Abstract

Purpose

The prevalence of childhood obesity has increased over past decades with a concomitant increase in metabolic and bariatric surgery (MBS). While MBS in adults is associated with bone loss, only a few studies have examined the effect of MBS on the growing skeleton in adolescents.

Methods

This mini-review summarizes available data on the effects of the most commonly performed MBS (sleeve gastrectomy and gastric bypass) on bone in adolescents. A literature review was performed using PubMed for English-language articles.

Results

Dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) measures of areal bone mineral density (aBMD) and BMD Z scores decreased following all MBS. Volumetric BMD (vBMD) by quantitative computed tomography (QCT) decreased at the lumbar spine while cortical vBMD of the distal radius and tibia increased over a year following sleeve gastrectomy (total vBMD did not change). Reductions in narrow neck and intertrochanteric cross-sectional area and cortical thickness were observed over this duration, and hip strength estimates were deleteriously impacted. Marrow adipose tissue (MAT) of the lumbar spine increased while MAT of the peripheral skeleton decreased a year following sleeve gastrectomy. The amount of weight loss and reductions in lean and fat mass correlated with bone loss at all sites, and with changes in bone microarchitecture at peripheral sites.

Conclusion

MBS in adolescents is associated with aBMD reductions, and increases in MAT of the axial skeleton, while sleeve gastrectomy is associated with an increase in cortical vBMD and decrease in MAT of the peripheral skeleton. No reductions have been reported in peripheral strength estimates.

Keywords: bone density, bone strength, bone markers, weight loss surgery, sleeve gastrectomy, gastric bypass

The prevalence of childhood obesity has markedly increased over past decades. Reports indicate that 17% of children now have a body mass index (BMI) >95th percentile, and 12% have a BMI >97th percentile (1). This is of concern as most children with obesity will continue to have obesity as adults (2, 3) with increased risk of premature morbidity and mortality (4, 5). Unfortunately, treatment with lifestyle modification is difficult to sustain and recidivism is common. Further, there are few approved medical therapies for obesity in children, with significant side effects limiting their use (6). As a consequence, increasing numbers of adolescents are electing to undergo metabolic and bariatric surgery (MBS) (7) and the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery has proposed offering MBS early to patients with severe obesity, rather than waiting until comorbidities develop (8).

The 2 most common surgical options for MBS are sleeve gastrectomy and Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB), which are effective in reducing weight and treating obesity-related comorbidities (9, 10). However, the effects of sleeve gastrectomy and RYGB on the growing skeleton have only been examined in a few studies to date (11–14). Adolescence is a time of maximal bone accrual towards attainment of peak bone mass, a key determinant of bone health and future fracture risk. Processes that affect bone health in these critical years are likely to be permanent, leading to increased fracture risk later in life (15). Therefore, there is a need for long-term prospective studies examining bone outcomes in adolescents and young adults undergoing MBS.

Most studies that have examined the effects of MBS in adolescents on bone have shown a reduction of areal bone mineral density (aBMD) by dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA). However, DXA output is influenced by extreme changes in soft tissues, as can be seen after MBS, which might overestimate bone loss (16, 17). Advanced imaging methods, such as spine or hip quantitative computed tomography (QCT) (18), which measures volumetric BMD (vBMD) at these sites, peripheral QCT (pQCT), which measures vBMD and bone geometry at the distal radius and tibia, and high-resolution pQCT (HRpQCT), which measures vBMD, bone geometry, and microarchitecture at the distal radius and tibia can overcome some of these challenges with less susceptibility to extreme changes in body size. Data from such studies in children are very limited.

Mechanisms impacting bone health after MBS surgery are multifactorial and include changes in body composition, malabsorption, altered hormones, and enteric peptides (19–23). Moreover, the microenvironment of bone, specifically marrow adipose tissue (MAT), has been shown to be an important determinant of skeletal integrity, independent of BMD (24, 25). Indeed, studies have shown higher MAT in states of starvation and visceral adiposity (26–30). MAT can be quantified noninvasively using proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy (1H-MRS) without ionizing radiation exposure (26, 31), which is particularly important in children. This mini-review aims to summarize available data on the effects of MBS procedures on BMD, bone geometry, microarchitecture, and MAT, as well as bone strength estimates in adolescents and young adults with obesity. Mechanisms affecting skeletal health after MBS in children and adolescents are also discussed.

Search Strategies

We performed a literature review using PubMed for English-language articles. No beginning date limit was used, and the search was last updated in September 2020. The search terms were (“bariatric surgery” OR “sleeve gastrectomy” OR “gastric bypass”) AND “bone” AND (“adolescents” OR “children).” A total of 113 records, including 95 original articles and 28 review articles were identified. A review of the abstracts narrowed down the number of publications relevant to bone health following MBS in youth to 8 original research papers.

Results

Impact of metabolic and bariatric surgery on bone mineral density

DXA measures of areal BMD

While MBS procedures are highly effective in reducing weight and metabolic comorbidities, deleterious effects on the skeleton have been reported in adults, with reductions in aBMD (22, 32) and an increase in fracture risk (33). Only a few studies have examined the effect of MBS on BMD in adolescents (11, 13, 14): 1 in patients undergoing sleeve gastrectomy (14), 2 after RYGB (11, 13), and 1 after intragastric balloon placement (34), all showing reductions in aBMD by DXA. Beamish et al. (11) examined 72 adolescents before and 2 years after RYGB. There was a significant decrease in whole body aBMD, bone mineral content (BMC) and aBMD Z-scores over the 2 years and this reduction was more pronounced in girls than in boys. Of note, aBMD Z-scores were above the normal range at baseline and, despite a significant decrease over 2 years, mean aBMD Z-scores remained above normal (11). In a retrospective case review, Kaulfers et al. (13) examined whole body DXA scans in 61 adolescents before and 2 years after RYGB. Whole-body BMC, aBMD and aBMD Z-scores significantly decreased over 2 years after surgery. As in the study by Beamish et al (11), BMD Z-scores remained above average for at least 2 years after surgery (13). In a prospective study of 22 adolescents and young adults undergoing sleeve gastrectomy and 22 controls with obesity followed without surgery for 1 year, Misra et al. (14) examined aBMD of the lumbar spine, hip, distal radius, and whole body. BMD and BMD Z-scores of the femoral neck and total hip decreased significantly over a year after surgery compared with controls, and these differences remained significant after controlling for age, sex, and race (14). A subsequent study using hip structural analysis in the same cohort reported reductions in narrow neck and intertrochanteric (but not femoral shaft) aBMD and aBMD Z-scores in the surgical versus nonsurgical groups over a year, even after controlling for covariates (35). There were no significant differences between groups for changes in aBMD or aBMD Z-scores of the distal radius, lumbar spine, or whole body over the year (14).

