Abstract

Objective

Despite efforts to reduce cancer disparities, Black women remain underrepresented in cancer research. Virtual health assistants (VHAs) are one promising digital technology for communicating health messages and promoting health behaviors to diverse populations. This study describes participant responses to a VHA‐delivered intervention promoting colorectal cancer (CRC) screening with a home‐stool test.

Methods

We recruited 53 non‐Hispanic Black women 50 to 73 years old to participate in focus groups and think‐aloud interviews and test a web‐based intervention delivered by a race‐ and gender‐concordant VHA. A user‐centered design approach prioritized modifications to three successive versions of the intervention based on participants' comments.

Results

Participants identified 26 cues relating to components of the VHA's credibility, including trustworthiness, expertise, and authority. Comments on early versions revealed preferences for communicating with a human doctor and negative critiques of the VHA's appearance and movements. Modifications to specific cues improved the user experience, and participants expressed increased willingness to engage with later versions of the VHA and the screening messages it delivered. Informed by the Modality, Agency, Interactivity, Navigability Model, we present a framework for developing credible VHA‐delivered cancer screening messages.

Conclusions

VHAs provide a systematic way to deliver health information. A culturally sensitive intervention designed for credibility promoted user interest in engaging with guideline‐concordant CRC screening messages. We present strategies for effectively using cues to engage audiences with health messages, which can be applied to future research in varying contexts.

Keywords: colorectal neoplasms, cues, early detection of cancer, health communication, internet‐based intervention, oncology, psycho‐oncology, qualitative research

1. BACKGROUND

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third‐leading cause of cancer deaths among Black women, who experience disproportionate mortality compared to other racial/ethnic groups in the United States. 1 , 2 When detected early, CRC has a 5‐year survival rate of 90%. However, early screening is essential, and Black adults are frequently diagnosed late. Efforts to improve CRC screening can reduce mortality as well as health outcome disparities. 3 Web‐based health interventions can be an accessible, cost‐effective way to support CRC screening recommendations among underserved populations, if delivered in culturally sensitive ways. 4 We discuss a method for doing so with one specific population currently underrepresented in cancer research. 5

Key points/Highlights.

Virtual human technology (VHT) may be an important digital technology for encouraging colorectal cancer (CRC) screening among Black women

This works describes one method of incorporating patient perspectives into the development of a digital health intervention

VHT provides an acceptable method of delivering systematic, guideline‐concordant CRC screening messages from a credible source

Patient experiences should be intentionally sought and applied to health promotion efforts relevant to clinical settings

1.1. CRC screening options

American Cancer Society guidelines recommend that adults at average risk start regular CRC screening at age 50 and continue until age 75. 6 The US Preventive Services Task Force provides an A‐rating for CRC screening of this age group. 7

Multiple guideline‐concordant screening options exist. Colonoscopies are an invasive screening modality completed at healthcare facilities. For average‐risk adults, many noninvasive home stool tests exist, including the fecal immunochemical testing (FIT), among others. 2

Despite wide availability of home stool tests, in 2015 only 8% of Black adults used them to screen for CRC. 2 Possible barriers include low acceptance or knowledge of the noninvasive options among both physicians and patients. 8 , 9 One study found that Black adults who had not obtained screening were relying on clinician recommendation to test: “So I'm pretty sure if he had a reason for me to get screened, he would tell me (p. 75).” 10 Providing opportunities for patients to learn about noninvasive tests may be an important strategy to increase screening rates of Black adults. 11 , 12

1.2. Virtual health assistants (VHAs)

Virtual human technology (VHT) presents new opportunities for communicating tailored, culturally aligned health messages 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 to diverse populations via web‐based settings. Computer‐generated characters called VHAs can be customized in attire, physical features, skin tone, language, and voice characteristics. VHAs have been used in patient‐centered research on medication adherence among Black men with HIV, 17 to supplement information provided by healthcare providers among Hispanic women, 18 and to facilitate communication with low health‐literacy populations. 19

VHT raises important implications for decision‐making, trust, willingness to disclose information, and truthfulness of disclosures across a variety of patient populations. 19 , 20 For many minoritized populations (i.e., groups systematically positioned as “less than” or “other”), stigma is an important factor leading to health disparities. 21 VHAs have been found effective at reducing patients' feelings of stigma and fear of being negatively judged by healthcare providers. 20

1.3. Credibility and the MAIN Model

In health communication, credibility—the combination of expertise and trustworthiness—is often defined as the believability of a message source. 22 , 23 Expertise is the degree to which a source is perceived to possess adequate knowledge to make valid assertions, while trustworthiness is the degree to which a source is perceived as providing truthful, unbiased information. 24 Emerging technologies such as VHAs present opportunities to understand how credibility judgments are made in novel contexts. 25

