Abstract

Although lipids contribute to cancer drug resistance, it is challenging to target diverse range of lipids. Here we show enzymatically inserting exceedingly simple synthetic lipids into membranes for increasing membrane tension and selectively inhibiting drug resistant cancer cells. The lipid, formed by conjugating dodecylamine to D-phosphotyrosine, self-assembles to form micelles. Enzymatic dephosphorylation of the micelles inserts the lipids into membranes and increases membrane tension. The micelles effectively inhibit a drug resistant glioblastoma cell (T98G) or a triple-negative breast cancer cell (HCC1937), without inducing acquired drug resistance. Moreover, the enzymatic reaction of the micelles promotes the accumulation of the lipids in the membranes of subcellular organelles (e.g., endoplasmic reticulum (ER), Golgi, and mitochondria), thus activating multiple regulated cell death pathways. This work, as the first report that increases membrane tension for inhibiting cancer cells, illustrates a new and powerful supramolecular approach for antagonizing difficult drug targets.

Keywords: enzymatic insertion, lipids, membrane tension, cancer cells, drug resistance

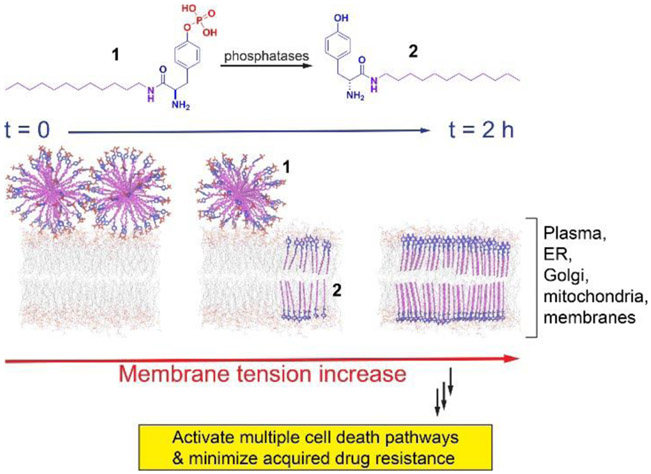

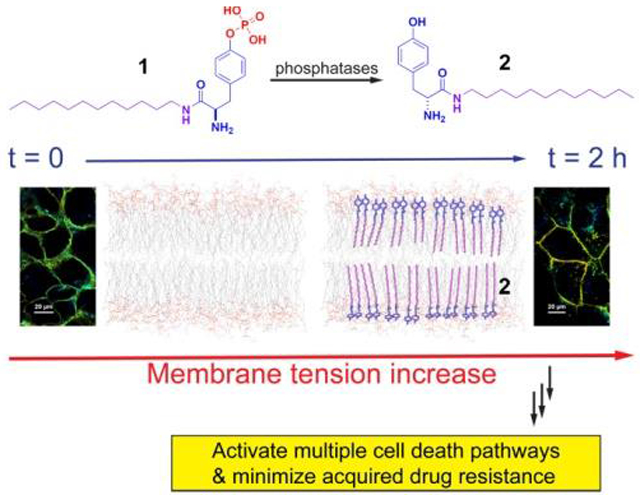

Graphical Abstract

We report that a synthetic lipid self-assembles to form micelles. Enzymatic dephosphorylation of the micelles inserts the lipids into membranes and increases membrane tension for effectively inhibiting cancer cells without inducing acquired drug resistance. This work, as the first report that increases membrane tension for inhibiting cancer cells, illustrates a new and powerful supramolecular approach for antagonizing difficult drug targets.

