Abstract

Transparent wood (TW)-based composites are of significant interest for smart window applications. In this research, we demonstrate a facile dual-stimuli-responsive chromic TW where optical properties are reversibly controlled in response to changes in temperature and UV-radiation. For this functionality, bleached wood was impregnated with solvent-free thiol and ene monomers containing chromic components, consisting of a mixture of thermo- and photoresponsive chromophores, and was then UV-polymerized. Independent optical properties of individual chromic components were retained in the compositional mixture. This allowed to enhance the absolute optical transmission to 4 times above the phase change temperature. At the same time, the transmission at 550 nm could be reduced 11−77%, on exposure to UV by changing the concentration of chromic components. Chromic components were localized inside the lumen of the wood structure, and durable reversible optical properties were demonstrated by multiple cycling testing. In addition, the chromic TW composites showed reversible energy absorption capabilities for heat storage applications and demonstrated an enhancement of 64% in the tensile modulus as compared to a native thiol–ene polymer. This study elucidates the polymerization process and effect of chromic components distribution and composition on the material’s performance and perspectives toward the development of smart photoresponsive windows with energy storage capabilities.

Keywords: cellulose composites, dual chromism, temperature responsive, photochromic, heat storage, optical transmittance

Introduction

Wood is a renewable natural resource and interesting substrate for implementing in advanced materials due to its hierarchal porous structure from nano- to microscale, high mechanical strength, and the presence of surface functional groups suitable for altering the chemistry or imbibing functional moieties.1−4 Transparent wood (TW) has recently emerged as a biocomposite material for applications involving high light transmittance with pliable optical characteristics.5,6 Wood is made transparent by removing light-absorbing chromophores and filling the voids with a polymer of refractive index close to that of the wood substrate.7−11 Although transparent wood was initially developed for the analysis of wood anatomy,12 it is now considered as wood-based composite for advanced functional (and simultaneously load-bearing) applications, such as white-light-emitting diodes,13,14 solar cells,15,16 and luminescent17,18 and heat shielding19,20 applications in panels and windows. Smart electrodes for electrochromic properties of reversible control of optical properties on application of applied voltage are extending usefulness in various fields, especially for fabricating solar cells.21−28 Electrochromic TW was fabricated by coating poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene):poly(styrenesulfonate) (PEDOT:PSS), which can switch to a coloration efficiency of 590 cm2 C–1.29 TW with low thermal conductivity, low specific density, enhanced toughness, and shatterproof features can be considered as good candidate for window-like structures instead of brittle glass.30,31

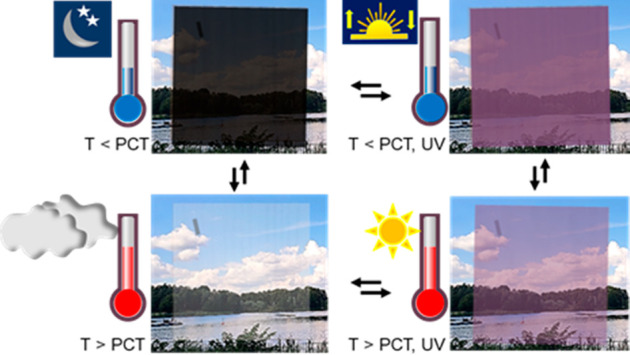

One way of advancing existing research on TW for window applications would be to control optical properties in response to environmental (climatic) conditions. The proposition was to develop a temperature- and UV-responsive new type of window model from TW material, which can remain dark and opaque below a certain phase change temperature (PCT), for instance, representing night conditions, thus reducing see-through properties to maintain privacy. This can be achieved by inclusion of thermochromic (TC) components. At the same time, such a window concept is enabled to sense daylight conditions which can allow the passage of sunlight inside building by enhancing the light transmission. In addition to the thermochromic effect, under hot weather conditions or mid-day time, when too much sunlight is undesirable, a smart TW window would respond by changing color to a lighter hue (to allow partial light transmittance) instead of becoming completely dark. The change in color/transmittance is achieved by inclusion of photochromic (PC) components which are receptive to the UV spectral part of sunlight. This investigation, thus, aims at developing of a novel thermo- and photoresponsive TW, which can sense and control color and light transmission at different periods during the day or at different ambient conditions.

There exist previous studies on TW with photochromic additives only,32,25 but our goal was to combine thermochromic and photochromic components, lower the haze, and develop a basic understanding of how the fairly complex biocomposite composition influences optical properties of the material. There are also previous studies on thermoresponsive TW,30,33 but the present investigation simultaneously targets color change, improved transmittance, reduced haze, and, again, to combine thermo- and photoresponsive performance. As a host polymer, the thiol–ene is used in the present investigation to reduce wood–polymer debond cracks resulting from cure shrinkage and corresponding light scattering. Thiol–enes show gelation late, during polymerization at high degree of reaction, which means that little cure shrinkage occurs in the solid state. Reported volume shrinkage for thiol–ene and PMMA-based polymer systems are 4.1%34 and 20%,35 respectively. In addition, the thiol and ene monomers do not require any organic solvent or prepolymerization of monomers which is used in many reported studies.36 UV-curing is a processing advantage of the present thiol–ene, which reduces the energy required to process the biocomposite.

Fundamentals of novel TW biocomposites processing, as well as thermo- and photochromic component composition effects on optical properties, were investigated. The main idea was to gain detailed control of stimuli-responsive optical properties based on exposure to UV-radiation and temperature. Thermo- and photochromic microcapsules were used to avoid potential self- and cross-aggregation and photobleaching degradation of chromophores, which is a known problem for most of the dyes.37,38 Hence, establishing the fabrication technology of dual chromic components and understanding their effects on the composite properties will pave a path forward toward novel multifunctional TW composite structures.

