Abstract

Context

Pituitary blastoma is a rare, dysontogenetic hypophyseal tumor of infancy first described in 2008, strongly suggestive of DICER1 syndrome.

Objective

This work aims to describe genetic alterations, clinical courses, outcomes, and complications in all known pituitary blastoma cases.

Design and Setting

A multi-institutional case series is presented from tertiary pediatric oncology centers.

Patients

Patients included children with pituitary blastoma.

Interventions

Genetic testing, surgery, oncologic therapy, endocrine support are reported.

Outcome Measures

Outcome measures included survival, long-term morbidities, and germline and tumor DICER1 genotypes.

Results

Seventeen pituitary blastoma cases were studied (10 girls and 7 boys); median age at diagnosis was 11 months (range, 2-24 months). Cushing syndrome was the most frequent presentation (n = 10). Cushingoid stigmata were absent in 7 children (2 with increased adrenocorticotropin [ACTH]; 5 with normal/unmeasured ACTH). Ophthalmoplegia and increased intracranial pressure were also observed. Surgical procedures included gross/near-total resection (n = 7), subtotal resection (n = 9), and biopsy (n = 1). Six children received adjuvant therapy. At a median follow-up of 6.7 years, 9 patients were alive; 8 patients died of the following causes: early medical/surgical complications (n = 3), sepsis (n = 1), catheter-related complication (n = 1), aneurysmal bleeding (n = 1), second brain tumor (n = 1), and progression (n = 1). Surgery was the only intervention for 5 of 9 survivors. Extent of resection, but neither Ki67 labeling index nor adjuvant therapy, was significantly associated with survival. Chronic complications included neuroendocrine (n = 8), visual (n = 4), and neurodevelopmental (n = 3) deficits. Sixteen pituitary blastomas were attributed to DICER1 abnormalities.

Conclusions

Pituitary blastoma is a locally destructive tumor associated with high mortality. Surgical resection alone provides long-term disease control for some patients. Quality survival is possible with long-term neuroendocrine management.

Keywords: Pituitary blastoma, endocrinopathy, DICER1, microRNA, infants, morbidities

Pituitary blastoma is a distinctive anterior hypophyseal tumor of infants described first in 2008 (1). Although the clinical, pathological, and molecular features of 14 cases have been described (1-4), there are no comprehensive data on long-term outcomes. Pituitary blastoma presents in infants younger than 24 months, most frequently with Cushing syndrome and elevated adrenocorticotropin (ACTH) and occasionally with ophthalmoplegia, signs of increased intracranial pressure, diabetes insipidus, and thyrotropin deficit. An often large solid or cystic/solid mass arises from the sella with extension into the hypothalamus and may encompass the optic chiasm and/or cavernous sinuses. Pathologically, the tumors exhibit arrested pituitary development and uncontrolled proliferation and are composed of Rathke epithelium, folliculostellate cells, small primitive cells, and secretory cells with ACTH or, less often, growth hormone (GH) immunoexpression (2, 4).

Pituitary blastoma is highly indicative of DICER1 syndrome, as all reported completely studied cases can be tied to DICER1 abnormalities (3-5). DICER1 syndrome is caused by alterations in the microRNA processing gene DICER1, typically from inherited heterozygous pathogenic alterations, including single-nucleotide variations and large or small insertions or deletions; de novo germline alterations and mosaicism also occur (5, 6). DICER1 is critical for the biogenesis of microRNAs, which modulate gene expression by inhibition of messenger RNA. Virtually all DICER1 syndrome tumors harbor a characteristic somatic change in the second DICER1 allele—a so-called RNase IIIb “hotspot mutation,” affecting 1 of 5 critical ion-binding sites in the cleavage domain of the DICER1 protein (5). In a minority of pituitary blastomas, the somatic event is not the usual hotspot mutation but instead a loss of the wild-type allele (4).

Other phenotypes of DICER1 syndrome that may present with symptoms of possible endocrinologic disease include ovarian Sertoli-Leydig cell tumor, sarcoma of the uterine cervix with vaginal bleeding, and several thyroid proliferations: multinodular goiter, familial multinodular goiter, and differentiated thyroid cancer (7-11). The latter is usually a moderate or well-differentiated tumor with excellent outcomes, but a potentially lethal poorly differentiated DICER1-related subtype has recently emerged in adolescents (12). In addition to thyroid and gynecologic conditions, DICER1 syndrome includes approximately 25 conditions in other organ systems. Most phenotypes are proliferative mesenchymal masses, both malignant and benign (5), and several affect very young children, such as pituitary blastoma, pleuropulmonary blastoma, cystic nephroma, and certain other very rare intracranial neoplasms (13, 14). Penetrance in DICER1 syndrome is generally low: less than 5% to 10% for the more frequent phenotypes and less than 1% for the rare phenotypes such as pituitary blastoma (15). However, multinodular goiter, which has no specificity for DICER1 syndrome, is estimated to affect 75% of female and 17% of male carriers of DICER1 mutations (9). Also, occult, asymptomatic lung cysts detected by computerized tomography have been demonstrated in 25% to 30% of mutation carriers (15).

Here, we report the long-term outcomes of all known, well-investigated cases of pituitary blastoma, including 3 cases not previously published in detail (16-18). A recent brief report of a possible 18th case in a 19-year-old female is not included (19). Patient presentation, oncologic treatments, updated clinical outcomes, genetic profiles, and morbidities including neuroendocrine complications are detailed.

Materials and Methods

Design and study cohort

This observational study comprised a multi-institutional cohort of 17 patients with pituitary blastoma: updating 14 previously described cases (1-4, 20-28) and fully characterizing 3 additional cases (16-18). Cases were identified by ongoing literature review, inquiries to leading pituitary experts, and case referrals. Cases were included based on clinical findings, pathological diagnosis, and DICER1 molecular findings or on prototypical DICER1 syndrome phenotypes in the child. Retrospective chart review was performed to collect demographic, clinical, biochemical, pathological, radiographic, and treatment characteristics. The chart review also updated patient outcomes including tumor progression, patient survival, and in survivors, long-term health deficits focusing on endocrinologic, visual, and neurodevelopmental morbidities. Molecular and immunohistochemical data from primary institutions were recorded. Molecular studies were performed on one case (case 17) not previously studied. This study was approved by the respective institutional review boards of participating institutions, with informed consent obtained in accordance with institutional guidelines.