Lipids, the predominant components of membranes of cells and subcellular organelles, play a central role in maintaining biological molecular organization.[1] Recently, emerging evidence suggests that lipids regulate the expression and activity of multidrug efflux pumps in cancer cells, thus contributing to the multidrug resistance (MDR) of cells.[2] MDR cells exhibit unique features, including the altered composition of phospholipids and glycosphingolipids in plasma membrane[3] or membranes of intracellular organelles (e.g., endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and mitochondria, and Golgi apparatus),[4] the high ratio of monounsaturated/polyunsaturated fatty acid,[5] and highly produced precursors of phospholipids and cholesterol.[6] All these features confer the emergence of MDR in cancer cells, which have stimulated the efforts for targeting lipids of MDR cells. Current approaches, such as repurposing lipid-targeting drugs[7] or lipid analogues,[8] remain ineffective. Therefore, it is necessary to develop novel approaches that simultaneously perform multiple functions, such as directly targeting subcellular membranes, selectively inhibiting proliferation, and effectively minimizing the emergence of drug resistance of cancer cells.

Based on that the conjugate of cholesterol and phosphotyrosine is able to augment lipid rafts for selectively inhibiting ovarian cancer cells in vitro and in vivo,[9] we decided to combine phosphotyrosine with a simple alkylamine to generate enzyme-responsive synthetic lipids for targeting cellular membranes and inhibiting cancer cells selectively. Our studies reveal that an exceedingly simple enzyme-responsive lipid, ((R)-4-(2-amino-3-(dodecylamino)-3-oxopropyl)phenyl dihydrogen phosphate (1)), self-assembles to form micelles, which selectively kills a glioblastoma cell (T98G) or a triple-negative breast cancer cell (HCC1937), without inducing acquired drug resistance to 1. The enzymatic dephosphorylation of the micelles of 1 inserts the resulted lipid ((R)-2-amino-N-dodecyl-3-(4-hydroxyphenyl)propenamide (2)) into cellular membranes to increase membrane tension, thus activating multiple regulated cell death pathways (Scheme 1). This enzymatic reaction also promotes the accumulation of the lipids in the membranes of subcellular organelles (e.g., ER, Golgi, and mitochondria). Using the enzymatic reaction of the micelles of synthetic lipids for inhibiting drug resistant cancer cells, this work illustrates a powerful supramolecular approach for antagonizing difficult drug targets.

Scheme 1.

Illustration of enzymatically inserting synthetic lipids to increase cell membrane tension and to induce cell death.

Scheme S1 shows the structures of molecules as the enzymatic-instructed lipids for targeting membranes. The synthetic lipids consist of two crucial features: an enzymatic trigger (i.e., a tyrosine phosphate as a substrate of phosphatase) and a simple alkylamine. By connecting dodecan-1-amine to the carboxyl group of D-configuration of phosphotyrosine, we generated the representative synthetic lipid, 1. The direct capping the C-terminal of tyrosine by dodecan-1-amine produces 2 for verifying whether enzymatic dephosphorylation is essential for inhibiting cancer cells. To visualize the uptake and distribution of the synthetic lipids in cells, we conjugated an environment-sensitive fluorophore (i.e., 4-nitro-2,1,3-benzoxadiazole, NBD) at the end of alkyl chain of 1, forming 3 for fluorescent imaging of the assemblies of the lipids. 4 is the enzymatic product of 3. To understand the effect of stereochemistry of phosphotyrosine on the activity of the synthetic lipid, we used L-configuration of phosphotyrosine to produce 5. We made 6 and 7 to compare the inhibitory activity of C-terminal synthetic lipids with that of N-terminal synthetic lipids against cancer cells. Capping the hydroxyl group in phosphotyrosine with ethyl group generates 8 to compare phosphate ester with phosphate in the enzymatic response. We used phosphoserine and phosphothreonine to replace phosphotyrosine, generating 9 and 10, respectively, for understanding the difference of tyrosine with serine and threonine. In addition, we also investigated the influence of the hydrophobic chain length on the inhibitory activity of the lipids against cancer cells by using hexylamine and hexadecylamine to cap the C-terminal of D-phosphotyrosine for making 11 and 12, respectively. Trimethylation of the N-terminal of 1 produces 13, for further confirming the need to expose the N-terminal amine.

