This phase 3 randomized clinical trial compares the clinical efficacy of margetuximab vs trastuzumab, each with chemotherapy, in patients with pretreated ERBB2-positive advanced breast cancer.

Key Points

Question

Does margetuximab plus chemotherapy prolong progression-free survival and/or overall survival of patients with pretreated ERBB2-positive advanced breast cancer, relative to trastuzumab plus chemotherapy?

Findings

In the SOPHIA phase 3 randomized clinical trial of 536 patients with pretreated ERBB2-positive advanced breast cancer, margetuximab plus chemotherapy generated a statistically significant 24% relative risk reduction in the hazard of progression vs trastuzumab plus chemotherapy. After the second planned interim analysis of 270 deaths, median OS was 21.6 months with margetuximab vs 19.8 months with trastuzumab, and final analysis of OS will be reported subsequently.

Meaning

This trial demonstrates a head-to-head advantage of margetuximab (an Fc-engineered ERBB2-targeted antibody) compared with trastuzumab in a pretreated ERBB2-positive advanced breast cancer population.

Abstract

Importance

ERRB2 (formerly HER2)–positive advanced breast cancer (ABC) remains typically incurable with optimal treatment undefined in later lines of therapy. The chimeric antibody margetuximab shares ERBB2 specificity with trastuzumab but incorporates an engineered Fc region to increase immune activation.

Objective

To compare the clinical efficacy of margetuximab vs trastuzumab, each with chemotherapy, in patients with pretreated ERBB2-positive ABC.

Design, Setting, and Participants

The SOPHIA phase 3 randomized open-label trial of margetuximab plus chemotherapy vs trastuzumab plus chemotherapy enrolled 536 patients from August 26, 2015, to October 10, 2018, at 166 sites in 17 countries. Eligible patients had disease progression on 2 or more prior anti-ERBB2 therapies and 1 to 3 lines of therapy for metastatic disease. Data were analyzed from February 2019 to October 2019.

Interventions

Investigators selected chemotherapy before 1:1 randomization to margetuximab, 15 mg/kg, or trastuzumab, 6 mg/kg (loading dose, 8 mg/kg), each in 3-week cycles. Stratification factors were metastatic sites (≤2, >2), lines of therapy (≤2, >2), and chemotherapy choice.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Sequential primary end points were progression-free survival (PFS) by central blinded analysis and overall survival (OS). All α was allocated to PFS, followed by OS. Secondary end points were investigator-assessed PFS and objective response rate by central blinded analysis.

Results

A total of 536 patients were randomized to receive margetuximab (n = 266) or trastuzumab (n = 270). The median age was 56 (27-86) years; 266 (100%) women were in the margetuximab group, while 267 (98.9%) women were in the trastuzumab group. Groups were balanced. All but 1 patient had received prior pertuzumab, and 489 (91.2%) had received prior ado-trastuzumab emtansine. Margetuximab improved primary PFS over trastuzumab with 24% relative risk reduction (hazard ratio [HR], 0.76; 95% CI, 0.59-0.98; P = .03; median, 5.8 [95% CI, 5.5-7.0] months vs 4.9 [95% CI, 4.2-5.6] months; October 10, 2018). After the second planned interim analysis of 270 deaths, median OS was 21.6 months with margetuximab vs 19.8 months with trastuzumab (HR, 0.89; 95% CI, 0.69-1.13; P = .33; September 10, 2019), and investigator-assessed PFS showed 29% relative risk reduction favoring margetuximab (HR, 0.71; 95% CI, 0.58-0.86; P < .001; median, 5.7 vs 4.4 months; September 10, 2019). Margetuximab improved objective response rate over trastuzumab: 22% vs 16% (P = .06; October 10, 2018), and 25% vs 14% (P < .001; September 10, 2019). Incidence of infusion-related reactions, mostly in cycle 1, was higher with margetuximab (35 [13.3%] vs 9 [3.4%]); otherwise, safety was comparable.

Conclusions and Relevance

In this phase 3 randomized clinical trial, margetuximab plus chemotherapy had acceptable safety and a statistically significant improvement in PFS compared with trastuzumab plus chemotherapy in ERBB2-positive ABC after progression on 2 or more prior anti-ERBB2 therapies. Final OS analysis is expected in 2021.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02492711

Introduction

Addition of ERBB2 (formerly HER2)–targeting monoclonal antibodies to chemotherapy improves progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) in patients with ERBB2-positive advanced breast cancer (ABC).1,2,3,4 Generally, patients with ERBB2-positive metastatic breast cancer (BC) receive multiple lines of therapy, yet with rare exceptions, ERBB2-positive metastatic BC remains incurable.5,6

Margetuximab is a chimeric, Fc-engineered, immune-activating anti-ERBB2 immunoglobulin G1 (IgG1) monoclonal antibody that shares epitope specificity and Fc-independent antiproliferative effects with trastuzumab. Fc engineering of margetuximab alters 5 amino acids from wild-type IgG1 to increase affinity for activating Fcγ receptor (FcγR) CD16A (FcγRIIIa) and to decrease affinity for inhibitory FcγR CD32B (FcγRIIb).6,7 These effects are proposed to increase activation of innate and adaptive anti-ERBB2 immune responses, relative to trastuzumab.

Three FcγRs (CD16A, CD32A, and CD32B) expressed on immune effector cells regulate cellular activation by antibodies.8 CD16A can trigger antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC) by innate immune cells.9,10 Two CD16A polymorphisms at amino acid 158 bind IgG1 with higher (valine [V]) or lower (phenylalanine [F]) affinity.11 Clinical benefit of therapeutic antibodies, including trastuzumab,11,12,13,14,15 appears greater for patients with the high-affinity VV genotype compared with the lower-affinity FV and FF genotypes (CD16A-158F carriers), although not all studies observed this effect.16,17 Notably, most people (approximately 85%) are CD16A-158F allele carriers.11,12 A key feature of margetuximab’s engineered Fc domain is increased binding to all CD16A-158 V/F variants, relative to wild-type IgG1.

In a phase 1 study18 of margetuximab monotherapy in 66 patients with pretreated ERBB2-positive carcinomas, 4 of 24 (17%) evaluable patients with ABC had a confirmed partial response. Three patients continued margetuximab monotherapy for 4 or more years.19 Here we report initial results of a phase 3 randomized clinical trial of margetuximab vs trastuzumab, each combined with single-agent chemotherapy, in pretreated patients with ERBB2-positive ABC. In addition, we present an exploratory analysis of PFS and OS by FcγR genotype.

