Abstract

Context

Genetic variants in SLC16A2, encoding the thyroid hormone transporter MCT8, can cause intellectual and motor disability and abnormal serum thyroid function tests, known as MCT8 deficiency. The C-terminal domain of MCT8 is poorly conserved, which complicates prediction of the deleteriousness of variants in this region. We studied the functional consequences of 5 novel variants within this domain and their relation to the clinical phenotypes.

Methods

We enrolled male subjects with intellectual disability in whom genetic variants were identified in exon 6 of SLC16A2. The impact of identified variants was evaluated in transiently transfected cell lines and patient-derived fibroblasts.

Results

Seven individuals from 5 families harbored potentially deleterious variants affecting the C-terminal domain of MCT8. Two boys with clinical features considered atypical for MCT8 deficiency had a missense variant [c.1724A>G;p.(His575Arg) or c.1796A>G;p.(Asn599Ser)] that did not affect MCT8 function in transfected cells or patient-derived fibroblasts, challenging a causal relationship. Two brothers with classical MCT8 deficiency had a truncating c.1695delT;p.(Val566*) variant that completely inactivated MCT8 in vitro. The 3 other boys had relatively less-severe clinical features and harbored frameshift variants that elongate the MCT8 protein [c.1805delT;p.(Leu602HisfsTer680) and c.del1826-1835;p.(Pro609GlnfsTer676)] and retained ~50% residual activity. Additional truncating variants within transmembrane domain 12 were fully inactivating, whereas those within the intracellular C-terminal tail were tolerated.

Conclusions

Variants affecting the intracellular C-terminal tail of MCT8 are likely benign unless they cause frameshifts that elongate the MCT8 protein. These findings provide clinical guidance in the assessment of the pathogenicity of variants within the C-terminal domain of MCT8.

Keywords: monocarboxylate transporter 8, MCT8, Allan-Herndon-Dudley syndrome, AHDS, MCT8 deficiency, thyroid hormone transport

Thyroid hormone requires transporter proteins to facilitate its transport across the cell membrane (1, 2). Monocarboxylate transporter (MCT)8 is the most specific thyroid hormone transporter identified to date and facilitates the cellular uptake and efflux of 3,3′,5-triiodothyronine (T3) and thyroxine (T4) (3, 4). Genetic variants in the SLC16A2 gene, encoding MCT8, may result in MCT8 deficiency (Allan-Herndon-Dudley syndrome, AHDS, OMIM 300523) characterized by severe intellectual and motor disability and abnormal thyroid function tests (increased serum T3, reduced T4, and high-normal thyrotropin [TSH] concentrations) (5, 6). The profound neurocognitive phenotype has been attributed to impaired transport of thyroid hormone across the blood-brain barrier and into target cells in the brain (7, 8). Tissues that rely on transporters other than MCT8 are exposed to high serum T3 concentrations, resulting in classical signs of tissue thyrotoxicosis, such as impaired weight gain, tachycardia, and increased perspiration.

Over the last decade, there have been many reports of patients with MCT8 deficiency who harbor different underlying pathogenic variants in SLC16A2 (reviewed in (2, 9)). The majority of affected individuals exhibit severe intellectual disability, have poor head control, are unable to sit independently, and are nonverbal. However, some individuals are able to walk and talk in simple sentences (eg, (10)). Not all variants in SLC16A2 cause MCT8 deficiency, which may lead to misinterpretation of causality and diagnostic delay. Given the increased application of next-generation sequencing techniques in clinical practice, there is a growing need for tools that accurately differentiate disease causing variants from rare variants that have no impact on MCT8 function (11). For this purpose, in silico prediction tools, based on genetic conservation, are often used (eg, (12-15)). However, such tools frequently yield inconclusive results, especially when variants affect poorly conserved regions. This warrants complementary approaches to prove causality. Ideally this entails functional evaluation of the variant in overexpression models or patient-derived cells. Although these systems have proven to provide good disease models for MCT8 deficiency (eg, (16-18)), they are not ubiquitously available. Alternatively, knowledge on protein structure could help predicting the impact of variants on protein function, but crystal structures of MCT8 are not yet available. Although protein homology models have provided important insights into the structure-function relation of, particularly, the 12 transmembrane domains (TMD) of MCT8 (19-21), the available models lack the entire intracellular N- and C-terminal tails. The function of these domains is currently unknown, although they account for ~25% of the protein size. Insight into their functional relevance is crucial for the interpretation of novel variants in these regions.

Here, we studied the functional characteristics of 5 novel variants within the C-terminal domain of MCT8 and examined their relation to the observed phenotype in boys with developmental delay. We took advantage of these and additional premature stop variants to determine the minimal length of the C-terminal tail required for normal MCT8 function in vitro. Together, our findings provide important guidance in assessing the pathogenicity of variants within the C-terminal domain of the MCT8 protein.

Methods

Study design and participants

In this case series, we have included male individuals with intellectual disability in whom a genetic variant within exon 6 of the SLC16A2 gene, encoding TMD12 and the intracellular C-terminal tail of MCT8, had been identified in the context of routine diagnostic process and for whom the Erasmus Medical Center fulfilled a consultancy role between January 1, 2014 and January 1, 2020.

Genetic analysis

Genetic analyses had been carried out in the context of routine clinical practice using exome sequencing or target sequencing of the SLC16A2 gene (Xq13.2) according to standard methods. Nucleotides and amino acid residues were numbered according to the reference gene sequence of the transcript GenBank (NCBI) NM_006517.3 (NP_006508.1) with the A of the ATG translation initiation codon of the long MCT8 translational isoform regarded as nucleotide position +1 and the corresponding initiation coding as the first amino acid codon (referred to as long isoform; widely used reference sequence in the available literature on MCT8 deficiency), and according to the reference gene sequence of the transcript GenBank (NCBI) NM_006517.5 (NP_006508.2) (referred to as short isoform; the novel official reference sequence in Ensembl, HGMD, and gnomAD). In silico analysis of pathogenicity was performed using the PolyPhen-2 (http://genetics.bwh.harvard.edu/pph2/) (14), CADD (https://cadd.gs.washington.edu/) (13), PROVEAN (http://provean.jcvi.org/index.php) (12), and SIFT (http://sift.jcvi.org/) (15) prediction tools. NMDEscPredictor was used to predict if frameshift variants escape nonsense-mediated decay or degradation via non-stop RNA decay (https://nmdprediction.shinyapps.io/nmdescpredictor/) (22).

Materials

Unlabeled iodothyronines, silychristin, bovine serum albumin (BSA), and D-glucose were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (Zwijndrecht, The Netherlands [NL]). [125I]-T3 and [125I]-T4 were prepared as previously described (23). X-tremeGENE9 transfection reagent was obtained from Roche Diagnostics (Woerden, NL). Cell culture flasks and plates were obtained from Corning (Schiphol, NL). An overview of the antibodies is provided in Supplemental Table 1 (24). Sulfo-NHS-biotin was obtained from Gentaur (Eersel, NL). Neutravidin agarose was obtained from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Bleiswijk, NL).

Plasmids

The cloning of wild-type (WT) human MCT8 cDNA into pcDNA3 and human μ-crystallin (CRYM) into pSG5 has been described previously (4, 25). The generation of a WT human MCT8 expression construct containing a 227-nucleotide extension of the 3′UTR (further referred to as 3′UTR-MCT8) has been described before (26). The indicated variants were introduced using site-directed mutagenesis according to manufacturer’s protocol (Stratagene, Amsterdam, NL), using primers available upon request. The 3′UTR-MCT8 construct was used as a template for all frameshift variants that resulted in an alternate reading frame that exceeded the natural stop codon of MCT8, whereas the regular MCT8 expression construct was used as a template for all other variants. All constructs were sequenced to confirm the presence of the intended variant.

