Abstract

The American Venous Forum (AVF) and the Society for Vascular Surgery set forth these guidelines for the management of endothermal heat-induced thrombosis (EHIT). The guidelines serve to compile the body of literature on EHIT and to put forth evidence-based recommendations. The guidelines are divided into the following categories: classification of EHIT, risk factors and prevention, and treatment of EHIT.

One major feature is to standardize the reporting under one classification system. The Kabnick and Lawrence classification systems are now combined into the AVF EHIT classification system. The novel classification system affords standardization in reporting but also allows continued combined evaluation with the current body of literature. Recommendations codify the use of duplex ultrasound for the diagnosis of EHIT. Risk factor assessments and methods of prevention including mechanical prophylaxis, chemical prophylaxis, and ablation distance are discussed.

Treatment guidelines are tailored to the AVF EHIT class (ie, I, II, III, IV). Reference is made to the use of surveillance, antiplatelet therapy, and anticoagulants as deemed indicated, and the recommendations incorporate the use of the novel direct oral anticoagulants. Last, EHIT management as it relates to the great and small saphenous veins is discussed.

Summary

Classification of endothermal heat-induced thrombosis (EHIT)

Guideline 1.1: Classification system for EHIT

We suggest the use of a classification system to standardize the diagnosis, reporting, and treatment of EHIT. [BEST PRACTICE]

Guideline 1.2: Classification system based on duplex ultrasound

We suggest that venous duplex ultrasound with the patient in the upright position, performed within 1 week of the index procedure, forms the basis for the classification system. [BEST PRACTICE]

Guideline 1.3: Kabnick classification system

We suggest consideration of the Kabnick classification for reporting of EHIT at the saphenofemoral (great saphenous vein [GSV]) or saphenopopliteal (small saphenous vein [SSV]) junction. [BEST PRACTICE]

Guideline 1.4: Lawrence classification system

We suggest consideration of the Lawrence classification for reporting of EHIT at the saphenofemoral (GSV) or saphenopopliteal (SSV) junction. [BEST PRACTICE]

Guideline 1.5: American Venous Forum EHIT classification system

We suggest preferential use of the unified American Venous Forum EHIT classification system to standardize ongoing reporting, given that it maintains the essence of the Kabnick and Lawrence classification systems, remains recognizable, and may be used for ongoing meta-analyses and systematic reviews. It is a four-tiered classification: I, junction; II, <50% lumen; III, >50% lumen; IV, occlusive deep venous thrombosis. [BEST PRACTICE]

Risk factors and prevention

Guideline 2.1: Risk factors for EHIT

Some possible but inconsistent predictors or risk factors for EHIT include large GSV diameter, previous history of venous thromboembolic disease, and male sex. These may be considered in the preprocedure phase, but the evidence is inconsistent. [GRADE – 2; LEVEL OF EVIDENCE – C]

Guideline 2.2: Prevention of EHIT with chemical prophylaxis

The use of chemical prophylaxis for prevention of EHIT should be tailored to the patient after an assessment of the risks, benefits, and alternatives. [GRADE – 2; LEVEL OF EVIDENCE – C]

Guideline 2.3: Prevention of EHIT with mechanical prophylaxis

The use of mechanical prophylaxis for prevention of EHIT should be tailored to the patient after an assessment of the risks, benefits, and alternatives. [GRADE – 2; LEVEL OF EVIDENCE – C]

Guideline 2.4: Prevention of EHIT by increasing ablation distance

There is a trend toward decreased EHIT when ablation is initiated >2.5 cm from the saphenofemoral (GSV) or saphenopopliteal (SSV) junction. [GRADE – 2; LEVEL OF EVIDENCE – C]

Treatment of EHIT

Guideline 3.1: Classification system

We suggest the stratification of treatment based on an accepted EHIT classification system. [BEST PRACTICE]

Guideline 3.2: Treatment for EHIT I

We suggest no treatment or surveillance for EHIT I. [GRADE – 2; LEVEL OF EVIDENCE – C]

Guideline 3.3: Treatment for EHIT II

We suggest no treatment of EHIT II but do suggest weekly surveillance until thrombus resolution. In high-risk patients, consideration may be given to antiplatelet therapy vs prophylactic or therapeutic anticoagulation with weekly surveillance. Treatment would cease after thrombus retraction or resolution to the saphenofemoral (GSV) or saphenopopliteal (SSV) junction. [GRADE – 2; LEVEL OF EVIDENCE – C]

Guideline 3.4: Treatment for EHIT III

We suggest treatment with therapeutic anticoagulation for EHIT III, weekly surveillance, and cessation of treatment after thrombus retraction or resolution to the saphenofemoral (GSV) or saphenopopliteal (SSV) junction. [GRADE – 1; LEVEL OF EVIDENCE – B]

Guideline 3.5: Treatment for EHIT IV

We suggest that treatment should be individualized, taking into account the risks and benefits to the patient. Reference may be made to the Chest guidelines for the treatment of deep venous thrombosis. [GRADE – 1; LEVEL OF EVIDENCE – A]

Management of SSV

Guideline 4.1: Management of EHIT for the SSV

We suggest that management and treatment for EHIT as it relates to the SSV parallel those for the GSV. [GRADE – 2; LEVEL OF EVIDENCE – C]

Introduction and rationale

Western data suggest that chronic venous insufficiency has a significant impact on the population, both quantitatively and qualitatively.1 Chronic venous insufficiency ranges in presentation from the asymptomatic state to varicose veins, edema, skin changes, and ulceration. Varicose veins are found in upward of 20% to 30%, skin changes in up to 6%, and active venous ulcerations in up to 0.5% of the population.2,3 Clinical presentation is also coupled with variable impacts on quality of life ranging from cosmetic concerns to debilitating symptoms and limb- and life-threatening complications.4–7

Endothermal ablation revolutionized the treatment of clinically significant superficial venous reflux. The technologies that have undergone the most robust evaluation are endovenous laser ablation (EVLA) and radiofrequency ablation (RFA). They have been proven safe, efficacious, and durable.8–12 Performed with tumescent anesthesia, RFA and EVLA allow a transition of care to the ambulatory setting. Moreover, these techniques demonstrate improved periprocedural outcomes as well as a more rapid return to work compared with surgical stripping.13–15

In an early report, Hingorani et al.16 observed that endovenous thermal ablations were associated with deep venous thrombosis (DVT) of the common femoral vein on postprocedure surveillance ultrasound. Other reports from the early 2000s also indicated an increased risk of DVT that ranged between 0% and 8%.17–19 Later publications started referring to these postoperative thrombi as thrombus extension rather than DVT as it was believed that they represented a distinct phenomenon.20,21

Although the occurrence of superficial thrombus within the treated vein segment is considered to be a normal ultrasound finding, its propagation into a deep vein may pose a risk for the development of symptomatic DVT and pulmonary embolism (PE).19,22

In 2006, Kabnick first introduced the term endothermal-heat induced thrombosis (EHIT), defining it as the propagation of thrombus into the deep vein contiguous with the ablated superficial vein.23 This definition has been widely adopted to describe this clinical entity. From a diagnostic and clinical standpoint, EHIT is an entity separate from classic DVT. EHIT, for the most part, has a distinct sonographic appearance, behaves like a stable thrombus, and often regresses spontaneously after a few weeks of observation or a short course of anticoagulation.23

Contemporary reported EHIT rates after endovenous ablation range from 0% to 3%.24,25 Most EHITs are asymptomatic, and the diagnosis is usually made on routine duplex ultrasound follow-up; however, the presence of a thrombus at the junction or a history of recent endothermal venous ablation has been associated with rare cases of PE.18,19,22,26 Typically, these thrombi are detected by postprocedure duplex ultrasound examinations performed anywhere from 24 to 72 hours to 1 to 2 weeks after the procedure, depending on the local ultrasound surveillance protocol. They appear as a hyperechogenic, noncompressible area with abnormal venous flow and augmentation involving the saphenofemoral or saphenopopliteal junction after great saphenous vein (GSV) or small saphenous vein (SSV) ablations, respectively.23,27,28

Although the occurrence of EHIT is attributed to an actual thermomechanical event, that is, the presence of a catheter delivering thermal energy in proximity to a deep vein, the exact differences between RFA and EVLA in terms of mechanism of excessive thrombus formation are unknown. Whereas EHIT is considered anatomically a form of DVT, its clinical course is more benign than an unprovoked DVT or one occurring in a remote vein segment.