DICER1 genotyping

DICER1 genotyping has been previously reported for 14 cases (3, 4, 17, 18). Sequencing of DICER1 was performed on case 17 by using the custom-design Access Array (Fluidigm), and an exon-trapping assay was used to validate the functional consequence of a newly identified splice-site variant (4, 29, 30). In 2 cases, no molecular information was available, but 1 of the cases showed strong clinical evidence of DICER1 syndrome (4).

Survival analyses

The date of diagnosis was defined as the date of first biopsy (Bx) or resection. Overall survival (OS) was defined as the duration between the date of diagnosis and date of either death from any cause or last follow-up. Event-free survival (EFS) was defined as the duration between the date of diagnosis and date of progression, relapse, death from any cause, or last follow-up. Comparison of OS and EFS by clinical factors (extent of resection, use of adjuvant therapy, year of diagnosis) was performed by log-rank test. Data collection was closed April 30, 2020. Statistical analyses were performed using R v3.6.0 (www.R-project.org).

Results

Recently investigated cases of pituitary blastoma

Since the reports by Sahakitrungruang et al (1 case) and de Kock et al (13 cases), 3 additional cases of pituitary blastoma have been thoroughly investigated (1-4, 16-18, 20-28). In 2010, Salunke and colleagues reported a 2-month-old girl with cushingoid stigmata since birth, ophthalmoplegia, hemiparesis, and a pituitary tumor diagnosed as a “congenital immature teratoma” (case 17; Table 1) (30, 31); the pathology on review was consistent with pituitary blastoma (16). We subsequently studied DNA from tumor and germline DNA from the parents and 2 siblings. The patient and siblings inherited a splice-site DICER1 variant from the father; splicing studies revealed that the variant creates an out-of-frame nucleotide sequence predicted to result in a truncated protein, which may be subject to nonsense-mediated decay (30). Despite poor-quality tumor DNA, an RNase IIIb hotspot mutation was weakly, but reproducibly, detected. In a 2015 abstract, Gresh et al reported pituitary blastoma in a 22-month-old boy with headaches and vomiting (17). A DICER1 hotspot mutation was found in the tumor tissue, with loss of heterozygosity suggested; a germline pathogenic variant could not be identified in DNA extracted from peripheral blood lymphocytes (case 16; see Table 1) (30, 31). In a 2017 abstract, Kalinin and colleagues reported pituitary blastoma in a 10-month-old boy with Cushing disease and a past medical history of cystic lung dysplasia; the primary investigators documented somatic hotspot and inherited germline DICER1 pathogenic variants (case 15; see Table 1) (18, 30, 31).

Table 1.

Clinical profiles, treatments, and outcomes for patients with pituitary blastoma

| Patient No. (y of Dx) | Sex | Age at presentation/diagnosis, mo | Tumor size, cm | Ki-67/MIB-1 | Treatment course | Progression | Latest disease status | Duration of FU | First publication |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (2000) | F | 13/13 | 3.5 | 1.5%-39% | STR | No | Died of early complication | 1.5 mo | (1) |

| 2 (2006) | F | 22/24 | 4 | 1.6% | STR > Gamma knife (45 Gy) | No | Alive with NED | 14 y | (27) |

| 3 (2010) | M | 9/9 | 3 × 2.3 × 1.6 | 15%-50% | STR > chemotherapy (baby POG) | No | Alive with stable lesion | 10 y | (28)a |

| 4 (2006) | F | 18/24 | 2.4 × 3.1 × 2.4 | Not reported | GTR | No | Alive with NED | 13.6 y | (20) |

| 5 (2009) | F | 13/13 | 2.1 × 1.8 | 60% | STR > chemotherapy (TMZ) > PD | Local; 20 mo from diagnosis (focal RT 54 Gy > TMZ > BEV, CPT-11 > IFOS, CARBO, VP16) | Died of aneurysmal bleeding | 5.5 y | (2) |

| 6 (2005) | M | 5/7 | NA | Not reported | Bx | No | Died of early complication | 1.3 mo | (4) |

| 7 (1980) | M | 6/11 | 3 | Not reported | STR > GTR | No | Died of second brain tumor (?pineoblastoma) | 2.3 y | (23) |

| 8 (1977) | M | 8/8 | 12 × 8 × 5 | Low | Bx > STR | No | Died of early complication | 1 d | (24) |

| 9 (1996) | F | 5/7 | 3 × 2 × 2 | Not reported | GTR | No | Alive with NED | 23.5y | (25) |

| 10 (1994) | F | ?/12 | 6 × 4 × 4 | Not reported | STR | Local; 18 mo from diagnosis | Died of progression | 1.5 y | (26) |

| 11 (2012) | F | 7/7 | NA | Markedly proliferative | STR > STR | No | Alive with stable lesion | 8.2 y | (4) |

| 12 (2012) | M | 8/13 | NA | Markedly proliferative | Bx > chemotherapy (TMZ) > NTR > chemotherapy (TMZ) | No | Alive with NED | 7.8 y | (4) |

| 13 (2000) | F | 9/9 | 1.7 × 1.5 | Moderate | GTR > chemotherapy (ANZCCSG baby brain protocol without ASCT) | No | Alive with NED | 19 y | (4) |

| 14 (pub. 2014) | F | 11/12 | 2.9 × 2 × 2.8 | Up to 20% | STR > chemotherapy (CPM, VCR, MTX, CARBO, VP16) | No | Died of catheter-related complication | 4 mo | (3) |

| 15 (2012) | M | 8/10 | 2.6 × 2.4 × 2.4 | 19% | GTR | No | Alive with NED | 8.4 y | (18) |

| 16 (2014) | M | 16/22 | 2 | 10%-15% | GTR | No | Alive with NED | 6.7 y | (17) |

| 17 (2009) | F | 1/2 | 5 × 3 × 2 | 2%-3% (focally higher) | STR | No | Died of sepsis | 1 mo | (16) |

