Abstract

Background

There is major concern about the impact of the global COVID-19 outbreak on mental health. Several studies suggest that mental health deteriorated in many countries before and during enforced isolation (ie, lockdown), but it remains unknown how mental health has changed week by week over the course of the COVID-19 pandemic. This study aimed to explore the trajectories of anxiety and depression over the 20 weeks after lockdown was announced in England, and compare the growth trajectories by individual characteristics.

Methods

In this prospective longitudinal observational study, we analysed data from the UCL COVID-19 Social Study, a panel study weighted to population proportions, which collects information on anxiety (using the Generalised Anxiety Disorder assessment) and depressive symptoms (using the Patient Health Questionnaire) weekly in the UK since March 21, 2020. We included data from adults living in England who had at least three repeated measures between March 23 and Aug 9, 2020. Analyses were done using latent growth models, which were fitted to account for sociodemographic and health covariates.

Findings

Between March 23, and Aug 9, data from over 70 000 adults were collected in the UCL COVID-19 Social Study. When including participants living in England with three follow-up measures and no missing values, our analytic sample consisted of 36 520 participants. The average depression score was 6·6 (SD=6·0, range 0–27) and the average anxiety score 5·7 (SD=5·6, range 0–21) in week 1. Anxiety and depression levels both declined across the first 20 weeks following the introduction of lockdown in England (b=–1·93, SE=0·26, p<0·0001 for anxiety; b=–2·52, SE=0·28, p<0·0001 for depressive symptoms). The fastest decreases were seen across the strict lockdown period (between weeks 2 and 5), with symptoms plateauing as further lockdown easing measures were introduced (between weeks 16 and 20). Being a woman or younger, having lower educational attainment, lower income, or pre-existing mental health conditions, and living alone or with children were all risk factors for higher levels of anxiety and depression at the start of lockdown. Many of these inequalities in experiences were reduced as lockdown continued, but differences were still evident 20 weeks after the start of lockdown.

Interpretation

These data suggest that the highest levels of depression and anxiety occurred in the early stages of lockdown but declined fairly rapidly, possibly because individuals adapted to circumstances. Our findings emphasise the importance of supporting individuals in the lead-up to future lockdowns to try to reduce distress, and highlight that groups already at risk for poor mental health before the pandemic have remained at risk throughout lockdown and its aftermath.

Funding

Nuffield Foundation, UK Research and Innovation, Wellcome Trust.

Introduction

There has been widespread concern for mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic, driven by the multiple different psychological challenges caused by the pandemic,1 and a call for urgent mental health research.2 Stay-at-home and quarantine orders issued by governments led to the largest enforced isolation period in human history. Infections and deaths from the virus led to psychological stress and bereavement. Furthermore, many individuals globally faced high levels of adversities, from challenges meeting basic needs (eg, accessing food, water, and safe accommodation) to financial problems (including job losses, income cuts, and inability to pay bills).3

Data from representative cohort studies comparing data collected before the pandemic with data collected in the first few weeks of lockdowns internationally have shown increases in average scores of psychological distress and a rise in the proportion of people experiencing clinically significant levels of mental illness.4, 5 These findings echo those from studies of previous epidemics such as the epidemic of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), during which individuals who had to quarantine experienced increases in symptoms of depression and post-traumatic stress disorder.6, 7, 8, 9 However, what remains unclear is the trajectory of mental health across the course of the COVID-19 pandemic. The studies on SARS suggested that mental health worsened during periods of quarantine or enforced isolation.6, 7 However, some sources suggest that during the COVID-19 pandemic, mental health deteriorated before the stay-at-home orders (ie, lockdowns) were introduced.10, 11, 12 Given these findings, what remains to be understood is whether mental health continued to worsen as lockdown continued, or whether there were any patterns of stabilisation or improvement. Similarly, it is unknown whether mental health improved or whether new stressors arose for individuals as lockdown measures were eased. These are important questions as understanding the patterns of mental health across lockdowns could help mental health services and voluntary organisations to plan for future waves of the virus. Furthermore, understanding how humans respond to periods of enforced isolation could enhance our understanding of the effect of social isolation on mental health.

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

We searched PubMed for articles published in English between Jan 1, 2020, and Sept 14, 2020, using the following keywords: “COVID*” OR “coronavirus” and “anxiety” OR “depression” OR “mental health” OR “mental illness” OR “distress”. Studies using data from representative cohort studies revealed the substantial impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on levels of depression, anxiety, and mental distress, showing increases in average scores of symptoms of psychological distress from before the pandemic to during the pandemic, and a rise in the proportion of people experiencing clinically significant levels of mental illness. But there was a gap in the evidence in understanding how mental health changed week by week over the course of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Added value of this study

This study shows that mental health was adversely affected in the 20 weeks following the start of the first lockdown in England. However, since the commencement of the first lockdown, many people began to experience improvements in mental health. Many known risk factors for poorer mental health were apparent early in lockdown, such as women, younger adults, and individuals with lower educational attainment. As mental health improved, the difference between these vulnerable groups and people without these risk factors reduced but was still evident 20 weeks after the start of lockdown.

Implications of all the available evidence

Our findings, together with previous studies comparing populations before and after the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, emphasise the importance of supporting individuals to try to reduce distress early in a pandemic. Many inequalities in mental health experiences persisted and emotionally vulnerable groups have remained at risk throughout lockdown and its aftermath. These groups could benefit from more targeted mental health support as the pandemic continues.

