Abstract

The failure rate of TAA is still higher than that of other joint replacement procedures. This study aimed to calculate the early failure rate and identify associated patient factors. Data from the Korean Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service database from 2009 to 2017 were collected. We evaluated patients who had TAA as a primary surgical procedure. Early failure was defined as conversion to revision TAA or arthrodesis after primary TAA within five years. Patients with early failure after primary TAA were designated as the “Failure group”. Patients without early failure and who were followed up unremarkably for at least five years after primary TAA were designated as the “No failure group”. Overall, 2157 TAA participants were included. During the study period, 197 patients developed failure within five years postoperatively, for an overall failure rate of 9.1%. Significant risk factors for early failure were history of chronic pulmonary disease, diabetes, peripheral vascular disease, hyperlipidemia, dementia, and alcohol abuse. A significant increase of odds ratio was found in patients with a history of dementia, chronic pulmonary disease, and diabetes. Surgical indications and preoperative patient counseling should consider these factors.

Subject terms: Risk factors, Outcomes research

Introduction

Total ankle arthroplasty (TAA) is growing in popularity along with ankle arthrodesis for the treatment of end-stage ankle arthritis1. An advantage of TAA includes maintaining mobility at the ankle joint and decreasing the radiographic incidence of adjacent joint degeneration, which is otherwise seen in ankle arthrodesis2. Improvements in implant design and technique have resulted in good short- and mid-term clinical outcomes3, which have recently gained importance with respect to TAA.

Despite functional benefits, results after TAA have not reached the same level as those for hip and knee arthroplasty4. Using meta-analysis, the risk of reoperation with the use of TAA was significantly higher than that with the use of ankle arthrodesis (risk ratio [RR] = 1.81; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.37–2.39)5. According to a recently published meta-analysis, pooled proportion of conversion to arthrodesis or revision at 5 and 10 years of minimum follow-up was 0.122 (95% CI: 0.084–0.173)–0.185 (95% CI: 0.131–0.256) and 0.202 (95% CI: 0.118–0.325)–0.305 (95% CI: 0.191–0.448), respectively2.

Although studies have identified some risk factors including age, sex, race, type of implant, and radiologic findings associated with the failure of TAA with small cohorts, the number of studies is relatively small compared to studies on other joint replacement techniques. Previous cohort studies also have some limitations. Different databases use different methods of data collection, and the answer to a given study question may vary according to the database used as they represent different populations6. In addition, lack of various comorbidities as study variables would limit their usefulness. To improve the outcomes of future patients, it is necessary to carefully analyze the modifiable risk factors for failure. Furthermore, the absence of a clear definition of revision7,8 or failure9 may lead to underestimation or overestimation of failure.

Almost all people in South Korea are covered by a single national health insurance program, and we were able to collect data from the insurance claims database that involved a large cohort that underwent a TAA procedure. The aim of the present study was to calculate the early failure rate and to identify patient factors associated with the early failure of TAA.

Materials and methods

Dataset

The Ethics Committee of Hallym University (HALLYM 2020-02-009) approved the use of the data from the insurance claims database. Written informed consent was waived by the Institutional Review Board (The Ethics Committee of Hallym University). All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. This is a retrospective cohort study using data from the Korean Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service (HIRA). About 97% of the entire population enrolled in the South Korean National Health Insurance (NHI) program and another 3% enrolled in the Medical Aid Program. The claims data for reimbursement of medical costs of these patients are submitted to the HIRA. Healthcare providers submit their patients’ data to the HIRA, which includes the diagnosis code according to the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th revision (ICD-10), procedure codes, prescriptions, medical costs, and other demographic data, including patient age, sex, hospital admissions, insurance type, and comorbidities. All data from the HIRA are anonymous and encrypted to protect participants’ privacy.