Cell culture and transfection

COS-1 African green monkey kidney (CVCL_0223) and JEG-3 human choriocarcinoma (CVCL_0363) cells were obtained from ECACC (Sigma-Aldrich) and were cultured and transiently transfected as previously described (20). For T3 uptake studies, COS-1 or JEG-3 cells were cultured in 24-well plates, and transiently transfected at 70% confluence with 100 ng pcDNA3 empty vector (EV), or 100 ng WT or indicated mutant MCT8 expression construct in the presence or absence of 50 ng CRYM. Kinetic studies were performed in the absence of CRYM. For surface biotinylation studies, cells were seeded in 6-well plates (6 wells per condition, which were pooled during lysate preparation) and transiently transfected with 500 ng pcDNA3 EV, WT, or indicated mutant MCT8 per well. For immunocytochemistry, JEG-3 cells were cultured in 24-well dishes on 10-mm glass coverslips coated with poly-D-lysine (Sigma-Aldrich).

Human fibroblasts were derived from skin biopsies and cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium/F12 medium (Invitrogen, Breda, NL), containing 9% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (Invitrogen), 2% penicillin/streptomycin (Roche, Woerden, The Netherlands). For uptake studies, fibroblasts were seeded in 6-well plates and grown until >95% confluence (27).

Thyroid hormone uptake studies

Thyroid hormone uptake studies were performed using well-established protocols (eg, (28)). Cells were washed once with incubation buffer (D-phosphate-buffered saline [PBS]+Ca2+/Mg2+ supplemented with 0.1% glucose and 0.1% BSA) and incubated in incubation buffer containing 1 nM (50 000 cpm) [125I]-T3 or [125I]-T4 for 30 minutes (standard uptake studies) or 10 minutes (kinetic studies). After indicated incubation times, cells were briefly washed with incubation buffer and lysed in 0.1 M sodium hydroxide. The internalized radioactivity was measured with a gamma-counter. Thyroid hormone uptake levels in human fibroblasts were corrected for total protein concentrations as measured by Bradford assay according to the manufacturer’s guidance (Bio-Rad, Veenendaal, NL).

Cell surface biotinylation and immunoblotting

Cell surface biotinylation studies were performed according to well-established protocols (20, 27). Cell surface proteins were labeled with Sulfo-NHS-biotin and lysed in IP buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, 150 mM NaCl, 10 mM EDTA, 1% Triton X-100), containing protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche). After brief sonication, samples were clarified from nuclear debris by centrifugation (15000g for 10 minutes). A 5% aliquot was used as an input control. Cell surface proteins were isolated using Neutravidin agarose beads (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and eluted in NuPAGE 1× lithium dodecyl sulfate loading buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) containing 10 mM dithiothreitol by incubating the beads for 5 minutes at 90 °C prior to immunoblot analyses. Samples were analyzed by immunoblotting as previously described (20, 27), using antibodies listed in Supplemental Table S1 and Odyssey detection methods (24). If indicated, 1 μmol of MG132 was added to the incubation medium 24 hours after transfection to inhibit proteasomal degradation.

Immunocytochemistry

Transiently transfected JEG-3 cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and permeabilized with 0.25% triton X-100 in PBS 48 hours after transfection. Samples were blocked for 1 hour at room temperature in PBS containing 2% BSA (Sigma-Aldrich), and incubated overnight with rabbit anti-MCT8 (1:1000) and mouse monoclonal ZO-1 antibody (1:500), which served as a membrane marker. After secondary staining with goat anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 488 (1:1000) and goat anti-mouse Alexa Fluor 633 (1:1000), cover slips were mounted on glass slides with Prolong Gold containing DAPI (Invitrogen) and examined as previously described (28).

Quantitative polymerase chain reaction

Total RNA was extracted from transfected JEG-3 cells cultured in 12-well plates using the High Pure RNA Isolation Kit (Roche Diagnostics), and cDNA was produced from 1 µg messenger RNA (mRNA) using the Transcriptor High Fidelity cDNA Synthesis Kit (Roche Diagnostics) according to the manufacturer`s protocol. Quantitative polymerase chain reaction was performed as previously described, using a probe-based assay for the detection of MCT8 and cyclophilin A (29). MCT8 expression levels are corrected for the housekeeping gene cyclophilin A and expressed as fold difference over 3′UTR-MCT8.

Ethical considerations

Skin fibroblasts were collected for diagnostic purposes by caregiving physicians. Clinical examinations were carried out in the context of routine care and were retrospectively described. Written informed consent was obtained from the parents or legal representatives of the involved patients to use their medical data for publication. This study was conducted in agreement with the Medical Research Involving Human Subjects Act and (if applicable) formal ethics approval was obtained from the relevant institutional ethical committee(s).

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism Version 5 software (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, USA). Transporter kinetics were determined using standard Michaelis-Menten equations implemented in GraphPad Prism. Statistically significant differences are indicated as described in the figure legends.

Results

Description of individuals with classical features of MCT8 deficiency

Probands P1 and P2 are dizygotic twins born to nonconsanguineous parents. Their initial presentation included severe developmental delay and feeding problems, necessitating percutaneous tube feeding from the first year of life. At time of referral, both boys were 7.5 years old and had not achieved any early developmental milestones (Table 1). Severe truncal hypotonia was present, accompanied by dystonic posturing and brisk tendon reflexes in the limbs. Because of severe spastic-dystonic movement disorder, intrathecal baclofen treatment was started at age 11 years. Language development was limited to some phonation. Scoliosis and gastric reflux disorder were present in both boys. Body height and weight were within low-normal range for age (Table 1). Resting heart rate was normal. Isolated systolic hypertension and increased perspiration were present in P1. Sequential brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed delayed myelination in both probands. Serum thyroid function tests at age 7.5 years showed, like those at age 2 years, the characteristic pattern of MCT8 deficiency, with high serum T3 concentrations and low (free) T4 and reverse T3 (rT3) concentrations (Table 1). In addition, serum sex-hormone–binding globulin concentrations were elevated and total cholesterol concentrations were low (Table 1).

Table 1.

Clinical Characteristics

| Proband | I | II | III | IV | V | VI | VII |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at assessment, years | 7.5 | 7.5 | 4.6 | 10 | 18 | 9.9 | 4.1 |

| Variant | |||||||

| Long isoform (NP_006508.1) | p.(Val566*) | p.(Val566*) | p.(Leu602HisfsTer680) | p.(Pro609GlnfsTer676) | p.(Pro609GlnfsTer676) | p.(His575Arg) | p.(Asn599Ser) |

| Short isoform (NP_006508.2) | p.(Val492*) | p.(Val492*) | p.(Leu528HisfsTer606) | p.(Pro535GlnfsTer602) | p.(Pro535GlnfsTer602) | p.(His501Arg) | p.(Asn525Ser) |

| Birth weight in grams (percentiles) | NA | NA | NA (p15) | 3080 (NA) | 2820 (NA) | 2780 (p4) | 3895 (p98) |

| Neurocognitive features | |||||||

| Dystonia | ++ | ++ | + | + | + | - | - |

| Spasticity | + | + | +/- | + | + | - | - |

| Hypotonia | ++ | ++ | + | + | + | +/- | - |

| Head circumference, cm (SD) | 52.5 (−0.0) | 51 (−1.1) | 51 (0.3) | 54.5 (1.0) | 52 (−2.8) | 47.5 (−4.2) | 50 (0.8) |

| Speech development | Absent | Absent | Some words | No verbal speech | No verbal speech | Few words | Sentences (delayed) |

| Head control | - | - | + | +/- | + | + | + |

| Sitting independently | - | - | +/- | - | - | + (11 m) | + |

| Walking independently | - | - | - | - | - | + (4y6m) | + (22 m) |

| Delay in achieving motor milestones | Severe | Severe | Severe | Severe | Severe | Severe | Mild |

| GMFM-G88 score (%)1 | 7 | 8 | 29.7 | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| IQ score (test) | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| Psychiatric symptoms | ND | ND | - | Irritability | Irritability, aggressive | - | - |

| EEG-proven seizures | - | - | - | + | + | + | - |

| Feeding problems | + | + | + | + | + | + | - |

| Brain MRI abnormalities | Delayed myelination | Delayed myelination | - | - | PV WMHI, choroid cyst | - | - |

