Abstract

Background

While peritoneal dialysis (PD) can offer patients more independence and flexibility compared with in-center hemodialysis, managing the ongoing and technically demanding regimen can impose a burden on patients and caregivers. Patient empowerment can strengthen capacity for self-management and improve treatment outcomes. We aimed to describe patients’ and caregivers’ perspectives on the meaning and role of patient empowerment in PD.

Methods

Adult patients receiving PD (n = 81) and their caregivers (n = 45), purposively sampled from nine dialysis units in Australia, Hong Kong and the USA, participated in 14 focus groups. Transcripts were thematically analyzed.

Results

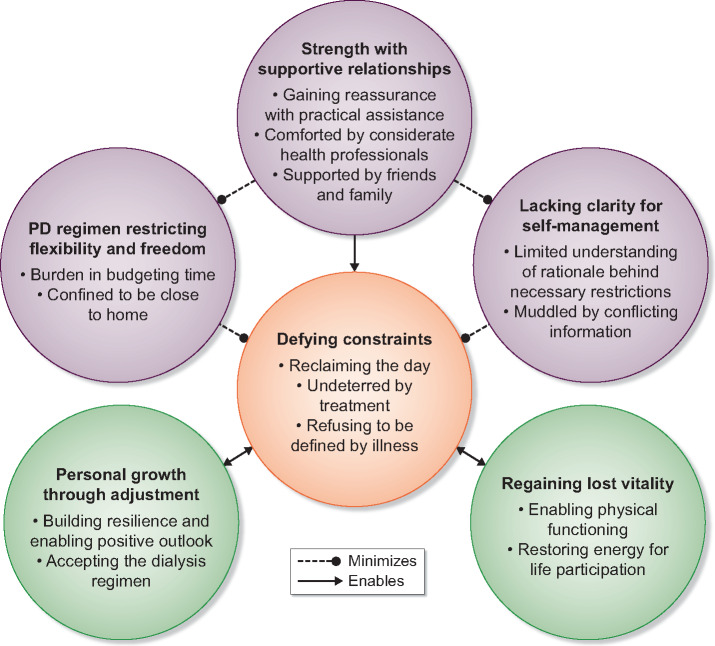

We identified six themes: lacking clarity for self-management (limited understanding of rationale behind necessary restrictions, muddled by conflicting information); PD regimen restricting flexibility and freedom (burden in budgeting time, confined to be close to home); strength with supportive relationships (gaining reassurance with practical assistance, comforted by considerate health professionals, supported by family and friends); defying constraints (reclaiming the day, undeterred by treatment, refusing to be defined by illness); regaining lost vitality (enabling physical functioning, restoring energy for life participation); and personal growth through adjustment (building resilience and enabling positive outlook, accepting the dialysis regimen).

Conclusions

Understanding the rationale behind lifestyle restrictions, practical assistance and family support in managing PD promoted patient empowerment, whereas being constrained in time and capacity for life participation outside the home undermined it. Education, counseling and strategies to minimize the disruption and burden of PD may enhance satisfaction and outcomes in patients requiring PD.

Keywords: chronic kidney disease, patient empowerment, peritoneal dialysis, quality of life

KEY LEARNING POINTS

What is already known about this subject?

Given the active role of patients receiving peritoneal dialysis (PD) in their daily responsibilities for the treatment, managing the technically demanding regimen can impose a burden on patients and caregivers.

Patient empowerment, defined as a process that enables patients to gain greater control over their health and lives, can strengthen capacity for self-management and improve treatment outcomes.

However, little is known about the meaning and role of patient empowerment from the perspectives of patients treated with PD.

What this study adds?

Lack of understanding of the clinical rationale behind lifestyle restrictions, receiving conflicting advice, being restrained in time and capacity for meaningful and necessary life activities outside the home setting constrained patients’ control over lifestyle and undermined their feelings of empowerment.

Regular practical training and the support of family and clinicians in managing PD enabled and equipped patients to problem-solve and manage the PD regimen, accept and routinize PD into daily living, and disentangle their personal identity from their treatment and chronic kidney disease.

What impact this may have on practice or policy?

Education which increases patients’ overall health literacy and knowledge of PD self-management would encourage more informed and shared decision-making, particularly when concerning decisions around potential regimen restrictions on patients’ meaningful and necessary life activities.

Clinicians can support patients in developing and improving skills in doing PD, beyond the initial training period, and help build the confidence and ability of patients to problem-solve, for example if they encounter technical complications.

By prioritizing the flexibility of PD regimen schedules and providing patients with practical strategies enabling them to dialyze safely outside the home setting, clinicians can help patients to effectively manage and integrate PD around their daily tasks and priorities and enhance treatment outcomes and satisfaction.

INTRODUCTION

Peritoneal dialysis (PD) can offer patients with end-stage kidney disease increased flexibility, independence and freedom compared with in-center hemodialysis (HD) [1–3]. While all patients undergo training when first commencing PD, the regimen can be demanding as patients must manage the ongoing daily technical responsibility of PD, and remain constantly vigilant in minimizing the risk of complications, such as infection [4]. The treatment burden of PD can disrupt patients’ lifestyles and impair their quality of life, treatment satisfaction and outcomes [5].

Given the active role of patients receiving PD in their daily responsibilities for the treatment, greater emphasis on a strengths-based approach is warranted. This approach identifies and cultivates the individual’s attributes to maintain control, build resilience and strengthen capacity for self-management [6]. One specific attribute is patient empowerment, defined as a process that enables patients to gain greater control over their health and lives, and involves building the knowledge and skills necessary for person-centered care [7–9].