Abbreviations: ANZCCSG, Australian and New Zealand Children’s Cancer Study Group; ASCT, autologous stem cell transplant; BEV, bevacizumab; Bx, biopsy; CARBO, carboplatin; CPM, cyclophosphamide; CPT-11, irinotecan; Dx, diagnosis; F, female; FU, follow-up; GTR, gross total resection; IFOS, ifosfamide; M, male; MTX, methotrexate; NA, not available; NED, no evidence of disease; NTR, near total resection; POG, Pediatric Oncology Group; pub., published; RT, radiotherapy; STR, subtotal resection; TMZ, temozolomide; VCR, vincristine; VP16, etoposide.

Demographic and presenting features of the entire cohort

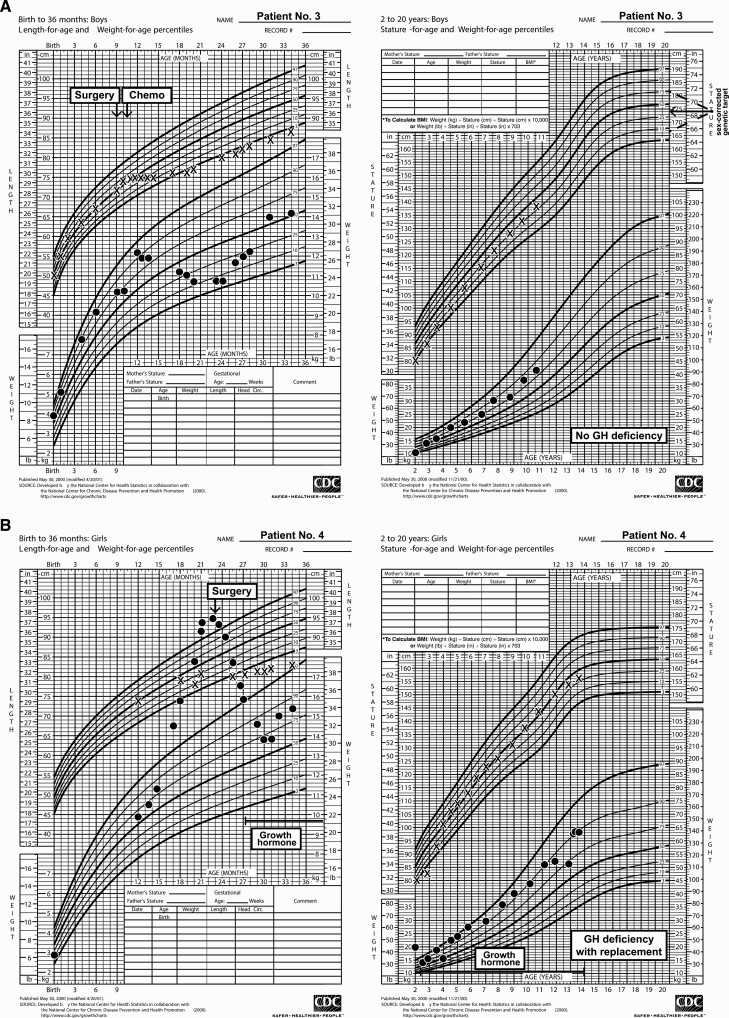

Seventeen patients were reported between 1979 and 2017; 10 were female (see Table 1). First symptoms were noted at a median age of 8.5 months (range, 0-22 months); median age of diagnosis was 11 months (range, 2-24 months). Presenting symptoms included Cushing syndrome (n = 10), cranial nerve palsies including ophthalmoplegia (n = 7), reduced visual acuity (n = 4), developmental delay (n = 4), and symptoms of increased intracranial pressure (n = 3). Increased ACTH (n = 9) or random serum cortisol (n = 1) was documented at diagnosis in the 10 patients presenting with Cushing syndrome (Table 2). Fig. 1 presents growth charts for 3 cases, including a classic pattern for Cushing syndrome as the weight plot rises to cross the falling length plot (Fig. 1B). Preoperatively, among the 7 children without signs of Cushing syndrome at diagnosis (see Table 2), assays revealed 1 child with normal ACTH and 2 with increased ACTH (1 coupled with unsuppressed morning cortisol and 1 with a normal random serum cortisol). ACTH or serum/urine cortisol measurement was not performed in 4 patients. These patients presented with ophthalmoplegia (n = 4) or symptoms of increased intracranial pressure (n = 3). Before surgery, secondary hypothyroidism was noted in 3 patients and diabetes insipidus in 2. Immunohistochemical staining for ACTH was positive in 16 of 17 tumors; the patient whose tumor was negative for ACTH presented with signs of increased intracranial pressure, and no endocrinologic assessment was conducted preoperatively. Immunohistochemistry for GH was positive in 10 of the 14 cases tested, but serum insulin-like growth factor-1 (n = 3) and spot GH (n = 1) did not suggest GH excess in the 4 patients evaluated (see Table 2). At presentation, no child exhibited excessive linear growth, although in the presence of Cushing disease clinical change due to excess GH would have been hard to discern. In contrast to the ACTH and GH findings, tumor immunostains for other pituitary hormones were rarely positive: luteinizing hormone, 1 of 10; follicle-stimulating hormone, 1 of 11; thyrotropin, 0 of 10; and prolactin, 0 of 10. Radiographically, an enhancing sellar mass, with or without intratumoral cysts and cavernous sinus involvement, was typically seen on magnetic resonance imaging, with a median greatest diameter of 3 cm (range, 1.7-12 cm) (31); enhancement was not seen in one patient. None of the patients showed metastasis at diagnosis or during follow-up.

