Abstract

Background

Previous meta-analysis had evaluated the effect of induction chemotherapy in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. But two trials with opposite findings were not included and the long-term result of another trial significantly differed from the preliminary report. This updated meta-analysis was thus warranted.

Methods

Literature search was conducted to identify randomized controlled trials focusing on the additional efficacy of induction chemotherapy in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Trial-level pooled analysis of hazard ratio (HR) for progression free survival and overall survival and risk ratio (RR) for locoregional control rate and distant control rate were performed.

Results

Twelve trials were eligible. The addition of induction chemotherapy significantly prolonged both progression free survival (HR=0.68, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.60–0.76, p<0.001) and overall survival (HR=0.67, 95% CI 0.54–0.80, p<0.001), with 5-year absolute benefit of 11.31% and 8.95%, respectively. Locoregional (RR=0.80, 95% CI 0.70–0.92, p=0.002) and distant control (RR=0.70, 95% CI 0.62–0.80) rates were significantly improved as well. The incidence of grade 3–4 adverse events during the concurrent chemoradiotherapy was higher in leukopenia (p=0.028), thrombocytopenia (p<0.001), and fatigue (p=0.038) in the induction chemotherapy group.

Conclusions

This meta-analysis supported that induction chemotherapy could benefit patients with nasopharyngeal carcinoma in progression free survival, overall survival, locoregional, and distant control rate.

Keywords: induction chemotherapy, meta-analysis, nasopharyngeal carcinoma, radiotherapy, updated

Introduction

Nasopharyngeal carcinoma is an epithelial carcinoma arising from the nasopharyngeal mucosal lining. It is a common head and neck carcinoma in east and southeast Asia, especially in south China (1). Resulting from the non-specific symptom in early-stage disease and the absence of regular examination of nasopharynx or effective screening, almost 70% of patients have locoregionally advanced disease at the initial diagnosis (2). Radiotherapy is known to be the primary treatment approach, but it has relatively poor disease control for locoregionally advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma. The randomized trial was initiated in 1989 to test the added value of induction chemotherapy before radiotherapy (3), and finally improved disease free survival was observed but not overall survival. As the new induction chemotherapy regimen of docetaxel and cisplatin led to significant benefit of overall survival for patients from endemic area in a phase II trial (4), more clinicians and researchers were concerned with induction chemotherapy. But what the subsequent trials (5–8) found was not always the same. A recent meta-analysis (9) concluded that induction chemotherapy had the potential to improve both progression free survival and overall survival, but it did not include another two large scale and possibly equally-weighted trials (10, 11), in which the result of induction chemotherapy on overall survival was inconsistent. Moreover, the long-term results (12, 13) of another two previous trials (7, 8) deserved great concern, especially the distinctive finding of induction chemotherapy of cisplatin and fluorouracil in 5-year overall survival (13). Therefore, an updated meta-analysis is warranted.

Methods

Identification of Trials and Extraction of Data

The electronic databases including PubMed, Cochrane Library, Embase, and Web of Science were searched to identify randomized controlled trials focusing on nasopharyngeal carcinoma or nasopharyngeal cancer, induction chemotherapy or neoadjuvant chemotherapy, and radiotherapy. Trials were eligible if investigating the benefit of induction chemotherapy before radiotherapy or concurrent chemoradiotherapy alone in locoregional advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma patients.

Information of included trials was extracted, including study design, cancer staging, number of patients, year, end points, treatment protocol, follow-up duration, failure patterns and grade 3 or 4 acute toxic effects.

Statistical Analysis

Overall, the role of induction chemotherapy in progression free survival (time from random assignment to locoregional failure, distant metastasis, or death from any cause) and overall survival (time from random assignment to death from any cause) was investigated by meta-analysis of the results of diverse trials. Hazard ratios with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of individual trials were pooled if reported, or these were estimated as elucidated by Tierney and colleagues (14). Survival curves of pooled progression free survival and overall survival were drawn, and absolute differences between induction chemotherapy group and control group were computed as recommended by Pignon and colleagues (15). According to the method described by Tierney and Pignon, corresponding survival probability and effective number event-free of each clinical trial were obtained from the Kaplan–Meier curve at the time point of 0/12/24/36/48/60 month. And the weight of each clinical trial was also estimated. Therefore, the total survival probability of the study group and control group at each time point could be calculated. However, the role of induction chemotherapy in locoregional control and distant control was evaluated by pooling the risk ratios (RRs) with 95% CIs using the Mantel–Haenszel method (16) instead of time-dependent locoregional relapse free survival and distant metastasis free survival, because the data of hazard ratios and 95% CIs were not available at all by direct or indirect methods in certain trials. Severe acute toxicities were also pooled if available. Notably, only the data of long-term results were included for analysis. Estimation was based on random effect model in case of heterogeneity [p value of χ2 test <0.1 or I2 statistic > 50% (17)], or else fixed effect model. Finally, Begg’s test (18) and Egger’s test (19) were conducted to find potential publication bias. If publication bias was detected, the Duval and Tweedie nonparametric “trim and fill” procedure (20) was subsequently performed to further assess the possible effect.

