Abstract

Bacterial messenger RNAs (mRNAs) are composed of 5′ and 3′ untranslated regions (UTRs) that flank the coding sequences (CDSs). In eukaryotes, 3′UTRs play key roles in post-transcriptional regulatory mechanisms. Shortening or deregulation of these regions is associated with diseases such as cancer and metabolic disorders. Comparatively, little is known about the functions of 3′UTRs in bacteria. Over the past few years, 3′UTRs have emerged as important players in the regulation of relevant bacterial processes such as virulence, iron metabolism, and biofilm formation. This MiniReview is an update for the different 3′UTR-mediated mechanisms that regulate gene expression in bacteria. Some of these include 3′UTRs that interact with the 5′UTR of the same transcript to modulate translation, 3′UTRs that are targeted by specific ribonucleases, RNA-binding proteins and small RNAs (sRNAs), and 3′UTRs that act as reservoirs of trans-acting sRNAs, among others. In addition, recent findings regarding a differential evolution of bacterial 3′UTRs and its impact in the species-specific expression of orthologous genes are also discussed.

Keywords: 3′UTR, bacteria, gene expression regulation, RNA-binding proteins (RBPs), ncRNAs (non-coding RNAs), regulatory small RNAs (sRNAs), post-transcription regulation

Introduction

Post-transcriptional regulation in bacteria has emerged as an essential layer to tightly control gene expression. Different regulatory elements are involved in the modulation of messenger RNA (mRNA) elongation, stability, and translation. Genomes encode a large variety of RNA-binding proteins (RBPs) and regulatory RNAs that target mRNAs and modify their expression in diverse ways. Among RBPs, ribonucleases (RNases) play key roles in both the maturation and degradation of mRNAs, which result in improved translation and disposal of no longer required transcripts, respectively. Other RBPs such as RNA chaperones, RNA helicases, and RNA methyltransferases modify the susceptibility of transcripts to RNases and the accessibility of mRNAs to ribosomes. Some of these RBPs also assist in the interaction between regulatory RNAs and their targeting mRNAs or regulate the formation of transcriptional terminator/anti-terminator structures (Van Assche et al., 2015; Holmqvist and Vogel, 2018; Woodson et al., 2018). Regarding regulatory RNAs, two large categories can be distinguished: small RNAs (sRNAs) and cis-encoded antisense RNAs (asRNAs). sRNAs target mRNAs in trans and are often encoded in a different genomic location from their targets. The nucleotide pairing between a sRNA and its target mRNA is usually imperfect and it often requires the assistance of RNA chaperones (Wagner and Romby, 2015; Dutcher and Raghavan, 2018). In contrast, asRNAs are encoded in the opposite DNA strand of their targets and thus their interaction produces a perfect pairing between both RNA molecules. The resultant RNA duplexes can be processed by double-stranded endoribonucleases such as RNase III (Georg and Hess, 2011; Toledo-Arana and Lasa, 2020). Besides these regulatory RNAs, the untranslated regions (UTRs) of the mRNAs may contain regulatory elements, which modulate the expression of their own mRNAs in different ways. Monocistronic and polycistronic mRNAs are comprised of two UTRs that flank the coding sequence(s) (CDSs), the 5′- and the 3′UTR, respectively. A major breakthrough in the discovery of functional bacterial UTRs was the genome-wide transcriptomic mapping, which showed that their lengths were greater than previously anticipated, suggesting that they could act as a reservoir of additional regulatory elements (Toledo-Arana et al., 2009). This was more evident for the 5′UTRs, which have been well-known for including riboswitches and thermosensors that control the expression of their downstream CDSs (Loh et al., 2018; Pavlova et al., 2019). In addition, several examples of long 5′UTRs have been described to overlap the mRNAs encoded in the opposite DNA strand (Toledo-Arana et al., 2009; Sesto et al., 2012; Toledo-Arana and Lasa, 2020). In contrast, little is known about the 3′UTRs functions, probably because post-transcriptional regulation studies mainly focused on sRNAs and 5′UTRs. Additionally, the first RNA-sequencing techniques did not map the 3′ ends, leaving in the dark relevant information about them. However, recent discoveries have brought to light that 3′UTRs can play relevant roles by tightly modulating gene expression in bacteria through diverse mechanisms.

In eukaryotes, 3′UTRs are far longer than 5′UTRs and they constitute key components of the overall post-transcriptional regulation (Pesole et al., 2002; Mazumder et al., 2003). Eukaryotic 3′UTRs possess a wide variety of regulatory motifs that are recognized by microRNAs (miRNAs) and RBPs to control mRNA stability, localization, and translation (Mazumder et al., 2003; Mayr, 2017). The AU-rich and GU-rich elements (AREs and GREs, respectively) constitute good examples of this as their sequences are recognized by proteins that favor mRNA degradation (Halees et al., 2008, 2011; Vlasova et al., 2008; von Roretz et al., 2011). The polyA tail (a stretch of as located in the 3′ end of the mRNA) is another element that can determine mRNA stability and, as a result, protein levels. Alternative 3′UTRs not only affect mRNA stability and translation but also control mRNA localization (Tushev et al., 2018). There are cases in which a poly(A)-binding protein (PABP) can cause a positive effect on their mRNA targets by promoting translation (Mayr, 2017). Once the PABP binds to the poly(A), it interacts with translation factor eIF4G which, in turn, binds the cap-binding protein eIF4E that is bound to the capped 5′ end. This generates an mRNA circularization that promotes the engagement of terminating ribosomes to a new round of translation of the same mRNA, thus, enhancing protein synthesis (Wells et al., 1998; Alekhina et al., 2020).

Interestingly, the length of the eukaryotic 3′UTRs varies according to the protein encoded in the mRNA. Frequently, mRNAs that encode housekeeping proteins that are highly expressed possess single 3′UTRs. In contrast, mRNAs expressing regulatory proteins, which are tightly regulated, contain multiple alternative 3′UTRs (Lianoglou et al., 2013). Moreover, there is a number of examples of mRNAs that produce alternative 3′UTRs depending on the cell tissues where they will be expressed (Mayr, 2016). Alternative 3′UTRs can modulate, among others, the localization of membrane proteins in human cells. During mRNA translation, 3′UTRs work as scaffolds that facilitate the binding of proteins to the nascent protein, directing their transport or function (Berkovits and Mayr, 2015). Deregulation or shortening of 3′UTRs is associated with diverse diseases such as cancer or metabolic disorders (Khabar, 2010; Mayr, 2017). It is noteworthy that there is a direct correlation between the 3′UTR length and the evolutionary age and complexity of organisms, with the longest 3′UTRs being found in the human genome. Contrary to this, 5′UTRs have preserved an almost constant length through the course of evolution. This 3′UTR evolutionary lengthening suggests that 3′UTR-mediated post-transcriptional regulation must have played a significant role in generating functional differences between species (Mazumder et al., 2003; Mayr, 2017).

Over the past few years, several of the 3′UTR-mediated regulatory mechanisms that were initially described for eukaryotes have also been discovered in bacteria. In this review, the current known mechanisms to control gene expression in bacteria through 3′UTRs are addressed. In addition, the differential evolution found within this bacterial mRNA region and the differences it has created between mRNAs that encode orthologous proteins is also discussed.

Identification of 3′UTRs in Bacteria

The 3′UTR is the section of nucleotides found between the translation stop codon and the transcription termination site in an mRNA molecule. Before the transcriptomic era, the efforts in understanding transcript boundaries were biased toward the 5′ end. Several reasons could explain this bias. On the one hand, the 5′ end was required for identifying promoter sequences as well as putative transcriptional regulatory regions and RNA secondary structures that contributed to gene expression control. On the other hand, the lack of the 3′ poly(A) tail in bacterial mRNAs prevented a direct reverse transcription priming from the 3′ end, rendering their mapping challenging. The 3′ end of particular transcripts was identified by classical S1 nuclease mapping [protocol updated in Sambrook and Russell (2006)] and, later on, through a modified 5′/3′ RACE method (rapid amplification of cDNA ends) that simultaneously mapped 5′ and 3′ ends of RNA ligase-circularized RNAs (Britton et al., 2007). At the same time, it was a general belief that the 3′UTRs would not play any major roles in bacterial gene expression control and that their functions were restricted to transcript termination and protection of the mRNAs from RNases. This perception quickly changed with the accomplishment of the first genome-wide transcriptomic maps. Although the resolution of these transcriptomes was restricted by the technologies used at that time (e.g., high-resolution tiling arrays), they started to unveil how 3′UTRs could play more impactful roles than initially anticipated (Rasmussen et al., 2009; Toledo-Arana et al., 2009; Broeke-Smits et al., 2010). Later on, thanks to the development of high-throughput stranded RNA sequencing (RNA-seq), the identification of transcript boundaries was significantly simplified. RNA-seq confirmed the relevance of 3′UTRs, showing that they encode a wide variety of regulatory elements (for details see following sections). Nowadays, genome-wide maps of 3′ ends at single-nucleotide resolution of bacteria grown in different conditions can be obtained by Term-seq, which directly sequences exposed RNA 3′ ends (Dar et al., 2016). This has been recently used to determine and compare the 3′ ends from bacterial models such as Escherichia coli, Bacillus subtilis, Listeria monocytogenes, Enterococcus faecalis, and Staphylococcus aureus (Dar et al., 2016; Dar and Sorek, 2018b; Menendez-Gil et al., 2020). In addition, other RNA-seq based techniques that were envisioned for the identification of RNA-RNA and RNA-protein interactions and ribonuclease processing sites have also provided the scientific community with novel putative functional 3′UTR candidates. For example, the RIL-seq (RNA interaction by ligation and sequencing), RIP-seq (RNA immunoprecipitation followed by RNA sequencing), TIER-seq (transiently-inactivating-an-endoribonuclease-followed-by-RNA-seq) and CLASH (UV cross-linking, ligation, and sequencing of hybrids) methods have revealed dozens of sRNAs candidates originated from 3′UTRs of several enterobacterial species (Holmqvist et al., 2016, 2018; Melamed et al., 2016, 2019; Chao et al., 2017; Hoyos et al., 2020; Huber et al., 2020; Iosub et al., 2020). Combining these technologies with those dedicated to 5′ and 3′ end mapping (Sharma et al., 2010; Dar et al., 2016) would complete the bacterial transcriptomic landscapes and their RNA-RNA and RNA-protein network interactions, which are essential for understanding post-transcriptional regulatory mechanisms, including those involving 3′UTRs.

