Abstract

Nanoscale carbon black as virtually pure elemental carbon can deposit deep in the lungs and cause pulmonary injury. Airway remodeling assessed using computed tomography (CT) correlates well with spirometry in patients with obstructive lung diseases. Structural airway changes caused by carbon black exposure remain unknown. Wall and lumen areas of sixth and ninth generations of airways in 4 lobes were quantified using end-inhalation CT scans in 58 current carbon black packers (CBPs) and 95 non-CBPs. Carbon content in airway macrophage (CCAM) in sputum was quantified to assess the dose-response. Environmental monitoring and CCAM showed a much higher level of elemental carbon exposure in CBPs, which was associated with higher wall area and lower lumen area with no change in total airway area for either airway generation. This suggested small airway wall thickening is a major feature of airway remodeling in CBPs. When compared with wall or lumen areas, wall area percent (WA%) was not affected by subject characteristics or lobar location and had greater measurement reproducibility. The effect of carbon black exposure status on WA% did not differ by lobes. CCAM was associated with WA% in a dose-dependent manner. CBPs had lower FEV1 (forced expiratory volume in 1 s) than non-CBPs and mediation analysis identified that a large portion (41–72%) of the FEV1 reduction associated with carbon black exposure could be explained by WA%. Small airway wall thickening as a major imaging change detected by CT may underlie the pathology of lung function impairment caused by carbon black exposure.

Keywords: carbon black, airway wall thickening, carbon content in airway macrophage, dose-response, mediation effect

Carbon black (Chemical Abstracts Service Registry No. 1333-86-4) is virtually pure elemental carbon (EC) that is produced by partial combustion or thermal decomposition of gaseous or liquid hydrocarbons. Worldwide carbon black production in 2012 was about 11 million metric tons with >90% of production consumed in rubber industry (International Carbon Black Association, 2016). Carbon black aggregates as the smallest inseparable entities are of nanoscale (ie, 100–1000 nm in diameter; Gray and Muranko, 2006) with inhalation exposure as the major path in humans during manufacture (International Carbon Black Association, 2016). Epidemiological studies have established strong links between environmental and occupational exposures to many types of inhalable particulate matters (PMs) such as traffic-related fine PM, diesel exhaust particles, coalmining dust, and organic cotton dust and stunted lung development in children and lung function deterioration and mortality in adults (Guo et al., 2018; Lotz et al., 2008; Morfeld et al., 2010; Pelucchi et al., 2009; Peng et al., 2008; Wang et al., 2020; Zanobetti and Schwartz, 2009). Occupational epidemiological studies conducted in workers with chronic exposure to carbon black also identified that both cross-sectional and cumulative exposure have a deleterious effect on respiratory morbidities as reflected by increased prevalence of cough and phlegm, reduced spirometry (eg, forced expiratory volume in 1 s [FEV1]), and formation of small opacities on chest X-ray (Gardiner et al., 1993, 2001; Harber et al., 2003; van Tongeren et al., 2002). Our studies of a cohort of carbon black packers (CBPs) with PM exposure levels over 800 μg/m3 identified serological evidence indicative of Clara cell injury and elevated permeability of acinar airways (Dai et al., 2016; Yang et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2014). In addition, subchronic toxicity studies identified evidence of lung tissue remodeling in exposed rats (Chu et al., 2019; Han et al., 2020). However, lung tissue remodeling underneath the observed phenotypic changes in workers is largely unknown.

Airway remodeling commonly seen in patients with asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) pathologically consists of structural changes within the airway wall, such as an increased epithelium basal membranous thickness, hypertrophy of the smooth muscle cell, and peribronchial fibrosis (Dournes and Laurent, 2012). Airway remodeling parameters obtained through tissue biopsies are related to important pheno- and endo-types in animal and human studies (Bergeron et al., 2007; Fehrenbach et al., 2017; Petersen et al., 2018). However, human studies had limited availability of lung biopsies for assessing lung remodeling. With the recent technical advancement of quantitative computed tomography (CT) and analytical informatics, morphological changes of intermediate to small airways (eg, airway wall and lumen thickness) and emphysema-like lung parenchymal impairment could be determined using end-inhalation CT scans in patients with asthma or COPD and correlate well with biopsy findings (Dournes and Laurent, 2012; Kirby et al., 2018). Thus, with these advanced techniques, we are able to generate a comprehensive mapping of the airway remodeling in the lungs of carbon black workers based on which novel pathophysiological features attributable to carbon black induced pulmonary toxicity may be identified.

Carbon content in airway macrophages (CCAMs) as a quantitative measure for lung EC burden serves as a bio-effective dosimeter for chronic exposure to carbon black aerosol and PMs in air pollution and correlates well with multiple health effects (Bai et al., 2015, 2018b; Belli et al., 2016; Cheng et al., 2020; Jacobs et al., 2010, 2011; Kalappanavar et al., 2012; Kulkarni et al., 2006; Nwokoro et al., 2012; Whitehouse et al., 2018). Our own analysis of current and former CBPs (Cheng et al., 2020) and others (Bai et al., 2015, 2018a) have suggested a constant decline rate of carbon black areas in macrophages ranging from 0.0013 to 0.0060 µm2 per day based on which an estimated half-life of 7 years was proposed for carbon black clearance in macrophages after CBPs retired (Cheng et al., 2020).

In this study, we hypothesized that chronic exposure to carbon black particulates in current CBPs may cause airway remodeling as a pathophysiological basis underlying lung function impairment. This was assessed through CT scanning of 58 current CBPs and 95 non-CBPs from China. The study design, variables measured, and overall analytic plan all followed a framework for mediation analysis (Figure 1). Airway dimensions were quantified for the sixth and ninth generations of tracheobronchial tree, the very beginning segments of small airways. The findings of this study provided the first comprehensive mapping of airway remodeling in workers exposed to airborne carbon black aerosol and may shed light on the understanding of the pulmonary toxicity of other nanoparticle exposures in humans.

Figure 1.

