Abstract

Leukocytoclastic small-vessel vasculitis of the skin (with or without systemic involvement) is often preceded by infections such as common cold, tonsillopharyngitis, or otitis media. Our purpose was to document pediatric (≤18 years) cases preceded by a symptomatic disease caused by an atypical bacterial pathogen. We performed a literature search following the Preferred Reporting of Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines. We retained 19 reports including 22 cases (13 females and 9 males, 1.0 to 17, median 6.3 years of age) associated with a Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection. We did not find any case linked to Chlamydophila pneumoniae, Chlamydophila psittaci, Coxiella burnetii, Francisella tularensis, or Legionella pneumophila. Patients with a systemic vasculitis (N = 14) and with a skin-limited (N = 8) vasculitis did not significantly differ with respect to gender and age. The time to recovery was ≤12 weeks in all patients with this information. In conclusion, a cutaneous small-vessel vasculitis with or without systemic involvement may occur in childhood after an infection caused by the atypical bacterial pathogen Mycoplasma pneumoniae. The clinical picture and the course of cases preceded by recognized triggers and by this atypical pathogen are indistinguishable.

Keywords: leukocytoclastic small-vessel vasculitis, atypical pathogens, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Legionella pneumophila, Chlamydophila pneumoniae, Chlamydophila psittaci, Coxiella burnetii, Francisella tularensis

1. Introduction

Respiratory infections caused by so-called atypical bacterial pathogens such as Mycoplasma, Legionella, and, less frequently, Chlamydophila pneumoniae or psittaci, Coxiella burnetii and Francisella tularensis are often accompanied by non-respiratory immunologically mediated features, which may involve almost all organ systems [1,2,3].

Non-granulomatous leukocytoclastic small-vessel vasculitis of the skin with immune deposits, subsequently referred to as cutaneous small-vessel vasculitis, are often preceded by an acute upper-respiratory tract infection and may be limited to the skin or involve other tissues [4,5]. Textbooks and reviews no more than marginally mention the association with a symptomatic respiratory disease caused by atypical bacterial pathogens. Since this issue has never been extensively covered, we systematically reviewed the literature. The purpose was to document the clinical features and the course in pediatric patients with cutaneous small-vessel vasculitis preceded by the mentioned pathogens.

2. Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

We performed a structured literature search [6] with no language or date limits in August 2020 on the Excerpta Medica, National Library of Medicine, and Web of Science databases following the Preferred Reporting of Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines [7]. Search terms were (“atypical pneumonia” OR “Chlamydia pneumoniae” OR “Chlamydia psittaci” OR “Chlamydophila pneumoniae” OR “Chlamydophila psittaci” OR “Coxiella burnetii” OR “Francisella tularensis” OR “Legionella” OR “Mycoplasma pneumoniae”) AND (“acute hemorrhagic edema” OR “anaphylactoid purpura” OR “Finkelstein-Seidlmayer disease” OR “Henoch purpura” OR “leukocytoclastic vasculitis” OR “immunoglobulin A vasculitis” OR “urticarial vasculitis” OR “small vessel vasculitis” OR “vasculitis”). The literature search was carried out by two investigators with the support of an experienced senior investigator, who independently screened titles and abstracts of all reports in a nonblinded fashion to remove irrelevant reports. Discrepancies in study identification were resolved by consensus. Subsequently, full-text publications were reviewed to decide whether the report fitted the eligibility criteria of the review. The bibliography of each identified report was also screened for secondary references.

2.2. Selection Criteria

Original articles published up to July 31, 2020, that reported on pediatric (≤18 years) cases of community-acquired upper or lower respiratory-tract infections caused by Chlamydophila (Chlamydia) pneumoniae, Chlamydophila psittaci, Coxiella burnetii, Francisella tularensis, Legionella species, or Mycoplasma pneumoniae temporally associated (by ≤2 weeks) with a non-granulomatous leukocytoclastic small-vessel cutaneous vasculitis were sorted. Only previously healthy subjects without any pre-existing chronic disease were included. Cases of vasculitis possibly resulting from an adverse drug reaction and cases with detectable circulating anti-cytoplasmic or anti-nuclear auto-antibodies were excluded.

The diagnosis of infection caused by an atypical pathogen was retained exclusively in cases with both a distinctive clinical presentation and an appropriate [1,2] microbiology laboratory testing.

