Listeria monocytogenes is a facultative Gram-positive intracellular bacterium that is capable of causing serious invasive infections in pregnant women, resulting in abortion, still-birth, and disseminated fetal infection. Previously, a clinical L. monocytogenes isolate, 07PF0776, was identified as having an enhanced ability to target cardiac tissue. This tissue tropism appeared to correlate with amino acid variations found within internalin B (InlB), a bacterial surface protein associated with host cell invasion.

KEYWORDS: Listeria monocytogenes, Met receptor, bacterial pathogenesis, fetus, InlB, pregnancy, vertical transmission

ABSTRACT

Listeria monocytogenes is a facultative Gram-positive intracellular bacterium that is capable of causing serious invasive infections in pregnant women, resulting in abortion, still-birth, and disseminated fetal infection. Previously, a clinical L. monocytogenes isolate, 07PF0776, was identified as having an enhanced ability to target cardiac tissue. This tissue tropism appeared to correlate with amino acid variations found within internalin B (InlB), a bacterial surface protein associated with host cell invasion. Given that the mammalian receptor bound by InlB, Met, is abundantly expressed by placental tissue, we assessed isolate 07PF0776 for its ability to be transmitted from mother to fetus. Pregnant Swiss Webster mice were infected on gestational day E13 via tail vein injection with the standard isolate 10403S, a noncardiotropic strain, or 07PF0776, the cardiac isolate. Pregnant mice infected with 07PF0776 exhibited significantly enhanced transmission of L. monocytogenes to placentas and fetuses compared to 10403S. Both bacterial burdens and the frequency of placental and fetal infection were increased in mice infected with the cardiac isolate. Strain 07PF0776 also exhibited an enhanced ability to invade Jar human trophoblast tissue culture cells in comparison to 10403S, and was found to have increased levels of InlB associated with the bacterial cell surface. Overexpression of surface InlB via genetic manipulation was sufficient to confer enhanced invasion of the placenta and fetus to both 10403S and 07PF0776. These data support a central role for surface InlB in promoting vertical transmission of L. monocytogenes.

INTRODUCTION

During the course of pregnancy, a critical balance must be established and maintained to enable the placenta and developing fetus to receive needed nutrients and physical protection required for healthy development while avoiding immune recognition as non-self by the mother. The guardian and gate-keeper role of the placenta is largely successful during pregnancy; however, there are a select number of pathogens that are able to successfully mitigate the placental barrier functions and invade and multiply within the placenta and fetus (1). Colonization of placental and fetal tissues by pathogens can be devastating, resulting in abortion or death of the newborn. As a general rule, pathogens that can successfully subvert the barrier of the placenta and cause infection of the fetus exhibit at least partial intracellular life cycles (1). The Gram-positive facultative intracellular bacterium Listeria monocytogenes is one of these subversive pathogens that successfully targets and multiplies within placental and fetal cells, leading to abortion and neonatal death.

L. monocytogenes is known as a widespread environmental bacterium that lives in the soil and can cause mild gastroenteritis in healthy individuals following the consumption of contaminated food products (2–4). Ingestion of the bacterium by immunocompromised individuals can lead to severe invasive disease that targets the central nervous system (2–4), with a high mortality rate of approximately 20% even with antibiotic treatment (5). As a result of disease severity, detection of the bacterium in even limited numbers in food items has been linked to extensive food recalls costing millions of dollars (6–10). L. monocytogenes is capable of withstanding a variety of stress conditions and treatments commonly used in the food industry to limit bacterial contamination, thus the organism can often survive and sometimes persist within food processing facilities (7, 10–13).

In addition to immunocompromised individuals and the elderly, pregnant women are also more likely to develop severe invasive disease following L. monocytogenes consumption (8). L. monocytogenes infection of the placenta and the fetus can lead to spontaneous abortion, stillbirth, preterm labor, and disseminated fetal infection. Infection in the placenta and fetus is associated with a very high mortality rate for the fetus or neonate, with death occurring in about 20 to 60% of reported cases (1, 8, 14, 15). Often fetal infection may not be recognized in pregnant women until fetal death has occurred, and thus there is a need to better understand how L. monocytogenes crosses the placental barrier and to determine if there are isolates that pose greater risk of fetal infection.

The placenta must function to protect the fetus from harmful pathogens while avoiding maternal immune responses that could lead to rejection of the fetus, thus maintaining a precarious but critical balancing act (1, 16). The placenta fulfills this role using its unique structure composed of both maternal and fetal-derived cells. In humans, placental structure consists of branching villi that include floating villi as well as villi that anchor the placenta to the maternal decidua (1, 17–19). The human placenta is hemochorial, meaning that the trophoblast cells of the floating villi are in direct contact with maternal blood (1, 17, 18). There are two layers of trophoblast cells, where a continuous fused layer of multinucleated syncytiotrophoblast cells are in direct contact with maternal blood and then there is an underlying layer of cytotrophoblast cells. In addition to trophoblast cells, the villous stroma and fetal endothelial cells act as another component of the placental barrier to separate the maternal and fetal blood. Lastly, extravillous cytotrophoblast cells invade the decidua and anchor the villi to the decidua (16–18). This unique structure presents two potential routes of infection by which pathogens such as L. monocytogenes can infect the placenta: (i) direct invasion of syncytiotrophoblast cells resulting from the contact of these cells with maternal blood, and (ii) cell-to-cell spread through extravillous cytotrophoblast cells that anchor the placenta to the decidua (1, 17).

We have recently reported that subpopulations of L. monocytogenes can exhibit distinct tissue tropisms (20, 21). A subpopulation of clinical isolates has been identified that appear to exhibit enhanced cardiac myocyte infection in vitro and enhanced heart colonization in mice (21). These differences in cardiac infection were suggested to associate with distinct alleles of either InlA or InlB, two L. monocytogenes surface proteins linked to the invasion of mammalian cells. InlA has been associated with the invasion of intestinal epithelial cells, whereas InlB has been associated with the direct invasion of a broader sampling of host cells via its binding to glycosaminoglycans and to the widespread host cell growth factor receptor Met (22–24). Given that Met has been shown to be of pivotal importance in the development of the placenta (24–26) and that cardiotropic L. monocytogenes strains exhibit variations in InlB, we assessed the ability of a cardiotropic strain to target the placenta and fetus using a mouse model of pregnancy. While animals such as nonhuman primates have placentas that are more similar to that of humans, mouse models offer many tools to facilitate the study of vertical transmission of L. monocytogenes and the resulting host responses. Like humans, mice have hemochorial, discoid placentas, meaning that nutrient exchange occurs at fetal-capillary-rich chorionic villi which are bathed in maternal blood. In addition, mice are genetically tractable, cost-effective, and have a short gestation, making them an attractive model system for the exploration of L. monocytogenes vertical transmission.

RESULTS

Cardiotropic strains of L. monocytogenes exhibit enhanced vertical transmission.

