Abstract

Purpose:

To describe racial/ethnic differences and clinical/treatment correlates of worry about recurrence and examine modifiable factors in the health care experience to reduce worry among breast cancer survivors, partners and pairs.

Methods:

Women with non-metastatic breast cancer identified by the Detroit and Los Angeles SEER registries between 6/05–2/07 were surveyed at 9 months and 4 years. Latina and black women were oversampled. Partners were surveyed at Time 2. Worry about recurrence was regressed on sociodemographics, clinical/treatment, and modifiable factors (e.g., emotional support received by providers) among survivors, partners and pairs.

Results:

The final sample included 510 pairs. Partners reported more worry about recurrence than survivors. Compared to whites, Latinas(os) were more likely to report worry and blacks were less likely to report worry (all p < 0.05). Partners of survivors who received chemotherapy reported more worry (OR = 2.47[1.45, 4.22]). Among modifiable factors, survivors and pairs who received more emotional support from providers were less likely to report worry than those survivors and pairs who did not receive such support (OR = 0.56 [0.32, 0.97]) and (OR=0.45 [0.23,0.85]), respectively.

Conclusions:

Early identification of survivors and partners who are reporting considerable worry about recurrence can lead to targeted culturally sensitive interventions to avoid poorer outcomes. Interventions focused on health care providers offering information on risk and emotional support to survivors and partners is warranted.

INTRODUCTION

Helping families cope with cancer and manage continuing concerns in survivorship has been identified as a priority for delivering quality cancer care. Women with breast cancer rank worry or fear about recurrence (hereafter referred to as worry) among their most pressing concerns in survivorship [1–4], and studies have found that partners and/or family caregivers report even more worry than survivors [5, 6]. There is a growing recognition that couples react to the diagnosis of cancer as an “emotional system,” mutually influencing each other’s worry [5, 7, 8], suggesting that the survivor-partner pair must be viewed as the most appropriate “unit of care” [9]. Assessment and greater focus on worry is essential for survivors and partners given its documented impact on quality of life (QOL) [1, 2, 10]. Similarly, when a partner’s worry goes unrecognized, it can impact the entire family’s QOL, including the survivor [5, 8, 11].

Several studies have identified factors associated with worry, especially age [4, 12]. However, most studies have focused on survivor worry early in survivorship, and have been limited by relatively small, clinic-based samples. These studies have found black women worry less while Latinas worry more than whites [13]. When acculturation has been measured across health outcomes for cancer survivors, Latinas with low acculturation experience more worry [12]. An important area of research is to identify disparities in worry across racial/ethnic groups, and further, to determine if similar factors influence worry among partners and pairs. Survivor comorbidities and symptoms may contribute to greater worry [5] while the findings are mixed on the association between treatment course and worry [3, 14]. The extent to which the treatment course of survivors influences partner worry has not been explored in depth.

Few studies have examined whether modifiable factors in the health care experience (e.g., information around risk of recurrence, emotional support from providers) influence persistent worry among survivors, partners or pairs. Receipt of emotional support has been shown to be important to survivor outcomes, however, most studies have focused on emotional support received from family and friends [15]. How often survivors or partners receive emotional support from providers remains unclear, as both oncologists and primary care providers perceive that they provide the majority of emotional support [16]. The amount survivors and partners worry could be enhanced if their “perceived risk” of cancer recurrence is higher than the “actual risk.” Cancer care and primary care health care teams have opportunities to discuss risk, assess worry, and provide emotional support in an effort to manage considerable worry among survivors and partners.

By better understanding modifiable factors that make survivors, partners and pairs more vulnerable to persistent worry, high-risk populations can be identified and targeted, and interventions tailored to these specific components affecting risk. To address these gaps, we used a large multi-ethnic population-based sample of women with breast cancer and their partners to (1) describe the racial/ethnic differences and clinical and treatment correlates of worry among breast cancer survivors, their partners and survivor-partner pairs four years following breast cancer diagnosis and, (2) assess the association of potentially modifiable factors (receipt of emotional support from providers and, receipt of information about risk of recurrence) on worry about recurrence.

METHODS

Study Population and Data Collection

The study population included breast cancer survivors and their partners. We initially identified women with breast cancer in Los Angeles (LA), California and Detroit, Michigan. Eligible participants were women 20–79 years old, diagnosed with ductal carcinoma in situ or invasive breast cancer from June 2005, through February 2007, and reported to the National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) registry. Asian women in LA were excluded because of enrollment in other studies. Black and Latina women were oversampled in LA to ensure sufficient representation of racial/ethnic minorities. A total of 3,252 women were surveyed at about 9 months after diagnosis (Time 1) and 2,290 (73.1%) completed the survey. Time 1 respondents were surveyed again 4 years after diagnosis (Time 2) and 1,536 (67.7%) completed the survey. Details of the Time 1 and Time 2 surveys have been previously published [10, 17].

For the partner survey, 774 women who reported being married/living with partner at Time 1 and 2 were asked to give a survey packet to their partners from October 2010 to February 2012. The partner packet included an introductory letter, survey, $10 cash gift, and a return envelope. All materials were in English and Spanish if the respective survivors had Spanish surnames. A modified Dillman method [18] was used to encourage response. Of 774 potential eligible partners, 517 (67%) completed the survey. Details of the partner survey has been previously published [19]. Our final sample included 510 pairs of survivors and their respective partners. We refer to our study subjects as survivors, partners, and pairs.