Study design and participants

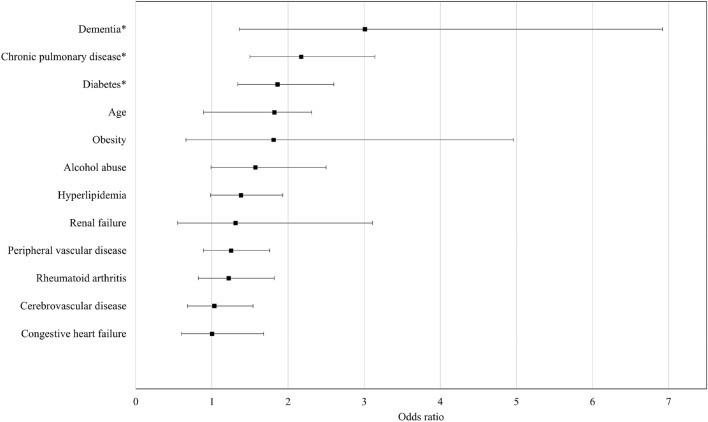

We included patients who have TAA procedure codes (Electronic Data Interchange [EDI]: N0279 or N0279) from 2007 to 2016. A flow diagram of the inclusion of patients is shown in Fig. 1. All included patients had a minimum of 1-year clinical follow-up, and patients who underwent a bilateral TAA procedure during the study period were also excluded. Early failure was defined as TAA requiring revision arthroplasty or implant removal and arthrodesis after primary TAA within five years. The duration of early failure was based on previous studies. The failure was reported to occur at an average of 16.4 months7, and the mean implant survival time to revision for any cause was reported to be between 48 and 86 months2. Patients who were followed up for at least five years without revision or implant removal and arthrodesis procedure after index primary TAA procedure were defined as the “No failure” group. Patients who underwent revision arthroplasty or implant removal and arthrodesis procedure within 5 years after index primary TAA procedure were defined as the “Failure” group. Patients were identified by procedure codes: TAA revision as EDI N3715 or N3719 or EDI N4715 or N4719. For ankle arthrodesis, patients who have both TAA implant removal code and ankle arthrodesis code were identified: TAA implant removal as EDI N3725 or N3729 and ankle arthrodesis as EDI N0733 or N0736. In this case, the date of ankle arthrodesis was followed by the primary TAA date.

Figure 1.

A schematic illustration of the participant selection process that was used in the present study. Out of a total of 2482 participants, 2,157 total ankle arthroplasty (TAA) participants were selected.

Covariates

The covariates included in the present study included age, sex, admission, duration, and comorbidities. Comorbidities of patients were identified based on a previously published protocol10,11. We included myocardial infarction (ICD-10: I21 or I22), congestive heart failure (ICD-10: I50), cerebrovascular disease (ICD-10: I60-I69), chronic pulmonary disease (ICD-10: J44), hypertension (ICD-10: I10-I15), diabetes mellitus (ICD-10: E10-E14), renal failure (ICD-10: N17–N19), rheumatoid arthritis (ICD-10: M058, M059, M068 or M069), peripheral vascular disease (ICD-10: I73), hyperlipidemia (ICD-10: E78), dementia (ICD-10: F00 through F03), obesity (ICD-10: E66), psychosis (ICD-10: F20–F29), depression (ICD-10: F33), osteoporosis (ICD-10: M80–M84) and alcohol abuse (ICD-10: F10)10,11. All the comorbidities were included as patient risk factors if they were diagnosed before the index primary TAA procedure.

Statistical analysis

All continuous variables are expressed as means and standard deviation (SD). We used Pearson’s chi-squared test to compare qualitative differences. Fisher’s exact test was performed if the number of expected cases was less than five. The significance of differences in continuous variables was explored using the independent samples t-test. We employed multivariate logistic regression to identify prognostic risk factors for early failure. The selected variable for multivariate analysis included variables with a p value < 0.2 in univariate analysis. The odds ratios (OR), 95% confidence intervals (CI), and p values of various patient demographic characteristics and comorbidities were calculated. A p value < 0.05 indicated statistical significance. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS for Windows software (ver. 16.0, IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) and SAS Enterprise software (version 6.1: SAS Institute Inc. Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Among 2482 patients who underwent TAA and who were invited for the current study, 2157 patients who underwent TAA were selected for the final analysis (Fig. 1). During the study period, 197 patients developed early failure, for an overall early failure rate of 9.1%. Among them, 165 patients (84%) required revision arthroplasty and 32 patients (16%) required implant removal and arthrodesis.