Methods

Study Design and Participants

This international, randomized, open-label, phase 3 study (SOPHIA; MacroGenics study protocol No. CP-MGAH22-04) enrolled patients at 166 centers in 17 countries. Eligible patients were aged 18 years or older with confirmed ERBB2-positive ABC by local or optional central testing of the most recent biopsy, following 2013 American Society of Clinical Oncology testing recommendations.20 Patients must have had progressive disease after 2 or more lines of prior ERBB2-targeted therapy, including pertuzumab, and 1 to 3 lines of nonhormonal metastatic BC therapy. Prior brain metastases were allowed if treated and stable. Trial conduct was in accordance with Good Clinical Practice guidelines and the Declaration of Helsinki. An independent ethics committee approved the protocol at each participating site. All patients provided written informed consent. The trial protocol and statistical analysis plan are available online (Supplement 1). This study followed the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) reporting guideline.

Randomization and Masking

Investigators chose 1 of 4 chemotherapies (capecitabine, eribulin, gemcitabine, or vinorelbine) for each eligible patient before 1:1 randomization by a permuted-blocks procedure. Stratification factors were metastatic sites (≤2, >2), lines of therapy for metastatic disease (≤2, >2), and chemotherapy choice. The trial was open label for patients and investigators but sponsor blinded with central blinded analysis (CBA) of PFS to prevent observer bias.

Procedures

Margetuximab was given intravenously at 15 mg/kg over 120 minutes on day 1 of each 21-day cycle. Trastuzumab was given intravenously at 6 mg/kg (over 30-90 minutes) on day 1 of each 21-day cycle after a loading dose of 8 mg/kg (over 90 minutes). Capecitabine was given orally at 1000 mg/m2 twice daily for 14 days followed by 7 days off. Eribulin, gemcitabine, and vinorelbine were given intravenously before antibody infusion at 1.4 mg/m2, 1000 mg/m2, and 25 to 30 mg/m2, respectively, on days 1 and 8 of each cycle. Margetuximab premedication was recommended, if not already given with chemotherapy: standard doses of acetaminophen or ibuprofen, diphenhydramine, ranitidine, and dexamethasone, or equivalents. Disease assessment was performed at baseline, every 6 weeks for the first 24 weeks of therapy, and then every 12 weeks until disease progression, adverse event (AE) necessitating discontinuation, consent withdrawal, or death. Safety was assessed at each visit, including AEs from study therapy initiation through the end-of-treatment visit, or 28 days after last administration of the study drug. Investigators assessed both event severity, using Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events, version 4.03, and causality. Left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) was monitored every 6 weeks for 24 weeks and then every 12 weeks thereafter. Optional CD16A, CD32A, and CD32B genotyping was performed by polymerase chain reaction amplification of blood DNA, followed by DNA sequencing.

Outcomes

Primary end points were PFS by CBA, with the α entirely allocated to PFS, and OS. The PFS was defined as time from randomization to disease progression or death from any cause. Secondary end points included investigator-assessed PFS and CBA-assessed objective response rate (ORR). The PFS and ORR were assessed according to Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors, version 1.1. Additional end points included safety, clinical benefit rate (CBR; ORR plus stable disease lasting at least 6 months), investigator-assessed ORR, response duration, antidrug antibodies, and exploratory evaluation of FcγR allelic variation on efficacy.

Statistical Analysis

For 90% power to detect median PFS improvement from 4 to 6 months (hazard ratio [HR], 0.67) at a 2-sided .05 significance level, 257 PFS events were needed. Primary PFS by CBA occurred after 257 PFS events or all patients were randomized, whichever occurred last. The OS was time from randomization to death from any cause and was to be assessed only if PFS was positive. For 80% power to detect a median OS improvement from 12 to 16 months (HR, 0.75) at a 2-sided .05 significance level, 385 OS events were needed. Three OS analyses were planned: first interim coincident with primary PFS analysis, second interim after 270 deaths, and final analysis after 385 events. All α was allocated to PFS, tested at a 2-sided .05 significance level. If PFS passed the test, then OS would be tested at the same significance level of 2-sided .05. The O’Brien-Fleming type Lan-DeMets α-spending function was applied for α allocation to each interim OS analysis.

The PFS and OS were assessed in the randomized, intention-to-treat population. Patients were censored at the last tumor assessment date for PFS and at the last time known to be alive for OS. The ORR and CBR were assessed in randomized patients with baseline measurable disease (response-evaluable population). For ORR analysis, if a patient’s response was missing, the patient was classified as not available. Safety and antidrug antibodies were assessed in randomized patients after any study treatment (safety population).

Kaplan-Meier methods were used to estimate median PFS, OS, and 95% CIs for each treatment group. The stratified log-rank test was used to compare time-to-event end points between groups. A stratified Cox proportional hazards model, with treatment as the only covariate, was used to estimate PFS and OS HRs and 95% CIs.

Prespecified PFS and OS subgroup analyses included chemotherapy choice, metastatic sites, lines of prior metastatic therapy, prior ado-trastuzumab emtansine use, hormone receptor status, ERBB2 status, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status, region, age, and race, as well as FCGR3A (FcγRIIIa/CD16A), FCGR2A (FcγRIIa/CD32A), and FCGR2B (FcγRIIb/CD32B) genotype. The HRs and 95% CIs for PFS in each subgroup were assessed using an unstratified Cox proportional hazards model with treatment as the only covariate.

If the primary PFS and OS were each positive, then secondary PFS and ORR end points were to be tested using the Hochberg step-up procedure for multiplicity adjustment. Investigator-assessed PFS was analyzed using the same methods as the primary PFS end point. The ORR was compared between groups by the stratified Mantel-Haenszel test. Data were analyzed from February 2019 to October 2019. Analyses were performed using SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute).