All study protocols were approved by the institutional review boards of the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, the University of Southern California, and Wayne State University.

Measures

A modified stress and appraisal conceptual framework based on Lazarus and used by Northouse provided guidance for our research [20]. The framework includes antecedent factors (personal factors and illness-related factors of survivors and/or their partners), proximal outcomes (e.g., appraisal factors and coping factors of survivors and/or their partners) and the distal outcome (i.e., level of worry about recurrence four years after diagnosis) for survivors, their partners, and the pairs. All survivor measures were assessed at Time 2 (approximately four years after breast cancer diagnosis) unless indicated otherwise.

Dependent Variables

For survivors, worry was measured as the mean of three items (i.e., worry about cancer coming back in the same breast, in the other breast, and to other parts of my body) on a 5-point Likert scale (“not at all” to “a lot”). The mean score was 2.3 (SD=1.0, min=1, max=5), with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.87. For partners, worry was measured by “how often they worry about the possibility that their spouse or partner’s breast cancer might recur” on a 5-point Likert scale (“not at all” to “a lot”). The mean score was 2.5 (SD=1.1, min=1, max=5). For purposes of analyses, worry was dichotomized as follows: for survivors and partners, those with mean scores for worry ≥ 3 were considered as “worriers”; otherwise, considered “non-worriers”. For pairs, to be considered as “worriers,” both the survivor and partner had to be “worriers.”

Independent Variables

For survivors and partners, personal factors included age (<50, 50-<65 and ≥65 years), education (high school education or less, some college education or more). Race was assessed as white, black/African American, American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian or Pacific Islander, or other; and, ethnicity (yes/no for Hispanic/Latino) in order to subsequently categorize into non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black and Latinos. The Short Acculturation Scale for Hispanics [21] assessed their preferences for English or Spanish in four different social contexts, as has been done in previous work [22–23]. Responses to the four items were averaged and then dichotomized into lower acculturation (≤4) and higher acculturation (>4) to survivors and partners, subsequently referred to as Latino-low and Latino-high. Current health was measured on a 5-point scale from “poor” to “excellent,” and then dichotomized into “excellent/very good/good” vs. “fair/poor.” Number of comorbidities was categorized into “none” vs “ ≥1” using the Charlson comorbidity index [24]. For survivors, at Time 1, clinical factors included tumor stage, surgery, radiation (yes/no) and chemotherapy (yes/no). Survivors and partners were asked if they received enough information on the risk of recurrence from the doctors or the staff (yes/no). For the pair, both survivor and partner had to indicate “yes” to receiving enough information. Receipt of emotional support from health care providers was measured on a scale from 1 to 5 (“none” to “a lot”). We categorized partners and survivors as having received sufficient emotional support if the score was ≥ 3. For pairs, to be designated as having received emotional support, both survivor and partner needed to have a score ≥3.

Statistical Methods

We compared 264 survivors who were partnered but whose partners did not return their surveys with 510 survivors whose partners responded, and calculated summary statistics for variables on survivors and partners included in our analytical sample. To compare distributions of variables between survivors and their partners, we used Stuart-Maxwell tests to account for the correlation between survivors and their partners. We described the percent of survivors and partners who worried at four years in each subgroup defined by personal factors, illness-related factors and proximal outcomes. We then used unadjusted logistic regression to estimate whether there was an association between worry by survivors (partners) and each characteristic.

Two separate logistic regression models were fit, without and with proximal outcomes, for level of survivor, partner or pair worry. We fit two additional logistic regression models: One added partners’ worry into the survivor model and the other added survivor worry into the partner worry model while retaining all other factors. Race/ethnicity, education and age had a small amount of missing data (between 0.1% −8%). We imputed missing values by assigning them to the partner’s response if available based on high concordance observed in these variables within pairs. All analyses were conducted using R package, version 3.1.1 (Vienna, Austria).

RESULTS

Compared to non-responders, partners who did respond were significantly more likely to be white, older, have some college education or higher but were less likely to be Latinos-low or have survivors who received chemotherapy, (all p <0.05). Table 1 presents the sample characteristics of survivors and their partners four years after diagnosis. Survivors and partners were similar on most characteristics except survivors were significantly younger than their partners (e.g., 31.0% vs 43.5% being 65 or over). Among survivors, 59.8%, 12.9%, 13.9% and 12.2% were white, black, Latino-high and Latino-low; and 63.5%, 25.1% and 10.0% had lumpectomy, unilateral mastectomy and bilateral mastectomy. In addition, partners were significantly more likely to report receiving enough information about the risk of recurrence than survivors (71.1% vs. 64.7%, p=0.003); but less likely to report receiving sufficient emotional support from providers (45.7% vs. 75.0%, p<0.001). Finally, partners were significantly more likely to report worry about recurrence at four years after diagnosis than the survivors (42.3% vs. 27.2% p<0.001).

