Abstract

Purpose

Oocyte quality and reproductive outcome are negatively affected by advanced maternal age, ovarian stimulation and method of oocyte maturation during assisted reproduction; however, the mechanisms responsible for these associations are not fully understood. The aim of this study was to compare the effects of ageing, ovarian stimulation and in-vitro maturation on the relative levels of transcript abundance of genes associated with DNA repair during the transition of germinal vesicle (GV) to metaphase II (MII) stages of oocyte development.

Methods

The relative levels of transcript abundance of 90 DNA repair-associated genes was compared in GV-stage and MII-stage oocytes from unstimulated and hormone-stimulated ovaries from young (5–8-week-old) and old (42–45-week-old) C57BL6 mice. Ovarian stimulation was conducted using pregnant mare serum gonadotropin (PMSG) or anti-inhibin serum (AIS). DNA damage response was quantified by immunolabeling of the phosphorylated histone variant H2AX (γH2AX).

Results

The relative transcript abundance in DNA repair genes was significantly lower in MII oocytes compared to GV oocytes in young unstimulated and PMSG stimulated but was higher in AIS-stimulated mice. Interestingly, an increase in the relative level of transcript abundance of DNA repair genes was observed in MII oocytes from older mice in unstimulated, PMSG-stimulated and AIS-stimulated mice. Decreased γH2AX levels were found in both GV oocytes (82.9%) and MII oocytes (37.5%) during ageing in both ovarian stimulation types used (PMSG/AIS; p < 0.05).

Conclusions

In conclusion, DNA repair relative levels of transcript abundance are altered by maternal age and the method of ovarian stimulation during the GV-MII transition in oocytes.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s10815-020-01981-6) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Oocyte DNA repair, Female ageing, mRNA, Ovarian stimulation, In vitro maturation

Introduction

Prophase arrest at the germinal vesicle (GV) stage in oocytes is significant for two reasons: (I) the accumulation of mRNA transcripts and proteins is required for oocyte maturation and early embryo development [1–3] and (II) exposure to factors which could damage the structural integrity of DNA [4] with potential accumulation of DNA damage [5–7]. Intrinsic events, such as chemical instability and faulty DNA replication, and extrinsic factors, such as ionizing radiation and chemotherapy, are known to cause oocyte DNA damage [8, 9]. DNA damage in pre-ovulatory oocytes has detrimental consequences if passed on to the embryo, and may impact on embryonic development, embryo implantation and clinical outcomes in assisted reproductive technologies (ART) [10–12].

GV oocytes [13] and metaphase II (MII) oocytes [14] remain transcriptionally silent. For this reason, DNA repair mechanisms and DNA damage responses in pre-ovulatory oocytes are considered to depend on mRNA transcripts and/or pre-synthesized proteins which accumulate during oogenesis [14, 15]. Major functional classes of DNA repair genes have been identified in oocytes in mouse, monkey and human GV and MII oocytes [1, 2, 15, 16]. These include base excision repair (BER), double strand breaks (DSB) repair genes that mediate homologous recombination (HR) and non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) of DSBs, mismatch repair (MMR), nucleotide excision repair (NER) and DNA damage response (DDR) genes [17]. However, oocytes and embryos are known to exhibit differential gene expression based on their stage of development [1]. Gasca et al. [18] showed that GV oocytes possess DNA repair expression patterns traditionally seen during prophase arrest, whereas MII oocytes showed an increased expression of certain genes. Interestingly, studies analysing the repercussions of oocyte ageing have identified an overall decline in gene expression with increasing age in GV [5, 19, 20] and MII oocytes [21], with reduced expression of certain DNA repair genes such as Brca1, Mre11, Rad51 and Atm [5, 22, 23]. However, whether age plays a significant role in the relative levels of transcript abundance of DNA repair genes during the transition from GV to MII stage has not been fully addressed. Indeed, there is a massive destruction of maternal transcripts during the transition from GV to MII stage with about 30% of the total mRNA, undergoing to degradation [24]. However, little is known about the impact of ageing, and/or the type ovarian stimulation used, on transcript degradation of DNA repair transcripts during the transition from the GV to MII stage. This is of particularly relevance because the identification of the transcripts that are lost versus those that are maintained or increased could provide insights into processes occurring during oocyte maturation and early embryo development [19] as well as those essential to support DNA repair and DDR. The study by [19] concluded that the degradation of transcripts during the GV to MII transition is selective rather than a random process. Transcripts involved in processes associated with meiotic arrest at the GV-stage and the progression of oocyte maturation were dramatically degraded. Interestingly, further studies have shown that the normal pattern of degradation of maternal mRNAs during oocyte maturation is dramatically altered in oocytes from old mice and may be a contributing factor in a decline in fertility [20], affecting DNA repair and DDR.

DNA damage responses in oocytes occurs with or without cell-cycle arrest or apoptosis [9]. Fully grown and meiotically competent oocytes enter M-phase, without G2 arrest, even if DNA is damaged by measuring DDR through γH2AX [25]. Despite the induction of DNA damage, GV oocytes can retain the ability to progress to the MII stage of development [25–27]. To explain these findings, it has been hypothesised that this is caused by a lack of complete ataxia telangiectasia mutated (ATM) kinase activation and/or low ATM expression [25, 28]. However, whether DDR in oocytes is affected by ageing and the type of ovarian stimulation has not been explored. Importantly, both maternal age and ovarian stimulation are a common source of potential physiological stresses in assisted reproductive technologies (ARTs) that could affect oocyte quality and reproductive outcomes [29]. Furthermore, little is known about the effect of age and the type of ovarian stimulation on DDR during the GV to MII transition [30]. Therefore, it is important to investigate whether DDR is also affected when oocyte quality is compromised. For these reason, due to the current paucity of knowledge on the molecular mechanisms involved in GV/MII progression, particularly focused in DNA repair and DDR, this study aimed to identify and compare the relative level of transcript abundance of DNA repair genes and DDR during the GV to MII oocyte transition in relation to age and ovarian stimulation.

Material and methods

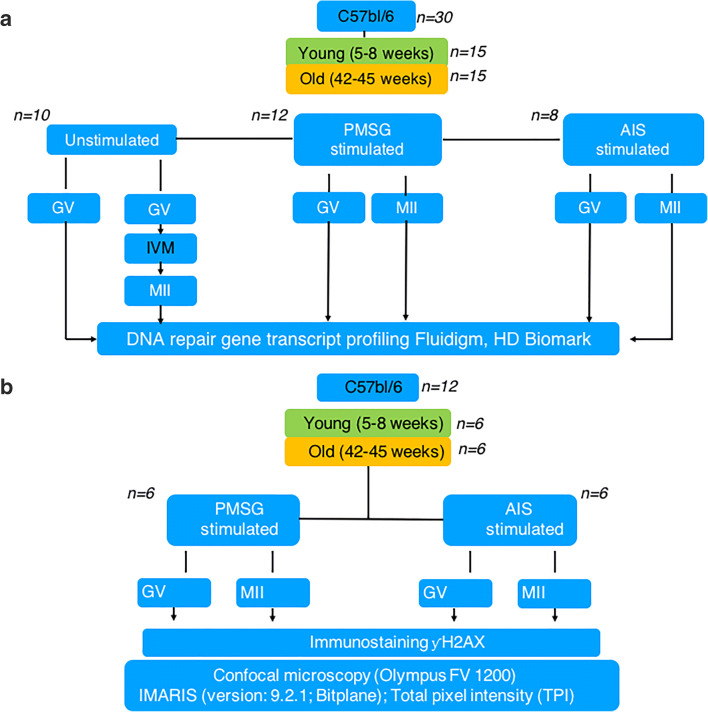

Study design

Young (5–8 weeks old, n = 15) and old (42–45 weeks old, n = 15) C57BL/6 female mice were divided into three groups: (i) unstimulated females (young: n = 5; Old: n = 5); (ii) PMSG-stimulated females (young: n = 6; old: n = 6) and (iii) AIS-stimulated females (young: n = 4; old: n = 4). GVs were collected from the ovaries of all groups but only the GVs in the unstimulated animals underwent in vitro maturation (IVM). A pool of 5 GV and 5 MII oocytes from each animal in the age groups and treatment groups were analysed for the transcript abundance of a selection of 90 DNA repair genes (Table 1; [31] using the HD Biomark system (Fig. 1). Young (5–8 weeks old, n = 6) and old (42–45 weeks old, n = 6) C57BL/6 female mice were divided into two groups for DDR analysis: PMSG stimulated and AIS stimulated (Fig. 1b).

Table 1.