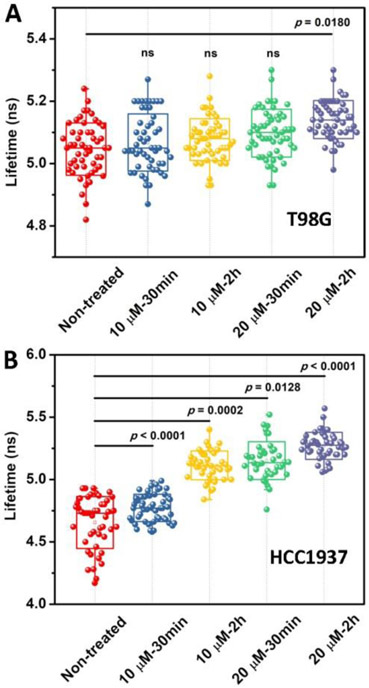

The TEM images (Figure S1) confirm the self-assembly of 1 to form big aggregates or micelles at different concentrations. The critical micelle concentration (CMC) of 1 is 22.0 μM in PBS buffer, whereas the CMC of 2 is 11.0 μM (Figure S2), confirming that dephosphorylation increases the hydrophobicity of the synthetic lipids for membrane insertion. Because the insertion of lipids in the membrane likely alters the mechanical properties of the plasma membrane that involves in regulating various biochemical processes in cells, we used a mechanosensitive flipper probe (Flipper-TR),[10] which responded to the change of plasma membrane tension by changing its fluorescence lifetime and thus allowed tension imaging by fluorescent lifetime imaging microscopy (FLIM), to measure the change of the membrane tension of T98G and HCC1937 cells. As shown in Figure 1, the lifetime of Flipper-TR in T98G cells is 5.05 ns in the absence of 1. After being treated with 1 at the concentration of 10 μM for 30 min or 2 h, the lifetime of Flipper-TR is 5.07 and 5.08 ns, respectively, which are similar with that of non-treated cells, implying little change of membrane tension at the concentrations below CMC of 1 for short times. After increasing the concentration of 1 to 20 μM and incubating T98G cells for 30 min or 2 h, the lifetime of Flipper-TR rises to 5.10 and 5.14 ns, respectively, indicating that the more assemblies of the 2 generated from longer incubation of 1 slightly increase plasma membrane tension of T98G cells. The FLIM in HCC1937 cells shows significant increase of membrane tension (Figure 1B). The lifetime of Flipper-TR in HCC1937 cells is 4.65 ns in the absence of 1. After being treated with 1 at the concentration of 10 μM for 30 min, the lifetime of Flipper-TR is 4.77 ns, which is slightly higher than that of non-treated cells. With continuously increasing the incubation time of 1 to 2 h, the lifetime of Flipper-TR increases to 5.12 ns, implying the increased tension. After increasing the concentration of 1 to 20 μM for treating the HCC1937 cells, the lifetime of Flipper-TR is 5.16 ns and 5.27 ns, for 30 min and 2 h incubation, respectively. The increase of the membrane tensions with the increase of the concentration and incubation time of 1 confirms that enzymatic dephosphorylation of the micelles of 1 inserts 2 into the plasma membrane to increase membrane tension (Scheme 1).

Figure 1.

The FLIM of (A) T98G and (B) HCC1937 cells incubated with 1 at the concentration of 10 μM and 20 μM for 30 min and 2 h, respectively, and then stained with Flipper-TR.