Data analyses were done using R version 3.5.2 and Stata version 12.0 (Statacorp LP, College Station, Texas, USA). Two-sided p<0.05 was considered significant for all analyses except heterogeneity tests.

Result

Trials Information

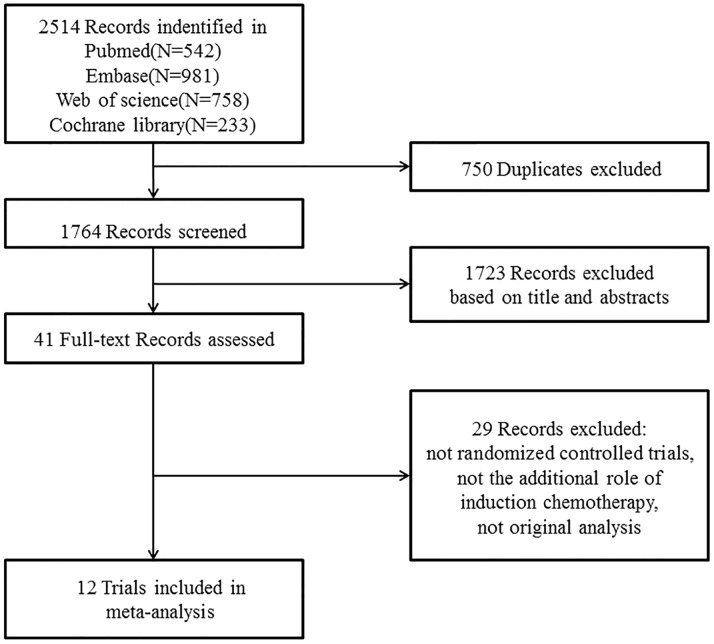

A total of 12 randomized controlled trials (3–8, 10–13, 21–24) (3,586 patients, shown in Table 1 ) were finally eligible for this meta-analysis as the literature search and trial selection ( Figure 1 ) were completed. Notably, there were seven large scale trials (3, 7, 8, 10–13, 21, 22) with more than 300 participants and only three trials (4, 23, 24) enrolled fewer than 100 patients in each; 2,942 (82.04%) patients of eight trials (4, 6–8, 10–13, 21, 22) were from endemic area; two trials (7, 8) recently updated the long-term results (12, 13) and thus only one trial (21) had a median follow-up time less than three years; seven trials (4, 6–8, 10–13, 24) delivered intensity-modulated radiotherapy technique and eight trials (4–8, 10–13, 24) administrated concurrent chemotherapy of cisplatin to patients during the process of radiotherapy.

Table 1.

Summary of included studies.

| Studies | No. of patients | Stage | Inclusion period | Median follow up (m) | Radiotherapy | Induction chemotherapy | Concurrent chemotherapy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cvitkovic et al. (3) | 339 | UICC any T, N2-3 | 1989–1993 | 49 | 2DRT:2.0Gy/f to 65–70Gy | 3* BLM15mg bolus (d1)+12mg/m2/d(d1-5) +epirubicin70mg/m2(d1) +DDP 100mg/m2 (d1) | None |

| Chua et al. (21) | 334 | Ho’s stage III/IV and N≥3cm | 1989–1993 | 30 | 2DRT:60–66Gy and additional boost for residual LNs, hypofractionated RT for most | 2-3*epirubicin110mg/m2 +DDP60mg/m2 | None |

| Ma et al. (22) | 456 | Chinese 1992 III–IV | 1993–1994 | 62 | 2DRT:2.0Gy/f, to 68–72Gy and additional boost to 80Gy if residual | 2-3* DDP100mg/m2(d1) +FU 800 mg/m2/d(d1-5) +BLM 10mg/m2/d(d1, d5) | None |

| Hareyama et al. (23) | 80 | All stages M0 | 1991–1998 | 49 | 2DRT:2.0–2.2Gy/f to 66–68Gy | 2*DDP80mg/m2(d1) +FU800mg/m2(d1-4) | None |

| Hui et al. (4) | 65 | UICC1997 III–IVB | 2002–2004 | 51.6 | 2DRT/3DCRT/IMRT:2Gy/f to 66Gy; residual boost of 7.5Gy, parapharyngeal boost of 20Gy | 2*docetaxel75mg/m2