Recognized criteria were used to confirm or infirm the vasculitis diagnosis made in the original reports. The diagnosis of systemic immunoglobulin A [4] vasculitis was retained in subjects presenting with palpable purpura and at least one of the following: abdominal involvement (pain, vomiting, high frequency or fluidity of bowel movements, intestinal bleeding, and intussusception), articular involvement (joint pain with or without swelling), or kidney involvement (pathological hematuria, with or without associated pathological proteinuria). The diagnosis of acute hemorrhagic edema vasculitis was made in well-appearing infants and young children with acute onset of erythematous annular skin lesions and pronounced diffuse nonpitting body edema [4]. A biopsy was not a prerequisite for the diagnosis of immunoglobulin A vasculitis or acute hemorrhagic edema vasculitis [4]. The diagnosis of urticarial skin-limited vasculitis was suspected in patients presenting exclusively with wheals that persist for >24 h, burn more than itch, and often leave residual purpura as they resolve [5]. On the other hand, the diagnosis of “unclassified” skin-limited cutaneous vasculitis was suspected in subjects presenting with palpable purpura, usually localized on the buttocks and legs without any other organ system involvement [8]. A skin biopsy disclosing a non-granulomatous neutrophil infiltration into small vessel walls with karyorrhexis was a prerequisite for the final diagnosis of urticarial skin-limited vasculitis.

2.3. Data Extraction—Case Assessment—Comprehensiveness of Reporting

A predesigned data extraction form was used to collect the following information of each included case into a worksheet: demographics; clinical data, laboratory features and biopsy studies; immunomodulatory drug management; and outcome. If needed, attempts were also made to contact authors of original reports to provide missing information. The CAAR score (for Cutaneous, Abdominal, Articular and Renal involvement) is widely recommended (Table 1) to measure the disease severity in immunoglobulin A vasculitis [4]. For the present review, we employed the CAAR score also in patients affected by a skin-limited disease. Comprehensiveness of reporting was evaluated using four items: 1. description of respiratory disease and microbiologic testing; 2. description of vasculitis features; 3. drug management; 4. time to recovery. Each item was rated as 0, 1, or 2 and the reporting comprehensiveness was graded according to the sum of each item as high (score ≥ 6), satisfactory (score 4–5), or low (score ≤ 3).

Table 1.

CAAR-grading system.

| Organ’s involvement | |

|---|---|

| ● Cutaneous involvement | |

| |

| ● Abdominal involvement | |

| |

| ● Articular involvement | |

| |

| ● Renal involvement | |

| |

2.4. Data analysis

Categorical data are presented as frequency and were analyzed using the Fisher’s exact test. Continuous data are presented as median and interquartile range and were analyzed using the Mann–Whitney–Wilcoxon test [9,10]. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Search Results