Figure 1.

Growth charts depicting trends in body weight and length/height in pituitary blastoma patients having A, normal pituitary function; and B, panhypopituitarism with and C, without growth hormone replacement prediagnosis and postdiagnosis, including long-term follow-up. Chemo, chemotherapy; GH, growth hormone; No., number.

Table 2.

Endocrine status at diagnosis and follow-up for 17 pituitary blastoma cases

| Patient No. | Age at Dx, mo | Age at last FU | Tumor ACTH IHC | Tumor GH IHC | Clinically Cushingoid at Dx | Adrenal axis | Thyroid axis | Somatotropic/growth axis | Gonadal axis | Diabetes insipidus | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dx | FU | Dx | FU | Dx | FU | Dx | FU | Dx | FU | ||||||

| Patients alive at last FU | |||||||||||||||

| 2 | 24 | 16 y | + | + | No | ACTH↑ Random serum cortisol NL |

ACTH↓ | NL | TSH↓ | Decreased linear growth < 10% | GH↓ | NL | ↓ | No | Yes |

| 3 | 9 | 10.8 y | + | – | No (postoperatively, Cushing features+) | ACTH↑ Failed DST |

NL | TSH, fT4, TT3↓ | NL | NL | NL | NL | NL | No | No |

| 4 | 24 | 15.6 y | + | – | Yes | ACTH↑ Failed DST |

ACTH↓ | Unk | TSH↓ | Unk | GH↓ | NL | ↓ | No | Transient postoperatively |

| 9 | 7 | 24.1 y | + | + | Yes | ACTH↑ | ACTH↓ | NL | TSH↓ | NL | NL | Unk | ↓ | No | No |

| 11 | 7 | 8.8 y | + | + | No | Unk | ACTH↓ | Unk | TSH↓ | Unk | GH↓ | Unk | NL | Unk | Yes |

| 12 | 13 | 8.9 y | + | + | Yes | ACTH↑ Failed DST |

NL | Unk | NL | Unk | Decreased linear growth but unk for GHD | Unk | NL | No | No |

| 13 | 9 | 19.8 y | – | – | No | Unk | ACTH↓ | Unk | TSH↓ | Unk | GH↓ | Unk | ↓ | No | Yes |

| 15 | 10 | 9.2 y | + | Not reported | Yes | ACTH↑ Random serum cortisol↑ |

ACTH↓ | Unk | TSH↓ | Unk | GH↓ | Unk | NL | No | No |

| 16 | 22 | 8.5 y | + | Not reported | No | ACTH NL | ACTH↓ | NL | TSH↓ | NL | GH↓ | Unk | NL | No | No |

| Patients died | |||||||||||||||

| 1 | 13 | 14.5 mo | + | + | Yes | ACTH↑ Failed DST |

– | TSH↓ | – | NL | – | NL | – | Yes | – |

| 5 | 13 | 6.9 y | + | + | No | Unk | NL | NL | NL | NL | NL | Unk | NL | No | No |

| 6 | 7 | 8.3 mo | + | + | No | Unk | – | NL | – | NL | – | NL | – | No | – |

| 7 | 11 | 3.2 y | + | - | Yes | ACTH↑ Urine cortisol↑ |

ACTH↓ | NL | TSH↓ | NL | Unk | Unk | Unk | No | Yes |

| 8 | 8 | 8 mo | + | + | Yes | ACTH↑ Failed DST |

– | TSH↓ | – | Unk | – | NL | – | No | – |

| 10 | 12 | 2.5 y | + | + | Yes | Random serum cortisol↑ | – | Unk | – | Decreased linear growth < 10% | – | Unk | – | Yes | – |

| 14 | 12 | 16 mo | + | Not reported | Yes | ACTH↑ Failed DST |

– | NL | – | NL | – | Unk | – | No | – |

| 17 | 2 | 3 mo | + | + | Yes | ACTH↑ Failed DST |

– | NL | – | NL | – | NL | – | No | Transient postoperatively |

Abbreviations: ACTH, adrenocorticotropin; DST, dexamethasone suppression test; Dx, diagnosis; fT4, free thyroxine; FU, follow-up; GH, growth hormone; GHD, growth hormone deficiency; IHC, immunohistochemistry; NL, normal; TSH, thyrotropin; TT3, total triiodothyronine; Unk, unknown; ↑measured and increased; ↓ measured and decreased.

Treatments and outcomes

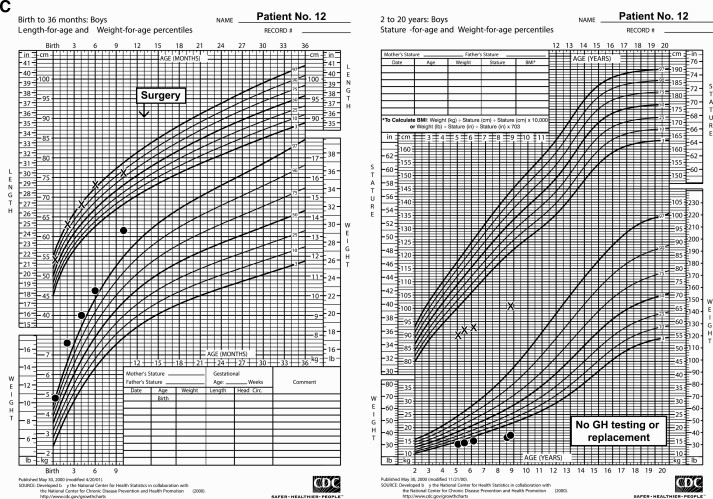

Patient treatments and outcomes are summarized in Table 1 and Fig. 2. Surgical resection was attempted at diagnosis in all patients, including 4 patients who had staged resection, resulting in gross or near-total resection (GTR/NTR, n = 7), subtotal resection (STR, n = 9), and Bx (n = 1). Five patients received chemotherapy after surgery (see Table 1). Two patients received focal radiation: Gamma-knife (Elekta) radiotherapy 17 months after diagnosis for persistent residual disease (case 2), and conformal radiation 24 months after the diagnosis of disease progression (case 5; see Table 1).

