Abstract

Metformin-treated diabetics (MTD) showed a decrease in cobalamin, a rise in homocysteine, and methylmalonic acid, leading to accentuated diabetic peripheral neuropathy (DPN). This study aimed to determine whether or not metformin is a risk factor for DPN. We compared MTD to non-metformin-treated diabetics (NMTD) clinically using the Toronto Clinical Scoring System (TCSS), laboratory (methylmalonic acid, cobalamin, and homocysteine), and electrophysiological studies. Median homocysteine and methylmalonic acid levels in MTD vs. NMTD were 15.3 vs. 9.6 µmol/l; P < 0.001 and 0.25 vs. 0.13 µmol/l; P = 0.02, respectively with high statistical significance in MTD. There was a significantly lower plasma level of cobalamin in MTD than NMTD. Spearman’s correlation showed a significant negative correlation between cobalamin and increased dose of metformin and a significant positive correlation between TCSS and increased dose of metformin. Logistic regression analysis showed that MTD had significantly longer metformin use duration, higher metformin dose > 2 g, higher TCSS, lower plasma cobalamin, and significant higher homocysteine. Diabetics treated with metformin for prolonged duration and higher doses were associated with lower cobalamin and more severe DPN.

Subject terms: Neuronal physiology, Peripheral neuropathies, Diabetes

Introduction

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is a chronic metabolic disease associated with hyperglycemia owing to impaired insulin secretion, insulin activity, or both1. High blood glucose levels can cause damage to all parts of the body including the cardiovascular system, eyes, kidneys, and nervous system2. American Diabetes Association 2019 recommended Metformin for the treatment of type 2 DM and should be continued as long as it is tolerated3. Nareddy et al. reported that metformin can cause cobalamin deficiency4. Cobalamin is associated with various metabolic functions, including red cell generation and intact nervous system, and so its dysfunction can cause anemia and neurological impairment5,6. Homocysteine is a sulfur-containing amino acid formed during the metabolism of methionine7. It is associated with cardiac and vascular illness produced in different ways like the increase of blood coagulation, oxidative stress, endothelial impairment, and cardiomyocyte impairment8–10. Bansal et al. concluded that atherosclerosis of blood vessels is the cause of most of DM related complications. Serum homocysteine can be utilized independently as an indicator of cardiovascular risk events in type 2 diabetes11. Subclinical cobalamin dysfunction is sometimes presented with ordinary blood levels12. Metformin is known to diminish serum cobalamin level with raised methylmalonic acid and homocysteine levels in patients with type 2 DM13–16. Diabetic peripheral neuropathy (DPN), is the most widely recognized complication of DM17. Liu et al. stated that the duration of diabetes, age, hemoglobin A1c, and diabetic retinopathy are associated with significantly increased risks of DPN among diabetic patients18. It affects approximately half of patients with diabetes19. The pathogenesis of DPN includes oxidative and inflammatory stress besides metabolic dysfunction causing neuronal injury and damage20,21. Electrophysiological nerve conduction studies (NCS) can confirm that the diagnosis of DPN and the sural nerve is the most applicable to correlating with the severity of DPN22. However, NCS does not generally distinguish early changes of neuronal damage and some DPN patients give negative results in the clinical assessment23. Our study intends to distinguish the serum level of cobalamin, methylmalonic acid and homocysteine changes in Metformin-treated diabetics (MTD) and to evaluate the connection between the severity of DPN and the long-term utilization of metformin.

Methods

Participants and inclusion criteria

150 adult patients with Type 2 DM (T2DM) were included according to Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes Guidelines24. We prospectively identified patients diagnosed with T2DM who were treated with metformin for more than 6 months. Also, we select non-metformin treated age and sex matched with metformin treated group with the same number of cases. The study design was a case–control, prospective, analytical, observational study. Cases were T2DM patients on metformin (75 participants). Controls were T2DM patients not taking metformin (75 participants).

The present prospective study was conducted during the period from the first of May 2017 to the end of September 2018 in the neurology outpatient clinic, Mansoura University Hospital, Egypt. The included patients were type two diabetics on oral hypoglycemic therapy with clinical proof for DPN. Patients were classified into 2 groups; Metformin treated (group I): included 75 patients administered metformin for the previous 6 months or more and non-metformin treated (group II): included 75 patients who weren’t administered metformin for the previous 6 months (but administered other oral hypoglycemic drugs). The duration of DPN was determined by the history of onset of symptoms or the previous electrophysiological studies done.

Sample size determination

The formula for estimation of sample size is:

where n is the needed sample size, Z is the critical value at 95% confidence level (1.96), p is the prevalence of vitamin B12 deficiency in cases with type 2 DM on metformin (9.7%) obtained from the study of de Groot et al.25. e is the error margin that the researcher was willing to accept, and in this condition, was equal to 0.05. Note that (1–p) = q, which was the proportion of the sample population not covered by the study.