One way to understand how credibility forms in a virtual environment is to assess relationships between cues and heuristics. Cues provide information via message elements (e.g., language, tone, and pauses) or visual design elements (e.g., appearance) that get interpreted and used by an observer. 25 Heuristics are mental shortcuts that allow quick evaluation of content and facilitate decision‐making. 26 The heuristic‐systematic model 27 suggests people use heuristics to evaluate the credibility of an information source. A source's group membership—such as race and gender, among other characteristics—can function as cues that trigger heuristics that affect decision‐making. 28 Thus, assessing user perceptions of cues is an important part of creating a credible message source.

The Modality, Agency, Interactivity, Navigability (MAIN) Model 28 is a framework for examining the credibility of web‐based content. In this model, four affordances (or perceptible opportunities for action) convey cues that affect perceived credibility: (1) modality: the structure of information (e.g., text, audio, and video); (2) agency: user evaluation of the message source; (3) interactivity: user ability to make real‐time changes to content or be both source and receiver of information; and (4) navigability: ease of use, as in locating and navigating the technical features. Cues communicated via any of these four affordances may trigger heuristics that influence credibility. For example, when one has the feeling of being with a real person when interacting with technology; they experience the social presence heuristic. 29

Black women are underrepresented in cancer research, including research utilizing technology. 5 Our research questions address this: (RQ1) what cues are important for credibility in a VHA‐delivered intervention? (RQ2) How do cues and heuristics interact to shape credibility of a VHA‐delivered intervention promoting CRC screening among Black women?

2. METHODS

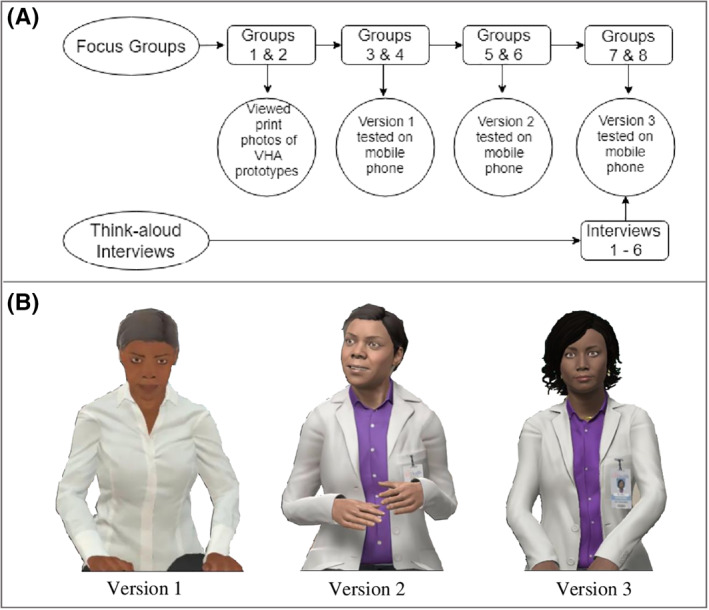

This analysis is part of a larger study that aimed to develop and test a web‐based, intervention promoting CRC screening with VHAs of varied race and gender. 30 As a precursor to the launch of a randomized controlled trial, a user‐centered design approach was used to iteratively test and modify evolving versions of race‐ and gender‐concordant VHAs (Figure 1A). The team science approach relied on researchers learning discipline‐specific language, communicating goals, and prioritizing changes. 31 The team included health communication researchers, graphic designers, computer scientists, medical oncologists, and community advisory members. The study was approved by Institutional Review Board (IRB201601642) and is a registered clinical trial (NCT03867409).

FIGURE 1.

(A) Participant comments informed iterative modifications to the virtual health assistant (VHA) intervention. (B) VHAs viewed during focus groups and think‐aloud interviews

Participants were recruited through a research registry and senior center in North Florida. They provided written informed consent and were enrolled between January 2017 and November 2018. Eligible participants were 50–73 years old, non‐Hispanic Black or White, and proficient in English. All participants received a $35 gift card. Focus groups and interviews, were audio‐recorded, transcribed verbatim, and managed with NVivo12.