In chronic kidney disease (CKD), interventions targeting patient empowerment have improved quality of life in predialysis patients [10], medication adherence in transplant recipients [11], and blood pressure, quality of life and interdialytic weight gain in patients on HD [12–15]. However, little is known about the meaning and role of empowerment from the perspectives of patients treated with PD. This study aimed to describe patients’ and caregivers’ perceptions, attitudes and experiences of patient empowerment in managing PD and to inform ways to strengthen support for patients receiving PD, thereby helping to improve their outcomes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This focus group study was conducted as part of the Standardized Outcomes in Nephrology-Peritoneal Dialysis Initiative [16]. The data used and reported in this study were focused on patient empowerment in the management of PD. We used the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research to report this study [17].

Participant selection and recruitment

Patients and caregivers were recruited from nine dialysis units in Australia (Sydney, Melbourne and Brisbane), Hong Kong (Hong Kong) and the USA (Los Angeles). Participants were eligible if they were ≥18 years, able to give informed consent and English-speaking (or Spanish-speaking in the USA). Purposive sampling was used to include a diverse sample with a wide range of demographic (e.g. age, sex) and clinical characteristics [e.g. PD modality including continuous ambulatory PD (CAPD), automated PD (APD), dialysis vintage, complications] that were relevant to the research question. We monitored participant characteristics during data collection and targeted recruitment to ensure that we captured all the relevant demographic and clinical characteristics as was possible. Participants received a reimbursement equivalent to $50 US in the local currency for travel expenses. Ethics approvals were obtained from the ethics committees of each of the participating sites.

Data collection

Two-hour focus groups were conducted from March to September 2017. One investigator (K.E.M. or A.T.-P.) facilitated the groups, which were held in meeting rooms external to the hospital, while a second investigator (K.E.M. or A.T.-P.) recorded field notes on group dynamics and interactions during the session. The question guide is provided in Supplementary data, Table S1. Groups were convened until data saturation occurred and all were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Data analysis

All transcripts were entered into HyperRESEARCH software (version 4.0.1). Using thematic analysis and some principles from grounded theory [18], A.B. inductively coded the transcripts line by line to generate codes from the data and identify concepts related to participants’ attitudes, beliefs and experiences of empowerment in managing PD. Similar concepts were grouped into themes and subthemes. The themes were discussed and revised with feedback from A.T.-P., K.E.M., J.I.S. and Y.C., who ensured the full range and breadth of the data had been captured with researcher triangulation. We developed a thematic schema to demonstrate the conceptual links among themes (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Thematic schema. Some patients felt that inconsistent and limited insight into the clinical rationale behind necessary restrictions and being constrained in time and capacity for life participation by PD were threats to freedom and empowerment. However, these impacts were minimized by practical and emotional support of their health professionals, family and friends, which helped facilitate empowered self-management. Some patients adapted the PD regimens around life priorities and learned to accept the treatment. Experiencing restored energy attributed to PD helped them participate in meaningful and necessary life activities.

RESULTS

Participant characteristics

In total, 81 patients and 45 caregivers participated across the 14 focus groups (Table 1), with each group consisting of 6–12 participants. Thirteen groups were conducted in English language and one group was conducted in Spanish language. Participants’ ages ranged from 18 to 84 years (mean 54; SD 15) and 63 (50%) were female. Of the patients, 35 (47%) were on CAPD, 40 (53%) were on APD and most (78%) had been receiving PD for <4 years. Of the caregivers, 29 (64%) were spouses, 6 (13%) were parents, 6 (13%) were siblings, 2 (5%) were children and 2 (5%) were other family members.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics (n = 126)

| Characteristics | Australia, n = 64 | USA n = 30 | Hong Kong, n = 32 | All, n = 126 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient | 40 (62) | 18 (60) | 23 (72) | 81 (64) |

| Caregiver/family member | 24 (38) | 12 (40) | 9 (28) | 45 (36) |

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 27 (42) | 20 (67) | 16 (50) | 63 (50) |

| Male | 37 (58) | 10 (33) | 16 (50) | 63 (50) |

| Age, years | ||||

| 18–39 | 10 (16) | 11 (38) | 3 (9) | 24 (19) |

| 40–59 | 25 (39) | 14 (48) | 16 (50) | 55 (44) |

| 60–79 | 27 (42) | 4 (14) | 13 (41) | 44 (35) |

| 80–89 | 2 (3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (2) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| Asian | 11 (17) | 1 (3) | 29 (91) | 41 (33) |

