Abstract

Introduction

Under the US Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has the authority to implement graphic warning labels (GWLs) on cigarette packages. Neither the original labels proposed by the FDA nor the revised labels include a source to indicate sponsorship of the warnings. This study tests the potential impact of adding a sponsor to the content of GWLs.

Methods

We recruited adult smokers (N = 245) and middle-school youth (N = 242) from low-income areas in the Northeastern US. We randomly assigned participants to view one of three versions of the original FDA–proposed warning labels in a between-subjects experiment: no sponsor, “US Food and Drug Administration,” or “American Cancer Society” sponsor. We tested the effect of varying sponsorship on source attribution and source credibility.

Results

Compared to unsponsored labels, FDA sponsorship increased source attributions that the FDA sponsored the labels among both middle-school, largely nonsmoking youth and adult smokers. However, sponsorship had no effect on source credibility among either population.

Conclusions

We found no evidence that adding FDA as the source is likely to boost source credibility judgments, at least in the short term; though doing so would not appear to have adverse effects on credibility judgments. As such, our data are largely consistent with the Tobacco Control Act’s provisions that allow, but do not require, FDA sponsorship on the labels.

Implications

This study addresses the FDA’s regulatory efforts by informing the possible design and content of future cigarette warning labels. Our results do not offer compelling evidence that adding the FDA name on GWLs will directly increase source credibility. Future work may test more explicit FDA source labeling and continue to examine the credibility of tobacco message content among high–priority populations.

Introduction

The US Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act (TCA) grants the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) regulatory authority to implement warning labels on cigarette packages. After the FDA initially proposed nine graphic warning labels (GWLs) to appear atop cigarette packages, a federal appeals court ruled in 2012 that the FDA–proposed labels violated tobacco companies’ free speech rights.1 The FDA chose not to further appeal the decision and in summer 2019 proposed a new set of 13 labels informed by additional research. In March 2020, the FDA issued a final rule, effective June 18, 2021 requiring 11 of these labels.2

Unlike the current US Surgeon General warnings, neither the original nine labels nor the latest 13 labels identify a source. Given low public awareness that the FDA regulates tobacco products, it is unclear how the public would respond to sponsor information on the warnings.3,4 An important consideration is whether the public would correctly attribute the source in the presence of a sponsored endorsement. It is further important to examine source credibility perceptions, as high–credibility sources can enhance favorable responses to health messages.5,6

Trusted and familiar public health sponsor endorsements can function as heuristic cues to enhance credibility and elicit more positive cognitive reactions to anti–tobacco messaging. These reactions may increase trust and agreement with anti–tobacco messages and in turn increase intentions to quit among adult smokers or to avoid initiation among youth.7 In contrast, low–credibility sources, such as tobacco companies conveying health information themselves, may undermine message effectiveness.6

While research underscores the importance of identifying source judgments when people evaluate risk messages,7 FDA’s credibility as a tobacco communicator is mixed. Current evidence suggests the FDA is perceived as moderately trustworthy when communicating tobacco health risks among individuals familiar with its regulatory role.8,9 One experiment found that including the FDA logo on anti–tobacco messages increased source credibility perceptions relative to messages without a source.10 Another set of experiments manipulating tobacco warning sources via phone surveys found that identifying the FDA (vs. other public health sources, or no source) had no effects on content believability.11–13 These mixed findings call for more research to examine whether adding an FDA endorsement to GWLs may boost credibility judgments.

To this end, we conducted two randomized experiments among priority populations identified by the TCA—one among low socioeconomic status (SES) adult smokers and another among youth at risk of smoking—to test whether adding the FDA endorsement to GWLs increases correct source attributions and strengthens source credibility perceptions. The experiments focused on two critical populations in the US tobacco context since lower-SES adults face disproportionately higher smoking rates and related burden, and youth from lower-SES backgrounds are more likely to uptake smoking, relative to higher-SES groups.14,15

In a between-subject design, participants viewed unsponsored labels, labels with the FDA endorsement, or labels with an American Cancer Society (ACS) endorsement. We selected the ACS as a relatively familiar and trusted public health organization in comparison to the FDA that is not part of the US government.6 We hypothesized that adding the FDA endorsement on GWLs would increase correct source attribution that FDA sponsors the labels among adult smokers and youth (H1). Further, we hypothesized that labels with a sponsored endorsement (FDA or ACS) would elicit stronger source credibility perceptions compared to labels without a sponsor among both samples (H2).