2.1. Focus groups

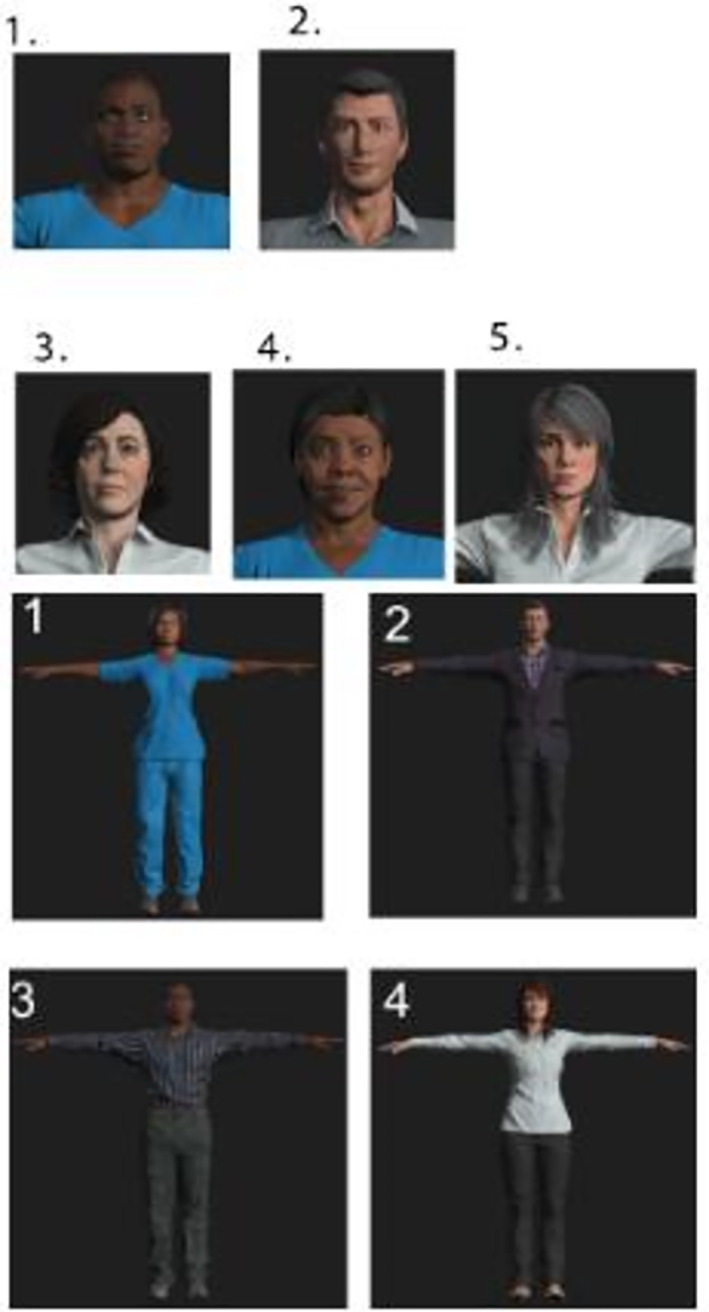

Participants in focus groups 1 and 2 (Figure 1A) completed a paper demographic questionnaire, participated in a moderated discussion, listened to four distinct professionally recorded voice prototypes, and viewed print images of virtual characters (Figure 2). These discussions informed version 1 of the VHA (Figure 1B). Participants in focus groups 3 through 8 completed a paper demographic questionnaire, used a mobile phone with headphones to test the current version of the VHA, and then completed a paper questionnaire assessing various perceptions of the intervention, followed by a moderated discussion.

FIGURE 2.

VHA prototypes used as print stimuli for focus groups 1 and 2

2.2. Think‐aloud interviews

Six individual interviews were conducted to obtain participants' thoughts while interacting with version 3 of the intervention. Participants were instructed to start the intervention and verbalize thoughts as they occurred. Participants completed the paper questionnaire and discussed perceptions of the intervention with a moderator.

2.3. Intervention

The intervention lasted approximately 9 min. It included (1) an introduction, (2) information about CRC, (3) interactive health behavior questions, (4) information about FIT screening, (5) discussion of screening barriers, and (6) an opportunity to request a FIT.

2.4. Data analysis

A priori codes were derived from literature and review of transcripts to reflect theoretically informed components of credibility. Additional codes were added during line‐by‐line reading of transcripts. Codes were not mutually exclusive. Two coders (Melissa J. Vilaro and Danyell S. Wilson‐Howard) independently coded a transcript and calculated inter‐rater reliability using NVivo's coding comparison query. Coding discrepancies were documented and reviewed (TF) for feedback. After three rounds of coding, low Kappa scores (below 0.5) were determined to be due to unitization issues rather than content disagreements. 32 Twenty percent of the transcripts were then unitized by placing boxes around text segments. On the fourth round of coding, Kappa was above 0.8 for all codes. Thematic analysis included constant comparison. 33

2.5. Data availability

The data that support our findings are available upon request.