| White | 32 (50) | 1 (3) | 1 (3) | 34 (27) |

| Hispanic/Latino | 1 (2) | 18 (60) | 0 (0) | 19 (15) |

| African American | 0 (0) | 8 (27) | 0 (0) | 8 (6) |

| Othera | 20 (31) | 2 (7) | 2 (6) | 24 (19) |

| Highest level of education | ||||

| University degree | 16 (26) | 12 (43) | 15 (47) | 43 (35) |

| Diploma/certificate | 21 (34) | 0 (0) | 2 (6) | 23 (19) |

| Secondary school: Year 12 | 10 (16) | 7 (25) | 11 (34) | 28 (23) |

| Secondary school: Year 10 | 14 (22) | 5 (18) | 4 (13) | 23 (19) |

| Primary school | 1 (2) | 4 (14) | 0 (0) | 5 (4) |

| Employment status | ||||

| Retired/pensioner | 29 (46) | 3 (10) | 13 (41) | 45 (36) |

| Not employed | 13 (20) | 13 (43) | 4 (12) | 30 (24) |

| Full time | 11 (17) | 4 (13) | 8 (25) | 23 (18) |

| Part time/casual | 9 (14) | 5 (17) | 6 (19) | 20 (16) |

| Otherb | 2 (3) | 5 (17) | 1 (3) | 8 (6) |

| Marital status | ||||

| Married/partner | 46 (73) | 15 (53) | 24 (75) | 85 (69) |

| Single | 9 (14) | 8 (29) | 6 (19) | 23 (19) |

| Divorced/separated | 6 (10) | 3 (11) | 0 (0) | 9 (7) |

| Widowed | 2 (3) | 2 (7) | 2 (6) | 6 (5) |

| Type of PDc | ||||

| CAPD | 16 (44) | 10 (62) | 14 (61) | 50 (53) |

| APD | 20 (56) | 6 (38) | 9 (39) | 35 (47) |

| Time on PD,c years | ||||

| <1 | 13 (34) | 1 (6) | 7 (30) | 21 (27) |

| 1–3 | 22 (58) | 7 (44) | 10 (44) | 39 (51) |

| 4–6 | 2 (5) | 6 (38) | 5 (22) | 13 (17) |

| 7–10 | 1 (3) | 2 (12) | 1 (4) | 4 (5) |

| Prior renal replacement therapyc | ||||

| In-center HD | 4 (10) | 7 (41) | 2 (9) | 13 (17) |

| Home HD | 4 (10) | 3 (18) | 2 (9) | 9 (12) |

| Kidney transplant (living donor) | 4 (10) | 1 (6) | 0 (0) | 5 (6) |

| Kidney transplant (deceased donor) | 1 (3) | 1 (6) | 1 (5) | 3 (4) |

| Multiple (HD and transplant) | 1 (3) | 1 (6) | 1 (5) | 3 (4) |

| None | 25 (64) | 4 (23) | 16 (72) | 45 (57) |

Values are given as n (%). Numbers may not total (n = 64, n = 30, n = 32, N = 126) due to nonresponse.

Includes European, Indian, Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander, Middle Eastern, Pacific Islander and mixed ethnicities.

Includes volunteers, students, self-employed and unspecified.

For patients only. Numbers may not total (n = 40, n = 18, n = 23, n = 81) due to nonresponse.

Themes

We identified six themes: lacking clarity for self-management, PD regimen restricting flexibility and freedom, strength with supportive relationships, defying constraints, regaining lost vitality and personal growth through adjustment. The following section describes the respective subthemes with supporting quotations for each subtheme presented in Table 2. A thematic schema depicting the relationships between the subthemes is provided in Figure 1.

Table 2.

Selected illustrative quotations

| Theme | Quotations |

|---|---|

| Lacking clarity for self-management | |

| Limited understanding of rationale behind necessary restrictions |

Educate us on the drugs, also. Because there are different drugs. She might take a different drug than I do, and that drug is working for her, so I can say it to my doctor, and ask them, what do you think about me taking this drug instead of the drug that I’m already on? (F, patient, 40s, APD, Los Angeles) I want to know the physics, the mechanics behind why it’s going to damage this, and if I’m going to get hurt … that’s what I need to know. So then I understand. Not just tell me ‘you can’t do that’. Why? (M, patient, 50s, APD, Sydney) |

| Muddled by conflicting information |

The dietitian for my kidney says you can’t do this and you can’t do that, and I say hang on, I’m a diabetic. I say this and you say that, which is right and which is wrong? So it’s confusing, I mean, one dietitian says you do this, another one says that, and they conflict. (M, patient, 70s, CAPD, Brisbane) But you get conflicting advice, like [other patient] was saying, banana is bad for you, but my doctor says take more banana, because of the potassium. So, I’d like a better guideline of how much of these to take. (F, patient, 60s, CAPD, Sydney) |

| Restricted flexibility and freedom in doing dialysis regimen | |

| Burden in budgeting time |

Before, I can go out whenever I want. But now I have to schedule every day. The only thing is that I have no time anymore for everything. Every time must be budgeted. (F, patient, 70s, CAPD, Hong Kong) It’s a real pain in the arse to have to stop everything and go and sit down for twenty minutes and do the bag and empty the bag and cut up the box and you think I’ve got better things to do. (M, patient, 50s, CAPD, Brisbane) |

| Confined to be close to home |

The only problem is that I want to plan some vacations far away. I’m not that free to move far away to another state or another country for vacations. For me that’s the biggest thing. (M, patient, 30s, APD, Los Angeles) I was working. I’ve been working for how many years? And just for two years I am not working, so it could be affecting me, staying home, seeing everybody going, working, and I’m at home and staying there doing my dialysis and things like that … It’s like you have to stay home, you have to do this. (F, patient, 30s, APD, Sydney) |

| Strength with supportive relationships | |

| Gaining reassurance with practical assistance |

When I first started, as soon as something little would go wrong I’d ring them straight away … I’m like ‘oh my God, what do I do now?’ I felt really bad, but they were lovely about it. (F, patient, 30s, APD, Brisbane) I made the trip with no hassle whatsoever. The people in the center, they have got lots of tricks up their sleeve, like you know, when you’re doing travelling you find yourself in all sorts of situations. Doing an exchange may be something you need to take care of, but the setting is not something that you can choose, so they gave me a couple of tricks up my sleeve. (M, patient, 50s, APD, Melbourne) |