Results

Study Population

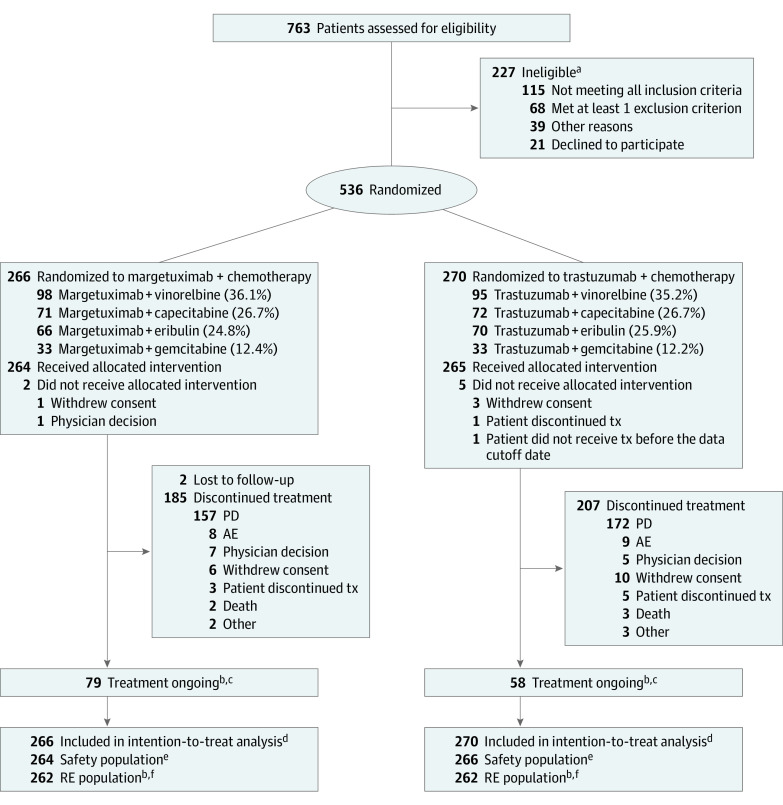

From July 2015 through October 2018, a total of 536 patients were enrolled at 166 centers in 17 countries and randomized to receive margetuximab plus chemotherapy (margetuximab group, n = 266) or trastuzumab plus chemotherapy (trastuzumab group, n = 270; Figure 1). The median age was 56 (27-86) years (55.0 [29-83] years for patients in the margetuximab group and 56.0 [27-86] years in the trastuzumab group); 266 (100%) women were in the margetuximab group, while 267 (98.9%) women were in the trastuzumab group. Investigator-selected chemotherapy choices were vinorelbine (n = 191, 35.6%), capecitabine (n = 143, 26.7%), eribulin (n = 136, 25.4%), and gemcitabine (n = 66, 12.3%). Patients received a median of 6 cycles of margetuximab vs 5 cycles of trastuzumab.

Figure 1. Patient Flow/Patient Disposition.

All randomized patients were included in the intention-to-treat population; randomized patients who received at least 1 dose of study treatment were included in the safety population; randomized patients with baseline measurable disease were included in the RE population. AE indicates adverse event; PD, progressive disease; RE, response evaluable; tx, treatment.

aA patient may have more than 1 reason for screening failure.

bAs of the October 10, 2018, cutoff.

cAs of the April 10, 2019, cutoff, 37 patients remained on margetuximab therapy vs 20 on trastuzumab therapy.

dAs of the October 10, 2018, cutoff and the September 10, 2019, cutoff.

eAs of the April 10, 2019, cutoff.

fAs of the September 10, 2019, cutoff, there were 266 margetuximab-treated patients and 270 trastuzumab-treated patients in the RE population.

Baseline characteristics were balanced across groups (Table 1). All patients had received prior trastuzumab; all but 1 had received prior pertuzumab, and 489 (91.2%) had received prior ado-trastuzumab emtansine. One-third of patients in both groups received 3 or more prior therapies for metastatic BC (margetuximab, 92 of 266 [34.6%]; vs trastuzumab, 87 of 270 [32.2%]).

Table 1. Demographic and Baseline Disease Characteristics in the Intention-to-Treat Population (n = 536).

| Characteristic | No. (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Margetuximab plus chemotherapy (n = 266) | Trastuzumab plus chemotherapy (n = 270) | |

| Female sex | 266 (100) | 267 (98.9) |

| Age, median (range), y | 55.0 (29-83) | 56.0 (27-86) |

| Race | ||

| Asian | 20 (7.5) | 14 (5.2) |

| Black or African American | 16 (6.0) | 12 (4.4) |

| White | 205 (77.1) | 222 (82.2) |

| Other | 25 (9.4) | 22 (8.1) |

| Region | ||

| Europe | 152 (57.1) | 138 (51.1) |

| North America | 85 (32.0) | 102 (37.8) |

| Other | 29 (10.9) | 30 (11.1) |

| ECOG performance status | ||

| 0 | 149 (56.0) | 161 (59.6) |

| 1 | 117 (44.0) | 109 (40.4) |

| Disease extent at screening | ||

| Metastatic | 260 (97.7) | 264 (97.8) |

| Locally advanced, unresectable | 6 (2.3) | 6 (2.2) |

| Measurable disease | 262 (98.5) | 262 (97.0) |

| No. of metastatic sites | ||

| ≤2 | 138 (51.9) | 144 (53.3) |

| >2 | 128 (48.1) | 126 (46.7) |

| Common sites of metastases (≥10% of patients) at study entry | ||

| Bone | 153 (57.5) | 155 (57.4) |

| Lymph node | 140 (52.6) | 151 (55.9) |

| Lung | 124 (46.6) | 126 (46.7) |

| Liver | 93 (35.0) | 95 (35.2) |

| Breast | 44 (16.5) | 37 (13.7) |

| Skin | 41 (15.4) | 32 (11.9) |

| Brain | 37 (13.9) | 34 (12.6) |

| Combined ER and PR status | ||

| ER positive, PR positive, or both | 164 (61.7) | 170 (63.0) |

| ER negative and PR negative | 102 (38.4) | 98 (36.3) |

| Settings of prior systemic/hormonal therapy | ||

| Adjuvant and/or neoadjuvant | 158 (59.4) | 145 (53.7) |

| Metastatic only | 108 (40.6) | 125 (46.3) |

| No. of prior lines of therapy in the metastatic setting | ||

| ≤2 | 175 (65.8) | 180 (66.7) |

| >2 | 91 (34.2) | 90 (33.3) |

| Prior systemic therapy in early and metastatic settings | ||

| Chemotherapy | ||

| Taxane | 252 (94.7) | 249 (92.2) |

| Anthracycline | 118 (44.4) | 110 (40.7) |

| Platinum | 34 (12.8) | 40 (14.8) |

| ERBB2-targeted therapy | ||

| Trastuzumab | 266 (100) | 270 (100) |

| Pertuzumab | 266 (100) | 269 (99.6) |

| Ado-trastuzumab emtansine | 242 (91.0) | 247 (91.5) |

| Lapatinib | 41 (15.4) | 39 (14.4) |

| Other | 6 (2.3) | 6 (2.2) |

| Endocrine therapy | 126 (47.4) | 133 (49.3) |

Abbreviations: ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; ER, estrogen receptor; PR, progesterone receptor.