3. RESULTS

Fifty‐three Black women participated in focus groups (n = 47) and interviews (n = 6; see supplemental table, Table S1). Focus groups averaged 65 min, with two to 11 participants per group. Interviews averaged 30 min. Overall, we identified 26 cues and three heuristics contributing to the credibility of the VHA‐delivered intervention (Table 1). Participants who tested version 1 preferred communication with a real doctor, suggested interactive features, and negatively reacted to the VHA's appearance and movements. Modifications improved later perceptions of these cues, indicated by increasingly positive comments regarding trustworthiness, expertise, social presence, content, and navigability. By version 3, negative comments essentially disappear with participants wanting to interact with the VHA and share information with family. Identified cues and heuristics inform a framework for establishing credibility of a VHA‐delivered health interventions (See supplementary files, Figure S1 and Table S2).

TABLE 1.

Participant descriptions of cues categorized by Modality, Agency, Interactivity, Navigability Model affordance

| Affordance | Heuristic | Cue | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Modality | |||

| Audio | “I would listen to her because she's in a setting [hospital] that would suggest she knows what she's talking about” (TA43, VER3). | ||

| Visual | |||

| Text | “I was reading [subtitles] as she was talking” (P48, FG4, VER1). | ||

| Agency | |||

| Trustworthiness | |||

| Voice | “Her voice was so convincing. You could just ease right into it” (P34, FG7, VER3). | ||

| Friendliness/likability | “Make her a little more friendly” (P47, FG4, VER1).“Happy, very happy. You have some people talk to you, they want to show happy, but you can see the other side. All I see was happiness in her” (TA33, VER 3). | ||

| Appearance | “I don't wanna go to nobody looking all weird and start asking me questions” (P91, FG1, print).“Eyes were funny,” and “[she] could be a little bit easier on the eyes” (P38, FG3, VER1). | ||

| Expertise | |||

| Authority | “I want it to come from a doctor, that's my opinion. Nurses don't know…that's why they're a nurse...” (P48, FG4, VER1). | ||

| Clothing | “The scrubs, I mean they're bland. Everybody wears scrubs that aren't doctors” (P103, FG2, print). | ||

| Age | “She sounded young…too young to be a doctor giving us this important advice” (P44, FG4, VER1). | ||

| Content | |||

| Novel | “It said you would [test] annually, every year, for the FIT. I didn't think you would have to do it that often” (P33, FG3, VER1). | ||

| Confusing | “If it's loose [stool], do you do the same thing?” (TA34, VER3). | ||

| Consistent | “I trusted what she was sayin’ and mainly because I had gone through it…proving most of what she said was true all the time” (P135, FG8, VER3). | ||

| Understandable | “It wasn't like with all these big words that I can't understand at all…even a child could understand what she was saying” (P133, FG8, VER3). | ||

| Missing | “It was basically saying, look, there's this nifty new FIT thing that you can do at home…But it didn't really explain why [to choose FIT over colonoscopy]” (P44, FG4, VER2). | ||

| Social presence | |||

| Movement | “The movements of her hand—usin’ her hand figuratively…a lot of people talk like that. That was really human, and actually they're easy to understand when she does it” (P133, FG8, VER3). | ||

| Fake versus real | “It's not real…I'll interact with you [moderator] not her [referencing VHA]” (P91, FG1, print).“It's more lifelike…like a real woman” (P132, FG8, VER3). | ||

| Scary/creepy | “Well, I just found the image really distracting. I ended up just listening to it, and not watching. It creeped me out” (P36, FG3, VER1).“Excellent job with that. It wasn't scary. Sometimes these things are scary” (P139, FG7, VER3). | ||

| Interactivity | |||

| Social presence | |||

| Personalization/Customization | “If there is something that increases the possibility of that person developing cancer…it should ask more questions. Make it more personal…” (P32, FG3, VER1). | ||

| Choice and control | “When you're accessing the app and you push on male or female, there's going to be other options? Do you know?” (P34, FG3, VER1). | ||

| Responsiveness | “They asked you a question, what was your reluctance to having the test…You have to pick one, and if you didn't pick one it just sat there and stared at you” (P32, FG3, VER1). | ||

| Ability to ask questions | “I might need to wanna’ know something before I go off and take this test…[There's] nobody there to answer the question for you. If I don't get an answer, why would I sit there and listen to that then?” (P118, FG5, VER2). | ||

| Navigability | |||

| Ease of navigating | “Nobody likes technology when they're a certain age, and this is just easy…you just plug in, listen, and it was really simple” (P113, FG5, VER2). | ||

| Transitions | “It's very user‐friendly, but there's no back button to review or make corrections. I inadvertently hit ‘yes’ for smoker, and I've never smoked a day in my life, and of course you can't go back to make that change” (P32, FG3, VER1). | ||

| Scaffolding | |||

3.1. A framework for credibility of VHA‐delivered health messages

3.1.1. Modality

All focus groups and interviews discussed audio, visual, and text cues (288 comments coded to modality). Combining multiple modalities, such as subtitles, audio, and visuals, enhanced user experience and credibility. Visual cues also aided credibility.