Table 1:

Characteristics of 510 Breast Cancer Survivors and their Partners 4 Years after Diagnosis

| Survivor N (%) | Partner N (%) | Paired P-Value* |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Total: | 510 (100) | 510 (100) | |

| Antecedent Factors | |||

| Personal Factors | |||

| Race | 0.086 | ||

| 2003Non-Hispanic White | 305 (59.8) | 313 (61.4) | |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 66 (12.9) | 68 (13.3) | |

| Latino (higher acculturation) | 71 (13.9) | 56 (11.0) | |

| Latino (lower acculturation) | 62 (12.2) | 67 (13.1) | |

| Age | <0.001 | ||

| Under 50 | 89 (17.5) | 70 (13.7) | |

| 50–65 | 263 (51.6) | 218 (42.7) | |

| 65 and over | 158 (31.0) | 222 (43.5) | |

| Education | 0.510 | ||

| High School Diploma or Less | 163 (32.0) | 156 (30.6) | |

| Some college or more | 347 (68.0) | 354 (69.4) | |

| Illness-Related Factors | |||

| Current Health | 0.437 | ||

| Good or better | 436 (85.5) | 424 (83.1) | |

| Fair or worse | 65 (12.7) | 72 (14.1) | |

| Comorbidities (at time 2) | 0.136 | ||

| 0 | 122 (23.9) | 104 (20.4) | |

| 1 or more | 388 (76.1) | 406 (79.6) | |

| Stage | _ | ||

| Stage 0 | 125 (24.5) | - | |

| Stage 1–2 | 338 (66.3) | - | |

| Stage 3 | 46 (9.0) | - | |

| Surgery type | _ | ||

| Lumpectomy | 324 (63.5) | - | |

| Unilateral mastectomy | 128 (25.1) | - | |

| Bilateral mastectomy | 51 (10.0) | - | |

| Radiation Therapy | _ | ||

| Yes | 363 (71.1) | - | |

| No | 135 (26.4) | - | |

| Chemotherapy | _ | ||

| Yes | 229 (44.9) | - | |

| No | 271 (53.1) | - | |

| Proximal Outcomes | |||

| Enough Info about Risk of Recurrence | 0.003 | ||

| Yes | 330 (64.7) | 363 (71.1) | |

| No | 171 (33.5) | 131 (25.7) | |

| Health Care Provider Emotional Support | <0.001 | ||

| None/ a little | 120 (23.5) | 263 (51.5) | |

| Some/ Quite a bit/ a lot | 383 (75.0) | 233 (45.7) | |

| Distal Outcomes | |||

| Worry about recurrence | <0.001 | ||

| No (Not at all/ a little) | 342 (67.0) | 252 (49.4) | |

| Yes (Some/quite a bit/ a lot) | 139 (27.2) | 216 (42.3) |

Paired Stuart-Maxwell Test.

Table 2 shows the percentage of survivors (partners) who reported worry within each subgroup defined by survivor (partner) characteristics. For survivors, the likelihood of worry was significantly higher among those with younger age, lower education levels or worse health status. Worry also differed significantly among racial/ethnical groups. Latinas-low were most likely to express worry (50%), compared with 36.5% for Latinas-high, 27.1% for whites and 14.0% for blacks. For partners, the likelihood of worry was significantly more likely among those who were less educated or had worse health themselves. Similar to survivors, partners worry differed among racial/ethnical groups. Latino partners reported the highest percentages of worry, with 67.2% and 66.7% for low and high acculturation groups, respectively, compared with 44.3% for whites and 27.1% for black partners. The likelihood of reported worry was similar among survivors irrespective of whether they received chemotherapy. However, partners of survivors who received chemotherapy were more likely to report worry than the partners of those who did not (56.3% vs. 40.0%, p<0.001). No other factors were significantly associated with worry for either survivors or partners.

Table 2:

Percent of Survivors and their Partners Reporting Worry about Recurrence, by Characteristic

| Characteristic | Survivors who worry N (%) |

Partners who worry N (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Overall | 132 (29.3) | 212 (47.1) |

| Personal Factors | ||

| Race | ||

| Non-Hispanic White | 74 (27.1)** | 124 (44.3)** |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 8 (14.0) | 16 (27.1) |

| Latino (higher acculturation) | 23 (36.5) | 32 (66.7) |

| Latino (lower acculturation) | 26 (50.0) | 39 (67.2) |

| Age in years | ||

| Under 50 | 30 (38.5)* | 32 (51.6) |

| 50–65 | 75 (31.0) | 99 (50.0) |

| 65 and over | 27 (20.8) | 81 (42.6) |

| Education | ||

| High School Diploma or Less | 51 (36.7)* | 69 (51.5)** |

| Some college or more | 81 (26.0) | 143 (45.2) |

| Illness-Related Factors † | ||

| Current Health | ||

| Good or better | 102 (26.4)** | 178 (47.0)** |

| Fair or worse | 27 (49.0) | 31 (50.0) |

| Comorbidities at time 2 | ||

| 0 | 28 (25.5) | 37 (39.3) |

| 1 or more | 104 (30.6) | 175 (49.1) |

| Stage | ||

| Stage 0 | 25 (22.9) | 45 (41.3) |

| Stage 1–2 | 97 (32.4) | 143 (47.8) |

| Stage 3 | 9 (22.0) | 24 (58.5) |

| Surgery type | ||

| Lumpectomy | 93 (31.6) | 133 (45.2) |

| Unilateral mastectomy | 31 (28.1) | 60 (54.5) |

| Bilateral mastectomy | 6 (14.6) | 17 (41.5) |

| Radiation Therapy | ||

| Yes | 98 (30.0) | 154 (47.2) |

| No | 29 (25.6) | 54 (47.7) |

| Chemotherapy | ||

| Yes | 64 (31.3) | 115 (56.3)** |

| No | 64 (27.0) | 95 (40.0) |

indicate that there is a significant association between worry about recurrence and the characteristic based on unadjusted logistic regression with * for p<0.05 and ** for p<0.01

Stage, surgery type, radiation, and chemotherapy are survivor’s characteristics.