Efficacy

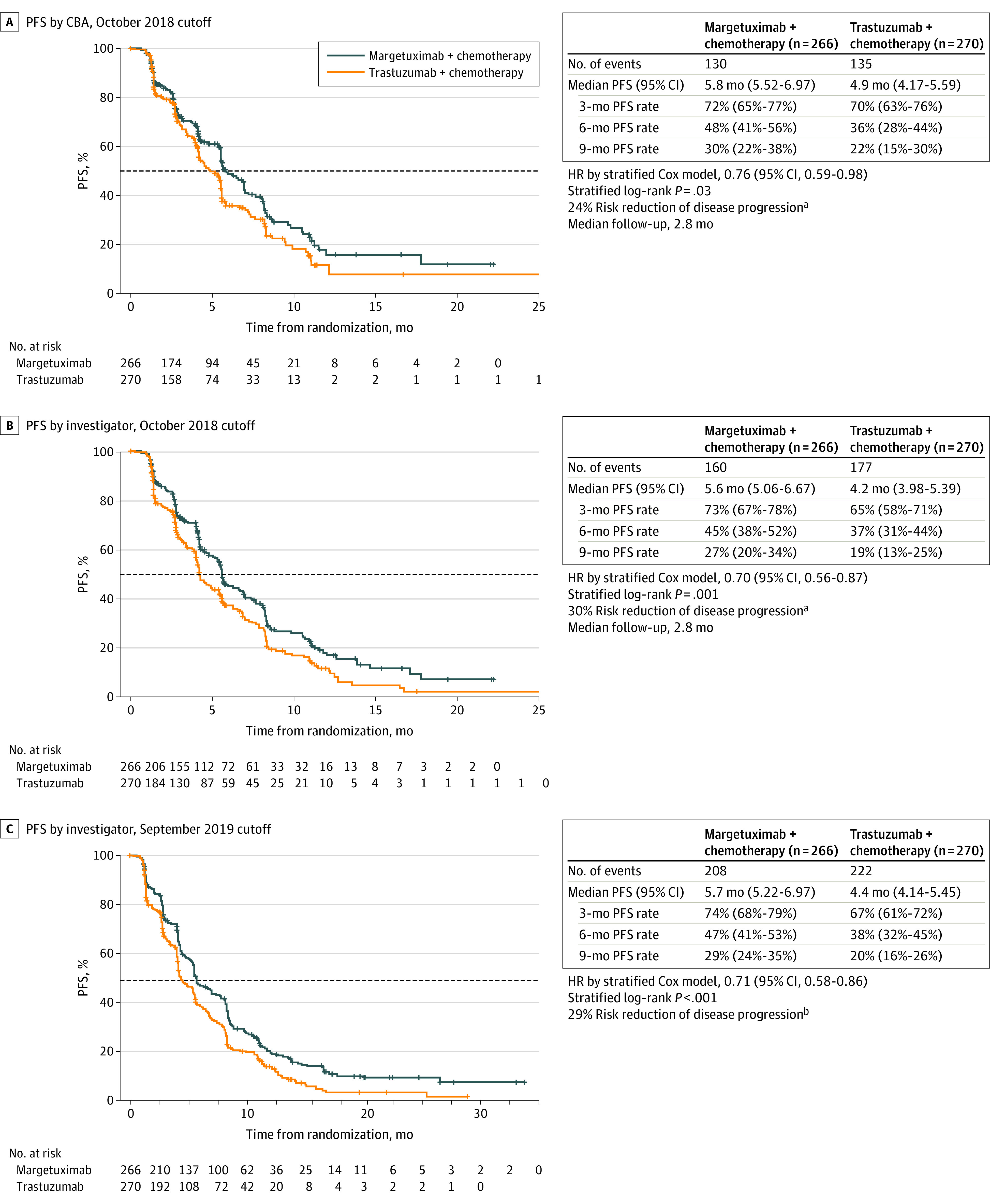

Primary PFS analysis was triggered by last randomization (October 10, 2018), after 265 PFS events. On that date, 79 (30%) vs 58 (22%) patients remained on margetuximab vs trastuzumab, respectively, including 13 (5%) and 5 (2%) remaining exclusively on margetuximab vs trastuzumab. Margetuximab plus chemotherapy prolonged centrally assessed PFS (HR, 0.76; 95% CI, 0.59-0.98; P = .03; median PFS, 5.8 [95% CI, 5.5-7.0] months vs 4.9 [95% CI, 4.2-5.6] months; Figure 2A), with a 24% PFS relative risk reduction over trastuzumab plus chemotherapy, meeting the primary end point of the study. The test of proportional hazards assumption indicated that the proportional hazards assumption was not violated. Investigator-assessed PFS based on 337 events was also greater with margetuximab than with trastuzumab (HR, 0.70; 95% CI, 0.56-0.87; P = .001; median, 5.6 vs 4.2 months; Figure 2B), with a 30% PFS relative risk reduction over trastuzumab. Coincident with the second interim OS analysis, updated investigator-assessed PFS based on 430 PFS events showed increased statistical significance in favor of margetuximab with a similar HR (HR, 0.71; 95% CI, 0.58-0.86; P < .001; median, 5.7 vs 4.4 months; Figure 2C).

Figure 2. Progression-Free Survival (PFS) in the Intention-to-Treat Population.

A, Kaplan-Meier estimates of PFS in the intention-to-treat population by central blinded analysis (CBA), based on the October 2018 cutoff. B, Kaplan-Meier estimates of PFS in the intention-to-treat population by investigator assessment, based on the October 2018 cutoff. C, Kaplan-Meier estimates of PFS in the intention-to-treat population by investigator assessment, based on the September 2019 cutoff. The dashed line indicates 50% (median PFS); plus signs, censored data. HR indicates hazard ratio.

aPFS analysis was triggered by last randomization on October 10, 2018, after 265 PFS events occurred.

bPFS analysis performed as of September 10, 2019, after 430 PFS events occurred.