The results of the univariate analysis for the comparison of the two groups are listed in Table 1. History of chronic pulmonary disease (p < 0.001), diabetes (p < 0.001), peripheral vascular disease (p = 0.005), hyperlipidemia (p < 0.001), dementia (p < 0.001), and alcohol abuse (p = 0.002) showed significant differences between the two groups.

Table 1.

Comparison between two groups.

| No failure group | Failure group | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 1960 | 197 | |

| Age (mean, standard deviation) | 69.3 (9.72) | 66.7 (10.25) | 0.07 |

| Sex (% of female) | 959 (48.9%) | 93 (47.2%) | 0.65 |

| Admission duration (day) | 17.3 ± 11.27 | 16.4 ± 10.3 | 0.30 |

| Comorbidities | |||

| Myocardiac infarction | 156 (8.0%) | 9 (4.6%) | 0.09 |

| Congestive heart failure | 144 (7.4%) | 21 (10.7%) | 0.09 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 297 (15.2%) | 40 (20.3%) | 0.06 |

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 232 (11.8%) | 45 (22.8%) | < 0.001 |

| Hypertension | 1053 (53.7%) | 112 (56.9%) | 0.40 |

| Diabetes | 583 (29.7%) | 93 (47.2%) | < 0.001 |

| Renal failure | 37 (1.9%) | 7 (3.6%) | 0.11 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 283 (14.4%) | 37 (18.8%) | 0.10 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 498 (25.4%) | 68 (34.5%) | 0.005 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 806 (41.1%) | 112 (56.9%) | < 0.001 |

| Dementia | 27 (1.4%) | 9 (4.6%) | < 0.001 |

| Obesity | 25 (1.3%) | 5 (2.5%) | 0.15 |

| Psychosis | 87 (4.4%) | 11 (5.6%) | 0.46 |

| Depression | 166 (8.5%) | 20 (10.2%) | 0.42 |

| Osteoporosis | 861 (43.9%) | 91 (46.2%) | 0.54 |

| Alcohol abuse | 151 (7.7%) | 28 (14.21%) | 0.002 |

*Chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test. Significance at p < 0.05.

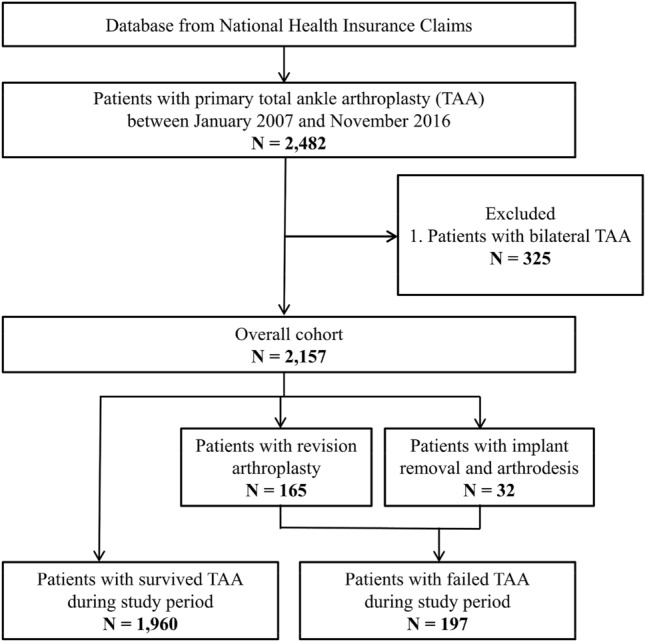

Using multivariate logistic regression analysis, dementia showed the highest significant OR (3.01, 95% CI 1.36–2.60, p = 0.006) for early failure of primary TAA (Table 2). Additionally, significantly high OR were seen in patients with a history of chronic pulmonary disease (OR 2.17, 95% CI 1.50–3.14) and diabetes for early failure of primary TAA (OR 1.86, 95% CI 1.34–2.60) (Fig. 2).