QCT measures of volumetric BMD

Areal BMD determined by DXA is susceptible to artifactual changes following extreme changes in body composition, such as weight loss following MBS (16). The challenges of DXA in states of obesity and extreme weight loss can be partially overcome by QCT which measures vBMD, and is less susceptible to changes in body size (18). QCT can be performed of the axial or peripheral skeleton.

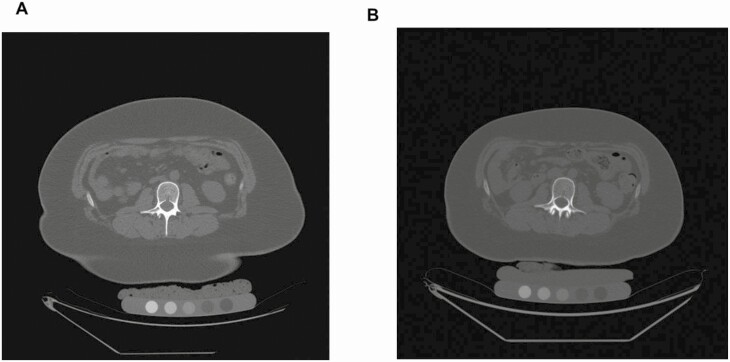

One study assessed vBMD of the lumbar spine by QCT in 26 adolescents undergoing sleeve gastrectomy and 26 controls with obesity followed without surgery for 1 year. vBMD of the lumbar spine decreased within the sleeve gastrectomy group (Fig. 1); however, the 1-year change between the groups only revealed a trend (12).

Figure 1.

BMD QCT pre–post: QCT of L2 in a 17-year-old female prior to (A) and 12 months after sleeve gastrectomy (B). Volumetric BMD (vBMD) decreased following sleeve gastrectomy (vBMD presurgery 183 mg/cm3, vBMD postsurgery 146 mg/cm3). CT images are presented using the same window and level.

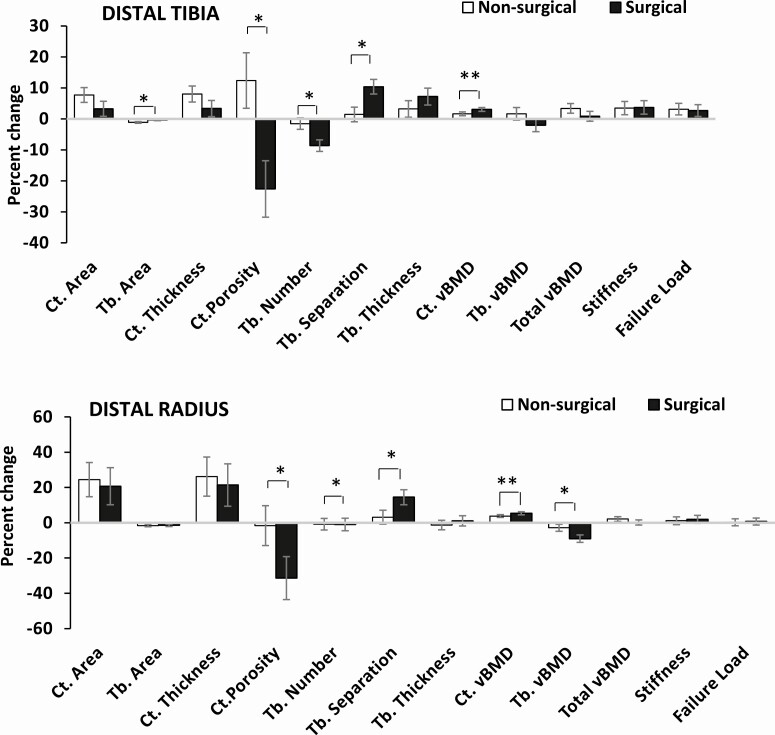

Only 1 study to date has examined changes in vBMD at peripheral sites, including the distal radius and distal tibia (using HRpQCT), in adolescents and young adults with obesity following sleeve gastrectomy compared with nonsurgical controls (14) (Fig. 2). In contrast to studies in adults undergoing gastric bypass that reported reductions in cortical and total vBMD following surgery (36-38), this study in youth reported increases in cortical vBMD in both the surgical and nonsurgical groups over a year at both the distal radius and the distal tibia (after controlling for age, sex, race, and baseline measures of BMD), with the increase being more marked in the surgical group, likely a consequence of a decrease in cortical porosity. Increases in cortical vBMD in the nonsurgical group likely reflect the physiologic increase in these measures noted during and following puberty (39, 40). Of note, adolescent girls with obesity have greater cortical porosity at peripheral sites than controls of normal weight, likely because mineralization lags in bone that is expanding in girth with the increased mechanical loading associated with obesity (41). It is possible that weight loss or other changes following bariatric surgery reduce or reverse this effect.

Figure 2.

Percent change in HRpQCT measures at the distal tibia (top) and distal radius (bottom) in the nonsurgical and sleeve gastrectomy groups (after controlling for age, sex, and race). *P < .05, **P < .10. Ct., cortical; Tb., trabecular; vBMD, volumetric bone mineral density. Reproduced with permission from Misra et al. Bone 2020.

