Abstract

Accurately quantifying the progression of diabetic peripheral neuropathy is key to identify individuals who will progress to foot ulceration and to power clinical intervention trials. We have undertaken detailed neuropathy phenotyping to assess the longitudinal utility of different measures of neuropathy in patients with diabetes. Nineteen patients with diabetes (age 52.5 ± 14.7 years, duration of diabetes 26.0 ± 13.8 years) and 19 healthy controls underwent assessment of symptoms and signs of neuropathy, quantitative sensory testing, autonomic nerve function, neurophysiology, intra-epidermal nerve fibre density (IENFD) and corneal confocal microscopy (CCM) to quantify corneal nerve fibre density (CNFD), branch density (CNBD) and fibre length (CNFL). Mean follow-up was 6.5 years. Glycated haemoglobin (p = 0.04), low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol (LDL-C) (p = 0.0009) and urinary albumin creatinine ratio (p < 0.0001) improved. Neuropathy symptom profile (p = 0.03), neuropathy disability score (p = 0.04), vibration perception threshold (p = 0.02), cold perception threshold (p = 0.006), CNFD (p = 0.03), CNBD (p < 0.0001), CNFL (p < 0.0001), IENFD (p = 0.04), sural (p = 0.02) and peroneal motor nerve conduction velocity (p = 0.03) deteriorated significantly. Change (∆) in CNFL correlated with ∆CPT (p = 0.006) and ∆Expiration/Inspiration ratio (p = 0.002) and ∆IENFD correlated with ∆CNFD (p = 0.005), ∆CNBD (p = 0.02) and ∆CNFL (p = 0.01). This study shows worsening of diabetic neuropathy across a range of neuropathy measures, especially CCM, despite an improvement in HbA1c and LDL-C. It further supports the utility of CCM as a rapid, non-invasive surrogate measure of diabetic neuropathy.

Subject terms: Diabetes, Diabetes complications

Introduction

The natural history of diabetic peripheral neuropathy (DPN) is poorly defined with limited studies assessing progression of neuropathy1. As a consequence, clinical trials of disease modifying therapies in patients with diabetic neuropathy have not been able to identify the optimal neuropathy end points to adequately assess progression or improvement in DPN2. Indeed, whilst the DCCT in patients with T1DM showed that intensive glycaemic control reduced the incidence of clinical DPN and nerve conduction abnormalities by 60%3; in patients with T2DM, the UKPDS4 and VA-CSDM trial5 reported no effect on DPN and cardiac autonomic neuropathy and whilst the Kumamoto study6 showed a prevention of nerve conduction slowing, the ACCORD trial7 showed no effect on VPT over 6-years.

Quantitative sensory testing (QST) is relatively easy to perform but has limited reproducibility and a high degree of subjectivity8. Nerve conduction studies (NCS) are the established ‘gold standard’ for evaluating DPN but require standardization in a clinical trial and cannot evaluate small fibres9. Whilst small nerve fibre damage and repair can be identified by performing a skin biopsy and quantifying intra-epidermal nerve fibre density (IENFD), it is invasive and requires expertise10–12. Other techniques for the assessment of small nerve fibres include microneurography, Laser doppler image flare (LDIflare), nociceptive-evoked potentials and electrochemical skin conductance, but have considerable variability and are not routinely available13,14. Corneal confocal microscopy (CCM) is a rapid non-invasive imaging technique for the quantitative assessment of small fibre damage. Several studies have shown that it has good diagnostic utility for sub-clinical DPN, predicts incident DPN15,16 and correlates with other measures of neuropathy16. Furthermore, automated quantification of corneal nerve parameters allows rapid, unbiased and objective assessment of small fibre damage17 with comparable diagnostic capability to IENFD18,19.

Longitudinal studies of patients with diabetic neuropathy have been of relatively short duration and lacked detailed neuropathy phenotyping20–23. In this study we compare the change in CCM and IENFD with symptoms, signs, QST, autonomic function and neurophysiology over 6.5 years in a cohort of patients with diabetes.

Results

Clinical and metabolic assessment (Tables 1, 2)

Table 1.

Clinical and neuropathy parameters in control subjects and patients at baseline.

| Variable | Controls (n = 19) | Patients (Baseline) (n = 19) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical and laboratory parameters | |||

| Age (years) | 47.4 ± 14.2 | 52.5 ± 14.7 | 0.20 |

| Duration of diabetes (years) | NA | 26.0 ± 13.8 | NA |

| Weight (kg) | 80.7 ± 18.0 | 82.0 ± 19.8 | 0.9 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 27.5 ± 4.0 | 29.0 ± 5.7 | 0.50 |