Substituting the values, we get n = 1.96 × 1.96 × 0.097 (1–0.097)/0.05 × 0.05 = 135 (with 10% attrition) 135 + 13.5 = 148.5. This was rounded up to 150 patients.

Exclusion criteria

The patients excluded from this study possessed the following characteristics: type 1 diabetes mellitus, impaired glucose tolerance, peripheral neuropathy because of different causes other than diabetes or cobalamin insufficiency and patient cease treatment by metformin or administrated metformin for less than 6 months.

Clinical assessment

Complete history taking for symptoms of DPN, family history of DPN, medical history, duration of DM, and current medications for DM or other systemic diseases was taken. Also, complete general and neurological examinations were done. The clinical assessment of the severity of DPN was done by the Toronto Clinical Scoring System (TCSS) which comprises of three sections: symptom scores, reflex scores, and sensory test scores. The greatest score is 19 points: 0–5 if there is no diabetic peripheral neuropathy, 6–8 if there is mild diabetic peripheral neuropathy, 9–11 if there is moderate diabetic peripheral neuropathy, 12–19 if there is severe diabetic peripheral neuropathy24,26.

Electrophysiological studies and laboratory investigations

Regarding the electrophysiological studies, a nerve conduction study was carried out for all patients by utilizing Xilec-Xcalibur from Natus neurology, USA, 2010. The selected nerves, according to clinical symptoms and findings were examined for motor and sensory conduction studies, the distal latency, the amplitude of action potential, motor and sensory conduction velocities were measured25,27. The laboratory investigations include complete blood count, electrolytes, renal and hepatic functions, thyroid-stimulating hormone, rheumatoid factor, serum folate, Hemoglobin A1c, and serum cobalamin level according to the classic method of radioimmunoassay. High-performance liquid chromatography used to measure the homocysteine levels and mass spectrometry used to measure methylmalonic acid levels for all patients.

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the Mansoura Faculty of Medicine (proposal code R.19.10.640) and all participants gave informed consent to take part in the study. The research adhered to the tenets of the declaration of Helsinki (1964).

Statistical analysis

The Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) programming, version 21.0 was utilized for information registration, approval, and analysis. Frequency, tables, and diagrams were produced for the categorical variables. Tests of significance were created for various variables. The Chi-square test was utilized to test categorical variables, and independent t-tests were utilized to test the importance of the results of the two groups. The Mann–Whitney U test was utilized to contrast and to investigate the means of the independent variables. The correlation coefficient and Chi-squared tests were utilized to gauge the relation between two quantitative and qualitative variables. The degree of statistical significance was characterized by an estimation of P-value < 0.05. Spearman’s correlation coefficient was done to analyze the relationship between continuous variables such as metformin dose and vitamin B12 levels and also between metformin dose and TCSS scores. Logistic regression analysis was carried out to identify independent risk factors for diabetic PN in metformin-treated patients.

Results

Patients demographic and clinical characteristics

This study was carried out on 150 patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Group I included 75 patients administered metformin for the previous 6 months or more. Group II included 75 patients who weren’t administered metformin for the previous 6 months (but administered other oral hypoglycemic drugs). The two groups were similar in age, sex. Also, there was no important difference between both groups regarding differences in the disease severity, the duration of diabetes, and duration of diabetic PN (P = 0.9 and 0.82 respectively (Table 1). MTD had a significantly higher moderate to severe DPN and higher total scores of TCSS (10 ± 7.5 vs. 5 ± 9.5, P < 0.001) indicated that metformin users had a more severe DPN (Table 1).

Table 1.

Patients’ demographic and clinical characteristics, divided according to metformin use (N = 150).

| Variables | MT N (75) | NMT N (75) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 56.9 ± 12.3 | 54.3 ± 10.9 | 0.91 |

| Male sex (%) | 41 (54.7) | 39 (52) | 0.7434 |

| Duration of DM (years) | 5.9 ± 4.3 | 3.9 ± 4.8 | 0.995 |

| SBP (mmHg) | 129.9 ± 18.72) | 127.82 ± 19.2 | 0.59 |

| DBP (mmHg) | 76.81 ± 8.7 | 75.0 ± 10.1 | 0.74 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 31.9 ± 8.43 | 32.73 ± 7.92 | 0.88 |

