Abstract

We have developed a novel, to our knowledge, in vitro instrument that can deliver intermediate-frequency (100–400 kHz), moderate-intensity (up to and exceeding 6.5 V/cm pk-pk) electric fields (EFs) to cell and tissue cultures generated using induced electromagnetic fields (EMFs) in an air-core solenoid coil. A major application of these EFs is as an emerging cancer treatment modality. In vitro studies by Novocure reported that intermediate-frequency (100–300 kHz), low-amplitude (1–3 V/cm) EFs, which they called “tumor-treating fields (TTFields),” had an antimitotic effect on glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) cells. The effect was found to increase with increasing EF amplitude. Despite continued theoretical, preclinical, and clinical study, the mechanism of action remains incompletely understood. All previous in vitro studies of “TTFields” have used attached, capacitively coupled electrodes to deliver alternating EFs to cell and tissue cultures. This contacting delivery method suffers from a poorly characterized EF profile and conductive heating that limits the duration and amplitude of the applied EFs. In contrast, our device delivers EFs with a well-characterized radial profile in a noncontacting manner, eliminating conductive heating and enabling thermally regulated EF delivery. To test and demonstrate our system, we generated continuous, 200-kHz EMF with an EF amplitude profile spanning 0–6.5 V/cm pk-pk and applied them to exemplar human thyroid cell cultures for 72 h. We observed moderate reduction in cell density (<10%) at low EF amplitudes (<4 V/cm) and a greater reduction in cell density of up to 25% at higher amplitudes (4–6.5 V/cm). Our device can be readily extended to other EF frequency and amplitude regimes. Future studies with this device should contribute to the ongoing debate about the efficacy and mechanism(s) of action of “TTFields” by better isolating the effects of EFs and providing access to previously inaccessible EF regimes.

Significance

Previous work reported that intermediate-frequency (100–300 kHz), low-amplitude (1–3 V/cm) electric fields (EFs) have an antimitotic effect capable of inhibiting the growth rate of cancers cell in vitro and in the clinic, although the mechanism of action remains unclear. Existing EF delivery systems use capacitively coupled electrodes placed in direct contact with the specimen holder. This direct contact generates unwanted heat and limits the amplitude and duration of EF stimulation. We have developed a novel, to our knowledge, in vitro system capable of continuous thermal regulation and delivery of well-characterized (200 kHz, 0–6.5 V/cm pk-pk), electromagnetic fields (EMFs) to cell cultures, paving the way for improved mechanistic biophysical studies.

Introduction

There is an extensive body of literature describing the effects of low- (DC-kHz) and high- (above 1 MHz) frequency electric fields (EFs) on living cells (1). Very-low frequency EFs (<2 kHz) are used to stimulate excitable cells, whereas high-frequency EFs are used to heat cells and tissues. Intermediate-frequency EFs (kHz-MHz) were previously considered to have no biological effects. However, Kirson et al. (2) reported that EFs at frequencies of 100–300 kHz and amplitudes between 1 and 3 V/cm had an antimitotic effect, inhibiting the proliferation rate of human and rodent tumor cell lines while having no effect on noncancerous cells. The inhibitory effect was reported to be frequency dependent, with a peak effect at 200 kHz for glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) cell lines (2). The inhibitory effect was also found to increase with EF amplitude (3). At higher EF amplitudes (≥2 V/cm), significant (>50%) inhibition relative to temperature-matched controls was reported (2,3). Kirson et al. labeled these EFs as “tumor-treating fields (TTFields).”

GBM is the most common and lethal adult brain tumor. Prognosis remains poor. Despite a combined treatment plan of maximal safe aggressive surgery, chemotherapy with temozolomide, and radiation, patients’ median survival is only 14–16 months from the time of diagnosis; one in four patients survive more than 2 years, and fewer than one in 20 survive more than 5 years (4,5). One significant feature of GBM is the highly invasive character of the cancer cells. This makes complete surgical resection impossible, leading to a recurrence rate of almost 100% (5,6). Based on preclinical results, “TTFields” entered clinical trials (7,8) and were approved by the Food and Drug Administration for newly diagnosed GBM cases in 2015, representing the first new GBM treatment modality in decades. “TTFields” have also been approved for treatment of pleural mesothelioma as of 2019 (9).

Despite ongoing, theoretical, preclinical, and clinical research, the mechanism(s) of action of “TTFields” is not well understood. Abnormal cell mitotic morphology, including blebbing followed by apoptosis (2,3,10), was observed when these EFs were applied to proliferating cells, suggesting a biophysical antimitotic mechanism of action. Computational models predicted that the penetration of EFs into cells is indeed frequency dependent, as suggested by findings by Kirson et al. (2). At ultralow frequency, EFs are largely screened and do not penetrate the cell membrane, whereas in the low-to-intermediate (100–500 kHz) frequency range, EFs are predicted to penetrate cells and could have a biophysical effect (11, 12, 13, 14).

In initial preclinical studies, Kirson et al. (2,3) proposed two specific mechanisms by which penetrative intermediate-frequency EFs could cause mitotic arrest and apoptosis. The first mechanism is an interaction of these EFs with the electric dipoles of tubulin dimers, which results in changes in tubulin dimer rotational dynamics, disrupting the formation and function of the mitotic spindle (2,15,16). The exact effects of EFs on microtubule polymerization were predicted to depend on the length of the microtubule filament as well as the frequency and amplitude of the applied EF. Effects on septin dimers were also proposed (10). However, more recent computational modeling suggests that EFs in the range of 1–3 V/cm are orders of magnitude too small to affect the rotational dynamics of tubulin and septin dimers (11,13,14,17,18).

The second mechanism of action proposed by Kirson et al. (2,3) was dielectrophoretic (DEP) forces resulting in electrokinetic effects on polarizable bio-macromolecules (i.e., those capable of producing a counterion cloud). During cytokinesis, a cleavage furrow appears between the dividing daughter cells. Computational models (13) predict that in and around these furrows, nonuniform EFs (i.e., EF gradients) produce DEP forces on charged, polarizable macromolecules and organelles (13,17). These DEP forces could potentially cause molecules to migrate toward or away from the furrow, impeding cell cleavage (11,13,17). Modeling studies incorporating Stokes drag (18), however, suggests that DEP forces are too small to cause substantial displacement over the course of telophase. Both of these proposed mechanisms also depend on the relative orientation of the dividing cells and the applied EF. Parallel alignment results in a maximal effect (3,13,14).

Recent preclinical studies support additional potential mechanisms and downstream effects, including but not limited to mitotic checkpoint inhibition (19), tubulin-mediated conductance effects (20), permeability changes (21), DNA damage (22,23), migratory inhibition (24), and autophagy (24,25). More recently, Neuhaus et al. (26) suggested voltage-gated calcium channels and Li et al. (18) suggested tumor cell membrane potential as mediating factors for the antiproliferative effect of intermediate-frequency EFs. Although several biophysical mechanisms are plausible, none have been conclusively demonstrated.

To advance their preclinical research on the use and mechanism(s) of action of “TTFields,” Novocure (St. Helier, Jersey) developed an in vitro test system (Inovitro) designed to deliver EFs to cell cultures using two pairs of capacitively coupled electrodes insulated by a high dielectric constant ceramic (3) placed orthogonal to each other inside a cell culture dish (3,27). The electrode pairs are connected to a high-voltage sinusoidal waveform generator. The stimulated electrode pair is switched periodically to maximize the orientational efficiency of EF application (3). Although contact between the culture dish and electrodes creates a direct means for EFs to be delivered to cell or tissue cultures, it also results in heat conduction from the electrodes to the dish and subsequently from the dish to the culture media, making continuous temperature control problematic. Joule or Ohmic heating from the EFs themselves also significantly contributes to heating of the conductive cell media.

To maintain a temperature of 37°C in the culture dish, EF application with the Inovitro device is performed in an 18°C incubator (28). Electric current limits and an on-off operation are also imposed as necessary to maintain temperature (3,28). A consequence of keeping the apparatus in this refrigerated environment is a lower surrounding water vapor pressure, which accelerates cell media evaporation. Assuming 95% relative humidity in the incubator, a loss of ∼0.2 mL of media per day can be expected from a 35-mm diameter dish (see Supporting Materials and Methods, Section S1). As a result, media replacement is required every 24 h according to procedures for operating the Inovitro device (Novocure) (2,28). This rapid media loss and replacement may have inadvertent confounding effects, such as causing time-varying hyperosmotic bath conditions. Hyperosmotic conditions can result in nuclear lamina buckling (29), cell cycle disruption (30), or protein aggregation (31). Another issue is that the geometry of the EF delivery device does not lend itself to easily predicting the EF or current density produced within the tissue or cell culture (12,14).