| Comforted by considerate health professionals |

What’s important to me is the relationship with the PD unit, like all the nurses are really compassionate and really get to know me. They sort of help me along through the journey. (F, patient, 30s, APD, Brisbane) I found her very helpful, and we discussed a number of options and really went through it. That eased me into it, because I guess we were all a little bit worried about it. (M, patient, 70s, CAPD, Brisbane) |

| Supported by family and friends | Realizing that you have to do it yourself, like when you’re not feeling well and then you have to take on all this information, and remember all these things and all these steps, and it can be a bit overwhelming. Just having all that information put on you. The good thing was that he came in with me and seeing how it was done, I think you were there too, yeah. It was good to have them there as well so that I didn’t feel like I was doing it alone. (F, patient, 30s, APD, Brisbane) So they know I have to be back home or I can’t stay out, if I’m going somewhere in the morning or whatever. So they all work with me, and everybody is just like, it is what it is. (F, patient, 40s, CAPD, Los Angeles) |

| Defying constraints | |

| Reclaiming the day |

Since you’re sleeping while your machine is on at night—I do the automated—I’m done as soon as I wake up, and make sure the hours are taken care of. Then I’m free to go about my day just like I regularly did before. So there’s really no change in my activities during the day, basically. (F, patient, 60s, APD, Los Angeles) In day time he’s just like a normal person and does anything he likes. (F, caregiver, 50s, Hong Kong) |

| Undeterred by treatment |

Well, I’m starting to get back into life. It restricted me for a while, but I’ve gotten used to carrying around a bag and a knapsack, and I just go off and do whatever I got to do, so I’m getting, getting mobilized again. (M, patient, 70s, CAPD, Brisbane) We try not to let the dialysis control us, you know. I say forget about the time, you do it whenever, as a family together we go out, but we come back up on the time. We don’t lose the time, but we just, six hours away from the machine, and in that time, that is where we find to put what we want to do as a family. (F, caregiver, 50s, Sydney) |

| Refusing to be defined by illness |

Most people don’t even know I’m on dialysis unless I tell them. Because I don’t feel like it’s a big deal to me. (F, patient, 40s, CAPD, Los Angeles) When I’m doing PD I don’t feel like I’m being a patient, I’m doing it at home. I made it such that even at home, it doesn’t look like a hospital, you know. I just put my boxes into my garage. (M, patient, 50s, APD, Melbourne) |

| Regaining lost vitality | |

| Enabling physical functioning |

It’s good that I had this procedure. With this I will admit feeling good. I can eat better now. Before I lost my appetite; I cannot eat, I became very thin. I lost my weight … I cannot walk … I feel so bad … I feel so tired. But now it’s okay. I walk. (F, patient, 70s, CAPD, Hong Kong) First of all I thank God and the doctors. I had been swollen for about three years, I couldn’t walk, and I ended in the hospital and I thank God again and the doctors that are helping me and I feel fine now. [translated] (M, patient, 40s, CAPD, Los Angeles) |

| Restoring energy for life participation |

Since she’s been on dialysis, at least it’s given her a bit of pep in her step again nowadays. I can see, from my point of view, she was going downhill rapidly until the diagnosis. At least now we can get out and enjoy the grandkids. (M, caregiver, 70s, Melbourne) To me dialysis is like a second opportunity. My happiness is that my children took me to the little cars last weekend. We went and I could enjoy my children and my granddaughter … I had a great time, I enjoyed like a little child, like if I was reborn. [translated] (F, patient, 40s, APD, Los Angeles) |

| Personal growth through adjustment | |

| Building resilience and enabling positive outlook |

As crazy as it may sound, I feel like being on dialysis really pushed me more in life, of becoming independent. Though dealing with my personal issues, my self-issues, it really helped me. It made me see life better by being on dialysis, it’s crazy but that’s how it made me. (F, patient, 20s, CAPD, Los Angeles) PD really hasn’t changed my life, or it has, it’s made me happier, because I’ve made decisions because of it, because I didn’t want to die. With the lifestyle I had when I got diagnosed and started, I thought oh sh*t I’m dying. If I’m going to die, I’m not going to die of this here, I’m not going to die doing this, I’m going to do this, I’m going to do this before I die. (F, patient, 50s, CAPD, Melbourne) |

| Accepting the dialysis regimen |

The hardest is acceptance … I used to think that I wasn’t going to do dialysis. I didn’t want to do that. ‘Why would I want a life where I’m going to be slave to a machine?’ I had to be in treatment to accept that it is life changing. I think we all should go through that. [translated] (M, patient, 30s, CAPD, Los Angeles) I guess the senses came back, you know? Senses came back, and I realized that PD is, you know, to me, now my attitude is different. My attitude is like, I’m doing PD is just like taking pills in the morning. It’s just another set of pills, so I just take it. (M, patient, 50s, APD, Melbourne) |

Lacking clarity for self-management

Limited understanding of rationale behind necessary restrictions

Some participants were uncertain about the rationale for the frequency and constant need to do PD. They wanted more ‘education about the toxicity in our body’ and its effects on their health if they missed a PD exchange. They felt clinicians should explain the reason when introducing changes to their PD regimen (such as adding another daily exchange) and how it would improve their health, particularly if it restricts their lifestyle and reduces their time off from dialysis. Others felt frustrated when advised by their clinicians to refrain from exercise and playing sports, and wanted to know ‘why’ instead of just being told ‘you can’t do that’. Some patients wanted more information about different medication options so they could be more actively involved in decision-making.