In reporting of thrombotic complications after venous ablation, it is important to consider the full spectrum of findings captured by surveillance ultrasound. The majority of EHIT reports aim to describe those thrombi protruding into the common femoral vein or the popliteal vein. However, when deep calf thrombi are identified on postprocedure venous ultrasound, they may still be considered EHIT if the thrombus extends into a calf vein from a treated perforator, a treated SSV directly draining into a gastrocnemius vein, or a treated below-knee GSV through a perforator.29,30

Examples of non-EHIT DVT include a thrombus in a deep vein nonadjacent to the saphenofemoral junction after GSV ablation, a thrombus remote from the saphenopopliteal junction after SSV ablation, a remote calf vein thrombus after GSV ablation, and a DVT in the contralateral limb. Both types of DVT, EHIT and non-EHIT, may be present in the same patient.22,31

Based on current literature, practitioners report that the overall rate of DVT after endovenous ablations is <1%, and EHIT is three to four times more likely to occur than non-EHIT DVT.22,32 Classic DVTs do not retract or resolve as early as EHITs and are likely to be due to other eliciting factors, such as excessive immobilization, ill-fitted compression hosiery, or activation of the coagulation cascade during endothermal ablation at a remote location.33

The sensitivity of ultrasound for diagnosis of DVT varies widely, particularly for below-knee duplex ultrasound scans. It is possible that the incidence of calf DVT after endovenous ablations is higher than reported, and it may account for some cases of PE of unknown source. Whereas a clear distinction between EHIT and non-EHIT DVT should be made on the basis of anatomic location as discussed before, it is unclear whether any pathologic differentiation can be established on the basis of ultrasound appearance of the thrombus.

In an animal study comparing histologic specimens of veins with classic DVT and those with EHIT after RFA, it was demonstrated that EHIT displays a significantly higher hypercellular response, fibroblastic reaction, and edema. Also, when authors examined the two groups, thrombi in EHIT animals were more echogenic compared with their DVT counterparts.33,34 Preliminary human studies have confirmed these ultrasound findings as EHIT appears more echogenic and displays a mildly echoreflective thrombus that distinguishes EHIT from the usual echolucent characteristics of classic acute DVT.35

It is currently believed that most EHITs develop within 72 hours, but postprocedure surveillance ultrasound scans may occasionally identify an EHIT after 7 days and even up to 4 weeks after endovenous ablation.31,34–36 As timing of occurrence is not fully understood, a controversial point is whether an EHIT occurring more than 1 week after ablation should be regarded and treated as an EHIT or as a classic DVT.37,38

In a prospective study by Lurie and Kistner31 of patients undergoing RFA of the GSV, levels of C-reactive protein and D-dimer were measured before and after treatment. Both markers significantly increased at 24 to 36 hours and returned to the baseline values at 1 month after the treatment, thus indicating that after venous surgical trauma, both inflammation and hemostatic activation are present for a prolonged time. Given this evidence, the practitioner can assume that any thrombus occurring at the site of endovenous ablation within 30 days of the procedure could be directly or indirectly related to the procedure itself.

Some authors have introduced the broader term postablation superficial thrombus extension to indicate a thrombus extension from the superficial to the deep system after any kind of chemical or thermal endovenous ablation.39 They also observed that postablation superficial thrombus extension differs from a classic DVT because it usually occurs within 1 week, does not progress, and typically resolves within 2 weeks.

In an effort to provide clinical guidelines for the management of thromboembolic events occurring after endovenous thermal ablation and keeping in mind that any of these events may potentially lead to serious consequences, such as PE, we recommend the definition of the following entities:

EHIT: any thrombus detected by ultrasound within 4 weeks of endovenous thermal ablation originating from the treated vein and protruding into a deep vein.

Non-EHIT DVT: a DVT occurring in a venous segment not contiguous with the thermally ablated vein.

Postablation superficial venous thrombosis: presence of thrombus in a superficial vein other than the treated vein. This vein may or may not be contiguous with the ablated vein.

We recommend that future reports on thromboembolic events after endovenous thermal ablation include detailed data on anatomic location, clinical presentation, and time of occurrence of these events to validate or to update the current proposed definitions. Ideally, detailed sonographic features and progression of all these thrombi at follow-up ultrasound examinations should be reported.

Non-EHIT thrombotic events that occur during thermal ablation are likely to be triggered by systemic factors that have more to do with an acquired prothrombotic state than with the thermal energy itself. Therefore, the presence of thrombotic events other than EHIT must be also recognized and reported.

Methodology

The American Venous Forum (AVF) guidelines committee in collaboration with the Society for Vascular Surgery created a writing group to analyze the available literature on EHIT to gauge the quality of clinical evidence and to provide guidance on its diagnosis and treatment. A total of four subgroups were tasked to accomplish the following: to establish the EHIT definition, to discuss the available EHIT classification systems, to evaluate prevention strategies and its risk factors, and to appraise treatment options.

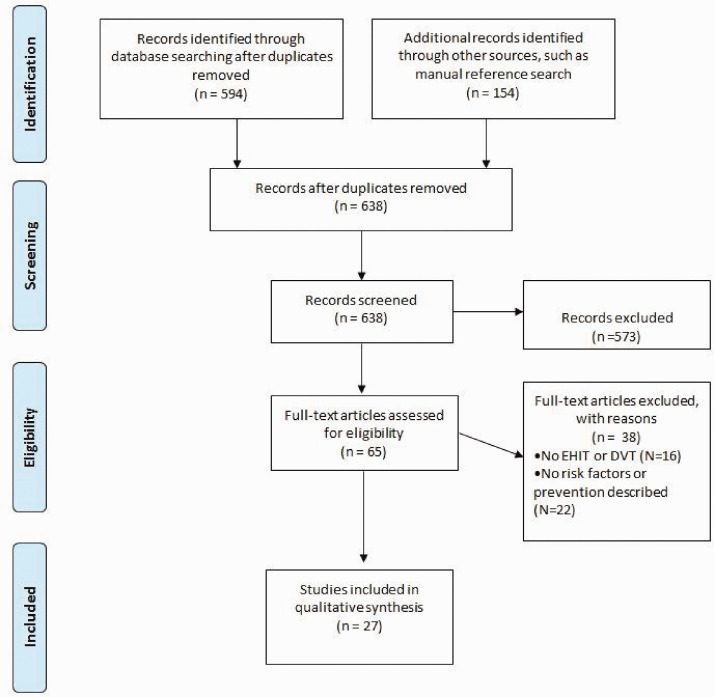

A systematic literature review of four scientific repositories was performed, including PubMed, Embase (Excerpta Medica Database), Cochrane libraries, and Web of Sciences, to identify potential publications related to EHIT. The terms used in this review were primarily related to the adverse outcome studied, EHIT in patients undergoing either laser or radiofrequency venous ablation. However, related terms, such as DVT and superficial thrombophlebitis (STP), were also used during our search, based on the lack of a clear definition of EHIT before 2006. Procedures performed to ablate the GSV, SSV, and accessory saphenous veins were included. Endovenous ablation of perforating veins was excluded. There was no restriction regarding language or research design (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flow chart. DVT, Deep venous thrombosis; EHIT, endovenous heat-induced thrombosis.

The Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) system was chosen to gauge the quality of published evidence and to rank the strength of recommendations.40 This grading system comprises four categories of recommendations paired with a classification of recommendations as strong or weak to aid health care providers in recommending a specific workup or treatment strategy. Grade 1 recommendations differ from grade 2 on the basis of the balance between risks and benefits of a practice. Grade 1 recommendations rely on outcomes that show the benefits involved in a certain practice clearly outweigh its risks. Conversely, grade 2 recommendations show proximity between risks and benefits of a practice that requires further discussion between provider and patient regarding whether a test or treatment should be performed according to the patient’s specific clinical scenario. The grades of recommendation rely on three distinct categories used to gauge level of clinical evidence (A, high quality; B, moderate quality; and C, low quality). The GRADE system has been previously used by the Society for Vascular Surgery; further information on this system has been published elsewhere.40

Classification of EHIT

Guideline 1.1: Classification system for EHIT

We suggest the use of a classification system to standardize the diagnosis, reporting, and treatment of EHIT. [BEST PRACTICE]

Guideline 1.2: Classification system based on duplex ultrasound

We suggest that venous duplex ultrasound with the patient in the upright position, performed within 1 week of the index procedure, forms the basis for the classification system. [BEST PRACTICE]

Ultrasound-based classification systems have been developed for EHIT, but there is a clear lack of standardization among the systems. Moreover, the initial reporting of the entity was in the context of DVT, and the explicit association with endothermal ablation had not yet been made. In spite of the differences between classification systems, the similarities are significant, which may allow their unification into a single system. The success of any proposed unified classification system is predicated on delineating clinically significant gradations of the disease being reported. Ultimately, a unified EHIT classification will help standardize reporting of the disease in the literature as well as in clinical practice.

The goals of the proposed EHIT classification system are as follows:

to provide a standardized classification for vascular laboratory reporting of EHIT;

to provide a single classification system for EHIT in developing practice guidelines regarding the timing of duplex ultrasound, technique of duplex ultrasound, and imaging characteristics;

to provide a uniform classification system for data reporting and research; and

to allow the possibility of the application of the classification system to be expanded to nonthermal ablation modalities.

