Abstract

Gastric cancer is common, especially in East Asian countries, and is associated with high recurrence and mortality rates. Currently, there is no standard third-line treatment for metastatic gastric cancer. In this report, we present the case of a 69-year-old man with advanced gastric cancer, whose tumor was negative for human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) according to immunohistochemical analysis. Next-generation sequencing performed on paraffin sections of the postoperative tumor samples indicated the presence of the ERBB3 V104L mutation. The patient received irinotecan plus pyrotinib as a third-line therapy and achieved a progression-free survival of 7.6 months with a high quality of life. Therefore, the combined administration of irinotecan and pyrotinib may improve the clinical condition of patients with gastric cancer harboring an ERBB3 mutation. Moreover, ERBB3 could be a potential therapeutic target for gastric cancer.

Keywords: ERBB3, gastric cancer, irinotecan, pyrotinib, third-line therapy

Introduction

Gastric cancer is the second leading cause of cancer-related deaths in Asia.1 After systematic first- and second-line treatments, approximately 20–90% of patients receive active third-line or subsequent treatments;2–5 however, there are no standard advanced therapy protocols for metastatic gastric cancer, according to the National Comprehensive Cancer Network Guidelines. Preferred therapies include ramucirumab plus paclitaxel, taxane, irinotecan, TAS-102, fluorouracil plus irinotecan, apatinib, or pembrolizumab. A systematic review and meta-analysis of advanced gastric cancer indicated that the median overall survival of patients receiving third-line therapy is approximately 4.80 months compared with the 3.20 months for patients receiving only the best supportive care.6 Thus, the lack of effective third-line therapies for gastric cancer significantly restricts patient survival.

Herein, we present the case of a patient with advanced gastric cancer harboring the ERBB3 V104L mutation, who received pyrotinib plus irinotecan as a third-line therapy and achieved a progression-free survival (PFS) of 7.6 months with a high quality of life (QOL).

Case Presentation

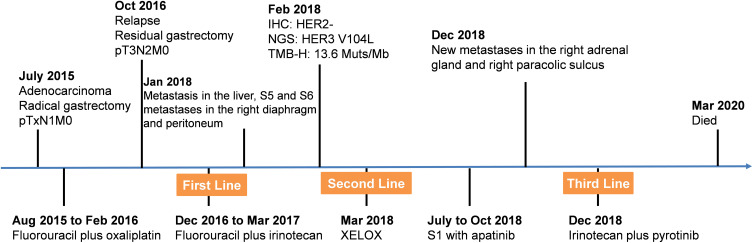

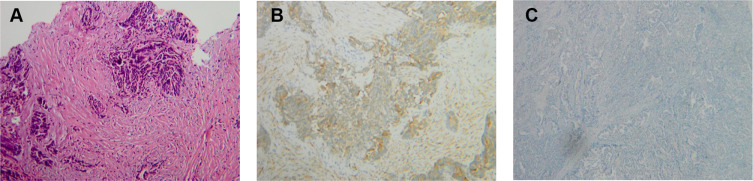

A 69-year-old man was diagnosed with gastric adenocarcinoma in July 2015 via endoscopic biopsy. He had a family history of cancer, as his sister had colon cancer. The timeline of his treatments is shown in Figure 1. First, he underwent radical gastrectomy with postoperative pTxN1M0 grade (in another hospital). Later, from August 2015 to February 2016, the patient underwent six cycles of treatment with fluorouracil plus oxaliplatin as adjuvant chemotherapy. In October 2016, via gastroscopy, the patient was confirmed to have relapsed. Therefore, a residual gastrectomy was performed, and the postoperative stage was pT3N2M0. After the surgery, the patient received four cycles of treatment with fluorouracil plus irinotecan from December 2016 to March 2017. However, he stopped chemotherapy due to the onset of adverse events, including thrombocytopenia and diarrhea. In January 2018, he underwent positron emission tomography-computed tomography (PET-CT) due to abdominal distension. The scans showed multiple metastases in the right diaphragm and peritoneum, with a large amount of fluid in the abdominal cavity and metastasis to the liver (S5 and S6), indicating extensive disease progression. The staining results of the abdominal wall nodules are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 1.

The timeline of the treatment.

Abbreviations: IHC, immunohistochemistry; NGS, next-generation sequencing.

Figure 2.