| Duration of DPN (years) | 3.2 ± 2.1 | 2.9 ± 1.8 | 0.82 |

| Diagnosed neuropathy N (%) | 38 (50.7%) | 20 (26.7%) | 0.002 |

| TCSS | |||

| Total TCSS score | 10 ± 7.5 | 5 ± 9.5 | < 0.001 |

| No DPN | 37 (49.3%) | 55 (73.3%) | < 0.001 |

| Mild | 12 (16%) | 10 (13.3%) | |

| Moderate | 19 (25.3) | 7 (9.4%) | |

| Severe | 7 (9.4%) | 3 (4%) | |

| Duration of metformin intake | |||

| < 1 year | 15 (20) % | N/A | N/A |

| 1–4 years | 29 (38.7%) | N/A | |

| > 4 years | 31 (41.3%) | N/A | |

| Metformin dose | |||

| < 1000 (mg) | 15 (20%) | N/A | N/A |

| 1000–2000 (mg) | 50 (66.7%) | N/A | |

| > 2000 (mg) | 10 (13.3%) | N/A | |

MT: metformin-treated, NMT: non-metformin-treated, SBP: systolic blood pressure, DBP: diastolic blood pressure, BMI: Body Mass Index, TCSS: Toronto clinical scoring system, DPN: diabetic peripheral neuropathy, N/A: not applicable.

Laboratory findings for metformin-treated and non-metformin-treated groups

Table 2 showed a lower median serum cobalamin in the metformin-treated diabetics with high statistical significance (222 vs. 471 pmol/l; P < 0.001). There were also significant differences between the two groups in median serum homocysteine and methylmalonic acid levels, and MTD showed higher levels with P < 0.05. HbA1c was higher in metformin-treated diabetics without statistical significance (P = 0.09).

Table 2.

Comparison of laboratory features for metformin-treated and non-metformin-treated groups.

| Laboratory features | MT N (75) | NMT N (75) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Serum Cbl (pmol/L) median (range) | 222 (337) | 471 (799) | < 0.001 |

| Cbl deficiency (< 210 pmol/L) N (%) | 25 (33%) | 3 (4%) | < 0.001 |

| Fasting serum Hcy (µmol/L) median (range) | 15.3 (19.6) | 9.6 (16.3) | < 0.05 |

| Fasting serum MMA (µmol/L) median (range) | 0.25 (0.61) | 0.13 (0.21) | < 0.05 |

| HbA1c | 7.6 ± 1.1 | 6.7 ± 1.0 | 0.09 |

MT: metformin-treated, NMT: non-metformin-treated, Cbl: cobalamin, Hcy: homocysteine, MMA: methylmalonic acid, N: number, HbA1c: hemoglobin A1c.

Electrophysiological study of both groups

Median conduction velocity for superficial peroneal and sural nerves in MTD showed significant slower conductivity with P < 0.05. Additionally, median sensory nerve action potentials (SNAP) studies for sural and superficial peroneal nerves in the MTD showed a significantly lower level with P < 0.05 (Table 3).

Table 3.

Comparison of nerve conduction study features for metformin-treated and non-metformin-treated groups.

| Electrophysiological findings | MT N (75) | NMT N (75) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Superficial peroneal nerve SNAP (amplitude µv) | 3.2 ± 5.7 | 5.9 ± 6.9 | < 0.05 |

| Superficial peroneal nerve sensory conduction velocity (m/s) | 31.1 ± 7.1 | 35.0 ± 8.5 | < 0.05 |

| Sural nerve SNAP (amplitude µv) | 3.3 ± 6.1 | 6.1 ± 7.5 | < 0.05 |

| Sural nerve sensory conduction velocity (m/s) | 32.9 ± 9.1 | 36.1 ± 7.7 | < 0.05 |

SNAP: sensory nerve action potential, MT: metformin-treated, NMT: non-metformin-treated, N: number.

Correlation of metformin dose to vitamin B12 and Cbl plasma levels

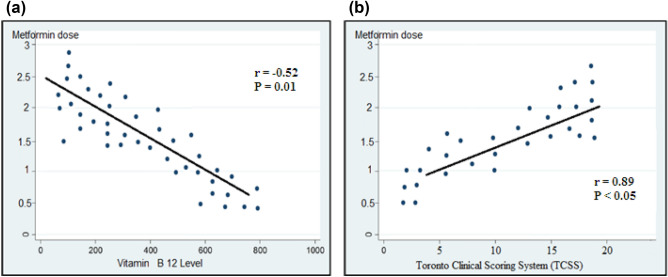

Spearman’s correlation coefficient was used to examine the bivariate relationship between the two continuous variables of metformin dose and vitamin B12 levels and metformin dose and TCSS. Figure 1A showed a significant negative correlation between cobalamin plasma levels and higher doses of metformin (r = − 0.522 and P = 0.01). Figure 1B showed a significant positive correlation between TCSS and increased dose of metformin (r = 0.891 and P < 0.05).

Figure 1.

(A) Correlation of vitamin B12 and metformin dose. (B) Correlation of Toronto Clinical Scoring System and metformin dose.