Airway wall thickening mediating carbon black exposure induced lung function impairment. The study design, variables measured, and overall analytic plan all followed a framework for mediation analysis. In mediation analysis (A), the c coefficient denotes the direct effect of carbon black exposure on spirometry, without controlling for airway wall thickening (eg, WA%, mediator). The c' coefficient denotes the direct effect of carbon black exposure on spirometry, controlling for airway wall thickening (mediator). The proportion mediated is equal to delta c (ie, c–c') divided by c. We took a permutation-based method to assess whether the proportion mediated was statistically significant or not (B). The relationship between spirometry and the vector of independent variables was permuted for 500 times. Each permutated database allowed the association analysis of spirometry with carbon black exposure and other covariates without and with including wall area percent (WA%) to calculate the c and c'. Permutation was conducted for 500 times to generate the distribution of c–c' under null hypothesis of no mediation. Value of c-c' calculated using observed data (−0.15) for associations between carbon black exposure and forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1) was compared with the distribution generated by permutation and Pperm was calculated as the number of permuted databases generating a c–c' that is smaller than observed value (n = 0 for FEV1) divided by 500. Thus, Pperm was < 0.002 in this case.

STUDY SUBJECTS AND METHODS

Study Population

The protocol was approved by the Medical Ethical Review Committee of the National Institute for Occupational Health and Poison Control, Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention (protocol number: NIOHP201604). Written informed consent was acquired from all participants prior to the interview and any procedures. Design details of the CBP study were published previously (Yang et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2014). A follow-up visit was conducted in the fall of 2018 and enrolled 105 non-CBPs and 70 CBPs (Cheng et al., 2020). Airway dimension and covariate data were complete for 95 non-CBPs and 58 CBPs (Supplementary Table 1). Age, percent predicted values of FEV1 and forced vital capacity (FVC), and CCAM were of no difference between the 153 subjects in the study and 22 subjects excluded from this study, suggesting that our analyses were less likely to be biased by exclusion of these 22 subjects.

Exposure Assessment

We assessed PM2.5, PM2.5-related EC, organic carbon (OC), total carbon (TC), and particle size distributions in carbon black bagging facilities and control areas with technical details described in references (Cheng et al., 2020; Dai et al., 2016; Zhang et al., 2014).

CCAM Assay

Induced sputum sample was stored in Saccomano’s fixative at room temperature prior to processing. Detailed experimental procedure was introduced in (Cheng et al., 2020). Photos for 50 randomly selected and well-stained macrophages with intact cytoplasm (Figs. 2A–D) per subject were analyzed (Cheng et al., 2020). Upper quartile of the proportion of cytoplasm area occupied by carbon particles from 50 macrophages was used as the CCAM index for all association analyses (Cheng et al., 2020). The utility of the proportion of cytoplasm area occupied by carbon particles may avoid biases derived from different size of macrophages due to cigarette smoking and carbon particles overlapping with nuclei (Bai et al., 2015; Cheng et al., 2020; Frankenberger et al., 2004).

Figure 2.

Representative photos of macrophages containing varied amount of carbon particles (A–D) and carbon content in airway macrophage (CCAM) levels by carbon black exposure and smoking status (E). Four well-stained macrophages were identified from a sputum sample from a female carbon black packer (CBP) who was never smoker and had a carbon black working history of 8 years. The values of carbon black area in nucleus negative cytoplasm area were 1.34, 10.40, 13.61, and 24.86 μm2 for macrophages A–D, respectively. The values of CCAM were 0.34%, 2.47%, 2.76%, and 4.46% for macrophages A–D, respectively. The median levels of CCAM were 1.4 and 10.8 for 61 non-CBPs and 35 CBPs, respectively. The ps = .75 and .60 between ever (blue, left) and never (red, right) smokers in CBPs and non-CBPs, respectively. Sample sizes were 26, 9, 28, and 33 for CBP ever smokers, CBP never smokers, non-CBP ever smokers, and non-CBP never smokers, respectively. The 5 horizontal bars from bottom to top represent the minimum, first quartile, median, third quartile, and maximum. Symbols (eg, ○ and +) represent means.

Acquisition of Quantitative CT

All CT scans were acquired by board certified radiologists with expertise in CT imaging. CT scans at full inspiration were acquired using a 64-slice CT scanner (LightSpeed VCT XT or OPTIMA CT660, GE Healthcare, USA) from apex to base of the lung without contrast. The scanning parameters were set at 120 kVp, auto mA, gantry rotation of 0.6 r/s, pitch of 0.985, 0.625-mm slice thickness, and continuous slices. The standard or lung reconstruction kernel was used for building images.

CT Image Analysis

Radiological impression of lung changes was made by a board certified radiologist. Detailed procedure of airway measurement was described in Supplementary Materials. CT images were evaluated using the Philips IntelliSpace Portal 9.0 (Royal Philips, The Netherlands). Four broncho-pulmonary segmental airways in separate lobes bilaterally that run orthogonal to the axial plane were selected. The wall and lumen area at the midpoint of the sixth and the ninth bronchus generations on the longest airways downstream of the candidate segmental airways were measured by an extensively trained analyst. Airway measurements from 43 quantitative CTs randomly selected were measured independently by a second analyst with good to excellent intra-class correlation coefficients.

Spirometry

Spirometry was conducted without inhaling bronchodilator by a certified technician using a portable calibrated electronic spirometer (CHESTGRAPH HI-701, Japan) in accordance with the American Thoracic Society and European Respiratory Society standards (Miller et al., 2005).

Statistical Analysis

Due to interlobe variation of crude airway dimensions (eg, wall, lumen, and airway areas) across the 4 studied airways (Supplementary Table 2), rather than simply averaging measurements from 4 airways, we regarded these measurements as repeated measurements and modeled their associations with carbon black exposure and other variables using linear mixed effects (LME) model. Age, sex, excess weight (body mass index >25), smoking status, packyears, CT reconstruction method (ie, standard vs lung), and lung lobes were selected a priori as covariates for adjustment for analyses with airway dimensions as the outcome. Two interaction analyses including lung lobes × carbon black exposure and cigarette smoking status × carbon black exposure were designed a priori. Height was adjusted in model with spirometry as the outcome. In addition to binary carbon black exposure status, CCAM was also used as a bio-effective dosimeter for exposure to carbon black aerosol in the lungs to characterize the dose-response. In relevant analyses, area measurements except wall area percent (WA%) were natural log transformed to improve normality of the residual and satisfy the homoscedasticity assumption. Mediation analysis (Cheng et al., 2020) was conducted to assess whether carbon black exposure status and spirometry associations could be mediated by inclusion of airway dimensional measurements. All statistical analyses were conducted using SAS (version 9.4, North Carolina, sites 70239492 and 70080753).