Table 2.

Results of multiple logistic regression analysis.

| Odds ratio | 95% Confidence interval | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dementia | 3.01 | 1.36 to 6.92 | 0.006 |

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 2.17 | 1.50 to 3.14 | < 0.001 |

| Diabetes | 1.86 | 1.34 to 2.60 | < 0.001 |

| Age | 1.82 | 0.89 to 2.31 | 0.125 |

| Renal failure | 1.31 | 0.55 to 3.11 | 0.542 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 1.22 | 0.82 to 1.82 | 0.324 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 1.25 | 0.89 to 1.76 | 0.203 |

| Obesity | 1.81 | 0.66 to 4.96 | 0.252 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 1.38 | 0.98 to 1.93 | 0.065 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 1.03 | 0.68 to 1.54 | 0.898 |

| Congestive heart failure | 1.00 | 0.60 to 1.68 | 0.996 |

| Alcohol abuse | 1.57 | 0.99 to 2.50 | 0.054 |

Bold values indicate statistically significant findings.

*Chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test.

Significance at p < 0.05.

Figure 2.

Odds ratio by multiple logistic regression analysis. The asterisk (*) indicates significant high OR.

Discussion

The principal finding from this nationwide cohort study with 2,157 patients who underwent TAA was that the risk of early failure seems to be higher for patients with the following comorbidities: chronic pulmonary disease (p < 0.001), diabetes (p < 0.001), peripheral vascular disease (p = 0.005), hyperlipidemia (p < 0.001), dementia (p < 0.001), and alcohol abuse (p = 0.002). Furthermore, dementia, chronic pulmonary disease, and diabetes showed increased OR of 1.86–3.01 in multivariate logistic regression analysis.

To our knowledge, this study is the largest cohort study for the evaluation of the early failure risk of primary TAA. Because it is mandatory for all Koreans to enroll in the National Health Insurance Service, this cohort data contains information on almost all Korean people who underwent a TAA procedure, and exact population statistics can be determined using this database.

In our study with 2157 patients, the early failure rate after primary TAA was 9.1%. The reported survival rate is higher than 78% of literature reviews12 and similar to 81–92.9% of recent studies4,7,13,14. The difference between the early failure rate and overall survival rate may have influenced the inconsistent results. Poorer results from earlier generations of prosthesis will have a negative effect on the overall survival and revision rates13. Among the registry reports, the 5-year survival rate (total cases, year of analysis) was 78% in the Swedish registry (1296 TAA, 1993–2005), 84.5–90.5% in the Australian registry (2272 TAA, 2008–2018), 90.8% in the New Zealand registry (1619 TAA, 2000–2018), and 93.14% in the National Joint registry for United Kingdom (5587 TAA, 2010–2018). The variations in the registry designs, the study populations, and the failure of accurate recording could explain the conflicting results of prior studies13.

Patient risk factors for early revision were already studied in total hip arthroplasty (THA) and total knee arthroplasty (TKA)15 and can be extrapolated. Diagnoses of diabetes, chronic pulmonary disease, dementia, Parkinson’s disease, lung circulation disorders, neurological diseases, alcohol abuse, drug abuse, depression, obesity, and fluid/electrolyte disorders significantly increased the risk for early revision of THA16,17. In another study, the revision rates were higher among patients with hypertension and those with paraparesis/hemiparesis for THA and among patients with metastatic disease for TKA18. About THA dislocation, a history of spinal fusion, Parkinson's disease, dementia, depression, and chronic lung disease were significantly related19.