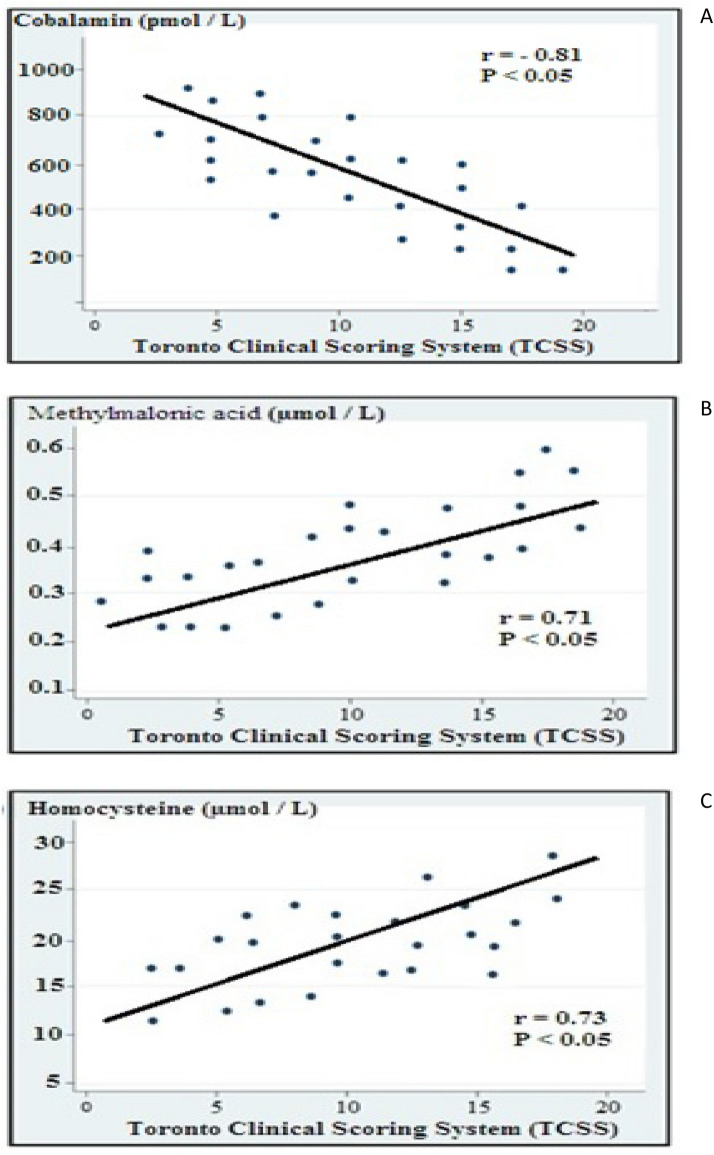

Correlation of the severity of DPN with cobalamin, homocysteine, and methylmalonic acid (Fig. 2)

Figure 2.

Correlation of the severity of DPN with (A) cobalamine, (B) methymalonic acid, and (C) homocysteine.

There was a significant inverse relationship with the severity of DPN and cobalamine level (r = − 0.81 and P < 0.05), while the severity of DPN was directly related to higher levels of both methylmalonic acid, and homocysteine (r = 0.71 and P < 0.05; and r = 0.73 and P < 0.05 respectively).

Independent predictors of diabetic peripheral neuropathy in metformin-treated diabetics

Finally, multivariate logistic regression analysis of independent predictors of DPN in MTD showed that longer duration of DM and treatment by metformin were significantly associated with more incidence of DPN (OR = 1.2% CI 1.1–1.3 and P < 0.05 and OR = 1.8 CI 1.1–2.5, P < 0.05 respectively). Also, larger doses and longer duration of therapy by metformin were independent predictors of diabetic peripheral neuropathy (OR = 6.43% CI 1.39–13.94 and P < 0.01 and OR = 5.89 CI 1.34–15.92, P = 0.01 respectively). Moreover the Logistic regression analysis showed that metformin-treated patients had significantly lower plasma cobalamin (OR = 3.67% CI 0.91 to 8.96, P < 0.05) and significantly higher homocysteine (OR = 7. 45% CI 2.16 to 15.77, P < (Table 4).

Table 4.

Multivariate logistic regression analysis of independent predictors of diabetic peripheral neuropathy in metformin-treated diabetics.

| Odds ratio (95% CI) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|

| Duration of diabetes | 1.2 (1.1–1.3) | < 0.05 |

| Drug treatment—metformin | 1.8 (1.1–2.5) | < 0.05 |

| Metformin duration (years) | ||

| < 1 year | 1.23 (0.82–2.58) | 0.09 |

| 1–4 years | 2.47 (0.87–9.64) | < 0.05 |

| > 4 years | 5.98 (1.34–15.92) | 0.01 |

| Daily dose of metformin (g) | ||

| < 1000 | 1.69 (0.71–2.11) | 0.08 |

| 1000–2000 | 3.91 (0.95–9.61) | < 0.05 |

| > 2000 | 6.43 (1.93–13.94) | < 0.01 |

| Homocysteine (μmol/L) | 7. 45 (2.16–15.77) | < 0.01 |

| Serum Cbl (μmol/L) | 3.67 (0.91–8.96) | < 0.05 |

| Toronto clinical scoring system | ||

| No DPN | Ref | |

| Mild DPN | 1.23 (0.82–2.58) | 0.09 |

| Moderate DPN | 3.73 (0.86–7.98) | 0.05 |

| Severe DPN | 6.21 (1.85–11.79) | < 0.05 |

DPN: diabetic peripheral neuropathy, Cbl: cobalamin, DPN: diabetic peripheral neuropathy.