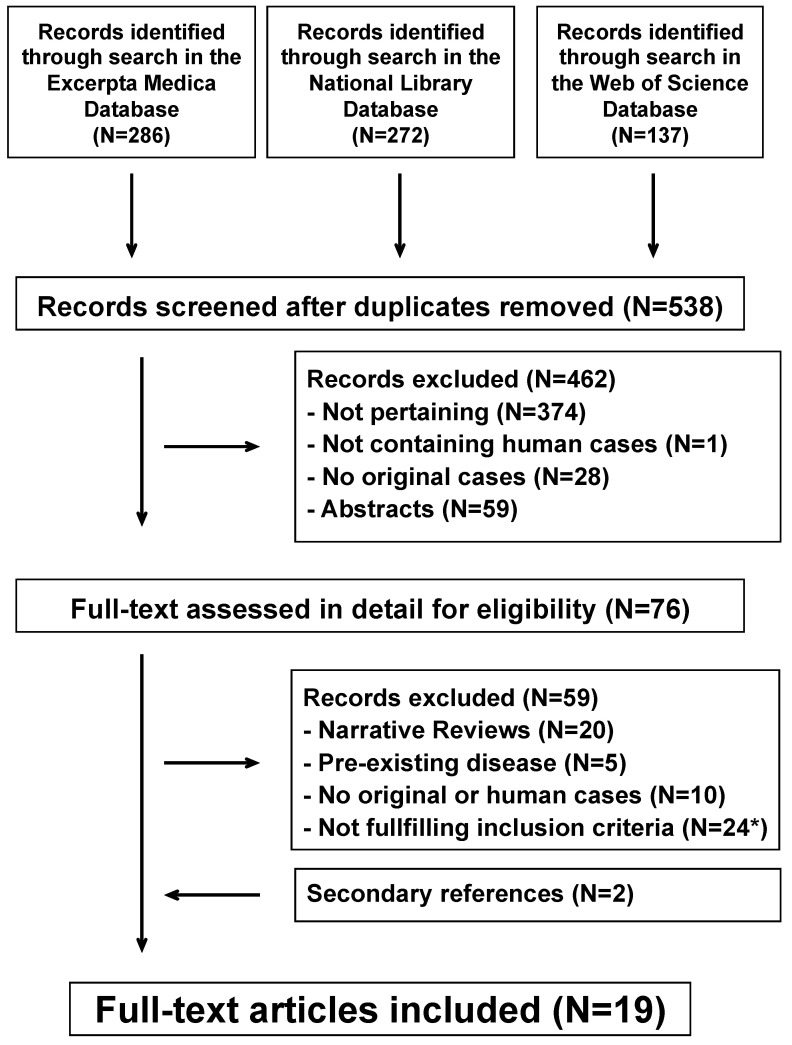

The systematic literature search returned 538 potentially relevant reports (Figure 1). After removing irrelevant reports, 76 full-text publications were reviewed for eligibility. For the final analysis, we retained 19 reports [11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29] including 22 cases, which were published after 1973 in English (N = 16) and Spanish (N = 3 ) from the following countries: Italy (N = 4), Japan (N = 3), Spain (N = 2), the United Kingdom (N = 2), France (N = 1), Belgium (N = 1), China (N = 1), Colombia (N = 1), the Czech Republic (N = 1), Greece (N = 1), Poland (N = 1), and South Korea (N = 1). All cases were temporally associated with a Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection. No cases were linked to Chlamydophila pneumoniae, Chlamydophila psittaci, Coxiella burnetii, Francisella tularensis, or Legionella pneumophila. Reporting comprehensiveness was high in 12, moderate in eight, and low in the remaining two cases.

Figure 1.

Small vessel leukocytoclastic vasculitis of the skin and atypical bacterial pathogens. Flowchart of the literature search process. *Including 10 adult cases (Mycoplasma pneumoniae, N = 7; Chlamydophila pneumoniae, N = 2; Legionella pneumophila, N = 1).

3.2. Microbiologic Diagnosis

The laboratory diagnosis of Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection was made by detecting a significant rise in antibody titer when comparing acute and convalescent blood samples (N = 20), a positive Mycoplasma testing in a respiratory tract sample (N = 1), or both (N = 1).

3.3. Findings

In the 22 patients (13 females and 9 males, 1.0 to 17, median 6.3 years of age), the vasculitis syndrome was systemic and skin-limited in two-thirds and one-third of cases, respectively (Table 2). Patients with systemic vasculitis (8 females and 6 males, 6.1 (4.3–8.0) years of age) and patients with an isolated cutaneous vasculitis (5 females and 3 males; 5.0 (2.4–12.3) years of age) did not significantly differ with respect to gender and age. The cutaneous involvement was significantly (P < 0.05) less relevant in subjects with systemic vasculitis (mild, N = 12; moderate, N = 2; severe, N = 0) as compared with those affected by a skin-limited vasculitis (mild, N = 2; moderate, N = 2; severe, N = 4). Biopsy studies were performed in eight cases, as shown in Table 3.

Table 2.

Characteristics of 22 patients, 1.0 to 17 years of age, affected by a cutaneous non-granulomatous leukocytoclastic small-vessel vasculitis with immune deposits preceded by a symptomatic respiratory disease caused by Mycoplasma pneumoniae.

| Heading | All Cases | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 22 | ||

| Females:Males, N | 13:9 | ||

| Age, years | |||

| years | 6.3 [3.1–9.0] | ||

| Respiratory disease | |||

| Upper respiratory disease, N | 13 | ||

| Lower respiratory disease, N | 9 | ||

| Classification of vasculitis | |||

| Systemic immunoglobulin A vasculitis, N | 14 | ||

| Skin-limited vasculitis | |||

| Acute hemorrhagic edema vasculitis, N | 3 | ||

| Urticarial vasculitis, N | 1 | ||

| Unclassified, N | 4 | ||

| Immunomodulatory drug treatment | |||

| Systemic corticosteroids | 6 | ||

| Dapsone | 1 | ||

Table 3.

