Abstract

Background

Hypertension is a major source of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. Recent evidence from mouse models, genetic, and cross-sectional human studies suggest increased proportions of selected immune cell subsets may be associated with levels of systolic blood pressure (SBP).

Methods

We assayed immune cells from cryopreserved samples collected at the baseline examination (2000–2002) from 1195 participants from the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis (MESA). We used linear mixed models, with adjustment for age, sex, race/ethnicity, smoking, exercise, body mass index, education, diabetes, and cytomegalovirus titers, to estimate the associations between 30 immune cell subsets (4 of which were a priori hypotheses) and repeated measures of SBP (baseline and up to four follow-up measures) over 10 years. The analysis provides estimates of the association with blood pressure level.

Results

The mean age of the MESA participants at baseline was 64 ± 10 years and 53% were male. A one standard deviation (1-SD) increment in the proportion of γδ T cells was associated with 2.40 mmHg [95% confidence interval (CI) 1.34–3.42] higher average systolic blood pressure; and for natural killer cells, a 1-SD increment was associated with 1.88 mmHg (95% CI 0.82–2.94) higher average level of systolic blood pressure. A 1-SD increment in classical monocytes (CD14++CD16−) was associated with 2.01 mmHG (95% CI 0.79–3.24) lower average systolic blood pressure. There were no associations of CD4+ T helper cell subsets with average systolic blood pressure.

Conclusion

These findings suggest that the innate immune system plays a role in levels of SBP whereas there were no associations with adaptive immune cells.

Keywords: Lymphocytes, Innate immunity, Adaptive immunity, Systolic blood pressure, Cryopreserved cells, Longitudinal cohort study, Γδ T cells, Monocytes

Background

Hypertension is a major source of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in the United States [1, 2]. Major risk factors for hypertension include dietary sodium, physical inactivity, alcohol intake, and obesity [1]. While effective dietary and drug therapies exist to treat elevated blood pressure, our understanding of the biology and causes of hypertension remains incomplete.

Human and animal studies suggest that both the innate and adaptive immune system may be related to hypertension [3–7] although samples sizes have been limited. This link between immune cells and hypertension may help explain previous associations seen between immune cells and atherosclerosis. In a previous cross-sectional publication from the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) Exam 4 (2005–2007), fresh samples were assayed for lymphocyte subsets. Investigators found that naive and memory CD4+ T cells, and T helper type 1 (Th1) cells, analyzed as proportions of CD4+ cells, were associated with subclinical atherosclerosis [8, 9]. These fresh lymphocytes were from a subset of participants, at a later exam, and fewer white-cell subsets were measured in this prior study.

To investigate the links between immune cell subsets and cardiovascular disease (CVD), we used cryopreserved peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) to phenotype a range of immune cells by flow cytometry in the MESA cohort [10]. We leveraged the availability of this data for a secondary analysis of the relationships between 30 immune cell subsets and repeated SBP measures measured over 10-years. Based on prior findings [3–7] that some immune cell subsets were associated with blood pressure (primarily in mouse models), we hypothesized a priori that higher proportions of Th1, gamma delta (γδ) T cells, and Th17 cells would be associated with higher systolic blood pressure, and that higher proportions of regulatory T cells would be associated with lower systolic blood pressure [3, 7, 11, 12]. We included the other 26 immune cell subsets measured in MESA as secondary hypotheses, to understand broadly the relationship between the immune system and systolic blood pressure.

Methods

Study design

MESA is a community-based sample of 6814 men and women aged 45–84 years and recruited from 6 field centers (Baltimore, MD; Chicago, IL; Forsyth County, NC; Los Angeles County, CA; northern Manhattan, NY; and St. Paul, MN). Participants self-identified as White, Black, Hispanic, or Chinese. Exclusion criteria for the MESA cohort included a self-reported medical history of myocardial infarction, angina, cardiovascular procedures, heart failure, cerebrovascular disease, active treatment for cancer, pregnancy or amputation. Details regarding design, recruitment, and objectives of MESA are described elsewhere [13]. We designed a case-cohort study to test the primary hypothesis that immune cells subsets were risk factors for CHD [10]. We then leveraged the data from the case-cohort study to consider other scientific questions using the same study population [14]. We selected a case-cohort sample of 1195 participants, with case status (n = 476) based on incident myocardial infarction or incident angina events during study follow-up [10] with the remainder of the participants being selected by simple random sampling.

The original case cohort study of incident MI/angina was designed from the main MESA baseline cohort using cryopreserved cells stored at baseline (2000–2002) [10]. The original selection, n = 1200, was determined based on statistical power for the primary study [10]. Five of the selected participants had no sample in the repository. For the remaining 1195 participants, each sample was split into 6 assay panels as described in Additional file 2: Table S1. The number of cellular phenotypes measured per participant varied due to occasional poor sample quality of the individual PBMCs or technical errors. This was particularly true in the Th1, Th2, Th17 samples where a key reagent was incorrectly prepared for a portion of the participants, resulting in unreportable results. After finalizing the flow cytometry data, the number of participants with valid phenotypes varied from 770 to 1113. Since the sample quality and technical errors were assumed to be unrelated to participant characteristics in post-hoc analysis, we treated this data as missing at random.

Therefore, using weights derived from the case-cohort sampling to account for over-sampling of events, we included all participants with available data from this case-cohort study to investigate the associations of immune cell subsets with measures of systolic blood pressure over the course of the study. To be specific, we used MESA data from Exams 1–5 over 10 years of study follow-up, all of which included systolic blood pressure measures.