Histologic results of abdominal wall nodules. (A) Hematoxylin-eosin staining (magnification: ×200). (B) Cytokeratin immunohistochemistry (magnification: ×200). (C) Human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) immunohistochemistry (magnification: ×200).

In February 2018, immunohistochemical (IHC) analysis showed that the tumor was negative for human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) (Figure 2C). The tumor tissues and matched blood samples were sent to the College of American Pathologists (CAP)-accredited and Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA)-certified laboratory (OrigiMed, Shanghai, China) for targeted next-generation sequencing (NGS). Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient to have the case details and any accompanying images for publication. The genomic results revealed a mutation in ERBB3 (V104L), accompanied by mutations in TP53 (R273C), KRAS (G12F), and AMER1 (Q577*), as well as amplification of CCNE1/FOS/GATA6/MCL1/MYCN/CIC. The tumor mutational burden was 13.6 muts/Mb. Programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) expression was negative and no germline mutations were detected. In March 2018, he received two courses of peritoneal thermal perfusion therapy, followed by two courses of paclitaxel peritoneal administration (240 mg). The patient was then administered six cycles of capecitabine (1 g po bid d1–14 q3w) plus oxaliplatin (230 mg ivd qd d1 q3w). In July, the CT scan suggested that the disease was stable but without significant improvement. He continued maintenance treatment with four cycles of S-1 (60 mg po bid d1–14 q3w) plus apatinib (0.25 g po qd) until October 2018. However, due to intolerable adverse events, such as incomplete small bowel obstruction, the maintenance treatment was changed to apatinib (0.5 g po qd).

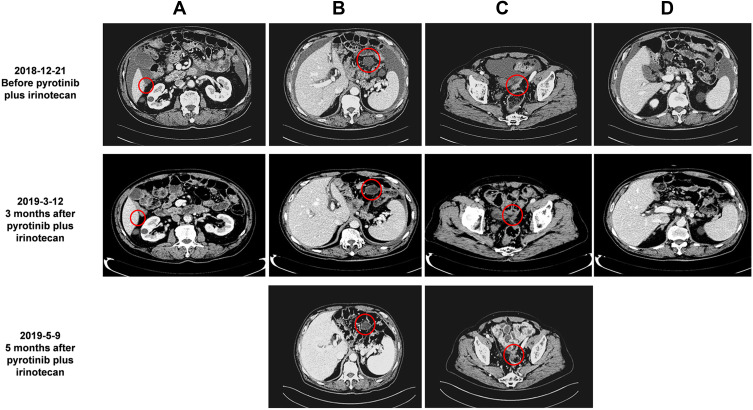

In December 2018, the disease progressed with new metastases in the right adrenal gland and right paracolic sulcus revealed by CT examination. Considering that his previous NGS test indicated the presence of an ERBB3 mutation, we administered irinotecan (330 mg ivd qd d1 q2w) plus pyrotinib (320 mg qd) starting on December 28, 2018. CT scans performed on March 12 and May 9, 2019, showed stable disease (Figure 3) with decreased effusion of the abdominal cavity. The patient experienced an improvement in abdominal distension, and no additional adverse events were observed. However, on August 6, CT scans showed an increase in the abdominal metastatic tumor as well as the abdominal and pelvic effusion, which suggested disease progression. Therefore, the PFS was 7.6 months.

Figure 3.

The patient’s condition clinically improved after treatment with pyrotinib and irinotecan. (A) Liver S6 metastasis disappeared after treatment; (B) The diameter of the metastatic peritoneal cyst was reduced from 3.7 to 3.2 cm after treatment and maintained; (C) The diameter of the metastatic peritoneal reflex was reduced from 3.3 to 2.5 cm after treatment and maintained; (D) Ascites were significantly reduced after treatment. Red circles indicate metastatic tumor lesions.

Thereafter, the patient underwent chemotherapy, targeted therapy, and immunotherapy; however, he did not exhibit a good response. CT scans revealed multiple metastases in the abdomen and liver (S6). The patient died in March 2020.

Discussion

The benefits of the existing third-line treatments for advanced gastric cancer are limited, and many patients cannot tolerate chemotherapy-related toxicity. In recent years, targeted therapy has provided a new treatment strategy for advanced gastric cancer with more convenience and fewer side effects. However, at present, only the treatment of HER2-positive advanced gastric cancer has been effective.7 Therefore, effective therapies targeting cancer driver genes are still warranted. Herein, we report a patient with HER2-negative gastric cancer harboring an ERBB3 mutation. He received pyrotinib plus irinotecan as a third-line treatment, which resulted in a PFS of 7.6 months and a high QOL. We believe that this case provides important medical evidence for the beneficial clinical application of pan-ErbB inhibitors.