DNA repair, reference and contamination genes on study

| Pathway | Number | Gene name |

|---|---|---|

| Base excision repair (BER) | 19 | Apex1, Apex2, Ccno, Lig3, Mpg, Mutyh, Neil1, Neil2, Neil3, Nthl1, Ogg1, Parp1, Parp2, Parp3, Polb, Smug1, Tdg, Ung, Xrcc1 |

| Nucleotide excision repair (NER) | 25 | Atxn3, Brip1, Ccnh, Cdk7, Ddb1, Ddb2, Ercc1, Ercc2, Ercc3, Ercc4, Ercc5, Ercc6, Ercc8, Lig1, Mms19, Pnkp, Poll, Rad23a, Rad23b, Rpa1, Rpa3, Slk, Xab2, Xpa, Xpc |

| Mismatch repair (MMR) | 11 | Mlh1, Mlh3, Msh2, Msh3, Msh4, Msh5, Msh6, Pms1, Pms2, Pold3, Trex1 |

| Double-strand break (DSB) repair | 20 | Brca1, Brca2, Dmc1, Fen1, Lig4, Mre11a, Prkdc, Rad21, Rad50, Rad51, Rad51c, Rad51l1, Rad51l3, Rad52, Rad54l, Xrcc2, Xrcc3, Xrcc4, Xrcc5, Xrcc6 |

| DNA damage response (DDR) | 15 | Atm, Atr, Exo1, Mgmt, Rad18, Rfc1, Top3a, Top3b, Xrcc6bp1, Chaf1a, H2AFX. POLM, POLQ, Tdp1, MUS81 |

| Reference genes | 3 | Actb, Gadph, Hprt |

| Contamination genes | 2 | EREG, AREG |

| Total | 95 |

Fig. 1.

Scheme of study design. a Profiling of DNA repair genes in GV and MII oocytes during age. b DNA damage response in ovarian-stimulated females during age. GV germinal vesicles, MII metaphase II oocytes, IVM in vitro maturation, PMSG pregnant mare serum gonadotropin, AIS anti-inhibin serum

Oocyte collection/handling and sample storage for genetic analysis

Unstimulated females

Oviducts and ovaries from unstimulated females (young n = 5; old n = 5) were harvested in warmed gamete handling medium (Gamete buffer, Cook Medical, Bloominton, USA) at 37 °C and GVs were collected by puncturing and gently releasing them from ovarian follicles into the medium (total GVs; n = 25). All GVs (5 per biological replicate/sample) were identified and selected regardless of cumulus coverage; GVs that were isolated from the ovary were either devoid of cumulus (nude) or had a partial or full layer of cumulus. Then, all GVs were stripped of cumulus cells mechanically after enzyme treatment with IV-S hyaluronidase (H4272, Sigma-Aldrich, Australia).

In vitro maturation of oocytes from unstimulated female mice

After oocyte collection, GV oocytes were matured in an in-house IVM medium (Supplementary Table 1), for 18 h at 37 °C/5%O2/6%CO2 in a bench-top incubator (MINC©, Cook Medical). GVs were assessed for maturation status using an inverted microscope (Olympus IX71) at × 40 magnification and oocytes in which the first polar body was extruded were determined to be mature MII oocytes. From each unstimulated female, five MII oocytes were then identified and randomly selected for genetic profiling (total MIIs; n = 25).

PMSG-stimulated females

In PMSG-stimulated females (young n = 6; Old n = 6), ovarian stimulation was performed by injecting mice with 5IU (0.1 ml) pregnant mare serum gonadotropin (PMSG, Folligon, Intervet-MSD, Bendigo) followed by 5 IU of human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG, Chorulon, Intervet-MSD, Bendigo) 48 h later. Intraperitoneal injections were administered using a 26-gauge needle mounted on a tuberculin syringe. Mice were euthanised by cervical dislocation 15–17 h after hCG administration. Oviducts and ovaries were removed and placed into handling medium (Gamete buffer, Cook Medical, USA) at 37 °C. GV oocytes were collected and selected as described above (total GVs; n = 20). Cumulus oocyte complexes (COCs) were obtained from ovarian-stimulated female mice by ampullary puncture and the cumulus stripped from these complexes, as described above, to retrieve the MII oocytes. Five MIIs oocytes were identified and randomly selected for the relative transcript abundance analysis in each biological replicate (n = 4; total MIIs; n = 20).

AIS-stimulated females

In AIS-stimulated females (young n = 4; old n = 4), the protocol for ovarian stimulation was performed as described by [32]. In brief, mice were injected with 0.1 ml of anti-inhibin alpha goat serum (AIS; Central Research Co., Tokyo, Japan; Lot #920530), followed by a second injection of 0.1 ml of AIS 24 h later. Mice were then injected 48 h later with 5 IU of human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG, Chorulon, Intervet-MSD, Bendigo, Australia). All injections were administered intraperitoneally, using a 26-gauge needle on a tuberculin syringe. Mice were killed by cervical dislocation 15–17 h after the hCG trigger. Oviducts and ovaries were harvested in handling medium (Gamete buffer, Cook Medical, USA), as described above, and GV (total GVs: n = 20) and MII oocytes (total MIIs: n = 20) were then selected for the relative level of transcript abundance analysis.

Sample collection and storage

A maximum time of 20 min was allowed from tissue collection until oocyte were collected. GV and MII oocytes from each study group were pooled as either 5 GV or MII oocytes and loaded into labelled DNase, RNase-free 0.2 ml Eppendorf tubes prefilled with 2 μl of lysis buffer for RNA extraction (Single Cell-to-CT Kit, Ambion, Life Technologies, USA). These tubes were then stored at – 80 °C for further analysis.

Relative level transcript abundance analysis

cDNA synthesis and real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction

Total RNA was extracted from each pool of oocytes for the relative transcript abundance analysis using the Ambion Single Cell-to-Ct™ kit (Life Technologies, USA). cDNA was synthesized from the extracted RNA by reverse transcription using a thermal cycler (Veriti 96 Well Thermal cycler, Applied Biosystems, USA) (25 °C for10 min; 42 °C for 60 min; 85 °C for 5 min). cDNA samples (5 μl each) were then diluted in nuclease-free TE buffer and loaded into a labelled 96-well PCR plate that was sealed and delivered to the Monash Health Translation Precinct Medical Genomics Facility, Clayton (Victoria, Australia). All cDNA samples were quality checked by qPCR on the ABI 7900HT Fast Real-Time PCR system (Applied Biosystems, Life Technologies ©, California, USA) using SYBR primers for the reference gene Gadph. Ninety-five mouse Taqman Assays® (Roche Molecular systems, USA) were selected from the Single Cell Genomics Taqman Library (Supplementary Table 2), including three reference genes (Actb, Gadph, Hprt) and two cumulus-specific genes for tagging contamination (EREG, AREG; [33]. All TaqMan® Gene Expression Assays (20X mix of unlabeled forward and reverse PCR primers and FAM™ dye-labelled TaqMan® MGB probe) were pooled and combined with TaqMan® PreAmp Master Mix. To each 1.25 μl cDNA sample, 3.75 μl of the TaqMan® PreAmp Master Mix preparation was added and the mixture was pre-amplified for 14 cycles. The reaction products were combined with 20X Taqman® Gene Expression Assay and 2X Taqman® Gene Expression Master Mix in a 96.96 Dynamic array Integrated Fluidic Circuit (IFC). ‘No template control’ (NTC) was included in the chip to detect contamination in controls/reagents. Real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) was performed using the Fluidigm BioMark HD system (Fluidigm, California, USA) and a GE 96x96 Standard v2 Biomark Protocol.

Real-time PCR data analysis

The RT-qPCR output was processed using the Fluidigm Real-Time PCR analysis software (v4.3.1, Fluidigm, California, USA). Samples were included if they had a minimum of three replicates and were free of cumulus cell contamination. For each study group, GV and MII oocytes from the old female study groups (designated as ‘test’) were matched against respective GV and MII oocytes from young females (designated as ‘control’). We also compared GV and MII oocytes from unstimulated females to stimulated females (PMSG/AIS females). Data obtained as raw cycle threshold values (Ct values) were analysed using the comparative CT method [34]. Target gene-specific Ct values were normalized using the geometric mean of the Ct values of three reference genes (Actb, Gapdh, Hprt), acting as endogenous reference and Delta Ct values (ΔCT) and Delta-Delta Ct (ΔΔCT) value were generated. Relative level of transcript abundance was calculated, including 2^-ΔΔCT and 2^-ΔΔCT + standard deviation (SD) calculations respectively, and statistical analysis was conducted using Q-Base+ software (QBase+, Biogazelle, Switzerland).