Figure 2.

Extent of resection, adjuvant therapy, and outcomes for the cohort. GTR, gross total resection; NED, no evidence of disease; NTR, near total resection; RT, radiation therapy; STR, subtotal resection.

Four patients died within 6 weeks of surgery of medical/surgical complications (n = 3) or sepsis (n = 1); 4 died later in their courses of a second brain tumor (suspected pineoblastoma, n = 1), central venous catheter–related complication (n = 1), aneurysmal bleeding (n = 1), or progression (n = 1) (see Fig. 2). The patient who died of aneurysmal bleeding (case 5) had also had local progression that was treated with conformal radiation (54 Gy, at age 37 months) and 3 lines of chemotherapy including bevacizumab (see Table 1). The patient died 6 months from the last documented progression; an autopsy was not performed and tumor status at death is unknown.

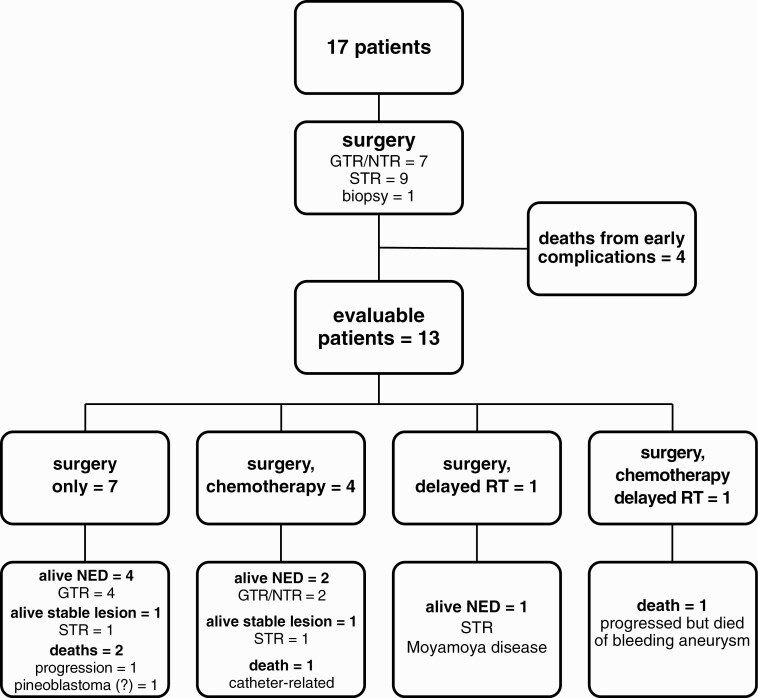

At a median follow-up of 6.7 years (range, 1 day to 23.5 years), 9 patients are alive without evidence of disease (n = 7) or stable residual lesion radiographically (n = 2, duration of follow-up: 8.2 and 10 years) (see Table 1, Fig. 2) (31). Of the 7 surgery-only patients who survived beyond 6 weeks, 5 were long-term survivors; their extents of surgery were, respectively, GTR (n = 4) and STR (n = 1) (see Fig. 2). The 5-year EFS and OS were 53 ± 12% and 59 ± 12%, respectively (Fig. 3). Extent of resection (GTR/NTR vs STR/Bx; EFS P = .018, OS P = .023) and year of diagnosis (before 1996 vs 1996 or later; EFS P = .048, OS P = .029), were significantly associated with patient survival. Neither use of adjuvant therapy nor tumor Ki67 labeling index was significantly associated with survival. Although not statistically significantly associated with better outcomes across all cases, chemotherapy in case 3 was temporally associated with an improvement in recrudescent hypercortisolemia 3 months following surgery (discussed later).

Figure 3.

Event-free survival (EFS) and A and B, overall survival (OS) in the entire cohort, C and D, by extent of surgery, and E and F, period of diagnosis. Bx, biopsy; GTR, gross total resection; NTR, near total resection; STR, subtotal resection.

Endocrinologic, visual, and neurodevelopmental morbidities

Chronic health deficits were noted in the 8 of the 9 survivors. Hypopituitarism was frequent (see Table 2). Deficiencies were noted in ACTH (n = 7), thyrotropin (n = 7), gonadotropin (n = 4), antidiuretic hormone (n = 3), and GH (n = 6). GH replacement was administered to all patients with documented GH deficiency (initiated at age 2.3-13.1 years, and 0.3-7.3 years from oncological diagnosis) (see Fig. 1B). One survivor (case 12) aged 8.9 years was not evaluated for GH status and was 101 cm tall, 5.6 SDs below the mean for age (Fig. 1C); this child received neither GH nor other hormonal supplementation. Persistent hypercortisolism was not observed among long-term survivors. In case 3, cortisol levels progressively diminished in the first 3 months following STR of tumor. At 4 months, hypercortisolemia returned and the child started to become cushingoid. Chemotherapy was commenced, with cortisol measurements normalizing over the next 12 to 18 months. At 10 years from diagnosis, a small, stable residual lesion at the right cavernous sinus remained, and the child was thriving without endocrinopathy (Fig. 1A) (31). Four patients had visual complications: severe vision impairments (n = 2), extraocular movement palsy (n = 1), and bilateral optic atrophy as well as extraocular movement palsy (n = 1). Neurodevelopmentally, 6 patients were reported to be progressing satisfactorily in academic studies, whereas 2 patients had cognitive delay. The patient who received Gamma-knife therapy had moyamoya disease that required revascularization surgery 9.3 years after radiation.