Results of testing for deposits of immunoglobulin A into skin-vessel walls on patients affected by a cutaneous non-granulomatous leukocytoclastic small-vessel vasculitis.

| Immunoglobulin AcairuiVasculitis | Skin-limited Vasculitis | |||

| Acute Hemorrhagic Edema | Urticarial | Unclassified | ||

| Skin biopsy performed, N | 4 * | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Testing for immunoglobulin A performed, N | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Testing for immunoglobulin A positive, N | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

* Both a kidney and a skin biopsy were performed in 2 patients.

The characteristics of the 14 patients with systemic immunoglobulin A vasculitis are given in Table 4. No kidney involvement was noted in eight, no abdominal involvement in five, and no articular involvement in three patients. None of the patients with kidney involvement was found to have an elevated creatinine level.

Table 4.

Characteristics of 14 pediatric patients (9 girls and 5 boys, aged 1.5 to 17, median 6.1 years of age) affected by a systemic immunoglobulin A vasculitis. The CAAR grading system was used.

| Organ’s Involvement | N | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 14 | |||

| Cutaneous involvement | |||

| Mild | 12 | ||

| Moderate | 2 | ||

| Severe | 0 | ||

| Abdominal involvement | |||

| None | 5 | ||

| Mild | 3 | ||

| Moderate | 4 | ||

| Severe | 2 | ||

| Articular involvement | |||

| None | 3 | ||

| Mild | 1 | ||

| Moderate | 10 | ||

| Severe | 0 | ||

| Kidney involvement | |||

| None | 8 | ||

| Mild | 3 | ||

| Moderate | 1 | ||

| Severe | 2 | ||

| Immunomodulatory drug treatment | |||

| Systemic corticosteroids | 4 | ||

| Dapsone | 1 | ||

| Time to recovery | |||

| ≤4 weeks, N | 9 | ||

| 5–12 weeks, N | 4 | ||

| No information available, N | 1 | ||

Oral (N = 2) or parenteral (N = 2) corticosteroids were prescribed in four cases. Dapsone was administered to a 4.0-year-old boy. The time to recovery was ≤12 weeks in all cases with this information.

Two of the eight patients affected by a skin-limited vasculitis were prescribed oral corticosteroids. The time to recovery was ≤4 weeks in seven and 6 weeks in one of these cases. This parameter was not statistically different between patients with systemic and skin-limited vasculitis.

4. Discussion

This careful literature review points out that, in childhood, a symptomatic community-acquired respiratory disease caused by an atypical bacterial pathogen may be followed by a skin-limited or, more frequently, a systemic immunoglobulin A small-vessel vasculitis. All cases follow a Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection, affect more females than males, and have a good prognosis.

Vasculitis was associated exclusively with a Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection. We do not have any clear-cut explanation for this observation. We tentatively offer two causes. First, immunologically mediated complications such as hemolytic anemia, urticaria or erythema multiforme are more commonly linked to Mycoplasma pneumoniae compared to the remaining atypical bacterial pathogens [3,4]. Second, atypical bacterial pathogens such as Chlamydophila pneumoniae or psittaci, Coxiella burnetii and Francisella tularensis are not a frequent cause of a community-acquired acute respiratory disease in childhood [3,4].

As in the present analysis, immunoglobulin A small vessel vasculitis generally is a benign disease with an excellent prognosis, which affects all ages but occurs more frequently in children between 3 and 11 years [4]. In the mentioned vasculitis, there is normally a slight gender predilection affecting males rather than females at a 2:1 ratio [4], at variance with the data observed in the cases preceded by an atypical bacterial pathogen that were included in this review.

The prevalence of small-vessel vasculitis of the skin accompanying a symptomatic respiratory infection caused by an atypical bacterial pathogen is presently unknown. Seven case series including a total of 1618 patients affected by an immunoglobulin A vasculitis never described this association [30,31,32,33,34,35,36]. On the other hand, a recent report from China [37] including 1200 pediatric cases of immunoglobulin A vasculitis found serological evidence for a recent group A Streptococcus infection in 205 (17%) and for a Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection in 58 (4.8%) cases. We do not have any exhaustive explanation for the discrepancy between the Chinese data [37] and the results of the aforementioned case series [30,31,32,33,34,35,36]. We speculate that pediatricians customarily do not test for atypical bacterial pathogens in patients with vasculitis, even if preceded by a lower respiratory-tract infection [4].