DNA damage response and immunocytochemistry

Fixation of GV and MII oocytes was conducted immediately after oocytes were collected and denuded of the cumulus mass from cumulus-oocyte complexes (COC’s). Oocytes were fixed in 3.5% (v/v) paraformaldehyde for 1 h and permeabilised in a solution of 0.5% Triton X-100 in PBS for 15 min at room temperature (RT). Oocytes were then blocked in 3% BSA/PBS for 1 h at 37 °C and incubated with anti-γH2AX (SC517348, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX, USA) diluted 1:400 in 1% BSA/PBS for 1 h at 37 °C. After primary antibody binding, oocytes were washed in 1% BSA/PBS and incubated with Alexa Fluor 488 conjugated secondary antibody (Thermo Fisher Scientific) diluted 1:1000 in 1% BSA/PBS at 37 °C for 1 h. Oocytes were mounted on Menzel Glӓser microscope slides (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and counterstained with DAPI (Prolong Diamond anti-fade mounting with DAPI, Life technologies, Thermo Fisher Scientific). Fluorescence intensity was assessed using confocal laser scanning microscopy (Olympus FV1200), with all imaging parameters consistent between treatment groups including proper negative controls for each run. The confocal Z stacking function was used to record the dimensions from pole to pole of the entire pronucleous of each GV oocytes and metaphase plates of MII oocytes using a × 40 objective air 0.95NA. Each experiment consisted of a minimum of three biological replicates, with a minimum of 20 oocytes analysed per group. Images were collected and imputed into Imaris software (version: 9.2.1; Bitplane) and FIJI software (version: 2.0.0-rc-69/1.52n; ImageJ) for analysis. Green and blue signals in the nucleus were segmented using the surfaces tool in Imaris software, then segmented surfaces were selected to obtain the mean of the sum of the intensity, which represent the total pixel intensity across the whole pronucleous/metaphase plates analysed. Negative controls were segmented as described above using both the blue and green channel to calculate the total intensity to then subtract their value for each oocyte analysed. FIJI software was used to produce microscopic images as well as and Z stack videos.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 7 (GraphPad, San Diego, CA, USA) and QBase+ for the relative transcript abundance analyses. GV and MII oocytes derived from the same animal were considered paired data. Data distribution was evaluated using the D’Agostino and Pearson omnibus normality test to derive the mean, standard deviation (SD) and standard error of mean (SEM). Normally distributed data was analysed using a two-tailed student’s T test or ANOVA with multiple comparisons accounted for using the Bonferroni post-hoc method. Non-parametric variables were compared using the Mann–Whitney U-test. Mann–Whitney was used to compare the differences in relative levels of transcript abundance for individual genes in GV and MII oocytes for the different study groups. A p value < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant in all groups being tested. An expression-based heat-map and hierarchical cluster analysis was performed using web-based ClustVis software [35].

Results

Oocyte collection and response to ovarian stimulation during ageing

Unstimulated, PMSG- and AIS-stimulated females

A total of 25 C57BL6 female mice (n = 12 young [5–8 weeks] and 13 old [42–45 weeks]) were included for genetic analysis. Those individual females that were not included in the study consisted of one unstimulated young female with no oocytes retrieved, 4 females (2 young and 2 old) with failed PMSG stimulation determined by the absence of COC.

A significantly higher number of oocytes was collected from the PMSG- and AIS-stimulated females compared to the unstimulated group (unstimulated: n = 229; PMSG: n = 314; Table 2; p < 0.05). Ageing was directly associated with a significant decrease in the total number of oocytes collected in the unstimulated group: on average, 21.60 oocytes were obtained per old mouse compared to 30.25 per young mouse (Supplementary Table 3). However, there was no difference in the oocyte stages collected between the two age groups (p > 0.05). No MII oocytes were recovered from the unstimulated mice.

Table 2.

Summary table of oocyte collection results in young and old mice in study groups comparing unstimulated, PMSG-stimulated and AIS-stimulated females

| Oocyte characteristics | Unstimulated | PMSG | AIS | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Females (n) | 4 | 4 | 4 | |

| Young oocytes (n) | 121 | 218 | 268 | |

| Females (n) | 5 | 4 | 4 | |

| Old oocytes (n) | 108 | 152 | 166 | |

| Total number of oocytes | 229* | 314* | 434* | < 0.0001 |

Young: female mice 5–8 weeks old. Old: female mice 42–45 weeks old. PMSG pregnant mare serum gonadotropin, AIS anti-inhibin serum

*Statistically significant differences. N/A not applicable statistical testing

Unstimulated females and IVM

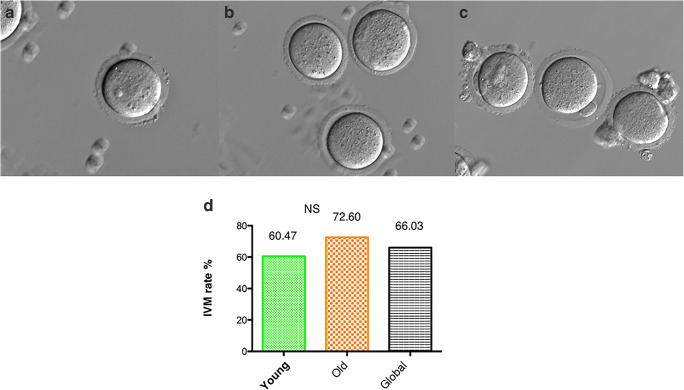

The number of GV oocytes collected from unstimulated young (n = 86) and old (n = 73) mice was not different (Supplementary Table 4; p = 0.2187). There were also no statistical differences in the number of in vitro-matured MII oocytes from young and old groups (young: 60.47%; old: 72.60%), with an overall rate of 66.03% (Fig. 2; p = 0.131; Supplementary Table 4).

Fig. 2.

Comparison of oocyte stages in IVM and IVM rates between age groups. a Germinal vesicle (young: n = 86; old: n = 73). b Metaphase I oocytes. c Metaphase II oocytes (young: n = 52; old: n = 53). d IVM rates in young and old (young: 60.47%; old: 72.60%) unstimulated females and global IVM rate (66.03%). Young: female mice 5–8 weeks old, old: female mice 42–45 weeks old. IVM in vitro maturation rate, NS no statistical differences; Fisher exact test

Effect of age on relative transcript abundance in GV to MII transition using IVM for oocytes from unstimulated females and hierarchical cluster analysis

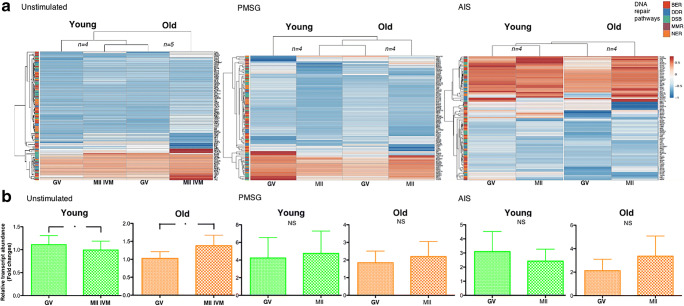

The overall profile of the relative level of transcript abundance was different in MII IVM oocytes compared to GVs. DNA repair genes showed a significant decrease in total relative transcript levels in MII IVM oocytes compared to GVs in young-unstimulated mice, but showed a significant increase in total relative transcript abundance level in older females (young-unstimulated GV: 1.11; IVM-MII: 0.99; p < 0.01; old-unstimulated GV: 1.02; old IVM-MII: 1.37 p < 0.01; Fig. 3). The genes POLQ, Ercc6 and Apex1 showed a significant higher relative transcript abundance level during the transition to MII, and 14 genes showed a significant lower relative transcript abundance in young females (BER: 2 genes; DDR: 5 genes; DSB: 4; NER: 2; MMR: 1 gene (p < 0.05; Table 3). A different pattern was observed in older females with 12 genes showing a significant higher relative level of transcript abundance (BER: 5; MMR: 1; NER: 3; DSB: 2; DDR: 1) and only 7 genes showing lower transcript levels (DDR: H2AFX, Atr; DSB: Top3b; MMR: Mlh1; NER: Ercc1, Ercc5, Ccnh) (p < 0.05; Table 3). During the GV-MII transition, the genes Mlh1 (MMR pathway), Top3b (DSB pathway) and H2AFX (DDR pathway) were the only genes that showed a significantly lower relative transcript abundance levels in both young- and old-unstimulated females (p < 0.05; Table 3; Supplementary Table 5 for excluded genes).

Fig. 3.