| Biochemical features | |||||||

| Total T3 in nmol/L (NR) | 6.4 (2.0-3.3) | 4.38 (2.0-3.3) | 3.47 (1.61-3.20) # | 3.05 (1.6-3.0)* | 3.73 (2.0-3.3) ‡ | 2.44 (2.0-3.3) * | 2.26 (2.0-3.3) † |

| Total T4 in nmol/L (NR) | 54 (74-151) | 41 (74-151) | 42.5 (57.9-154.5) # | 79 (62-136)* | 57 (74-151) ‡ | 81 (74-151)* | 82 (74-151) † |

| Free T4 in pmol/L (NR) | 6.6 (13-26) | 6.4 (13-26) | 11.6 (11.6-18) # | 12.3 (12-24)* | 9.7 (13-26) ‡ | 15.6 (13-26) * | 17.6 (13-26) † |

| Total rT3 in nmol/L (NR) | 0.11 (0.2-0.5) | 0.10 (0.2-0.5) | 0.08 (0.12-0.38) # | 0.19 (0.2-0.5)* | 0.11 (0.2-0.5) ‡ | 0.37 (0.2-0.5)* | 0.24 (0.2-0.5) † |

| TSH in mU/L (NR) | 4.42 (0.6-5.6) | 5.19 (0.6-5.6) | 3.02 (0.5-4.3) # | 1.22 (0.6-5.2) * | 3.90 (0.6-5.6) ‡ | 0.94 (0.6-5.6)* | 2.47 (0.6-5.6) † |

| SHBG in nmol/L (NR) | 275 (40-140) | 282 (40-140) | 163 (40-140) # | ND | 214.6 (40-140)** | 149.9 (40-140)* | ND |

| Total cholesterol in mmol/L (NR) | 2.1 (2.8-5.4) | 2.7 (2.8-5.4) | ND | ND | ND | ND | 4.0 (2.8-5.4) † |

| Peripheral features | |||||||

| Tachycardia in rest | - | - | + | ND | ND | - | - |

| Body weight in kg (SD) | 21.2 (−1.5) | 22.0 (−1.2) | 14.5 (−1.6) | 25 (−1.5) | 26.5 (−8.5) | 19.5 (−3.2) | 17.8 (0.1) |

| Body height in cm (SD) | 115 (−2.6) | 115 (−2.6) | 109 (0.2) | 133.5 (−0.8) | 137 (−4.0) | 123.4 (−1.9) | 107.5 (0.3) |

| BMI in kg/m2 (SD) | 16.03 (0.5) | 16.64 (0.9) | 12.2 (−2.8) | 14.0 (−2.0) | 14.1 (<−3.0) | 12.8 (−2.7) | 15.4 (−0.1) |

| Increased perspiration | + | - | - | + | - | - | - |

| Diarrhea | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

MCT8 variants are indicated based on the long isoform reference sequence (NP_006508.1), widely used in existing literature on MCT8 deficiency, and on the short isoform reference sequence (NP_006508.2), that is the novel approved reference sequence used in publicly available genetic databases.

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; NA, not available; ND, not determined; NR, normal range for age; PV WMH, periventricular white matter hyper-intensities; rT3, reverse triiodothyronine; SD, standard deviation; SHBG, sex hormone–binding globulin; T3, 3,3′,5-triiodothyronine; T4, thyroxine; TSH, thyrotropin (thyroid-stimulating hormone).

1 GMFM-G88 is Gross Motor Function Measure-G88 which assesses the gross motor function. Scores range from 0 to 100%, with higher scores indicating better motor function and where a 100% score is achieved by a healthy child of 4 years of age. Thyroid function tests at the age of 7.5 years (*), 5 years (†), 3 years (#) or 15 years (‡). SHBG at the age of 16 years (**). Z scores of anthropomorphic parameters are derived from national references growth curves.

P3 is a currently 4.5-year-old boy born to nonconsanguineous parents, who presented global developmental delay and failure to thrive. The presence of generalized hypotonia and delayed motor development prompted referral to the pediatric neurologist by the age of 14 months. At that time, he was able to roll over and had attained head control. Brain MRI was reportedly normal. Electroencephalography (EEG) revealed a slow background pattern, but no epileptic activity despite the presence of staring spells. At time of last evaluation at the age of 4.5 years, he was able to briefly stand independently and understand verbal commands. He had been able to speak in words, but with poor articulation. This recently regressed to babbling. Despite his ability to maintain body posturing, truncal hypotonia was present. His initial growth was unremarkable, but at the last evaluation, he has difficulty gaining weight. Tachycardia was present in rest. Serum thyroid function tests showed the classical pattern of MCT8 deficiency (Table 1).

P4 and his older half-brother P5 were born to nonconsanguineous parents and have the same biological mother, but different fathers. Both boys presented developmental delay with truncal hypotonia, dystonic posturing, and spasticity. P5 achieved full head control at the age of 1 year, although he never acquired independent sitting. Dysmorphic features include elongated face, with prominent ears in both boys and pectus excavatum in P4. Orchidopexy was performed for treatment of retractile and undescended testes in P4 and P5, respectively. Body weight was low for age, and particularly P5 was severely underweight. Irritability was present in both boys. Measurement of thyroid hormone function tests revealed a marginally increased T3, a low-normal free T4 and normal TSH in P4, and a marginally increased T3, low free T4 and normal TSH in P5 (Table 1). Notably, also serum sex hormone–binding globulin was elevated in P5.

Description of individuals without distinctive features of MCT8 deficiency

P6 presented at the age of 7 years with severe intellectual disability, microcephaly, and a low body weight for age. Motor development was delayed. Independent sitting was achieved by the age of 11 months and he was able to walk independently by the age of 4 years. He was able to speak his first words by the age of 5 years. By the age of 8 years, he developed tonic-clonic seizures with epileptic abnormalities detectable on EEG. At the time of his last evaluation at the age of 9 years and 4 months, he still exhibited mild clumsiness with difficulties in climbing the stairs and he could only speak 3 to 4 words. Social interaction was normal. Body weight was low for age (−3.23 SD) and height was within the low-normal range (−1.9 SD). He did not present either marked hypotonia, or spasticity and dystonic features. Brain MRI performed at 12 months and 3 years of age were normal. Thyroid function tests at the age of 7 years exhibited serum T3 concentrations within normal range and (free) T4 concentrations at the lower end of the normal range (Table 1).

P7 presented at the age of 4 years with mild global developmental delay without additional health problems other than recurrent upper respiratory tract infections. Achievement of motor milestones and speech was delayed. He was 5 years at time of referral when he was able to walk and jump and speak in simple sentences. He reportedly had reduced exercise tolerance and was unable to walk for long distances. Mild swallowing difficulties were reported by his parents. He did not present hypotonia and dystonic and spastic features were absent, although he reportedly experienced increased muscle tone during emotional distress. Seizures and signs of peripheral thyrotoxicosis were absent (Table 1). Serum T3 concentrations were within normal range, whereas serum rT3 and (free) T4 concentrations were at the lower end of the normal range (Table 1).

Full details on probands P6 and P7 are available in the Supplemental Results section (24).

