Abstract

Recent reports have suggested that age-related arterial stiffening and excessive cerebral arterial pulsatility cause blood–brain barrier breakdown, brain atrophy and cognitive decline. This has spurred interest in developing non-invasive methods to measure pulsatility in distal vessels, closer to the cerebral microcirculation. Here, we report a method based on four-dimensional (4D) flow MRI to estimate a global composite flow waveform of distal cerebral arteries. The method is based on finding and sampling arterial waveforms from thousands of cross sections in numerous small vessels of the brain, originating from cerebral cortical arteries. We demonstrate agreement with internal and external reference methods and show the ability to capture significant increases in distal cerebral arterial pulsatility as a function of age. The proposed approach can be used to advance our understanding regarding excessive arterial pulsatility as a potential trigger of cognitive decline and dementia.

Keywords: 4D flow MRI, cerebral hemodynamics, arterial pulsatility, cerebral cortical arteries, aging

Introduction

With advancing age, elastic arteries dilate and stiffen, and the ability to effectively dampen pulsatile blood flow is impaired.1,2 In turn, cardiac pulsatility is transferred towards more distal arteries of the brain, and pulsatile flow and pressure fluctuations extend deeper into smaller cerebral vessels.2,3 Pulsatile stress to the cerebral vasculature has emerged as a potential trigger of microvascular damage, and is thought to be a contributing factor to neurodegeneration and cognitive dysfunction.3–7 Indeed, elevated carotid wave intensity and peripheral arterial pulse pressure have been shown predictive of cognitive decline8 and progression towards dementia.9,10 Further, increased pulsatility in cerebral arteries has been linked to white matter lesions,11,12 regional brain volume,13 cognitive impairment14 and Alzheimer’s disease.15

Causal mechanisms linking pulsatility and brain pathology are not yet fully understood, but a recent study in mice showed that increasing pulse pressure by surgically reducing aortic compliance is followed by cerebral microvascular damage, a leaky blood–brain barrier, beta-amyloid accumulation, neurovascular coupling dysfunction and cognitive decline.16 Under physiological conditions, arterial pulsatility is also suggested to be a primary driver of perivascular glymphatic bulk flow, promoting clearance of interstitial waste.17–19 However, an experimentally induced increase in arterial blood pressure with concomitant increases in distal cerebral arterial pulsatility, suggest that perivascular glymphatic bulk flow is impeded as pulsations are growing excessively large.19

Interindividual and age-dependent differences in arterial compliance and transmission of pulsatility towards the brain have highlighted the importance of developing methodologies to assess pulsatility in distal cerebral arteries.4 In younger individuals, dampening along tortuous segments of the internal carotid artery appears to be an important protective mechanism, absorbing a substantial amount of the pulse wave before it reaches the cerebral vasculature.20,21 In aging, internal carotid artery pulsatility is increased, and the ability of the cerebral arteries to dampen pulsatile flow is reduced, with marked interindividual variability in dampening within age groups as well.22 Taken together, these findings indicate that the exposure of the cerebral microcirculation to pulsatile stress may not be easily inferred from large arteries.

Human studies have explored measurements in large cerebral arteries using 2D phase contrast MRI13,23 (PCMRI) or transcranial Doppler (TCD) ultrasound.11,14 In recent efforts to provide pulsatility of more distal vasculature, 2D PCMRI with extremely high velocity sensitivity and a 7 T scanner have been shown effective in cerebral perforating arteries.24,25 In addition, the signal has been used to characterize microvascular blood volume change over the cardiac cycle.26,27 4D flow MRI makes it possible to measure time-resolved blood flow velocities with sub-millimeter resolution and whole-brain coverage.28–30 In previous studies, 4D flow MRI has been used to quantify pulsatility in large cerebral arteries by measuring blood flow at specific cross sections of interest.15,31 However, such analyses are not feasible for small vessels as the velocity data are hampered by low velocity-to-noise levels.

Recently, a 4D flow MRI centerline processing scheme for semiautomated quantification was developed and evaluated in large cerebral arteries.32,33 This concept can theoretically be expanded to automatically recover signal from noisy samples of small distal arteries. In this study, we formalize this concept and introduce a 4D flow MRI approach to assess pulsatility in distal cerebral arteries, originating mainly from cortical branches of the cerebral arterial tree. The strength of the proposed method is harnessed from its ability to provide averaging of arterial waveforms sampled from thousands of arterial cross sections (estimated diameters 0.75–1.25 mm), in order to compute global pulsatility scores from distal cerebral arterial waveforms. In a cross-sectional sample, we evaluate the method against external reference composite pulsatility scores obtained from multiple 2D PCMRI scans of well-defined branches, as well as against internal reference measures of distal pulsatility relying on manually selected arteries of interest. In addition, we evaluate the stability of the proposed global pulsatility scores by comparing results derived from a left-right hemisphere split. Finally, we apply the method to investigate the expected positive association between age and pulsatility in distal cerebral arteries.

Materials and methods

Participants

The study population was originally recruited in 2007 and consisted of 50 subjects aged 60–82 years that had MRI acquisitions. At that time, subjects were eligible for MRI if they were without psychiatric or neurological disorders and without signs of advanced atherosclerotic disease. The investigation procedure has been described in detail.34

In the present study, a new invitation was sent to the original study cohort in 2017. Of the 50 participants, 7 were deceased and 2 had relocated, and of the remaining, 38 accepted to participate. Five were excluded due to incomplete MR acquisitions, and the final study population in this study thus consisted of 33 individuals (mean age 79 years; range 70–91; 20 women). Their current health status was examined by a neurologist, and the following diseases had supervened since their last visit 10 years earlier: cerebrovascular disease (N = 5), Alzheimer’s disease (N = 2), Lewy body dementia (N = 1), ischemic heart disease (N = 2), diabetes mellitus (N = 2) and atrial fibrillation (N = 3). The following vascular risk factors were noted: hypertension (N = 21), hyperlipidemia (N = 13), smoking (current = 1, previous = 6). Blood pressure measurements were performed on the left arm using an Arteriograph (Omron HEM757; Omron Matsusaka Co. Ltd., Mie, Japan) while the participants remained in sitting position.