3.1.2. Agency

Discussions of agency also occurred in all focus groups and interviews (1203 comments). This domain contained cues related to heuristics for trustworthiness, expertise, content, and social presence.

3.1.2.1. Trustworthiness

Cues related to trust were voice, friendliness/likability, and appearance. Rate of speech was important; voices that were too fast, too slow, or sounded like a salesperson were criticized. One voice was described as sounding “Black,” and participants responded positively. Both in voice and appearance, participants wanted a friendly and likeable VHA. The version 1 VHA was criticized for looking “like she's got an attitude.” Early assessments of appearance also negatively influenced some participants. Most comments coded to appearance (87%) were for versions 1 and 2, and encouraged adaptations. For example, between VHA version 2 and 3, researchers added a smile and removed a furrowed brow. By version 3, only positive comments were made regarding the VHA's appearance.

3.1.2.2. Expertise

Three cues related to expertise: authority, clothing, and age. Authority, often linked to credibility, can be represented by credentials. 34 Participants also had a strong preference for professional attire (white coat vs. scrubs). Age was important. Youth represented “more current knowledge” (P103, FG2, print). Users preferred a middle age VHA. Researchers were able to adjust appearance of skin, fine lines, and hair color to modify perceptions of age.

3.1.2.3. Content

Participants discussed five content cues: novel, confusing, consistent, understandable, or missing content. Novel content was more frequently mentioned for version 3 (18 references) than versions 1 or 2 (11 and 7 references, respectively). Novel content provided new insights. Confusing content prompted questions: Participants asked whether FIT results were instant or sent to a lab, and how to collect a stool sample in varying circumstances. Consistent content was perceived as true, free of bias, or aligned with previous experiences. Understandable content was content presented at the right literacy level, in a clear, accessible manner. Missing content included various recommendations for the intervention. Participants suggested notifying their doctor when they had completed the intervention, adding nutrition information, and providing more context for screening recommendations.

Participants were overall positive about the content and perceived the VHA‐delivered intervention as an opportunity: “with the virtual human…they have all that information just readily, as opposed to a doctor that may not think of something” (P103, FG2, print).

3.1.2.4. Social presence

Feeling physically or psychologically close (or distant), wanting to interact (or not), ascribing intentions, or using bodily cues or facial expressions to infer the VHA's psychological state was coded as high or low social presence. Participants desired social presence during healthcare discussions. “You look in my face, then we might can get somewhere. You reading that report, I wanna’ see that expression on your face” (P101, FG2, print).

Three cues triggered social presence: movement, fake versus real, and scariness/creepiness. Participants responded negatively to VHA 1's unnatural rocking motions and “robotic” movements, which were improved by VHA 3. When audio, mouth movements, and text subtitles were out of sync, participants were frequently annoyed. Hand gestures were described as a mix of distracting and enjoyable. Updating movements to look more natural using motion capture technology, provided improvement.

Fake versus real cues included questions regarding why the VHA was not a real person and requests to make her more realistic. Participants, who viewed print‐only prototypes, found it hard to imagine the VHA as human. By version 3, the VHA was more realistic and described in connection with intentions to get screening:

…she seemed like a real doctor…talkin’ to a real patient…I was listenin’ to her voice and how she was takin’ time and explainin’ step by step…She seemed like a real person that was really there talkin’ to you [about] what's goin’ on with your body, and you need to be checked. I wasn't thinkin’ about she was no video person. She was a real person, like I'm talkin’ to my doctor. It was like, “Oh, yeah, thanks, doctor, for helpin’ me out…Yeah, I'm gonna go be checked…” (P138, FG7, VER3)

Scariness/creepiness cues referenced fear‐evoking qualities of the VHA. Early versions were described as “vampires with fangs.” By version 3, modifications to reduce creepiness, such as adjusting features of the mouth, were successful.