Total = 450 pairs of survivors and their partners who have responded on questions about their worry about recurrence.

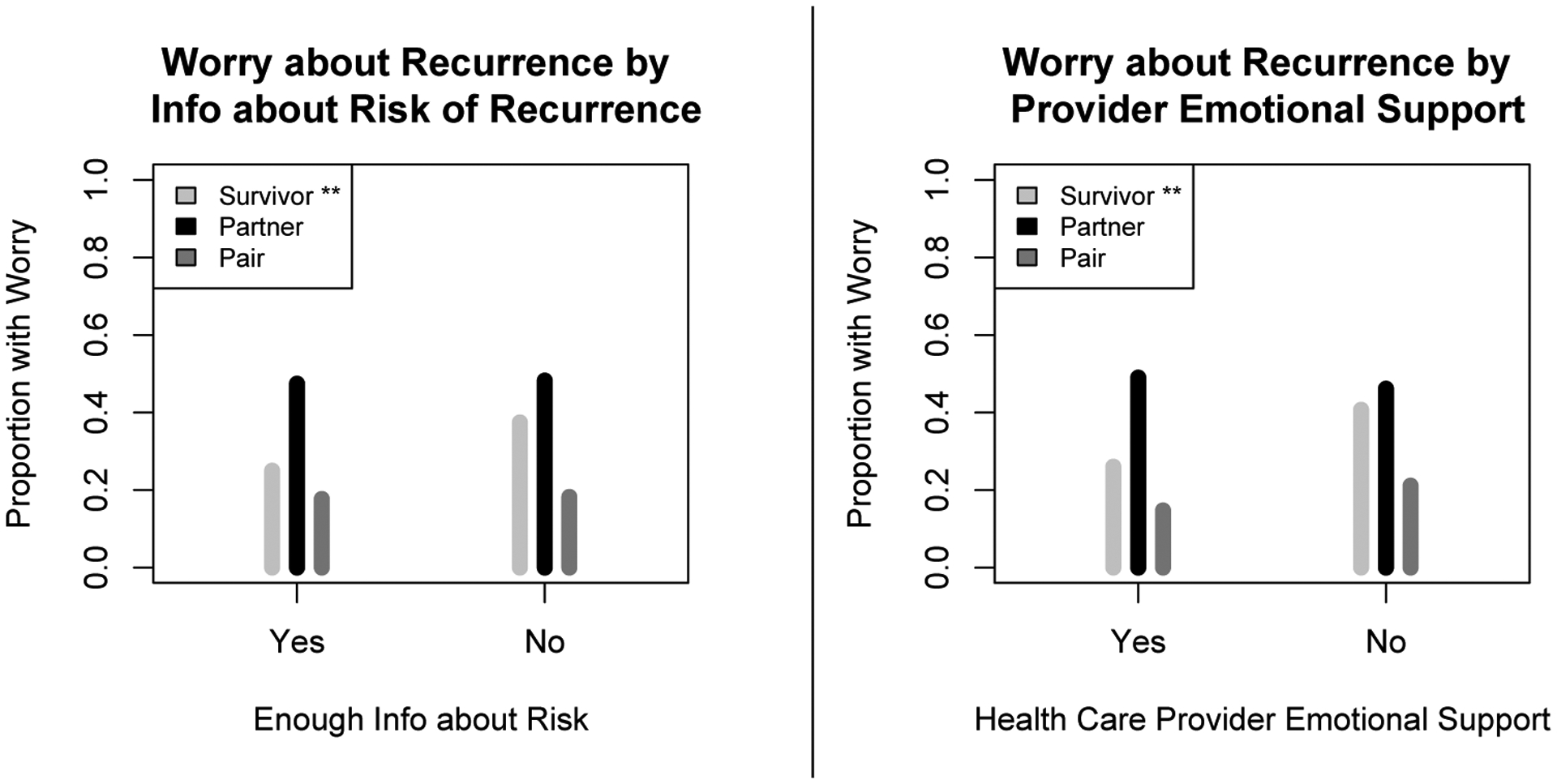

Figure 1 displays the relationship between worry of survivors/partners/pairs and receipt of information about risk of recurrence and receipt of emotional support from providers. The percentages of reported worry were consistently higher among the partners than the survivors. For survivors, without covariate adjustment, higher likelihood of worry was significantly associated with not having received enough information about the risk of recurrence (OR[95% CI] =1.82[1.18, 2.78]) or not having emotional support from providers (OR[95% CI] = 1.96[1.23, 2.78]). For either their partners or the pairs, the likelihood of worry was not associated with either of these outcomes.

Figure 1:

Survivor, Partner, and Pair Worry about Recurrence by Information received about risk and Emotional Support by Providers

** p<0.01 association between worry and proximal outcome based on unadjusted logistic regression.

Worry defined as some/quite a bit/a lot of worry about recurrence.