RESULTS

Physicochemical Characteristics of Carbon Black Particles

Physicochemical characteristics of carbon black particles have been assessed extensively in reference (Zhang et al., 2014). A thermal decomposition of acetylene technique was used to manufacture carbon black in the studied facility. Accordingly, carbon black product from this facility has a very high carbon purity (>99.8%). Under a transmission electron microscope, the primary carbon black unit consists of globular shaped particles with diameters ranging from 30 to 50 nm. A scanning electron microscope identified formation of aggregates and agglomerates with hundreds to thousands of nanometers in at least one dimension and forming an aciniform morphology (Zhang et al., 2014). Carbon black has a surface area of 74.85 m2/g measured using the Brunauer-Emmett-Teller method. Carbon black suspension in water has a zeta potential of −15.37 mV.

Environmental Monitoring

Up to 99.6% carbon black particulates had aerodynamic diameter <2.5 μm with 96.7% particulates <1.0 μm (Dai et al., 2016). Geometric mean of PM2.5 level in carbon black bagging areas was 637.4 μg/m3, which was significantly higher than that seen in the reference areas (130.0 μg/m3, Supplementary Table 1). The ratio of PM2.5 related EC to TC is 92.5% in 2 air samples collected from carbon black bagging areas, consistent with acetylene carbon black as almost pure EC (Dai et al., 2016). Our analysis of urinary hydroxyl polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in 2012 survey identified no difference between CBPs and non-CBPs, further ensuring the high carbon purity of carbon black (Tang et al., 2020).

Characteristics of Study Subjects

CBPs were more likely to be men and ever smokers, and to report less packyears among ever smokers, than non-CBPs (Supplementary Table 1). CBPs had a median exposure history of 8.0 years. CCAM was significantly higher in CBPs than non-CBPs (Figure 2E). Cigarette smoking did not affect CCAM at all in either CBPs or non-CBPs (Figure 2E). When compared with non-CBPs, CBPs had higher prevalence of phlegm production and lower FEV1 and FVC for both raw and percent predicted values (Yang et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2014). CT-assessed total lung volume was not different between the 2 groups.

Association Between Clinical Characteristics and Airway Dimensions

Airways of sixth and ninth generations of tracheobronchial tree had diameters of 4.4–5.0 and 2.6–2.9 mm, respectively (footnote of Supplementary Table 2). The ninth generation airways had relatively thinner wall than the sixth generation (Supplementary Table 3). For sixth generation airways, wall and lumen areas were affected by age, sex, excess weight, and lobar location, whereas WA% was affected by excess weight only (Supplementary Tables 2–4). For ninth generation airways, wall and lumen areas were affected by excess weight and lobar location, whereas WA% was affected by excess weight only (Supplementary Tables 2, 3, and 5). Interestingly, cigarette smoking status and packyears had no effects on any of these measurements (Supplementary Tables 4 and 5).

Carbon Black Exposure Status and Airway Dimension

LME model identified significantly higher wall area and lowered lumen area in CBPs versus non-CBPs with total airway area of no difference between these 2 groups for both sixth and ninth generations of airways (Supplementary Tables 6 and 7). Accordingly, significantly increased WA% was also identified in CBPs versus non-CBPs for both generations of airways (Table 1). Because WA% was less prone to be affected by age, sex, and lobar location compared with crude area measurements, the former was used for all subsequent analysis. No interactions between lobes and carbon black exposure on WA% was identified (all ps > .59, Table 1) in the LME model, suggesting different lung lobes may be similarly affected by carbon black aerosol. Stratification analysis found that although the magnitude of associations seem stronger in never smokers versus ever smokers, the differences did not reach statistical significance (p = .56 for sixth and p = .07 for ninth; Table 1). No association was identified between carbon black exposure history and sixth WA% in CBPs (p = .48). However, a suggestive association was identified between carbon black exposure history and ninth WA% in CBPs with every 5-year increase associated with 1.8% increase in ninth WA% (p = .064). A subset of study subjects (14 CBPs and 7 non-CBPs) self-reported to be exposed to occupational hazards such as noise, heat, dust, strong acid, or oxidative during their prior employment. Removal of these subjects in data analyses did not affect the associations between carbon black exposure and WA% for sixth and ninth generations of airways (not shown).

Table 1.

The Effect of Carbon Black Exposure Status on WA% in all Study Subjectsa

| Variable | Non-CBP (n = 95) | CBP (n = 58) | β (95%CI) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sixth generation WA% | ||||

| LB1 + 2 | 52.0 ± 14.1 | 61.1 ± 10.4 | ||

| LB9 | 49.9 ± 12.7 | 58.7 ± 12.1 | ||

| RB9 | 52.3 ± 12.5 | 62.2 ± 10.5 | ||

| RB1 | 51.0 ± 12.4 | 58.5 ± 11.4 | ||

| All (n=153) | 51.4 (49.4, 53.4) | 60.0 (57.4, 62.6) | 8.60 (5.17, 12.03) | <.0001 |

| Never smokers (n = 73) | 48.8 (46.1, 51.5) | 59.9 (54.5, 65.3) | 11.09 (4.69, 17.49) | .0008 |

| Ever smokers (n = 80) | 53.7 (50.9, 56.5) | 61.5 (58.7, 64.2) | 7.76 (3.83, 11.70) | .0001 |

| Ninth generation WA% | ||||

| LB1 + 2 | 43.3 ± 15.4 | 51.8 ± 13.8 | ||

| LB9 | 43.3 ± 16.4 | 52.2 ± 18.3 | ||

| RB9 | 42.7 ± 15.4 | 49.3 ± 17.1 | ||

| RB1 | 43.9 ± 13.2 | 50.3 ± 14.7 | ||

| All (n = 153) | 43.4 (40.6, 46.2) | 50.7 (47.1, 54.3) | 7.31 (2.49, 12.13) | .003 |

| Never smokers (n = 73) | 40.8 (37.5, 44.0) | 55.1 (48.7, 61.5) | 14.32 (6.71, 21.94) | .0003 |

| Ever smokers (n = 80) | 46.0 (41.5, 50.4) | 50.1 (45.7, 54.4) | 4.11 (-2.19, 10.42) | .20 |

Abbreviations: CBP, carbon black packer; CI, confidence interval; LB, left bronchus; RB, right bronchus.