3.1.3. Interactivity

Comments on interactivity occurred in nine out of 14 discussions and were coded 242 times. Four cues represented perceptions of interactivity: personalization/customization, choice and control, responsiveness, and ability to ask questions. These cues also conveyed social presence. Personalization/customization included participants asking if content could be adapted for younger populations. Participants also wanted more personalized feedback based on information they provided to the VHA. Choice and control included the ability to make different decisions or control features of the intervention. Perceptions of limited choice and control negatively affected user experience. Responsiveness was when the VHA reacted to users in a way that mimicked expected social cues. Unexpected actions were conspicuous. Finally, the ability to ask questions of the VHA was important.

3.1.4. Navigability

Perceptions of navigability were captured by comments coded as ease of navigating, transitions, and scaffolding/features. There were 111 navigability comments across all versions. Ease of navigating indicated participants were comfortable moving through, opening, and closing the intervention. Transition cues related to smooth changeovers between scenes. Scaffolding related to the structure and placement of features in the interface.

4. DISCUSSION

Findings provide a list of cues that influence Black women's perceptions of a VHA‐delivered intervention promoting CRC screening using FIT (Table S2). We suggest these cues shape credibility via social presence, expertise, and trustworthiness. Assessing the impact of these cues on information evaluation and behavior, particularly in the context of a web‐based, health intervention, may be particularly important to reduce screening barriers for Black women. By utilizing a user‐centered design approach and adapting content iteratively, we improved overall perceptions and willingness to engage with the intervention. Furthermore, culturally relevant VHAs may address documented barriers to CRC screening for Black women, by providing accessible, evidence‐based information about noninvasive screening options (e.g., FIT) and improving initiation of screening conversations during face‐to‐face interactions with clinicians.

4.1. Interplay of cues

Cues and heuristics may work together in a number of ways to shape credibility and message engagement. Shah and Oppenheimer's effort‐reduction framework describes a process that reduces the effort necessary to make a decision. 26 They propose that all heuristics reduce cognitive demand by allowing one to examine fewer cues; increase ease of retrieving and storing cues; simplify evaluation of cues; integrate less information; and/or examine fewer alternatives. An effort‐reduction framework provides important context for our findings regarding the declining frequency of some cues across adapted VHAs. For example, trustworthiness cues (voice, friendliness/likability, and appearance) were mentioned less frequently for version 3 than versions 1 and 2, while social presence comments became more positive. This suggests that when social presence was calibrated appropriately, users needed to examine fewer cues associated with trust.

Reducing cognitive demand may also have the benefit of enhancing attention to novel information. Novel content was the only content cue mentioned more frequently as VHA versions evolved. This suggests that as effort to process other cues decreased (due to modifications), more attention could be directed toward processing and encoding novel information. This finding warrants future research into how various design elements of VHA‐delivered messages affect cancer prevention behaviors, especially knowing that different audiences (e.g., smokers and certain age groups) process cancer‐related messages in different ways. 35 In other research, novel content has been associated with uncertainty, confusion, low perceptions of source credibility, and less willingness to adopt advocated behaviors. 36 Our study findings instead indicate that novel content cues resulted in positive evaluations of the intervention.

Cognitive demand may also be reduced if VHA‐delivered interventions use cues that are easy to retrieve and remember. Authority, clothing, and age were important cues for expertise. Existing heuristics of medical expertise, such as preferences for the VHA to wear a white lab coat and present as a middle‐aged doctor, may have shaped expectations. Activating preferred expertise cues likely increases one's ability to process information about the VHA's expertise.

Various aspects of visual design and messaging must also be considered for credibility. As the VHA became more responsive and less robotic, participants expressed increased enthusiasm to engage, share information with friends and family, and obtain CRC screening. Human‐like virtual images have been shown to be more engaging, attractive, and interesting compared to less human images. 37 However simply looking “more human” may not be sufficient for credibility, as another study found human‐like virtual images were associated with lower credibility compared to a less human images. 38

4.2. Study limitations

While our study identifies what cues are relevant to credibility in a web‐based intervention for Black women, it cannot address the extent to which all the cues contribute to VHA credibility or specify how the cues/heuristics led to credibility. This study demonstrates the acceptability of a gender‐ and race‐concordant VHA among Black women; findings may not be generalizable to other populations. Additionally, all study participants were from the southeast United States, and there may be regional differences in how people value cues.

4.3. Clinical implications

VHT provides opportunities to deliver systematic, guideline‐concordant CRC screening messages from a credible source. This may be particularly important for encouraging screening among Black women, as previous research indicates that lack of physician recommendation is one barrier among this population. VHT also may support a variety of health system goals, including engaging users in targeted communication and personal health tracking. 39 This paper demonstrates one way of incorporating participant perspective in the development processes of health interventions delivered through technology.