+DDP75mg/m2, q3w |

8*DDP40 mg/m2 weekly |

| Fountzilas et al. (5) | 144 | UICC2002 IIB–IVB | 2003–2008 | 55 | 2DRT/3DCRT:2.0Gy/f/to 66–70 Gy | 3*epirubicin75mg/m2(d1) +paclitaxel175mg/m2(d1) +DDP75 mg/m2(d2), q3w | DDP 40 mg/m2 weekly |

| Tan et al. (6) | 172 | UICC1997 III–IVB |

2004–2012 | 40.8 | 2DRT:70Gy/35f; IMRT:69.96Gy/33f | 3*paclitaxel70mg/m2 +carboplatin (AUC=2.5) +gemcitabine1000mg/m2, q3w | DDP 40 mg/m2 weekly |

| Sun et al. (7) Li et al. (12) | 480 | 7th UICC III–IVB (except T3-4N0) |

2011–2013 | 71.5 | IMRT:2–2.35Gy/f to ≥66Gy | 3*docetaxel60mg/m2(d1)+DDP60mg/m2(d1)+ 5FU600mg/m2(d1-5), q3w |

DDP 100 mg/m2 q3w |

| Cao et al. (8) Yang et al. (13) | 476 | 6th UICC III–IVB (except T3N0-1) |

2008–2015 | 82.6 | 2DRT/IMRT: 2–2.33Gy/f to 64–72Gy | 2*DDP80mg/m2(d1) +FU800mg/m2/d(d1-5), q3w |

DDP 80 mg/m2 q3w |

| Frikha et al. (24) | 81 | UICC2002 T2b-4 and/or N1-3 |

2009–2015 | 43.1 | IMRT/non-IMRT 70Gy/35f | 3*Docetaxel75mg/m2(d1)+ DDP75mg/m2(d1)+ 5FU750mg/m2(d1-5), q3w |

DDP 40 mg/m2 weekly |

| Hong et al. (10) | 479 | 5th UICC IVa–IVB |

2003–2009 | 72.0 | 1.8-2.2Gy/f, 5f/week, ≥70 Gy to the primary tumor, 66–70Gy to the involved neck | 3*mitomycin8mg/m2, epirubicin60mg/m2+DDP60mg/m2,D1, 5-FU450mg/m2+ leucovorin30mg/m2,D8, q3w |

DDP30mg/m2 weekly |

| Zhang et al. (11) | 480 | 7th UICC III–IVb, except N0 | 2013–2016 | 42.7 | IMRT 66–70Gy/30–33f | 3*(gemcitabine 1g/m2,d1,d8+ DDP80mg/m2,d1),q3w |

DDP100 mg/m2 q3w |

UICC, International Union Against Cancer; BLM, bleomycin; f, fraction; LN, lymph node; civ, continuous intravenous; DDP, cisplatin; FU, fluorouracil; 2DRT, two-dimensional radiotherapy; 3DCRT, three-dimensional conformal radiotherapy; IMRT, intensity-modulated radiotherapy.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram.

Progression Free Survival and Overall Survival

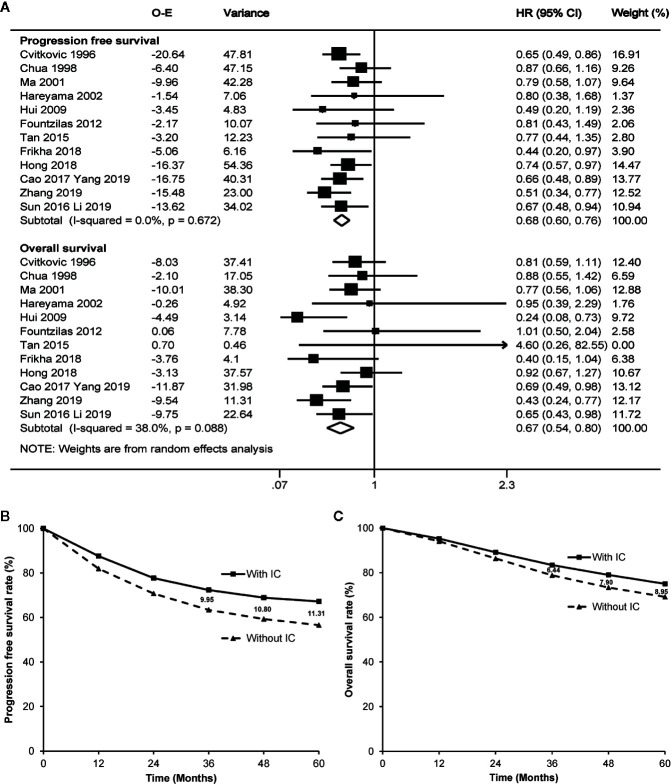

Seven trials (4, 6, 10–13, 24) directly reported the original hazard ratio with 95% CI of progression free survival and overall survival. Based on the random effect model (potential heterogeneity for overall survival with a p value of 0.088 by χ2 test), meta-analysis highly favored induction chemotherapy, with a hazard ratio of 0.68 (95% CI 0.60–0.76, p<0.001) for progression free survival and a hazard ratio of 0.67 (95% CI 0.54–0.80, p<0.001) for overall survival ( Figure 2A ). The addition of induction chemotherapy before radiotherapy alone or concurrent chemoradiotherapy showed the potential to enhance the 3-year, 4-year, and 5-year progression free survival by 9.95%, 10.80%, and 11.31% ( Figure 2B ), and prolong 3-year, 4-year, and 5-year overall survival by 6.44%, 7.90%, and 8.95%, respectively ( Figure 2C ). No publication bias was observed by Egger’s test or Begg’s test (p≥0.217).