Finally, another important question is whether some individuals are more adversely affected by the COVID-19 pandemic than others. Inequalities in mental health have been well reported over the previous decade. Women, younger adults, individuals with lower educational attainment and socioeconomic position, individuals from Black, Asian, and minority ethnic (BAME) backgrounds, and individuals living alone are more likely to experience higher levels of depression and anxiety than men, older adults, individuals with higher educational attainment and socioeconomic position, individuals from white backgrounds, and individuals living with others.13, 14 Findings from previous epidemics have suggested that many of these factors have also been risk factors for worse mental health during periods of isolation,15 and data about the COVID-19 pandemic have echoed these findings.16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21 Similarly, there has been some indication that pre-existing psychiatric conditions are a risk factor for poorer mental health outcomes,22 which has also been echoed by data from the COVID-19 pandemic.16, 17 However, previous research has focused on cross-sectional data or discrete timepoints during the pandemic. The effect of these risk factors on the trajectories of mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic remains unknown. Identifying such risk factors is important to ascertain who is most in need of support both during the ongoing pandemic and in preparing for future pandemics.

Therefore, this study had two main aims: first, to explore trajectories of anxiety and depressive symptoms over the strict lockdown period and as lockdown was eased; and second, to identify who was most at risk of poorer trajectories of mental health across this period.

Methods

Study design and participants

Data were drawn from the UCL COVID-19 Social Study, a large prospective panel study of the psychological and social experiences of over 70 000 adults (aged 18 years and older) in the UK during the COVID-19 pandemic. The study commenced on March 21, 2020, involving online weekly data collection from participants during the COVID-19 pandemic. The study has a heterogeneous sample that was recruited using three primary approaches. First, snowballing was used; this sampling technique included promoting the study through existing networks and mailing lists (including large databases of adults who had previously consented to be involved in health research across the UK such as UCL BioResource and HealthWise Wales, through local authorities and mutual aid groups across the UK, and via the UKRI Mental Health Research Networks), print and digital media coverage, and social media. Second, more targeted recruitment was done through partnership work with recruitment companies (Find Out Now, SEO Works, FieldworkHub, and Optimal Workshop) focusing on individuals from a low-income background, individuals with no or few educational qualifications, and individuals who were unemployed. Third, the study was promoted to vulnerable groups, including adults with pre-existing mental illness, older adults (>60 years old), and carers, via partnerships with third sector organisations within the UKRI MARCH Mental Health Research Network. Active recruitment was done for the first 8 weeks of the study. The study was approved by the UCL Research Ethics Committee and all participants gave written informed consent. No participant received any payment for participation. Full details on the recruitment, sampling, retention, and weighting of the sample is available in the appendix (p 4) and in the study user guide.

For these analyses, to examine trajectories of mental health in relation to specific measures relating to lockdown, we focused solely on participants who lived in England (n=59 348). We included participants who had at least three repeated measures between March 23, 2020, when the first lockdown started in the UK, and Aug 9, 2020 (20 weeks later). These criteria provided us with data from 40 520 respondents who were followed up for a maximum of 20 weeks since the beginning of the lockdown. 4000 (10%) of these participants withheld data or preferred not to self-identify on demographic factors including gender and income and were therefore excluded from our analysis (the demographics of these participants are shown on appendix p 3), providing a final analytic sample size of 36 520.

The research questions in the COVID-19 Social Study built on patient and public involvement as part of the UKRI MARCH Mental Health Research Network, which highlighted priority research questions and measures for this study. Patients and the public were additionally involved in the recruitment of participants and the dissemination of findings.

Procedures

Data were collected via the online survey application REDCap. Anxiety was measured using the Generalised Anxiety Disorder assessment (GAD-7), a well validated 7-item tool used to screen and diagnose generalised anxiety disorder in clinical practice and research23 with 4-point responses ranging from “not at all” to “nearly every day”. Scores of 0–4 are thought to represent minimal anxiety, 5–9 mild anxiety, 10–14 moderate anxiety, and 15–21 severe anxiety.23 Depressive symptoms were measured using the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9), a standard 9-item instrument for diagnosing depression in primary care,24 with 4-point responses ranging from “not at all” to “nearly every day”. Scores of 0–4 suggest minimal depression, 5–9 mild depression, 10–14 moderate depression, 15–19 moderately severe depression, and 20–27 severe depression.25 The validated measures of both the GAD-7 and PHQ-9 ask respondents to focus on the past 2 weeks, but because the COVID-19 Social Study involved weekly reassessments, we asked participants to focus just on the past week.

We included sociodemographic variables as time-invariant covariates, namely, gender (men vs women), age groups (18–29 years, 30–45 years, 46–59 years, and 60 years or older), ethnicity (white vs BAME), education (General Certificate of Secondary Education or lower education [equivalent to education to the age of 16 years], A levels or equivalent [equivalent to education to the age of 18 years], undergraduate degree or above [further education after the age of 18 years]), income (household income <£30 000 vs ≥£30 000), and living arrangement (alone, living with others but no children in the household, living with others including children in the household). We assessed diagnosed mental illness (as another time-invariant covariate) by asking participants “Do you have any of the following medical conditions”, with the responses being “clinically-diagnosed depression”, “clinically-diagnosed anxiety”, and “another clinically-diagnosed mental health problem”. Participants could select as many categories as applied and the responses were binarised into “diagnosed mental illness” or “no diagnosed mental illness”. Participants were also asked whether they had had COVID-19 (“yes, diagnosed and recovered/still ill”, “not formally diagnosed but suspected”, or “not that I know of/no”). However, only a very small percentage of the sample (0·02–0·88% each week) reported being formally diagnosed with a test due to limitations on testing in the early months of the pandemic; therefore, we did not include experience of COVID-19 in the analyses. Further detail on the measures is available in the study user guide.