University of Washington IRB Committee J reviewed the MESA cohort study and approved it as FWA #00006878.

Data collection

At the baseline (2000–2002) and follow-up clinical visits (in 2002–2004, 2004–2005, 2005–2007, and 2010–2012) standardized questionnaires and calibrated devices were utilized to obtain data on demographics, tobacco use, medical conditions, prescription medication usage, weight, and height. PBMCs, used in this study, were collected at baseline. At each MESA exam, resting, seated blood pressure was measured 3 times using a Dinamap automated oscillometric sphygmomanometer (model Pro 100; Critikon, Tampa, Florida); the last 2 measurements were averaged for analysis. To adjust for hypertension treatment (33% of MESA participants were treated for hypertension at baseline), we added 10 mmHg to systolic blood pressure for treated participants, based on an approach that is widely used in genome-wide association studies (GWAS) [15, 16], although sometimes higher values are proposed for this correction [17].

Immune cell subsets

Detailed methods for immune cell phenotyping and flow cytometry gating strategies have been published [10] and specific antibodies utilized are shown in Additional file 2: Table S1. Briefly, as part of the baseline MESA exam, an 8 mL citrate CPT tube was drawn, PBMCs were collected, washed and frozen in freezing media containing 90% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 10% dimethyl sufoxide (DMSO) utilizing a controlled freezing rate. Cells (2 × 1 mL aliquots) were stored in a − 135 °C freezer until thawed. Cells (1 mL aliquot) were placed in a 37 °C water bath for 15 min until thawed. Cells were slowly diluted by addition of media with gentle mixing. For intracellular staining of CD4+ (Th1, Th2, Th17) and CD8+ (Tc1, Tc2, Tc17), cells were activated for 3 h at 37 °C with phorbal myristic acetate & ionomycin, and stained with live/dead stain. Cells were then surface labeled for CD4/CD8, fixed with paraformaldehyde and intracellularly stained for interferon gamma (IFN-γ), interleukin 4 (IL-4), and interleukin-17A (IL-17A) [10]. All other cellular phenotypes were surface labeled with antibodies as shown in Additional file 2: Table S1 and previously described [10]. Briefly, samples were centrifuged and placed into phosphate buffer saline at pH 7.4, then labeled with live/dead stain for 20 min. The stain was removed by centrifugation; cells were resuspended and labeled with specified cell surface markers for 20 min. Cells were washed, and fixed in paraformaldehyde, and stored in the dark at 4 °C prior to analysis on a MACSQuant 10 flow cytometer (Miltenyi Biotec, Germany), calibrated daily. Single color controls were used for compensation and isotype controls were used for negative gate setting. Results were analyzed using MacsQuantify software (Miltenyi Biotec). Gating strategies were previously reported [10].

Statistical analysis

Table 2 shows the immune cells analyzed, the markers used to identify these cells, the parent population, the number of valid measurements for each cell type and their means/standard deviations. All data is presented as a percent of the given parent population, which we treated as continuous variables for the purpose of analysis. Associations of immune cell subsets with systolic blood pressure were estimated relative to a one standard deviation (1-SD) difference in each of the cell proportions.

Table 2.

Cellular phenotypes with their molecular description, parent population, number of samples evaluated, means and standard deviations

| Cellular phenotype | Molecular description | Parent population | N | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary hypotheses | |||||