Methods

Recruitment

Cornell University’s Institutional Review Board approved all recruitment processes and experimental procedures. Using a mobile research laboratory vehicle, we recruited adult smokers (N = 245) from rural and urban areas in the Northeast with an average household income of $35 000 or less and middle-school youth (N = 242) from schools with 40–100% of students receiving free or reduced-price lunch (see Supplementary Appendix for details).

Procedure

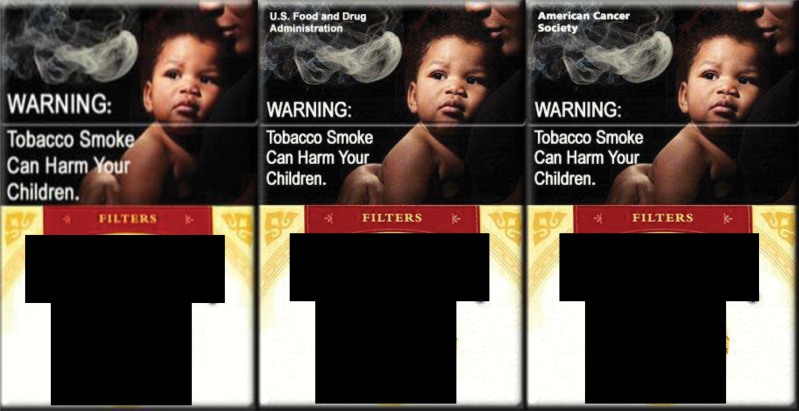

We conducted the current study as part of a series of several randomized experiments testing the effects of warning label attributes. Data collection procedures were similar to those employed in previous work.16,17 Participants viewed a set of nine cigarette pack images, featuring each of the original FDA–proposed GWLs. We manipulated sponsor information to generate three between-subject conditions: no sponsor information (consistent with the original FDA–proposed labels), “FDA,” or “ACS” (see Figure 1). After viewing the images, participants completed a survey assessing who they believed put the warning labels on the packs, source credibility perceptions, and demographics.

Figure 1.

Sample images from the three experimental conditions. We randomized three cigarette brands (Camel, Marlboro, and Newport) across cigarette pack images so that brands would not be confounded with the nine labels. Placement of the sponsor name depended on the design of the proposed label and the judgment of the professional graphic designer who produced the modified warnings. Cigarette brand imagery redacted for publication. Photography and graphic design credit: L. Scolere.

Measures

Source Attribution

For both populations, we measured source attribution with one item: “Thinking about the warnings you saw, who do you think put them on the boxes?” Response options were US Food and Drug Administration, American Cancer Society, Surgeon General, Health America (a fictitious organization, modeled after Health Canada), American Heart Association, a cigarette company, an e-cigarette/vaping company, and a nicotine gum company.

Source Credibility

For adults, a six-item scale measured perceived source credibility:6,18 “The people who put the warnings on the cigarette packs…(response options: are not/might be/definitely are) …experts, …smart, …trustworthy, …honest” and “The people who put the warnings on the cigarette packs…(response options: do not/might/definitely)…care about me, …understand me.” For youth, we used a shorter three-item scale: “The people who put the warnings on the cigarette packs…(response options: do not/might/definitely)…know what they are talking about, …care about me, (response options: are not/might be/definitely are)…trustworthy.” We averaged ratings into three-point credibility scales (Madults = 2.32, SDadults = .54, Cronbach’s α adults = .86; Myouth = 2.49, SDyouth = .58, α youth = .81).