Genetic studies

Based on their clinical and biochemical features, DNA of probands P1 through P5 was tested for variants in SLC16A2. In P6 and P7, exome sequencing was performed in the context of developmental delay with unknown cause. The results of the sequencing analyses are graphically depicted in Fig. 1A and 1B, as well as Supplemental Fig. S1 (24). All variants are indicated throughout the manuscript and figures based on the long isoform reference sequence (NM_006517.3, NP_006508.1) to facilitate comparison with previously published studies on MCT8 deficiency. A c.1695delT variant was found in P1 and P2, resulting in a frameshift and premature truncation of the MCT8 protein at the next codon (p.(Val566*) [corresponding to c.1473delT;p.(Val492*) according to the short isoform reference sequence]. In P3, a single nucleotide deletion (c.1805delT) was identified in exon 6, resulting in a frameshift and elongation of the MCT8 protein p.(Leu602HisfsTer680) [corresponding to c.1583delT;p.(Leu528HisfsTer606) according to the short isoform reference sequence]. In P4 and P5, a deletion of 10 nucleotides (c.del1826-1835) was found in exon 6, causing a frameshift and elongation of the MCT8 protein (p.(Pro609GlnfsTer676) [corresponding to c.del1604-1613;p.(Pro535GlnfsTer602) according to the short isoform reference sequence]. The unaffected mother was heterozygous for the same variant. All 3 frameshift variants were predicted to be deleterious (Table 2). The p.(Val566*) variant was predicted to escape nonsense-mediated decay, whereas the p.(Leu602HisfsTer680) and p.(Pro609GlnfsTer676) variants might be subject to non-stop RNA degradation. In P6, exome sequencing was performed on both affected members of the family and their parents. A hemizygous c.1724A>G variant was identified resulting in substitution of His575 by an Arg [p.(His575Arg) (corresponding to c.1502A>G;p.(His501Arg) according to the short reference sequence]. This variant was inherited through his unaffected mother and has an allele frequency of 21/205358 (0.01%) alleles according to the gnomAD database (https://gnomad.broadinstitute.org/; dd 04-05-2020), with 8 hemizygous subjects reported. Subsequent segregation sequence analysis also revealed the presence of this variant in a nonaffected maternal male cousin. Exome sequencing in P7 revealed a novel c.1796A>G variant, which results in the substitution of Asn599 by a Ser (p.(Asn599Ser) [corresponding to c.1574A>G;p.(Asn525Ser) according to the short reference sequence]. This variant was also found in the healthy mother and maternal grandmother and absent in 2 healthy brothers of the maternal grandmother. The His575 and Asn599 are both highly conserved among species (Supplemental Fig. S2) (24). Frequently used in silico prediction tools showed considerable variation in the predicted pathogenicity of both missense variants, resulting in an initial classification as variants of unknown significance (Table 2).

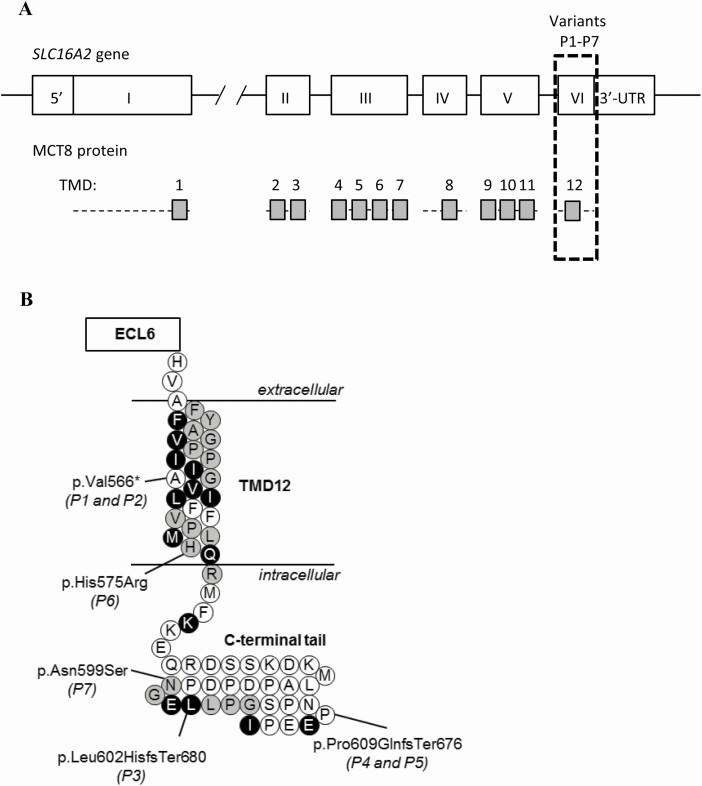

Figure 1.

(A) Schematic representation of the SLC16A2 gene and MCT8 protein. The transmembrane domains (TMDs) are displayed as grey boxes and aligned to their coding exons. All variants identified in this study locate to exon 6 (boxed with dashed lines). (B) Schematic representation of TMD12 and the intracellular C-terminal tail. The locations of the identified variants are indicated, according to the reference sequence of the long isoform (NM_006517.3, NP_006508.1). Strongly conserved residues are colored black, whereas those with strongly similar properties across species are colored grey (see Supplemental Fig. 2 for detailed alignment (24)). Abbreviations: ECL, extracellular loop.

Table 2.

In Silico Deleteriousness Prediction of the Identified SLC16A2 Variants

| Proband | Variant | PROVEAN (12) | CADD (13) | PolyPhen2 (14) | SIFT (15) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1, P2 | p.(Val566*) | Deleterious (−44.7) | NA | NA | NA |

| P3 | p.(Leu602HisfsTer680) | Deleterious (−16.3) | NA | NA | NA |

| P4, P5 | p.(Pro609GlnfsTer676) | Deleterious (−9.0) | NA | NA | NA |

| P6 | p.(His575Arg) | Deleterious (−3.4) | Possibly deleterious (21.9) | Benign (0.04) | Tolerated (0.33) |

| P7 | p.(Asn599Ser) | Neutral (−1.8) | Possibly deleterious (23.5) | Possibly deleterious (0.21) | Tolerated (0.12) |

In silico prediction tools were used according to their online instructions. The following cutoffs were recommended. PROVEAN scores < -2.5 are considered deleterious. CADD scores >15 are generally regarded as possibly deleterious. PolyPhen-2 scores between 0.85–1.0 are considered deleterious, whereas scores between 0.15–0.85 are considered possibly deleterious. A SIFT score between 0.0–0.05 is considered deleterious, whereas scores between 0.05–1.0 are considered benign.