Experimental Section

Materials and Chemicals

Balsa wood with density of 170–200 kg m–3 was procured from Material AB (Sweden). Acetone, ethanol absolute (99%), and sodium hydroxide were supplied from VWR. Hydrogen peroxide (30%), UV initiator 1-hydroxycyclohexyl phenyl ketone, pentaerythritoltetrakis(3-mercaptopropionate) (PETMP, tetrafunctional thiol monomer), sodium acetate, sodium silicate, and 1,3,5-triallyl-1,3,5-triazine-2,4,6(1H,3H,5H)-trione (TATATO, trifunctional ene monomer) were supplied from Sigma-Aldrich. Acetic acid (Honeywell), diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid (DTPA, Acros Organics), magnesium sulfate (Scharlau), and sodium chlorite (40%, Alfa Aesar) were procured and used as received. Thermochromic (TC) and photochromic pigments (PC) in the form of microcapsules were purchased from SFXC dyes (United Kingdom) with average capsule diameters of 5 ± 2 and 6 ± 3 μm, respectively, as measured from SEM (Figure S1). The thermochromic pigment was based on leuco vat dye with a reversible PCT of 31 °C, where the pigment changed from black to colorless. The photochromic pigment was made from a mixture of potassium nitrate (50–55%), silica (18–23%), sodium nitrate (10–15%), and azobenzene(butylmethoxydibenzoylmethane) (7–22%) and changes from a white to purple hue on exposure to sunlight.

Lignin Modification of Wood (Bleaching Process)

The 15 ×15 × 1.1 (l × b × h) mm3 samples were weighed and treated with an aqueous hydrogen peroxide-based bleaching solution at 70 °C. The bleaching solution consisted of sodium silicate (3.0 wt %), sodium hydroxide (3.0 wt %), magnesium sulfate (0.1 wt %), DTPA (0.1 wt %), and hydrogen peroxide (4.0 wt %) in deionized (DI) water as per the process reported elsewhere.39 Samples were treated until they turned visibly white.

Fabrication of Transparent Wood

Bleached wood samples were washed with deionized water and were solvent exchanged with ethanol and acetone. These wood templates were then infiltrated with stoichiometric mixtures of thiol and allyl functionalized monomers of PETMP and TATATO containing the UV-initiator 1-hydroxycyclohexyl phenyl ketone (0.5 wt %) along with measured quantities of thermochromic or/and photochromic components as detailed in Table 1 under vacuum for 24 h. The acetone present in the samples evaporated during the vacuum infiltration process. Samples were additionally kept at 50 °C for 30 min to remove residual acetone, monitored by weight loss assessment. Monomer infiltrated samples were then sandwiched between two glass slides and cured for 4 min by illumination from four 9 W 365 nm UV-lamps: two on opposite sides of and two above the sample to ensure uniform curing. The mass fractions of wood and polymer in the resultant composites were determined from the density difference between bleached and the cured TW samples after drying the bleached samples at 105 ± 3 °C for 24 h.

Table 1. Formulation Details and Sample Codes for Various TW Composites.

| sample code | chromic contenta (wt %) | thermochromic component (TC) (%) | photochromic component (PC) (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thiol–ene TW | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| T1000.1 | 0.1 | 100 | 0 |

| T1000.5 | 0.5 | 100 | 0 |

| T1001 | 1 | 100 | 0 |

| T1003 | 3 | 100 | 0 |

| T1005 | 5 | 100 | 0 |

| T30P700.1 | 0.1 | 30 | 70 |

| T30P700.5 | 0.5 | 30 | 70 |

| T30P701 | 1 | 30 | 70 |

| T30P703 | 3 | 30 | 70 |

| T30P705 | 5 | 30 | 70 |

| T50P500.1 | 0.1 | 50 | 50 |

| T50P500.5 | 0.5 | 50 | 50 |

| T50P501 | 1 | 50 | 50 |

| T50P503 | 3 | 50 | 50 |

| T50P505 | 5 | 50 | 50 |

| T70P300.1 | 0.1 | 70 | 30 |

| T70P300.5 | 0.5 | 70 | 30 |

| T70P301 | 1 | 70 | 30 |

| T70P303 | 3 | 70 | 30 |

| T70P305 | 5 | 70 | 30 |

| P1000.1 | 0.1 | 0 | 100 |

| P1000.5 | 0.5 | 0 | 100 |

| P1001 | 1 | 0 | 100 |

| P1003 | 3 | 0 | 100 |

| P1005 | 5 | 0 | 100 |

Weight percent on the basis of monomer content.

Characterization

The morphology of the TW composites and the interfacial polymer–wood bonding was analyzed by using field-emission scanning electron microscopy (FE-SEM, Hitachi S-4800) operating at accelerating voltage of 1.0 kV and a working distance of 9.8 mm. Samples were cryo-fractured in liquid nitrogen before analyzing their cross sections.

Differential scanning microscopy was conducted on a TA 2920 modulated DSC. Samples were ramped from −50 to 100 °C, cooled to −50 °C, and again reheated to 100 °C at 10 °C min–1 under a nitrogen environment. The enthalpy of melting from the second heating cycle was analyzed for comparison of thermal energy absorption during the transition from the black to colorless state.

Raman spectra were measured on the freeze-fractured cross sections from TW samples by using confocal Raman microscopy (Jobin Yvon HR800 UV, Horiba) together with a light source from a 514 nm laser (Stellar-Pro, Modu-laser) and a mechanized stage. Spectra were averaged from 10 scans and analyzed for comparison.

Tensile tests were performed by using an Instron 5944 (USA) instrument equipped with a 500 N load cell, with sample dimensions of 50 × 5 × 1 mm3. The tests were performed with a 10% min–1 strain rate and gauge length of 25 mm. Samples were preconditioned for 24 h and tested in a room at a temperature of 22 ± 1 °C with 50 ± 2% relative humidity.