To overcome some of these limitations associated with delivering EFs via contacting electrodes, here, we describe a novel, to our knowledge, device that uses electromagnetic induction to deliver EFs or electromagnetic fields (EMFs) in vitro, like those generated by transcranial magnetic simulation (TMS) devices (32) but in a higher frequency range. More specifically, we propose the use of an air-core double solenoid coil in an LC (i.e., inductor-capacitor) resonant circuit to induce intermediate-frequency EMF in the cell or tissue cultures placed within the coil. This noncontacting method of EMF delivery thermally isolates the current-carrying coil from the culture dishes. Temperature uniformity and osmolarity control of the culture medium are improved. Greater power delivery is made possible, providing potential access to high, previously inaccessible EF amplitudes. Furthermore, the radial, linearly varying amplitude of the induced circumferential EF within the coil allows each culture dish to be exposed to a known and well-characterized range of EF amplitudes or “doses.” Induced EMFs represent a promising alternative EF delivery method for in vitro experimentation and may better elucidate the biophysical mechanisms of action of “TTFields” than the current state-of-the-art.

Materials and Methods

200-kHz-induced EMF generation

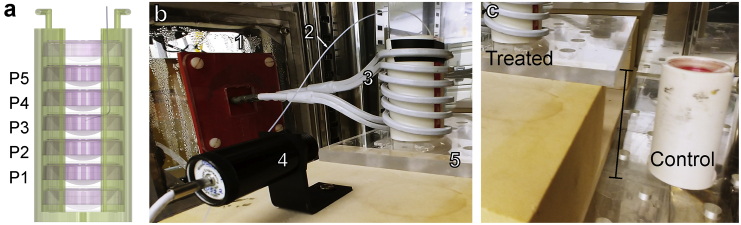

EMF generation was accomplished using an industrial 10-kW induction heater system (DP-10-400; RDO Induction, Washington, NJ) based on a conventional LC resonant circuit design (with a resonant angular frequency of 250 kHz). The induction device was connected to a copper coil built to the following specifications: inner diameter of 5 cm, height of 8 cm, three turns, double-wrapped, and with vertical orientation (Fig. 1 b, 3). The induction system and coil were jacketed and connected to a water chiller (DuraChill DCA200; PolyScience, Niles, IL) to remove heat and control coil temperature. To place the coil inside the 95% air, 5% CO2 incubator at 37°C (MCO-18M Multigas Incubator; SANYO Electric, Osaka, Japan), a 22 × 22 cm hole (Fig. 1 b, 1) was made in the incubator to avoid Joule heating of the metal lining via induction currents passing through the copper pipes connecting the coil to the induction device. The hole was covered and sealed with Plexiglas connected to the incubator. A Plexiglas shelf was placed below the coil (Fig. 1 b, 5), replacing the metal shelf of the incubator, again to avoid inductive heating. Plastic sleeves for cell culture dishes were made in-house on a three-dimensional printer (Fig. 1 a). Each sleeve accommodates seven 35-mm cell culture dishes in a vertical stack, so several culture dishes can be studied in parallel. The middle five dishes are situated fully within the coil, and their positions are labeled P1–P5. The dish in the third position from the bottom is referred to as P3 and is shown with a fiber optic temperature sensor placed in its center (Fig. 1 a). An infrared detector records the coil temperature (Fig. 1 b, 4). EMFs were delivered continuously for 72 h in all experiments.

Figure 1.

Experimental apparatus inside incubator. (a) Rendering of a dish sleeve containing stack of seven 35-mm cell culture dishes. Vertical positions labeled P1–P5. A fiber optic temperature sensor is placed into the P3 dish. (b) Inside view of the modified incubator and experimental apparatus (1). 22 cm 22 cm Plexiglas window (2). Fiber optic sensor (3). Double-wrapped copper coil, three turns, inner diameter = 5 cm, height = 8 cm, attached to induction device (4). Infrared detector (5). Plexiglas shelf. (c) Relative position of control stack, off-axis from the treated sleeve to avoid the 1/r EMF contribution outside the coil—see Eq. 3. To see this figure in color, go online.

The expected EF profile generated within the coil by the induction device can be calculated from basic principles of electricity and magnetism. The magnetic field within an air-core current-carrying coil is readily approximated by Ampere’s law,

| (1) |

where Bz(t) is the axial component of the applied magnetic field, B, μ0 is the permeability of a vacuum, I is the current amplitude, N is the number of coil turns, and L is the length of the coil. The direction of the magnetic field is normal to the direction of the current and can be determined by the right-hand rule as being along the coil axis. Faraday’s law in integral form relates the magnetic field to the electromotive force, ε,

| (2) |

where E is the induced EF, S denotes some bounded surface, and dl is an infinitesimal arc length. If the surface is chosen to be a circular cross section of the coil with radius r from the center of the coil, then the following solutions are obtained for |E(t)|,

| (3) |

where R is the radius of the coil, and Eθ(r, t) is the azimuthal component of the EF. By symmetry, the other two components of the EF vanish. The direction of the EF is antiparallel to the current flowing in the coils. If the applied current is sinusoidal, e.g., I(t) = I0cos(ωt), then the induced EF will oscillate at the same frequency in the circumferential direction. By Eq. 3, our induction system delivering current at 200 kHz results in a circumferential 200-kHz EF profile within the coil with a linearly increasing amplitude from the center of the coil. Importantly, the radial profile of the generated EFs makes each treated dish its own “dose titration” experiment, with little to no EFs dose or amplitude in the center of the dish and high dose at the periphery. The effects of EF amplitude can be isolated from any dish-to-dish experimental confounds by analyzing radially dependent differences within a single treated dish.

Note, the EF outside of the coil is expected to decay by 1/r according to Eq. 3. The EF in the incubator outside the coil is therefore not 0. Because of this decaying EF, the control dish sleeve is placed in the incubator at a distance and vertical height offset (off axis from the coil) such that little to no EF should be present, as shown in Fig. 1 c.

Temperature monitoring and control

Joule heating remains a major hurdle to delivering increased EF amplitudes while maintaining controlled temperatures, even in the absence of conductive heating from contacting electrodes. Heating of an electrically conductive material by a spatially varying EF is described by the power delivered per unit volume:

| (4) |

where P is power, V is volume, J is current density, E is the EF, and σ is the conductivity of the material. In the case of a solenoid coil (cylindrical geometry) surrounding some uniform conductive material, the rate of heat generation, , delivered by the current-carrying coil to the material of height, Lz, can be calculated from the within-coil part of Eqs. 3 and 4 as

| (5) |

where is a volume integral and m is the radial slope of the within-coil part of Eq. 3 using peak-to-peak amplitudes such that |E(r)|rms = mr/,

| (6) |

where rms is the root mean-square. According to Eqs. 4, 5, and 6, Joule heat generation increases with the square of the delivered EF amplitude. Thus, delivering higher EF amplitudes while maintaining well-controlled temperatures requires careful regulation of environmental conditions. Not only does the current-carrying solenoid coil require cooling, the cell cultures themselves require negative heat flux to the surroundings to balance Joule heating. This negative heat flux is attained by cooling the coil below the incubator temperature. A complex interplay of incubator temperature, a cooled coil temperature, and various thermal resistances (Fig. S2; Table S2) determines the steady-state temperature profile within the cell culture dishes. See Supporting Materials and Methods, Section S2, for a more complete discussion of heat transfer and expected temperature profiles (Figs. S3–S5).

A data acquisition and analysis system were used to monitor the environmental conditions within the incubator during experiments. The system can acquire data from as many as four temperature probes and two EF sensors. The data acquisition software was developed using LabVIEW (National Instruments, Austin, TX). During operation, the system collected temperature data from Opsens multichannel signal conditioners (TempSens TMS-G2-1-100ST-M1; Quebec, Canada). Data from sensors were measured every second and transmitted to the system computer via an RS-232 interface. An infrared detector was used to monitor the coil temperature. Fiber optic sensors (OTG-A-10-62ST-1; Opsens, Quebec, Canada), rather than traditional thermistors, were used to measure temperature within the cell media to avoid both inductive heating effects and any parasitic inductance and capacitance potentially contributed by thermistors. Fiber optic sensors were attached to dishes (e.g., Fig. 1 b, 2) using bone wax (Lukens #901; Surgical Specialties, Westwood, MA).