ERBB3, encoded by the ERBB3 gene, is a member of the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) family. Although its intracellular tyrosine kinase domain is weak, it can still form active heterodimers with other EGFR members, thus activating pathways involved in cell proliferation and differentiation.8–10 ERBB3 mutations have been identified in some cancers, including colon and gastric cancers,11–19 which have ligand-independent and HER2-dependent transformation abilities.20 The ERBB3 V104L mutation is one of the main hotspot mutations in the extracellular domain and was identified in gallbladder cancer, rectal neuroendocrine tumors, and lung sarcomatoid carcinoma.19,21–23

Some anti-ERBB3 drugs, such as patritumab, AZD8931, and U3-1402, are still under preclinical and clinical development.24–26 Considering that ERBB3 needs to form a heterodimer with other EGFR members, antitumor drugs that target the EGFR/HER2 may be effective. Some clinical benefits have been observed with afatinib, trastuzumab plus lapatinib, and lapatinib alone, among other treatment regimens.22,27 For instance, a patient with a rectal neuroendocrine tumor harboring the ERBB3 V104L mutation was treated with trastuzumab and lapatinib as a third-line therapy, resulting in a stable disease and a PFS of 51 days.22 However, HER2-negative breast cancer patients with the ERBB3 G284R mutation, who received trastuzumab with lapatinib as a third-line treatment, showed only a partial response (PR) for more than 40 weeks.27 Additionally, a biliary tract carcinoma patient harboring an ERBB3 mutation achieved a PR after receiving trastuzumab plus lapatinib.33 Additionally, two metastatic urothelial cancers with ERBB3 V104M and G284R mutations achieved 6.3 months and 7 months of PFS, respectively, after treatment with the inhibitor afatinib (Table 1).32

Table 1.

Reported Cases Harboring ERBB3 Mutations Treated with Targeted Therapy

| Tumor Type | ERBB3 Mutation | Treatment | Treatment Line | Response | PFS | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rectal neuroendocrine tumor | V104L | Trastuzumab with Lapatinib | Third-line | SD | 51 days | [22] |

| Breast cancer | G284R | Trastuzumab with Lapatinib | Third-line | PR | 40 weeks | [27] |

| Biliary tract carcinoma | – | Trastuzumab with Lapatinib | – | PR | – | [32] |

| Metastatic urothelial cancer | V104M | Afatinib | – | SD | 6.3 months | [31] |

| Metastatic urothelial cancer | G284R | Afatinib | – | SD | 7 months | [31] |

Abbreviations: PR, partial response; PFS, progression-free survival; SD, stable disease.

Pyrotinib is an oral, irreversible pan-ErbB inhibitor capable of blocking EGFR/HER1, HER2, and HER4 activities.28 A Phase II study showed that pyrotinib was effective in treating HER2-positive breast cancer, with a superior response to lapatinib.29 In addition, preclinical studies have confirmed that pyrotinib successfully treated non-small-cell lung carcinoma with an HER2 exon 20 mutation and HER2-positive gastric cancer.30,31,33 However, its effects on HER2-negative gastric cancer remains unknown. Here, we showed that a patient with HER2-negative gastric cancer harboring an ERBB3 mutation who received pyrotinib plus irinotecan as a third-line treatment gained a PFS of 7.6 months with a high QOL, indicating the potential of pyrotinib in treating HER2-negative gastric cancer patients with ERBB3 mutations.

One limitation of this study is that administering pyrotinib and irinotecan at the same time made it difficult to distinguish which drug produced the therapeutic effect. However, compared with the previously used fluorouracil plus irinotecan, the patient’s clinical condition was significantly improved by the irinotecan and pyrotinib combination, and his PFS reached nearly 8 months, indicating that the use of pyrotinib may have contributed to the antitumor activity by targeting the ERBB3 (V104L) mutation in this case, since pyrotinib is a pan-ErbB inhibitor. In addition, further evaluations are warranted to confirm whether pyrotinib could be widely used in gastric cancer patients with ERBB3 alterations. Collectively, we believe that ERBB3 mutations should be considered a new target for the treatment of gastric cancer.