Optical measurements were performed by using an integrating sphere in the visible and NIR wavelength region (400–1000 nm) according to ASTM D1003 “Standard Method for Haze and Luminous Transmittance of Transparent Plastics”40 by using a quartz tungsten halogen light source (model 66181 from Oriel Instruments) as reported earlier.41 The sample was placed in front of an input port of the integrating sphere, illuminated with quartz tungsten halogen light source. The output light was collected through an optical fiber connected to an integrating sphere. Each sample was measured three times, and the results were statistically averaged. Samples were exposed to a hot air gun aimed to heat the sample uniformly from all sides and were equilibrated by heating for 1 min to achieve a surface temperature of 35 ± 2 °C. Above the PCT, the transmission curve stabilized, and no further changes were observed by increasing the temperature further. For transmission and haze measurement under UV, samples were illuminated with a UV torch operating at 360 nm with 3 mW power. Samples showed a response time of 4 ± 1 s for changing to purple on exposure to UV (when illuminated with a UV torch at 360 nm with 3 mW power) and a response time of 6 ± 1 s to return to their native hue after removal from the UV exposure.

Results and Discussion

Fabrication and Characterization of TW Composites

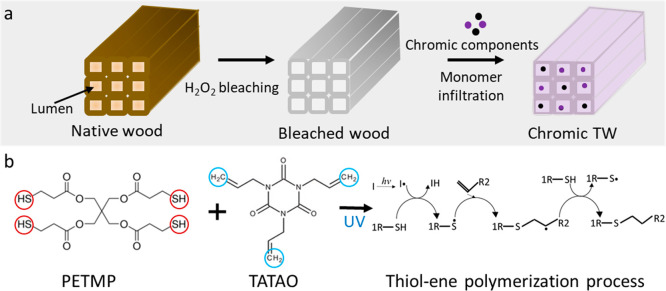

Chromic transparent wood composites (TW) were made by using a two-step process as shown in Figure 1a. In the first step, hydrogen peroxide bleaching was performed to remove the lignin chromophore groups. In the second step, the bleached wood sample was impregnated with a mixture of thermo- and photochromic components as well as thiol and ene monomers along with UV initiator. The sample was then polymerized under UV-light, and free radical polymerization mechanism between thiol and ene monomers is shown in Figure 1b. Note that the resulting polymer matrix impregnated in the bleached wood substrate was a chemically cross-linked thermoset. The resulting mass of polymer in the thiol–ene TW composites was 89 ± 2%.

Figure 1.

(a) Fabrication steps for chromic TW. (b) Schematic sketch for representation of the polymerization process.

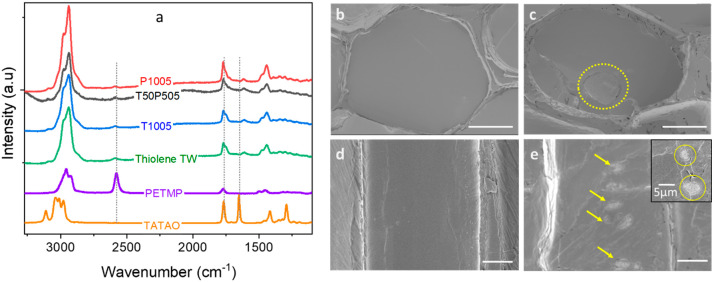

Raman analysis of the chromic TW composites was carried to quantify the degree of cure in the presence of chromic components. The characteristic monomer peaks were identified and compared to the control TW composite containing no externally added chromic components (Figure 2a). The ene monomer (TATAO) was characterized by allyl stretching (3095 cm–1) and allyl bending (1650 cm–1), and the thiol monomer was characterized by ketone stretching at (1765 cm–1). The weak peak at 1600 cm–1, corresponding to ring deformation mode, reveals some retainment of lignin in the bleached wood substrate. The degree of polymerization for the thiol and ene monomers was obtained by comparing integrals of peaks corresponding to thiol stretching (2575 cm–1) and allyl bending (1650 cm–1) normalized against ketone stretching (1765 cm–1) and was calculated to be 94 ± 3% and 99 ± 1%, respectively, in the lumen of the thiol–ene TW without any chromic component. The range of these values remained unaltered in the presence of chromic components. Absence of significant shift in characteristic peak position or variation in peak intensity in the chromic TW as compared to the control thiol–ene TW indicated that the presence of chromic components do not affect the polymerization process. Cryo-fractured cross sections and longitudinal sections of the samples were observed under SEM, shown in Figure 2b–d. As can be observed, polymer infiltration was successful in the lumen (empty center of wood cell) of the bleached balsa. The presence of TC and PC components was observed inside the lumen of a representative sample T50P501, as shown in Figures 2c and 2e, respectively. While the PC component stands out in contrast in the SEM image, the TC needs careful observation as it has low contrast difference compared to the polymer matrix. The dimensions of the components are in correspondence to the original structures (Figure S1). We conclude here that chromic components were successfully infiltrated along with the monomers and were located in the lumen space of the wood template without observable debond gaps between wood and polymer matrix. There was no aggregation of chromic components because microcapsules were spatially surrounded by the polymer matrix system.

Figure 2.

(a) Raman analysis of thiol–ene monomers and chromic TW composites. The gray lines correspond to thiol stretching (2575 cm–1), ketone stretching (1765 cm–1), and allyl bending (1650 cm–1). SEM of cross sections of (b) thiol–ene TW and (c) T50P505. Longitudinal sections of (d) thiol–ene TW and (e) T50P505. The spheres and arrows indicate the presence of chromic components in the system. The inset in (e) indicates an enlarged image of the chromic components. White bars in the pictures indicate a scale of 10 μm, unless otherwise specified.