Figure 2.

Forest plot (A) and estimated survival curves (B, C) for progression free survival and overall survival. The numbers on the figure (B, C) mean absolute increase of the survival rates. IC, induction chemotherapy; O-E, observed minus estimated number of events; CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio.

To be more careful, sensitivity analysis was conducted by excluding the four trials without concurrent chemotherapy during the phase of radiotherapy, as radiotherapy alone is no longer recommended in the clinical practice. As a result, induction chemotherapy followed by concurrent chemoradiotherapy remained the advantage of progression free survival (hazard ratio 0.64, 95% CI 0.54–0.74, p<0.001) and overall survival (hazard ratio 0.59, 95% CI 0.41–0.77, p<0.001) over concurrent chemoradiotherapy alone.

Locoregional and Distant Control Rate

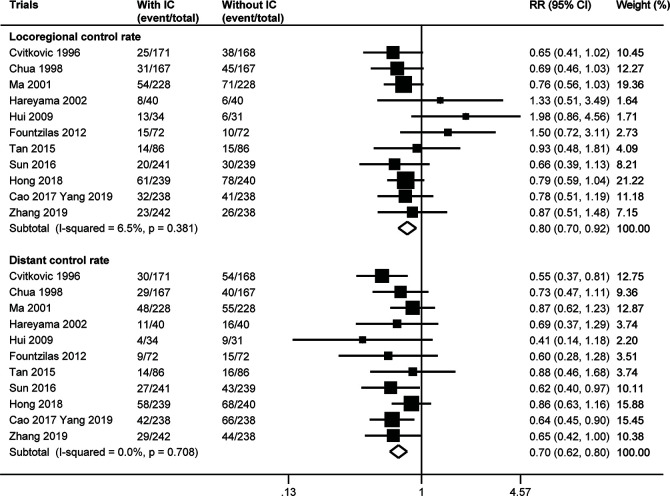

The number of locoregional or distant failure was not available in the trial by Frikha et al. (24). Meta-analysis of the other 11 trials indicated that the addition of induction chemotherapy could significantly lower the risk of both locoregional and distant failure. The fixed effect model (no heterogeneity with p≥0.381 by χ2 test) showed a pooled risk ratio of 0.80 (95% CI 0.70–0.92, p=0.002) for locoregional control rate and a risk ratio of 0.70 (95% CI 0.62–0.80) for distant control rate ( Figure 3 ). There was no evidence of publication bias for distant control rate (p≥0.185), but Egger’s test (p=0.023) and Begg’s test (p=0.024) both showed publication bias for locoregional control rate. When three theoretical missing studies were incorporated using the “trim and fill” analysis, the improved locoregional control rate resulting from the additional induction chemotherapy remained with a risk ratio of 0.75 (95% CI 0.63–0.91, p=0.003) by random effect meta-analysis (potential heterogeneity with a p value of 0.067 by χ2 test).

Figure 3.

Forest plot for locoregional control rate and distant control rate. IC, induction chemotherapy; CI, confidence interval; RR, risk ratio.

Severe Toxicities

The main toxicities of induction chemotherapy varied by the individual regimen. Severe hematologic adverse events were not uncommon, especially neutropenia (32.74%) and leukopenia (11.94%). Unfortunately, patients were more likely to suffer from leukopenia (p=0.028), thrombocytopenia (p<0.001), and fatigue (p=0.038) during the radiotherapy phase if they had received induction chemotherapy before ( Table 2 ).

Table 2.

Grade 3 or 4 acute toxic effects.

| Cvitkovic et al. (3) | Chua et al. (21) | Ma et al. (22) | Hareyama et al. (23) | Hui et al. (4) | Fountzilas et al. (5) | Tan et al. (6) | Sun et al. (7) | Cao et al. (8) | Frikha et al. (24) | Hong et al. (10) | Zhang et al. (11) | Incidence (95% CI) or risk ratio (95% CI) with p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Induction chemotherapy phase (No.) | |||||||||||||

| Total | 162 | 155 | 219 | 40 | 34 | 63 | 86 | 239 | 238 | 40 | 237 | 239 | |

| Anemia | NA | 3 | 6 | NA | NA | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | NA | 16 | 4 | 1.62% (0.79%–3.28%) |

| Leukopenia | NA | 4 | 8 | NA | NA | NA | 16 | 65 | 12 | NA | 139 | 26 | 11.94% (4.80%–26.73%) |

| Thrombocytopenia | NA | 0 | 3 | 3 | NA | NA | 0 | 0 | 0 | NA | 66 | 13 | NA |

| Nausea/vomiting | 49.0 | 42 | 28 | 11 | 3 | 4 | 0 | 18 | 10 | NA | 42 | 48 | 12.88% (7.33%–19.65%) |