Funding Statement

This study was funded by The National Key Research and Development Program of China (grant number 2017YFC1700603). The funding agency had no role in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data, writing of the report, or decision to submit the article for publication.

Ethics Approval

This study was approved by the ethics committee of the Second Affiliated Hospital of Guangzhou University of Chinese Medicine. Written informed consent for this case report has been obtained from the patient.

Author Contributions

All authors made a significant contribution to the work reported, whether that is in the conception, study design, execution, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation, or in all these areas; took part in drafting, revising or critically reviewing the article; gave final approval of the version to be published; have agreed on the journal to which the article has been submitted; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

T.H. and W.W. declare personal fees from OrigMed outside the submitted work, and are employees of OrigiMed. The authors report no other potential conflicts of interest for this work.

References

- 1.Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, et al. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68(6):394–424. doi: 10.3322/caac.21492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kang JH, Lee SI, Lim DH, et al. Salvage chemotherapy for pretreated gastric cancer: a randomized Phase III trial comparing chemotherapy plus best supportive care with best supportive care alone. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(13):1513–1518. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.4585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hironaka S, Ueda S, Yasui H, et al. Randomized, open-label, phase III study comparing irinotecan with paclitaxel in patients with advanced gastric cancer without severe peritoneal metastasis after failure of prior combination chemotherapy using fluoropyrimidine plus platinum: WJOG 4007 trial. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(35):4438–4444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wilke H, Muro K, Van Cutsem E, et al. Ramucirumab plus paclitaxel versus placebo plus paclitaxel in patients with previously treated advanced gastric or gastro-oesophageal junction adenocarcinoma (RAINBOW): a double-blind, randomised Phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15(11):1224–1235. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70420-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li J, Qin S, Xu J, et al. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase III trial of apatinib in patients with chemotherapy-refractory advanced or metastatic adenocarcinoma of the stomach or gastroesophageal junction. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(13):1448–1454. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.63.5995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chan WL, Yuen KK, Siu SW, et al. Third-line systemic treatment versus best supportive care for advanced/metastatic gastric cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2017;116:68–81. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2017.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bang Y-J, Van Cutsem E, Feyereislova A, et al. Trastuzumab in combination with chemotherapy versus chemotherapy alone for treatment of HER2-positive advanced gastric or gastro-oesophageal junction cancer (ToGA): a phase 3, open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2010;376(9742):687–697. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61121-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shi F, Telesco SE, Liu Y, et al. ErbB3/HER3 intracellular domain is competent to bind ATP and catalyze autophosphorylation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(17):7692–7697. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1002753107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Collier TS, Diraviyam K, Monsey J, et al. Carboxyl group footprinting mass spectrometry and molecular dynamics identify key interactions in the HER2-HER3 receptor tyrosine kinase interface. J Biol Chem. 2013;288(35):25254–25264. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.474882 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Littlefield P, Liu L, Mysore V, et al. Structural analysis of the EGFR/HER3 heterodimer reveals the molecular basis for activating HER3 mutations. Sci Signal. 2014;7(354):ra114. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2005786 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Research Misconduct Found]

- 11.Beji A, Horst D, Engel J, et al. Toward the prognostic significance and therapeutic potential of HER3 receptor tyrosine kinase in human colon cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18(4):956–968. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-1186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rajkumar T, Stamp GW, Hughes CM, et al. c-erbB3 protein expression in ovarian cancer. Clin Mol Pathol. 1996;49(4):M199–M202. doi: 10.1136/mp.49.4.M199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yi ES, Harclerode D, Gondo M, et al. High c-erbB-3 protein expression is associated with shorter survival in advanced non-small cell lung carcinomas. Mod Pathol. 1997;10(2):142‐148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sergina NV, Rausch M, Wang D, et al. Escape from HER-family tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy by the kinase-inactive ERBB3. Nature. 2007;445(7126):437–441. doi: 10.1038/nature05474 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Garrett JT, Olivares MG, Rinehart C, et al. Transcriptional and posttranslational up-regulation of ERBB3 (ErbB3) compensates for inhibition of the HER2 tyrosine kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108(12):5021–5026. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1016140108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brand TM, Hartmann S, Bhola NE, et al. Cross-talk signaling between ERBB3 and HPV16 E6 and E7 mediates resistance to PI3K inhibitors in head and neck cancer. Cancer Res. 2018;78(9):2383–2395. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-17-1672 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Research Misconduct Found]