Genotyping and DICER1 syndrome

Genotyping results for the patients and for the pituitary blastomas and additional DICER1 syndrome conditions in the patients are available in an online repository (30). Germline DICER1 variants were detected in 12 of 13 patients tested. DICER1 alterations were identified in 13 of 14 tumor samples tested (hotspot mutations, n = 11; loss of heterozygosity, n = 2). In no case did we have proof that both the hotspot and nonhotspot DICER1 abnormalities detected in tumor DNA were somatic in origin. One child for whom DNA was unavailable had strong clinical evidence of DICER1 involvement (bilateral renal and pulmonary cysts) (21-23). For one child, the clinical history was unremarkable and DNA was unavailable. Overall, molecular and/or clinical evidence implicates DICER1 in 16 of the 17 pituitary blastoma cases.

In 6 of 8 patients whose families underwent testing, the predisposing DICER1 variant in the index patient was found to be inherited. Members of 5 of the 6 families had DICER1-related conditions (30). Among pituitary blastoma survivors (median age at last follow-up 10.8 years; range, 8.5-24.1 years), one patient was subsequently diagnosed with an additional DICER1 syndrome–related condition (case 11, nasal chondromesenchymal hamartoma). Among the nonsurvivors, one child developed a second DICER1 condition: a primitive neuroectodermal tumor in the pineal region considered likely pineoblastoma, which was considered the cause of death.

Discussion

Pituitary blastoma is a rare intracranial tumor typified by onset younger than 24 months, Cushing disease, and a strong association with abnormalities of DICER1. This study summarizes 17 cases and describes long-term outcomes and morbidities. Follow-up clinical data were available for all surviving patients. Biochemical evidence of hypercortisolism was present in the 10 infants who presented with cushingoid stigmata; 16 of 17 tumors stained for ACTH. Sixteen of the 17 cases can be tied to abnormalities of the DICER1 gene. Nine of 17 patients survived (median survival, 6.7 years; median age at last follow-up, 10.8 years) with hormonal sequalae ranging from none to panhypopituitarism and neurocognitive function ranging from fully functional to impaired, and some survivors were visually impaired. GH replacement therapy in several children was not associated with disease recurrence or development of other neoplasms, in keeping with recommendations for judicious use of GH replacement in cancer survivors (32, 33).

Six complication-related deaths in the cohort compromise the study of long-term outcomes and potential prognostic factors (see Table 1; Fig. 2). Three early deaths occurred in infants with Cushing disease, a potentially life-threatening endocrine condition (34), and highlight the medical/surgical challenge caring for a small infant with an intracranial mass and a serious endocrine disturbance. Notwithstanding limited case numbers, our analyses (see Fig. 3) suggest GTRs/NTRs are beneficial and that more recently treated cases are associated with better survival, which seems reasonable given advances in imaging, neurosurgery, intensive care, and endocrinology. Five of 7 children whose only intervention was surgery were long-term survivors. Adjuvant therapy was not significantly associated with better survival. This contrasts with high-grade pediatric brain tumors, which are likely to recur unless adjuvant therapies are used.

Vascular complications (aneurysm and moyamoya disease) occurred in the 2 children (see Table 1; Fig. 2) who received intensive focal radiation therapy, echoing risk factors for postradiation vasculopathy identified in young children treated for craniopharyngioma or optic pathway glioma: age younger than 5 years, radiation dose greater than 50 Gy, and radiation field involving the circle of Willis (35, 36). The aneurysm in case 5 may also have been associated with prior surgery (“pseudoaneurysm”) (37). These data suggest that radiation therapy for pituitary blastoma must be considered with special caution.

Cushing disease presenting in an infant suggests pituitary blastoma; other characteristic lesions in the patient, or a family history of DICER1 phenotypes, strengthens the possibility (3, 38). A pathologic diagnosis of pituitary blastoma should prompt genetic testing of the affected infant after parental informed consent, and in the tumor for DICER1 alterations. The results will dictate the need for genetic counseling and investigation of the family. A separate issue is the wisdom of screening an infant known to harbor DICER1 alterations for presymptomatic pituitary blastoma; this would require head magnetic resonance imaging with anesthesia in the first 24 months of life, perhaps more than once. Owing to its rarity as a DICER1 phenotype, the authors do not believe the risk-benefit ratio justifies such screening. We prefer genetic counseling and parental education as the best approach to helping families adjust to the possibilities of pituitary blastoma as well as the multiple other phenotypes in DICER1 syndrome. A counter argument in favor of central nervous system screening could be made in that several different intracranial neoplasms in young children can occur in DICER1 syndrome (discussed later); however, all are very rare phenotypes. General discussions of screening strategies in DICER1 syndrome have been published (5, 39, 40).

In 2014, de Kock et al expressed uncertainty about whether pituitary blastoma is a truly malignant tumor (4). Despite the “blastoma” designation and primitive histologic features, which recapitulate the embryologic pituitary, pituitary blastoma appears mostly to be a locally aggressive tumor; metastases have not been observed at diagnosis or during follow-up. Although the behavior of pituitary blastoma remains to be clarified, our findings suggest progression is not typical and that observation of these very young patients may be prudent after satisfactory resection. Perhaps proliferation of pituitary blastoma is limited to a certain age range, similar to other DICER1 phenotypes such as pleuropulmonary blastoma and cystic nephroma, which occur almost exclusively from ages 0 to 72 and 0 to 48 months, respectively (5). Multinodular goiter in DICER1 syndrome occurs at earlier ages than in the general population and also exhibits a strong predilection for females (9). DICER1-related gynecologic tumors (ovary, uterus, and fallopian tube) typically occur between ages 10 and 25 years, with some variation. The biological basis for the reported biases in DICER1 syndrome, for example, age of onset, goiter in females, and the propensity for gynecologic disease, are not understood. Age-confined presentations occur in other genetic disorders with endocrinologic features: In McCune-Albright syndrome, primary hypercortisolism presents during infancy and might abate spontaneously with age; in Carney complex, osteochondromyxoma presents typically before age 2 years and has been reported at birth, and nodular thyroid disease often appears by age 10 years (41-43).