| Th1 | CD4+ IFN-γ+ | CD4+ | 770 | 15.3 | 9.0 |

| Th17 | CD4+ IL-17A+ | CD4+ | 770 | 2.1 | 1.4 |

| Tregs | CD4+ CD25+ CD127− | CD4+ | 1113 | 6.2 | 3.8 |

| γδ T cells | CD3+ γδ+ | CD3+ | 1087 | 6.6 | 6.1 |

| Exploratory hypotheses | |||||

| T cells | CD3+ | % Lymphocytes | 1087 | 62.7 | 13.7 |

| B cells | CD19+ | % Lymphocytes | 1087 | 11.3 | 7.4 |

| NK cells | CD3− CD56+ CD16+ | % Lymphocytes | 1087 | 5.0 | 5.7 |

| Classical monocytes | CD14++ CD16− | CD14 total | 922 | 74.4 | 10.2 |

| Intermediate monocytes | CD14+ CD16+ | CD14 total | 922 | 18.1 | 7.1 |

| Non-classical monocytes | CD14DimCD16+ | CD14 total | 922 | 7.4 | 7.5 |

| T helper cells | CD4+ | % Lymphocytes | 1051 | 50.0 | 11.0 |

| Th2 cells | CD4+ IL-4+ | CD4+ | 770 | 2.9 | 1.8 |

| Naive CD4+ cells | CD4+ CD45RA+ | CD4+ | 1051 | 26.2 | 12.1 |

| Memory CD4+ cells | CD4+ CD45RO+ | CD4+ | 1051 | 51.7 | 13.4 |

| CD28-senescent CD4 cells | CD4+ CD28− | CD4+ | 1051 | 13.9 | 10.0 |

| CD28-CD57+ senescent CD4 cells | CD4+ CD28− CD57+ | CD4+ | 1051 | 9.9 | 8.5 |

| CD4+ TEMRA | CD4+ CD45RA+ CD28− CD57+ | CD4+ | 1051 | 5.6 | 5.3 |

| Activated/mature CD4+ cells | CD4+ CD38+ | CD4+ | 1051 | 26.1 | 12.1 |

| CD57+ CD4+ cells | CD4+ CD57+ | CD4+ | 1051 | 22.4 | 13.0 |

| Cytotoxic T cells | CD8+ | % Lymphocytes | 1062 | 23.6 | 9.3 |

| Tc1 | CD8+ IFN-γ+ | CD8+ | 770 | 41.8 | 17.9 |

| Tc2 | CD8+ IL-4+ | CD8+ | 770 | 7.1 | 4.9 |

| Tc17 | CD8+ IL-17A+ | CD8+ | 770 | 5.4 | 5.8 |

| Naive CD8+ cells | CD8+ CD45RA+ | CD8+ | 1062 | 52.4 | 14.7 |

| Memory CD8+ cells | CD8+ CD45RO+ | CD8+ | 1062 | 21.7 | 10.6 |

| CD28-senescent CD8 cells | CD8+ CD28− | CD8+ | 1062 | 55.6 | 15.9 |

| CD28− CD57+ senescent CD8 cells | CD8+ CD28− CD57+ | CD8+ | 1062 | 44.5 | 15.9 |

| CD8+ TEMRA | CD8+ CD45RA+ CD28− CD57+ | CD8+ | 1062 | 32.8 | 14.3 |

| Activated/mature CD8+ cells | CD8+ CD38+ | CD8+ | 1062 | 23.6 | 12.2 |

| CD57+ CD8+ cells | CD8+ CD57+ | CD8+ | 1062 | 59.3 | 15.4 |

We used linear mixed models to evaluate the associations between immune cell subsets measured at MESA baseline and systolic blood pressure levels over 10 years, across five MESA exams. Models were adjusted for covariates measured at baseline that were thought to be possible confounders, including age, sex, race/ethnicity, smoking, exercise, body mass index (BMI), college education, diabetes, and log transformed cytomegalovirus antibody titer [8, 9]. Categorical variables with more than two levels were converted to indicator variables, two level categorical variables were included as indicator variables, and continuous variables included as linear adjustment variables, except for cytomegalovirus antibody titer which was log-transformed for skew. Immune-subset exposures were modeled singly, to avoid collinearity between the subsets and to maximize sample size, given that rates of missingness varied (Table 2).

These mixed models handled within-person correlation due to each subject having up to five systolic blood pressure measurements with subject-specific random intercepts. Inverse probability of sampling weights were used to account for the case-cohort sampling scheme. Confidence intervals used robust (sandwich) standard error estimates to ensure validity in the presence of the sampling weights. We examined the residuals of the linear regression model to determine whether the residuals were normally distributed and thus estimation using linear mixed models was appropriate. We used Bonferroni correction as our primary approach for controlling for multiple testing [18], despite the known correlations between the different immune cell subsets, some of which were high (making it overly conservative). The Bonferroni corrected p value threshold was 0.05/4 = 0.0125 for our primary hypotheses, and for our secondary hypotheses was 0.05/30 = 0.0017. Additionally, a false-discovery rate (FDR) approach [19] was implemented in a sensitivity analysis as an alternative to the overly conservative Bonferroni approach, which assumes independence of measures.

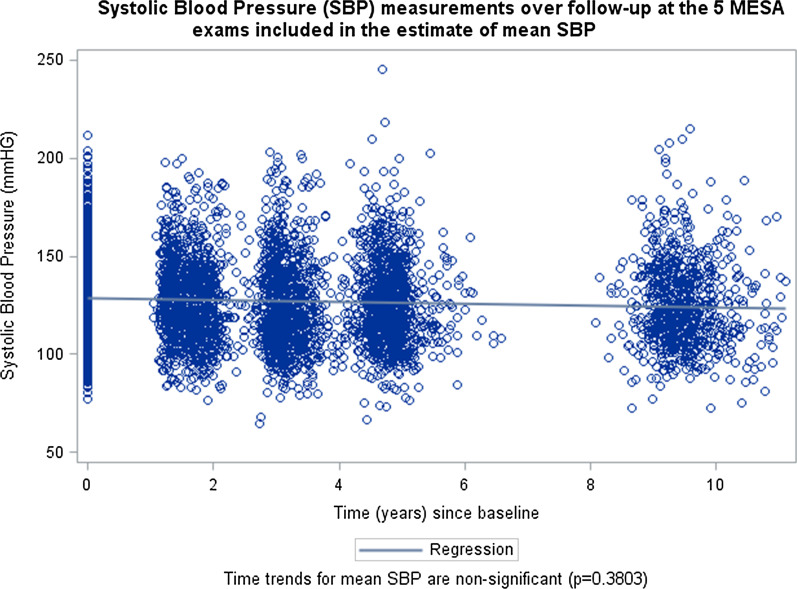

Primary analyses used all available data for each immune cell subset, under the assumption that missing data were missing completely at random. We included the SBP value at each of the five MESA exams as a repeated measure of blood pressure and thus estimates of association are with the average level of blood pressure, not with changes in blood pressure over time. Mixed models were used to handle irregular data sampling, differences in timing between measures, and the same participant contributing between one and five measures. Figure 1 shows the unadjusted blood pressure, with measures clustering around each of the follow-up time points (participant baseline is time zero by MESA study design). We tested for time trends, to ensure that we did not need to account for them in our model.

Fig. 1.