- 17.Hutcheson IR, Goddard L, Barrow D, et al. Fulvestrant-induced expression of ErbB3 and ErbB4 receptors sensitizes oestrogen receptor-positive breast cancer cells to heregulin β1. Breast Cancer Res. 2011;13(2):R29. doi: 10.1186/bcr2848 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chausovsky A, Tsarfaty I, Kam Z, et al. Morphogenetic effects of neuregulin (neu differentiation factor) in cultured epithelial cells. Mol Biol Cell. 1998;9(11):3195–3209. doi: 10.1091/mbc.9.11.3195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kiavue N, Cabel L, Melaabi S, et al. ERBB3 mutations in cancer: biological aspects, prevalence and therapeutics. Oncogene. 2020;39(3):487–502. doi: 10.1038/s41388-019-1001-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jaiswal BS, Kljavin NM, Stawiski EW, et al. Oncogenic ERBB3 mutations in human cancers. Cancer Cell. 2013;23(5):603–617. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2013.04.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li M, Liu F, Zhang F, et al. Genomic ERBB2/ERBB3 mutations promote PD-L1-mediated immune escape in gallbladder cancer: a whole-exome sequencing analysis. Gut. 2019;68(6):1024–1033. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2018-316039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Verlingue L, Hollebecque A, Lacroix L, et al. Human epidermal receptor family inhibitors in patients with ERBB3 mutated cancers: entering the back door. Eur J Cancer. 2018;92:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2017.12.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li X, He Y, Zhu J, et al. Apatinib-based targeted therapy against pulmonary sarcomatoid carcinoma: a case report and literature review. Oncotarget. 2018;9(72):33734–33738. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.25989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mendell J, Freeman DJ, Feng W, et al. Clinical translation and validation of a predictive biomarker for patritumab, an anti-human epidermal growth factor receptor 3 (ERBB3) monoclonal antibody, in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer. EBioMedicine. 2015;2(3):264–271. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2015.02.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thomas A, Virdee PS, Eatock M, et al. Dual Erb B Inhibition in Oesophago-gastric Cancer (DEBIOC): a phase I dose escalating safety study and randomised dose expansion of AZD8931 in combination with oxaliplatin and capecitabine chemotherapy in patients with oesophagogastric adenocarcinoma. Eur J Cancer. 2020;124:131–141. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2019.10.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hashimoto Y, Koyama K, Kamai Y, et al. A novel ERBB3-targeting antibody-drug conjugate, U3-1402, exhibits potent therapeutic efficacy through the delivery of cytotoxic payload by efficient internalization. Clin Cancer Res. 2019;25(23):7151–7161. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-19-1745 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bidard FC, Ng CK, Cottu P, et al. Response to dual HER2 blockade in a patient with ERBB3-mutant metastatic breast cancer. Ann Oncol. 2015;26(8):1704–1709. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdv217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gourd E. Pyrotinib shows activity in metastatic breast cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18(11):e643. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30755-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ma F, Ouyang Q, Li W, et al. Pyrotinib or lapatinib combined with capecitabine in HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer with prior taxanes, anthracyclines, and/or trastuzumab: a randomized, phase II study. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37(29):2610–2619. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.00108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gao Z, Song C, Li G, et al. Pyrotinib treatment on HER2-positive gastric cancer cells promotes the released exosomes to enhance endothelial cell progression, which can be counteracted by apatinib. Onco Targets Ther. 2019;12:2777–2787. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S194768 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Choudhury NJ, Campanile A, Antic T, et al. Afatinib activity in platinum-refractory metastatic urothelial carcinoma in patients with ERBB alterations. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(18):2165–2171. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.66.3047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Verlingue L, Massard C, Hollebecque A, et al. Clinical efficacy of HER3 partners’ inhibitors in ERBB3 mutated cancer patients. Ann Oncol. 2016;27(6):122P. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdw363.70 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Su B, Huang T, Jin Y, et al. Apatinib exhibits synergistic effect with pyrotinib and reverses acquired pyrotinib resistance in HER2-positive gastric cancer via stem cell factor/c-kit signaling and its downstream pathways. Gastric Cancer. 2020:1–16. doi: 10.1007/s10120-019-01020-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]