The study was approved by the ethical review board of Umeå University (dnr: 2017/253-31). Oral and written informed consent was obtained from all participants. The study was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki ethical principles.

MRI protocols

MR scans including 4D flow MRI and 2D PCMRI were performed on all subjects using a clinical 3 T scanner (Discovery MR 750; GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, Wisconsin) with a 32-channel head coil. An anatomical T1-weighted magnitude image was also reconstructed from the 4D flow MRI data. None of the scans involved any contrast agents.

4D flow MRI acquisitions were performed with full brain coverage. PC-VIPR29 is a highly undersampled radial projection sequence, acquiring time-resolved flow rate in all three spatial directions. Imaging parameters: 5-point velocity encoding (venc) 110 cm/s, repetition time/echo time (TR/TE) 6.5/2.7 ms, flip angle 8, radial projections 16000, temporal resolution 20 frames per cardiac cycle, spatial resolution at acquisition 300 × 300×300, imaging volume 22 × 22×22 cm3, spatial resolution after reconstruction 320 × 320×320 and voxel size 0.69 mm isotropic. The total PC-VIPR scan time was approximately 9 min.

2D PCMRI acquisitions were performed at the left and right middle cerebral artery (MCA) at the M1 level, anterior cerebral artery (ACA) at the A2 level and posterior cerebral artery (PCA) at the P2 level. Imaging parameters: venc 60–100 cm/s, TR/TE 7.6–10.7/4.1–4.7 ms, flip angle 15, temporal resolution 32 frames per cardiac cycle, slice thickness 3 mm, matrix size 512 × 512 voxels and in-plane resolution 0.35 × 0.35 mm2. Measurement planes were placed perpendicular to each artery. In two participants, planes covering the first branch of MCA could not be properly placed due to almost immediate bifurcations. To overcome this, planes were placed to cover the two distal branches (for these two participants only), and MCA flow rate was computed as the sum of the flow rates through the two distal planes.

4D flow MRI processing

FreeSurfer 6.0.0 (http://surfer.nmr.mgh.harvard.edu/), with the anatomical magnitude image obtained from the 4D flow MRI scan as input, was used for automatic segmentation of the brain.35 This brain segmentation was used as a mask in the 4D flow MRI volumes, excluding extracerebral vasculature of no interest. All development and the remaining data processing were performed in MATLAB (version 9.3.0. Natick, Massachusetts: The MathWorks Inc.).

A 4D flow MRI-derived complex difference (CD) volume (obtained from combining velocity and magnitude data) that suppresses stationary tissue and highlights vasculature29 was used to localize all potential distal arterial branches. To further improve the visibility of small arteries, a vessel enhancement filter36 ( = 1) was applied to the CD. A coarse binarization of the cerebrovascular tree was done using a global intensity-based threshold (at 2.5% of global max) on the filtered CD volume. A centerline processing scheme for semi-automatic flow quantification of 4D flow MRI data was employed, utilizing automatic positioning of orthogonal cut-planes along all centerline voxels of the cerebrovascular tree.32 In short, skeletonization and centerline algorithms were used to extract centerline voxels from the binary cerebrovascular tree. Vessel direction at each centerline voxel was then estimated based on neighboring voxels positioned two steps away in the centerline structure. In the orthogonal planes (squares with 9-pixel sides), interpolation was used to increase the resolution by a factor of 4. Vessels were then separated from background using a stringent local intensity-based threshold (at 50% of max in the filtered CD plane). From each segmented vessel cross section, area was estimated by considering the sum of the included pixels (as well as pixel size), and diameter was computed using the area–diameter relationship for a circle. The stringent local threshold was chosen to distinguish between neighboring vessels and to minimize the noise contribution to the sampled waveform, and under the assumption of laminar flow with a homogenous velocity distribution throughout the cardiac cycle, the level of this threshold should not bias the relative shape of the flow waveform.

An approach to separate distal cerebral arteries from large arteries and from veins was developed, relying on assumptions about vessel size and different expressions of a cardiac-related waveform. This approach was based on first making a K-means clustering of the median temporal waveform of each branch (computed from multiple cross sections). As venous and arterial branches were both expected to be represented in the volume, a two-class solution of the K-means clustering was selected. Within branches of the arterial cluster, a diameter threshold was used to isolate small arteries of interest. Based on inspection of a histogram (presented in the results section), it could be observed that below a diameter of 2 mm, rapid branching occurred, vastly increasing the number of available cross sections. Below 1 mm, the number of available cross sections rapidly vanished as the 4 D flow MRI sequence was not capable of resolving smaller vasculature. As the overarching ambition was to measure the flow waveform in as small branches as possible, the developed method was systematically evaluated for upper diameter thresholds ranging between 1 and 2 mm. In addition, a lower threshold of 0.75 mm was used for all evaluations to reduce the influence of extremely small noisy segments. A brain-wide, global composite distal arterial waveform was computed, as a median of the normalized (through division by the mean flow rate) waveforms of all identified cross sections.