LME model assessed differences of sixth and ninth WA% between non-CBPs and CBPs with adjustment of age, sex, excess weight, smoking status, packyears, CT reconstruction method, and lung lobes. Wall area % was shown as mean ± SD due to its approximately normal distribution. Interaction terms between lung lobe and carbon black exposure status were not significant for either generations (all ps > .59). Interaction terms between smoking status and carbon black exposure status were not significant for either sixth (p = .56) or ninth (p = .07) generations. Packyears were not included in the model for covariate adjustment when smoking status and carbon black exposure status interaction or stratification analyses by smoking status were conducted. Descriptive statistics for all or by smoking status were least square means and 95% CIs that were calculated based on wall area % using LME model with adjustment for covariates listed above. All may be regarded as an overall level of wall area % based on the 4 sampled airways of sixth or ninth generations.

Association Between CCAM and WA%

A total of 61 non-CBPs and 35 CBPs had CCAM available (Cheng et al., 2020). The scatter plots between CCAM with and without natural log transformation and WA% for sixth and ninth generations of airways suggested a dose-dependent linear relationship (Figure 3). Because CCAM distribution was heavily skewed, the dose-response based on log-transformed CCAM was used to quantify its association with WA%. Each 2.72-fold increase in CCAM was associated with a 3.04% and 3.07% increase in WA% for sixth and ninth generations of airways (Supplementary Table 8). Restricting analyses in the 35 CBPs reproduced the associations between CCAM and WA% seen in the entire study population, though only association for WA% of the sixth generation of airways reached statistical significance (p = .031, Supplementary Table 8). We further tested whether the dose-response between CCAM and WA% varied by smoking status by including an interaction term between log-transformed CCAM and smoking status. Significant interaction terms were identified for ninth (p = .0078, Supplementary Figure 1) but not for sixth (p = .17) generations of airways, suggesting cigarette smoking may dampen the effect of carbon black exposure on airway wall thickening especially for smaller airway.

Figure 3.

Scatter plots and correlation between carbon content in airway macrophage (CCAM) and average wall area percent (WA%). A total of 61 non-carbon black packer (CBPs) and 35 CBPs had CCAM available. The scatter plots between CCAM with and without natural log transformation and WA% for sixth and ninth generations of airways suggested a dose-dependent linear relationship. Spearman coefficients for correlations of CCAM with sixth WA% and ninth WA% in 96 subjects were 0.28 (p < .0001) and 0.20 (p < .0001), respectively. Pearson coefficients for correlations of natural log transformed CCAM with sixth WA% and ninth WA% in 96 subjects were 0.28 (p < .0001) and 0.26 (p < .0001), respectively. Spearman coefficients for correlations of CCAM with sixth WA% and ninth WA% in 35 CBPs were 0.26 (p = .0016) and 0.16 (p = .064), respectively.

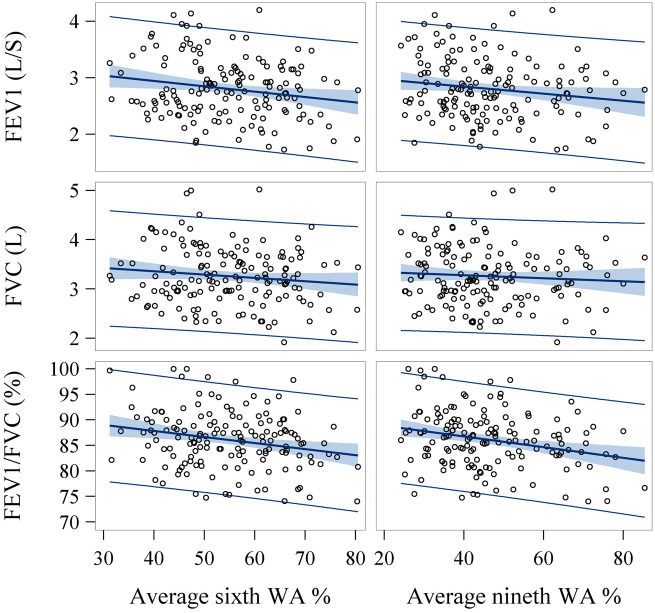

Correlation Between WA% and Spirometry

Because of no lobar disparity for WA% (Supplementary Table 3), we averaged the WA% from 4 airways and assessed their association with spirometry using generalized linear model (GLM; Supplementary Table 9). WA% was inversely associated with FEV1, FVC, and FEV1/FVC ratio (Figure 4 and Supplementary Table 9), suggesting airway wall thickening associated with lower lung function and higher airflow obstruction. Specifically, each 1% increase of WA% at sixth or ninth generations of airways was associated with a reduction of 15 and 9 ml/s in FEV1, respectively. Higher wall area and lower lumen area were also associated with lower spirometric measures (data not shown).

Figure 4.

Scatter plots and correlation between average wall area percent (WA%) and spirometry. Significant inverse associations were identified between average WA% at sixth and ninth generations of airways and spirometry measurements (eg, forced expiratory volume in 1 s [FEV1], forced vital capacity [FVC], and FEV/FVC). Pearson coefficients for correlations of sixth WA% with FEV1, FVC, and FEV1/FVC ratio were −0.19 (p = .018), −0.12 (p = .13), and −0.23 (p = .005), respectively. Pearson coefficients for correlations of ninth WA% with FEV1, FVC, and FEV1/FVC ratio were −0.16 (p = .047), −0.07 (p = .38), and −0.26 (p = .001), respectively.

Mediation Effect of WA% on Associations Between Carbon Black Exposure and Spirometry

We tested the hypothesis whether the effect of carbon black exposure on spirometric measures could be mediated by airway wall thickening. Mediation analyses identified that a large portion (41–72%) of associations between carbon black exposure status and spirometry (ie, FEV1 and FVC) could be explained by the inclusion of WA% in the model (Table 2 andFigure 1). In addition, sixth generation had larger mediation effect than the ninth generation.

Table 2.