However, despite the increase in cortical vBMD, total vBMD increased only in the nonsurgical controls (at the tibia), with no significant between group differences noted (14). This may reflect the decrease in trabecular vBMD noted following surgery, particularly at the distal radius (14). Studies in adults following gastric bypass have similarly reported preferential reductions in trabecular vBMD at the distal radius compared with the tibia (23). Interestingly, the adolescent/young adult study reported a 9% reduction in trabecular vBMD over a year, which was similar to the magnitude of trabecular vBMD reduction observed after 2 years in adults following gastric bypass (23, 36, 38). Longer term data are required in youth to determine whether trabecular vBMD continues to decrease over time or stabilizes over time. Of note, a 5-year follow-up study in adults following gastric bypass reported continued decreases in trabecular vBMD over this duration (36).

Impact of metabolic and bariatric surgery on bone geometry and microarchitecture

Distal tibia and radius

In the study of youth following sleeve gastrectomy (14), the group that had surgery did not demonstrate the expected pubertal and postpubertal increase in cortical area and thickness at the tibia over the 1-year follow-up period (39, 40). However, these measures did not decrease over time, unlike observations in adults following gastric bypass (36–38, 42). The surgical group had significant reductions in trabecular number and increases in trabecular separation of the distal tibia over a year compared with nonsurgical controls (all analyses were adjusted for age, sex, race, and the baseline bone measure), although these changes did not result in a reduction in trabecular vBMD. Similarly, for the distal radius, and unlike adults after bypass and sleeve procedures (36, 37), adolescents and young adults with obesity did not demonstrate a change in bone geometry over a year, which is reassuring, at least in the short term. Similar trends but of a lower magnitude were observed for changes in trabecular number and separation at the distal radius versus tibia. Despite the lower magnitude of change, trabecular vBMD did decrease at the distal radius compared with nonsurgical controls. In contrast to the deleterious effects in trabecular microarchitecture, sleeve gastrectomy was followed by improved cortical microarchitecture with reductions in cortical porosity over a year, likely because the cortex was not expanding as much as in controls, allowing for bone to mineralize better. Figure 2 shows changes in bone geometry and microarchitecture over a year in youth undergoing sleeve gastrectomy versus nonsurgical controls.

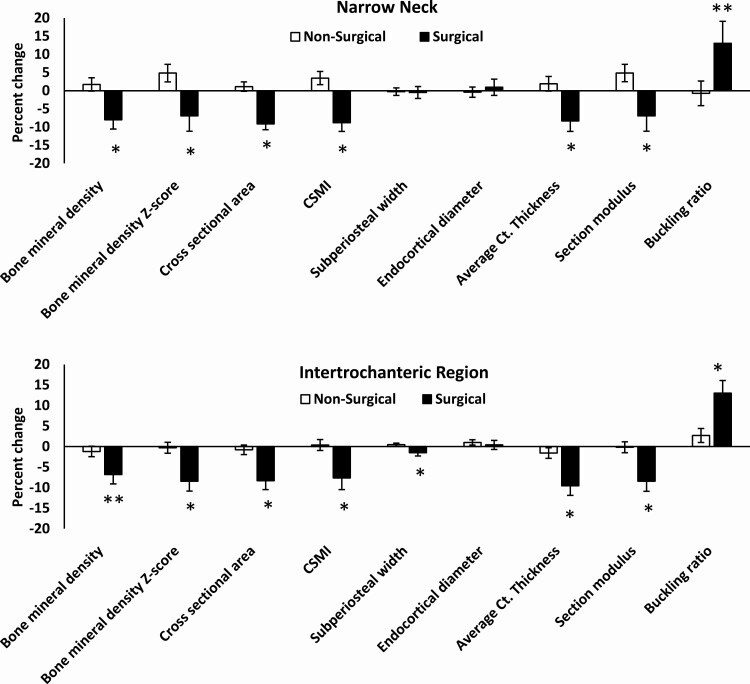

Hip structural analysis

In youth followed over a year, sleeve gastrectomy led to reductions in narrow neck and intertrochanteric cross-sectional area and cortical thickness, and an increase in hip axis length compared with nonsurgical group after adjusting for age, sex, race, and baseline bone measures (35). Figure 3 shows changes in hip structural analysis parameters over a year following sleeve gastrectomy.

Figure 3.

Percent change in hip structural analysis (HSA) measures at the narrow neck and intertrochanteric region in the surgical versus nonsurgical groups over 12 months. CSMI: cross-sectional moment of inertia; Ct, cortical; *P < .05; **P < .10 (both after controlling for age, sex, and race). Reproduced with permission from Misra et al. Surg Obes Rel Dis 2020.

Impact of metabolic and bariatric surgery on bone strength estimates

Distal radius and tibia

Adolescents and young adults with obesity undergoing sleeve gastrectomy did not demonstrate the increase in bone stiffness and failure load (as assessed by microfinite element analysis) observed in the nonsurgical controls at the weight-bearing tibia over a year, the latter being consistent with the expected pubertal/postpubertal increase in bone strength (39, 40). Reassuringly, the group undergoing surgery had no reductions in strength estimates at the distal radius and tibia over a year, in contrast to data from several studies in adults undergoing gastric bypass (36, 38, 42), some of which have reported as much as a 20% reduction in strength estimates following surgery. Of note, 1 study in adults undergoing either gastric bypass or sleeve gastrectomy also did not report reductions in strength estimates at these sites (37). It will be important to determine whether a longer duration of follow-up than a year demonstrates a reduction in strength estimates in youth following MBS.