Previous literature described that with TAA, higher comorbidity was not associated with readmission20, failure14, or revision21. However, the adverse impact of comorbidities on TAA complication has been previously documented by several authors22,23. Previous studies measured comorbidity with Deyo-Charlson index, without differentiating each comorbidity7,14,21. In addition, there are few large series in which all the comorbidities have been assessed concomitantly20,24.

Although statistically influential factors were observed, the evidence regarding dementia and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) could not be found in literature concerning TAA; therefore, studies on TKA and THA were referred to instead. Previously, dementia was not a risk factor for periprosthetic joint infection following TKA25 or THA26. However, patients with Alzheimer’s disease and dementia were a risk factor for revision or dislocation after THA19,27–29. In a systemic review article, decreased cognitive function scores were associated with a functional decline after TKA30. Dementia is an independent risk factor for experiencing a serious injury related to a fall31 and a risk factor for hip fracture even at the early stage32. This characteristic in dementia patients may also influence the outcome of TAA.

Multiple studies have studied the impact of COPD on outcomes in lower limb arthroplasty. Patients with COPD were not at an increased risk of developing wound complications after lower limb arthroplasty33. In other studies, COPD was a predictor of surgical site infection after TKA34 and THA35. In addition, COPD was a risk factor for revision of TKA within 12 months36 and revision of TKA in 10 years37. Patients with COPD frequently have many comorbidities, and other comorbidities may have influenced the outcome34,35.

Diabetes is known to be a relative contraindication of TAA38. No statistical difference in secondary operations, revisions, or failure rates between the diabetes and control groups were observed in a study of TAA patients38. However, diabetes was a risk factor for infected TAA39 or failure of TAA40, and the chance of implant survival was higher and rate of early onset osteolysis was lower in the non-diabetic group41.

The effect of age on the surgical result of primary TAA has been studied with various results. There are inconsistencies among studies on the effect of age on the survival of TAA. Several studies with small sample sizes reported no significant association between age and revision40,42. In contrast, the survival rate of patients who underwent TAA was lower in younger patients14,43. This may be explained by the fact that younger patients have higher demands and activity levels than older patients43. Interestingly, older age groups had a higher OR of length of hospital stay but a lower OR of in-hospital infection in a cohort study on TAA21. As recent trends demonstrate an increase in TAA, concerns about implant survivorship persist, as long-term follow-up is needed and options for revision remain limited44.

Other comorbidities were not found to correlate with an increased risk of early failure of TAA in this study. Meanwhile, patients with rheumatoid arthritis showed a significantly increased risk of TAA failure7. The incidence of revision TAA was significantly higher in obese patients than in nonobese patients24. The nonobese and obese cohorts were significantly different in medical comorbidities including diabetes, obstructive sleep apnea, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, congestive heart failure, coronary artery disease, chronic kidney disease, COPD, and chronic liver disease. Increased long-term risk of TAA failure among obese patients has been reported45. Recently, the clinical outcomes after TAA were poorer in patients with depressive symptoms46. Geographic variability and heterogeneity in THE definition of comorbidities may be key factors regarding differences in reported data.

There were several strengths in the present study. This study was based on an extremely large national population, while many previous studies included only a small number of patients. Previous studies were less clear about the inclusion criteria for study patients and did not analyze potential confounders such as age, sex, and comorbidities15. Because the NHI data include all national citizens without exception, there were no missing participants. Furthermore, strict inclusion criteria to define failure of TAA were used to minimize variation. Lastly, registry data include a wide range of data from surgeons, and that gives the picture of the real-life situation of foot and ankle surgeons instead of specialized surgeons or units.