Bacterial 3′UTRs Are Longer Than Previously Expected

The 3′UTR usually harbors the transcriptional termination signal, which could be an intrinsic terminator or a Rho utilization (rut) site (Peters et al., 2011). The intrinsic terminator consists of a hairpin structure followed by a U-tract that promotes transcript release from the RNA polymerase (RNAP) (Rho-independent termination), while the rut site recruits the Rho protein to produce a Rho-dependent termination. When Rho interacts with rut, its ATPase activity is triggered, providing it with the necessary energy to translocate along the mRNA. Transcription termination occurs thanks to the Rho helicase activity that causes a dissociation of the RNAP from the transcript (Peters et al., 2011). Rho is widespread in bacteria, however, Rho-dependent termination is more common in Gram-negative bacteria whereas in Gram-positive bacteria intrinsic terminators seem to be the norm (Ciampi, 2006). The average length of an intrinsic terminator was estimated in S. aureus to be around 30 nucleotides (Ruiz de Los Mozos et al., 2013). Therefore, a 3′UTR of 40-50 nt long would be sufficient to allocate a functional intrinsic terminator. However, the mapping of 3′ ends by genome-wide RNA sequencing methods in bacteria revealed that several 3′UTRs were much longer than previously anticipated (Broeke-Smits et al., 2010; Ruiz de Los Mozos et al., 2013; Dar et al., 2016; Dar and Sorek, 2018b). In S. aureus, more than 30% of the mapped 3′UTRs showed lengths above 100 nt. This was a strong evidence indicating that 3′UTRs could allocate additional regulatory elements (Ruiz de Los Mozos et al., 2013).

Long 3′UTRs are generated when the transcriptional terminator signals are located far away from their corresponding translational stop codons. In addition, since bacterial transcriptional termination mechanisms are not always effective in dissociating the RNAP from the nascent transcript, alternative read-through-mediated transcripts may also be generated. In Rho-independent termination, the level of read-through is proportional to the strength of the intrinsic terminator. The effectiveness of these terminators is favored by several factors such as the U-tract located immediately downstream of the hairpin structure, which promotes disassociation from the RNAP (Cambray et al., 2013; Chen et al., 2013). Other elements involve the enrichment of GC nucleotides at the stem of the hairpin, which favors its folding (Chen et al., 2013). Conversely, certain RBPs can induce transcription elongation by forcing the RNA polymerase to ignore the intrinsic transcriptional termination signal and thus generate longer alternative transcripts (Phadtare et al., 2002; Goodson et al., 2017; Goodson and Winkler, 2018).

Regarding Rho-dependent termination, several investigations depict Rho as a key factor that controls pervasive read-through transcription in bacteria. Deletion of the rho gene or inhibition of Rho activity using bicyclomycin causes transcriptional read-through (Nicolas et al., 2012; Mäder et al., 2016; Bidnenko et al., 2017; Dar and Sorek, 2018b).

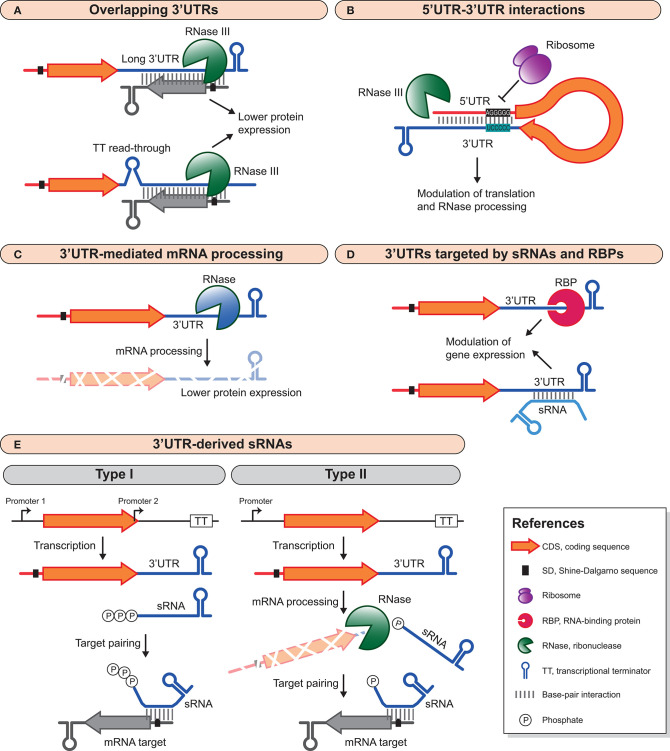

Since bacterial genomes are compact and the distance between CDSs is often short, when transcriptional terminator signals between convergent genes are missing and/or transcriptional read-through occurs, long antisense overlapping 3′UTRs are produced (Hernández et al., 2006; Toledo-Arana et al., 2009; Arnvig et al., 2011; Lasa et al., 2011; Nicolas et al., 2012; Moody et al., 2013; Mäder et al., 2016; Stazic and Voss, 2016; Bidnenko et al., 2017; Huang et al., 2020; Toledo-Arana and Lasa, 2020) (Figure 1A). In addition, more complex transcriptional organizations like operons containing a gene(s) that is transcribed in the opposite direction to the rest of the operon are also known for generating long overlapping transcripts (Lasa et al., 2011; Sáenz-Lahoya et al., 2019). The outcome is usually the development of large double-stranded RNA regions that are processed by RNase III in both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria (Lasa et al., 2011, 2012; Gatewood et al., 2012; Lioliou et al., 2012; Lybecker et al., 2014; Huang et al., 2020). Interestingly, overlapping 3′UTRs are widely distributed in bacteria and constitute an abundant source of antisense RNAs (Arnvig et al., 2011; Lasa et al., 2011; Ruiz de Los Mozos et al., 2013). These antisense mechanisms, which often involve mRNAs encoding proteins with opposing functions and whose expression is mutually regulated, are examples of the excludon concept (Sesto et al., 2012).

Figure 1.

Different 3′UTR-mediated regulatory mechanisms in bacteria. (A) Long 3′UTRs and transcriptional read-through can produce overlapping 3′UTRs that modulate the expression of convergent genes. These overlapping double-stranded RNA regions are processed by RNase III, which ultimately decreases protein expression. (B) 3′UTRs can interact with the 5′UTR of the same mRNA to modulate mRNA stability and translation. This interaction can inhibit translation and recruit RNases for mRNA degradation, or it can promote mRNA stability by impairing RNase processing. (C) RNases can specifically target 3′UTRs to process mRNAs and modify their half-life and protein expression yield. (D) sRNAs and RBPs can target 3′UTRs to modulate mRNA expression. This interaction can be both positive, by blocking RNase processing and enhancing mRNA stability, or negative by promoting inhibition of translation and RNase processing. (E) 3′UTRs are also reservoirs of trans-acting sRNAs than can be generated by an internal promoter within or immediately downstream of the CDS (type I) or by mRNA processing (type II). For examples, see text and Table 1.

In B. subtilis, Rho inhibition impairs the correct switch between motility, biofilm formation and sporulation. Rather than considering this as a pleiotropic effect, Bidnenko et al. demonstrated that the control of these opposite phenotypes was determined by a specific architecture of the Rho-controlled transcriptome, which involved several overlapping 3′UTRs. The different required elements appeared to be organized for the simultaneous activation of one phenotype while repressing the alternative ones and, thus, providing the excludon with a biological meaning (Bidnenko et al., 2017). It is noteworthy that Rho-dependent termination is also susceptible to regulation by sRNAs (Bossi et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2015; Chen et al., 2019).