The water chiller set point and temperature were also monitored and controlled. The water temperature of the chiller was measured once per second and transmitted to the system computer using an RS-232 interface. The temperature set point of the chiller was managed by the controller software and was adjusted based on the fiber optic temperature measurements from the center of the P3 control dish. When the measured temperature deviated from the desired range, an alarm was triggered, and the set-point temperature of the water chiller was adjusted remotely via open-loop control. The status of the system was monitored remotely using a cloud service (Blynk, New York, NY). The LabVIEW software communicated with the Blynk cloud service to transmit real-time data. A Blynk cellphone app was used to receive data from the Blynk cloud and provide the status of the ongoing experiment. The app also had the ability to transmit data through the Blynk cloud to remotely adjust the chiller set point in real time to maintain stable temperature conditions throughout the 72-h experiments.

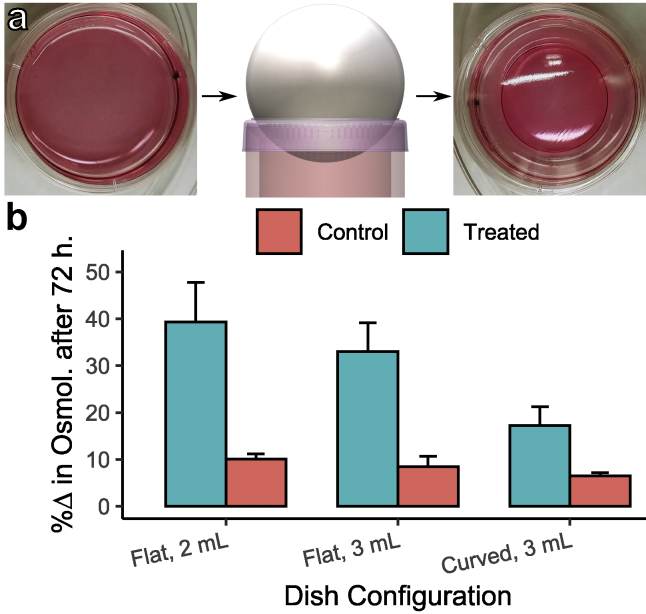

Osmolarity regulation

Cooler air near the dishes can result in accelerated loss of media because of water vapor pressure gradients (see Supporting Materials and Methods, Section S1). As a result, osmolarity can change over the course of experiments. We opted to take two preparatory steps to mitigate osmolarity changes as opposed to replacing cell media during the course of the experiment. First, we used 3 mL of media rather than the conventional 2 mL; increasing the total volume decreases the proportion of media lost. Second, we shaped the lids of all dishes by heating the lids with a heat gun, placing them on a sharpened ring mold, and depressing them while malleable with a steel ball. The end result was a curved or domed lid that is partially submerged in the media. This lid shape mitigated media loss primarily by decreasing the exposed liquid surface area and, thus, the area undergoing mass transport with the surrounding air (Fig. S1). The lid also directs condensate back into the media volume. These changes reduced the predicted osmolarity change by over 60% (Table S1). Note, increased media volume and decreased exposed surface area should not affect dissolved gas (O2, CO2, etc.) concentrations in media. According to Henry’s law, a dissolved gas in liquid is only a function of the partial pressure of the gas above the liquid and temperature, which are both unchanged by these modifications. Osmolarity measurements with a Vapro 5520 vapor pressure osmometer (Wescor, Logan, UT) were used to experimentally validate the efficacy of these regulation measures.

Human thyroid cell culture

We used a human thyroid cell line (Nthy-ori 3-1 Sigma; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) as an exemplar test cell culture system. Cells were infected with lentivirus green fluorescent protein (GFP) and selected for high expression of GFP over several cycles. Cells were maintained in 75 mL flasks in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) supplemented with 10% FBS (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific,) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific). GFP-expressing cells were passaged twice a week, and cell cultures were maintained in a 95% air and 5% CO2 incubator at 37°C. Before each 72-h experiment, cells were detached from the culture vessel with Accutase (Sigma-Aldrich) and resuspended in media at a density of 3.33 × 104 cells/mL. Three milliliters of cell suspension was placed in each 35-mm culture dish (Falcon; Corning, Corning, NY) for a plating density of 1 × 105 cells per dish. Dishes were previously coated with Poly-D-Lysine (Thermo Fisher Scientific) to enhance attachment. Dishes were incubated for 24 h to allow for attachment before 72-h experiments. Markings were made on the external part of the dishes—consistent relative to manufacturer markings—to keep the orientation of dishes consistent during treatment and imaging.

A series of cell-counting calibration experiments using different initial seeding densities ranging from 3 × 104 to 1.2 × 105 cells per dish were also performed. Cells were again detached with Accutase (Sigma-Aldrich), plated at different densities, incubated for 24 h, and then incubated for an additional 72 h. At the end of 72 h, the cell culture dishes were scanned using confocal imaging as described below, and all cells were subsequently lifted and counted using a Countess II FL Automated Cell Counter (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Final cell densities ranged from ∼100 to 1200 cells/mm2. Three series of calibration experiments were performed for a total of 56 cell counts and images. Results from these calibration experiments were used to relate imaging observables to the experimental cell counts.

In situ confocal imaging and ethidium homodimer-1 and propidium iodide staining

A unique challenge of the study design is the presence of a radial dependence in the experimental conditions. This radial dependence precluded more obvious approaches like lifting and counting all cells and informed our choice to use GFP-expressing cells. Entire dishes were imaged in situ to retain radial information, i.e., what EF-amplitude-treated cells experienced during the 72-h EMF application. Stitched images were acquired and analyzed.

At the end of experiments, sleeves with dishes were removed from the coil, and dishes were gently removed from the sleeves so as to not detach cells. Orientation information was retained using dish markings. All dishes were incubated until imaged. The dishes were mounted to the stage of a Zeiss LSM 780 laser scanning confocal microscope system (ZEISS, Oberkochen, Germany). For imaging, an EC Plan-NeoFluor 5× (ZEISS), 0.16 NA, was used. All the visible parts of the 35-mm culture dish were imaged using stitching mode, stitching 484 areas of interest with 5% overlap. The final image size was 10,726 × 10,726 pixels (px). For GFP, a 488-nm excitation wavelength, a beam splitter of 488/562 nm, and emission filters of 500–555 nm were used. Special care was taken to use nonsaturating parameters. Imaging parameters were kept constant across dishes and experiments.

In four experiments, additional ethidium homodimer-1 (EthD-1; E1169; Thermo Fisher Scientific) and propidium iodide (PI; V13241; Thermo Fisher Scientific) staining was performed after GFP imaging. For PI, at the end of EF application and 5 min before microscope imaging, 750 μL of Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium was removed from the dishes and mixed with 0.5 μL of 1 mg/mL stock solution and added back to the dish to a final concentration of 2 × 10−4 mg/mL. This procedure was used to avoid agitating all media in the dish and losing spatial information on floating or incompletely adhered cells. For EthD-1, an identical procedure was performed but for a final concentration of 0.4 μM. No additional washes were performed to avoid loss of the floating cell population. For both PI and EthD-1, a 561-nm excitation wavelength and emission filters of 578–739 nm were used. Stitching was identical.

Image processing

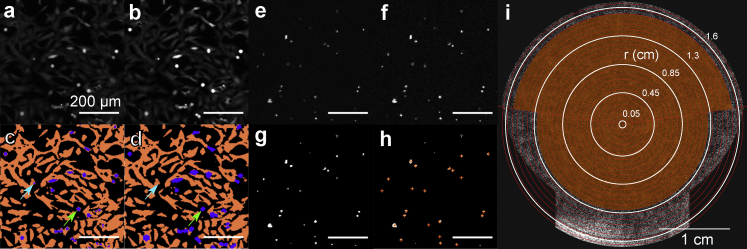

Two populations were visible in images of the GFP-expressing thyroid cells: a brighter, high-fluorescence population that might correspond to cellular debris, mitotic cells, preapoptotic cells, or a rounded cell morphology; and a dim, lower-fluorescence population that corresponds to attached cells. The primary population of interest is the attached cell population. Therefore, one goal of image processing is to segment these bright and dim px populations for downstream analyses. This segmentation was performed in three steps: contrast enhancement and denoising (e.g., Fig. 2, a and b; Fig. S7), three-level intensity thresholding (Fig. 2 c; Fig. S8), and classification error correction (Fig. 2 d; Fig. S9), outlined below. EthD-1 and PI staining images underwent a simpler procedure of contrast enhancement and denoising (Fig. 2, e and f) followed by two-level intensity thresholding (Fig. 2 g) and size thresholding (Fig. 2 h) to identify stained dead cells. See Supporting Materials and Methods, Section S3, for more details and MATLAB code (The MathWorks, Natick, MA). After processing, images were binned radially (Fig. 2 i) to encode radial information in the analysis. Edge regions and dish regions occluded by fitments were excluded. The image processing pipeline is summarized in Fig. 2.

