over-confident in what they believe to be manageable conditions. In this series, inexperienced divers (defined in this study as having done fewer than 30 dives) were twice as likely to have had a conditions-related trigger than those who had done more than 30 previous dives. Sea conditions are dynamic, and appropriate local knowledge, planning and monitoring are important to minimise the potential for such problems.

EXERTION

Exertion was the trigger, or a co-trigger, in over a quarter of these fatal incidents. Dependent on the wearing of weighty equipment, diving inherently involves some level of exertion which can be multiplied manyfold by the presence of a current and rough conditions. Given the potential cardiac demands associated with diving, it is unsurprising that cardiac-related disabling injuries were six times more likely to be associated with preceding exertion than were other disabling injuries.

EQUIPMENT-RELATED PROBLEMS

Although post-incident equipment examination, when conducted, revealed faults in the equipment of one third of the victims, these appear to have been directly contributory as a trigger in a relatively small percentage (8%) of the deaths.[ 6] This is lower than the 18% previously reported for Australia (1972–2005),[ 2] 15% for the USA (1992–2003),[ 1] and 20% in the UK (1998–2009).[ 21] The apparent reduction in equipment triggers may be due in part to improvements in the design and quality of equipment or in its maintenance and appropriate use by divers over time, as well as regional differences in equipment use. A recent report from a survey of European divers indicated an overall incidence of equipment malfunction in 2.7% of 39,099 dives.[ 22] However, in the UK fatality series,[ 21] over half of the equipment-related deaths involved the use of rebreathers which are more commonly used in the UK than in Australia and many other countries. The likely over-representation of rebreathers in ‘near-misses’ reported by some Australian divers[ 23] is testament to the greater complexity of these devices, and the increased need for training, maintenance and vigilance.[ 24 - 26] Many fatal incidents involving rebreather divers appear to result from human error. However, a considerable number have also been attributed to design faults in the devices, something that is being progressively identified and addressed.[ 24 , 27 , 28]

All the equipment-related deaths in this series were preventable. For example, one inexperienced diver failed to secure his alternative-air second stage during assembly, such that it came detached during a cave dive. If the dive operator had secured the fitting, the death would likely not have occurred. Other problems arose from lack of maintenance. BCD inflator/deflator mechanisms have historically been a common cause of mishaps,[ 29] and continue to be so. Faulty submersible tank pressure gauges should have been identified well before the planned dive and repaired or replaced.

The use of pre-dive checklists should be invaluable in the prevention of a variety of diving mishaps, including those related to equipment, and should be strongly encouraged throughout the diving community, but especially among those using more complicated equipment, such as rebreathers.[ 30 - 32]

GAS SUPPLY PROBLEMS

Gas supply-related issues comprised 12% of triggers and 13% of the disabling agents in this series, usually resulting in CAGE or asphyxia. Despite the ubiquity and relatively low cost of good quality submersible tank pressure gauges, breathing gas depletion remains a problem.[ 6] This is usually a result of inexperience, inattention, poor planning or faulty equipment. All of these are preventable with appropriate equipment maintenance, careful gas supply planning and greater situational awareness prior to, and during, the diving. Technical divers need to be very careful about their choice of breathing gases to avoid using an inappropriate mixture during any part of a dive. Several deaths in this series were associated with the use of unsuitable breathing mixtures, either inadvertently or through poor planning.

Although contamination of breathing gas was not definitively identified as the direct cause of any death in a scuba diver in Australia between 2001 and 2013, it has been subsequently.[ 33] However, oil contamination was a likely contributor to one death in this series, in which the diver appeared to have become nauseated, made a rapid ascent and suffered a CAGE. Deficiencies in the required purity of the breathing air were found in over 8% of cases, so this is an area requiring vigilance. Correct compressor placement, maintenance and appropriate oversight by knowledgeable personnel are important; the addition of carbon monoxide monitoring is highly desirable.

LIMITATIONS

As with any uncontrolled case series, the collection and analysis of fatality data are subject to inevitable limitations and uncertainties associated with the incident investigations. Given that many incidents go unwitnessed, assertions in the reports are sometimes speculative. Important information may not have been available in some cases, which rendered CEA data incomplete, thus limiting the conclusions that could be drawn. Even with the use of a template, classification of cases into a sequence of five events in the CEA is imperfect and remains vulnerable to some subjectivity. The chain of successive events is a simplified representation of incidents that may be the result of parallel events and more factors than fit into the five categories used. Therefore, misclassification of factors into such categories is possible. However, this should not prevent identification of modifiable factors in what were, ultimately fatal events.