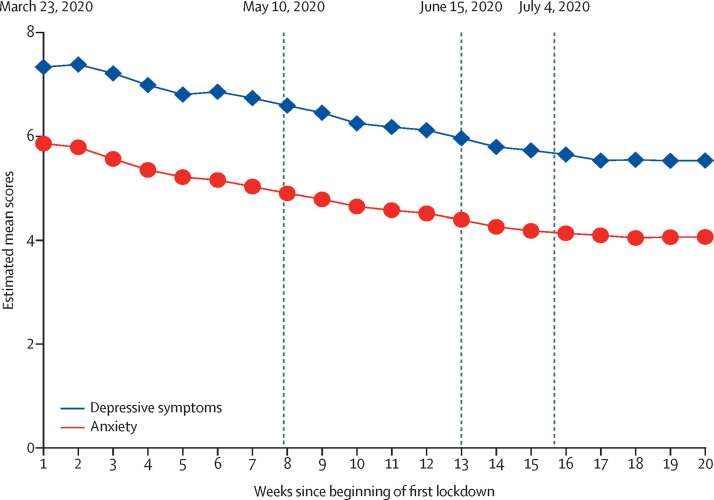

The timeline of the key dates of lockdown restrictions in England is shown in figure 1 and a description of the specific measures at key dates is shown in the appendix (p 1).

Figure 1.

Predicted growth trajectories of estimated mean anxiety and depressive symptom scores

Scores on anxiety were measured using the Generalised Anxiety Disorder assessment (range of scores: 0–21) and scores on depressive symptoms were measured using the Patient Health Questionnaire (range of scores: 0–27). On March 23, the first lockdown commenced in England. On May 10, it was announced that strict lowdown was being eased. On June 15, non-essential retail was reopened. On July 4, further public amenities were reopened.

Statistical analysis

Data were analysed using latent growth modelling. We used unspecified latent growth modelling, which allows the shape of growth trajectories to be determined by data by using free time scores. Given that anxiety and depressive symptoms might be related, these two outcomes were modelled simultaneously (multiprocess latent growth modelling). An illustration of the model specification can be found in the appendix (p 1). The general equations were presented as:

| 1-1 |

| 1-2 |

| 1-3 |

Equation 1–1 addressed intraindividual changes. (outcome m [depressive symptoms or anxiety] for the individual i at time t) was a function of the intercept and slope. values were time scores. was the residual term. Equation 1–2 and equation 1–3 addressed inter-individual differences in the intercept and slope. and represented the population average intercept and slope for outcome m. Xk represented a vector of time-invariant variables that hypothetically influence the intercept and slope. and were parameter residuals. The predicted growth trajectories were based on the model estimates. Except for the grouping variable, all variables were set to the sample means.

To account for the non-random nature of the sample, the sample was weighted by the proportions of gender, age, ethnicity, and education obtained from the Office for National Statistics.26 The correlation between outcome measures is shown in the appendix (p 4). Unweighted and weighted descriptive statistics by week are shown in the appendix (p 4). Descriptive analyses were done using Stata version 15. The latent growth models were fitted in Mplus version 8.

Role of the funding source

The funders of the study had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report. All authors had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication. All researchers listed as authors are independent from the funders and all final decisions about the research were taken by the investigators and were unrestricted.

Results

Between March 23, and Aug 9, data from over 70 000 adults were collected in the UCL COVID-19 Social Study. After excluding participants with less than two follow-ups or with missing values, our analytic sample comprised 36 520 participants, providing 436 522 observations (12 repeated measures per participant on average, ranging from three to 20). The distribution of follow-up weeks is shown in the appendix (p 3).

27 699 (76%) of the 36 520 participants were women and there was an over-representation of people with an undergraduate degree or above (n=25 653, 70%) and an under-representation of people from BAME backgrounds (n=1839, 5%; table 1 ). After weighting, the sample reflected population proportions, with 18 643 (51%) women, 12 670 (35%) participants with a degree or above, and 5311 (14%) participants with BAME ethnicity. 7270 (20%) participants of the weighted sample reported having a diagnosed mental illness.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of the explanatory variables for the 36 520 participants at their baseline assessment

| Raw data | Weighted data | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Women | 27 699 (75·8%) | 18 643 (51·0%) |

| Men | 8821 (24·2%) | 17877 (49·0%) |

| Age, years | ||

| 18–29 | 2730 (7·5%) | 7130 (19·5%) |

| 30–45 | 10 649 (29·2%) | 9643 (26·4%) |

| 46–59 | 12 048 (33·0%) | 8805 (24·1%) |

| ≥60 | 11 093 (30·4%) | 10 943 (30·0%) |

| Ethnicity | ||

| White | 34 681 (95·0%) | 31 209 (85·5%) |

| Black, Asian, and minority | 1839 (5·0%) | 5311 (13·5%) |

| Education | ||

| General Certificate of Secondary Education or below | 4731 (13·0%) | 11 848 (32·4%) |

| A levels or equivalent | 6136 (16·8%) | 12 003 (32·9%) |

| Undergraduate degree or above | 25 653 (70·2%) | 12 670 (34·7%) |

| Household income | ||

| <£30 000 | 13 417 (36·7%) | 16 847 (46·1%) |

| ≥£30 000 | 23 103 (63·3%) | 19 673 (53·9%) |

| Living status | ||

| Alone | 7195 (19·7%) | 6684 (18·3%) |

| With others, but no children | 19 411 (53·2%) | 20 483 (56·1%) |

| With others, including children | 9914 (27·1%) | 9352 (25·6%) |

| Diagnosed mental illness | ||

| Yes | 6679 (18·3%) | 7270 (19·9%) |

| No | 29 841 (81·7%) | 29 250 (80·1%) |

Data are n (%).