Finally, there is knowledge of an additional complex genomic architecture surrounding riboswitches that could further increase the source of long 3′UTRs. Riboswitches are regulatory elements located at the 5′UTRs that control the expression of the downstream genes in function of the concentration of a specific metabolite. The riboswitch sensor induces a conformational change in the expression platform upon binding of such metabolite, leading to changes in the transcript elongation and/or the translation of downstream genes (Serganov and Nudler, 2013). Interestingly, riboswitches that work as attenuators can also control the transcript termination of upstream genes. This occurs when genes located upstream of riboswitches lack a transcriptional termination signal. Therefore, transcription of upstream genes may terminate or continue depending on the riboswitch configuration. If the riboswitch is in a transcriptional OFF-configuration, the transcription of upstream genes stops, as these riboswitches form a hairpin that works as an intrinsic terminator. The regenerated transcript would contain a long 3′UTR including the riboswitch sequence. In contrast, if the riboswitch is in an ON-configuration, the result is a long polycistronic transcript that includes the initial gene plus the riboswitch and the downstream genes. This transcriptomic configuration was initially described in L. monocytogenes, but it is present in several bacterial species (Toledo-Arana et al., 2009; Ruiz de Los Mozos et al., 2013). The consequences of this transcriptomic architecture on the expression and function of the genes involved still needs to be elucidated.

The evidence of different regulatory factors that modulate both intrinsic and Rho-dependent transcriptional termination mechanisms opens the possibility to transcriptional read-through events as an additional regulatory layer. This would imply that bacterial chromosomes contain larger transcriptionally-connected chromosomic regions that go beyond the classical operon configurations known so far (Toledo-Arana and Lasa, 2020).

3′UTRs as Modulators of Gene Expression

Besides the reciprocal antisense regulation exerted by the 3′UTR-overlapping mRNAs explained above, 3′UTRs can modulate gene expression in many other ways (Figure 1). Some 3′UTRs generate small regulatory RNAs that act in trans by targeting mRNAs, while others modulate the expression of their own mRNA. Additionally, 3′UTRs may be targeted by sRNAs and/or RBPs to modify 3′UTR function.

3′UTRs That Interact With the 5′UTRs of the Same mRNA Molecule

The first example that showed a bacterial 3′UTR modulating the expression of the protein encoded in its own mRNA was the paradigmatic RNAIII of S. aureus described by Balaban and Novick (Balaban and Novick, 1995). RNAIII is a dual-function RNA that encodes the δ-hemolysin and a regulatory trans-acting RNA that base pairs with several virulence-related mRNAs to modulate their expression (Bronesky et al., 2016; Raina et al., 2018). It was shown that translation of δ-hemolysin occurred one hour after transcription of RNAIII. This delay was non-existent when the 3′UTR was deleted. In-silico RNA structural analyses predicted a 5′UTR-3′UTR interaction as a plausible cause for said post-transcriptional regulation (Balaban and Novick, 1995). The long-range 5′UTR-3′UTR interaction was later on validated by chemical and enzymatic probing analyses, which demonstrated the base-pairing of residues A24-G30 and U452-458 (Benito et al., 2000). Whether this 5′UTR-3′UTR interaction directly modulates δ-hemolysin translation remains to be demonstrated by site-directed mutagenesis.

Several years passed until novel functional 3′UTRs were characterized. Our group unveiled that the 3′UTR of the icaR mRNA in S. aureus interacted with the ribosome binding site (RBS) of its own mRNA through a UCCCC sequence that behaved as an anti-RBS motif (Figure 1B). This 5′UTR-3′UTR interaction inhibited translation initiation of the IcaR protein and produced a double-stranded RNA substrate that was cleaved by RNase III, leading to mRNA degradation. IcaR is the repressor of the ica operon, which encodes the main exopolysaccharidic compound (PIA-PNAG) of the S. aureus biofilms. Therefore, the icaR 5′UTR-3′UTR interaction favored biofilm formation (Ruiz de Los Mozos et al., 2013). A few years later, a 14 nt interaction between the 3′UTR and the 5′UTR of the hbs mRNA in B. subtilis was uncovered. This 5′-3′UTR interaction protected the hbs mRNA from RNase Y cleavage at the 5′UTR (Braun et al., 2017). The regulatory 5′-3′UTRs interactions are in agreement with a recent study in B. subtilis that shows how transcription and translation are fundamentally disjointed (Johnson et al., 2020). Faster RNAPs in combination with highly structured 5′UTRs would favor the production of ribosome-free mRNAs. These would likely be more susceptible to post-transcriptional regulatory processes since they would not be interfered by translating ribosomes (Johnson et al., 2020). Whether this type of 5′-3′UTR interaction mechanism applies to the regulation of other bacterial genes requires further investigations.

3′UTR-Mediated mRNA Processing

Several examples of 3′UTRs that are involved in mRNA processing have recently been revealed for different bacterial species. 3′UTRs can harbor RNase cleavage sites that, upon processing, modify the stability and turnover of mRNAs (Figure 1C). It has been demonstrated that most of these bacterial 3′UTRs act as independent modules. Cloning the 3′UTRs downstream of the gfp or lacZ reporter genes proved that the 3′UTRs retained their functional capabilities since they were still being targeted by the same RNases. Moreover, the regulatory effect on the expression of the upstream reporter genes was similar to the one observed for their original CDSs (Maeda and Wachi, 2012; López-Garrido et al., 2014; Zhu et al., 2015; Zhao et al., 2018; Menendez-Gil et al., 2020).

In S. aureus, the rpiRc and ftnA 3′UTRs are able to modify their mRNAs stability (Menendez-Gil et al., 2020). RpiRc is a transcriptional repressor of the Agr quorum sensing system and therefore a virulence regulator (Zhu et al., 2011; Balasubramanian et al., 2016; Gaupp et al., 2016), while FtnA is an iron storage protein that modulates intracellular iron availability (Morrissey et al., 2004; Zühlke et al., 2016). Deletion of both 3′UTRs increase the mRNA and protein levels of their respective genes, indicating that the expression of these proteins may be modulated by still unidentified ribonucleases (Menendez-Gil et al., 2020).

In Yersinia pestis, several long 3′UTRs with AU-rich motifs induce mRNA degradation (Zhu et al., 2015; Zhao et al., 2018). Among them, the hmsT 3′UTR seems of relevance due to its ability to modulated c-di-GMP metabolism and biofilm formation (Zhu et al., 2015). Note that AREs are key cis-acting factors involved in the regulation of many important cellular processes in eukaryotes, such as stress response, inflammation, immuno-activation, apoptosis, and carcinogenesis. AREs are located in the 3′UTRs of short-lived mRNAs, which function as a signal for rapid degradation (Bakheet et al., 2006; Halees et al., 2008). Multiple RBPs regulate the transport, stability, and translation of eukaryotic mRNAs containing AREs (García-Mauriño et al., 2017). Some of the Y. pestis AU-rich 3′UTRs behave in a similar way since they are specifically targeted by the polynucleotide phosphorylase (PNPase), a 3′-5′ exoribonuclease, and might be also acting as inductors of rapid mRNA degradation (Zhao et al., 2018).

Other examples of mRNAs containing AU-rich motifs in their 3′UTRs that promote mRNA processing are found in Salmonella and Corynebacterim glutamicum (Maeda and Wachi, 2012; López-Garrido et al., 2014). PNPase and RNase E target the 3′UTR of the hilD mRNA, which encodes one of the main transcriptional activators of Salmonella pathogenicity island 1 (SPI-1) (López-Garrido et al., 2014). Similarly, RNase E/G processes the aceA mRNA of C. glutamicum. This mRNA encodes the isocitrate lyase protein, an enzyme of the glyoxylate cycle (Maeda and Wachi, 2012). Since PNPase activity is inhibited by hairpin structures such as those found in intrinsic terminators (Hui et al., 2014; Dar and Sorek, 2018a), it is possible that AU-rich 3′UTRs are initially cleaved by RNase E providing an accessible 3′ end for the action of PNPase. Note that RNase E is an endoribonuclease that preferentially targets AU-rich regions in single-stranded RNAs (McDowall et al., 1994). Chao et al. demonstrated that RNase E sites were enriched around mRNA stop codons. The RNase E cleavage eliminates 3′ end protective hairpin structures, rendering processed 3′ ends accessible to degradation by 3′/5′ exoribonucleases such as PNPase (Chao et al., 2017; Dar and Sorek, 2018a). This observation has been recently confirmed in Streptococcus pyogenes, where RNase Y-processed 3′ ends are subsequently trimmed by PNPase and YhaM. RNase Y is the functional RNase E ortholog in Gram-positive bacteria (Broglia et al., 2020).