Conclusions

Chronic medical conditions, predominantly cardiac-related, are a major contributor to diving deaths. It is important that divers with such conditions, indeed all ‘older’ divers, undergo fitness-to-dive assessments, preferably with doctors with dive medical training. Other common predisposing factors involved organisational shortcomings, inadequate training, experience and skills, and poor planning and supervision. Appropriate local knowledge and monitoring are important to minimise the potential for the many incidents triggered by adverse environmental conditions, most of which involve inexperienced divers. An increased understanding of the impact of the many contributing factors by using chain of events analysis will enhance education about diving fatalities throughout the medical and diving communities. This has a considerable potential to reduce morbidity and mortality in divers.

Footnotes

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Monash University National Centre for Coronial Information for providing access to the National Coronial Information System; State and Territory Coronial Offices; various police officers, dive operators and divers who provided information on these fatalities. Acknowledgements are also due to Dr Chris Lawrence, Dr Andrew Fock, Scott Jamieson, Tom Wodak, Dr Douglas Walker and Dr Richard Harris for their contributions to the annual case series, and Assoc Prof Christopher Stevenson for his input.

Conflicts of interest and funding

Dr Lippmann is Chairman and CEO of the Australasian Diving Safety Foundation (ADSF). This study was funded by Divers Alert Network Asia-Pacific and the ADSF.

Contributor Information

John Lippmann, Australasian Diving Safety Foundation, Canterbury, Victoria, Australia; Department of Public Health and Preventive Medicine, Monash University, Victoria, Australia.

David McD Taylor, Emergency Department, Austin Hospital, Victoria, Australia; Department of Medicine, Melbourne University, Victoria, Australia.

References

- Denoble PJ, Caruso JL, de L Dear G, Vann RD. Common causes of open-circuit recreational diving fatalities . Undersea Hyperb Med. 2008;35:393–406. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lippmann J, Baddeley A, Vann R, Walker D. An analysis of the causes of compressed gas diving fatalities in Australia from 1972-2005 . Undersea Hyperb Med. 2013;40:49–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lock G. Human factors within recreational scuba diving – an application of the human factors analysis and classification system (HFACS). 21 March 2011. Available from: https://cognitasresearch.files.wordpress.com/2012/08/human-factors-in-sport-diving-incidents.pdf. [cited 2019 October 25].

- Lock G. DISMS Annual Report. Cognitas Incident and Management Ltd. 01 Feb 2015. Available from: https://cognitasresearch.files.wordpress.com/2015/02/2014dismsannualreport_final.pdf. [cited 2019 October 25].

- Lippmann J, Stevenson C, McD Taylor D, Williams J, Mohebbi M. Chain of events analysis for a scuba diving fatality . Diving Hyperb Med. 2017;47:144–54. doi: 10.28920/dhm47.3.144-154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lippmann J, Taylor D McD, Stevenson C, Gunjaca G. Scuba diver fatalities in Australia, 2001 to 2013: Diver demographics and characteristics . Diving Hyperb Med. 2020;50:105–14. doi: 10.28920/dhm50.2.105-114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Coronial Information System (NCIS) [Internet]. Administered by the Victorian Department of Justice and Regulation. Available from: http://www.ncis.org.au. [cited 2019 June 22]. [Google Scholar]

- Lippmann J, Lawrence C, Fock A, Jamieson S. Provisional report on diving-related fatalities in Australian waters 2012 . Diving Hyperb Med. 2018;48:141–67. doi: 10.28920/dhm48.3.141-167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lippmann J, Lawrence C, Fock A, Jamieson S, Harris R. Provisional report on diving-related fatalities in Australian waters 2011 . Diving Hyperb Med. 2016;46:207–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lippmann J, Lawrence C, Fock A, Wodak T, Jamieson S, Harris R, et al. Provisional report on diving-related fatalities in Australian waters 2010 . Diving Hyperb Med. 2015;45:154–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lippmann J, Lawrence C, Fock A, Wodak T, Jamieson S. Provisional report on diving-related fatalities in Australian waters 2009 . Diving Hyperb Med. 2013;43:194–217. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lippmann J, Walker D, Lawrence C, Fock A, Wodak T, Harris R, et al. Provisional report on diving-related fatalities in Australian waters 2008 . Diving Hyperb Med. 2013;43:16–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lippmann J, Walker D, Lawrence C, Fock A, Wodak T, Jamieson S. Provisional report on diving-related fatalities in Australian waters 2007 . Diving Hyperb Med. 2012;42:151–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lippmann J, Walker D, Lawrence C, Fock A, Wodak T, Jamieson S. Provisional report on diving-related fatalities in Australian waters 2006 . Diving Hyperb Med. 2011;41:70–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker D, Lippmann J, Lawrence C, Fock A, Wodak T, Jamieson S. Provisional report on diving-related fatalities in Australian waters 2005 . Diving Hyperb Med. 2010;40:131–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker D, Lippmann J, Lawrence C, Houston J, Fock A, Jamieson S. Provisional report on diving-related fatalities in Australian waters 2004 . Diving Hyperb Med. 2009;39:138–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker D, Lippmann J. Provisional report on diving-related fatalities in Australian waters 2003 . Diving Hyperb Med. 2009;39:4–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker D. Provisional report on diving-related fatalities in Australian waters 2002 . Diving Hyperb Med. 2008;38:8–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker D. Provisional report on diving-related fatalities in Australian waters 2001 . Diving Hyperb Med. 2006;36:122–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lippmann J, Taylor D. Medical conditions in scuba diving fatality victims in Australia, 2001 to 2013 . Diving Hyperb Med. 2020;50:98–104. doi: 10.28920/dhm50.2.98-104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cumming B, Peddie C, Watson J. A review of the nature of diving in the United Kingdom and of diving fatalities (1998-2009). In: Vann RD, Lang MA, editors. Recreational diving fatalities. Proceedings of the Divers Alert Network 2010 April 8–10 Workshop. Durham (NC): Divers Alert Network; 2005. p. 99–117. Available from: https://www.diversalertnetwork.org/files/Fatalities_Proceedings.pdf. [cited 2019 June 22]. [Google Scholar]