4D flow MRI internal reference

As an internal validation of the performance of the automatic arterial segmentation (for deriving measures of distal cerebral arterial pulsatility), manual segmentations of distal cerebral arteries in a subset of subjects (N = 12) were performed. Specifically, regions of interest (ROIs) representing the desired distal arterial segments in the left and right ACA, MCA and PCA were manually drawn by tracing vessels slice by slice in a 3D volume using the software Freeview (distributed with FreeSurfer 6.0). The manually drawn ROIs were confined to include ACA A3, MCA M3 and PCA P3 as well as connecting distal branches (e.g. no spurs or segments from potential veins were included). More precisely, the manually drawn ROIs were defined according to:

Distal ACA: starting at A3 rostral to the genu of the corpus callosum and continuing to include connecting A4 and A5 branches superior to the corpus callosum.

Distal MCA: starting at M3 identified as MCA branches projecting laterally within the sylvian fissure and continuing to include connecting M4 branches along the surface of the cerebral cortex.

Distal PCA: starting where PCA splits into P3 (within the quadrigeminal cistern) and P4 (within the calcarine fissure) and continuing to include connecting segments distal to P3 and P4.

Visualization of the marked arteries from the manually drawn ROIs is provided in the supplementary material (Suppl. Figure 1). Arterial waveforms were sampled from cross sections at each centerline voxel confined within these ROIs, to compute a composite distal arterial waveform as a median of the sampled arterial waveforms. This was done in analogy to the automatically derived 4D flow MRI distal arterial waveform, with the distinction that manual selection of arteries replaced the combination of K-means clustering and diameter thresholding to identify distal cerebral arteries.

4D flow MRI left-right hemisphere split

As a global representation of distal cerebral arterial pulsatility can only be motivated under the assumption that pulsatility is equal between the two hemispheres, a left-right split of the brain was used to compare hemisphere-specific distal cerebral arterial waveforms. From the FreeSurfer-based brain segmentation, arterial waveform samples were classified as belonging to the left or right hemisphere. Arterial cross sections located in proximity to the midline of the brain were difficult to assign to the left or right hemisphere. Therefore, cross sections up to 3.5 mm from the midline were excluded from the hemisphere-specific waveforms.

2D PCMRI external reference

As an external validation of the 4D flow MRI method’s ability to assess pulsatility in distal cerebral arteries, pulsatile flow was also measured with 2D PCMRI in proximal branches (ACA A2, MCA M1 and PCA P2) that feed the distal arteries. The software Segment v2.1 R5960 (http://medviso.com) was used to extract ROIs for the 2D PCMRI data. Combined magnitude and phase information was used to outline the ROI boundaries, and the same boundaries were used over all 32 timeframes of the cardiac cycle. A strategy that slightly overestimates the ROI boundaries was used during manual delineation of the ROIs.37 For each subject, time-resolved flow rates through all six segments were normalized through division by mean flow rate and averaged in order to construct a 2D PCMRI composite waveform. The composite waveform was used to provide reliable 2D PCMRI external reference pulsatility measures for evaluating the 4D flow MRI-derived distal pulsatility.

Pulsatility analysis

For the purpose of evaluating the 4D flow MRI method introduced in the present study, pulsatility index (PI) and resistivity index (RI) were used as quantitative measures to characterize the composite flow waveforms. In addition to the 4D flow MRI automatically derived distal arterial waveforms, indices were calculated for the hemisphere-specific 4D flow MRI waveforms, for the 4D flow MRI internal reference waveforms and for the 2D PCMRI external reference waveforms. To achieve this, waveforms were normalized through division by mean flow rate, and descriptive indices were calculated as

where represents the peak flow rate during systole and represents the minimum flow rate during diastole, in the normalized composite arterial waveforms.

Simulations of partial volume effects

The impact of partial volume effects (PVEs) on flow rate has been evaluated in a tapered phantom using 2D PCMRI, where a large overestimation could be seen as the flow path narrowed.38 However, to our knowledge, similar experiments have not been performed to evaluate the impact of PVEs on pulsatility. Therefore, this issue was investigated by simulating a high-resolution flow with sampling of k-space.39 The simulations were based on a constant magnitude difference between vessels and surrounding tissue, as inflow effects are absent in distal vessels when using 4D flow MRI. To simulate the effect of pulsations, a variable (sinusoidal) velocity and diameter through the cardiac cycle was applied. A maximal diameter dilation of 1.5% was assumed, based on the reports of diameter pulsations in pial arteries of hypertensive mice.19

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed in MATLAB (version 9.3.0. Natick, Massachusetts: The MathWorks Inc.). Intraclass correlation (ICC) and linear (Pearson) correlation were used to evaluate the agreement of distal arterial PI and RI against the 4D flow MRI internal reference values, against the 2D PCMRI external reference values, to compare distal PI and RI between the two hemispheres, and finally, to investigate the influence of age and blood pressure on distal arterial PI and RI. In these evaluations, an upper diameter of 1.25 mm was chosen as a suggested standard threshold, and P-values were calculated at a 0.05 significance level. No correction for multiple comparisons was used. A sample size of N = 12 was used for the internal reference and a sample size of N = 33 was used for the remaining correlations. To investigate the sensitivity to thresholding based on vessel size, intraclass correlation for distal PI and RI against the internal and external reference values was computed for a range of diameter thresholds (1–2 mm in steps of 0.01 mm). To investigate the influence of the number of cross sections used for the final calculation, random cross section selection was adopted for the 1.25 mm threshold, systematically increasing the number of sampled waveforms from which the final calculation was based on. The randomization process was performed with 1000 repeats.