3′UTRs That Are Targeted by RBPs and sRNAs

The 3′UTR-mediated mRNA processing can be inhibited by RBPs (Figure 1D). For example, the expression of the E. coli aconitase (acnB) mRNA is autoregulated by its own protein. AcnB is an enzyme of the TCA (tricarboxylic acid) cycle that uses iron as a cofactor. However, upon iron starvation it becomes an autoregulatory RBP (apo-AcnB). The apo-AcnB protein binds its own mRNA at a stem-loop located in the 3′UTR, which is in close proximity to an RNase E cleavage site, preventing the acnB mRNA degradation by RNase E (Benjamin and Massé, 2014). Likewise, global regulatory RNA chaperones including Hfq, CsrA and ProQ also bind 3′UTRs (Holmqvist et al., 2016, 2018; Potts et al., 2017). Among them, ProQ targets secondary structures of 3′UTRs in Salmonella and E. coli to protect their mRNAs from RNases. Such is the case of the cspE mRNA, which is recognized by ProQ to prevent RNase II cleavage (Holmqvist et al., 2018). Hfq has preference for 3′UTRs that produce regulatory RNAs (Holmqvist et al., 2016). In comparison to Hfq and ProQ, the number of 3′UTRs recognized by CsrA is much lower and its regulatory role over this region, if any, remains unknown (Potts et al., 2017).

Eukaryotic 3′UTRs are targeted by microRNAs to modulate mRNA expression (Krol et al., 2010; Saliminejad et al., 2019). Recently, bacterial 3′UTRs have been also shown to be targeted by trans-acting regulatory RNAs (El-Mouali et al., 2018; Bronesky et al., 2019) (Figure 1D). In S. aureus, the RsaI sRNA binds to the 3′UTR of the icaR mRNA, modulating the PIA-PNAG exopolysaccharide biosynthesis. Interestingly, the catabolite control protein A (CcpA) represses RsaI expression when glucose is available in the culture medium. Therefore, the RsaI-icaR 3′UTR interaction links the glucose metabolism with the biofilm formation process (Bronesky et al., 2019). Since RsaI binds to a different region to that of the UCCCC motif (required for the icaR 5′UTR-3′UTR interaction), it is speculated that RsaI might help stabilizing the circularization of the mRNA and, ultimately, inhibit IcaR translation (Bronesky et al., 2019). In Salmonella, the trans-acting sRNA Spot 42 connects metabolism and virulence by interacting with the long 3′UTR of the hilD mRNA (El-Mouali et al., 2018). Spot 42 is repressed by the cAMP-activated global transcriptional regulator CRP. When environmental and/or physiological signals disrupt the CRP-dependent Spot 42 repression, Spot 42 becomes available to bind to the hilD 3′UTR in a Hfq-dependent manner. Spot 42 binding activates HilD protein expression and thereby induces the expression of HilD-dependent virulence genes (López-Garrido et al., 2014; El-Mouali et al., 2018; El-Mouali and Balsalobre, 2019).

3′UTRs That Produce trans-Acting sRNAs

3′UTRs have also emerged as reservoirs of trans-acting sRNAs (Kawano et al., 2005; Chao et al., 2012; Miyakoshi et al., 2015b). 3′UTR-derived sRNAs can be generated either by the presence of an internal promoter located within or immediately downstream of the CDS (type I) or by the processing of an mRNA transcript at the 3′UTR (type II). Therefore, type I sRNAs carry a triphosphate at their 5′ ends while type II sRNAs exhibit monophosphate 5′ ends (Miyakoshi et al., 2015b) (Figure 1E).

Although 3′UTR-derived sRNAs have been described in several bacterial species, most of them have been characterized in Gram-negative bacteria (Table 1). Interestingly, type II sRNAs are more abundant than type I, highlighting the relevance of specific RNase cleavage sites present within the 3′UTRs. The biogenesis of many type II 3′UTR-derived sRNAs depends on the mRNA cleavage by RNase E, whose target sites are enriched around the mRNA stop codon (Chao et al., 2017). Table 1 summarizes relevant bacterial 3′UTR-derived sRNA examples. The sRNA targets and their physiological roles are also indicated in this table. These examples suggest that 3′UTR-derived sRNAs are widely distributed in bacteria and that they control a broad variety of biological processes. For example, the type I MicL sRNA modulates envelope stress by repressing the synthesis of Lpp, a major outer membrane lipoprotein in E. coli (Guo et al., 2014), while DapZ and MicX control the expression of the major ABC transporters in Salmonella and V. cholerae, respectively (Davis and Waldor, 2007; Chao et al., 2012). This is further exemplified by the type II SorX, RsaC and s-SodF sRNAs that participate in the oxidative stress response of Rhodobacter sphaeroides, S. aureus and Streptomyces coelicolor, respectively (Kim et al., 2014; Peng et al., 2016; Lalaouna et al., 2019). Besides, 3′UTR-derived sRNAs also participate in autoregulating the expression of the genes encoded in the same mRNAs that generate them. For example, the V. cholerae OppZ and CarZ sRNAs, which originate from the oppABCDF and carAB operons upon RNase E processing, respectively, base-pair with their own transcripts, leading to translation initiation inhibition and followed by Rho-dependent transcription termination (Hoyos et al., 2020). It is noteworthy that most of 3′UTR-derived sRNAs modulate the expression of proteins with functions related to the genes they originate from. Therefore, 3′UTRs could be considered as additional functional units complementing polycistronic operons. Among the several transcriptomic mapping analyses carried out so far, there are still numerous 3′UTR-derived sRNA candidates that need to be studied. Therefore, it is expected that the number and functions of these kind of post-transcriptional regulators will increase in the near future.

Table 1.

Relevant 3′UTR-derived sRNAs characterized in bacteria.

| Species | mRNA | sRNA | Targets | Relevant characteristics | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gram-negative bacteria | |||||

| Type I 3′UTR-derived sRNAs | |||||

| Escherichia coli | cutC | MicL | lpp | σE-dependent, involved in membrane stress | Guo et al., 2014 |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | PA4570 | RsmW | RsmA | Sponge RNA that sequesters the RsmA protein, modulating biofilm formation | Miller et al., 2016 |

| Salmonella | dapB | DapZ |

oppA dppA |

HilD-dependent, represses two ABC transporters | Chao et al., 2012 |

| Vibrio cholerae | vca0943 | MicX |

vc0972 vc0620 |

Processed by RNase E in a Hfq-dependent manner, regulates an outer membrane protein, and an ABC transporter | Davis and Waldor, 2007 |

| Type II 3′UTR-derived sRNAs | |||||

| Escherichia coli | malEFG | MalH |

ompC ompA MicA |

Hfq-dependent, promotes accumulation of maltose transporters during transition growth phase | Iosub et al., 2020 |

| sdhCDAB-sucABCD | SdhX |

ackA fdoG katG |

Coordinates the expression of the TCA cycle and the acetate metabolism | De Mets et al., 2019; Miyakoshi et al., 2019 | |

| Rhodobacter sphaeroides | RSP_0847 | SorX | potA | Inhibits a polyamine transporter to counteract oxidative stress | Peng et al., 2016 |

| Salmonella | cpxP | CpxQ |

agp fimAICDHF nhaB skp-lpxD ydjN |

Hfq-dependent, targets extracytoplasmic proteins to alleviate inner membrane stress | Chao and Vogel, 2016 |

| narK | NarS | nirC | Hfq-dependent, involved in nitrate respiration homeostasis | Wang et al., 2020 | |

| raiA | RaiZ | hupA | ProQ-dependent, represses translation of hupA mRNA | Smirnov et al., 2017 | |

| sdhCDAB-sucABCD | SdhX |

ackA fumB yfbV |

Coordinates the expression of the TCA cycle and the acetate metabolism | Miyakoshi et al., 2019 | |

| gltIJKL | SroC | GcvB | Sponge RNA, alleviates GcvB repression of amino acid transport, and metabolic genes | Miyakoshi et al., 2015a | |

| Vibrio cholerae | carAB | CarZ | carAB | It negatively autoregulates the operon from which it is processed | Hoyos et al., 2020 |

| fabB | FarS | fadE | Hfq-dependent, regulates fatty acid metabolism | Huber et al., 2020 | |

| oppABCDF | OppZ | oppABCDF | It negatively autoregulates the operon from which it is processed | Hoyos et al., 2020 | |

| Gram-positive bacteria | |||||

| Type I 3′UTR-derived sRNAs | |||||

| Lactococcus lactis | argR | ArgX | arcC1 | Regulates the arginine metabolism | van der Meulen et al., 2019 |

| Type II 3′UTR-derived sRNAs | |||||

| Staphylococcus aureus | mntABC | RsaC | sodA | Involved in the oxidative stress response and metal homeostasis | Lalaouna et al., 2019 |

| Streptomyces coelicolor | sodF | s-SodF | sodN | Inhibits SodN, regulates superoxide dismutases expression depending on nutrient availability | Kim et al., 2014 |