- Cialoni D, Pieri M, Balestra C, Marroni A. Dive risk factors, gas bubble formation, and decompression illness in recreational scuba diving: Analysis of DAN Europe DSL data base . Front Psychol. 2017;8:1587. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lippmann J, Taylor D McD, Stevenson C, Williams J. Challenges in profiling Australian scuba divers through surveys . Diving Hyperb Med. 2018;48:23–30. doi: 10.28920/dhm48.1.23-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deep Life Design Group. Rebreather fatal accident database to 11 July 2019, with analysis. Nassau, Bahamas: Deep Life Ltd; 2017. Available from: http://www.deeplife.co.uk/or_accident.php. [cited 2019 October 25]. [Google Scholar]

- Fock AW. Analysis of recreational closed-circuit rebreather deaths 1998–2010 . Diving Hyperb Med. 2013;43:78–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone B. Rebreather hazard analysis and human factors or how we can engineer rebreathers to be as safe as OC scuba. In: Vann RD, Denoble PJ, Pollock NW, editors . Rebreather Forum 3 Proceedings. Durham (NC): AAUS/DAN/PADI; 2013. p. 153–72 Available from: http://media.dan.org/RF3_web.pdf. [cited 2019 October 25]. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell SJ. Rebreather Forum 3 Consensus. In: Denoble PJ, Pollock NW, editors . Rebreather Forum 3 Proceedings. Durham (NC): AAUS/DAN/PADI; 2013. p. 287–8 Available from: http://media.dan.org/RF3_web.pdf. [cited 2019 October 25]. [Google Scholar]

- Vann RD, Pollock NW, Denoble PJ. Diving for science 2007. Proceedings of the American Academy of Underwater Sciences 25th Symposium. Dauphin Island (AL): AAUS; 2007. p. 101–10. [Google Scholar]

- Acott C. Evaluation of buoyancy jacket safety in 1,000 incidents . SPUMS Journal. 1996; 26: 89- 94. Available from: http://archive.rubicon-foundation.org/xmlui/bitstream/handle/123456789/6288/SPUMS_V26N2_10.pdf?sequence=1. [cited 2019 September 10]. [Google Scholar]

- Ranapurwala SI, Wing S, Poole C, Kucera KL, Marshall SW, Denoble PJ, et al. Mishaps and unsafe conditions in recreational scuba diving and pre-dive checklist use: a prospective cohort study . Inj Epidemiol. 2017;4:16. doi: 10.1186/s40621-017-0113-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranapurwala SI, Denoble PJ, Poole C, Kucera KL, Marshall SW, Wing S, et al. The effect of using a pre-dive checklist on the incidence of diving mishaps in recreational scuba diving: a cluster-randomized trial . Int J Epidemiol. 2016;45:223–31. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyv292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohler R. Failure is not an option: The importance of using a CCR checklist. In: Vann RD, Denoble PJ, Pollock NW, editors . Rebreather Forum 3 Proceedings. Durham (NC): AAUS/DAN/PADI; 2013. p. 246–51. Available from: http://media.dan.org/RF3_web.pdf. [cited 2019 October 25]. [Google Scholar]

- Coroners court of Queensland. Inquest into the death of Andrew John Thwaites. [cited 2019 November 02]. Available from: https://www.courts.qld.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0004/577093/cif-thwaites-aj-20180724.pdf.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

- Coroners court of Queensland. Inquest into the death of Andrew John Thwaites. [cited 2019 November 02]. Available from: https://www.courts.qld.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0004/577093/cif-thwaites-aj-20180724.pdf.