Classification system prerequisites

Although different imaging systems (computed tomography, magnetic resonance venography) may be used for the classification of EHIT, duplex ultrasound should serve as the foundation. It is the “gold standard” for evaluating the peripheral venous anatomy, and it is the most readily available in outpatient venous treatment centers.34 The diagnostic ultrasound should be performed within 1 week of the index procedure.41,42 The data suggest that most EHITs develop within 72 hours, but postprocedure surveillance ultrasound scans have identified an EHIT up to 4 weeks after endovenous ablation.31,34–36 The diagnostic duplex ultrasound examination can be performed in either the supine or standing position, although there is a greater incidence of false-positive results in the supine position. Therefore, all identified EHITs should be confirmed in the standing position, or supine on a tilt table, to ensure that the thrombus does not retract peripherally into the superficial vein lumen, thereby changing the diagnosis. Measurements should be taken with an electronic cursor in transverse, axial, and orthogonal positions to determine the distance and relationship between the EHIT thrombus and the vein wall as well as the presence, absence, and extent of protrusion into the deep system lumen.

We recommend that the imaging study be conducted in an accredited vascular laboratory (eg, Intersocietal Accreditation Commission, American College of Radiology Ultrasound Accreditation, and others) by a technologist who is trained in duplex ultrasound and can obtain images that accurately identify the effect of the endovenous thermal procedure on the treated vein and vein wall at or near the junction of the superficial axial vein within the deep venous system. This will typically occur at the GSV/common femoral vein junction and the SSV/popliteal vein junction; however, EHIT can also occur at any junction between the superficial and deep venous systems after an endovenous thermal ablation procedure.

The key to the classification system’s being clinically relevant is to determine whether a thrombus has protruded into the deep venous system as well as the extent of the protrusion. For example, one of the classification systems allows determination of the exact site of the thrombus and vein closure in the superficial system relative to the superficial epigastric vein. This may be used for future outcomes studies of symptom relief or recurrence, for example; however, there is no known clinical outcome or treatment modification that correlates with this anatomic boundary. On the other hand, an occlusion of the adjacent deep vein lumen should be treated as a DVT.

Current classification systems

Guideline 1.3: Kabnick classification system

We suggest consideration of the Kabnick classification for reporting of EHIT at the saphenofemoral (GSV) or saphenopopliteal (SSV) junction. [BEST PRACTICE]

Guideline 1.4: Lawrence classification system

We suggest consideration of the Lawrence classification for reporting of EHIT at the saphenofemoral (GSV) or saphenopopliteal (SSV) junction. [BEST PRACTICE]

Guideline 1.5: AVF EHIT classification system

We suggest preferential use of the unified AVF EHIT classification system to standardize ongoing reporting, given that it maintains the essence of the Kabnick and Lawrence classification systems, remains recognizable, and may be used for ongoing meta-analyses and systematic reviews. It is a four-tiered classification: I, junction; II, <50% lumen; III, >50% lumen; IV, occlusive DVT. [BEST PRACTICE]

The EHIT classification systems that have gained traction in the literature are as follows. The first described classification system is the Kabnick classification (Table 1).23

Table 1.

Kabnick endothermal heat-induced thrombosis (EHIT) classification.

| Class | Definition |

|---|---|

| I | Thrombus extended up to and including the deep vein junction |

| II | Thrombus propagation into the adjacent deep vein but comprising <50% of the deep vein lumen |

| III | Thrombus propagation into the adjacent deep vein but comprising >50% of the deep vein lumen |

| IV | Occlusive deep vein thrombus contiguous with the treated superficial vein |

EHIT I refers to a benign condition whereby management is not altered. The thrombus propagation remains peripheral to the associated deep vein, and no further treatment is required. In much of the early literature, this entity was being combined with more significant propagation of the thrombus, thereby resulting in falsely elevated incidence of disease.16,20 Moreover, there have not been any reported cases of progression of EHIT I to a higher level. For the most part, interest in EHIT I remains academic.

EHIT II remains the most commonly identified entity. Treatment recommendations have varied from anticoagulation until thrombus regression to antiplatelet treatment until thrombus regression and continued observation.20,23,43 This is an area that warrants ongoing study and characterization.

EHIT III comprises a more severe form of nonocclusive thrombosis, and most practitioners are in agreement to treat with an antiplatelet or anticoagulant. Interestingly, this is an exceedingly rare designation, given that most EHITs are small and may be classified as an EHIT II, or they present at the other extreme, which is an occlusive DVT or EHIT IV. The current consensus is that EHIT IV is treated as an acute occlusive DVT according to the Chest guidelines.44 Given the low-morbidity nature of the treatment, EHIT IVs are seldom identified in the contemporary literature.

The Lawrence classification system is as follows (Table 2).26 Levels 1, 2, and 3 are encompassed by Kabnick EHIT I. In the stated reference, no further treatment was recommended for EHITs that progressed to level 1 or level 2. A level 3 EHIT was treated according to the discretion of the operator. Level 3 applied only to 4.3% of the patient cohort, and treatment with anticoagulation vs observation demonstrated no differences in outcomes, nor was there any instance of further thrombus extension. No definitive conclusions could be made on the basis of the low sampling.

Table 2.

Lawrence endothermal heat-induced thrombosis (EHIT) classification.

| Level | Definition |

|---|---|

| 1 | Thrombus extension that remains peripheral to the epigastric vein |

| 2 | Thrombus extension that is flush with the orifice of the epigastric vein |

| 3 | Thrombus extension that is flush with the saphenofemoral junction |

| 4 | Thrombus bulging into the CFV |

| 5 | Thrombus bulging into the CFV and adherent to the wall of the CFV past the saphenofemoral junction |

| 6 | Thrombus extension into the CFV consistent with a DVT |

CFV, Common femoral vein; DVT, deep venous thrombosis.

Levels 4, 5, and 6 roughly correlate to Kabnick EHIT II, III, and IV. Treatment with anticoagulation resulted in regression of thrombus in all cases of level 4 or level 5 EHIT to a level 2 or level 3 EHIT, and this occurred within an average of 16 days. As with most of the literature, there were no instances of an occlusive thrombus (level 6). Consistent with the Kabnick EHIT classification, clinically significant alterations in management occur when the thrombus extends into the respective deep vein lumen. In this sense, levels 4, 5, and 6 serve the same purpose as Kabnick EHIT II, III, and IV, with the lower gradations being an anatomic characterization of benign disease that may benefit from further research.

The Harlander-Locke classification system was devised specifically for the SSV (Table 3).27 The thought behind creating a supplemental scheme for the SSV relates to the variability in anatomy associated with the saphenopopliteal junction.45 Much like the prior classification schemes, a distinction is made between thrombus propagation into the popliteal vein and thrombus that remains within the SSV. The cutoff in this instance is between class B and class C, and there are no further gradations with regard to DVT unless an occlusive thrombus is identified (class D). In this particular study, asymptomatic patients were not evaluated by duplex ultrasound. Moreover, classes C and D comprised only two patients, rendering it challenging to generalize any conclusions.

Table 3.

Harlander-Locke classification for endothermal heat-induced thrombosis (EHIT), specific for small saphenous vein (SSV).

| Class | Definition |

|---|---|

| A | Thrombus propagation peripheral to the SPJ |

| B | Thrombus propagation extending to the SPJ |

| C | Thrombus propagation into the popliteal vein but nonocclusive |

| D | Occlusive DVT of the popliteal vein |

DVT, Deep venous thrombosis; SPJ, saphenopopliteal junction.

Table 4.

Sampling of classification schemes used in the literature.

| Reference | Kabnick | Lawrence | Other |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ahn,46 Dermatol Surg 2016 | X | ||

| Chi,47 Vasc Med 2011 | X | ||

| Jones,43 J Invasive Card 2014 | X | ||

| Kane,48 Ann Vasc Surg 2014 | X | ||

| Harlander-Locke,27 J Vasc Surg 2013 | X | ||

| Lurie,31 J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord 2013 | X | ||

| Lin,33 Vasc Endovascular Surg 2012 | X | X | |

| Monahan,50 Vasc Endovascular Surg 2012 | X | ||

| Haqqani,35 J Vasc Surg 2011 | X | ||

| Lawrence,26 J Vasc Surg 2010 | X | ||

| Marsh,22 Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2010 | X |

Table 5.

American Venous Forum (AVF) endothermal heat-induced thrombosis (EHIT) classification.

| Class | Definition |

|---|---|

| I | Thrombus without propagation into the deep vein a. Peripheral to superficial epigastric vein b. Central to superficial epigastric vein, up to and including the deep vein junction |

| II | Thrombus propagation into the adjacent deep vein but comprising <50% of the deep vein lumen |

| III | Thrombus propagation into the adjacent deep vein but comprising >50% of the deep vein lumen |

| IV | Occlusive deep vein thrombus contiguous with the treated superficial vein |

Use of the current classification schemes

To date, these classification schemes have been used inconsistently across the literature. A sampling of the literature with the respective classifications used illustrates this (Table 4).