Table 3 presents the results from multivariable models for worry by survivors, partners and pairs. For survivors, with personal and illness-related factors in Model 1, race/ethnicity, age and current health status were found to be significantly associated with worry. Compared with whites, Latinas-low were significantly more likely to report worry (OR[95% CI] = 2.22 [1.01, 4.85]) while blacks were less likely (OR[95% CI] = 0.40 [0.16, 0.97]). Survivors with worse health were significantly more likely to report worry than their counterparts (OR[95% CI] = 2.31 [1.13, 4.69]). In Model 2, when proximal outcomes were added to Model 1, the previous factors remained significant. Additionally, survivors who received sufficient emotional support from providers were less likely to worry than those who did not receive such support (OR[95% CI] = 0.56 [0.32, 0.97]).

Table 3:

Multivariable Logistic Modeling of Survivor/Partner Worry at 4 Years

| Survivor Worry | Partner Worry | Pair Worry~ | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Survivor/Partner Characteristic | Model 1 OR |

Model 2 OR |

Model 3 OR |

Model 4 OR |

Model 5 OR |

Model 6 OR |

| Antecedent Factors | ||||||

| Personal Factors | ||||||

| Race | ||||||

| Non-Hispanic White (ref) | * | * | ** | ** | * | ** |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 0.40 | 0.40 | 0.54 | 0.53 | 0.23 | 0.24 |

| Latino (higher acculturation) | 1.62 | 1.63 | 2.67 | 3.05 | 1.97 | 2.43 |

| Latino (lower acculturation) | 2.22 | 1.85 | 3.02 | 2.96 | 2.17 | 1.95 |

| Age | ||||||

| Under 50 (ref) | * | * | ||||

| 50–65 | 0.44 | 0.45 | 1.15 | 1.17 | 0.74 | 0.67 |

| 65 and over | 0.31 | 0.36 | 1.02 | 1.16 | 0.48 | 0.52 |

| Education | ||||||

| High School Diploma or Less (ref) | ||||||

| Some college or more | 0.94 | 0.99 | 1.03 | 0.98 | 0.644 | 0.60 |

| Illness-Related Factors † | ||||||

| Current Health | ||||||

| Good or better (ref) | * | * | ** | * | ||

| Fair or worse | 2.31 | 2.23 | 1.03 | 1.10 | 2.89 | 2.58 |

| Comorbidities (at time 2) | ||||||

| 0 (ref) | ** | * | ||||

| 1 or more | 1.33 | 1.16 | 2.13 | 1.95 | 0.82 | 0.93 |

| Stage | ||||||

| Stage 0 (ref) | ||||||

| Stage 1–2 | 1.54 | 1.64 | 0.64 | 0.57 | 1.26 | 1.03 |

| Stage 3 | 0.65 | 0.73 | 0.52 | 0.42 | 0.51 | 0.35 |

| Surgery type | ||||||

| Lumpectomy (ref) | ||||||

| Unilateral mastectomy | 0.64 | 0.64 | 1.11 | 1.10 | 1.35 | 1.29 |

| Bilateral mastectomy | 0.31 | 0.30 | 0.88 | 0.83 | 0.75 | 0.78 |

| Radiation Therapy | ||||||

| No (ref) | ||||||

| Yes | 0.90 | 0.99 | 0.94 | 1.02 | 1.18 | 1.41 |

| Chemotherapy | ||||||

| No (ref) | ** | ** | ||||

| Yes | 0.87 | 0.90 | 2.47 | 2.77 | 1.23 | 1.76 |

| Proximal Outcomes | ||||||

| Enough Info about Risk of Recurrence | ||||||

| No (ref) | ||||||

| Yes | - | 0.65 | - | 0.80 | - | 1.22 |

| Emotional Support From Health Care | ||||||

| None/ A little (ref) | * | * | ||||

| Some/ Quite a bit/ A lot | - | 0.56 | - | 0.85 | - | 0.45 |

indicate that there is a significant association between worry about recurrence and the characteristic based on adjusted logistic regression with * for p<0.05 and ** for p<0.01

Bolded items denote characteristics that are significant compared to the reference category for characteristics that are significant overall with p<0.05

Stage, surgery type, radiation, and chemotherapy are survivor’s characteristics.

Using antecedent and illness-related factors of survivors.

For partners, Model 3 in Table 3 shows that Latinos were significantly more likely to report worry than whites (OR[95% CI]=3.02[1.41,6.47] for low acculturation and 2.67 [1.31,5.45] for high acculturation); while blacks were less likely to report worry than whites (OR[95%CI]=0.54 [0.27,1.06]). Partners with any comorbidity were more likely to report worry than those without (OR[95%CI] = 2.13[1.24,3.68]). Partners of survivors who had received chemotherapy were also more likely to report worry than their counterparts (OR[95%CI] = 2.47[1.45, 4.22]). With proximal outcomes added, Model 4 demonstrates the same significant factors associated with worry.

For pairs, Model 5 in Table 3 demonstrates that Latinos were more likely to report worry than whites (i.e., OR[95%CI] = 2.17 [0.95, 4.98] for Latinos-low, and OR[95%CI] = 1.97 [0.98, 3.97] for Latinos-high). In contrast, blacks were less likely to report worry than whites (OR[95%C] = 0.23[0.54, 1.04]). Furthermore, pairs with worse survivor health status were more likely to report worry than those who did not (OR[95%CI] = 2.89[1.36, 6.15]). Pairs who reported they received sufficient emotional support from providers were less likely to report worry than those who did not receive such support (OR[95%CI] = 0.45[0.23, 0.85]). When we repeated the analyses using the personal factors, illness-related factors and proximal outcomes of the partners as well as the cancer stage and treatment factors of the survivors, we found the same significant factors associated with worry about recurrence by the pairs.