5. CONCLUSIONS

Research on how cues interact to produce persuasive health messages should account for users' cultural and social experiences. Experiences should be intentionally sought and applied to health promotion efforts in clinical settings. This study is unique in that it advances knowledge of testable relationships for domain‐specific cues. Future studies can build on these findings to hypothesize and test causal sequences between cues, heuristics, and credibility of behavior‐change messages.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Authors report no conflicts of interest.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Supporting information

Supplementary material 1

Supplementary material 2

Supplementary material 3

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported by the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, Award #R01CA207689. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent official views of the NIH.

References

REFERENCES

- 1. DeSantis CE, Miller KD, Goding Sauer A, Jemal A, Siegel RL. Cancer statistics for African Americans. CA Cancer J Clin. 2019;69(3):211–233. http://doi.wiley.com/10.3322/caac.21555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. American Cancer Society . Colorectal Cancer Facts & Figures 2017‐2019. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lai Y, Wang C, Civan JM, et al. Effects of cancer stage and treatment differences on racial disparities in survival from colon cancer: a United States population‐based study. Gastroenterology. 2016;150(5):1135‐1146. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26836586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Coughlin SS, Blumenthal DS, Seay SJ, Smith SA. Toward the elimination of colorectal cancer disparities among African Americans. J Racial Ethn Heal Disparities. 2016;3(4):555–564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Thompson HS, Shelton RC, Mitchell J, Eaton T, Valera P, Katz A. Inclusion of underserved racial and ethnic groups in cancer intervention research using new media: a systematic literature review. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2013(47):216–223. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3881998/pdf/lgt031.pdf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wolf AMD, Fontham ETH, Church TR, et al. Colorectal cancer screening for average‐risk adults: 2018 guideline update from the American Cancer Society. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68(4):250‐281. http://doi.wiley.com/10.3322/caac.21457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force . Final update summary: colorectal cancer: screening . 2015. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/colorectal-cancer-screening.

- 8. Williams R, White P, Nieto J, Vieira D, Francois F, Hamilton F. Colorectal cancer in African Americans: an update. Clin Transl Gastroenterol. 2016;7(7):e185 http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27467183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. White PM, Sahu M, Poles MA, Francois F. Colorectal cancer screening of high‐risk populations: a national survey of physicians. BMC Res Notes. 2012;5(64):1–6. http://www.biomedcentral.com/1756-0500/5/64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Palmer RC, Midgette LA, Dankwa I. Colorectal cancer screening and African Americans: findings from a qualitative study. Cancer Control. 2008;15(1):72‐79. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/107327480801500109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bibbins‐Domingo K, Grossman DC, Curry SJ, et al. Screening for colorectal cancer. J Am Med Assoc. 2016;315(23):2564 http://jama.jamanetwork.com/article.aspx?doi=10.1001/jama.2016.5989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Siba Y, Culpepper‐Morgan J, Schechter M, et al. A decade of improved access to screening is associated with fewer colorectal cancer deaths in African Americans: a single‐center retrospective study. Ann Gastroenterol. 2017;30(5):518–525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Pasick RJ, D'Onofrio CN, Otero‐Sabogal R. Similarities and differences across cultures: questions to inform a third generation for health promotion research. Health Educ Behav. 1996;23(1 suppl):142‐161. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wilkowska W, Brauner P, Ziefle M. Rethinking technology development for older adults: A responsible research and innovation duty In: Pak R, McLaughlin AC, eds. Aging, Technology and Health. 1 ed London, England: Academic Press; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kim S, Gajos KZ, Muller M, Grosz BJ. Acceptance of mobile technology by older adults: a preliminary study. In: Proceedings of the 18th International Conference on Human‐Computer Interaction with Mobile Devices and Services, MobileHCI ’16. Florence, Italya; New York, NY: Association for Computing Machinery; 2016. 10.1145/2935334.2935380. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hecht ML, Krieger JLR. The principle of cultural grounding in school‐based substance abuse prevention: the drug resistance strategies project. J Lang Soc Psychol. 2006;25(3):301‐319. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Dworkin M, Chakraborty A, Lee S, et al. A realistic talking human embodied agent mobile phone intervention to promote HIV medication adherence and retention in care in young HIV‐positive African American men who have sex with men: qualitative study. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2018;6(7):e10211 http://mhealth.jmir.org/2018/7/e10211/. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wells KJ, Vázquez‐Otero C, Bredice M, et al. Acceptability of an embodied conversational agent‐based computer application for hispanic women HHS public access. Hisp Health Care Int. 2015;13(4):179‐185. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4699427/pdf/nihms742958.pdf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Zhou S, Bickmore T, Paasche‐Orlow M, Jack B. Agent‐user concordance and satisfaction with a virtual hospital discharge nurse. In: Lecture Notes in Computer Science (including subseries Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence and Lecture Notes in Bioinformatics). Springer; 2014:528‐541.