| Neutropenia | NA | NA | NA | 3 | 33 | 6 | 50 | 85 | 35 | 11 | NA | 49 | 32.74% (17.74%–49.82%) |

| Febrile neutropenia | 6.0 | 10 | NA | NA | 4 | NA | NA | 4 | NA | 3 | 10 | NA | 4.10% (2.08%–6.13%) |

| Fatigue | NA | NA | NA | NA | 2 | 1 | 0 | NA | NA | 4 | NA | NA | 2.07% (0–5.06%) |

| Hair loss | NA | 41 | NA | NA | NA | 40 | 0 | NA | NA | 6 | NA | NA | 20.98% (1.29%–53.74%) |

| renal toxicity | 9.0 | NA | NA | 0 | NA | NA | NA | 0 | 0 | NA | 0 | 3 | NA |

| Hepatoxicity | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 2 | 6 | 2 | NA | 3 | 5 | 1.45% (0.73%–2.18%) |

| Diarrhea | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 19 | 1 | NA | NA | 1 | NA |

| Toxic death | NA | 2 | 0 | 0 | NA | NA | NA | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | NA |

| Radiotherapy phase (No.) | |||||||||||||

| Total | 147vs161 | 155vs152 | 219vs221 | 39vs40 | 34vs26 | 63vs70 | 86vs86 | 239vs238 | 238vs238 | 40vs 1 | 237vs227 | 239vs237 | |

| Anemia | NA | NA | NA | NA | 3vs5 | 3vs0 | 2vs2 | 4vs5 | 23vs9 | NA | 23vs2 | 19vs2 | 2.38 (0.92–6.11), p=0.072 |

| Leukopenia | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 16vs21 | 45vs32 | 98vs41 | 45vs34 | NA | 70vs32 | 47vs48 | 1.44 (1.04–1.98), p=0.028 |

| Thrombocytopenia | NA | NA | NA | NA | 3vs1 | 10vs1 | 12vs0 | 6vs2 | 4vs2 | NA | 78vs2 | 17vs3 | 6.77 (2.57–17.79), p<0.001 |

| Neutropenia | NA | NA | NA | NA | 9vs4 | 4vs8 | 21vs10 | 101vs17 | 24vs20 | NA | NA | 28vs25 | 1.67 (0.83–3.37), p=0.154 |

| Febrile neutropenia | NA | NA | NA | NA | 1vs1 | 0vs1 | NA | 7vs0 | NA | NA | 3vs2 | 1vs0 | 2.38 (0.89–6.35), p=0.085 |

| Fatigue | NA | NA | NA | NA | 5vs2 | 0vs2 | 12vs2 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 2.54 (1.05–6.13), p=0.038 |

| Nausea/vomiting | NA | NA | NA | NA | 3vs2 | 13vs13 | 2vs3 | 106vs85 | 25vs21 | NA | 17vs30 | 85vs66 | 1.13 (0.97–1.32), p=0.105 |

| Hepatoxicity | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 1vs0 | 7vs2 | 1vs3 | NA | 6vs3 | 1vs0 | 1.86 (0.83–4.15), p=0.131 |

| Mucositis | 27vs33 | NA | NA | NA | 8vs2 | 33vs38 | 1vs0 | 98vs84 | 16vs12 | NA | 82vs102 | 67vs76 | 0.96 (0.85–1.08), p=0.482 |

| Toxic death | 14vs2 | NA | 0vs1 | 0vs1 | NA | NA | NA | 0vs0 | 0vs0 | NA | 0vs2 | 0vs0 | 0.88 (0.10–7.36), p=0.903 |

NA, not available; CI, confidence interval.

Discussion

This updated meta-analysis further confirmed the benefit of induction chemotherapy in improving progression free survival, overall survival, locoregional control, and distant control of nasopharyngeal carcinoma, based on all the currently published randomized controlled trials. Obviously, 66.28% (2,377 patients) of patients in this meta-analysis were delivered with concurrent chemoradiotherapy, which has been the standard therapy for locoregionally advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma now; 46.26% (1,659 patients) of patients received intensity-modulated radiotherapy, which has been the primary radiation technique; 82.04% (2,942 patients) of patients were from an endemic area, which increased the applicability and practicability of the result in the real world; the median follow-up time of 52.73% (1,891 patients) of patients in four trials (10, 12, 13, 22) were longer than 60 months, which meant that the result of according meta-analysis was more likely to be robust.

The estimated overall absolute benefit of induction chemotherapy in progression free survival and overall survival provided reference basis for sample size estimation in the future randomized controlled trials. The absolute 5-year survival benefit of 11.31% in progression free survival and 8.95% in overall survival were higher than those of concurrent chemotherapy (6.6% in progression free survival and 5.3% in overall survival) or adjuvant chemotherapy (6.1% in progression free survival and 3.3% in overall survival) alone, but inferior to concurrent chemotherapy plus adjuvant chemotherapy (12.4% in progression free survival and 12.4% in overall survival), as reported in the previous meta-analysis (25). Since the high benefit of concurrent chemotherapy plus adjuvant chemotherapy was the result of taking radiotherapy alone as the control (25), induction chemotherapy thus seemed to be the most effective treatment approach. Local control and distant failure rates are, as overall survival and progression free survival, dependent on follow-up. Even if the trials are randomized with comparable follow-up in both arms, the analyses are less worthwhile than those for progression free survival and overall survival.