Mediation Effect of Airway Wall Thickening (Measured by WA%) on associations Between Carbon Black Exposure and Spirometry in All Subjects (n = 153)

| Spirometry | WA% | WA%—Spirometrya |

Carbon Black Exposure—Spirometry |

Mediation Effectb |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β (SE) | p | β (SE) | p | PM | Pperm | ||

| FEV1 | Sixth WA% | −0.015 (0.003) | <.0001 | −0.042 (0.071)c | .55 | 0.72 | 0.002 |

| Ninth WA% | −0.009 (0.002) | .0001 | −0.090 (0.071)c | .21 | 0.41 | 0.004 | |

| FVC | Sixth WA% | −0.011 (0.003) | .0012 | −0.103 (0.081)c | .21 | 0.45 | 0.024 |

| Ninth WA% | −0.005 (0.002) | .048 | −0.150 (0.080)c | .063 | 0.19 | 0.10 | |

Abbreviations: FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 s; FVC, forced vital capacity; WA%, wall area percent; SE, standard error; CI, confidence interval; PM, the proportion mediated effect size.

Estimates were calculated per 1% increase in average WA% of 4 airways.

The proportion mediated effect size that quantifies the proportion of a total effect mediated was calculated using the following equation: (C–C′)/C. Pperm was calculated as described in Cheng et al. (2020).

The estimates of carbon black exposure status (ie, CBPs vs non-CBPs) for affecting FEV1 and FVC were -0.15 (SE = 0.07, p = .039) and −0.19 (SE = 0.08, p = .021), respectively when the model did not include airway thickening measurements (Supplementary Table 1). GLM was used with adjustment of age, sex, height, excess weight, smoking status, and packyears.

DISCUSSION

With the 64-slice quantitative CT and advanced analytical informatics platform, we were able to reliably and directly measure dimensions for sixth and ninth generations of airways, the very beginning segments of small airways, in current workers exposed to a high level of nanoscale carbon black aerosol. Wall thickening of these small airways was identified to be a major pathological changes that had a linear dose-response relationship with lung biomarker of carbon black exposure. Airways in all lobes were similarly affected, suggesting a relatively even distribution of particulates deposited in different parts of the lung. Most importantly, mediation analysis identified that FEV1 reduction due to carbon black exposure could be fully explained by wall thickening of the sixth generation of airways, supporting the importance of airway morphology in dictating lung function change (Diaz et al., 2015; Washko et al., 2014).

Accumulating studies have supported WA% of segmental or subsegmental airways as a CT imaging biomarker associated with former occupational dust exposure or current cigarette smoking in senior people. Increased WA% has been shown to be associated with self-reported “ever exposure to vapors, gas, dust, or fumes” in the SPIROMICS cohort which enrolled smokers with >20 packyears (Paulin et al., 2018). Similar result was also observed in male smokers of COPDGene cohort with airway wall thickening expressed as mean square root wall area of 10-mm internal perimeter airways (Marchetti et al., 2014). A dose-response was also established between previous organic dust exposure and increased WA% in a cohort of former cotton textile workers (Lai et al., 2016). WA% was also identified to be elevated in smokers versus never smokers (Donohue et al., 2012; Washko et al., 2014). Interestingly, 2 of these studies introduced above tried to suggest lumen narrowing as a likely primary driver for the elevated WA% observed, though the total airway area was not analyzed in either studies (Donohue et al., 2012; Paulin et al., 2018). Despite that, based on the pattern of changes in crude area measurements (ie, wall, lumen, and total airway areas) caused by carbon black exposure, our study suggested airway wall thickening as the major driver for the observed elevation of WA% in CBPs. Radiological reports based on end-inspiration CT did not identify evidence of increased prevalence of emphysema or lung fibrosis in current CBPs and no workers have met spirometry diagnosis of airway obstruction (ie, FEV1/FVC < 0.70) yet. This suggested that in this relatively young group of study subjects, small airway wall thickening could be an early pathological event contributing to lung injury caused by chronic exposure to nanoscale carbon black aerosol and emerges prior to the occurrence of large airway diseases or emphysematous changes. Moreover, a longitudinal study based on repeated measurements of airway dimensions in newly employed workers is needed to characterize temporal dynamics of airway wall thickening after initiation of exposure and how this progresses into stages associated with clinical diseases and symptoms.

A key question of pathological basis for wall thickening of these airways observed under quantitative CT in CBPs remains. Our previous studies showed that exposure to 30 μg/m3 carbon black aerosol for 28 or 90 days in SD rats caused dramatic tissue remodeling including alveolar wall thickening, collagen deposition, and formation of mature fibrotic nodules (Chu et al., 2019; Han et al., 2020). Using the same animal model, we also identified small airway wall thickening as an additional feature caused by carbon black exposure and may result from hyperplastic change of bronchus epithelium. Six subjects reported having cough or phlegm for ≥3 months over the prior year and 3 of those subjects had both symptoms and were all CBPs who never smoked. This suggests that goblet cell metaplasia may start to progress in these subjects due to carbon black exposure (Leng et al., 2015). Postmortem studies of lung tissues from Mexico City and Vancouver residents had identified that chronic exposure to high levels of particulate air pollution resulted in presence of carbonaceous aggregates of ultrafine particles in the airway mucosa and abnormal small airways with fibrotic walls and excess muscle, consistent with mixed dust pneumoconiosis (Churg et al., 2003). Nevertheless, further studies based on lung biopsies in exposed workers may delineate airway wall components contributing to small airway wall thickening observed under quantitative CT.

A comparative study involving several nanoscale particles with different primary particle size, organic content, and surface area was conducted to compare their potency in inducing acute lung inflammation 24 h after intratracheal instillation in healthy mice (Stoeger et al., 2006). A large variation in potency of inducing lung inflammation was identified across particles with surface area as the most predictive parameter for this effect. The carbon black in our study has a high surface area of 74.85 m2/g measured using the Brunauer-Emmett-Teller method. However, it is impossible to calculate the total mass and surface area of carbon black deposited in each individual’s lung. Instead, we used CCAM to assess the lung dose of carbon black in each worker and identified a linear dose-response with WA%, supporting CCAM as a good bio-effective biomarker that could bridge carbon black inhalation exposure and lung effects.