Relative DNA repair gene transcript abundance patterns in GV and MII oocytes from unstimulated, PMSG-stimulated and AIS-stimulated young/old females. a Heat-map/hierarchical cluster analysis of total relative DNA repair transcript abundance in unstimulated females, PMSG-stimulated females and AIS-stimulated females. b Relative transcript abundance of GV and MII oocytes from in unstimulated females, PMSG-stimulated females and AIS-stimulated females in fold changes as mean ± SEM. Young: female mice 5–8 weeks old, old: female mice 42–45 weeks old. IVM in vitro maturation rate, PMSG pregnant mare serum gonadotropin, AIS anti-inhibin serum. DNA repair pathways: base excision repair (BER); double strand break (DSB); mismatch repair (MMR); nucleotide excision repair (NER); DNA damage response (DDR) * Significant differences (p < 0.05; paired t test). NS no statistical differences, SEM standard error of the mean. Please see Figure 3 supplementary file for heatmaps of increased resolution

Table 3.

Genes with significantly increased or decreased gene expression between study groups during GV-MII transition

| GV MII transition | Increased gene transcript abundance | Decreased gene transcript abundance | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DNA repair pathway | BER | DDR | DSB | MMR | NER | BER | DDR | DSB | MMR | NER |

| Young unstimulated | Apex1 | POLQ | Ercc6 |

Mutyh Parp2 |

MUS81 Exo1 Top3b Mgmt H2AFX |

Xrcc5 Prkdc Brac1 Dmc1 |

Mlh1 |

Lig1 Ercc1 |

||

| Old unstimulated |

Ogg1 Apex1 Neil3 Mpg Ung |

Rad52 Rad51b Rad23b |

Msh3 |

Brip1 Ddb2 Atxn3 |

Atr |

H2AFX Top3b |

Mlh1 |

Ercc1 Ercc5 Ccnh |

||

| Young PMSG stimulated | POLM | Rad51b |

Mms19 Msh3 Msh4 |

Ddb2 Ercc3 Atxn3 |

H2AFX | |||||

| Old PMSG stimulated |

Apex1 Polb |

Rad52 |

Msh3 Msh4 Pold3 |

Brip1 | Neil1 | H2AFX | Dmc1 |

Mlh3 Msh2 |

Pnkp | |

| Young AIS stimulated |

Apex1 Ogg1 Ung Parp2 |

Rad50 Rad23a Xrcc3 |

Msh3 | Ddb2 | H2AFX | |||||

| Old AIS stimulated |

Polb Mpg Xrcc1 Ung Neil2 |

POLM TDP1 MUS81 |

Rad50 | Pold3 |

Mms19 Ercc3 Ercc6 Atxn3 Ddb2 |

Atm | ||||

Young: female mice 5–8 weeks old. Old: female mice 42–45 weeks old. PMSG pregnant mare serum gonadotropin, AIS anti-inhibin serum. DNA repair pathways; base excision repair (BER); double strand break (DSB); mismatch repair (MMR); nucleotide excision repair (NER); DNA damage response (DDR)

GV-MII transition (GV/MII): genes with differentially transcript levels represent the relative transcript abundance in the GV oocytes divided by the relative abundance of the same gene in MII oocytes. All genes were statistically different (p < 0.05; paired T test)

An effect of age was observed in unstimulated GV oocytes (Table 4) with 10 genes showing significant decreased (p < 0.05) transcript levels in GV oocytes from old females compared to those from young females (BER: Polb; DDR: Exo1; DSB: Rad51, Rad23b; MMR: Mlh3, Pold3; NER: Ccnh, Ercc2, Mms19, Rpa1). In MII IVM oocytes from old females, 16 genes showed high relative transcript abundance levels when compared to those from young females, while two genes showed low transcript levels in oocytes from old females (Table 4, Fig. 4; p < 0.05). Total relative transcript abundance showed no significant changes with age in GV or IVM-MII oocytes (Fig. 4; p > 0.05).

Table 4.

Genes with significantly increased or decreased gene expression during age between study groups

| Age effect (Old/Young) | Increased gene transcript abundance | Decreased gene transcript abundance | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DNA repair pathway | BER | DDR | DSB | MMR | NER | BER | DDR | DSB | MMR | NER |

| Unstimulated GV oocytes | Polb | Exo1 |

Rad51 Rad23b |

Mlh3 Pold3 |

Ccnh Ercc2 Mms19 Rpa1 |

|||||

| IVM-MII oocytes |

Smug1 Neil3 Ung |

Exo1 TPD1 Xrcc6 Rfc1 |

Rad21 Rad51d Mre11a |

Pms1 Msh3 |

Xpa Ercc2 Lig1 Brip1 |

Ercc3 Ercc5 |

||||

| PMSG-stimulated GV oocytes |

Parp1 Apex2 Ccno |

Top3b H2AFX Xrcc6bp1 Chaf1a |

Xrcc3 Xrcc5 Xrcc6 Rad54l Rad51d Rad51 |

Pms2 |

Rpa1 Slk Pnkp Lig1 Xpc Poll Ercc2 |

|||||

| PMSG-stimulated MII oocytes |

Nthl1 Apex2 Neil2 |

Exo1 Top3a Top3b TDP1 Atm PolM Polq |

Bcra1 Bcra2 Rad51 Rad23a Mre11a Xrcc2 Dmc1 |

Ddb1 Ercc6 Slk Ercc3 |

||||||

| AIS-stimulated GV oocytes | Atr |

Ccnh Rpa3 |

||||||||

| AIS-stimulated MII oocytes | PolQ | Dmc1 |

Lig3 Parp2 |

Msh3 | Rpa1 | |||||

Young: female mice 5–8 weeks old. Old: female mice 42–45 weeks old. PMSG pregnant mare serum gonadotropin, AIS anti-inhibin serum. DNA repair pathways; base excision repair (BER); double strand break (DSB); mismatch repair (MMR); nucleotide excision repair (NER); DNA damage response (DDR)

Old/young: genes with differentially transcript levels represent the relative transcript abundance in oocytes from old females divided by the relative transcript abundance of the same gene in oocytes from young females. All genes were statistically different (p < 0.05; Mann–Whitney test)

Fig. 4.

Relative transcript abundance and heat-map/hierarchical cluster analysis of DNA repair genes in GV and MII oocytes from young and old unstimulated, PMSG stimulated and AIS females. a Total relative transcript abundance in GV and MII oocytes from young and old unstimulated, PMSG stimulated and AIS females in fold changes as mean ± SEM. * Statistically significant differences (p < 0.05; Mann–Whitney test). Relative transcript abundance included the total analysis of 83 genes showing transcript abundance levels across study groups. b Heat-map/hierarchical cluster analysis of genes with statistically significant increased and decreased relative levels of transcript abundance in GV and MII oocytes from young and old unstimulated, PMSG stimulated and AIS females (p < 0.05; Mann–Whitney test). Young (female mice 5–8 weeks old), old (female mice 42–45 weeks old). Base excision repair (BER); double strand break (DSB); mismatch repair (MMR); nucleotide excision repair (NER); DNA damage response (DDR). SEM standard error of the mean. Statistically significant differences (p < 0.05; Mann–Whitney test). Please see Figure 4 supplementary file for heatmaps of increased resolution

Effect of age and stimulation type on relative transcript abundance and hierarchical cluster analysis

GV to MII transition in PMSG-stimulated females

In young PMSG-stimulated female mice, there were no significant changes in total relative transcript abundance during the GV to MII transition in oocytes from young and old females (Fig. 3, p > 0.05). However, young females showed an increase in relative levels of transcript abundance for 8 DNA repair genes (DDR:1; DSB: 1; MMR: 3; NER: 3) during the GV-MII transition with only the gene H2AFX (DDR pathway) showing decreased relative levels of transcript abundance (Table 3; p < 0.05). In MII oocytes from old females, there was a significant increase in relative levels of transcript abundance for 7 DNA repair genes (BER: 2; DSB: 1; DDR: 3; NER: 1) compared to GV oocytes, including 6 genes showing a decreased relative transcript abundance levels; BER: 1; DDR: 1; DSB: 1; MMR: 2; NER: 1 (Table 3, p < 0.05). During the transition from GV to MII oocyte, a significant decrease in relative transcript abundance levels of the H2AFX gene (DDR pathway) was observed in both young- and old-stimulated females (Table 5; Fig. 4c).

Table 5.