Functional analyses of identified variants

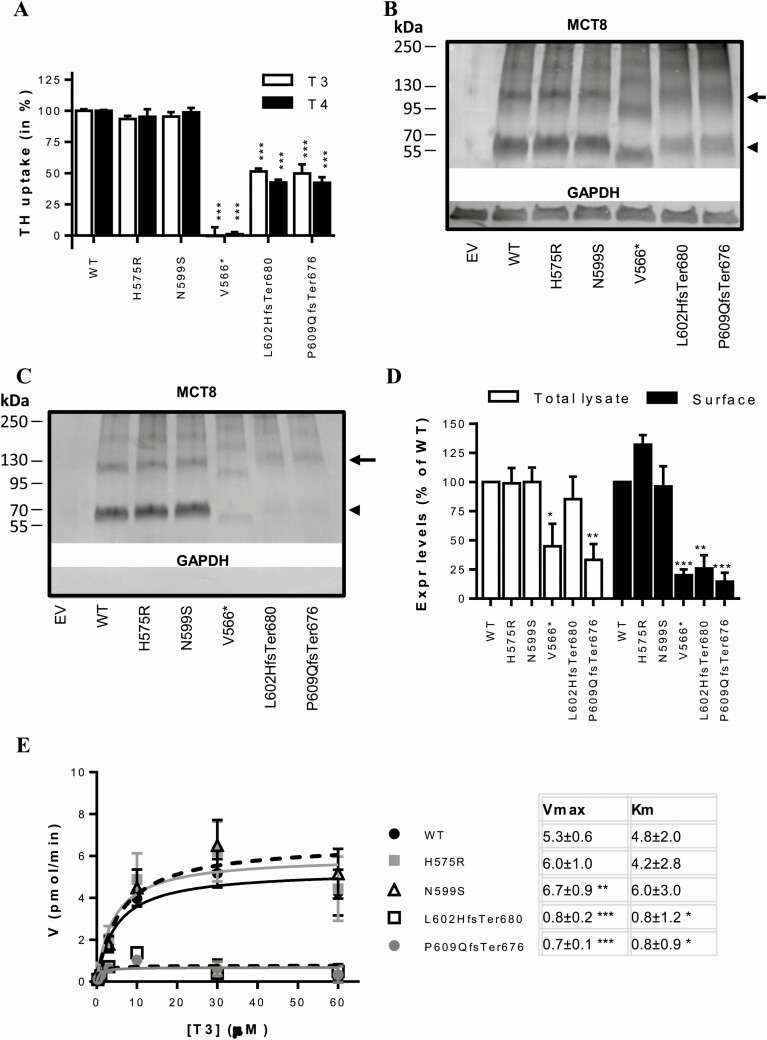

To investigate if the identified variants in SLC16A2 were causative for the observed clinical phenotype, MCT8 expression constructs harboring these variants were transiently overexpressed in COS-1 cells. MCT8-mediated T3 and T4 uptake in cells expressing His575Arg or Asn599Ser mutant MCT8 did not significantly differ from cells expressing WT MCT8 (Fig. 2A). The Leu602HisfsTer680 and Pro609GlnfsTer676 variants showed a ~50% reduction in T3 and T4 uptake compared with WT MCT8, whereas the Val566* variant was completely inactive (Fig. 2A and Supplemental Fig. S3A) (24). Expression levels of the His575Arg and Asn599Ser mutant MCT8 proteins did not differ from WT MCT8, whereas those of all 3 frameshift variants were lower than WT in total lysates of transfected COS-1 cells (Fig. 2B). Similarly, the expression levels of His575Arg and Asn599Ser mutant proteins at the cell membrane were equal to those observed for WT MCT8, whereas those of the frameshift variants were significantly reduced (Fig. 2C and 2D). Kinetic analyses of T3 transport showed that the apparent Km and Vmax of the His575Arg variant did not differ from WT, whereas the Asn599Ser variant showed a marginal increase in Vmax (Fig. 2E). In contrast, the Leu602HisfsTer680 and Pro609GlnfsTer676 variants significantly reduced the Vmax and Km of T3 transport by MCT8 (Fig. 2E). The kinetic properties of the Val566* mutant protein could not be studied due to the low residual uptake capacity.

Figure 2.

(A) T3 and T4 uptake in transiently transfected COS-1 cells in presence of the intracellular thyroid hormone-binding protein CRYM, after 30-minute incubation at 37 °C. Uptake levels are corrected for those observed in pcDNA3 empty vector (EV) transfected control cells and expressed relative to wild-type (WT) MCT8. Two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-tests were performed to assess for statistically significant differences between WT and indicated mutant MCT8. Data were derived from at least 3 independent repetitions in duplo. T3 and T4 uptake by WT MCT8 was not different from 3′UTR-MCT8 which was used to generate the Leu602HisfsTer680 and Pro609GlnfsTer676 variants and contains a 227-nucleotide extension of at 3′UTR (Supplemental Fig. S3A) (24). Immunoblot of total lysates (B) and biotinylated cell surface fraction (C) derived from COS-1 cells transiently transfected with WT or indicated mutant MCT8. The total lysate comprised a 5% input samples of the clarified lysate from which the presented surface fraction was derived. MCT8 monomers (arrowhead) and homodimers (arrow) are indicated. (D) Quantification of the total and cell surface expression levels of WT and mutant MCT8 monomers using densitometry (ImageJ). The means ± SEM from N = 2-3 independent experiments are displayed. Two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-tests were performed to assess for statistically significant differences between WT and indicated mutant MCT8. (E) Michaelis-Menten plots showing kinetic properties of WT and mutant MCT8 transiently expressed in COS-1 cells in the absence of CRYM. The uptake in cells transfected with pcDNA3 empty vector was subtracted as background. Incubations were performed for 10 minutes at 37 °C with increasing concentrations of T3. Data are expressed as means of 3 independent experiments performed in duplo +/- SEM. Apparent Km and Vmax values are summarized and were compared with those obtained for WT using 1-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s post-tests. All statistically significant differences are indicated as follows: (P < 0.05, *; P < 0.01, **, P < 0.005 ***). Amino acids are indicated using their single-letter codes.

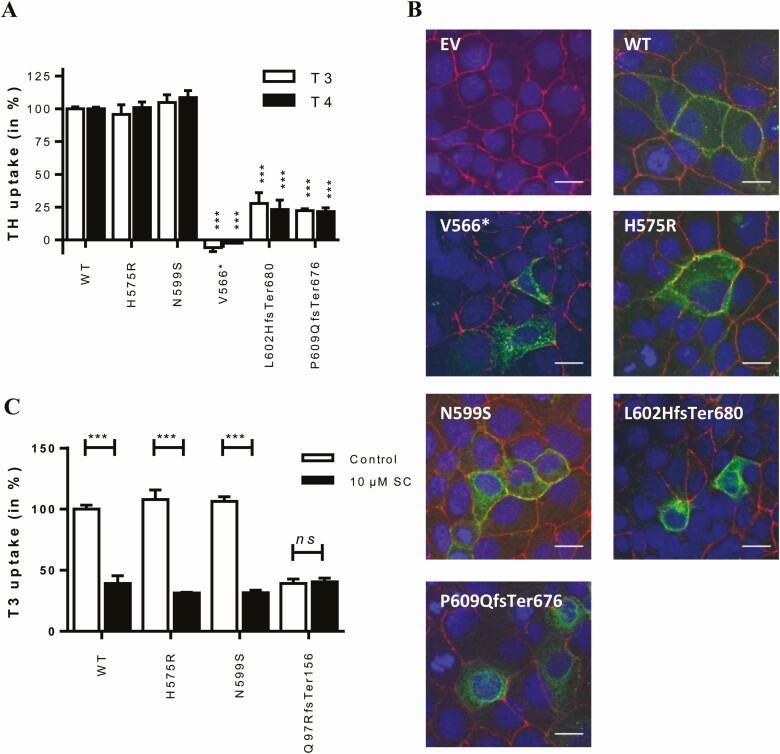

In line with the observations in COS-1 cells, the His575Arg and Asn599Ser variants did not affect T3 or T4 uptake in transiently transfected JEG-3 cells, whereas the Val566* variant was completely inactive. The Leu602HisfsTer680 and Pro609GlnfsTer676 variants showed T3 and T4 uptake levels amounting up to ~20–30% of WT MCT8 (Fig. 3A and Supplemental Fig. S3B) (24). Immunocytochemistry performed in JEG-3 cells showed that the His575Arg and Asn599Ser mutant proteins were predominantly localized at the cell membrane, as was the case for WT MCT8 (Fig. 3B). In contrast, all 3 frameshift variants showed a pronounced perinuclear staining and only little expression at the cell membrane.

Figure 3.

(A) T3 and T4 uptake in transiently transfected JEG-3 cells in presence of CRYM, after 30-minute incubation at 37 °C. Uptake levels are corrected for those observed in pcDNA3 empty vector (EV) transfected control cells and expressed relative to WT MCT8. Two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-tests were performed to assess for statistically significant differences between WT and indicated mutant MCT8 (P < 0.005, ***). Data were derived from at least 3 independent repetitions in duplo. T3 and T4 uptake by WT MCT8 was not different from 3′UTR-MCT8 (Supplemental Fig. S3B) (24). (B) Immunocytochemistry in JEG-3 cells transiently transfected with EV, WT, or indicated mutant MCT8 using antibodies against MCT8 (green) and the membrane marker ZO-1 (red). Cell nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). Images are presented as an overlay image. The scale bar represents 20 µm. (C) T3 uptake in control and patient-derived fibroblasts in the absence (-) or presence (+) of 10 µM silychristin (SC), a potent and specific inhibitor of MCT8-mediated thyroid hormone transport (26). T3 uptake by control and patient-derived cells in the presence and absence of SC was compared using a 2-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-tests (P < 0.001, ***; N = 2-5). The SC-induced reduction in T3 uptake did not differ between His575Arg and A599Ser vs control fibroblasts (1-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc tests, not indicated in the graph). Amino acids are indicated using their single-letter codes.

To further delineate if non-stop mRNA decay contributes to the reduced protein expression levels of the Leu602HisfsTer680 and Pro609GlnfsTer676 variants in our in vitro model, we explored whether mRNA expression levels of both variants differed from WT MCT8 in transiently transfected JEG3 cells. However, mRNA expression levels of both frameshift variants were not lower as compared with 3′ UTR WT MCT8 (Supplemental Fig. S4A) (24). Alternatively, we reasoned that the lower protein expression levels of these variants could be caused by enhanced protein degradation. Indeed, treatment with the proteasome inhibitor MG132 restored protein expression levels of both variants toward WT levels (Supplemental Fig. S4B) (24).