The vast majority of children affected by a skin-limited or systemic immunoglobulin A small vessel vasculitis recover spontaneously and may be cared for as outpatients. Management is predominantly supportive and includes adequate hydration and symptomatic relief of pain [4]. There is some evidence that glucocorticoids enhance the rate of resolution of arthritis and especially abdominal pain [4]. However, these measures do not appear to prevent recurrent disease [4,38]. Medical treatment of active kidney disease, which is rarely required and is discussed in detail elsewhere [38], depends upon whether the patient is a child or an adult and upon the severity of proteinuria and histologic lesions (especially the degree of crescent formation). Finally, there is a widespread view that antimicrobials speed up the recovery of atypical pneumonia but do not shorten the course of mucocutaneous complications [1,3].

Immunoglobulin A1 deposition is a crucial pathophysiologic feature in immunoglobulin A vasculitis [4]. In clinical practice, a skin biopsy is rarely performed, especially in childhood, because the diagnosis is normally made on a clinical basis. Immunoglobulin A deposits were not found in one case included in this review. This is likely related to the fact that deposits may disappear with time due to phagocytosis and proteolysis. Unsurprisingly, therefore, skin biopsy (if indicated) should be performed at the edge of fresh lesions to maximize the chance of finding immune deposits [39,40].

The results of this systematic review must be viewed with an understanding of the inherent limitations of the analysis, which included data from articles published over more than 40 years. Furthermore, a temporal association between an infection caused by Mycoplasma pneumoniae and the vasculitis onset does not inevitably imply a causal relationship. Finally, the analysis did not address atypical pneumonias precipitated by viral pathogens including, among others, adenoviruses, influenzaviruses, parainfluenzaviruses, respiratory syncytial virus, and especially coronaviruses. Available data suggest an association of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 with small-vessel vasculitis of the skin [41].

5. Conclusions

Respiratory diseases caused by atypical bacterial pathogens are notoriously associated with urticaria, erythema multiforme and, more rarely, erythema nodosum or varicella-like eruptions [1,3,42]. This systematic review of the literature indicates that also a cutaneous small-vessel vasculitis may occur after an infection caused by the atypical bacterial pathogen Mycoplasma pneumoniae. The clinical picture and the course are similar to those observed in cases preceded by infections such as common cold, tonsillopharyngitis, or otitis media [30,31,32,33,34,35,36].