Overall, these trials administrated cisplatin-based induction chemotherapy regimen, with the combination of epirubicin or taxanes. In comparison with the counterparts, the former combination regimen brought about no benefit in overall survival, even in progression free survival or distant control rate for a total of more than 600 participants in the four large-scale trials (3, 5, 10, 21). Conversely, the combination of taxanes and cisplatin with or without other drugs did seem to be more effective (4, 7, 12), even though negative results were also observed in another small trial by Frikha and colleagues (24). Since this trial (24) was closed prematurely due to poor accrual, less than one third of estimated patients were actually enrolled. Perhaps it was the lack of statistic power, instead of the induction chemotherapy regimen itself, that caused the false negative finding of similar survival rate between the induction chemotherapy plus concurrent chemoradiotherapy arm and concurrent chemoradiotherapy arm in the trial (24). The newest induction chemotherapy of gemcitabine and cisplatin (11) showed highly promising results, with absolute survival benefit of 8.8% in 3-year failure free survival and 4.3% in overall survival, which appeared to be even more effective than the regimen of docetaxel, cisplatin, and fluorouracil (7). The effect of the combination of gemcitabine and cisplatin was also observed in recurrent or metastatic nasopharyngeal carcinoma (26). Certainly, another trial (6) with gemcitabine-based induction chemotherapy did not find survival improvement. This may be correlated with the combined drug of carboplatin instead of cisplatin and possible low statistic power caused by insufficient sample size resulting from overestimation of the effect of induction chemotherapy. Apart from the newly induction chemotherapy regimens, more precise eligibility criteria may be another reason for the positive efficiency of induction chemotherapy in the recent trials. As the sixth or seventh edition of AJCC/UICC staging system more effectively stratifies patients than the prior editions (27–29) and the application of magnetic resonance imaging together with fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography more precisely staged the disease than computed tomography (30, 31), the recent trials, no wonder, more possibly enrolled high-risk patients and accordingly observed survival benefit of induction chemotherapy.

As seen in Table 2 , induction chemotherapy itself caused common severe hematologic toxicities and meanwhile lowered the tolerance of patients to the followed concurrent chemoradiotherapy. One trial (32) showed the possibility of omitting concurrent chemotherapy after induction chemotherapy, but before more strong evidence is available, it is still the most reassuring and satisfactory if the addition of induction chemotherapy would not significantly bring down the intensity of concurrent chemoradiotherapy. Given that not all the locoregionally advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma patients could achieve benefit from induction chemotherapy (33–35), precise selection of high-risk patients (36, 37) could be another valuable way to further enhance the magnitude of absolute benefit, apart from the exploration of newly induction chemotherapy regimen.

Conclusion

Induction chemotherapy resulted in significant benefit in progression free survival, overall survival, locoregional control, and distant control for patients with nasopharyngeal carcinoma.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Author Contributions