To investigate the inhibitory activity against cancer cells, we examined the viability of HeLa cells (a cervical cancer cell line) cultured with 1-13. Figure S3 shows the IC50 values of these synthetic lipids against the HeLa cells for 24 h. 1, containing D-phosphotyrosine, exhibits the highest cytotoxicity with IC50 of 21.0 μM (9.0 μg/mL). 2 hardly displays any cytotoxicity against HeLa cells with IC50 of more than 100 μM, indicating that the enzymatic dephosphorylation is essential for inhibiting cancer cells, and the tyrosine lipids, if not being generated in situ, are innocuous to the cancer cells. 3, as the fluorescent analog of 1, exhibit a comparable IC50 value, 37.6 μM, with that of 1. After the replacement of D-tyrosine phosphate by L-tyrosine phosphate, 5 shows a slightly lower cytotoxicity than that of 1 with IC50 of 43.4 μM. The IC50 of 6 and 7 are both more than 100 μM against HeLa cells, which are much higher than that of 1, suggesting that the amine at N-terminal of synthetic lipids is essential for the inhibitory activity against the cancer cells. This feature differs from the case of cholesterol-tyrosine conjugate, which exposes C-terminal.[9b] With the ethyl group to cap the hydroxyl group in phosphotyrosine, 8 exhibits a IC50 value of 80.3 μM, which implies that the enzymatic response of the phosphate ester is lower than that of phosphate towards cancer cells. 9 and 10 exhibit with IC50 values of 61.8 μM and 96.8 μM, respectively, indicating that dephosphorylation of phosphoserine or phosphothreonine on the synthetic lipids is ineffective for inhibiting cancer cells. While 11 shows IC50 of more than 100 μM, the IC50 of 12 is 25.2 μM (12.2 μg/mL), indicating that sufficient chain length of the lipids for self-assembly is a prerequisite for the inhibitory activity against cancer cells. 13 shows IC50 of 33.8 μM, implying that the exposure of N-terminal amine is significant for the high activity of the synthetic lipids.

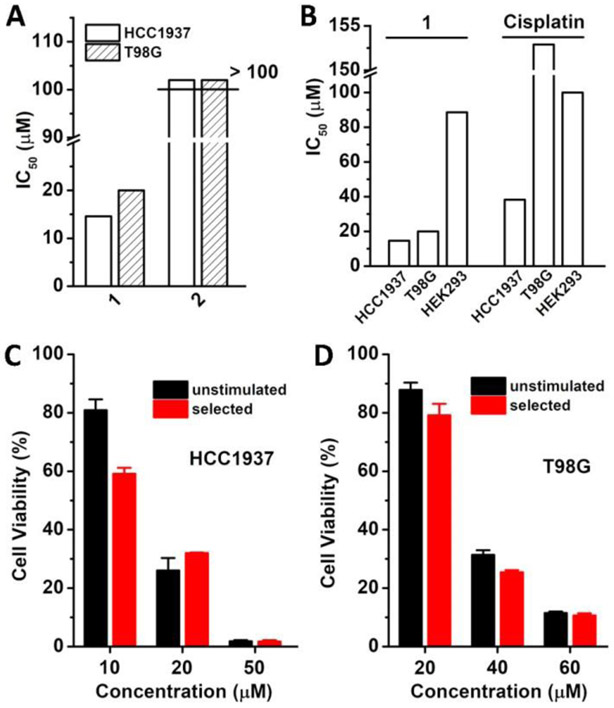

Figure 2A shows the IC50 values of 1 and 2 incubated with HCC1937 and T98G cells for 24 h. While 1, exhibits the IC50 of 14.6 μM (6.2 μg/mL) and 20.0 μM (8.6 μg/mL) against HCC1937 and T98G cells, respectively. Thus, to ensure most of cells alive for imaging study, we incubated HCC1937 and T98G cells at the concentration below CMC (22.0 μM) to measure the FLIM. 2 hardly displays cytotoxicity against both of HCC1937 and T98G cells with IC50 of more than 100 μM. This result indicates that the enzymatic dephosphorylation of the micelles of 1 is essential for generating 2 in situ for inserting in the membrane and inhibiting the cancer cells. We also compared the viability of HEK293 (embryonic kidney cell, as a model of normal cells), T98G, and HCC1937 cells, incubated with 1 and cisplatin (Figure 2B). 1 exhibits high cytotoxicity against T98G and HCC1937 cells, while shows low cytotoxicity against HEK293 cells, with IC50 of 88.6 μM. Meanwhile, cisplatin, at relatively high concentrations, inhibits HCC1937 (IC50: 38.2 μM) and T98G (IC50: 152.9 μM), which are higher than that of 1. This result also indicates that 1 is more effective and selective than cisplatin against T98G and HCC1937 cancer cells, two of most malignant tumor cells. Moreover, the cytotoxicity of 1 towards T98G and HCC1937 cells agrees with the increment of membrane tension by 1. In addition, we also examined several different cell lines incubated with 1 to investigate its applicability to other cancer cells. As shown in Figure S4, 1 shows slightly different inhibitory activity against different cells (HeLa: IC50 of 36.8 μM, Saos-2: IC50 of 30.7 μM, MCF7: IC50 of 62.1 μM, A2780: IC50 of 31.7 μM, OVCAR-4: IC50 of 34.0 μM, JHOS-4: IC50 of 37.5 μM, SKOV-3: IC50 of 40.0 μM, HepG2: IC50 of 45.2 μM, A2780Res: IC50 of 55.2 μM, GEMM4306: IC50 of 57.6 μM, and ACHN: IC50 of 25.0 μM), which likely are resulted from different expression levels of phosphatases in different cell lines. Notably, 1, at the concentration of 25.0 μM, inhibits renal cancer cells (ACHN), but is innocueous to human embryonic kidney cells (HEK293).