Pregnant outbred Swiss Webster mice were used to compare the efficiency of vertical transmission between the well-studied L. monocytogenes isolate 10403S and a previously described isolate recovered from a cardiac abscess, strain 07PF0776, as well as J4403, a clinical isolate recovered from pericardial fluid (20, 21). Pregnant mice were infected with 5 × 103 CFU of L. monocytogenes via tail vein injection at gestational age E13. At 84 h postinfection, mice were sacrificed and the maternal liver, spleen, and heart, as well as the placentas and fetuses, were collected. Similar to nonpregnant mice, pregnant Swiss Webster mice infected with cardiotropic strains 07PF0776 or J4403 had similar bacterial burdens in the liver and spleen compared to the common laboratory reference strain 10403S (Fig. 1A). As previously demonstrated, both 07PF0776 and J4403 exhibited enhanced colonization of the heart, with 50% and 60% rates of colonization, respectively, compared to lack of colonization by 10403S (Fig. 1A). Interestingly, pregnant mice infected with the cardiotropic strains exhibited an enhanced frequency of bacterial colonization of the placenta and fetus compared to mice infected with 10403S (Fig. 1B and C). Pregnant mice infected with strains 07PF0776 and J4403 exhibited increased frequency of infection of the placenta, with 55% and 48% infected, respectively, and in the fetus, with 24% and 29% infected, respectively, in comparison to 10403S, which had 16% of placentas infected and 8% of fetuses infected (Fig. 1B and C). A modest but significant increase in bacterial CFU was observed in the placentas of mice infected with strain 07PF0776 relative to 10403S, but differences were not significant in the fetuses (Fig. 1D and E). Pregnant mothers that exhibited higher bacterial burdens in the maternal organs were more likely to exhibit bacterial colonization of the placentas and fetuses; however, the magnitude of the bacterial burdens within the placentas and fetuses tended to vary by a greater degree (Fig. 1B and C). It was also apparent that the infected placentas and fetuses came from a broad cross section of mothers infected with the cardiac strains, rather than a few mothers contributing to the bulk of the bacterial counts. As we have previously characterized isolate 07PF0776 for cardiac infections in mice (21), and have also published its sequenced genome, we focused on this isolate for subsequent assays.

FIG 1.

Cardiotropic isolates 07PF0776 and J4403 exhibit enhanced vertical transmission in pregnant mice. Pregnant Swiss Webster mice were infected with either 10403S or a cardiotropic strain (07PF0776 or J4403) with 5 × 103 CFU via tail vein injection on day E13 of gestation. At 84 h postinfection, maternal livers, spleens, and hearts, as well as placentas and fetuses, were collected, homogenized, and bacterial CFU were quantitated. (A to E) Each colored dot represents a single mouse and the corresponding placentas and fetuses. (A) Bacterial burdens in the maternal liver, spleen, and heart. (B and C) Bacterial burdens in the placenta (B) and fetus (C). Frequency of infection in the heart, placenta, and fetus are indicated as percentages. (D and E) Bacterial burdens derived only from infected placentas (D) and fetuses (E) for comparison. The median is indicated with a solid black line. The limit of detection is indicated with a dashed black line. Statistics were calculated using the Mann-Whitney test (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; ****, P < 0.0001).

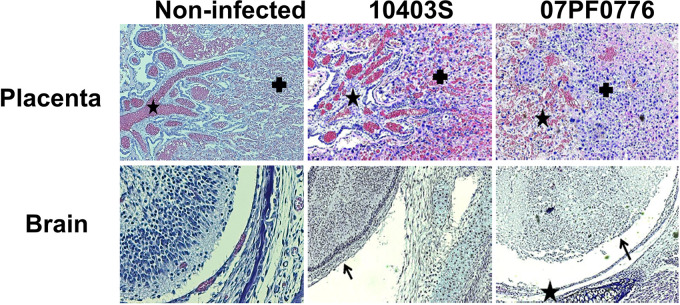

The placentas and fetuses of pregnant mice infected with isolate 07PF0776 were found to exhibit more severe pathology compared to those obtained from pregnant mice infected with strain 10403S. For example, placentas infected with isolate 07PF0776 exhibited more extensive inflammation compared to placentas infected with strain 10403S (Fig. 2, top panels). The fetuses derived from mothers infected with strain 07PF0776 showed significant tissue degradation, together with immune infiltration in multiple areas of the fetus (Fig. 2). The central nervous system (CNS), including the spinal cord, showed complete degeneration of cerebral layers, while a loss of neural layers was observed in the cerebral cortex, indicating irreversible loss of neural tissue (Fig. 2, bottom panels). Sporadic inflammation of the meninges was also observed in fetuses infected with strain 07PF0776 (Fig. 2, bottom panels). Collectively, the deterioration of the tissue observed in the fetuses infected with strain 07PF0776 was consistent with imminent abortion of the fetus.

FIG 2.

Placentas and fetuses infected with isolate 07PF0776 demonstrate more severe pathology compared to those infected with strain 10403S. At 84 h postinfection with either 10403S or 07PF0776, placentas and fetuses were collected and fixed in 4% formalin for 4 to 5 days. Samples were then sectioned and stained with H&E. (Top) Placentas infected with either 10403S or 07PF0776. Maternal (cross) and fetal (star) compartments are indicated. (Bottom) Brains of fetuses infected with either 10403S or 07PF0776. Loss of cortical layering (arrows) and focal meningitis (star) are observed.

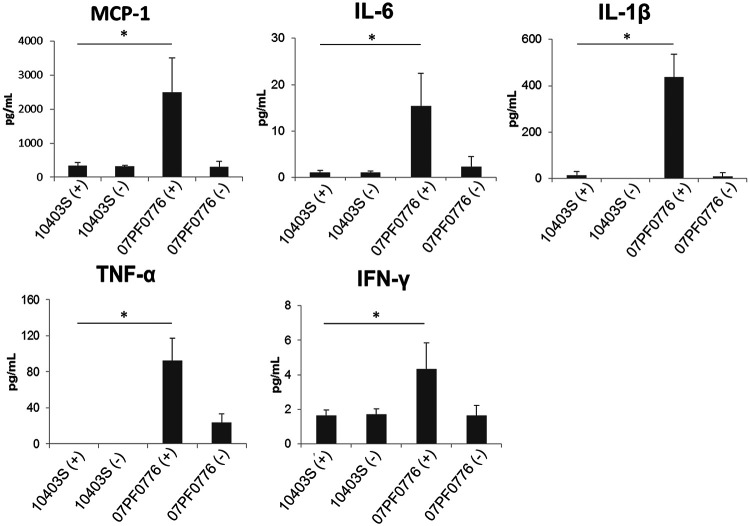

A robust innate immune response is critical for limiting L. monocytogenes invasion and replication; however, inflammation induced by infection can harm the fetus and lead to fetal wasting and/or abortion (27–29). We therefore assessed the levels of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines previously implicated in the control of L. monocytogenes in the fetuses of pregnant mice infected with either 10403S or 07F0776 strains. Overall, proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines were elevated in fetuses infected with strain 07PF0776 compared to those either infected with strain 10403S or in fetuses without detectable bacterial burdens from mothers infected with either L. monocytogenes strain (Fig. 3). Fetuses infected with isolate 07PF0776 exhibited approximately 14- and 30-fold increases in interleukin 6 (IL-6) and IL-1β, respectively, in comparison to fetuses harboring 10403S infections. The most dramatic increases were observed for tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), with a 921-fold increase in fetuses infected with isolate 07PF0776 in comparison to 10403S, where fetuses infected with 10403S did not exhibit detectible levels of TNF-α. Fetuses which were not infected but were derived from mothers infected with strain 07PF0776 also exhibited an apparent increase in TNF-α; however, this increase was not statistically significant (Fig. 3). Moderate increases in gamma interferon (IFN-γ) and monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 (MCP-1) were observed, with 2.6- and 7.6-fold changes, respectively, for fetuses harboring 07PF0776 compared to 10403S. Of note, fetuses derived from pregnant mice that were infected with isolate 07PF0776 but did not have detectible bacterial burdens within the fetus did not exhibit a significant increase in IL-6, IL-1β, IFN-γ, or MCP-1, indicating that 07PF0776 fetal infection is necessary to elevate the levels of these proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines (Fig. 3).

FIG 3.

Fetuses infected with isolate 07PF0776 exhibit increased levels of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines. Pregnant mice infected with either 10403S or 07PF0776 were sacrificed at 84 h postinfection and fetuses were collected. The fetuses were then homogenized and a sample of each homogenate was plated to determine bacterial CFU and was used in a Bio-Plex Pro assay to quantify select cytokine and chemokine levels. (+) Indicates the fetal tissue homogenate exhibited detectable bacterial burdens. (−) Indicates the fetal tissue homogenate did not exhibit detectable bacterial burdens. Data shown represent values obtained from 3 fetuses ± the standard error of the mean (SEM). Statistics were calculated using Student’s t test with Welch’s correction (*, P < 0.05).

Enhanced vertical transmission of cardiotropic isolate 07PF0776 is dependent on InlB.

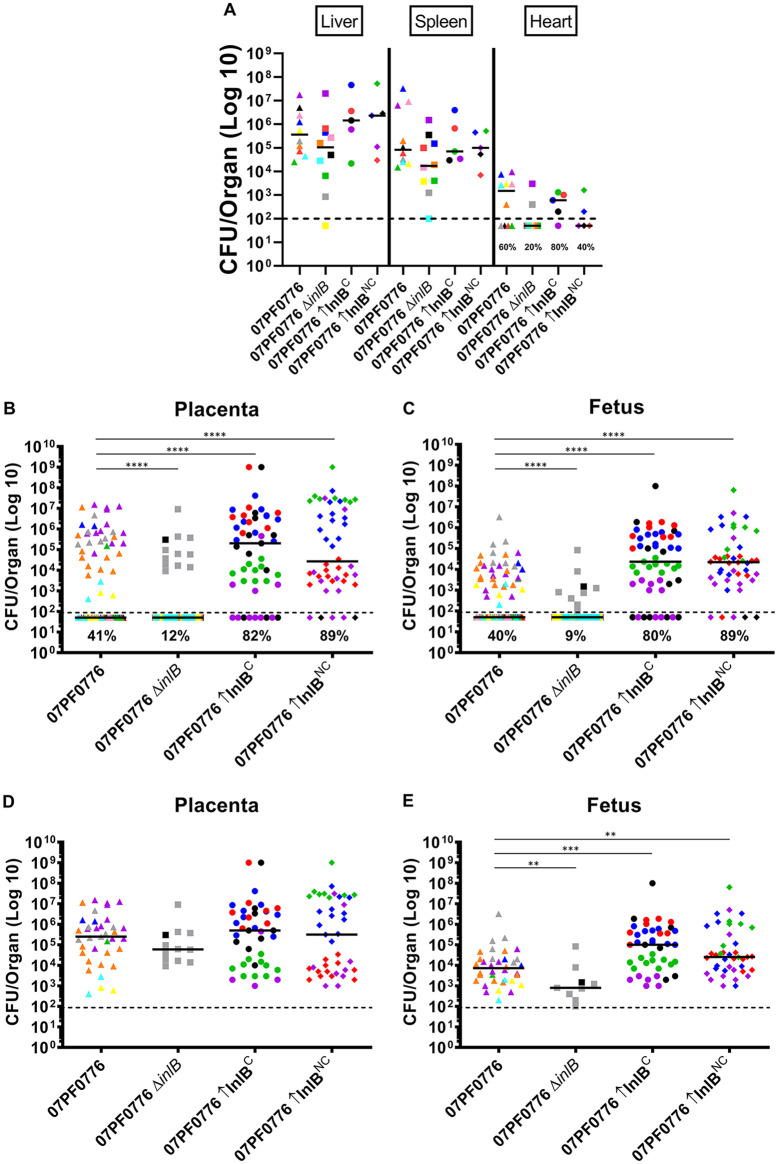

It has been previously speculated that the enhanced invasion of cardiac tissue by isolate 07PF0776 is associated with amino acid variations present within InlB (26). The InlB receptor, Met, is abundant in placental tissue, therefore we examined the role of InlB in placental and fetal infection. Pregnant mice infected with strain 07PF0776 lacking inlB (07PF0776 ΔinlB) exhibited reduced frequency of cardiac infection in comparison to pregnant mice infected with the wild-type strain (20% versus 60%) (Fig. 4A). Consistent with this result, overexpression of inlB via plasmid integration into a neutral site within the 07PF0776 chromosome (InlBC) modestly increased cardiac infection frequency (from 60% to 80%) (Fig. 4A). Importantly, pregnant mice infected with 07PF0776 lacking inlB (07PF0776 ΔinlB) exhibited significant reductions in the frequency of bacterial colonization of the placenta and fetus compared to pregnant mice infected with 07PF0776, where bacterial colonization of the placenta and fetus in pregnant mice infected with 07PF0776 ΔinlB was reduced from 41% and 40% (07PF0776) to 12% and 9% in the placentas and fetuses, respectively (Fig. 4B to E). Overexpression of inlB further increased bacterial burdens in the fetus and doubled the frequency of infection compared to isolate 07PF0776, with frequencies increasing from 41% and 40% (07PF0776) to 82% and 80% (07PF0776 InlBC) in the placenta and fetus, respectively (Fig. 4B to E). Taken together, these data support a critical role for InlB in promoting the vertical transmission of 07PF0776. Of note, the reduction in bacterial burdens and reduced frequency of infection observed with the 07PF0776 ΔinlB strain resembled those observed for pregnant mice infected with 10403S (Fig. 1B and C, Fig. 4B and C). This suggests that the expression of inlB in 10403S may be so low as to mimic complete loss of inlB with respect to vertical transmission.

FIG 4.

Enhanced vertical transmission of cardiotropic isolate 07PF0776 is dependent on InlB. On day E13 of gestation, pregnant Swiss Webster mice were infected via tail vein injection with 5 × 103 CFU of either 07PF0776, a 07PF0776 deletion mutant lacking InlB (07PF0776 ΔinlB), or 07PF0776 overexpressing InlB (07PF0776 ↑InlBC). At 84 h postinfection, maternal livers, spleens, and hearts, as well as placentas and fetuses, were collected. The samples were then homogenized and bacterial CFU were quantitated. (A to E) Each colored dot represents a mother and the corresponding placentas and fetuses. (A) Bacterial burdens in the maternal liver, spleen, and heart. Frequency of infection of the heart is indicated as a percentage. (B and C) Bacterial burdens in the placenta (B) and fetus (C). Frequency of infection in the placenta and fetus are indicated as percentages. (D and E) Bacterial burdens derived only from infected placentas (D) and fetuses (E) for comparison. The median is indicated with a solid black line. The limit of detection is indicated by a dashed black line. Statistics were calculated using the Mann-Whitney test (**, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; ****, P < 0.0001).

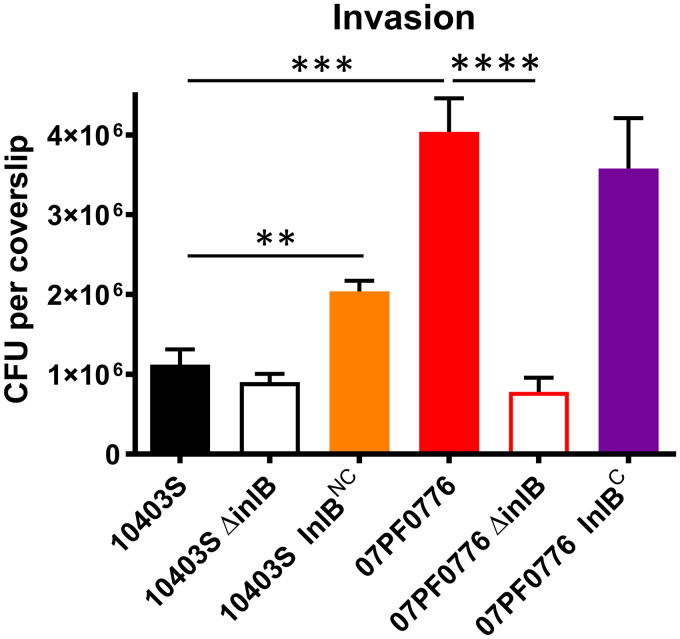

To examine how variations in InlB and/or InlB expression might impact invasion of placental cells, human Jar trophoblast tissue culture cells, representative of syncytiotrophoblast cells, were grown on glass coverslips and infected with either 10403S or 07PF0776 for 45 min at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 100. Gentamicin was subsequently added to kill extracellular bacteria and the infected cells were incubated for an additional hour. Cell monolayers infected with isolate 07PF0776 exhibited an approximately 4-fold increase in the level of cell invasion compared to strain 10403S (Fig. 5). While deletion of inlB in 10403S (10403S ΔinlB) did not significantly alter the already minimal levels of cell invasion observed, deletion of inlB in 07PF0776 (07PF0776 ΔinlB) reduced cell invasion by more than 80% in comparison to 07PF0776 (Fig. 5). Overexpression of inlB in the 10403S background was sufficient to significantly increase invasion approximately 2-fold compared to 10403S, however, overexpression of inlB in the 07PF0776 background did not enhance invasion (Fig. 5). Taken together, these data support a role for InlB in promoting 07PF0776 invasion of cell culture trophoblast cells and suggest that increased expression of InlB can enhance bacterial cell invasion by an otherwise minimally invasive strain (10403S).

FIG 5.

Isolate 07PF0776 exhibits increased levels of invasion in human Jar trophoblast cells. Invasion efficiency was determined using a cell culture invasion assay. Coverslips with a monolayer of human Jar trophoblast cells was infected with the indicated bacterial strains. At 45 min postinfection, the cells were washed and gentamicin was added to kill extracellular bacteria. After an hour, the coverslips were removed, lysed in water, and CFU per coverslip was enumerated. Statistics were determined using Student’s t test (**, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; ****, P < 0.0001).

Increased amounts of bacterial surface InlB enhance L. monocytogenes vertical transmission.

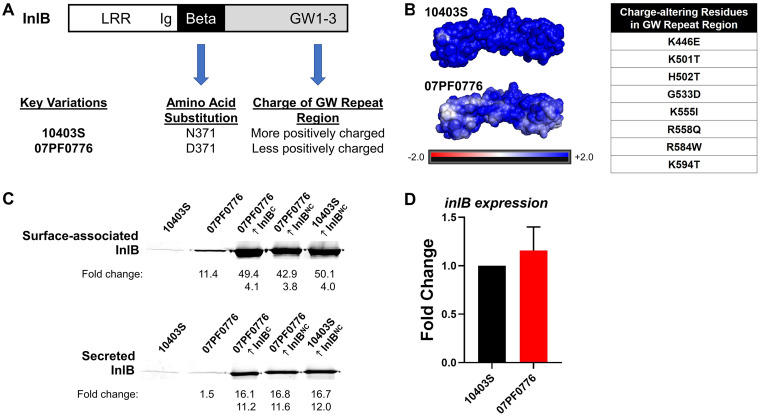

InlB features several protein domains associated with distinct functional roles contributing to bacterial host cell invasion (Fig. 6A). The InlB N-terminal domain consists of leucine-rich repeats that bind to the Met receptor (23, 30). A beta repeat region has been suggested to serve as a linker between the N-terminal and the C-terminal domains, the latter of which contains three GW repeats that electrostatically bind to cell wall teichoic acid (WTA) on the bacterial cell surface (23, 30, 31). Comparison of 10403S and 07PF0776 InlB amino acid sequences indicates that while there is substantial conservation of amino acid sequences (over 93% identity), there exist unique amino acid variations within select functional domains of InlB (Fig. 6A and B). We therefore explored whether subtle differences in inlB might contribute to the efficiency of placental and fetal infection when comparing strains 10403S and 07PF0776.

FIG 6.

Isolate 07PF0776 exhibits increased levels of InlB associated with the bacterial cell surface compared to 10403S. The bacterial surface protein InlB contains several functional domains that contribute to host cell invasion. The N-terminal domain contains leucine-rich repeats (LRR) which bind to the Met receptor. Following the LRR domain, there is an immunoglobulin-like region (Ig). The beta repeat region serves as a linker and the GW repeat region electrostatically binds to teichoic acids on the bacterial cell surface. (A) There are variations in the amino acid sequences between 10403S and 07PF0776 in the beta repeat and GW repeat regions. (B) Electrostatic modeling of the GW repeat regions of 10403S and 07PF0776 using PyMol software in conjunction with APBS. Isolate 07PF0776 exhibits a less positively charged GW repeat region compared to 10403S and the charge-altering residues from 10403S to 07PF0776 are listed. (C) Western blot analysis of surface-associated (top) and secreted (bottom) InlB for strains 10403S, 07PF0776, and strains overexpressing InlB. The fold changes compared to 10403S or 07PF0776 are indicated with the top and bottom values, respectively. (D) inlB transcription was assessed using qPCR for 10403S and 0PF0776. The fold change was compared to 10403S. Data were normalized to an endogenous control gene, rpoB. Statistics were calculated using the Student’s t test and P values were adjusted using Benjamini-Hochberg False Discovery. The fold change P value between 10403S and 07PF0776 was not significant.

Western blot analyses were used to compare levels of InlB secretion and protein association with the bacterial cell surface for 10403S and 07PF0776 strains. Bacteria were grown in brain heart infusion (BHI) medium overnight at 37°C with shaking, subcultured, and grown to mid-log phase. The samples were normalized based on cell culture optical density at 600 nm (OD600) to ensure that the numbers of bacteria were equivalent across samples. Fractions containing secreted InlB or surface-associated InlB were isolated and compared. The 07PF0776 strain exhibited increased levels of surface-associated InlB in comparison to the levels found associated with 10403S (11-fold increase over 10403S) (Fig. 6C). This difference in surface-associated InlB was not the result of increased transcription of inlB by 07PF0776, as transcript levels were found to be equivalent between the two strains (Fig. 6D). Strains engineered to overexpress InlB via plasmid introduction exhibited an even greater abundance of surface-associated InlB, with levels 42- to 50-fold higher in comparison to 10403S (Fig. 6C). In contrast, no significant differences were observed in the levels of secreted InlB between 07PF0776 and 10403S strains (Fig. 6C).

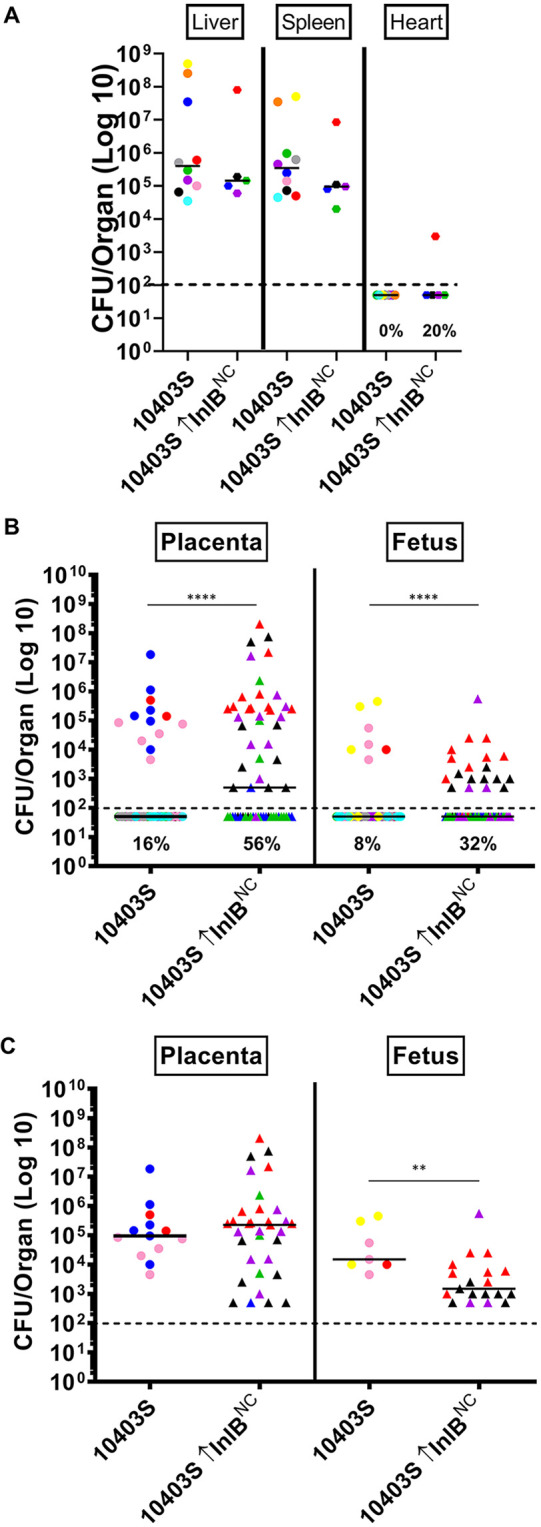

As observed previously, overexpression of the 07PF0776 inlB allele (InlBC) in the 07PF0776 background significantly increased both the bacterial burdens in the fetus and frequency of infection in placenta and fetus in comparison to the 07PF0776 parent strain (Fig. 4B and C). Similarly, overexpression of the inlB allele derived from 10403S (InlBNC) within the 07PF0776 background also resulted in increased bacterial burdens in the fetus and frequency of infection of the placenta and fetus (from 41% and 40% to 89% and 89%, respectively), illustrating that the increases are not inlB allele-specific (Fig. 4B and C). Related to the findings for 07PF0776, when the 10403S native inlB allele was overexpressed in the 10403S background, cardiac infection did not increase (Fig. 7A), however, the frequency of infection was significantly increased compared to that observed for the 10430S parent strain in both the placenta and fetus (Fig. 7B). The frequency of infection was found to increase from 16% and 8% in the placenta and fetus, respectively, to 56% and 32% in the placenta and fetus for animals infected with 10403S overexpressing its native inlB allele (Fig. 7B). Interestingly, although the frequency of infection was increased, the overall bacterial burdens were somewhat reduced in the fetus of animals infected with 10403S overexpressing its inlB in comparison to the wild-type strain (Fig. 7C). Taken together, these results strongly suggest that the amount of surface-associated InlB determines the efficiency of L. monocytogenes vertical transmission.

FIG 7.

Overexpression of InlB, regardless of genetic background, is sufficient to increase infection in the placenta and fetus. Pregnant Swiss Webster mice were infected with 5 × 103 CFU via tail vein injection of either 10403S or a strain overexpressing the noncardiotropic inlB allele (InlBNC) on gestational day E13. At 84 h postinfection, maternal livers, spleens, and hearts, as well as placentas and fetuses, were collected, homogenized, and bacterial CFU were quantitated. (A to C) Each colored dot represents a single mouse and the corresponding placentas and fetuses. (A) Bacterial burdens in the maternal liver, spleen, and heart. Frequency of infection of the heart is indicated as percentage. (B) Bacterial burdens in the placenta and fetus. Frequency of infection in the placenta and fetus are indicated as percentages. The 10403S data are the same as in Fig. 1 (C) Bacterial burdens derived only from infected placentas and fetuses for comparison. The median is indicated with a solid black line. The limit of detection is indicated as a dashed black line. Statistics were calculated using the Mann-Whitney test (**, P < 0.01; ****, P < 0.0001).

DISCUSSION

L. monocytogenes is recognized for having defined tissue tropisms, such as its ability to target the central nervous system or, as investigated in this current study, to circumvent the defenses of the placental barrier and cause severe infections in the developing fetus (1). Recent recognition that subpopulations of L. monocytogenes can target additional tissues, such as the heart, has stimulated interest in defining the bacterial factors that promote the acquisition of these previously unrecognized host niches (20, 21). The experiments described in this study illustrate that a select isolate of L. monocytogenes first recognized for its ability to cause cardiac infections also exhibits an enhanced capacity for vertical transmission from mother to child. The enhanced frequency of placental and fetal colonization observed appears to depend upon increased levels of expression of the bacterial surface-associated protein InlB. Overexpression of surface-localized InlB was sufficient to significantly increase the transmission of L. monocytogenes 10403S, a strain that normally exhibits limited infection of both the placenta and fetus. Our results indicate that a threshold level of surface-associated InlB is necessary for efficient L. monocytogenes colonization of the placenta and fetus, thus suggesting that alterations in the expression levels of L. monocytogenes surface proteins is sufficient to promote bacterial targeting of distinct host tissues.

Previous studies focused on vertical transmission using 10403S strains have reported that InlB contributes a negligible role in promoting bacterial colonization of the placenta and fetus (18, 32). The inoculation of pregnant mice with the L. monocytogenes cardiac isolate 07PF0776 indicates, however, a more substantial role for InlB in placental and fetal infection. The 07PF0776 strain lacking inB exhibited significant reductions in both bacterial burdens and in the frequency of infection in the placenta and fetus in comparison to the parent strain (Fig. 4). Bacterial invasion assays using tissue cell culture syncytiotrophoblast cells suggest that 07PF0776 is more invasive for these cells than 10403S and that this enhanced invasion is dependent upon InlB (Fig. 5). When comparing the placentas and fetuses from pregnant mice infected with either 10403S or 07PF0776, the bacterial burdens observed were generally similar; however, the frequency of placental and fetal infection was much higher for animals infected with 07PF0776. This suggests that both bacterial strains are essentially equivalent in their capacity for intracellular replication within these tissues, however, 07PF0776 is better able to target these cells or tissues for invasion. It is likely that the increased levels of surface-associated InlB expressed by 07PF0776 enabled the detection of a role for this protein in placental/fetal invasion that was not previously observed for strains expressing lower levels of InlB, such as10403S. It is possible that increased surface InlB leads to the enhanced invasion of other cell types in addition to placental and fetal cells; this remains to be determined in future investigations.

Consistent with the idea that high-level expression of surface-associated InlB enhances vertical transmission, 07PF0776 ΔinlB strains exhibited low-level colonization of the placenta and fetus that was similar to that observed for pregnant mice infected with strain 10403S. Previously published reports have indicated no differences in the levels of bacterial invasion observed between 10403S and 10403S lacking inlB using placenta-derived BeWo tissue culture cells in vitro or in in vivo infection models, including the guinea pig or human placental explants (18, 32). It is possible that the very small amounts of surface-associated InlB expressed by 10403S essentially mask any contributions of InlB to the invasion of placental cells and tissues.

Indeed, existing controversies regarding whether or not InlB contributes to the invasion of placental and fetal cells seems likely to result from the examination of strains, such as 10403S, that express levels of InlB that are below the threshold required for efficient placental and fetal invasion. In studies using human Jar trophoblast cells, as well as placental explants infected with another commonly used L. monocytogenes strain, EGD, Gessain et al. reported that InlB is critical for the invasion of cells in which the phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3-K) signaling pathway is not constitutively active, such as syncytiotrophoblasts (33).

InlB localizes to the surface of L. monocytogenes via noncovalent interactions between the GW repeat region of the protein and wall teichoic acids. Recent studies have shown that these teichoic acids exhibit structural diversity between serovars (34). Serovar 4b strains, such as 07PF0776, exhibit galactose moieties on teichoic acids, whereas serovar 1/2a strains, such as 10403S, lack these galactose moieties. For serovar 4b strains, retention of InlB on the bacterial cell surface depends on InlB binding to the galactose associated with wall teichoic acids (35). Indeed, preliminary data suggest that InlB derived from 07PF0776 is not retained on the bacterial cell surface when expressed by 10403S (N. Lamond, unpublished data). These differences in wall teichoic acid structural moieties may account for the increased level of InlB associated with the bacterial cell surface exhibited by strain 07PF0776 in comparison with strain 10403S, and it appears that allele-specific differences in inlB may influence binding of InlB to modified cell wall sugars. Therefore, optimal InlB function may depend both on the stability of surface-associated InlB as well as the affinity of InlB for cell wall teichoic acids.

Overall, the findings presented are noteworthy in that they demonstrate how the relative abundance of surface-associated InlB directly influences L. monocytogenes vertical transmission. It may be possible, therefore, to identify L. monocytogenes isolates that present increased risk to pregnant women based on surface InlB expression. It remains to be determined whether increased surface InlB enhances not only bacterial uptake via Met-dependent alterations in actin polymerization, but perhaps also through the stimulation of other Met-regulated pathways that govern cell survival and cell replication.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and plasmids.

Bacterial strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. In-frame inlB deletion mutants were generated using the allelic exchange method described previously (36). Briefly, 500-bp upstream and downstream regions flanking the coding region were amplified with external primers having BamHI and SalI restriction sites. These products were then joined using SOEing PCR to form a 1,000-bp product (37). This construct was then digested using BamHI and SalI and ligated into pKSV7, a temperature-sensitive allelic-exchange vector. Allelic exchange was then conducted and mutants selected based on chloramphenicol sensitivity. To confirm deletion of the gene, genomic DNA was isolated using the DNEasy blood and tissue kit (Qiagen), PCR amplified, and verified via gel electrophoresis and sequencing.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains used in this study

| Strain | Feature(s) | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| NF-100 | 10403S L. monocytogenes | 21 |

| NF-1403 | L. monocytogenes clinical isolate 07PF0776 from cardiac interventricular septal abscess | 21 |

| NF-1590 | L. monocytogenes clinical isolate J4403 from pericardial fluid | 21 |

| NF-3100 | 10403S ΔinlB | This study |

| NF-3165 | 10403S ΔinlB pIMK2-inlB10403S (inlBNC) | This study |

| NF-3167 | 10403S ΔinlB pIMK2-inlB07PF0776 (inlBC) | This study |

| NF-3351 | 07PF0776 ΔinlB | This study |

| NF-3585 | 07PF0776 ΔinlB pIMK2-inlB10403S (inlBNC) | This study |

| NF-3586 | 07PF0776 ΔinlB pIMK2-inlB07PF0776 (inlBC) | This study |

Strains overexpressing inlB were constructed by cloning the inlB open reading frame into pIMK2, a plasmid vector designed to overexpress selected genes through the use of a strong constitutive promoter that drives gene expression (38). The pIMK2 plasmid integrates in single copy within a neutral site of the L. monocytogenes chromosome. Strains containing integrated pIMK2-inlB were selected on BHI agar containing 50 μg/ml kanamycin.

Mouse infections.

The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees (IACUC) approved all animal procedures, which were performed in the Biological Resources Laboratory at the University of Illinois at Chicago. Overnight bacterial cultures were diluted 1:20 into fresh BHI media and grown to OD600 of ∼0.7 at 37°C with shaking. Cultures were washed, diluted, and resuspended in sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) to a final concentration of 5 × 103 CFU per 200 μl. Pregnant Swiss Webster mice (5 to 10 per group) (Charles River Laboratories) were infected with 5 × 103 CFU at gestational age E13 via tail vein injection. Mice were sacrificed at 84 h postinfection and maternal livers, spleens, and hearts, as well as placentas and fetuses, were collected and homogenized. Dilutions were plated on to LB agar plates for enumeration of CFU. Statistics were calculated using the Mann-Whitney test in GraphPad Prism software. Values below the limit of detection were recorded as the limit of detection minus one.

Histology.

A subset of placentas and fetuses were fixed in 4% formalin for 4 to 5 days. They were then sectioned, stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E), and mounted by the Histology Research Core at the University of Illinois at Chicago. Slides were analyzed using Zen Software on a Carl Zeiss Axio Imager 10 microscope.

Invasion assay.

A monolayer of human Jar trophoblast cells (ATCC HTB-144) was grown to 100% confluence on sterile glass coverslips coated in laminin in a 24-well plate, infected with 20 μl of the indicated bacterial strain with a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 100:1, and incubated at 37°C. Each of the strains tested was done in quintuplet for each strain. At 45 min postinfection, the cells were washed in sterile PBS warmed to 37°C and warm medium containing 5 μg/ml of gentamicin was added to kill extracellular bacteria. After an hour, the coverslips were removed and lysed in 1 ml of water. Dilutions were plated onto LB agar plates, grown overnight at 37°C, and CFU per coverslip was enumerated. Statistics were calculated using the Student’s t test in GraphPad Prism software.

Protein extraction and Western blotting.

The abundance of secreted InlB, as well as the level of InlB associated with the bacterial cell surface, were assessed as previously described (39, 40). Strains were grown overnight, subcultured in BHI, and grown to mid-log phase at 37°C with shaking. Samples were normalized to 0.7 based on cell culture density (OD600). Bacterial cell surface proteins were isolated from the bacterial pellet and the secreted protein was isolated from the culture supernatant. Protein was extracted from the pellet by resuspending the pellet in 200 μl of 2× SDS-boiling buffer and then boiling the sample. Culture supernatants were treated with 10% trichloroacetic acid (TCA), washed with ice-cold acetone, and then resuspended in 200 μl of 2× SDS-boiling buffer and boiled to extract the proteins.

Western blot analysis was then conducted to assess protein levels. An aliquot (15 μl, or 5 μl of the overexpressing-InlB strains) of the cell-associated and secreted protein extractions was separated using SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis at 100V for 10 min then 200V for 45 min. The protein samples were then transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes at 30V for 1 h. InlB protein was detected using a 1:1,000 dilution of a polyclonal antibody that binds to InlB (ABclonal Biotechnology Co., Ltd.). The membrane was then incubated with a 1:2,000 dilution of a polyclonal goat-anti rabbit secondary antibody (Southern Biotech). The InlB bands were then visualized using 10 ml of BCIP/NBT and band density was determined using ImageJ software.

Cytokine profile.

Pregnant mice were infected and sacrificed at 84 h postinfection as described above and the collected fetuses were homogenized. Bio-Plex Pro Assays (Bio-Rad Laboratories) were used to determine cytokine and chemokine profiles of fetal tissue homogenate using the manufacturer’s protocol. A Bioplex 200 plate reader was used to read the plates, which were then analyzed using Bio-Plex Manager 5.0 software. Statistics were calculated using Student’s t test with Welch’s correction.

RNA extraction and quantitative PCR.

Overnight cultures of the strains were subcultured in BHI and grown to mid-log phase at 37°C with shaking. Samples were normalized to 0.7 based on cell culture density (OD600). RNA extraction and quantitative PCR (qPCR) were conducted by the Genome Research Core at the University of Illinois at Chicago. Samples were extracted using Maxwell RSC simplyRNA Cells kit (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. RNA was transcribed to cDNA using the High-Capacity cDNA Reverse transcription kit with random primers (Applied Biosystems, CA). The cDNA synthesis was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The reverse-transcribed RNA (cDNA) was used for qPCR. The qPCR was run in triplicates using 2× TaqMan Fast Advanced Master Mix (Applied Biosystems) and 20× TaqMan Gene Expression Assays (Applied Biosystems). Amplification and detection were performed with a ViiA7 Real Time PCR system (Applied Biosystems). Data were normalized to an endogenous control gene, rpoB, and statistics were calculated using the Student’s t test in DataAssist software. P values were adjusted using Benjamini-Hochberg False Discovery. Primers used were the following: (i) inlB, forward primer 5′-AGCACAACCCAAGAAGGAA-3′; probe 5′-TGATAGTCTCCGCTTGTACTTTCGC-3′; reverse primer 5′-GCTTGATTGGCGTTGACAC-3′; (ii) rpoB, forward primer 5′-GCATCGTACGCGTAGAAGTTT-3′; probe 5′-TGCGCGAATCAGTGAAGTACTTGA; reverse primer 5′-ATCTCACGTAGCCCTTCATCT-3′.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank James Mansfield and members of the Freitag laboratory and the UIC Positive Thinking Group for helpful discussions.

This work was supported by NIH grant R21 HD090635 to N.E.F. and grant F31 AI094886 to P.D.M. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the funding source. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Robbins JR, Bakardjiev AI. 2012. Pathogens and the placental fortress. Curr Opin Microbiol 15:36–43. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2011.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dussurget O, Pizarro-Cerda J, Cossart P. 2004. Molecular determinants of Listeria monocytogenes virulence. Annu Rev Microbiol 58:587–610. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.57.030502.090934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Freitag NE. 2006. From hot dogs to host cells: how the bacterial pathogen Listeria monocytogenes regulates virulence gene expression. Future Microbiol 1:89–101. doi: 10.2217/17460913.1.1.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hain T, Chatterjee SS, Ghai R, Kuenne CT, Billion A, Steinweg C, Domann E, Kärst U, Jänsch L, Wehland J, Eisenreich W, Bacher A, Joseph B, Schär J, Kreft J, Klumpp J, Loessner MJ, Dorscht J, Neuhaus K, Fuchs TM, Scherer S, Doumith M, Jacquet C, Martin P, Cossart P, Rusniock C, Glaser P, Buchrieser C, Goebel W, Chakraborty T. 2007. Pathogenomics of Listeria spp. Int J Med Microbiol 297:541–557. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2007.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Drevets DA, Bronze MS. 2008. Listeria monocytogenes: epidemiology, human disease, and mechanisms of brain invasion. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol 53:151–165. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2008.00404.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hoffman S, Maculloch B, Batz M. 2015. Economic burden of major foodborne illnesses acquired in the United States. EIB-140, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service.

- 7.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 1998. Multistate outbreak of listeriosis —United States, 1998. Morbidity Mortality Wkly Report 47:1085–1086. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2015. National Listeria surveillance annual summary, 2013. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Georgia. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2015. Preliminary incidence and trends of infection with pathogens transmitted commonly through food—Foodborne Diseases Active Surveillance Network, 10 U.S. sites, 2006–2014. Morbidity and Mortality Wkly Report 64:495. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 1999. Update: multistate outbreak of listeriosis—United States, 1998–1999. Morbidity and Mortality Wkly Report 47:1117–1118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2004. Preliminary FoodNet data on the incidence of infection with pathogens transmitted commonly through food—selected sites, United States, 2003. Morbidity and Mortality Wkly Report 53:338–343. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mead PS, Slutsker L, Dietz V, McCaig LF, Bresee JS, Shapiro C, Griffin PM, Tauxe RV. 1999. Food-related illness and death in the United States. Emerg Infect Dis 5:607–625. doi: 10.3201/eid0505.990502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mead PS, Dunne EF, Graves L, Wiedmann M, Patrick M, Hunter S, Salehi E, Mostashari F, Craig A, Mshar P, Bannerman T, Sauders BD, Hayes P, Dewitt W, Sparling P, Griffin P, Morse D, Slutsker L, Swaminathan B, Listeria Outbreak Working Group. 2006. Nationwide outbreak of listeriosis due to contaminated meat. Epidemiol Infect 134:744–751. doi: 10.1017/S0950268805005376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2013. Vital signs: Listeria illnesses, deaths, and outbreaks—United States, 2009–2011. Morbidity and Mortality Wkly Report 62:448–452. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Madjunkov M, Chaudhry S, Ito S. 2017. Listeriosis during pregnancy. Arch Gynecol Obstet 296:143–152. doi: 10.1007/s00404-017-4401-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gude NM, Roberts CT, Kalionis B, King RG. 2004. Growth and function of the normal human placenta. Thromb Res 114:397–407. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2004.06.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lamond NM, Freitag NE. 2018. Vertical transmission of Listeria monocytogenes: probing the balance between protection from pathogens and fetal tolerance. Pathogens 7:52. doi: 10.3390/pathogens7020052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Robbins JR, Skrzypczynska KM, Zeldovich VB, Kapidzic M, Bakardjiev AI. 2010. Placental syncytiotrophoblast constitutes a major barrier to vertical transmission of Listeria monocytogenes. PLoS Pathog 6:e1000732. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maltepe E, Bakardjiev AI, Fisher SJ. 2010. The placenta: transcriptional, epigenetic, and physiological integration during development. J Clin Invest 120:1016–1025. doi: 10.1172/JCI41211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maury MM, Tsai Y, Charlier C, Touchon M, Chenal-Francisque V, Leclercq A, Criscuolo A, Gaultier C, Roussel S, Brisabois A, Disson O, Rocha EPC, Brisse S, Lecuit M. 2016. Uncovering Listeria monocytogenes hypervirulence by harnessing its biodiversity. Nat Genet 48:308–313. doi: 10.1038/ng.3501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alonzo F 3, Bobo LD, Skiest DJ, Freitag NE. 2011. Evidence for subpopulations of Listeria monocytogenes with enhanced invasion of cardiac cells. J Med Microbiol 60:423–434. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.027185-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ireton K. 2007. Entry of the bacterial pathogen Listeria monocytogenes into mammalian cells. Cell Microbiol 9:1365–1375. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2007.00933.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bierne H, Cossart P. 2002. InlB, a surface protein of Listeria monocytogenes that behaves as an invasin and a growth factor. J Cell Sci 115:3357–3367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Trusolino L, Bertotti A, Comoglio PM. 2010. MET signalling: principles and functions in development, organ regeneration and cancer. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 11:834–848. doi: 10.1038/nrm3012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kauma S, Hayes N, Weatherford S. 1997. The differential expression of hepatocyte growth factor and met in human placenta. J Clin Endocrinol Metabol 82:949–954. doi: 10.1210/jcem.82.3.3806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ueno M, Lee L, Chhabra A, Kim Y, Sasidharan R, Van Handel B, Wang Y, Kamata M, Kamran P, Sereti K, Ardehali R, Jiang M, Mikkola HA. 2013. c-Met-dependent multipotent labyrinth trophoblast progenitors establish placental exchange interface. Dev Cell 27:373–386. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2013.10.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zenewicz LA, Shen H. 2007. Innate and adaptive immune responses to Listeria monocytogenes: a short overview. Microbes Infect 9:1208–1215. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2007.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dussurget O, Bierne H, Cossart P. 2014. The bacterial pathogen Listeria monocytogenes and the interferon family: type I, type II and type III interferons. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 4:50. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2014.00050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rowe JH, Ertelt JM, Xin L, Way SS. 2012. Listeria monocytogenes cytoplasmic entry induces fetal wastage by disrupting maternal Foxp3+ regulatory T cell-sustained fetal tolerance. PLoS Pathog 8:e1002873. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Braun L, Dramsi S, Dehoux P, Bierne H, Lindahl G, Cossart P. 1997. InlB: an invasion protein of Listeria monocytogenes with a novel type of surface association. Mol Microbiol 25:285–294. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.4621825.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sumrall ET, Keller AP, Shen Y, Loessner MJ. 2020. Structure and function of Listeria teichoic acids and their implications. Mol Microbiol 113:627–637. doi: 10.1111/mmi.14472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bakardjiev AI, Stacy BA, Fisher SJ, Portnoy DA. 2004. Listeriosis in the pregnant guinea pig: a model of vertical transmission. Infect Immun 72:489–497. doi: 10.1128/iai.72.1.489-497.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gessain G, Tsai Y, Travier L, Bonazzi M, Grayo S, Cossart P, Charlier C, Disson O, Lecuit M. 2015. PI3-kinase activation is critical for host barrier permissiveness to Listeria monocytogenes. J Exp Med 212:165–183. doi: 10.1084/jem.20141406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shen Y, Boulos S, Sumrall E, Gerber B, Julian-Rodero A, Eugster MR, Fieseler L, Nyström L, Ebert M, Loessner MJ. 2017. Structural and functional diversity in Listeria cell wall teichoic acids. J Biol Chem 292:17832–17844. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M117.813964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sumrall ET, Shen Y, Keller AP, Rismondo J, Pavlou M, Eugster MR, Boulos S, Disson O, Thouvenot P, Kilcher S, Wollscheid B, Cabanes D, Lecuit M, Gründling A, Loessner MJ. 2019. Phage resistance at the cost of virulence: Listeria monocytogenes serovar 4b requires galactosylated teichoic acids for InlB-mediated invasion. PLoS Pathog 15:e1008032. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1008032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Smith K, Youngman P. 1992. Use of a new integrational vector to investigate compartment-specific expression of the Bacillus subtilis spoIIM gene. Biochimie 74:705–711. doi: 10.1016/0300-9084(92)90143-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Alonzo F III, Xayarath B, Whisstock JC, Freitag NE. 2011. Functional analysis of the Listeria monocytogenes secretion chaperone PrsA2 and its multiple contributions to bacterial virulence. Mol Microbiol 80:1530–1548. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07665.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Monk IR, Gahan CGM, Hill C. 2008. Tools for functional postgenomic analysis of Listeria monocytogenes. Appl Environ Microbiol 74:3921–3934. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00314-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ahmed JK, Freitag NE. 2016. Secretion chaperones PrsA2 and HtrA are required for Listeria monocytogenes replication following intracellular induction of virulence factor secretion. Infect Immun 84:3034–3046. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00312-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Port GC, Freitag NE. 2007. Identification of novel Listeria monocytogenes secreted virulence factors following mutational activation of the central virulence regulator, PrfA. Infect Immun 75:5886–5897. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00845-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]