Study concept and design: F-YX, P-YO, FH. Literature retrieval: S-SY. Data acquisition: S-SY, J-GG, J-NL, Z-QL, E-NC, C-YC. Data analysis and interpretation: S-SY, P-YO, J-GG, J-NL. Manuscript preparation and editing: S-SY, P-YO. Critical revisions: all authors. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This work was supported by the Sun Yat-sen University Clinical Research 5010 Program (2015020), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81672665), the Sci-Tech Project Foundation of Guangdong Province (2016A020215087), and the Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province (2019A1515010300), Medical Scientific Research Foundation of Guangdong Province, China (Granted No. A2016197).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- 1. Cao SM, Simons MJ, Qian CN. The prevalence and prevention of nasopharyngeal carcinoma in China. Chin J Cancer (2011) 30(2):114–9. 10.5732/cjc.010.10377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. OuYang PY, Su Z, Ma XH, Mao YP, Liu MZ, Xie FY. Comparison of TNM staging systems for nasopharyngeal carcinoma, and proposal of a new staging system. Br J Cancer (2013) 109(12):2987–97. 10.1038/bjc.2013.659 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cvitkovic E, Eschwege F, Rahal M, SK O. Preliminary results of a randomized trial comparing neoadjuvant chemotherapy (cisplatin, epirubicin, bleomycin) plus radiotherapy vs. radiotherapy alone in stage IV(> or = N2, M0) undifferentiated nasopharyngeal carcinoma: a positive effect on progression-free survival. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys (1996) 35(3):463–9. 10.1016/S0360-3016(96)80007-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hui EP, Ma BB, Leung SF, King AD, Mo F, Kam MK, et al. Randomized phase II trial of concurrent cisplatin-radiotherapy with or without neoadjuvant docetaxel and cisplatin in advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma. J Clin Oncol (2009) 27(2):242–9. 10.1200/jco.2008.18.1545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Fountzilas G, Ciuleanu E, Bobos M, Kalogera-Fountzila A, Eleftheraki AG, Karayannopoulou G, et al. Induction chemotherapy followed by concomitant radiotherapy and weekly cisplatin versus the same concomitant chemoradiotherapy in patients with nasopharyngeal carcinoma: a randomized phase II study conducted by the Hellenic Cooperative Oncology Group (HeCOG) with biomarker evaluation. Ann Oncol (2012) 23(2):427–35. 10.1093/annonc/mdr116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Tan T, Lim WT, Fong KW, Cheah SL, Soong YL, Ang MK, et al. Concurrent chemo-radiation with or without induction gemcitabine, Carboplatin, and Paclitaxel: a randomized, phase 2/3 trial in locally advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys (2015) 91(5):952–60. 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2015.01.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sun Y, Li WF, Chen NY, Zhang N, Hu GQ, Xie FY, et al. Induction chemotherapy plus concurrent chemoradiotherapy versus concurrent chemoradiotherapy alone in locoregionally advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma: a phase 3, multicentre, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol (2016) 17(11):1509–20. 10.1016/S1470-2045(16)30410-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cao SM, Yang Q, Guo L, Mai HQ, Mo HY, Cao KJ, et al. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by concurrent chemoradiotherapy versus concurrent chemoradiotherapy alone in locoregionally advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma: A phase III multicentre randomised controlled trial. Eur J Cancer (Oxford Engl 1990) (2017) 75:14–23. 10.1016/j.ejca.2016.12.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. OuYang PY, Zhang XM, Qiu XS, Liu ZQ, Lu L, Gao YH, et al. A Pairwise Meta-Analysis of Induction Chemotherapy in Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma. Oncologist (2019) 24(4):505–12. 10.1634/theoncologist.2018-0522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hong RL, Hsiao CF, Ting LL, Ko JY, Wang CW, Chang JTC, et al. Final results of a randomized phase III trial of induction chemotherapy followed by concurrent chemoradiotherapy versus concurrent chemoradiotherapy alone in patients with stage IVA and IVB nasopharyngeal carcinoma-Taiwan Cooperative Oncology Group (TCOG) 1303 Study. Ann Oncol (2018) 29(9):1972–9. 10.1093/annonc/mdy249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Zhang Y, Chen L, Hu GQ, Zhang N, Zhu XD, Yang KY, et al. Gemcitabine and Cisplatin Induction Chemotherapy in Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma. N Engl J Med (2019) 381(12):1124–35. 10.1056/NEJMoa1905287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Li WF, Chen NY, Zhang N, Hu GQ, Xie FY, Sun Y, et al. Concurrent chemoradiotherapy with/without induction chemotherapy in locoregionally advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma: Long-term results of phase 3 randomized controlled trial. Int J Cancer (2019) 145(1):295–305. 10.1002/ijc.32099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Yang Q, Cao SM, Guo L, Hua YJ, Huang PY, Zhang XL, et al. Induction chemotherapy followed by concurrent chemoradiotherapy versus concurrent chemoradiotherapy alone in locoregionally advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma: long-term results of a phase III multicentre randomised controlled trial. Eur J Cancer (Oxford Engl 1990) (2019) 119:87–96. 10.1016/j.ejca.2019.07.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Tierney JF, Stewart LA, Ghersi D, Burdett S, Sydes MR. Practical methods for incorporating summary time-to-event data into meta-analysis. Trials (2007) 8:16. 10.1186/1745-6215-8-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Pignon JP, Hill C. Meta-analyses of randomised clinical trials in oncology. Lancet Oncol (2001) 2(8):475–82. 10.1016/s1470-2045(01)00453-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mantel N, Haenszel W. Statistical aspects of the analysis of data from retrospective studies of disease. J Natl Cancer Inst (1959) 22(4):719–48. 10.1093/jnci/22.4.719 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med (2002) 21(11):1539–58. 10.1002/sim.1186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Begg CB, Mazumdar M. Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics (1994) 50(4):1088–101. 