Hip structural analysis

In contrast to these peripheral sites, strength estimates such as cross-sectional moment of inertia decreased, while buckling ratio increased over a year at the narrow neck and intertrochanteric region in adolescents and young adults who had sleeve gastrectomy compared with the nonsurgical group after adjusting for baseline covariates (35). Both changes indicate a reduction in bone strength at this site over a year and appear concerning as hip geometry parameters in childhood correlate with adult hip geometry (43), and may predict increased hip fracture risk in adult life. However, most differences between groups were attenuated after controlling for changes in BMI over the year, indicating that skeletal unloading (and potentially metabolic and hormonal changes associated with BMI reduction) accounted for these changes. In fact, the groups did not differ at 12 months for most measures (other than for narrow neck buckling ratio) after adjusting for body weight at this time. This may indicate that fracture risk is not increased in these individuals because of the associated decrease in the force of a fall given the reduced BMI. In fact, changes in bone density, geometry, structure, and strength in youth following sleeve gastrectomy may just be adaptive to the skeletal unloading that follows such surgery.

Fractures

One study reported no fractures following gastric bypass in adolescents over 2 years (11), but longer term data are currently lacking. In adults, Yu et al. (44) have reported increased fracture risk after gastric bypass surgery versus adjustable gastric banding that increased steadily between 2 and 5 years following surgery.

Impact of metabolic and bariatric surgery on surrogate markers of bone turnover

One study in adolescents undergoing gastric bypass reported an increase in levels of bone turnover markers, both carboxy-terminal cross-linking telopeptide of type 1 collagen (CTX) (a bone resorption marker) and osteocalcin (a bone formation marker), in the first year, followed by a modest decrease in the second year (11). Similar increases in CTX and osteocalcin were reported in 99 adolescents over a year following sleeve gastrectomy, with excess weight loss at 6 months (but not change in 25(OH) vitamin D [25OHD], calcium or parathyroid hormone levels) predicting increases in CTX (45). CTX levels decreased between 6 and 12 months in this study. It is unclear how these bone turnover markers change over a longer period following bariatric surgery, and how they may impact long-term outcomes in adolescents.

Impact of metabolic and bariatric surgery on marrow adipose tissue

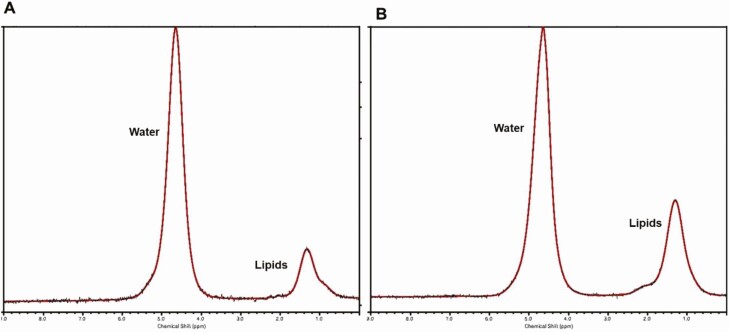

Skeletal integrity is determined not only by BMD but also by its microenvironment. Recent studies have identified MAT as a dynamic endocrine organ that responds to nutritional challenges and might serve as a novel biomarker for bone quality (26, 29–31). Adolescence is a time of conversion of hematopoietic (red) to fatty (yellow) marrow (46). Two types of MAT have been described, which differ by skeletal site and composition. Regulated MAT (rMAT), which responds to environmental stimuli such as nutritional, hormonal, and weight changes, is found in the proximal skeleton and contains more saturated lipids than constitutive MAT (cMAT), which is comparatively more inert, and is found in distal skeletal sites and contains more unsaturated lipids (47). MAT content and composition can be quantified using magnetic resonance imaging or 1H-MRS (48, 49). Only 1 study has examined MAT content and composition following bariatric surgery in adolescents (12). In this study, 1H-MRS of the lumbar spine, the femur, and distal tibia was performed in 26 adolescents undergoing sleeve gastrectomy and 26 controls with obesity followed without surgery at baseline and after 1 year (12). MAT content and composition behaved differently in the axial vs peripheral skeleton. Axial lumbar total MAT content and unsaturated MAT increased following sleeve gastrectomy compared with controls (Fig. 4), while saturated MAT increased after sleeve gastrectomy, but the change between groups only showed a trend. In the peripheral skeleton, total and saturated femoral and tibial MAT decreased following sleeve gastrectomy compared with controls while unsaturated MAT of the femur decreased within the sleeve gastrectomy group. Of note, in the control group, peripheral MAT content increased, which is consistent with the expected physiologic conversion of hematopoietic to fatty marrow during adolescence (12).

Figure 4.

Marrow adipose tissue (MAT) of the lumbar spine pre- and postsleeve gastrectomy. 1H-MRS of the lumbar spine in an 18-year-old female prior to (A) and 12 months after sleeve gastrectomy (B). Marrow adipose tissue (MAT) content in lipid to water ratio (LWR) of L1 increased following sleeve gastrectomy (MAT presurgery, 0.20 LWR; MAT postsurgery, 0.41 LWR). For purposes of visual comparison, the amplitudes of unsuppressed water are scaled identically.

Factors contributing to bone outcomes following metabolic and bariatric surgery

Weight and body composition changes

Weight loss and associated changes in body composition, including reductions in fat and lean mass, are important determinants of bone density following MBS. Strong associations between the extent of weight loss after MBS and the amount of bone loss has been demonstrated in adults (21, 50). In adolescents undergoing RYGB, weight loss during the first 12 months after surgery was correlated with a reduction in BMC (r = 0.31, P = .02), and weight loss accounted for 14% of the decrease in BMC (13). Another study examining adolescents 2 years after RYGB showed a mean reduction in weight by 42.6 kg and BMI by 15.1 kg/m2 (11). Body composition, assessed by DXA, changed 2 years following surgery with a reduction in fat mass from 51.8% at baseline to 39.6% at 2 years (P < .001), while lean mass increased from 47.0% to 58.1% (P < .001). There was a significant correlation between 2-year change in BMD and weight (r = 0.53, P < .001) (11). Adolescents undergoing sleeve gastrectomy lost an average of 27.2 ± 1.8% body weight and 27.6 ± 1.9% BMI 12 months after surgery (14). Reductions in weight (BMI Z-score) and lean and fat mass were associated with reductions in femoral neck and total hip (but not lumbar spine) BMD Z-scores by DXA (P ≤ .01) (14), and with hip structural analysis measures at the narrow neck and intertrochanteric region (35). Reductions in weight and lean mass were associated with impaired trabecular and cortical microarchitecture of the distal tibia (P ≤ .042), and reductions in fat mass correlated with impaired tibial microarchitecture and reduced radial trabecular vBMD (P ≤ .039) (14).