Unified AVF EHIT classification

Given the heterogeneity in reporting and outcomes, the authors propose to combine the classification systems accordingly (Table 5). The new classification system is based on previously published data, and therefore the essence of the classification system has remained unchanged. Having noted this, it includes definitions that are broad enough to encompass the necessary disease for both research and clinical purposes. Last, it remains simple, recognizable, and consistent with the widely accepted notion that thrombi propagating into the deep vein should be treated differently compared with thrombi that do not extend beyond the saphenofemoral or saphenopopliteal junction.

Specifically, EHIT I refers to a benign condition whereby management is not altered. It is unknown whether termination of the thrombus peripheral or central to the superficial epigastric vein bears any clinical significance with regard to symptoms or overall prognosis. Therefore, to maintain this data point for research purposes, there is an (a) and (b) subdivision, which allows future study and evaluation.

EHIT II remains the most commonly identified of the various categories. Treatment recommendations have varied from anticoagulation until thrombus regression to antiplatelet medication until thrombus regression and even observation with serial duplex ultrasound examinations. This is an area that warrants continued study.

EHIT III comprises a more severe form of nonocclusive thrombosis, and most are in agreement to treat with an antiplatelet or anticoagulant. The consensus currently is that all EHIT IVs are treated as acute occlusive DVTs according to the Chest guidelines.

Conclusions

The reporting of the EHIT phenomenon in a consistent way is essential to all other aspects of diagnosis, prevention, and treatment. To a great extent, this has occurred already with the classification schemes that have been created, and there has been a commensurate improvement in the consistency of the associated literature. With the increased volume of procedures being performed, the data being acquired (especially within national databases such as the Vascular Quality Initiative), and the advent of widespread use of the nonthermal ablation techniques, the importance of a consistent classification will increase accordingly.

Risk factors and prevention of EHIT

Risk factors

Guideline 2.1: Risk factors for EHIT

Some possible but inconsistent predictors or risk factors for EHIT include large GSV diameter, previous history of venous thromboembolic disease, and male sex. These may be considered in the preprocedure phase, but the evidence is inconsistent. [GRADE – 2; LEVEL OF EVIDENCE – C]

Whereas these relatively new ablation techniques have improved the quality of care rendered to patients with venous insufficiency, as with any new technique, there are unique complications. Early reports suggested that postprocedure thrombosis rates may be as high as 16%.16 The aim of this systematic review is to investigate the risk factors of EHIT and to assess prevention strategies used during endothermal ablation.

The correlation of some general and other venous thromboembolism (VTE)-related risk factors with EHIT has been investigated, such as age, sex, use of statins, presence of venous stasis ulcers, history of thrombophilia, diameter of saphenous vein, ablation modality, location of the catheter tip, operative time, and concomitant microphlebectomy. A description of cohort characteristics of the references included is shown in Table 6.

Table 6.

Cohort characteristics of selected studies related to endothermal heat-induced thrombosis (EHIT) risk factors and prevention.

| References | Cohort, No. | Technique | Vein treated |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ahn et al.,46 2016 | 91 RF | Only RF | GSV, SSV; adjunct stab phlebectomies (14%) and sclerotherapy (36%) |

| Benarroch-Gampelet al.,51 2013 | 2897 RFA, 977 EVLA | EVLA vs RF | GSV, SSV; no phlebectomy or sclerotherapy |

| Chi et al.,47 2011 | 360 EVLA | Only EVLA | GSV, SSV |

| Dzieciuchowicz et al.,30 2011 | 128 EVLA, 43 RF | EVLA (810 nm, 980 nm, 1470 nm) vs RF | GSV, SSV, intersaphenous vein, anterior accessory, large tributaries |

| Haqqani et al.,35 2011 | 73 RF | Only RF | GSV; some cases with phlebectomies |

| Harlander-Locke et al.,27 2013 | 1000 RF | Only RF | GSV and accessory (95%), SSV (5%); 355 concomitant stab phlebectomies |

| Harlander-Locke et al.,27 2013 | 76 RF | Only RF | SSV; 29 cases with phlebectomy |

| Jacobs et al.,52 2014 | 277 RF | Only RF | GSV, SSV; no concomitant procedures |

| Kane et al.,48 2014 | 528 EVLA | Only EVLA | GSV, SSV; 388 (74%) done along with stab phlebectomy |

| Knipp et al.,32 2008 | 460 EVLA | Only EVLA | Phlebectomy, perforator treatment as indicated |

| Lawrence et al.,26 2010 | 500 RF | Only RF | Phlebectomy as indicated |

| Lin et al.,33 2012 | 326, RF (169), EVLA (157) | EVLA vs RF | GSV, SSV; phlebectomy as indicated |

| Lomazzi et al.,53 2018 | 512, RF | Only RF | GSV, SSV |

| Lurie and Kistner,31 2013 | 120 RF | Only RF | GSV; phlebectomy, sclerotherapy as indicated |

| Marsh et al.,22 2010 | 2470 RF, 350 EVLA | EVLA vs RF | GSV; phlebectomy, perforator treatment as indicated |

| Puggioni et al.,20 2005 | 53 RF, 77 EVLA | EVLA vs RF | GSV, SSV; SEPS, phlebectomies, as indicated |

| Puggioni et al.,54 2009 | 293 RF | Only RF | GSV; SEPS, phlebectomies, as indicated |

| Rhee et al.,55 2013 | 482 EVLA, 396 RF | EVLA (810-nm) vs. RF | GSV or SSV ± anterior saphenous, duplicate saphenous vein, and posterior thigh communicating/extension veins |

| Ryer et al.,42 2016 | 842 RF | Only RF | GSV |

| Sadek et al.,56 2013 | 1267 EVLA, 2956 RF | EVLA jacket-tipped fiber, wavelength of 810 nm or 1470 nm and power at 14 W (810 nm) and at 6 W (1470 nm) vs RF | GSV or SSV; no vein stripping, saphenofemoral disconnections, or endoscopic or open perforator operations performed during this study |

| Sermsathanasawadi et al.,57 2016 | 97 RF | Only RF | GSV ± microphlebectomy (23 procedures [23.7%]) or ultrasound-guided foam sclerotherapy with 1% or 3% polidocanol (18 procedures [18.5%]) in the same setting of endovenous ablation |

| Skeik et al.,58 2013 | 146 RF or EVLA | RF and EVLA (patients with and without history of SVT) | GSV or SSV insufficiency with a history of SVT |

| Sufian et al.,24 2013 | 6707 RF | Only RF | GSV, accessory GSV, or SSV ± stab phlebectomies |

| Trip-Hoving et al.,59 2009 | 52 EVLA | Only EVLA | GSV or SSV |

| Zuniga et al.,60 2012 | 667 RF | Only RF (312 first-generation RF vs 355 second-generation RF) | GSV |

EVLA, Endovenous laser ablation; GSV, great saphenous vein; RF, radiofrequency; SEPS, subfascial endoscopic perforator surgery; SSV, small saphenous vein; SVT, superficial venous thrombosis.

The diameter of the GSV was found to be an important predictor of EHIT in several series by multivariable analysis applied to retrospective findings. Sermsathanasawadi et al.57 demonstrated higher risk for development of EHIT if the GSV diameter was >10 mm (odds ratio [OR], 5.97; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.161–30.716; P < .05). Harlander-Locke et al.27,49 found a GSV diameter >8 mm (P = .027; 95% CI, 3.66–9.89) and an SSV diameter >6 mm (P = .27) to increase the risk of EHIT. The lowest GSV diameter threshold involved in increased risk of EHIT was demonstrated by Kane et al.48 These authors found patients with GSV diameter >7.5 mm to be at a higher risk for development of EHIT (adjusted OR, 2.83; 95% CI, 1.18–6.77; P < .02).48 Puggioni et al.54 reported dilated proximal GSVs as a risk factor, but not a specific threshold (mean GSV diameter, 1.1 ± 0.39 mm vs 0.93 ± 0.27 mm; P < .01). Ryer et al.42 found a maximum GSV diameter of 11 mm to be associated with increased risk for development of EHIT compared with maximum GSV diameter of 7.8 mm (OR, 4.18; 95% CI, 1.47–11.84; P < .007).

