Abstract

Myelolipomas are rare benign tumors that contain a mix of fatty and hematopoietic tissues. These tumors are frequently seen in the adrenal glands. While extra-adrenal myelolipomas are extremely rare, once identified, they are commonly found in the retroperitoneum––particularly the presacral region. Because of the fat content, these tumors can be easily mistaken for retroperitoneal liposarcomas. We are presenting a case of a 44-year-old female with a pathology proven case of retroperitoneal extra-adrenal myelolipoma that was initially diagnosed by imaging as a retroperitoneal liposarcoma. In this case report, the clinical presentation, imaging findings, operative details and histopathology features are illustrated.

Keywords: Myelolipoma, Extra-adrenal, Retroperitoneal, Computed tomography, Magnetic resonance imaging

Introduction

Myelolipoma is a benign tumor consisting of mature adipose tissue and normal hematopoietic elements that is normally found in the adrenal glands. Myelolipomas comprise 6%-16% of adrenal incidentalomas and are the second most common cause after adrenal adenomas [1]. This tumor can rarely occur outside the adrenal gland and is subsequently called extra-adrenal myelolipoma (EAM). EAM is commonly localized in the retroperitoneum (RP), particularly in in the presacral region. Involvement of other intra-abdominal and thoracic regions has also been reported [2,3]. While the etiopathogenesis is unknown, the prevalence is rising from increased detection by various imaging techniques. There have only been more than 50 cases of extra-adrenal myelolipomas discussed in literature [4]. We are presenting a case of 44-year-old female with incidentally discovered RP mass diagnosed by imaging as liposarcoma. The differential included retroperitoneal teratoma and extramedullary hematopoiesis.

Case presentation

A 44-year-old female patient presented to the Emergency Department due to a 2-day history of worsening left upper quadrant abdominal pain, radiating to the flank. She had been experiencing left lower quadrant abdominal pain since her intrauterine device was placed in April 2020. Since then she also noticed progressively worsening vaginal bleeding, mild dysuria, fever, generalized malaise, and left-sided flank pain. She was initially evaluated at an outside hospital with computed tomography (CT) scan showing a retroperitoneal mass measuring 4.7 × 12 × 11 cm in addition to a left adnexal mass consistent with a tubo-ovarian abscess (TOA) measuring 2 × 2.3 × 2.2 cm. With a persistent fever and leukocytosis in the context of her CT findings, she was admitted to the gynecology service for treatment of her TOA. Nephrology was consulted from elevated creatinine levels. Surgical oncology was also consulted for management of the retroperitoneal mass. After resolution of her initial TOA-related symptoms, repeat CT and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) redemonstrated a 12.7 cm heterogenous fat and soft tissue containing retroperitoneal mass, suspicious for dedifferentiated liposarcoma (Fig. 1). MRI images were significantly degraded by susceptibility artifacts from spine fixation hardware. Differential considerations included retroperitoneal teratoma and extramedullary hematopoiesis. The retroperitoneal mass was abutting her native left kidney, as she had received a kidney transplant secondary to membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis. She underwent an exploratory laparotomy with excision of a 14 cm left retroperitoneal mass, nephrectomy of the native left kidney, left partial colectomy, left adrenalectomy, mobilization of splenic flexure, partial left diaphragm resection with primary repair, and creation of vascularized omental pedicle flap for anastomotic reinforcement. Periaortic lymph nodes were also excised. The patient had no complications postoperatively and is doing well to date.

Fig. 1.

Noncontrast sagittal (a), axial (b) and coronal (c) CT images of the abdomen and pelvis showing large 4.7 × 12 × 11 cm multilobulated heterogenous mass of fat and soft tissue attenuation (white arrows). The mass is located in the left posterior pararenal space. It results in anterior displacement of the surrounding structures including the native atrophic left kidney.

On gross examination, the tumor measured 14 × 11 × 8 cm (Fig. 2). A hematopathologist was consulted to exclude hematopoietic neoplasm. The specimen exhibited bone marrow with trilineage hematopoiesis, predominance of myeloid tissue with left shift, and scattered lymphoid aggregates; these findings were more consistent with a myelolipomatous neoplasm (Fig. 3). Periaortic lymph nodes were negative for neoplasms.