Optical Properties and Materials Design

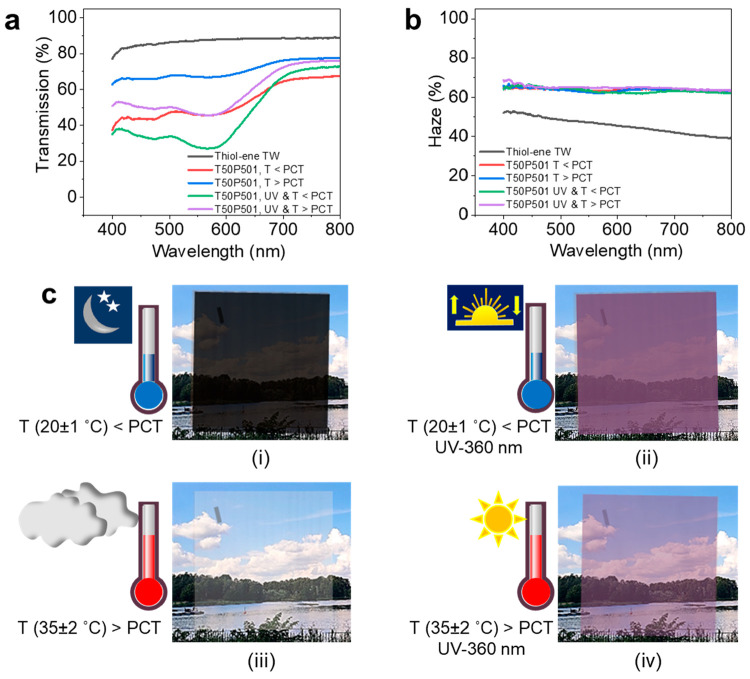

TW from the thiol–ene monomer sample (1.1 mm thick) without any chromic components showed a transmission of 87 ± 2% and haze of 47 ± 2% at 550 nm, as shown in Figure 3a,b. TW containing 1 wt % of black reversible TC (T1001), with respect to the polymer content, was analyzed for transmission below and above the PCT. The transmission value of T1001 at 550 nm increased by 146% (from 26 ± 1% to 64 ± 2%, absolute transmission) above the PCT of 31 °C (Figure S2a,b). Samples showed a transition time of 1–2 s to return from colorless to native black state when the surface temperature dropped below the PCT. Transmission values at 550 nm of TW samples with lowest (0.01 wt %, T1000.1) and highest (5 wt %, T1005) content of TC increased by 13% (from 76 ± 2 to 86 ± 1%, absolute transmission) and 300% (from 10 ± 2% to 40 ± 3%, absolute transmission), respectively, above the PCT. Variation in the enhancement of transmission above PCT is found to be proportional to the TC content. This can allow flexible design of TW with desired thermoresponsive optical properties, by judiciously altering the TC concentration. The realized here lack of TC agglomeration is central for such a linear performance.

Figure 3.

(a) Transmission and (b) haze graphs of a representative sample T50P501 on exposure to various conditions of temperature and/or UV mimicking external climatic conditions. (c) Images demonstrating visual change in transmission and color: (i) below PCT, 20 ± 1 °C; (ii) UV exposure at 360 nm, below PCT of 20 ± 1 °C; (iii) above PCT, 35 ± 2 °C; and (iv) UV exposure at 360 nm, above PCT of 35 ± 2 °C.

On exposure to UV (illuminated with a UV torch operating at 360 nm with 3 mW power), the transmission at 550 nm was reduced by 58% (from 66 ± 4% to 28 ± 3%, absolute transmittance) in samples with 1 wt % PC (P1001) with respect to the pristine polymer phase, as shown in Figure S2q,s. Samples showed a response time of 4 ± 1 s for changing to purple on exposure to UV and a response time of 6 ± 1 s to return to their native hue after removal from UV exposure. The reduction in transmission at 550 nm on exposure to UV can be varied from 11% (from 84 ± 2% to 74 ± 2%, absolute transmittance) to 77% (from 44 ± 2% to 10 ± 3%, absolute transmittance) by changing the PC in the samples from 0.1 wt % (P1000.1) to 5 (P1005) wt %, respectively, on the basis of the polymer content, as represented in Table S1. Thus, similarly to TC performance, TW can be designed to specific UV-responsive optical properties by simply altering the PC content.

For the final goal of this study TC and PC counterparts were combined to fabricate dual-stimuli-responsive TW composites. The transmission of a representative sample T50P501 (containing equal mass ratios of TC and PC) below and above PCT and UV exposure below and above PCT are shown in Figure 3a and Table S1. The transmission at 550 nm increased to 48% (from 46 ± 1% to 68 ± 3%, absolute transmission) above PCT and under UV exposure reduced to 41% (from 46 ± 1% to 27 ± 2%, absolute transmittance) below the phase change point in this composition. T50P501 visibly illustrates noticeable color change effects at varying conditions of temperature and UV (Figure 3c), a demonstration to mimic external environment conditions. The material clearly demonstrates its potential for fabricating dual-stimuli-responsive smart windows.