Our study also had some limitations. First, it includes the inherent bias of a retrospective analysis as well as inaccuracies in coding. Scant evidence is present regarding this, thus further research is needed. Second, the current database did not include the choice of implant and the inclusion of different implants. This may influence the result as reported by Hintegra, which showed lower implant failure (adjusted OR 0.31, 95% CI 0.15–0.66; p = 0.002) with the Mobility implant47. However, most of the instruments used in Korea are Hintegra or Salto, and the implant may not have had a significant effect on the outcome. Third, variables including alignment of the joint and postoperative patient-reported outcome measures could not be accounted for in a retrospective cohort study with national insurance claims data. Although these limitations are important, we believe that the large sample size of the database can provide valuable information. It is mandatory that future studies include re-analysis of TAA to evaluate long-term survival rates in patients with advanced prosthetic designs14. Finally, as the general code did not further specify where TAA was performed within the ankle, patients who underwent TAA on both sides were excluded from this study. In addition, there can be patients with poor outcomes who chose not to undergo revision48, although that number is expected to be small. Such variables for each patient were not studied and should be addressed in future studies.

Conclusion

According to previously published research, the present study supports the importance of comorbidities in predicting early revision of TAA. In conclusion, this study demonstrated that patients with dementia, chronic pulmonary disease, and diabetes were more likely to show early failure of TAA. We believe that understanding comorbidities may provide valuable clinical insight in predicting the potential risk for TAA failure.

Author contributions

J.W.L. developed the study concept and design and extracted the data. W.Y.I., S.Y.S. and J.Y.C. performed the statistical analysis and revised the drafted manuscript. S.J.K. had full access to all data in the study and takes responsibility for data integrity and data analysis accuracy. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Data availability