Previous history of VTE (DVT or PE) or STP has also been investigated. In a study of 1000 vein ablations, Harlander-Locke et al.49 demonstrated that history of previous DVT is associated with EHIT (P = .041). However, Jacobs et al.52 analyzed 277 procedures and failed to find a correlation between EHIT and history of previous DVT. A previous history of STP was demonstrated by Puggioni et al.54 (P = .0135) and by Chi et al.47 (OR, 3.6; P = .002) to be an EHIT risk factor. Nonetheless, others have not found history of DVT or STP to be an EHIT risk factor. In a large study of 6707 vein ablations, Sufian et al.24 did not find history of DVT to correlate with EHIT (EHIT, 3.98%; non-EHIT, 4.73%; P = .065). In a dedicated series of vein ablations performed in 73 selected patients with history of STP, Skeik et al.58 did not find history of DVT or STP to be associated with EHIT. The Caprini score system, which uses several VTE risk factors, has been studied in patients undergoing thermal vein ablation to assess its EHIT development predictability.61 In a series of 519 vein ablations, this system was found to aid in identifying patients who are at higher risk for development of EHIT.55 A mean Caprini score of 6.9 ± 2.7 vs 5.0 ± 2.1 was associated with higher risk of EHIT (OR, 1.58; 95% CI, 1.24–2.01; P = .0002).55 However, another study of 97 vein ablations failed to show that a Caprini score >6 was associated with increased odds of EHIT on multivariable analysis.57

Male sex has also been reported as a risk factor by Rhee et al.55 (OR, 5.98; CI, 2.28–15.7l; P = .0003) and Jacobs et al.52 (OR, 4.91; P = .027). However, female sex was associated with EHIT in another study of 360 EVLAs by Chi et al.47 (OR, 2.6; P = .048). Nonetheless, sex was not found to be a significant EHIT risk factor in other series.33,48,52 Age has also been disputed as an EHIT risk factor. In a study of 360 consecutive EVLAs, it was demonstrated that age >66 years increases the odds for development of EHIT (OR, 4.1; P < .007).47 However, five other studies failed to prove any correlation between age and EHIT.27,48,51,52,55 Laser catheter tip location, its wavelength and energy delivered, and endovenous thermal ablation modality (RF vs EVLA) have not been found to increase the odds for development of EHIT.35,55,57,62 A list of risk factors reported in the literature selected is summarized in Table 7.

Table 7.

Reported risk factors associated with endothermal heat-induced thrombosis (EHIT) in the selected literature.

| References | EHIT risk factors |

|---|---|

| Benarroch-Gampel et al.,51 2013 | Increased risk in patients with venous stasis ulcersb |

| Chi et al.,47 2011 | Age >66 years, female sex, and history of SVTb |

| Haqqani et al.,35 2011 | Diameter of vein and position of the catheter tip did not correlate with risk of EHITa |

| Harlander-Locke et al.,27 2013 | Prior history of DVT and >8-mm GSV diameterb |

| Harlander-Locke et al.,27 2013 | Prior history of DVT and >6-mm SSV diameterb |

| Jacobs et al.,52 2014 | Prior history of DVT,a tobacco use,a treated vein (SSV > GSV),a factor V Leiden,b male sexb |

| Kane et al.,48 2014 | GSV or SSV diameter ≥7.5 mmb |

| Knipp et el,32 2008 | Concomitant phlebectomy or perforator interruptiona |

| Lawrence et al.,26 2010 | Prior history of DVT and >8-mm GSV diameterb |

| Lin et al.,33 2012 | Valvular incompetence at the SFJ,a >8-mm GSV diametera |

| Lomazzi et al.,53 2018 | Long distance between the SFJ and the EV, large average and maximum GSV diameter, and large SFJ diameter |

| Lurie and Kistner,31 2013 | Increased D-dimer concentration with normal CRP level,a GSV diameter >7.3 mma |

| Marsh et al.,22 2010 | Concomitant SSV RF and incompetent PV occlusiona |

| Puggioni et al.,20 2005 | Older patients (>50 years of age)a |

| Puggioni et al.,54 2009 | Prior history of SVT,b larger GSV diameter (1.1 ± 0.39 mm),b EVLA catheter temperature,a concomitant venous operationsa |

| Rhee et al.,55 2013 | Female sex,a prior history of DVT or phlebitis, mean Caprini score (6.9 ± 2.7) |

| Ryer et al.,42 2016 | Maximum GSV diameter (7.8 mm)b |

| Sadek et al.,56 2013 | Location of catheter tip >2.5 cm from SFJ (trends, P = .066)a |

| Sermsathanasawadi et al.,57 2016 | GSV diameter >10 mm,a operative time >40 minutes |

| Skeik et al.,58 2013 | Prior history of VTEa or history of thrombophiliaa was not associated with EHIT |

| Sufian et al.,24 2013 | Large vein diameter (10 mm),a male sex,a older patients,a multiple phlebectomiesa |

| Zuniga et al.,60 2012 | Type of RF generation catheter (increased risk with ClosurePlus, first generation, vs ClosureFast, second generation) |

CRP, C-reactive protein; DVT, deep venous thrombosis; EV, epigastric vein; EVLA, endovenous laser ablation; GSV, great saphenous vein; PV, perforator vein; RF, radiofrequency; SFJ, saphenofemoral junction; SSV, small saphenous vein; SVT, superficial venous thrombosis; VTE, venous thromboembolism.

aUnivariate analysis.

bMultivariate analysis.

Prevention

Guideline 2.2: Prevention of EHIT with chemical prophylaxis

The use of chemical prophylaxis for prevention of EHIT should be tailored to the patient after an assessment of the risks, benefits, and alternatives. [GRADE – 2; LEVEL OF EVIDENCE – C]

Guideline 2.3: Prevention of EHIT with mechanical prophylaxis

The use of mechanical prophylaxis for prevention of EHIT should be tailored to the patient after an assessment of the risks, benefits, and alternatives. [GRADE – 2; LEVEL OF EVIDENCE – C]

Guideline 2.4: Prevention of EHIT by increasing ablation distance

There is a trend toward decreased EHIT when ablation is initiated >2.5 cm from the saphenofemoral (GSV) or saphenopopliteal (SSV) junction. [GRADE – 2; LEVEL OF EVIDENCE – C]

Chemical and mechanical methods for prophylaxis of VTE before or after endovenous ablation have been scarcely described. All data on EHIT prevention are based on observational clinical studies subjected to retrospective review.

Perioperative use of chemical venous thromboembolic prophylaxis was reported in four series.22,32,36,55 The use of low-molecular-weight heparin was used in two of them.32,33 A third series developed a prevention DVT prophylaxis protocol including unfractionated heparin or enoxaparin.32 Rhee et al.55 used enoxaparin in patients who were at higher risk of thrombosis, such as those with prior thrombotic episodes including STP, family history, or known hypercoagulable state. Marsh et al.22 routinely used one dose of 4000 units of enoxaparin unless the patient was already taking warfarin. For patients who were chronically taking warfarin, enoxaparin was administered immediately postoperatively for EVLA and intraoperatively for RFA.22 In this study with 2820 patients undergoing RFA and EVLA, all 7 patients who were diagnosed with EHIT received low-molecular-weight heparin.22 Knipp et al.32 instituted a DVT prophylaxis protocol based on a DVT risk factors predictive system. Patients with two risk factors did not receive any chemical prophylaxis. Patients with three or four risk factors received a single dose of 5000 units of unfractionated heparin or 30 mg of enoxaparin within 60 minutes of the operation. Those with five or more risk factors received a perioperative prophylactic dose of unfractionated heparin or enoxaparin along with enoxaparin for 1 week postoperatively. Despite the institution of a DVT prophylaxis protocol before endovenous ablation, no difference on DVT rate after endovenous ablation was demonstrated.

Similar rates of EHIT and DVT were demonstrated despite the use of chemical DVT prophylaxis.32 Haqqani et al.35 reported the use of subcutaneous injection of unfractionated heparin in 73 patients undergoing RFA varying from 3000 to 5000 units perioperatively. Neither of these three series reported a lower incidence of EHIT due to use of chemical prophylaxis.

The use of elastic compression or compression stockings after endovenous ablation was described in 15 series, and these data were analyzed.22,27,32,33,46–49,52,55–57,59,60,63 Ten series reported compression bandages placed right after the procedure.12,27,32,35,48,49,52,54,57,60 Of those, two reported that compression bandages were left on for 24 hours and four others for a total of 48 hours after the procedure.12,32,35,54,57,60 No specific duration of postoperative elastic compression bandage was described by the other four series.27,48,49,52 Five studies prescribed compression stockings immediately after the procedure.22,35,46,47,56 The compression grading prescribed included both 20 to 30 mm Hg and 30 to 40 mm Hg. No correlation between the use of elastic bandage or compression stockings postoperatively and EHIT was stated in any of the studies included.

In an evaluation of endothermal ablation using laser and radiofrequency for the treatment of GSV and SSV reflux, there was a trend toward a decreased rate of EHIT when ablation was initiated >2.5 cm from the deep vein junction.56 Additional techniques that may prevent EHIT in large saphenous veins found to be beneficial by the authors include an extreme Trendelenburg position as well as abundant tumescence, particularly at the saphenofemoral junction. Data on such techniques remain forthcoming.

Treatment of EHIT

The management of EHIT remains controversial in light of its presumed benign natural history compared with conventional DVT. Specifically, patients are often asymptomatic, and the progression to PE is rarely reported. In addition, there is no conclusive evidence to support the theory that treating EHIT reduces the incidence of PE. As such, whereas early series recognizing EHIT as a complication of thermal ablation reported on cases of inferior vena cava filter placement and saphenofemoral thrombectomy with ligation, a far more conservative approach has since been widely adopted.16,18,22 The low incidence of EHIT makes it challenging to conduct a prospective randomized trial. Therefore, treatment recommendations are based primarily on retrospective institutional series, but they are also guided by the surgeon’s preference and anecdotal experience. Two EHIT classification schemes are present in the literature, the Kabnick classification23 and the Lawrence classification.27 There is also a proposed modification for the SSV. Also of note, a majority of the reports were produced before the widespread use of direct oral anticoagulants, and this evolution in treatment should also be taken into account in this consensus statement. Last, as a method of attempting to reduce the number of EHITs from the outset, Sadek et al.56 demonstrated that it may be beneficial to increase the ablation distance to >2.5 cm from the deep venous junction.