Figure 2.

Overview of image processing pipeline. (a–d) Processing of the GFP images. (a) Raw image. (b) Contrast enhanced image. (c) Segmented image using three-level intensity thresholding before corrections. (Cyan arrow) Example of “spot” classification error. (Green arrow) Example of the “halo” classification error. (d) Segmented image after corrections, demonstrating good agreement with qualitative segmentation of (a). (e–h) Processing of PI and EthD-1 images. (e) Raw image. (f) Contrast enhanced image. (g) Segmented image using two-level intensity thresholding. (h) Counted particles or cells based on size thresholding. (i) Schematic representation of radial binning and exclusion of occluded regions on an example stitched dish image. Shaded region is included. Image has been linearly contrast enhanced ([0.01, 0.2] → [0.1, 1]) and downsampled to 20% resolution to aid visualization. To see this figure in color, go online.

Contrast enhancement and denoising

The contrast enhancement step (Fig. 2, b and f; Fig. S7; Supporting Materials and Methods, Section S3.1) was based on a morphological transform method (Supporting Materials and Methods, Section S3; (33,34)). An image, A, can be contrast enhanced by computing

| (7) |

where B is a structuring element, denotes an opening operation, and denotes a closing operation. Opening is erosion followed by dilation, whereas closing is dilation followed by erosion. The middle term on the right-hand side of Eq. 7 is a “top hat” of the original image, weighted to brighter regions, and the rightmost term is a “bottom hat,” weighted to darker regions. Morphological contrast enhancement can therefore be conceptualized as “adding” to bright regions and “subtracting” from dark regions (33). All images underwent morphological contrast enhancement using a “disk” shaped structuring element with a 3-px radius. Operations were performed using MATLAB 2019a (The MathWorks) and the imtophat() and imbottomhat() functions found in the Image Processing Toolbox. After contrast enhancement, a denoising step was performed with a 3 × 3 Wiener filter. Identical contrast enhancement and denoising was performed for all GFP, EthD-1, and PI images.

Segmentation via thresholding

To segment the contrast-enhanced GFP image, two intensity thresholds were needed: a lower threshold to separate the background and dim px population and an upper threshold to separate the bright and dim px populations (Supporting Materials and Methods, Section S3.2). The upper threshold (0.3727) was selected by applying Otsu’s method (35) with three clusters to intensity histograms drawn from a central region of all control dish images from positions P2, P4, and P5 and then taking the average of the larger of the two returned intensity thresholds. The lower intensity threshold (0.0635) was selected by first filtering the contrast enhanced and denoised image region using a 3 × 3 matrix of ones, i.e., a standard deviation filter. The filtered image was then thresholded using Otsu’s method with two clusters. The px population with intermediate standard deviation values was identified as corresponding to attached cell edges (Document S1. Supporting Materials and Methods, Figs. S1–S10, and Tables S1–S2, Document S2. Article plus Supporting Material a). An intensity threshold was then selected such that no more than 25% of the identified edges was excluded by the threshold (Document S1. Supporting Materials and Methods, Figs. S1–S10, and Tables S1–S2, Document S2. Article plus Supporting Material c). This process was repeated for all central regions of P2, P4, and P5 control dish images. The averages of the selected lower and upper intensity thresholds (Fig. S10) were used for all images (e.g., Fig. 2 c; Fig. S9).

To segment the contrast-enhanced EthD-1 and PI images, Otsu’s method was used to generate a single intensity threshold. After quantizing (see Fig. 2 g), contiguous regions larger than 3 px and smaller than 50 px were counted as stained cells (Fig. 2 h).

Classification error correction

After applying thresholds and quantizing filters to cluster the GFP image into background, dim, and bright populations, two types of classification errors were corrected (Fig. S9; Supporting Materials and Methods, Section S3.3). The first was a “halo” effect around bright regions caused by intensity drop-off such that the edges of bright regions were incorrectly classified as dim pxs. The second was a “spot” effect in the center of dim regions caused by intensity peaks. To correct the first type of error, all bright regions exceeding 8 px in size with a surrounding px population of at least 60% dim pxs were expanded by 1 px layer to fill the surrounding dim pxs (Fig. 2, c and d, green arrow), i.e., a flood fill. To correct the second type of error, all small bright regions (<8 px) that were fully enclosed by dim pxs were converted to dim pxs (Fig. 2, c and d, cyan arrow). Two passes of these corrections were performed.

Radial binning and exclusion

Data were analyzed as a function of radius by constructing radial bins or bands. For GFP images, an arbitrary number of equal annular width bands, 25, was used to divide the total image area starting from the dish center. The choice of band number results in ∼0.72-mm-wide bands. The bottom portion of the dish is occluded by a fitment and also shows irregularities. To avoid this area, only an upper portion of the band was kept from band 17 and on. The edge of the dish was also excluded because of irregularities and observed temperature differences: bands 23–25 were discarded from all analyses (Fig. 2 i). For the EthD-1- and PI-stained images, a similar binning procedure with 12 bands of ∼1.46 mm annular wide was used, with exclusion of lower regions after band 8 and a complete exclusion from band 10 onward.

Study design

In each experiment, 10 dishes were simultaneously seeded. Dishes were then randomized to either the control or treated dish sleeve. Pairs of dishes were assigned to the same height position (P1–P5). For the dishes assigned to P3, one dish is discarded, and a dish with only media is used to continuously probe temperature in the treated dish sleeve. After 24-h incubation followed by 72 h of incubation and continuous 200-kHz-induced EMF application to the treated dish sleeve, dishes were imaged and processed as described. Using data from cell-counting calibration experiments, the imaged dim px density was related to cell density using an empirical fit, shown later. Each treated dish’s radially dependent cell density was normalized to its position-matched (e.g., P2-treated versus P2 control) control dish. In four experiments, additional PI and EthD-1 staining, imaging, and image processing were performed to clarify the role of cell death in results.

Each experiment generated three replicates of dish pairs at P2, P4, and P5. Pairs of dishes assigned to P1 were discarded from all analyses because of a substantial temperature difference, discussed later. Each dish pair was treated as a single experimental observation of the effect of 200 kHz EFs. Data from Kirson et al. (3) suggest that treatment of proliferating human cells with an EF of 200 kHz and 1 V/cm results in a decrease of roughly 20 ± 10% in cell number after 72 h compared with untreated cells. Presuming an effect of this magnitude, 18 replicates are needed to obtain a conservative statistical power of 0.95 and a confidence level of α = 0.01. 12 experiments were performed using our system, resulting in N = 36 replicates. In two of these experiments (six replicates), PI staining and imaging were performed after primary imaging. In two other experiments, EthD-1 staining and imaging were performed for a total of n = 12 out of 36 replicates assessing cell death.

Statistical analysis and methods

All statistical analyses were performed in R 3.6.2. The linear fit for the experimentally measured EF amplitude was performed using the typical linear least-squares approach. The bounded exponential fit for dim px density versus cell density calibration (of the form: [dim px density] ∼ 1 − exp{β1 × [cell density] + β0}) was performed using the Gauss-Newton nonlinear least-squares approach. Initial guesses of β1 = −0.001 and β2 = 0 were provided. Bootstrapping for 95% confidence intervals was performed using the bias-corrected and accelerated approach provided in the R boot package (ver. 1.3–24). For bootstrapping, 1000 resamplings were performed after convention. Two-sample independent t-tests were performed using the base R t.test function assuming unequal variances, i.e., Welch’s t-test.