3′UTRs That Target Other mRNAs in Trans

In some cases, the whole mRNA molecule can act as a regulatory RNA by itself and modulate the expression of other mRNAs in trans. This is the case of RNAIII from S. aureus. Asides from cis-regulating the δ-hemolysin translation through a 5′UTR-3′UTR interaction, it modulates in trans several mRNA targets that encode surface proteins and virulence factors at the post-transcriptional level (Balaban and Novick, 1995; Bronesky et al., 2016). For instance, the binding of RNAIII to the spa, coa, sbi, and rot mRNAs impairs their translation and it often leads to RNase III processing (Huntzinger et al., 2005; Boisset et al., 2007; Chevalier et al., 2010; Chabelskaya et al., 2014). However, RNAIII regulation is not always in the form of repression. The mgrA and hla mRNAs are positively regulated after interacting with RNAIII through stabilization of the mRNA in the former (Gupta et al., 2015) and activation of translation in the latter (Morfeldt et al., 1995). Overall, the duality of RNAIII as a regulator resides in its ability to repress surface proteins while promoting the expression of secreted virulence factors (Bronesky et al., 2016; Raina et al., 2018). In L. monocytogenes, the 3′UTR of the hly mRNA (listeriolysin O) base pairs with the 5′UTR of the prsA2 mRNA (Ignatov et al., 2020). Both, listeriolysin O and PrsA2 are virulence factors necessary for L. monoctyogenes infection cycle (Alonzo and Freitag, 2010; Hamon et al., 2012). This mRNA-mRNA interaction prevents the degradation of the prsA2 mRNA by RNase J1. When mutations are introduced in the hly 3′UTR or prsA2 5′UTR, the interaction between them is abolished resulting in reduced pathogenicity (Ignatov et al., 2020).

Differential Evolution of 3′UTRs in Bacteria

The sequence of some 3′UTRs have been shown to be variable depending on the bacterial species. The dapB and sdh 3′UTRs, which produce the 3′UTR-derived sRNAs DapZ and SdhX, respectively, show nucleotide variations between different enterobacterial species, leading to functional variability (Chao et al., 2012; De Mets et al., 2019; Miyakoshi et al., 2019). For instance, SdhX represses different mRNA targets in E. coli and Salmonella through a slightly different seed sequence (Miyakoshi et al., 2019). In S. aureus, the icaR 3′UTR presents a sequence divergence when compared to other staphylococcal species (Ruiz de Los Mozos et al., 2013). In fact, the sequence downstream of icaR is completely different to its close relative, S. epidermidis. Although, the S. epidermidis icaR 3′UTR has a similar length to that of S. aureus (365 vs 391 nt, respectively), the UCCCC motif or an equivalent sequence to pair with the 5′UTR are lacking. Instead, the S. epidermidis IcaR 5′UTR is targeted by the IcaZ sRNA, which impairs the icaR mRNA translation. Interestingly, the IcaZ sRNA is encoded just downstream of the S. epidermidis icaR mRNA, indicating that not only the 3′UTRs are different but also the regions downstream of the transcriptional terminator (Lerch et al., 2019). Sequence variations found downstream of the icaR CDS could be explained by gene rearrangements that occurred when the icaRADBC operon was acquired by certain staphylococcal species (Menendez-Gil et al., 2020). Note that only 9 staphylococcal species encode the ica genes and that their genomic position varies from one another. In 4 of them the icaR gene appears to be replaced by other genes that encode DspB (hexosaminidase), a TetR-like regulator, or proteins of a two-component system that might be involved in controlling the PIA-PNAG exopolysaccharide production through different mechanisms. These gene rearrangements could have naturally led to the occurrence of different icaR mRNA chimeras among staphylococcal species and, therefore, explain the currently observed functional differences at the post-transcriptional level (Menendez-Gil et al., 2020). A recent genome-wide study carried out by our group revealed that variations on 3′UTR sequences were widespread. We found that most of the 3′UTRs from orthologous genes were not conserved among species of the genus Staphylococcus (Menendez-Gil et al., 2020). These 3′UTRs differed both in sequence and length. The mRNA sequence conservation was lost around the stop codon. When comparing close relative species, the nucleotide variations occurred through different processes, including gene rearrangements, local nucleotide changes and transposition of insertion sequences. Swapping the 3′UTR sequences produced changes in the mRNA and protein levels of conserved staphylococcal genes, suggesting the existence of different regulatory elements in each orthologous mRNA. Interestingly, this differential evolution applied to most of the mRNAs encoding orthologous proteins among species of Enterobacteriaceae family and Bacillus genus. Also, several previously described functional 3′UTRs, including E. coli acnB, Y. pestis hmsT, C. glutamicum aceA, and B. subtilis hbs, were not conserved among orthologous mRNAs of their close-relative species. This widespread 3′UTR variability might be responsible for creating different functional regulatory roles and, ultimately, bacterial diversity through the course of evolution, resembling the process of diversification of eukaryotic species (Menendez-Gil et al., 2020).

Perspectives

Historically bacterial 3′UTRs have been undervalued, probably because the real boundaries of the transcript 3′ ends were missed and/or the analyses that looked for functional non-coding RNAs were biased by parameters such as sequence conservation. However, the examples presented in this MiniReview show that 3′UTRs contain a wide repertoire of diverse regulatory elements and they constitute a key regulatory layer to be considered when studying post-transcriptional regulation in bacteria. It is clear that 3′UTRs are involved in the modulation of relevant biological processes such as metabolism, iron homeostasis, biofilm formation and virulence, among others. Although a lack of sequence conservation was often associated with a lack of function, the differential evolution found within 3′UTRs from close-relative bacteria should help changing our overall perception about them. Considering that eukaryotic 3′UTRs have been utilized by evolution to create alternative regulatory pathways and, hence, contribute to species diversification, a similar phenomenon might be envisioned for bacterial 3′UTRs. Although few examples support this theory so far (Chao et al., 2012; Ruiz de Los Mozos et al., 2013; Lerch et al., 2019; Miyakoshi et al., 2019; Menendez-Gil et al., 2020), it is expected that, by studying the vast numbers of the recently identified long 3′UTRs and their orthologs, we will finally understand the biological relevance of 3′UTR mediated-regulatory mechanisms.

Author Contributions

PM-G and AT-A contributed to the conception, contents, and writing of this manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Carlos J. Caballero for critical reading of this manuscript. We also acknowledge support of the publication fee by the CSIC Open Access Publication Support Initiative through its Unit of Information Resources for Research (URICI).

Footnotes

Funding. This work was supported by the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation program (Grant Agreement No. ERC-CoG-2014-646869) and the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation grant (PID2019-105216GB-I00).