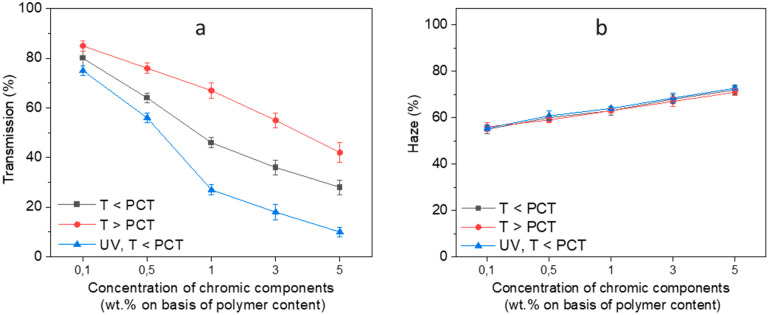

To study the influence of compositional effect (TC and PC) on optical properties of resultant TW, the ratio of TC/PC was varied as 30/70, 50/50, and 70/30 percentage proportion, with a constant of 1 wt % concentration of chromic component. Transmission values at 550 nm are shown in Figure 4a, Figure S2e–p, and Table S1. The higher the TC content, the higher is the influence on transmission percent above PCT. Similarly, the higher the content of PC, the greater is the absorption of UV spectral part. To validate this impact in more details, the concentration of the chromic component was then increased from 0.1 to 5 wt % with respect to polymer content. It is evident from the transmission data that higher chromic component content provides stronger response on the optical properties on exposure to temperature or UV. The resultant TW properties are governed by the chromic component content and component properties. These properties are retained in the well-dispersed compositional mixture and unaffected by the process of polymerization. The optical response can thus be controlled by varying the ratio and content of individual chromic components in a wide range of concentrations.

Figure 4.

(a) Transmission and (b) haze values at 550 nm of T50P50 TW composites containing equal proportions of TC and PC components with varying concentration of chromic components above and below PCT and on exposure to UV, respectively.

Haze is an important characteristic of a potential material for building envelopes. It is defined as a fraction of transmitted light deviating more than 1.5° from the ballistic photon direction, that is, scattered light carrying no information. The haze of the TW composites was measured individually below and above PCT in the absence or presence of UV illumination, as shown in Figure 4b and Table S1. Haze values at lowest chromic component concentration (0.1 wt %) containing either TC or PC were close to the haze of thiol–ene TW, 47 ± 2% at 550 nm. The haze values slightly increased with higher chromic component content, and the trend was the same for samples containing either TC, PC, or both. Microscopically, haze depends on the refractive index mismatch between polymer and wood substrate and on scattering defects such as voids or interfacial gaps between the polymer and the wood tissue in the system.42 For a given system, the refractive index for the polymer (1.56) and wood (RI = 1.53, 1.53, and 1.61 for cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin, respectively) is fixed, whereas the number of scattering interfaces increases by increasing the content of chromic component.43 Therefore, the haze values slightly increase with increased content of microcapsules in the system. As the number of scattering interfaces remain the same, no noticeable change in the haze values was observed for a given sample at different experimental conditions of temperature and UV or a combination of both.

Previous studies on photochromic TW have reported very high haze values of 95% (0.2 mm thick basswood)32 and 99% (2 mm balsa, density not specified) with inclusion of 0.05 and 1.5 wt % of photochromic component, respectively.44 Because wood density and polymer content are not reported, it is difficult to compare the haze values with our studies. A 47–53% lower haze (65 ± 2% at 550 nm, 1.1 mm balsa with density 170–200 kg m–3) was achieved in P1003 with more than twice the content of PC (3 wt %) compared to previous reports. This is possibly due to lower cure shrinkage and less interface debond gaps in wood–thiol–ene compared to wood–PMMA composites.43 A higher content of chromic components not only increases the optical effects of transmission and absorbance but also increases the haze values in the composite. The trade-off between enhanced chromic properties and haze should be estimated depending on particular applications. In this study, T50P501 containing two chromic components showed adequate stimuli-responsive change in chromic properties, but with significantly lower haze values at higher content of chromic components compared to previous work.32

Durability Studies

Sample T50P50 containing both TC and PC was submerged in water and was placed in oven at 40 °C for 14 days and then exposed to four 9 W 365 nm UV lamps for 6 h. No noticeable change (<1%) was observed (not shown) in the transmission values above PCT or on exposure to UV compared to the native control samples. The haze was 63 ± 2% in T50P501, and there was no observable change in haze values before and after exposure, indicating that the scattering interfaces are not changed. This substudy indicates that the TC and PC components demonstrate durable optical properties and are resistant to leaching as they are located inside the lumen of the wood surrounded by the thiol–ene polymer matrix.

Reversible Energy Absorption Capabilities of Chromic TW Composites

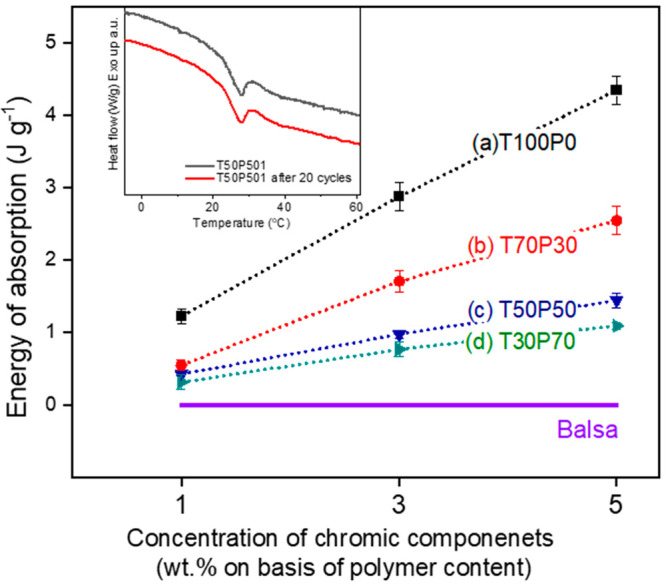

The presence of the TC component leads to energy absorption, which is an important characteristic in thermal energy storage applications for smart windows. The thermal storage cycles involve absorption and release of energy at 31 °C, the PCT for the TC component. The heating and cooling cycles of the TW composites with varying TC components and their enthalpy of fusion are presented in Figure S3. Native balsa and thiol–ene TW composite without any chromic component obviously do not show any enthalpy of fusion. TC composites show a fusion temperature at 31 °C and an enthalpy of fusion of 124 J g–1.