Finally while not shown in Table 3, when we added partner worry to the survivor model we found that partner worry was a significant predictor of survivor worry (OR[95% CI]=2.12[1.29, 3.51]). Similarly, survivor worry contributed to the partner worry (OR[95% CI] = 2.05 [1.23, 3.40]).

Discussion

Our findings provide further support for the importance of viewing cancer as a family experience, where survivors and partners are both affected, and each affects the others’ worry and emotional response well into survivorship [5, 7, 11, 25, 26]. Partners reported more worry than survivors, possibly because they perceive less control, and receive less support than the survivor [5, 6]. In approximately 18% of pairs, both survivor and partner were worried about recurrence at four years, making them particularly vulnerable to the negative consequences of worry on behavior and emotional wellbeing [5, 10].

In this large diverse population-based sample of survivors and their partners, we found that Latinas/os were most vulnerable to worry. Possible explanations for the racial/ethnic differences include differences in the perceptions of the likelihood or consequences of cancer, cultural and contextual differences in coping with cancer [27], variation in willingness to report worry, and/or structural and language barriers in the health care system. In previous studies black survivors report fewer concerns and higher emotional well-being than whites [14]. In contrast, cultural factors such as cancer stigma, shame, and secrecy are often expressed by Latina survivors [28] and may contribute to worry. In terms of coping strategies among older adults, African Americans are most likely to rely on religious coping [29], and recent studies have shown that fatalism is often expressed by Latinos, irrespective of level of acculturation [30, 31]. Finally, low acculturated Latinas may be unfamiliar with the US health system and vulnerable to language barriers in patient-physician communication, particularly if discussing emotional issues through interpreters [28, 32, 33].

Consistent with previous studies [5, 11, 12], younger survivors and partners reported more worry. Younger couples facing cancer have more competing demands and fewer peers facing life-threatening illnesses [17]. Greater attention to symptom and comorbidity management may result in less worry, since studies show those who perceive their symptoms are well managed perceive less worry [12]. Survivors and partners with comorbid diseases are likely to have regular contact with their primary care provider (PCP), creating opportunities for PCPs to provide support and manage worry for these individuals [34]. PCPs are well positioned to provide emotional support as they play a more diverse role including preventive services, treatment of comorbidities and psychosocial care [35], and cancer patients seem open to PCPs assuming more responsibilities in follow-up care [36].

While survivors’ worry did not differ by treatment, partners whose spouse had chemotherapy were over twice as likely to report worry. Partners may need more information on the benefits of chemotherapy in reducing risk of recurrence to offset the visible side effects common to chemotherapy. Previous studies have identified added responsibilities, concerns and unmet information needs of partners of patients receiving chemotherapy [37, 38], and partners have expressed feelings of helplessness and being marginalized by the health care system in getting their information needs addressed [38].

This study explored whether modifiable factors related to the health care experience might be associated with worry by survivors, partners, or pairs. Among the two factors considered, the amount of emotional support received from providers was significantly related to worry among survivors and pairs. Most studies have focused on emotional support received by family or friends [11, 39] but our results suggest that support from providers should not be overlooked. In a recent study only about one-third of cancer patients recalled a discussion about the emotional impact of cancer with their health care professionals [40]. Our findings indicate there may be unmet need for emotional support from providers that could be directed at both survivors and partners.

Although this study did not find that receipt of sufficient information on risk of recurrence was a significant correlate of worry, previous studies suggest that survivors desire more information about recurrence than is generally provided [23]. Furthermore, survivors and partners may not understand the risk information that is communicated by physicians, particularly when English is not their first language [19, 23]. Actual recording of physician visits on mobile devices may provide survivors and partners an opportunity to later review clinic discussions on risk of recurrence.

Early intervention and/or referrals when necessary would likely alleviate persistent worry by survivors and partners. Interventions focused on psychoeducational, skill building, mindfulness training, finding meaning and benefit have shown promise with survivors [5, 30, 41] but need to be evaluated with partners and pairs. Support programs developed and led by professionals familiar with cultural norms is an important direction for clinical intervention [42]. Other directions include referral to social support services, culturally sensitive navigation programs, and consistent use of trained interpreters [33].

Limitations

This study was a cross-sectional examination of worry about recurrence among survivors, partners, and pairs four years after cancer diagnosis. Future research should examine worry longitudinally. Our measure of worry did not include the duration, frequency, and impact of distress on impairment [3]. However, the worry measure used for both survivors and partners was highly correlated with dimensions of QOL. Most measures were self-reported and may be subject to recall bias given the time delay between treatment and survey completion. While our study was guided by a stress/appraisal framework [20], the field would benefit from further testing of the theoretical underpinnings of worry about recurrence [5, 7, 43]. One of the major strengths of the study was the relatively large population-based sample with sufficient numbers of Latinos to examine acculturation. However, the US Hispanic population is diverse, so generalizability is limited to Latinos in our geographic location.