| BP (mmHg) | 131 ± 23/74.0 ± 11.0 | 132 ± 21/ 71 ± 8 | 0.90/0.50 |

| HbA1c (mmol/mol) | 37.5 ± 3 | 63.5 ± 18.7 | 0.0002 |

| Triglycerides (mmol/l) | 1.4 ± 0.7 | 1.8 ± 1.7 | 0.9 |

| LDL—C (mmol/l) | 2.7 ± 0.9 | 2.23 ± 0.9 | 0.05 |

| eGFR (ml min/ [1.73 m]2) | 83 ± 7 | 82 ± 20 | 0.70 |

| ACR (mg/mmol) | 0.3 ± 0.1 | 7.5 ± 15.7 | < 0.0001 |

| Clinical neuropathy and QST measures | |||

| NSP (/38) | 0.15 ± 0.5 | 3.5 ± 4.5 | 0.0005 |

| NDS (/10) | 0.57 ± 1.0 | 3.7 ± 2.4 | < 0.0001 |

| VPT (V) | 7.5 ± 6.9 | 13.0 ± 8.0 | 0.06 |

| CPT (°C) | 28.4 ± 2.3 | 26.5 ± 3.5 | 0.51 |

| WPT (°C) | 36.9 ± 2.2 | 40.0 ± 3.7 | 0.20 |

| CIP (°C) | 9.0 ± 8.3 | 8.0 ± 8.5 | 0.90 |

| WIP (°C) | 45.0 ± 2.8 | 47.0 ± 2.5 | 0.15 |

| Autonomic neuropathy measures | |||

| DB-HRV (beats/min) | 30 ± 12 | 21 ± 15 | 0.005 |

| Neuropad (%) | 91.0 ± 21 | 62.4 ± 34 | 0.13 |

| Nerve conduction studies | |||

| SNAP (µV) | 17.9 ± 9.7 | 11.41 ± 10.9 | 0.06 |

| SNCV (m/s) | 49.8 ± 4.5 | 43.5 ± 9.0 | 0.01 |

| PNAP (mV) | 6.0 ± 2.2 | 3.8 ± 1.9 | 0.004 |

| PMNCV (m/s) | 48.7 ± 4.1 | 43.5 ± 3.6 | 0.0007 |

| Corneal confocal microscopy | |||

| CNFD (no./mm2) | 37.7 ± 6.5 | 28.8 ± 6.5 | < 0.0001 |

| CNBD (no./mm2) | 96.5 ± 38.6 | 67.6 ± 30.2 | 0.009 |

| CNFL (mm/mm2) | 27.2 ± 3.4 | 22.2 ± 4.9 | 0.0007 |

| Skin biopsy | |||

| IENFD (no./mm) | 9.8 ± 3.8 | 6.6 ± 4.3 | 0.04 |

BMI—body mass index, BP—blood pressure, HbA1c—Glycosylated haemoglobin, eGFR—estimated glomerular filtration rate, ACR—albumin creatinine ratio, LDL-C—low density lipoprotein cholesterol, NSP—neuropathy symptom profile, NDS—neuropathy disability score, VPT—vibration perception threshold, DBHRV—deep breathing heart rate variability, sural nerve action potential (SNAP), Sural nerve conduction velocity (SNCV), Peroneal nerve amplitude (PNAP), Peroneal motor nerve conduction velocity (PMNCV), CNFD—corneal nerve fibre density, CNBD—corneal nerve branch density, CNFL—corneal nerve fibre length, IENFD—intraepidermal nerve fibre density. Data is presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Bold values show statistically significant results. Continuous variables were compared between controls and baseline patient visits using the paired t-test for normally distributed data and Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank test for non-normally distributed data.

Table 2.

Clinical and neuropathy parameters in patients at baseline and follow up.

| Variable | Patients (Baseline) (n = 19) | Patients (Follow up) (n = 19) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical and laboratory parameters | |||

| Age (years) | 52.5 ± 14.7 | 59.5 ± 15.6 | NA |

| Duration of diabetes (years) | 26.0 ± 13.8 | 32.5 ± 13.8 | NA |

| Weight (kg) | 82.0 ± 19.8 | 81.75 ± 18 | 0.49 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 29.0 ± 5.7 | 28.7 ± 5.2 | 0.53 |