Results

Waveform extraction

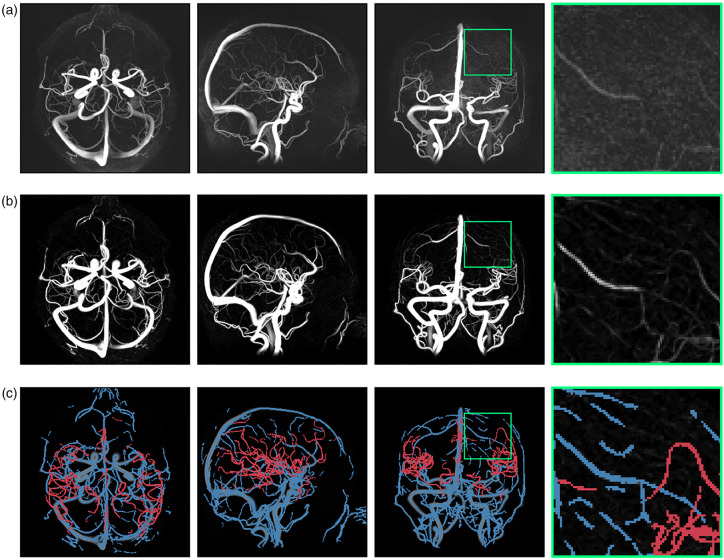

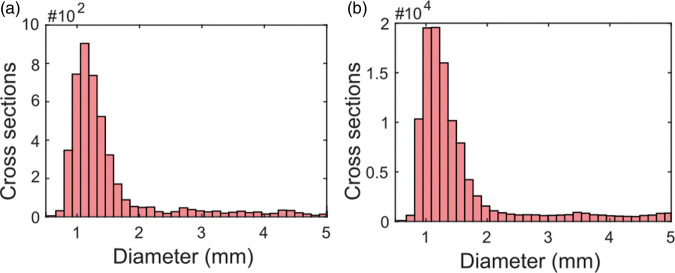

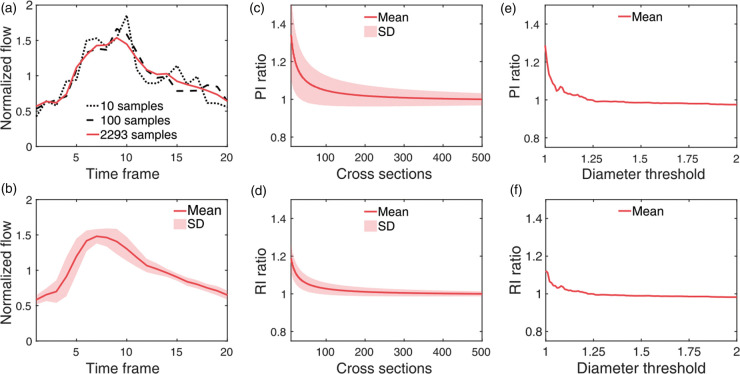

Distal cerebral arteries were successfully isolated using the proposed sequence of post-processing steps. 4D flow MRI-derived CD data processed by the vessel enhancement filter allowed for centerline-extraction, waveform-based clustering and diameter-based thresholding to isolate distal cerebral arteries (Figure 1). Analyzing the abundance of cerebral vessel cross sections by estimated diameter revealed a regime of rapid branching occurring below 2 mm, increasing the number of available arterial waveforms to be included in the global composite waveform (Figure 2). Composite distal arterial waveforms estimated from including all available distal cerebral arterial cross sections (diameter 0.75–1.25 mm) provided clear visibility of the systolic peak (Figure 3(a) and (b)). Waveforms for all (N = 33) participants are provided in the supplementary information (Suppl. Figure 2). The stability of the derived composite waveform was critically depending on the amount of included cross sections (Figure 3(a)), with lower amounts of cross sections leading to overestimations in PI (Figure 3(c)) and RI (Figure 3(d)). To reduce systematic overestimations below 5%, at least ∼90 cross sections for PI (Figure 3(c)) and ∼55 for RI (Figure 3(d)) were required. Similar systematic overestimations were also seen when choosing a too low diameter threshold (Figure 3(e) and (f)), as this limits the amount of available cross sections. Simulations of partial volume effects (PVEs) in distal vessels revealed a nearly linear increase in flow rate at each time point, indicating that PI and RI measures are still reliable, despite the flow errors caused by PVEs. Simulation results are provided in the supplementary information (Suppl. Figure 3).

Figure 1.

Segmentation of distal cerebral arteries. (a) Maximum intensity projections of a complex difference (CD) 4D flow MRI angiogram from an example subject. (b) Vessel enhancement filtered CD. (c) Small cerebral arteries of 0.75–1.25 mm in estimated diameter (red) separated from veins (using K-means clustering), extracerebral arteries and arteries larger than 1.25 mm (blue).

Figure 2.

Diameter distribution of cerebral vessels. (a) A regime of rapid branching is revealed below 2 mm for the example subject in Figure 1 and (b) when collapsing vessel diameters over all (N = 33) subjects.

Figure 3.

Waveform extraction. (a) Composite distal arterial waveform for the same subject as in Figure 1 when all available cerebral arterial cross sections are included (red) and based on a limited number of cross sections (black), leading to overestimations in PI and RI. (b) Subject averaged composite distal arterial waveform with standard deviation boundaries. (c–d) Mean overestimation ratios in PI and RI when sampling too few cross sections for the final waveform calculation (averaged over N = 33 subjects and 1000 trials of random sampling). The ratios correspond to overestimations in PI and RI in comparison to the PI and RI values obtained by including 500 cross sections for each participant. Note that the standard deviation boundaries in (c–d) are calculated from waveforms that are not independent between trials. (e–f) Mean overestimation ratios in PI and RI as a function of the upper diameter threshold in mm. The ratios correspond to overestimations in PI and RI in comparison to the PI and RI values obtained by using a threshold of 1.25 mm.