Next, we substituted the His575 and Asn599 by an Ala residue to confirm that both residues are not crucial for MCT8 function despite their strong evolutionary conservation (Fig. 1B). Indeed, both the His575Ala and Asn599Ala variants facilitated the uptake of T3 and T4 to be as efficient as WT MCT8 in COS-1 and JEG-3 cells (Supplemental Fig. S5A and B) (24).

To validate the apparent benign nature of the His575Arg and Asn599Ser variants in an independent ex vivo model, we also performed T3 uptake studies in patient-derived fibroblasts, which have previously been shown to be a suitable model to study the pathogenicity of MCT8 variants (16). Also, in patient-derived fibroblasts, T3 uptake did not differ between cells harboring the His575Arg or Asn599Ser variant and healthy controls (Fig. 3C). In contrast, T3 uptake was greatly diminished in fibroblasts derived from a previously reported patient with a Gln97ArgfsTer156 variant that results in premature truncation of the protein (Fig. 3C) (27). The MCT8-specific inhibitor silychristin (30) reduced T3 uptake by the His575Arg and Asn599Ser mutant fibroblasts and control fibroblasts to a similar extent, whereas no effect was observed in the Gln97ArgfsTer156 mutant fibroblasts (Fig. 3C). These results indicate that the His575Arg and Asn599Ser variants have no apparent functional consequences on thyroid hormone transport in this ex vivo model.

Exploring tolerable variation in the C-terminal tail of MCT8

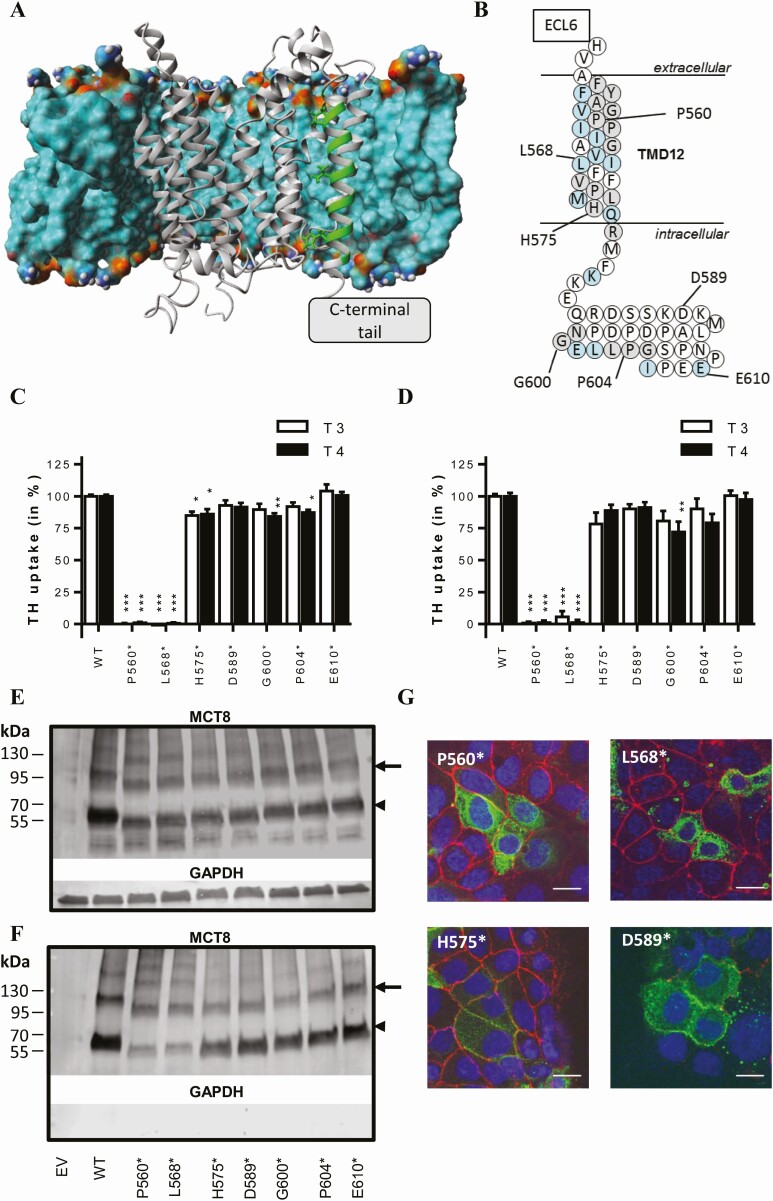

All identified variants were located in exon 6 which encodes TMD12 and the intracellular C-terminal tail but had different effects on MCT8 function. To further delineate the relevance of the C-terminal domain for MCT8 function, we generated a series of artificial premature stop variants that result in successive truncation of the C-terminal tail. Guided by our previously published MCT8 homology model (Fig. 4A), premature stop codons were introduced at positions Pro560 and Leu568 (both located within TMD12), His575 (located at the transition of TMD12 and C-terminal tail), and Gly600, Pro604, and Glu610 (all within the C-terminal tail) (Fig. 4B). All variants were predicted to escape nonsense-mediated decay. Upon overexpression in COS-1 or JEG-3 cells, the Pro560* and L568* variants diminished MCT8-mediated T3 and T4 uptake, whereas all other variants had no or very limited effects (Fig. 4C and D). Immunoblotting on total lysates from transiently transfected COS-1 cells showed that the protein expression levels of all premature stop variants were lower than WT MCT8, although the difference was not statistically significant for the His575* and Gly600* variants (Fig. 4E, Supplemental Fig. S6A) (24). The cell surface expression levels of the Pro560* and Leu568* variants were about 60% lower than WT MCT8 (Fig. 4F, Supplemental Fig. S6A) (24). The cell surface expression levels of the other variants were not significantly different from WT. In line with the observed cell surface expression levels in COS-1 cells, immunocytochemistry in JEG-3 cells showed pronounced perinuclear staining of the Pro560* and Leu568* variants, whereas all other tested premature stop variants were predominantly expressed at the cell membrane (Fig. 4G and Supplemental Fig. S6B) (24).

Figure 4.

(A) MCT8 homology model embedded in a lipid bilayer (displayed as the molecular surface, colored according to atom colors). For clarity, the lipid bilayer in front of the MCT8 protein is hidden. TMD12 is highlighted in green. The generation of the MCT8 homology model has been previously described (20). (B) Schematic representation of TMD12 and the intracellular C-terminal tail as shown in Fig. 1A, indicating the position of the truncating variants that were generated. T3 and T4 uptake in transiently transfected COS-1 (C) or JEG-3 (D) cells in presence of CRYM, after 30-minute incubation at 37 °C. Uptake levels are corrected for those observed in pcDNA3 empty vector (EV) transfected control cells and expressed relative to wild-type (WT) MCT8. Two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-tests were performed to assess for statistically significant differences between WT and indicated mutant MCT8 (P < 0.05, *; P < 0.01, **, P < 0.005 ***). Data were derived from at least 3 independent repetitions in duplicate. Representative immunoblot of total lysates (E) and biotinylated cell surface fraction (F) derived from COS-1 cells transiently transfected with WT or indicated mutant MCT8 (N = 3). The total lysate comprised a 5% input samples of the clarified lysate from which the presented surface fraction was derived. MCT8 monomers (arrowhead) and homodimers (arrow) are indicated. MCT8 (monomer) expression levels have been quantified in Supplemental Fig. S6A (24). (G) Immunocytochemistry in JEG-3 cells transiently transfected with indicated mutant MCT8 using antibodies against MCT8 (green) and the membrane marker ZO-1 (red). Cell nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). Images are presented as an overlay image. The scale bar represents 20µm. Immunocytochemistry in JEG-3 cells transfected with the Gly600*, Pro604*, and Glu610* variants is shown in Supplemental Fig. S6B (24). Amino acids are indicated using their single-letter codes.