Author Contributions

C.B., M.G.B. and G.P.M. conceived and designed the study. P.C., V.G. and G.P.M. collected and analyzed the data. M.S., S.A.G.L., G.D.S. and A.F. drafted the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that no conflict of interest exists.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Johnson D.H., Cunha B.A. Atypical pneumonias. Clinical and extrapulmonary features of chlamydia, mycoplasma, and legionella infections. Postgrad. Med. 1993;93:69–82. doi: 10.1080/00325481.1993.11701702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Basarab M., Macrae M.B., Curtis C.M. Atypical pneumonia. Curr. Opin. Pulm. Med. 2014;20:247–251. doi: 10.1097/MCP.0000000000000048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Poddighe D. Extra-pulmonary diseases related to Mycoplasma pneumoniae in children: Recent insights into the pathogenesis. Curr. Opin. Rheumatol. 2018;30:380–387. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0000000000000494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lava S.A.G., Milani G.P., Fossali E.F., Simonetti G.D., Agostoni C., Bianchetti M.G. Cutaneous manifestations of small-vessel leukocytoclastic vasculitides in childhood. Clin. Rev. Allergy Immunol. 2017;53:439–451. doi: 10.1007/s12016-017-8626-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sunderkötter C.H., Zelger B., Chen K.R., Requena L., Piette W., Carlson J.A., Dutz J., Lamprecht P., Mahr A., Aberer E., et al. Nomenclature of cutaneous vasculitis: Dermatologic addendum to the 2012 revised international chapel hill consensus conference nomenclature of vasculitides. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2018;70:171–184. doi: 10.1002/art.40375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Krupski T.L., Dahm P., Fesperman S.F., Schardt C.M. How to perform a literature search. J. Urol. 2008;179:1264–1270. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.11.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liberati A., Altman D.G., Tetzlaff J., Mulrow C., Gøtzsche P.C., Ioannidis J.P., Clarke M., Devereaux P.J., Kleijnen J., Moher D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: Explanation and elaboration. Ann. Intern. Med. 2009;151:W65–W94. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fiorentino D.F. Cutaneous vasculitis. J. Am. Acad. Derm. 2003;48:311–340. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2003.212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moses L.E., Emerson J.D., Hosseini H. Analyzing data from ordered categories. N. Engl. J. Med. 1984;311:442–448. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198408163110705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brown G.W., Hayden G.F. Nonparametric methods. Clinical applications. Clin. Pediatrics. 1985;24:490–498. doi: 10.1177/000992288502400905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liew S.W., Kessel I. Mycoplasmal pneumonia preceding Henoch-Schönlein purpura. Arch. Dis. Child. 1974;49:912–913. doi: 10.1136/adc.49.11.912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Steare S.E., Wiselka M.J., Kurinczuk J.J., Nicholson K.G. Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection associated with Henoch-Schönlein purpura. J. Infect. 1988;16:305–307. doi: 10.1016/S0163-4453(88)97796-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Van Bever H.P., Van Doorn J.W., Demey H.E. Adult respiratory distress syndrome associated with Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection. Eur. J. Pediatrics. 1992;151:227–228. doi: 10.1007/BF01954392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaneko K., Fujinaga S., Ohtomo Y., Nagaoka R., Obinata K., Yamashiro Y. Mycoplasma pneumoniae-associated Henoch-Schönlein purpura nephritis. Pediatr Nephrol. 1999;13:1000–1001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gómez Campderá J.A., Rodríguez A., Navarro M.L., Rodríguez R., Dobón P., Sanz E., Roncero M. Neumonía, eritema nodoso y púrpura de Schöenlein Henoch, secundarias a infección por Mycoplasma pneumoniae. Acta Pediatrica Esp. 2001;59:654–656. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Orlandini V., Dega H., Dubertret L. Vascularite cutanée révélant une infection à Mycoplasma pneumoniae. Presse Méd. 2004;33:1365–1366. doi: 10.1016/S0755-4982(04)98934-8. (in French) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Timitilli A., Di Rocco M., Nattero G., Tacchella A., Giacchino R. Unusual manifestations of infections due to Mycoplasma pneumoniae in children. Infez. Med. 2004;12:113–117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Roh M.R., Chung H.J., Lee J.H. A case of acute hemorrhagic edema of infancy. Yonsei Med. J. 2004;45:523–526. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2004.45.3.523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gómez-Campderá J.A., Riofrío R.A., Navarro Gómez M.I., Sanz López E., Dobón Westphal P., Rodríguez Fernández R. Manifestaciones dermatológicas de la infección por Mycoplasma pneumoniae. Acta Pediatrica Esp. 2006;64:446–452. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Greco F., Sorge A., Salvo V., Sorge G. Cutaneous vasculitis associated with Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection: Case report and literature review. Clin. Pediatrics. 2007;46:451–453. doi: 10.1177/0009922806298638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kano Y., Mitsuyama Y., Hirahara K., Shiohara T. Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection-induced erythema nodosum, anaphylactoid purpura, and acute urticaria in 3 people in a single family. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2007;57(Suppl. 2):S33–S35. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2005.08.