Comparisons with reference methods

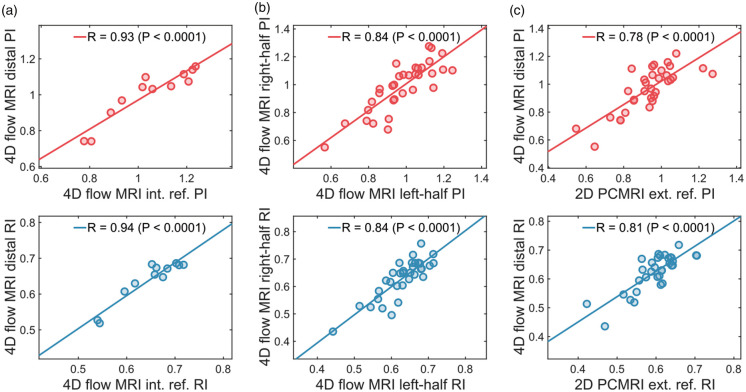

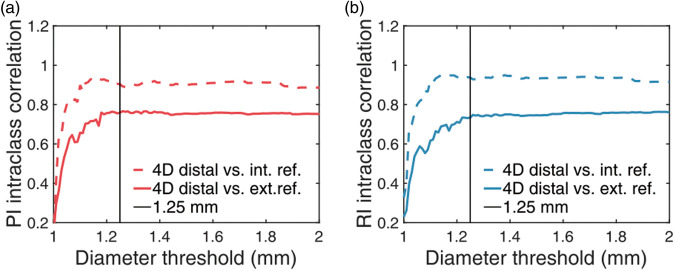

Average values of pulsatility and resistivity indices for all (N = 33) individuals were estimated to PI = 0.97 0.16 and RI = 0.62 0.06 for the 4D flow MRI distal measurements; PI = 1.04 0.16 and RI = 0.65 0.06 for the 4D flow MRI internal reference; PI = 0.93 0.14 and RI = 0.60 0.06 for the 2D PCMRI external reference. A Bland–Altman analysis comparing 4D flow MRI distal pulsatility measurements to external reference 2D PCMRI pulsatility measurements is provided in the supplementary information (Suppl. Figure 4). The 4D flow MRI distal arterial waveform was evaluated for agreement with the 4D flow MRI internal reference method for PI (ICC = 0.94, R = 0.94) and for RI (ICC = 0.94, R = 0.94) (Figure 4(a)). Hemisphere-specific waveforms were also compared in terms of PI (ICC = 0.83, R = 0.84) and RI (ICC = 0.83, R = 0.84) (Figure 4(b)) following the left-right split of the brain. Finally, the agreement with the 4D flow MRI distal arterial waveform and the 2D PCMRI external reference was evaluated for PI (ICC = 0.77, R = 0.78) and for RI (ICC = 0.74, R = 0.81) (Figure 4(c)). All of the above intraclass correlations and Pearson correlations were statistically significant (P’s < 0.001). A further investigation of the agreement with internal and external references as a function of diameter threshold indicated that the selection of threshold was not dramatically altering the performance unless set below 1.2 mm (Figure 5).

Figure 4.

Comparisons with reference methods. (a) Linear correlation between 4D flow MRI-derived distal pulsatility and 4D flow MRI internal reference pulsatility. (b) Linear correlation between hemisphere specific (left vs. right hemisphere) pulsatility. (c) Linear correlation between 4D flow MRI-derived distal pulsatility and 2D PCMRI external reference pulsatility.

Figure 5.

Evaluation of the diameter threshold. Intraclass correlation between 4D flow MRI-derived distal pulsatility and reference methods as a function of the diameter threshold. (a) Pulsatility index. (b) Resistivity index.

Relation to age and blood pressure

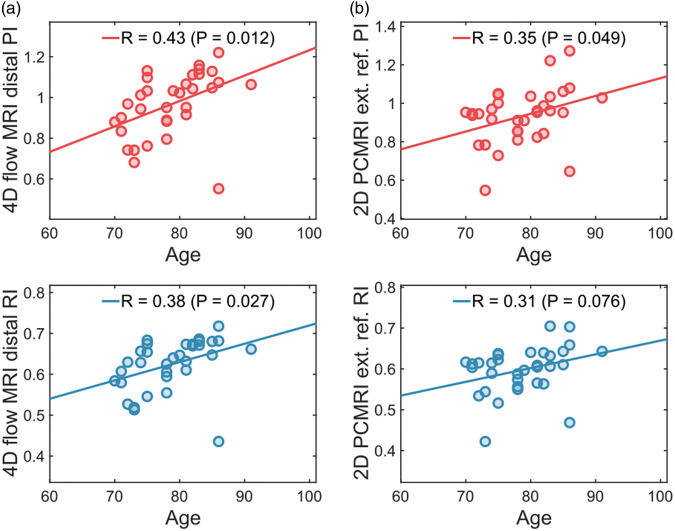

We also examined distal arterial pulsatility as a function of age. Using the 4D flow MRI-derived distal arterial pulsatility, positive significant correlations were observed both for PI (R = 0.43, P = 0.012) and for RI (R = 0.38, P = 0.027) (Figure 6(a)). The external reference method showed weaker and a borderline significant age-association for PI (R = 0.35, P = 0.049) and a non-significant age-association for RI (R = 0.31, P = 0.076) (Figure 6(b)). Finally, we examined the associations to systolic blood pressure (SBP), diastolic blood pressure (DBP) and pulse pressure (PP). Positive significant associations to SBP were observed for PI (R = 0.35, P = 0.044) and RI (R = 0.37, P = 0.036) and to PP for PI (R = 0.43, P = 0.012) and RI (R = 0.44, P = 0.011). For DBP, no significant association was found for PI (P = 0.77) or RI (P = 0.85).