A peak melting temperature of 31 °C, the characteristic phase reversal temperature of the TC component, was observed in all the samples. The enthalpy of melting was directly proportional to the TC content in the system as shown in Figure 5. The reliability of the absorption enthalpy was determined by repeating 20 heat–cool cycles from 0 to 50 °C for representative sample T50P501 (containing equal mass ratios of TC and PC components). The peak melting temperature and the enthalpy of melting were observed to be at 31 °C and 0.422 ± 0.3 J g–1, respectively, after 20 cycles showing no apparent change in energy absorption compared to the control sample. TW composites therefore can be suitable for durable reversible storage applications. Successful processing is important, so that thermochromic moieties become well-dispersed in the final material and with few optical defects.

Figure 5.

Energy absorption analysis of TW composites. TW with (a) 100% TC, (b) 70% TC and 30% PC, (c) 50% TC and 50% PC, and (d) 30% TC and 70% PC at concentrations of 1, 3, and 5 wt % on the basis of polymer content. Inset at the top left corner demonstrates negligible change in enthalpy of absorption of a representative sample T50P501 after 20 heat–cool cycles from 0 to 50 °C.

Mechanical Properties of Chromic TW Composites

Mechanical tensile properties were measured in the fiber direction to investigate the influence, if any, of TC and PC components. Stress–strain curves are shown in Figure S4, and the values are presented in Table 2. Native 1.1 mm thiol–ene samples demonstrated tensile strength and modulus of 46 ± 2 MPa and 2.2 ± 0.3 GPa, respectively. For thiol–ene TW, a relative enhancement by 33% and 64% in the tensile strength and modulus values, respectively, was obtained as compared to the native thiol–ene material. Thus, efficient reinforcement of the thiol–ene was achieved with 11 ± 2 wt % wood in the composite system. A representative TW composite containing TC and PC and a combination of TC and PC in equal mass ratios, i.e., T1001, P1001, and T50P501, respectively, were analyzed, and their average tensile strength and modulus values are given in Table 2. As can be observed, tensile properties are not affected by inclusion of chromic components. The chromic components are located inside the lumen of the wood structure, completely embedded in the thiol–ene polymer matrix, and ultimate failure is likely to be controlled by the wood substrate rather than by the polymer matrix.

Table 2. Mechanical Properties of Chromic TW Composites.

| sample | tensile strength (MPa) | modulus (GPa) | strain at break (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thiol–ene film | 46 ± 3 | 2.2 ± 0.4 | 14 ± 3 |

| Thiol–ene TW | 61 ± 2 | 3.6 ± 0.3 | 1.8 ± 0.3 |

| T50P501 | 59 ± 2 | 3.6 ± 0.4 | 1,9 ± 0.2 |

| T1001 | 60 ± 2 | 3.7 ± 0.3 | 1.9 ± 0.4 |

| P1001 | 61 ± 3 | 3.8 ± 0.5 | 1.8 ± 0.2 |

Conclusions

Reversible chromic transparent wood, which is optically responsive to external stimuli of temperature or UV-light, was fabricated by using photopolymerization in a solvent-free process. Individual TC and PC properties are retained in the system as the components were selected to be nonreactive to each other as well as with the polymer system as a whole. The chromic components were found to be located inside the lumen of the wood structure, emphasizing their long-term retain compared to conventional chromic surface coating processes. Increase in the chromic component inclusion into the TW not only enhances the chromic optical effect but also slightly increases the haze of the composite. The selected trade-off between the enhancement of chromic properties and haze can depend on particular applications and can be realized by controlling the microcapsule load. The presence of TC also resulted in reversible energy absorption capacity, showing potential of these TW composites for thermal energy storage. Mechanical properties of the chromic TW composites are much improved compared with the neat polymer and on par with that of the native thiol–ene TW. Smart chromic TW structures can therefore be manufactured without compromising the mechanical properties of the native composite. This study explores the possibility toward the development of smart windows with energy storage capabilities and also demonstrates reversible dual-stimuli optical response from the wood-based biocomposites.

Acknowledgments

Martin Höglund is acknowledged for constructive discussions related to transparent wood fabrication. Erik Jungstedt is acknowledged for assistance in mechanical property measurements.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- TW

transparent wood

- CC

chromic components

- PETMP

pentaerythritoltetrakis(3-mercaptopropionate)

- TATAO

1,3,5-triallyl-1,3,5-triazine-2,4,6(1H,3H,5H)-trione

- DSC

differential scanning calorimetry

- TC

thermochromic component

- PC

photochromic component

- PCT

phase change temperature.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsami.0c21369.

SEM images of TC and PC pigments; transmission plots of chromic TW composites containing various compositions of chromic contents on exposure to temperature, UV, or both; table showing transmission values of chromic TW at 550 nm on exposure to UV, temperature, or both; DSC plots of TW composites; mechanical properties of TW composites (PDF)

This project has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program (grant agreement no. 742733, Wood NanoTech) and from the Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation through the Wallenberg Wood Science Center.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Zhu H.; Luo W.; Ciesielski P. N.; Fang Z.; Zhu J. Y.; Henriksson G.; Himmel M. E.; Hu L. Wood-Derived Materials for Green Electronics, Biological Devices, and Energy Applications. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116 (16), 9305–9374. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frey M.; Schneider L.; Masania K.; Keplinger T.; Burgert I. Delignified Wood-Polymer Interpenetrating Composites Exceeding the Rule of Mixtures. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11 (38), 35305–35311. 10.1021/acsami.9b11105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ates B.; Koytepe S.; Ulu A.; Gurses C.; Thakur V. K. Chemistry, Structures, and Advanced Applications of Nanocomposites from Biorenewable Resources. Chem. Rev. 2020, 120 (17), 9304–9362. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.9b00553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurunathan T.; Mohanty S.; Nayak S. K. A Review of the Recent Developments in Biocomposites Based on Natural Fibres and Their Application Perspectives. Composites, Part A 2015, 77, 1–25. 10.1016/j.compositesa.2015.06.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y.; Vasileva E.; Sychugov I.; Popov S.; Berglund L. Optically Transparent Wood: Recent Progress, Opportunities, and Challenges. Adv. Opt. Mater. 2018, 6 (14), 1800059. 10.1002/adom.201800059. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y.; Fu Q.; Yu S.; Yan M.; Berglund L. Optically Transparent Wood from a Nanoporous Cellulosic Template: Combining Functional and Structural Performance. Biomacromolecules 2016, 17 (4), 1358–1364. 10.1021/acs.biomac.6b00145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ansell M. P.Wood Microstructure - A Cellular Composite. In Wood Composites; Elsevier: 2015; pp 3–26. [Google Scholar]