Figure 2.

The IC50 values of (A) 1 and 2 against HCC1937 and T98G cells and of (B) 1 and cisplatin against HCC1937, T98G and HEK293 cells for 24 h. Cell viability of unstimulated (C) HCC1937 and (D) T98G cells or selected HCC1937 and T98G cells incubated with 1 at different concentrations for 24 h.

Since acquired drug resistance remains a challenge for developing anticancer therapeutics, we further examined whether the micelles of 1 would result in acquired resistance. According to an established method to select drug resistant cancer cells,[11] we incubated HCC1937 and T98G cells with 1 by gradually increasing the concentrations of 1 from 5 μM to 15 μM for 30 days and selected the cells that survived the treatment. Subsequently, we assessed the selected HCC1937 and T98G cells with 1 by MTT assay. As shown in Figure 2C and 2D, the IC50 of 1 against the selected HCC1937 and T98G cells are 14.0 and 28.0 μM, respectively. These values are close to the IC50 values of 1 against unstimulated HCC1937 (16.0 μM, 30 days incubation in culture medium) and T98G cells (32.0 μM, 30 days incubation in culture medium), indicating that 1 hardly induces the acquired drug resistance. These results suggest that enzymatic reaction of lipid micelles promises a new strategy for minimizing acquired drug resistance.