Systolic blood pressure (SBP) measurements over follow-up at the 5 MESA exams included in the estimate of mean SBP

We performed exploratory analysis for immune cell interactions by age, sex, race, and BMI for the primary hypotheses and any secondary hypothesis that was deemed significant after multiple testing correction. We tested for effect measure modification by antihypertensive medication use, using medication exposure as a time-varying covariate.

Results

The case-cohort study sample included 1195 MESA participants, with a mean (SD) age of 64 (± 10) years, and 53% of whom were male. The mean (SD) baseline systolic blood pressure was 130.0 mmHG (21.7 mmHg) at the Exam 1 baseline visit (Table 1). The average blood pressure at baseline and the subsequent follow-up exams can be seen in Fig. 1, and it does not show a statistically significant trend with time over study follow-up.

Table 1.

Characteristics of MESA subjects (n = 1087) with measures for γδ T cells, as a representative of a typical population in the study*

| Variable | Mean/number | Standard Deviation (SD)/percent |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years, SD) | 63.9 | 10.1 |

| Male (n, %) | 578 | 53% |

| Race/ethnicity (n, %) | ||

| White | 413 | 38% |

| Chinese | 135 | 12% |

| Black | 314 | 29% |

| Hispanic | 227 | 21% |

| Diabetes (n, %) | 184 | 17% |

| Smoker (n, %) | 144 | 13% |

| Alcohol user (n, %) | 557 | 64% |

| Statin user (n, %) | 191 | 18% |

| Calcium Channel Blocker user (n, %) | 159 | 15% |

| Diuretic user (n, %) | 173 | 16% |

| Beta Blocker user (n, %) | 110 | 10% |

| Vasodilator user (n, %) | 67 | 6% |

| ACE User (n, %) | 171 | 16% |

| College education (n, %) | 378 | 35% |

| Intentional Exercise (met-min/week, SD) | 1527 | 2293 |

| IL-6 (pg/mL, SD) | 1.64 | 1.24 |

| CMV antibody titer (EU/mL, SD) | 240 | 266 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHG, SD) | 130.0 | 21.7 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHG, SD) | 72.7 | 10.4 |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL, SD) | 193.9 | 35.8 |

| HDL Cholesterol (mg/dL, SD) | 49.4 | 14.4 |

| Body Mass Index (kg/m2, SD) | 28.3 | 5.4 |

All values were taken from participants at study baseline

The proportions of immune cell subsets and the number of participants contributing data to each are presented in Table 2. For example, γδ T cells averaged 6.6% of the total CD3+ cells measured. The numbers of participants with data on any particular immune cell phenotype ranged from 770 to 1113.

Of the four primary immune cell subsets that comprised our a priori hypotheses group (γδ T, Th1 (CD4+IFN-γ+), Th17 (CD4+IL-17A+), and Tregs (CD4+CD25+CD127−)), only γδ T cells were significantly associated with systolic blood pressure (Table 3). A one standard deviation (1-SD) increment in the proportion of γδ T cells was associated with a 2.40 mmHg [95% confidence interval (CI) 1.34–3.42] higher level of systolic blood pressure. This association was significant after Bonferroni correction.

Table 3.

Associations between lymphocyte subsets (per 1-SD) and average systolic blood pressure level (mmHG) across 10 years of follow-up

| ∆ mmHG (per SD) | 95% CI lower | 95% CI upper | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary hypotheses (significance threshold p < 0.0125) | ||||

| Th1 | 1.19 | − 0.41 | 2.79 | 0.15 |

| Th17 | − 0.06 | − 1.31 | 1.18 | 0.92 |

| Tregs | 1.09 | 0.05 | 2.13 | 0.04 |

| γδ T | 2.40 | 1.34 | 3.42 | < 0.0001 |

| Exploratory hypotheses (significance threshold p < 0.0017) | ||||

| T cells | − 1.22 | − 2.34 | − 0.09 | 0.03 |

| B cells | − 0.45 | − 1.6 | 0.7 | 0.44 |

| NK cells | 1.88 | 0.82 | 2.94 | 0.0005 |

| Classical monocytes | − 2.01 | − 3.24 | − 0.79 | 0.0013 |

| Intermediate monocytes | 0.98 | − 0.31 | 2.28 | 0.14 |

| Non-classical monocytes | 1.82 | 0.64 | 3.00 | 0.0025 |

| CD4+ | − 0.15 | − 1.19 | 0.89 | 0.78 |

| Th2 | − 0.14 | − 1.45 | 1.18 | 0.84 |

| Naïve CD4+ | 0.18 | − 0.97 | 1.34 | 0.76 |

| Memory CD4+ | 0.49 | − 0.68 | 1.65 | 0.41 |

| CD4+ CD28− | − 0.19 | − 1.34 | 0.96 | 0.75 |

| CD4+ CD28− CD57+ | − 0.04 | − 1.17 | 1.08 | 0.94 |

| CD4+ TEMRA | 0.45 | − 0.53 | 1.43 | 0.37 |

| CD4+ CD38+ | − 0.36 | − 1.51 | 0.80 | 0.54 |

| CD4+ CD57+ | 0.05 | − 1.07 | 1.17 | 0.93 |

| CD8+ | 0.11 | − 1.02 | 1.24 | 0.85 |

| Tc1 | 1.24 | − 0.11 | 2.59 | 0.07 |

| Tc2 | − 0.93 | − 2.21 | 0.34 | 0.15 |

| Tc17 | 0.49 | − 0.90 | 1.88 | 0.49 |

| Naïve CD8+ | 0.97 | − 0.15 | 2.09 | 0.09 |

| Memory CD8+ | − 1.02 | − 2.13 | 0.09 | 0.07 |

| CD8+ CD28− | 0.91 | − 0.28 | 2.09 | 0.13 |

| CD8+ CD28− CD57+ | 0.69 | − 0.46 | 1.84 | 0.24 |

| CD8+ TEMRA | 0.99 | − 0.13 | 2.12 | 0.08 |

| CD8+ CD38+ | 0.53 | − 0.58 | 1.64 | 0.35 |

| CD8+ CD57+ | 0.42 | − 0.67 | 1.52 | 0.45 |

Statistical models are linear mixed models using repeated blood pressure measures for MESA exams 1–5, and adjusted for baseline age, sex, race/ethnicity, smoking, exercise, body mass index, college education, diabetes, and log transformed CMV antibody titer