In adolescents and young adults with obesity undergoing sleeve gastrectomy, differences between surgical and nonsurgical groups for changes in all DXA and many HRpQCT and hip structural analysis measures over a year (12, 14) were attenuated or no longer evident after controlling for changes in BMI. These data suggest that skeletal unloading (or metabolic and hormonal changes associated with weight loss) (21, 32, 37, 38, 51) may explain many observed changes following surgery.

Changes in calciotropic hormones

Malabsorption-related reductions in 25OHD levels and associated increases in parathyroid hormone were important contributors to impaired bone outcomes in adults and rodents in the early years of MBS, particularly following gastric bypass (32, 51). This led to clinical protocols for vitamin D supplementation postsurgery to maintain 25OHD levels in the normative range. In fact, supplementation is robust enough that 1 meta-analysis in adults reported an increase in calcium, phosphate, and 25OHD levels following sleeve gastrectomy (52). In adolescents and young adults undergoing sleeve gastrectomy, no differences were observed between groups for changes in calcium, phosphorus, or 25OHD levels over a year (12, 14), indicating that a decrease in 25OHD does not explain changes in bone density, geometry, and microarchitecture in these youth. Similarly, no changes in 25OHD levels were observed over 2 years in one study of adolescents following gastric bypass (11), although another study in adolescents and adults assessing calciotropic hormones following gastric bypass did report a decrease in 25OHD levels over a year of follow-up (53). However, it is clearly important to maintain 25OHD levels in the normative range, and in one study, decreases in 25OHD levels over a year were associated with increases in cortical porosity at peripheral sites, and decreases in tibial cortical and total vBMD for surgical participants following sleeve gastrectomy and nonsurgical participants considered together (14). Interestingly, the pediatric study assessing changes in hip structural analysis parameters following sleeve gastrectomy noted inverse associations of changes in 25OHD levels with changes in bone parameters over a year (12). The authors attribute this finding to reductions in weight and associated fat mass postsurgery, which would be associated with increases in systemic 25OHD levels (as 25OHD is sequestered in fat). Thus, the inverse association of 25OHD levels with bone parameters in this hip structural analysis study may just reflect positive associations of weight and fat mass changes with bone parameters.

Changes in enteric peptides and other hormones

Many enteric and pancreatic hormones have a direct effect on osteoblasts. Insulin is a bone anabolic hormone (54, 55) which increases in obesity (56), coincident with increasing insulin resistance. Insulin levels are a determinant of bone density in other populations (57), and a reduction in insulin following weight loss after gastric bypass and sleeve gastrectomy could be an important determinant of bone loss. Ghrelin is an orexigenic hormone produced in the gastric fundus, and levels are low in obesity (58), and increase in conditions of weight loss (59). Sleeve gastrectomy involves resection of the gastric fundus, and therefore is associated with reductions in ghrelin (60, 61), despite weight reduction (60). This effect is not seen with gastric banding (60), and variably with RYGB (61). Ghrelin has receptors on osteoblasts and increases osteoblastic activity (62, 63). Thus, reductions in ghrelin may be greater following sleeve gastrectomy than RYGB in adolescents with obesity and may be deleterious to bone. Peptide YY (PYY), an anorexigenic hormone, is lower in individuals with obesity versus controls (58, 64) and increases in adults following RYGB (65) and sleeve gastrectomy (61). PYY inhibits osteoblast bone formation and PYY–/– mice have increased bone mass (66). Furthermore, higher PYY levels in conditions of severe weight loss are associated with lower levels of bone formation markers and lower BMD (59, 67). Data are limited regarding the impact of RYGB and sleeve gastrectomy–induced weight loss on enteric/ pancreatic peptides in relation to bone in adolescents and need to be studied.

Further, adipose tissue is a site of peripheral aromatization of gonadal/adrenal androgens to estradiol/estrone. Estrogen primarily inhibits bone resorption, but also impacts bone through effects on sclerostin and preadipocyte factor-1 (Pref-1). Sclerostin is an osteocyte paracrine factor that regulates the response to skeletal loading by inhibiting Wnt signaling and thus osteoblast differentiation (68). Pref-1 is a transcription factor that decreases osteoblast differentiation and also affects adipogenesis (69). Estrogen is negatively associated with sclerostin and inhibits Pref-1 (70–72). Thus, reductions in estrogen subsequent to decreased adipose tissue following RYGB and sleeve gastrectomy may cause bone loss through increased bone resorption and increased secretion of sclerostin and Pref-1. Data are lacking in adolescents regarding the impact of MBS on changes in these hormones in the context of changes in bone parameters.

Changes in physical activity

Overall activity did not correlate with changes in DXA measures of aBMD and HRpQCT measures of vBMD, bone geometry, and microarchitecture in youth following sleeve gastrectomy. However, changes in activity levels did correlate positively with changes in subperiosteal width and endocortical diameter at the narrow neck (on hip structural analysis) (12, 14).

Strategies to optimize bone outcomes following metabolic and bariatric surgery

Until more data are available regarding the impact of changes in enteric peptides and other hormones on bone outcomes following MBS, important strategies to optimize bone outcomes in youth include optimizing 25OHD levels in the postsurgical period and mechanical loading via weight bearing activity, particularly impact loading activities, which are known to activate osteocytes and therefore bone formation (by reducing sclerostin levels, which are reported to increase postgastric bypass in adults (73)). In fact, a randomized controlled trial in adults undergoing gastric bypass of 6 months of supervised exercise training versus standard care demonstrated that exercise reduced bone loss following surgery, likely by suppressing sclerostin and bone turnover (74). Similarly, another study in adults undergoing gastric bypass or sleeve gastrectomy showed that vitamin D loading, nutritional supplementation and obligatory physical exercise together led to lesser increases in sclerostin and bone turnover markers and lesser decrease in aBMD measures than observed in the group that received routine care (75). Such studies are necessary in youth undergoing bariatric surgery to determine whether similar strategies can mitigate deleterious postsurgical effects on bone.