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shimizu M., Hamaguchi Y., Matsushita T., Sakakibara Y., Yachie A. Sequentially appearing erythema nodosum, erythema multiforme and Henoch-Schönlein purpura in a patient with Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection: A case report. J. Med. Case Rep. 2012;6:398. doi: 10.1186/1752-1947-6-398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yiallouros P., Moustaki M., Voutsioti A., Sharifi F., Karpathios T. Association of mycoplasma pneumoniae infection with Henoch-Schönlein purpura. Prague Med. Rep. 2013;114:177–179. doi: 10.14712/23362936.2014.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Di Lernia V. Mycoplasma pneumoniae: An aetiological agent of acute haemorrhagic oedema of infancy. Australas J. Dermatol. 2014;55:e69–e70. doi: 10.1111/ajd.12047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hu P., Guan Y., Lu L. Henoch-Schönlein purpura triggered by Mycoplasma pneumoniae in a female infant. Kaohsiung J. Med. Sci. 2015;31:163–164. doi: 10.1016/j.kjms.2014.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kuźma-Mroczkowska E., Pańczyk-Tomaszewska M., Szmigielska A., Szymanik-Grzelak H., Roszkowska-Blaim M. Mycoplasma pneumoniae as a trigger for Henoch-Schönlein purpura in children. Cent. Eur. J. Immunol. 2015;40:489–492. doi: 10.5114/ceji.2015.56976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Diplomatico M., Gicchino M.F., Ametrano O., Marzuillo P., Olivieri A.N. A case of urticarial vasculitis in a female patient with lupus: Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection or lupus reactivation? Rheumatol. Int. 2017;37:837–840. doi: 10.1007/s00296-016-3626-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Consuegra-Solano J., Agualimpia-Palacios L.C., Cadavid-Zapata K.L., Kury-Palacios S.Y., Sánchez I.P. Edema agudo hemorrágico de la infancia. CES Med. 2017;31:192–198. doi: 10.21615/cesmedicina.31.2.8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Volejnikova J., Horacek J., Kopriva F. Dapsone treatment is efficient against persistent cutaneous and gastrointestinal symptoms in children with Henoch-Schönlein purpura. Biomed. Pap. Med. Fac. Univ. Palacky Olomouc Czech. Repub. 2018;162:154–158. doi: 10.5507/bp.2017.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Balmelli C., Laux-End R., Di Rocco D., Carvajal-Busslinger M.I., Bianchetti M.G. Purpura Schönlein-Henoch: Verlauf bei 139 Kindern. Schweiz. Med. Wochenschr. 1996;126:293–298. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nussinovitch M., Prais D., Finkelstein Y., Varsano I. Cutaneous manifestations of Henoch-Schönlein purpura in young children. Pediatric Derm. 1998;15:426–428. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1470.1998.1998015426.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Saulsbury F.T. Henoch-Schönlein purpura in children. Report of 100 patients and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltim.) 1999;78:395–409. doi: 10.1097/00005792-199911000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Trapani S., Micheli A., Grisolia F., Resti M., Chiappini E., Falcini F., De Martino M. Henoch Schonlein purpura in childhood: Epidemiological and clinical analysis of 150 cases over a 5-year period and review of literature. Semin. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;35:143–153. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2005.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vila Cots J., Giménez Llort A., Camacho Díaz J.A., Vila Santandreu A. Nefropatía en la púrpura de Schönlein-Henoch: Estudio retrospectivo de los últimos 25 años. Pediatria (Barc.) 2007;66:290–293. doi: 10.1157/13099692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Peru H., Soylemezoglu O., Bakkaloglu S.A., Elmas S., Bozkaya D., Elmaci A.M., Kara F., Buyan N., Hasanoglu E. Henoch Schönlein purpura in childhood: Clinical analysis of 254 cases over a 3-year period. Clin. Rheumatol. 2008;27:1087–1092. doi: 10.1007/s10067-008-0868-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Watson L., Richardson A.R., Holt R.C., Jones C.A., Beresford M.W. Henoch-Schönlein purpura—A 5-year review and proposed pathway. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e29512. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0029512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang J.J., Xu Y., Liu F.F., Wu Y., Samadli S., Wu Y.F., Luo H.H., Zhang D.D., Hu P. Association of the infectious triggers with childhood Henoch-Schönlein purpura in Anhui province, China. J. Infect. Public Health. 2020;13:110–117. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2019.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.KDIGO Group KDIGO clinical practice guidelines for glomerulonephritis. Chapter 11: Henoch-Schönlein purpura nephritis. Kidney Int. Suppl. (2011) 2012;2:218–220. doi: 10.1038/kisup.2012.24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Davin J.C., Weening J.J. Diagnosis of Henoch-Schönlein purpura: Renal or skin biopsy? Pediatric Nephrol. 2003;18:1201–1203. doi: 10.1007/s00467-003-1292-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lath K., Chatterjee D., Saikia U.N., Saikia B., Minz R., De D., Handa S., Radotra B. Role of direct immunofluorescence in cutaneous small-vessel vasculitis: Experience from a tertiary center. Am. J. Derm. 2018;40:661–666. doi: 10.1097/DAD.0000000000001170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Marzano A.V., Cassano N., Genovese G., Moltrasio C., Vena G.A. Cutaneous manifestations in patients with COVID-19: A preliminary review of an emerging issue. Br. J. Derm. 2020;183:431–442. doi: 10.1111/bjd.19264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Terraneo L., Lava S.A., Camozzi P., Zgraggen L., Simonetti G.D., Bianchetti M.G., Milani G.P. Unusual eruptions associated with mycoplasma pneumoniae respiratory infections: Review of the literature. Dermatology. 2015;231:152–157. doi: 10.1159/000430809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]