Effect of age and ovarian stimulation type on DNA damage response in GV and MII oocytes

| Combined PMSG- and AIS-stimulated females | |||

| Group | Young | Old | p value |

| GV (n) | 52 | 46 | |

| Total pixel intensity (AU) | 8.02 × 106 (0.57 × 106) | 1.36 × 106 (0.89 × 106) | < 0.0001 |

| MII (n) | 31 | 35 | |

| Total pixel intensity (AU) | 1.22 × 106 (0.18 × 106) | 0.76 × 106 (0.17 × 106) | 0.0037 |

| PMSG- and AIS-stimulated females | |||

| Group | PMSG | AIS | p value |

| GV (n) from young females | 24 | 28 | |

| Total pixel intensity (AU) | 5.95 × 106 (0.88 × 106)a | 9.80 × 106 (0.58 × 106)c | 0.0005 |

| MII (n) from young females | 15 | 16 | |

| Total pixel intensity (AU) | 0.96 × 106 (0.37 × 106)b | 1.40 × 106 (0.15 × 106)d | 0.0098 |

| GV (n) from old females | 21 | 25 | |

| Total pixel intensity (AU) | 1.11 × 106 (0.30 × 106) | 1.58 × 106 (0.35 × 106) | 0.3331 |

| MII (n) from old females | 16 | 19 | |

| Total pixel intensity (AU) | 0.30 × 106 (0.09 × 106) | 0.94 × 106 (0.23 × 106) | 0.1911 |

Young: female mice 5–8 weeks old. Old: female mice 42–45 weeks old. PMSG pregnant mare serum gonadotropin, AIS anti-inhibin serum, GV germinal vesicle oocytes, MII metaphase II oocytes, n number of either GV or MII analysed in study, AU arbitrary units. Mean (SEM)

a, b, c, dStatistically different within row and columns for either GV or MII oocytes. ANOVA and post hoc tests, unpaired T test or Mann–Whitney were applied accordingly with data distribution

Values represent mean ± (standard error of the mean; SEM)

Total relative transcript abundance level in both GV and MII oocytes decreased with age (young PMSG GV: 4.32; old PMSG GV: 1.84; p = 0.024; young PMSG MII: 4.76; old PMSG MII: 2.19; p = 0.017; Fig. 4), and there was a decrease in the relative transcript abundance levels for all DNA repair pathways with age (Fig. 4; Table 4; p < 0.05). Relative transcript abundance analysis of GV oocytes revealed a significant decrease in relative transcript abundance of 21 DNA repair genes in old GV oocytes compared to young GV oocytes (Table 4, Fig. 4; p < 0.05). Similarly, MII oocytes from old females showed 21 genes with decreased relative transcript abundance levels compared to those in young MII oocytes (p < 0.05). DNA repair pathways such as BER (GV: 3; MII: 4), DSB (GV: 5; MII: 6), MMR (GV: 1; MII: 0), NER (GV: 8; MII: 5) and DDR (GV: 4; MII: 8) in GV and MII oocytes from old females showed genes with reduced relative transcript abundance (Fig. 4b). Interestingly, in MII oocytes, important genes from the DSB and DDR pathways such as Bcra1/2, Atm, Mre11a, Rad51 and Dmc1 showed a reduced relative levels of transcript abundance (Table 4, Fig. 4b; p < 0.05; Supplementary Table 5 for excluded genes).

Effect of age and stimulation type on relative transcript abundance and hierarchical cluster analysis

GV to MII transition in AIS-stimulated females

In young and old AIS-stimulated mice, no differences were observed in the total relative transcript abundance of DNA repair genes, but a trend was observed towards an increase in total relative transcript level during the GV-MII transition in old females (young AIS GV: 3.12; young AIS MII: 2.44; p = 0.137; old AIS GV: 2.12; old AIS MII: 3.36; p = 0.052; Fig. 3). The GV-MII transition in young females was associated with an increase in relative transcript abundance of 9 genes (BER: 3; DSB: 3; NER: 2; MMR: 1) and one gene with reduced relative levels of transcript abundance (DDR: H2AFX; Table 3; p < 0.05). However, no significant difference was observed in the GV/MII ratio for old AIS-stimulated females (Fig. 3; p = 0.052). Old females showed a significant increase in relative transcript abundance for 15 genes (BER: 5; DDR: 3; DSB: 1; NER: 5; MMR: 1) and a significant decrease in transcript abundance for Atm (DDR pathway; p < 0.05; Table 3).

In AIS-stimulated females, the total relative transcript abundance of DNA repair genes in GV oocytes was significant decreased with age while MII oocytes showed increased relative levels of transcript abundance that were not statistically significant (young GV AIS: 2.95; old AIS GV: 2.02; p = 0.039; young AIS MII:2.02; old AIS MII:3.19; p = 0.08; Fig. 4). Interestingly, this age effect showed that GV and MII oocytes had fewer genes with significant changes in AIS-stimulated females compared with unstimulated and PMSG-stimulated females. In young AIS-stimulated females, only 3 genes showed decreased relative transcript abundance (DDR: Atr; NER: Ccno, Rpa3), whereas in old AIS-stimulated females, 5 genes showed a decrease in transcript levels and two genes showed significantly increased transcript levels (Table 4; p < 0.05; Supplementary Table 5 for excluded genes).

DNA damage response in GV and MII oocytes from young and old females

From our observation that DNA repair genes showed an overall increased relative transcript abundance in MII oocytes from old females, we examined the interaction between basal levels of DDR, age and stimulation type in GV and MII oocytes.

Irrespective of stimulation type, GV oocytes from old females had an 82.9% decrease in total pixel intensity (TPI) of γH2AX-labelling than GV oocytes from young females (Table 5, Fig. 5; p < 0.0001). MII oocytes from old females, however, showed a decrease of 37.5% in TPI compared to MII oocytes from young mice (Table 5, Fig. 5; p < 0.0037), demonstrating a significant decrease in the basal DDR of both GV and MII oocytes with age respectively. Interestingly, an increased DDR activity was observed in both GV and MII oocytes from young females stimulated with AIS when compared to young PMSG-stimulated female (Table 5, Fig. 5; p < 0.05). However, despite a similar results observed in old females, PMSG and AIS stimulation did not result in a significant effect on the DDR activity in either GV or MII oocytes (Table 5, Fig. 5; p > 0.05).

Fig. 5.

DNA damage response in GV and MII oocytes according to age and type of stimulation. a Decreased DNA damage response in GV and MII during ageing. b DNA damage response according to type of stimulation and ageing. c Microscopy images of nuclei of GV oocytes and metaphases of MII oocytes for nuclear staining (DAPI) and immuno-labeliing of γH2AX.Young; females mice 5–8 weeks old, old: female mice 42–445 weeks old. PMSG pregnant mare serum gonadotropin, AIS anti-inhibin serum, hCG human chorionic gonadotropin, GV germinal vesicle oocyte, MII metaphase II oocyte. *a, b, c, d, represent statistically significant differences (p < 0.05; Mann–Whitney test). NS not statistically significant. Scale bar represent 10 μm. Microscopy images show the sum of the intensity a z stack projection representing the total pixel intensity in arbitrary units (AU)

Discussion

The transition from the GV to MII stage in oocytes has been widely recognised as a transcriptionally quiescence biological process, involving a massive degradation of maternal transcripts that allows the resumption of meiosis. Our study shows that age and type of stimulation all impact on the transcript abundance of genes in DNA repair pathways during the transition from the GV to MII oocyte stages. Furthermore, we have observed that most of DNA repair gene transcripts are maintained, but that they show either an increase or decrease in abundance associated with age. Surprisingly, we also observed an increase in the DNA damage response, as measured by γH2AX, with ovarian stimulation of higher yield using AIS compared to PMSG. However, a decreased DDR expression with age was observed which requires further exploration to understand the molecular mechanism behind DNA repair and DNA damage response in mammalian oocytes.

Ovarian stimulation techniques are commonly used in human ART to increase the number of oocytes available for IVF and to increase the number of embryos available for transfer [29, 36]. However, the consequences of this approach on oocyte quality, corpus luteum function and endometrial receptivity are still not entirely understood [29]. Evidence from animal models suggest that overstimulated ovaries produce poor quality oocytes [37, 38] and human studies have reached a similar conclusion [29, 37, 38]. Molecular changes associated with the reduction in oocyte quality are still poorly understood and need to be more clearly characterised to understand their effect on oocyte quality.

In our study, the number of oocytes collected from the stimulated mice exceeded those collected from the unstimulated groups, reflecting the positive influence of hormonal stimulation on oocyte yield. The reduced yield of oocytes per mouse seen in the older groups demonstrate and confirm the negative effect of age on ovarian response and retrieval in animal models [39, 40], which are also reflected in clinical IVF settings [41]. Differences in the numbers and stage oocytes collected from the unstimulated and stimulated young and old mice were also observed. Double the number of ovulated MIIs were identified in younger PMSG-stimulated females and up to three times more MII oocytes in AIS young mice. Although, better implantation rates have been documented with embryos produced from unstimulated females compared to stimulated females in mice [38], the effect of ovarian stimulation on oocyte quality remains unknown. Also, the use of AIS stimulation to obtain a higher yield of oocytes for IVF [32, 42] has not been compared to the standard PMSG stimulation for IVF and embryo production, nor have the reproductive outcomes been extensively compared. Therefore, the potential for detrimental effects on oocyte quality and subsequent embryo development requires further research.