Limitations

Limitations of this mini-review include the limited studies to date that have examined bone outcomes following MBS; these include 2 studies in patients following gastric bypass (11, 13), 1 after intragastric balloon placement (34), and 1 after sleeve gastrectomy (14) for DXA measures of aBMD, 1 in patients undergoing sleeve gastrectomy for HRpQCT (14), 1 for hip structural analysis outcomes (35), and 1 each following gastric bypass, gastric banding, and sleeve gastrectomy for bone marker outcomes (11, 45). While a meta-analysis of available data would be helpful, there are not enough studies at this time to perform a meta-analysis for a specific form of surgery or a specific outcome. Further, there is a lack of studies comparing the different kinds of MBS for bone outcomes, and the impact of age and sex on these outcomes.

Summary and Conclusion

Data are currently limited regarding the impact of MBS on bone outcomes in adolescents with obesity with only a handful of studies reporting data over 1 or 2 years of follow-up. Overall, studies indicate that several aBMD measures are impacted deleteriously over a year postsurgery. Moreover, vBMD of the lumbar spine decreases, associated with an increase in MAT a year after sleeve gastrectomy. In contrast, cortical vBMD at peripheral sites increases following sleeve gastrectomy, likely from a reduction in cortical porosity. Following sleeve gastrectomy, patients do not demonstrate the increase in cortical thickness and area observed during and after puberty in controls. Further, trabecular number decreases while trabecular separation increases at these sites. Youth undergoing sleeve gastrectomy do not demonstrate the expected increase in strength estimates observed in nonsurgical controls at the weight-bearing tibia. The strongest determinants of changes in bone parameters include changes in BMI, fat mass, and lean mass, with many differences between groups being attenuated after controlling for changes in BMI over the study duration. These data suggest that at least over the short term, bone changes following MBS may be adaptive to the reduced skeletal loading following weight loss and may not translate to reduced bone strength. Larger and longer term studies are necessary and are currently underway (76).

Acknowledgment

Financial Support: This work was funded in part by support from National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants NIDDK R01 DK103946-01A1 (M.M., M.A.B.) and K24DK109940 (M.A.B.).

Glossary

Abbreviations

- 1H-MRS

proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy

- 25OHD

25(OH) vitamin D

- a

areal

- BMD

bone mineral density

- BMC

bone mineral content

- BMI

body mass index

- c

constitutive

- CTX

carboxy-terminal cross-linking telopeptide of type 1 collagen

- DXA

dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry

- MAT

marrow adipose tissue

- MBS

metabolic and bariatric surgery

- Pref-1

preadipocyte factor-1

- QCT

quantitative computed tomography

- r

regulated

- RYGB

Roux-en-Y gastric bypass

- v

volumetric

Additional Information

Disclosure Summary: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare in the context of the contents of this manuscript.