Results

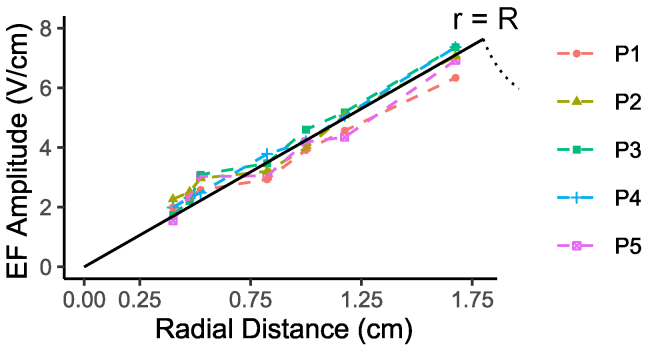

Delivery of 200 kHz EFs up to ∼6.5 V/cm pk-pk to cell cultures via induced EMFs

The EF amplitude and frequency delivered to the treated dish sleeve were measured using pickup coils (i.e., loops) of several different radii composed of insulated twisted wire pairs to minimize stray inductance. These pickup loops were hot glued to dishes, aligned centrally, and placed within the sleeve. The generated peak-to-peak voltage (Vpk–pk) was measured with a two-channel oscilloscope (Hantek6022BL; Hantek Electronic, Qingdao, China), and EF amplitude was determined by |E| = Vpk–pk/(2πr), where r is the loop radius. Results from these measurements are shown in Fig. 3 and agree with the expected linear EF amplitude profile predicted within the coil from Eq. 3. 200-kHz oscillation was also observed in all measurements, confirming the linearity of the system. Note, EF amplitudes throughout refer to pk-pk-values. We obtained a maximal EF amplitude of ∼6–7 V/cm at the periphery of the dish with a power level of 3.19 kW. The power level is a consequence of 220 volts, alternating current operation and the inductive load of the culture dishes and fixture system. We report a method of delivering EFs with a large dynamic amplitude range and well-characterized amplitude profile.

Figure 3.

Measurements of EF amplitude as a function of pickup coil radius or radial distance at different dish stack positions. The black line is a zero-intercept linear least-squares fit using data from all positions ([EF amplitude] = 4.242 × [radial distance], standard error = 0.071, adjusted R2 = 0.9902, p < 0.001). To see this figure in color, go online.

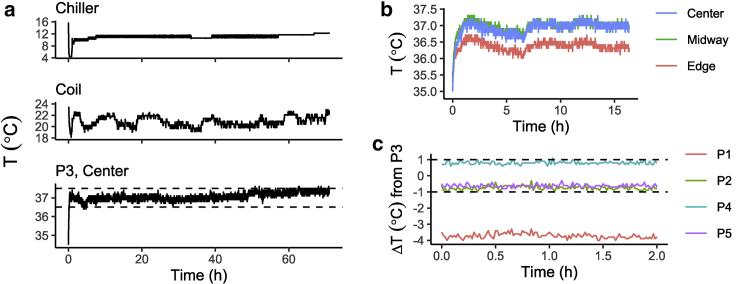

Temperature and osmolarity control during 72-h continuous 200 kHz EMF delivery

These cell cultures are typically grown at a temperature of 37°C. Extensive steps were taken to maintain this desired temperature in the treated dish sleeve because the growth rate is known to be function of ambient temperature. For this experimental setup, m = 4.242 V/cm2 (slope of the fit Fig. 3), such that 0.1 W 3.6 kWh of Joule heating is expected per dish by Eq. 5 (see Eq. S23; Supporting Materials and Methods, Section S2.4). To balance this heat generation, the coil is jacketed and actively cooled by an external water chiller to ∼22 ± 1°C, cooling the surrounding air to keep the dish at P3’s temperature at a homogeneous 37 ± 0.5°C. No inadvertent effects like Rayleigh-Bénard convection are expected using this temperature control method (Eq. S24; Fig. S6; Supporting Materials and Methods, Section S2.5). This method of temperature control was able to maintain the desired P3 dish temperature, without interruption and without fail, for all 72 h experiments. Exemplar temperature logs for the P3 fiber optic sensor, the infrared coil recording, and the chiller loop over the course of one experiment are shown in Fig. 4 a.

Figure 4.

Quantification of temperature stability and homogeneity. (a) Temperature log data for the entire duration of a single 72-h experiment from (top) the chiller water loop, (middle) the infrared detector reading of the coil, and (bottom) the fiber optic sensor placed in the center of the dish at P3. The dashed lines indicate 37 ± 0.5°C. Note the fluctuations in coil temperature and chiller set-point adjustment throughout the experiment. (b) Adjusted temperature data from three fiber optic probes placed in different positions of the dish at P3 during the first 17.5 h of an experiment. (c) Temperature data from fiber optic probes placed in the centers of dishes P1, P2, P4, and P5 expressed as a difference from a simultaneous reading of a probe in the center of the dish P3, with dashed lines indicating 0 ± 1°C. To see this figure in color, go online.

To assess the homogeneity of temperature during a stimulation experiment, measurements from different locations within the P3 dish (Fig. 4 b) (within-dish variability) and measurements from the center of different dish positions (Fig. 4 c) (between-dish variability) were taken. For the measurements between different dish positions, data are presented as a difference from a simultaneous P3 dish measurement. In Fig. 4 b, stimulation was started at time = 0. Temperature moves in tandem, demonstrating no time lag in temperature adjustment. Readings show that temperature within the dish is similar, but the edge of the dish is ∼0.5°C cooler. This was likely the result of convective heat transfer with the cooler surrounding air (see Supporting Materials and Methods, Sections S2.1–S2.4). The edges of all dishes were excluded in downstream analyses as described in Fig. 2 i to ensure the integrity of within-plate information. In Fig. 4 c, data are shown from segments of experiments that are underway and at steady-state thermal conditions. Temperature measurements from the centers of P2, P4, and P5 remained within 1°C of measurements from the center of P3 and were stable. Measurements from the center of P1, however, were several°C cooler, and so P1 was excluded from all analyses. Overall, temperature control was satisfactory and allowed us to retain most data with confidence that temperature differences were minimal and unlikely to contribute to observed differences between experimental conditions.

Osmolarity was measured after a 72-h experiment for control and treated dishes in three different dish configurations: 1) flat lid, 2 mL media; 2) flat lid, 3 mL media; and 3) curved lid, 3 mL media, to quantify the efficacy of the described mitigation methods (Fig. 5; Table S1). Three repetitions of each condition (P2, P4, and P5 from one experiment) were performed. No cells were present in the media during these osmolarity experiments. Results in Fig. 5 b are expressed as a percentage change from the measured initial average osmolarity of 314 mOsm. The combined mitigation techniques reduced the osmolarity increase in the treated condition from ∼39 to 17% and in the control condition from ∼10 to 6.5% (Eq. S10; Supporting Materials and Methods, Section S1). The reduction in osmolarity increase translated to a final osmolarity of ∼370 mOsm in the treated condition compared with ∼335 mOsm for the control condition. The mitigation was imperfect but nonetheless a marked improvement from a final osmolarity of ∼440 mOsm in the unmitigated, treated condition.

Figure 5.

Quantification of osmolarity regulation improvements. (a) Lid-shaping process with a steel ball impressing a preheated lid placed on a sharpened ring mold. Note the exposed surface area reduction in shaped lid. (b) Osmolarity changes after a 72-h experiment in different conditions and configurations with three repetitions. Error bars = ±1 SD. To see this figure in color, go online.

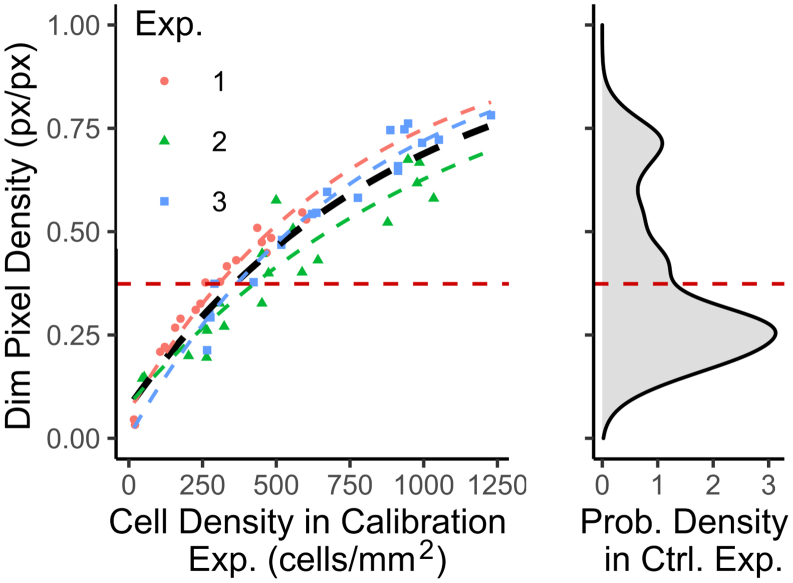

Estimating counted cell density using segmented px density obtained via in situ imaging of GFP-expressing thyroid cells

GFP images from calibration experiments were processed as described in Fig. 2. Data from these calibration experiments are expressed as total (whole dish) dim px density (px/px) versus cell count per area (cells per square millimeter) in Fig. 6 a. Grouped data corresponded well to a bounded exponential fit, allowing for the robust conversion of px densities to approximate cell densities. The bounded exponential form of the fit may arise because of changes in the size and morphology of thyroid cells as they approach confluence. To demonstrate that our “calibration curve” was valid for the range of data observed, a probability density distribution of dim px densities in all included radial bands of all P2, P4, and P5 control dishes is shown alongside the fit (Fig. 6 b). Observed dim px densities fell within the range of the calibration curve. The mean value of this distribution is also indicated. The mean dim px density is 0.374, and the corresponding cell density from the fit is 358 cells/mm2.