| BP (mmHg) | 132 ± 21/ 71 ± 8 | 127 ± 20 / 67 ± 9 | 0.37/0.08 |

| HbA1c (mmol/mol) | 63.5 ± 18.7 | 55.9 ± 12 | 0.04 |

| Triglycerides (mmol/l) | 1.8 ± 1.7 | 1.5 ± 1.1 | 0.9 |

| LDL-C (mmol/l) | 2.2 ± 0.9 | 1.9 ± 1.2 | 0.0009 |

| eGFR (ml min−1 [1.73 m]−2) | 82 ± 20 | 69 ± 21 | 0.004 |

| ACR (mg/mmol) | 7.5 ± 15.7 | 41.3 ± 123.6 | < 0.0001 |

| Clinical neuropathy measures and QST | |||

| NSP (/38) | 3.5 ± 4.5 | 5.5 ± 5.7 | 0.03 |

| NDS (/10) | 3.7 ± 2.4 | 4.7 ± 2.5 | 0.04 |

| VPT (V) | 13.0 ± 8.0 | 18.0 ± 9.0 | 0.02 |

| CPT (°C) | 26.5 ± 3.5 | 21.8 ± 9.2 | 0.006 |

| WPT (°C) | 40.0 ± 3.7 | 41. 2 ± 4.8 | 0.38 |

| CIP (°C) | 8.0 ± 8.5 | 8.0 ± 7.7 | 0.81 |

| WIP (°C) | 47.0 ± 2.5 | 47.1 ± 2.8 | 0.622 |

| Autonomic neuropathy measures | |||

| DB-HRV (beats/min) | 21.0 ± 15.0 | 19.0 ± 7.0 | 0.67 |

| LFa/RFa | 2.8 ± 2.5 | 2.7 ± 2.7 | 0.42 |

| E/I ratio | 1.3 ± 0.2 | 1.2 ± 0.2 | 0.004 |

| Valsalva ratio | 1.6 ± 0.7 | 1.4 ± 0.5 | 0.001 |

| 30:15 ratio | 1.3 ± 0.1 | 1.1± 0.1 | 0.0003 |

| Neuropad (%) | 62.4 ± 34.0 | 75.0 ± 31.0 | 0.47 |

| Nerve conduction studies | |||

| SNAP (µV) | 11.4 ± 10.9 | 10.5 ± 11.3 | 0.75 |

| SNCV (m/s) | 43.5 ± 9.0 | 40.4 ± 7.4 | 0.02 |

| PNAP (mV) | 3.8 ± 1.9 | 3.5 ± 1.9 | 0.299 |

| PMNCV (m/s) | 43.5 ± 3.6 | 42.4 ± 4.3 | 0.03 |

| Corneal confocal microscopy | |||

| CNFD (no./mm2) | 28.8 ± 6.5 | 25.6 ± 5.2 | 0.03 |

| CNBD (no./mm2) | 67.6 ± 30.2 | 43.7 ± 19.0 | < 0.0001 |

| CNFL (mm/mm2) | 22.2 ± 4.9 | 16.1 ± 3.6 | < 0.0001 |

| Skin biopsy | |||

| IENFD (no./mm) | 6.6 ± 4.3 | 5.2 ± 3.7 | 0.04 |

BMI—body mass index, BP—blood pressure, HbA1c—glycosylated haemoglobin, e GFR—estimated glomerular filtration rate, ACR—albumin creatinine ratio, LDL-C—low density lipoprotein cholesterol, NSP—neuropathy symptom profile, NDS—neuropathy disability score, VPT—vibration perception threshold, CPT—cold perception threshold, WPT—warm perception threshold, CIP—cold induced pain, WIP—warmth induced pain, DBHRV—deep breathing heart rate variability, LFa/RFa ratio—low frequency area (sympathetic) and respiratory frequency area (parasympathetic) ratio, E/I—expiration/inspiration ratio, Sural nerve action potential (SNAP), Sural nerve conduction velocity (SNCV), Peroneal nerve amplitude (PNAP), Peroneal motor nerve conduction velocity (PMNCV), CNFD—corneal nerve fibre density, CNBD—corneal nerve branch density, CNFL—corneal nerve fibre length, IENFD—intraepidermal nerve fibre density. Data is presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Bold values show statistically significant results. Continuous variables were compared between baseline and follow up visits using the paired t-test for normally distributed data and Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank test for non-normally distributed data.

Age (p = 0.2), weight (p = 0.9) and body mass index (BMI) (p = 0.5) did not differ significantly between patients and controls and also between patients at baseline and follow up. Systolic (p = 0.9, p = 0.37) and diastolic (p = 0.5, p = 0.08) blood pressure did not differ between controls and patients at baseline and between patients at baseline and follow up, respectively. HbA1c was significantly higher in patients with diabetes compared to controls at baseline (p = 0.0002) and decreased significantly in patients at follow up (p = 0.04). Low density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) was significantly lower in diabetic patients compared to controls at baseline (p = 0.05) and decreased further at follow up (p = 0.0009), whilst triglycerides did not differ between patients and controls at baseline (p = 0.9) and did not change at follow up (p = 0.9). eGFR did not differ significantly between diabetic patients and controls at baseline and decreased at follow up (p = 0.004). Albumin creatinine ratio (ACR) was significantly higher in diabetic patients compared to controls at baseline (p < 0.0001) and increased further at follow up (p < 0.0001).

Neuropathy assessments

Neuropathic symptoms and deficits (Tables 1, 2, Fig. 3)

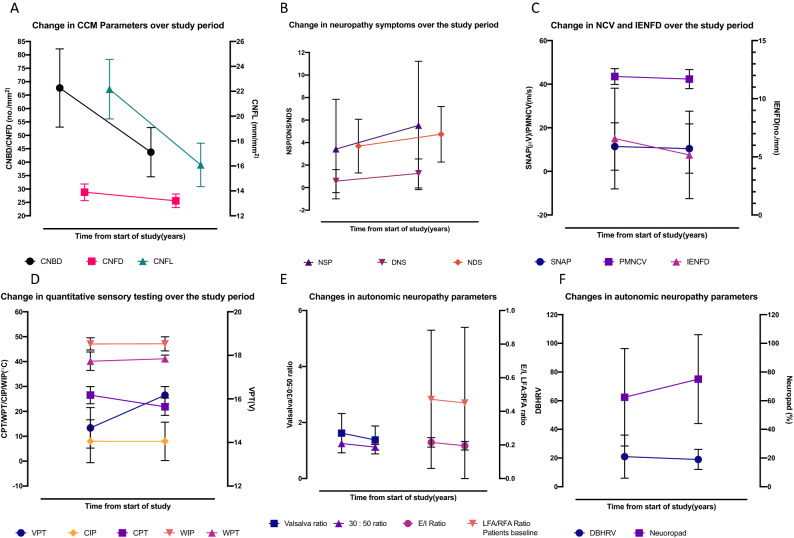

Figure 3.

Percentage change from baseline values in CCM parameters (A), neuropathy symptoms (B), NCV and IENFD (C), quantitative sensory testing (D) and autonomic neuropathy (E,F).

Neuropathy symptom profile (NSP) (p = 0.0005) and neuropathy disability score (NDS) (p < 0.0001) were significantly higher in patients at baseline compared to controls and increased significantly (p = 0.03, p = 0.04, respectively) in patients at follow up.

Quantitative sensory testing (QST) (Tables 1, 2, Fig. 3)

Vibration perception threshold (VPT), cold perception threshold (CPT), warm perception threshold (WPT), cold induced pain (CIP), warm induced pain (WIP) and percentage colour change in Neuropad did not differ significantly (p > 0.05) in patients at baseline compared to controls. Whilst VPT increased (p = 0.02) and CPT (p = 0.006) decreased significantly there was no change in WPT, CIP, WIP and Neuropad.

Electrophysiology (Tables 1, 2, Fig. 3)

Sural (p = 0.01) and peroneal (p = 0.007) nerve conduction velocity and peroneal nerve amplitude (p = 0.004) were significantly lower in patients at baseline compared to controls. Sural (p = 0.02) and peroneal (p = 0.03) nerve conduction velocity decreased significantly, with no change in sural (p = 0.75) or peroneal (p = 0.29) nerve amplitudes in patients at follow up.

Autonomic neuropathy (Tables 1, 2, Fig. 3)

Deep breathing heart rate variability (DB-HRV) was significantly lower in patients at baseline compared to controls (p = 0.005). Expiration/inspiration (E/I) ratio (p = 0.004), Valsalva ratio (p = 0.001), and 30:15 ratio (p = 0.003) increased significantly with no change in DB-HRV (p = 0.67) and sympathetic low frequency area (LFa)/parasympathetic respiratory frequency area (RFa) ratio (p = 0.42) at follow up.