After adjusting for multiple comparisons, three other immune cell subsets, included in our exploratory secondary analyses, were also associated with systolic blood pressure; two were significant using a Bonferroni criteria (natural killer cells and classical monocytes), while using FDR added one additional immune cell subset (non-classical monocytes). A 1-SD increment in the proportion of natural killer cells was associated with a 1.88 mmHG (95% CI 0.82–2.94) higher level of systolic blood pressure during follow-up. The two other immune cell subsets associated with systolic blood pressure were both monocytes. A 1-SD increase in classical monocytes (characterized as CD14++CD16−) was associated with a 2.01 mmHG (95% CI 0.79–3.24) lower level of systolic blood pressure. While barely missing the Bonferroni threshold, a 1-SD increment in non-classical monocytes (characterized as CD14dimCD16++) was associated with a 1.82 mmHG (95% CI 0.64–3.00) higher level of systolic blood pressure. In sensitivity analyses, using a false discovery rate approach [19] instead of the Bonferroni approach (FDR cutoff for non-classical monocytes is 0.0068 versus an observed p-value of 0.0025), results for non-classical monocytes would also be considered statistically significant.

In further exploratory analyses, we looked for interaction of our main findings with sex, race, BMI, and age. The data, shown in the Additional file 2: Tables S2–S5, were null for all interactions, although some interactions had relatively large point estimates that were imprecise and could not exclude the null hypothesis. There was some limited evidence of effect modification for γδ T cells by the use of antihypertensive medications (p = 0.0203) (Table 4). For all of the other cell types, there was no statistically significant evidence of effect measure modification on the linear scale.

Table 4.

Stratification by anti-hypertensive medication use of the immune cell subsets with a statistically significant main effect to test for effect measure modification

| Immune cell subset | ∆ mmHG (per SD) | 95% CI | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any antihypertensive medication use (median SBP 131 mmHG) n = 1852 repeated SBP measures | ||||

| CD3+ γδ+ | 5.10 | 3.03 | 7.17 | < .0001 |

| CD3− CD56+ CD16+ | 2.25 | 1.06 | 3.45 | 0.0002 |

| CD14++ CD16− | − 2.02 | − 3.61 | − 0.43 | 0.0127 |

| CD14+ CD16+ | 1.16 | − 0.41 | 2.74 | 0.1475 |

| CD14DimCD16++ | 1.52 | 0.019 | 3.30 | 0.0472 |

| No antihypertensive medication use (median SBP 119.5 mmHG) n = 1928 repeated SBP measures | ||||

| CD3+ γδ+ | 1.33 | 0.22 | 2.45 | 0.0194 |

| CD3− CD56+ CD16+ | 0.76 | − 0.67 | 2.19 | 0.2997 |

| CD14++ CD16− | − 0.79 | − 2.22 | 0.63 | 0.2756 |

| CD14+ CD16+ | − 0.38 | − 1.76 | 1.00 | 0.5912 |

| CD14DimCD16++ | 1.56 | − 0.027 | 3.15 | 0.0540 |

Numbers refer to blood pressure readings under treatment, as each participant may contribute multiple measures and may change antihypertensive medication exposure category over follow-up. ∆ mmHG (per SD) refers to a change in the average level of SBP over 10 years of follow-up

Discussion

The main finding of this study is the association of γδ T cells, natural killer cells, and two monocyte populations with average systolic blood pressure during 10 years of measurement in a large multi-ethnic population. Three of these immune-cell subsets-γδ T cells, natural killer cells, and non-classical monocytes-are pro-inflammatory cells, which may suggest an association between innate immune cell-mediated inflammation and systolic blood pressure in a multi-ethnic cohort with no baseline cardiovascular disease.

One of our a priori hypotheses, the association between higher proportions of γδ T cells and higher systolic blood pressure replicates the association seen in Caillon et al. [3] and further builds evidence that these cells are involved in the development of human hypertension. γδ T cells respond rapidly in the initiation phase of immune reactions and act as a “bridge” between the innate and adaptive systems [20]. The current data are consistent with animal models of hypertension where γδ T cell receptor gene deletion or addition of inhibitory γδ T cell receptor antibodies blunted endothelial dysfunction and hypertension in an angiotensin II model of hypertension in mice [3]. γδ T cells produce the cytokine IL-17 that has been implicated in hypertension [6, 21–25]. When antibodies to IL-17 were administered in a mouse model of hypertension, hypertension was attenuated, renal and vascular cellular infiltration and proinflammatory proteins, such as TGF-β, were decreased [12, 24]. In the current study, we did not see an association of the IL-17 producing Th17 cells with systolic blood pressure, indicating the results seen previously indicating a role for IL17 may have been due to IL-17 production by γδ T cells or other IL17-producing cells.