Conclusions

Our results underscore the need to consider survivors and partners as pairs and intervene with the couple as an emotional and interdependent unit to provide quality cancer care [7, 9]. We must focus on identifying pairs that are most vulnerable to persistent worry and target interventions to avoid the likelihood of poorer outcomes [10, 25, 43]. Future studies must include more racial, cultural and socioecomonic diversity, and broaden the definition of partners to include more same-sex couples. Theory-based interventions need to be developed and evaluated for survivors and partners that are culturally and linguistically tailored [30, 34]. Greater attention to modifiable risk factors to manage worry such as providers offering more emotional support is warranted. Interventions directed at cancer care and primary care providers are needed to raise their confidence in presenting risk of recurrence and managing worry in survivors and partners [44]. With survivorship care plans, there comes an opportunity to increase the support of patients and partners by improving communication between providers and with patients and partners about worry. [45]. Unfortunately, current SCP templates do not systematically contain this information. Given the scarcity of resources, interventions will need to be innovative, and incorporate technology as another vehicle to provide information and support [25, 41].

Acknowledgments:

We acknowledge the outstanding work of our project staff and Denise MacFarlin, Senior Secretary for Nancy Janz; these individuals received compensation for their assistance. We thank the American College of Surgeons Commission on Cancer and the National Cancer Institute Outcomes Branch for their support. We acknowledge with gratitude the breast cancer patients and partners who responded to our surveys.

Funding:

Supported by Grants No. R01 CA109696 and R01 CA088370 from the National Cancer Institute (NCI) to the University of Michigan. The collection of Los Angeles County cancer incidence data used in this study was supported by the California Department of Public Health as part of the statewide cancer reporting program mandated by California Health and Safety Code Section 103885; the NCI’s SEER program under Contract No. N01-PC-35139 awarded to the University of Southern California, Contract No. N01-PC-54404 awarded to the Public Health Institute; and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Program of Cancer Registries, under Agreement No. 1U58DP00807-01 awarded to the Public Health Institute. The collection of metropolitan Detroit cancer incidence data was supported by the NCI SEER program Contract No. N01-PC-35145. The partner study was supported by a grant from the University of Michigan Cancer Center Research Funds.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest:

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval:

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1963 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