Discussion

Here, we studied the clinical and molecular characteristics associated with a series of variants that affect the C-terminal domain of the MCT8 protein. We found that missense variants in 2 highly conserved residues in this region, p.His575Arg and p.Asn599Ser, did not affect MCT8 function in vitro and ex vivo, despite being predicted as potentially pathogenic. In line with these findings, we observed that successive C-terminal truncating variants were generally well-tolerated until reaching the transition between the intracellular C-terminal tail and TMD12. This suggests that the intracellular C-terminal tail has no major role in MCT8 function in vitro. By contrast, elongation of the C-terminal tail by frameshift variants reduced MCT8 function by interfering with proper cell membrane expression. Such variants were associated with a relatively less-severe clinical phenotype. Taken together, our studies provided important insight into the functional relevance and tolerable variation in the C-terminal tail of the MCT8 protein. This can help to predict the pathogenicity of novel variants identified in this region.

Functional evaluation of novel variants in MCT8 is critical to prove causality, the importance of which is illustrated by the p.His575Arg (proband P6) and p.Asn599Ser (proband P7) variants. Although the clinical and biochemical features in both individuals were deemed atypical for MCT8 deficiency, some frequently used in silico prediction tools classified both variants as potentially deleterious, leaving the possibility that both variants affect MCT8 function and cause a relatively mild phenotype. Indeed, few variants have been associated with atypical clinical presentations, including less-severe developmental delay and neurological manifestations, and/or serum thyroid function tests close to the normal range, as was the case for P6 and P7 (26, 31-33). To avoid misclassification of both variants and to not miss potentially mild manifestations of MCT8 deficiency, functional evaluation of both variants was deemed indispensable. However, neither variant affected MCT8 function in any of our cell-based models. The presence of the p.His575Arg variant in healthy male individuals supports the benign nature of this variant. In case of P7, segregation analysis was inconclusive, and alternative genetic diagnoses were not identified. Even though our models suggest that the p.Asn599Ser variant does not affect MCT8 function, cell-type specific effects of the p.Asn599Ser variant cannot be excluded. Further studies in patient-derived induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSc) may provide more robust conclusions on the pathogenicity of this variant.

In order to explore whether variants in the C-terminal tail are generally well-tolerated, we generated MCT8 constructs with sequential C-terminal truncations. We found that the Pro560* and Leu568* variants were fully inactivating, both of which truncate the MCT8 protein within TMD12. Such variants likely interfere with correct membrane integration and may thereby disturb protein stability and subcellular trafficking. In line with these observations, the p.Val566* variant, identified in proband P1 and P2, was completely inactive and showed decreased cell membrane expression levels. Accordingly, both boys exhibited classical clinical and biochemical features of MCT8 deficiency present in the majority of patients with MCT8 deficiency (2, 9, 31). In contrast, truncations beyond His575, marking the transition of TMD12 to the intracellular C-terminal tail, did not affect MCT8 function. Based on these findings, we postulate that truncating variants proximal to Leu568 likely result in complete loss of MCT8 function and cause severe clinical features of MCT8 deficiency, whereas truncations beyond His575 likely have minimal impact on MCT8 function, at least in our overexpression models. Interestingly, the most C-terminally located missense variant reported to be pathogenic also affects the Leu568 residue (p.Leu568Pro) (32), suggesting that missense variants beyond this point may also be tolerated. Although systematic mutagenesis studies of the C-terminal domain would be necessary to provide definitive prove, the apparent benign nature of the p.His575Arg and p.Asn599Ser variants would be in line with this hypothesis.

Although premature truncation of the MCT8 protein beyond His575 was well-tolerated in vitro, elongation of the MCT8 protein due to frameshift variants beyond this point (p.Leu602HisfsTer680 and p.Pro609GlnfsTer676) reduced MCT8 function. In line with their modest residual activity, both variants were associated with a relatively less-severe clinical phenotype. Affected individuals acquired several motor skills, including attaining head control, and P3 achieved independent standing and was able to babble. These findings were in line with a previous report describing a family with a c.1834delC frameshift variant that also elongates the MCT8 protein [p.(Pro609LeufsTer679)]. The affected males in this family also displayed relatively normal thyroid function tests and acquired more advanced motor skills (26). Based on a recent large-scale phenotyping study (31), only a small proportion of affected individuals exhibit relatively less-severe disease characteristics. Currently available data indicate that about 25% of patients attain head control, whereas the proportion of patients acquiring more advanced motor skills such as independent sitting and walking is well below 10% (31). Interestingly, individuals with less abnormal development also appear to exhibit less pronounced neurological features and might have less deranged serum thyroid function tests (eg, (31, 34, 35)). In line with these previous reports and in accordance with their relatively more advanced motor development, thyroid function tests were mildly attenuated in probands P3 through P5. Taken together, these observations suggest that frameshift mutations resulting in elongation of the C-terminal tail are associated with a relatively less-severe clinical phenotype.

Our molecular studies showed that both frameshift variants likely reduce protein stability and promote proteasomal degradation, which can, at least partly, be reverted by treatment with the proteasome inhibitor MG132. Moreover, both variants may interfere with subcellular trafficking, illustrated by the pronounced perinuclear localization of these mutant proteins in comparison to WT. We speculate that elongation of the C-terminal tail causes structural constraints with other intracellular domains, may establish novel unfavorable protein-protein interactions, and/or interferes directly with substrate passage.

The function of the C-terminus is unknown. Many membrane proteins require ancillary protein to govern proper cell membrane targeting, some of which recognize the C-terminal tail of their targets (36). Although other members of the MCT family require interactions with ancillary proteins for proper cell surface translocation (37), it is unknown if this also holds true for MCT8 (38). Should this be the case, such interactions are not likely to be established through its intracellular C-terminal tail as mutant proteins lacking this domain are fully functional and exhibited surface expression levels similar to WT MCT8. It should however be emphasized that a subset of our studies have been carried out in overexpressing mammalian cell lines. Factors required for optimal MCT8 expression and subcellular targeting may well be different in vivo and may, moreover, vary among tissues and different cell populations within the same tissue. Nevertheless, overexpression studies in COS-1 and JEG-3 cells have been shown to correspond well with the in vivo MCT8 transport capacity in physiologically relevant tissues. Also, MCT8 function in patient-derived fibroblasts is typically consistent with the findings in overexpression studies (eg, (10, 16, 27)).

Taken together, our analyses of C-terminal variants in MCT8 indicated that truncating variants proximal to Leu568 and frameshift variants that elongate the MCT8 protein are probably damaging, whereas truncating and missense variants distal to His575 are likely well-tolerated in our cell-based disease models. These findings provide clinical guidance in the assessment of the pathogenicity of variants within the C-terminal tail of the MCT8 protein and underscore the relevance of validating the functional impact of novel variants.

Acknowledgments

We thank Linda J. de Rooij, Ramona E.A. van Heerebeek, and Selmar Leeuwenburgh for the technical assistance and the Optical Imaging Center (Erasmus Medical Center Rotterdam) for technical support regarding the confocal imaging studies.

Financial Support: This work was supported by a grant from the Netherlands Organisation for Health Research and Development (project number 113303005) (to WEV) and from the Sherman Foundation (to WEV).

Glossary

Abbreviations

- BSA

bovine serum albumin

- CRYM

μ-crystallin

- EEG

electroencephalography

- EV

empty vector

- MCT8

monocarboxylate transporter 8

- MRI

magnetic resonance imaging

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

- rT3

reverse triiodothyronine

- T3

3,3′,5-triiodothyronine

- T4

thyroxine

- TMD

transmembrane domain

- TSH

thyrotropin (thyroid-stimulating hormone)

- WT

wild-type

Additional Information

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Data Availability

Restrictions apply to the availability of some or all data generated or analyzed during this study to preserve patient confidentiality or because they were used under license. The corresponding author will on request detail the restrictions and any conditions under which access to some data may be provided.