Guideline 3.1: Classification system

We suggest the stratification of treatment based on an accepted EHIT classification system. [BEST PRACTICE]

Therefore, the recommendations for antiplatelet and anticoagulant therapies have been tempered for the treatment of EHIT. This section on classification of EHIT delineates the combined AVF EHIT classification system that forms the basis for the treatment recommendations.

EHIT after ablation of the GSV

Guideline 3.2: Treatment for EHIT I

We suggest no treatment or surveillance for EHIT I. [GRADE – 2; LEVEL OF EVIDENCE – C]

Guideline 3.3: Treatment for EHIT II

We suggest no treatment of EHIT II but do suggest weekly surveillance until thrombus resolution. In high-risk patients, consideration may be given to antiplatelet therapy vs prophylactic or therapeutic anticoagulation with weekly surveillance. Treatment would cease after thrombus retraction or resolution to the saphenofemoral (GSV) or saphenopopliteal (SSV) junction. [GRADE – 2; LEVEL OF EVIDENCE – C]

Guideline 3.4: Treatment for EHIT III

We suggest treatment with therapeutic anticoagulation for EHIT III, weekly surveillance, and cessation of treatment after thrombus retraction or resolution to the saphenofemoral (GSV) or saphenopopliteal (SSV) junction. [GRADE – 1; LEVEL OF EVIDENCE – B]

Guideline 3.5: Treatment for EHIT IV

We suggest that treatment should be individualized, taking into account the risks and benefits to the patient. Reference may be made to the Chest guidelines for the treatment of DVT. [GRADE – 1; LEVEL OF EVIDENCE – A]

The suggested algorithm was compiled from the existing literature as well as from expert consensus and anecdotal experience. The following practice recommendations for the treatment of EHIT after ablation of the GSV, as classified by the AVF EHIT classification system, are all graded 2C, with a weak recommendation based on very low quality of evidence.16,18,20,22,24,26,27,31,33,48,52,54,56,57,63,64

Class I EHIT offers a mainly benign natural history, and existing data confirm that no specific treatment is warranted. Class Ia EHIT (thrombus peripheral to the superficial epigastric vein) warrants no additional surveillance (clinical or duplex ultrasound). Patients who develop class Ib EHIT (central to the epigastric vein, up to and including the deep vein junction) may be considered for individualized treatment and surveillance. Several authors recommend antiplatelet therapy for such cases of EHIT, noting no cases of thrombus propagation after treatment.65,66 Others support simply observation alone. Lawrence et al.26 previously reported a 2.6% incidence of EHIT after 500 RFAs, of which 21 cases were noted to be flush with the saphenofemoral junction. Half of these cases were anticoagulated, the other half untreated; there were no cases of thrombus propagation, and all thrombi ultimately retracted. The authors recommend an individualized approach to treatment of these cases that specifically considers patient risk factors for thromboembolism. In contrast, Sufian et al.24 reported a 3% incidence of EHIT after thermal ablation of 4906 GSVs, of which 100 cases were class I. Without treatment and with observation, they identified six cases of thrombus propagation into the femoral vein classified as class II (n = 3) and class III (n = 3). Those patients qualified as class III were treated with anticoagulation, and ultimately all thrombi were resolved by 4 weeks.

Class II EHIT remains controversial, and in fact many institutional series report inconsistent treatment of these thrombi that propagate into the adjacent deep (femoral) vein but comprise <50% of the deep vein lumen. Some authors have supported routine anticoagulation for this complication, most frequently in the form of low-molecular-weight heparin, ultimately noting complete thrombus resolution.35,56 Proponents of anticoagulation suggest that treatment duration should be dictated by concurrent weekly surveillance venous duplex ultrasound such that anticoagulation may be discontinued once the thrombus has retracted to the saphenofemoral junction (flush with the ostium of the GSV). Kane et al.48 anticoagulated 6 of 19 patients diagnosed with AVF class II EHIT. All patients demonstrated complete thrombus resolution by 7 weeks. A more contemporary report supports the use of antiplatelet therapy with 7 to 10 days of aspirin for class II EHIT, acknowledging a 3% incidence of thrombus propagation with this approach that was clinically insignificant (thrombus remained class II). Sufian et al.24 similarly reported on 61 cases of class II EHIT complicating 4906 GSV thermal ablations treated with either observation or antiplatelet therapy. These authors noted thrombus progression in three patients to class III EHIT, for which therapeutic anticoagulation was prescribed. These same authors also reported on the single documented case of PE resulting directly from class II EHIT; the thrombus was noted to “disappear” during ultrasound evaluation, and the patient was subsequently diagnosed radiographically with symptomatic PE.28 The treatment of patients with class II EHIT warrants further investigation with a prospective study.

Most authors support a finite (“short”) course of therapeutic anticoagulation for class III EHIT, thrombus propagation into the adjacent deep (femoral) vein and comprising >50% of the deep vein lumen, until weekly duplex ultrasound supports thrombus retraction or resolution to the saphenofemoral junction (flush with the ostium of the GSV). There are no data to corroborate altering management for the presence of a floating tail of thrombus; however, there may be a consideration for individualizing and extending the duration of anticoagulation in such cases. 16,18,22,66

Class IV EHIT, occlusive DVT contiguous with the treated superficial vein, generally warrants treatment consistent with VTE guidelines. These patients require 3 months of therapeutic anticoagulation for provoked VTE, per the Chest guidelines. We suggest that treatment should be individualized, taking into account the patient’s risk factors and bleeding risk, and reference may be made to the Chest guidelines for the treatment of a provoked VTE.44

EHIT after ablation of the SSV

Guideline 4.1: Management of EHIT for the SSV

We suggest that management and treatment for EHIT as it relates to the SSV parallel those for the GSV. [GRADE – 2; LEVEL OF EVIDENCE – C]

In 2013, Harlander Locke et al.27 proposed a four-tier classification system and treatment algorithm for EHIT associated with the saphenopopliteal junction after ablation of the SSV. These authors reported retrospectively on 76 consecutive patients treated with SSV ablation. The authors identified 12 cases of EHIT; more specifically, 13% of patients demonstrated SSV closure flush or <1 mm with the popliteal vein, and 3% of patients demonstrated thrombus extension into the popliteal vein (n = 2). There were no cases of occlusive popliteal venous thrombosis. The patients who demonstrated SSV closure were managed conservatively with interim duplex ultrasound at 1 week, whereas the patients who demonstrated thrombus extension received low-molecular-weight heparin with weekly surveillance and cessation of anticoagulation when the thrombus retracted or resolved. With this algorithm, there were no cases of thrombus extension or further VTE or PE.

Gibson et al.64 reported perhaps the largest incidence (5.7%) of EHIT after laser ablation of the SSV. Specifically, 12 patients were diagnosed with nonocclusive thrombus extension into the popliteal vein, the treatment of which was “left to the discretion of the surgeon.” As such, nine patients received anticoagulation, two patients received aspirin, and one patient received simply surveillance. There was no thrombus extension and no PE noted in any patient during the study period. Additional series support a relatively benign natural history for EHIT after SSV ablation without clear thrombus extension or PE.48,50

Discussion

The literature available on EHIT is largely based on retrospective studies, small case series, and case reports. Therefore, the quality of evidence on prevention and risk factors associated with EHIT is very low. The design of these studies reflects the difficulties of gathering a substantial amount of data to justify a prospective, randomized study. The main reason for it is the very low incidence of EHIT in the vast cohort of patients treated with endovenous ablation despite some reported high incidence of thrombotic complications in the literature. The incidence of DVT after EVLA has been described to be as high as 16%, although this manuscript was developed before the widespread concept of EHIT.16 Similarly, the incidence of EHIT has been reported to be as high as 12%.67 These are relatively small cohorts analyzed retrospectively. A randomized double-blind controlled trial comparing radiofrequency and laser vein ablation reported no postprocedure thrombotic complications such as DVT.30 Aside from some outlier series, the incidence of EHIT has been demonstrated to be often lower than 3%.35,51

Risks factors involved in EHIT have been inconsistently reported. The very low number of events to be correlated with a specific predisposing factor precludes any meaningful conclusions because of lack of statistical power. Currently, there are no EHIT reporting standards to guide researchers in their studies of potential predisposing factors related to EHIT. A variety of case series with different variables and analysis, such as the size of the vein to be ablated or the distance of the device tip from the saphenofemoral junction, are the norm. Some authors believe a saphenous vein diameter >10 mm would increase risks of EHIT, but others report a diameter as low as 8 or 9 mm as the cutoff for this complication.