Discussion

Diabetic patients have different degrees of nervous system damage ranging from mild to severe forms, the most widely recognized being peripheral neuropathy which affects 60% to 70% of cases28. The aim of this study was to assess whether metformin is a risk factor for the development of DPN by evaluating the impact of metformin on the serum level of cobalamin and homocysteine in type 2 DM. Most of the past clinical studies demonstrated that metformin has some impact on plasma cobalamin and homocysteine and there are some case reports indicating deterioration of neuropathy with metformin29–32. Some recent researches have investigated the relation of metformin with the level of cobalamin and neuropathy with conflicting results29,33,34.

The present single-center prospective study during a one and half year duration was carried out on 150 patients (80 males and 70 females) with DPN, during their attendance to the neurology outpatient clinic. The current study stated that the MTD had significant higher DPN (50.7%), total TCSS scores (10 ± 7.5), serum levels of homocysteine (15.3 µmol/l) and methylmalonic acid (0.25 µmol/l), lower cobalamin (222 pmol/l), median conduction velocity and SNAP for superficial peroneal, and sural nerves. Also, there was a significant negative correlation between cobalamin and metformin. On the other hand, there was a significant positive correlation between TCSS and metformin.

The significant predictors' explanatory parameters associated with DPN occurrence in MTD were larger dose and longer duration of metformin usage, low cobalamin level, and high homocysteine level. Our results were in harmony with Khan et al. who concluded that patients with type 2 DM with prolonged duration of treatment with metformin were accompanied by a higher occurrence of vitamin B12 inadequacy35. So, clinicians should screen diabetic patients who are metformin users for any B12 deficiency accordingly. Our study exhibited a higher median serum level of Hcy and MMA. These variations from the normal values were highly related to metformin users. Our findings were as per that of Ahmed and Chapman et al., demonstrating that long-term metformin users compared to the non- metformin users had lower serum Cbl, higher MMA and Hcy36,37.

Our results demonstrate that metformin treatment conveys a potential hazard for the occurrence of cobalamin lack. However, this would most likely be little if cobalamin status is monitored consistently. Cobalamin inadequacy is increased among patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. There is a requirement for a more precise differential conclusion to recognize diabetic neuropathy and metformin-induced neuropathy. We also found that patients with type 2 DM, DPN, and more than 6 months of treatment by metformin demonstrated higher scores on the TCSS, indicating more clinically severe DPN when contrasted with comparative to non-metformin users. These findings were frequently connected with cumulative metformin utilization with a positive correlation between DPN and cumulative metformin dose. These results were similar to that of Holay et al. who found the incidence of neuropathy by TCSS and NCV test was significantly higher in metformin users with a positive correlation with cumulative dose and duration of metformin and a negative correlation with serum vitamin B12 levels38. Similar to our results, Singh et al. discovered a smaller yet significant difference in neuropathy scores in between metformin and non-metformin users39.

Electrophysiologically, this study exhibited that the metformin users had more severe DPN. Measurements of the mean conduction velocity and mean amplitude of SNAP of the examined nerves were altogether significantly lower in the metformin users’ group. These results are not quite the same as Wile and Toth who found an insignificant lower mean conduction velocity and mean amplitude of SNAP in the metformin users’ group40. This may be explained by the difference in demographic characteristics and longer duration of the disease in our study. The nerves of lower limbs, especially sural and superficial peroneal nerves were more sensitive to diabetic effects. This may be also supported by the study of Shibata et al. and Agarwal et al. who found that the sural nerve conduction study had the most reliable test that correlates well with the severity of diabetic PN41,42.

In our study the severity of DPN was inversely correlated with the cobalamine level and directly correlated with higher levels of both methylmalonic acid, and homocysteine. Similarly, Wile and Toth found that the clinically worsened DPN was associated with lower cobalamine level and higher levels of both methylmalonic acid, and homocysteine40. It has been shown that elevated levels of total homocysteine significantly correlated with DPN, independent of other risk factors43,44. The serum MMA positively correlated with the severity of neuropathic pain and this can be used as a useful marker in assessment of peripheral neuropathy45.