Our study included current smokers. Cigarette smoke particles are generally described as being “pigmented,” ie, brownish, golden or yellowish, which was “presumed” to interfere with the identification of black particles in airway macrophage (Bai et al., 2015). Because of this concern, subjects with direct or indirect exposure to cigarette smoke were excluded in most studies involving CCAM for exposure assessments. However, no difference of CCAM was identified between ever smokers and never smokers in either CBPs or non-CBPs. Several reasons may explain this. First, high background EC in air pollution seen in reference areas and high carbon black exposure in bagging areas may disguise any presumed effect of cigarette smoking. Indeed, the weight percentage of EC in the TC in cigarette smoke particles was <1.8% with the rest being OC (reviewed in Saxena et al., 2011). Second, sputum collected in the field was stored in Saccomano’s fixative for several months and was washed once with fresh Saccomano’s fixative prior to mucolytic treatment. Thus, the pigmented component from cigarette smoke may be extracted by alcohol in Saccomano’s fixative and discarded during processing. However, our results may not be generalizable to studies conducted in areas with minimal background air pollution or using method not involving Saccomano’s fixative. Although smoking status was not matched between CBPs and non-CBPs, our results could not be confounded because cigarette smoking was not associated with either CCAM or any airway area measurements. However, we did find a suggestive effect modification of cigarette smoking on the associations between carbon black exposure status (p = .07) or CCAM (p = .0078) and WA% for the ninth generation of airways with most dramatic exposure-effect correlation identified in never smokers, suggesting certain cigarette smoke constituents may modify the inflammatory response in carbon black loaded macrophages in the lungs, a hypothesis for future testing.

In summary, our study identified imaging evidence supporting small airway wall thickening as early pathological changes in the lungs of workers, which may also help explain the effect of carbon black exposure on lung function impairment. This study provides structural evidence of small airway alterations that together with spirometry and blood biomarkers of lung injury (eg, surfactant protein A and Clara cell protein) contributes to a more thorough understanding of pulmonary toxicity due to chronic inhalation exposure to high levels of nanoscale carbon black particles in humans. With the maturation of quantitative assessment of airway morphology and better resolution, quantitative CT may become a more suitable radiological approach for health surveillance in workers exposed to PMs especially for those without clinical symptoms and disease diagnosis of lungs. Moreover, our improvement of the CCAM methodology made this method more suitable for large-scale epidemiological studies and more precise. Because carbon black has been regarded as a carbonaceous core analog for many airborne soot-containing PMs and is of nanoscale, our findings may also contribute to the understanding of the pulmonary toxicity caused by many airborne soot-containing PMs and engineered carbon-based nanomaterials through comparative studies (Long et al., 2013; Stoeger et al., 2006; Swafford et al., 1995).

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary data are available at Toxicological Sciences online.

Author Contributions

Y.Z., W.H., and S.L. conceived of and designed the study; X.C., L.L., Q.M., X.Z., Y.L., H.L., Y.L., T.W., J.T., M.J., R.Z., S.Y., and Z.Y. performed the data collection and management; Y.L. led the sputum induction and CCAM analysis; Q.M. (radiologist) and W.H. (pulmonologist) supervised CT measurements; X.C., T.W., and S.L. conducted the data analyses and tabulated the results; A.S. and S.L. interpreted the results and drafted the manuscript; and A.S., Y.Z., W.H., and S.L. critically edited the manuscript. All authors have read the manuscript and approved its submission.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank staff from Luoyang and Jiaozuo Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for their assistance in organizing field study, radiologists Dr Guifeng Qiao from Luoyang Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine and Dr Jianjun Wang from Jiaozuo Tongren Hospital for their assistance in chest CT scanning, and pulmonary function technician Ms Shuzhen Yin from Wuyang Iron and Steel Company for conducting spirometry test. The field survey and CT measurements were completed during Dr S.L.’s affiliation with Qingdao University prior to 2020. Finalizing data analysis and critical revision and submission of the manuscript was conducted during Dr S.L.’s employment at University of New Mexico since 2020.

FUNDING

This study was primarily supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (91643203 and 81872600) and by Guangdong Provincial Natural Science Foundation Team Project (2018B030312005). Dr W.H. received support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81973012). Dr Z.Y. received support from Local Innovative and Research Teams Project of Guangdong Pearl River Talents Program (2017BT01Z134). Finalizing data analysis, critical revision, and submission of the article received Cancer Center Support Grant National Cancer Institute (P30CA118100).

DECLARATION OF CONFLICTING INTERESTS

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Contributor Information

Xue Cao, Department of Occupational and Environmental Health, School of Public Health.

Li Lin, Department of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, Qingdao Municipal Hospital, School of Medicine, Qingdao University, Qingdao 266021, China.

Akshay Sood, Department of Internal Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque, New Mexico 87131.

Qianli Ma, Department of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, Qingdao Municipal Hospital, School of Medicine, Qingdao University, Qingdao 266021, China.

Xiangyun Zhang, State Key Laboratory of Organic Geochemistry, Guangdong Key Laboratory of Environment and Resources, Guangzhou Institute of Geochemistry, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Guangzhou 510640, China.

Yuansheng Liu, Department of Occupational and Environmental Health, School of Public Health.

Hong Liu, Department of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, Qingdao Municipal Hospital, School of Medicine, Qingdao University, Qingdao 266021, China.

Yanting Li, Department of Occupational and Environmental Health, School of Public Health.

Tao Wang, Department of Occupational and Environmental Health, School of Public Health.

Jinglong Tang, Department of Occupational and Environmental Health, School of Public Health.

Menghui Jiang, Department of Occupational and Environmental Health, School of Public Health.

Rong Zhang, Department of Toxicology, School of Public Health, Hebei Medical University, Shijiazhuang 050017, China.

Shanfa Yu, Henan Institute of Occupational Medicine, Zhengzhou, Henan 450052, China.

Zhiqiang Yu, State Key Laboratory of Organic Geochemistry, Guangdong Key Laboratory of Environment and Resources, Guangzhou Institute of Geochemistry, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Guangzhou 510640, China.

Yuxin Zheng, Department of Occupational and Environmental Health, School of Public Health.

Wei Han, Department of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, Qingdao Municipal Hospital, School of Medicine, Qingdao University, Qingdao 266021, China.

Shuguang Leng, Department of Occupational and Environmental Health, School of Public Health; Department of Internal Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque, New Mexico 87131; Cancer Control and Population Sciences, University of New Mexico Comprehensive Cancer Center, Albuquerque, New Mexico 87131.

The authors certify that all research involving human subjects was done under full compliance with all government policies and the Helsinki Declaration.