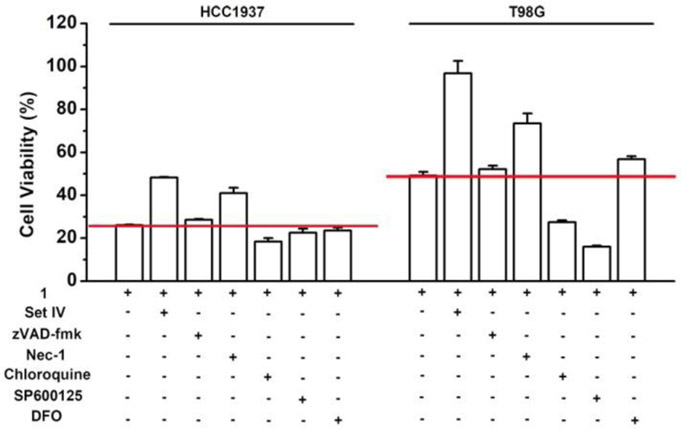

The lack of acquired drug resistance by T98G and HCC1937 to 1 suggests that the enzymatic reaction of the micelles of 1 likely activates multiple cell death pathways. Firstly, we co-incubated the cocktail of phosphatase inhibitor Set IV, which inhibited protein phosphatases and alkaline phosphatases,[12] with 1, and found that the inhibitor cocktail doubles the viability of T98G and HCC1937 (Figure 3). This result confirms that the in situ dephosphorylation contributes to the cell death. Considering that the main types of regulated cell death include apoptosis, necroptosis, lysosome-dependent cell death, ferroptosis and autophagy-dependent cell death,[13] we selected several representative inhibitors to examine whether they rescue cells from 1, such as zVAD-fmk (carbobenzoxy-valyl-alanyl-aspartyl-[O-methyl]-fluoromethylketone, a caspase inhibitor that blocks apoptosis),[14] Nec-1 (necrostatin-1, a RIPK1 inhibitor that blocks necroptosis),[15] chloroquine (a lysosomal inhibitor that blocks autophagy-dependent cell death),[16] SP600125 (a JNK inhibitor that blocks necrosis and apoptosis),[17] DFO (deferoxamine mesylate, an iron-chelating agent that blocks ferroptosis and lysosome-dependent cell death)[18] and NAC (N-acetyl cysteine, an ROS (reactive oxygen species) inhibitor that blocks ferroptosis, lysosome-dependent cell death, and oxeiptosis).[19] As shown in Figure 3, zVAD-fmk hardly rescues HCC1937 and T98G cells and Nec-1 only moderately increases the cell viability of HCC1937 and T98G cells. In addition, neither of chloroquine and SP600125 rescues HCC1937 and T98G cells, while DFO can only rescue T98G cells slightly. NAC, at 1 mM, is able to significantly increase the viabilities of HCC1937 and T98G (Figure S5). Notably, the coincubation of chloroquine and SP600125 with 1 actually increases the toxicity against T98G cells, implying enhanced cell death, which is consistent with reported literatures that inhibitors of autophagy (e.g., chloroquine) induce protective autophagy in glioblastoma[20] and the inhibition of glioblstoma cells’ proliferation is a direct consequence of JNK inhibition (e.g., SP600125).[21] Since none of the inhibitors completely rescue the cancer cells from the inhibitory activity of 1, the enzymatic lipid insertion induces the cell death via multiple regulated cell death pathways, likely depends more on ferroptosis, lysosome-dependent cell death, and/or oxeiptosis.

Figure 3.

Cell viability of HCC1937 and T98G cells treated by 1 (20 μM) in the presence of phosphatase inhibitors or cell death signaling inhibitors at 24 h. [zVAD-fmk] = [Nec-1] = [SP600125] = 50 μM; [Chloroquine] = [DFO] = 100 μM; phosphatase inhibitor cocktail IV (Set IV) was diluted 4000 times.