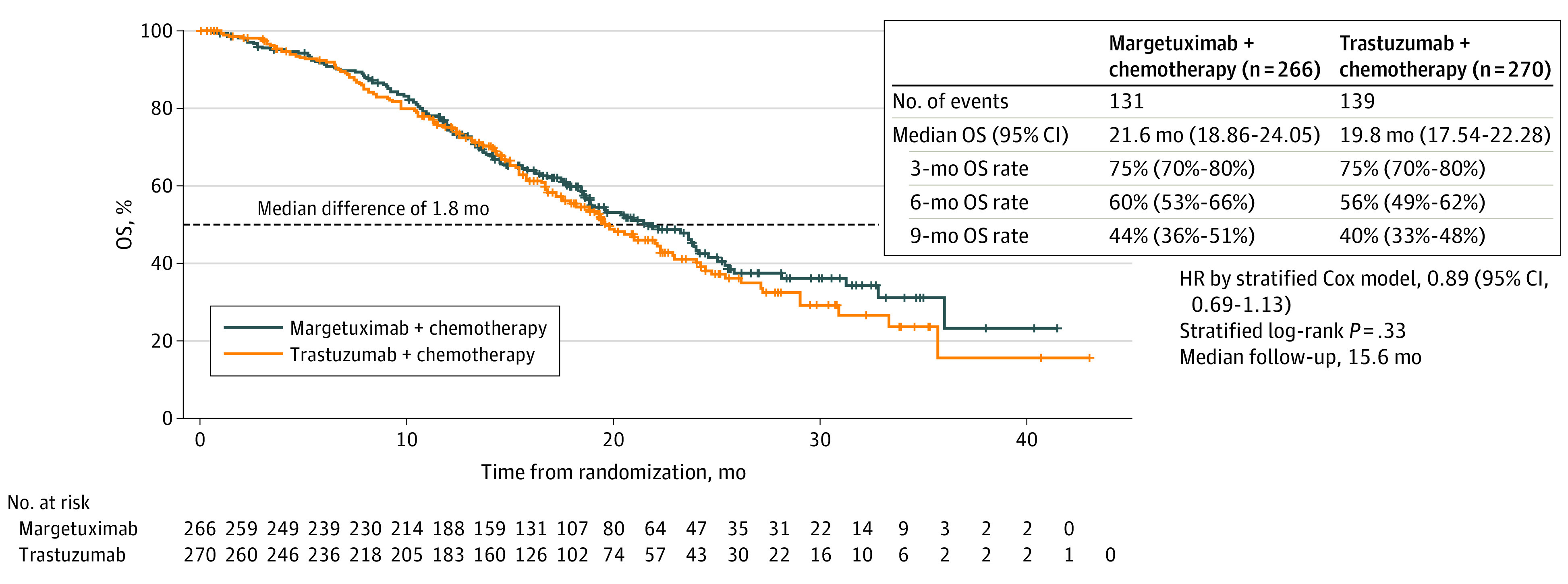

The OS analysis after 270 deaths (70% of 385 final required events) occurred on September 10, 2019, after 131 (49.2%) and 139 (51.5%) OS events in the margetuximab and trastuzumab groups, respectively. Median OS was 21.6 months with margetuximab and 19.8 months with trastuzumab (HR, 0.89; 95% CI, 0.69-1.13; P = .33; Figure 3). The stopping threshold was not reached; final OS analysis will occur after 385 deaths (anticipated in 2021).

Figure 3. Overall Survival (OS) in the Intention-to-Treat Population (September 2019 Cutoff)a.

Kaplan-Meier estimates of OS in the intention-to-treat population, based on the September 2019 cutoff. The dashed line indicates 50% (median OS); plus signs, censored data. HR indicates hazard ratio.

aOS analysis performed as of September 10, 2019, data cutoff, after 270 of 385 (70%) events needed for final OS analysis had occurred.

Among 524 response-evaluable patients, margetuximab recipients had higher blinded ORR (22% vs 16%; P = .06) and CBR (37% vs 25%; P = .003) than trastuzumab recipients (eTable 1 in Supplement 2). These rates were similar at the September 2019 cutoff when investigator-assessed ORR and CBR were 25% vs 14% (P < .001) and 48% vs 36% (P = .003), respectively (eTable 1 in Supplement 2). Median response duration was similar between treatment groups: 6.1 vs 6.0 months (October 10, 2018, CBA) and 6.9 vs 7.0 months (September 10, 2019, investigator assessed).

Prespecified exploratory subgroup analyses of primary PFS (October 10, 2018, cutoff) and second interim OS (September 10, 2019, cutoff) by CD16A genotype are shown in eFigures 1 and 2 in Supplement 2, respectively. Genotyping was available for 506 patients (94%). Study groups were in Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium for all 3 FCGR genotypes (eTable 2 in Supplement 2). Baseline characteristics of patients assigned to margetuximab vs trastuzumab by FcγR genotype are shown in eTable 3 in Supplement 2. The interim OS per treatment group by CD16A genotype is shown in eFigure 3 in Supplement 2. Efficacy outcomes by CD32A and CD32B are shown in eFigure 4 and eFigure 5 in Supplement 2.

Safety

As of April 10, 2019, which provided 6 additional months of safety follow-up after the primary PFS analysis, the safety population included 264 margetuximab and 266 trastuzumab recipients. Common AEs (≥20% of patients), regardless of causality, included fatigue, nausea, diarrhea, and neutropenia in both groups (Table 2), as well as vomiting (margetuximab group) and anemia (trastuzumab group). Grade 3 or greater AEs in at least 5% of patients included neutropenia and anemia in both groups, as well as fatigue in the margetuximab group and febrile neutropenia in the trastuzumab group. Discontinuations owing to AEs were similar (margetuximab, 8 of 266 [3.0%]; trastuzumab, 7 of 270 [2.6%]; eTable 4 in Supplement 2). Adverse events leading to death were reported in 5 patients (margetuximab, n = 3 [1.1%]; trastuzumab, n = 2 [0.8%]; eTable 4 in Supplement 2); none were considered treatment related.

Table 2. Adverse Events in the Safety Population, Regardless of Causality (April 2019 Cutoff).

| Adverse event | No. (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Margetuximab plus chemotherapy (n = 264) | Trastuzumab plus chemotherapy (n = 266) | |||