The controversy is further accentuated when other factors, such as concomitant microphlebectomies or history of STP, are considered. There are no clear data to suggest that the number and site of phlebectomies increase the risk of EHIT. History of VTE, thrombophilia, or STP could potentially increase the risk of further VTE and EHIT after endothermal ablation. Nonetheless, there is no evidence to confirm or to deny such a concept. This is also true for sex and age of patients undergoing endothermal ablation. We believe that knowing the reported EHIT risk factors would increase attention to surveillance.

It is unclear whether any VTE prophylaxis method that has been used before and after ablation is effective. Scattered experience showing the use of chemical prophylaxis has been published. We were unable to find any definitive protocol or risk stratification as to whether prophylaxis must be used. However, there are no data showing adverse events, such as bleeding or ecchymosis, in patients who received chemical VTE prophylaxis. The use of elastic compression dressings or stockings is also randomly described throughout the literature. The duration of leg compression can vary from a few days to several weeks from the initial procedure. There is no protective correlation between compression stockings and EHIT.

A multicenter, national registry is a potential effective strategy to standardize research while gathering data from thousands of endothermal ablation procedures nationwide. This would help determine whether any surveillance studies are needed because it remains unclear if a routine postprocedural duplex ultrasound scan is a cost-saving strategy.23,41,42 There have been no studies reporting the costs related to postintervention duplex ultrasound and its effectiveness on outcomes. The most common reason to obtain a duplex ultrasound scan after endovenous thermal ablation is not based on known risk factors or technique used. Routine duplex ultrasound evaluation appears to be done to document the absence of EHIT or DVT to aid in decision-making in regard to early treatment with anticoagulation to prevent PE. A substantial component of this practice is related to the fear of medical-legal implications of an untreated EHIT and potential death related to PE.63,68

Conclusions

There is very low quality evidence on risk factors of EHIT to determine any pattern for prevention at this time. Prophylaxis has been randomly used in a few studies with no consistency. A nationwide, multicenter, prospective registry is warranted to address questions regarding risks factors of this potentially fatal endovenous ablation complication and to assist in creating an effective, evidence-based protocol for prevention and postprocedure surveillance.

Conclusions

The AVF guidelines committee in collaboration with the Society for Vascular Surgery has set forth this document as a consensus statement for EHIT. The goal of this document is to review the current evidence and to standardize the data. The topics for review include definition, classification, risk factors and prevention, and treatment.

This document highlights the recognition that EHIT is unique compared with DVT. EHIT refers to the postprocedural propagation of thrombus after an endothermal ablation (eg, RFA or EVLA). The definition for EHIT is based on a specific relationship between the superficial vein that is being treated and the contiguous deep vein. EHIT exhibits a variable presentation, and therefore a single definition is limited in its ability to characterize this entity.

The classification of EHIT represents the natural extension of the definition for EHIT. The Kabnick and Lawrence classifications have been used most commonly. All classification schemes have served the purpose of recognizing EHIT as a unique clinical phenomenon and of standardizing the reporting of data. The AVF EHIT classification serves to unify the available classification schemes based on the evidence. Because of the strong similarities between the different classification systems, they may be combined while maintaining the same clinically relevant end points. The AVF EHIT classification allows further standardization in reporting of the data for both clinical and research purposes. Moreover, the similarities to the original guidelines allow cross-referencing and aggregation of data with the body of literature that exists currently. Last, unifying the classification of EHIT sets the stage for the evolution of the definition to include the nonthermal entities that have already been proposed.

Multiple studies have evaluated the risk factors and, by extension, the modes of prevention for EHIT. In general, the evidence for risk factors and modes of prevention was limited and lacked reproducibility. Some of the risk factors identified included diameter, age, and a history of thromboembolic disease, among other factors. With regard to prevention of EHIT, there were no significant findings with the use of chemical prophylaxis, the use of compression, or the distance of ablation from the deep vein junction, although there was a trend toward a decreased rate of EHIT II when treatment was initiated >2.5 cm from the deep vein junction.

Originally, the treatment of DVT was extrapolated to the management of post-endothermal ablation thrombotic events. Once EHIT was recognized as being unique and was categorized and evidence accrued, the management for EHIT evolved. Specifically, there was a recognition that the majority of postprocedural thrombotic events did not propagate into the adjacent deep vein and would have been categorized as an AVF EHIT I. The extension of an EHIT I to the level of the superficial epigastric vein or to the saphenofemoral junction remains of interest for research purposes, and this distinction remains in the AVF EHIT classification. Thrombus extension into the adjacent deep vein is the most recognized potentially clinically significant entity. This may be categorized as an AVF EHIT II or III, with most reports demonstrating EHIT II as the majority of disease.

The literature suggests that EHIT II as a clinical entity is benign; however, there are case reports of thrombus propagation and pulmonary emboli. The same is likely to be true for EHIT III, although the evidence in the literature is sparse. The guidelines committee consensus is that surveillance duplex ultrasound should be considered for these clinical entities. Treatment should be tailored to the patient, taking the risks and benefits into account. Ongoing data collection from prospective studies and registries will allow refinement of diagnosis and treatment protocols.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: L.S.K. and E.D.D are consultants for AngioDynamics.

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

The editors and reviewers of this article have no relevant financial relationships to disclose per the Journal policy that requires reviewers to decline review of any manuscript for which they may have a conflict of interest.

Author contributions

Conception and design: LK, MS, HB, DC, ED, PL, RM.

Analysis and interpretation: LK, MS, HB, AH, BL, PL, RM.

Data collection: LK, MS, HB, DC, PL, RM, AP.

Writing the article: LK, MS, HB, DC, PL, RM, AP.

Critical revision of the article: LK, MS, HB, DC, ED, AH, BL, PL, RM.

Final approval of the article: LK, MS, HB, DC, ED, AH, BL, PL, RM, AP.

Statistical analysis: Not applicable.

Obtained funding: Not applicable.

Overall responsibility: LK.

References

- 1.Heit JA, Silverstein MD, Mohr DN, Petterson TM, Lohse CM, O'Fallon WM, et al. The epidemiology of venous thromboembolism in the community. Thromb Haemost 2001; 86: 452–463. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rabe E, Guex JJ, Puskas A, Scuderi A, Fernandez Quesada F; VCP Coordinators. Epidemiology of chronic venous disorders in geographically diverse populations: results from the Vein Consult Program. Int Angiol 2012; 31: 105–115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gloviczki P, Comerota AJ, Dalsing MC, Eklof BG, Gillespie DL, Gloviczki ML, et al. The care of patients with varicose veins and associated chronic venous diseases: clinical practice guidelines of the Society for Vascular Surgery and the American Venous Forum. J Vasc Surg 2011; 53(Suppl):2S–48S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pyne JM, Sieber WJ, David K, Kaplan RM, Hyman Rapaport M, Keith Williams D. Use of the Quality of Well-Being self-administered version (QWB-SA) in assessing health-related quality of life in depressed patients. J Affect Disord 2003; 76: 237–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smith JJ, Garratt AM, Guest M, Greenhalgh RM, Davies AH. Evaluating and improving health-related quality of life in patients with varicose veins. J Vasc Surg 1999; 30: 710–719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smith JJ, Guest MG, Greenhalgh RM, Davies AH. Measuring the quality of life in patients with venous ulcers. J Vasc Surg 2000; 31: 642–649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Korn P, Patel ST, Heller JA, Deitch JS, Krishnasastry KV, Bush HL, et al. Why insurers should reimburse for compression stockings in patients with chronic venous stasis. J Vasc Surg 2002; 35: 950–957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mundy L, Merlin TL, Fitridge RA, Hiller JE. Systematic review of endovenous laser treatment for varicose veins. Br J Surg 2005; 92: 1189–1194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hoggan BL, Cameron AL, Maddern GJ. Systematic review of endovenous laser therapy versus surgery for the treatment of saphenous varicose veins. Ann Vasc Surg 2009; 23: 277–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Luebke T, Gawenda M, Heckenkamp J, Brunkwall J. Meta-analysis of endovenous radiofrequency obliteration of the great saphenous vein in primary varicosis. J Endovasc Ther 2008; 15: 213–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Min RJ, Zimmet SE, Isaacs MN, Forrestal MD. Endovenous laser treatment of the incompetent greater saphenous vein. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2001; 12: 1167–1171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lurie F, Creton D, Eklof B, Kabnick LS, Kistner RL, Pichot O, et al. Prospective randomized study of endovenous radiofrequency obliteration (closure procedure) versus ligation and stripping in a selected patient population (EVOLVeS Study). J Vasc Surg 2003; 38: 207–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leopardi D, Hoggan BL, Fitridge RA, Woodruff PW, Maddern GJ. Systematic review of treatments for varicose veins. Ann Vasc Surg 2009; 23: 264–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Murad MH, Coto-Yglesias F, Zumaeta-Garcia M, Elamin MB, Duggirala MK, Erwin PJ, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the treatments of varicose veins. J Vasc Surg 2011; 53(Suppl):49S–65S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Meissner MH, Gloviczki P, Bergan J, Kistner RL, Morrison N, Pannier F, et al. Primary chronic venous disorders. J Vasc Surg 2007; 46(Suppl S):54S–67S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hingorani AP, Ascher E, Markevich N, Schutzer RW, Kallakuri S, et al. Deep venous thrombosis after radiofrequency ablation of greater saphenous vein: a word of caution. J Vasc Surg 2004; 40: 500–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chandler JG, Pichot O, Sessa C, Schuller-Petrović S, Osse FJ, Bergan JJ. Defining the role of extended saphenofemoral junction ligation: a prospective comparative study. J Vasc Surg 2000; 32: 941–953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mozes G, Kalra M, Carmo M, Swenson L, Gloviczki P. Extension of saphenous thrombus into the femoral vein: a potential complication of new endovenous ablation techniques. J Vasc Surg 2005; 41: 130–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Merchant RF, DePalma RG, Kabnick LS. Endovascular obliteration of saphenous reflux: a multicenter study. J Vasc Surg 2002; 35: 1190–1196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Puggioni A, Kalra M, Carmo M, Mozes G, Gloviczki P. Endovenous laser therapy and radiofrequency ablation of the great saphenous vein: analysis of early efficacy and complications. J Vasc Surg 2005; 42: 488–493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wagner WH, Levin PM, Cossman DV, Lauterbach SR, Cohen JL, Farber A. Early experience with radiofrequency ablation of the greater saphenous vein. Ann Vasc Surg 2004; 18: 42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marsh P, Price BA, Holdstock J, Harrison C, Whiteley MS. Deep vein thrombosis (DVT) after venous thermoablation techniques: rates of endovenous heat-induced thrombosis (EHIT) and classical DVT after radiofrequency and endovenous laser ablation in a single centre. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2010; 40: 521–527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kabnick LS, Ombrellino M, Agis H, Mortiz M, Almeida J, Baccaglini U, et al. Endovenous heat induced thrombosis (EHIT) at the superficial deep venous junction: a new post-treatment clinical entity, classification and potential treatment strategies. Presented at the Eighteenth Annual Meeting of the American Venous Forum; Miami, Fla; February 22–26, 2006.