References

- 1.Lee-Jones C, Humphris G, Dixon R, & Bebbington Hatcher M (1997) Fear of cancer recurrence – A literature review and proposed cognitive formulation to explain exacerbation of recurrence fears. Psychooncology 6:95–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van den Beuken-van Everdingen MH, Peters ML, de Rijke JM, Schouten HC, van Kleef M, Patijn J (2008) Concerns of former breast cancer patients about disease recurrence: A validation and prevalence study. Psychooncology 17:1137–1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vickberg SM (2003) The concerns about recurrence scale (CARS): A systematic measure of women’s fears about the possibility of breast cancer recurrence. Ann Behav Med 25:16–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kornblith AB, Powell M, Regan MM et al. (2007) Long-term psychosocial adjustment of older vs younger survivors of breast and endometrial cancer. Psychooncology 16:895–903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mellon S, Kershaw T, Northouse LL (2007) A family-based model to predict fear of recurrence for cancer survivors and their caregivers. Psychooncology 16:214–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Northouse LL, Mood DW, Montie JE et al. (2007) Living with prostate cancer: Patients’ and spouses’ psychosocial status and quality of life. J Clin Oncol 25(27):4171–4177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hagedoorn M, Sanderman R, Bolks HN et al. (2008) Distress in couples coping with cancer: A meta-analysis and critical review of role and gender effects. Psychol Bull 134:1–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hodges LJ, Humphris GM, Macfarlane G (2005) A meta-analytic investigation of the relationship between the psychological distress of cancer patients and their carers. Soc Sci Med 60:1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Northouse LL, Katapodi MC, Schafenacker AM, Weiss D (2012) The impact of caregiving on the psychological well-being of family caregivers and cancer patients. Semin Oncol Nurs 28(4):236–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Janz NK, Friese CR, Li Y, Graff JJ, Hamilton AS, Hawley ST (2014) Emotion well-being years post-treatment for breast cancer: prospective, multiethnic, and population-based analysis. J Cancer Surviv 8:131–142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mellon S, Northouse LL (2001) Family survivorship and quality of life following a cancer diagnosis. Res Nurs Health 24:446–459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Janz NK, Hawley ST, Mujahid MS et al. (2011) Correlates of worry about recurrence in a multiethnic population-based sample of women with breast cancer. Cancer 117(9):1827–1836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sammarco A, Konecny LM (2008) Quality of life, social support, and uncertainty among Latina breast cancer survivors. Oncol Nurs Forum 35:844–849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Janz NK, Mujahid M, Lantz PM et al. (2005) Population-based study of the relationship of treatment and sociodemographics on quality of life for early state breast cancer. Qual Life Res 14:1467–1479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim J, Yeob Han J, Shaw B, McTavish F, Gustafson D (2010) The roles of social support and coping strategies in predicting breast cancer patients’ emotional well-being. Testing mediation and moderation models. J Health Psychol 15(4):543–552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Forsythe LP, Alfano CM, Leach CR, Ganz PA, Stefanek ME, Rowland JH (2012) Who provides psychosocial follow-up care for post-treatment cancer survivors? A survey of medical oncologists and primary care physicians. J Clin Oncol 30(23):2897–2905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Janz NK, Mujahid M, Chung LK et al. (2007) Symptom experience and quality of life of women following breast cancer treatment. J Womens Health 16(9):1348–1361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Anema MG, Brown BE (1995) Increasing survey responses using the total design method. J Contin Educ Nurs 26:109–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lillie SE, Janz NK, Friese CR et al. (2014) Racial and ethnic variation in partner perspectives about the breast cancer treatment decision-making experience. Oncol Nurs Forum 41(1):13–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Northouse LL, Mood D, Hershaw T et al. (2002) Quality of life of women with recurrent breast cancer and their family members. J Clin Oncol. 20:4050–4064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marin G, Sabogal F, VanOss Marin B, Otero-Sabogal F, Perez-Stable EJ (1987) Development of a short acculturation scale for Hispanics. Hispanic J Behav Sci 9:183–205. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hamilton AS, Hofer TP, Hawley ST, Morrell D, Leventhal M, Deapen D (2009) Latinas and breast cancer outcomes: Population-based sampling, ethnic identity, and acculturation assessment. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 18:2022–2029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Janz NK, Mujahid NS, Hawley ST, Griggs JJ, Hamilton AS, Katz SJ (2008) Racial/ethnic differences in adequacy of information and support for women with breast cancer. Cancer 113(5):1058–1067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Charlson M, Szatroski TP, Peterson J, Gold J (1994) Validation of a combined comorbidity index. J Clin Epindemiol 47(11):1245–1251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Northouse L, Williams AL, Given B, McCorkle R (2012) Psychosocial care for family caregivers of patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol 20(11):1227–1234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim Y, Kashy DA, Wellisch DK, Spillers RL, Kwei Kaw C, Smith TG (2008) Quality of life of couples dealing with cancer: Dyadic and individual adjustment among breast and prostate cancer survivors and their spousal caregivers. Ann Behav Med 35:230–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Culver JL, Arena PL, Wimberly SR, Antoni MH, Carver CS (2004) Coping among African-American, Hispanic, and non-Hispanic White women recently treated for early stage breast cancer. Psychol Health 19(2):157–166. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Graves KD, Jensen RE, Canar J et al. (2012) Through the lens of culture: quality of life among Latina breast cancer survivors. Breast Cancer Res Treat 136:603–613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Krause N, Hayward RD (2012) Social factors in the church and positive religious coping responses: Assessing differences among older Whites, older Blacks, and older Mexican Americans. Rev Relig Res 54:519–541. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ramirez AS (2014) Fatalism and cancer risk knowledge among a sample of highly acculturated Latinas. J Cancer Educ 29:50–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Espinosa de los Monteros K, Gallo LC (2011) The relevance of fatalism in the study of Latinas’ cancer screening behavior: A systematic review of the literature. Int J Behav Med 18:310–318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ashing-Giwa KT, Padilla GV, Bohorquez DE, Tejero JS, Garcia M (2006) Understanding the breast cancer experience of Latina women. J Psychosoc Oncol 24(3):19–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lopez-Class M, Perret-Gentil M, Kreling B, Calcedo L, Mandelblatt J, Graves KD (2011) Quality of life among immigrant Latina breast cancer survivors: Realities of culture and enhancing cancer care. J Canc Educ 26:724–733 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bevans M, Sternberg E (2012) Caregiving burden, stress, and health effects among family caregivers of adult cancer patients. JAMA 307(4):398–403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pollack LA, Adamache W, Ryerson AB, Eheman CR, Richardson LC (2009) Care of long-term cancer survivors. Physicians seen by Medicare enrollees surviving longer than 5 years. Cancer 115(22):5284–5295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Roorda C, de Bock GH, Scholing C et al. (2014) Patients preferences for post-treatment breast cancer follow-up in primary care vs. secondary care: a qualitative study. Health Expect 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Iconomou G, Vagenakis AG, Kalofonos HP (2001) The informational needs, satisfaction with communication, and psychological status of primary caregivers of cancer patients receiving chemotherapy. Support Care Cancer 9:591–596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hilton BA, Crawford JA, Tarko MA (2000) Men’s perspectives on individual and family coping with their wives’ breast cancer and chemotherapy. Western J Nurs Res 22(4):438–459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu Y, Perez M, Schootman M, Aft RL, Gillanders WE, Jeffe DB (2011) Correlates of fear of cancer recurrence in women with ductal carcinoma in situ and early invasive breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 130:165–173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bonito A, Horowitz N, McCorkle R, Chagpar AB (2013) Do healthcare professionals discuss the emotional impact of cancer with patients? Psychooncology 22:2046–2050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Northouse LL, Katapodi MC, Song L et al. (2010) Interventions with family caregivers of cancer patients: meta-analysis of randomized trials. CA Cancer J Clin 60:317–339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Napoles AM, Santoyo-Olssori J, Ortiz C et al. (2014) Randomized controlled trial of Nuevo Amanecer: A peer-delivered stress management intervention for Spanish-speaking Latinas with breast cancer. Clin Trials 11:230–238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Simard S, Thewes B, Humphis G et al. (2013) Fear of cancer recurrence in adult cancer survivors: a systematic review of quantitative studies. J Cancer Surviv 7:300–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Janz NK, Leinberger RL, Zikmund-Fisher BJ, Hawley ST, Griffith K, Jagsi R (2015) Provider perspectives on presenting risk information and managing worry about recurrence among breast cancer survivors. Psychooncology 24(5):592–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lopez-Class M, Gomez-Duarte J, Graves K, Ashing-Giwa K (2012) A contextual approach to understanding breast cancer survivorship among Latinas. Psychooncology 21:115–124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]