- Chen C.; Kuang Y.; Zhu S.; Burgert I.; Keplinger T.; Gong A.; Li T.; Berglund L.; Eichhorn S. J.; Hu L. Structure-Property-Function Relationships of Natural and Engineered Wood. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2020, 5 (9), 642–666. 10.1038/s41578-020-0195-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ajao O.; Jeaidi J.; Benali M.; Restrepo A.; El Mehdi N.; Boumghar Y. Quantification and Variability Analysis of Lignin Optical Properties for Colour-Dependent Industrial Applications. Molecules 2018, 23 (2), 377. 10.3390/molecules23020377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horikawa Y.; Tsushima R.; Noguchi K.; Nakaba S.; Funada R. Development of Colorless Wood via Two-Step Delignification Involving Alcoholysis and Bleaching with Maintaining Natural Hierarchical Structure. J. Wood Sci. 2020, 66 (1), 37. 10.1186/s10086-020-01884-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y.; Wu J.; Yang F.; Tang C.; Huang Q. Effect of H2O2 Bleaching Treatment on the Properties of Finished Transparent Wood. Polymers 2019, 11 (5), 776. 10.3390/polym11050776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fink S. Transparent Wood - A New Approach in the Functional Study of Wood Structure. Holzforschung 1992, 46 (5), 403–408. 10.1515/hfsg.1992.46.5.403. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bi Z.; Li T.; Su H.; Ni Y.; Yan L. Transparent Wood Film Incorporating Carbon Dots as Encapsulating Material for White Light-Emitting Diodes. ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 2018, 6 (7), 9314–9323. 10.1021/acssuschemeng.8b01618. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Okahisa Y.; Yoshida A.; Miyaguchi S.; Yano H. Optically Transparent Wood-Cellulose Nanocomposite as a Base Substrate for Flexible Organic Light-Emitting Diode Displays. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2009, 69 (11–12), 1958–1961. 10.1016/j.compscitech.2009.04.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y.; Cheng M.; Jungstedt E.; Xu B.; Sun L.; Berglund L. Optically Transparent Wood Substrate for Perovskite Solar Cells. ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 2019, 7 (6), 6061–6067. 10.1021/acssuschemeng.8b06248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu M.; Li T.; Davis C. S.; Yao Y.; Dai J.; Wang Y.; AlQatari F.; Gilman J. W.; Hu L. Transparent and Haze Wood Composites for Highly Efficient Broadband Light Management in Solar Cells. Nano Energy 2016, 26, 332–339. 10.1016/j.nanoen.2016.05.020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gan W.; Xiao S.; Gao L.; Gao R.; Li J.; Zhan X. Luminescent and Transparent Wood Composites Fabricated by Poly(Methyl Methacrylate) and γ-Fe 2 O 3 @YVO 4:Eu 3+ Nanoparticle Impregnation. ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 2017, 5 (5), 3855–3862. 10.1021/acssuschemeng.6b02985. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y.; Yang H.; Ma C.; Luo S.; Xu M.; Wu Z.; Li W.; Liu S. Luminescent Transparent Wood Based on Lignin-Derived Carbon Dots as a Building Material for Dual-Channel, Real-Time, and Visual Detection of Formaldehyde Gas. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12 (32), 36628–36638. 10.1021/acsami.0c10240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu Z.; Xiao Z.; Gao L.; Li J.; Wang H.; Wang Y.; Xie Y. Transparent Wood Bearing a Shielding Effect to Infrared Heat and Ultraviolet via Incorporation of Modified Antimony-Doped Tin Oxide Nanoparticles. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2019, 172, 43–48. 10.1016/j.compscitech.2019.01.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yu Z.; Yao Y.; Yao J.; Zhang L.; Chen Z.; Gao Y.; Luo H. Transparent Wood Containing Cs x WO 3 Nanoparticles for Heat-Shielding Window Applications. J. Mater. Chem. A 2017, 5 (13), 6019–6024. 10.1039/C7TA00261K. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kortz C.; Hein A.; Ciobanu M.; Walder L.; Oesterschulze E. Complementary Hybrid Electrodes for High Contrast Electrochromic Devices with Fast Response. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10 (1), 4874. 10.1038/s41467-019-12617-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J.; Myoung J. Flexible and Transparent Electrochromic Displays with Simultaneously Implementable Subpixelated Ion Gel-Based Viologens by Multiple Patterning. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2019, 29 (13), 1808911. 10.1002/adfm.201808911. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jamdegni M.; Kaur A. Highly Efficient Dark to Transparent Electrochromic Electrode with Charge Storing Ability Based on Polyaniline and Functionalized Nickel Oxide Composite Linked through a Binding Agent. Electrochim. Acta 2020, 331, 135359. 10.1016/j.electacta.2019.135359. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rozman M.; Žener B.; Matoh L.; Godec R. F.; Mourtzikou A.; Stathatos E.; Bren U.; Lukšič M. Flexible Electrochromic Tape Using Steel Foil with WO3 Thin Film. Electrochim. Acta 2020, 330, 135329. 10.1016/j.electacta.2019.135329. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mariotti N.; Bonomo M.; Fagiolari L.; Barbero N.; Gerbaldi C.; Bella F.; Barolo C. Recent Advances in Eco-Friendly and Cost-Effective Materials towards Sustainable Dye-Sensitized Solar Cells. Green Chem. 2020, 22 (21), 7168–7218. 10.1039/D0GC01148G. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Syrrokostas G.; Dokouzis A.; Yannopoulos S. N.; Leftheriotis G. Novel Photoelectrochromic Devices Incorporating Carbon-Based Perovskite Solar Cells. Nano Energy 2020, 77, 105243. 10.1016/j.nanoen.2020.105243. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pulli E.; Rozzi E.; Bella F. Transparent Photovoltaic Technologies: Current Trends towards Upscaling. Energy Convers. Manage. 2020, 219, 112982. 10.1016/j.enconman.2020.112982. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Galliano S.; Bella F.; Bonomo M.; Viscardi G.; Gerbaldi C.; Boschloo G.; Barolo C. Hydrogel Electrolytes Based on Xanthan Gum: Green Route towards Stable Dye-Sensitized Solar Cells. Nanomaterials 2020, 10 (8), 1585. 10.3390/nano10081585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang A. W.; Li Y.; De Keersmaecker M.; Shen D. E.; Österholm A. M.; Berglund L.; Reynolds J. R. Transparent Wood Smart Windows: Polymer Electrochromic Devices Based on Poly(3,4-Ethylenedioxythiophene):Poly(Styrene Sulfonate) Electrodes. ChemSusChem 2018, 11 (5), 854–863. 10.1002/cssc.201702026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mi R.; Li T.; Dalgo D.; Chen C.; Kuang Y.; He S.; Zhao X.; Xie W.; Gan W.; Zhu J.; Srebric J.; Yang R.; Hu L. A Clear, Strong, and Thermally Insulated Transparent Wood for Energy Efficient Windows. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2020, 30 (1), 1907511. 10.1002/adfm.201907511. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L.; Wang A.; Zhu T.; Chen Z.; Wu Y.; Gao Y. Transparent Wood Composites Fabricated by Impregnation of Epoxy Resin and W-Doped VO 2 Nanoparticles for Application in Energy-Saving Windows. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12 (31), 34777–34783. 10.1021/acsami.0c06494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L.; Liu Y.; Zhan X.; Luo D.; Sun X. Photochromic Transparent Wood for Photo-Switchable Smart Window Applications. J. Mater. Chem. C 2019, 7 (28), 8649–8654. 10.1039/C9TC02076D. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Montanari C.; Li Y.; Chen H.; Yan M.; Berglund L. A. Transparent Wood for Thermal Energy Storage and Reversible Optical Transmittance. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11 (22), 20465–20472. 10.1021/acsami.9b05525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinelt S.; Tabatabai M.; Moszner N.; Fischer U. K.; Utterodt A.; Ritter H. Synthesis and Photopolymerization of Thiol-Modified Triazine-Based Monomers and Oligomers for the Use in Thiol-Ene-Based Dental Composites. Macromol. Chem. Phys. 2014, 215 (14), 1415–1425. 10.1002/macp.201400174. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Patel M. P.; Braden M.; Davy K. W. M. Polymerization Shrinkage of Methacrylate Esters. Biomaterials 1987, 8 (1), 53–56. 10.1016/0142-9612(87)90030-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y.; Yang X.; Fu Q.; Rojas R.; Yan M.; Berglund L. Towards Centimeter Thick Transparent Wood through Interface Manipulation. J. Mater. Chem. A 2018, 6 (3), 1094–1101. 10.1039/C7TA09973H. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zandi M.; Hashemi S. A.; Aminayi P.; Hosseinali F. Microencapsulation of Disperse Dye Particles with Nano Film Coating through Layer by Layer Technique. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2011, 119 (1), 586–594. 10.1002/app.32674. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fanchiotti B. G.; Machado M. P. Z.; de Paula L. C.; Durmuş M.; Nyokong T.; da Silva Gonçalves A.; da Silva A. R. The Photobleaching of the Free and Encapsulated Metallic Phthalocyanine and Its Effect on the Photooxidation of Simple Molecules. J. Photochem. Photobiol., B 2016, 165, 10–23. 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2016.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y.; Fu Q.; Rojas R.; Yan M.; Lawoko M.; Berglund L. Lignin-Retaining Transparent Wood. ChemSusChem 2017, 10 (17), 3445–3451. 10.1002/cssc.201701089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pike L. Optical Properties of Packaging Materials. J. Plast. Film Sheeting 1993, 9 (3), 173–180. 10.1177/875608799300900302. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H.; Baitenov A.; Li Y.; Vasileva E.; Popov S.; Sychugov I.; Yan M.; Berglund L. Thickness Dependence of Optical Transmittance of Transparent Wood: Chemical Modification Effects. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11 (38), 35451–35457. 10.1021/acsami.9b11816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y.; Fu Q.; Yang X.; Berglund L. Transparent Wood for Functional and Structural Applications. Philos. Trans. R. Soc., A 2018, 376 (2112), 20170182. 10.1098/rsta.2017.0182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Höglund M.; Johansson M.; Sychugov I.; Berglund L. A. Transparent Wood Biocomposites by Fast UV-Curing for Reduced Light-Scattering through Wood/Thiol-Ene Interface Design. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12 (41), 46914–46922. 10.1021/acsami.0c12505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y.; Gu X.; Gao H.; Li J. Photoresponsive Wood Composite for Photoluminescence and Ultraviolet Absorption. Construction and Building Materials 2020, 261, 119984. 10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2020.119984. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.