Figure 6.

Relation to age. (a) Linear correlation between 4D flow MRI-derived distal pulsatility and age. (b) Linear correlation between 2D PCMRI external reference pulsatility and age.

Discussion

It is of increasing interest to develop non-invasive methods for early detection of exposure of distal brain vasculature to pulsatile stress. We report a novel method based on 4D flow MRI that finds and samples arteries from the entire detectable cerebral vasculature, in order to compute a global estimate of distal cerebral arterial pulsatility. The strength of the method was harnessed from the ability to sample and classify flow waveforms from thousands of cross sections originating from hundreds of small cerebral vessels, allowing substantial averaging in order to boost the limited velocity-to-noise levels in small arteries. Using the proposed approach, we were able to demonstrate a positive association between distal cerebral arterial pulsatility and age (despite examining a relatively narrow age span, 70–91 years). This observation is directly in line with the notion that aortic stiffness2,3 and pulsatility in cerebral arteries15,22 increase with age, leading to increased exposure of distal cerebral vasculature to pulsatile stress. The 4D flow MRI method appeared more sensitive compared to the external reference method in detecting this pulsatility-age association. Therefore, the proposed method is promising for early detection of exposure of distal brain vasculature to pulsatile stress, and can be used to advance research relating arterial pulsatility to neurodegeneration,4,13 white matter lesions,4,11 altered cerebrospinal fluid dynamics,19 global cerebrovascular reserve,40 cognitive decline4,8 and dementia.10,15

Pulsatility and resistivity measures in distal vasculature were found to perform well in relation to reference methods, using external measurements computed from averaging output from multiple 2D PCMRI acquisitions (Figure 4(c)) and using internal control measurements of well-defined distal arterial branches in the 4D flow MRI scans (Figure 4(a)). The left-right hemisphere split indicated that pulsatility was highly correlated between the two hemispheres (Figure 4(b)), supporting the concept of computing a global distal arterial waveform. Further, pulsatility in proximity to certain regions of the brain can potentially be achieved by breaking down the global indices into regional indices, using software for automatic cortical parcellation and subcortical segmentation. However, the accuracy of such a regionally specific analysis depends on the number of available cross sections in the confined region (Figure 3(c) and (d)) as well as the diameter distribution (Figure 3(e) and (f)). As our intention was to measure pulsatility in as small arteries as possible, we systematically evaluated the proposed method as a function of the diameter threshold (Figure 5), indicating that a threshold of 1.25 mm is suitable.

In both clinical and pre-clinical applications, TCD ultrasound has commonly been used as a convenient approach to quantify pulsatility in cerebral arteries. Two major drawbacks are dependencies on experienced operators and acoustic windows through the skull, restricting the access to potentially relevant distal cerebral vasculature. Pulsatile flow can also be studied using 2D PCMRI,38 where slices are manually placed by the operator, perpendicular to the arteries at the measurement planes of interest. This comes with the option to adapt the scan parameters for each individual slice. Customized 2D PCMRI in combination with a 7 T scanner has even made it possible to quantify pulsatility in the cerebral perforating arteries, using regional averaging over the acquisition planes.24,25 To use these types of acquisitions to quantify pulsatility in multiple sites is however time demanding, which is the major disadvantage of 2D PCMRI. In contrast, 4D flow MRI has the advantage of scanning the entire brain in a single acquisition, with a regular 3 T scanner and without operator dependency. This makes 4D flow MRI in combination with automated post-processing particularly suitable for retrieving cardiac-related waveforms in a large number of distal sites. Other novel and potentially relevant alternatives to well-established techniques are MRI sequences relying on the signal to quantify microvascular blood volume change over the cardiac cycle.26,27 A challenge in such approaches are low signal-to-noise levels, something that may be resolved using a contrast injection.27 Although time-resolved MRI generally put constraints on the signal-to-noise levels (because of subdividing available data into individual time frames), our proposed 4D flow MRI approach was able to obtain waveforms that appeared to be based on enough samples to produce a virtually noise-free representation of the distal cerebral arterial waveform (Suppl. Figure 2). Moreover, a comparison with other PCMRI based pulsatility studies indicates that the average pulsatility index in our study is reasonable in relation to previously reported values (Suppl. Table 1).