Muddled by conflicting information

Some patients with comorbidities struggled with multiple and, sometimes, conflicting recommendations from different specialists. For example, a patient found it ‘confusing’ when the dietitian introduced food restrictions that conflicted with advice from their endocrinologist. Another patient reported that a nurse gave different instructions than the doctor about how much fluid to remove during PD and felt perplexed. Some patients also felt unsure when they heard that other patients had received different advice (e.g. consumption of bananas) to what they had been given.

PD regimen restricting flexibility and freedom

Burden in budgeting time

Some patients described feeling weary and deprived of time in having to structure their lives around PD. For some, the ongoing nature of PD meant they could not ‘just go out and not think about the time’ and ‘every time must be budgeted’. They always had to ‘backward plan’ before considering social commitments to account for the PD preparation, dialysis and cleanup. Particularly for those on CAPD, the regimen was ‘fully encompassing’ and meant that they had to stop activities ‘halfway’, including social outings, or had to leave work during the day to do PD. Some patients who switched from CAPD to APD indicated they became less worried about time and experienced fewer interruptions.

Confined to be close to home

Some patients felt that the PD regimen was inflexible and meant they were unable to leave the house for an extended period of time. Since they could not ‘go away from home too far, too long’ and could only ‘go as far as four hours and then come back’, some felt confined to their home and this inability to travel was considered by younger patients in particular as the ‘biggest thing’. For some female patients and caregivers, it was particularly distressing as they were ‘staying home, seeing everybody going, working’ and described it as ‘like living in a cage house’.

Strength with supportive relationships

Gaining reassurance with practical assistance

Some patients who believed they received comprehensive and sustained practical training in PD by health professionals felt more prepared and able to prevent infection and manage complications. Some patients had nurses set up their PD equipment at home and felt reassured if they were able to immediately contact a nurse by telephone when they encountered a problem at home, for example when they ‘run out’ of bags. Particularly for some patients on CAPD, regular training enabled them to become ‘very comfortable’ with following their PD regimen as necessary and to feel equipped with ‘tricks’ and contingency plans for ‘emergency situations’.

Comforted by considerate health professionals

Feeling acknowledged and supported by health professionals who inquired into their well-being helped patients raise and discuss their problems with PD. For some patients, this support helped them become comfortable and confident in doing their PD alone at home, and they would leave the dialysis unit believing ‘everything is going to be good’.

Supported by family and friends

Having family members who were actively involved in managing PD provided some relief for patients. Their assistance with tasks, such as reminders to take medications or preparing dialysis bags, helped some patients feel less ‘alone’ when dialyzing. Patients with friends who were mindful of the demands of PD and adapted social activities around their dialysis schedule enabled them to maintain social participation.

Defying constraints

Reclaiming the day

Patients on APD expressed that they had greater control during the day compared with patients on CAPD. With the whole day ‘free’, patients felt they were able to successfully ‘do the dialysis and do your life as well’. This dialysis-free time allowed patients more freedom to ‘have a life’ and engage in meaningful activities during the day such as socializing with others and working. This led some patients to feel ‘just like a normal person’ in the day time.

Undeterred by treatment

Some patients and caregivers indicated they refused to let their dialysis ‘control’ or ‘stop’ them from engaging in activities in which they wanted to participate. These included playing sports, socializing with friends and travelling. Some used strategies to dialyze outside the home (e.g. car) or adjusted their dialysis times around their own schedule. One patient explained, ‘I did bags in airport toilets, I did bags in cars, I did bags whilst travelling between customs check through’.

Refusing to be defined by illness

Some patients, particularly in Australia and the USA, felt ‘normal’ and not like a ‘patient’, and did not want CKD or PD to encroach on their identity. Some said that their friends and family were not aware of their dialysis and that they ‘don’t have to know’. A caregiver also reiterated that patients should remember that ‘you’re not just your illness’.

Regaining lost vitality

Enabling physical functioning

For some older patients, the health gains from commencing PD enabled them to participate in more physical activities than before. Several patients who had previously been unable to walk ‘within ten steps’ or who felt ‘dizzy’ and ‘so tired’ during physical activity found that after PD, they were able to walk for extended periods of time.

Restoring energy for life participation

For some patients, PD led to an increase in energy, which allowed greater participation in meaningful activities. For these patients, this meant having more time with their family or being able to do more household duties prior to commencing dialysis.

Personal growth through adjustment

Building resilience and enabling positive outlook

Some patients, particularly those from Australia and the USA, believed that being able to manage the challenges of PD made them ‘a stronger person’ and ‘pushed’ them more in life. For others, a ‘happy attitude’ was most important to them in addition to believing that their ‘dialysis is not going to defeat’ them. Some patients also believed that PD changed their life for the better, by helping them ‘see life better’, set priorities and by giving them a ‘second chance at life’.

Accepting the dialysis regimen

Some patients explained that they had to overcome preconceived fears or concerns about dialysis to learn to live with PD. For some, their expectations of dialysis were more distressing or ‘scary’ than the reality they encountered. For others, they gradually became ‘used to the new form of living’ or ‘routine’ and now described dialysis as a task similar to ‘cleaning your teeth’.

DISCUSSION

Patients and caregivers believed that lack of understanding of the rationale for lifestyle restrictions imposed by PD and the inconsistencies in the information given by their different specialists compromised their motivation and ability to manage PD. This also interfered with their capacity to engage in collaborative dialog and make shared decisions about their PD regimen with their healthcare providers. Some patients felt that the unremitting and onerous demands of their PD regimens meant that they had to remain close to home, which diminished their control over their lifestyles. The schedule of PD exchanges and lifestyle restrictions constrained their opportunities for life participation. However, continuous practical training with medical and emotional support from health professionals and family support enabled and equipped patients to problem-solve and manage their technically demanding regimens. Some adapted their dialysis schedules so they could engage in meaningful life activities. They felt empowered when they disentangled their personal identity from CKD and PD, experienced improvement in physical function and energy, and learned to accept and routinize PD into daily living.