Figure 6.

Translating dim px density to cell density. (a) Data from the calibration experiments. Dim px density plotted versus cell density determined from cell counts. The bounded exponential fits of individual experiments are shown in colored lines. A fit with pooled data (n = 56) is shown in black ([dim px density] = 1 − exp{−0.00109 × [cell density] − 0.0784}, residual sum-of-squares = 0.1922, and Spearman’s ρ = 0.949, p < 0.001). (b) Distribution of the dim px densities in included radial bands of control dishes (n = 36 × 23). The mean value for the distribution is shown with corresponding predicted cell density using the pooled fit. To see this figure in color, go online.

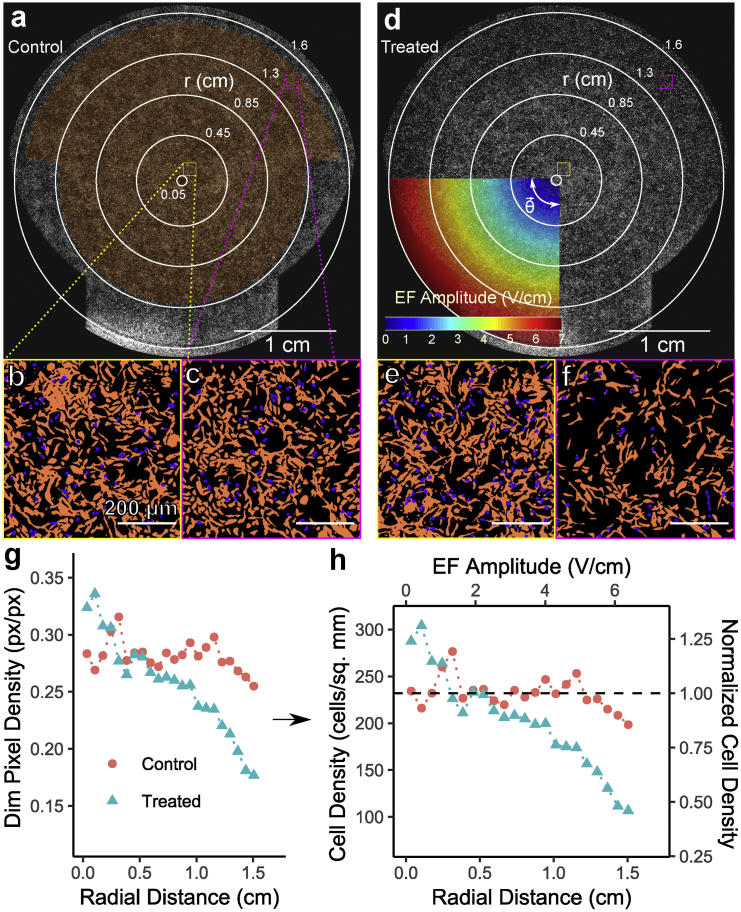

Application of 200-kHz-induced EMF for 72 h causes moderate EF-amplitude-dependent reduction in human thyroid cell density, especially at EF amplitudes exceeding 4 V/cm

A pair of control and treated culture dishes is shown in Fig. 7, a and b. The displayed images provide an example of a radially dependent cell density reduction in the treated dish. Both a central and peripheral region of the control and treated dishes are shown at 100% resolution (Fig. 7, b, c, e, and f) after the described image processing pipeline (Fig. 2, a–d) to demonstrate this radially dependent reduction in dim px density and, thus, cell density. Conversion from radially binned dim px density to a normalized cell density is also shown in Fig. 7, g and h using the fit in Fig. 6.

Figure 7.

Example of treated versus control dish and data processing and representation. (a–c) Example of (a) the control dish and zoomed, processed regions near the center, (b yellow) and near the periphery (c, magenta). The whole dish image is adjusted as in Fig. 2i for visualization. (d–f) Corresponding treated dish with the same zoomed regions. An overlay of the applied 200 kHz EMF amplitude and azimuthal direction is shown. (g and h) The radially binned data comparing control and treated dishes shown in parts (a–f). (g) Raw dim px density converted to cell density (h, left axis) via the fit in Fig. 6, and subsequently normalized to the mean of the control curve (h, right axis). To see this figure in color, go online.

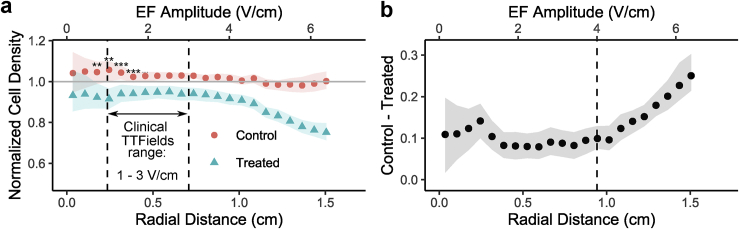

Data from all replicates (N = 36) were converted to normalized control versus treated cell density curves as shown in Fig. 7 h. We address these normalized dim px density results first and bright px density and EthD-1 and PI staining later. Average curves with bootstrapped 95% confidence intervals (CIs) are shown in Fig. 8 a. The bootstrapped difference between curves is shown in Fig. 8 b. Results demonstrate that significant differences in cell density are present throughout the dish, even at EF amplitudes thought to be subtherapeutic (<1 V/cm) (3). These differences near the center of the dish cannot be clearly attributed to EF stimulation and could potentially be the result of conditions present throughout the dish, such as the final osmolarity difference between control and treated conditions discussed in Fig. 5, mild temperature gradients (see Fig. 4; Supporting Materials and Methods, Section S2), or the alternating magnetic field (see Discussion). At higher EF amplitudes (>4 V/cm), an EF-amplitude-dependent effect emerges, and the difference between the control and treated conditions increases linearly with EF amplitude from ∼10 to 25% from 4 to 6.5 V/cm. At lower EF amplitudes in the same dish, a constant difference is instead observed, suggesting the presence of heterogeneous effects in different amplitude regimes. Note, also, that this is a magnitude cell density decrease in the treated condition, suggesting that the peripheral decrease is not a result of cell motility. A motility effect would instead cause a relative increase in central density. Overall, these results suggest a modest effect on human thyroid cell line density by 200 kHz EMF, and consistent with the literature, the effect is more pronounced at higher EF amplitudes.

Figure 8.

Summary of treatment results presented as normalized cell density curves converted from dim px densities. (a) Control versus treated curve (N = 36). Ribbons = 95% CI, determined by percentile bootstrapping method with 1000 resamplings. Point-wise t-tests: ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001. The clinically relevant “TTFields” range is shown for comparison. (b) Difference between point-wise control versus treated normalized cell densities bootstrapped in the same way. The dashed line at 4 V/cm indicates apparent regime change. To see this figure in color, go online.