REFERENCES

- Bai Y., Bove H., Nawrot T. S., Nemery B. (2018. a). Carbon load in airway macrophages as a biomarker of exposure to particulate air pollution; a longitudinal study of an international panel. Part Fibre Toxicol. 15, 14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai Y., Brugha R. E., Jacobs L., Grigg J., Nawrot T. S., Nemery B. (2015). Carbon loading in airway macrophages as a biomarker for individual exposure to particulate matter air pollution - A critical review. Environ. Int. 74, 32–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai Y., Casas L., Scheers H., Janssen B. G., Nemery B., Nawrot T. S. (2018. b). Mitochondrial DNA content in blood and carbon load in airway macrophages. A panel study in elderly subjects. Environ. Int. 119, 47–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belli A. J., Bose S., Aggarwal N., DaSilva C., Thapa S., Grammer L., Paulin L. M., Hansel N. N. (2016). Indoor particulate matter exposure is associated with increased black carbon content in airway macrophages of former smokers with COPD. Environ. Res. 150, 398–402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergeron C., Tulic M. K., Hamid Q. (2007). Tools used to measure airway remodelling in research. Eur. Respir. J. 29, 596–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng W., Liu Y., Tang J., Duan H., Wei X., Zhang X., Yu S., Campen M. J., Han W., Rothman N., et al. (2020). Carbon content in airway macrophages and genomic instability in Chinese carbon black packers. Arch. Toxicol. 94, 761–771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu C., Zhou L., Xie H., Pei Z., Zhang M., Wu M., Zhang S., Wang L., Zhao C., Shi L., et al. (2019). Pulmonary toxicities from a 90-day chronic inhalation study with carbon black nanoparticles in rats related to the systemical immune effects. Int. J. Nanomedicine 14, 2995–3013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Churg A., Brauer M., del Carmen Avila-Casado M., Fortoul T. I., Wright J. L. (2003). Chronic exposure to high levels of particulate air pollution and small airway remodeling. Environ. Health Perspect. 111, 714–718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai Y., Niu Y., Duan H., Bassig B. A., Ye M., Zhang X., Meng T., Bin P., Jia X., Shen M., et al. (2016). Effects of occupational exposure to carbon black on peripheral white blood cell counts and lymphocyte subsets. Environ. Mol. Mutagen. 57, 615–622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz A. A., Rahaghi F. N., Ross J. C., Harmouche R., Tschirren J., San Jose Estepar R., Washko G. R., investigators C. G; for the COPD Gene investigators (2015). Understanding the contribution of native tracheobronchial structure to lung function: CT assessment of airway morphology in never smokers. Respir. Res. 16, 23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donohue K. M., Hoffman E. A., Baumhauer H., Guo J., Budoff M., Austin J. H., Kalhan R., Kawut S., Tracy R., Barr R. G. (2012). Cigarette smoking and airway wall thickness on ct scan in a multi-ethnic cohort: The mesa lung study. Respir. Med. 106, 1655–1664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dournes G., Laurent F. (2012). Airway remodelling in asthma and COPD: Findings, similarities, and differences using quantitative CT. Pulm. Med. 2012, 670414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fehrenbach H., Wagner C., Wegmann M. (2017). Airway remodeling in asthma: What really matters. Cell Tissue Res. 367, 551–569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frankenberger M., Menzel M., Betz R., Kassner G., Weber N., Kohlhaufl M., Haussinger K., Ziegler-Heitbrock L. (2004). Characterization of a population of small macrophages in induced sputum of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and healthy volunteers. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 138, 507–516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardiner K., Trethowan N. W., Harrington J. M., Rossiter C. E., Calvert I. A. (1993). Respiratory health effects of carbon black: A survey of European carbon black workers. Br. J. Ind. Med. 50, 1082–1096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardiner K., van Tongeren M., Harrington M. (2001). Respiratory health effects from exposure to carbon black: Results of the phase 2 and 3 cross sectional studies in the European carbon black manufacturing industry. Occup. Environ. Med. 58, 496–503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray C. A., Muranko H. (2006). Studies of robustness of industrial aciniform aggregates and agglomerates–carbon black and amorphous silicas: A review amplified by new data. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 48, 1279–1290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo C., Zhang Z., Lau A. K. H., Lin C. Q., Chuang Y. C., Chan J., Jiang W. K., Tam T., Yeoh E. K., Chan T. C., et al. (2018). Effect of long-term exposure to fine particulate matter on lung function decline and risk of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in Taiwan: A longitudinal, cohort study. Lancet Planet Health 2, e114–e125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han B., Chu C., Su X., Zhang N., Zhou L., Zhang M., Yang S., Shi L., Zhao B., Niu Y., et al. (2020). N(6)-methyladenosine-dependent primary microRNA-126 processing activated PI3K-AKT-mtor pathway drove the development of pulmonary fibrosis induced by nanoscale carbon black particles in rats. Nanotoxicology 14, 1–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harber P., Muranko H., Solis S., Torossian A., Merz B. (2003). Effect of carbon black exposure on respiratory function and symptoms. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 45, 144–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- International Carbon Black Association. (2016). Carbon Black User’s Guide. Available at: http://www.carbon-black.org/images/docs/2016-ICBA-Carbon-Black-User-Guide.pdf. Accessed August 23, 2019.