In week 1, the average score on the GAD-7 was 5·7 (SD=5·6; range 0–21; table 2 ). 9123 (53%) participants had a score of 0–4 suggesting minimal anxiety, 4111 (24%) had a score of 5–9 indicating mild anxiety, 2092 (12%) had a score of 10–14 indicating moderate anxiety, and 1764 (10%) had a score of 15–21 indicating severe anxiety (appendix p 10). The average score on the PHQ-9 was 6·6 (SD=6·0) in week 1 (range 0–27; table 2). 8228 (48%) participants had a score of 0–4 suggesting minimal depression, 4578 (27%) had a score of 5–9 indicating mild depression, 2218 (13%) had a score of 10–14 indicating moderate depression, 1290 (8%) had a score of 15–19 indicating moderately severe depression, and 776 (5%) had a score of 20–27 indicating severe depression. Among the 3168 participants with a pre-existing diagnosed mental illness, 1929 (61%) had a score of 10 or higher indicating moderate or severe depression (average score 12·3 [SD=6·7]) and 1703 (54%) had a score of 10 or higher indicating at least moderate anxiety (average score 10·6 [SD=5·8]; table 2). Among the 13 923 participants without a pre-existing diagnosed mental illness, 2153 (16%) had anxiety (average score 4·6 [SD=4·9]) and 2356 (17%) depression (average score 5·1 [SD=5·0]). More details on symptoms by week are shown in the appendix (p 10).

Table 2.

Levels of anxiety and depressive symptoms in the sample in week 1 (weighted)

|

Anxiety |

Depressive symptoms |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Number of participants with a score of 10 and above (%) | Mean (SD) | Number of participants with a score of 10 and above (%) | ||

| Total sample | 5·7 (5·6) | 3856 (22·6%) | 6·6 (6·0) | 4285 (25·1%) | |

| Gender | |||||

| Women | 7·2 (7·3) | 2616 (31·5%) | 7·5 (7·7) | 2649 (31·9%) | |

| Men | 4·3 (3·5) | 1240 (14·1%) | 5·4 (4·0) | 1635 (18·6%) | |

| Age, years | |||||

| 18–29 | 7·6 (3·8) | 1054 (34·4%) | 8·3 (4·0) | 1003 (32·7%) | |

| 30–45 | 7·2 (6·2) | 1421 (30·4%) | 7·5 (6·5) | 1448 (30·9%) | |

| 46–59 | 5·8 (6·4) | 875 (21·4%) | 6·9 (7·3) | 1138 (27·8%) | |

| ≥60 | 3·2 (4·1) | 505 (9·6%) | 4·2 (4·7) | 697 (13·3%) | |

| Ethnicity | |||||

| White | 5·7 (5·9) | 3337 (22·7%) | 6·4 (6·4) | 3697 (25·1%) | |

| Black, Asian, and minority | 5·7 (3·2) | 519 (21·8%) | 6·9 (3·3) | 588 (24·7%) | |

| Education | |||||

| General Certificate of Secondary Education or below | 5·4 (3·7) | 1187 (21·5%) | 6·4 (4·0) | 1439 (26·0%) | |

| A levels or equivalent | 6·0 (4·2) | 1414 (25·2%) | 7·0 (4·7) | 1579 (28·1%) | |

| Undergraduate degree or above | 5·6 (7·3) | 1255 (21·1%) | 6·0 (7·5) | 1267 (21·3%) | |

| Household income | |||||

| <£30 000 | 5·9 (5·2) | 2018 (25·2%) | 7·3 (5·9) | 2496 (31·2%) | |

| ≥£30 000 | 5·5 (5·8) | 1838 (20·2%) | 5·7 (5·9) | 1788 (19·7%) | |

| Living status | |||||

| Alone | 5·1 (5·4) | 648 (20·5%) | 7·1 (6·6) | 925 (29·3%) | |

| With others, but no children | 5·3 (5·3) | 1998 (20·6%) | 5·9 (5·6) | 2134 (22·0%) | |

| With others, including children | 6·9 (6·1) | 1210 (28·5%) | 7·3 (6·4) | 1226 (28·8%) | |

| Diagnosed mental illness | |||||

| Yes | 10·6 (5·8) | 1703 (53·7%) | 12·3 (6·7) | 1929 (60·9%) | |

| No | 4·6 (4·9) | 2153 (15·5%) | 5·1 (5·0) | 2356 (16·9%) | |

Data are mean (SD) or n (%). Not all participants started the study in week 1, so this table does not represent the full number of participants included in the statistical sample. Scores on depressive symptoms were measured using the Patient Health Questionnaire (range of scores: 0–27). Scores of 0–4 suggest minimal depression, 5–9 mild depression, 10–14 moderate depression, 15–19 moderately severe depression, and 20–27 severe depression. Scores on anxiety were measured using the Generalised Anxiety Disorder assessment (range of scores: 0–21). Scores of 0–4 suggest minimal anxiety, 5–9 mild anxiety, 10–14 moderate anxiety, and 15–21 severe anxiety.

Over the 20 weeks following the introduction of lockdown, there was a significant decrease in both anxiety (b=–1·93, SE=0·26, p<0·0001) and depressive symptoms (b=–2·52, SE=0·28, p<0·0001) both during the strict lockdown period and the period in which restrictions were eased from May 10, 2020 (figure 1). The growth trajectories of anxiety and depressive symptoms showed a non-linear pattern (appendix p 11). The slopes varied across different stages. For instance, there was a sharp decline in depressive symptoms and anxiety between weeks 2 and 5 during the strict lockdown period, but little change was observed between weeks 16 and 20 after substantial easing of lockdown had taken place. The growth trajectories of anxiety and depressive symptoms were positively associated with each other as evidenced by the significant covariance between the two intercepts (20·46, p<0·0001) and slopes (18·64, p<0·0001; appendix p 11).

At the beginning of the lockdown, women, younger adults, people with lower levels of educational attainment, people from lower-income households, and people with pre-existing mental health conditions reported higher levels of anxiety and depressive symptoms (table 3 ). Individuals living with children had higher levels of anxiety (b=0·70, p<0·0001) but lower levels of depressive symptoms (b=–0·37, p=0·029) than individuals living alone, whereas individuals living alone had higher levels of depressive symptoms but similar levels of anxiety to people living with other adults but without children. No evidence was found that ethnicity was associated with baseline mental health (b=0·19, p=0·434 for anxiety; b=0·45, p=0·064 for depressive symptoms).

Table 3.