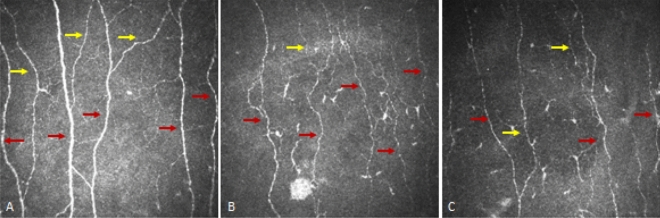

IENFD (Tables 1, 2, Figs. 1 and 3)

Figure 1.

Representative images from skin biopsies from healthy control (A) and diabetes patient of similar age at baseline (B) and a follow-up visit after 6.5 years (C). Note numerous branching nerves reaching top layers of epidermis (A; red arrows) and sparse short single nerve and two dividing nerves (red arrows) in epidermis of the baseline biopsy (B) and more difficult to discern shorter nerves in the follow-up biopsy (red arrows). Scale bar for A–C = 100 µm.

Intraepidermal nerve fibre density (IENFD) was significantly lower in patients at baseline (p = 0.04) compared to controls and decreased (p = 0.04) in patients at follow up.

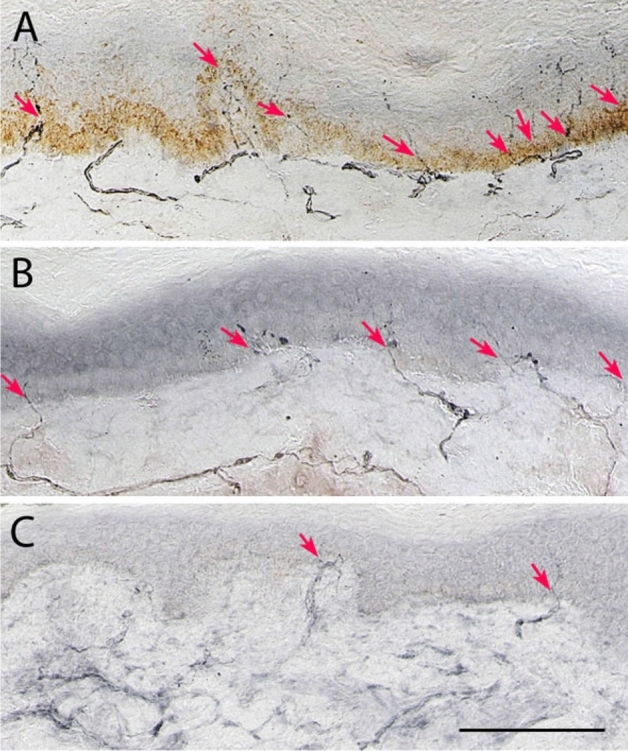

CCM (Tables 1, 2, Figs. 2 and 3)

Figure 2.

Corneal confocal microscopy image from a healthy control (A) and patient with diabetes at baseline (B) and follow-up (C) showing a progressive loss of nerve fibres (red arrows main nerves, yellow arrows branches) in patients with diabetes.

Corneal nerve fibre density (CNFD) (p < 0.0001), Corneal nerve branch density (CNBD) (p = 0.009) and Corneal nerve fibre length (CNFL) (p = 0.0007) were significantly lower in patients at baseline compared to controls and CNFD (p = 0.03), CNBD (p < 0.0001) and CNFL (p < 0.0001) decreased at follow up.

Associations between the change in clinical and neuropathy measures (Table 3, Fig. 3)

Table 3.

Correlations between percentage change in small fibre pathology and other measures of diabetic neuropathy from baseline to follow up.

| Variable | CNBD | CNFD | CNFL | IENFD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IENFD |

r = 0.53 p = 0.02 |

r = 0.62 p = 0.005 |

r = 0.56 p = 0.01 |

|

| NSP |

r = − 0.26 p = 0.29 |

r = − 0.43 p = 0.08 |

r = − 0.045 p = 0.86 |

r = − 0.07 p = 0.76 |

| NDS |

r = − 0.13 p = 0.58 |

r = − 0.43 p = 0.08 |

r = − 0.11 p = 0.66 |

r = − 0.05 p = 0.82 |

| CPT |

r = 0.076 p = 0.77 |

r = 0.29 p = 0.26 |

r = 0.66 p = 0.006 |

r = 0.27 p = 0.26 |

| VPT |

r = − 0.55 p = 0.02 |

r = − 0.54 p = 0.03 |

r = − 0.08 p = 0.76 |

r = − 0.12 p = 0.37 |

| DB-HRV |

r = − 0.19 p = 0.42 |

r = − 0.55 p = 0.02 |

r = − 0.14 p = 0.57 |

r = − 0.03 p = 0.87 |

| LFA/RFA ratio |

r = 0.26 p = 0.27 |

r = 0.09 p = 0.70 |

r = 0.017 p = 0.95 |

r = 0.13 p = 0.58 |

| E/I ratio |

r = 0.24 p = 0.32 |

r = 0.31 p = 0.21 |

r = 0.68 p= 0.002 |

r = 0.595 p= 0.007 |

| Valsalva ratio |

r = 0.41 p = 0.08 |

r = 0.14 p = 0.56 |

r = 0.25 p = 0. 32 |

r = 0.59 p= 0.008 |

NSP—neuropathy symptom profile, NDS—neuropathy disability score, DNS—diabetic neuropathy symptom score, VPT—vibration perception threshold, CPT—cold perception threshold, DB-HRV—deep breathing heart rate variability, LFA/RFA ratio—low frequency area (sympathetic) and high frequency area (parasympathetic) ratio, E/I—expiration/inspiration ratio, CNFD—corneal nerve fibre density, CNBD—corneal nerve branch density, CNFL—corneal nerve fibre length, IENFD—intraepidermal nerve fibre density. Bold values show statistically significant results.