- 20. Lucas GM, Gratch J, King A, Morency L‐P. It's only a computer: virtual humans increase willingness to disclose. Comput Human Behav. 2014;37:94‐100. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0747563214002647. [Google Scholar]

- 21. DeFinney S, Dean M, Loiselle E, Saraceno J. All children are equal, but some oare more equal than others: minoritization, structural inequities, and social justice praxis in residential care. Int J Child Youth Fam Stud. 2011;2(3/4):361 http://dspace.library.uvic.ca/bitstream/handle/1828/5391/deFinney_Sandrina_IJCYFS_2011.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y. [Google Scholar]

- 22. O'Keefe DJ. Persuasion: Theory and Research. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hass R. Effects of source characteristics on cognitive responses and persuasion In: Petty RE, Ostrom TM, Brock TC, eds. Cognitive responses in persuasion. Hillsdale, MI: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.; 1988:141‐175. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ohanian R. Construction and validation of a scale to measure celebrity endorsers' perceived expertise, trustworthiness, and attractiveness. J Advert. 1990;19(3):39‐52. http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/00913367.1990.10673191. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Xu K, Liao T. Explicating cues: a typology for understanding emerging media technologies. J Comput Commun. 2019;25(1):32–43. https://academic.oup.com/jcmc/advance-article/doi/10.1093/jcmc/zmz023/5673271. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Shah AK, Oppenheimer DM. Heuristics made easy: an effort‐reduction framework. Psycholocigal Bull. 2008;134(2):207‐222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Chaiken S. Heuristic versus systematic information processing and the use of source versus message cues in persuasion. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1980;39(5):752‐766. http://doi.apa.org/getdoi.cfm?doi=10.1037/0022-3514.39.5.752. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Shyam Sundar S. The MAIN model: a heuristic approach to understanding technology effects on credibility In: Metzger MJ, Flanagin AJ, eds. Digital Media, Youth, and Credibility. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press; 2008:73‐100. https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/de80/aa094f380342a632eadb0ee8d4221e8920ba.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Oh CS, Bailenson JN, Welch GF. A systematic review of social presence: definition, antecedents, and implications. Front Robot AI. 2018;5(114):1–35. https://doi.org/10.3389/frobt.2018.00114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Griffin L, Lee D, Jaisle A, et al. Creating an mHealth app for colorectal cancer screening: user‐centered design approach. JMIR Hum Factors. 2019;6(2):e12700 http://humanfactors.jmir.org/2019/2/e12700/. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bennett LM, Gadlin H. Collaboration and team science: from theory to practice. J Investig Med. 2012;60(5):768‐775. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22525233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Campbell JL, Quincy C, Osserman J, Pedersen OK. Coding in‐depth semistructured interviews: problems of unitization and intercoder reliability and agreement. Sociol Methods Res. 2013;42(3):294‐320. http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0049124113500475. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hsieh H‐F, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15(9):1277‐1288. http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/1049732305276687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hocevar KP, Metzger M, Flanagin AJ, Hocevar KP, Metzger M, Flanagin AJ. Source credibility, expertise, and trust in health and risk messaging Oxford Res Encycl Commun. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press; 2017. http://oxfordre.com/communication/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228613.001.0001/acrefore-9780190228613-e-287. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Lang A. Using the limited capacity model of motivated mediated message processing to design effective cancer communication messages. J Commun. 2006;56(suppl):S57–S80. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/228677202. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Chang C. Motivated processing. Sci Commun. 2015;37(5):602‐634. http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/1075547015597914. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Koda T. Agents with Faces: A Study on the Effects of Personification of Software Agents. Massachusetts Institute of Technology; 1996. http://alumni.media.mit.edu/∼tomoko/thesis.html. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Nowak KL. The influence of anthropomorphism and agency on social judgment in virtual environments. J Comput Commun. 2006;9(2). https://academic.oup.com/jcmc/article/4614465. [Google Scholar]

- 39. World Health Organization . WHO guideline: recommendations on digital interventions for health system strengthening. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2019. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/311977/WHO-RHR-19.8-eng.pdf?ua=1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material 1

Supplementary material 2

Supplementary material 3

Data Availability Statement

The data that support our findings are available upon request.

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.