References

- Alekhina O. M., Terenin I. M., Dmitriev S. E., Vassilenko K. S. (2020). Functional cyclization of eukaryotic mRNAs. Imt. J. Mol. Sci. 21, 1677. 10.3390/ijms21051677 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alonzo F., Freitag N. E. (2010). Listeria monocytogenes PrsA2 is required for virulence factor secretion and bacterial viability within the host cell cytosol. Infect. Immun. 78, 4944–4957. 10.1128/IAI.00532-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnvig K. B., Comas I., Thomson N. R., Houghton J., Boshoff H. I., Croucher N. J., et al. (2011). Sequence-based analysis uncovers an abundance of non-coding RNA in the total transcriptome of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. PLoS Pathog. 7, e1002342. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakheet T., Williams B. R. G., Khabar K. S. A. (2006). ARED 3.0: the large and diverse AU-rich transcriptome. Nucleic Acids Res. 34, D111–D114. 10.1093/nar/gkj052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balaban N., Novick R. P. (1995). Translation of RNAIII, the Staphylococcus aureus agr regulatory RNA molecule, can be activated by a 3'-end deletion. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 133, 155–161. 10.1016/0378-1097(95)00356-A [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balasubramanian D., Ohneck E. A., Chapman J., Weiss A., Kim M. K., Reyes-Robles T., et al. (2016). Staphylococcus aureus coordinates leukocidin expression and pathogenesis by sensing metabolic fluxes via RpiRc. mBio 7, e00818–16. 10.1128/mBio.00818-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benito Y., Kolb F. A., Romby P., Lina G., Etienne J., Vandenesch F. (2000). Probing the structure of RNAIII, the Staphylococcus aureus agr regulatory RNA, and identification of the RNA domain involved in repression of protein A expression. RNA 6, 668–679. 10.1017/S1355838200992550 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamin J.-A. M., Massé E. (2014). The iron-sensing aconitase B binds its own mRNA to prevent sRNA-induced mRNA cleavage. Nucleic Acids Res. 42, 10023–10036. 10.1093/nar/gku649 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkovits B. D., Mayr C. (2015). Alternative 3′ UTRs act as scaffolds to regulate membrane protein localization. Nature. 522, 363–367. 10.1038/nature14321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bidnenko V., Nicolas P., Grylak-Mielnicka A., Delumeau O., Auger S., Aucouturier A., et al. (2017). Termination factor Rho: from the control of pervasive transcription to cell fate determination in Bacillus subtilis. PLoS Genet. 13, e1006909. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1006909 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boisset S., Geissmann T., Huntzinger E., Fechter P., Bendridi N., Possedko M., et al. (2007). Staphylococcus aureus RNAIII coordinately represses the synthesis of virulence factors and the transcription regulator Rot by an antisense mechanism. Genes Dev. 21, 1353–1366. 10.1101/gad.423507 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bossi L., Schwartz A., Guillemardet B., Boudvillain M., Figueroa-Bossi N. (2012). A role for Rho-dependent polarity in gene regulation by a noncoding small RNA. Genes Dev. 26, 1864–1873. 10.1101/gad.195412.112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun F., Durand S., Condon C. (2017). Initiating ribosomes and a 5′/3′-UTR interaction control ribonuclease action to tightly couple B. subtilis hbs mRNA stability with translation. Nucleic Acids Res. 45, 11386–11400. 10.1093/nar/gkx793 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britton R. A., Wen T., Schaefer L., Pellegrini O., Uicker W. C., Mathy N., et al. (2007). Maturation of the 5' end of Bacillus subtilis 16S rRNA by the essential ribonuclease YkqC/RNase J1. Mol. Microbiol. 63, 127–138. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05499.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broeke-Smits N. J. P., Pronk T. E., Jongerius I., Bruning O., Wittink F. R., Breit T. M., et al. (2010). Operon structure of Staphylococcus aureus. Nucleic Acids Res. 38, 3263–3274. 10.1093/nar/gkq058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broglia L., Lécrivain A.-L., Renault T. T., Hahnke K., Ahmed-Begrich R., Le Rhun A., et al. (2020). An RNA-seq based comparative approach reveals the transcriptome-wide interplay between 3′-to-5′ exoRNases and RNase Y. Nat. Commun. 11, 1587–1512. 10.1038/s41467-020-15387-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronesky D., Desgranges E., Corvaglia A., Francois P., Caballero C. J., Prado L., et al. (2019). A multifaceted small RNA modulates gene expression upon glucose limitation in Staphylococcus aureus. EMBO J. 38, e99363 10.15252/embj.201899363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronesky D., Wu Z., Marzi S., Walter P., Geissmann T., Moreau K., et al. (2016). Staphylococcus aureus RNAIII and its regulon link quorum sensing, stress responses, metabolic adaptation, and regulation of virulence gene expression. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 70, 299–316. 10.1146/annurev-micro-102215-095708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cambray G., Guimaraes J. C., Mutalik V. K., Lam C., Mai Q.-A., Thimmaiah T., et al. (2013). Measurement and modeling of intrinsic transcription terminators. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, 5139–5148. 10.1093/nar/gkt163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chabelskaya S., Bordeau V., Felden B. (2014). Dual RNA regulatory control of a Staphylococcus aureus virulence factor. Nucleic Acids Res. 42, 4847–4858. 10.1093/nar/gku119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao Y., Li L., Girodat D., Förstner K. U., Said N., Corcoran C., et al. (2017). In vivo cleavage map illuminates the central role of RNase E in coding and non-coding RNA pathways. Mol. Cell 65, 39–51. 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.11.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao Y., Papenfort K., Reinhardt R., Sharma C. M., Vogel J. (2012). An atlas of Hfq-bound transcripts reveals 3′ UTRs as a genomic reservoir of regulatory small RNAs. EMBO J. 31, 4005–4019. 10.1038/emboj.2012.229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao Y., Vogel J. (2016). A 3' UTR-derived small RNA provides the regulatory noncoding arm of the inner membrane stress response. Mol. Cell 61, 352–363. 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.12.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J., Morita T., Gottesman S. (2019). Regulation of transcription termination of small RNAs and by small RNAs: Molecular mechanisms and biological functions. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 9, 201. 10.3389/fcimb.2019.00201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y.-J., Liu P., Nielsen A. A. K., Brophy J. A. N., Clancy K., Peterson T., et al. (2013). Characterization of 582 natural and synthetic terminators and quantification of their design constraints. Nat. Methods 10, 659–664. 10.1038/nmeth.2515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chevalier C., Boisset S., Romilly C., Masquida B., Fechter P., Geissmann T., et al. (2010). Staphylococcus aureus RNAIII binds to two distant regions of coa mRNA to arrest translation and promote mRNA degradation. PLoS Pathog. 6, e1000809. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000809 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciampi M. S. (2006). Rho-dependent terminators and transcription termination. Microbiology 152, 2515–2528. 10.1099/mic.0.28982-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dar D., Shamir M., Mellin J. R., Koutero M., Stern-Ginossar N., Cossart P., et al. (2016). Term-seq reveals abundant ribo-regulation of antibiotics resistance in bacteria. Science 352, aad9822. 10.1126/science.aad9822 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dar D., Sorek R. (2018a). Extensive reshaping of bacterial operons by programmed mRNA decay. PLoS Genet. 14, e1007354. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1007354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dar D., Sorek R. (2018b). High-resolution RNA 3'-ends mapping of bacterial Rho-dependent transcripts. Nucleic Acids Res. 46, 6797–6805. 10.1093/nar/gky274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis B. M., Waldor M. K. (2007). RNase E-dependent processing stabilizes MicX, a Vibrio cholerae sRNA. Mol. Microbiol. 65, 373–385. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05796.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Mets F., van Melderen L., Gottesman S. (2019). Regulation of acetate metabolism and coordination with the TCA cycle via a processed small RNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 116, 1043–1052. 10.1073/pnas.1815288116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutcher H. A., Raghavan R. (2018). Origin, evolution, and loss of bacterial small RNAs. Microbiol. Spectr. 6, 1–11. 10.1128/9781683670247.ch28 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Mouali Y., Balsalobre C. (2019). 3′untranslated regions: regulation at the end of the road. Curr. Genet. 65, 127–131. 10.1007/s00294-018-0877-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Mouali Y., Gaviria-Cantin T., Sánchez-Romero M. A., Gibert M., Westermann A. J., Vogel J., et al. (2018). CRP-cAMP mediates silencing of Salmonella virulence at the post-transcriptional level. PLoS Genet. 14, e1007401. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1007401 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Mauriño S. M., Rivero-Rodríguez F., Velázquez-Cruz A., Hernández-Vellisca M., Díaz-Quintana A., la Rosa D., et al. (2017). RNA binding protein regulation and cross-talk in the control of AU-rich mRNA fate. Front. Mol. Biosci. 4, 71. 10.3389/fmolb.2017.00071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gatewood M. L., Bralley P., Weil M. R., Jones G. H. (2012). RNA-Seq and RNA immunoprecipitation analyses of the transcriptome of Streptomyces coelicolor identify substrates for RNase III. J. Bacteriol. 194, 2228–2237. 10.1128/JB.06541-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaupp R., Wirf J., Wonnenberg B., Biegel T., Eisenbeis J., Graham J., et al. (2016). RpiRc is a pleiotropic effector of virulence determinant synthesis and attenuates pathogenicity in Staphylococcus aureus. Infect. Immun. 84, 2031–2041. 10.1128/IAI.00285-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georg J., Hess W. R. (2011). cis-Antisense RNA, another level of gene regulation in bacteria. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Res. 75, 286–300. 