- 24.Sufian S, Arnez A, Labropoulos N, Lakhanpal S. Incidence, progression, and risk factors for endovenous heat induced thrombosis after radiofrequency ablation. J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord 2013; 1: 159–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ayo D, Blumberg SN, Rockman CR, Sadek M, Cayne N, Adelman M, et al. Compression vs no compression after endovenous ablation of the great saphenous vein: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Vasc Surg 2016; 34: 20–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lawrence PF, Chandra A, Wu M, Rigberg D, DeRubertis B, Gelabert H, et al. Classification of proximal endovenous closure levels and treatment algorithm. J Vasc Surg 2010; 52: 388–393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Harlander-Locke M, Jimenez JC, Lawrence PF, Derubertis BG, Rigberg DA, Gelabert HA, et al. Management of endovenous heat-induced thrombus using a classification system and treatment algorithm following segmental thermal ablation of the small saphenous vein. J Vasc Surg 2013; 58: 427–431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sufian S, Arnez A, Lakhanpal S. Case of the disappearing heat-induced thrombus causing pulmonary embolism during ultrasound evaluation. J Vasc Surg 2012; 55: 529–531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shi H, Liu X, Lu M, Lu X, Jiang M, Yin M. The effect of endovenous laser ablation of incompetent perforating veins and the great saphenous vein in patients with primary venous disease. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2015; 49: 574–580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dzieciuchowicz L, Krasiński Z, Gabriel M, Espinosa G. A prospective comparison of four methods of endovenous thermal ablation. Pol Przegl Chir 2011; 83: 597–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lurie F, Kistner RL. Pretreatment elevated D-dimer levels without systemic inflammatory response are associated with thrombotic complications of thermal ablation of the great saphenous vein. J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord 2013; 1: 154–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Knipp BS, Blackburn SA, Bloom JR, Fellows E, Laforge W, Pfeifer JR, et al. Endovenous laser ablation: venous outcomes and thrombotic complications are independent of the presence of deep venous insufficiency. J Vasc Surg 2008; 48: 1538–1545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lin JC, Peterson EL, Rivera ML, Smith JJ, Weaver MR. Vein mapping prior to endovenous catheter ablation of the great saphenous vein predicts risk of endovenous heat-induced thrombosis. Vasc Endovascular Surg 2012; 46: 378–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Santin BJ, Lohr JM, Panke TW, Neville PM, Felinski MM, Kuhn BA, et al. Venous duplex and pathologic differences in thrombus characteristics between de novo deep vein thrombi and endovenous heat-induced thrombi. J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord 2015; 3: 184–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Haqqani OP, Vasiliu C, O'Donnell TF, Iafrati MD. Great saphenous vein patency and endovenous heat-induced thrombosis after endovenous thermal ablation with modified catheter tip positioning. J Vasc Surg 2011; 54(Suppl):10S–7S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schwarz T, von Hodenberg E, Furtwängler C, Rastan A, Zeller T, Neumann FJ. Endovenous laser ablation of varicose veins with the 1470-nm diode laser. J Vasc Surg 2010; 51: 1474–1478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kwak JH, Min SI, Kim SY, Han A, Choi C, Ahn S, et al. Delayed presentation of endovenous heat-induced thrombosis treated by thrombolysis and subsequent open thrombectomy. Vasc Specialist Int 2016; 32: 72–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rasmussen LH, Lawaetz M, Bjoern L, Vennits B, Blemiings A, Eklof B. Randomized clinical trial comparing endovenous laser ablation, radiofrequency ablation, foam sclerotherapy and surgical stripping for great saphenous varicose veins. Br J Surg 2011; 98: 1079–1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Passariello F. Post ablation superficial thrombus extension (PASTE) as a consequence of endovenous ablation. An up-to-date review. Rev Vasc Med 2014; 2: 62–66. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Andrews J, Guyatt G, Oxman AD, Alderson P, Dahm P, Falck-Ytter Y, et al. GRADE guidelines: 14. Going from evidence to recommendations: the significance and presentation of recommendations. J Clin Epidemiol 2013; 66: 719–725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Suarez L, Tangney E, O'Donnell TF, Iafrati MD. Cost analysis and implications of routine deep venous thrombosis duplex ultrasound scanning after endovenous ablation. J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord 2017; 5: 126–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ryer EJ, Elmore JR, Garvin RP, Cindric MC, Dove JT, Kekulawela S, et al. Value of delayed duplex ultrasound assessment after endothermal ablation of the great saphenous vein. J Vasc Surg 2016; 64: 446–51.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jones RT, Kabnick LS. Perioperative duplex ultrasound following endothermal ablation of the saphenous vein: is it worthless? J Invasive Cardiol 2014; 26: 548–550. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kearon C, Akl EA, Ornelas J, Blaivas A, Jimenez D, Bounameaux H, et al. Antithrombotic Therapy for VTE Disease: CHEST Guideline and Expert Panel Report. Chest 2016; 149: 315–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kerver AL, van der Ham AC, Theeuwes HP, Eilers PH, Poublon AR, Kerver AJ, et al. The surgical anatomy of the small saphenous vein and adjacent nerves in relation to endovenous thermal ablation. J Vasc Surg 2012; 56: 181–188. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2010; 40: 521–527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ahn S, Jung IM, Chung JK, Lee T. Changes in saphenous vein stump and low incidence of endovenous heat-induced thrombosis after radiofrequency ablation of great saphenous vein incompetence. Dermatol Surg 2016; 42: 515–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chi YW, Ali L, Woods TC. Clinical risk factors to predict deep venous thrombosis post endovenous laser ablation of saphenous veins. Vasc Med 2011; 16: 235–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kane K, Fisher T, Bennett M, Hicks T, Grimsley B, Gable D, et al. The incidence and outcome of endothermal heat-induced thrombosis after endovenous laser ablation. Ann Vasc Surg 2014; 28: 1744–1750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Harlander-Locke M, Jimenez JC, Lawrence PF, Derubertis BG, Rigberg DA, Gelabert HA. Endovenous ablation with concomitant phlebectomy is a safe and effective method of treatment for symptomatic patients with axial reflux and large incompetent tributaries. J Vasc Surg 2013; 58: 166–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Monahan TS, Belek K, Sarkar R. Results of radiofrequency ablation of the small saphenous vein in the supine position. Vasc Endovascular Surg 2012; 46: 40–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Benarroch-Gampel J, Sheffield KM, Boyd CA, Riall TS, Killewich LA. Analysis of venous thromboembolic events after saphenous ablation. J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord 2013; 1: 26–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jacobs CE, Pinzon MM, Orozco J, Hunt PJ, Rivera A, McCarthy WJ. Deep venous thrombosis after saphenous endovenous radiofrequency ablation: is it predictable? Ann Vasc Surg 2014; 28: 679–685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]