- Jacobs L., Emmerechts J., Hoylaerts M. F., Mathieu C., Hoet P. H., Nemery B., Nawrot T. S. (2011). Traffic air pollution and oxidized LDL. PLoS One 6, e16200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs L., Emmerechts J., Mathieu C., Hoylaerts M. F., Fierens F., Hoet P. H., Nemery B., Nawrot T. S. (2010). Air pollution related prothrombotic changes in persons with diabetes. Environ. Health Perspect. 118, 191–196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalappanavar N. K., Vinodkumar C. S., Gouli C., Sanjay D., Nagendra K., Basavarajappa K. G., Patil R. (2012). Carbon particles in airway macrophage as a surrogate marker in the early detection of lung diseases. Int. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 3, 68–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirby M., Tanabe N., Tan W. C., Zhou G., Obeidat M., Hague C. J., Leipsic J., Bourbeau J., Sin D. D., Hogg J. C., et al. (2018). Total airway count on computed tomography and the risk of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease progression. Findings from a population-based study. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 197, 56–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulkarni N., Pierse N., Rushton L., Grigg J. (2006). Carbon in airway macrophages and lung function in children. N. Engl. J. Med. 355, 21–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai P. S., Hang J. Q., Zhang F. Y., Sun J., Zheng B. Y., Su L., Washko G. R., Christiani D. C. (2016). Imaging phenotype of occupational endotoxin-related lung function decline. Environ. Health Perspect. 124, 1436–1442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leng S., Liu Y., Weissfeld J. L., Thomas C. L., Han Y., Picchi M. A., Edlund C. K., Willink R. P., Davis A. L., Do K. C., et al. (2015). 15q12 variants, sputum gene promoter hypermethylation, and lung cancer risk: A GWAS in smokers. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 107, 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long C. M., Nascarella M. A., Valberg P. A. (2013). Carbon black vs. black carbon and other airborne materials containing elemental carbon: Physical and chemical distinctions. Enviro. Pollut. 181, 271–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lotz G., Plitzko S., Gierke E., Tittelbach U., Kersten N., Schneider W. D. (2008). Dose-response relationships between occupational exposure to potash, diesel exhaust and nitrogen oxides and lung function: Cross-sectional and longitudinal study in two salt mines. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 81, 1003–1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchetti N., Garshick E., Kinney G. L., McKenzie A., Stinson D., Lutz S. M., Lynch D. A., Criner G. J., Silverman E. K., Crapo J. D. (2014). Association between occupational exposure and lung function, respiratory symptoms, and high-resolution computed tomography imaging in COPDGene. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 190, 756–762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller M. R., Hankinson J., Brusasco V., Burgos F., Casaburi R., Coates A., Crapo R., Enright P., van der Grinten C. P., Gustafsson P., et al. (2005). Standardisation of spirometry. Eur. Respir. J. 26, 319–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morfeld P., Noll B., Buchte S. F., Derwall R., Schenk V., Bicker H. J., Lenaerts H., Schrader N., Dahmann D. (2010). Effect of dust exposure and nitrogen oxides on lung function parameters of german coalminers: A longitudinal study applying gee regression 1974-1998. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 83, 357–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nwokoro C., Ewin C., Harrison C., Ibrahim M., Dundas I., Dickson I., Mushtaq N., Grigg J. (2012). Cycling to work in London and inhaled dose of black carbon. Eur. Respir. J. 40, 1091–1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulin L. M., Smith B. M., Koch A., Han M., Hoffman E. A., Martinez C., Ejike C., Blanc P. D., Rous J., Barr R. G., et al. (2018). Occupational exposures and computed tomographic imaging characteristics in the Spiromics cohort. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 15, 1411–1419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelucchi C., Negri E., Gallus S., Boffetta P., Tramacere I., La Vecchia C. (2009). Long-term particulate matter exposure and mortality: A review of European epidemiological studies. BMC Public Health 9, 453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng R. D., Chang H. H., Bell M. L., McDermott A., Zeger S. L., Samet J. M., Dominici F. (2008). Coarse particulate matter air pollution and hospital admissions for cardiovascular and respiratory diseases among medicare patients. JAMA 299, 2172–2179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen H., Vazquez Guillamet R., Meek P., Sood A., Tesfaigzi Y. (2018). Early endotyping: A chance for intervention in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 59, 13–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saxena R. K., McClure M. E., Hays M. D., Green F. H., McPhee L. J., Vallyathan V., Gilmour M. I. (2011). Quantitative assessment of elemental carbon in the lungs of never smokers, cigarette smokers, and coal miners. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health A 74, 706–715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoeger T., Reinhard C., Takenaka S., Schroeppel A., Karg E., Ritter B., Heyder J., Schulz H. (2006). Instillation of six different ultrafine carbon particles indicates a surface area threshold dose for acute lung inflammation in mice. Environ. Health Perspect. 114, 328–333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swafford D. S., Nikula K. J., Mitchell C. E., Belinsky S. A. (1995). Low frequency of alterations in p53, K-ras, and mdm2 in rat lung neoplasms induced by diesel exhaust or carbon black. Carcinogenesis 16, 1215–1221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang J C. W., Gao J., Li Y., Yao R., Rothman N., Lan Q., Campen M., Zheng Y., Leng S. (2020). Occupational exposure to carbon black nanoparticles increases inflammatory vascular disease risk: An implication of an ex vivo biosensor assay. Particle Fibre Toxicol. (pending acceptance). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Tongeren M. J., Gardiner K., Rossiter C. E., Beach J., Harber P., Harrington M. J. (2002). Longitudinal analyses of chest radiographs from the European carbon black respiratory morbidity study. Eur. Respir. J. 20, 417–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang T., Wang H., Chen J., Wang J., Ren D., Hu W., Wang H., Han W., Leng S., Zhang R., et al. (2020). Association between air pollution and lung development in schoolchildren in China. J. Epidemiol. Community Health. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Washko G. R., Diaz A. A., Kim V., Barr R. G., Dransfield M. T., Schroeder J., Reilly J. J., Ramsdell J. W., McKenzie A., Van Beek E. J., et al. (2014). Computed tomographic measures of airway morphology in smokers and never-smoking normals. J. Appl. Physiol. (1985) 116, 668–673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitehouse A. L., Miyashita L., Liu N. M., Lesosky M., Flitz G., Ndamala C., Balmes J. R., Gordon S. B., Mortimer K., Grigg J. (2018). Use of cleaner-burning biomass stoves and airway macrophage black carbon in Malawian women. Sci. Total Environ. 635, 405–411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang M., Li Y., Meng T., Zhang L., Niu Y., Dai Y., Gao W., Bloom M. S., Dong G., Zheng Y. (2019). Ultrafine CB-induced small airway obstruction in CB-exposed workers and mice. Sci. Total Environ. 671, 866–873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanobetti A., Schwartz J. (2009). The effect of fine and coarse particulate air pollution on mortality: A national analysis. Environ. Health Perspect. 117, 898–903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang R., Dai Y., Zhang X., Niu Y., Meng T., Li Y., Duan H., Bin P., Ye M., Jia X., et al. (2014). Reduced pulmonary function and increased pro-inflammatory cytokines in nanoscale carbon black-exposed workers. Part Fibre Toxicol. 11, 73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.