10.1128/MMBR.00032-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodson J. R., Klupt S., Zhang C., Straight P., Winkler W. C. (2017). LoaP is a broadly conserved antiterminator protein that regulates antibiotic gene clusters in Bacillus amyloliquefaciens. Nat. Microbiol. 2, 17003–17010. 10.1038/nmicrobiol.2017.3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodson J. R., Winkler W. C. (2018). Processive antitermination. Microbiol. Spectr. 6, 117–131. 10.1128/9781683670247.ch8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo M. S., Updegrove T. B., Gogol E. B., Shabalina S. A., Gross C. A., Storz G. (2014). MicL, a new σE-dependent sRNA, combats envelope stress by repressing synthesis of Lpp, the major outer membrane lipoprotein. Genes Dev. 28, 1620–1634. 10.1101/gad.243485.114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta R. K., Luong T. T., Lee C. Y. (2015). RNAIII of the Staphylococcus aureus agr system activates global regulator MgrA by stabilizing mRNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 112, 14036–14041. 10.1073/pnas.1509251112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halees A. S., El-Badrawi R., Khabar K. S. A. (2008). ARED organism: expansion of ARED reveals AU-rich element cluster variations between human and mouse. Nucleic Acids Res. 36, D137–D140. 10.1093/nar/gkm959 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halees A. S., Hitti E., Al-Saif M., Mahmoud L., Vlasova-St Louis I. A., Beisang D. J., et al. (2011). Global assessment of GU-rich regulatory content and function in the human transcriptome. RNA Biol. 8, 681–691. 10.4161/rna.8.4.16283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamon M. A., Ribet D., Stavru F., Cossart P. (2012). Listeriolysin O: the Swiss army knife of Listeria. Trends Microbiol. 20, 360–368. 10.1016/j.tim.2012.04.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernández J. A., Muro-Pastor A. M., Flores E., Bes M. T., Peleato M. L., Fillat M. F. (2006). Identification of a furA cis antisense RNA in the cyanobacterium Anabaena sp. PCC 7120. J. Mol. Biol. 355, 325–334. 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.10.079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmqvist E., Li L., Bischler T., Barquist L., Vogel J. (2018). Global maps of ProQ binding in vivo reveal target recognition via RNA structure and stability control at mRNA 3' ends. Mol. Cell 70, 971–982.e6. 10.1016/j.molcel.2018.04.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmqvist E., Vogel J. X. R. (2018). RNA-binding proteins in bacteria. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 16, 601–615. 10.1038/s41579-018-0049-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmqvist E., Wright P. R., Li L., Bischler T., Barquist L., Reinhardt R., et al. (2016). Global RNA recognition patterns of post-transcriptional regulators Hfq and CsrA revealed by UV crosslinking in vivo. EMBO J. 35, 991–1011. 10.15252/embj.201593360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoyos M., Huber M., Förstner K. U., Papenfort K. (2020). Gene autoregulation by 3' UTR-derived bacterial small RNAs. eLife 9, e58836. 10.7554/eLife.58836.sa2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang L., Deighan P., Jin J., Li Y., Cheung H. C., Lee E., et al. (2020). Tombusvirus p19 captures RNase III-cleaved double-stranded RNAs formed by overlapping sense and antisense transcripts in Escherichia coli. MBio 11, 1564. 10.1128/mBio.00485-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber M., Fröhlich K. S., Radmer J., Papenfort K. (2020). Switching fatty acid metabolism by an RNA-controlled feed forward loop. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 117, 8044–8054. 10.1073/pnas.1920753117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hui M. P., Foley P. L., Belasco J. G. (2014). Messenger RNA degradation in bacterial cells. Annu. Rev. Genet. 48, 537–559. 10.1146/annurev-genet-120213-092340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huntzinger E., Boisset S., Saveanu C., Benito Y., Geissmann T., Namane A., et al. (2005). Staphylococcus aureus RNAIII and the endoribonuclease III coordinately regulate spa gene expression. EMBO J. 24, 824–835. 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600572 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ignatov D., Vaitkevicius K., Durand S., Cahoon L., Sandberg S. S., Liu X., et al. (2020). An mRNA-mRNA interaction couples expression of a virulence factor and its chaperone in Listeria monocytogenes. Cell Rep. 30, 4027-4040.e7. 10.1016/j.celrep.2020.03.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iosub I. A., van Nues R. W., McKellar S. W., Nieken K. J., Marchioretto M., Sy B., et al. (2020). Hfq CLASH uncovers sRNA-target interaction networks linked to nutrient availability adaptation. Elife 9, 1–33. 10.7554/eLife.54655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson G. E., Lalanne J.-B., Peters M. L., Li G.-W. (2020). Functionally uncoupled transcription-translation in Bacillus subtilis. Nature 585, 124–128. 10.1038/s41586-020-2638-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawano M., Reynolds A. A., Miranda-Rios J., Storz G. (2005). Detection of 5′- and 3-′UTR-derived small RNAs and cis-encoded antisense RNAs in Escherichia coli. Nucleic Acids Res. 33, 1040–1050. 10.1093/nar/gki256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khabar K. S. A. (2010). Post-transcriptional control during chronic inflammation and cancer: a focus on AU-rich elements. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 67, 2937–2955. 10.1007/s00018-010-0383-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H. M., Shin J. H., Cho Y. B., Roe J. H. (2014). Inverse regulation of Fe- and Ni-containing SOD genes by a Fur family regulator Nur through small RNA processed from 3′UTR of the sodF mRNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 42, 2003–2014. 10.1093/nar/gkt1071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krol J., Loedige I., Filipowicz W. (2010). The widespread regulation of microRNA biogenesis, function and decay. Nat. Rev. Genet. 11, 597–610. 10.1038/nrg2843 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lalaouna D., Baude J., Wu Z., Tomasini A., Chicher J., Marzi S., et al. (2019). RsaC sRNA modulates the oxidative stress response of Staphylococcus aureus during manganese starvation. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, 9871–9887. 10.1093/nar/gkz728 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lasa I., Toledo-Arana A., Dobin A., Villanueva M., de los Mozos I. R., Vergara-Irigaray M., et al. (2011). Genome-wide antisense transcription drives mRNA processing in bacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 108, 20172–20177. 10.1073/pnas.1113521108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lasa I., Toledo-Arana A., Gingeras T. R. (2012). An effort to make sense of antisense transcription in bacteria. RNA Biol. 9, 1039–1044. 10.4161/rna.21167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerch M. F., Schoenfelder S. M. K., Marincola G., Wencker F. D. R., Eckart M., Förstner K. U., et al. (2019). A non-coding RNA from the intercellular adhesion (ica) locus of Staphylococcus epidermidis controls polysaccharide intercellular adhesion (PIA)-mediated biofilm formation. Mol. Microbiol. 111, 1571–1591. 10.1111/mmi.14238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lianoglou S., Garg V., Yang J. L., Leslie C. S., Mayr C. (2013). Ubiquitously transcribed genes use alternative polyadenylation to achieve tissue-specific expression. Genes Dev. 27, 2380–2396. 10.1101/gad.229328.113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lioliou E., Sharma C. M., Caldelari I., Helfer A. C., Fechter P., Vandenesch F., et al. (2012). Global regulatory functions of the Staphylococcus aureus endoribonuclease III in gene expression. PLoS Genet. 8, e1002782. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002782 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loh E., Righetti F., Eichner H., Twittenhoff C., Narberhaus F. (2018). RNA thermometers in bacterial pathogens. Microbiol. Spectr. 6, 1–16. 10.1128/9781683670247.ch4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- López-Garrido J., Puerta-Fernández E., Casadesús J. (2014). A eukaryotic-like 3' untranslated region in Salmonella enterica hilD mRNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 42, 5894–5906. 10.1093/nar/gku222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lybecker M., Zimmermann B., Bilusic I., Tukhtubaeva N., Schroeder R. (2014). The double-stranded transcriptome of Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 111, 3134–3139. 10.1073/pnas.1315974111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mäder U., Nicolas P., Depke M., Pane-Farre J., Débarbouill,é M., van der Kooi-Pol M. M., et al. (2016). Staphylococcus aureus transcriptome architecture: from laboratory to infection-mimicking conditions. PLoS Genet. 12, e1005962. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005962 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeda T., Wachi M. (2012). 3' untranslated region-dependent degradation of the aceA mRNA, encoding the glyoxylate cycle enzyme isocitrate lyase, by RNase E/G in Corynebacterium glutamicum. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 78, 8753–8761. 10.1128/AEM.02304-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayr C. (2016). Evolution and biological roles of alternative 3'UTRs. Trends Cell Biol. 26, 227–237. 10.1016/j.tcb.2015.10.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayr C. (2017). Regulation by 3′-untranslated regions. Annu. Rev. Genet 51, 171–194. 10.1146/annurev-genet-120116-024704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazumder B., Seshadri V., Fox P. L. (2003). Translational control by the 3′-UTR: the ends specify the means. Trends Biochem. Sci. 28, 91–98. 10.1016/S0968-0004(03)00002-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDowall K. J., Lin-Chaol S., Cohen S. N. (1994). A + U content rather than a particular nucleotide order determines the specificity of RNase E cleavage. J. Biol. Chem. 269, 10790–10796. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melamed S., Adams P. P., Zhang A., Zhang H., Storz G. (2019). RNA-RNA interactomes of ProQ and Hfq reveal overlapping and competing roles. Mol. Cell. 77, 411–425. 10.1016/j.molcel.2019.10.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melamed S., Peer A., Faigenbaum-Romm R., Gatt Y. E., Reiss N., Bar A., et al. (2016). Global mapping of small RNA-target interactions in bacteria. Mol. Cell 63, 884–897. 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.07.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menendez-Gil P., Caballero C. J., Catalan-Moreno A., Irurzun N., Barrio-Hernandez I., Caldelari I., et al. (2020). Differential evolution in 3'UTRs leads to specific gene expression in Staphylococcus. Nucleic Acids Res. 48, 2544–2563. 