ΔIENFD correlated with age (r = − 0.56, p = 0.01), BMI (r = − 0.47, p = 0.04), waist to hip ratio (r = − 0.66, p = 0.001), ΔE/I ratio (r = 0.595, p = 0.0071) and ΔValsalva ratio (r = 0.59, p = 0.0078). ΔCNFD correlated with ΔVPT (r = − 0.54, p = 0.03), ΔDBHRV (r = 0.55, p = 0.02) and ΔIENFD (r = 0.62, p = 0.005). ΔCNFL correlated with ΔCPT (r = 0.66, p = 0.006), ΔE/I ratio (r = 0.68, p = 0.002) and ΔIENFD (r = 0.56, p = 0.014). ΔCNBD correlated with ΔVPT (r = − 0.55, p = 0.02) and ΔIENFD (r = 0.53, p = 0.02). There was no correlation between change in HbA1c, lipids and neurophysiological parameters with change in CCM or IENFD (Supplementary Table 1).

Discussion

In this study we show a progressive worsening of diabetic neuropathy in diabetic patients despite an improvement in HbA1c and LDL cholesterol, although there was no correlation between change in HbA1c, and LDL cholesterol with change in any measure of neuropathy. In T1DM the DCCT showed that intensive glycaemic control reduced the incidence of DPN3. However, in patients with T2DM, the UKPDS4, VA-CSDM trial5 and ACCORD7 trials showed no effect of improved glycaemic control on DPN. A major problem in these clinical trials was the end points utilised to assess neuropathy including symptoms and signs of neuropathy and quantitative sensory testing, which were unable to accurately measure change in neuropathy2.

Neurophysiology is considered to be the gold standard for the diagnosis of DPN and has been adopted as an endpoint in multiple clinical trials9, but has failed to show a significant change in these trials24. Indeed, our longitudinal data now shows a relatively small magnitude of reduction in peroneal and sural nerve conduction with no change in amplitudes over 6.5 years. It is therefore not surprising that most trials lasting 12–24 months show no change in neurophysiology.

Small fibre damage usually precedes large fibre damage and contributes to clinically meaningful end-points like painful diabetic neuropathy and foot ulceration due to altered skin blood flow and delayed wound healing2. Skin biopsy with IENFD quantification is the current gold standard for the evaluation of small fibre damage9 and whilst it is reliable and reproducible it is invasive and resource-intensive11. CCM is a rapid, non-invasive and reproducible ophthalmic imaging technique which can be used to objectively quantify small fibre damage in a range of peripheral neuropathies15,25–29. We have previously shown comparable diagnostic utility of CCM and IENFD in diabetic neuropathy19. Furthermore, in longitudinal studies reduced corneal nerve fibre length predicts incident DPN30,31 and those at risk of developing DPN32. Indeed, CCM has shown corneal nerve regeneration 6 months after pancreas and kidney transplantation in T1DM with no change in quantitative sensory testing and an improvement in neuropathic symptoms and nerve conduction only after 24 and 36 months, respectively21,33. A recent study from Japan showed that an improvement in glycaemic control, body weight and blood pressure in patients with T2DM was associated with an improvement in corneal nerve fibres, neurophysiology and vibration perception over 4 years and correlated with a reduction in HbA1c34.

Studies have also shown an association between CCM and LDIflare in healthy control subjects35 and with LDIflare, cooling detection thresholds and HRV in patients with diabetes16. In the present study CCM measures worsened with greater magnitude than IENFD and large fibre (VPT, CPT, sural and peroneal nerve conduction velocities) and autonomic (E/I ratio, Valsalva ratio and 30:15 ratio) measures of neuropathy. The worsening of corneal nerve fibre measures was associated with worsening of other small fibre measures including cold perception threshold, IENFD and autonomic neuropathy, but not neurophysiology. Indeed, a number of studies have shown corneal nerve loss in patients with diabetic autonomic neuropathy36–38 and a correlation between CCM and a wide range of other measures of neuropathy including peroneal and sural nerve conduction36 and both cold and warm perception thresholds16,39.

A limitation of this study is the relatively small number of patients assessed at follow up. However, the main strength of this study is the comprehensive phenotyping of diabetic neuropathy over 6.5 years, enabling a detailed comparison of the change in small and large fibre measures of diabetic neuropathy.

In conclusion, CCM identifies progressive nerve damage despite an improvement in glycaemic control and LDL cholesterol. Furthermore, corneal nerve loss was associated with a loss of IENFD and worsening of other measures of small fibre neuropathy. CCM is a rapid, non-invasive test to identify progression of neuropathy and may have greater utility than symptoms, signs, QST and nerve conduction studies in longitudinal follow-up studies and clinical trials of DPN.

Methods

Participant selection

Nineteen patients with diabetes [type 1 DM (n = 15) and type 2 DM (n = 4)], from the Manchester University Hospital Diabetes Centre and 19 age-matched healthy control participants were recruited and assessed between 2009 and 2011 and at follow up in 2017. The control group comprised of healthy volunteers without DM and were not on any regular medications for any co-morbidities. Patients with a history of neuropathy from any other cause, ocular disease, corneal trauma or surgery, systemic disorders affecting the skin or cornea were excluded. All the tests performed at baseline were repeated in the follow up study using the same protocol and equipment. This study has approval from the Health Research Authority (HRA), North West—Greater Manchester South Research Ethics Committee. Written informed consent was obtained from all individuals prior to participation. This research adhered to the tenets of the declaration of Helsinki.