Estimated effects of the covariates on the intercepts and slopes from the conditional multiprocess latent growth model

|

Anxiety |

Depressive symptoms |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| b (SE) | p value | b (SE) | p value | |

| Predictors of the intercept | ||||

| Women (vs men) | 1·34 (0·13) | <0·0001 | 1·08 (0·13) | <0·0001 |

| Age: 30–45 years (vs 18–29 years) | −1·38 (0·22) | <0·0001 | −1·86 (0·23) | <0·0001 |

| Age: 46–59 years (vs 18–29 years) | −2·63 (0·23) | <0·0001 | −2·86 (0·24) | <0·0001 |

| Age: ≥60 years (vs 18–29 years) | −4·02 (0·23) | <0·0001 | −4·57 (0·25) | <0·0001 |

| Ethnicity: Black, Asian, and minority (vs white) | 0·19 (0·24) | 0·434 | 0·45 (0·24) | 0·064 |

| Education: low (vs high) | 0·75 (0·14) | <0·0001 | 1·13 (0·16) | <0·0001 |

| Education: medium (vs high) | 0·50 (0·13 | <0·0001 | 0·90 (0·13) | <0·0001 |

| Household income <£30 000 (vs ≥£30 000) | 0·65 (0·12) | <0·0001 | 1·09 (0·13) | <0·0001 |

| Living with others, but no children (vs alone) | 0·16 (0·13) | 0·212 | −0·81 (0·14) | <0·0001 |

| Living with others, including children (vs alone) | 0·70 (0·15) | <0·0001 | −0·37 (0·17) | 0·029 |

| Mental health diagnosis (vs none) | 5·18 (0·18) | <0·0001 | 5·83 (0·18) | <0·0001 |

| Predictors of the slope | ||||

| Women (vs men) | −0·86 (0·13) | <0·0001 | −0·63 (0·14) | <0·0001 |

| Age: 30–45 years (vs 18–29 years) | 0·98 (0·28) | <0·0001 | 1·40 (0·29) | <0·0001 |

| Age: 46–59 years (vs 18–29 years) | 1·50 (0·27) | <0·0001 | 1·63 (0·29) | <0·0001 |

| Age: ≥60 years (vs 18–29 years) | 1·75 (0·27) | <0·0001 | 2·06 (0·28) | <0·0001 |

| Ethnicity: Black, Asian, and minority (vs white) | 0·18 (0·27) | 0·507 | −0·01 (0·29) | 0·980 |

| Education: low (vs high) | −0·45 (0·15) | 0·003 | −0·60 (0·16) | <0·0001 |

| Education: medium (vs high) | −0·23 (0·14) | 0·112 | −0·39 (0·15) | 0·011 |

| Household income <£30 000 (vs ≥£30 000) | 0·17 (0·13) | 0·186 | 0·13 (0·14) | 0·342 |

| Living with others, but no children (vs alone) | −0·27 (0·13) | 0·036 | 0·04 (0·14) | 0·773 |

| Living with others, including children (vs alone) | −0·93 (0·18) | <0·0001 | −0·63 (0·19) | 0·0001 |

| Mental health diagnosis (vs none) | −0·32 (0·20) | 0·117 | 0·28 (0·22) | 0·193 |