Data Availability

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

References

- 1. Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Flegal KM. Prevalence of childhood and adult obesity in the United States, 2011-2012. JAMA. 2014;311(8):806-814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Simmonds M, Llewellyn A, Owen CG, Woolacott N. Predicting adult obesity from childhood obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev. 2016;17(2):95-107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Llewellyn A, Simmonds M, Owen CG, Woolacott N. Childhood obesity as a predictor of morbidity in adulthood: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev. 2016;17(1):56-67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mossberg HO. 40-year follow-up of overweight children. Lancet. 1989;2(8661):491-493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Must A, Jacques PF, Dallal GE, Bajema CJ, Dietz WH. Long-term morbidity and mortality of overweight adolescents. A follow-up of the Harvard Growth Study of 1922 to 1935. N Engl J Med. 1992;327(19):1350-1355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Whitlock E, O’Connor E, Williams S, Beil T, Lutz K. Effectiveness of weight management programs in children and adolescents. Evid Rep Technol Assess (Full Rep). 2008;(170):1-308. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Tsai WS, Inge TH, Burd RS. Bariatric surgery in adolescents: recent national trends in use and in-hospital outcome. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2007;161(3):217-221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Michalsky M, Reichard K, Inge T, Pratt J, Lenders C; American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery . ASMBS pediatric committee best practice guidelines. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2012;8(1):1-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chang SH, Stoll CR, Song J, Varela JE, Eagon CJ, Colditz GA. The effectiveness and risks of bariatric surgery: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis, 2003-2012. JAMA Surg. 2014;149(3):275-287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Skinner AC, Ravanbakht SN, Skelton JA, Perrin EM, Armstrong SC. Prevalence of obesity and severe obesity in US children, 1999–2016. Pediatrics. 2018;141(3):e20173459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Beamish AJ, Gronowitz E, Olbers T, Flodmark CE, Marcus C, Dahlgren J. Body composition and bone health in adolescents after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass for severe obesity. Pediatr Obes. 2017;12(3):239-246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bredella MA, Singhal V, Karzar NH, et al. Effects of sleeve gastrectomy on bone marrow adipose tissue in adolescents and young adults with obesity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2020;105(11):e3961-70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kaulfers AM, Bean JA, Inge TH, Dolan LM, Kalkwarf HJ. Bone loss in adolescents after bariatric surgery. Pediatrics. 2011;127(4):e956-e961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Misra M, Singhal V, Carmine B, et al. Bone outcomes following sleeve gastrectomy in adolescents and young adults with obesity versus non-surgical controls. Bone. 2020;134:115290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bonjour JP, Chevalley T. Pubertal timing, bone acquisition, and risk of fracture throughout life. Endocr Rev. 2014;35(5):820-847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Javed F, Yu W, Thornton J, Colt E. Effect of fat on measurement of bone mineral density. Int J Body Compos Res. 2009;7(1):37-40. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Maïmoun L, Mariano-Goulart D, Jaussent A, et al. The effect of excessive fat tissue on the measure of bone mineral density by dual X-ray absorptiometry: the impact of substantial weight loss following sleeve gastrectomy. Clin Physiol Funct Imaging. 2019;39(5):345-354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Yu EW, Thomas BJ, Brown JK, Finkelstein JS. Simulated increases in body fat and errors in bone mineral density measurements by DXA and QCT. J Bone Miner Res. 2012;27(1):119-124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Carrasco F, Basfi-Fer K, Rojas P, et al. Changes in bone mineral density after sleeve gastrectomy or gastric bypass: relationships with variations in vitamin D, ghrelin, and adiponectin levels. Obes Surg. 2014;24(6):877-884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Coates PS, Fernstrom JD, Fernstrom MH, Schauer PR, Greenspan SL. Gastric bypass surgery for morbid obesity leads to an increase in bone turnover and a decrease in bone mass. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89(3):1061-1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Fleischer J, Stein EM, Bessler M, et al. The decline in hip bone density after gastric bypass surgery is associated with extent of weight loss. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93(10):3735-3740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Yu EW. Bone metabolism after bariatric surgery. J Bone Miner Res. 2014;29(7):1507-1518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Yu EW, Bouxsein ML, Putman MS, et al. Two-year changes in bone density after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;100(4):1452-1459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Schellinger D, Lin CS, Hatipoglu HG, Fertikh D. Potential value of vertebral proton MR spectroscopy in determining bone weakness. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2001;22(8):1620-1627. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Schellinger D, Lin CS, Lim J, Hatipoglu HG, Pezzullo JC, Singer AJ. Bone marrow fat and bone mineral density on proton MR spectroscopy and dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry: their ratio as a new indicator of bone weakening. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2004;183(6):1761-1765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bredella MA, Fazeli PK, Miller KK, et al. Increased bone marrow fat in anorexia nervosa. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94(6):2129-2136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Abdalrahaman N, McComb C, Foster JE, et al. The relationship between adiposity, bone density and microarchitecture is maintained in young women irrespective of diabetes status. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2017;87(4):327-335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Singhal V, Maffazioli GD, Cano Sokoloff N, et al. Regional fat depots and their relationship to bone density and microarchitecture in young oligo-amenorrheic athletes. Bone. 2015;77:83-90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Bredella MA, Torriani M, Ghomi RH, et al. Vertebral bone marrow fat is positively associated with visceral fat and inversely associated with IGF-1 in obese women. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2011;19(1):49-53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Yu EW, Greenblatt L, Eajazi A, Torriani M, Bredella MA. Marrow adipose tissue composition in adults with morbid obesity. Bone. 2017;97:38-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bredella MA, Gill CM, Gerweck AV, et al. Ectopic and serum lipid levels are positively associated with bone marrow fat in obesity. Radiology. 2013;269(2):534-541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Stein EM, Silverberg SJ. Bone loss after bariatric surgery: causes, consequences, and management. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2014;2(2):165-174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Nakamura KM, Haglind EG, Clowes JA, et al. Fracture risk following bariatric surgery: a population-based study. Osteoporos Int. 2014;25(1):151-158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Sachdev P, Reece L, Thomson M, et al. Intragastric balloon as an adjunct to lifestyle programme in severely obese adolescents: impact on biomedical outcomes and skeletal health. Int J Obes (Lond). 2018;42(1):115-118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Misra M, Animashaun A, Bose A, Singhal V, Stanford FC, Carmine B, Bredella MA. Impact of sleeve gastrectomy on hip structural analysis in adolescents and young adults with obesity. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2020;16(12):2022-2030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Lindeman KG, Greenblatt LB, Rourke C, Bouxsein ML, Finkelstein JS, Yu EW. Longitudinal 5-Year Evaluation of Bone Density and Microarchitecture After Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass Surgery. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2018;103(11):4104-4112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Stein EM, Carrelli A, Young P, et al. Bariatric surgery results in cortical bone loss. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98(2):541-549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Shanbhogue VV, Støving RK, Frederiksen KH, et al. Bone structural changes after gastric bypass surgery evaluated by HR-pQCT: a two-year longitudinal study. Eur J Endocrinol. 