Some differences in perspectives were apparent, particularly according to dialysis modality, comorbidities, age, sex and country of residence. Those on CAPD tended to experience greater interruption to life activities, while patients on APD were less conscious of the time and felt more ‘free’ in the daytime. Previous research has also found that patients on CAPD had less time to engage in meaningful life activities than those on APD [19]. Patients with more comorbidities in particular felt they received conflicting information from different specialists. Younger patients struggled with having to be close to home as it limited their ability to travel. Patients and caregivers from focus groups in Australia and the USA felt it was important to delineate their individual identity from their illness and PD regimens.

A systematic review similarly found that patients on PD develop a sense of empowerment with increasing confidence in their self-management, successful problem solving and negotiating lifestyle restrictions, while lack of information and limitations on social activities left them feeling overwhelmed and without control [20]. Patients on PD in other studies also identified emotional and practical support from health professionals and family, flexibility, ongoing education and acceptance of personal responsibility as being critical in supporting self-management [3, 21–23]. This study also suggests that, by resisting lifestyle restrictions imposed by the PD regimen and separating their personal identity from illness, patients felt a greater sense of control and had improved positive attitude.

A conceptual analysis of patient empowerment in a hospital context described empowerment as an enabling process of growth and self-determination, which is supported by effective and considerate dialog, capacity building and active partnership, and results in increased quality of life, self-efficacy, sense of mastery, coping skills and shared decision-making [7]. Our study supported the critical role that knowledge and dialog have in enabling self-management, control over lifestyle and improved quality of life, and further suggests that overcoming challenges associated with CKD and PD could foster resilience and personal growth.

Our findings have implications for clinical care in terms of education, training and developing strategies to minimize life disruption and improve life participation of patients. Education that increases patients’ overall health literacy and knowledge of PD self-management would encourage more informed and shared decision-making, particularly when concerning decisions around potential regimen restrictions on patients’ meaningful and necessary life activities. Knowledge is a frequent component of empowerment interventions in the CKD population and has been shown to help improve health-related quality of life [10], medication adherence [11] and blood pressure [13]. Nurses can support patients in developing and improving skills in doing PD, beyond the initial training period, and help build the confidence and ability of patients to problem-solve, for example if they encounter technical complications. For example, a previous study found a retraining intervention reduced the incidence of peritonitis in patients on PD and others found increased training and assistance from health professionals may improve self-management [24–28]. By prioritizing the flexibility of PD regimen schedules and providing patients with practical strategies enabling them to dialyze safely outside the home setting, clinicians can help patients to effectively manage and integrate PD around their daily tasks and priorities.

A systematic review found that patient empowerment interventions across health conditions that included practical skill training and action planning were more likely to be more effective than others that included knowledge alone [29]. Patient empowerment interventions may have potential to improve motivation, control over lifestyle and confidence in patients on PD, and we suggest that this is an area that requires further evidence. Specifically, a trial of interventions that increase flexibility of PD prescriptions (such as an intermittent day off) on patients’ treatment outcomes and satisfaction may be relevant. However, such interventions may need to be individualized as patients have different capacities and needs [3, 8, 22, 30]. Different populations may also require tailored approaches. For example, older patients on PD may find in-person support groups more beneficial than digital health programs [11], whereas patients on PD living in rural and remote locations may benefit more from telemedicine than in-person support groups in distant locations [31]. Assisted PD, where practical support for all or part of the dialysis exchange is provided by another person, for example, a nurse or family member, may improve patient outcomes and satisfaction compared with in-center HD [32, 33]. The policies and availability of assisted PD varies across the participating countries. Hong Kong has implemented a ‘PD first’ policy where PD solutions are fully subsidized by the government yet the cost of an assistant (typically a family member, domestic helper or a nursing home assistant) is self-funded, with the exception of nursing home assistants who are already included in nursing home accomodation costs [34]. In Australia and the USA, assisted PD is less readily available unless funded or provided by the patient’s family [35, 36]. Data were not collected on the proportion of participants receiving assisted PD in this study. While patients and caregivers had similar perspectives of the meaning and role of patient empowerment, further research could focus on the caregivers’ experiences and perspectives of their own sense of empowerment in PD and identify any specific needs for support for caregivers.

Our multinational study conducted in three countries and in two languages provided diverse and in-depth insights into patient empowerment from patients receiving PD and their caregivers. We achieved data saturation and used researcher triangulation to ensure that themes reflected the depth and breadth of the data. However, there are some potential limitations. Patients and caregivers came from many different PD centers with varying practices around training, psychosocial support and tailoring of PD prescription. We conducted the majority of focus groups with English-speaking participants with the exception of one Spanish-speaking group, so the transferability of findings in other countries with different healthcare systems and cultures is uncertain, particularly in low-to-middle-income countries, where patients may experience more socioeconomic barriers that may impact on access to and self-management of PD. As patients and caregivers participated in focus groups together, we recognize that it is possible that participants may have censored some information from the person known to them who was present in the same group.