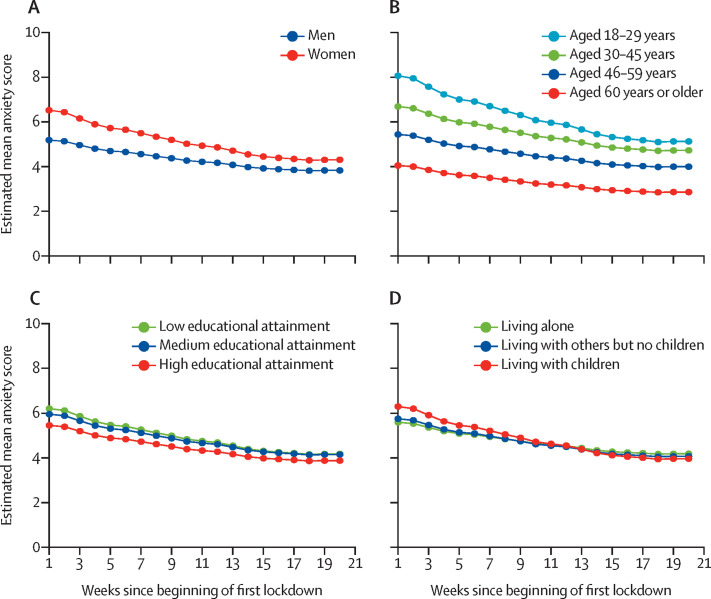

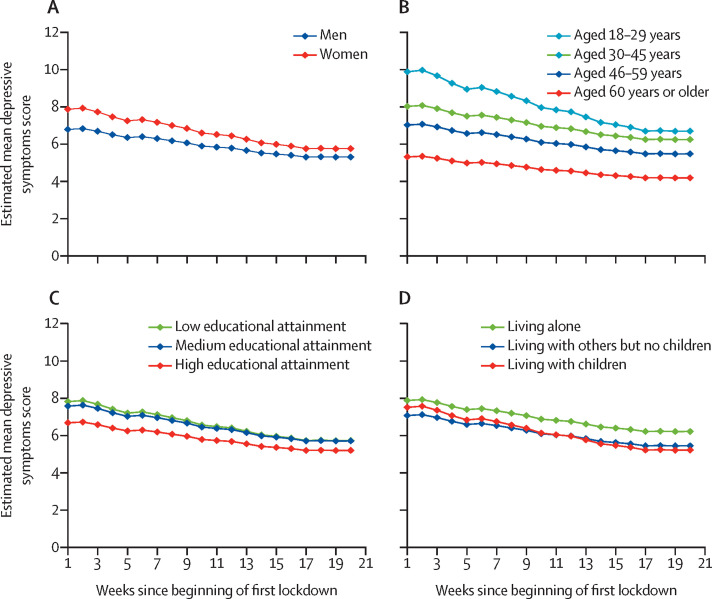

Across the 20 weeks, women, younger adults, people with lower levels of educational attainment, and people living with children had faster improvements in anxiety and depressive symptoms than men, older adults, people with higher levels of educational attainment, and people living without children, narrowing some of the gaps in experiences present at the start of lockdown (table 3; Figure 2, Figure 3 ). People living alone had the same trajectories of depressive symptoms as did people living with other adults but no children (living with other adults but no children vs living alone: b=0·04, p=0·77), but their overall levels of depressive symptoms were consistently higher. There was no evidence that the rate of change was associated with ethnicity, household income, or pre-existing mental health conditions. Inequalities by gender, age, education, income, and mental health were all still present at the end of the 20 weeks. For further graphs, see appendix p 2.

Figure 2.

Predicted growth trajectories of mean anxiety scores by individual characteristics

Scores on anxiety were measured using the Generalised Anxiety Disorder assessment (range of scores: 0–21). Graphs for anxiety scores by other individual characteristics are shown in the appendix (p 2).

Figure 3.

Predicted growth trajectories of mean depressive symptom scores by individual characteristics

Scores on depressive symptoms were measured using the Patient Health Questionnaire (range of scores: 0–27). Graphs for depressive symptoms scores by other individual characteristics are shown in the appendix (p 2).

Discussion

This study explored trajectories of anxiety and depression across the first 20 weeks following the start of the first lockdown response to the COVID-19 pandemic in England. Results show that anxiety and depressive symptoms both declined across the first 20 weeks following the introduction of lockdown in England. The fastest decreases were seen across the strict lockdown period, with symptoms plateauing as further lockdown easing measures were introduced. Being female or younger, having lower educational attainment, lower income, or pre-existing mental health conditions, and living alone or with children were all risk factors for higher levels of anxiety and depressive symptoms at the start of lockdown. Many of these inequalities in experiences were reduced as lockdown continued, but differences were still evident 20 weeks after the start of lockdown.

The study did not use a random population sample, and therefore our reported statistics are not presented as prevalence levels for anxiety or depressive symptoms. However, this study does give detailed time series data on trajectories of mental health during lockdown. The findings of improvements, in particular across the early weeks following the introduction of lockdown measures in England, are echoed by polling data showing improvements in many aspects of mood in repeated cross-sectional samples over the same period.10, 11 The fact that levels of mental health did not continue to worsen in this period is slightly at odds with data from previous epidemics, in which mental health was found to worsen during (or as a result of) quarantine.15 However, there are several key differences between this pandemic and previous epidemics. First, for the majority of people in England during lockdown, some trips outside of the home were permissible, whereas previous studies looked at quarantines in which movement was more restricted, albeit typically for much smaller numbers of people. The more restricted quarantines of previous epidemics might have led to a harsher psychological experience. Second, there was substantial previous warning in England that a lockdown was likely to happen given patterns in other European countries. Individuals appeared to have become psychologically affected before the lockdown announcement (and many individuals self-isolated voluntarily before lockdown officially started). This anticipation means that much of the psychological toll was already being experienced before individuals were forced to isolate.15 Finally, the proliferation of online and home-based leisure activities and the extensive use of virtual and digital communication during the COVID-19 pandemic might have helped to ease the burden of lockdown itself, in contrast to previous epidemics in which the fear of missing out was reported to be a challenge.27 Indeed, fear of missing out (which is associated with depression, distraction, and somatic symptoms28) might also have been reduced because of the global nature of this pandemic, compared with the restricted nature of quarantines in previous pandemics. The improvements in mental health over this strict lockdown period suggest a process of adaptation that bears similarities to literature on other types of isolation: for example, some studies of incarceration have shown that depression levels can stabilise and even decrease month after month as new coping strategies emerge.29 It is further possible that measures to safeguard jobs and finances taken in the UK might have helped to reduce specific anxieties. The lockdown itself might also have reduced worries about individuals or their friends or families catching the virus, especially after the first 2 weeks of lockdown when individuals could be more confident that they were outside of the incubation period.

This study also found substantial differences in experiences of mental health across the first 20 weeks following the introduction of lockdown among different groups. Previous studies during the COVID-19 pandemic have already highlighted that women and younger adults had higher levels of anxiety and depression than men and older adults,4, 17, 18 but our data show that these groups have also had faster improvements in their symptoms. This finding could indicate a more challenging psychological experience early on in lockdown (eg, as many women balanced child care and working from home) or a higher initial reactivity to events among these groups. By contrast, adults living alone had consistently worse levels of depressive symptoms, which could be related to higher levels of loneliness due to social restrictions.30 However, individuals living with children had higher levels of anxiety and depressive symptoms initially than individuals living with other adults, but a faster rate of improvement, potentially due to the growing public awareness of research suggesting that children were less affected by COVID-19.31 Similarly, individuals with lower household income had consistently worse mental health than individuals with a higher household income, which has been proposed to be linked to higher experiences of adversities such as job losses, decreases in household income, and challenges to pay bills.3 But differences in mental health at baseline are probably attributable to pre-existing social inequalities that have been exacerbated over the past decade.32 Although we found that individuals with mental illness had higher levels of depressive symptoms and anxiety at the start of lockdown (which is echoed in COVID-19 studies33, 34, 35 from various countries), they had the same trajectories over the subsequent weeks. This finding suggests that mental illness did not necessarily predispose individuals to greater levels of emotional reactivity. It is possible that previous experience of mental illness or social isolation caused by previous mental illness meant individuals had experience of some of the requirements of lockdown or of applying coping strategies in stressful situations. But lockdown might also have enabled unhealthy coping strategies, so these hypotheses remain to be explored. Furthermore, future studies are recommended to look at specific types of psychiatric diagnoses in relation to mental health to identify whether particular psychopathologies are associated with poorer trajectories over the course of the pandemic. Our models suggested that ethnicity was not a risk factor for worse mental health. But the models adjusted simultaneously for multiple demographic factors including socioeconomic position, and socioeconomic position was related to poorer psychological experiences. Individuals from ethnic minority groups are disproportionately more likely to be from lower socioeconomic groups,36 so they might still have been disproportionately affected. We used some binary categories in our analyses for ethnicity (and for other variables such as gender), but we recognise that such labels do not fully capture the experiences of different groups. Ethnic minority groups were under-represented in our data (although we did weight to increase the proportion of their responses). As a result, we did not have sufficient statistical power to look at the experiences of specific ethnic groups and our analysis did not explore the experiences of individuals with non-binary gender identities, but we recognise the need for and encourage and support future research on these areas.

This study had several limitations. It is possible that the study did not adequately cover the full range of experiences. Therefore, this study does not claim to provide data on prevalence of mental illness during the pandemic. Furthermore, as the study was internet based, participants without home access to internet were not represented. We also asked about symptoms of anxiety and depression over the past week rather than past 2 weeks because our reassessments were weekly. Although this change has precedence both in previous studies and clinical screening, it underlines that the precise values on the scale cannot be taken as national averages for anxiety and depression during the pandemic. Additionally, we relied on participants’ self-report of diagnosed mental illness and were unable to confirm diagnoses, or identify specifically the type of problem with which participants had previously been diagnosed. Because of the substantial overlap between participants reporting diagnoses of depression and diagnoses of anxiety, we did not look at the unique contribution of each condition to trajectories of symptoms across lockdown, or at how specific symptoms (such as thoughts of death) might have been affected. As we asked about current diagnoses, we do not know how trajectories were affected by mental illness, specific psychological symptoms, or subclinical symptomatology in the weeks or months preceding lockdown; and as participants entered the study continuously throughout the 20-week follow-up period reported here, it is possible that some diagnoses had been made since lockdown began. Additionally, this study involved repeated weekly assessment of mental health, so regression to the mean is a possible source of bias. However, if regression to the mean occurred, we might have expected it to work both ways, with the higher anxiety and depressive symptom scores declining and the lower scores increasing. Yet all groups showed decreases across the study period. Furthermore, a decrease in average scores due to non-random attrition is unlikely to have substantially biased results as all participants in the analysis provided at least three datapoints, so their trajectories were estimated even in the absence of complete data. Our study followed people across the period from spring to summer in England so the contribution of seasonality to findings remains to be explored, although the results presented here suggest effects above and beyond usual fluctuations.37 Future studies could also consider how geographical factors including location within the UK, level of urbanisation, and area deprivation might have moderated psychological experiences during lockdown and whether experience of COVID-19 could have affected psychological response.

Overall, these findings suggest that the highest levels of depression and anxiety in England were in the early stages of lockdown but declined fairly rapidly following the introduction of lockdown, with improvements continuing as lockdown easing measures were introduced and then plateauing after the first 4 months. Many known risk factors for poorer mental health were associated with inequalities in mental health at the start of lockdown. However, some groups, including women, younger adults, and individuals with lower educational attainment, had faster improvements in symptoms, thereby reducing the differences between these vulnerable groups and other groups over time. Nevertheless, many inequalities in mental health experiences (such as inequalities by age and gender) did remain and emotionally vulnerable groups (such as individuals with existing mental health conditions or individuals living alone) have remained at risk throughout lockdown and its aftermath. As countries face potential future lockdowns, these data emphasise the importance of supporting individuals in the lead-up to lockdown to try to reduce distress; yet these data also suggest that individuals might be able to adapt relatively fast to the new psychological demands of life in lockdown. But because inequalities in mental health have persisted, it is key to find ways of supporting vulnerable groups during this pandemic.

Data sharing

Anonymous data will be made publicly available at the end of 2021.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

This COVID-19 Social Study was funded by the Nuffield Foundation (WEL/FR-000022583), but the views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the foundation. The study was also supported by the MARCH Mental Health Network funded by UK Research and Innovation (ES/S002588/1), and by the Wellcome Trust (221400/Z/20/Z). DF was funded by the Wellcome Trust (205407/Z/16/Z). The researchers are grateful for the support of several organisations with recruitment efforts, including the UKRI Mental Health Networks, Find Out Now, UCL BioResource, SEO Works, FieldworkHub, and Optimal Workshop. The study was also supported by HealthWise Wales, the Health and Care Research Wales initiative led by Cardiff University in collaboration with SAIL Databank developed by Swansea University.

Contributors

DF, AS, and FB conceived and designed the study. FB analysed the data and DF wrote the first draft. All authors provided critical revisions. All authors read and approved the submitted manuscript. DF and FB accessed and verified the data.