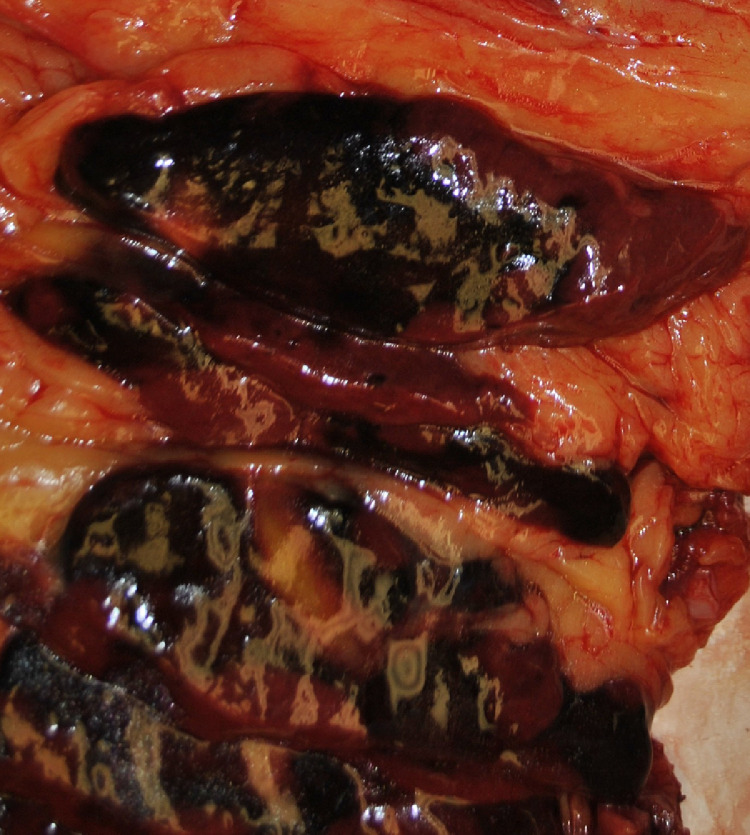

Fig. 2.

The mass is 14 × 11 × 8 cm, well-circumscribed, and has a red-brown soft solid cut surface, admixed with yellow fatty tissue. No areas of necrosis identified macroscopically. This mass is entirely separated from the kidney. (Color version of figure is available online.)

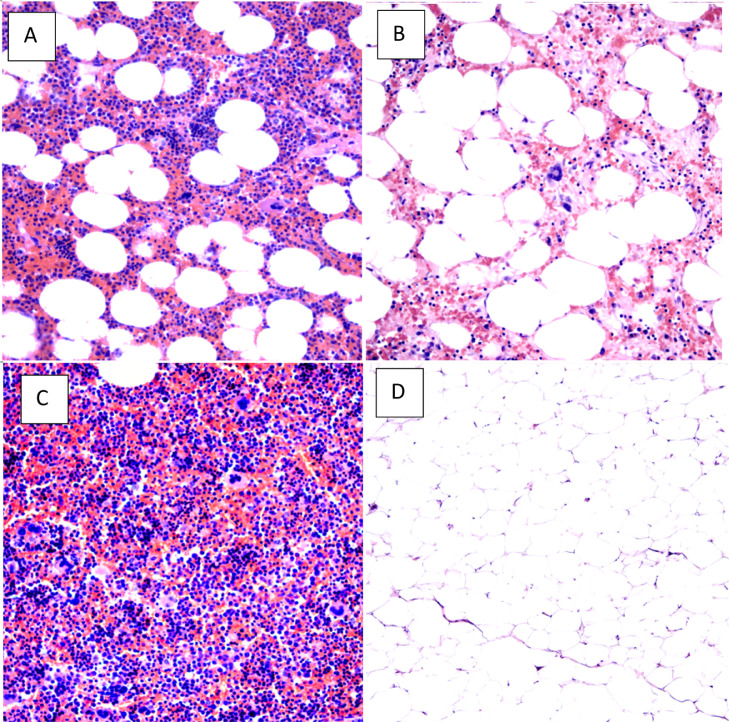

Fig. 3.

(a), (b) The tumor composed of areas with both lipomatous component admixed with benign trilineage hematopoietic components, (c) In other areas, the tumor consists of entirely hematopoietic component or (d) entirely lipomatous component. These microphotographs were taken at 100× magnification of the original H&E stains and represent various areas of the tumor.

Discussion

Myelolipomas are rare and unusual benign tumors, characterized by both hematopoietic and mature adipose tissue. In 1957, Dyckman and Freedman reported the first case of myelolipoma and in 1985, Blois and May published the first case report diagnosed by CT scan and fine-needle aspiration [5].