Pituitary blastoma is only one of several intracranial tumors associated with DICER1 syndrome, including pineoblastoma, DICER1-mutant primary intracranial sarcoma, embryonal tumor with multilayered rosettes, and pleuropulmonary blastoma metastasis (13, 39, 44-51). Indeed, the quickly fatal second tumor in the region of the pineal gland in case 7 was radiographically considered a recurrence of pituitary blastoma, but at autopsy was revealed pathologically to be a primitive neuroectodermal tumor, which we interpret was likely a pineoblastoma, now recognized to occur in DICER1 syndrome.

In conclusion, we report the clinical features, molecular profiles, and outcome of 17 patients with pituitary blastoma, a distinctive phenotype of DICER1 syndrome. The rarity of pituitary blastoma and limited sample size hamper robust analyses of demographic and therapy-related prognostic factors, although it appears that complete or near complete surgical resection may be adequate for disease control in some patients and that extensive endocrinologic support is needed. Our description of the typical disease course and long-term outlook for children with pituitary blastoma will serve as a useful resource for physicians and families.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the families who have allowed their cases to be shared and analyzed. We also thank the medical teams from all participating institutions for providing exceptional care for these patients. We express our gratitude to Steffen Albrecht, MD, Department of Pathology, McGill University, for providing expertise on pathology review, and Eric Carolan, MD, for his neuroradiologic expertise. We thank Vani Shanker, PhD, ELS, for editing the manuscript.

Financial Support: This work was supported by the American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities (A.P.Y.L. and K.E.N.) and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (Grant No. FDN-148390 to W.D.F.).

Glossary

Abbreviations

- ACTH

adrenocorticotropin

- Bx

biopsy

- EFS

event-free survival

- GH

growth hormone

- GTR

gross total resection

- NTR

near-total resection

- OS

overall survival

- STR

subtotal resection

Additional Information

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Data Availability

Some or all data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article or in the data repositories listed in “References.”