The discoveries in this study recommended that a cumulative dose of metformin is accompanied with a decrease in levels of cobalamin and deterioration of DPN. However, metformin is the main therapy in type 2 DM and has appeared to have different valuable impacts on diabetes patients accomplished by changing advanced glycosylation end products and neurodegenerative processes46,47. Hence, we advise that serum cobalamin levels should be regularly checked on Type 2 DM patients on long term metformin therapy and at higher risk of DPN. Finally, logistic regression analysis for risk factors of diabetic PN in metformin-treated patients discovered that longer metformin use duration (5.98 vs. 4 years, P = 0.01), higher metformin dose (6.43 vs. > 2000 g, P = 0.01), lower plasma level of cobalamin (OR = 3.67% CI 0.91 to 8.96, P < 0.05) and duration of diabetes (OR in = 1.2% CI 1.1 to 1.3, P < 0.05) were the most important independent factors of diabetic PN. This was similar to the comment of Alharbi, et al. that the duration and dose of metformin usage were related to the decline in levels of cobalamin. Moreover, as cobalamin has a crucial role in the homocysteine metabolism, a decrease in cobalamin would elevate the plasma level of homocysteine31. However Ahmed et al. published a cross-sectional study where vitamin B12 has measured 121 type 2 diabetics and the association with DPN was evaluated. However, there was no association between vitamin B12 deficiency and diabetic PN, and Metformin dose did not confer an increased risk on diabetic PN presence48. Similar results were reported by other authors, with controversial results, but without strong evidence that vitamin B12 deficiency influences the presence or severity of peripheral neuropathy29,49. But our results showed a positive correlation between metformin-treated patients and severity of DPN as showed by a linear correlation with TCSS (r = 0.891 and P < 0.05). Yang et al. stated that Metformin uses led to decreased cobalamin levels in diabetic patients. More research is needed to investigate the correlation between metformin use and neuropathy in diabetics and annual cobalamin measurement in MTD is recommended50.

Limitations and directions of future work

Finally, the present study had some limitations. The first limitation was the relatively small number of patients due to the limitation of resources and financial issues. Glycemic control not being assessed is also a limitation of this study.

Also, this study, cannot evaluate long-term effects of risk factors concerning the development of DPN. Further studies should be conducted on a larger number of patients for a longer duration and to follow up patients with DPN for the improvement of manifestations especially after stoppage of metformin.

Conclusion

Patients with type 2 DM who were treated with metformin for prolonged duration and higher doses were associated with lower plasma cobalamin and more severe DPN. Patients on metformin treatment must monitor regularly for plasma levels of cobalamin, methylmalonic acid, and homocysteine.

Recommendation

Routine screening of type 2 diabetic patients on metformin for vitamin B12 inadequacy is highly recommended due to its high prevalence and the significant clinical impacts that may result in DPN.

Besides, we suggest, beginning treating patients with B12 once a borderline or low level is recognized.

Author contributions

All the authors contributed equally to this study.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Okasha AH, Gaballah HH, Zakaria SS, Elmeligy SM. Role of autophagy and oxidative stress in experimental diabetes in rats. Tanta Med. J. 2017;45(3):122–128. doi: 10.4103/tmj.tmj_2_17. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dresden D. Effects of diabetes on the body and organs. Medical News Today. The science of type 2 diabetes, MediLexicon, Intl., 29 Apr. 2019. (Web).