10.2307/2533446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. Bmj (1997) 315(7109):629–34. 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Duval S, Tweedie R. Trim and fill: A simple funnel-plot-based method of testing and adjusting for publication bias in meta-analysis. Biometrics (2000) 56(2):455–63. 10.1111/j.0006-341x.2000.00455.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Chua DT, Sham JS, Choy D, Lorvidhaya V, Sumitsawan Y, Thongprasert S, et al. Preliminary report of the Asian-Oceanian Clinical Oncology Association randomized trial comparing cisplatin and epirubicin followed by radiotherapy versus radiotherapy alone in the treatment of patients with locoregionally advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Asian-Oceanian Clinical Oncology Association Nasopharynx Cancer Study Group. Cancer (1998) 83(11):2270–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ma J, Mai HQ, Hong MH, Min HQ, Mao ZD, Cui NJ, et al. Results of a prospective randomized trial comparing neoadjuvant chemotherapy plus radiotherapy with radiotherapy alone in patients with locoregionally advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma. J Clin Oncol (2001) 19(5):1350–7. 10.1200/jco.2001.19.5.1350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hareyama M, Sakata K, Shirato H, Nishioka T, Nishio M, Suzuki K, et al. A prospective, randomized trial comparing neoadjuvant chemotherapy with radiotherapy alone in patients with advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Cancer (2002) 94(8):2217–23. 10.1002/cncr.10473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Frikha M, Auperin A, Tao Y, Elloumi F, Toumi N, Blanchard P, et al. A randomized trial of induction docetaxel-cisplatin-5FU followed by concomitant cisplatin-RT versus concomitant cisplatin-RT in nasopharyngeal carcinoma (GORTEC 2006-02). Ann Oncol (2018) 29(3):731–6. 10.1093/annonc/mdx770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Blanchard P, Lee A, Marguet S, Leclercq J, Ng WT, Ma J, et al. Chemotherapy and radiotherapy in nasopharyngeal carcinoma: an update of the MAC-NPC meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol (2015) 16(6):645–55. 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)70126-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Zhang L, Huang Y, Hong S, Yang Y, Yu G, Jia J, et al. Gemcitabine plus cisplatin versus fluorouracil plus cisplatin in recurrent or metastatic nasopharyngeal carcinoma: a multicentre, randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet (2016) 388(10054):1883–92. 10.1016/s0140-6736(16)31388-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Liu M-Z, Tang L-L, Zong J-F, Huang Y, Sun Y, Mao Y-P, et al. Evaluation of Sixth Edition of AJCC Staging System for Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma and Proposed Improvement. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys (2008) 70(4):1115–23. 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2007.07.2353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Chen L, Mao YP, Xie FY, Liu LZ, Sun Y, Tian L, et al. The seventh edition of the UICC/AJCC staging system for nasopharyngeal carcinoma is prognostically useful for patients treated with intensity-modulated radiotherapy from an endemic area in China. Radiother Oncol (2012) 104(3):331–7. 10.1016/j.radonc.2011.10.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Sun R, Qiu HZ, Mai HQ, Zhang Q, Hong MH, Li YX, et al. Prognostic value and differences of the sixth and seventh editions of the UICC/AJCC staging systems in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol (2013) 139(2):307–14. 10.1007/s00432-012-1333-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Razek AAKA, King A. MRI and CT of Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma. Am J Roentgenol (2012) 198(1):11–8. 10.2214/ajr.11.6954 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ng S-H, Chan S-C, Yen T-C, Chang JT-C, Liao C-T, Ko S-F, et al. Staging of untreated nasopharyngeal carcinoma with PET/CT: comparison with conventional imaging work-up. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging (2008) 36(1):12–22. 10.1007/s00259-008-0918-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Liu N, Chen NY, Cui RX, Li WF, Li Y, Wei RR, et al. Prognostic value of a microRNA signature in nasopharyngeal carcinoma: a microRNA expression analysis. Lancet Oncol (2012) 13(6):633–41. 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70102-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Song JH, Wu HG, Keam BS, Hah JH, Ahn YC, Oh D, et al. The Role of Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy in the Treatment of Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma: A Multi-institutional Retrospective Study (KROG 11-06) Using Propensity Score Matching Analysis. Cancer Res Treat (2016) 48(3):917–27. 10.4143/crt.2015.265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ou D, Blanchard P, El Khoury C, De Felice F, Even C, Levy A, et al. Induction chemotherapy with docetaxel, cisplatin and fluorouracil followed by concurrent chemoradiotherapy or chemoradiotherapy alone in locally advanced non-endemic nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Oral Oncol (2016) 62:114–21. 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2016.10.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Zhang LN, Gao YH, Lan XW, Tang J, OuYang PY, Xie FY. Effect of taxanes-based induction chemotherapy in locoregionally advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma: A large scale propensity-matched study. Oral Oncol (2015) 51(10):950–6. 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2015.07.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Peng H, Dong D, Fang MJ, Li L, Tang LL, Chen L, et al. Prognostic Value of Deep Learning PET/CT-Based Radiomics: Potential Role for Future Individual Induction Chemotherapy in Advanced Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res (2019) 25(14):4271–9. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-18-3065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Dong D, Zhang F, Zhong LZ, Fang MJ, Huang CL, Yao JJ, et al. Development and validation of a novel MR imaging predictor of response to induction chemotherapy in locoregionally advanced nasopharyngeal cancer: a randomized controlled trial substudy (NCT01245959). BMC Med (2019) 17(1):190. 10.1186/s12916-019-1422-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.