| All gradea | Grade ≥3b | All gradea | Grade ≥3b | |

| Nonhematologic | ||||

| Fatiguec | 111 (42.0) | 13 (4.9) | 94 (35.3) | 8 (3.0) |

| Nausea | 86 (32.6) | 3 (1.1) | 86 (32.3) | 1 (0.4) |

| Diarrhea | 66 (25.0) | 6 (2.3) | 67 (25.2) | 6 (2.3) |

| Constipation | 51 (19.3) | 2 (0.8) | 44 (16.5) | 2 (0.8) |

| Vomitingd | 54 (20.5) | 2 (0.8) | 38 (14.3) | 4 (1.5) |

| Pyrexia | 50 (18.9) | 1 (0.4) | 37 (13.9) | 1 (0.4) |

| Headache | 47 (17.8) | 0 | 42 (15.8) | 0 |

| Alopecia | 47 (17.8) | 0 | 39 (14.7) | 0 |

| Asthenia | 47 (17.8) | 6 (2.3) | 33 (12.4) | 5 (1.9) |

| Decreased appetite | 38 (14.4) | 1 (0.4) | 36 (13.5) | 1 (0.4) |

| Infusion-related reactione,f | 35 (13.3) | 4 (1.5) | 9 (3.4) | 0 |

| Cough | 37 (14.0) | 1 (0.4) | 31 (11.7) | 0 |

| PPE syndrome | 33 (12.5) | 1 (0.4) | 41 (15.4) | 8 (3.0) |

| Dyspnea | 34 (12.9) | 3 (1.1) | 28 (10.5) | 6 (2.3) |

| Pain in extremity | 30 (11.4) | 2 (0.8) | 23 (8.6) | 0 |

| Arthralgia | 27 (10.2) | 0 | 23 (8.6) | 1 (0.4) |

| Stomatitis | 27 (10.2) | 2 (0.8) | 21 (7.9) | 0 |

| Peripheral neuropathy | 26 (9.8) | 1 (0.4) | 28 (10.5) | 3 (1.1) |

| Urinary tract infection | 26 (9.8) | 2 (0.8) | 28 (10.5) | 3 (1.1) |

| Mucosal inflammationg | 26 (9.8) | 0 | 8 (3.0) | 1 (0.4) |

| Abdominal pain | 25 (9.5) | 4 (1.5) | 37 (13.9) | 3 (1.1) |

| Dizziness | 25 (9.5) | 1 (0.4) | 16 (6.0) | 0 |

| Hypokalemia | 16 (6.1) | 4 (1.5) | 19 (7.1) | 4 (1.5) |

| Hypertension | 14 (5.3) | 5 (1.9) | 6 (2.3) | 2 (0.8) |

| Pneumonia | 9 (3.4) | 5 (1.9) | 9 (3.4) | 7 (2.6) |

| Pleural effusion | 8 (3.0) | 2 (0.8) | 14 (5.3) | 4 (1.5) |

| Syncope | 4 (1.5) | 4 (1.5) | 0 | 0 |

| Hematologic | ||||

| Neutropeniah | 75 (28.4) | 52 (19.7) | 55 (20.7) | 33 (12.4) |

| Anemiai | 49 (18.6) | 13 (4.9) | 62 (23.3) | 17 (6.4) |

| Neutrophil count decreased | 33 (12.5) | 23 (8.7) | 39 (14.7) | 28 (10.5) |

| ALT increased | 24 (9.1) | 5 (1.9) | 26 (9.8) | 4 (1.5) |

| AST increased | 22 (8.3) | 7 (2.7) | 34 (12.8) | 3 (1.1) |

| WBC decreased | 19 (7.2) | 5 (1.9) | 27 (10.2) | 8 (3.0) |

| Leukopenia | 14 (5.3) | 4 (1.5) | 10 (3.8) | 1 (0.4) |

| Febrile neutropeniaj | 8 (3.0) | 8 (3.0) | 13 (4.9) | 13 (4.9) |

Abbreviations: ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; PPE, palmar-plantar erythrodysesthesia; WBC, white blood cell.

All-grade adverse events with ≥10% incidence in either treatment group.

Grade ≥3 with an incidence of ≥2% in either treatment group.

Exact test P value for nonprespecified comparison of all-grade fatigue between treatment groups (42.0% vs 35.3%): P = .13. Exact test P value for nonprespecified comparison of grade ≥3 fatigue between treatment groups (4.9% vs 3.0%): P = .28.

Exact test P value for nonprespecified comparison of all-grade vomiting between treatment groups (20.5% vs 14.3%): P = .07.

Infusion-related reactions include hypersensitivity/anaphylactic/anaphylactoid reactions.

Exact test P value for nonprespecified comparison of all-grade infusion-related reaction between treatment groups (13.3% vs 3.4%): P < .001.

Exact test P value for nonprespecified comparison of all-grade mucosal inflammation between treatment groups (9.8% vs 3.0%): P = .001.

Exact test P value for nonprespecified comparison of all-grade neutropenia between treatment groups (28.4% vs 20.7%): P = .04. Exact test P value for nonprespecified comparison of grade ≥3 neutropenia between treatment groups (19.7% vs 12.4%): P = .02.

Exact test P value for nonprespecified comparison of all grade anemia between treatment groups (18.6% vs 23.3%): P = .20.

Exact test P value for nonprespecified comparison of grade ≥3 febrile neutropenia between treatment groups (3.0% vs 4.9%): P = .37.

Adverse events of special interest included infusion-related reactions (IRRs) and left ventricular (LV) dysfunction. All-grade IRRs were more common with margetuximab than with trastuzumab (35 [13.3%] vs 9 [3.4%], respectively; Table 2). Most IRRs were grade 1 or 2, occurred on cycle 1, day 1, and resolved within 24 hours. Grade 3 IRRs on cycle 1, day 1 were reported in 4 (1.5%) margetuximab-treated patients. Of these 4 patients, 2 (0.8%) continued therapy for 5 or more cycles and 2 (0.8%) discontinued owing to IRRs (eTable 4 in Supplement 2). No trastuzumab recipients had grade 3 IRRs. Adverse events of LV dysfunction occurred in 7 patients (3%) in each treatment group (eTable 4 in Supplement 2). Grade 3 LV dysfunction AEs were observed in 3 margetuximab recipients (1.1%) and 1 trastuzumab recipient (0.4%). Monitoring of LVEF led to dose delay or discontinuation in 4 margetuximab-treated (1.5%) vs 6 trastuzumab-treated patients (2.3%). All LVEF reductions detected by monitoring were asymptomatic. Reductions in LVEF were reversible for all patients with complete follow-up.

Discussion

The phase 3 SOPHIA trial compared margetuximab, a novel chimeric Fc-engineered anti-ERBB2 antibody, to trastuzumab, each with chemotherapy, in patients with pretreated ERBB2-positive ABC. This randomized clinical trial was positive for its PFS primary end point. Margetuximab plus chemotherapy led to an independently assessed PFS benefit vs trastuzumab plus chemotherapy, with a 24% relative risk reduction. Investigator-assessed PFS complemented primary blinded PFS with a 29% relative risk reduction. No conclusion can be drawn at this time about OS based on the 2 OS interim analyses conducted after 40% and 70% of target OS events (immature data); final analysis of the effect of margetuximab vs trastuzumab on survival will occur after 385 deaths (anticipated in 2021).

Margetuximab plus chemotherapy had acceptable safety, comparable with control trastuzumab plus chemotherapy. Although IRRs were increased with margetuximab, almost all occurred during the first infusion only, and the observed margetuximab IRR rate aligns with that in published literature on trastuzumab first exposure (16%).21 In a nonrandomized infusion safety substudy, margetuximab was administered over 30 minutes from cycle 2 onward and appeared well tolerated with no increase in IRR risk, supporting 30-minute margetuximab infusions after cycle 1.22 There was no increase in cardiac toxic effects with margetuximab compared with trastuzumab.