The present study has some limitations. As the 2D PCMRI external reference method was not suitable for sampling flow waveforms in thousands of orthogonal cut-planes, different measurement sites were used to obtain 4D flow MRI and 2D PCMRI pulsatility. In addition, the 2D PCMRI reference method used a manual segmentation technique37 and in contrast, the 4D flow MRI vessel planes were segmented automatically. Further, no direct evaluation was done for the K-means clustering-based separation of arteries and veins. Instead, a semi-automatic 4D flow MRI alternative based on manually drawn ROIs was used to evaluate the ability of K-means clustering and diameter thresholding to extract the arteries of interest. Another limitation is that 2D PCMRI and 4D flow MRI have different temporal resolution, and ways of sampling k-space and reconstructing the time-resolved images. This has implications for the ability to detect peak flow due to attenuation of high frequency components in the cardiac waveform,41 and absolute differences in pulsatility are therefore expected between 2D PCMRI and 4D flow MRI. This may partially explain why 2D PCMRI in feeding arteries measured a lower pulsatility than 4D flow MRI in distal arteries in the present study as evident from a Bland–Altman analysis (Suppl. Figure 4), despite the expected dampening effect.22 Potentially, more sophisticated reconstruction approaches (e.g. compressed sensing) could offer 4D flow MRI with a better temporal resolution.42 In addition to improving flow pulsatility estimations, this could lead to an opportunity to estimate an intracranial pulse wave velocity from proximal to distal cerebral arteries, by considering temporal shifts in the cardiac waveform and the distance to a reference point (e.g. the circle of Willis), for every arterial cross section. In the current implementation, such small temporal shifts were not considered, leading to some temporal smoothing of the flow waveforms (relevant for both 4D flow MRI and 2D PCMRI composite waveforms). For reference, a pulse wave velocity has been estimated to 499 79 cm/s between the common carotid artery (CCA) and the MCA, using TCD ultrasound.43 The spatial resolution in 4D flow MRI is also a limitation, corresponding to approximately one to two voxels per diameter in distal arteries. This makes it difficult to assure accurate in-plane segmentation, and partial volume effects (PVEs) are likely present in the individual samples. However, our simulation results showed that pulsatility and resistivity indices were nearly unaffected, since the relative shape of the pulsatile flow waveform remained nearly intact (Suppl. Figure 3).

In conclusion, we propose a high-resolution 4D flow MRI approach to automatically obtain a global characterization of pulsatility in distal cerebral arteries. Our measures indicated that distal cerebral arterial pulsatility significantly increased with age, highlighting its potential role in modifying microvascular integrity across the lifespan. The proposed approach can be used in future studies to explore the associations between excessive arterial pulsatility, brain deterioration, and the development of cognitive decline and dementia.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, JCB886667 Supplementary material for Characterizing pulsatility in distal cerebral arteries using 4D flow MRI by Tomas Vikner, Lars Nyberg, Madelene Holmgren, Jan Malm, Anders Eklund and Anders Wåhlin: for the Thrombolysis in Stroke Patients (TRISP) collaborators in Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism

Footnotes

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by The Swedish Research Council; Contract grant number: 2015-05616; The County Council of Västerbotten (both to A.E.); The Swedish Heart and Lung Foundation; Contract grant number: 20140592; The County Council of Västerbotten (both to J.M.); The Swedish Research Council; Contract grant number: 2017-04949; The County Council of Västerbotten (both to A.W.).

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Authors’ contributions: AW and TV conceived the project, developed the methods and performed the statistical analysis, with LN, JM and AE providing critical input; AW, MH, and AE designed the experiments and the external reference measurements; MH performed the external reference measurements; TV, LN, MH, JM, AE and AW wrote and edited the manuscript.