In our exploratory analysis, we discovered an association between increased proportions of natural killer cells and levels of systolic blood pressure. Like γδ T cells, NK cells play a critical role in viral infection [20]. Natural killer cells are non-specific responders to bacterial or viral particles or infected cells and can produce IFN-γ and other cytokines that have been shown to be associated with hypertension [6, 21–26]. IFN-γ knockout mice were protected from angiotensin II induced vascular and kidney dysfunction [23]. In contrast, IFN-γ receptor knock out mice did not have the response to angiotensin II induced hypertension, although cardio-protective effects were noted [27]. While the current study does not show an association with the IFN-g producing adaptive immune cells (Th1, Tc1), the association of NK cells, which are a major source of IFN-γ, supports the role of IFN-γ in hypertension in humans.

Monocytes are an important component of the innate immune system and previous studies have implicated monocytes in atherosclerosis [28]. Monocytes have shown associations with blood pressure in several animal models [7, 29, 30] and these cells are related to both tissue remodeling in the vasculature as well as vascular inflammation [7]. Current anti-hypertensive medications (such as Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and Angiotensin II Receptor Blockers) can directly influence monocyte behavior, making it a plausible target for therapy [7]. The associations with systolic blood pressure observed here, with a shift from classical to the more pro-inflammatory non-classical monocytes, suggest a potential for further refinement of possible drug targets as well as a better understanding of the origins of hypertension. Notably, this may be an especially attractive line of research as monocytes are also thought to be involved in organ damage due to hypertension [7].

These data support other recent studies showing important links between the immune system and diseases, including both cardiovascular and kidney disease [31–33]. This includes evidence that the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio is a predictor of mortality and/or kidney dysfunction in older patients with hypertension [31, 32], although neither of these studies looked at antihypertensive medications. This makes the possible effect modification of γδ T cells with anti-hypertensive medication use observed in the current study of potential interest for designing prospective future studies with adequate power linking the immune system and hypertension for prediction. Finally, there is a clear advantage in being able to sub-type immune cells, as cruder approaches to classifying immune cells do not show significant differences between hypertensive and non-hypertensive participants [25].

The strengths of this study include the large sample size, the large panel of cell subsets evaluated and the long term, longitudinal measures of systolic blood pressure. The limitations include the observational nature of the data and technical issues with complex samples which resulted in some missing data. The use of cryopreserved PBMCs may result in different absolute levels of some of the subsets as compared with whole blood [25], although relative levels should be preserved [34]. Further, the immune cell distributions measured in this study from cryopreserved samples are similar to those previously measured in fresh whole blood obtained in MESA at Exam 4 (2005–2007) [8, 9] among phenotypes measured in both studies. Furthermore, participants treated with different anti-hypertensive medications may alter underlying biological relationships between some immune cell subsets and systolic blood pressure. Due to the variety of medications used in this cohort, we were not powered to see these relationships. It is also unknown how interventions on the immune cells will translate into therapeutic results; additional intervention studies will be required to allow translation of these results [35]. As a general correction for the direct effect of the medication, we added 10 mmHg to participants’ systolic blood pressure who were being treated [15–18], and any approach to accounting for medication use can have some measurement error.

Conclusions

In conclusion, this study provides evidence that γδ T cells, natural killer cells and classical and non-classical monocytes are associated with systolic blood pressure levels in a large multi-ethnic cohort. These data support previous animal studies that show a role for innate immune cells in affecting systolic blood pressure levels, and the consequent possibility of hypertension.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1. Sample SAS code used to build the dataset used in this analysis and the exact statistical models used.

Additional file 3. Sample MESA informed consent form.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the other investigators, the staff, and the participants of the MESA study for their valuable contributions. The authors thank Julia Valliere, Melissa Floersch and Brian Lynch for their technical effort. A full list of participating MESA investigators and institutions can be found at http://www.mesa-nhlbi.org.

Abbreviations

- 1-SD

One standard deviation

- BMI

Body mass index

- FDR

False-discovery rate

- MESA

Multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis

- PBMC

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells

- SBP

Systolic blood pressure

- Th1

T helper type 1

- Th2

T helper type 2

- Th17

T helper type 17

Authors’ contributions

JD, CS, NO, SAH, BP, RT and MD made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the work; BP, MD, and RT the made substantial contributions to acquisition of data; JD and CS made substantial contributions to analysis of data; JD, NO, CS, AF, SAH, AL SRH, RT, BP MF, and MD made substantial contributions to the interpretation of data; JD, NO, and MD drafted the work; and all authors contributed to revising the manuscript. All authors have approved the submitted version; all authors have agreed both to be personally accountable for the author's own contributions and to ensure that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work, even ones in which the author was not personally involved, are appropriately investigated, resolved, and the resolution documented in the literature. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The research reported in this article was supported by R00HL129045, R01HL120854, and R01HL135625. The MESA was supported by contracts HHSN268201500003I, N01-HC-95159, N01-HC-95160, N01-HC-95161, N01-HC-95162, N01-HC-95163, N01-HC-95164, N01-HC-95165, N01-HC-95166, N01-HC-95167, N01-HC-95168 and N01-HC-95169 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, and by grants UL1-TR-000040, UL1-TR-001079, and UL1-TR-001420 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS).