The data of this study are available from NHIS, but restrictions apply to availability. These data were used under license for the current study only and are not publicly available.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Morash J, Walton DM, Glazebrook M. Ankle arthrodesis versus total ankle arthroplasty. Foot Ankle Clin. 2017;22:251–266. doi: 10.1016/j.fcl.2017.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Onggo JR, et al. Outcome after total ankle arthroplasty with a minimum of five years follow-up: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Foot Ankle Surg. 2019 doi: 10.1016/j.fas.2019.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Saltzman CL, Kadoko RG, Suh JS. Treatment of isolated ankle osteoarthritis with arthrodesis or the total ankle replacement: a comparison of early outcomes. Clin. Orthop. Surg. 2010;2:1–7. doi: 10.4055/cios.2010.2.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Labek G, Todorov S, Iovanescu L, Stoica CI, Bohler N. Outcome after total ankle arthroplasty-results and findings from worldwide arthroplasty registers. Int. Orthop. 2013;37:1677–1682. doi: 10.1007/s00264-013-1981-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim HJ, et al. Total ankle arthroplasty versus ankle arthrodesis for the treatment of end-stage ankle arthritis: a meta-analysis of comparative studies. Int. Orthop. 2017;41:101–109. doi: 10.1007/s00264-016-3303-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bekkers S, Bot AG, Makarawung D, Neuhaus V, Ring D. The National Hospital discharge survey and nationwide inpatient sample: the databases used affect results in THA research. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2014;472:3441–3449. doi: 10.1007/s11999-014-3836-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.LaMothe J, Seaworth CM, Do HT, Kunas GC, Ellis SJ. Analysis of total ankle arthroplasty survival in the United States using multiple state databases. Foot Ankle Spec. 2016;9:336–341. doi: 10.1177/1938640016640891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Henricson A, Carlsson A, Rydholm U. What is a revision of total ankle replacement? Foot Ankle Surg. 2011;17:99–102. doi: 10.1016/j.fas.2010.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mercer J, Penner M, Wing K, Younger AS. Inconsistency in the reporting of adverse events in total ankle arthroplasty: a systematic review of the literature. Foot Ankle Int. 2016;37:127–136. doi: 10.1177/1071100715609719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Quan H, et al. Coding algorithms for defining comorbidities in ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 administrative data. Med. Care. 2005;43:1130–1139. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000182534.19832.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jeschke E, et al. Five-year survival of 20,946 unicondylar knee replacements and patient risk factors for failure: an analysis of German insurance data. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Am. 2016;98:1691–1698. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.15.01060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Labek G, Klaus H, Schlichtherle R, Williams A, Agreiter M. Revision rates after total ankle arthroplasty in sample-based clinical studies and national registries. Foot Ankle Int. 2011;32:740–745. doi: 10.3113/fai.2011.0740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jeyaseelan L, et al. Outcomes following total ankle arthroplasty: a review of the registry data and current literature. Orthop. Clin. North Am. 2019;50:539–548. doi: 10.1016/j.ocl.2019.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Seaworth CM, et al. Epidemiology of total ankle arthroplasty: trends in New York state. Orthopedics. 2016;39:170–176. doi: 10.3928/01477447-20160427-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Podmore B, Hutchings A, van der Meulen J, Aggarwal A, Konan S. Impact of comorbid conditions on outcomes of hip and knee replacement surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2018;8:e021784. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-021784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dy CJ, et al. Risk factors for early revision after total hip arthroplasty. Arthritis. Care Res. (Hoboken) 2014;66:907–915. doi: 10.1002/acr.22240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bottle A, Parikh S, Aylin P, Loeffler M. Risk factors for early revision after total hip and knee arthroplasty: national observational study from a surgeon and population perspective. PLoS ONE. 2019;14:e0214855. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0214855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rhee C, Lethbridge L, Richardson G, Dunbar M. Risk factors for infection, revision, death, blood transfusion and longer hospital stay 3 months and 1 year after primary total hip or knee arthroplasty. Can. J. Surg. 2018;61:165–176. doi: 10.1503/cjs.007117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gausden EB, Parhar HS, Popper JE, Sculco PK, Rush BNM. Risk Factors for early dislocation following primary elective total hip arthroplasty. J. Arthroplasty. 2018;33:1567–1571.e1562. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2017.12.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cunningham D, et al. Patient risk factors do not impact 90-day readmission and emergency department visitation after total ankle arthroplasty: implications for the comprehensive care for joint replacement (CJR) bundled payment plan. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Am. 2018;100:1289–1297. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.17.01149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Singh JA, Cleveland JD. Age, race, comorbidity, and insurance payer type are associated with outcomes after total ankle arthroplasty. Clin. Rheumatol. 2020;39:881–890. doi: 10.1007/s10067-019-04826-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhou H, Yakavonis M, Shaw JJ, Patel A, Li X. In-patient trends and complications after total ankle arthroplasty in the United States. Orthopedics. 2016;39:e74–79. doi: 10.3928/01477447-20151228-05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Heida KA, et al. Short-term perioperative complications and mortality after total ankle arthroplasty in the United States. Foot Ankle Spec. 2018;11:123–132. doi: 10.1177/1938640017709912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Werner BC, et al. Obesity is associated with increased complications after operative management of end-stage ankle arthritis. Foot Ankle Int. 2015;36:863–870. doi: 10.1177/1071100715576569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bozic KJ, Lau E, Kurtz S, Ong K, Berry DJ. Patient-related risk factors for postoperative mortality and periprosthetic joint infection in medicare patients undergoing TKA. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2012;470:130–137. doi: 10.1007/s11999-011-2043-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bozic KJ, et al. Patient-related risk factors for periprosthetic joint infection and postoperative mortality following total hip arthroplasty in Medicare patients. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Am. 2012;94:794–800. doi: 10.2106/jbjs.K.00072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jamsen E, Peltola M, Puolakka T, Eskelinen A, Lehto MU. Surgical outcomes of hip and knee arthroplasties for primary osteoarthritis in patients with Alzheimer's disease: a nationwide registry-based case-controlled study. Bone Jt. J. 2015;97-b:654–661. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.97b5.34382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lenguerrand E, et al. Risk factors associated with revision for prosthetic joint infection after hip replacement: a prospective observational cohort study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2018;18:1004–1014. doi: 10.1016/s1473-3099(18)30345-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hernandez NM, Cunningham DJ, Jiranek WA, Bolognesi MP, Seyler TM. Total hip arthroplasty in patients with dementia. J. Arthroplasty. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2020.01.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Puustinen J, et al. The use of MoCA and other cognitive tests in evaluation of cognitive impairment in elderly patients undergoing arthroplasty. Geriatr. Orthop. Surg. Rehabil. 2016;7:183–187. doi: 10.1177/2151458516669203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Allan LM, Ballard CG, Rowan EN, Kenny RA. Incidence and prediction of falls in dementia: a prospective study in older people. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e5521. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jeon JH, et al. Dementia is associated with an increased risk of hip fractures: a nationwide analysis in Korea. J. Clin. Neurol. 2019;15:243–249. doi: 10.3988/jcn.2019.15.2.243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Klasan A, et al. COPD as a risk factor of the complications in lower limb arthroplasty: a patient-matched study. Int. J. Chron. Obstruct. Pulmon. Dis. 2018;13:2495–2499. doi: 10.2147/copd.S161577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yakubek GA, et al. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease is associated with short-term complications following total knee arthroplasty. J. Arthroplasty. 2018;33:2623–2626. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2018.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yakubek GA, et al. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease is associated with short-term complications following total hip arthroplasty. J. Arthroplasty. 2018;33:1926–1929. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2017.12.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bozic KJ, et al. Risk factors for early revision after primary TKA in Medicare patients. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2014;472:232–237. doi: 10.1007/s11999-013-3045-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dy CJ, et al. Risk factors for revision within 10 years of total knee arthroplasty. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2014;472:1198–1207. doi: 10.1007/s11999-013-3416-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gross CE, et al. Impact of diabetes on outcome of total ankle replacement. Foot Ankle Int. 2015;36:1144–1149. doi: 10.1177/1071100715585575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Patton D, Kiewiet N, Brage M. Infected total ankle arthroplasty: risk factors and treatment options. Foot Ankle Int. 2015;36:626–634. doi: 10.1177/1071100714568869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Escudero MI, et al. Total ankle arthroplasty survival and risk factors for failure. Foot Ankle Int. 2019;40:997–1006. doi: 10.1177/1071100719849084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Choi WJ, Lee JS, Lee M, Park JH, Lee JW. The impact of diabetes on the short- to mid-term outcome of total ankle replacement. Bone Jt. J. 2014;96:1674–1680. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.96b12.34364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lee GW, Seon JK, Kim NS, Lee KB. Comparison of intermediate-term outcomes of total ankle arthroplasty in patients younger and older than 55 years. Foot Ankle Int. 2019;40:762–768. doi: 10.1177/1071100719840816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Barg A, Zwicky L, Knupp M, Henninger HB, Hintermann B. HINTEGRA total ankle replacement: survivorship analysis in 684 patients. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Am. 2013;95:1175–1183. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.L.01234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Demetracopoulos CA, et al. Effect of age on outcomes in total ankle arthroplasty. Foot Ankle Int. 2015;36:871–880. doi: 10.1177/1071100715579717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schipper ON, Denduluri SK, Zhou Y, Haddad SL. Effect of obesity on total ankle arthroplasty outcomes. Foot Ankle Int. 2016;37:1–7. doi: 10.1177/1071100715604392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kim TY, Lee HW, Jeong BO. Influence of depressive symptoms on the clinical outcomes of total ankle arthroplasty. J. Foot Ankle Surg. 2020;59:59–63. doi: 10.1053/j.jfas.2019.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lefrancois T, et al. A prospective study of four total ankle arthroplasty implants by non-designer investigators. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Am. 2017;99:342–348. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.16.00097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cody EA, et al. Risk factors for failure of total ankle arthroplasty with a minimum five years of follow-up. Foot Ankle Int. 2019;40:249–258. doi: 10.1177/1071100718806474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data of this study are available from NHIS, but restrictions apply to availability. These data were used under license for the current study only and are not publicly available.