The SOPHIA study also tested the hypothesis that altering Fc–FcγR interactions can drive clinical benefit. Trastuzumab triggers ADCC23 via activation of FcγRIIIa (CD16A).8 Associations between efficacy and CD16A polymorphism in trastuzumab-treated patients with early and advanced BC suggest lower immune activation in CD16A-158F allele carriers compared with VV homozygotes.10,11,12,14,24 Diminished clinical response to trastuzumab for these CD16A-158F carriers suggests these patients may benefit from an antibody with enhanced Fc-dependent immune activation.11,12,24 Margetuximab Fc engineering increases affinity for both CD16A allotypes, enhances ADCC potency over trastuzumab with effector cells of all CD16A genotypes (FF, FV, VV), albeit proportionally more for CD16A-158F carriers under certain conditions, and boosts activity against ERBB2-positive BC xenografts in mice transgenic for human CD16A-158F.6,25 Exploratory PFS analysis by CD16A genotype suggested that presence of a CD16A-158F allele may predict margetuximab benefit over trastuzumab. Early OS results showed a similar pattern. Conversely, there was no margetuximab benefit in the smaller CD16A-158VV group in this study of heavily pretreated patients. There is no clear biological explanation for the observation that margetuximab provided no clinical benefit in CD16A-158VV homozygotes compared with trastuzumab, although there was an imbalance in poor prognostic features between the 2 groups.

Increasing evidence implicates adaptive immunity in the clinical activity of anti-ERBB2 monoclonal antibodies.26 ERBB2-specific T-cell and antibody responses were observed in 50% to 78% and 42% to 69%, respectively, of trastuzumab-treated patients with ERBB2-positive BC.10,24,26,27,28,29,30 Correspondingly, increases in ERBB2-specific T-cell and antibody responses were observed in 98% and 94%, respectively, of pretreated phase 1 study patients receiving margetuximab monotherapy.31

This trial demonstrates a small but statistically significant PFS benefit of margetuximab plus chemotherapy over trastuzumab plus chemotherapy in patients with ERBB2-positive ABC who progressed after treatment with trastuzumab, pertuzumab, and ado-trastuzumab emtansine.1,2,4,32 Alternatives for this patient population include neratinib, tucatinib, and trastuzumab deruxtecan, which have emerged as active regimens, albeit with different levels of effectiveness, and all with notable toxic effects. Margetuximab may have a role for patients in this setting who are unable, or unwilling, to tolerate toxic effects of these novel therapies.

Limitations

Limitations of this trial include that the primary end point did not allocate α to the CD16A analysis and that patients with active brain metastases were not included. An ongoing neoadjuvant investigator-sponsored trial is comparing margetuximab vs trastuzumab in patients with the low-affinity CD16A genotype (the MARGetuximab Or Trastuzumab trial, known as MARGOT; NCT04425018). Immune-mediated therapies, such as margetuximab, may be more effective in the earlier disease setting where the immune system is relatively intact.

Conclusions

The chimeric antibody margetuximab shares ERBB2 specificity with trastuzumab but incorporates an engineered Fc region to optimize immune activation. This phase 3 randomized clinical trial demonstrates improvement in PFS of margetuximab in combination with chemotherapy vs trastuzumab plus chemotherapy in patients with pretreated ERBB2-positive ABC, which remains typically incurable.

Trial Protocol

eTable 1. Hardy-Weinberg Equilibrium Analysis of CD16A, CD32A, and CD32B Genotype Frequencies

eTable 2. Demographic and Baseline Disease Characteristics by CD16A-158 Genotype

eTable 3. Objective Response Rate (ORR) and Clinical Benefit Rate (CBR)

eTable 4. Summary of Adverse Events in the Safety Population (Apr 2019 Cutoff)

eFigure 1. Prespecified Exploratory Primary PFS Analysis, by CD16A Genotype (Oct 2018 Cutoff)

eFigure 2. Pre-specified Exploratory OS Analysis, per CD16A Genotype by Treatment Group (Sep 2019 Cutoff)

eFigure 3. Overall Survival (OS) per Treatment Group by CD16A Genotype (Sep 2019 Cutoff)

eFigure 4. Prespecified Exploratory PFS Subgroup Analyses (CBA) – Oct 2018 Cutoff

eFigure 5. Prespecified Exploratory OS Subgroup Analyses – Sep 2019 Cutoff

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Cardoso F, Senkus E, Costa A, et al. 4th ESO-ESMO international consensus guidelines for advanced breast cancer (ABC 4). Ann Oncol. 2018;29(8):1634-1657. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdy192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Giordano SH, Temin S, Chandarlapaty S, et al. Systemic therapy for patients with advanced human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive breast cancer: ASCO clinical practice guideline update. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(26):2736-2740. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2018.79.2697 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mendes D, Alves C, Afonso N, et al. The benefit of HER2-targeted therapies on overall survival of patients with metastatic HER2-positive breast cancer—a systematic review. Breast Cancer Res. 2015;17:140. doi: 10.1186/s13058-015-0648-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.National Comprehensive Cancer Network . NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: breast cancer (v3.2020). Accessed March 13, 2020. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/breast.pdf