- 3.American Diabetes Association Pharmacologic approaches to glycemic treatment: Standards of medical care in diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2019;42(Supplement 1):S90–S102. doi: 10.2337/dc19-S009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nareddy VA, Boddikuri IP, Ubedullah SK, et al. Correlation of Vit B12 levels with metformin usage among type 2 diabetic patients in a tertiary care hospital. Int. J. Adv. Med. 2018;5(5):1128–1132. doi: 10.18203/2349-3933.ijam20183459. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rizzo G, Laganà AS, Rapisarda AMC, et al. Vitamin B12 among vegetarians: Status assessment, and supplementation. Nutrients. 2016;8(12):767. doi: 10.3390/nu8120767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nielsen MJ, Rasmussen MR, Andersen CB, Nexo E, Moestrup SK. Vitamin B12 transport from food to the body’s cells. A sophisticated, multistep pathway. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2012;9:345–354. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2012.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kumar A, Palfrey HA, Pathak R, Kadowitz PJ, Gettys TW, Murthy SN. The metabolism and significance of homocysteine in nutrition and health. Nutr. Metab. 2017;22(14):78. doi: 10.1186/s12986-017-0233-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hasan T, Arora R, Bansal AK, et al. Disturbed homocysteine metabolism is associated with cancer. Exp. Mol. Med. 2019;51(2):1–3. doi: 10.1038/s12276-019-0216-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Škovierová H, Vidomanová E, Mahmood S, et al. The molecular and cellular effect of homocysteine metabolism imbalance on human health. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016;17(10):1733. doi: 10.3390/ijms17101733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Esse R, Barroso M, de Almeida IT, Castro R. The contribution of homocysteine metabolism disruption to endothelial dysfunction: State-of-the-art. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019;20(4):867. doi: 10.3390/ijms20040867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bansal S, Kapoor S, Singh GP, Yadav S. Serum homocysteine levels in type 2 diabetes mellitus patients. Int. J. Contemp. Med. Res. 2016;3(11):3393–3396. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wolffenbuttel BH, Wouters HJ, et al. The many faces of cobalamin deficiency (vitamin B12) Mayo Clin. Proc. Innov. Qual. Outcomes. 2019;3(2):200–214. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocpiqo.2019.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hannibal L, Lysne V, Bjørke-Monsen AL, et al. Biomarkers and algorithms for the diagnosis of vitaminB12 deficiency. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2016;3:27. doi: 10.3389/fmolb.2016.00027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mastroianni A, et al. Monitoring vitamin B12 in women treated with metformin for primary prevention of breast cancer and age-related chronic diseases. Nutrients. 2019;11:1020. doi: 10.3390/nu11051020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tu MC, Lo CP, Huang CF, Hsu YH, Wang TL. Neurological presentations and therapeutic responses to cobalamin deficiency. Neuropsychiatry. 2017;7(3):185–196. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Iqbal Z, Azmi S, Yadav R, et al. Diabetic peripheral neuropathy: Epidemiology, diagnosis, and pharmacotherapy. Clin. Ther. 2018;40(6):828–849. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2018.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Juster-Switlyk K, Smith AG. Updates in diabetic peripheral neuropathy. F1000Research. 2016 doi: 10.12688/f1000research.7898.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu X, Xu Y, An M, Zeng Q. The risk factors for diabetic peripheral neuropathy: A meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(2):e0212574. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0212574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alam U, Riley DR, Jugdey RS, et al. Diabetic neuropathy and gait: A review. Diabetes Ther. 2017;8:1253. doi: 10.1007/s13300-017-0295-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pop-Busui R, Boulton AJM, Feldman EL, et al. Diabetic neuropathy: A position statement by the American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care. 2017;40(1):136–154. doi: 10.2337/dc16-2042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Román-Pintos LM, Villegas-Rivera G, Rodríguez-Carrizalez AD, Miranda-Díaz AG, Cardona-Muñoz EG. Diabetic polyneuropathy in type 2 diabetes mellitus: Inflammation, oxidative stress, and mitochondrial function. J. Diabetes Res. 2016 doi: 10.1155/2016/3425617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Islam MR, Rahman T, Habib R, et al. Electrophysiological patterns of diabetic polyneuropathy: Experience from a Tertiary Care Hospital of Bangladesh. BIRDEM Med. J. 2017;7(2):114–120. doi: 10.3329/birdem.v7i2.32448. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Park JH, Won JC. Patterns of nerve conduction abnormalities in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus according to the clinical phenotype determined by the current perception threshold. Diabetes Metab. J. 2018;42(6):519–528. doi: 10.4093/dmj.2018.0068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.American Diabetes Association Standards of medical care in diabetes 2019. Diabetes Care. 2019;42(Supplement 1):S34–S45. doi: 10.2337/dc19-S004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Udayashankar DA, Premraj SS, Mayilananthi K, Naragond V. Applicability of Toronto clinical neuropathy scoring and its correlation with diabetic peripheral neuropathy: A prospective cross-sectional study. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2017;11(12):OC10–OC13. [Google Scholar]

- 26.de Groot-Kamphuis DM, van Dijk PR, Groenier KH, Houweling ST, Bilo HJ, Kleefstra N. Vitamin B12 deficiency and the lack of its consequences in type 2 diabetes patients using metformin. Neth. J. Med. 2013;71:386–390. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Preston, D.C. & Shapiro, B.E. Polyneuropathies. In Electromyography and Neuromuscular Disorders Clinical and Electromyographic Correlation (eds Preston, D. C. & Shapiro, B. E.) 384–416 (Elsevier, Amsterdam, 2013).