Being overwhelmed and uncertain because of lack of knowledge or receiving conflicting advice, and being restrained in time and capacity for meaningful and necessary life activities outside the home contributed to the loss of control over lifestyle, confidence and physical and emotional capacity to manage PD. Patients emphasized that understanding the clinical rationale underpinning lifestyle restrictions, having ongoing practical training and receiving the support of family in managing their technically demanding treatment regimens strengthened their sense of empowerment. Some learned to adapt to and routinize the PD schedule in an effort to maintain personal freedom and autonomy. Education and counseling that improve health literacy, knowledge, practical skills, problem-solving and time-management may improve informed and shared decision-making, acceptance of PD, opportunities for life participation, treatment satisfaction and outcomes in patients and their families.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary data are available at ndt online.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank all the patients and caregivers who gave their time to participate in this study.

FUNDING

A.T. is supported by a National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Fellowship (APP1106716). K.E.M. is supported by a NHMRC Postgraduate Scholarship (APP1151343). D.W.J. has received consultancy fees, research grants, speaker’s honoraria and travel sponsorships from Baxter Healthcare and Fresenius Medical Care, consultancy fees from Astra Zeneca and AWAK Technologies, speaker’s honoraria and travel sponsorships from ONO Pharmaceutical, and travel sponsorships from Amgen. He is supported by a NHMRC Practitioner Fellowship. A.K.V. reports having received grant support from the NHMRC of Australia (Medical Postgraduate Scholarship) and the Royal Australasian College of Physicians (Jacquot National Health and Medical Research Council Medical Award for Excellence). J.I.S. is supported by grants K23DK103972 from the National Institutes of Health - National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIH-NIDDK). Y.C. has received research grants, speaker’s honoraria from Baxter Healthcare and Fresenius Medical Care. She is supported by a NHMRC Early Career Fellowship. A.Y.-M.W. received speaker’s honoraria and travel fees from Fresenius Kabi and Sanofi Renal and research grant from Baxter Healthcare and Sanofi Renal. R.M. has received personal fees from Baxter Healthcare. R.P.-F. received speaker’s honoraria from Astra Zeneca and research grants from Fresenius Medical Care. J.P. has received speaker’s honoraria from Astra Zeneca, Baxter Healthcare, Fresenius Medical Care, Davita Healthcare Partners, Dialysis Clinics Incorporated and Satellite Healthcare and has received consultancy fees from Baxter Healthare, Davita Healthcare Partners and LiberDi. M.W. has received speaker’s honoraria from Baxter Healthcare and Fresenius Medical care, and consultancy fees from Baxter Healthcare and Triomed. The funding organization had no role in the preparation, review or approval or the manuscript.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

A.B., K.E.M., D.W.J., J.C.C., A.Y.-M.W., E.A.B., G.B., J.D., T.D., R.M., S.N., R.P.-F., J.P., M.W. and A.T. were involved in the research idea and study design; data collection, analysis and interpretation were carried out by A.B., K.E.M., D.W.J., J.I.S., L.R., A.Y.-M.W., T.Y., S.K.S.F., M.T., A.L., Y.C., A.K.V., B.S. and A.T.; drafting of the manuscript was done by A.B., K.E.M. and A.T.; and all authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

D.W.J. reports consultancy fees from Baxter Healthcare, Fresenius Medical Care, Astra Zeneca and AWAK Technologies; grants from Baxter Healthcare and Fresenius Medical Care; speaker’s honoraria from Baxter Healthcare, Fresenius Medical Care and ONO; and travel sponsorships from Baxter Healthcare, Fresenius Medical Care, ONO Pharmaceutical and Amgen. Y.C. has received grants and speaker’s honoraria from Baxter Healthcare and Fresenius Medical Care. J.I.S. reports grants from NIH-NIDDK during the conduct of this study. A.Y.-M.W. reports grants from Baxter Healthcare and Sanofi Renal, and speaker’s honoraria and travel fees from Fresenius Kabi and Sanofi Renal. R.M. reports personal fees from Baxter Healthcare outside the submitted work. R.P.-F. reports speaker’s honoraria from Astra Zeneca and grants from Fresenius Medical Care. J.P. reports speaker’s honoraria from Astra Zeneca, Baxter Healthcare, Fresenius Medical Care, Davita Healthcare Partners, Dialysis Clinics Incorporated and Satellite Healthcare and consultancy fees from Baxter Healthcare, Davita Healthcare Partners and LiberDi. M.W. reports personal fees from Baxter Healthcare, Fresenius Medical Care and Triomed outside the submitted work. The remaining authors report no conflicts of interest relevant to this article to disclose. The results presented in this article have not been published previously in whole or part, except in abstract format.

REFERENCES

- 1. Curtin RB, Johnson HK, Schatell D.. The peritoneal dialysis experience: insights from long-term patients. Nephrol Nurs J 2004; 31: 615–624 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Morton R, Tong A, Howard K. et al. The views of patients and carers in treatment decision making for chronic kidney disease: systematic review and thematic synthesis of qualitative studies. Br Med J 2010; 340: c112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Walker RC, Howard K, Morton RL. et al. Patient and caregiver values, beliefs and experiences when considering home dialysis as a treatment option: a semi-structured interview study. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2016; 31: 133–141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Campbell DJ, Craig JC, Mudge DW. et al. Patients’ perspectives on the prevention and treatment of peritonitis in peritoneal dialysis: A semi-structured interview study. Perit Dial Int 2016; 36: 631–639 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Tong A, Lesmana B, Johnson DW. et al. The perspectives of adults living with peritoneal dialysis: thematic synthesis of qualitative studies. Am J Kidney Dis 2013; 61: 873–888 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Rashid T. Positive psychotherapy: a strength-based approach. J Posit Psychol 2015; 10: 25–40 [Google Scholar]