Analytic Approach

We used SPSS version 20 and R version 3.6.1 for analyses. To test H1, which predicted that adding the FDA endorsement on GWLs would increase correct source attributions that FDA sponsors the labels, we conducted χ2 tests of independence with pairwise comparisons for youth and adults (in separate models). To test H2, which predicted that labels with a sponsored endorsement (FDA or ACS) would elicit stronger source credibility perceptions compared to labels without a sponsor, we conducted linear regressions for each sample with the no-sponsor condition as the reference group. We included age, gender, and race as covariates. For adults, we also included education, trust in government, income, and being part of a welfare program in the model. For youth, we also controlled for having tried cigarettes and living with a smoker. We repeated the same regressions with the FDA as a reference group to examine source credibility differences between the FDA and ACS for both samples.

Results

Sample

The average adult age was M = 43.3 years (SD = 14.3), and the average youth age was M = 12.7 years (SD = 1.1). Roughly half of participants (adults = 50%, youth = 47%) identified as male. The racial and ethnic breakdown of adults (via nonexclusive categories) was 55% White, 40% African American, 6% Hispanic/Latino/a/x, with 8% choosing an other-race category. The racial and ethnic distribution was similar for youth (62% White, 31% African American, 6% Hispanic/Latino/a/x, and 17% other). Roughly 7% of adults reported having a college degree, and about 69% reported a yearly household income of <$20K. Most adults (80%) reported receiving benefits from at least one welfare program or being food insecure in the last year. Forty-one percent of youth reported living with a smoker, and 12% reported previously trying cigarettes.

Source Attributions (H1)

There were significant differences in source attributions that the FDA sponsors the labels by condition among adults, X2(2, N = 242) = 8.63, p = .01, Cramer’s V = .19, and among youth, X2(2, N = 238) = 15.4, p < .001, Cramer’s V = .26 (see Table 1 for percentage differences by condition). For both populations, participants in the FDA condition were significantly more likely to choose the FDA as a source compared with participants in the other two conditions, supporting H1. Although not specifically hypothesized, we note no differences in adults’ attributions of the labels to the ACS across the conditions, X2(2, N = 242) = 2.62, p = .27, Cramer’s V = .10). While there were differences with regard to youth selecting ACS X2(2, N = 238) = 14.0, p = .001, Cramer’s V = .24, pairwise comparisons suggest no differences in ACS attribution between participants in the ACS condition and participants in the control condition.

Table 1.

Percentages and means across conditions

| Source attribution | Adult smokers | Nonsmoking youth | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control (n = 81) |

FDA (n = 82) |

ACS (n = 82) |

Control (n = 80) |

FDA (n = 81) |

ACS (n = 81) |

|

| FDA, % | 5b | 17bc | 6c | 16d | 34de | 10e |

| ACS, % | 19 | 11 | 20 | 20f | 8fg | 31g |

| Surgeon General, % | 54 | 49 | 52 | 8 | 6 | 9 |

| AHA, % | 4 | 9 | 6 | 5 | 1 | 9 |

| A cigarette company, % | 16 | 9 | 10 | 20 | 14 | 20 |

| An e-cigarette company, % | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 0 |

| A nicotine gum company, % | 1 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 2 |

| Health America, % | 1 | 4 | 6 | 27 | 32 | 19 |

| Source credibility |

M = 2.31 (SD = .53) |

M = 2.34 (SD = .52) | M = 2.31 (SD = .59) | M = 2.46 (SD = .63) | M = 2.48 (SD = .56) | M = 2.52 (SD = .55) |

A shared superscript denotes a significant difference at p < .05. FDA = Food and Drug Administration, ACS = American Cancer Society, AHA = American Heart Association. Credibility was measured on a 3-point scale. Table shows valid percentages and means (cases with nonmissing data for each variable).

Source Credibility (H2)

Among adults, viewing labels with FDA endorsement (unstandardized b = .02, p = .78) and labels with ACS endorsement (unstandardized b = −.02, p = .81) did not influence source credibility relative to viewing unsponsored labels (F = 1.646, df = 210, R2 = .14). Similarly, neither exposure to FDA labels (unstandardized b = .02, p = .83) nor ACS labels (unstandardized b = .03, p = .72) affected youth’s credibility perceptions compared to control, unsponsored labels (F = 1.052, df = 211, R2 = .10). We thus reject H2. Post hoc analyses found no significant differences in adult and youth credibility beliefs between the ACS and FDA conditions (adults: b = −.05, p = .60; youth: b = .01, p = .89).