References

- 1. Bianco AC, Dumitrescu A, Gereben B, et al. Paradigms of dynamic control of thyroid hormone signaling. Endocr Rev. 2019;40(4):1000-1047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Groeneweg S, van Geest FS, Peeters RP, Heuer H, Visser WE. Thyroid Hormone Transporters. Endocr Rev. 2020;41(2):146-201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Friesema EC, Ganguly S, Abdalla A, Manning Fox JE, Halestrap AP, Visser TJ. Identification of monocarboxylate transporter 8 as a specific thyroid hormone transporter. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(41):40128-40135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Friesema EC, Kuiper GG, Jansen J, Visser TJ, Kester MH. Thyroid hormone transport by the human monocarboxylate transporter 8 and its rate-limiting role in intracellular metabolism. Mol Endocrinol. 2006;20(11):2761-2772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Friesema EC, Grueters A, Biebermann H, et al. Association between mutations in a thyroid hormone transporter and severe X-linked psychomotor retardation. Lancet. 2004;364(9443):1435-1437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Dumitrescu AM, Liao XH, Best TB, Brockmann K, Refetoff S. A novel syndrome combining thyroid and neurological abnormalities is associated with mutations in a monocarboxylate transporter gene. Am J Hum Genet. 2004;74(1):168-175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Vatine GD, Al-Ahmad A, Barriga BK, et al. Modeling psychomotor retardation using iPSCs from MCT8-deficient patients indicates a prominent role for the blood-brain barrier. Cell Stem Cell. 2017;20(6):831-843.e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Heuer H, Visser TJ. The pathophysiological consequences of thyroid hormone transporter deficiencies: Insights from mouse models. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1830(7):3974-3978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Groeneweg S, Visser WE, Visser TJ. Disorder of thyroid hormone transport into the tissues. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2017;31(2):241-253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Masnada S, Groenweg S, Saletti V, et al. Novel mutations in SLC16A2 associated with a less severe phenotype of MCT8 deficiency. Metab Brain Dis. 2019;34(6):1565-1575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Fu J, Korwutthikulrangsri M, Ramos-Platt L, et al. Sorting variants of unknown significance identified by whole exome sequencing: genetic and laboratory investigations of two novel MCT8 variants. Thyroid. 2020;30(3):463-465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Choi Y, Chan AP. PROVEAN web server: a tool to predict the functional effect of amino acid substitutions and indels. Bioinformatics. 2015;31(16):2745-2747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Rentzsch P, Witten D, Cooper GM, Shendure J, Kircher M. CADD: predicting the deleteriousness of variants throughout the human genome. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47(D1):D886-D894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Adzhubei IA, Schmidt S, Peshkin L, et al. A method and server for predicting damaging missense mutations. Nat Methods. 2010;7(4):248-249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Vaser R, Adusumalli S, Leng SN, Sikic M, Ng PC. SIFT missense predictions for genomes. Nat Protoc. 2016;11(1):1-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Visser WE, Jansen J, Friesema EC, et al. Novel pathogenic mechanism suggested by ex vivo analysis of MCT8 (SLC16A2) mutations. Hum Mutat. 2009;30(1):29-38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Capri Y, Friesema EC, Kersseboom S, et al. Relevance of different cellular models in determining the effects of mutations on SLC16A2/MCT8 thyroid hormone transporter function and genotype-phenotype correlation. Hum Mutat. 2013;34(7):1018-1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kinne A, Roth S, Biebermann H, Köhrle J, Grüters A, Schweizer U. Surface translocation and tri-iodothyronine uptake of mutant MCT8 proteins are cell type-dependent. J Mol Endocrinol. 2009;43(6):263-271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kinne A, Kleinau G, Hoefig CS, et al. Essential molecular determinants for thyroid hormone transport and first structural implications for monocarboxylate transporter 8. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(36):28054-28063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Groeneweg S, Lima de Souza EC, Meima ME, Peeters RP, Visser WE, Visser TJ. Outward-open model of thyroid hormone transporter monocarboxylate transporter 8 provides novel structural and functional insights. Endocrinology. 2017;158(10):3292-3306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Protze J, Braun D, Hinz KM, Bayer-Kusch D, Schweizer U, Krause G. Membrane-traversing mechanism of thyroid hormone transport by monocarboxylate transporter 8. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2017;74(12):2299-2318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Coban-Akdemir Z, White JJ, Song X, et al. ; Baylor-Hopkins Center for Mendelian Genomics . Identifying genes whose mutant transcripts cause dominant disease traits by potential gain-of-function alleles. Am J Hum Genet. 2018;103(2):171-187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Mol JA, Visser TJ. Synthesis and some properties of sulfate esters and sulfamates of iodothyronines. Endocrinology. 1985;117(1):1-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. van Geest FS, Meima ME, Stuurman KE, et al. Clinical and functional consequences of C-terminal variants in MCT8: a case series. Erasmus University Rotterdam RePub repository. Deposited May 7, 2020. https://repub.eur.nl/pub/126612/. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25. Friesema EC, Jansen J, Jachtenberg JW, Visser WE, Kester MH, Visser TJ. Effective cellular uptake and efflux of thyroid hormone by human monocarboxylate transporter 10. Mol Endocrinol. 2008;22(6):1357-1369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Maranduba CM, Friesema EC, Kok F, et al. Decreased cellular uptake and metabolism in Allan-Herndon-Dudley syndrome (AHDS) due to a novel mutation in the MCT8 thyroid hormone transporter. J Med Genet. 2006;43(5):457-460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Groeneweg S, van den Berge A, Meima ME, Peeters RP, Visser TJ, Visser WE. Effects of chemical chaperones on thyroid hormone transport by mct8 mutants in patient-derived fibroblasts. Endocrinology. 2018;159(3):1290-1302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Groeneweg S, Friesema EC, Kersseboom S, et al. The role of Arg445 and Asp498 in the human thyroid hormone transporter MCT8. Endocrinology. 2014;155(2):618-626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kersseboom S, Horn S, Visser WE, et al. In vitro and mouse studies supporting therapeutic utility of triiodothyroacetic acid in MCT8 deficiency. Mol Endocrinol. 2014;28(12):1961-1970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Johannes J, Jayarama-Naidu R, Meyer F, et al. Silychristin, a flavonolignan derived from the milk thistle, is a potent inhibitor of the thyroid hormone transporter MCT8. Endocrinology. 2016;157(4):1694-1701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Groeneweg S, van Geest FS, Abacı A, et al. Disease characteristics of MCT8 deficiency: an international, retrospective, multicentre cohort study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2020;8(7):594-605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Schwartz CE, May MM, Carpenter NJ, et al. Allan-Herndon-Dudley syndrome and the monocarboxylate transporter 8 (MCT8) gene. Am J Hum Genet. 2005;77(1):41-53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Boccone L, Dessì V, Meloni A, Loudianos G. Allan-Herndon-Dudley syndrome (AHDS) in two consecutive generations caused by a missense MCT8 gene mutation. Phenotypic variability with the presence of normal serum T3 levels. Eur J Med Genet. 2013;56(4):207-210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Novara F, Groeneweg S, Freri E, et al. Clinical and molecular characteristics of SLC16A2 (MCT8) mutations in three families with the Allan-Herndon-Dudley syndrome. Hum Mutat. 2017;38(3):260-264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Remerand G, Boespflug-Tanguy O, Tonduti D, et al. ; RMLX/AHDS Study Group . Expanding the phenotypic spectrum of Allan-Herndon-Dudley syndrome in patients with SLC16A2 mutations. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2019;61(12):1439-1447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Zhang M, Wang W. Organization of signaling complexes by PDZ-domain scaffold proteins. Acc Chem Res. 2003;36(7):530-538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kirk P, Wilson MC, Heddle C, Brown MH, Barclay AN, Halestrap AP. CD147 is tightly associated with lactate transporters MCT1 and MCT4 and facilitates their cell surface expression. EMBO J. 2000;19(15):3896-3904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Visser WE, Philp NJ, van Dijk TB, et al. Evidence for a homodimeric structure of human monocarboxylate transporter 8. Endocrinology. 2009;150(11):5163-5170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Restrictions apply to the availability of some or all data generated or analyzed during this study to preserve patient confidentiality or because they were used under license. The corresponding author will on request detail the restrictions and any conditions under which access to some data may be provided.