- 28.Kalauokalani D, Cowan P. Painful diabetic neuropathy—Clinic communication gapsand opportunities. J. Pain. 2013;14(4):S31. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2013.01.479. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Roy RP, Ghosh K, Ghosh M, Acharyya A, et al. Study of vitamin B12 deficiency and peripheral neuropathy in metformin-treated early type 2 diabetes mellitus. Indian J. Endocrinol. Metab. 2016;20(5):631–637. doi: 10.4103/2230-8210.190542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.De Jager J, Kooy A, Lehert P, et al. Long-term treatment with metformin in patients with type 2 diabetes and risk of vitamin B-12 deficiency: Randomized placebo-controlled trial. BMJ. 2010;340:2181–2187. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c2181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Alharbi TJ, Tourkmani AM, Abdelhay O, et al. The association of metformin use with vitamin B12 deficiency and peripheral neuropathy in Saudi individuals with type 2 diabetes mellitus. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(10):e0204420. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0204420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Khattar D, Khaliq F, Vaney N, Madhu SV. Delayed auditory conduction in diabetes: Is metformin-induced vitamin B12 deficiency responsible? Funct. Neurol. 2016;31(2):95–100. doi: 10.11138/FNeur/2016.31.2.095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Elhadd T, Ponirakis G, Dabbous Z, et al. Metformin use is not associated with B12 deficiency or neuropathy in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus in Qatar. Front. Endocrinol. 2018;9:248. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2018.00248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fatima S, Noor S. A review on effects of metformin on vitamin B12 status. Am. J. Phytomed. Clin. Ther. 2013;1(8):652–660. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Khan A, Shafiq I, Hassan Shah M. Prevalence of vitamin B12 deficiency in patients with type II diabetes mellitus on metformin: A study from Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. Cureus. 2017;9(8):e1577. doi: 10.7759/cureus.1577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ahmed MA. Metformin and vitamin B12 deficiency: Where do we stand? J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci. 2016;19(3):382–398. doi: 10.18433/J3PK7P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chapman LE, Darling AL, Brown JE. Association between metformin and vitamin B12 deficiency in patients with type 2 diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Metab. 2016;42(5):316–327. doi: 10.1016/j.diabet.2016.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Holay MP, Vyawahare M, Shekar K. Serum B12 levels in type ii diabetics on metformin therapy and its association with clinical neuropathy. Int. J. Biomed. Adv. Res. 2017;8(08):321–326. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Singh AK, Kumar A, Karmakar D, Jha RK. Association of B12 deficiency and clinical neuropathy with metformin use in type 2 diabetes patients. J. Postgrad. Med. 2013;59:253–257. doi: 10.4103/0022-3859.123143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wile DJ, Toth C. Association of metformin, elevated homocysteine, and methylmalonic acid levels and clinically worsened diabetic peripheral neuropathy. Diabetes Care. 2010;33(1):156–161. doi: 10.2337/dc09-0606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shibata Y, Himeno T, Kamiya T, Tani H, Nakayama T, Kojima C, Kamiya H. Validity and reliability of a point-of-care nerve conduction device in diabetes patients. J. Diabetes Investig. 2019;10(5):1291–1298. doi: 10.1111/jdi.13007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Agarwal S, Lukhmana S, Kahlon N, Malik P, Nandini H. Nerve conduction study in neurologically asymptomatic diabetic patients and correlation with glycosylated hemoglobin and duration of diabetes. Natl. J. Physiol, Pharm. Pharmacol. 2018;8(11):1533–1538. doi: 10.5455/njppp.2018.8.0826828082018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Molina M, Gonzalez R, Folgado J, Real J, Martínez-Hervás S, Priego A, et al. Correlation between plasma concentrations of homocysteine and diabetic polyneuropathy evaluated with the Semmes-Weinstein monofilament test in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Med. Clin. 2013;141:382–386. doi: 10.1016/j.medcli.2012.09.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.González R, Pedro T, Martinez-Hervas S, Civera M, Antonia M, Catalá M, et al. Plasma homocysteine levels are independently associated with the severity of peripheral polyneuropathy in type 2 diabetic subjects. J. Peripher. Nerv. Syst. 2012;17:191–196. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8027.2012.00408.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jin-Sung P, Donghwi P, Ko P, Kyunghun K. Serum methylmalonic acid correlates with neuropathic pain in idiopathic Parkinson’s disease. Neurol. Sci. 2017 doi: 10.1007/s10072-017-3056-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Singh VP, Bali A, Singh N, Jaggi AS. Advanced glycation end products and diabetic complications. Korean J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2014;18(1):1–14. doi: 10.4196/kjpp.2014.18.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Markowicz-Piasecka M, Sikora J, Szydłowska A, Skupień A, Mikiciuk-Olasik E, Huttunen KM. Metformin—A future therapy for neurodegenerative diseases. Pharm. Res. 2017;34(12):2614–2627. doi: 10.1007/s11095-017-2199-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ahmed MA, Muntingh G, Rheeder P. Vitamin B12 deficiency in metformin-treated type-2 diabetes patients, prevalence and association with peripheral neuropathy. BMC Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2016;17(1):44. doi: 10.1186/s40360-016-0088-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Russo T, Giandalia A, Romeo EL, et al. Diabetic neuropathy is not associated with homocysteine, folate, vitamin B12 levels, and MTHFR C677T mutation in type 2 diabetic outpatients taking metformin. J. Endocrinol. Investig. 2016;39(3):305–314. doi: 10.1007/s40618-015-0365-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yang W, Cai X, Wu H, Ji L. Associations between metformin use and vitamin B 12 levels, anemia, and neuropathy in patients with diabetes: A meta-analysis. J. Diabetes. 2019;11(9):729–743. doi: 10.1111/1753-0407.12900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]