Discussion and Conclusions

This study found that including the FDA name as the source of warning labels on GWLs did not increase source credibility perceptions among adult smokers and primarily nonsmoking youth in the short term. These null findings on credibility align with several previous studies showing that FDA sponsorship had no effects on warning believability among adolescents,11,13 adults,12 or adult smokers.13 However, including the FDA name on GWLs did increase source attributions that the FDA sponsored the labels among both smoking adults and youth. Source attribution effects were small in magnitude (Cramer’s V from .19 to .26), perhaps reflecting limitations of a single session of exposure to a set of nine GWLs that were never circulated.

To address the question of whether GWLs in the US should mention the FDA as the sponsor, we further consider observed patterns of source attribution. Most adult smokers who viewed unsponsored labels (54%) believed the Surgeon General was the sponsor. Even when the labels included the FDA or ACS name as a sponsored endorsement, smokers still tended to attribute the labels to the Surgeon General (FDA condition = 49%, ACS condition = 52%). Smokers may be accustomed to the existing, side-of-pack labels sponsored by the Surgeon General. The idea that smokers are anchored to beliefs that the Surgeon General sponsors all warning labels—and anti-tobacco campaigns more broadly—may explain why previous studies have found that only a small number of smokers exposed to FDA–sponsored anti-tobacco messages successfully recall the FDA as the source.19 It may also suggest that repeated exposure to FDA–sponsored packs would be necessary for most smokers to attribute sponsorship to the FDA. In addition, it may be necessary to more explicitly identify the FDA as a source (eg, “FDA WARNING”) rather than simply mentioning the organization.

Youth have presumably had less exposure to the current Surgeon General–sponsored labels, so when it comes to shaping beliefs about label sponsorship, nonsmoking youth may be more malleable than current smokers. The extent to which the FDA would be deemed a credible source among youth, however, remains uncertain, as the FDA–sponsored label did not generate greater source credibility perceptions among youth. Thus, we offer no evidence here to suggest that adding the FDA name on GWLs is likely to increase the credibility of these labels among youth—even if they attribute the warning labels to the FDA itself.

We wish to acknowledge a few limitations. We purposefully recruited participants with low SES, so we cannot make claims about whether our findings will hold for higher socioeconomic groups. Our measure of source attribution included response options of varying specificity (“ACS” vs. “a cigarette company”), which may have introduced bias in reports of source attribution. Additionally, we cannot comment on sponsorship effects on long-term smoking behavior or whether repeated exposure to FDA–sponsored labels would influence credibility beliefs.7 There were small sample sizes for sources that were infrequently attributed as responsible for the warnings, reducing confidence in those estimates. Relatedly, statistical power was inadequate to detect small but potentially meaningful differences on outcomes such as attribution of the warning labels to cigarette companies. Future studies may test more explicit source labeling and the credibility of other tobacco message content features beyond source labeling among low-income populations.20

In summary, we found no evidence that adding the FDA name as the source of graphic cigarette warning labels is likely to enhance source credibility judgments—at least in the short term—though doing so would not appear to have adverse effects on credibility judgments. As such, our data are largely consistent with the TCA’s provisions that allow, but do not require, FDA sponsorship on the labels.

Supplementary Material

A Contributorship Form detailing each author’s specific involvement with this content, as well as any supplementary data, are available online at https://academic.oup.com/ntr.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) and FDA Center for Tobacco Products (CTP; grant number 1R01-1HD079612). The funders played no role in: the study design; collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; the writing of the manuscript; or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or the Food and Drug Administration.

Declaration of Interests

None declared.

References

- 1. RJ Reynolds Tobacco Company, et al. , vs. Food and Drug Administration et al, 696 F.3d 1205 (D.C. Cir. 2012). www.leagle.com/decision/infco20120824144. Accessed November 12, 2019.