Availability of data and materials

The full MESA dataset can be requested from the Collaborative Health Studies Coordinating Center (CHSCC) upon approval of a paper proposal using this data. The instructions are at https://www.mesa-nhlbi.org/. MESA data is also available via BIOLINCC (https://biolincc.nhlbi.nih.gov/home/). The full code used to build the data sets and analyze the primary analysis is included as an Additional file 1 to this paper. The instruments and questionnaires given to the subjects are available at https://www.mesa-nhlbi.org/ex1forms.aspx#exam.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

University of Washington IRB Committee J reviewed the MESA cohort study and approved it as FWA #00006878. Participants were aware that samples may be used in research and that data may be published. A sample consent form from one of the clinical sites is included in the Additional file 3. Written consent for participation was obtained from all participants.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors report no potential conflicts of interest, including relevant financial interests, activities, relationships, and affiliations. Dr. Psaty serves on the Steering Committee of the Yale Open Data Access Project funded by Johnson & Johnson.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12872-021-01857-2.

References

- 1.Chen Y, Freedman ND, Albert PS, Huxley RR, Shiels MS, Withrow DR, Spillane S, Powell-Wiley TM, Berrington de González A. Association of cardiovascular disease with premature mortality in the United States. JAMA Cardiol. 2019;4(12):1230–1238. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2019.3891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bundy JD, Li C, Stuchlik P, Bu X, Kelly TN, Mills KT, He H, Chen J, Whelton PK, He J. Systolic blood pressure reduction and risk of cardiovascular disease and mortality: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. JAMA Cardiol. 2017;2(7):775–781. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2017.1421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Caillon A, Mian MO, Fraulob-Aquino JC, Huo KG, Barhoumi T, Ouerd S, Sinnaeve PR, Paradis P, Schiffrin EL. Gamma delta T cells mediate angiotensin ii-induced hypertension and vascular injury. Circulation. 2017;135(22):2155–2162. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.027058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carnevale D, Lembo G. Immunological aspects of hypertension. High Blood Press Cardiovasc Prev. 2016;23(2):91–95. doi: 10.1007/s40292-016-0141-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Crislip GR, Sullivan JC. T-cell involvement in sex differences in blood pressure control. Clin Sci (Lond) 2016;130(10):773–783. doi: 10.1042/CS20150620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Olofsson PS, Steinberg BE, Sobbi R, Cox MA, Ahmed MN, Oswald M, Szekeres F, Hanes WM, Introini A, Liu SF, Holodick NE, Rothstein TL, Lövdahl C, Chavan SS, Yang H, Pavlov VA, Broliden K, Andersson U, Diamond B, Miller EJ, Arner A, Gregersen PK, Backx PH, Mak TW, Tracey KJ. Blood pressure regulation by CD4+ lymphocytes expressing choline acetyltransferase. Nat Biotechnol. 2016;34(10):1066–1071. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wenzel U, Turner JE, Krebs C, Kurts C, Harrison DG, Ehmke H. Immune mechanisms in arterial hypertension. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;27(3):677–686. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2015050562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Olson NC, Doyle MF, Jenny NS, Huber SA, Psaty BM, Kronmal RA, Tracy RP. Decreased naive and increased memory CD4(+) T cells are associated with subclinical atherosclerosis: the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(8):e71498. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0071498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tracy RP, Doyle MF, Olson NC, Huber SA, Jenny NS, Sallam R, Psaty BM, Kronmal RA. T-helper type 1 bias in healthy people is associated with cytomegalovirus serology and atherosclerosis: the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. J Am Heart Assoc. 2013;2(3):e000117. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.113.000117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Olson NC, Sitlani CM, Doyle MF, Huber SA, Landay AL, Tracy RP, Psaty BM, Delaney JA. Innate and adaptive immune cell subsets as risk factors for coronary heart disease in two population-based cohorts. Atherosclerosis. 2020;300:47–53. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2020.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang J, Crowley SD. Role of T lymphocytes in hypertension. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2015;21:14–19. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2014.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Case AJ, Zimmerman MC. Sympathetic-mediated activation versus suppression of the immune system: consequences for hypertension. J Physiol. 2016;594(3):527–536. doi: 10.1113/JP271516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bild DE, Bluemke DA, Burke GL, Detrano R, Diez Roux AV, Folsom AR, Greenland P, Jacob DR, Jr, Kronmal R, Liu K, Nelson JC, O'Leary D, Saad MF, Shea S, Szklo M, Tracy RP. Multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis: objectives and design. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;156:871–881. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwf113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Olson NC, Doyle MF, Sitlani CM, de Boer IH, Rich SS, Huber SA, Landay AL, Tracy RP, Psaty BM, Delaney JA. Associations of innate and adaptive immune cell subsets with incident type 2 diabetes risk: the MESA study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2020;105(3):e848–e857. doi: 10.1210/clinem/dgaa036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cui JS, Hopper JL, Harrap SB. Antihypertensive treatments obscure familial contributions to blood pressure variation. Hypertension. 2003;41(2):207–210. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000044938.94050.E3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Levy D, Ehret GB, Rice K, Verwoert GC, Launer LJ, Dehghan A, Glazer NL, Morrison AC, Johnson AD, Aspelund T, Aulchenko Y, Lumley T, Köttgen A, Vasan RS, Rivadeneira F, Eiriksdottir G, Guo X, Arking DE, Mitchell GF, Mattace-Raso FU, Smith AV, Taylor K, Scharpf RB, Hwang SJ, Sijbrands EJ, Bis J, Harris TB, Ganesh SK, O'Donnell CJ, Hofman A, Rotter JI, Coresh J, Benjamin EJ, Uitterlinden AG, Heiss G, Fox CS, Witteman JC, Boerwinkle E, Wang TJ, Gudnason V, Larson MG, Chakravarti A, Psaty BM, van Duijn CM. Genome-wide association study of blood pressure and hypertension. Nat Genet. 