- 5.Palumbo R, Sottotetti F, Riccardi A, et al. Which patients with metastatic breast cancer benefit from subsequent lines of treatment? an update for clinicians. Ther Adv Med Oncol. 2013;5(6):334-350. doi: 10.1177/1758834013508197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nordstrom JL, Gorlatov S, Zhang W, et al. Anti-tumor activity and toxicokinetics analysis of MGAH22, an anti-HER2 monoclonal antibody with enhanced Fcγ receptor binding properties. Breast Cancer Res. 2011;13(6):R123. doi: 10.1186/bcr3069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stavenhagen JB, Gorlatov S, Tuaillon N, et al. Fc optimization of therapeutic antibodies enhances their ability to kill tumor cells in vitro and controls tumor expansion in vivo via low-affinity activating Fcgamma receptors. Cancer Res. 2007;67(18):8882-8890. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0696 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nimmerjahn F, Ravetch JV. Fcgamma receptors as regulators of immune responses. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8(1):34-47. doi: 10.1038/nri2206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen X, Song X, Li K, Zhang T. FcγR-binding is an important functional attribute for immune checkpoint antibodies in cancer immunotherapy. Front Immunol. 2019;10:292. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.00292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Muntasell A, Cabo M, Servitja S, et al. Interplay between natural killer cells and anti-HER2 antibodies: perspectives for breast cancer immunotherapy. Front Immunol. 2017;8:1544. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.01544 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Musolino A, Naldi N, Bortesi B, et al. Immunoglobulin G fragment C receptor polymorphisms and clinical efficacy of trastuzumab-based therapy in patients with HER-2/neu-positive metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(11):1789-1796. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.8957 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gavin PG, Song N, Kim SR, et al. Association of polymorphisms in FCGR2A and FCGR3A with degree of trastuzumab benefit in the adjuvant treatment of ERBB2/HER2-positive breast cancer: analysis of the NSABP B-31 Trial. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3(3):335-341. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.4884 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Magnes T, Melchardt T, Hufnagl C, et al. The influence of FCGR2A and FCGR3A polymorphisms on the survival of patients with recurrent or metastatic squamous cell head and neck cancer treated with cetuximab. Pharmacogenomics J. 2018;18(3):474-479. doi: 10.1038/tpj.2017.37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Musolino A, Naldi N, Dieci MV, et al. Immunoglobulin G fragment C receptor polymorphisms and efficacy of preoperative chemotherapy plus trastuzumab and lapatinib in HER2-positive breast cancer. Pharmacogenomics J. 2016;16(5):472-477. doi: 10.1038/tpj.2016.51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Persky DO, Dornan D, Goldman BH, et al. Fc gamma receptor 3a genotype predicts overall survival in follicular lymphoma patients treated on SWOG trials with combined monoclonal antibody plus chemotherapy but not chemotherapy alone. Haematologica. 2012;97(6):937-942. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2011.050419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hurvitz SA, Betting DJ, Stern HM, et al. Analysis of Fcγ receptor IIIa and IIa polymorphisms: lack of correlation with outcome in trastuzumab-treated breast cancer patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18(12):3478-3486. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-2294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Norton N, Olson RM, Pegram M, et al. Association studies of Fcγ receptor polymorphisms with outcome in HER2+ breast cancer patients treated with trastuzumab in NCCTG (Alliance) Trial N9831. Cancer Immunol Res. 2014;2(10):962-969. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-14-0059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bang YJ, Giaccone G, Im SA, et al. First-in-human phase 1 study of margetuximab (MGAH22), an Fc-modified chimeric monoclonal antibody, in patients with HER2-positive advanced solid tumors. Ann Oncol. 2017;28(4):855-861. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdx002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Im SA, Bang YJ, Oh DY, et al. Long-term responders to single-agent margetuximab, an Fc-modified anti-HER2 monoclonal antibody, in metastatic HER2+ breast cancer patients with prior anti-HER2 therapy. Abstract P6-18-11. Cancer Res. 2019;79(4)(suppl). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wolff AC, Hammond ME, Hicks DG, et al. ; American Society of Clinical Oncology; College of American Pathologists . Recommendations for human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 testing in breast cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology/College of American Pathologists clinical practice guideline update. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(31):3997-4013. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.50.9984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thompson LM, Eckmann K, Boster BL, et al. Incidence, risk factors, and management of infusion-related reactions in breast cancer patients receiving trastuzumab. Oncologist. 2014;19(3):228-234. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2013-0286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gradishar WJ, Im S-A, Cardoso F, et al. Phase 3 SOPHIA study of margetuximab + chemotherapy vs trastuzumab + chemotherapy in patients with HER2+ metastatic breast cancer after prior anti-HER2 therapies: infusion time substudy results. 2019. San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium; P1-18-04. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Arnould L, Gelly M, Penault-Llorca F, et al. Trastuzumab-based treatment of HER2-positive breast cancer: an antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity mechanism? Br J Cancer. 2006;94(2):259-267. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602930 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Norton N, Fox N, McCarl CA, et al. Generation of HER2-specific antibody immunity during trastuzumab adjuvant therapy associates with reduced relapse in resected HER2 breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2018;20(1):52. doi: 10.1186/s13058-018-0989-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu L, Yang Y, Burns R, et al. Margetuximab mediates greater Fc-dependent anti-tumor activities than trastuzumab or pertuzumab in vitro. Abstract 1538. Cancer Res 2019;79(13)(suppl). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Musolino A, Boggiani D, Pellegrino B, et al. Role of innate and adaptive immunity in the efficacy of anti-HER2 monoclonal antibodies for HER2-positive breast cancer. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2020;149:102927. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2020.102927 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Disis ML, Stanton SE. Can immunity to breast cancer eliminate residual micrometastases? Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19(23):6398-6403. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-0734 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Knutson KL, Clynes R, Shreeder B, et al. Improved survival of HER2+ breast cancer patients treated with trastuzumab and chemotherapy is associated with host antibody immunity against the HER2 intracellular domain. Cancer Res. 2016;76(13):3702-3710. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-3091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Muraro E, Comaro E, Talamini R, et al. Improved Natural Killer cell activity and retained anti-tumor CD8(+) T cell responses contribute to the induction of a pathological complete response in HER2-positive breast cancer patients undergoing neoadjuvant chemotherapy. J Transl Med. 2015;13:204. doi: 10.1186/s12967-015-0567-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Taylor C, Hershman D, Shah N, et al. Augmented HER-2 specific immunity during treatment with trastuzumab and chemotherapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13(17):5133-5143. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-0507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nordstrom JL, Muth J, Erskine CL, et al. High frequency of HER2-specific immunity observed in patients (pts) with HER2+ cancers treated with margetuximab (M), an Fc-enhanced anti-HER2 monoclonal antibody (mAb). Abstract 1030. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37(15)(suppl). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Martínez-Jañez N, Chacón I, de Juan A, et al. Anti-HER2 therapy beyond second-line for HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer: a short review and recommendations for several clinical scenarios from a Spanish expert panel. Breast Care (Basel). 2016;11(2):133-138. doi: 10.1159/000443601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial Protocol

eTable 1. Hardy-Weinberg Equilibrium Analysis of CD16A, CD32A, and CD32B Genotype Frequencies

eTable 2. Demographic and Baseline Disease Characteristics by CD16A-158 Genotype

eTable 3. Objective Response Rate (ORR) and Clinical Benefit Rate (CBR)

eTable 4. Summary of Adverse Events in the Safety Population (Apr 2019 Cutoff)

eFigure 1. Prespecified Exploratory Primary PFS Analysis, by CD16A Genotype (Oct 2018 Cutoff)

eFigure 2. Pre-specified Exploratory OS Analysis, per CD16A Genotype by Treatment Group (Sep 2019 Cutoff)

eFigure 3. Overall Survival (OS) per Treatment Group by CD16A Genotype (Sep 2019 Cutoff)

eFigure 4. Prespecified Exploratory PFS Subgroup Analyses (CBA) – Oct 2018 Cutoff

eFigure 5. Prespecified Exploratory OS Subgroup Analyses – Sep 2019 Cutoff

Data Sharing Statement