- 2. Tobacco Products. Required Warnings for Cigarette Packages and Advertisements, 85 FR 15638, 21 CFR 1141. www.federalregister.gov/documents/2020/03/18/2020–05223/tobacco-products-required-warnings-for-cigarette-packages-and-advertisements. Published March 18, 2020. Accessed March 23, 2020.

- 3. Kaufman AR, Finney Rutten LJ, Parascandola M, Blake KD, Augustson EM. Food and drug administration tobacco regulation and product judgments. Am J Prev Med. 2015;48(4):445–451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Jarman KL, Ranney LM, Baker HM, Vallejos QM, Goldstein AO. Perceptions of the food and drug administration as a tobacco regulator. Tob Regul Sci. 2017;3(2):239–247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Pornpitakpan C. The persuasiveness of source credibility: a critical review of five decades’ evidence. J Appl Soc Psychol. 2004;34:243–281. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Byrne S, Guillory JE, Mathios AD, Avery RJ, Hart PS. The unintended consequences of disclosure: effect of manipulating sponsor identification on the perceived credibility and effectiveness of smoking cessation advertisements. J Health Commun. 2012;17(10):1119–1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Schmidt AM, Ranney LM, Pepper JK, Goldstein AO. Source credibility in tobacco control messaging. Tob Regul Sci. 2016;2(1):31–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Boynton MH, Agans RP, Bowling JM, et al. Understanding how perceptions of tobacco constituents and the FDA relate to effective and credible tobacco risk messaging: a national phone survey of U.S. adults, 2014-2015. BMC Public Health. 2016;16:516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kowitt SD, Schmidt AM, Hannan A, Goldstein AO. Awareness and trust of the FDA and CDC: results from a national sample of US adults and adolescents. PLoS One. 2017;12(5):e0177546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kowitt S, Sheeran P, Jarman K, et al. Cigarette constituent health communications for smokers: Impact of chemical, imagery, and source. Nicotine Tob Res. 2017;21(6):841–845. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntx226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kowitt SD, Jarman K, Ranney LM, Goldstein AO. Believability of cigar warning labels among adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 2017;60:299–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Jarman KL, Kowitt SD, Cornacchione RJ, Goldstein AO. Are some of the cigar warnings mandated in the U.S. more believable than others? Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2017;14:1370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lazard AJ, Kowitt SD, Huang LL, Noar SM, Jarman KL, Goldstein AO. Believability of cigarette warnings about addiction: National experiments of adolescents and adults. Nicotine Tob Res. 2018;20(7):867–875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Department of Health and Human Services. The Health Consequences of Smoking: 50 Years of Progress. A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, Georgia: Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health: Washington, DC; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Scarinci IC, Robinson LA, Alfano CM, Zbikowski SM, Klesges RC. The relationship between socioeconomic status, ethnicity, and cigarette smoking in urban adolescents. Prev Med. 2002;34(2):171–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Byrne S, Greiner Safi A, Kemp D, Skurka C, Davydova J, Scolere L, et al. Effects of varying color, imagery, and text of cigarette package warning labels among socioeconomically disadvantaged middle school youth and adult smokers. Health Commun. 2019;34(3):306–316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Byrne S, Kalaji M, Niederdeppe J. Does visual attention to graphic warning labels on cigarette packs predict key outcomes among youth and low-income smokers? Tob Regul Science 2018;4(6):18–37. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Grandpre J, Alvaro EM, Burgoon M, Miller CH, Hall JR. Adolescent reactance and anti-smoking campaigns: a theoretical approach. Health Commun. 2003;15(3):349–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Jarman KL, Kowitt SD, Queen TL, et al. Do smokers recall source or Quitline on cigarette constituent messages? Tob Regul Sci. 2018;4(6):66–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. McCullough A, Meernik C, Baker H, Jarman K, Walsh B, Goldstein AO. Perceptions of tobacco control media campaigns among smokers with lower socioeconomic status. Health Promot Pract. 2018;19(4):550–559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.