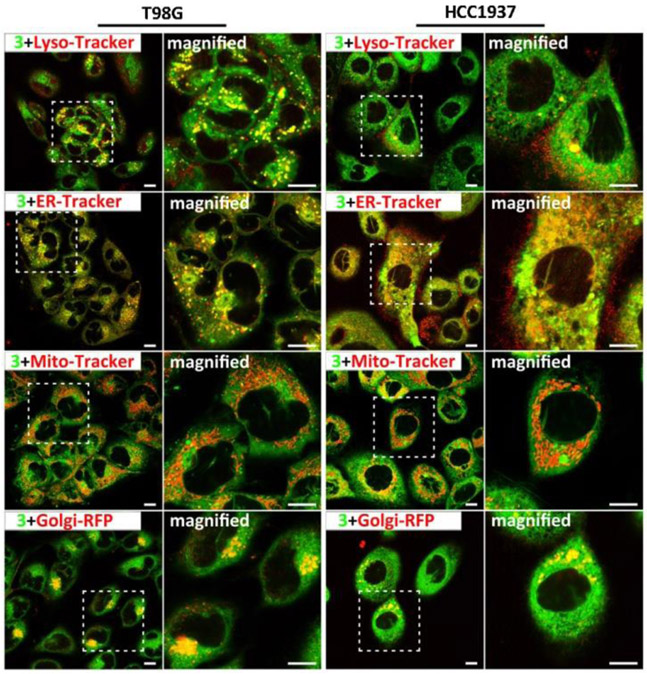

To visualize the distribution of the synthetic lipids in cells, we conjugated an environment-sensitive fluorophore (i.e., 4-nitro-2,1,3-benzoxadiazole, NBD) at the end of alkyl chain of 1, forming 3 for fluorescent imaging of the assemblies of the lipids (Scheme S1).[22] Similar to the case of 1, the enzymatic reaction of the micelles of 3 would insert the assemblies of 4 (Scheme S1) into membranes and inhibit the cancer cells, albeit with slightly higher IC50 (Table S2). Figure 4 shows the confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM) images of T98G and HCC1937 cells stained with LysoTracker™ Deep Red (Lyso-Tracker),[23] ER-Tracker™ Red dye (ER-Tracker),[24] MitoTracker™ Deep Red FM (MitoTracker)[25] or transfected with CellLight™ Golgi-RFP (Golgi-RFP),[26] and then treated with 3, respectively. In T98G cells, most of green fluorescent dots, belonging to the assemblies of 4, colocalize well with the red dots of ER-Tracker, suggesting that most of the enzyme-instructed lipid assemblies accumulate on the membrane of ER. Meanwhile, the red dots of Lyso-Tracker, MitoTracker and Golgi-RFP also overlap with the green dots from the assemblies of 4. The co-localization with Lyso-Tracker likely implies the uptake of the synthetic lipids by cells via endocytosis. The co-localization with Mito-Tracker and Golgi-Tracker indicates that the synthetic lipids also accumulate in these two cellular organelles (i.e., mitochondria and Golgi) after escaping from the lysosomes. In the case of HCC1937 cells, the assemblies of 4 also localize in multiple subcellular membranes (i.e., ER, mitochondria and Golgi). Notably, 4 appears to overlap less with the Golgi of HCC1937 than with that of T98G. This observation is consistent with that 1 shows the high cytotoxicity against HCC1937 cells. The cellular distribution of the assemblies of 4 in the membranes of multiple cellular organelles also agrees with the activation of multiple regulated cell death pathways by 1.

Figure 4.

CLSM images of T98G and HCC1937 cells stained with Lyso-Tracker (Red), ER-Tracker (Red), Mito-Tracker (Red) or transfected with Golgi-RFP (Red), and then treated with 3 (Green, 20 μM) for 30 min. Scale bar is 10 μm.

In summary, by rationally designing the enzyme-responsive lipids, examining membrane tensions, and evaluating the acquired drug resistance, we validated the use of enzymatic reaction of the micelles of lipids as an effective approach for inserting lipids in the membranes. Notably, this simple lipid is more than 10 times effective than peptide amphiphiles that are the substrates of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs).[27] In addition, it is unusual that the enzymatic reaction of such an exceedingly simple lipid is able to inhibit cancer cells. These enzyme-responsive micelles of lipids illustrate novel alternatives of peptides[28] for interacting with cell membrane holistically and underscore the promise of the reactions of supramolecular assemblies for inhibiting drug-resistant cancer cells, which eventually may open up new directions to address the enormous complexity of cancer cells.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work is partially supported by NIH (R01CA142746) and NSF (DMR-2011846).

Footnotes

Supporting information for this article is given via a link at the end of the document.