10.1093/nar/gkaa047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller C. L., Romero M., Karna S. L. R., Chen T., Heeb S., Leung K. P. (2016). RsmW, Pseudomonas aeruginosa small non-coding RsmA-binding RNA upregulated in biofilm versus planktonic growth conditions. BMC Microbiol. 16, 155. 10.1186/s12866-016-0771-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyakoshi M., Chao Y., Vogel J. (2015a). Cross talk between ABC transporter mRNAs via a target mRNA-derived sponge of the GcvB small RNA. EMBO J. 34, 1478–1492. 10.15252/embj.201490546 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyakoshi M., Chao Y., Vogel J. (2015b). Regulatory small RNAs from the 3' regions of bacterial mRNAs. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 24, 132–139. 10.1016/j.mib.2015.01.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyakoshi M., Matera G., Maki K., Sone Y., Vogel J. (2019). Functional expansion of a TCA cycle operon mRNA by a 3' end-derived small RNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, 2075–2088. 10.1093/nar/gky1243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moody M. J., Young R. A., Jones S. E., Elliot M. A. (2013). Comparative analysis of non-coding RNAs in the antibiotic-producing Streptomyces bacteria. BMC Genomics 14, 558. 10.1186/1471-2164-14-558 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morfeldt E., Taylor D., Gabain V., on A., Arvidson S. (1995). Activation of alpha-toxin translation in Staphylococcus aureus by the trans-encoded antisense RNA, RNAIII. EMBO J. 14, 4569–4577. 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb00136.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrissey J. A., Cockayne A., Brummell K., Williams P. (2004). The staphylococcal ferritins are differentially regulated in response to iron and manganese and via PerR and Fur. Infect. Immun. 72, 972–979. 10.1128/IAI.72.2.972-979.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicolas P., Mäder U., Dervyn E., Rochat T., Leduc A., Pigeonneau N., et al. (2012). Condition-dependent transcriptome reveals high-level regulatory architecture in Bacillus subtilis. Science 335, 1103–1106. 10.1126/science.1206848 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavlova N., Kaloudas D., Penchovsky R. (2019). Riboswitch distribution, structure, and function in bacteria. Gene 708, 38–48. 10.1016/j.gene.2019.05.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng T., Berghoff B. A., Oh J.-I., Weber L., Schirmer J., Schwarz J., et al. (2016). Regulation of a polyamine transporter by the conserved 3′UTR-derived sRNA SorX confers resistance to singlet oxygen and organic hydroperoxides in Rhodobacter sphaeroides. RNA Biol. 13, 988–999. 10.1080/15476286.2016.1212152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pesole G., Liuni S., Grillo G., Licciulli F., Mignone F., Gissi C., et al. (2002). UTRdb and UTRsite: specialized databases of sequences and functional elements of 5′ and 3′ untranslated regions of eukaryotic mRNAs. Update 2002. Nucleic Acids Res. 30, 335–340. 10.1093/nar/30.1.335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters J. M., Vangeloff A. D., Landick R. (2011). Bacterial transcription terminators: the RNA 3′-end chronicles. J. Mol. Biol. 412, 793–813. 10.1016/j.jmb.2011.03.036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phadtare S., Inouye M., Severinov K. (2002). The nucleic acid melting activity of Escherichia coli CspE is critical for transcription antitermination and cold acclimation of cells. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 7239–7245. 10.1074/jbc.M111496200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potts A. H., Vakulskas C. A., Pannuri A., Yakhnin H., Babitzke P., Romeo T. (2017). Global role of the bacterial post-transcriptional regulator CsrA revealed by integrated transcriptomics. Nat. Commun. 8, 1596. 10.1038/s41467-017-01613-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raina M., King A., Bianco C., Vanderpool C. K. (2018). Dual-function RNAs. Microbiol Spectr. 6, 1–15. 10.1128/9781683670247.ch27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen S., Nielsen H. B., Jarmer H. (2009). The transcriptionally active regions in the genome of Bacillus subtilis. Mol. Microbiol. 73, 1043–1057. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06830.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz de Los Mozos I., Vergara-Irigaray M., Segura V., Villanueva M., Bitarte N., Saramago M., et al. (2013). Base pairing interaction between 5′- and 3-′UTRs controls icaR mRNA translation in Staphylococcus aureus. PLoS Genet. 9, e1004001. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sáenz-Lahoya S., Bitarte N., Garcia B., Burgui S., Vergara-Irigaray M., Valle J., et al. (2019). Noncontiguous operon is a genetic organization for coordinating bacterial gene expression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 116, 1733–1738. 10.1073/pnas.1812746116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saliminejad K., Khorram Khorshid H. R., Soleymani Fard S., Ghaffari S. H. (2019). An overview of microRNAs: biology, functions, therapeutics, and analysis methods. J. Cell. Physiol. 234, 5451–5465. 10.1002/jcp.27486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook J., Russell D. W. (2006). Mapping RNA with nuclease s1. CSH Protoc. 2006, pdb.prot4053. 10.1101/pdb.prot4053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serganov A., Nudler E. (2013). A decade of riboswitches. Cell 152, 17–24. 10.1016/j.cell.2012.12.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sesto N., Wurtzel O., Archambaud C., Sorek R., Cossart P. (2012). The excludon: a new concept in bacterial antisense RNA-mediated gene regulation. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 11, 75–82. 10.1038/nrmicro2934 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma C. M., Hoffmann S., Darfeuille F., Reignier J., Findeiss S., Sittka A., et al. (2010). The primary transcriptome of the major human pathogen Helicobacter pylori. Nature 464, 250–255. 10.1038/nature08756 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smirnov A., Wang C., Drewry L. L., Vogel J. (2017). Molecular mechanism of mRNA repression in trans by a ProQ-dependent small RNA. EMBO J. 36, 1029–1045. 10.15252/embj.201696127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stazic D., Voss B. (2016). The complexity of bacterial transcriptomes. J. Biotechnol. 232, 69–78. 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2015.09.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toledo-Arana A., Dussurget O., Nikitas G., Sesto N., Guet-Revillet H., Balestrino D., et al. (2009). The Listeria transcriptional landscape from saprophytism to virulence. Nature 459, 950–956. 10.1038/nature08080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toledo-Arana A., Lasa I. (2020). Advances in bacterial transcriptome understanding: from overlapping transcription to the excludon concept. Mol. Microbiol. 113, 593–602. 10.1111/mmi.14456 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tushev G., Glock C., Heumüller M., Biever A., Jovanovic M., Schuman E. M. (2018). Alternative 3′ UTRs modify the localization, regulatory potential, stability, and plasticity of mRNAs in neuronal compartments. Neuron 98, 495–511.e6. 10.1016/j.neuron.2018.03.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Assche E., Van Puyvelde S., Vanderleyden J., Steenackers H. P. (2015). RNA-binding proteins involved in post-transcriptional regulation in bacteria. Front. Microbiol. 6, 141. 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Meulen S. B., Hesseling-Meinders A., de Jong A., Kok J. (2019). The protein regulator ArgR and the sRNA derived from the 3'-UTR region of its gene, ArgX, both regulate the arginine deiminase pathway in Lactococcus lactis. PLoS One 14, e0218508. 10.1371/journal.pone.0218508 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vlasova I. A., Tahoe N. M., Fan D., Larsson O., Rattenbacher B., Sternjohn J. R., et al. (2008). Conserved GU-rich elements mediate mRNA decay by binding to CUG-binding protein 1. Mol. Cell 29, 263–270. 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.11.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Roretz C., di Marco S., Mazroui R., Gallouzi I.-E. (2011). Turnover of AU-rich-containing mRNAs during stress: a matter of survival. WIREs RNA 2, 336–347. 10.1002/wrna.55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner E. G. H., Romby P. (2015). Small RNAs in bacteria and archaea: who they are, what they do, and how they do it. Adv. Genet. 90, 133–208. 10.1016/bs.adgen.2015.05.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C., Chao Y., Matera G., Gao Q., Vogel J. (2020). The conserved 3' UTR-derived small RNA NarS mediates mRNA crossregulation during nitrate respiration. Nucleic Acids Res. 48, 2126–2143. 10.1093/nar/gkz1168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X., Ji S. C., Jeon H. J., Lee Y., Lim H. M. (2015). Two-level inhibition of galK expression by Spot 42: Degradation of mRNA mK2 and enhanced transcription termination before the galK gene. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 112, 7581–7586. 10.1073/pnas.1424683112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells S. E., Hillner P. E., Vale R. D., Sachs A. B. (1998). Circularization of mRNA by eukaryotic translation initiation factors. Mol. Cell 2, 135–140. 10.1016/S1097-2765(00)80122-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodson S. A., Panja S., Santiago-Frangos A. (2018). Proteins that chaperone RNA regulation. Microbiol. Spectr. 6, 1–13. 10.1128/9781683670247.ch22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao J.-P., Zhu H., Guo X.-P., Sun Y.-C. (2018). AU-rich long 3' untranslated region regulates gene expression in bacteria. Front. Microbiol. 9, 3080. 10.3389/fmicb.2018.03080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu H., Mao X.-J., Guo X.-P., Sun Y.-C. (2015). The hmsT 3′ untranslated region mediates c-di-GMP metabolism and biofilm formation in Yersinia pestis. Mol. Microbiol. 99, 1167–1178. 10.1111/mmi.13301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Y., Nandakumar R., Sadykov M. R., Madayiputhiya N., Luong T. T., Gaupp R., et al. (2011). RpiR homologues may link Staphylococcus aureus RNAIII synthesis and pentose phosphate pathway regulation. J. Bacteriol. 193, 6187–6196. 10.1128/JB.05930-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zühlke D., Dörries K., Bernhardt J., Maaß S., Muntel J., Liebscher V., et al. (2016). Costs of life-Dynamics of the protein inventory of Staphylococcus aureus during anaerobiosis. Sci Rep. 6, 28172. 10.1038/srep28172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]