Declaration of interests

We declare no competing interests.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Holmes EA, O'Connor RC, Perry VH, et al. Multidisciplinary research priorities for the COVID-19 pandemic: a call for action for mental health science. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7:547–560. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30168-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mahase E. Covid-19: mental health consequences of pandemic need urgent research, paper advises. BMJ. 2020;369 doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wright L, Steptoe A, Fancourt D. Are we all in this together? Longitudinal assessment of cumulative adversities by socioeconomic position in the first 3 weeks of lockdown in the UK. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2020;74:683–688. doi: 10.1136/jech-2020-214475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pierce M, Hope H, Ford T, et al. Mental health before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: a longitudinal probability sample survey of the UK population. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7:883–892. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30308-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shanahan L, Steinhoff A, Bechtiger L, et al. Emotional distress in young adults during the COVID-19 pandemic: evidence of risk and resilience from a longitudinal cohort study. Psychol Med. 2020 doi: 10.1017/S003329172000241X. published online June 23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hawryluck L, Gold WL, Robinson S, Pogorski S, Galea S, Styra R. SARS control and psychological effects of quarantine, Toronto, Canada. Emerg Infect Dis. 2004;10:1206–1212. doi: 10.3201/eid1007.030703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reynolds DL, Garay JR, Deamond SL, Moran MK, Gold W, Styra R. Understanding, compliance and psychological impact of the SARS quarantine experience. Epidemiol Infect. 2008;136:997–1007. doi: 10.1017/S0950268807009156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mihashi M, Otsubo Y, Yinjuan X, Nagatomi K, Hoshiko M, Ishitake T. Predictive factors of psychological disorder development during recovery following SARS outbreak. Health Psychol. 2009;28:91–100. doi: 10.1037/a0013674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu X, Kakade M, Fuller CJ, et al. Depression after exposure to stressful events: lessons learned from the severe acute respiratory syndrome epidemic. Compr Psychiatry. 2012;53:15–23. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2011.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.YouGov Britain's mood, measured weekly. https://yougov.co.uk/topics/science/trackers/britains-mood-measured-weekly

- 11.Layard R, Clark A, De Neve J-E, et al. When to release the lockdown: a wellbeing framework for analysing costs and benefits. http://ftp.iza.org/dp13186.pdf

- 12.Mental Health Foundation Millions of UK adults have felt panicked, afraid and unprepared as a result of the coronavirus pandemic—new poll data reveal impact on mental health. 2020. https://www.mentalhealth.org.uk/news/millions-uk-adults-have-felt-panicked-afraid-and-unprepared-result-coronavirus-pandemic-new

- 13.Ansseau M, Fischler B, Dierick M, Albert A, Leyman S, Mignon A. Socioeconomic correlates of generalized anxiety disorder and major depression in primary care: the GADIS II study (Generalized Anxiety and Depression Impact Survey II) Depress Anxiety. 2008;25:506–513. doi: 10.1002/da.20306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hölzel L, Härter M, Reese C, Kriston L. Risk factors for chronic depression—a systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2011;129:1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2010.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brooks SK, Webster RK, Smith LE, et al. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of the evidence. Lancet. 2020;395:912–920. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30460-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kwong ASF, Pearson RM, Adams MJ, et al. Mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic in two longitudinal UK population cohorts. medRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.06.16.20133116. published June 18. (preprint) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Solomou I, Constantinidou F. Prevalence and predictors of anxiety and depression symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic and compliance with precautionary measures: age and sex matter. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17 doi: 10.3390/ijerph17144924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pieh C, Budimir S, Probst T. The effect of age, gender, income, work, and physical activity on mental health during coronavirus disease (COVID-19) lockdown in Austria. J Psychosom Res. 2020;136 doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2020.110186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pierce M, Hope H, Ford T, et al. Mental health before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: a longitudinal probability sample survey of the UK population. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7:883–893. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30308-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang C, Pan R, Wan X, et al. Immediate psychological responses and associated factors during the initial stage of the 2019 coronavirus disease (COVID-19) epidemic among the general population in China. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17 doi: 10.3390/ijerph17051729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ausín B, González-Sanguino C, Castellanos MÁ, Muñoz M. Gender-related differences in the psychological impact of confinement as a consequence of COVID-19 in Spain. J Gend Stud. 2020 doi: 10.1080/09589236.2020.1799768. published online Aug 4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jeong H, Yim HW, Song Y-J, et al. Mental health status of people isolated due to Middle East Respiratory Syndrome. Epidemiol Health. 2016;38 doi: 10.4178/epih.e2016048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, Löwe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1092–1097. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Löwe B, Kroenke K, Herzog W, Gräfe K. Measuring depression outcome with a brief self-report instrument: sensitivity to change of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) J Affect Disord. 2004;81:61–66. doi: 10.1016/S0165-0327(03)00198-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL. The PHQ-9: a new depression diagnostic and severity measure. Psychiatr Ann. 2002;32:509–515. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Office for National Statistics Population estimates for the UK, England and Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland. https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/populationandmigration/populationestimates/bulletins/annualmidyearpopulationestimates/mid2018

- 27.Brooks SK, Webster RK, Smith LE, et al. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of the evidence. Lancet. 2020;395:912–920. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30460-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Baker ZG, Krieger H, LeRoy AS. Fear of missing out: relationships with depression, mindfulness, and physical symptoms. Transl Issues Psychol Sci. 2016;2:275–282. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Porter LC, DeMarco LM. Beyond the dichotomy: incarceration dosage and mental health. Criminology. 2019;57:136–156. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bu F, Steptoe A, Fancourt D. Who is lonely in lockdown? Cross-cohort analyses of predictors of loneliness before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Public Health. 2020;186:31–34. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2020.06.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Guan W, Ni Z, Hu Y, et al. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032. published online Feb 28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marmot M. Health equity in England: the Marmot review 10 years on. BMJ. 2020;368:m693. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Newby JM, O'Moore K, Tang S, Christensen H, Faasse K. Acute mental health responses during the COVID-19 pandemic in Australia. PLoS One. 2020;15 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0236562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Asmundson GJ, Paluszek MM, Landry CA, Rachor GS, McKay D, Taylor S. Do pre-existing anxiety-related and mood disorders differentially impact COVID-19 stress responses and coping? J Anxiety Disord. 2020;74 doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2020.102271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xiong J, Lipsitz O, Nasri F, et al. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on mental health in the general population: a systematic review. J Affective Disord. 2020;277:55–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Phillips C. Institutional racism and ethnic inequalities: an expanded multilevel framework. J Soc Policy. 2011;40:173–192. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Harmatz MG, Well AD, Overtree CE, Kawamura KY, Rosal M, Ockene IS. Seasonal variation of depression and other moods: a longitudinal approach. J Biol Rhythms. 2000;15:344–350. doi: 10.1177/074873000129001350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Anonymous data will be made publicly available at the end of 2021.