Anthropometric and laboratory measurements

All participants underwent assessment of height, weight and body mass index (BMI). Glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c), total cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein (LDL)-cholesterol, triglycerides (TG), serum creatinine and urinary albumin creatinine ratio (ACR) were measured using routine laboratory methods in the Department of Biochemistry, Manchester University NHS Foundation Trust. Estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was calculated using the abbreviated Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD) equation: 186 × (creatinine/88.4) − 1.154 × (age) − 0.203 × (0.742 in females) × (1.210 if Afro-Caribbean race).

Assessment of neuropathy

The neuropathy symptom profile (NSP) was used to assess the symptoms of neuropathy. The modified neuropathy disability score (NDS) which is comprised of an assessment of vibration perception, pinprick, temperature sensation and presence or absence of ankle reflexes was used to evaluate neurological deficits. A Horwell Neurothesiometer (Scientific Laboratory Supplies, Wilford, Nottingham, UK) was used to establish the Vibration Perception Threshold (VPT). Cold (CT) and warm (WT) perception thresholds and cold (CIP) and warm induced pain (WIP) thresholds were tested on the dorsolateral aspect of left foot using the TSA-II NeuroSensory Analyser (Medoc, Ramat-Yishai, Israel). Electrodiagnostic nerve conduction studies (NCS) were undertaken using a Dantec Keypoint System (Dantec Dynamics, Bristol, UK), equipped with a DISA temperature regulator to keep the limb temperature constant at 32–35 °C. The ANX 3.0 autonomic nervous system monitoring device (ANSAR Medical Technologies, Philadelphia, PA, USA) was used to assess deep breathing heart rate variability (DB-HRV), sympathovagal balance via the sympathetic low frequency area (LFa)/parasympathetic respiratory frequency area (RFa) ratio, expiratory/inspiratory (E/I ratio), Valsalva ratio and 30:15 ratio. Sudomotor dysfunction was assessed by quantifying the percentage colour change after applying the Neuropad to the area over the base of the first metatarsal head using our previously established protocol and automated quantification40.

Skin biopsy

Local anaesthetic (1% lignocaine) was applied to the dorsum of the foot, 2 cm above the second metatarsal head and two 3 mm punch biopsies were performed. Sections of 50 µm were stained using anti-human PGP 9.5 antibody (Abcam, Cambridge, UK). SG chromogen (Vector Laboratories, Peterborough, UK) was used to demonstrate nerve fibres and IENFD was quantified using previously established criteria and expressed as the number per millimetre length of epidermis41. The follow-up skin biopsy was taken from the same foot, in close proximity to the first biopsy. IENFD was quantified by the same investigator in a masked fashion.

Corneal confocal microscopy (CCM)

CCM examination (Heidelberg Retinal Tomography III Rostock Cornea Module; Heidelberg Engineering, Heidelberg, Germany) was performed using our previously established protocol42. Six non-overlapping images, three per eye, were selected from the centre of the cornea. Three corneal nerve parameters were quantified: Corneal nerve fibre density (CNFD): the total number of major nerve fibres per square millimetre of corneal tissue, corneal nerve fibre branch density (CNBD): the number of branches emanating from the major nerve trunks per square millimetre of corneal tissue and corneal nerve fibre length (CNFL): the total length of all nerve fibres and branches (millimetre per square millimetre) using manual quantification software [CCMetrics (Manchester, UK)]43.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism for Mac OS X (version 8.3.0, GraphPad Software, San Diego, California USA, www.graphpad.com). Data were tested for normality using the Shapiro–Wilk normality test. All data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Continuous variables were compared between baseline and follow up visits using the paired t-test for normally distributed data and Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank test for non-normally distributed data. Ordinary one-way ANOVA was performed (Kruskal–Wallis test was used for non-normally distributed data) to compare between group differences of controls and baseline patient values. Post-hoc corrections for multiple comparison testing was done using Tukey’s test. Correlations were performed between the percentage change in IENFD and CCM parameters and other variables using Pearson’s or Spearman’s Rank Test according to the distribution of the data. A two-way p-value of less than 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge Mitra Tavakoli for undertaking some of the corneal confocal scans and Hassan Fadavi for undertaking some of the neurological evaluation, QST and AFT testing at baseline. We acknowledge support from Manchester Comprehensive Local Research Network and The National Institute for Health Research/Wellcome Trust Clinical Research Facility in Manchester.

Author contributions

All authors were involved in revising the manuscript critically for important intellectual content and for final approval of the version to be published. S.D. and M.F. were involved in acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data and wrote the manuscript. S.D., S.A., J.H.H., M.F. and A.K. recruited patients for follow up. S.D., S.A. and J.H.H. contributed to acquisition and analysis of the data. S.Az., U.A., G.P., I.P. and M.F. recruited patients at baseline. S.Az., U.A. performed skin biopsies for patients and controls at baseline and SD performed skin biopsies for all patients at follow up. G.P., I.P. and M.F. performed C.C.M. for patients and controls at baseline. M.F. and A.K. performed C.C.M. for patients at follow up. A.A. processed skin biopsies on follow up patients. M.J. analysed and reported skin biopsies for all patients and controls at baseline and follow up. A.M. performed and analysed nerve conduction studies for all patients and controls at baseline and at follow up. H.S. contributed to conception, interpretation of the data, wrote and revised the manuscript. R.A.M. contributed to conception and design of the study, wrote and revised the manuscript and is principal investigator of the study. R.A.M. is the guarantor of this work and, as such, had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Funding

This research was funded from a National Institutes of Health Grant (R105991).

Data availability

The datasets generated and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-021-81302-8.