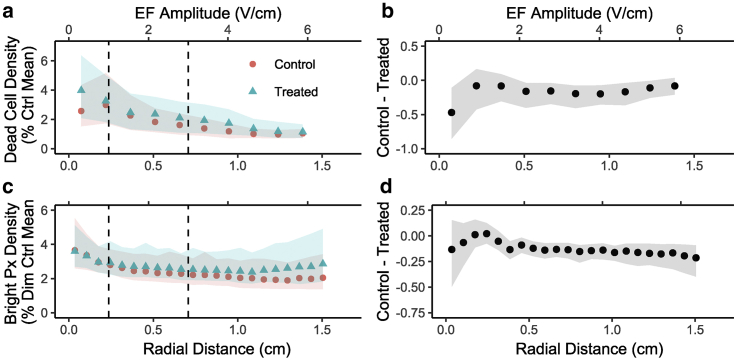

Reduction in human thyroid cell density is not sufficiently explained by cell death

The observed reduction in cell density can be explained by a reduction in proliferation, an increase in cell death, or some mixture of both mechanisms. To explore their relative roles, bright px density and dead cell density were both quantified, shown in Fig. 9. Bright px density, which may correspond to cellular debris, preapoptotic cells, mitotic cells, or a rounded cell morphology, was quantified in the same way as dim px density (Fig. 2 d) but considering the brighter (violet) segmented population. Dead cell density was quantified as described in the Materials and Methods. Data from experiments with EthD-1 and PI staining are pooled. Both bright px density (Fig. 9, c and d) and dead cell density (Fig. 9, a and b) are plotted as a percentage of the control mean values indicated in Fig. 6 to contextualize the relative contribution of bright px and cell death to the effect observed in Fig. 8. Results indicate that although the treated condition exhibits some qualitative differences in the radial curves for bright px and dead cell density, these differences are not statistically significant at the replicate number used. Moreover, as a percentage of the control means in Fig. 6, the differences are small (<1%) compared with the 10–25% differences observed in Fig. 8, a and b. Bright pxs and dead cells therefore cannot sufficiently explain the observed effects, especially at higher EF amplitudes. The observed effect appears to be antiproliferative rather than destructive or morphological based on these preliminary mechanistic explorations.

Figure 9.

Cell death and bright px density in response to treatment. (a and b) Dead cell density curves and differences constructed from pooled EthD-1 staining (n = 6) and PI staining (n = 6) results processed as described and expressed as a percent of control mean cell density (358 cells/mm2). Ribbons = 95% CI. No point-wise two-sample independent t-tests were significant. (c and d) Bright cell density curves and difference (n = 36) expressed as a percent of control mean dim px density (0.374 px/px). Again, no pointwise, two-sample independent t-tests were significant. To see this figure in color, go online.

Discussion

In this work, we detail the development of methods to deliver moderate-amplitude, intermediate-frequency EFs using induced EMFs. We were able to experimentally validate the delivery of a spatially varying EF profile and quantify substantial experimental improvements in thermal and osmolar regulation. We also report novel, to our knowledge, results of the 72-h application of continuous, 200-kHz, 0–6.5-V/cm EMF stimulation on a noncancerous, proliferating human cell line. Results were analyzed using a newly developed image processing pipeline designed specifically to characterize the in situ images necessitated by the application of a spatially varying EF “dose” profile. Our results suggest that 1) 200 kHz EMF have a moderate maximal effect (<25%) on noncancerous cells in this amplitude range, 2) the effect of 200 kHz EMF on cell density is likely antiproliferative (i.e., antimitotic) rather than destructive, and 3) the effect on cell density increases with increasing EF amplitude in a higher EF regime (>4 V/cm).

Our exploratory results corroborate and extend prior findings on the effects of “TTFields” on proliferating, noncancerous cell lines. Kirson et al. (2) reported that baby hamster kidney (BHK) fibroblasts grown in 0.1% fetal calf serum exhibited no decrease in growth rate during the 24-h application of 1.2-V/cm-pk, 100-kHz EFs. Similarly, Jo et al. (23) reported little to no reduction in cell count for normal human skin cells (CCD-986sk) after 72-h application of up to 1.5-V/cm-pk, 200-kHz EFs. Our results agree with these findings. Within and below the therapeutic EF amplitude range of 1–3 V/cm pk-pk, we found that human thyroid cells (Nthy-ori 3-1; Sigma-Aldrich) did not exhibit EF-amplitude-dependent growth reduction. We then extend prior findings by showing that for this cell line, an EF amplitude-dependent effect is observed at >4 V/cm pk-pk, which is well beyond the amplitudes used by Kirson et al. (2) and Jo et al. (23). These results suggest that there may be a range of EF amplitudes within which some noncancerous cells are unaffected. Further studies may clarify whether such an EF amplitude threshold exists for other noncancerous cell lines such as CCD-986sk.

Our findings also provide preliminary support for antimitotic mechanisms of action such as the mitotic spindle disruption reported by Giladi et al. (27) rather than cell-death-related mechanisms (i.e., autophagy or necroptosis). However, these findings do not necessarily generalize to cancerous cell lines. Indeed, it is known that the effects of alternating EFs are highly variable between cell lines (2,10,23,24,27). Future studies using cancerous cell lines are necessary to substantiate any mechanistic claims. Nonetheless, these results constitute a proof-of-concept for our device and lay the methodological and procedural foundation for future studies of glioma and other cancer cell lines. Importantly, temperature results in Fig. 4 and Fig. S3 confirm that our device can potentially operate at even greater power (and thus EF amplitudes) by simply lowering the coil temperature, providing the capability to investigate the effects of previously unexplored EF amplitudes.

More specifically, our device is well suited to begin clarifying biophysical mechanisms that can be assessed at an “end point.” Some of the proposed mechanisms can only be studied with simultaneous EF delivery and imaging (e.g., (27)), which is not feasible with the current configuration of our device. Other mechanisms, however, are easily assessed at the experimental end point. For example, Kim et al. (25) reported an autophagy effect in glioblastoma cells mediated by deactivation of the Akt2-miR29b axis. Our device can readily study radially dependent cell death, as reported via imaging observables here. Complementary genomic or transcriptomic studies can also be performed by merely lifting cells from different radial positions within the dish. Thus, we can begin to validate findings such as those reported by Kim et al. (25) using our alternative EF delivery platform. As a second example, reported DNA damage effects (22,23) can likewise be assessed by performing the appropriate assays (e.g., an alkaline comet assay) on cells lifted from different radial positions. We reiterate that our device has the unique advantage of each dish representing an internally controlled EF dose titration experiment.

Although treated interchangeably with EFs throughout, it should be noted that using induced EMFs to generate 200-kHz EFs results in an accompanying magnetic field that was not present when using previous delivery methods. At the power levels used, a vertically alternating uniform magnetic field of ∼0.6 mT is expected to be produced within the coil according to Eq. 1. This magnetic field may cause its own biological effects. Recent research suggests that high gradient and amplitude magnetic fields can affect cell division and resting membrane potentials (36). The magnetic field produced here, however, is orders of magnitude smaller than those shown to have biological effects. Moreover, because biological cells and tissues have a diamagnetic susceptibility nearly identical to that of water (37) and the magnetic field within a solenoid coil is known to be uniform (and not spatially varying), we do not anticipate that the applied magnetic field will result in any significant magnetic field gradients at interfaces. We acknowledge, however, that magnetic field effects are one possible explanation for the radially uniform level “offset” observed in Fig. 8, which cannot be ruled out at this time.

Finally, although the proposed methods offer clear improvements over previous EF delivery methods, our experimental test system is not without practical limitations. The throughput of the system is limited by the use of a single-coil solenoid as the EF applicator. Higher throughput experiments would be bottle-necked by the space requirements of the current platform, which involves a large chiller and induction heater. Another practical drawback is the power requirement; this 3.19-kW power requirement approaches the battery capacities of industry-leading electric vehicles over a single day (∼75 kWh). Future developments should attempt to miniaturize the experimental platform and introduce parallelism to enable combinatorial experiments. Alternative coil architectures, chiller loops, multicoil array designs, controllable capacitor banks, etc., are all worthwhile engineering improvements that could enhance the utility, applicability, and efficiency of this platform. These designs could be motivated by more detailed finite element modeling (FEM) of the various components of this test system, which is beyond the scope of this work.

Conclusion

We report methods to deliver EMFs to cell and tissue cultures using electromagnetic induction, which overcomes prior limitations associated with the delivery of 200-kHz EFs using contacting electrodes. The proposed strategy for inductive EMF delivery eliminates conductive heating of culture dishes and improves temperature control and regulation. Additional design enhancements of our culture dishes improved osmoregulation by mitigating media loss. We report results of stimulation of human thyroid cell line cultures with 200 kHz EMFs exceeding 3 V/cm pk-pk and as high as 6.5 V/cm. Results support a moderate antiproliferative effect, especially at EF amplitudes exceeding 4 V/cm. The effect is unlikely to be due to cell death based on secondary PI and EthD-1 staining. In summary, the 200 kHz EMF delivery method reported here is a carefully vetted and well-characterized in vitro experimental platform for future exploration of the effect of intermediate-frequency EMFs on living (and nonliving) systems.