Total relative DNA repair gene transcript abundance did not change significantly in young MII oocytes compared to GV oocytes from young-stimulated females, but a significant reduction in relative transcript abundance was observed in unstimulated females. This may be attributed to the normal degradation of maternal transcripts during the GV to MII transition [19] involves some degradation of DNA repair transcripts in unstimulated females that is not required in stimulated females, although the variation observed in our results may be considerably reduced with a larger sample size. These results also mirrored a previous study that reported silencing of genes during oocyte maturation (10,892 genes in GVs as against 5633 in MIIs) [43], although the effect of ovarian stimulation was not studied. In our study, a total increase in the transcript abundance of DNA repair genes during the GV-MII transition was observed in unstimulated older mice with increases in stimulated female mice that were not statistically significant. These observations suggest that in young mice, where the incidence of DNA damage is expected to be low, the GV-MII transition may not demand that the DNA repair transcripts are degraded with the effect that these are maintained whereas in older mice maintaining levels of DNA repair transcripts or even an increase of some DNA repair genes may be highly warranted to enable normal fertilisation and early embryo development. From our results, there appears to be a mechanism in oocytes from old females which increases the transcript abundance of genes in various DNA repair pathways to control and repair damage to DNA and improve MII quality despite past evidence that the GV-MII transition is transcriptionally quiescent [13]. As with our study, [20] showed an increased level of transcripts in older oocytes compared to younger ones suggesting that transcript degradation was altered in old mice, possibly due to perturbed biological processes and other studies have found a decreased number of transcripts in oocytes with increased maternal age [2, 5, 6, 19–21, 44, 45]. With DNA repair genes, this decrease may result in diminished efficiency of DNA repair and/or negative effects on embryo development [44, 46]. Indeed, the loss of DNA repair capacity associated with diminished oocyte number and quality during reproductive ageing has been reviewed recently [10, 47], and there is strong evidence for a critical role of oocyte DNA repair capacity with ageing. In support of this hypothesis, [5] using GV oocyte, [21] using MII oocytes and [45] using GV and MII oocytes have all shown that increasing maternal age is associated with decreased transcripts levels of key genes involved in the DNA repair of DSB and DDR in mouse oocytes. Similarly, a decrease in the transcript abundance of DNA repair genes involved in DSB and DDR such as Brca1, Mre11, Rad51 and Atm has been described in mouse primordial follicles with age [5, 22, 23] and in buffalo primordial oocytes [6, 48]. These studies suggest that by the time oocytes have reached the GV stage, the effect of ageing has already altered the number of mRNA transcripts stored before oocyte maturation. Considering the assumption that GV oocytes from older females already present a decrease in the number of stored mRNA transcripts, the observed increase in transcript levels of DNA repair genes in MII compared to GV may be also a physiological response to compensate for the effects of ageing which could be affected by conditions such in vitro maturation and ovarian stimulation for higher oocyte yield. However, given the current dogma that the GV-MII transition is transcriptionally quiescence, further studies are now required to determine if de novo transcription is occurring at this stage.

In our study, overall IVM rates ranged between 60 and 73%, which closely resembles rates (55–65%) reported in the literature [49–51]. However, we found IVM rates that were similar between young and old mice. These findings are contrary to previous observations which showed better oocyte recovery and maturation rates in young subjects [52]. However, IVM oocytes showed lower rates of fertilisation, implantation, embryo development and poorer clinical IVF outcomes compared to oocytes spontaneously ovulated from unstimulated and stimulated females [29, 37]. Therefore, the molecular changes underlying poor oocyte quality requires further study, including an examination of oocyte DNA repair capacity as a critical element in oocyte and early embryo development [10]. Furthermore, when considering the observed effect of female age in our study and the changes in transcript abundance during the GV-MII transition, the lack of control for age in previous studies may have affected interpretation of the results. Additionally, we have found that many GVs collected from mouse ovaries lack the presence of cumulus cells; one-third of GVs were collected as ‘nude’ oocytes, one-third with partial cumulus and one-third full cumulus cells. Although all GV cohorts have some developmental capacity, nude GV oocytes have lower maturation rates (64% vs. 93%), but similar fertilisation rates (76% and 83%) to those with cumulus [53]. However, of those fertilised, the blastocyst rates is lower than those derived from GVs with full cumulus layers attached (29% vs. 80%) [53]. Thus, as different developmental capacity is observed, it is possible that transcripts difference could influence oocyte developmental competence; this research direction would be interesting to considered in future IVM studies examining transcript abundance and protein expression.

In our study, we observed that the type of stimulation also had an impact on how the relative DNA repair gene transcript abundance is modulated in young and old females during the GV-MII transition. This was particularly evident by more DNA repair genes showing significantly increased relative transcripts abundance levels when high yields of oocytes were produced using AIS in both young and old females. Indeed, our assessment of DDR using γH2AX showed an increase in the transcript levels for the gene responsible of γH2AX (H2AX) in both GV and MII oocytes from young AIS-stimulated females, leading to the hypothesis that using this stimulation to produce high yields of oocytes could induce DNA damage in oocytes leading to an increased relative levels of transcript abundance of DNA repair genes. This highlights the importance of moderating ovarian stimulation protocols, based on physiological considerations, to optimise yields of high quality oocytes in animals and humans [38]. Importantly, DSBs can accumulate in oocytes throughout life as a consequence of exogenous stressors [8], environmental toxicants [7, 54, 55], endogenous oxidative stress and maternal ageing [5]. Therefore, it is possible that the increased transcripts levels we observed in DNA repair genes could be a consequence of a higher incidence of DNA insults in oocytes as part of the ageing process. However, whether this involves de novo transcription should be explored further.

Our study was designed to consider the DNA damage response in these oocyte stages independently to assess whether the basal levels of DDR could be affected by age and type of stimulation in GV and MII oocytes. Using γH2AX as a marker of DDR activity in oocytes, we found a decreased DDR activity in both GV and MII oocytes during ageing regardless of the type of stimulation, but with increased DDR activity in young females stimulated with AIS. Previous studies have used γH2AX to measure the response of mouse GV oocytes to DSBs after exogenous DSB induction [25–27, 56]. However, it is important to recognise that for assessing actual changes in DNA damage, tests such comet assay would be required to identify genotoxicity accurately. Furthermore, we cannot disregard that many studies have interpreted increased expression of γH2AX as increased DNA damage [25, 28, 57, 58]. Considering our results, this implies that γH2AX-labelling could also be interpreted in young GV and MII oocytes as having higher basal levels of DNA damage than their aged counterparts. Hence, further studies exploring the DDR pathway in oocytes are now required to validate our findings, with particular focus in master regulators such ATM.

Indeed, GV oocytes are considered unable to trigger abundant DDR mechanisms such ATM, and are, therefore, unlikely to be capable of efficient DNA repair or go through apoptosis in aged animals [28, 57]. Considering this, our findings could be explained by a lack of ATM activation in GV oocytes [28, 57] that could potentially decrease with age in both GV and MII oocytes. Recently, it has been reported that ATM is active in MII oocytes of young females demonstrating that they can respond to DSB insults and effectively conduct DNA repair through the NHEJ pathway [58]. The findings in our ageing model suggest that oocytes from old females do not respond in the same way to DNA damage as oocytes of young females. DNA repair is critical at this stage of development to ensure DNA insults are not passed into the zygote stage. A diminished DDR activity may be also explained by decrease in expression of the key DDR gene Atm in GV and MII oocytes from aged females as previously reported [5, 23, 45]. This may result in a decrease in protein expression of ATM in GV and MII oocytes from old females and explain the decreased DDR activity by the ATM-dependent phosphorylation of the histone H2AX at serine 139 to produce γH2AX during DDR [59]. This DDR activity promotes the DNA repair of DSBs through HR and NHEJ pathways with the γH2AX foci acting as a foundation for the assembly of repair [60–62]. In support of this, a recent systematic review has shown that ATM-mediated DNA DSB repair decreases with age in oocytes of various species, including human, as a mechanism of ovarian ageing [63]. This provides additional support for the hypothesis that a decreased ATM activity during ageing leads to a decrease in DDR as observed by measuring γH2AX. However, other proteins involved in DNA damage response such 53BP1 also need to be explored. 53BP1 is a critical mediator of the DNA damage response requiring phosphorylation through ATM for the recruitment of DNA repair factors [64] and results from further studies may be used to validate our current findings. Additionally, γH2AX also participates in non-canonical functions that do not involve the DNA damage response such as the creation of specific chromatin structure involved in sex chromosome inactivation [61]; thus, additional assessments for mediators of the DNA damage response is required. Other explanations are also possible for the decrease in activity of ATM. For example, PARP-1 is also required for optimal ATM activation to enhance DRR activity [65]. Moreover, in oocytes, intracellular levels of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+) have been found to decrease with age and inhibit the critical activity of PARP-1 for several cellular functions such DNA repair and oxidative phosphorylation [66]. Recently, decreased intracellular levels of NADH (reduced form of NAD) have also been found in oocytes from old mice [67, 68]; these have the potential to affect PARP-1 activity, and thus ATM activity, causing a reduced DNA damage response.