References

- 1.Malik RA, Veves A, Tesfaye S, Smith G, Cameron N, Zochodne D, et al. Small fibre neuropathy: Role in the diagnosis of diabetic sensorimotor polyneuropathy. Diabetes Metab. Res. Rev. 2011;27(7):678–684. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.1222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tavee J, Zhou L. Small fiber neuropathy: A burning problem. Cleve Clin. J. Med. 2009;76(5):297–305. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.76a.08070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Diabetes C, Complications Trial Research G, Nathan DM, Genuth S, Lachin J, Cleary P, et al. The effect of intensive treatment of diabetes on the development and progression of long-term complications in insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. N. Engl. J. Med. 1993;329(14):977–986. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199309303291401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Intensive blood-glucose control with sulphonylureas or insulin compared with conventional treatment and risk of complications in patients with type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 33). UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) Group. Lancet. 352(9131), 837–853 (1998). [PubMed]

- 5.Azad N, Emanuele NV, Abraira C, Henderson WG, Colwell J, Levin SR, et al. The effects of intensive glycemic control on neuropathy in the VA cooperative study on type II diabetes mellitus (VA CSDM) J. Diabetes Complicat. 1999;13(5–6):307–313. doi: 10.1016/S1056-8727(99)00062-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ohkubo Y, Kishikawa H, Araki E, Miyata T, Isami S, Motoyoshi S, et al. Intensive insulin therapy prevents the progression of diabetic microvascular complications in Japanese patients with non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus: A randomized prospective 6-year study. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 1995;28(2):103–117. doi: 10.1016/0168-8227(95)01064-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ismail-Beigi F, Craven T, Banerji MA, Basile J, Calles J, Cohen RM, et al. Effect of intensive treatment of hyperglycaemia on microvascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes: An analysis of the ACCORD randomised trial. Lancet. 2010;376(9739):419–430. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60576-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dyck PJ, Bushek W, Spring EM, Karnes JL, Litchy WJ, O'Brien PC, et al. Vibratory and cooling detection thresholds compared with other tests in diagnosing and staging diabetic neuropathy. Diabetes Care. 1987;10(4):432–440. doi: 10.2337/diacare.10.4.432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dyck PJ, Overland CJ, Low PA, Litchy WJ, Davies JL, Dyck PJ, et al. Signs and symptoms versus nerve conduction studies to diagnose diabetic sensorimotor polyneuropathy: Cl vs NPhys trial. Muscle Nerve. 2010;42(2):157–164. doi: 10.1002/mus.21661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nebuchennykh M, Loseth S, Lindal S, Mellgren SI. The value of skin biopsy with recording of intraepidermal nerve fiber density and quantitative sensory testing in the assessment of small fiber involvement in patients with different causes of polyneuropathy. J. Neurol. 2009;256(7):1067–1075. doi: 10.1007/s00415-009-5065-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lauria G, Devigili G. Skin biopsy as a diagnostic tool in peripheral neuropathy. Nat. Clin. Pract. Neurol. 2007;3(10):546–557. doi: 10.1038/ncpneuro0630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lauria G, Hsieh ST, Johansson O, Kennedy WR, Leger JM, Mellgren SI, et al. European federation of neurological societies/peripheral nerve society guideline on the use of skin biopsy in the diagnosis of small fiber neuropathy. Report of a joint task force of the European Federation of Neurological Societies and the Peripheral Nerve Society. Eur. J. Neurol. 2010;17(7):903-12, e44-9. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2010.03023.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kramer HH, Schmelz M, Birklein F, Bickel A. Electrically stimulated axon reflexes are diminished in diabetic small fiber neuropathies. Diabetes. 2004;53(3):769–774. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.3.769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Serra J. Re-emerging microneurography. J. Physiol. 2009;587(2):295–296. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.167858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Petropoulos IN, Alam U, Fadavi H, Asghar O, Green P, Ponirakis G, et al. Corneal nerve loss detected with corneal confocal microscopy is symmetrical and related to the severity of diabetic polyneuropathy. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(11):3646–3651. doi: 10.2337/dc13-0193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sivaskandarajah GA, Halpern EM, Lovblom LE, Weisman A, Orlov S, Bril V, et al. Structure-function relationship between corneal nerves and conventional small-fiber tests in type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(9):2748–2755. doi: 10.2337/dc12-2075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Petropoulos IN, Alam U, Fadavi H, Marshall A, Asghar O, Dabbah MA, et al. Rapid automated diagnosis of diabetic peripheral neuropathy with in vivo corneal confocal microscopy. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2014;55(4):2071–2078. doi: 10.1167/iovs.13-13787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alam U, Jeziorska M, Petropoulos IN, Asghar O, Fadavi H, Ponirakis G, et al. Diagnostic utility of corneal confocal microscopy and intra-epidermal nerve fibre density in diabetic neuropathy. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(7):e0180175. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0180175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen X, Graham J, Dabbah MA, Petropoulos IN, Ponirakis G, Asghar O, et al. Small nerve fiber quantification in the diagnosis of diabetic sensorimotor polyneuropathy: comparing corneal confocal microscopy with intraepidermal nerve fiber density. Diabetes Care. 2015;38(6):1138–1144. doi: 10.2337/dc14-2422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dehghani C, Pritchard N, Edwards K, Russell AW, Malik RA, Efron N. Risk factors associated with corneal nerve alteration in type 1 diabetes in the absence of neuropathy: A longitudinal in vivo corneal confocal microscopy study. Cornea. 2016;35(6):847–852. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0000000000000760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Azmi S, Jeziorska M, Ferdousi M, Petropoulos IN, Ponirakis G, Marshall A, et al. Early nerve fibre regeneration in individuals with type 1 diabetes after simultaneous pancreas and kidney transplantation. Diabetologia. 