Author Contributions

R.R. and P.J.B. conceived the study. R.R., P.J.B., and T.X.C. designed the study. R.H.P., M.G.-C., and T.P. contributed to the EF delivery and monitoring setup. R.R., H.W., and A.J.G. contributed to the cell culture methods. R.R. performed all the experiments and acquired the data. T.X.C. designed the analysis, analyzed the data, and wrote the Supporting Materials and Methods. R.Z.F. contributed to the image data analysis. T.X.C., R.R., and P.J.B. wrote the manuscript. N.H.W. gave technical advice. M.R.G. and Z.Z. provided cancer and cell biology expertise and contributed to the discussion. P.J.B. supervised the project. All authors edited the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

Light microscopy was performed at the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Microscopy and Imaging Core with the assistance of Dr. Vincent Schram and Mrs. Lynne Holtzclaw. We would also like to thank Dr. Nicole Morgan for helpful discussions.

Support for this study comes from the Intramural Research Program of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.

Editor: Anne Kenworthy.

Footnotes

Rea Ravin and Teddy X. Cai contributed equally to this work.

Supporting Material can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpj.2020.11.002.

Supporting Material

References

- 1.Cifra M., Fields J.Z., Farhadi A. Electromagnetic cellular interactions. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 2011;105:223–246. doi: 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2010.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kirson E.D., Gurvich Z., Palti Y. Disruption of cancer cell replication by alternating electric fields. Cancer Res. 2004;64:3288–3295. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-04-0083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kirson E.D., Dbalý V., Palti Y. Alternating electric fields arrest cell proliferation in animal tumor models and human brain tumors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:10152–10157. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702916104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Batash R., Asna N., Schaffer M. Glioblastoma multiforme, diagnosis and treatment; recent literature review. Curr. Med. Chem. 2017;24:3002–3009. doi: 10.2174/0929867324666170516123206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gilbert M.R., Dignam J.J., Mehta M.P. A randomized trial of bevacizumab for newly diagnosed glioblastoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014;370:699–708. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1308573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stupp R., Mason W.P., Mirimanoff R.O., European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Brain Tumor and Radiotherapy Groups. National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group Radiotherapy plus concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide for glioblastoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2005;352:987–996. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stupp R., Wong E.T., Gutin P.H. NovoTTF-100A versus physician’s choice chemotherapy in recurrent glioblastoma: a randomised phase III trial of a novel treatment modality. Eur. J. Cancer. 2012;48:2192–2202. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2012.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stupp R., Taillibert S., Ram Z. Effect of tumor-treating fields plus maintenance temozolomide vs maintenance temozolomide alone on survival in patients with glioblastoma: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2017;318:2306–2316. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.18718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ceresoli G.L., Aerts J.G., Grosso F. Tumour treating fields in combination with pemetrexed and cisplatin or carboplatin as first-line treatment for unresectable malignant pleural mesothelioma (STELLAR): a multicentre, single-arm phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20:1702–1709. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30532-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gera N., Yang A., Swanson K.D. Tumor treating fields perturb the localization of septins and cause aberrant mitotic exit. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0125269. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0125269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tuszynski J.A., Wenger C., Preto J. An overview of sub-cellular mechanisms involved in the action of TTFields. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2016;13:1128. doi: 10.3390/ijerph13111128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wenger C., Giladi M., Miranda P.C. Modeling tumor treating fields (TTFields) application in single cells during metaphase and telophase. Annu. Int. Conf. IEEE Eng. Med. Biol. Soc. 2015;2015:6892–6895. doi: 10.1109/EMBC.2015.7319977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wenger C., Salvador R., Miranda P.C. The electric field distribution in the brain during TTFields therapy and its dependence on tissue dielectric properties and anatomy: a computational study. Phys. Med. Biol. 2015;60:7339–7357. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/60/18/7339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wenger C., Miranda P.C., Korshoej A.R. A review on tumor-treating fields (TTFields): clinical implications inferred from computational modeling. IEEE Rev. Biomed. Eng. 2018;11:195–207. doi: 10.1109/RBME.2017.2765282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Davies A.M., Weinberg U., Palti Y. Tumor treating fields: a new frontier in cancer therapy. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2013;1291:86–95. doi: 10.1111/nyas.12112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bomzon Z., Wenger C., Palti Y. Quantifying the effect of electric fields in the frequency range of 100–500 khz on mitotic spindle structures. Biophys. J. 2016;110:619a. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Berkelmann L., Bader A., Ngezahayo A. Tumour-treating fields (TTFields): investigations on the mechanism of action by electromagnetic exposure of cells in telophase/cytokinesis. Sci. Rep. 2019;9:7362. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-43621-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li X., Yang F., Rubinsky B. A theoretical study on the biophysical mechanisms by which tumor treating fields affect tumor cells during mitosis. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2020;67:2594–2602. doi: 10.1109/TBME.2020.2965883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kessler A.F., Frömbling G.E., Hagemann C. Effects of tumor treating fields (TTFields) on glioblastoma cells are augmented by mitotic checkpoint inhibition. Cell Death Discov. 2018;4:12. doi: 10.1038/s41420-018-0079-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Santelices I.B., Friesen D.E., Tuszynski J.A. Response to alternating electric fields of tubulin dimers and microtubule ensembles in electrolytic solutions. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:9594. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-09323-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chang E., Patel C.B., Gambhir S.S. Tumor treating fields increases membrane permeability in glioblastoma cells. Cell Death Discov. 2018;4:113. doi: 10.1038/s41420-018-0130-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Giladi M., Munster M., Palti Y. Tumor treating fields (TTFields) delay DNA damage repair following radiation treatment of glioma cells. Radiat. Oncol. 2017;12:206. doi: 10.1186/s13014-017-0941-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jo Y., Hwang S.-G., Yoon M. Selective toxicity of tumor treating fields to melanoma: an in vitro and in vivo study. Cell Death Discov. 2018;4:46. doi: 10.1038/s41420-018-0106-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Silginer M., Weller M., Roth P. Biological activity of tumor-treating fields in preclinical glioma models. Cell Death Dis. 2017;8:e2753. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2017.171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim E.H., Jo Y., Hwang S.-G. Tumor-treating fields induce autophagy by blocking the Akt2/miR29b axis in glioblastoma cells. Oncogene. 2019;38:6630–6646. doi: 10.1038/s41388-019-0882-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Neuhaus E., Zirjacks L., Huber S.M. Alternating electric fields (TTFields) activate Cav1.2 channels in human glioblastoma cells. Cancers (Basel) 2019;11:110. doi: 10.3390/cancers11010110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Giladi M., Schneiderman R.S., Palti Y. Mitotic spindle disruption by alternating electric fields leads to improper chromosome segregation and mitotic catastrophe in cancer cells. Sci. Rep. 2015;5:18046. doi: 10.1038/srep18046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Porat Y., Giladi M., Palti Y. Determining the optimal inhibitory frequency for cancerous cells using tumor treating fields (TTFields) J. Vis. Exp. 2017:55820. doi: 10.3791/55820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Finan J.D., Guilak F. The effects of osmotic stress on the structure and function of the cell nucleus. J. Cell. Biochem. 2010;109:460–467. doi: 10.1002/jcb.22437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Radmaneshfar E., Kaloriti D., Thiel M. From START to FINISH: the influence of osmotic stress on the cell cycle. PLoS One. 2013;8:e68067. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0068067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fragniere A.M.C., Stott S.R.W., Barker R.A. Hyperosmotic stress induces cell-dependent aggregation of α-synuclein. Sci. Rep. 2019;9:2288. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-38296-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bickford R., Fremming B. Digest of the 6th International Conference in Medical Electronics and Biological Engineering. IFMBE; 1965. Neuronal stimulation by pulsed magnetic fields in animals and man; p. 112. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hassanpour H., Samadiani N., Salehi S.M.M. Using morphological transforms to enhance the contrast of medical images. Egypt. J. Radiol. Nucl. Med. 2015;46:481–489. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Soille P. Springer; Berlin, Heidelberg: 2004. Morphological Image Analysis: Principles and Applications. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Otsu N. A threshold selection method from gray-level histograms. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. 1979;9:62–66. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zablotskii V., Polyakova T., Dejneka A. How a high-gradient magnetic field could affect cell life. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:37407. doi: 10.1038/srep37407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schenck J.F. The role of magnetic susceptibility in magnetic resonance imaging: MRI magnetic compatibility of the first and second kinds. Med. Phys. 1996;23:815–850. doi: 10.1118/1.597854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.