Abstract

This cross-sectional study describes the differential associations of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic with opioid-related overdoses among racial/ethnic groups in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Introduction

Opioid overdoses have increased during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic.1 Potential contributors include treatment center closures, physical isolation preventing bystander rescue, mental health stressors, financial instability, and changes to drug supply networks.2 Black individuals with opioid use disorder (OUD) may be disproportionately affected, given the racial disparities in COVID-19 morbidity and mortality.3 We describe the differential associations of the COVID-19 pandemic with overdoses among racial/ethnic groups in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Methods

In this cross-sectional study, unintentional fatal opioid-related overdose (FOO) and emergency medical services (EMS)–attended nonfatal opioid-related overdose (NFOO) counts were extracted from deidentified publicly available data from the Philadelphia Department of Public Health’s Substance Use Data Dashboard. The Philadelphia Medical Examiner’s Office was used to identify unintentional opioid overdose deaths. Naloxone administrations by EMS were collected by the Philadelphia Fire Department and used as a proxy for EMS-attended NFOO. Race/ethnicity was classified by the decedent’s family for FOO and by EMS professionals for NFOO. Because this study used aggregated public data, it did not constitute human participant research according to the University of Pennsylvania institutional review board. This study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology ( STROBE ) reporting guideline for cross-sectional studies.

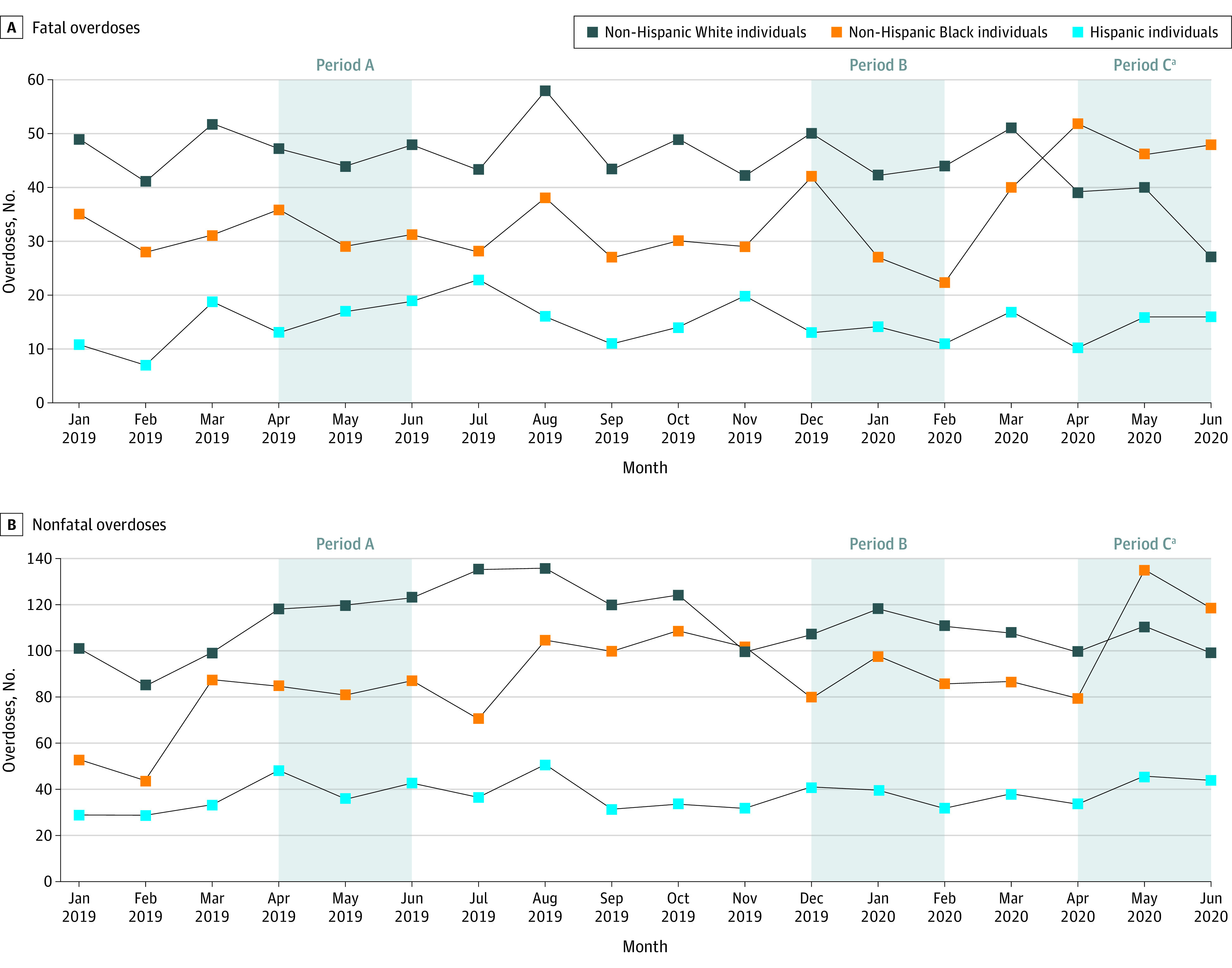

We analyzed data from January 2019 through June 2020 and compared the mean monthly counts of FOO and NFOO before and after the March 23, 2020, Philadelphia stay-at-home order. Excluding March as a washout period, we compared mean counts in the 3 months after the order (April to June 2020; period C) to 3 months before (December 2019 to February 2020; period B) and the same 3-month period the year prior (April to June 2019; period A). We used a t test of equal variance with a 2-sided significance level of P < .05. Data were analyzed using Stata/IC version 15.1 (StataCorp).