2019;62(8):1478–1487. doi: 10.1007/s00125-019-4897-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Deak EA, Szalai E, Toth N, Malik RA, Berta A, Csutak A. Longitudinal changes in corneal cell and nerve fiber morphology in young patients with type 1 diabetes with and without diabetic retinopathy: A 2-year follow-up study. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2019;60(2):830–837. doi: 10.1167/iovs.18-24516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jia X, Wang X, Wang X, Pan Q, Xian T, Yu X, et al. In vivo corneal confocal microscopy detects improvement of corneal nerve parameters following glycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes. J Diabetes Res. 2018;2018:8516276. doi: 10.1155/2018/8516276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Malik RA. Wherefore art thou, O treatment for diabetic neuropathy? Int. Rev. Neurobiol. 2016;127:287–317. doi: 10.1016/bs.irn.2016.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Petropoulos IN, Manzoor T, Morgan P, Fadavi H, Asghar O, Alam U, et al. Repeatability of in vivo corneal confocal microscopy to quantify corneal nerve morphology. Cornea. 2013;32(5):e83–e89. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e3182749419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kemp HI, Petropoulos IN, Rice ASC, Vollert J, Maier C, Strum D, et al. Use of corneal confocal microscopy to evaluate small nerve fibers in patients with human immunodeficiency virus. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2017;135(7):795–800. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2017.1703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stettner M, Hinrichs L, Guthoff R, Bairov S, Petropoulos IN, Warnke C, et al. Corneal confocal microscopy in chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy. Ann. Clin. Transl. Neurol. 2016;3(2):88–100. doi: 10.1002/acn3.275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pagovich OE, Vo ML, Zhao ZZ, Petropoulos IN, Yuan M, Lertsuwanroj B, et al. Corneal confocal microscopy: Neurologic disease biomarker in Friedreich ataxia. Ann. Neurol. 2018;84(6):893–904. doi: 10.1002/ana.25355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tavakoli M, Marshall A, Banka S, Petropoulos IN, Fadavi H, Kingston H, et al. Corneal confocal microscopy detects small-fiber neuropathy in Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease type 1A patients. Muscle Nerve. 2012;46(5):698–704. doi: 10.1002/mus.23377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lovblom LE, Halpern EM, Wu T, Kelly D, Ahmed A, Boulet G, et al. In vivo corneal confocal microscopy and prediction of future-incident neuropathy in type 1 diabetes: A preliminary longitudinal analysis. Can. J. Diabetes. 2015;39(5):390–397. doi: 10.1016/j.jcjd.2015.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pritchard N, Edwards K, Russell AW, Perkins BA, Malik RA, Efron N. Corneal confocal microscopy predicts 4-year incident peripheral neuropathy in type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2015;38(4):671–675. doi: 10.2337/dc14-2114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lewis EJ, Perkins BA, Lovblom LE, Bazinet RP, Wolever TM, Bril V. Using in vivo corneal confocal microscopy to identify diabetic sensorimotor polyneuropathy risk profiles in patients with type 1 diabetes. BMJ Open Diabetes Res. Care. 2017;5(1):e000251. doi: 10.1136/bmjdrc-2016-000251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tavakoli M, Mitu-Pretorian M, Petropoulos IN, Fadavi H, Asghar O, Alam U, et al. Corneal confocal microscopy detects early nerve regeneration in diabetic neuropathy after simultaneous pancreas and kidney transplantation. Diabetes. 2013;62(1):254–260. doi: 10.2337/db12-0574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ishibashi F, Taniguchi M, Kosaka A, Uetake H, Tavakoli M. Improvement in neuropathy outcomes with normalizing HbA1c in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2019;42(1):110–118. doi: 10.2337/dc18-1560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sharma S, Tobin V, Vas PRJ, Malik RA, Rayman G. The influence of age, anthropometric and metabolic variables on LDIFLARE and corneal confocal microscopy in healthy individuals. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(3):e0193452. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0193452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ziegler D, Papanas N, Zhivov A, Allgeier S, Winter K, Ziegler I, et al. Early detection of nerve fiber loss by corneal confocal microscopy and skin biopsy in recently diagnosed type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. 2014;63(7):2454–2463. doi: 10.2337/db13-1819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang H, Fan D, Wang W, Zhang S, Wang X. Early diagnosis of diabetic autonomic neuropathy by corneal confocal microscopy. Zhonghua yi xue za zhi. 2015;95(35):2851–2856. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Misra SL, Craig JP, Patel DV, McGhee CN, Pradhan M, Ellyett K, et al. In vivo confocal microscopy of corneal nerves: An ocular biomarker for peripheral and cardiac autonomic neuropathy in type 1 diabetes mellitus. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2015;56(9):5060–5065. doi: 10.1167/iovs.15-16711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Quattrini C, Tavakoli M, Jeziorska M, Kallinikos P, Tesfaye S, Finnigan J, et al. Surrogate markers of small fiber damage in human diabetic neuropathy. Diabetes. 2007;56(8):2148–2154. doi: 10.2337/db07-0285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ponirakis G, Fadavi H, Petropoulos IN, Azmi S, Ferdousi M, Dabbah MA, et al. Automated quantification of neuropad improves its diagnostic ability in patients with diabetic neuropathy. J. Diabetes Res. 2015;2015:847854. doi: 10.1155/2015/847854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lauria G, Schmitz C, Lombardi R, et al. Intraepidermal nerve fiber density at the distal leg: a worldwide normative reference study. J. Peripher. Nerv. Syst. 2020;15(3):202–207. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8027.2010.00271.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Malik RA, Kallinikos P, Abbott CA, van Schie CH, Morgan P, Efron N, et al. Corneal confocal microscopy: A non-invasive surrogate of nerve fibre damage and repair in diabetic patients. Diabetologia. 2003;46(5):683–688. doi: 10.1007/s00125-003-1086-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dabbah MA, Graham J, Petropoulos IN, Tavakoli M, Malik RA. Automatic analysis of diabetic peripheral neuropathy using multi-scale quantitative morphology of nerve fibres in corneal confocal microscopy imaging. Med Image Anal. 2011;15(5):738–747. doi: 10.1016/j.media.2011.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.