2017;176(6):685-693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Gabel L, Macdonald HM, McKay HA. Sex differences and growth-related adaptations in bone microarchitecture, geometry, density, and strength from childhood to early adulthood: a mixed longitudinal HR-pQCT Study. J Bone Miner Res. 2017;32(2):250-263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Nishiyama KK, Macdonald HM, Moore SA, Fung T, Boyd SK, McKay HA. Cortical porosity is higher in boys compared with girls at the distal radius and distal tibia during pubertal growth: an HR-pQCT study. J Bone Miner Res. 2012;27(2):273-282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Singhal V, Sanchita S, Malhotra S, et al. Suboptimal bone microarchitecure in adolescent girls with obesity compared to normal-weight controls and girls with anorexia nervosa. Bone. 2019;122:246-253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Frederiksen KD, Hanson S, Hansen S, et al. Bone structural changes and estimated strength after gastric bypass surgery evaluated by HR-pQCT. Calcif Tissue Int. 2016;98(3):253-262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Erlandson MC, Runalls SB, Jackowski SA, Faulkner RA, Baxter-Jones ADG. Structural strength benefits observed at the hip of premenarcheal gymnasts are maintained into young adulthood 10 years after retirement from the sport. Pediatr Exerc Sci. 2017;29(4):476-485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Yu EW, Lee MP, Landon JE, Lindeman KG, Kim SC. Fracture risk after bariatric surgery: Roux-en-Y gastric bypass versus adjustable gastric banding. J Bone Miner Res. 2017;32(6):1229-1236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Weiner A, Cowell A, McMahon DJ, et al. The effects of adolescent laparoscopic adjustable gastric band and sleeve gastrectomy on markers of bone health and bone turnover. Clin Obes. 2020;10(6):e12411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Moore SG, Dawson KL. Red and yellow marrow in the femur: age-related changes in appearance at MR imaging. Radiology. 1990;175(1):219-223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Scheller EL, Doucette CR, Learman BS, et al. Region-specific variation in the properties of skeletal adipocytes reveals regulated and constitutive marrow adipose tissues. Nat Commun. 2015;6:7808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Bredella MA, Fazeli PK, Daley SM, et al. Marrow fat composition in anorexia nervosa. Bone. 2014;66:199-204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Singhal V, Bredella MA. Marrow adipose tissue imaging in humans. Bone. 2019;118:69-76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Vilarrasa N, Gómez JM, Elio I, et al. Evaluation of bone disease in morbidly obese women after gastric bypass and risk factors implicated in bone loss. Obes Surg. 2009;19(7):860-866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Canales BK, Schafer AL, Shoback DM, Carpenter TO. Gastric bypass in obese rats causes bone loss, vitamin D deficiency, metabolic acidosis, and elevated peptide YY. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2014;10(5):878-884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Jaruvongvanich V, Vantanasiri K, Upala S, Ungprasert P. Changes in bone mineral density and bone metabolism after sleeve gastrectomy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2019;15(8):1252-1260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Santos D, Lopes T, Jesus P, et al. Bone metabolism in adolescents and adults undergoing Roux-En-Y gastric bypass: a comparative study. Obes Surg. 2019;29(7):2144-2150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Malekzadeh B, Tengvall P, Ohrnell LO, Wennerberg A, Westerlund A. Effects of locally administered insulin on bone formation in non-diabetic rats. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2013;101(1):132-137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Zhang W, Shen X, Wan C, et al. Effects of insulin and insulin-like growth factor 1 on osteoblast proliferation and differentiation: differential signalling via Akt and ERK. Cell Biochem Funct. 2012;30(4):297-302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Misra M, Bredella MA, Tsai P, Mendes N, Miller KK, Klibanski A. Lower growth hormone and higher cortisol are associated with greater visceral adiposity, intramyocellular lipids, and insulin resistance in overweight girls. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2008;295(2):E385-E392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Misra M, Miller KK, Cord J, et al. Relationships between serum adipokines, insulin levels, and bone density in girls with anorexia nervosa. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92(6):2046-2052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Gueugnon C, Mougin F, Nguyen NU, Bouhaddi M, Nicolet-Guénat M, Dumoulin G. Ghrelin and PYY levels in adolescents with severe obesity: effects of weight loss induced by long-term exercise training and modified food habits. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2012;112(5):1797-1805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Misra M, Miller KK, Tsai P, et al. Elevated peptide YY levels in adolescent girls with anorexia nervosa. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91(3):1027-1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Langer FB, Reza Hoda MA, Bohdjalian A, et al. Sleeve gastrectomy and gastric banding: effects on plasma ghrelin levels. Obes Surg. 2005;15(7):1024-1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Karamanakos SN, Vagenas K, Kalfarentzos F, Alexandrides TK. Weight loss, appetite suppression, and changes in fasting and postprandial ghrelin and peptide-YY levels after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass and sleeve gastrectomy: a prospective, double blind study. Ann Surg. 2008;247(3):401-407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Fukushima N, Hanada R, Teranishi H, et al. Ghrelin directly regulates bone formation. J Bone Miner Res. 2005;20(5):790-798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Kim SW, Her SJ, Park SJ, et al. Ghrelin stimulates proliferation and differentiation and inhibits apoptosis in osteoblastic MC3T3-E1 cells. Bone. 2005;37(3):359-369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. le Roux CW, Batterham RL, Aylwin SJ, et al. Attenuated peptide YY release in obese subjects is associated with reduced satiety. Endocrinology. 2006;147(1):3-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Korner J, Inabnet W, Febres G, et al. Prospective study of gut hormone and metabolic changes after adjustable gastric banding and Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Int J Obes (Lond). 2009;33(7):786-795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Wong IP, Driessler F, Khor EC, et al. Peptide YY regulates bone remodeling in mice: a link between gut and skeletal biology. PLoS One. 2012;7(7):e40038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Utz AL, Lawson EA, Misra M, et al. Peptide YY (PYY) levels and bone mineral density (BMD) in women with anorexia nervosa. Bone. 2008;43(1):135-139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Ke HZ, Richards WG, Li X, Ominsky MS. Sclerostin and Dickkopf-1 as therapeutic targets in bone diseases. Endocr Rev. 2012;33(5):747-783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Sul HS. Minireview: Pref-1: role in adipogenesis and mesenchymal cell fate. Mol Endocrinol. 2009;23(11):1717-1725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Fujita K, Roforth MM, Demaray S, et al. Effects of estrogen on bone mRNA levels of sclerostin and other genes relevant to bone metabolism in postmenopausal women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99(1):E81-E88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Mirza FS, Padhi ID, Raisz LG, Lorenzo JA. Serum sclerostin levels negatively correlate with parathyroid hormone levels and free estrogen index in postmenopausal women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95(4):1991-1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Faje AT, Fazeli PK, Katzman D, et al. Inhibition of Pref-1 (preadipocyte factor 1) by oestradiol in adolescent girls with anorexia nervosa is associated with improvement in lumbar bone mineral density. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2013;79(3):326-332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Muschitz C, Kocijan R, Marterer C, et al. Sclerostin levels and changes in bone metabolism after bariatric surgery. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;100(3):891-901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Murai IH, Roschel H, Dantas WS, et al. Exercise mitigates bone loss in women with severe obesity after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2019;104(10):4639-4650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Muschitz C, Kocijan R, Haschka J, et al. The impact of vitamin d, calcium, protein supplementation, and physical exercise on bone metabolism after bariatric surgery: the BABS study. J Bone Miner Res. 2016;31(3):672-682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Bonouvrie DS, Beamish AJ, Leclercq WKG, et al. Laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass versus sleeve gastrectomy for teenagers with severe obesity - TEEN-BEST: study protocol of a multicenter randomized controlled trial. BMC Surg. 2020;20(1):117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.