Conclusion

Our findings show that, irrespective of how oocytes are matured, female age influences the relative DNA repair gene transcript abundance of GV and MII oocytes. This can be also triggered by ovarian stimulation to produce higher oocyte yields. Age has an impact on the way DNA repair gene transcript abundance is controlled during the GV-MII transition with more pronounced DNA repair activity in oocytes from old female mice. Although the previous dogma has considered that the transition from GV to MII stage is transcriptionally quiescence, our study, and some from other laboratories, show that age, type of stimulation, and in vitro maturation all have an impact on the relative levels of transcript abundance of DNA repair gene. The increased relative transcript abundance levels observed in MII oocytes from old females needs further study to identify whether it is required to overcome the physiological effects of potential DNA damage to the oocytes in older females. Furthermore, whether the observed increase in transcripts levels involves de novo transcription requires further research as well as the identification of actual DNA damage using methods such as comet assay.

The decrease in DDR activity we observed in oocytes from older females is an important reason now to explore the underlying causes of this reduced response in both GV and MII oocytes and whether this also occurs in the presence of known DNA damage inducers.

Electronic supplementary material

(DOCX 29 kb).

(PDF 722 kb).

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Zheng P, Schramm RD, Latham KE. Developmental regulation and in vitro culture effects on expression of DNA repair and cell cycle checkpoint control genes in rhesus monkey oocytes and embryos. Biol Reprod. 2005;72(6):1359–1369. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.104.039073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Russo G, Tosti E, El Mouatassim S, Benkhalifa M. Expression profile of genes coding for DNA repair in human oocytes using pangenomic microarrays, with a special focus on ROS linked decays. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2007;24(11):513–520. doi: 10.1007/s10815-007-9167-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ménézo Y, Dale B, Cohen M. DNA damage and repair in human oocytes and embryos: a review. Zygote. 2010;18(4):357–365. doi: 10.1017/S0967199410000286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mehlmann LM. Stops and starts in mammalian oocytes: recent advances in understanding the regulation of meiotic arrest and oocyte maturation. Reproduction. 2005;130(6):791–799. doi: 10.1530/rep.1.00793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Titus S, Li F, Stobezki R, Akula K, Unsal E, Jeong K, et al. Impairment of BRCA1-related DNA double-strand break repair leads to ovarian aging in mice and humans. Sci Transl Med. 2013;5(172):172ra21. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3004925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Govindaraj V, Basavaraju RK, Rao AJ. Changes in the expression of DNA double strand break repair genes in primordial follicles from immature and aged rats. Reprod BioMed Online. 2015;30(3):303–310. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2014.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tatone C, Amicarelli F, Carbone MC, Monteleone P, Caserta D, Marci R, Artini PG, Piomboni P, Focarelli R. Cellular and molecular aspects of ovarian follicle ageing. Hum Reprod Update. 2008;14(2):131–142. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmm048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kerr JB, Brogan L, Myers M, Hutt KJ, Mladenovska T, Ricardo S, Hamza K, Scott CL, Strasser A, Findlay JK. The primordial follicle reserve is not renewed after chemical or γ-irradiation mediated depletion. Reproduction. 2012;143:469–476. doi: 10.1530/REP-11-0430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carroll J, Marangos P. The DNA damage response in mammalian oocytes. Front Genet. 2013;4:117. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2013.00117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Winship AL, Stringer JM, Liew SH, Hutt KJ. The importance of DNA repair for maintaining oocyte quality in response to anti-cancer treatments, environmental toxins and maternal ageing. Hum Reprod Update. 2018;24(2):119–134. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmy002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Martin JH, Aitken RJ, Bromfield EG, Nixon B. DNA damage and repair in the female germline: contributions to ART. Hum Reprod Update. 2019;25(2):180–201. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmy040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stringer JM, Winship A, Zerafa N, Wakefield M, Hutt K. Oocytes can efficiently repair DNA double-strand breaks to restore genetic integrity and protect offspring health. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2020;117(21):11513–11522. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2001124117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.De La Fuente R. Chromatin modifications in the germinal vesicle (GV) of mammalian oocytes. Dev Biol. 2006;292(1):1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kocabas AM, Crosby J, Ross PJ, Otu HH, Beyhan Z, Can H, Tam WL, Rosa GJM, Halgren RG, Lim B, Fernandez E, Cibelli JB. The transcriptome of human oocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2006;103(38):14027–14032. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603227103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jaroudi S, Kakourou G, Cawood S, Doshi A, Ranieri DM, Serhal P, Harper JC, SenGupta SB. Expression profiling of DNA repair genes in human oocytes and blastocysts using microarrays. Hum Reprod. 2009;24(10):2649–2655. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dep224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zeng F, Baldwin DA, Schultz RM. Transcript profiling during preimplantation mouse development. Dev Biol. 2004;272(2):483–496. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mjelle R, Hegre SA, Aas PA, Slupphaug G, Drabløs F, Sætrom P, Krokan HE. Cell cycle regulation of human DNA repair and chromatin remodeling genes. DNA Repair. 2015;30:53–67. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2015.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gasca S, Pellestor F, Assou S, Loup V, Anahory T, Dechaud H, de Vos J, Hamamah S. Identifying new human oocyte marker genes: a microarray approach. Reprod BioMed Online. 2007;14(2):175–183. doi: 10.1016/s1472-6483(10)60785-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Su Y-Q, Sugiura K, Woo Y, Wigglesworth K, Kamdar S, Affourtit J, Eppig JJ. Selective degradation of transcripts during meiotic maturation of mouse oocytes. Dev Biol. 2007;302(1):104–117. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pan H, Ma P, Zhu W, Schultz RM. Age-associated increase in aneuploidy and changes in gene expression in mouse eggs. Dev Biol. 2008;316(2):397–407. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.01.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oktay K, Turan V, Titus S, Stobezki R, Liu L. BRCA mutations, DNA repair deficiency, and ovarian aging. Biol Reprod. 2015;93(3):67. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.115.132290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rzepka-Górska I, Tarnowski B, Chudecka-Głaz A, Górski B, Zielińska D, Tołoczko-Grabarek A. Premature menopause in patients with BRCA1 gene mutation. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2006;100(1):59–63. doi: 10.1007/s10549-006-9220-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Oktay K, Kim JY, Barad D, Babayev SN. Association of BRCA1 mutations with occult primary ovarian insufficiency: a possible explanation for the link between infertility and breast/ovarian cancer risks. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(2):240–244. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.24.2057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Paynton BV, Rempel R, Bachvarova R. Changes in state of adenylation and time course of degradation of maternal mRNAs during oocyte maturation and early embryonic development in the mouse. Dev Biol. 1988;129(2):304–314. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(88)90377-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marangos P, Carroll J. Oocytes progress beyond prophase in the presence of DNA damage. Curr Biol. 2012;22(11):989–994. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2012.03.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yuen WS, Merriman JA, O'Bryan MK, Jones KT. DNA double strand breaks but not interstrand crosslinks prevent progress through meiosis in fully grown mouse oocytes. PLoS One. 2012;7(8):e43875. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0043875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ma J-Y, Ou-Yang Y-C, Wang Z-W, Wang Z, Jiang Z-Z, Luo S-M, Hou Y, Liu Z, Schatten H, Sun QY. The effects of DNA double-strand breaks on mouse oocyte meiotic maturation. Cell Cycle. 2013;12(8):1233–1241. doi: 10.4161/cc.24311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marangos P, Stevense M, Niaka K, Lagoudaki M, Nabti I, Jessberger R, Carroll J. DNA damage-induced metaphase I arrest is mediated by the spindle assembly checkpoint and maternal age. Nat Commun. 2015;6:8706. doi: 10.1038/ncomms9706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fauser BC, Devroey P. Reproductive biology and IVF: ovarian stimulation and luteal phase consequences. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2003;14(5):236–242. doi: 10.1016/s1043-2760(03)00075-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Collins JK, Jones KT. DNA damage responses in mammalian oocytes. Reproduction. 2016;152(1):R15–R22. doi: 10.1530/REP-16-0069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Friedberg EC, Walker GC, Siede W, Wood RD, editors. DNA repair and mutagenesis. American Society for Microbiology Press; 2005.