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1.Belz GG.Elastic properties and Windkessel function of the human aorta. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther 1995; 9: 73–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.O’Rourke MF, Hashimoto J.Mechanical factors in arterial aging. a clinical perspective. J Am Coll Cardiol 2007; 50: 1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.de Roos A, van der Grond J, Mitchell G, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of cardiovascular function and the brain. Circulation 2017; 135: 2178–2195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mitchell GF, Van Buchem MA, Sigurdsson S, et al. Arterial stiffness, pressure and flow pulsatility and brain structure and function: the age, gene/environment susceptibility – Reykjavik Study. Brain 2011; 134: 3398–3407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Avolio A, Kim MO, Adji A, et al. Cerebral haemodynamics: effects of systemic arterial pulsatile function and hypertension. Curr Hypertens Rep 2018; 20: 20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Palta P, Sharrett AR, Wei J, et al. Central arterial stiffness is associated with structural brain damage and poorer cognitive performance: the ARIC study. J Am Heart Assoc 2019; 8: e011045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wahlin A, Nyberg L.At the heart of cognitive functioning in aging. Trends Cogn Sci 2019; 23: 717–720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chiesa ST, Masi S, Shipley MJ, et al. Carotid artery wave intensity in mid- to late-life predicts cognitive decline: the Whitehall II study. Eur Heart J 2019; 40: 2300–2309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nilsson L-G, Adolfsson R, Bäckman L, et al. Betula: a prospective cohort study on memory, health and aging. Aging Neuropsychol Cogn 2004; 11: 134–148. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nation DA, Edmonds EC, Bangen KJ, et al. Pulse pressure in relation to tau-mediated neurodegeneration, cerebral amyloidosis, and progression to dementia in very old adults. JAMA Neurol 2015; 72: 546–553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Webb AJS, Simoni M, Mazzucco S, et al. Increased cerebral arterial pulsatility in patients with leukoaraiosis: arterial stiffness enhances transmission of aortic pulsatility. Stroke 2012; 43: 2631–2636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee S-H, Kim Y, Lee Y, et al. Pulsatility of middle cerebral arteries is better correlated with white matter hyperintensities than aortic stiffening. Ann Clin Neurophysiol 2018; 20: 79. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wåhlin A, Ambarki K, Birgander R, et al. Intracranial pulsatility is associated with regional brain volume in elderly individuals. Neurobiol Aging 2014; 35: 365–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chung CP, Lee HY, Lin PC, et al. Cerebral artery pulsatility is associated with cognitive impairment and predicts dementia in individuals with subjective memory decline or mild cognitive impairment. J Alzheimers Dis 2017; 60: 625–632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rivera-Rivera LA, Turski P, Johnson KM, et al. 4D flow MRI for intracranial hemodynamics assessment in Alzheimer’s disease. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2016; 36: 1718–1730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.de Montgolfier O, Pinçon A, Pouliot P, et al. High systolic blood pressure induces cerebral microvascular endothelial dysfunction, neurovascular unit damage, and cognitive decline in mice. Hypertens 2019; 73: 217–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bacyinski A, Xu M, Wang W, et al. The paravascular pathway for brain waste clearance: current understanding, significance and controversy. Front Neuroanat 2017; 11:101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bedussi B, Almasian M, de Vos J, et al. Paravascular spaces at the brain surface: low resistance pathways for cerebrospinal fluid flow. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2018; 38: 719–726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mestre H, Tithof J, Du T, et al. Flow of cerebrospinal fluid is driven by arterial pulsations and is reduced in hypertension. Nat Commun 2018; 9: 4878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gwilliam MN, Hoggard N, Capener D, et al. MR derived volumetric flow rate waveforms at locations within the common carotid, internal carotid, and basilar arteries. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2009; 29: 1975–1982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schubert T, Santini F, Stalder AF, et al. Dampening of blood-flow pulsatility along the carotid siphon: does form follow function? AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2011; 32: 1107–1112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zarrinkoob L, Ambarki K, Wahlin A, et al. Aging alters the dampening of pulsatile blood flow in cerebral arteries. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2016; 36: 1519–1527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shi Y, Thrippleton MJ, Blair GW, et al. Small vessel disease is associated with altered cerebrovascular pulsatility but not resting cerebral blood flow. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. Epub ahead of print 8 October 2018. DOI: 10.1177/0271678X18803956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bouvy WH, Geurts LJ, Kuijf HJ, et al. Assessment of blood flow velocity and pulsatility in cerebral perforating arteries with 7-T quantitative flow MRI. NMR Biomed 2016; 29: 1295–1304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Geurts LJ, Zwanenburg JJM, Klijn CJM, et al. Higher pulsatility in cerebral perforating arteries in patients with small vessel disease related stroke, a 7T MRI study. Stroke 2019; 50: 62–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shirzadi Z, Robertson AD, Metcalfe AW, et al. Brain tissue pulsatility is related to clinical features of Parkinson’s disease. Neuroimage Clin 2018; 20: 222–227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rivera-Rivera LA, Johnson KM, Turski PA, et al. Measurement of microvascular cerebral blood volume changes over the cardiac cycle with ferumoxytol-enhanced T2 (*) MRI. Magn Reson Med 2019; 81: 3588–3598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Markl M, Frydrychowicz A, Kozerke S, et al. 4D flow MRI. J Magn Reson Imag 2012; 36: 1015–1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gu T, Korosec FR, Block WF, et al. PC VIPR: a high-speed 3D phase-contrast method for flow quantification and high-resolution angiography. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2005; 26: 743–749. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wen B, Tian S, Cheng J, et al. Test-retest multisite reproducibility of neurovascular 4D flow MRI. J Magn Reson Imag 2019; 49: 1543–1552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wåhlin A, Ambarki K, Birgander R, et al. Measuring pulsatile flow in cerebral arteries using 4D phase-contrast MR imaging. Am J Neuroradiol 2013; 34: 1740–1745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schrauben E, Ambarki K, Spaak E, et al. Fast 4D flow MRI intracranial segmentation and quantification in tortuous arteries. J Magn Reson Imaging 2015; 42: 1458–1464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dunas T, Holmgren M, Wahlin A, et al. Accuracy of blood flow assessment in cerebral arteries with 4D flow MRI: evaluation with three segmentation methods. J Magn Reson Imaging 2019; 50: 511–518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Malm J, Jacobsson J, Birgander R, et al. Reference values for CSF outflow resistance and intracranial pressure in healthy elderly. Neurology 2011; 76: 903–909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fischl B, Salat DH, Busa E, et al. Whole brain segmentation: automated labeling of neuroanatomical structures in the human brain. Neuron 2002; 33: 341–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jerman T, Pernuš F, Likar B, et al. Enhancement of vascular structures in 3D and 2D angiographic images. IEEE Trans Med Imaging 2016; 35: 2107–2118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jiang J, Kokeny P, Ying W, et al. Quantifying errors in flow measurement using phase contrast magnetic resonance imaging: comparison of several boundary detection methods. Magn Reson Imaging 2015; 33: 185–193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wåhlin A, Ambarki K, Hauksson J, et al. Phase contrast MRI quantification of pulsatile volumes of brain arteries, veins, and cerebrospinal fluids compartments: repeatability and physiological interactions. J Magn Reson Imaging 2012; 35: 1055–1062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Moran PR.A flow velocity zeugmatographic interlace for NMR imaging in humans. Magn Reson Imaging 1982; 1: 197–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.DuBose LE, Boles Ponto LL, Moser DJ, et al. Higher aortic stiffness is associated with lower global cerebrovascular reserve among older humans. Hypertens 2018; 72: 476–482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Polzin JA, Frayne R, Grist TM, et al. Frequency response of multi-phase segmented k-space phase-contrast. Magn Reson Med 1996; 35: 755–762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lustig M, Donoho D, Pauly JM.Sparse MRI: the application of compressed sensing for rapid MR imaging. Magn Reson Med 2007; 58: 1182–1195. doi:10.1002/mrm.21391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fu X, Huang C, Wong KS, et al. A new method for cerebral arterial stiffness by measuring pulse wave velocity using transcranial Doppler. J Atheroscler Thromb 2016; 23: 1004–1010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, JCB886667 Supplementary material for Characterizing pulsatility in distal cerebral arteries using 4D flow MRI by Tomas Vikner, Lars Nyberg, Madelene Holmgren, Jan Malm, Anders Eklund and Anders Wåhlin: for the Thrombolysis in Stroke Patients (TRISP) collaborators in Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism