This decision aid was developed to provide clinicians with a review of the effectiveness of chronic back pain treatment options while highlighting study quality. It is derived from our accompanying systematic review of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) on chronic low back pain (page e20).1

How was this tool developed?

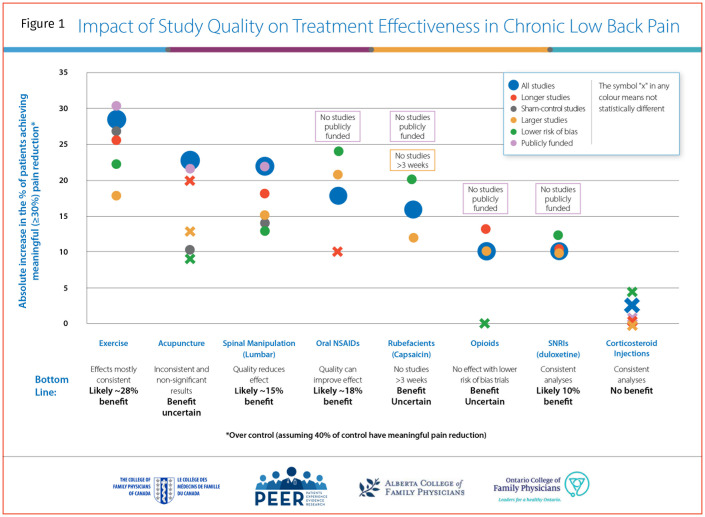

While systematic reviews provide an estimate of the mean effect of an intervention, when RCTs are pooled together in a meta-analysis, low-quality RCTs can skew the mean result, making an intervention appear more effective than it is. Researchers often apply different quality markers (eg, larger studies) to their systematic reviews to see if the results are consistent and reliable. These subgroup analyses are usually performed when there are a certain number of RCTs in order to ensure the analysis is adequately powered. In the systematic review, only 3 out of 8 interventions had an adequate number of RCTs for these subgroup analyses.1 Readers might overestimate the potential benefit of the intervention because the research quality was unexplored. We expanded the quality subgroup assessment to all interventions, regardless of the number of RCTs, to highlight the effects of each intervention depending on the quality markers applied, allowing the reader to determine which interventions have the most reliable data.

The primary outcome of our systematic review was the proportion of patients with chronic back pain who had a clinically meaningful response to treatment, generally defined as a 30% reduction in pain score, although the definition varied across RCTs.

We performed subgroup analyses for each intervention using the following quality markers: longer study duration (> 12 weeks), comparable placebo or sham treatment (as opposed to passive controls such as a waitlist), larger studies (> 150 participants), lower risk-of-bias scores (ie, median risk-of-bias score as per the systematic review), and publicly funded studies. The control rate was standardized to the mean control rate seen across all interventions (40%) for indirect comparison of efficacy across treatments. The risk ratio for each intervention was then applied to the standardized control rate to give the new intervention rate. The control event rate (40%) was subtracted from the new intervention rate to provide the absolute benefit over placebo (Figure 1). Differences between treatments are not from direct comparisons and represent approximations.

Figure 1.

Impact of Study Quality on Treatment Effectiveness in Chronic Low Back Pain

The decision aid

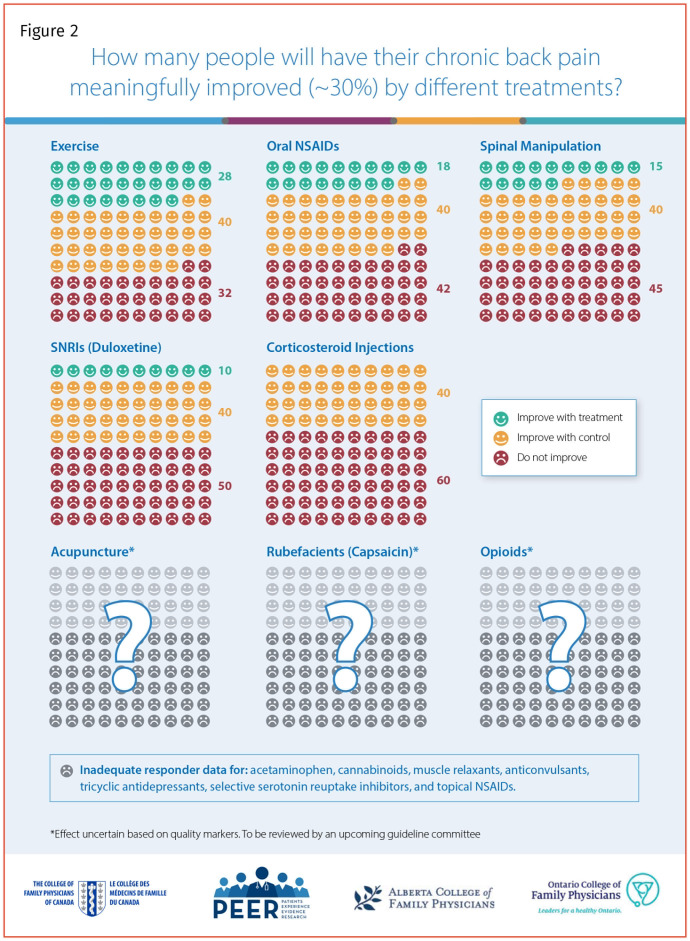

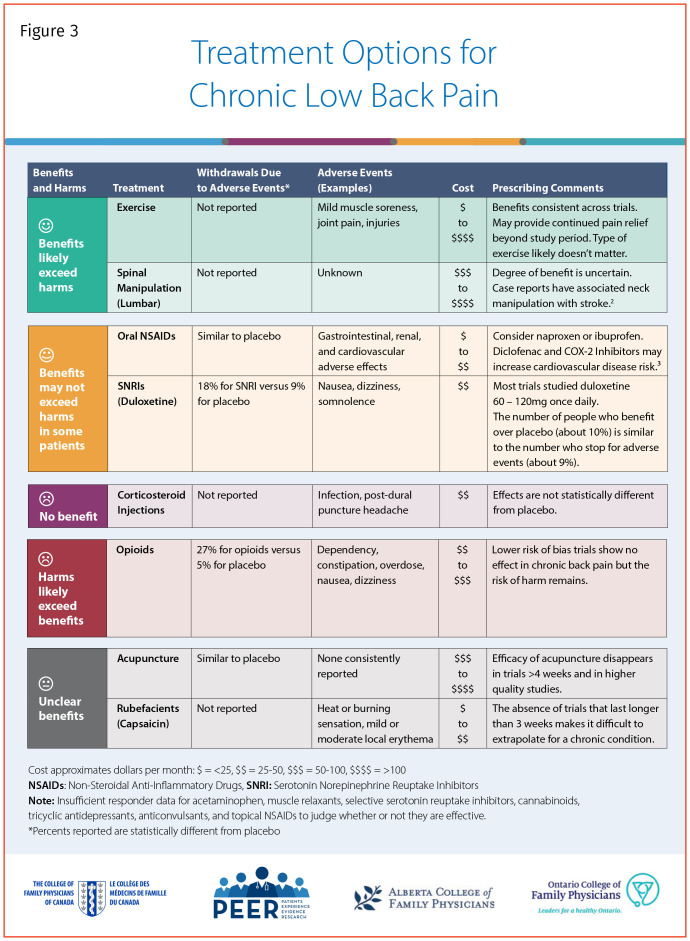

Figure 2 provides an icon array of the different treatments based on the analysis of the quality markers. Figure 31-3 classifies the treatments for chronic low back pain by benefits and harms, and provides information on withdrawals due to adverse effects, basic prescribing tips, and cost estimates. An interactive version can be found at www.pain-calculator.com, and a printable version of the entire decision aid is available from CFPlus.*

Figure 2.

How many people will have their chronic back pain meaningfully improved (~30%) by different treatments?

Figure 3.

Treatment Options for Chronic Low Back Pain

This decision aid is not a practice guideline and has not been assessed by an independent guideline committee for clinical use. However, the information presented here will be used in conjunction with other systematic reviews and tools to inform future guideline development.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

We thank the CFPC, Ontario College of Family Physicians, and Alberta College of Family Physicians for their continued support.

We encourage readers to share some of their practice experience: the neat little tricks that solve difficult clinical situations. Praxis articles can be submitted online at http://mc.manuscriptcentral.com/cfp or through the CFP website (www.cfp.ca) under “Authors and Reviewers.”

Footnotes

Competing interests

None declared

La traduction en français de cet article se trouve à www.cfp.ca dans la table des matières du numéro de janvier 2021 à la page e15.

Easy-to-print versions of Figures 1, 2, and 3 are available at www.cfp.ca. Go to the full text of the article online and click on the CFPlus tab.

This article is eligible for Mainpro+ certified Self-Learning credits. To earn credits, go to www.cfp.ca and click on the Mainpro+ link.

This article has been peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Kolber MR, Ton J, Thomas B, Kirkwood J, Moe S, Dugré N, et al. . PEER systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Management of chronic low back pain in primary care. Can Fam Physician 2021;67:e20-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nielsen SM, Tarp S, Christensen R, Bliddal H, Klokker L, Henriksen M.. The risk associated with spinal manipulation: an overview of reviews. Syst Rev 2017;6(1):64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Turgeon RD, Allan GM, Harbin M, Kolber MR.. NSAIDs and cardiovascular safety: the truth makes my heart hurt. Tools for Practice #101. Edmonton, AB: Alberta College of Family Physicians; 2018. Available from: https://gomainpro.ca/wp-content/uploads/tools-for-practice/1530897150_updatedtfp101nsaidscvrisk.pdf Accessed 2020 Oct 28. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.