- 32.Hasegawa A, Mochida K, Inoue H, Noda Y, Endo T, Watanabe G, Ogura A. High-yield superovulation in adult mice by anti-inhibin serum treatment combined with estrous cycle synchronization. Biol Reprod. 2016;94(1):21. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.115.134023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hernandez-Gonzalez I, Gonzalez-Robayna I, Shimada M, Wayne CM, Ochsner SA, White L, Richards JAS. Gene expression profiles of cumulus cell oocyte complexes during ovulation reveal cumulus cells express neuronal and immune-related genes: does this expand their role in the ovulation process? Mol Endocrinol. 2006;20(6):1300–1321. doi: 10.1210/me.2005-0420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schmittgen TD, Livak KJ. Analyzing real-time PCR data by the comparative C T method. Nat Protoc. 2008;3(6):1101–1108. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Metsalu T, Vilo J. ClustVis: a web tool for visualizing clustering of multivariate data using principal component analysis and heatmap. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43(W1):W566–WW70. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fauser B, Devroey P, Yen SS, Gosden R, Crowley W, Jr, Baird DT, et al. Minimal ovarian stimulation for IVF: appraisal of potential benefits and drawbacks. Hum Reprod. 1999;14(11):2681–2686. doi: 10.1093/humrep/14.11.2681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sirard M-A, Richard F, Blondin P, Robert C. Contribution of the oocyte to embryo quality. Theriogenology. 2006;65(1):126–136. doi: 10.1016/j.theriogenology.2005.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ertzeid G, Storeng R. The impact of ovarian stimulation on implantation and fetal development in mice. Hum Reprod. 2001;16(2):221–225. doi: 10.1093/humrep/16.2.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hoogenkamp H, Lewing P. Superovulation in mice in relation to their age. Vet Q. 1982;4(1):47–48. doi: 10.1080/01652176.1982.9693838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Merriman JA, Jennings PC, McLaughlin EA, Jones KT. Effect of aging on superovulation efficiency, aneuploidy rates, and sister chromatid cohesion in mice aged up to 15 months. Biol Reprod. 2012;86(2):49. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.111.095711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.van Rooij IA, Bancsi LF, Broekmans FJ, Looman CW, Habbema JDF, te Velde ER. Women older than 40 years of age and those with elevated follicle-stimulating hormone levels differ in poor response rate and embryo quality in in vitro fertilization. Fertil Steril. 2003;79(3):482–488. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(02)04839-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang H, Herath C, Xia G, Watanabe G, Taya K. Superovulation, fertilization and in vitro embryo development in mice after administration of an inhibin-neutralizing antiserum. Reproduction. 2001;122(5):809–816. doi: 10.1530/rep.0.1220809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Assou S, Anahory T, Pantesco V, Le Carrour T, Pellestor F, Klein B, et al. The human cumulus–oocyte complex gene-expression profile. Hum Reprod. 2006;21(7):1705–1719. doi: 10.1093/humrep/del065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hamatani T, Carter MG, Sharov AA, Ko MS. Dynamics of global gene expression changes during mouse preimplantation development. Dev Cell. 2004;6(1):117–131. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(03)00373-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Horta F, Catt S, Ramachandran P, Vollenhoven B, Temple-Smith P. Female ageing affects the DNA repair capacity of oocytes in IVF using a controlled model of sperm DNA damage in mice. Hum Reprod. 2020;35:529–544. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dez308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.González-Marín C, Gosálvez J, Roy R. Types, causes, detection and repair of DNA fragmentation in animal and human sperm cells. Int J Mol Sci. 2012;13(11):14026–14052. doi: 10.3390/ijms131114026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stringer JM, Winship A, Liew SH, Hutt K. The capacity of oocytes for DNA repair. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2018;75(15):2777–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 48.Govindaraj V, Krishnagiri H, Chauhan MS, Rao A. BRCA-1 gene expression and comparative proteomic profile of primordial follicles from young and adult buffalo (bubalus bubalis) ovaries. Anim Biotechnol. 2017;28(2):94–103. doi: 10.1080/10495398.2016.1210613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yoon H-G, Yoon S-H, Son W-Y, Lee S-W, Park S-P, Im K-S, Lim JH. Clinical assisted reproduction: pregnancies resulting from in vitro matured oocytes collected from women with regular menstrual cycle. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2001;18(6):325–329. doi: 10.1023/A:1016632621452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cha KY, Chung HM, Lee DR, Kwon H, Chung MK, Park LS, et al. Obstetric outcome of patients with polycystic ovary syndrome treated by in vitro maturation and in vitro fertilization–embryo transfer. Fertil Steril. 2005;83(5):1461–1465. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2004.11.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fadini R, Dal Canto M, Renzini MM, Brambillasca F, Comi R, Fumagalli D, Lain M, Merola M, Milani R, de Ponti E. Effect of different gonadotrophin priming on IVM of oocytes from women with normal ovaries: a prospective randomized study. Reprod BioMed Online. 2009;19(3):343–351. doi: 10.1016/s1472-6483(10)60168-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wiser A, Son W-Y, Shalom-Paz E, Reinblatt SL, Tulandi T, Holzer H. How old is too old for in vitro maturation (IVM) treatment? Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2011;159(2):381–383. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2011.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang X, Catt S, Pangestu M, Temple-Smith P. Successful in vitro culture of pre-antral follicles derived from vitrified murine ovarian tissue: oocyte maturation, fertilization, and live births. Reproduction. 2011;141(2):183–191. doi: 10.1530/REP-10-0383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kerr JB, Hutt KJ, Michalak EM, Cook M, Vandenberg CJ, Liew SH, Bouillet P, Mills A, Scott CL, Findlay JK, Strasser A. DNA damage-induced primordial follicle oocyte apoptosis and loss of fertility require TAp63-mediated induction of Puma and Noxa. Mol Cell. 2012;48(3):343–352. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kerr JB, Hutt KJ, Cook M, Speed TP, Strasser A, Findlay JK, Scott CL. Cisplatin-induced primordial follicle oocyte killing and loss of fertility are not prevented by imatinib. Nat Med. 2012;18(8):1170–1172. doi: 10.1038/nm.2889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lin F, Ma X-S, Wang Z-B, Wang Z-W, Luo Y-B, Huang L, Jiang ZZ, Hu MW, Schatten H, Sun QY. Different fates of oocytes with DNA double-strand breaks in vitro and in vivo. Cell Cycle. 2014;13(17):2674–2680. doi: 10.4161/15384101.2015.945375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Collins JK, Lane SI, Merriman JA, Jones KT. DNA damage induces a meiotic arrest in mouse oocytes mediated by the spindle assembly checkpoint. Nat Commun. 2015;6:8553. doi: 10.1038/ncomms9553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Martin JH, Bromfield EG, Aitken RJ, Lord T, Nixon B. Double strand break DNA repair occurs via non-homologous end-joining in mouse MII oocytes. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):9685. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-27892-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Burma S, Chen BP, Murphy M, Kurimasa A, Chen DJ. ATM phosphorylates histone H2AX in response to DNA double-strand breaks. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(45):42462–42467. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C100466200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Stracker TH, Petrini JH. The MRE11 complex: starting from the ends. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2011;12(2):90–103. doi: 10.1038/nrm3047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Turinetto V, Giachino C. Multiple facets of histone variant H2AX: a DNA double-strand-break marker with several biological functions. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43(5):2489–2498. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Pinto DMS, Flaus A. Structure and function of histone H2AX. In: Genome stability and human diseases. Dordrecht: Springer; 2010. p. 55–78. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 63.Turan V, Oktay K. BRCA-related ATM-mediated DNA double-strand break repair and ovarian aging. Hum Reprod Update. 2020;26(1):43–57. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmz043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wang B, Matsuoka S, Carpenter PB, Elledge SJ. 53BP1, a mediator of the DNA damage checkpoint. Science. 2002;298(5597):1435–1438. doi: 10.1126/science.1076182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Huber A, Bai P, De Murcia JM, De Murcia G. PARP-1, PARP-2 and ATM in the DNA damage response: functional synergy in mouse development. DNA Repair. 2004;3(8-9):1103–1108. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2004.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Li J, Bonkowski MS, Moniot S, Zhang D, Hubbard BP, Ling AJ, et al. A conserved NAD+ binding pocket that regulates protein-protein interactions during aging. Science. 2017;355(6331):1312–1317. doi: 10.1126/science.aad8242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sanchez T, Wang T, Pedro MV, Zhang M, Esencan E, Sakkas D, Needleman D, Seli E. Metabolic imaging with the use of fluorescence lifetime imaging microscopy (FLIM) accurately detects mitochondrial dysfunction in mouse oocytes. Fertil Steril. 2018;110(7):1387–1397. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2018.07.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bertoldo MJ, Listijono DR, Ho W-HJ, Riepsamen AH, Goss DM, Richani D, et al. NAD+ repletion rescues female fertility during reproductive aging. Cell Rep. 2020;30(6):1670–81.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2020.01.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX 29 kb).

(PDF 722 kb).