2009;41(6):677–687. doi: 10.1038/ng.384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rao DC, Sung YJ, Winkler TW, Schwander K, Borecki I, Cupples LA, Gauderman WJ, Rice K, Munroe PB, Psaty BM. Multiancestry study of gene-lifestyle interactions for cardiovascular traits in 610 475 individuals from 124 cohorts: design and rationale. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2017;10(3):e001649. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.116.001649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gordon A, Glazko G, Qiu X, Yakovlev A. Control of the mean number of false discoveries, Bonferroni and stability of multiple testing. Ann Appl Stat. 2007;1:179–190. doi: 10.1214/07-AOAS102. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J R Stat Soc B. 1995;57(1):289–300. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Holtmeier W, Kabelitz D. Gamma delta T cells link innate and adaptive immune responses. Chem Immunol Allergy. 2005;86:151–183. doi: 10.1159/000086659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sesso HD, Jimenez MC, Wang L, Ridker PM, Buring JE, et al. Plasma inflammatory markers and the risk of developing hypertension in men. J Am Heart Assoc. 2015;4:e001802. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.115.001802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Anders HJ, Baumann M, Tripepi G, Mallamaci F. Immunity in arterial hypertension: associations or causalities? Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2015;30:1959–1964. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfv057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jekell A, Malmqvist K, Wallen NH, Mortsell D, Kahan T. Markers of inflammation, endothelial activation, and arterial stiffness in hypertensive heart disease and the effects of treatment: results from the SILVHIA study. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2013;62:559–566. doi: 10.1097/FJC.0000000000000017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mirhafez SR, Mohebati M, Feiz Disfani M, Saberi Karimian M, Ebrahimi M, et al. An imbalance in serum concentrations of inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines in hypertension. J Am Soc Hypertens. 2014;8:614–623. doi: 10.1016/j.jash.2014.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weinberg A, Song LY, Wilkening C, Sevin A, Blais B, et al. Optimization and limitations of use of cryopreserved peripheral blood mononuclear cells for functional and phenotypic T-cell characterization. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2009;16:1176–1186. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00342-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cornelius DC, Hogg JP, Scott J, Wallace K, Herse F, et al. Administration of interleukin-17 soluble receptor C suppresses TH17 cells, oxidative stress, and hypertension in response to placental ischemia during pregnancy. Hypertension. 2009;62:1068–1073. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.113.01514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Marko L, Kvakan H, Park JK, Qadri F, Spallek B, et al. Interferon-gamma signaling inhibition ameliorates angiotensin II-induced cardiac damage. Hypertension. 2012;60:1430–1436. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.112.199265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Libby P, Nahrendorf M, Swirski FK. Monocyte heterogeneity in cardiovascular disease. Semin Immunopathol. 2013;35(5):553–562. doi: 10.1007/s00281-013-0387-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Caillon A, Paradis P, Schiffrin EL. Role of immune cells in hypertension. Br J Pharmacol. 2019;176(12):1818–1828. doi: 10.1111/bph.14427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.De Ciuceis C, Amiri F, Brassard P, Endemann DH, Touyz RM, Schiffrin EL. Reduced vascular remodeling, endothelial dysfunction, and oxidative stress in resistance arteries of angiotensin II-infused macrophage colony-stimulating factor-deficient mice: evidence for a role in inflammation in angiotensin-induced vascular injury. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2005;25:2106–2113. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000181743.28028.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sun X, Luo L, Zhao X, Ye P, Du R. The neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio on admission is a good predictor for all-cause mortality in hypertensive patients over 80 years of age. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2017;17(1):167. doi: 10.1186/s12872-017-0595-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen C, Zhao HY, Zhang YH. Correlation between neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio and kidney dysfunction in undiagnosed hypertensive population from general health checkup. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2020;22(1):47–56. doi: 10.1111/jch.13749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Usta Atmaca H, Akbas F, Aral H. Relationship between circulating microparticles and hypertension and other cardiac disease biomarkers in the elderly. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2019;19(1):164. doi: 10.1186/s12872-019-1148-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thyagarajan B, Barcelo H, Crimmins E, Weir D, Minnerath S, Vivek S, Faul J. Effect of delayed cell processing and cryopreservation on immunophenotyping in multicenter population studies. J Immunol Methods. 2018;463:61–70. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2018.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Olson NC, Sallam R, Doyle MF, Tracy RP, Huber SA. T helper cell polarization in healthy people: implications for cardiovascular disease. J Cardiovasc Transl Res. 2013;6:772–786. doi: 10.1007/s12265-013-9496-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1. Sample SAS code used to build the dataset used in this analysis and the exact statistical models used.

Additional file 3. Sample MESA informed consent form.

Data Availability Statement

The full MESA dataset can be requested from the Collaborative Health Studies Coordinating Center (CHSCC) upon approval of a paper proposal using this data. The instructions are at https://www.mesa-nhlbi.org/. MESA data is also available via BIOLINCC (https://biolincc.nhlbi.nih.gov/home/). The full code used to build the data sets and analyze the primary analysis is included as an Additional file 1 to this paper. The instruments and questionnaires given to the subjects are available at https://www.mesa-nhlbi.org/ex1forms.aspx#exam.