Results

Overall, FOO counts were unchanged in period C (monthly mean [SD], 98.0 [6.1]) compared with period A (monthly mean [SD], 94.7 [4.2]). Among non-Hispanic Black individuals, the mean monthly (SD) FOO count increased from 32.0 (3.6) in period A and 30.3 (10.4) in period B to 48.7 (3.1) in period C, representing a 52.1% increase from period A to C and a 60.4% increase period B to C (Table). In contrast, among non-Hispanic White individuals, the mean (SD) counts for periods A to C were 46.3 (2.1), 45.3 (4.2), and 35.3 (7.2), respectively, representing a 23.8% decrease from period A to C and a 22.1% decrease from period B to C. Period C represents the first time in recent history in Philadelphia that the absolute number of deaths was higher among non-Hispanic Black individuals than among non-Hispanic White individuals. Among Hispanic individuals, mean counts decreased from period A to C but increased from period B to C. Similar trends by race were seen for the mean monthly count of EMS naloxone administrations among non-Hispanic Black, non-Hispanic White, and Hispanic individuals (Table and Figure).

Table. Mean Monthly Counts of Fatal and Emergency Medical Service–Attended Nonfatal Opioid Overdose by Race/Ethnicity.

| Race/ethnicity | Period A, April to June2019 | Period B, December 2019 to February 2020 | Period C, April to June 2020 | P value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total, No. | Monthly mean (SD) | Total, No. | Monthly mean (SD) | Total, No. | Monthly mean (SD) | Period A and C | Period B and C | |

| Fatal | ||||||||

| Non-Hispanic Black | 96 | 32 (3.6) | 91 | 30.3 (10.4) | 146 | 48.7 (3.1) | .004 | .04 |

| Non-Hispanic White | 139 | 46.3 (2.1) | 136 | 45.3 (4.2) | 106 | 35.3 (7.2) | .06 | .11 |

| Hispanic | 49 | 16.3 (3.1) | 38 | 12.7 (1.5) | 42 | 14 (3.5) | .43 | .57 |

| Nonfatal | ||||||||

| Non-Hispanic Black | 253 | 84.3 (3.1) | 264 | 88 (9.2) | 309 | 111 (28.8) | .19 | .26 |

| Non-Hispanic White | 361 | 120.3 (2.5) | 336 | 112 (5.6) | 333 | 103 (6.9) | .02 | .15 |

| Hispanic | 127 | 42.3 (6.0) | 113 | 37.7 (4.9) | 124 | 41.3 (6.4) | .85 | .48 |

Figure. Opioid-Related Fatal and Emergency Medical Services–Attended Nonfatal Overdoses by Race/Ethnicity.

aPeriod C indicates period of stay-at-home order, which began on March 23, 2020.

Discussion

Increasing opioid overdoses during COVID-19 have received national attention in the United States, but there has been little exploration of the differential trends among racial/ethnic groups.4 In Philadelphia, COVID-19 was associated with increases in opioid overdose among non-Hispanic Black individuals but decreases among non-Hispanic White individuals. COVID-19 has exacerbated preexisting stressors, social isolation, and economic deprivation disproportionately in Black communities, possibly contributing to increased substance use. The preexisting racial disparities in accessing substance use treatment may also be heightened by COVID-19–related shifts in treatment availability.5

Notably, we are limited by our short observation period and inability to determine whether the overdoses were due to inadvertent opioid exposure (eg, fentanyl contamination of stimulants) and primary opioid use vs polysubstance use.6 Further analysis with additional months of data to observe random variation is warranted. Disaggregated data from other cities analyzed by race/ethnicity should be prioritized. OUD treatment, harm reduction, and overdose prevention efforts should be immediately targeted to Black and other communities at highest risk during and after the COVID-19 pandemic.

References

- 1.Slavova S, Rock P, Bush HM, Quesinberry D, Walsh SL. Signal of increased opioid overdose during COVID-19 from emergency medical services data. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2020;214:108176. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2020.108176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang QQ, Kaelber DC, Xu R, Volkow ND. COVID-19 risk and outcomes in patients with substance use disorders: analyses from electronic health records in the United States. Mol Psychiatry. 2020. doi: 10.1038/s41380-020-00880-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Millett GA, Jones AT, Benkeser D, et al. Assessing differential impacts of COVID-19 on black communities. Ann Epidemiol. 2020;47:37-44. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2020.05.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.American Medical Association Issue brief: reports of increases in opioid- and other drug-related overdose and other concerns during COVID pandemic. Updated December 9, 2020. Accessed December 11, 2020. https://www.ama-assn.org/system/files/2020-12/issue-brief-increases-in-opioid-related-overdose.pdf

- 5.Goedel WC, Shapiro A, Cerdá M, Tsai JW, Hadland SE, Marshall BDL. Association of racial/ethnic segregation with treatment capacity for opioid use disorder in counties in the United States. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(4):e203711. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.3711 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Khatri UG, Viner K, Perrone J. Lethal fentanyl and cocaine intoxication. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(18):1782-1782. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1809521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]