Since then, almost all myelolipomas have been discovered within the adrenal gland and only around 50 cases of extra-adrenal myelolipomas have been reported [4]. These tumors used to be incidental findings on autopsy; however, with the advancement of imaging techniques, they are increasingly being detected. The mean age at onset is 61 years and these lesions affect females more than males [6]. While the natural history and etiology of extra-adrenal myelolipomas are unknown, they can cause significant symptoms due to mass effect as the largest reported myelolipoma was 26 cm [7]. In addition, these tumors are very difficult to diagnose preoperatively as they appear identical to liposarcomas. Consequently, differentiation between myelolipomas and other retroperitoneal fat containing masses can be challenging based solely on cross-sectional imaging using CT or MRI (Fig. 1). Most fat-containing retroperitoneal tumors are liposarcomas, which was suspected in this patient's initial work up. Fortunately, there are tests that allow clinicians to uniquely identify myelolipomas. A technetium Tc 99m-sulfur colloid nuclear medicine scan can differentiate extra-adrenal myelolipoma from liposarcoma, as EAM will uptake the tracer while liposarcoma shows absence of any uptake [8]. In addition, sulfur colloid is taken up by special cells in lymph tissue, liver, spleen, and bone marrow. While the aforementioned technetium Tc 99m-sulfur colloid scan is an initial diagnostic test, biopsy will differentiate myelolipomas from liposarcomas which are identified histologically by the presence of lipoblasts and zones of cellular atypia.

Other diagnoses that should be ruled out include extramedullary hematopoiesis and primary retroperitoneal teratoma. Extramedullary hematopoiesis is composed of hematopoietic cells and is devoid of lymphoid cell aggregates or adipose tissue. Retroperitoneal teratomas are masses that contain a multitude of tissue types including fat, hair, muscle, teeth, or bone but not myeloid tissue.

With respect to management, in the absence of a compelling benign radiographic diagnosis, all retroperitoneal tumors should be considered for resection [9]. Biopsy of these lesions is not typically recommended, as this can potentially result in seeding of malignant cells. Furthermore, the biopsy tract cannot be practically excised. The size of the tumor will determine which procedure is used for practical excision of the lesion. This patient's tumor was large enough leading to extra-adrenal symptoms from mass effect which prompted a laparotomy.

This case report provides evidence that while extra-adrenal myelolipomas are rare lesions, they must be considered on the differential diagnosis for encapsulated, fat-containing retroperitoneal lesions. When EAM is suspected, further assessment using technetium Tc 99m-sulfur colloid nuclear medicine scan should be considered for initial diagnostic purposes.

Patient consent statement

Patient was notified and consented for the publication of this report.

Authors contributions

All authors conceived data, scrutinized, and identified the most appropriate literature. All authors analyzed, synthesized, and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Competing interest: Authors declare no competing interests

Contributor Information

Junsang Cho, Email: jczd2@health.missouri.edu.

Danielle Kinsey, Email: djk994@health.missouri.edu.

Eric T. Kimchi, Email: kimchie@health.missouri.edu.

Kevin Staveley O'Carroll, Email: ocarrollk@health.missouri.edu.

Van Nguyen, Email: nguyenvt@health.missouri.edu.

Mustafa Alsabbagh, Email: alsabbaghm@health.missouri.edu.

Ayman Gaballah, Email: gaballaha@missouri.edu.

References

- 1.Chen KC, Chiang HS, Lin YH. Adrenal myelolipoma: a case report with literature review. J Urol. 2000;11(4):185–189. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chan YF, Yu SJ, Chan YT, Yik YH. Presacral myelolipoma: case report with computed tomographic and angiographic findings. Aust N Z J Surg. 1988;58:432–434. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.1988.tb01094.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rao P, Kenney PJ, Wagner BJ, Davidson AJ. Imaging and pathologic features of myelolipoma. RadioGraphics. 1997;17:1373–1385. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.17.6.9397452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sohoni CA. Extra-adrenal myelolipoma: a rare entity in paediatric age group. APSP J Case Rep. 2013;4(3):36. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Akamatsu H, Koseki M, Nakaba H, Sunada S, Ito A, Teramoto S. Giant adrenal myelolipoma: report of a case. Surg Today. 2004;34(3):283–285. doi: 10.1007/s00595-003-2682-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kammen BF, Elder DE, Fraker DL, Siegelman ES. Extraadrenal myelolipoma: MR imaging findings. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1998;171(3):721–723. doi: 10.2214/ajr.171.3.9725304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Doddi S, Singhal T, Leake T, Sinha P. Management of an incidentally found large adrenal myelolipoma: a case report. Cases J. 2009;2:8414. doi: 10.4076/1757-1626-2-8414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nguyen Ba D. MD retroperitoneal extraadrenal myelolipoma: technetium-99m sulfur colloid scintigraphy and CT imaging. Clin Nucl Med. 2007;32(2):135–138. doi: 10.1097/01.rlu.0000252239.49139.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.ESMO/European Sarcoma Network Working Group Soft tissue and visceral sarcomas: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2014;25(Suppl 3) doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdu254. iii102–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]