References

- [1].a) Simons K, Ikonen E, Nature 1997, 387, 569–572; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Maxfield FR, Tabas I, Nature 2005, 438, 612–621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Kopecka J, Trouillas P, Gašparović AČ, Gazzano E, Assaraf YG, Riganti C, Drug Resist. Update 2020, 49, 100670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Gouaze-Andersson V, Cabot MC, BBA - Biomembranes 2006, 1758, 2096–2103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Alexa-Stratulat T, Pešić M, Gašparović AČ, Trougakos IP, Riganti C, Drug Resist. Update 2019, 46, 100643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].a) Brachtendorf S, Wanger RA, Birod K, Thomas D, Trautmann S, Wegner M-S, Fuhrmann DC, Brüne B, Geisslinger G, Grösch S, BBA – Mol. Cell Biol. L 2018, 1863, 1214–1227; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Shen S, Yang L, Li L, Bai Y, Cai C, Liu H, J. Chromatogr. B 2017, 1068-1069, 41–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Chantemargue B, Di Meo F, Berka K, Picard N, Arnion H, Essig M, Marquet P, Otyepka M, Trouillas P, Pharmacol. Res 2018, 133, 318–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Hennessy E, Adams C, Reen FJ, Gara F, Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 2016, 60, 5111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Escribá PV, Trends Mol. Med 2006, 12, 34–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].a) Wang H, Feng Z, Wu D, Fritzsching KJ, Rigney M, Zhou J, Jiang Y, Schmidt-Rohr K, Xu B, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2016, 138, 10758–10761; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Wang H, Feng Z, Yang C, Liu J, Medina JE, Aghvami SA, Dinulescu DM, Liu J, Fraden S, Xu B, Mol. Cancer Res 2019, 17, 907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Goujon A, Colom A, Straková K, Mercier V, Mahecic D, Manley S, Sakai N, Roux A, Matile S, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2019, 141, 3380–3384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Riganti C, Miraglia E, Viarisio D, Costamagna C, Pescarmona G, Ghigo D, Bosia A, Cancer Res. 2005, 65, 516. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Fernley HN, in The Enzymes, Vol. 4 (Ed.: Boyer PD), Academic Press, 1971, pp. 417–447. [Google Scholar]

- [13].Tang D, Kang R, Berghe TV, Vandenabeele P, Kroemer G, Cell Res. 2019, 29, 347–364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Yaoita H, Ogawa K, Maehara K, Maruyama Y, Circulation 1998, 97, 276–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Jouan-Lanhouet S, Arshad MI, Piquet-Pellorce C, Martin-Chouly C, Le Moigne-Muller G, Van Herreweghe F, Takahashi N, Sergent O, Lagadic-Gossmann D, Vandenabeele P, Samson M, Dimanche-Boitrel MT, Cell Death Differ. 2012, 19, 2003–2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Gonzalez-Noriega A, Grubb JH, Talkad V, Sly WS, J. Cell Biol 1980, 85, 839–852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Bennett BL, Sasaki DT, Murray BW, Leary EC, Sakata ST, Xu W, Leisten JC, Motiwala A, Pierce S, Satoh Y, Bhagwat SS, Manning AM, Anderson DW, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 2001, 98, 13681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Lv Q, Wang H, Shao Z, Xing L, Yue L, Liu J, Blood 2019, 134, 2995–2995. [Google Scholar]

- [19].Oh S-H, Lim S-C, Toxicol. Appl. Pharm 2006, 212, 212–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Yuan G, Yan S-F, Xue H, Zhang P, Sun J-T, Li G, J. Biol. Chem 2014, 289, 10607–10619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Du L, Lyle CS, Obey TB, Gaarde WA, Muir JA, Bennett BL, Chambers TC, J. Biol. Chem 2004, 279, 11957–11966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Gao Y, Shi J, Yuan D, Xu B, Nat. Commun 2012, 3, 1033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Radad KS, Al-Shraim MM, Moustafa MF, Rausch W-D, Neurosciences (Riyadh) 2015, 20, 10–16. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Peshenko IV, Olshevskaya EV, Dizhoor AM, J. Biol. Chem 2008, 283, 21747–21757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Zhou R, Yazdi AS, Menu P, Tschopp J, Nature 2011, 469, 221–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Céspedes PF, Bueno SM, Ramírez BA, Gomez RS, Riquelme SA, Palavecino CE, Mackern-Oberti JP, Mora JE, Depoil D, Sacristán C, Cammer M, Creneguy A, Nguyen TH, Riedel CA, Dustin ML, Kalergis AM, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 2014, 111, E3214–E3223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Tanaka A, Fukuoka Y, Morimoto Y, Honjo T, Koda D, Goto M, Maruyama T, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2015, 137, 770–775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].a) Gao J, Zheng H, Future Med. Chem 2013, 5, 947–959; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Hosseini AS, Zheng H, Gao J, Tetrahedron 2014, 70, 7632–7638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.