- 7. Castro EM, Van Regenmortel T, Vanhaecht K. et al. Patient empowerment, patient participation and patient-centeredness in hospital care: a concept analysis based on a literature review. Patient Educ Couns 2016; 99: 1923–1939 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Tims SJ, King L, Bennett PN.. Empowerment for people with end stage renal disease: a literature review. Ren Soc Aust J 2007; 3: 52–58 [Google Scholar]

- 9. Curtin RB, Mapes D, Petillo M. et al. Long-term dialysis survivors: a transformational experience. Qual Health Res 2002; 12: 609–624 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lee SJ. An empowerment program to improve self-management in patients with chronic kidney disease. Korean J Adult Nurs 2018; 30: 426–436 [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hsiao C-Y, Lin L-W, Su Y-W. et al. The effects of an empowerment intervention on renal transplant recipients: A randomized controlled trial. J Nurs Res 2016; 24: 201–210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Royani Z, Rayyani M, Behnampour N. et al. The effect of empowerment program on empowerment level and self-care self-efficacy of patients on hemodialysis treatment. Iran J Nurs Midwifery Res 2013; 18: 84–87 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Moattari M, Ebrahimi M, Sharifi N. et al. The effect of empowerment on the self-efficacy, quality of life and clinical and laboratory indicators of patients treated with hemodialysis: a randomized controlled trial. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2012; 10: 115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Chen YC, Pai JS, Li IC.. Haemodialysis: the effects of using the empowerment concept during the development of a mutual‐support group in Taiwan. J Clin Nurs 2008; 17: 133–142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Tsay S-L, Hung L-O.. Empowerment of patients with end-stage renal disease—a randomized controlled trial. Int J Nurs Stud 2004; 41: 59–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Manera KE, Johnson DW, Craig JC. et al. Patient and caregiver priorities for outcomes in peritoneal dialysis: Multinational nominal group techniquestudy. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2019; 14: 74–83 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J.. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care 2007; 19: 349–357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Strauss A, Corbin J.. Basics of Qualitative Research Techniques. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage publications, 1998 [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bro S, Bjorner JB, Tofte-Jensen P. et al. A prospective, randomized multicenter study comparing APD and CAPD treatment. Perit Dial Int 1999; 19: 526–533 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Palmer SC, Hanson CS, Craig JC. et al. Dietary and fluid restrictions in CKD: a thematic synthesis of patient views from qualitative studies. Am J Kidney Dis 2015; 65: 559–573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Subramanian L, Quinn M, Zhao J. et al. Coping with kidney disease–qualitative findings from the Empowering Patients on Choices for Renal Replacement Therapy (EPOCH-RRT) study. BMC Nephrol 2017; 18: 119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Nygårdh A, Wikby K, Malm D. et al. Empowerment in outpatient care for patients with chronic kidney disease-from the family member’s perspective. BMC Nurs 2011; 10: 21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Nygårdh A, Malm D, Wikby K. et al. The experience of empowerment in the patient–staff encounter: the patient’s perspective. J Clin Nurs 2012; 21: 897–904 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gadola L, Poggi C, Poggio M. et al. Using a multidisciplinary training program to reduce peritonitis in peritoneal dialysis patients. Perit Dial Int 2013; 33: 38–45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Schaepe C, Bergjan M.. Educational interventions in peritoneal dialysis: a narrative review of the literature. Int J Nurs Stud 2015; 52: 882–898 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Su CY, Lu XH, Chen W. et al. Promoting self‐management improves the health status of patients having peritoneal dialysis. J Adv Nurs 2009; 65: 1381–1389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hurst H, Figueiredo AE.. The needs of older patients for peritoneal dialysis: training and support at home. Perit Dial Int 2015; 35: 625–629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Bordin G, Casati M, Sicolo N. et al. Patient education in peritoneal dialysis: an observational study in Italy. J Ren Care 2007; 33: 165–171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Werbrouck A, Swinnen E, Kerckhofs E. et al. How to empower patients? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Transl Behav Med 2018; 8: 660–674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Burnette L, Kickett M. ‘ You are just a puppet’: Australian aboriginal people’s experience of disempowerment when undergoing treatment for end-stage renal disease. Ren Soc Aust J 2009; 5: 113–118 [Google Scholar]

- 31. Rygh E, Arild E, Johnsen E. et al. Choosing to live with home dialysis-patients’ experiences and potential for telemedicine support: a qualitative study. BMC Nephrol 2012; 13: 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Griva K, Goh C, Kang W. et al. Quality of life and emotional distress in patients and burden in caregivers: a comparison between assisted peritoneal dialysis and self-care peritoneal dialysis. Qual Life Res 2016; 25: 373–384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Brown EA, Wilkie M.. Assisted peritoneal dialysis as an alternative to in-center hemodialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2016; 11: 1522–1524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ng J-C, Chan G-K, Chow KM. et al. Helper-assisted continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis: Does the choice of helper matter? Perit Dial Int 2020; 40: 34–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Fortnum D, Chakera A, Hawkins N. et al. With a little help from my friends: Developing an assisted automated peritoneal dialysis program in Western Australia. Ren Soc Aust J 2017; 13: 83–89 [Google Scholar]

- 36. Oliver MJ, Salenger P.. Making assisted peritoneal dialysis a reality in the United States: a Canadian and American Viewpoint. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2019; 15: 566–568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.