References

- 1. Scheithauer BW, Kovacs K, Horvath E, et al. Pituitary blastoma. Acta Neuropathol. 2008;116(6):657-666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Scheithauer BW, Horvath E, Abel TW, et al. Pituitary blastoma: a unique embryonal tumor. Pituitary. 2012;15(3):365-373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sahakitrungruang T, Srichomthong C, Pornkunwilai S, et al. Germline and somatic DICER1 mutations in a pituitary blastoma causing infantile-onset Cushing’s disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99(8):E1487-E1492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. de Kock L, Sabbaghian N, Plourde F, et al. Pituitary blastoma: a pathognomonic feature of germ-line DICER1 mutations. Acta Neuropathol. 2014;128(1):111-122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Foulkes WD, Priest JR, Duchaine TF. DICER1: mutations, microRNAs and mechanisms. Nat Rev Cancer. 2014;14(10):662-672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. de Kock L, Wang YC, Revil T, et al. High-sensitivity sequencing reveals multi-organ somatic mosaicism causing DICER1 syndrome. J Med Genet. 2016;53(1):43-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Schultz KAP, Harris A, Doros LA, et al. Clinical and genetic aspects of ovarian stromal tumors: a report from the International Ovarian and Testicular Stromal Tumor Registry. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(15 Suppl):5520. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Doros L, Yang J, Dehner L, et al. DICER1 mutations in embryonal rhabdomyosarcomas from children with and without familial PPB-tumor predisposition syndrome. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2012;59(3):558-560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Khan NE, Bauer AJ, Schultz KAP, et al. Quantification of thyroid cancer and multinodular goiter risk in the DICER1 syndrome: a family-based cohort study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2017;102(5):1614-1622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. de Kock L, Sabbaghian N, Soglio DB, et al. Exploring the association between DICER1 mutations and differentiated thyroid carcinoma. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99(6):E1072-E1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Choong CS, Priest JR, Foulkes WD. Exploring the endocrine manifestations of DICER1 mutations. Trends Mol Med. 2012;18(9):503-505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chernock RD, Rivera B, Borrelli N, et al. Poorly differentiated thyroid carcinoma of childhood and adolescence: a distinct entity characterized by DICER1 mutations. Mod Pathol. 2020;33(7):1264-1274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. de Kock L, Priest JR, Foulkes WD, Alexandrescu S. An update on the central nervous system manifestations of DICER1 syndrome. Acta Neuropathol. 2020;139(4):689-701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. de Kock L, Wu MK, Foulkes WD. Ten years of DICER1 mutations: provenance, distribution, and associated phenotypes. Hum Mutat. 2019;40(11):1939-1953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Stewart DR, Best AF, Williams GM, et al. Neoplasm risk among individuals with a pathogenic germline variant in DICER1. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37(8):668-676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Salunke P, Bhansali A, Dutta P, et al. Congenital immature teratoma mimicking Cushing’s disease. Pediatr Neurosurg. 2010;46(1):46-50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gresh R, Piatt J, Walter A. A report of a child with a pituitary blastoma and DICER1 syndrome. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2015;62:70-71. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kalinin A, Strebkova N, Tiulpakov A, et al. A novel DICER1 gene mutation in a 10-month-old boy presenting with ACTH-secreting pituitary blastoma and lung cystic dysplasia. Paper presented at: 19th European Congress of Endocrinology; 2017, Lisbon. Endocrine Abstracts. 2017;49:EP1025. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Chhuon Y, Weon YC, Park G, Kim M, Park JB, Park SK. Pituitary blastoma in a 19-year-old woman: a case report and review of literature. World Neurosurg. 2020;139:310-313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Moriarty M, Hoe F. Cushing disease in a toddler: not all obese children are just fat. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2009;21(4):548-552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sumner TE, Volberg FM. Cushing’s syndrome in infancy due to pituitary adenoma. Pediatr Radiol. 1982;12(2):81-83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Pullins DI, Challa VR, Marshall RB, Davis CH Jr. ACTH-producing pituitary adenoma in an infant with cysts of the kidneys and lungs. Histopathology. 1984;8(1):157-163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Levy SR, Wynne CV Jr, Lorentz WB Jr. Cushing’s syndrome in infancy secondary to pituitary adenoma. Am J Dis Child. 1982;136(7):605-607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Miller WL, Townsend JJ, Grumbach MM, Kaplan SL. An infant with Cushing’s disease due to an adrenocorticotropin-producing pituitary adenoma. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1979;48(6):1017-1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. List JV, Sobottka S, Huebner A, et al. Cushing’s disease in a 7-month-old girl due to a tumor producing adrenocorticotropic hormone and thyreotropin-secreting hormone. Pediatr Neurosurg. 1999;31(1):7-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Maeder P, Gudinchet F, Rillet B, Theintz G, Meuli R. Cushing’s disease due to a giant pituitary adenoma in early infancy: CT and MRI features. Pediatr Radiol. 1996;26(1):48-50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Min HS, Lee SJ, Kim SK, Park SH. Pituitary adenoma with rich folliculo-stellate cells and mucin-producing epithelia arising in a 2-year-old girl. Pathol Int. 2007;57(9):600-605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Wildi-Runge S, Bahubeshi A, Carret A, et al. New phenotype in the familial DICER1 tumor syndrome: pituitary blastoma presenting at age 9 months. Endocr Rev. 2011;32(3):P1-P777. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Tompson SW, Young TL. Assaying the effects of splice site variants by exon trapping in a mammalian cell line. Bio Protoc. 2017;7(10):P1-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Liu APY, Kelsey M, Sabbaghian N, et al. Data from: Clinical outcomes and complications of pituitary blastoma. Figshare 2020. Deposited August 6, 2020. 10.6084/m9.figshare.12749846 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Liu APY, Kelsey M, Sabbaghian N, et al. Data from: Clinical outcomes and complications of pituitary blastoma. Figshare 2020. Deposited August 6, 2020. 10.6084/m9.figshare.12749849 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Raman S, Grimberg A, Waguespack SG, et al. Risk of neoplasia in pediatric patients receiving growth hormone therapy—a report from the Pediatric Endocrine Society Drug and Therapeutics Committee. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;100(6):2192-2203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Patterson BC, Chen Y, Sklar CA, et al. Growth hormone exposure as a risk factor for the development of subsequent neoplasms of the central nervous system: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99(6):2030-2037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Gkourogianni A, Lodish MB, Zilbermint M, et al. Death in pediatric Cushing syndrome is uncommon but still occurs. Eur J Pediatr. 2015;174(4):501-507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Hall MD, Bradley JA, Rotondo RL, et al. Risk of radiation vasculopathy and stroke in pediatric patients treated with proton therapy for brain and skull base tumors. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2018;101(4):854-859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ullrich NJ, Robertson R, Kinnamon DD, et al. Moyamoya following cranial irradiation for primary brain tumors in children. Neurology. 2007;68(12):932-938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kalapatapu VR, Shelton KR, Ali AT, Moursi MM, Eidt JF. Pseudoaneurysm: a review. Curr Treat Options Cardiovasc Med. 2008;10(2):173-183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Tatsi C, Flippo C, Stratakis CA. Cushing syndrome: old and new genes. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2020;34(2):101418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Schultz KAP, Williams GM, Kamihara J, et al. DICER1 and associated conditions: identification of at-risk individuals and recommended surveillance strategies. Clin Cancer Res. 2018;24(10):2251-2261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. van Engelen K, Villani A, Wasserman JD, et al. DICER1 syndrome: approach to testing and management at a large pediatric tertiary care center. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2018;65(1):e26720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Brown RJ, Kelly MH, Collins MT. Cushing syndrome in the McCune-Albright syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95(4):1508-1515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Golden T, Siordia JA. Osteochondromyxoma: review of a rare carney complex criterion. J Bone Oncol. 2016;5(4):194-197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Correa R, Salpea P, Stratakis CA. Carney complex: an update. Eur J Endocrinol. 2015;173(4):M85-M97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Liu APY, Gudenas B, Lin T, et al. Risk-adapted therapy and biological heterogeneity in pineoblastoma: integrated clinico-pathological analysis from the prospective, multi-center SJMB03 and SJYC07 trials. Acta Neuropathol. 2020;139(2):259-271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Li BK, Vasiljevic A, Dufour C, et al. Pineoblastoma segregates into molecular sub-groups with distinct clinico-pathologic features: a Rare Brain Tumor Consortium registry study. Acta Neuropathol. 2020;139(2):223-241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. de Kock L, Sabbaghian N, Druker H, et al. Germ-line and somatic DICER1 mutations in pineoblastoma. Acta Neuropathol. 2014;128(4):583-595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Sabbaghian N, Hamel N, Srivastava A, Albrecht S, Priest JR, Foulkes WD. Germline DICER1 mutation and associated loss of heterozygosity in a pineoblastoma. J Med Genet. 2012;49(7):417-419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Pfaff E, Aichmüller C, Sill M, et al. Molecular subgrouping of primary pineal parenchymal tumors reveals distinct subtypes correlated with clinical parameters and genetic alterations. Acta Neuropathol. 2020;139(2):243-257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Koelsche C, Mynarek M, Schrimpf D, et al. Primary intracranial spindle cell sarcoma with rhabdomyosarcoma-like features share a highly distinct methylation profile and DICER1 mutations. Acta Neuropathol. 2018;136(2):327-337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Uro-Coste E, Masliah-Planchon J, Siegfried A, et al. ETMR-like infantile cerebellar embryonal tumors in the extended morphologic spectrum of DICER1-related tumors. Acta Neuropathol. 2019;137(1):175-177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Lambo S, Gröbner SN, Rausch T, et al. The molecular landscape of ETMR at diagnosis and relapse. Nature. 2019;576(7786):274-280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Some or all data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article or in the data repositories listed in “References.”